Submitted:

10 September 2025

Posted:

11 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Group Therapist

- Empathy: a fundamental trait for any therapist, empathy enables the group therapist to deeply understand and resonate with the emotional experiences of group members. This emotional attunement fosters trust and openness, enhancing the therapeutic alliance within the group (Bohart and Tallman, 2010) [39].

- Active Listening: a skilled therapist engages in active listening, attending to both verbal and non-verbal cues. This skill is essential for ensuring that each member feels understood and for recognizing underlying emotions and unspoken needs, which are crucial for effective interventions (Burlingame et al., 2003) [38].

- Emotional Regulation and Attunement: emotional attunement refers to the therapist’s ability to recognize and appropriately respond to the emotional states of clients. This includes managing one’s own emotions and being sensitive to the emotional atmosphere of the group. Effective emotional regulation allows the therapist to maintain balance and guide the group through challenging moments, helping prevent emotional overwhelm or regression (Yalom and Leszcz, 2008) [36].

- Cultural Sensitivity: in increasingly diverse therapeutic settings, cultural competence is essential. A group therapist must be aware of cultural differences in emotional expression, communication styles, and group dynamics. This sensitivity ensures that all members feel respected and understood, and it helps prevent misinterpretations or conflicts arising from cultural misunderstandings (Sue et al., 2009) [40].

- Flexibility and Adaptability: group therapy involves ever-evolving dynamics, and the therapist must be able to adjust their approach to suit the needs of the group. This adaptability is key in managing shifting group energies, addressing conflict, and responding to different levels of engagement from participants (Yalom and Leszcz, 2008) [36].

- Strong Therapeutic Alliance Skills: the therapist must build and maintain a strong therapeutic alliance with each group member, creating trust, respect, and mutual collaboration. Research has shown that a solid alliance is linked to positive therapy outcomes, as it creates a foundation for vulnerability, feedback, and personal growth (Burlingame et al., 2018, Bohart and Tallman, 2010) [38,39].

- Group Process Knowledge: a profound understanding of group dynamics is critical for effective facilitation. This knowledge allows for the successful resolution of conflicts, the promotion of healthy interactions, and the cultivation of a shared therapeutic purpose (Foulkes, 1948; Holmes and Kivlighan, 2000) [35,41].

- Ethical and Professional Integrity: ethical conduct is essential in maintaining the safety and well-being of group members. A group therapist must be transparent, set clear boundaries, and maintain confidentiality. They also need to possess a strong sense of ethical responsibility, guiding the group with professionalism and accountability (Bacal, 2025) [1].

- Leadership and Facilitation Skills: while the group therapist is not meant to dominate the group, they must take on a leadership role in guiding the group process. This involves structuring sessions, encouraging participation, managing conflicts, and ensuring that the group remains focused on its therapeutic objectives (Yalom and Leszcz, 2008; Tschuschke and Dies, 1994 [36,42].

- Self-Reflection and Ongoing Growth: an effective group therapist is committed to continuous self-reflection and professional development. Examining personal biases, emotional reactions, and their influence on the group process is essential for maintaining a high standard of practice. This commitment to self-awareness and growth allows the therapist to remain open to feedback and refine their therapeutic approach (Christensen et al., 2021) [43].

