1. Introduction

Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) microplasma gained attention in the last decade due to its actual and potential applications combined with economic and ecologic advantages over other plasma technologies, or more conventional approaches in various application fields such as air treatment [

1], induced flow [

2], surface treatment of polymers [

3], sterilization of bacteria or transdermal drug delivery [

4,

5]. Discharges that have dimensions within micrometer range or even up to few milimeters are known as microplasmas. This type of microplasma, being generated at atmospheric pressure has the advantage of not requiring costly vacuum enclosures. Moreover, microplasma has the advantage of low temperature with highly energetic electrons, cold positive ions and neutrals within a small volume. This promotes the formation of a reactive environment with excited species, radicals, charged particles and photons that requires low energy consumption. The reduced electrode and reactor size of microplasma allows the device to be portable or easily integrated with other systems. Microplasmas exhibit power densities several orders of magnitude higher than those of conventional atmospheric-pressure nonthermal plasmas. The microplasma’s small dimensions, steep spatial gradients, and high surface-to-volume ratio contribute to its non-equilibrium nature, even at high power densities [

6].

DBD microplasma developed for specific applications requires relatively low discharge voltages below 5 kV to be generated [

6,

7]. Discharge voltage could be reduced in the case of using discharge gases such as argon. This is another advantage over other types of plasma which are generated at tens of kilovolts. In this study a surface DBD microplasma electrodes system was used. The microplasma electrode consists of a high voltage electrode covered with a dielectric layer on the back side, and a dielectric layer in between the high voltage electrode and grounded electrode. Microplasma is generated at the surface of the grounded electrode. This type of electrode can be scaled to various surfaces larger or smaller and can be bent to various shapes since its flexible. Although the electrode can have various sizes the discharge voltage remains the same thus there is no need for additional insulation on larger surfaces.

One possible application of DBD microplasma could be enhancement of blood coagulation processes thus alleviation of hemorrhages. Hemorrhage is a major cause of death in the case of potentially survivable accident injuries. Thus, development of a tool to mitigate bleeding, particularly in the prehospital environment, would be most welcomed.

An important step of hemostasis is coagulation and this occurs immediately after a damage affects the vascular endothelium to prevent blood loss [

8]. Blood has a natural tendency to coagulate thus this is the main mechanism to counteracts injuries. In the case of modern surgical procedures where bleeding occurs there are attempts to control blood coagulation rates by e.g.: decreasing the duration of surgeries or increasing the blood coagulation rates after surgery for wound healing. In the case of accident injuries, the measures to stop bleeding have to be taken immediately. The tools available for bleeding suppression are electric cauterization, various medications, thermal coagulation acceleration, and others. As most of these methods have unwanted and deleterious side effects such as the cauterization of healthy tissue, a method for bleeding suppression that is safe and has quick response is needed. As studies showed [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], one of such methods could be treatment with nonthermal plasma. As a potential tool for controlling blood coagulation and promoting wound healing, nonthermal plasma offers the advantage of precisely regulating coagulation rates at targeted sites while minimizing side effects. Nonthermal plasma acts on blood proteins thus the coagulation process is a selective one as compared with thermal coagulation process which act on the whole blood composition and surrounding tissues. [

9]. As shown by Yan

et. al. [

8] plasma can lead to rapid blood coagulation which is necessary in e.g. traffic accident injuries scenarios. Moreover, after the blood coagulation process induced by plasma the blood coagulation layer is thicker and denser [

8].

Plasma can rapidly and effectively promote blood coagulation by forming a transparent white membrane, primarily composed of aggregated platelets, on the surface of whole blood. Research has been carried out with studies

in vitro and

in vivo for blood coagulation. Yan

et. al. [

8], showed that nonthermal plasma is a promising tool in stanching bleeding during surgical operation on rats. There are no thermal effects involved and hemorrhages can be controlled quickly.

Nonthermal plasma as a new tool for the control of blood coagulation has also the capability to promote wound healing [

10]. The treatment of wounds using nonthermal plasma provides besides a faster healing also the sterilization of the wound.

After accidents a response to address an injury with a tool that provides a short coagulation time could be the difference between life and death. In this regard a nonthermal plasma device would be the perfect tool for treating injuries by first responders since it provides a faster coagulation time. Although there is already research carried out in this field, the majority of nonthermal plasma devices used for plasma medicine application, are based on high-voltage devices that are expensive and difficult to operate. Thus, Cheng

et. al. [

10] and Nomura

et. al. [

11] showed results of blood coagulation and wound healing using nonthermal plasma jet type devices. However, such plasma devices have relatively high discharge voltages of about 9 kV and are using discharge gases from gas cylinders which makes them unfeasible as portable devices. Plasma jet devices were used for blood coagulation also by other researchers [

12,

13,

14,

15]. A floating electrode DBD system proposed by Friedman

et. al. [

16] is also energized at about 15 kV. Furthermore, our previous work [

5] demonstrated that plasma jet irradiation can cause damage to target samples, including etching effects and the formation of small pores. Therefore, to make the nonthermal plasma tool suitable for first responders, the device must also be portable and capable of being powered by batteries.

