Submitted:

10 September 2025

Posted:

11 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

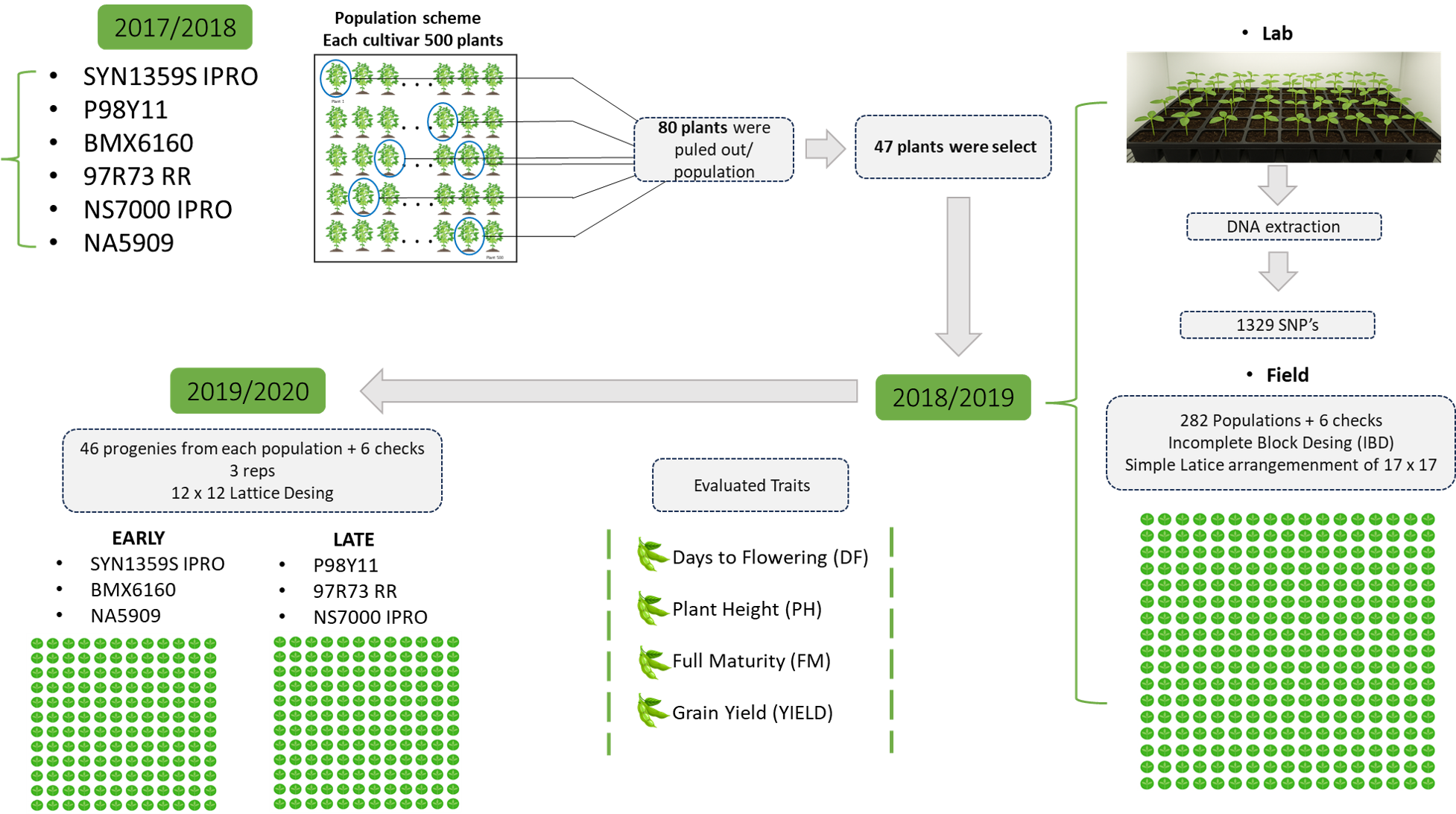

2.1. Plant Material and Field Trials

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Phenotypic Data analysis

2.4. DNA Extraction, Library Preparation, and Sequencing

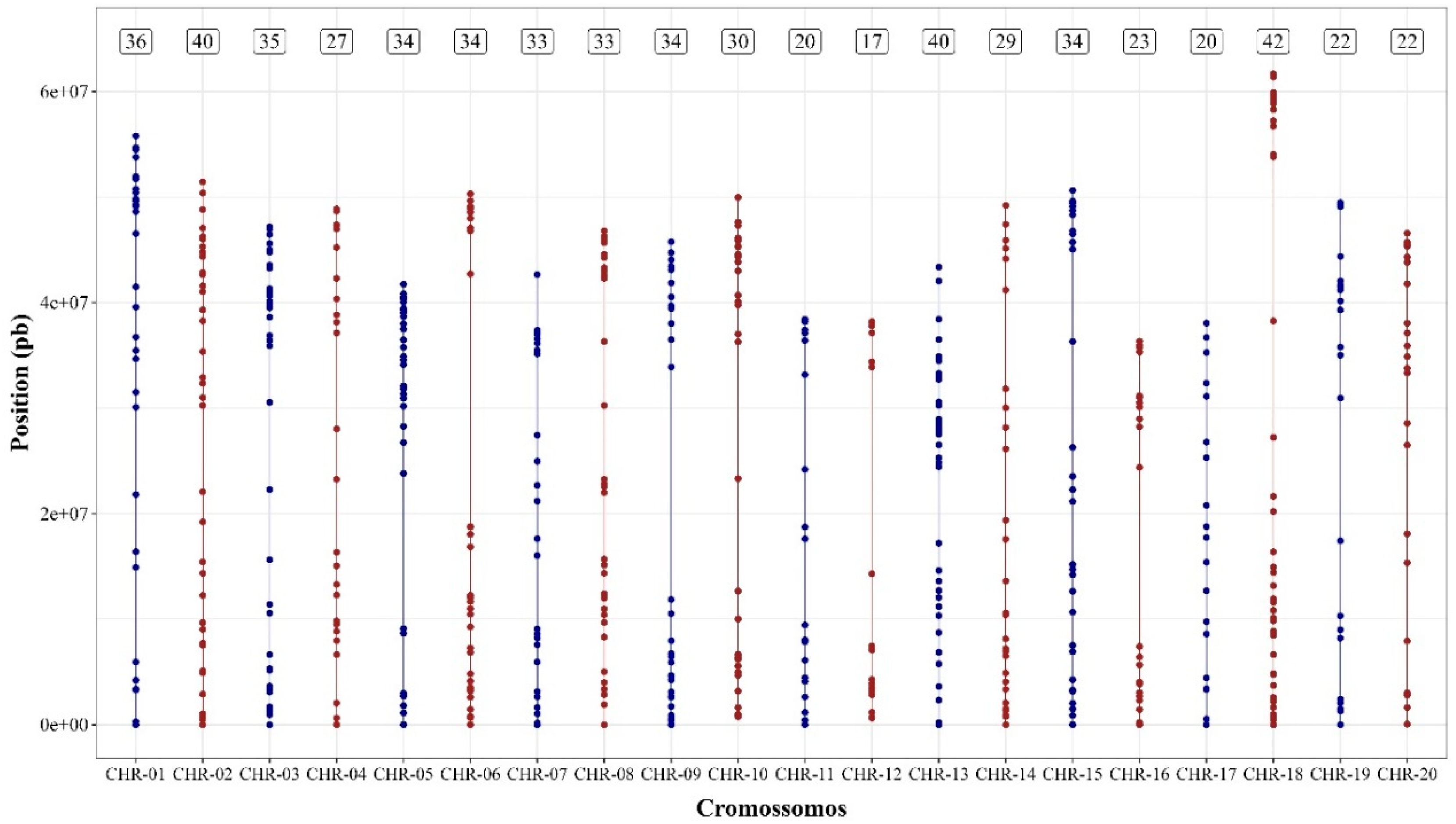

