1. Introduction

Cholesteatoma is a chronic, keratinizing squamous epithelial lesion of the middle ear and mastoid that behaves in a locally aggressive manner, causing progressive bone erosion and potentially life-threatening complications if untreated[

1]Although rare, its destructive potential makes early diagnosis and effective surgical management imperative. Clinically, cholesteatoma may be classified into congenital, primary acquired, secondary acquired, and recurrent forms[

2]

To ensure consistency in describing cholesteatoma, the European Academy of Otology and Neuro-Otology (EAONO) and the Japanese Otological Society (JOS) have introduced two classification systems[

3]The STAMCO system, published in 2015, provides a detailed description of disease extension but is often considered cumbersome in multicenter use. In contrast, the ChOLE system, proposed in 2017, offers a more straightforward and more reproducible framework, focusing on cholesteatoma extension, ossicular status, complications, and Eustachian tube focusing on mastoid condition[

4] Because of its reliability and stronger correlation with clinical outcomes, ChOLE is now widely recommended for research and clinical reporting[

5].

1.1. Endoscopic Ear Surgery in Cholesteatoma Management

In recent decades, endoscopic ear surgery (EES) has become an increasingly accepted alternative or adjunct to conventional microscopic techniques[

6]Initially pioneered by Marchioni and colleagues, the transcanal endoscopic approach provides wide-angle and magnified visualization, enabling access to hidden recesses such as the sinus tympani, anterior epitympanum, and facial recess, where residual disease commonly persists[

7]. Several comparative studies and meta-analyses have shown that EES achieves similar or lower recurrence and residual rates compared with microscopic surgery, with additional advantages including reduced surgical morbidity, shorter hospitalization, and improved cosmetic outcomes [

8].

1.2. Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

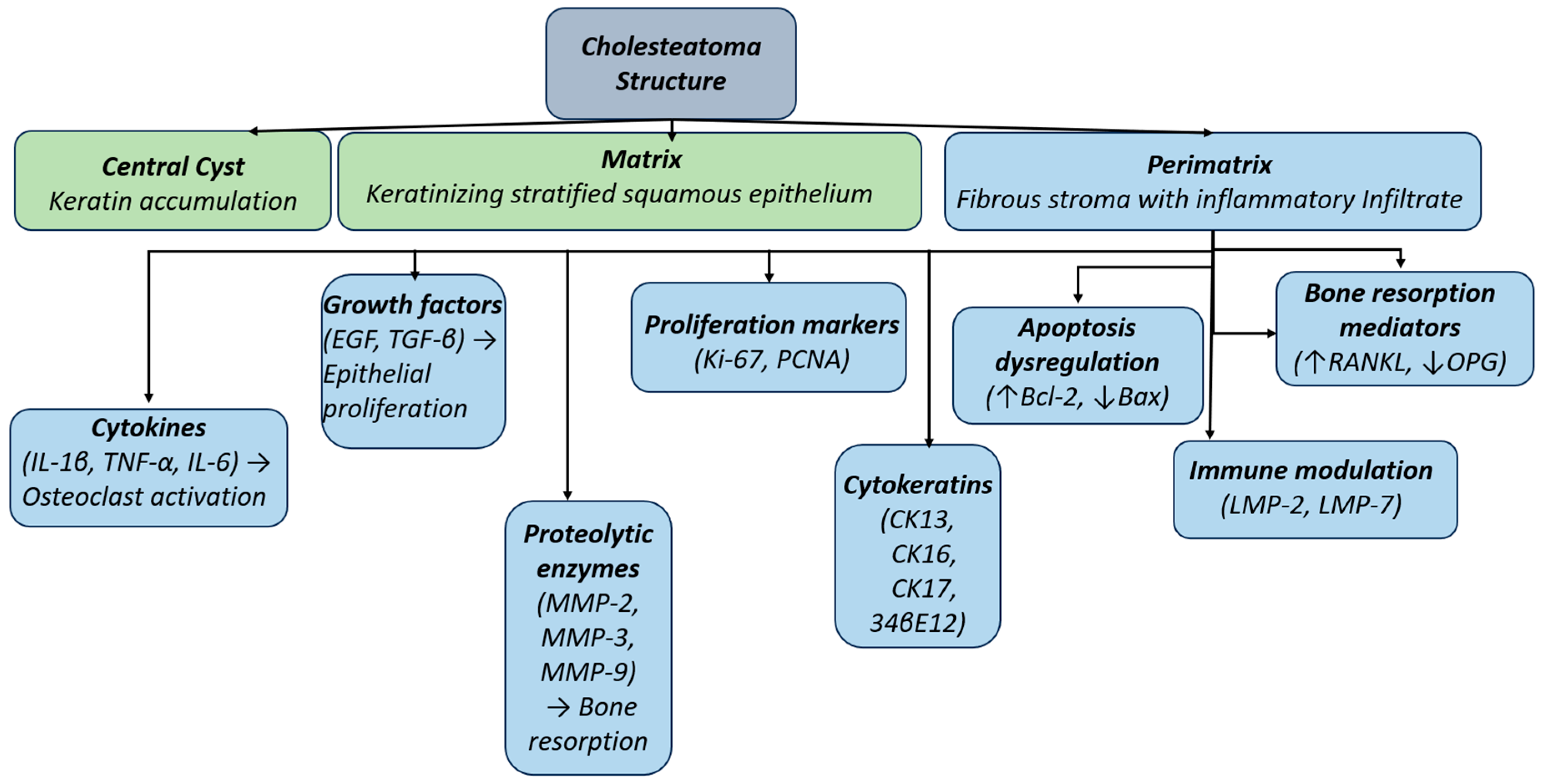

Histologically, cholesteatoma comprises three essential components: the matrix (keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium), keratin debris, and the perimatrix, a fibrovascular stroma with chronic inflammatory infiltrate [

9,

10]. The perimatrix is metabolically active and releases pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6) and growth factors (EGF, TGF-β), which promote epithelial proliferation and osteoclastic activation. Immunohistochemistry demonstrates overexpression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9), correlating with bone resorption [

11]Proliferation markers such as Ki-67 and PCNA are upregulated, while cytokeratin profiles (CK13, CK16, CK17, 34βE12) suggest a hyperproliferative phenotype distinct from normal auditory canal epithelium[

12]. Apoptosis regulators (↑Bcl-2, ↓Bax), immune proteasome subunits (LMP-2, LMP-7), and a RANKL/OPG imbalance further contribute to tissue persistence and osteolysis[

13]. Collectively, these findings confirm that cholesteatoma is not merely a passive accumulation of keratin but an active inflammatory and hyperproliferative lesion with tumor-like biological behavior[

14]

Figure 1.

Histopathological and molecular structure of cholesteatoma. The lesion consists of three main components: matrix (keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium), keratin debris (lamellar accumulation), and perimatrix (fibrous stroma with inflammatory infiltrate).

Figure 1.

Histopathological and molecular structure of cholesteatoma. The lesion consists of three main components: matrix (keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium), keratin debris (lamellar accumulation), and perimatrix (fibrous stroma with inflammatory infiltrate).

The perimatrix is the metabolically most active region, releasing multiple mediators: Cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6) stimulate osteoclast activation and bone resorption

Growth factors (EGF, TGF-β) promote epithelial proliferation.

Proteolytic enzymes (MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9) enhance local bone destruction.

Proliferation markers (Ki-67, PCNA) indicate the hyperproliferative nature of the epithelium.

Cytokeratins (CK13, CK16, CK17, 34βE12) highlight altered epithelial differentiation.

Apoptosis regulators (↑Bcl-2, ↓Bax) demonstrate dysregulation of programmed cell death.

Immune modulation molecules (LMP-2, LMP-7) contribute to chronic inflammation.

Bone resorption mediators (↑RANKL, ↓OPG) further accelerate osteoclastic activity[

15].

