1. Introduction

Pesticides have been a very useful tool to control pests that affect food production; however, their unregulated use poses a major problem, particularly in developing countries where the necessary measures have not been implemented [

1]. Consequently, the absorption of pesticides generates oxidative stress due to the overproduction of free radicals, which triggers various damage mechanisms in the organism.

One of the first barriers to neutralize free radicals are endogenous antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT), which help counteract them by preventing the oxidation of cell membranes and other key compounds, thereby reducing the risk of chronic degenerative diseases [

2]. The problem worsens when the amount of free radicals far exceeds the endogenous antioxidant capacity, leading to cellular damage and other malformations. For this reason, it is necessary to investigate the role of exogenous bioactive compounds as potential alternatives for neutralizing these oxidative molecules.

Phycocyanin may represent such an alternative, as it is a protein-derived pigment with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, primarily used as a natural food colorant. Its consumption is simple since it is a water-soluble protein, which allows its incorporation into juices, ice creams, or smoothies. It is preferably consumed in cold preparations to avoid the loss of its properties and, particularly, its characteristic blue color [

3]. Therefore, phycocyanin could act as a compound capable of neutralizing free radicals generated by pesticide exposure.

Pesticides can not only be absorbed or inhaled by living organisms, but they can also be present in the food we consume. Once digested and absorbed through the intestine, they reach the bloodstream, where cellular damage may begin, particularly at the erythrocyte membrane, causing lipid oxidation and the formation of free radicals such as peroxyl, which induce hemolysis (erythrocyte destruction). Some studies suggest that certain compounds may show affinity for specific ABO and Rh (+/–) blood groups [

4]. However, no such studies have yet been conducted for either pesticides or phycocyanin. Phycocyanin is thus proposed as a potential buffer against oxidative damage due to its strong antioxidant capacity.

Moreover, in this context it is important to evaluate the effect of pesticides and phycocyanin under a model more closely resembling the physiological function of the organism. Therefore, in vitro gastrointestinal simulation is a key tool to generate the bioavailable fraction, which is the most suitable for assessing adverse effects and potential inhibition of damage following exposure through food consumption.

2. Results

2.1. Evaluation of Pesticide Cytotoxicity

2.1.1. Determination of Cytotoxicity Induced by 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid in ABO System Erythrocytes

Figure 1 shows the determination of the cytotoxicity of the pesticide 2,4-D on ABO system erythrocytes after a 3-hour exposure at different concentrations.

Figure 2 shows the determination of the cytotoxicity of the pesticide 2,4-D on ABO system erythrocytes after a 3-hour exposure.

2.1.2. Evaluation of the Cytotoxicity of Imidacloprid in ABO System Erythrocytes

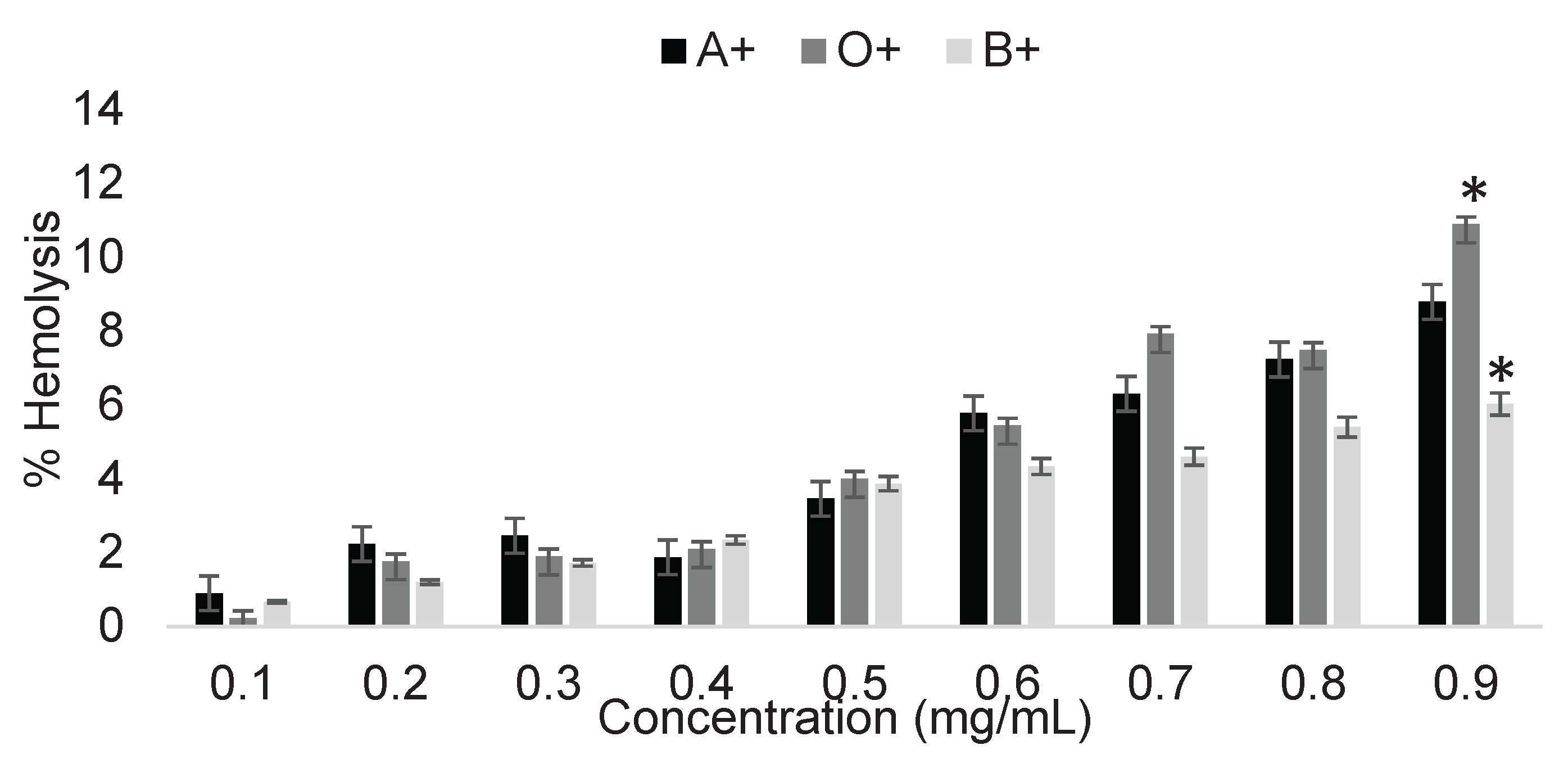

Figure 3 shows the determination of imidacloprid cytotoxicity at concentrations of 0.1–0.5 mg/mL, yielding hemolysis percentages ranging from 20 to 99% in ABO system erythrocytes.

2.1.3. Erythroprotective Effect of Phycocyanin on ABO System Erythrocytes

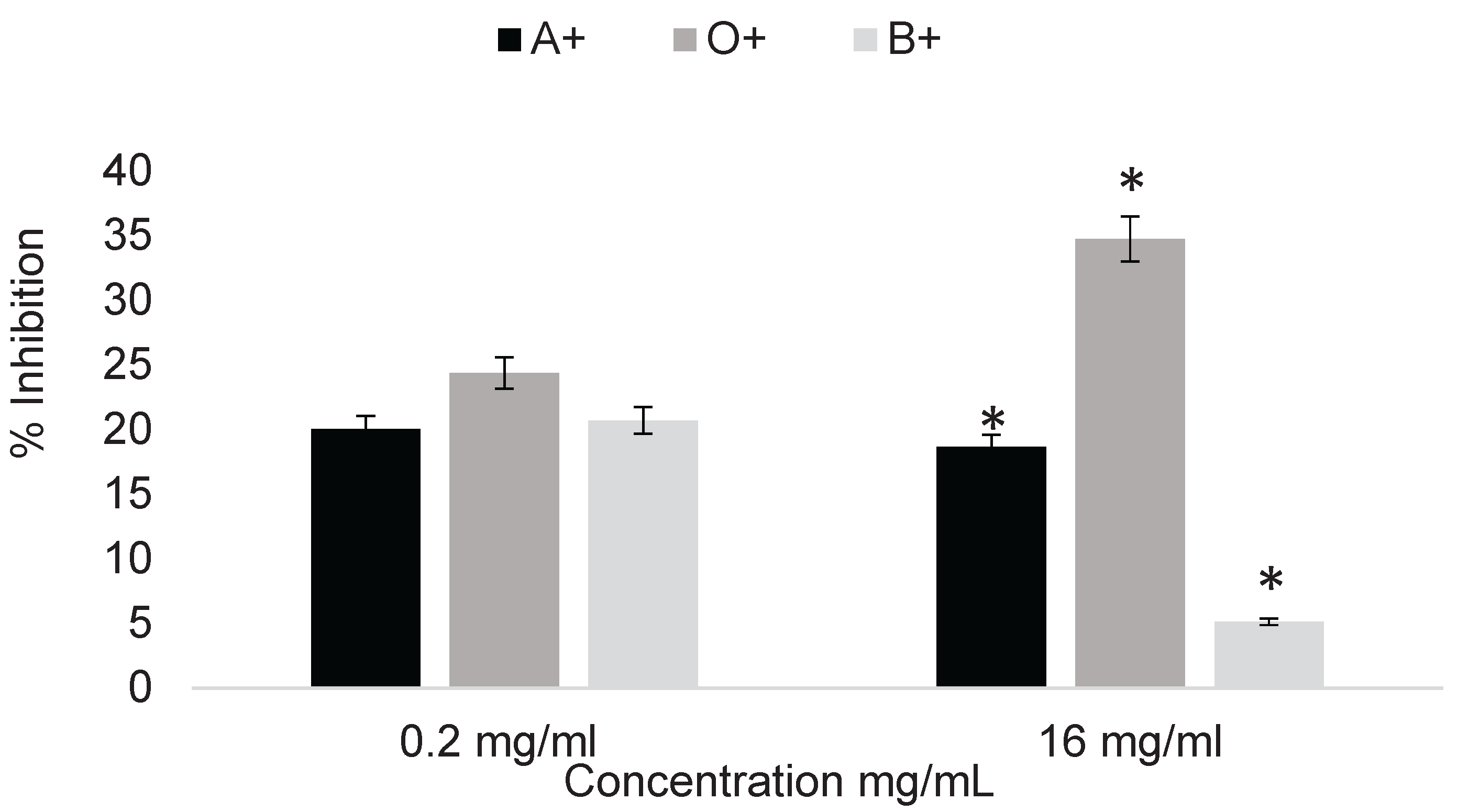

Determination of the erythroprotective effect of phycocyanin at 0.5 mg/mL on pesticide-exposed erythrocytes. A percentage of inhibition ranging from 5 to 35% of pesticide-induced damage was obtained.

