Submitted:

10 September 2025

Posted:

11 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Proximal Chemical Analysis in Food

2.2. Determination of Chitin in Food

2.3. Amino Acid Profile in Food

2.4. Extraction of Lipids in Food

2.5. Determination of Fatty Acids in Food

2.6. Determination of Cholesterol and Triglycerides in Food

2.7. Resistant Starch in Food

2.8. Determination of Total Polyphenols in Food

2.9. Determination of Antioxidant Activity in Food

2.10. Animal Study Design

2.11. Energy expenditure

2.12. Body Composition

2.13. Determination of the Glucose Tolerance Curve (GTC)page

2.14. Biochemical Parameters

2.15. Histological Analysis

2.16. Western Blot Analysis

2.17. TMAO Determination

2.18. 16S rRNA Sequencing

2.19. Statistical Analysis

2.20. Bioinformatic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Nutritional Profile of Different Source of Proteins

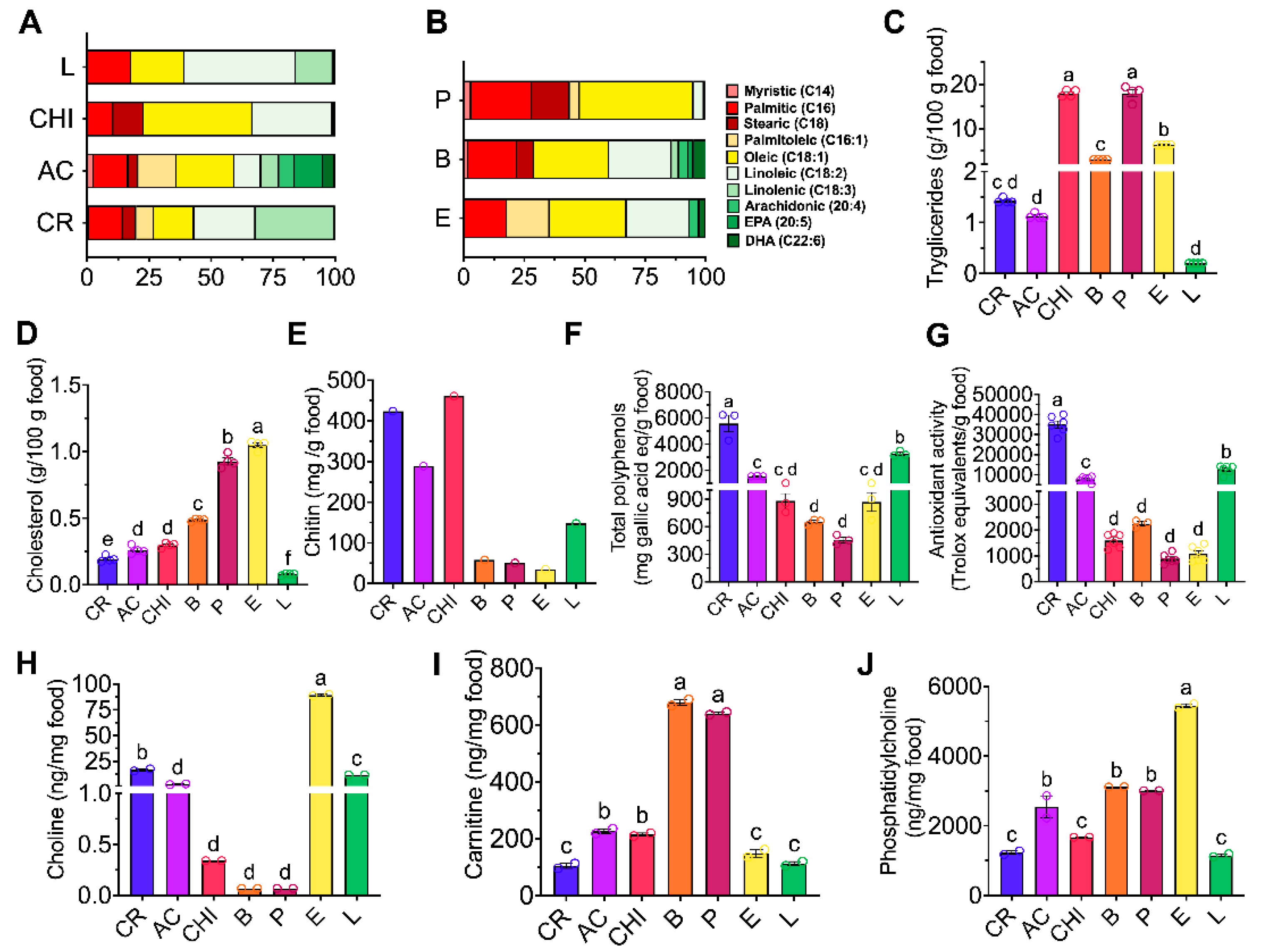

3.2. Fatty Acid Profile in Different Source of Proteins