3. Rationale and Aim

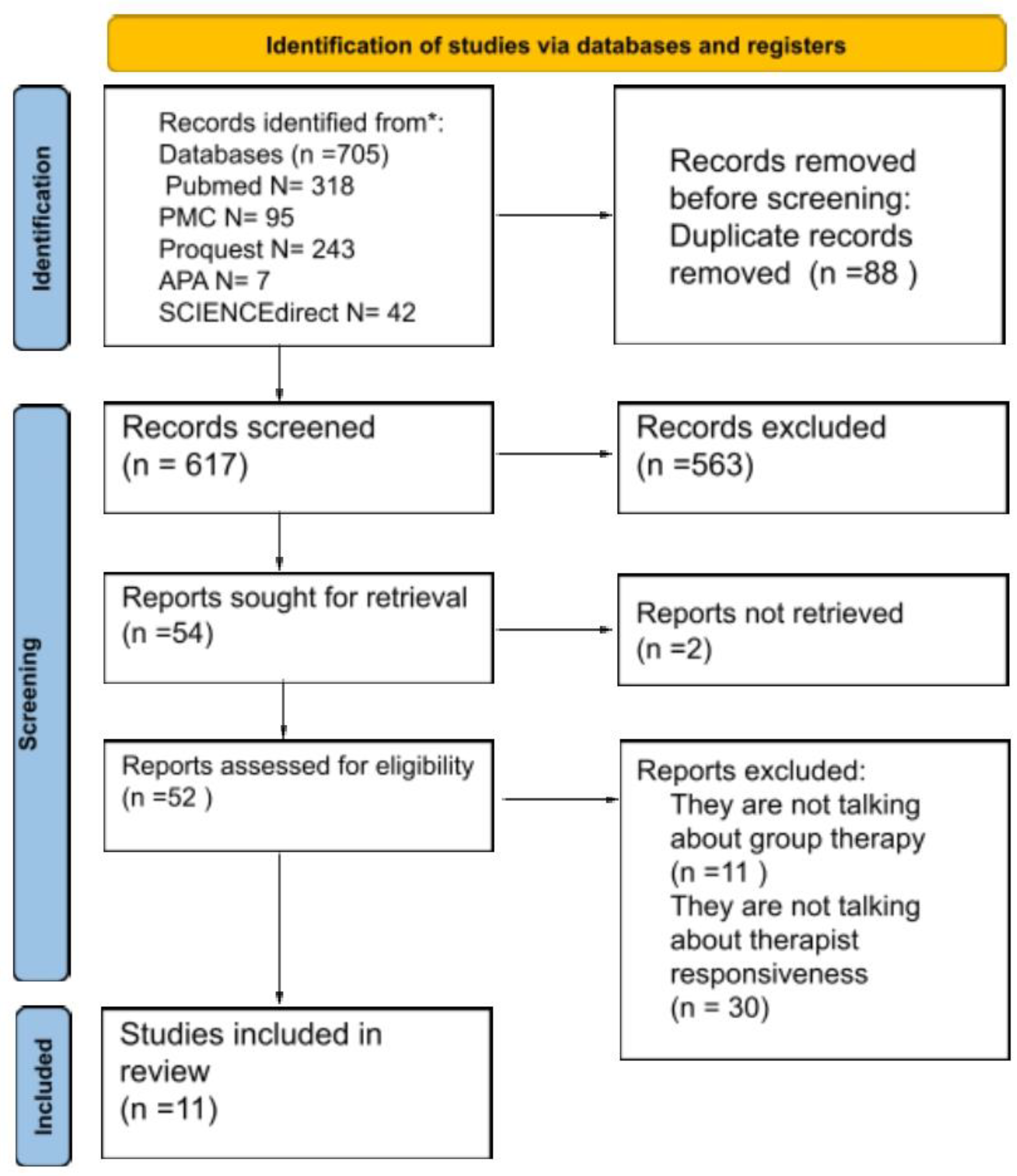

4. Methods

4.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Experimental research

- Full text scientific articles

- Studies on the relationship between therapist responsiveness and group psychotherapy since 2005 (The previous two decades)

- Reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- Abstracts

- Book chapters

4.2. Search

4.3. Selection of Sources of Evidence

5. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. The Here and Now of the Group: An Empathetic Therapist Creates a Welcoming Atmosphere

6.2. Recognizing the Group Member's Specific Experience: Personalization

6.3. Promoting Reflexivity and Mentalization Within the Group

7. Responsiveness in Group Therapists: Common Dynamics Across Different Models

8. Limitations

9. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bacal, H. Optimal Responsiveness and the Therapeutic Process. In Discovering Therapeutic Efficacy; Routledge: London, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, W. B.; Honos-Webb, L.; Surko, M. Responsiveness in Psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 1998, 5, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J. A.; McCracken, J. E.; McClanahan, M. K.; Hill, C. E.; Harp, J. S.; Carozzoni, P. Therapist Perspectives on Countertransference: Qualitative Data in Search of a Theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology 1998, 45, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, U.; Stiles, W. B. The Responsiveness Problem in Psychotherapy: A Review of Proposed Solutions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2015, 22, 277–295. [CrossRef]

