1. Introduction

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at risk of contracting COVID-19 through their work due to extended exposure to patients with the virus. European studies reported cluster outbreaks among HCWs before implementing universal mask-wearing and other non-pharmaceutical measures[

1]. Similarly, cluster outbreaks occurred in China and London, where transmission was limited to community spread, reinforcing the evidence of transmission from SARS-CoV-2-positive patients[

2].

In the context of Sub-Saharan Africa, the risk to HCWs remains significant. Studies have shown that HCWs in this region are at a higher risk of infection[

3]. The seroprevalence among HCWs ranged from 0% to 45.1%, with factors such as old age, working as a nurse, and lower education levels associated with higher seropositivity rates[

4]. HCWs and patients admitted for non-Covid- 19 related conditions are particularly vulnerable to infection. HCWs in direct contact with patients are susceptible to transmittable diseases and may play a role in the nosocomial transmission of infectious diseases[

5].

Furthermore, factors such as age and overall health play a significant role in COVID-19 outcomes. For instance, younger adults generally experience better health outcomes following SARS-COV-2 infection, and children are minimally affected[

6]. On the other hand, comorbidities like metabolic disorders and cardiovascular conditions have been identified as risk factors for severe COVID-19 outcomes[

7]. Furthermore, a systematic review indicated that conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, respiratory and renal diseases, malignancies, nervous system diseases, and diabetes are linked to higher mortality rates among the elderly[

8]8.

Initially, vaccination initiatives prioritised healthcare workers (HCWs), older people, and individuals with pre-existing conditions[

9]. However, vaccine shortages in developing countries necessitated concentrating efforts solely on HCWs [

10]. For example, South Africa's Sisonke vaccination initiative, which commenced on 17 February 2021, aimed to vaccinate all HCWs aged 18 and above[

11]. The Sisonke Initiative was a Phase 3b study initiative using the Ad26.COV2.S COVID-19 vaccine. The Ad26.COV2.S vaccine, a recombinant adenovirus vector encoding the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, has demonstrated efficacy against COVID-19 in clinical trials[

12].

Despite the rapid development of vaccines, most of those recommended demonstrated efficacy and effectiveness, significantly reducing infection rates, severity, hospitalisations, and mortality[13, 14] in real-world settings. Meta-analyses show that full vaccination provides 87-89% protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection and over 90% protection against severe outcomes like hospitalisation and death[15, 16].

As the pandemic progressed, mutations in the spike protein led to increased transmissibility and the potential for immune evasion after both natural infection and vaccination [

17]17. For example, the Omicron variant was more transmissible but associated with less severe disease[

18]18. Omicron possesses more spike protein mutations than other SARS-CoV-2 variants, including six unique mutations in the S2 region[

19]. Although the effectiveness of the vaccines against Omicron was reduced, the vaccinated individuals had better protection than their nonvaccinated counterparts[

20]. This variable protection of vaccines against Omicron necessitates ongoing surveillance, particularly among at-risk populations such as healthcare workers.

The study aimed to estimate the proportion of COVID-19 infections among HCWs in a tertiary teaching hospital in Gauteng province, to describe the characteristics of HCWs with positive polymerase chain reaction test (PCR), to determine the point prevalence of COVID-19 infections; to estimate the risk factors associated with COVID-19 infection and the proportion of breakthrough infections among those vaccinated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional record review of healthcare workers (HCWs) employed at a tertiary academic hospital in Gauteng Province, South Africa. The hospital is a referral centre with approximately 1330 beds and a workforce of about 5000 staff, representing multiple professional categories. The study period extended from 12 May 2021 to 11 May 2022, covering the third and fourth COVID-19 waves in South Africa.

2.2. Study Population

The study population comprised HCWs with a laboratory-confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 who attended the Occupational Health Service (OHS) clinic for post-isolation assessment during the study period. Both permanent and temporary staff were eligible for inclusion.

Inclusion criteria were: (i) laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 infection by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or antigen test, and (ii) presentation at the OHS clinic following isolation.

Exclusion criteria were: (i) HCWs who tested negative for COVID-19, (ii) those who did not present to the OHS clinic after infection, and (iii) those presenting for reasons other than COVID-19. If multiple infections were recorded for the same HCW, only the first episode during the study period was included.