3.3. Cholesterol and Triglycerides Concentration in Different Sources of Dietary Protein

3.4. Chitin Concentrations in Different Source of Proteins

3.5. Total Polyphenols and Antioxidant Activity in Different Source of Proteins

3.6. Choline, Carnitine and Phosphatidylcholine Concentrations in Different source of Protein

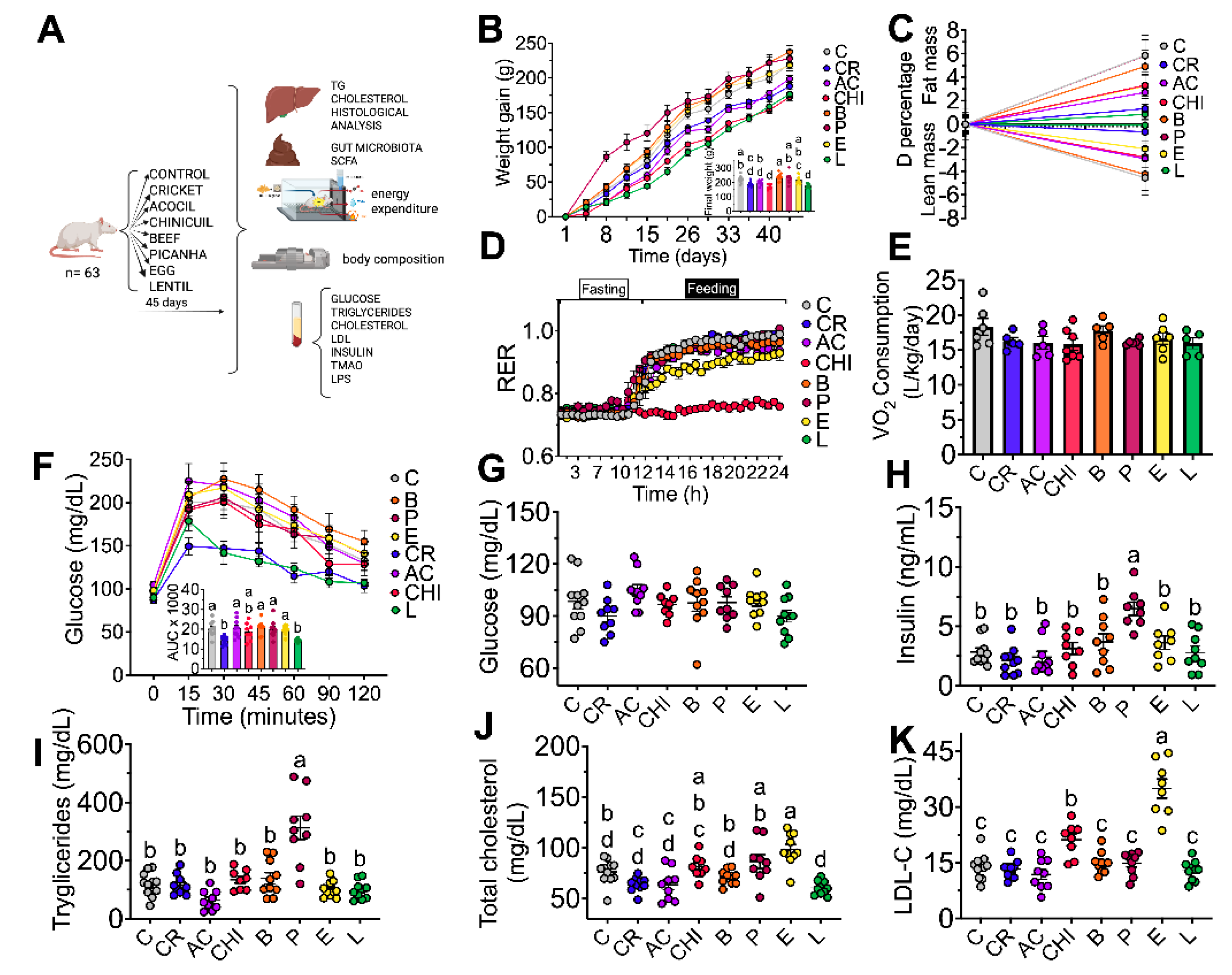

3.7 Effect of Different Sources of Protein on Weight Gain and Body Composition

3.8. Effect of Different Sources of Protein on Energy Expenditure