1.3. Aim of the Present Study

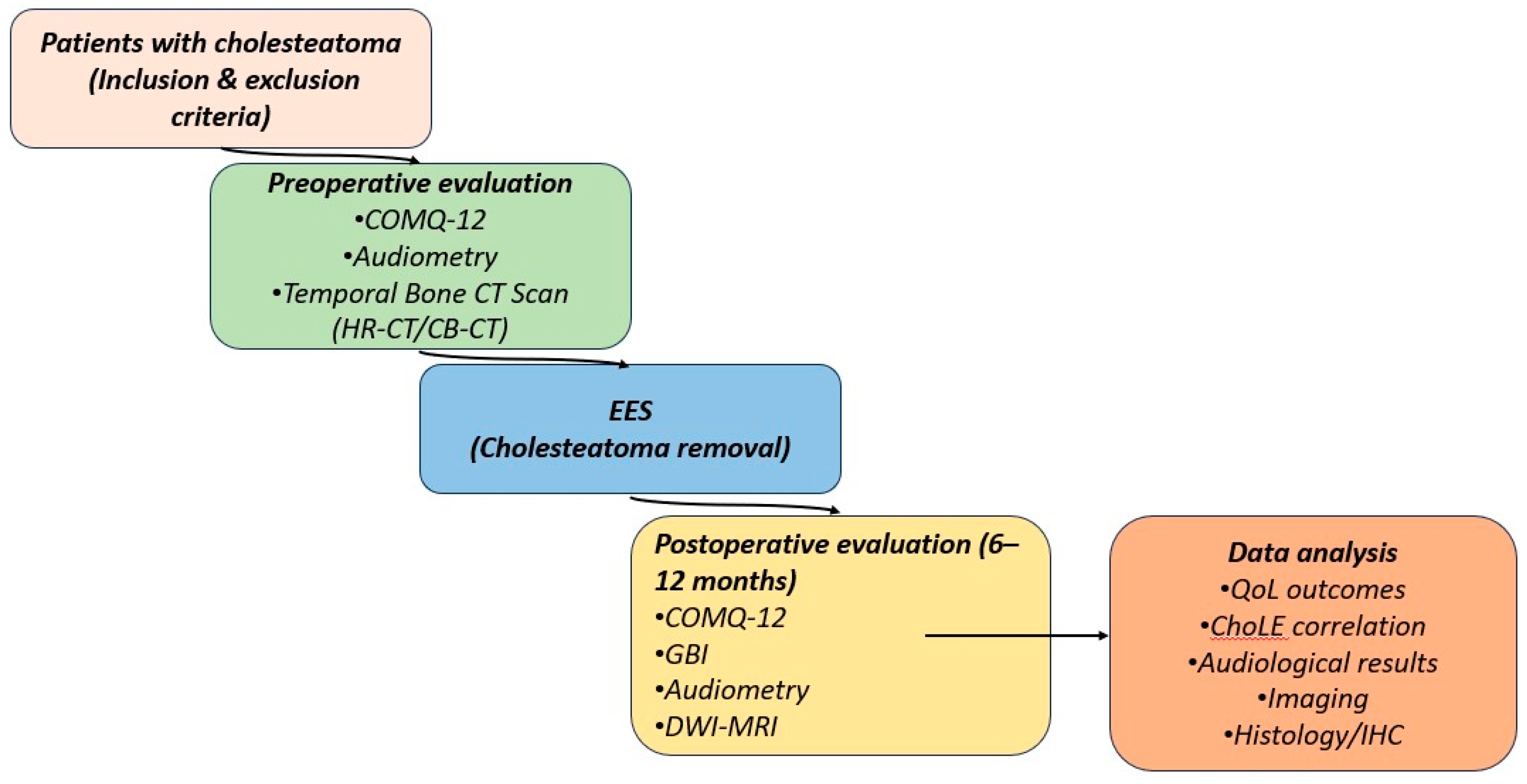

This study was designed as a prospective, analytical, monocentric investigation conducted at the “Prof. Dr. Dorin Hociota” Institute of Phonoaudiology and ENT Functional Surgery in Bucharest, Romania. Over a 20-month period, between October 2023 and May 2025, 41 patients with middle ear cholesteatoma underwent surgery using an exclusively endoscopic approach. Pre- and postoperative QoL assessments were performed using the COMQ-12 and GBI questionnaires, associated audiological, and imaging evaluations. The objective was to analyze postoperative QoL improvement, PROMs dynamic, and audiological outcomes, thereby providing an integrated, patient-centered perspective on the benefits of endoscopic cholesteatoma surgery.

Figure 2.

Study workflow for patients with cholesteatoma. Patients with cholesteatoma were prospectively enrolled according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Preoperative assessment included PROMs (COMQ-12), audiometry, and imaging (Temporal Bone CT Scan). Postoperative follow-up at 6–12 months consisted of repeat COMQ-12 and GBI questionnaires, audiometry, and DWI-MRI when indicated. Data analysis integrated QoL outcomes, audiological results, imaging findings, and exploratory histological/immunohistochemical evaluation.

Figure 2.

Study workflow for patients with cholesteatoma. Patients with cholesteatoma were prospectively enrolled according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Preoperative assessment included PROMs (COMQ-12), audiometry, and imaging (Temporal Bone CT Scan). Postoperative follow-up at 6–12 months consisted of repeat COMQ-12 and GBI questionnaires, audiometry, and DWI-MRI when indicated. Data analysis integrated QoL outcomes, audiological results, imaging findings, and exploratory histological/immunohistochemical evaluation.

Table 1.

Study objectives: to evaluate quality of life outcomes after endoscopic cholesteatoma surgery.

Table 1.

Study objectives: to evaluate quality of life outcomes after endoscopic cholesteatoma surgery.

Primary

objective

|

To assess the impact of endoscopic cholesteatoma surgery on health-related quality of life (QoL) using two validated PROMs: COMQ-12 and GBI. |

Secondary

objectives

|

To compare pre- and postoperative COMQ-12 scores and quantify improvement in specific domains (symptoms, psychosocial impact, health service use). To evaluate postoperative GBI scores (general, social, and physical benefit). To analyze correlations between PROMs and clinical variables: audiological outcomes (PTA gain) and disease classification (STAMCO) |

Exploratory

objective

|

To contextualize PROMs findings with histological and immunohistochemical features of cholesteatoma (MMPs, cytokines, Ki-67, cytokeratins), highlighting potential links between biological aggressiveness and patient-perceived burden. |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This investigation was designed as a prospective observational study conducted at a single tertiary referral center. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of “Prof. Dr. Hociota” Institute of Phonoaudiology and ENT Functional Surgery (approval code: 8696) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants provided written informed consent before enrollment. To minimize bias, strict inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, excluding patients with extensive disease that would have required a microscopic or combined approach. All eligible patients scheduled for exclusive endoscopic surgery during the study period (October 2023–May 2025) were approached for enrollment. Consecutive enrollment of eligible cases further reduced the risk of selection bias. Importantly, no patients were lost to follow-up, as all 41 participants completed the planned 12-month evaluation, thereby eliminating attrition bias. Patients with a diagnosis of primary or recurrent cholesteatoma (suggested clinically and radiologically) who were scheduled for exclusive EES were consecutively recruited over the study period. The design and reporting of the study adhere to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines[

16] The analysis encompassed both clinical outcomes and patient-reported outcomes, with pre- and postoperative quality-of-life assessments (using the COMQ-12 and GBI, detailed below)[

17,

18]

2.2. Patient Selection and Eligibility Criteria

To ensure a homogeneous study population and minimize confounding factors, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were established based on prior reports of endoscopic cholesteatoma surgery and PROM-based outcome studies, tailored to the objectives of this investigation. In brief, we included adult patients with clinically and radiologically confirmed primary or recurrent cholesteatoma that was amenable to an exclusively endoscopic (transcanal) surgical approach. Eligibility further required the ability to complete the QoL questionnaires (COMQ-12 and GBI) preoperatively and postoperatively, and a planned follow-up of at least 12 months[

19,

20].

Exclusion criteria were defined to eliminate factors that could bias the evaluation of surgical outcomes. Patients were not eligible if the lesions extended beyond the posterior limit of the lateral semicircular canal[

21]. Patients with any medical contraindication to general anesthesia were also excluded. Additionally, individuals with cognitive impairment or other conditions precluding reliable questionnaire completion were not enrolled. . By applying these strict criteria, we obtained a representative cohort of cholesteatoma patients amenable to endoscopic surgery, allowing meaningful interpretation of postoperative patient-reported outcome changes. These criteria are summarized in

Table 2.