- Zuroff, D. C.; Kelly, A. C.; Leybman, M. J.; Blatt, S. J.; Wampold, B. E. Between-therapist and Within-therapist Differences in the Quality of the Therapeutic Relationship: Effects on Maladjustment and Self-critical Perfectionism. J Clin Psychol 2010, 66, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, S. A.; Wampold, B. E.; Imel, Z. E. Untangling the Alliance-Outcome Correlation: Exploring the Relative Importance of Therapist and Patient Variability in the Alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2007, 75, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C. R. Un modo di essere: i più recenti pensieri dell’autore su una concezione di vita centrata-sulla-persona, Rist.; Psycho: Firenze, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, G.; Cuomo, F.; Di Maro, A.; Passeggia, R. The Assessment of Therapist Responsiveness in Psychotherapy Research: A Systematic Review. RES PSYCHOTHER-PSYCH 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, U.; Boehnke, J. R.; Esposito, G. Therapist Responsiveness in Psychotherapy: Introduction to the Special Section. Psychotherapy Research 2025, 35, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culina, I.; Ranjbar, S.; Nadel, I.; Kramer, U. Fluctuations in Therapist Responsiveness Facing Clients with Borderline Personality Disorder: Starting Therapy on the Right Foot. Psychotherapy Research 2025, 35, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellens, H.; Vanhees, V.; Dezutter, J.; Luyten, P.; Vanhooren, S. Therapist Responsiveness in the Blank Landscape of Depression: A Qualitative Study among Psychotherapists. Psychotherapy Research 2025, 35, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo Lobb, M.; Riggio, F.; Guerrera, C. S.; Sciacca, F.; Di Nuovo, S. The Aesthetic Relational Knowing of the Therapist: Factorial Validation of the ARK-T Scale Adapted for the Therapeutic Situation. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology 2024, Vol 12, No 2 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, M.; Ruggieri, R. A.; Fioretti, C.; Tessitore, F.; Girelli, L.; Tinella, L.; Borgese, M. N.; Arcangeli, I. C.; Faggi, D. XXIV National Congress Italian Psychological Association Clinical and Dynamic Section, Salerno, 12nd – 15th September 2024. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology 2024, Vol 12, No 2 Suppl. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J.; Silberschatz, G. The Patient’s Experience of Attunement and Responsiveness Scale. Psychotherapy Research 2017, 27, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Responsive Psychotherapist: Attuning to Clients in the Moment.; Watson, J. C., Wiseman, H., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, A.; Paquin, J. D.; Glean, E.; McQuillan, K.; Hamilton, D. Developing into a Group Therapist: An Empirical Investigation of Expert Group Therapists’ Training Experiences. American Psychologist 2022, 77, 691–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moertl, K.; Giri, H.; Angus, L.; Constantino, M. J. Corrective Experiences of Psychotherapists in Training. J Clin Psychol 2017, 73, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedlander, M. L. Therapist Responsiveness: Mirrored in Supervisor Responsiveness. The Clinical Supervisor 2012, 31, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, A.; Butiu, O. The Family in Romania: Cultural and Economic Context and Implications for Treatment. International Review of Psychiatry 2012, 24, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlinsky, D. E.; Rønnestad, M. H. ; Collaborative Research Network of the Society for Psychotherapy Research. How Psychotherapists Develop: A Study of Therapeutic Work and Professional Growth.; American Psychological Association: Washington, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S. L.; Eaton, A. D.; Leung, V. W. Y.; Iacono, G.; Pang, N.; Dillon, F.; Austin, A.; Pascoe, R.; Dobinson, C. Efficacy of Affirmative Cognitive Behavioural Group Therapy for Sexual and Gender Minority Adolescents and Young Adults in Community Settings in Ontario, Canada. BMC Psychol 2021, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Mehta, M.; Sagar, R. Efficacy of Transdiagnostic Cognitive-Behavioral Group Therapy for Anxiety Disorders and Headache in Adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2017, 46, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coco, G. L.; Gullo, S.; Prestano, C.; Burlingame, G. M. Current Issues on Group Psychotherapy Research: An Overview. In Psychotherapy Research; Gelo, O. C. G., Pritz, A., Rieken, B., Eds.; Springer Vienna: Vienna, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlastelica, M. Group Analytic Psychotherapy (Im)Possibilities to Research. Mental Illness 2011, 3, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuijpers, P.; Van Straten, A.; Warmerdam, L. Are Individual and Group Treatments Equally Effective in the Treatment of Depression in Adults?: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Psychiat. 2008, 22 (1). [CrossRef]