3.9. Effect of Different Sources of Protein on Glucose Tolerance and Biochemical Parameters

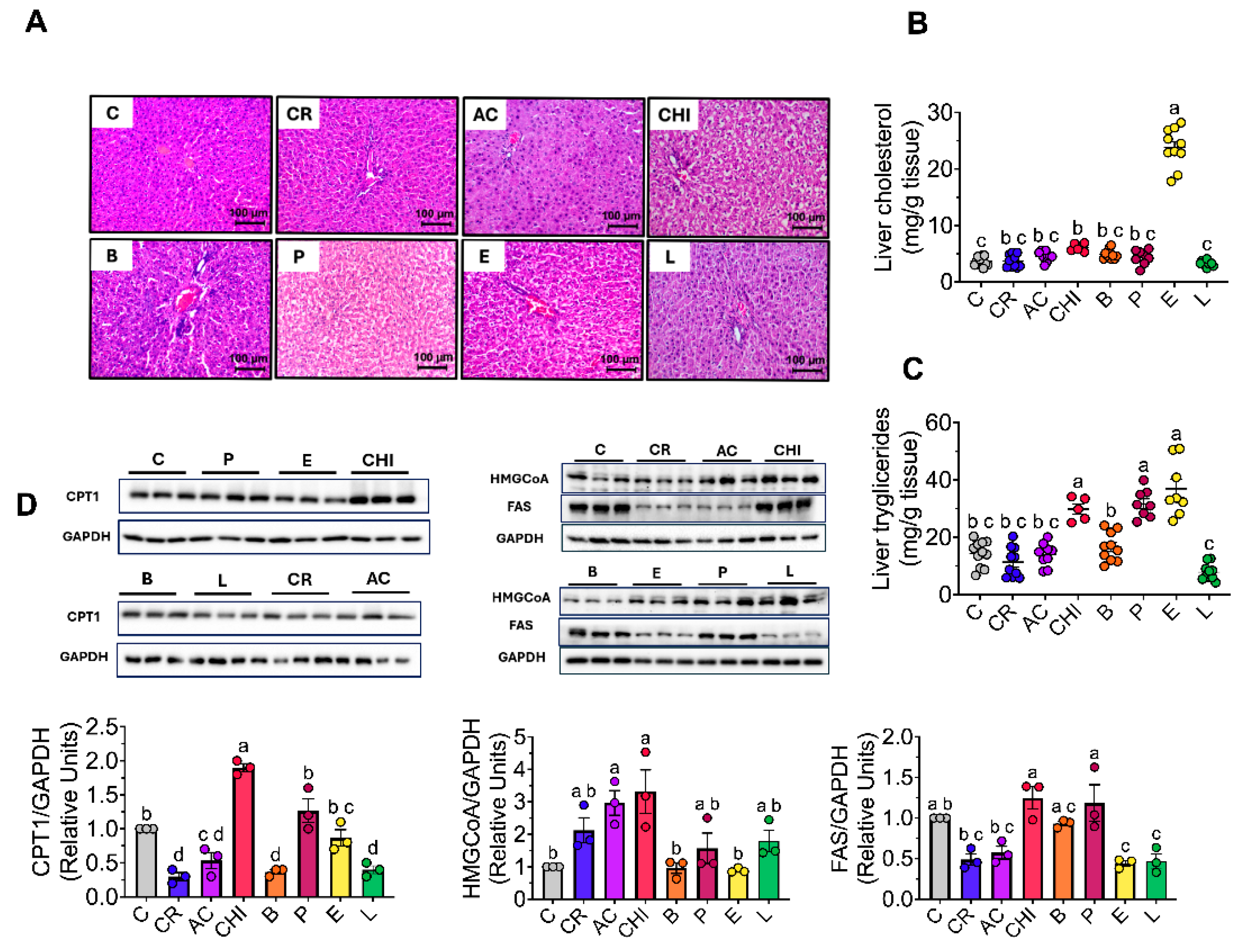

3.10. Effect of Different Food Sources of Protein on Liver Morphology and Liver Triglycerides and Cholesterol

3.11. Consumption of Different Food Sources of Protein on Hepatic Lipogenesis and Beta Oxidation

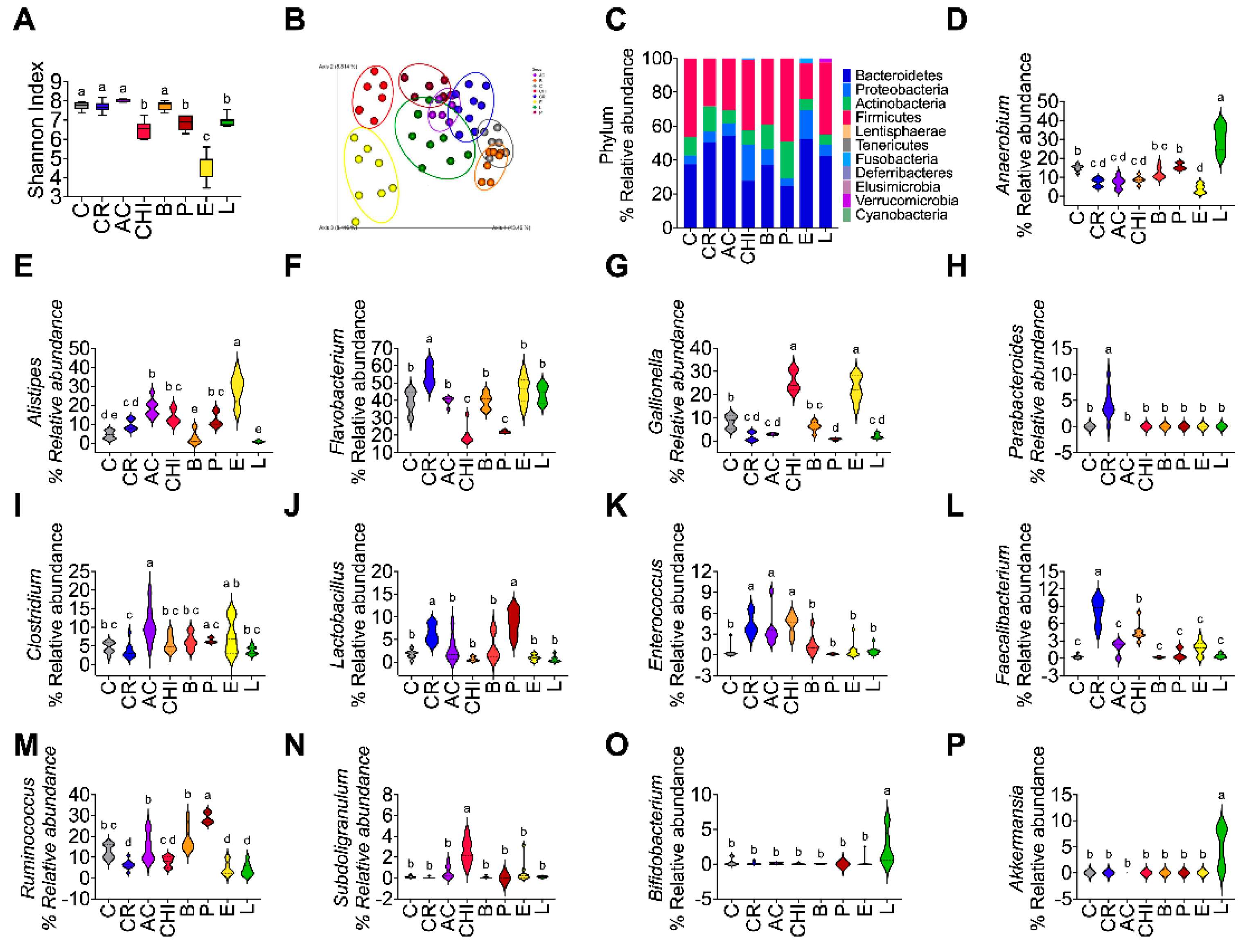

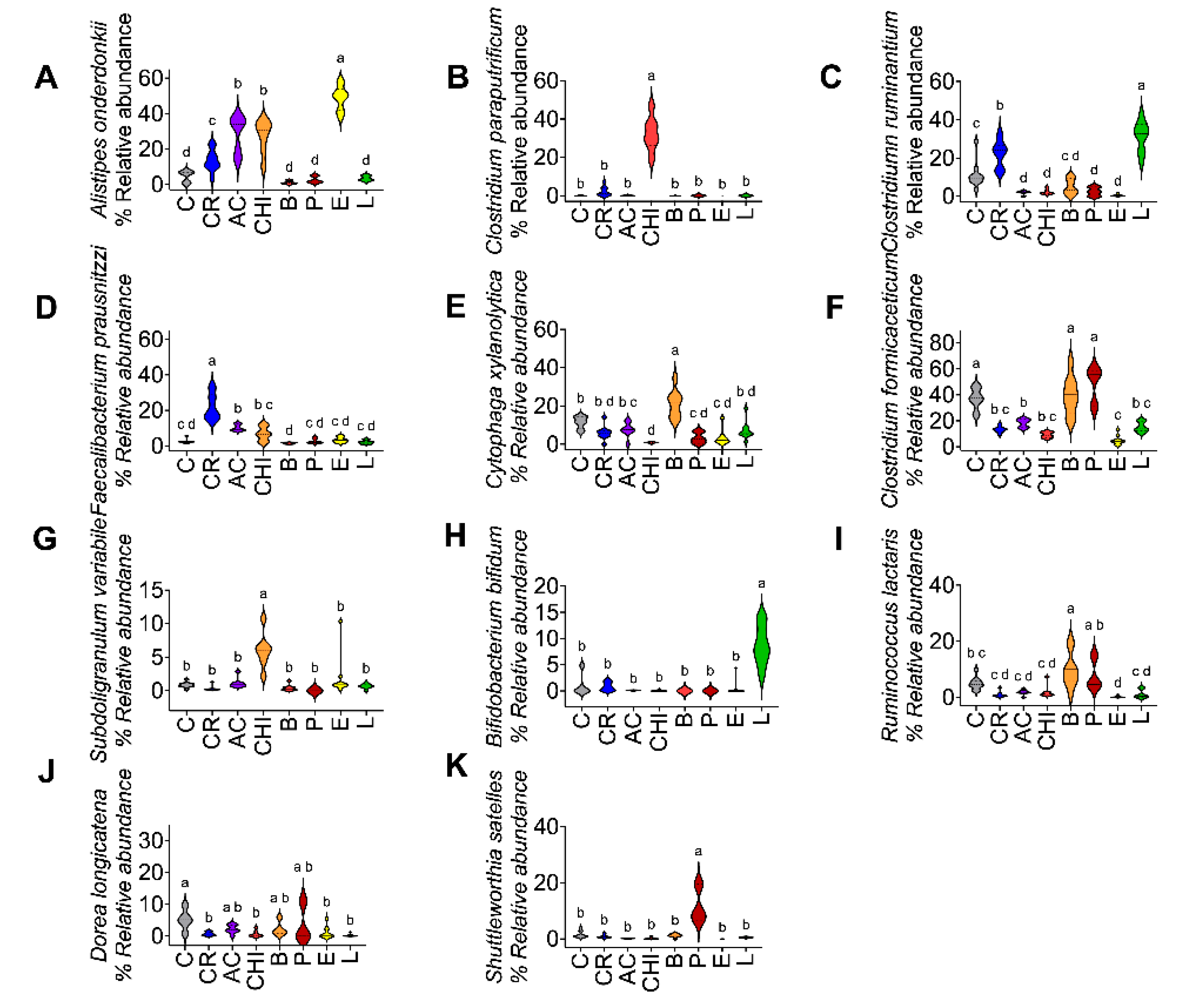

3.12. Effect of Different Sources of Protein on Gut Microbiota