As explained above, such advantages could be provided by using microplasma for blood coagulation and wound healing. In this study, as first step towards the development of nonthermal plasma tools for such applications, we have investigated the coagulation effect of microplasma treatment on blood samples collected from a dog and a cat.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

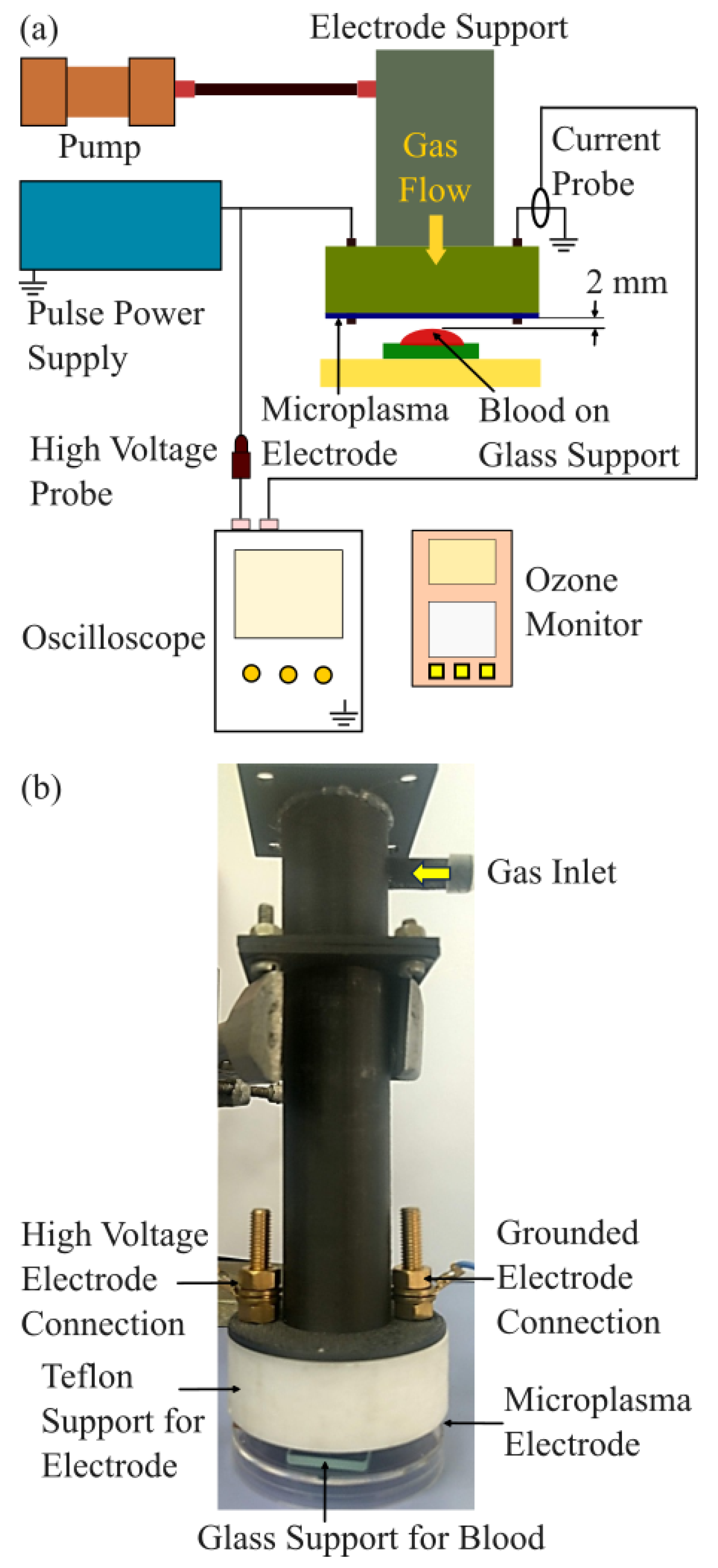

Figure 1(a) presents a schematic image of the experimental setup designed for blood coagulation experiments using microplasma treatment. As shown in

Figure 1(b), the microplasma electrode is mounted on a support structure that includes electrical connections and a gas inlet to supply gas flow to the electrode. During the experiments, the electrode was positioned 1.5 to 2 mm above the surface of blood droplets.

Air was supplied using a miniature pump (Mitsumi, Tokyo, Japan, R14-1604), which operates within a voltage range of 4.5–12 V, making it suitable for battery-powered and portable systems. Ambient air with a relative humidity (RH) of 35–55% was used, and the flow rate was maintained at 0.6 L/min. An ozone monitor (NORM, Changzhou, China, ADKS-1 O3 Ozon) was positioned 2 mm below the microplasma electrode to measure ozone concentration. The discharge voltage was gradually increased from -3.0 kV to -3.4 kV in 0.2 kV increments for blood coagulation experiments. Ozone concentration measurements were performed for discharge voltages ranging from -1.4 kV to -3.4 kV, also in 0.2 kV increments, at the same air flow rate of 0.6 L/min.