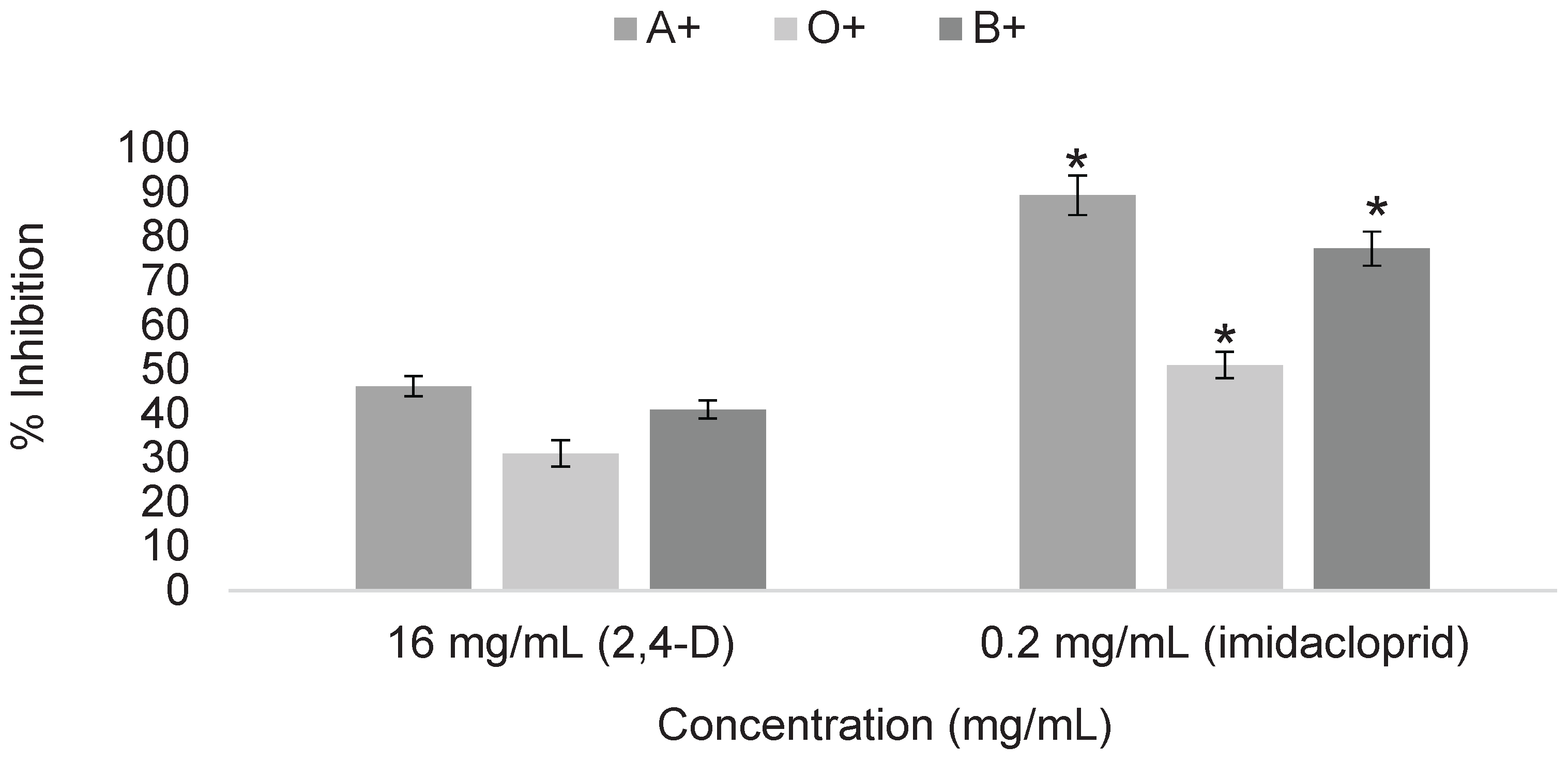

Figure 4.

Erythroprotective effect of phycocyanin on ABO erythrocytes exposed to pesticides at selected concentrations of 16 mg/mL for 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 0.2 mg/mL for imidacloprid. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between blood types.

Figure 4.

Erythroprotective effect of phycocyanin on ABO erythrocytes exposed to pesticides at selected concentrations of 16 mg/mL for 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 0.2 mg/mL for imidacloprid. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between blood types.

Figure 5 demonstrates the erythroprotective effect of phycocyanin at 1 mg/mL on pesticide-exposed erythrocytes, showing an inhibition effect ranging from 31 to 89%.

2.2. In Vitro Digestion of Phycocyanin

2.2.1. Cytotoxicity of Digested Fractions of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid on ABO System Erythrocytes

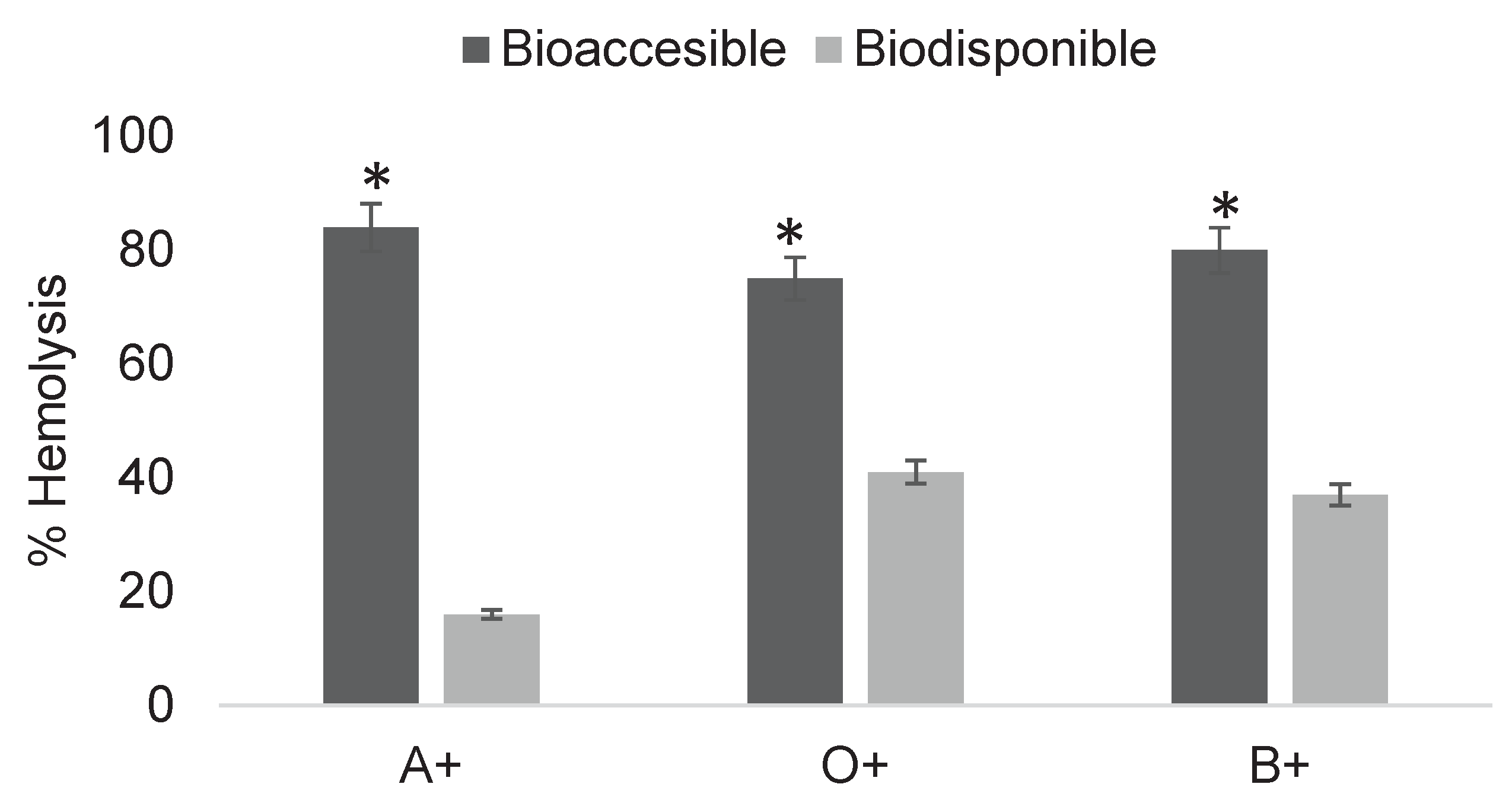

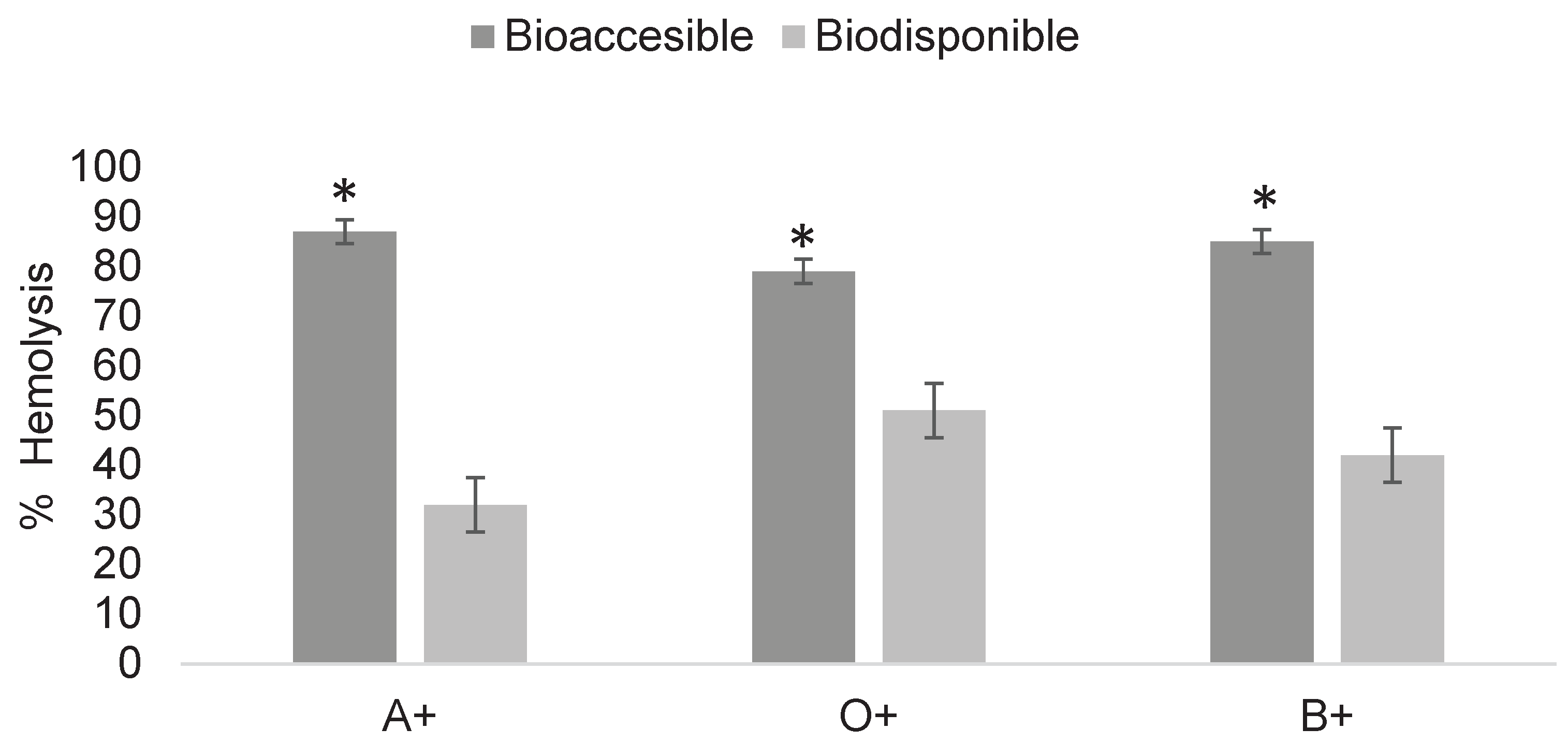

The cytotoxic effect of post-digestion fractions of the pesticide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid was determined (

Figure 6). Hemolysis levels ranged from 32 to 87%, with the bioavailable fractions causing less erythrocyte damage.