2.5. Selection, Imputation, and Coverage of SNPs

2.6. Population Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic Data

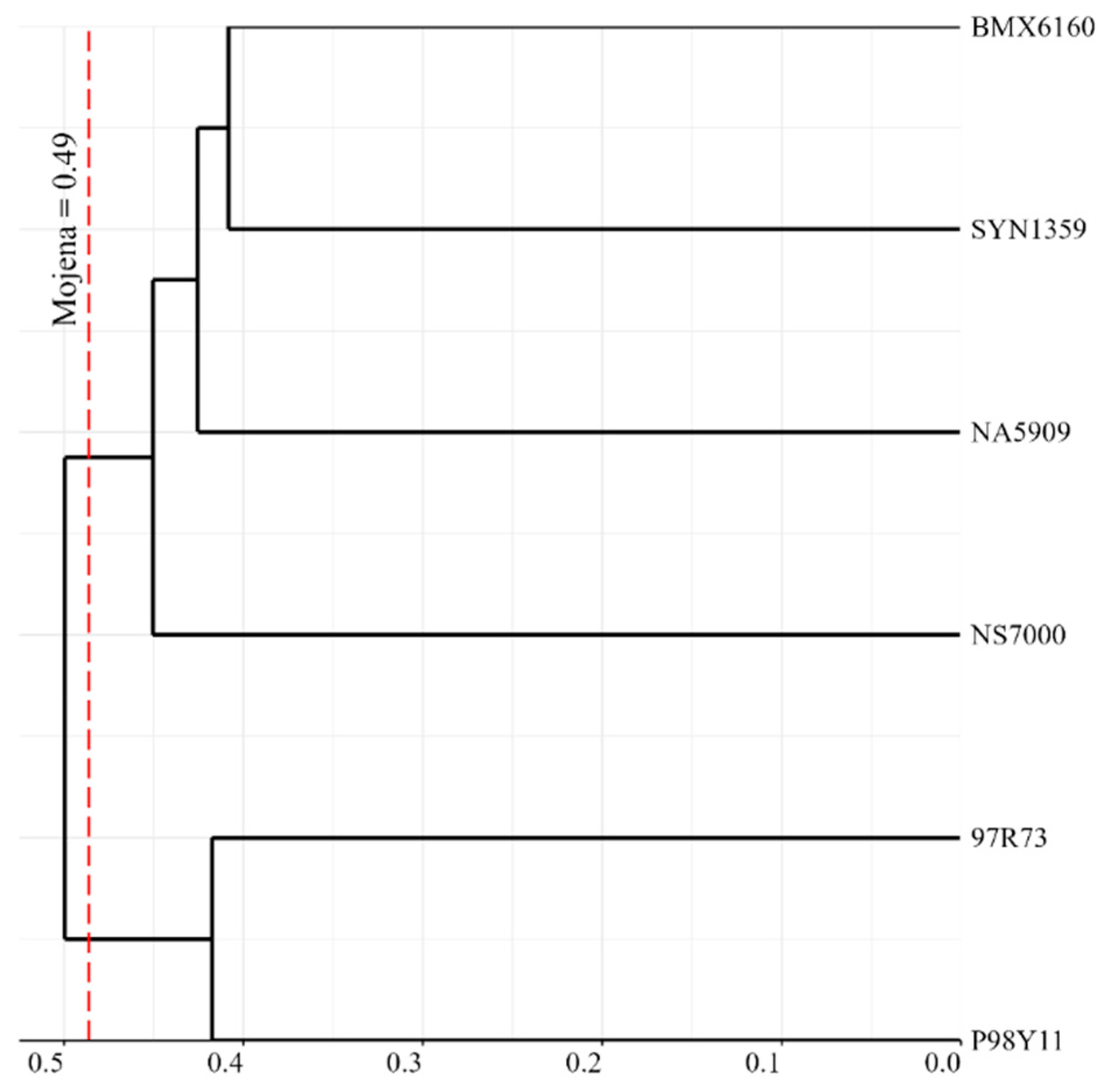

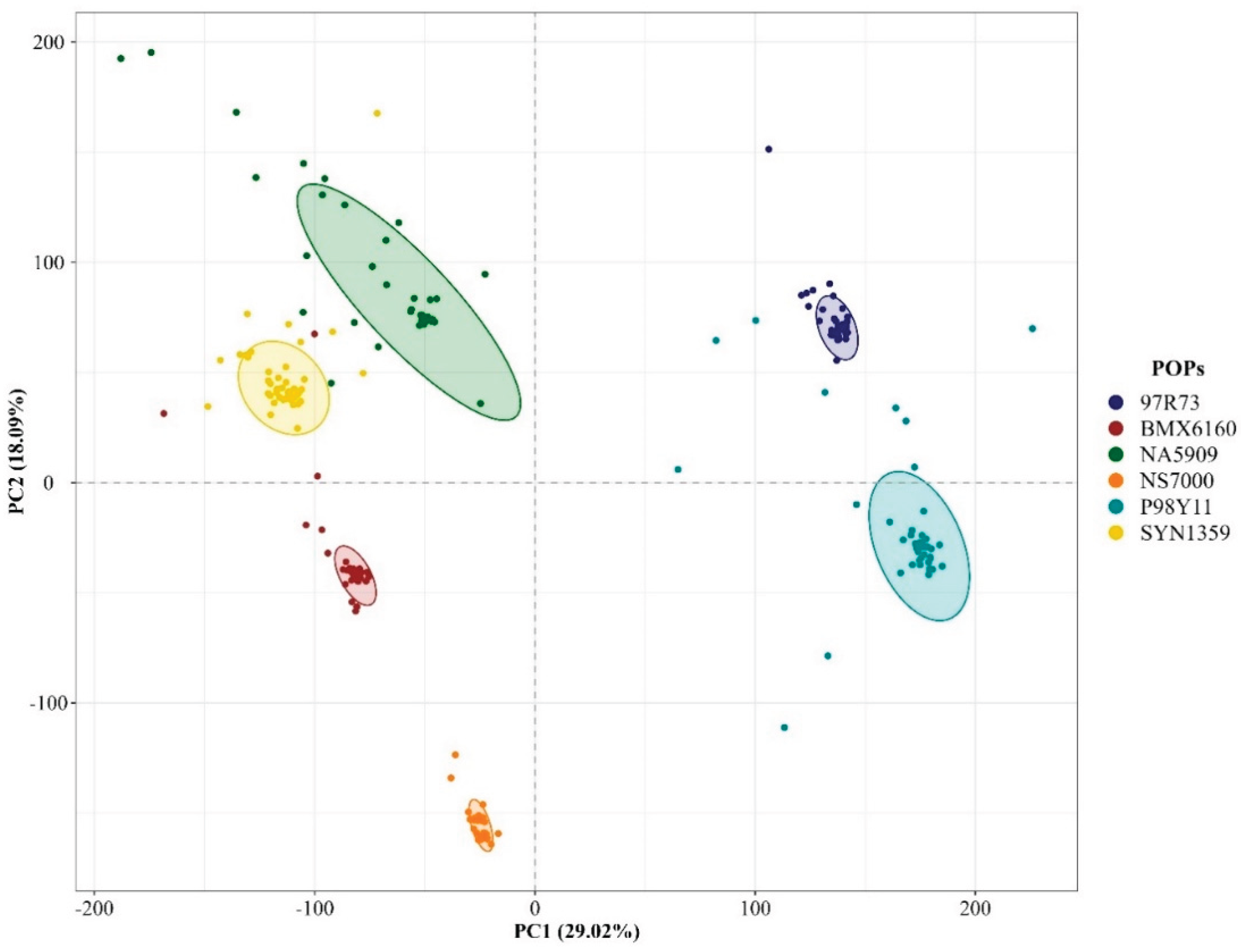

3.2. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure

4. Discussion

4.1. Phenotypic Data

4.2. Molecular Data

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reynolds, M.P.; Braun, H.-J. (Eds.). Wheat Improvement: Food Security in a Changing Climate; Springer: Cham, Switzerland 2022. [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.S.J.; Abreu, A.F.B.; Ramalho, M.A.P. Seleção de linhas puras no feijão ‘carioca’. Ciência e Agrotecnologia 2002, 20, 1492–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Agorastos, A.G.; Goulas, C.K. Line selection for exploiting durum wheat (T. turgidum L. var. durum) local landraces in modern variety development program. Euphytica 2005, 146, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, L. de O.; et al. Pure line selection in a heterogeneous soybean cultivar. Crop Breeding and Applied Biotechnology. 2019, 19, 277–284.