A custom-built, two-stage Marx Generator equipped with MOSFET switches was developed in the laboratory to serve as the pulsed power supply for the microplasma electrodes. The generator produces negative voltage pulses with peak amplitudes of up to -4 kV. In the blood coagulation experiments, discharge voltages were set at -3.0 kV, -3.2 kV, and -3.4 kV, with pulse frequencies of 700 Hz and 825 Hz. A pulse waveform with a pulse width of 800 ns which is shorter than previously reported in [

4] was employed to improve energy efficiency.

The discharge voltage and current were measured using a high-voltage probe (Tektronix, Beaverton, OR, USA, Tek P5100) and a current probe (Tektronix A622), respectively. Both probes were connected to a digital oscilloscope (Tektronix MSO 4104).

A light microscope (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany, Olympus BX51) coupled with a CCD camera was used to analyze the blood samples.

2.2. Microplasma Electrode

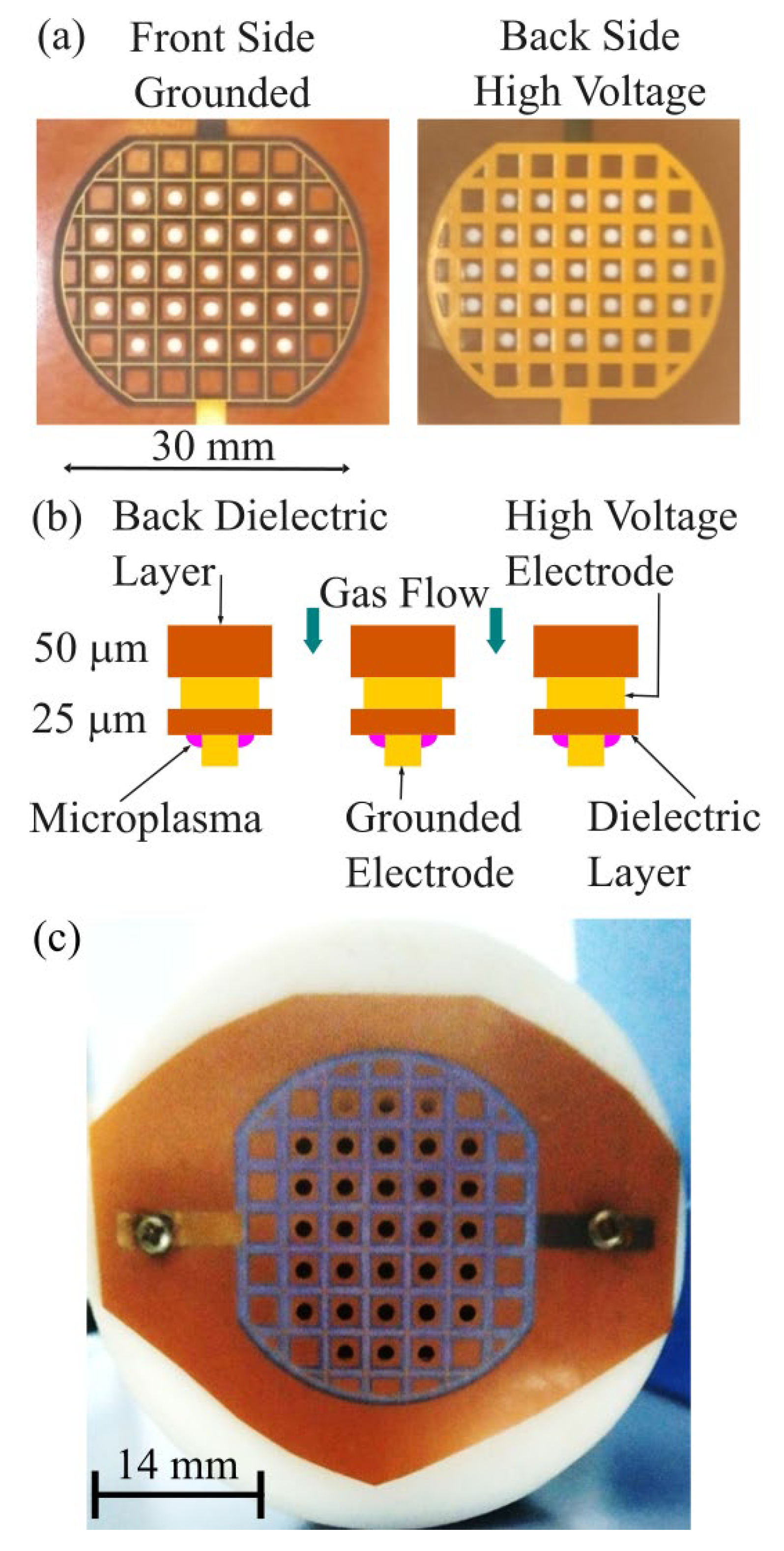

The microplasma electrode was facing the blood droplet which was placed on a glass lamella support. Microplasma was generated at atmospheric pressure using a surface DBD electrode. The setup included a 25 µm thick dielectric layer placed between two grid-shaped wires: the high-voltage electrode (1.2 mm width) and the grounded electrode (0.2 mm width), as illustrated in

Figure 2(a) and (b). A 50 µm thick dielectric backing layer covered the high-voltage side.