2.3. Data Sources and Variables

Data were extracted from the OHS clinic register and corresponding patient files using a structured case report form (CRF) developed for the study. The CRF captured the following domains:

Sociodemographic characteristics: age (categorised as 17–34, 35–54, and ≥55 years), sex, and professional cadre (e.g., nurses, physicians, allied health, administrative staff).

Clinical variables: presence of comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, asthma, HIV, or other chronic conditions as documented in the file), reported COVID-19 symptoms, hospital admission, and number of days absent from work.

Vaccination status: receipt of at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, vaccine type (Ad26.COV2.S or others, where recorded), and number of doses received.

Epidemiological variables: wave period (third vs. fourth wave), classified according to the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) definition of epidemic waves.

All data were de-identified prior to analysis, and each record was assigned a unique study identifier. Records with missing data on key variables (e.g., vaccination status, age, or comorbidity status) were excluded from relevant analyses but retained for descriptive summaries where possible.

2.4. Data Management

Data were entered into Epi-Info and exported to Stata version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) for cleaning and analysis. Consistency and logic checks were performed to ensure data quality. Final datasets were stored on password-protected computers accessible only to the research team.

2.5. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise HCW characteristics. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations (SD) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), depending on distribution.

Associations between categorical variables (e.g., vaccination status, sex, wave period) were assessed using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Logistic regression was applied to estimate crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for factors associated with vaccination status among infected HCWs. Variables were included in the multivariable model if they were significant in bivariate analysis (p < 0.1) or identified as potential confounders in the literature. Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors, and model fit was evaluated using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test and pseudo R² statistics. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.6. Data Management

Data were entered into Epi-Info, cleaned, and exported into Stata version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) for analysis. Consistency checks and logic checks were performed. Missing values were assessed; records with critical missing data (e.g., unknown vaccination status) were excluded from specific analyses but retained for descriptive summaries.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Participant Characteristics

A total of 1,235 healthcare worker (HCW) records met the inclusion criteria. The mean age was 39.6 years (SD ± [insert if available]), with 35.7% aged 17–34 years, 52.5% aged 35–54 years, and 11.8% aged ≥55 years. The majority were female (82.7%). Comorbidities were documented in 10.5% of HCWs. Regarding infection timing, 44.6% of cases occurred during the third wave and 55.4% during the fourth wave. Most HCWs (94.3%) took ≤30 days of sick leave, and only 0.7% required hospital admission. No deaths were recorded.

A total of 1,235 healthcare worker (HCW) records met the inclusion criteria. The mean age was 39.6 years, with 35.7% aged 17–34 years, 52.5% aged 35–54 years, and 11.8% aged ≥55 years. The majority were female (82.7%). Comorbidities were documented in 10.5% of HCWs.

Regarding infection timing, 44.6% of cases occurred during the third wave and 55.4% during the fourth wave. Most HCWs (94.3%) took ≤30 days of sick leave, and only 0.7% required hospital admission. No deaths were recorded.

Table 1 summarises the demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants.