- Blow, A. J.; Karam, E. A. The Therapist’s Role in Effective Marriage and Family Therapy Practice: The Case for Evidence Based Therapists. Adm Policy Ment Health 2017, 44, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Coco, G.; Gullo, S.; Kivlighan, D. M. Examining Patients’ and Other Group Members’ Agreement about Their Alliance to the Group as a Whole and Changes in Patient Symptoms Using Response Surface Analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology 2012, 59, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosendahl, J.; Alldredge, C. T.; Burlingame, G. M.; Strauss, B. Recent Developments in Group Psychotherapy Research. APT 2021, 74, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechtman, Z.; Kiezel, A. Why Do People Prefer Individual Therapy Over Group Therapy? International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 2016, 66, 571–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Andel, P.; Erdman, R. A. M.; Karsdorp, P. A.; Appels, A.; Trijsburg, R. W. Group Cohesion and Working Alliance: Prediction of Treatment Outcome in Cardiac Patients Receiving Cognitive Behavioral Group Psychotherapy. Psychother Psychosom 2003, 72, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, L. The New Member: “Infanticide” in Group Psychotherapy. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 1992, 42, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiman, M.; Stiles, W. B. Dialogical Sequence Analysis and the Zone of Proximal Development as Conceptual Enhancements to the Assimilation Model: The Case of Jan Revisited. Psychotherapy Research 2001, 11, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davì, D.; Prestano, C.; Vegni, N. Exploring Therapeutic Responsiveness: A Comparative Textual Analysis across Different Models. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1412220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullo, S.; Lo Coco, G.; Leszcz, M.; Marmarosh, C. L.; Miles, J. R.; Shechtman, Z.; Weber, R.; Tasca, G. A. Therapists’ Perceptions of Online Group Therapeutic Relationships during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey-Based Study. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 2022, 26, 103–118. [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, S. H. Introduction to Group-Analytic Psychotherapy: Studies in the Social Integration of Individuals and Groups, 1st ed.; Routledge, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Yalom, I. D.; Leszcz, M. The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy; Basic Books: New York, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Burlingame, G. M.; McClendon, D. T.; Alonso, J. Cohesion in Group Therapy. Psychotherapy 2011, 48, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, G. M.; Fuhriman, A.; Mosier, J. The Differential Effectiveness of Group Psychotherapy: A Meta-Analytic Perspective. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 2003, 7, 3–12. [CrossRef]

- Bohart, A. C.; Tallman, K. Psychotherapy. In The heart and soul of change: Delivering what works in therapy, 2nd ed.; Duncan, B. L., Miller, S. D., Wampold, B. E., Hubble, M. A., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, S.; Zane, N.; Nagayama Hall, G. C.; Berger, L. K. The Case for Cultural Competency in Psychotherapeutic Interventions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S. E.; Kivlighan, D. M. Comparison of Therapeutic Factors in Group and Individual Treatment Processes. Journal of Counseling Psychology 2000, 47, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschuschke, V.; Dies, R. R. Intensive Analysis of Therapeutic Factors and Outcome in Long-Term Inpatient Groups. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 1994, 44, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryde Christensen, A.; Wahrén, S.; Reinholt, N.; Poulsen, S.; Hvenegaard, M.; Simonsen, E.; Arnfred, S. “Despite the Differences, We Were All the Same”. Group Cohesion in Diagnosis-Specific and Transdiagnostic CBT Groups for Anxiety and Depression: A Qualitative Study. IJERPH 2021, 18, 5324. [CrossRef]