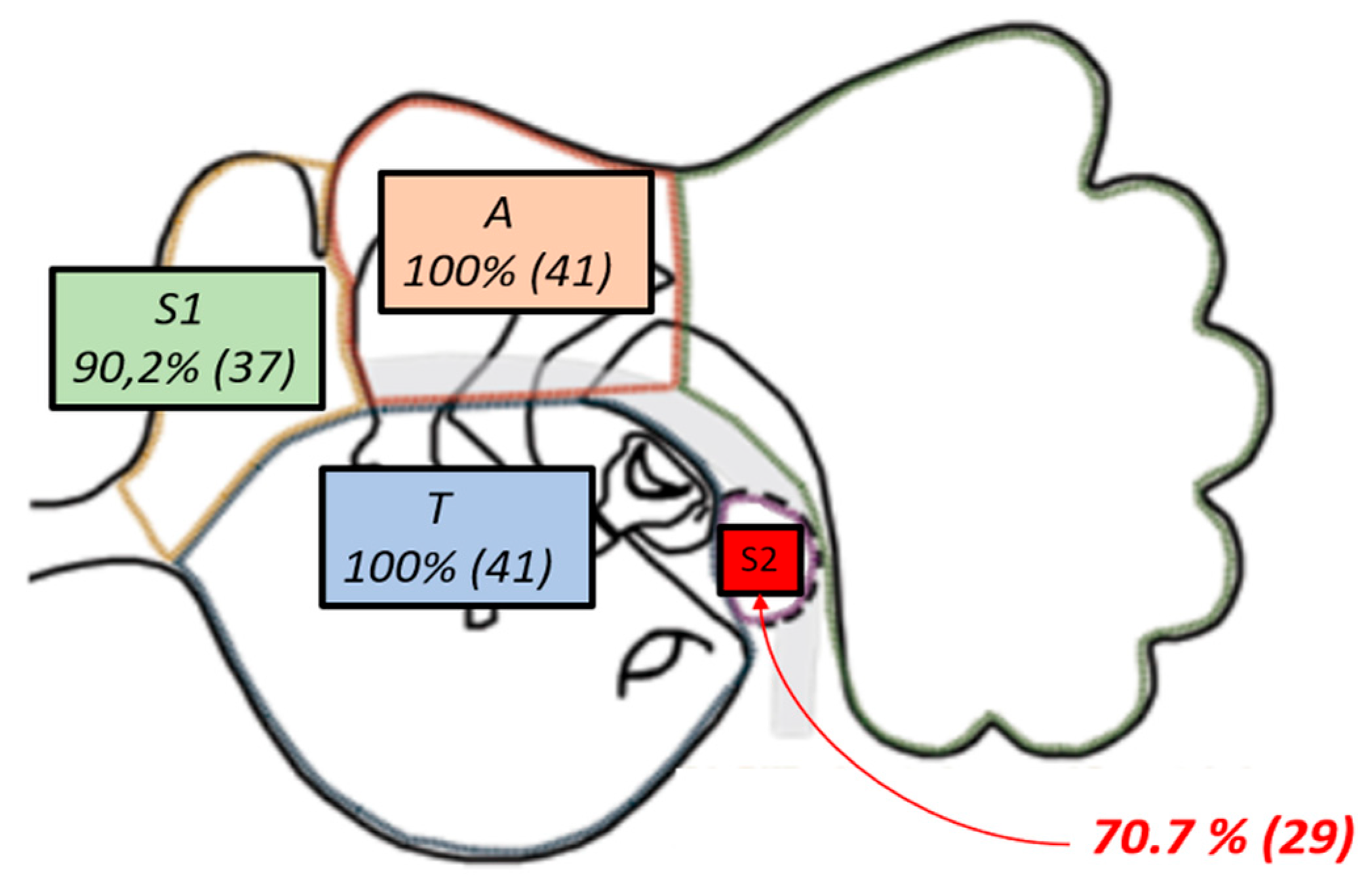

Cholesteatoma extension in each patient was documented according to the STAMCO and Chole classification system for cholesteatoma[

22]. Based on Chole classification, our cohort is included in Stage 1, and all patients, based on STAMCO classification (100%, n = 41), had cholesteatoma involving the attic (A) and the tympanic cavity (T)[

23] Additionally, 90.2% of cases showed extension into the anterior epitympanic recess (S1, also known as the supratubal recess or “anterior difficult area”), and 70.7% had disease involving the posterior tympanic recess (S2, the sinus tympani or “posterior difficult area”), none of the included cholesteatomas extended beyond the posterior limit of the lateral semicircular canal[

24] The distribution of cholesteatoma involvement in the study cohort is illustrated in

Figure 3.

2.3. Sample Size Justification

The study size was not based on a formal sample size calculation but was determined by the pool of eligible patients evaluated during the 20-month study period (October 2023–May 2025). At the preoperative consultation, all patients with suspected cholesteatoma underwent high-resolution temporal bone CT to assess disease extension and determine eligibility for an exclusively endoscopic approach. Based on these criteria, 41 patients were deemed eligible and subsequently included in the study. None of these patients required intraoperative conversion from an endoscopic to a combined or microscopic approach. During the same 20-month interval, 451 canal wall-up (CWU) and canal wall-down (CWD) mastoidectomies were performed using a microscopic approach in our department for cholesteatoma surgery, underlining that exclusively endoscopic cases represented a carefully selected subset rather than an arbitrary sample size.

2.4. Surgical Technique

All procedures were performed under general anesthesia via an exclusive endoscopic transcanal approach. A rigid Hopkins rod-lens endoscope (0° or 30°, 3 mm diameter, 14 cm length), integrated with a Full-HD Olympus camera system, was used for intraoperative visualization[

25]. Angled endoscopes were employed as needed to visualize and ablate cholesteatoma from hidden recesses, including the sinus tympani, anterior epitympanic (supratubal) recess, and facial recess[

26,

27]After complete disease removal, tympanic membrane reconstruction was performed using tragal cartilage graft, and if ossicular chain reconstruction was required, a partial or total ossicular replacement titanium prosthesis (PORP or TORP) was placed to restore continuity of the ossicular chain[

28].

2.4. Clinical and Audiological Assessment

Preoperative and postoperative hearing was evaluated with standard pure-tone audiometry. Air-conduction and bone-conduction thresholds were measured at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz, and the four-frequency pure-tone average (PTA) was calculated for each ear. Postoperative audiometric testing was performed at approximately 3, 6, and 12 months[

29]

2.5. Imaging Assessment

All patients underwent high-resolution computed tomography (CT) of the temporal bone preoperatively to delineate the extent of disease and identify any pertinent anatomical variations, focusing on the Fallopian canal and stapes-associated lesions[[

30]For postoperative surveillance, a non–echo-planar diffusion-weighted MRI (non-EPI DWI MRI) was obtained at 12 months after surgery to detect any residual or recurrent cholesteatoma[

31]

2.6. Quality of Life Assessment

Quality of life was assessed using two validated patient-reported outcome measures. The COMQ-1

, a 12-item disease-specific instrument, was completed preoperatively and again at 6 and 12 months postoperatively[

32] This questionnaire yields a total score from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating a greater symptom burden and impact on daily life. The GBI was administered at 6 months and 12 months after surgery to evaluate the patient’s perceived benefit from the intervention[

33]. The GBI is a generalized postoperative questionnaire that produces an overall score ranging from – 100 (maximum negative impact) to +100 (maximum positive benefit), with 0 indicating no change; it encompasses subscales for general, social, and physical health domains[

34]

2.7. Histological and Immunohistochemical Analysis (Exploratory)

Histopathological analysis was performed on all excised cholesteatoma specimens to confirm the diagnosis and characterize tissue features. In every case, routine histology (hematoxylin–eosin staining) demonstrated the hallmark components of cholesteatoma: a keratinizing squamous epithelium matrix, accumulated keratin debris, and an inflammatory perimatrix. The official pathology reports for all cases were collected and are available upon request to the corresponding author. Additionally, an exploratory immunohistochemical (IHC) evaluation was carried out on a subset of specimens for research purposes. The IHC panel included markers of cellular proliferation (Ki-67 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen [PCNA]), pro-inflammatory cytokines (interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α), proteolytic enzymes involved in bone and matrix resorption (matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9), and regulators of apoptosis (Bcl-2 and Bax)[

35,

36].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using Python (with the pandas and SciPy libraries). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) if they were approximately normally distributed, or as median with interquartile range (IQR) if they exhibited a skewed distribution. The normality of data (and of paired differences in pre/post comparisons) was evaluated with the Shapiro–Wilk test.

For paired pre- vs. post-operative comparisons within the same patients, appropriate paired statistical tests were applied. If the distribution of the paired differences met the assumption of normality, a paired Student’s t-test was used; otherwise, the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed. This approach was used to evaluate changes in COMQ-12 scores from baseline to 6 and 12 months, to compare GBI scores between 6 months and 12 months post-surgery, and to assess improvements in PTA between the preoperative and postoperative audiograms. Associations between continuous variables (for example, the correlation between improvement in COMQ-12 score and gain in PTA, or between 12-month GBI score and patient age or hearing improvement) were examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient for approximately normally distributed data, or Spearman’s rank-order correlation for non-normal data. Comparisons across more than two independent groups (e.g., comparing outcomes among different ossiculoplasty materials or techniques) were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) if the data were normal, or the Kruskal–Wallis test if normality assumptions were not met. Relationships between categorical variables (such as the presence of MRI-confirmed residual/recurrent cholesteatoma vs. the type of tympanoplasty or ossiculoplasty performed) were analyzed with the chi-square test, or with Fisher’s exact test for 2×2 tables when expected cell counts were low. All hypothesis tests were two-tailed, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All underlying data and materials (including raw audiometric values, questionnaire response datasets, and histopathology reports) are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Furthermore, generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools were utilized in this work exclusively to assist with the creation of illustrative figures; no GenAI was used for data generation, analysis, or writing of the manuscript.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 41 patients underwent exclusive endoscopic middle ear cholesteatoma surgery and were included in the analysis. The mean age at surgery was 41.0 ± 14.4 years (range 19–65). There was a predominance of female patients (25 females, 61.0%), and the right ear was affected slightly more often than the left (23 right ears, 56.1%). According to the CES classification[

37], 16 cases (39.0%) were classified as CES0, 13 (31.7%) as CES 1p, and 12 (29.3%) as CES 1a. In terms of disease staging by the ChOLE system, 21 patients (51.2%) had Stage I disease and 20 (48.8%) had Stage II. Ossicular chain reconstruction was required in most patients (70.7%): 11 received a cartilage graft, 10 a partial ossicular replacement prosthesis (PORP), and eight a total ossicular replacement prosthesis (TORP), while 12 patients (29.3%) did not require ossiculoplasty. All patients completed at least 12 months of postoperative follow-up. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort are summarized in

Table 3.