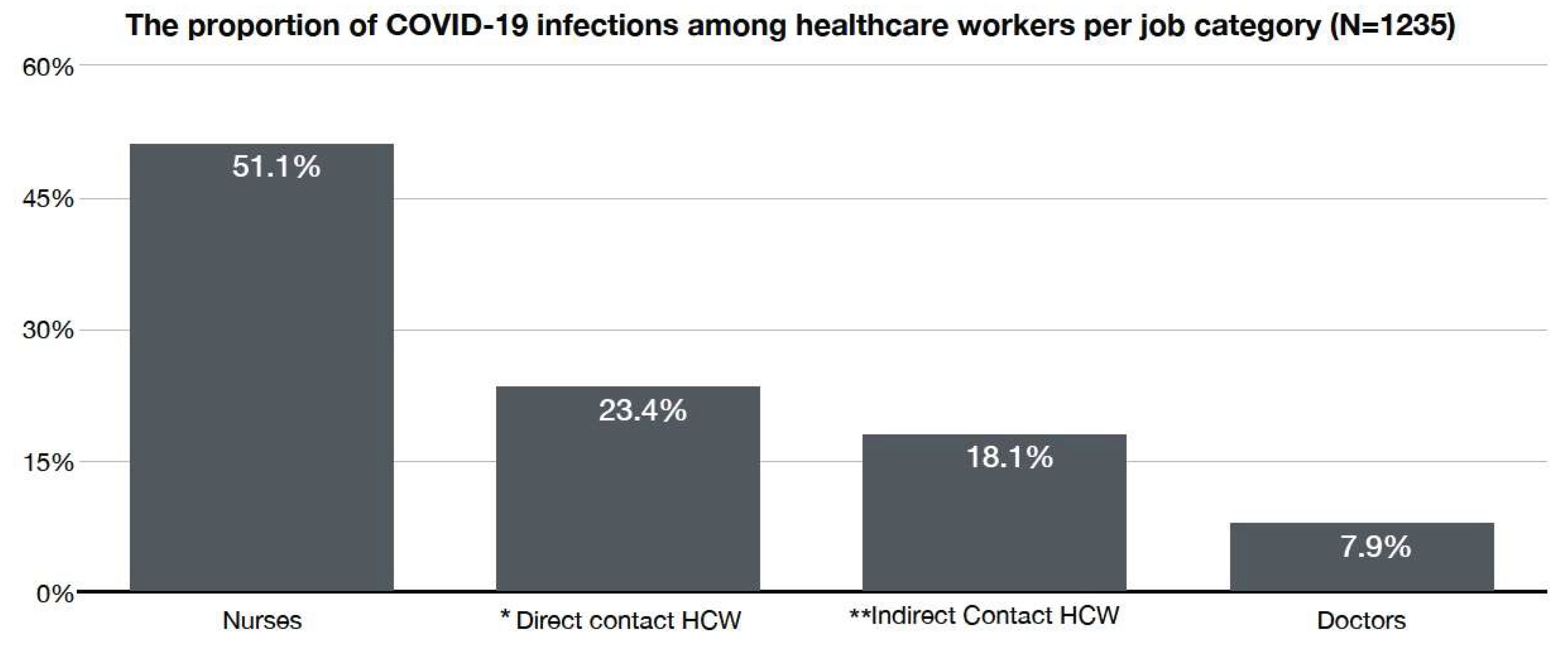

Nurses accounted for the largest proportion of infections, followed by healthcare assistants and medical doctors. Staff with direct patient contact (e.g., nurses, physicians, cleaners, pharmacy staff, and security personnel) represented the majority of infections compared to those with indirect contact (e.g., laboratory and administrative staff).

Figure 1 shows the proportion of infections by professional category.

About 55.4% of infected HCWs were vaccinated. Vaccination prevalence differed significantly by sex: 57.1% of females versus 47.2% of males were vaccinated (p = 0.008).

Table 2 presents vaccination status by sex.

A higher proportion of vaccinated HCWs were infected during the fourth wave compared to the third wave (65.1% vs. 43.4%, p < 0.001).

Table 3 shows vaccination status stratified by wave.

Univariate logistic regression showed that males had significantly lower odds of being vaccinated compared with females (Crude OR = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.49–0.90, p = 0.008). Older HCWs (≥55 years) had nearly three-fold higher odds of vaccination than those aged 17–34 years (Crude OR = 2.94, 95% CI: 1.97–4.39, p < 0.001). The presence of comorbidity was also positively associated with vaccination (Crude OR = 1.48, 95% CI: 1.02–2.16, p = 0.041).

After adjustment in the multivariable model, these associations remained significant. Males continued to show lower odds of vaccination (AOR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.47–0.89, p = 0.007). Compared with HCWs aged 17–34 years, those aged 35–54 years (AOR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.43–2.38, p < 0.001) and those aged ≥55 years (AOR = 3.28, 95% CI: 2.13–5.04, p < 0.001) were significantly more likely to be vaccinated. Comorbidity remained a predictor of vaccination (AOR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.01–1.98, p = 0.043). In addition, infection during the fourth wave was strongly associated with vaccination status (AOR = 2.54, 95% CI: 2.01–3.23, p < 0.001).