The electrode, 30 mm in diameter, featured a grid pattern with 3.5 mm spacing. It also contained 31 perforated holes, each 2 mm in diameter (Ø), allowing gas flow and facilitating the delivery of reactive species produced by the microplasma to a specific target. As shown in

Figure 2(b) and (c), the microplasma discharge was observed near the grounded electrode grid.

There is symmetry across the surface of the microplasma electrode pattern that translates in-to the possibility of designing the electrodes to meet the demand for various values of surface areas to be treated by microplasma. Although the electrode surface area is modified the discharge voltage remains the same, only the discharge power will modify, thus allowing to keep the same electrical insulation level.

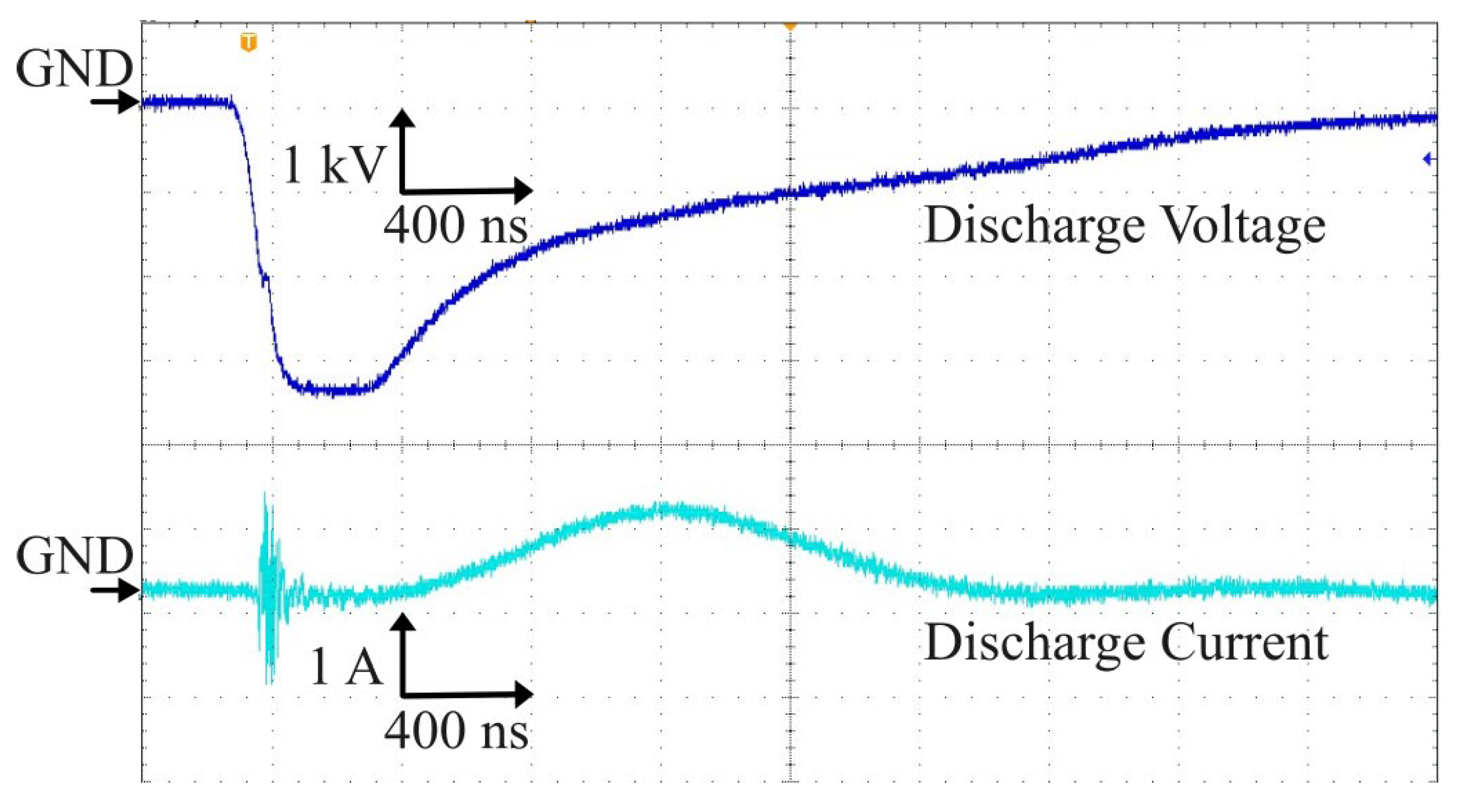

The output of the Marx generator energized the electrodes at a negative pulse voltage with pulse width of 800 ns and a pulse rising time of 160 ns as shown in

Figure 3. The spikes convoluted in the current waveform at the rising time of discharge voltage, appeared due to microplasma generation. The microplasma power is obtained by multiplying the voltage

V and current

I waveforms. The power was calculated by integrating the power waveform in time and divided with the period corresponding to the frequency of 700 Hz and 825 Hz. The calculated discharge power is shown in

Table 1.