The same determination was performed at a reduced concentration of 16 mg/mL, yielding hemolysis values ranging from 16 to 84% across digestion phases.

Figure 7.

Determination of cytotoxicity of digested fractions of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid at 16 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions. Results were obtained using Triton X as a positive control for 100% hemolysis and unexposed erythrocytes as the negative control for 0%.

Figure 7.

Determination of cytotoxicity of digested fractions of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid at 16 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions. Results were obtained using Triton X as a positive control for 100% hemolysis and unexposed erythrocytes as the negative control for 0%.

2.2.2. Cytotoxicity of Digested Fractions of Imidacloprid on ABO System Erythrocytes

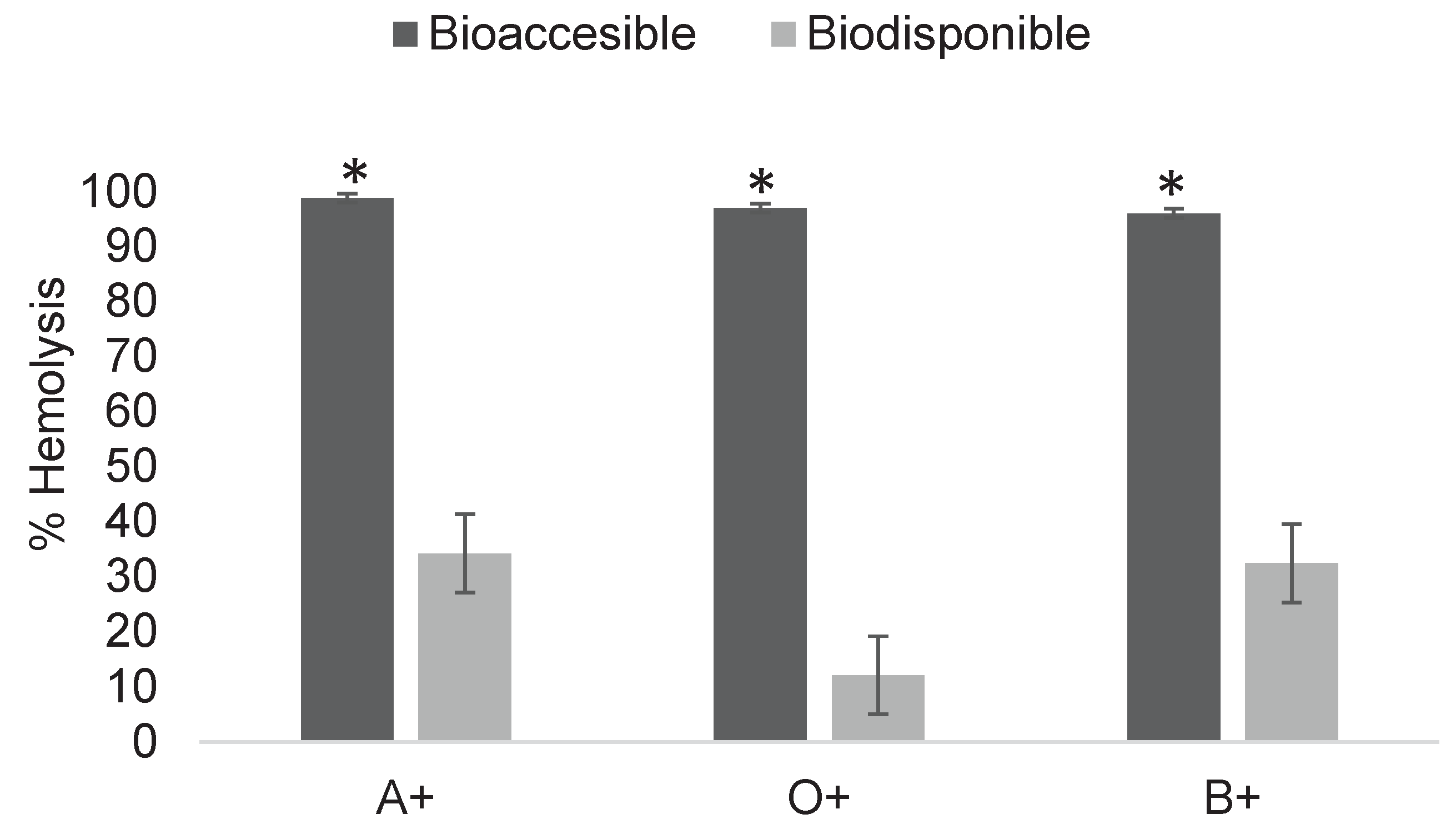

Figure 8. shows the cytotoxicity of post-digestion fractions of imidacloprid at 0.3 mg/mL, with hemolysis values ranging from 12 to 98% across digestion phases.

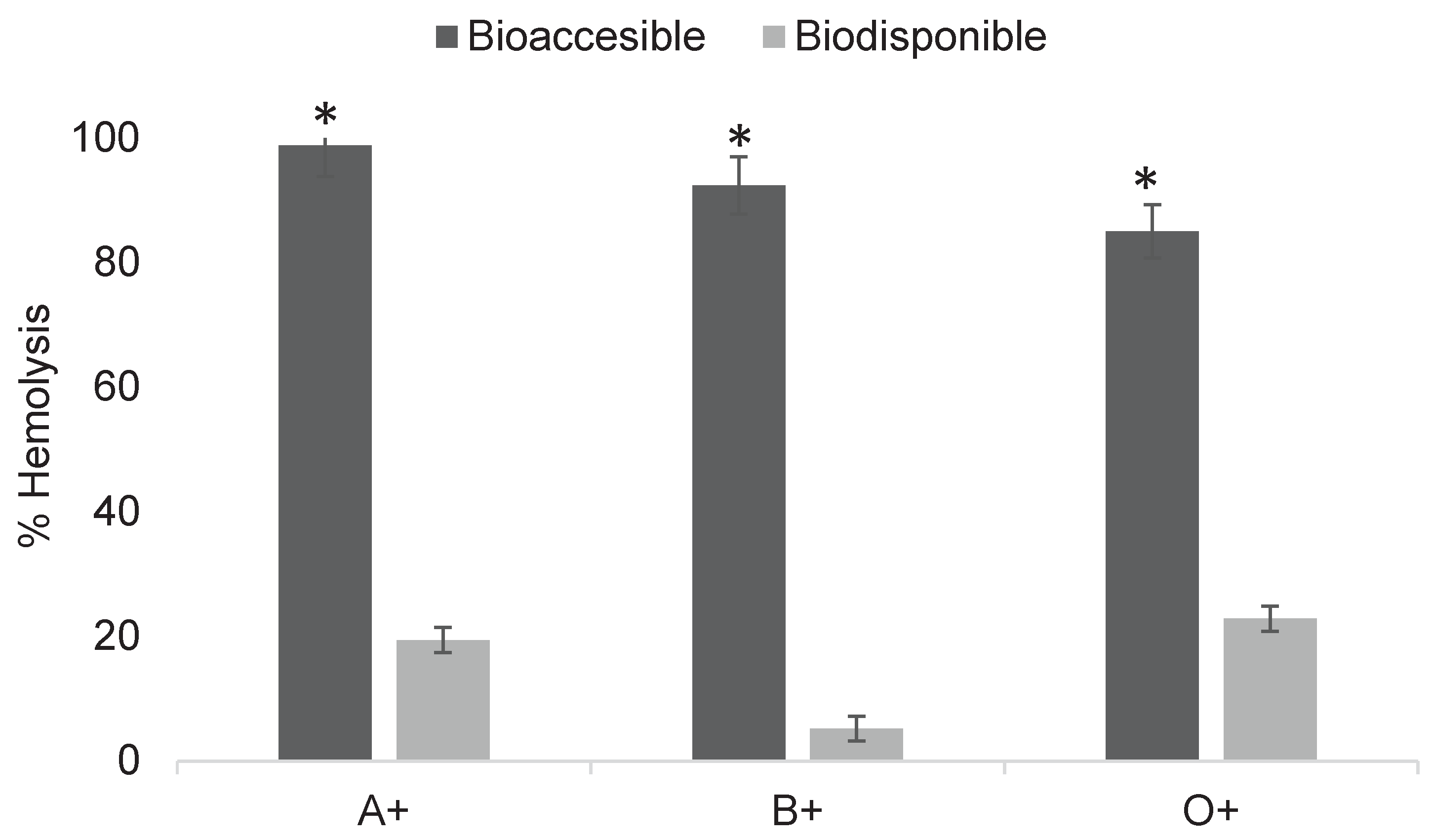

Figure 9 shows the cytotoxicity of post-digestion fractions of imidacloprid at 0.3 mg/mL, with hemolysis values ranging from 5 to 98% across digestion phases.

2.2.3. Erythroprotective Effect of Digested Phycocyanin Fractions on ABO System Erythrocytes Exposed to 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid

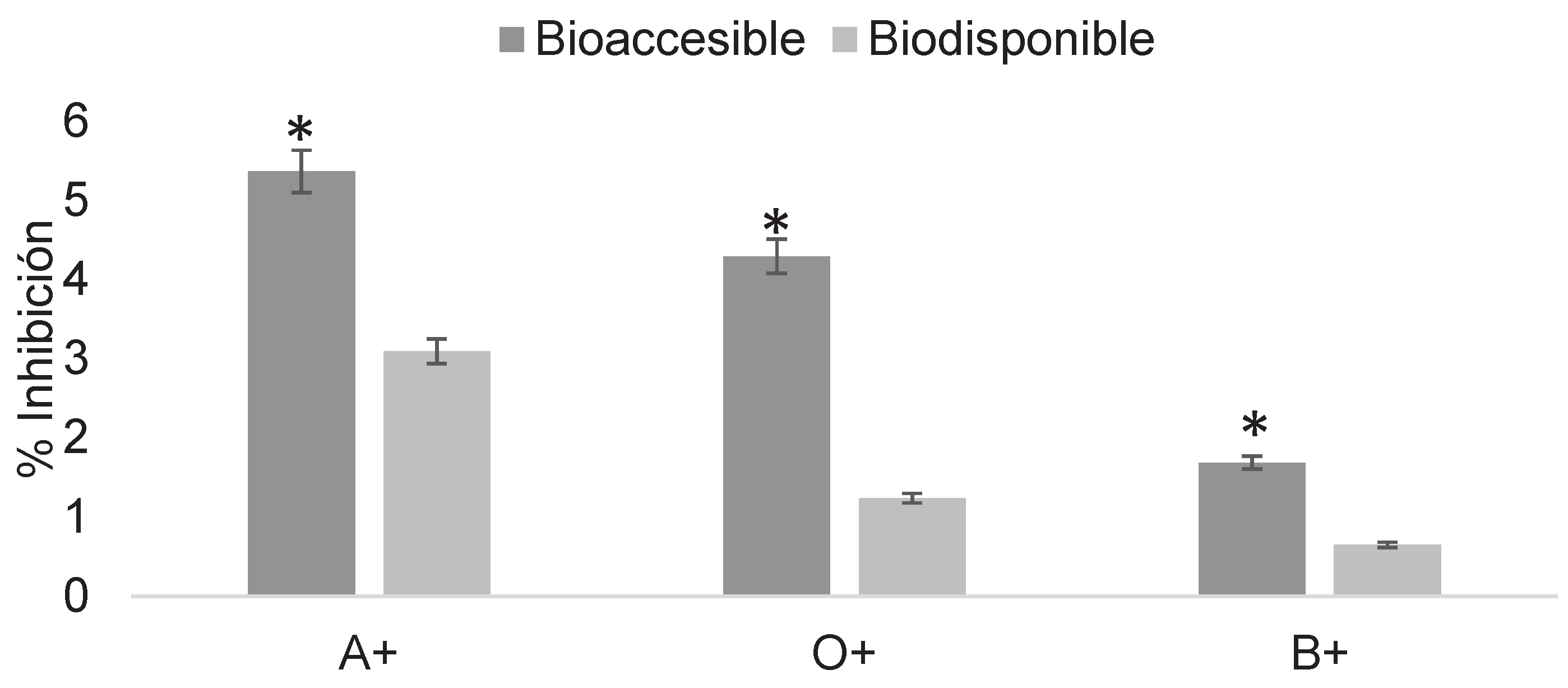

Figure 10 shows the erythroprotective effect of phycocyanin at 1 mg/mL post-digestion on erythrocytes exposed to 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, with relatively low inhibition values ranging from 0.65 to 5%.