- Alby, F.; Zucchermaglio, C.; Fatigante, M. Becoming a Psychotherapist: Learning Practices and Identity Construction Across Communities of Practice. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 770749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Sánchez-Bahíllo, Á.; Aragón-Alonso, A.; Sánchez-Bahíllo, M.; Birtle, J. Therapist Characteristics That Predict the Outcome of Multipatient Psychotherapy: Systematic Review of Empirical Studies. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2014, 53, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brabender, V. The Ethical Group Psychotherapist. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 2006, 56, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryde Christensen, A.; Svart, N.; Bokelund, H.; Reinholt, N.; Eskildsen, A.; Poulsen, S.; Hvenegaard, M.; Simonsen, E.; Arnfred, S. Therapists’ Perceptions of Individual Patient Characteristics That May Be Hindering to Group CBT for Anxiety and Depression. Psychiatry 2020, 83, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cella, M.; Reeder, C.; Wykes, T. Group Cognitive Remediation for Schizophrenia: Exploring the Role of Therapist Support and Metacognition. Psychol Psychother 2016, 89, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brusadelli, E.; Ferrari, L.; Benetti, M.; Bruzzese, S.; Tonelli, G. M.; Gullo, S. Online Supportive Group as Social Intervention to Face COVID Lockdown. A Qualitative Study on Psychotherapists, Psychology Trainees and Students, and Community People. ResPsy 2021, 23 (3). [CrossRef]

- Carballeira Carrera, L.; Lévesque-Daniel, S.; Moro, M. R.; Mansouri, M.; Lachal, J. Becoming a Transcultural Psychotherapist: Qualitative Study of the Experience of Professionals in Training in a Transcultural Psychotherapy Group. Transcult Psychiatry 2022, 59, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, L.; Carretier, E.; Moro, M.-R.; Revah-Levy, A.; Sibeoni, J.; Lachal, J. A Qualitative Exploration of What Works for Migrant Adolescents in Transcultural Psychotherapy: Perceptions of Adolescents, Their Parents, and Their Therapists. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J. G.; Coffey, S. F. Group Cognitive Behavioral Treatment for PTSD: Treatment of Motor Vehicle Accident Survivors. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 2005, 12, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E. C.; Kakkad, D.; Balzano, J. Multicultural Competence and Evidence-based Practice in Group Therapy. J Clin Psychol 2008, 64, 1261–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penttinen, H.; Wahlström, J.; Hartikainen, K. Assimilation, Reflexivity, and Therapist Responsiveness in Group Psychotherapy for Social Phobia: A Case Study. Psychotherapy Research 2017, 27, 710–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, L. M.; Austermann, M. I.; Rumpf, H.-J.; Thomasius, R.; Paschke, K. Requirements of a Group Intervention for Adolescents with Internet Gaming Disorder in a Clinical Setting: A Qualitative Interview Study. IJERPH 2021, 18, 7813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tilburg, C. A.; Van Dam, A.; De Wolf-Jacobs, E.; De Ruiter, C.; Smeets, T. Group Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy in a Sample of Dutch Intimate Partner Violence Perpetrators: Development of a Coding Manual for Therapist Interventions. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 2022, 72, 305–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunberg, V. A.; Geller, P. A.; Durham, K.; Bonacquisti, A.; Barkin, J. L. Motherhood and Me (Mom-Me): The Development of an Acceptance-Based Group for Women with Postpartum Mood and Anxiety Symptoms. JCM 2022, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryesten, J. R.; Poulsen, S.; Moltu, C.; Biering, E. B.; Møller, K.; Arnfred, S. M. Patients’ and Therapists’ Experiences of Standardized Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Needs for a Personalized Approach. Adm Policy Ment Health 2024, 51, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, A. S.; Ogrodniczuk, J. S.; Piper, W. E.; Sheptycki, A. R. Interpersonal Predictors of Outcome Following Short-term Group Therapy for Complicated Grief: A Replication. Clin Psychology and Psychoth 2010, 17, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euler, S.; Wrege, J.; Busmann, M.; Lindenmeyer, H. J.; Sollberger, D.; Lang, U. E.; Gaab, J.; Walter, M. Exclusion-Proneness in Borderline Personality Disorder Inpatients Impairs Alliance in Mentalization-Based Group Therapy. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Pujol, E.; Anguera, M. T. A Mixed Methods Framework for Psychoanalytic Group Therapy: From Qualitative Records to a Quantitative Approach Using T-Pattern, Lag Sequential, and Polar Coordinate Analyses. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, M.; Slobodin, O. Identity Development of Arab Drama Therapists: The Role of Ethnic Boundary Work. The Arts in Psychotherapy 2024, 91, 102225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo Lobb, M.; Sciacca, F.; Iacono Isidoro, S.; Di Nuovo, S. The Therapist’s Intuition and Responsiveness: What Makes the Difference between Expert and in Training Gestalt Psychotherapists. EJIHPE 2022, 12, 1842–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarnat, J. Key Competencies of the Psychodynamic Psychotherapist and How to Teach Them in Supervision. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 2010, 47, 20–27. [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H.; Asen, K. Family Therapy without the Family: A Framework for Systemic Practice. Journal of Family Therapy 1992, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, W. L.; Burton, D. L. The Importance of Group Processes in Offender Treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior 2010, 15, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, D. M.; Brossart, D. F. Attachment, Interpersonal Problems, and Treatment Outcome in Group Therapy for Intimate Partner Violence. Psychology of Men & Masculinity 2009, 10, 288–301. [CrossRef]