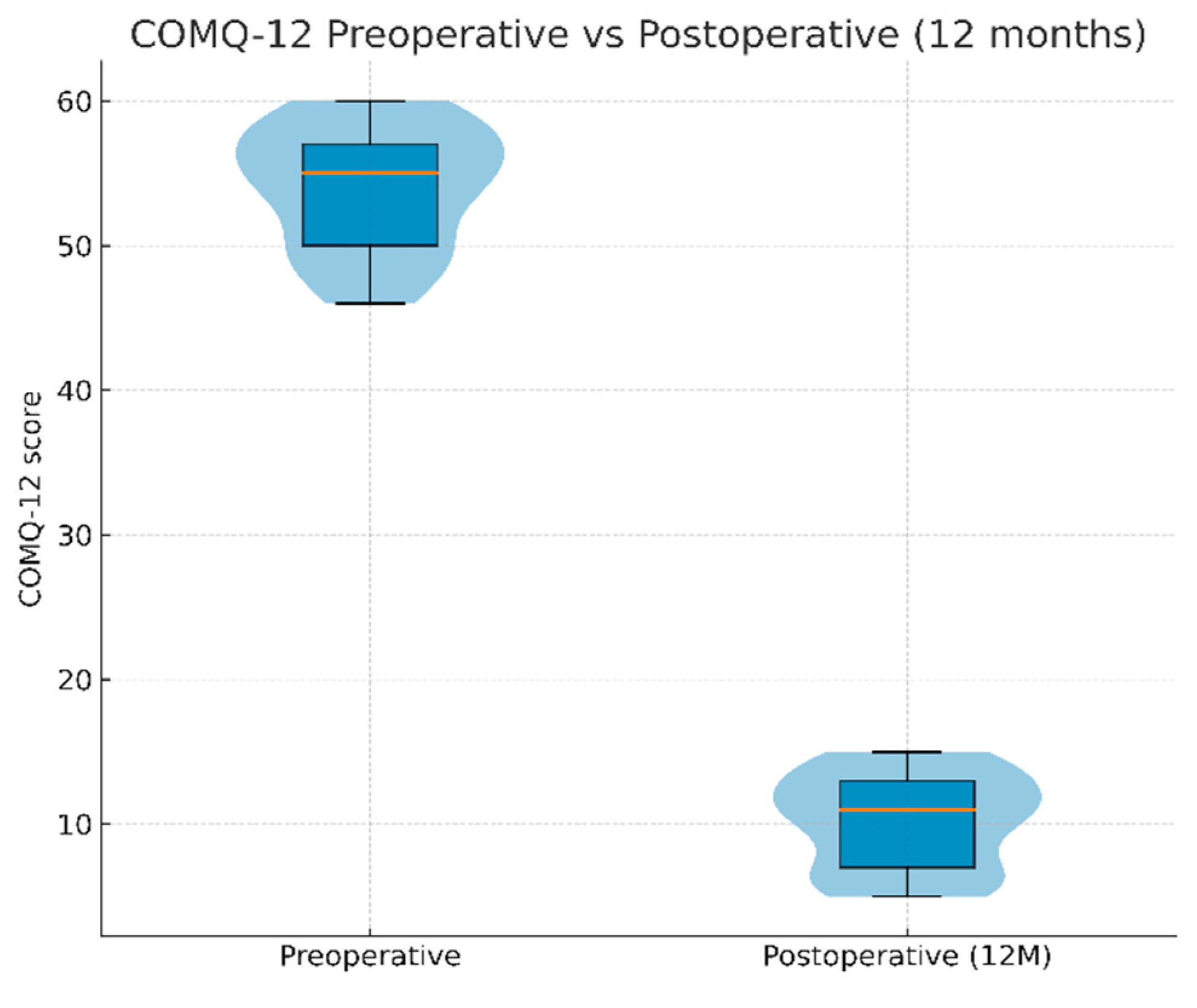

3.2. Quality of Life Outcomes

Preoperative COMQ-12 scores were high, indicating considerable symptom burden and disease-related impairment (mean 54.0 ± 4.2 out of 60). Postoperatively, COMQ-12 scores improved significantly at all assessed intervals. At 3 months, the mean COMQ-12 had decreased to 41.9 ± 7.2 (paired

t-test vs. baseline,

p < 0.001). Further improvement was observed by 6 months (38.0 ± 5.3,

p < 0.001 vs. baseline) and by 12 months (10.2 ± 3.3,

p < 0.001 vs. baseline). This corresponds to an average reduction of approximately ~44 points (≈81% improvement) in COMQ-12 scores from the preoperative baseline to 12 months, corresponding to an average decrease of approximately 44 points (≈81% improvement; 95% CI: –46.1 to –41.5).

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of COMQ-12 scores preoperatively and at 12 months, and detailed longitudinal results are presented in

Table 4.

Values are mean ± SD. Paired t-tests were used to compare each postoperative time point to the preoperative baseline; all postoperative scores were significantly improved compared to baseline (p < 0.001 for each comparison).

Patient-reported health benefit, as measured by the GBI, was positive at both postoperative time points and increased over time. At 6 months, the mean GBI score was 82.6 ± 4.8, indicating a high level of self-reported benefit. By 12 months, the mean GBI had further increased to 84.1 ± 4.9, a modest but statistically significant rise (mean difference 1.5, 95% CI: 0.8 to 2.2; p < 0.001; paired

t-test comparing 12 vs. 6 months,

p < 0.001). These findings indicate that patients experienced substantial and sustained improvement in health-related quality of life, with a slight additional gain between 6 and 12 months. The GBI outcomes are summarized in

Table 5.

3.3. Audiological Results

Audiometric evaluation demonstrated significant postoperative hearing improvement. The mean preoperative four-frequency pure-tone average air-conduction threshold was 52.1 ± 5.3 dB HL, which improved to 26.4 ± 4.7 dB HL at 12 months after surgery (paired t-test, p < 0.001). This improvement corresponds to an average hearing gain of approximately 25.7 dB (95% CI: 23.9 to 27.5), reflecting a substantial closure of the air-bone gap (mean hearing gain –25.7 dB; 95% CI: –27.5 to –23.9). Thus, in addition to quality-of-life gains, the exclusively endoscopic approach achieved meaningful audiological benefits for the cohort.

No major complications were encountered in our cohort. In particular, there were no cases of sensorineural hearing loss, facial nerve palsy, taste disturbance, or other significant postoperative complications.

3.4. Recurrence and Residual Disease

At 12 months postoperatively, all patients underwent non-EPI DWI MRI as part of the follow-up protocol. No cases of residual or recurrent cholesteatoma were identified. Accordingly, the recurrence rate in our cohort was 0% at 12 months. Importantly, even in patients who underwent DWI-MRI due to clinical suspicion of recurrence, no pathology was detected, further supporting the reliability of disease eradication with an exclusively endoscopic approach.