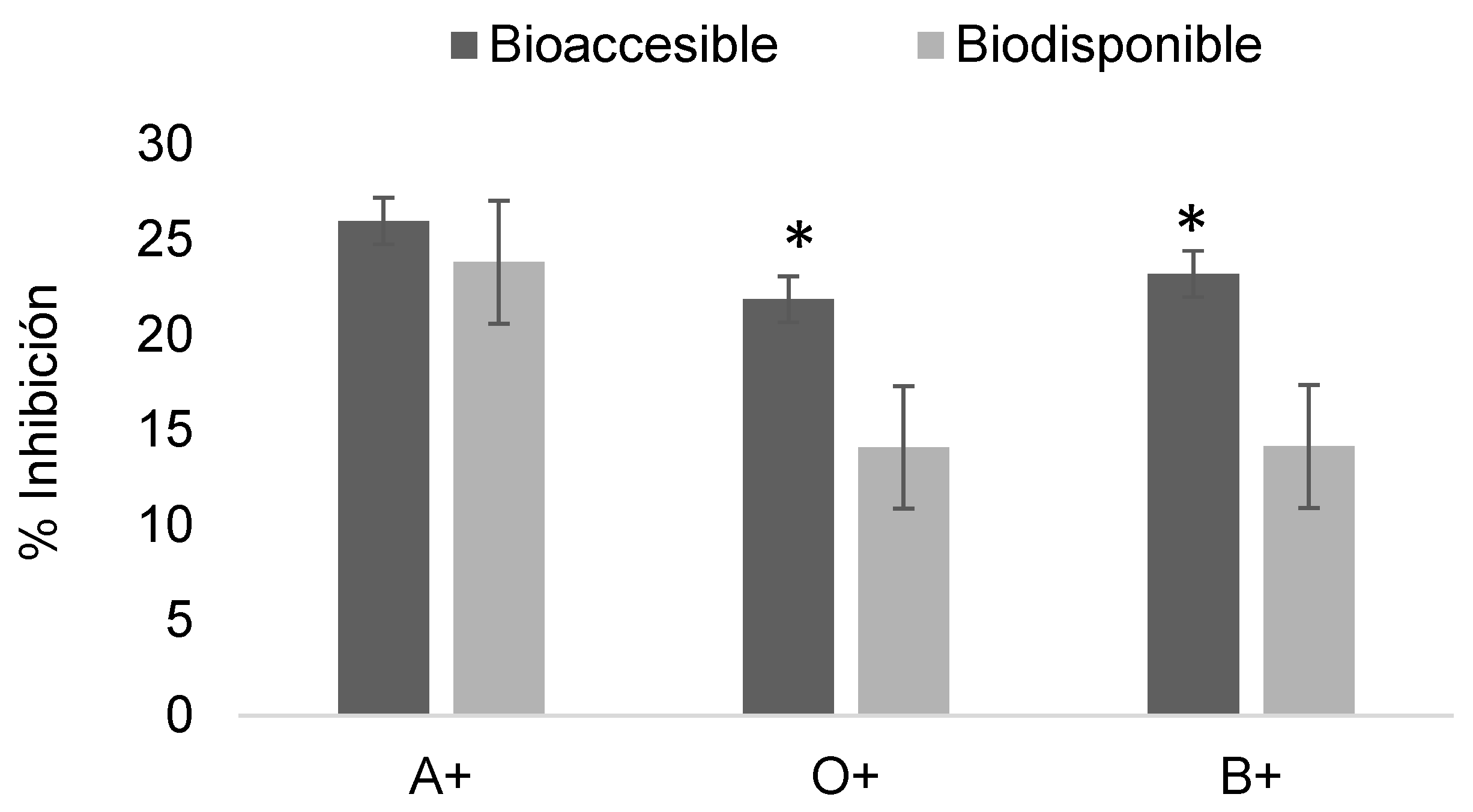

Figure 11 shows the erythroprotective effect of phycocyanin at 2 mg/mL post-digestion on erythrocytes exposed to 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, with relatively low inhibition values ranging from 14 to 26%.

2.2.4. Erythroprotective Effect of Digested Phycocyanin Fractions on ABO System Erythrocytes Exposed to Imidacloprid

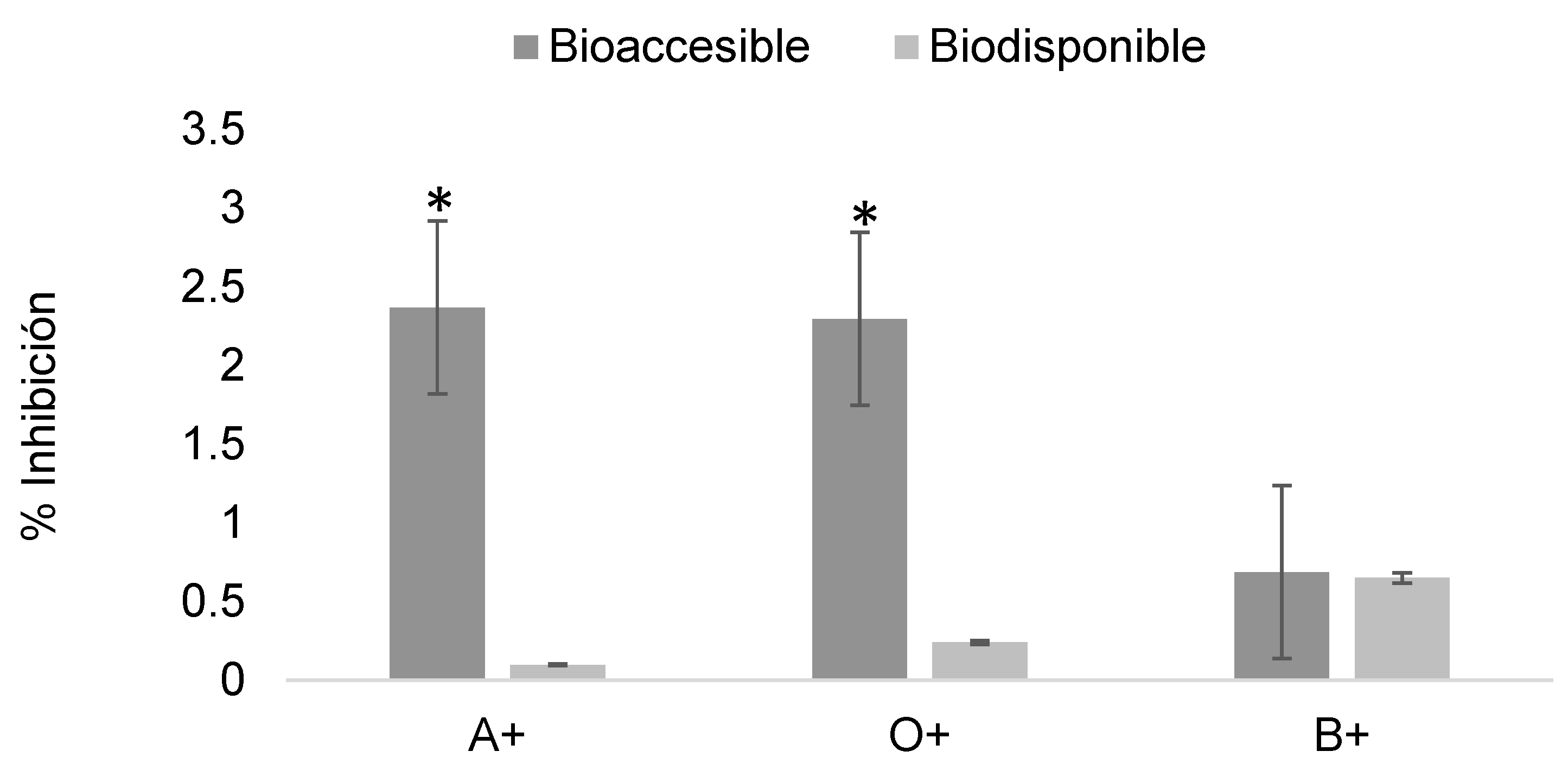

Figure 12 shows the erythroprotective effect of phycocyanin at 1 mg/mL post-digestion on erythrocytes exposed to imidacloprid, with relatively low inhibition values ranging from 0 to 2%.

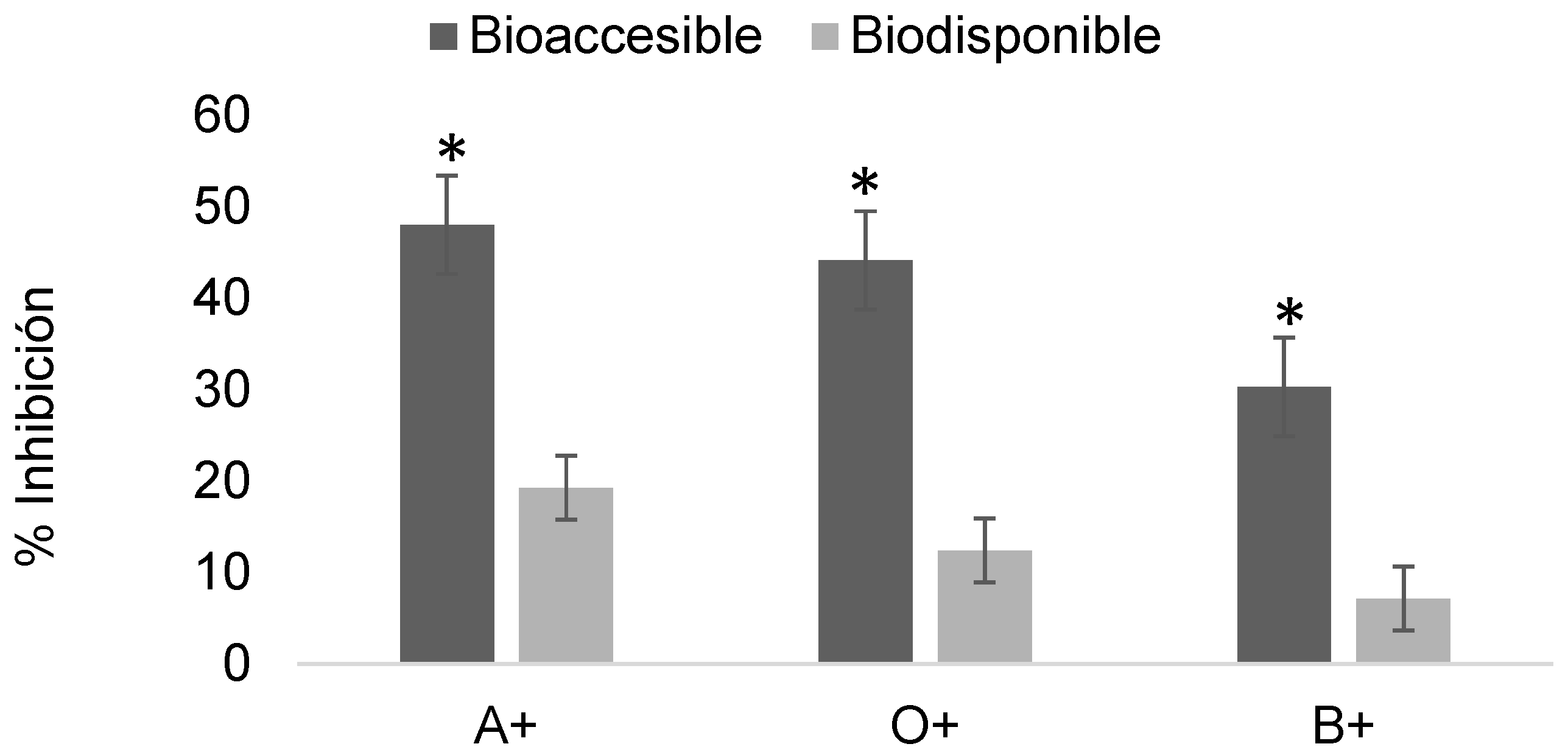

Figure 13 shows the erythroprotective effect of phycocyanin at 2 mg/mL post-digestion on erythrocytes exposed to imidacloprid, with relatively low inhibition values ranging from 0 to 2%