- Sperandeo, R.; Cioffi, V.; Mosca, L. L.; Longobardi, T.; Moretto, E.; Alfano, Y. M.; Scandurra, C.; Muzii, B.; Cantone, D.; Guerriera, C.; Architravo, M.; Maldonato, N. M. Exploring the Question: “Does Empathy Work in the Same Way in Online and In-Person Therapeutic Settings? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 671790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, H. Online Training Process Groups for Therapists: A Proposed Model. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 2023, 73, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, H. Obstacles, Challenges, and Benefits of Online Group Psychotherapy. APT 2021, 74, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, G. L. Strategy of Outcome Research in Psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting Psychology 1967, 31, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karterud, S. Mentalization-Based Group Therapy (MBT-G): A Theoretical, Clinical, and Research Manual; Oxford University Press, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wei, M.; Kivlighan, D. M.; Koay, E. Y. Y. Unpacking Leader Responsiveness Effects of Emotional Cultivation Groups: Using the Variance Partitioning Method. Journal of Counseling Psychology 2022, 69, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, W. B.; Morrison, L. A.; Haw, S. K.; Harper, H.; Shapiro, D. A.; Firth-Cozens, J. Longitudinal Study of Assimilation in Exploratory Psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 1991, 28, 195–206. [CrossRef]

- Stiles, W. B. Assimilation of Problematic Experiences. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 2001, 38, 462–465. [CrossRef]

- Mental Health and Palestinian Citizens in, Israel; Haj-Yahia, M. M. Mental Health and Palestinian Citizens in Israel; Haj-Yahia, M. M., Nakash, O., Levav, I., Eds.; Indiana University Press, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Rennie, D. L. Humanistic Psychology at York University: Retrospective: Focus on Clients’ Experiencing in Psychotherapy: Emphasis of Radical Reflexivity. The Humanistic Psychologist 2010, 38, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, H.; Butler, M.; Hill, T. What Clients Find Helpful in Psychotherapy: Developing Principles for Facilitating Moment-to-Moment Change. Journal of Counseling Psychology 2006, 53, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metacognition and Severe Adult Mental Disorders: From Research to Treatment; Dimaggio, G., Lysaker, P. H., Eds.; Routledge: London New York, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Rennie, D. L. Reflexivity and Personcentered Counseling. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 2004, 44, 182–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnese, M. L.; Fida, R. Come La Riflessività Promuove l’apertura Delle Organizzazioni Verso l’innovazione: Il Ruolo Delle Pratiche Di Riflessività e Del Clima Di Gruppo per l’innovazione. RISORSA UOMO 2014, No. 1, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrello, S.; Fenizia, E.; Gentile, R.; Iorio, I.; Sartini, C.; Sommantico, M. Supporting Team Reflexivity During the COVID-19 Lockdown: A Qualitative Study of Multi-Vision Groups In-Person and Online. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 719403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Luyten, P.; Allison, E.; Campbell, C. Mentalizing, Epistemic Trust and the Phenomenology of Psychotherapy. Psychopathology 2019, 52, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, H.; Duffy, F.; Duffy, L.; Brown, S.; Hockaday, H.; Eliasson, E.; Graham, J.; Smith, J.; Thomson, A.; Schwannauer, M. Efficacy of Mentalization-Based Group Therapy for Adolescents: The Results of a Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüne, M.; Dimaggio, G.; Edel, M.-A. MENTALIZATION-BASED GROUP THERAPY FOR INPATIENTS WITH BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER: PRELIMINARY FINDINGS.