3.5. Correlations and Subgroup Analyses

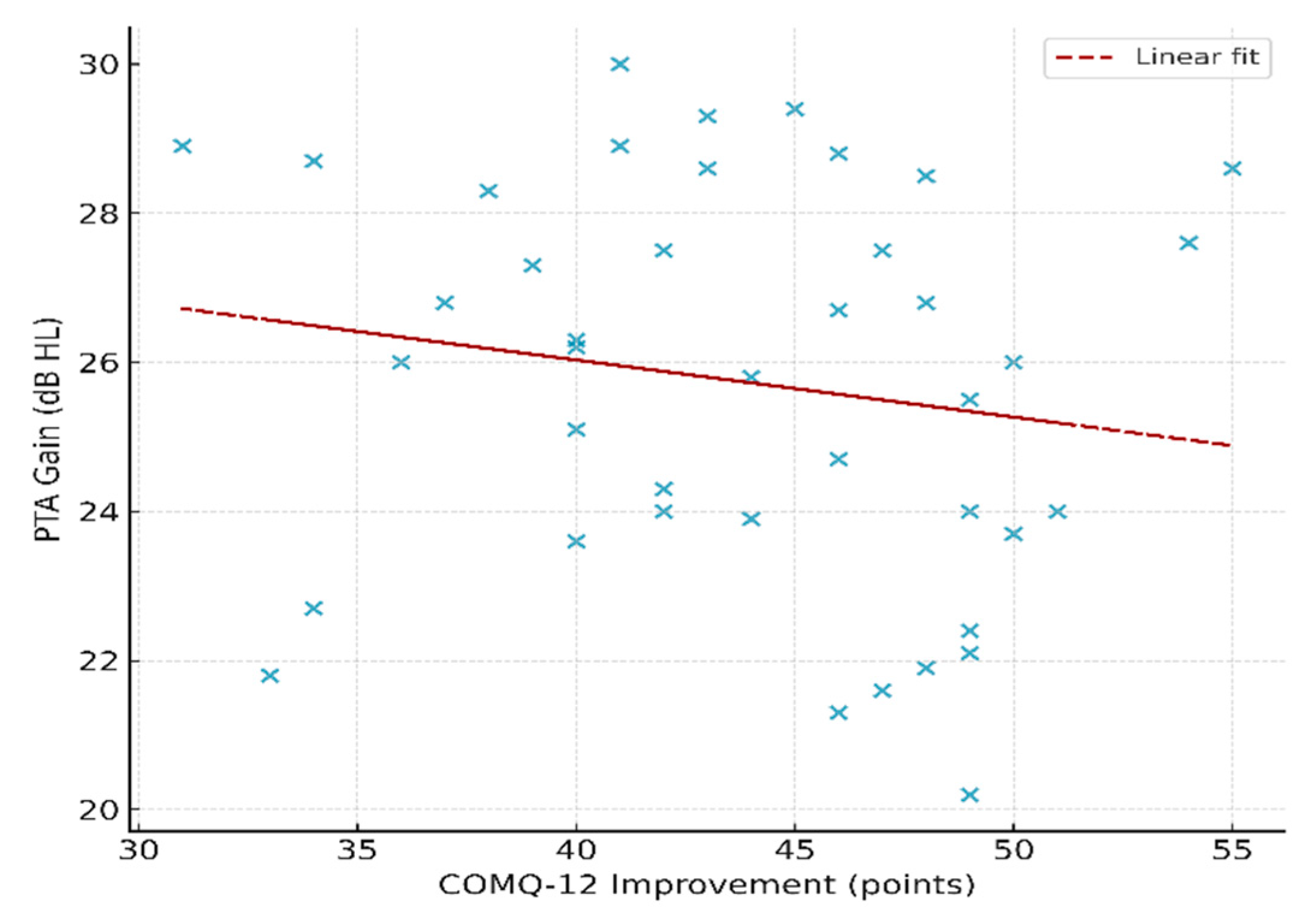

Correlation analyses did not show any significant relationships between hearing outcomes and patient-reported outcome measures. In particular, there was no significant correlation between the magnitude of COMQ-12 improvement (preoperative minus 12-month score) and the hearing gain in dB (Pearson

r = –0.16,

p = 0.31). Similarly, 12-month GBI scores showed no significant association with hearing gain (Spearman ρ = 0.11,

p = 0.50) or with patient age (Spearman ρ = –0.08,

p = 0.63). These findings suggest that improvements in hearing and quality of life were largely independent of each other and were not influenced by patient age. The scatter plot in

Figure 5 illustrates the lack of correlation between COMQ-12 improvement and hearing gain, and the correlation results for all variables are detailed in

Table 4.

Table 6.

Correlations between patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), audiological outcomes, and patient variables. Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients (r/ρ) are shown as appropriate (Pearson used for normally-distributed differences, Spearman for ordinal/non-normal data). n = 41 for all analyses. No statistically significant correlations were observed. (PTA = pure-tone average hearing level gain in dB; COMQ-12 improvement = decrease in COMQ-12 score from preop to 12 months.).

Table 6.

Correlations between patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), audiological outcomes, and patient variables. Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients (r/ρ) are shown as appropriate (Pearson used for normally-distributed differences, Spearman for ordinal/non-normal data). n = 41 for all analyses. No statistically significant correlations were observed. (PTA = pure-tone average hearing level gain in dB; COMQ-12 improvement = decrease in COMQ-12 score from preop to 12 months.).

| Variable 1 |

Variable 2 |

n |

Method |

Correlation (r/ρ) |

p-value

|

| COMQ-12 improvement |

PTA gain (dB) |

41 |

Pearson |

–0.16 |

0.31 |

| GBI (12 months) |

PTA gain (dB) |

41 |

Spearman |

0.11 |

0.50 |

| GBI (12 months) |

Age (years) |

41 |

Spearman |

–0.08 |

0.63 |

| COMQ-12 score (12 months) |

Age (years) |

41 |

Spearman |

0.17 |

0.30 |

Subgroup analyses similarly revealed no significant differences in outcomes based on surgical subgroup or disease stage. Patients were stratified by type of ossiculoplasty performed (none, cartilage graft, PORP, TORP), but no significant differences were found among these groups in mean COMQ-12 improvement or in 12-month GBI scores (one-way ANOVA for both comparisons; p > 0.4 in each case). There was also no association between the type of ossicular reconstruction and the incidence of cholesteatoma recurrence on follow-up MRI (chi-square test, p = 0.65). Furthermore, outcome measures did not differ significantly according to disease extent: patients with cholesteatomas not involving the anterior epitympanic recess (S1) and the sinus tympani (S2) had postoperative COMQ-12 and GBI results comparable to those with cholesteatomas extending into these areas (no significant between-group differences, p > 0.5). Thus, within this cohort, the extent of disease and the type of reconstruction did not appear to influence the degree of hearing recovery or quality-of-life improvement achieved. We consider that the dynamics of hearing recovery are better explained by the limited stage of the disease.

3.6. Summary of Key Findings

In summary, exclusive endoscopic surgery for middle ear cholesteatoma resulted in a marked reduction in disease-specific symptoms and consistently high patient-reported benefit over 12 months. Significant audiological improvements were also attained, although the magnitude of hearing gain did not correlate with the extent of quality-of-life improvement across patients.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings

The present prospective cohort study demonstrates that exclusive endoscopic management of middle ear cholesteatoma is associated with significant improvements in patient-reported quality of life. COMQ-12 scores decreased markedly at all postoperative intervals, reflecting both symptom relief and reduced disease impact. Meanwhile, GBI scores confirmed a sustained perception of benefit, with further improvements observed between the 6- and 12-month follow-ups. In practical terms, patients experienced a marked improvement in disease burden, with COMQ-12 scores dropping by about 44 points (95% CI: –46.1 to –41.5). At the same time, they reported a sustained benefit in quality of life, as reflected by a 1.5-point increase in GBI (95% CI: 0.8 to 2.2). Importantly, hearing function also improved significantly, with a mean gain of 25.7 dB (95% CI: –27.5 to –23.9), indicating a substantial closure of the air–bone gap. These findings emphasize that endoscopic surgery not only eradicates the disease but also yields measurable, patient-centered improvements[

38,

39].

Our findings align with a growing body of evidence highlighting the advantages of endoscopic ear surgery over traditional microscopic approaches[

40,

41]. Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that cholesteatoma recurrence and residual disease rates are lower with endoscopic techniques[

42]. This is largely attributed to the endoscope’s wide-angle visualization, which allows inspection of hidden recesses such as the sinus tympani and anterior epitympanum[

43]. For example, Li et al. (2021) analyzed 13 studies and found that the recurrence risk was nearly halved with endoscopic surgery (RR ≈ 0.51), and residual cholesteatomas were significantly less frequent (RR ≈ 0.68) compared to microscopic surgery[

44]. Similarly, a systematic review by Nair et al. (2022) confirmed lower recurrence rates with exclusively endoscopic techniques[

45]. These benefits extend to pediatric populations as well. Basonbul et al. (2021) reported that using endoscopes for cholesteatoma removal halved the residual disease rate (RR = 0.48, p < 0.001) compared to conventional methods[

46].

In our cohort, the recurrence rate was 0% at 12 months, confirmed by non-EPI DWI MRI. While encouraging, longer-term follow-up is required, since late recurrences beyond the first postoperative year are well-documented in the literature. However, the 12-month follow-up period remains relatively short, and late recurrences are well documented in the literature. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted with caution, and longer-term surveillance is warranted to confirm the durability of disease control.

Evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCT) also supports these findings. In a recent RCT, Hamel et al. (2023) showed that endoscopically treated patients had significantly lower recurrence (7.5% vs. 27.5%) and residual disease rates (5.0% vs. 22.5%) compared to those who underwent conventional microscopic tympanoplasty[

47]. Importantly, these advantages were achieved without compromising surgical access or increasing morbidity, confirming that enhanced visualization of hidden areas can translate into clinically relevant benefits[

48]

With respect to hearing outcomes, most studies report no significant differences between endoscopic and microscopic approaches. Meta-analyses have consistently found that both techniques achieve comparable postoperative air–bone gap closures and overall audiological outcomes[

45,

49]. While some series suggest that the endoscopic approach can facilitate ossicular preservation due to better visualization around the ossicular chain, the overall magnitude of hearing gain has not differed significantly between techniques[

50]

In our cohort, hearing outcomes improved markedly, yet this improvement was not directly mirrored by changes in PROM scores, reinforcing the notion that QoL and audiological gains may evolve independently. Patient-reported outcomes are an increasingly important measure of surgical success. Raemy et al. (2025) compared postoperative QoL in patients undergoing endoscopic versus microscopic cholesteatoma surgery and observed higher QoL scores in the endoscopic cohort, although the difference was not statistically significant - likely due to limited sample size or case selection[

51]. Our findings reinforce this trend by demonstrating a significant, sustained improvement in QoL after exclusive endoscopic surgery. In addition to QoL gains, prior studies have noted other advantages of endoscopic techniques, including less postoperative pain, faster wound healing, and better cosmetic outcomes[

52]. For example, Hamel et al. reported that tympanic membrane grafts healed about two weeks faster in the endoscopic group compared to the microscopic cohort in their randomized trial [

47].

Regarding safety and complications, both approaches are generally considered safe, with low rates of major adverse events[

53,

54]Indeed, comparative series report no significant differences in overall complication rates between endoscopic and microscopic surgery. However, certain specific morbidities may be less frequent with endoscopy. For example, Otsuka et al. (2024) reported that taste disturbance from chorda tympani injury occurred in 11% of microscopic cases but in 0% of endoscopic cases—a statistically significant disparity[

55]. Similarly, wound infections and postoperative balance disturbances have been reported less often with endoscopic procedures, although these differences do not always reach statistical significance[

56].

Taken together, evidence from the past decade suggests that endoscopic cholesteatoma surgery yields outcomes at least comparable to - and in some respects superior to - those of traditional microscopic techniques[

57] In appropriately selected cases, an exclusively endoscopic approach can offer lower recurrence rates, equivalent hearing outcomes, improved patient-reported outcomes, and a smoother recovery[

58]. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that most endoscopic series have involved relatively limited disease; in cases of extensive mastoid involvement, the microscope remains indispensable[

59] An individualized approach - tailoring the surgical technique to the disease extent and anatomic conditions, therefore remains essential[

60]

4.2. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the relatively small sample size (n = 41) and single-center design may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, the follow-up period was limited to 12 months; Although no recurrences were identified after 1 year, the reported 0% recurrence rate should be interpreted cautiously, as relapses beyond the first postoperative year are common. This underscores the need for extended follow-up to assess the long-term efficacy of exclusive endoscopic cholesteatoma surgery fully. Third, the strict inclusion criteria, selecting only patients amenable to an exclusively endoscopic approach, ensured homogeneity but also limited the applicability of the results to patients with more extensive cholesteatomas requiring microscopic or combined approaches. Finally, the absence of a control group treated with conventional microscopic surgery precludes direct comparison; therefore, we relied on data from the existing literature for contextualization. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable prospective evidence that exclusive endoscopic surgery can achieve substantial improvements in quality of life and hearing, with a very low recurrence rate in appropriately selected cases.

5. Conclusions

This prospective study demonstrates that exclusive endoscopic cholesteatoma surgery can achieve significant improvements in both patient-reported and clinical outcomes[

61] Postoperatively, patients experienced marked quality-of-life gains - evidenced by improved COMQ-12 and GBI scores - alongside meaningful hearing improvements. Notably, we found no correlation between the extent of hearing gain and QoL improvement, suggesting that audiological success does not automatically translate into better patient-perceived outcomes; this highlights the importance of directly measuring patient-reported benefits in chronic ear disease[

62,

63]Furthermore, the positive outcomes in our cohort were consistent across different surgical scenarios: we observed no significant variation in results based on the ossiculoplasty type or cholesteatoma stage. This suggests that the advantages of the endoscopic approach are broadly applicable, with effective disease control and functional recovery achievable even in advanced-stage disease and regardless of reconstruction technique[

64,

65]

Collectively, these findings underscore that an exclusively endoscopic approach to cholesteatoma is a safe, feasible, and patient-centered surgical strategy. By avoiding external incisions and providing wide-angle visualization of the middle ear, this minimally invasive technique enables thorough cholesteatoma eradication while minimizing morbidity, aligning with prior reports of endoscopic ear surgery as a “safe and effective transcanal alternative” to conventional postauricular procedures[

66]. Looking ahead, longer-term follow-up is warranted to assess the durability of cholesteatoma control and hearing outcomes after endoscopic surgery, and multicenter studies would help validate these results across diverse populations[

67,

68]. Additionally, we recommend integrating patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) into routine practice and future research, ensuring that surgical success is consistently defined not only by objective measures but also by genuine improvements in patients’ daily lives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.-M.G., V.Z., A.R. and R.H.; methodology, L.-M.G., A.R. and V.Z.; software, —L.-M.G., V.Z., T.E., R.H., A.R., I.-G.I., O.A. ; validation, L.-M.G., V.Z. and R.H.; formal analysis, O.A., I.-G.I. and C.V.; investigation, L.-M.G. and A.R.; resources, V.Z. and R.H.; data curation, L.-M.G., V.Z., T.E., R.H., A.R., I.-G.I., O.A.; writing—original draft preparation, L.-M.G., V.Z., T.E., R.H., A.R., I.-G.I., O.A. and C.V.; writing—review and editing, L.-M.G., V.Z., T.E., R.H., A.R., I.-G.I., O.A. and C.V.; visualization, O.A., I.-G.I. and C.V.; supervision, V.Z., ; project administration, V.Z. and R.H.; funding acquisition, L.-M.G., (Publish not Perish 2025, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the “Publish not Perish 2025” program of Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the “Prof. Dr. Hociota” Institute of Phonoaudiology and ENT Functional Surgery (approval code: 8696) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA; GPT-5, 2025) for the purposes of figure preparation. The authors have reviewed and edited all output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABG |

Air–Bone Gap |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| Bax |

Bcl-2-associated X protein |

| Bcl-2 |

B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| CES |

Endoscopic classification of the external auditory canal |

| ChOLE |

Cholesteatoma extension, Ossicular chain status, Life-threatening complications, and Eustachian tube/mastoid status |

| COMQ-12 |

Chronic Otitis Media Questionnaire-12 |

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| DWI-MRI |

Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| EAONO |

European Academy of Otology and Neuro-Otology |

| EES |

Endoscopic Ear Surgery |

| EGF |

Epidermal Growth Factor |

| GBI |

Glasgow Benefit Inventory |

| IHC |

Immunohistochemistry |

| IL |

Interleukin |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| JOS |

Japanese Otological Society |

| LMP |

Low Molecular Mass Polypeptide |

| MMP |

Matrix Metalloproteinase |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| OPG |

Osteoprotegerin |

| PCNA |

Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen |

| PROMs |

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures |

| PTA |

Pure-Tone Average |

| QoL |

Quality of Life |

| RANKL |

Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-Β Ligand |

| RCT |

Randomized Controlled Trial |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| STAMCO |

S – difficult visualisation areas, TAMCO - Tympanic cavity, Attic, Mastoid, Complications, and Ossicular chain involvement |

| TGF-β |

Transforming Growth Factor-beta |

| TNF-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

References

- Kemppainen, H.O.; Puhakka, H.J.; Laippala, P.J.; Sipilä, M.M.; Manninen, M.P.; Karma, P.H. Epidemiology and Aetiology of Middle Ear Cholesteatoma. Acta Otolaryngol 1999, 119, 568–572, doi:10.1080/00016489950180801.

- Castle, J.T. Cholesteatoma Pearls: Practical Points and Update. Head Neck Pathol 2018, 12, 419–429, doi:10.1007/S12105-018-0915-5.

- Yung, M.; Tono, T.; Olszewska, E.; Yamamoto, Y.; Sudhoff, H.; Sakagami, M.; Mulder, J.; Kojima, H.; İncesulu, A.; Trabalzini, F.; et al. EAONO/JOS Joint Consensus Statements on the Definitions, Classification and Staging of Middle Ear Cholesteatoma. Journal of International Advanced Otology 2017, 13, 1–8, doi:10.5152/IAO.2017.3363.

- Linder, T.E.; Shah, S.; Martha, A.S.; Röösli, C.; Emmett, S.D. Introducing the “ChOLE” Classification and Its Comparison to the EAONO/JOS Consensus Classification for Cholesteatoma Staging. Otology and Neurotology 2019, 40, 63–72, doi:10.1097/MAO.0000000000002039,.