- Roy, P.S.; Patnaik, A.; Rao, G.J.N.; Patnaik, S.S.C.; Chaudhury, S.S.; Sharma, S.G. Participatory and molecular marker assisted pure line selection for refinement of three premium rice landraces of Koraput, India. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 2016, 41, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokatlidis, I.S. Conservation breeding of elite cultivars. Crop Science 2015, 55, 2417–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achard, F.; et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms facilitate distinctness-uniformity-stability testing of soybean cultivars for plant variety protection. Crop Science 2020, 60, 2280–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, H.O.J.B. The maximum F-ratio as a short-cut test for heterogeneity of variance. Biometrika 1950, 37, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Money, D.; et al. LinkImpute: Fast and accurate genotype imputation for nonmodel organisms. G3: Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2015, 5, 2383–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevosti, A.; Ocaña, J.; Alonso, G. Distances between populations of Drosophila subobscura, based on chromosome arrangements frequencies. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 1975, 45, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasoula, V.A.; Boerma, H.R. Divergent selection at ultra-low plant density for seed protein and oil content within soybean cultivars. Field Crops Research 2005, 91, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, E. Analysis of Phylogenetics and Evolution with R, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marand, A.P.; et al. Residual heterozygosity and epistatic interactions underlie the complex genetic architecture of yield in diploid potato. Genetics 2019, 212, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninou, E.; et al. Utilization of intra-cultivar variation for grain yield and protein content within durum wheat cultivars. Agriculture 2022, 12, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokatlidis, I.S.; et al. Variability within cotton cultivars for yield, fiber quality and physiological traits. The Journal of Agricultural Science 2008, 146, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, L.F.; et al. Genomic prediction enables early but low-intensity selection in soybean segregating progenies. Crop Science 2020, 60, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, G.; Miller, M.J.; Steketee, C.J.; Jackson, S.A.; Tunes, L.V.M. de; Li, Z. Genetic control and allele variation among soybean maturity groups 000 through IX. The Plant Genome 2021, 14, e20146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayade, R.; Imran, M.; Ghimire, A.; Khan, W.; Nabi, R.B.S.; Kim, Y. Molecular, genetic, and genomic basis of seed size and yield characteristics in soybean. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1195210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falconer, D.S.; Mackay, T.F.C. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics, 4th ed.; Addison Wesley Longman: Harlow, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro, A.K.; et al. Stability analysis of pure lines and a multiline of soybean in different locations. Crop Breeding and Applied Biotechnology 2019, 19, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, N.J.D.; et al. Multiline is a strategy for homeostasis and Asian soybean rust management in agriculture. Genetics and Molecular Research 2024, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, J.L.; et al. SSR-marker analysis of the intracultivar phenotypic variation discovered within 3 soybean cultivars. Journal of Heredity 2012, 103, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihelich, N.T.; Mulkey, S.E.; Stec, A.O.; Stupar, R.M. Characterization of genetic heterogeneity within accessions in the USDA soybean germplasm collection. The Plant Genome 2020, 13, e20000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haun, W.J.; et al. The composition and origins of genomic variation among individuals of the soybean reference cultivar Williams 82. Plant Physiology 2011, 155, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, H.C.; et al. Genetic diversity and selection footprints in the genome of Brazilian soybean cultivars. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 842571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; et al. High genetic diversity and low population differentiation of a medical plant Ficus hirta Vahl. , uncovered by microsatellite loci: Implications for conservation and breeding. BMC Plant Biology 2022, 22, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockett, E.A.; Eslick, R.F.; Qualset, C.O.; et al. Effects of natural selection in advanced generations of barley composite cross II. Crop Science 1983, 23, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgante, M.; et al. Gene duplication and exon shuffling by helitron-like transposons generate intraspecies diversity in maize. Nature Genetics 2005, 37, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgotra, R.K.; Chauhan, B.S. Genetic diversity, conservation, and utilization of plant genetic resources. Genes 2023, 14, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, D.; et al. The endogenous transposable element Tgm9 is suitable for generating knockout mutants for functional analyses of soybean genes and genetic improvement in soybean. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmusson, D.C.; Phillips, R.L. Plant breeding progress and genetic diversity from de novo variation and elevated epistasis. Crop Science 1997, 37, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SV | Effect | YIELD | PH | FM | DF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | ns | ns | ** | ** | |

| R | ** | ** | ** | ns | |

| R | ** | ** | ** | ** | |

| R | ** | ** | ** | ** | |

| R | ** | ns | ** | ** | |

| R | ns | ** | ** | ** | |

| R | ns | ** | ** | ** | |

| R | ** | ** | ** | ** | |

| R | ** | ** | ** | ** | |

| R | ** | ** | ** | ** | |

| R | ns | ** | ** | ** | |

| R | ns | ns | ** | ** | |

| R | ** | ns | ** | ** | |

| - | 4655.08 | 76.44 | 115.13 | 45.19 | |

| - | 0.17 | 0.86 | 0.12 | 0.48 | |

| - | 0.18 | 0.96 | 0.86 | 0.96 | |

| - | 0.30 | 0.99 | 0.88 | 0.98 | |

| - | 0.41 | 0.93 | 0.35 | 0.69 | |

| - | 0.39 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.98 | |

| - | 0.55 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.99 | |

| (%) | - | 3.49 | 3.42 | 0.36 | 0.92 |

| (%) | - | 3.58 | 18.43 | 2.53 | 6.67 |

| (%) | - | 16.61 | 8.67 | 2.11 | 3.74 |

| Population | He | Ho |

|---|---|---|

| SYN1359 | 0.0929 | 0.0700 |

| P98Y11 | 0.1245 | 0.1125 |

| BMX6160 | 0.0483 | 0.0360 |

| 97R73 | 0.0702 | 0.0477 |

| NS7000 | 0.0478 | 0.0321 |

| NA5909 | 0.0952 | 0.0897 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).