- Farkas, K.; Csukly, G.; Fonagy, P. Is the Balint Group an Opportunity to Mentalize? Brit J Psychotherapy 2024, 40, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, G.; Wlodek, B.; Arthey, S.; Parker, S. A Systematic Review of Deliberate Practice in Psychotherapy: Definitions, Operationalization, and Preliminary Outcomes. Psychotherapy 2025, 62, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, E. S. K.; Chen, H.; Chui, H.; Luk, S. Perceived Cultural Humility in Supervision Group and Trainees’ Cultural Responsiveness Self-Efficacy. Psychotherapy 2025, 62, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ögren, M.-L.; Jonsson, C.-O.; Sundin, E. C. Group Supervision in Psychotherapy: The Relationship between Focus, Group Climate, and Perceived Attained Skill. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 61, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study ID | Country | Sample Characteristic | Design | Theoretical Model | Group Characteristic | Identified Elements of Therapist’s Responsiveness | Main Finding |

| Beck and Coffey (2005) | USA | N=2 Therapists N=1 Therapist N= 1 Co-Therapist |

Case Study | Cognitive Behavioural | N=1 Group Participants: N=5 women,(ages 33 to 56) with PTSD caused by a Serious motor vehicle accident (12 sessions) |

Case example: “It is critical that the therapists be alert to an individual feeling”(p.10) “Therapists' role in this treatment is conceptualized as that of a coach—someone who has awareness and appreciation for the individual's current struggles yet encourages them to push the boundary slightly”(p.10) |

Therapists take a personalised approach with each patient in the group, creating a welcoming atmosphere |

| Chen et al. (2008) | USA | N= 2 Therapists N=1 30-year-old white woman N=1 40-year-old, Latino, gay male |

Case Illustrations | Cognitive Behavioural | N=2 Groups Participants: Case 1: N=7 three white, one black, two Asian Americans, and one Latina (ages 60 to 75) with Depression Case 2: N=9 servicemen PTSD (ages 21 to 39) (Among the racial minority members in the group are two blacks and one Arab American |

Cases illustrations: Case 1: “Therapist adopts an active style with the group and introduces cognitive restructuring as a way to explore each member s experience with depression” (p.1262) Case 2: “The group therapist as a local clinical scientist deliberately considers, identifies, and implements culturally appropriate interventions, although they may be at variance from RSTs and practice guidelines” (p.1267) |

Therapist pay attention to the specific culture of the patients and their experiences |

| Joyce et al. (2010) | Canada | N= 4 Therapists N=2 women N= 2 men (ages 45 to 62). |

Comparative trial | Psychodynamic | N=18 Groups Participants: N=135 (ages 22 to 74) short-term groups (STG) for Complicated Grief (weekly 90-minutesessions for 12 weeks) |

Case descriptions: “During the sessions, the therapist attempts to create a climate of tolerable tension and deprivation wherein conflicts can be examined using here and-now experience” (p.125) “Therapist’s interpretations might be delivered with more tentativeness and openness to correction by the patient.” (p.133) |

Therapist creating a welcoming atmosphere |

| Penttinen et al. (2017) | Finland | =1 Therapist 50-year-old, male Ph.D, a licensed and experienced psychotherapist |

Case Study | Cognitive Behavioural | N= 2 Groups for Social Phobia Participants: N=17 Case 1: N=10 Case 2: N= 7 (12 weekly two-hour sessions) |

Qualitative analysis of three conversational episodes with one female patient: 1.”Therapist offered a formulation of her problematic experience which was relevant to the intention of her dominant voice, but did not in any way address the feelings” (p.11) 2. “Responded by listening empathically” (ibidem) 3: “Pointed to the significance of the client’s own construction of her problematic experience” (ibidem) |

Therapist's responsive attitude facilitates the patients' assimilation of their experience |

| Euler, et al. (2018) | Switzerland | N=2 Therapists N=1 senior psychiatrist N=1 advanced clinical psychologist (co-therapist) |

Cyberball Task | Psychodynamic | Mentalization-based groups psychotherapy Participants: N=23 patients with Borderline Personality Disorder N= 28 healthy participants three sessions of 75 min per week in their 2nd week after admission to the unit. |