- Hu, Y.; Teh, B.M.; Hurtado, G.; Yao, X.; Huang, J.; Shen, Y. Can Endoscopic Ear Surgery Replace Microscopic Surgery in the Treatment of Acquired Cholesteatoma? A Contemporary Review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2020, 131, doi:10.1016/J.IJPORL.2020.109872.

- Tarabichi, M.; Nogueira, J.F.; Marchioni, D.; Presutti, L.; Pothier, D.D.; Ayache, S. Transcanal Endoscopic Management of Cholesteatoma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2013, 46, 107–130, doi:10.1016/J.OTC.2012.10.001.

- Bonali, M.; Marchioni, D.; Bisi, N. Endoscopic Ear Surgery: Past and Future. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 2022, 10, 343–348, doi:10.1007/S40136-022-00424-3/FIGURES/1.

- Bianconi, L.; Gazzini, L.; Laura, E.; De Rossi, S.; Conti, A.; Marchioni, D. Endoscopic Stapedotomy: Safety and Audiological Results in 150 Patients. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 2020, 277, 85–92, doi:10.1007/s00405-019-05688-y.

- Bassiouny, M.; Badour, N.; Omran, A.; Osama, H. Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Characteristics of Acquired Cholesteatoma in Children and Adults. Egyptian Journal of Ear, Nose, Throat and Allied Sciences 2012, 13, 7–12, doi:10.1016/j.ejenta.2012.02.007.

- Bologa, R.A.; Anghelina, F.; Mitroi, M.R.; Ciolofan, M.S.; Mogoantă, C.A.; Căpitănescu, A.N.; Grecu, A.F.; Anghelina, L.; Botezat, M.M.; Mogoş, A.A.; et al. Biology of Recurrent Cholesteatoma in a Romanian Young Patient – a Case Report. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology 2024, 65, 775–780, doi:10.47162/RJME.65.4.24.

- Dornelles, C.; da Costa, S.S.; Meurer, L.; Schweiger, C. Correlation of Cholesteatomas Perimatrix Thickness with Patient’s Age. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2005, 71, 792–797, doi:10.1016/s1808-8694(15)31250-7.

- Kennedy, K.L.; Singh, A.K. Middle Ear Cholesteatoma. StatPearls 2024.

- Imai, R.; Sato, T.; Iwamoto, Y.; Hanada, Y.; Terao, M.; Ohta, Y.; Osaki, Y.; Imai, T.; Morihana, T.; Okazaki, S.; et al. Osteoclasts Modulate Bone Erosion in Cholesteatoma via RANKL Signaling. JARO - Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology 2019, 20, 449–459, doi:10.1007/S10162-019-00727-1,.

- Espahbodi, M.; Samuels, T.L.; McCormick, C.; Khampang, P.; Yan, K.; Marshall, S.; McCormick, M.E.; Chun, R.H.; Harvey, S.A.; Friedland, D.R.; et al. Analysis of Inflammatory Signaling in Human Middle Ear Cell Culture Models of Pediatric Otitis Media. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, 410–416, doi:10.1002/LARY.28687.

- Bassiouny, M.; Badour, N.; Omran, A.; Osama, H. Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Characteristics of Acquired Cholesteatoma in Children and Adults. Egyptian Journal of Ear, Nose, Throat and Allied Sciences 2012, 13, 7–12, doi:10.1016/J.EJENTA.2012.02.007.

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. PLoS Med 2007, 4, 1623–1627, doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296.

- J, P.; Haggard, Y.M. Chronic Otitis Media Questionnaire-12 (COMQ-12).

- Glasgow Health Status Questionnaires Manual Available online: https://studylib.net/doc/8450311/the-health-status-questionnaires-manual (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Quality of Life after Cholesteatoma Surgery: Comparison between Surgical Techniques. - Abstract - Europe PMC Available online: https://europepmc.org/article/PMC/9330745 (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Phillips, J.S.; Tailor, B. V.; Nunney, I.; Yung, M.W.; Doruk, C.; Kara, H.; Kong, T.; Quaranta, N.; Peñaranda, A.; Bernardeschi, D.; et al. Impact of Hearing Disability and Ear Discharge on Quality-of-Life in Patients with Chronic Otitis Media: Data from the Multinational Collaborative COMQ-12 Study. Otology and Neurotology 2021, 42, E1507–E1512, doi:10.1097/MAO.0000000000003299.

- EL-Meselaty, K.; Badr-El-Dine, M.; Mandour, M.; Mourad, M.; Darweesh, R. Endoscope Affects Decision Making in Cholesteatoma Surgery. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery 2003, 129, 490–496, doi:10.1016/S0194-5998(03)01577-8.

- Van Der Toom, H.F.E.; Van Der Schroeff, M.P.; Janssen, J.M.H.; Westzaan, A.M.; Pauw, R.J. A Retrospective Analysis and Comparison of the STAM and STAMCO Classification and EAONO/JOS Cholesteatoma Staging System in Predicting Surgical Treatment Outcomes of Middle Ear Cholesteatoma. Otology and Neurotology 2020, 41, e468–e474, doi:10.1097/MAO.0000000000002549.

- ten Tije, F.A.; Merkus, P.; Buwalda, J.; Blom, H.M.; Kramer, S.E.; Pauw, R.J.; Nyst, H.J.; van der Putten, L.; Graveland, A.P.; Kingma, G.G.; et al. Practical Applicability of the STAMCO and ChOLE Classification in Cholesteatoma Care. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 2021, 278, 3777–3787, doi:10.1007/S00405-020-06478-7.

- Choi, J.E.; Kang, W.S.; Lee, J.D.; Chung, J.W.; Kong, S.K.; Lee, I.W.; Moon, I.J.; Hur, D.G.; Moon, I.S.; Cho, H.H. Outcomes of Endoscopic Congenital Cholesteatoma Removal in South Korea. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2023, 149, 231, doi:10.1001/JAMAOTO.2022.4660.

- Yong, M.; Mijovic, T.; Lea, J. Endoscopic Ear Surgery in Canada: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery 2016, 45, doi:10.1186/S40463-016-0117-7,.

- Badr-El-Dine, M.; James, A.L.; Panetti, G.; Marchioni, D.; Presutti, L.; Nogueira, J.F. Instrumentation and Technologies in Endoscopic Ear Surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2013, 46, 211–225, doi:10.1016/J.OTC.2012.10.005.

- Couvreur, F.; Loos, E.; Desloovere, C.; Verhaert, N. Efficacy of Otoendoscopy for Residual Cholesteatoma Detection During Microscopic Chronic Ear Surgery. J Int Adv Otol 2024, 20, 225, doi:10.5152/IAO.2024.231122.

- Badr-el-Dine, M. Value of Ear Endoscopy in Cholesteatoma Surgery. Otology and Neurotology 2002, 23, 631–635, doi:10.1097/00129492-200209000-00004.

- Bächinger, D.; Rrahmani, A.; Weiss, N.M.; Mlynski, R.; Huber, A.; Röösli, C. Evaluating Hearing Outcome, Recidivism and Complications in Cholesteatoma Surgery Using the ChOLE Classification System. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 2020, 278, 1365, doi:10.1007/S00405-020-06208-Z.

- Henninger, B.; Kremser, C. Diffusion Weighted Imaging for the Detection and Evaluation of Cholesteatoma. World J Radiol 2017, 9, 217, doi:10.4329/WJR.V9.I5.217.

- Yiğiter, A.C.; Pınar, E.; İmre, A.; Erdoğan, N. Value of Echo-Planar Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Detecting Tympanomastoid Cholesteatoma. Journal of International Advanced Otology 2015, 11, 53–57, doi:10.5152/IAO.2015.447.

- Phillips, J.S.; Yung, M.W.; Nunney, I.; Doruk, C.; Kara, H.; Kong, T.; Quaranta, N.; Peñaranda, A.; Bernardeschi, D.; Dai, C.; et al. Multinational Appraisal of the Chronic Otitis Media Questionnaire 12 (COMQ-12). Otology and Neurotology 2021, 42, e45–e49, doi:10.1097/MAO.0000000000002845,.

- Bukurov, B.; Haggard, M.; Spencer, H.; Arsovic, N.; Grujicic, S.S. Can Short PROMs Support Valid Factor-Based Sub-Scores? Example of COMQ-12 in Chronic Otitis Media. PLoS One 2022, 17, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0274513.

- Taneja, V.; Milner, T.D.; Iyer, A. Endoscopic Ear Surgery: Does It Have an Impact on Quality of Life? Our Experience of 152 Cases. Clinical Otolaryngology 2020, 45, 126–129, doi:10.1111/COA.13459;WGROUP:STRING:PUBLICATION.

- Rutkowska, J.; Kasacka, I.; Rogowski, M.; Olszewska, E. Immunohistochemical Identification and Assessment of the Location of Immunoproteasome Subunits LMP2 and LMP7 in Acquired Cholesteatoma. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, doi:10.3390/IJMS241814137,.