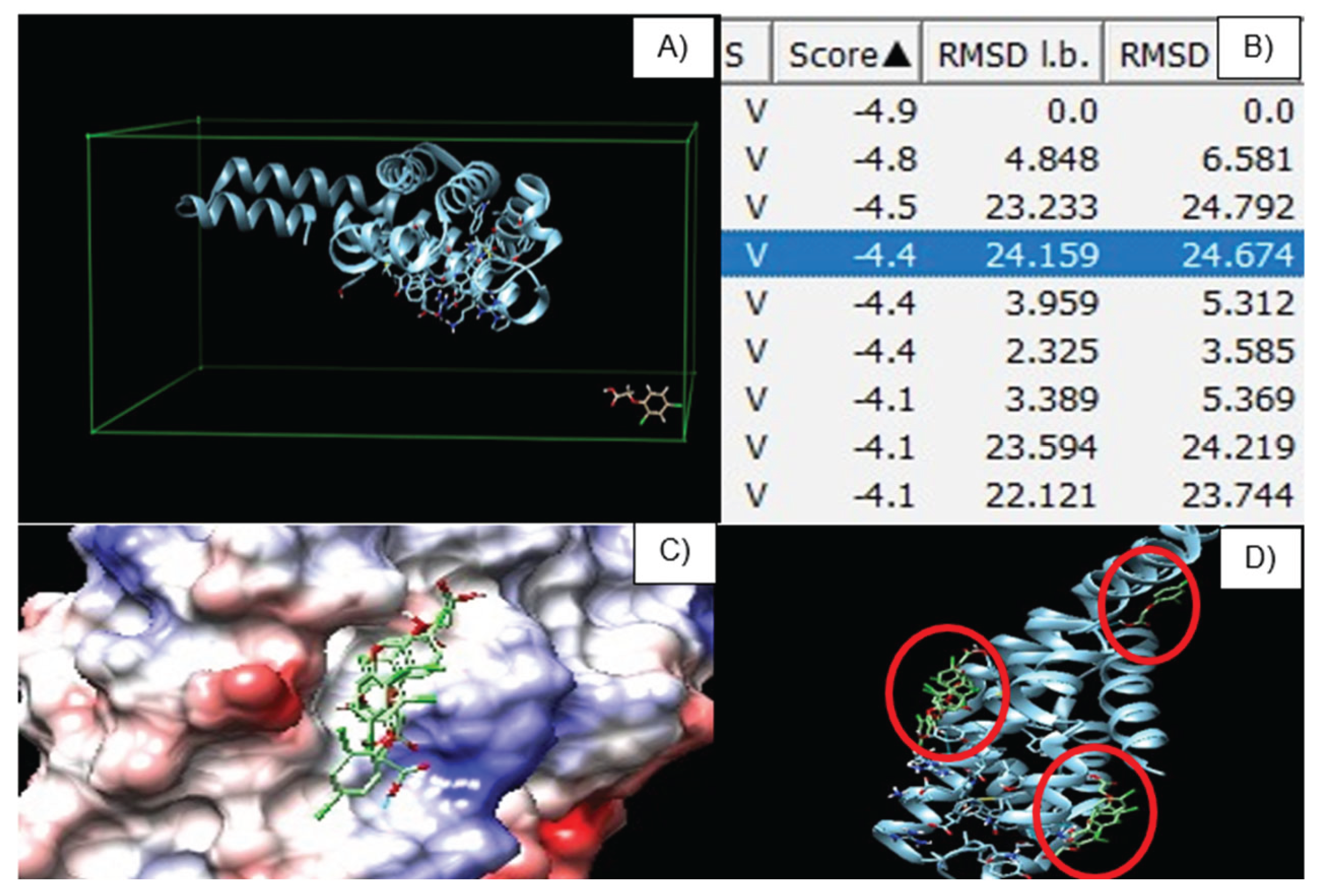

2.3. Unbiased Molecular Docking of C-Phycocyanin with 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid

Molecular docking of the β subunit of C-phycocyanin with 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid as ligand was performed using ChimeraX and the AutoDock Vina plugin.

3. Discussion

3.1. Determination of Cytotoxicity Induced by 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid in ABO System Erythrocytes

The cytotoxicity of the pesticide 2,4-D (2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) was evaluated based on the average consumption of foods with different maximum residue limits (MRLs), which range from 0.15 to 100 mg/kg according to the Codex Alimentarius. Although these values vary depending on the food, establishing an average is essential to determine the concentrations at which this compound begins to be harmful when directly interacting with erythrocytes.

Exposure of erythrocytes to concentrations of 0.1 to 0.9 mg/mL resulted in a low margin of damage. These concentrations did not generate statistically significant damage between blood types in at least the first eight concentrations. However, hemolysis percentages of up to 10% were observed at 0.9 mg/mL, marking the first statistically significant difference between blood groups (

Figure 1). Although the damage generated was relatively low, this may be due to an insufficient number of molecules to induce significant oxidative stress. It is also important to note the possibility that residual proteins from whole blood remained after erythrocyte washing, which, due to their amino acid residues, could limit the cytotoxic potential of 2,4-D at these concentrations, even when following precisely the methodology described by González-Vega [

5].

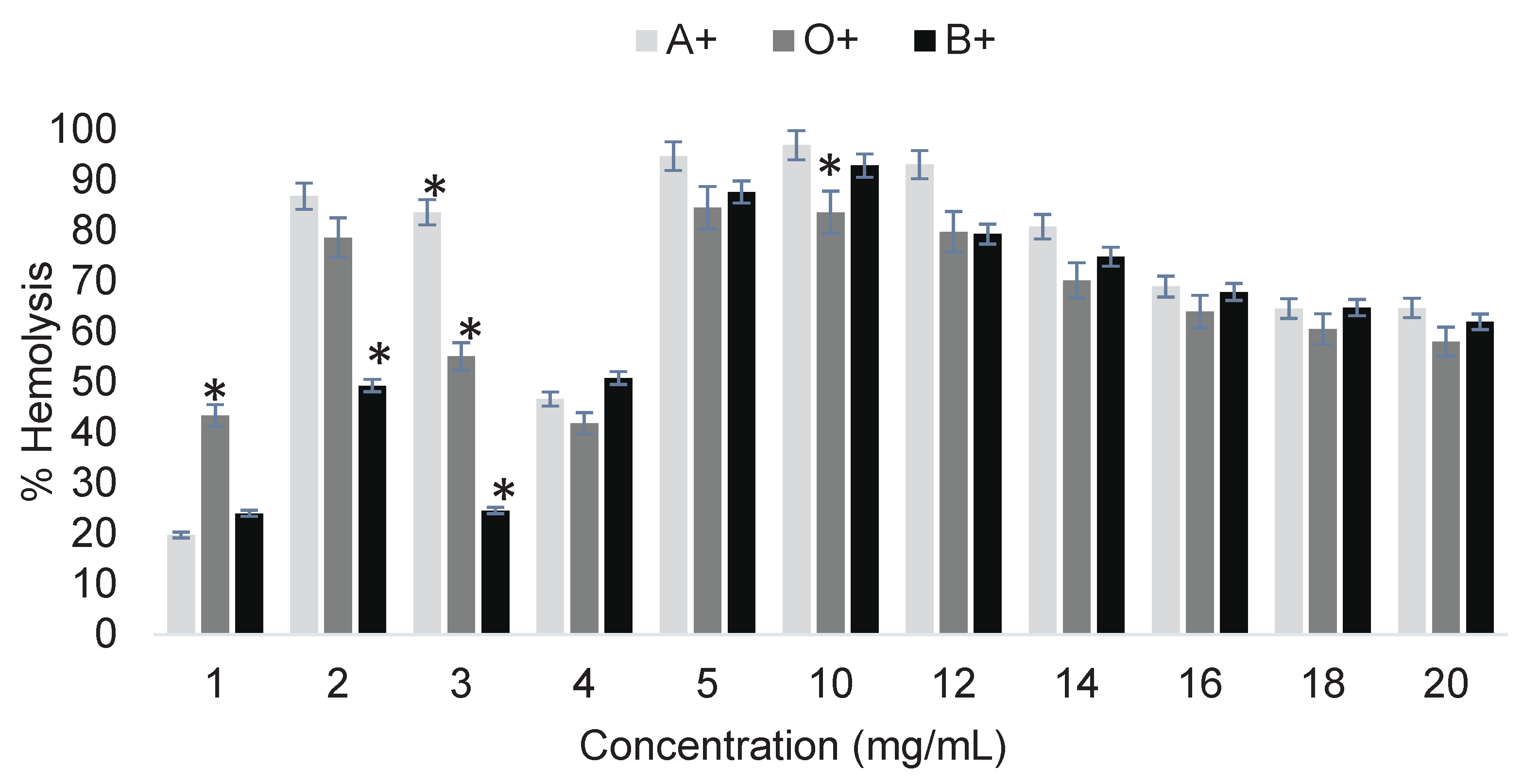

The cytotoxicity results of 2,4-D on erythrocytes showed hemolysis percentages ranging from 20 to 97%, depending on concentration and blood type (

Figure 2). The toxicity caused by 2,4-D varied according to concentration, and the damage did not increase linearly with increasing concentration. The behavior of 2,4-D lacks linearity, meaning it does not consistently produce greater damage as the concentration increases. This toxicological phenomenon is known as hormesis, which is related to the stimulation or inhibition of certain biochemical or molecular processes depending on concentration. For example, a low dose may inhibit a biochemical process, but a higher dose does not necessarily increase inhibition; instead, it may induce stimulation, the opposite effect of what is expected, as reported in various studies. One example is the research by Mahmoudinia [

6], which concluded that treatment with 2,4-D induced a hormetic response in the viability and growth rate of human dental pulp stem cells.

This behavior is common in studies involving plants and pharmaceuticals. Hormesis is widely induced by various mixtures of stress-inducing agents in plants, microbes, and other life forms that potentially interact with the analyzed sample. There is no single biological mechanism of hormesis, only general mechanisms [

7]. Although the present study differs in nature, this perspective helps to understand the trend observed when 2,4-D interacts with erythrocytes.