2.3. Ozone Generation

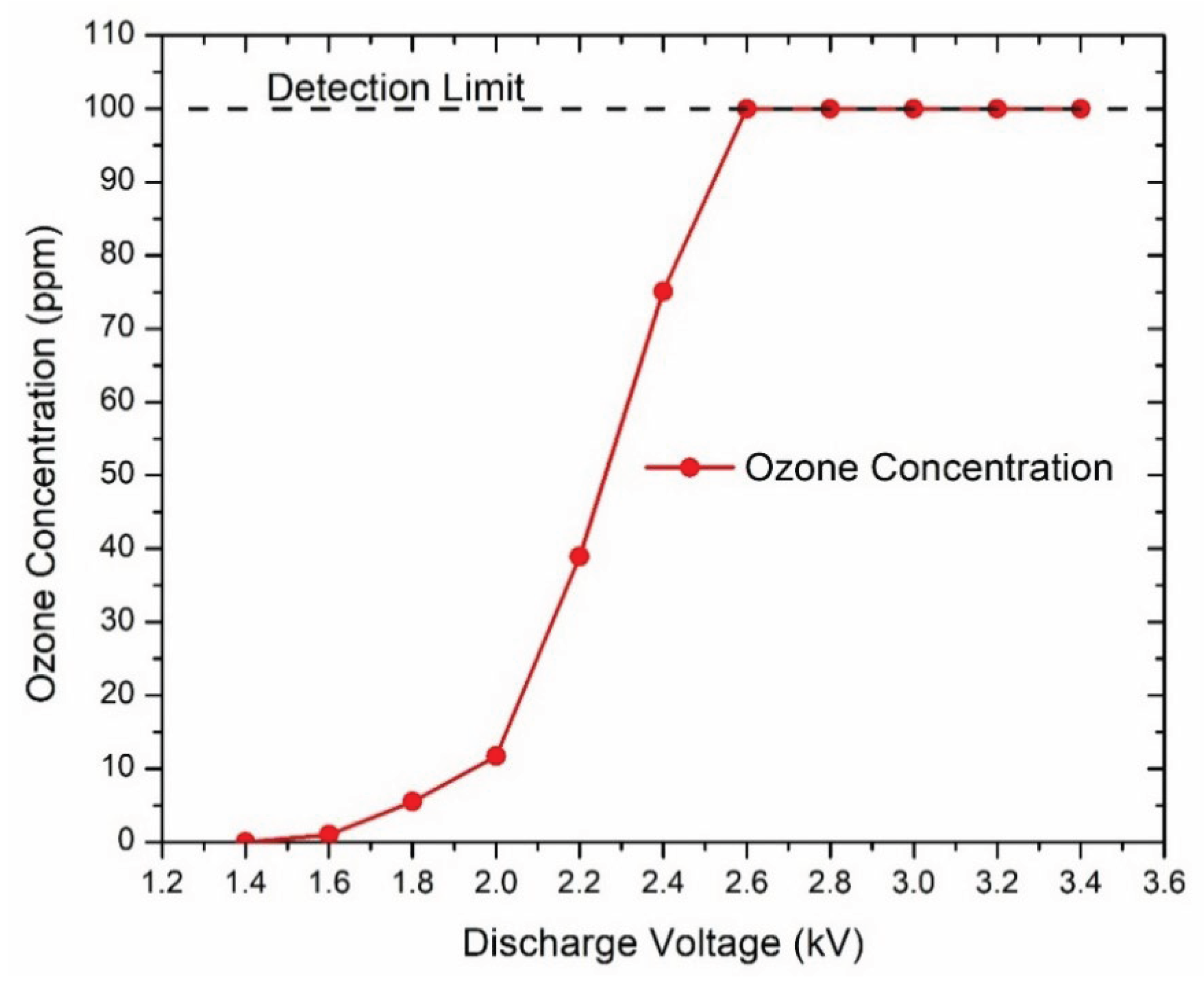

The concentrations of ozone generated by the microplasma increased with discharge voltage at a gas flow rate of 0.6 L/min, as shown in

Figure 4. At the discharge voltage of -1.4 kV no ozone was measured. At -2.6 kV and above, the measured ozone concentration was 100 ppm which was the maximum detection limit of the ozone monitor. Thus, we can assume that the values of ozone concentration at -3 kV, -3.2 kV and -3.4 kV were more than 100 ppm. Pulse frequency was 825 Hz.