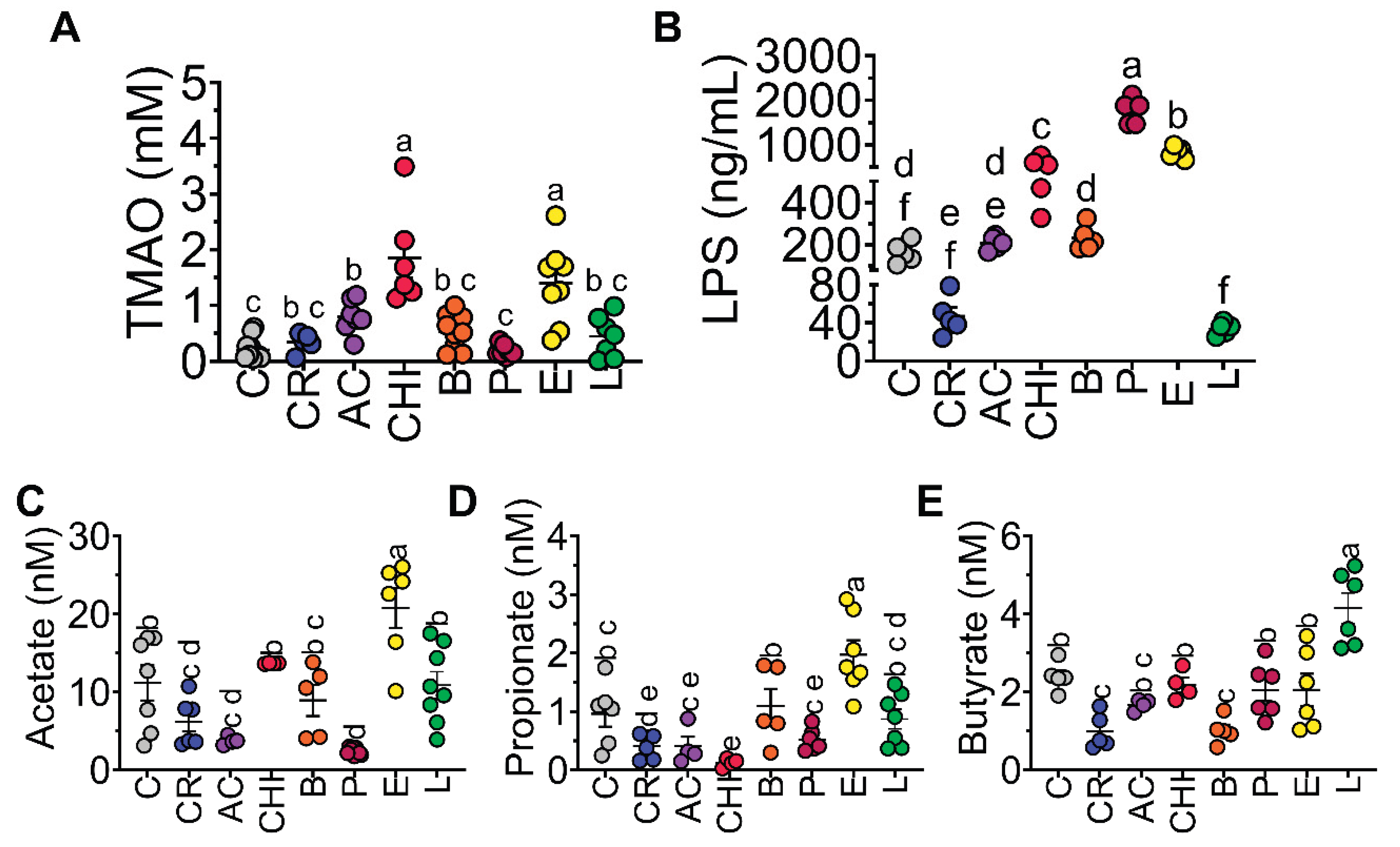

3.13. Effect of Different Source of Protein on Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| C | Control |

| CR | Cricket |

| L | Lentil |

| AC | Acocil |

| CHI | Chinicuil |

| E | Egg |

| B | Beef |

| P | Picanha |

References

- FAO, F. , OMS, PMA, UNICEF. El estado de la seguridad alimentaria y la nutrición en el mundo; 2017; pp 1-144.

- Huis, A.; Itterbeeck, J.; Klunder, H.; Mertens, E.; Halloran, A.; Muir, G.; Vantonne, P. Edible insects: Future prospects for food and feed security. In Forestry paper, FAO, Ed. FAO: Rome, 2013; Vol. 171, pp. 1-187.

- Sranacharoenpong, K.; Soret, S.; Harwatt, H.; Wien, M.; Sabate, J. The environmental cost of protein food choices. Public Health Nutr 2015, 18, 2067–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakadevan, K.; Nguyen, M.L. Lifestock production and its impact on nutrient. pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. In Advances in Agronomy, ELSEVIER: Newark, USA, 2017; Vol. 141, pp. 147-184.