Case Discussion “Even the exclusion-prone patients appeared to be capable of seeing the therapists not as malevolent” (p.7) “Anactive, responsive and reliable therapeutic stance has been described as a hallmark of all empirically supported therapies for BPD” (ibidem) “This fairly “inclusive”– to some extent perhaps even “over-inclusive”– attitude may partially explain why patients did not feel uncomfortable toward the therapists in our study” (p. 8) |

Patients feel welcome within the group that develops mentalization |

| Arias-Pujol and Anguera,(2020) |

Spain | N=2 Therapists N=1 expert lead therapist N=1 co-therapist |

Mixed methods | Psychodynamic | N=1 Group Participants: N= 6 Adolescents (Ages 13 to 15) with learning and interpersonal relationships (30 sessions) |

Clinical vignette: “The lead therapist (T) plays a very active role, encouraging participation so that the adolescents can get to know each other” (p.5) “The lead therapist (T) wants to know their opinions about the experience” (ibidem) |

Therapists facilitate communication and develop mentalization |

| Wendt, et al. (2021) | Germany | N= 2 Therapists,experts women psychological (child and adolescent) |

Qualitative interview | Cognitive Behavioural | N=1 Group Participants: N=7 Adolescents (ages 12-18) with Internet Gaming Disorder (8 modules of 90 min) |

Interviews with therapist: “In addition to knowledge about gaming addiction, being a group therapist also requires you to keep up to date with computer games. (p.14) “To stick strictly to the module is not possible with this topic anyway. [...] It requires a therapist who is also experienced enough to respond flexibly to the needs [of the patients] at that moment.” (p.16) |

Therapists customise the intervention based on their specialist knowledge of psychopathology |

| Van Tilburg et al (2022) | Netherland | N= 18 Therapists N= 10 women N=8 men with 5-10 years of experience |

Qualitative | Cognitive Behavioural | N= 25 Groups Participants: N=133 Men Intimate Partner Violence Perpetrators (60 sessions) |

Audio recording (therapist’s interventions “ Showing interest, enthusiasm and empathy when participants report positive behavior in the context of the treatment objectives, giving recognition, giving compliments, thanking someone for his input, wishing someone positive things, talking about the group atmosphere, putting someone at ease, social small talk.” (p.317) “Encouraging the participants” (p.314) “Using humor, self-deprecation or laughing about a joke the patient has made.” (p.317) |

Therapists show empathy, understanding and exploration of the specific experience and creates a welcoming atmosphere |

| Grunberget al. 2022) | USA | N= 1 Therapist | Case Illustration | Cognitive Behavioural |

N= 1 Group Participants: N= 3-6 women with Postpartum Mood and Anxiety Symptoms ( weekly 50 min group, 7 sessions) |

Case illustration “Therapists are flexible if women need to step out briefly to manage employment or child-related issues”(p.5) “The facilitator encourages” (p.9) |

Therapist creates a welcoming atmosphere and is flexible with patients |

| Gryesten, et al (2024) | Denmark | N = 5 Therapist Women (ages 33 to 54) with 4-10 years of experience | Hermeneutic-phenomenological thematic analysis | Cognitive Behavioural | N= 3 Group Participants: N=15 N=11 Women N= 4 Men with depression and comorbid diagnoses Routine Outcome Monitoring (ROM) (14 two-hour weekly sessions) |

Interviews with patients: “Five themes were identified: (1) Individual attention (2) Psychological exploration (3) A focus on the patient’s life outside of therapy (4) Extended assessment (5) Agreement on therapeutic task” (p.617) |

Therapists respond to the specific needs of their patients, exploring their unique experiences |

| Jaber and Slobodin, (2024) | Israel | N=38 Psychotherapists N= 36 women N= 2 Men (ages 30-58 years), with 7.42 average years of professional experience N=28 Muslim-Arab N= 6 Druze N= Christian-Arab |

Qualitative | Art therapy | Groups of Art-therapy in schools in the Northern District of Israel for Children and Adolescents | Semi-structured Interviews : “Three themes were identified: (1) Distinguishing Arab identity from drama therapy (2) Drama therapy is perceived as an act of challenging ethnic and gender boundaries (3) Negotiating ethnic boundaries within the context of drama therapy” (p.3) |

Therapists pay specific attention to their own culture, recognising its influence on their practice |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).