2.4. Blood Sample Preparation

Blood samples from a dog and a cat were obtained from the Hematology Laboratory of the University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine, Cluj-Napoca, Romania. The blood was stored in a refrigerator until the experiments have been carried out. The blood samples were collected in EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) tubes for preventing blood clotting. A volume of 20 µL blood was dispersed with a pipette on a glass lamella support placed at the distance of 1.5÷2 mm below the microplasma electrode and the microplasma was applied. Based on the observed blood coagulation effect, the microplasma treatment parameters consisting of treatment time, discharge voltage and pulse frequency were modified. The blood sample was photographed before and after each experimental point. After the treatment, using the pipette tip, the surface of the blood was scratched in order to observe if a coagulated layer was formed. A rough estimation of the coagulation layer thickness was carried out using the obtained images.

3. Results

Previously we have reported using the same type of electrode, the sterilization of

Escherichia coli,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and

Staphylococcus aureus at a gas flow rate of 0.6 L/min. [

4]. Based on those previous bacteria sterilization results [

4], that were obtained using discharge voltages below -2 kV, we here carried out the blood treatment by microplasma starting with the same discharge voltages. As at those voltages it was not observed any effect, we increased the discharge voltage above -2 kV and the first visible coagulation effect was at -3.2 kV, 700 Hz, 0.6 L/min air flow after 5 minutes of treatment (

Figure 5). For comparison reason, samples of blood were also subjected to plasma treatment using only air flow at 0.6 L/min. for 5 minutes. After 5 minutes of microplasma treatment, a coagulated layer with a thickness estimated at around 150-200 µm was formed. As illustrated in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, no coagulated layer was formed on the blood droplet during the treatment with air flow only.

In order to increase the microplasma on-time and thus the coagulation effect, we increased the frequency to 825 Hz. Using that frequency, we started at -3 kV and carried out experiments for one minute to 6 minutes with one minute incremental steps. As shown in

Figure 6, a weak coagulation effect could be observed after 5 minutes of treatment. The coagulated layer thickness was estimated at around 150-200 µm after 5 minutes and 6 minutes of microplasma treatment. In contrast, no effect was observed even after 6 minutes of treatment with air flow only (Fig. 6).

After that first set of experiments, the discharge voltage was increased at -3.2 kV at 825 Hz frequency and a visible coagulation effect could be observed after 3 minutes of treatment as shown in

Figure 7. After 6 minutes of microplasma treatment the layer on the surface of blood droplet is completely coagulated and could be peeled off with the tip of the pipette. The coagulated layer thickness after 3 minutes of microplasma treatment could be estimated at around 150-200 µm and increased to about 500 µm after 6 minutes of treatment. There were also visible two different color intensities, i.e. one of the peeled-off coagulated layer (dark red), and one of the non-coagulated blood (light red).

In the next experimental step, the discharge voltage was further increased to -3.4 kV, frequency 825 Hz, in order to investigate if the blood coagulation effect is also stronger at this voltage. As shown in

Figure 8, a coagulation layer was visible at the surface of blood droplet after 2 minutes of treatment at this voltage. The coagulated layer thickness after 2 minutes of microplasma treatment could be estimated at <200 µm and increased to about 800 µm after 6 minutes of treatment. As a discharge voltage of -3.4 kV is close to the microplasma electrode breakdown voltage, no further increase was carried out above this voltage.

In order to investigate in more depth the coagulation effects induced using -3.4 kV, 825 Hz and for 6 minutes of treatment, cat blood samples subjected to that treatment were analyzed through microscopy. Samples of non-treated blood, blood treated for 6 minutes with air flow rate at 0.6 L/min., and blood treated by microplasma at -3.4 kV, 825 Hz and at an air flow rate of 0.6 L/min for 6 minutes, were prepared by spreading the blood with the glass lamellas. During the spreading process only a thin layer of blood remained on the glass lamella and was analyzed by microscopy (sample are shown in

Figure 9). The non-treated blood sample and the blood samples treated with air flow showed almost the same color at 1x magnification and at 10x and 40x magnification similar patterns of light color spots. The blood sample treated by microplasma showed a darker color compared with the other two samples at 1x magnification and also different patterns at 10x and 40x where it can be observed larger light color spots. Most probably, those larger spots appeared due to the fact that the treated blood became more solid and sticks to the glass and it therefore less susceptible to be uniformly spread over the glass lamella.

4. Discussions

4.1. Discussions

The microplasma discharge in air generates Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species (RONS). Excited states N

2(C

3Π

u), N

2+(B

2Σ

u+), N

2(A

3Σ

u), O(3p

5P), O(3p

3P), OH(A

2Σ) were produced in microplasma through the reactions which are initiated by the electron impact dissociation of N

2, O

2, and H

2O (water vapors in room air) as shown in reactions (1) to (12). Also, the reactive products are forming furthermore other RONS [

15,

17]:

Ozone (O

3) is produced by the three-body reaction of O

2 and O [

18]:

where M is a third collision partner: O

2, O

3 or O.