Table 4 summarises the univariate and multivariable regression results.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study show a high burden of COVID-19 among healthcare workers, particularly nurses. This finding is similar to previous studies that identified nurses as high-risk due to their prolonged, direct, and close contact with patients[

21]. Other risk factors affecting nurses include improper use of personal protective equipment (PPE) [

22], working in ICU[

21], and accidental exposure to colleagues or patients[23, 24]. These factors highlight the need for education on PPE use and implementing administrative controls to reduce exposure time.

Contributing factors to transmission included poor ventilation, close contact, and non-adherence to preventive measures[22, 25]. Healthcare workers should maintain infection control practices despite vaccination to prevent transmission [22, 25]. The studies emphasise the importance of vaccination in reducing the risk of COVID-19 infection and severe COVID-19 disease health outcomes among healthcare workers and maintaining stringent infection control measures to mitigate transmission risks.

Our findings show that during the 3rd wave, vaccinated healthcare workers had a significantly lower risk of infection than unvaccinated individuals. This finding is consistent with other studies[26, 27]. Most breakthrough infections were mild, with few requiring hospitalisation and no deaths reported, consistent with other studies [26, 27]. However, the 4th wave recorded more infections compared to the 3rd wave despite higher vaccination rates. This might be due to the immune escape of the Omicron variant and the fact that most unvaccinated healthcare workers had been infected in the 3rd wave and benefited from immunity conferred by natural infection, thus underscoring the dynamic nature of the COVID-19 pandemic waves and the evolving challenges in infection control among healthcare workers.

The study highlights several key factors influencing vaccination rates among healthcare workers, including gender, age, and comorbidity. For example, older healthcare workers and those with comorbidities were more likely to be vaccinated. These findings are consistent with other studies conducted elsewhere in Africa[

28]. Concerning gender disparity, these findings show that females were more likely to be vaccinated across the 3rd and 4th waves. These findings contrast the other studies, which show that males had higher vaccination uptake rates and intentions to vaccinate[

29]. Furthermore, poor vaccination uptake among younger healthcare workers might be due to complacency and hesitancy[

30]. Conversely, higher vaccination rates among older workers could be explained by their perceived risk of severe disease and poor health outcomes compounded by comorbidities.

4.1. Implications

Based on the results of this study, several recommendations can be made to protect healthcare workers (HCWs) from COVID-19 infections and ensure the continuity of essential healthcare services. First, there is a need to improve infection prevention and control measures in healthcare settings. This includes strict adherence to protocols such as using PPE and regular hand hygiene practices. Healthcare organisations should provide comprehensive training and resources to implement these measures properly.

Secondly, it is crucial to prioritise the vaccination of health workers, especially those in high-risk categories, such as nurses. Access to COVID-19 vaccines should be ensured, and efforts should be made to promote vaccine uptake among healthcare workers. Vaccination is crucial in reducing the risk of infection and severe health outcomes among healthcare workers.

Thirdly, targeted strategies must be developed to protect older age groups and healthcare workers with comorbidity-secured. These groups are more vulnerable to COVID-19 infection and its complications. Tailored infection prevention measures, closer monitoring, and additional support and resources should be provided to mitigate their increased vulnerability.

Fourthly, fostering collaboration and knowledge sharing among healthcare organisations and researchers is vital. This will facilitate the exchange of best practices, research findings, and lessons learnt in managing COVID-19 infections among healthcare workers. Collaborative efforts can drive continuous improvement and enhance the overall response to the pandemic.

4.2. Key messages

Nurses are the most susceptible to infection by the SARS-COV-2 virus; frequent surveillance is recommended.

Elderly healthcare workers with comorbidities are at high risk of contracting COVID-19 infections.

Vaccination for COVID-19 protects against severe disease.

Booster doses of COVID-19 are recommended to combat the spread of the virus.