3.2. Evaluation of the Cytotoxicity of Imidacloprid in ABO System Erythrocytes

The cytotoxicity results of the pesticide imidacloprid on erythrocytes showed hemolysis percentages ranging from 19 to 97%, depending on concentration and blood type (

Figure 3). The damage caused by imidacloprid demonstrated that from 0.3 mg/mL onwards, sample saturation was reached, producing approximately 90% hemolysis in subsequent treatments. The initial exposure at 0.1 mg/mL revealed a significant difference between blood groups under the same conditions. The B+ blood type was found to be the most susceptible to damage from imidacloprid. This result implies that even at low concentrations, exposure can generate differential damage depending on the individual’s blood type.

Imidacloprid is a neonicotinoid pesticide characterized by rapid gastrointestinal absorption, leading to direct interaction with blood components. Although not intended for human use, its mechanism of action is similar across different organisms. Previous studies suggest that continuous exposure to this pesticide results in bioaccumulation, which may give rise to adverse effects not directly related to acute intoxication. Such exposures have been associated with deterioration of the central nervous system and the development of diabetes in non-target mammals [

8,

9,

10].

3.3. Erythroprotective Effect of Phycocyanin on ABO System Erythrocytes

After determining the cytotoxicity of the selected pesticides, representative concentrations were chosen for the treatments. The selected concentrations were 16 mg/mL for 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 0.2 mg/mL for imidacloprid, since higher concentrations represent limited applicability for determining the erythroprotective effect of phycocyanin due to the strong cytotoxicity they generate. Treatment with phycocyanin at 0.05 mg/mL was able to mitigate pesticide-induced damage by up to 34%. This effect varied depending on the pesticide involved, its concentration, and the blood type analyzed. In the case of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, blood type O+ benefited the most from phycocyanin treatment, followed by A+ and B+, while imidacloprid showed no significant differences among blood groups (

Figure 4).

Treatment with phycocyanin at 1 mg/mL was able to reduce pesticide-induced damage by up to 90%, with the effect varying according to both the blood type and the pesticide tested (

Figure 5). Significant differences between blood types were observed. The erythroprotective effect increased with higher phycocyanin concentrations. In the case of imidacloprid, significant differences were observed among A+, B+, and O+ blood types. For 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, no significant differences were found between blood types; however, the erythroprotective effect was considerably higher compared to the determination at 0.5 mg/mL (

Figure 4).

The erythroprotective effect of phycocyanin is attributed to its strong antioxidant capacity, which is based on its amino acid residues and chromophore content that can donate electrons from functional groups or through resonance due to conjugated double bonds in the phycocyanobilin chromophore [

11]. The protective effect may also be related to the high reactivity of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, which makes it more prone to being scavenged given the size (220 kDa) and chromophore abundance of phycocyanin. This must be considered when analyzing the interaction with both the pesticide and the erythrocyte membrane, since the large size and heterogeneity of phycocyanin do not guarantee uniform binding [

12].

The results of the erythroprotective effect of phycocyanin against pesticide-induced oxidative damage demonstrated differential efficiency when interacting with erythrocytes from different blood types. This difference is attributed to the structural heterogeneity of each group due to the composition of membrane carbohydrates, which alters the cellular interaction with phycocyanin. In other words, the interaction between both components varies because of changes in membrane antigens: group O presents a basic antigenic structure, group A incorporates N-acetylgalactosamine, and group B incorporates galactose. These differences modify the reaction microenvironment, polarity, and affinity with external compounds. Such structural variations influence not only the orientation and binding of phycocyanin to the erythrocyte membrane but also the extent of oxidative stress propagation induced by pesticides.

3.4. Cytotoxicity of Digested Pesticide Fractions on ABO System Erythrocytes

In vitro digestions were performed to evaluate the cytotoxic potential of the selected pesticides, simulating the fraction absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract and thereby contrasting the results of direct interaction with erythrocytes. The cytotoxicity of the digested fractions was assessed, where the bioaccessible fraction corresponds to the phase subjected to the three digestive stages without crossing the dialysis membrane, while the bioavailable fraction represents the phase that permeates the dialysis membrane. Cermeño Olmos (2016) [

13] concluded that, under critical cultivation conditions in different vegetables, detectable values of pesticides may be found after food consumption with traces. However, he emphasized that for most pesticides, enzymes do not cause significant structural changes in xenobiotics, but rather in the food matrix, which modifies gastrointestinal absorption.

The results (

Figure 6) show the bioaccessible and bioavailable fractions of pesticides after in vitro digestion, with values of 87 and 32% in A+, 79 and 51% in O+, and 85 and 42% in B+. In all three blood types, a significant difference was observed between fractions, consistent with Cermeño Olmos (2016), indicating that the bioaccessible fraction is less biocompatible with erythrocytes than the bioavailable fraction. Nevertheless, the bioavailable fraction also showed the ability to generate damage in erythrocyte interactions, although at reduced levels due to its lower concentration.

The determination of cytotoxic potential after digestion is essential to understanding mechanisms of damage. For 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, the presence of an ionizable carboxyl group at physiological pH allows it to circulate more freely in the organism and be eliminated renally via OAT1 and OAT2 transporters. This facilitates systemic interaction, promoting mitochondrial effects that generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), in addition to possible alterations of the thyroid endocrine system [

14,

15,

16].

Lower concentrations of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (

Figure 7) reduced its bioavailable fraction due to the efficiency of physical barriers in intestinal absorption. Added to this are in vivo factors such as polarity, lipophilicity, and xenobiotic molecular weight, which further hinder absorption, thus justifying the behavior observed in

Figure 7. ATSDR (2020) reports that 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid is rapidly absorbed after oral intake, undergoes minimal metabolism, and is eliminated primarily in urine, indicating that barriers such as intestinal metabolism or efflux are not determinants of its bioavailability.

Similar conditions influence imidacloprid absorption, although variations occur due to its molecular composition. Migration across the membrane was observed; for example, in O+ (

Figure 8), the bioavailable fraction produced a considerably lower percentage of hemolysis compared to the bioaccessible fraction. While the initial concentration induced 97% hemolysis, the bioavailable fraction caused only 13%, corresponding to an approximate concentration of 0.22 mg/mL. This trend was consistent across all blood groups. As shown in

Figure 9, although concentrations were lower, both fractions continued to generate damage, with significant differences between bioaccessible and bioavailable fractions after in vitro digestion.

In

Figure 9, all three blood types exposed to the bioaccessible fraction showed hemolysis values of around 90%. In contrast, the bioavailable fraction showed lower hemolysis percentages ranging from 5 to 22%, depending on blood type. The concentration of the bioavailable fraction was determined after dialysis as 0.171 mg/mL using a spectrophotometric calibration curve of different imidacloprid concentrations.

As with 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, the gastrointestinally absorbed fraction of imidacloprid induces adverse health effects beyond direct cellular damage. Once in the organism, imidacloprid is metabolized primarily in the liver via cytochrome P450 enzymes, producing metabolites such as 5-hydroxy-imidacloprid, imidacloprid-olefin, and, of particular relevance, desnitro-imidacloprid. This metabolite exhibits affinity for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mammals, generating indirect neurotoxicity. Moreover, both the unmetabolized compound and its metabolites increase ROS production, enhancing the activation of signaling pathways such as Nrf2 and NF-κB, thereby promoting chronic inflammation, lipid peroxidation, and a general imbalance in the antioxidant system. According to several authors, continuous exposure to this pesticide amplifies systemic oxidative damage and predisposes to metabolic alterations and endothelial dysfunction [

17,

18,

19,

20].

3.5. Erythroprotective Effect of Digested Phycocyanin Fractions on ABO System Erythrocytes Exposed to 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid

Similar to pesticides, phycocyanin must undergo the digestive process to yield bioavailable fractions. These fractions were tested for their ability to inhibit damage caused by previously evaluated pesticide concentrations, in order to assess their erythroprotective potential once absorbed by the organism and to contrast their inhibitory action on erythrocytes.

Figure 10 shows the erythroprotective effect after digestion, with maximum inhibition values of 5% in the bioaccessible fraction and 3% in the bioavailable fraction for A+, which exhibited the highest percentages. These values are almost negligible against 18 mg/mL concentrations of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. This behavior is primarily due to the fact that, during in vitro digestion, the initial concentration is diluted by digestive enzymes and buffer, reducing its erythroprotective potential in addition to the high level of damage generated by the pesticide. Based on these results, subsequent determinations were carried out using higher phycocyanin concentrations and lower pesticide exposure levels (

Figure 11).

In the case of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid at 16 mg/mL (

Figure 11), the erythroprotective effect was observed in both digested fractions despite dilution. Inhibition percentages of up to 23% were recorded in the bioavailable fraction. These percentages varied according to blood type, with significant differences observed between O+ and B+ across digestion fractions. This effect can be attributed to conformational changes induced by digestive enzymes, which through hydrolysis generate smaller fragments compared to the complete protein, which naturally exists as two alpha-beta hexamers. In this form, phycocyanin has a molecular weight of approximately 480 kDa, classifying it as a large protein. Cleavage of peptide chains increases the reactive surface area available for interaction with both the pesticide and erythrocytes. Moreover, the generation of protein fragments results in the exposure of phycocyanobilin chromophores within the protein, theoretically enhancing its antioxidant potential. This explains why the protective effect was observed despite the dilutions generated during in vitro digestion [

21,

22].

Thus, increasing the concentration of phycocyanin resulted in a greater erythroprotective effect; however, the potential of this protein could be further exploited through the use of more aggressive hydrolysis methods, which would also facilitate intestinal absorption.

3.6. Erythroprotective Effect of Digested Phycocyanin Fractions on ABO System Erythrocytes Exposed to Imidacloprid

The trend observed at higher concentrations was also maintained with imidacloprid. The levels of damage generated limited the erythroprotective potential, yielding almost negligible values in both fractions across the three blood types (

Figure 12).

When the exposure concentration was reduced and the concentration of phycocyanin in the digested fractions was increased, the erythroprotective effect was preserved even after dilution during the assay. Inhibition values reached nearly 50% in the bioaccessible fraction and maintained effectiveness up to 20% in the bioavailable fraction (

Figure 13). The determination of the erythroprotective effect against imidacloprid revealed a more favorable interaction compared to 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid.

The greater erythroprotective efficacy against imidacloprid can be explained by the fact that its toxicity in erythrocytes is predominantly oxidative and occurs at the membrane interface, where digested phycocyanin fractions scavenge radicals and stabilize the lipid bilayer. In contrast, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid combines an oxidative component with anion-dependent and proteotropic mechanisms, which are less sensitive to ROS neutralization alone, resulting in comparatively lower protection [

22,

23,

24].

3.7. Unbiased Molecular Docking of C-Phycocyanin with 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid

Molecular docking revealed nine potential binding sites between the beta subunit of C-phycocyanin and the pesticide 2,4-D as ligand (

Figure 14A). The docking results showed binding energies ranging from –4 to –5 kcal/mol, suggesting moderate to low affinity (

Figure 14B). These values are better interpreted as transient contacts resulting from steric hindrance rather than a specific binding site. It is proposed that 2,4-D, which exists in an anionic form at physiological pH, could form hydrogen bonds or ionic pairs with surface residues such as lysine, arginine, or histidine, and may even weakly stack with the tetrapyrrolic ring of the phycocyanobilin chromophore [

25].

2,4-D does not require a protein residue or enzymatic activation to damage cell membranes, its mechanism of action may be based on the direct oxidation of structural cell components. Nevertheless, due to the complexity of the molecule, these weak interactions may mitigate damage by neutralizing ROS produced by the pesticide through ligand scavenging. Such a mechanism becomes more feasible at higher concentrations [

26,

27,

28].