The use of environmental air as discharge gas for microplasma treatment of blood over the use of argon and other discharge gases is a more practical solution since air is available freely, thus there is no need for gas cylinders and also is more economical. The air flow rate value of 0.6 L/min. was chosen considering our previously reported research [

4]. We also reported in [

2] that the air containing active species is flown to the treatment target by the electrohydrodynamic (EHD) induced flow. In order to determine the influence of active species on the blood we considered the research reported in [

19]. According to Sakiyama et al. [

19], the lifetimes of reactive neutral species such as O and OH are approximately 0.1 ms, while that of N is around 1 ms. Given a 2 mm distance between the electrode and the blood sample, the presence of electrode holes, and an air flow rate of 0.6 L/min, the air carrying these active species is estimated to reach the blood after a minimum of 5 ms. Therefore, it can be concluded that the coagulation process is primarily driven by the presence of long-lived active species. However, as indicated in [

19], the density of reactive species may influence the interpretation of the results. Reactive oxygen species (e.g. superoxide and hydrogen peroxide) and reactive nitrogen species (e.g. nitric oxide) are known for influencing blood coagulation by several mechanisms that can accelerate clot formation. These mechanisms include platelet activation, endothelial dysfunction, tissue faction expression and fibrin formation [

20,

21,

22]. Ozone could also play a role in the coagulation process.

The coagulation effect induced by microplasma treatment may result from multiple mechanisms, including accelerated vasoconstriction of blood vessels in case of plasma application on wound directly, activation of coagulation factors, stimulation of platelet aggregation, and enhancement of fibrin polymerization [

15].

The energy consumption for the experimental point -3.4 kV, 825 Hz and 6 minutes of treatment time was 466 J. Although only 20 µL of blood was treated by microplasma, the blood droplet diameter was about 8 mm thus the energy consumption will be the same in the case of treating an area with blood equal to the microplasma discharge area.

There is no thermal effect of microplasma on the blood since our microplasma is a type of nonthermal plasma. The temperature of the rat skin placed at 3 mm distance from microplasma electrode surface and treated by microplasma for 3 minutes was reported previously [

5] to be below 40 °C.

The blood coagulation was carried out using microplasma discharge in air. The coagulation effect could be clearly observed starting at the discharge voltage of -3.2 kV and at least 3 minutes of treatment time with the blood sample placed at 2 mm from microplasma electrode. The strongest coagulation effect was observed at -3.4 kV, 825 Hz and 6 minutes of treatment time. By comparison it was not observed any effect after 6 minutes of treatment time using only air flow. The process of blood coagulation is due to the action of RONS. The effect of microplasma on blood increases with the increase of discharge voltage, frequency and treatment time. The results suggest the potential of microplasma as a technology for a faster, more economical because of low discharge voltage and power, and safer coagulation process because of the room temperature of microplasma. Owing to its relatively low discharge voltage and power consumption, microplasma presents a promising option as a portable coagulation tool for use by first responders

4.2. Limitations/Future Work

This work had some limitations since there is a lack of platelet/fibrin assays. Another limitation was the reduced number of blood samples available. We propose these as future research directions. Since the blood coagulation mechanism is likely related to RONS-mediated platelet activation and fibrin formation, experimental validation of D-dimer, fibrinogen changes, platelet markers, will be carried out in future studies.

In such future studies, we suggest the use of emission spectroscopy method to experimentally determine the presence of active species generated by microplasma at various distances from the electrode. In addition, experiments carried out with blood samples located at a distance of more than 2 mm from the plasma electrode should be performed in order to determine the efficacy of microplasma for blood coagulation at various distances from the blood samples or wounds.

Furthermore, as the final goal of such studies is to use microplasma for blood coagulation in a prehospital environment in case of hemorrhage, future work must be carried out with experiments in vivo.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that microplasma treatment generated at -3.4 kV, 825 Hz for 6 minutes has a strong blood coagulation effect. However, more work is necessary in vitro to evaluate the mechanistic bases of the observed coagulation effects and in vivo to investigate if similar effects could occur in case of hemorrhages.

Author Contributions

Marius Gabriel Blajan: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, review and editing. Anca Daniela Stoica: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, review and editing. Cristian Sevcencu: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, review and editing. Septimiu Cassian Tripon: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation. Vasile Surducan: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation. Kazuo Shimizu: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation.

Funding

This research was funded by the “Nucleu” Program within the National Plan for Research, Development and Innovation 2022–2027, project PN 23 24 02 01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Hematology Laboratory, coordinated by Professor Bogdan Sevastre at the University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, for kindly providing the biological samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shimizu, K., Blajan, M., & Kuwabara, T. (2011). Removal of indoor air contaminant by atmospheric microplasma. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, 47(6), 2351–2358. [CrossRef]

- Blajan, M., Nonaka, D., Kristof, J., & Shimizu, K. (2019). Study of Induced EHD flow by microplasma vortex Generator. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science, 47(12), 5345–5354. [CrossRef]

- Blajan, M., Umeda, A., Muramatsu, S., & Shimizu, K. (2011). Emission spectroscopy of pulsed powered microplasma for surface treatment of PEN film. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, 47(3), 1100–1108. [CrossRef]