- Schürmann, M.; Oppel, F.; Shao, S.; Volland-Thurn, V.; Kaltschmidt, C.; Kaltschmidt, B.; Scholtz, L.U.; Sudhoff, H. Chronic Inflammation of Middle Ear Cholesteatoma Promotes Its Recurrence via a Paracrine Mechanism. Cell Commun Signal 2021, 19, 25, doi:10.1186/S12964-020-00690-Y.

- Ayache, S.; Beltran, M.; Guevara, N. Endoscopic Classification of the External Auditory Canal for Transcanal Endoscopic Ear Surgery. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2019, 136, 247–250, doi:10.1016/J.ANORL.2019.03.005.

- Yiannakis, C.P.; Sproat, R.; Iyer, A. Preliminary Outcomes of Endoscopic Middle-Ear Surgery in 103 Cases: A UK Experience. Journal of Laryngology and Otology 2018, 132, 493–496, doi:10.1017/S0022215118000695.

- Elfeky, A.E.M.; Khazbzk, A.O.; Nasr, W.F.; Emara, T.A.; Elanwar, M.W.; Amer, H.S.; Fouad, Y.A. Outcomes of Using Otoendoscopy During Surgery for Cholesteatoma. Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery 2019, 71, 1036–1039, doi:10.1007/S12070-017-1084-7.

- Barakate, M.; Bottrill, I. Combined Approach Tympanoplasty for Cholesteatoma: Impact of Middle-Ear Endoscopy. Journal of Laryngology and Otology 2008, 122, 120–124, doi:10.1017/S0022215107009346.

- Ayache, S.; Tramier, B.; Strunski, V. Otoendoscopy in Cholesteatoma Surgery of the Middle Ear: What Benefits Can Be Expected? Otology and Neurotology 2008, 29, 1085–1090, doi:10.1097/MAO.0B013E318188E8D7.

- Verma, B.; Dabholkar, Y.G. Role of Endoscopy in Surgical Management of Cholesteatoma: A Systematic Review. J Otol 2020, 15, 166, doi:10.1016/J.JOTO.2020.06.004.

- Sarcu, D.; Isaacson, G. Long-Term Results of Endoscopically Assisted Pediatric Cholesteatoma Surgery. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery (United States) 2016, 154, 535–539, doi:10.1177/0194599815622441.

- Li, B.; Zhou, L.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zou, J. Endoscopic versus Microscopic Surgery for Treatment of Middle Ear Cholesteatoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Otolaryngol 2021, 42, 102451, doi:10.1016/J.AMJOTO.2020.102451.

- Nair, S.; Aishwarya, J.G.; Warrier, N.; Pavithra, V.; Jain, A.; Shamim, M.; Ramanathan, K.; Vasu, P.K. Endoscopic Ear Surgery in Middle Ear Cholesteatoma. Laparosc Endosc Robot Surg 2021, 4, 24–29, doi:10.1016/J.LERS.2021.01.004.

- Basonbul, R.A.; Ronner, E.A.; Kozin, E.D.; Lee, D.J.; Cohen, M.S. Systematic Review of Endoscopic Ear Surgery Outcomes for Pediatric Cholesteatoma. Otology and Neurotology 2021, 42, 108–115, doi:10.1097/MAO.0000000000002876,.

- Hamela, M.A.A.; Abd-Elnaseer, O.; El-Dars, M.M.; El-Antably, A. Comparison of the Outcomes of Endoscopic versus Microscopic Approach in Cholesteatoma Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Study. Egyptian Journal of Otolaryngology 2023, 39, 1–5, doi:10.1186/S43163-023-00492-2/TABLES/3.

- Migirov, L.; Shapira, Y.; Horowitz, Z.; Wolf, M. Exclusive Endoscopic Ear Surgery for Acquired Cholesteatoma: Preliminary Results. Otol Neurotol 2011, 32, 433–436, doi:10.1097/mao.0b013e3182096b39.

- Cohen, M.S.; Basonbul, R.A.; Kozin, E.D.; Lee, D.J. Residual Cholesteatoma during Second-Look Procedures Following Primary Pediatric Endoscopic Ear Surgery. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery (United States) 2017, 157, 1034–1040, doi:10.1177/0194599817729136.

- Bae, M.R.; Kang, W.S.; Chung, J.W. Comparison of the Clinical Results of Attic Cholesteatoma Treatment: Endoscopic versus Microscopic Ear Surgery. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 2019, 12, 156–162, doi:10.21053/ceo.2018.00507.

- Raemy, Y.; Bächinger, D.; Peter, N.; Roosli, C. Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients after Endoscopic or Microscopic Cholesteatoma Surgery. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 2025, 282, 2275–2283, doi:10.1007/S00405-024-09097-8/FIGURES/5.

- Pollak, N. Endoscopic and Minimally-Invasive Ear Surgery: A Path to Better Outcomes. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017, 3, 129–135, doi:10.1016/j.wjorl.2017.08.001.

- James, A.L. Endoscopic Middle Ear Surgery in Children. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2013, 46, 233–244, doi:10.1016/J.OTC.2012.10.007.

- Tarabichi, M. Endoscopic Management of Limited Attic Cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope 2004, 114, 1157–1162, doi:10.1097/00005537-200407000-00005.

- Otsuka, A.; Koyama, H.; Kashio, A.; Matsumoto, Y.; Yamasoba, T. Comparison of Endoscopic and Microscopic Surgery for the Treatment of Acquired Cholesteatoma by EAONO/JOS Staging. Healthcare (Switzerland) 2024, 12, 1737, doi:10.3390/HEALTHCARE12171737/S1.

- Chiao, W.; Chieffe, D.; Fina, M. Endoscopic Management of Primary Acquired Cholesteatoma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2021, 54, 129–145, doi:10.1016/J.OTC.2020.09.014.

- Dalğıç, A.; Aksoy Yıldırım, G.; Zorlu, M.E.; Delice, O.; Aysel, A. Total Transcanal Endoscopic Ear Surgery for Cholesteatoma. Turk Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2023, 61, 1–7, doi:10.4274/TAO.2023.2022-11-6.

- Marchioni, D.; Alicandri-Ciufelli, M.; Piccinini, A.; Genovese, E.; Presutti, L. Inferior Retrotympanum Revisited: An Endoscopic Anatomic Study. Laryngoscope 2010, 120, 1880–1886, doi:10.1002/LARY.20995.

- Kuo, C.L.; Shiao, A.S.; Yung, M.; Sakagami, M.; Sudhoff, H.; Wang, C.H.; Hsu, C.H.; Lien, C.F. Updates and Knowledge Gaps in Cholesteatoma Research. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, doi:10.1155/2015/854024.

- Marchioni, D.; Soloperto, D.; Rubini, A.; Villari, D.; Genovese, E.; Artioli, F.; Presutti, L. Endoscopic Exclusive Transcanal Approach to the Tympanic Cavity Cholesteatoma in Pediatric Patients: Our Experience. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2015, 79, 316–322, doi:10.1016/J.IJPORL.2014.12.008.

- The Efficacy of Transcanal Endoscopic Ear Surgery in Children Compared to Adults - PubMed Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40310232/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Dornhoffer, J.L.; Friedman, A.B.; Gluth, M.B. Management of Acquired Cholesteatoma in the Pediatric Population. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013, 21, 440–445, doi:10.1097/MOO.0B013E32836464BD.

- Kuo, C.L.; Liao, W.H.; Shiao, A.S. A Review of Current Progress in Acquired Cholesteatoma Management. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 2015, 272, 3601–3609, doi:10.1007/S00405-014-3291-0.

- Ito, T.; Kubota, T.; Watanabe, T.; Futai, K.; Furukawa, T.; Kakehata, S. Transcanal Endoscopic Ear Surgery for Pediatric Population with a Narrow External Auditory Canal. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2015, 79, 2265–2269, doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.10.019.

- Miller, K.A.; Fina, M.; Lee, D.J. Principles of Pediatric Endoscopic Ear Surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2019, 52, 825–845, doi:10.1016/j.otc.2019.06.001.

- Dixon, P.R.; James, A.L. Evaluation of Residual Disease Following Transcanal Totally Endoscopic vs Postauricular Surgery among Children with Middle Ear and Attic Cholesteatoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020, 146, 408–413, doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0001.

- Bovi, C.; Luchena, A.; Bivona, R.; Borsetto, D.; Creber, N.; Danesi, G. Recurrence in Cholesteatoma Surgery: What Have We Learnt and Where Are We Going? A Narrative Review. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica 2023, 43, S48, doi:10.14639/0392-100X-SUPPL.1-43-2023-06.

- Tomlin, J.; Chang, D.; McCutcheon, B.; Harris, J. Surgical Technique and Recurrence in Cholesteatoma: A Meta-Analysis. Audiology and Neurotology 2013, 18, 135–142, doi:10.1159/000346140.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).