5. Limitations.

The following limitations are acknowledged. First, only COVID-19-positive employees who presented at the occupational health clinic were included in the study. Including negative employees, vaccinated and unvaccinated, would have provided an analysis of the vaccine effectiveness. Second, poorly recorded data and missing data elements, hence missing vaccination dates, may have skewed the results. Third, estimating acquired occupational infections versus acquired versus community was difficult, as not all employee infection exposure assessments were performed. The reported cases are expected to underestimate the burden of the disease because not all the employees came to the occupational clinic after isolation. Finally, the results of this study may not be generalisable to the South African healthcare workers' population, as the analysis included only positive HCWs diagnosed with COVID-19 infection who presented at the occupational health clinic. Other factors not measured, such as PPE use or its availability.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study reveals a high burden of COVID-19 among healthcare workers, particularly nurses, highlighting their significant risk due to prolonged patient contact and other workplace exposures such as exposure to patients or infected colleagues. Despite vaccination efforts, maintaining stringent infection control practices remains crucial to mitigate transmission risks. The findings also highlight the dynamic nature of COVID-19 pandemic waves, with vaccinated healthcare workers experiencing fewer severe infections during the 3rd wave. In contrast, the Omicron variant in the 4th wave posed new challenges, such as high transmission, albeit with less severe disease. Additionally, the study identifies key demographic factors influencing vaccination rates, such as gender, age, and comorbidity, providing valuable insights for public health strategies to enhance vaccine uptake and effectively protect frontline workers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.N. and T.D.L.; methodology, X.N., T.D.L. and V.N.; validation, X.N., V.N. and T.D.L.; formal analysis, V.N.; investigation, X.N.; resources, X.N.; data curation, X.N.; writing—original draft preparation, X.N.; writing—review and editing, X.N., V.N. and T.D.L.; supervision, T.D.L.; project administration, X.N. and T.D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding,.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University Research Ethics Committee (SMUREC/M/249/2021). The date of approval on 7 October 2021. Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the National Health Research Database (NDOH_202201_005).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because secondary, anonymized data were used. Consent was not required from participants because it is secondary data encoded with no identifiers. Furthermore, sensitive information obtained during the study was treated as confidential. As outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, the principles of protecting the dignity and safety of all research participants were observed by ensuring the confidentiality of records and assigning unique identifiers to participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality of hospital staff records but may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| HCW |

Healthcare Worker |

| HIV |

Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| IPC |

Infection Prevention and Control |

| NICD |

National Institute for Communicable Diseases |

| OHS |

Occupational Health Service |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PPE |

Personal Protective Equipment |

References

- Piapan L, De Michieli P, Ronchese F, Rui F, Peresson M, Segat L, D’Agaro P, Negro C, Bovenzi M, Larese Filon F (2022) COVID-19 outbreaks in hospital workers during the first COVID-19 wave. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 72:110–117.

- Zheng C, Hafezi-Bakhtiari N, Cooper V, Davidson H, Habibi M, Riley P, Breathnach A (2020) Characteristics and transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in healthcare workers at a London teaching hospital. Journal of Hospital Infection. [CrossRef]

- Stead D, Adeniyi OV, Singata-Madliki M, Abrahams S, Batting J, Jelliman E, Parrish A (2022) Cumulative incidence of SARS-CoV-2 and associated risk factors among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. BMJ Open 12:58761.

- Muller SA, Wood RR, Hanefeld J, El-Bcheraoui C (2022) Seroprevalence and risk factors of COVID-19 in healthcare workers from 11 African countries: a scoping review and appraisal of existing evidence. Health Policy Plan. [CrossRef]

- Lai X, Wang M, Qin C, et al (2020) Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-2019) Infection Among Health Care Workers and Implications for Prevention Measures in a Tertiary Hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Netw Open 3:209666.

- Zhang J-J, Dong · Xiang, Liu G-H, Gao Y-D (2023) Risk and Protective Factors for COVID-19 Morbidity, Severity, and Mortality. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 64:90–107.

- Tlotleng N, Cohen C, Made F, Kootbodien T, Masha M, Naicker N, Blumberg L, Jassat W (2022) COVID-19 hospital admissions and mortality among healthcare workers in South Africa, 2020-2021. IJID Regions 5:2020–2021.

- Péterfi A, Mészáros Á, Szarvas Z, Pénzes M, Fekete M, Fehér Á, Lehoczki A, Csíp T, Fazekas-Pongor V (2022) Comorbidities and increased mortality of COVID-19 among the elderly: A systematic review. Physiol Int 109:163–176.