- Blajan, M. G., Ciorita, A., Surducan, E., Surducan, V., & Shimizu, K. (2025). Biological decontamination by microplasma. Applied Sciences, 15(5), 2527. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K., Hayashida, K., & Blajan, M. (2015). Novel method to improve transdermal drug delivery by atmospheric microplasma irradiation. Biointerphases, 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Iza, F., Kim, G. J., Lee, S. M., Lee, J. K., Walsh, J. L., Zhang, Y. T., & Kong, M. G. (2008). Microplasmas: sources, particle kinetics, and biomedical applications. Plasma Processes and Polymers, 5(4), 322–344. [CrossRef]

- Gershman, S., Harreguy, M. B., Yatom, S., Raitses, Y., Efthimion, P., & Haspel, G. (2021). A low power flexible dielectric barrier discharge disinfects surfaces and improves the action of hydrogen peroxide. Scientific Reports, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Yan, K., Jin, Q., Zheng, C., Deng, G., Yin, S., & Liu, Z. (2018). Pulsed cold plasma-induced blood coagulation and its pilot application in stanching bleeding during rat hepatectomy. Plasma Science and Technology, 20(4), 044005. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Chen, G., Obenchain, R., Zhang, R., Bai, F., Fang, T., Wang, H., Lu, Y., Wirz, R. E., & Gu, Z. (2022). Cold atmospheric plasma delivery for biomedical applications. Materials Today, 54, 153–188. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K., Lin, Z., Cheng, Y., Chiu, H., Yeh, N., Wu, T., & Wu, J. (2018). Wound healing in Streptozotocin-Induced diabetic rats using Atmospheric-Pressure argon plasma jet. Scientific Reports, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y., Takamatsu, T., Kawano, H., Miyahara, H., Okino, A., Yoshida, M., & Azuma, T. (2017). Investigation of blood coagulation effect of nonthermal multigas plasma jet in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Surgical Research, 219, 302–309. [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, K., Ikehara, S., Takei, H., Akimoto, Y., Sakakita, H., Ishikawa, K., Ueda, M., Ikeda, J., Yamagishi, M., Kim, J., Yamaguchi, T., Nakanishi, H., Shimizu, T., Shimizu, N., Hori, M., & Ikehara, Y. (2016). Red blood cell coagulation induced by low-temperature plasma treatment. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 605, 95–101. [CrossRef]

- Bekeschus, S., Brüggemeier, J., Hackbarth, C., Von Woedtke, T., Partecke, L., & Van Der Linde, J. (2017). Platelets are key in cold physical plasma-facilitated blood coagulation in mice. Clinical Plasma Medicine, 7–8, 58–65. [CrossRef]

- Rad, Z. S., Davani, F. A., & Etaati, G. (2018). Determination of proper treatment time for in vivo blood coagulation and wound healing application by non-thermal helium plasma jet. Australasian Physical & Engineering Sciences in Medicine, 41(4), 905–917. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y., Li, Y., Zheng, H., Zhang, B., Li, Y., Zhang, Y., Xu, Z., Xu, A., Jin, S., Fang, Z., Zhang, L., Zhao, Y., Zhu, L., & Li, X. (2025). Low-temperature plasma efficiently promotes blood coagulation with less thermal injury in porcine models. Scientific Reports, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Fridman, G., Peddinghaus, M., Balasubramanian, M., Ayan, H., Fridman, A., Gutsol, A., & Brooks, A. (2006). Blood coagulation and living tissue sterilization by Floating-Electrode dielectric barrier discharge in air. Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing, 26(4), 425–442. [CrossRef]

- Polito, J., Quesada, M. J. H., Stapelmann, K., & Kushner, M. J. (2023). Reaction mechanism for atmospheric pressure plasma treatment of cysteine in solution. Journal of Physics D Applied Physics, 56(39), 395205. [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, B., Hirth, M., & Kogelschatz, U. (1987). Ozone synthesis from oxygen in dielectric barrier discharges. Journal of Physics D Applied Physics, 20(11), 1421–1437. [CrossRef]

- Sakiyama, Y., Graves, D. B., Chang, H., Shimizu, T., & Morfill, G. E. (2012). Plasma chemistry model of surface microdischarge in humid air and dynamics of reactive neutral species. Journal of Physics D Applied Physics, 45(42), 425201. [CrossRef]

- Trostchansky, A., Moore-Carrasco, R., & Fuentes, E. (2019). Oxidative pathways of arachidonic acid as targets for regulation of platelet activation. Prostaglandins & Other Lipid Mediators, 145, 106382. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., Duan, W., Zhang, J., Hao, M., Li, J., Zhao, R., Wu, W., Sua, H. H., Jun, H. K., Liu, Y., Lu, Y., Liu, Y., & Liu, S. (2025). Superhydrophobic ROS biocatalytic metal coatings for the rapid healing of diabetic wounds. Materials Today Bio, 32, 101840. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, M. A., Bychkova, A. V., Shchegolikhin, A. N., Leonova, V. B., Kostanova, E. A., Biryukova, M. I., Sultimova, N. B., & Konstantinova, M. L. (2016). Fibrin self-assembly is adapted to oxidation. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 95, 55–64. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).