The docking scores, RMSD l.b. values, and poses obtained do not suggest a relationship between the ligand interaction and the chromophoric sites of the protein, neither in terms of affinity nor biological function (

Figure 14C). Since phycocyanin does not present a defined active site, its main points of interest are Cys82 and Cys153 of the beta chain, which anchor the chromophores to the protein backbone (

Figure 14D). The interactions observed in the docking instead support the existence of “grooves” with low steric hindrance that generate moderate attraction through amino acid residues such as Lys, Arg, and His, which are capable of forming hydrogen bonds or ionic interactions [

29].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Evaluation of the Cytotoxicity of Pesticides and Phycocyanin

Red blood cell (RBC) samples from A, B, and O blood types with positive Rh factor were collected by venipuncture in EDTA tubes. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were detailed in the informed consent provided to each volunteer. A 2% erythrocyte suspension was prepared from all blood groups by washing the cells with physiological saline until the plasma was completely removed (transparent supernatant). In Falcon tubes, 3000 µL of physiological saline + 1000 µL of blood were added and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 252 × g. The supernatant containing saline and platelets was removed, and 3000 µL of saline solution were added to the erythrocytes, followed by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 252 × g. This procedure was repeated two more times. The supernatant (saline solution and plasma) was discarded, and 5000 µL of physiological saline were added to the erythrocytes to obtain a 2% erythrocyte suspension.

Subsequently, 100 µL of erythrocyte suspension were mixed with 100 µL of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid solution (herbicide) at concentrations of 2–20 mg/mL. Additionally, 100 µL of erythrocyte suspension were mixed with 100 µL of imidacloprid solution (insecticide) at concentrations of 0.1–0.5 mg/mL. The positive control consisted of 100 µL of 10% Triton + 100 µL of erythrocyte suspension, since this treatment completely disrupts the cell membrane, while the negative control was the erythrocyte suspension without treatment. Samples were incubated in a thermostatic water bath (BIOBASE series, SKU 56202) for 3 hours at 37 °C with gentle agitation at 40 rpm. After incubation, the samples were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 252 × g.

Then, 300 µL of the supernatant were transferred to wells of a microplate (Thermo Scientific, Multiskan SkyHigh, USA). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate at 540 nm. Cytotoxicity was evaluated by determining the percentage of hemolysis using Equation 1 [

5].

Equation 1:

Where Aₘ is the absorbance of the pesticide-treated samples, A₍c+₎ is the absorbance of the positive control, and A₍c–₎ is the absorbance of the negative control.

4.2. Erythroprotective Effect of Phycocyanin

Phycocyanin was used to evaluate its protective effect on erythrocytes damaged by free radical formation induced by pesticides. For this purpose, Falcon tubes were prepared with 100 µL of 2% erythrocyte suspension + 100 µL of phycocyanin at concentrations ranging from 0.05 to 1 mg/mL + 100 µL of each pesticide solution at different concentrations (16 and 18 mg/mL for 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid; 0.2 and 0.3 mg/mL for imidacloprid). The positive control consisted of 100 µL of pesticide at concentrations producing more than 50% hemolysis as an oxidative stress generator + 100 µL of erythrocyte suspension, while the negative control was the erythrocyte suspension without treatment. Samples were incubated in a thermostatic water bath (BIOBASE series, SKU 56202) for 3 hours at 37 °C and 40 rpm, followed by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 252 × g.

Subsequently, 300 µL of the supernatant were transferred into microplate wells [

5]. Each solution was analyzed in triplicate. Finally, the microplate was read on a spectrophotometer at 540 nm to determine the erythroprotective effect of phycocyanin, expressed as the percentage of hemolysis inhibition according to Equation 2.

Equation 2:

Where Aₘ is the absorbance of the treated samples, A₍C+₎ is the absorbance of the positive control, and A₍C–₎ is the absorbance of the negative control [

5].

4.3. In Vitro Digestion of Pesticides and Phycocyanin

In vitro digestion of the pesticides 2,4-D (16 and 18 mg/mL) and imidacloprid (0.2 and 0.3 mg/mL), as well as phycocyanin (1 and 2 mg/mL), was carried out to analyze the bioaccessible fractions (samples available for intestinal absorption) and the bioavailable fractions (samples that cross the intestine and reach circulation), following the methodology of Rodríguez-Roque [

30] with modifications. Samples were exposed to digestive enzymes (amylase, pepsin, and pancreatin). They were first mixed with an α-amylase solution (pH 7, 100 U/mL) for 2 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, the samples were acidified with 6 M HCl to reach pH 2. A portion of 1 mL of pepsin (315 U/mL) (Sigma, P7012-5G) and 1 mL of distilled water were added, and the samples were incubated at 37 °C and 80 rpm for 2 h.

After incubation, the samples were neutralized (pH 7) with 1.25 M NaHCO₃, followed by the addition of 700 µL of pancreatin (4 mg/mL) (Sigma, P1750-100G). The mixtures were homogenized and placed in a water bath with agitation (80 rpm) at 37 °C for 4 h. A dialysis membrane (12,000 kDa, Sigma) was used to separate the bioaccessible fraction (retained inside the membrane) from the bioavailable fraction (that passed through the membrane).

Both fractions were then centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the percentage of hemolysis induced by the pesticides as well as the percentage of hemolysis inhibition by phycocyanin were determined.

4.4. Molecular Docking of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid

4.4.1. Protein Structure Retrieval (β Subunit of Phycocyanin)

A search was performed in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) to obtain the crystallographic structures of the β subunit of phycocyanin. Since separate structures were not available, the complete C-phycocyanin model (Pdb_00001gh0) was downloaded, and the α and β chains were separated using ChimeraX software. The structures were then prepared by removing ligands, ions, and non-essential water molecules. Polar hydrogens were added, and partial charges were assigned. The resulting files were saved in .pdbqt format, compatible with the molecular docking engine.

4.4.2. Ligand Preparation (2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid)

The molecular structures of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid – 2,4-D (CID: 1486) were downloaded from the PubChem database in .SDF format. These files were converted to .pdb format.

4.4.3. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking was carried out using ChimeraX as the interface and AutoDock Vina as the docking engine. A grid box was defined to encompass the protein surface of each subunit separately. Each ligand (2,4-D) was docked individually to the β subunit of phycocyanin. The search parameters were configured to obtain a minimum of nine different poses per compound [

31].

4.4.4. Post-Docking Analysis

After docking, the binding free energy values (in kcal/mol) were analyzed to select the most stable poses. The resulting complexes were then visualized in ChimeraX to identify relevant interactions such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and ionic bonds. The residues involved in each ligand interaction were identified and documented. Three-dimensional images of the complexes were generated, highlighting the most relevant interactions and their positions on the binding surface [

32].

5. Conclusions

Cytotoxicity studies in erythrocytes exposed to 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and imidacloprid demonstrated significant differences among blood types in susceptibility to oxidative damage and membrane destabilization. For 2,4-D, blood type A+ was the most affected, followed by B+ and O+, whereas in the case of imidacloprid, the highest susceptibility was observed in blood type B+, followed by A+ and O+. Phycocyanin exhibited an erythroprotective effect against pesticide-induced oxidative stress even at low concentrations, with efficacy varying by blood type.

In vitro digestion confirmed that the bioaccessible and bioavailable fractions of pesticides retain their ability to induce damage in erythrocytes, while phycocyanin maintained its protective activity across all blood groups. Molecular docking identified interactions of phycocyanin within the polar grooves of the β subunit, suggesting a mechanism of action based on its scavenging capacity.

These findings indicate that phycocyanin has relevant potential as a natural antioxidant agent, with a mechanism of action associated with free radical scavenging, positioning it as a promising alternative to mitigate the cytotoxic effects of pesticides in biological systems.

Author Contributions

J.B.-F.and A.B.-H.: Conceptualization and investigation; C.L.D.-T.-S.: Supervision and project administration; J.M.M.-B.: Writing—review and editing; A.T.B.-M. and A.A.L.-Z.: Methodology; J.R.R.-E.: Software; S.R.-C. and J.J.O.-P.: data curation; O.M.-C.: Formal analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the project CBF2023-2024-3196 from Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975. The work was supported by the clinical laboratory which holds accreditation from ISO-IEC 17025 (NMX-EC-17025) and ISO 15189, as established by the technical committee ISO/TC 212 (Clinical Laboratory Testing and In Vitro Diagnostic Systems), with reference to ISO/IEC 17025 and ISO 9001 standards.

Ethical approval

this study was approved by General Hospital of Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico with the number project CI 2023-47.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper. Therefore, all participants provided their informed consent before participating in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this research are provided within this article. Additional details can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are pleased to acknowledge Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI) for awarding Jesús Martín Muñoz Bautista a master’s scholar- ship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 2,4-D |

Ácido 2,4-diclorofenoxiacético |

| LMR |

Maximum residue limit |

References

- Cárdenas, O., Silva, E., & Ortiz, J. E. (2010). Uso de plaguicidas inhibidores de acetilcolinesterasa en once entidades territoriales de salud en Colombia, 2002-2005. Biomédica, 30(1), 95-106. 10.7705/biomedica.v30i1.157.

- Carvajal Carvajal, C. (2019). Especies reactivas del oxígeno: formación, función y estrés oxidativo. Medicina Legal de Costa Rica, 36(1), 91-100. Especies reactivas del oxígeno: formación, funcion y estrés oxidativo.

- Ruiz-Hernández, Y. A., Garza-Valverde, E., Márquez-Reyes, J. R., & García-Gómez, C. (2023). Extracción de ficocianina para uso como colorante natural: optimización por metodología de superficie de respuesta. Investigación y Desarrollo en Ciencia y Tecnología de Alimentos, 8(1), 84-91. [CrossRef]

- Ortega Freyre, E. G., Gracia, C., Delgadillo Guzmán, D., Intriago Ortega, M. P., Lares Bayona, E. F., & Escorza, Q. (2016). Asociación de la exposición ocupacional a plaguicidas organofosforados con el daño oxidativo y actividad de acetilcolinesterasa. Rev Toxicol, 33(1), 39-43. Redalyc.Asociación de la exposición ocupacional a plaguicidas organofosforados con el daño oxidativo y actividad de acetilcolinesterasa.