- Bubar KM, Reinholt K, Kissler SM, Lipsitch M, Cobey S, Grad YH, Larremore DB (2021) Model-informed COVID-19 vaccine prioritization strategies by age and serostatus.

- Symons X, Matthews S, Tobin B (2021) Why should HCWs receive priority access to vaccines in a pandemic? BMC Med Ethics. [CrossRef]

- Bekker LG, Garrett N, Goga A, et al (2022) Effectiveness of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine in health-care workers in South Africa (the Sisonke study): results from a single-arm, open-label, phase 3B, implementation study. The Lancet. [CrossRef]

- Sadoff J, Le Gars M, Shukarev G, et al (2021) Interim Results of a Phase 1–2a Trial of Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 384:1824–1835.

- Mohammed I, Nauman A, Paul P, et al (2022) The efficacy and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines in reducing infection, severity, hospitalization, and mortality: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. [CrossRef]

- Fiolet T, Kherabi Y, MacDonald C-J, Ghosn J, Peiffer-Smadja N (2022) Comparing COVID-19 vaccines for their characteristics, efficacy and effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern: a narrative review. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 28:202–221.

- Zheng C, Shao W, Chen X, Zhang B, Wang G, Zhang W (2022) Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: a literature review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 114:252–260.

- Rahmani K, Shavaleh R, Forouhi M, et al (2022) The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in reducing the incidence, hospitalization, and mortality from COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Casillas A, Redwan EM, Uversky VN (2022) SARS-CoV-2: A Master of Immune Evasion. Biomedicines 10:1339.

- Andrews N, Stowe F, Kirsebom S, et al (2022) Covid-19 Vaccine Effectiveness against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) Varian. New England Journal of Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Bálint G, Vörös-Horváth B, Széchenyi A (2022) Omicron: increased transmissibility and decreased pathogenicity. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7:151.

- Danza P, Tae ;, Koo H, Haddix M, Fisher R, Traub E, Oyong ; Kelsey, Balter S (2022) MMWR, SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Hospitalization Among Adults Aged ≥18 Years, by Vaccination Status, Before and During SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) Variant Predominance — Los Angeles County, California, November 7, 2021–January 8, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dzinamarira T, Nkambule SJ, Hlongwa M, et al (2022) Risk Factors for COVID-19 Infection Among Healthcare Workers. A First Report From a Living Systematic Review and meta-Analysis. Saf Health Work 13:263–268.

- Mhango M, Dzobo M, Chitungo I, Dzinamarira T (2020) COVID-19 Risk Factors Among Health Workers: A Rapid Review. Saf Health Work 11:262–265.

- Alajmi J, Jeremijenko AM, Abraham JC, Alishaq M, Concepcion EG, Butt AA, Abou-Samra A-B (2020) COVID-19 infection among healthcare workers in a national healthcare system: The Qatar experience. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 100:386–389.

- Ali S, Noreen S, Farooq I, Bugshan A, Vohra F (2020) Risk Assessment of Healthcare Workers at the Frontline against COVID-19. Pak J Med Sci. [CrossRef]

- Ehelepola NDB, Wijewardana BAS (2022) An episode of transmission of COVID-19 from a vaccinated healthcare worker to co-workers. Infect Dis 54:297–302.

- Alshamrani MM, El-Saed A, Al Zunitan M, Almulhem R, Almohrij S (2021) Risk of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality among healthcare workers working in a Large Tertiary Care Hospital. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 109:238–243.

- Vaishya R, Sibal A, Malani A, Prasad Kh (2021) SARS-CoV-2 infection after COVID-19 immunization in healthcare workers: A retrospective, pilot study. Indian Journal of Medical Research 153:550.

- Nzaji MK, Kamenga J de D, Lungayo CL, et al (2024) Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake and hesitancy among healthcare workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. PLOS Global Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Hall VJ, Foulkes S, Saei A, et al (2021) COVID-19 vaccine coverage in health-care workers in England and effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against infection (SIREN): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. The Lancet 397:1725–1735.

- Adams SH, Schaub JP, Nagata JM, Park MJ, Brindis CD, Irwin CE (2021) Adolescent health brief Young Adult Perspectives on COVID-19 Vaccinations. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).