- González Vega, Ricardo & Robles, Miguel & Mendoza-Urizabel, Litzy & Cárdenas-Enríquez, Kelly & Ruiz-Cruz, Saúl & Gutiérrez-Lomelí, Melesio & Iturralde García, Rey & Avila-Novoa, María & Villalpando-Vargas, Fridha & Del-Toro-Sánchez, Carmen. (2023). Impact of the Abo and RhD Blood Groups on the Evaluation of the Erythroprotective Potential of Fucoxanthin, β-Carotene, Gallic Acid, Quercetin, and Ascorbic Acid as Therapeutic Agents against Oxidative-Stress.. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudinia, S., Niapour, A., Ghasemi Hamidabadi, H., & Mazani, M. (2019). 2,4-D causes oxidative stress induction and apoptosis in human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs). Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26(25), 26170–26183. [CrossRef]

- Agathokleous, E., Feng, Z. Z., & Peñuelas, J. (2020). Chlorophyll hormesis: Are chlorophylls major components of stress biology in higher plants? Science of The Total Environment, 726, 138637. [CrossRef]

- Crayton, S. M., Wood, P. B., Brown, D. J., Millikin, A. R., McManus, T. J., Simpson, T. J., Ku, K. M., & Park, Y. L. (2020). Bioaccumulation of the pesticide imidacloprid in stream organisms and sublethal effects on salamanders. Global Ecology and Conservation, 24, e01292. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. R., Tzeng, D. T. W., & Yang, E. C. (2021). Chronic effects of imidacloprid on honey bee worker development—molecular pathway perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(21). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., & Lu, S. (2022). Human exposure to neonicotinoids and the associated health risks: A review. Environment International, 163. [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Alfaro, Á. E., Alpízar-Cambronero, V., Duarte-Rodríguez, A. I., Feng-Feng, J., Rosales-Leiva, C., & Mora-Román, J. J. (2020). C-ficocianinas: Modulación del sistema inmune y su posible aplicación como terapia contra el cáncer. Revista Tecnología En Marcha, 33(4), Pág. 125-139. [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Alfaro, Á. E., Alpízar-Cambronero, V., Duarte-Rodríguez, A. I., Feng-Feng, J., Rosales-Leiva, C., & Mora-Román, J. J. (2020). C-ficocianinas: Modulación del sistema inmune y su posible aplicación como terapia contra el cáncer. Revista Tecnología En Marcha, 33(4), Pág. 125-139. [CrossRef]

- Castro-Gerónimo, V. D., García-Rodríguez, R. V., Sánchez-Medina, A., Chamorro-Cevallos, G. A., Sánchez-González, D. J., & Méndez-Bolaina, E. (2023). C-Phycocyanin: A Phycobiliprotein from Spirulina with Metabolic Syndrome and Oxidative Stress Effects. Journal of Medicinal Food, 27(9). [CrossRef]

- Sauerhoff, M. W., Braun, W. H., Blau, G. E., & Gehring, P. J. (1977). The fate of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) following oral administration to man. Toxicology, 8(1), 3–11. [CrossRef]

- Abadin, H., Taylor, J., Buser, M., Scinicariello, F., Przybyla, J., Klotzbach, J. M., Diamond, G. L., Citra, M., Chappell, L. R., & McIlroy, L. A. TOXICOKINETICS, SUSCEPTIBLE POPULATIONS, BIOMARKERS, CHEMICAL INTERACTIONS. (2020). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK590139/.

- Da Silva, A. P., Poquioma Hernández, H. V., Comelli, C. L., Guillén Portugal, M. A., Moreira Delavy, F., de Souza, T. L., de Oliveira, E. C., de Oliveira-Ribeiro, C. A., Silva de Assis, H. C., & de Castilhos Ghisi, N. (2024). Meta-analytical review of antioxidant mechanisms responses in animals exposed to herbicide 2,4-D herbicide. Science of the Total Environment, 924. [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, U., Srivastava, M. K., Bhardwaj, S., & Srivastava, L. P. (2010). Effect of imidacloprid on antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation in female rats to derive its no observed effect level (NOEL). Journal of Toxicological Sciences, 35(4), 577–581. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G. P., Wang, X. Y., Li, J. W., Wang, R., Ren, F. Z., Pang, G. F., & Li, Y. X. (2021). Imidacloprid increases intestinal permeability by disrupting tight junctions. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 222. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, A. R. de J. S., Bizerra, P. F. V., Miranda, C. A., & Mingatto, F. E. (2022). Effects of imidacloprid on viability and increase of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in HepG2 cell line. Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods, 32(3), 204–212. [CrossRef]

- Wei, F., Cheng, F., Li, H., & You, J. (2024). Imidacloprid affects human cells through mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Science of the Total Environment, 951. [CrossRef]

- Minic, S. L., Stanic-Vucinic, D., Mihailovic, J., Krstic, M., Nikolic, M. R., & Cirkovic Velickovic, T. (2016). Digestion by pepsin releases biologically active chromopeptides from C-phycocyanin, a blue-colored biliprotein of microalga Spirulina. Journal of Proteomics, 147, 132–139. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W., Zeng, M., Zhu, S., Li, S., Qian, Y., & Wu, H. (2022). Phycocyanin ameliorates mouse colitis via phycocyanobilin-dependent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory protection of the intestinal epithelial barrier. Food and Function, 13(6), 3294–3307. [CrossRef]

- Bukowska, B., Michałowicz, J., Wojtaszek, A., & Marczak, A. (2011). Comparison of the effect of phenoxyherbicides on human erythrocyte membrane (in vitro). Biologia, 66(2), 379–385. [CrossRef]

- Bukowska, B., Rychlik, B., Krokosz, A., & Michałowicz, J. (2008). Phenoxyherbicides induce production of free radicals in human erythrocytes: Oxidation of dichlorodihydrofluorescine and dihydrorhodamine 123 by 2,4-D-Na and MCPA-Na. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 46(1), 359–367. [CrossRef]

- Tsoraev, G. v., Protasova, E. A., Klimanova, E. A., Ryzhykau, Y. L., Kuklin, A. I., Semenov, Y. S., Ge, B., Li, W., Qin, S., Friedrich, T., Sluchanko, N. N., & Maksimov, E. G. (2022). Anti-Stokes fluorescence excitation reveals conformational mobility of the C-phycocyanin chromophores. Structural Dynamics, 9(5), 054701. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Serrano, M., Pazmiño, D. M., Sparkes, I., Rochetti, A., Hawes, C., Romero-Puertas, M. C., & Sandalio, L. M. (2014). 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid promotes S-nitrosylation and oxidation of actin affecting cytoskeleton and peroxisomal dynamics. Journal of Experimental Botany, 65(17), 4783–4793. [CrossRef]

- Lerro, C. C., Beane Freeman, L. E., Portengen, L., Kang, D., Lee, K., Blair, A., Lynch, C. F., Bakke, B., de Roos, A. J., & Vermeulen, R. C. H. (2017). A longitudinal study of atrazine and 2,4-D exposure and oxidative stress markers among Iowa corn farmers. Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis, 58(1), 30. [CrossRef]

- Martins, R. X., Carvalho, M., Maia, M. E., Flor, B., Souza, T., Rocha, T. L., Félix, L. M., & Farias, D. (2024). 2,4-D Herbicide-Induced Hepatotoxicity: Unveiling Disrupted Liver Functions and Associated Biomarkers. Toxics 2024, Vol. 12, Page 35, 12(1), 35. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Q., Li, L. N., Chang, W. R., Zhang, J. P., Gui, L. L., Guo, B. J., & Liang, D. C. (2001). Structure of C-phycocyanin from Spirulina platensis at 2.2 Å resolution: a novel monoclinic crystal form for phycobiliproteins in phycobilisomes. Urn:Issn:0907-4449, 57(6), 784–792. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Roque, M. J., Del-Toro-sánchez, C. L., Chávez-Ayala, J. M., González-Vega, R. I., Pérez-Pérez, L. M., Sánchez-Chávez, E., Salas-Salazar, N. A., Soto-Parra, J. M., Iturralde-García, R. D., & Flores-Córdova, M. A. (2022). Digestibility, Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Pecan Nutshell (Carya illioinensis) Extracts. Journal of Renewable Materials, 10(10), 2569–2580. [CrossRef]

- Butt, S. S., Badshah, Y., Shabbir, M., & Rafiq, M. (2020). Molecular Docking Using Chimera and Autodock Vina Software for Nonbioinformaticians. JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology, 1(1). [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E. F., Goddard, T. D., Huang, C. C., Meng, E. C., Couch, G. S., Croll, T. I., Morris, J. H., & Ferrin, T. E. (2020). UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Science : A Publication of the Protein Society, 30(1), 70. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Percentage of hemolysis induced by 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid in ABO+ erythrocytes, where asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between blood types. Results were obtained using Triton X as a positive control for 100% hemolysis and unexposed erythrocytes as the negative control for 0%.

Figure 1.

Percentage of hemolysis induced by 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid in ABO+ erythrocytes, where asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between blood types. Results were obtained using Triton X as a positive control for 100% hemolysis and unexposed erythrocytes as the negative control for 0%.

Figure 2.

Percentage of hemolysis induced by 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid in ABO+ erythrocytes, where asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between blood types. Results were obtained using Triton X as a positive control for 100% hemolysis and unexposed erythrocytes as the negative control for 0%.

Figure 2.

Percentage of hemolysis induced by 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid in ABO+ erythrocytes, where asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between blood types. Results were obtained using Triton X as a positive control for 100% hemolysis and unexposed erythrocytes as the negative control for 0%.

Figure 3.

Percentage of hemolysis induced by imidacloprid in ABO+ erythrocytes, where asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between blood types. Results were obtained using Triton X as a positive control for 100% hemolysis and unexposed erythrocytes as the negative control for 0%.

Figure 3.

Percentage of hemolysis induced by imidacloprid in ABO+ erythrocytes, where asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between blood types. Results were obtained using Triton X as a positive control for 100% hemolysis and unexposed erythrocytes as the negative control for 0%.

Figure 5.

Erythroprotective effect of phycocyanin on A+, O+, and B+ erythrocytes exposed to pesticides at selected concentrations of 16 mg/mL for 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 0.2 mg/mL for imidacloprid. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between blood types.

Figure 5.

Erythroprotective effect of phycocyanin on A+, O+, and B+ erythrocytes exposed to pesticides at selected concentrations of 16 mg/mL for 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 0.2 mg/mL for imidacloprid. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between blood types.

Figure 6.

Determination of cytotoxicity of digested fractions of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid at 18 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions. Results were obtained using Triton X as a positive control for 100% hemolysis and unexposed erythrocytes as the negative control for 0%.

Figure 6.

Determination of cytotoxicity of digested fractions of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid at 18 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions. Results were obtained using Triton X as a positive control for 100% hemolysis and unexposed erythrocytes as the negative control for 0%.

Figure 8.

Determination of cytotoxicity of digested fractions of imidacloprid at 0.3 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions. Results were obtained using Triton X as a positive control for 100% hemolysis and unexposed erythrocytes as the negative control for 0%.

Figure 8.

Determination of cytotoxicity of digested fractions of imidacloprid at 0.3 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions. Results were obtained using Triton X as a positive control for 100% hemolysis and unexposed erythrocytes as the negative control for 0%.

Figure 9.

Determination of cytotoxicity of digested fractions of imidacloprid at 0.2 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions. Results were obtained using Triton X as a positive control for 100% hemolysis and unexposed erythrocytes as the negative control for 0%.

Figure 9.

Determination of cytotoxicity of digested fractions of imidacloprid at 0.2 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions. Results were obtained using Triton X as a positive control for 100% hemolysis and unexposed erythrocytes as the negative control for 0%.

Figure 10.

Determination of the erythroprotective effect of digested phycocyanin fractions at 1 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes exposed to 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid at 18 mg/mL. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions.

Figure 10.

Determination of the erythroprotective effect of digested phycocyanin fractions at 1 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes exposed to 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid at 18 mg/mL. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions.

Figure 11.

Determination of the erythroprotective effect of digested phycocyanin fractions at 2 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes exposed to 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid at 16 mg/mL. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions.

Figure 11.

Determination of the erythroprotective effect of digested phycocyanin fractions at 2 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes exposed to 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid at 16 mg/mL. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions.

Figure 12.

Determination of the erythroprotective effect of digested phycocyanin fractions at 1 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes exposed to imidacloprid at 0.3 mg/mL. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions.

Figure 12.

Determination of the erythroprotective effect of digested phycocyanin fractions at 1 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes exposed to imidacloprid at 0.3 mg/mL. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions.

Figure 13.

Determination of the erythroprotective effect of digested phycocyanin fractions at 2 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes exposed to imidacloprid at 0.2 mg/mL. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions.

Figure 13.

Determination of the erythroprotective effect of digested phycocyanin fractions at 2 mg/mL in ABO system erythrocytes exposed to imidacloprid at 0.2 mg/mL. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between digestion fractions.

Figure 14.

Molecular docking of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid with the β subunit of phycocyanin.

Figure 14.

Molecular docking of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid with the β subunit of phycocyanin.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).