- de Vries, M.; de Boer, I.J.M. Comparing environmental impacts for livestock products: A review of life cycle assessments. In Livestock Science, 2010; Vol. 128, pp 1-11.

- Vinci, G.; Prencipe, S.A.; Masiello, L.; Zaki, M.G. The Application of Life Cycle Assessment to Evaluate the Environmental Impacts of Edible Insects as a Protein Source. Earth (Switzerland) 2022, 3, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imatiu, S. Benefits and food safety concerns associated with consumption of edible insects. NFS Journal 2019, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Elorduy, J. La etnoentomologia en la alimentación, la medicina y recicleje. In Biodiversidad, Taxonomia y Biogeogafia de artropodos de México, Ciencias, F.d., Ed. México, 2004; pp. 329-413.

- Abril, S.; Pinzón, M.; Hernández-Carrión, M.; Sánchez-Camargo, A.d.P. Edible Insects in Latin America: A Sustainable Alternative for Our Food Security. In Frontiers in Nutrition, Frontiers Media S.A.: 2022; Vol. 9.

- Krongdang, S.; Phokasem, P.; Venkatachalam, K.; Charoenphun, N. Edible Insects in Thailand: An Overview of Status, Properties, Processing, and Utilization in the Food Industry. In Foods, MDPI: 2023; Vol. 12.

- Matandirotya, N.R.; Filho, W.L.; Mahed, G.; Maseko, B.; Murandu, C.V. Edible Insects Consumption in Africa towards Environmental Health and Sustainable Food Systems: A Bibliometric Study. In International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, MDPI: 2022; Vol. 19.

- Raheem, D.; Carrascosa, C.; Oluwole, O.B.; Nieuwland, M.; Saraiva, A.; Millán, R.; Raposo, A. Traditional consumption of and rearing edible insects in Africa, Asia and Europe. In Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, Taylor and Francis Inc.: 2019; Vol. 59, pp 2169-2188.

- Kjeldahl, J. A new method for the determination of nirogen in organic matter. Zeitschrift für Analytische Chemie 1883, 22, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezegbe, C.C.; Nwosu, J.N.; Owuamanam, C.I.; Victor-Aduloju, T.A.; Nkhata, S.G. Proximate composition and anti-nutritional factors in Mucuna pruriens (velvet bean) seed flour as affected by several processing methods. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badawy, M.E. A New Rapid and Sensitive SpectrophotometricMethod for Determination of a Biopolymer Chitosan. International Journal of Carbohydrate Chemistry 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Sloane Stanley, G.H. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, H.A.; Dohm, G.L.; Loesche, P.; Tapscott, E.B.; Smith, C. Lipid content and fatty acid composition of heart and muscle of the BIO 82. 62 cardiomyopathic hamster. Lipids 1976, 11, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhaes, L.M.; Santos, F.; Segundo, M.A.; Reis, S.; Lima, J.L. Rapid microplate high-throughput methodology for assessment of Folin-Ciocalteu reducing capacity. Talanta 2010, 83, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, B.; Hampsch-Woodill, M.; Flanagan, J.; Deemer, E.K.; Prior, R.L.; Huang, D. Novel fluorometric assay for hydroxyl radical prevention capacity using fluorescein as the probe. J Agric Food Chem 2002, 50, 2772–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, P.G. Components of the AIN-93 diets as improvements in the AIN-76A diet. J Nutr 1997, 127, 838S–841S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joint, W.H.O.F.A.O.U.N.U.E.C. Protein and amino acid requirements in human nutrition. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2007, 1-265, back cover.

- Alexandratos, N.; Bruinsma, J. World agriculture towards 2030/2050; Rome, 2012; pp 1-155.

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing food's environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Sustainability, Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siva, N.; Johnson, C.R.; Richard, V.; Jesch, E.D.; Whiteside, W.; Abood, A.A.; Thavarajah, P.; Duckett, S.; Thavarajah, D. Lentil ( Lens culinaris Medikus) Diet Affects the Gut Microbiome and Obesity Markers in Rat. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 8805–8813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insect | Definition, Characteristics, Types, Beneficial, Pest, Classification, & Facts | Britannica.

- Izadi, H.; Asadi, H.; Bemani, M. Chitin: A comparison between its main sources. Frontiers in Materials 2025, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyrinck, A.M.; Possemiers, S.; Verstraete, W.; De Backer, F.; Cani, P.D.; Delzenne, N.M. Dietary modulation of clostridial cluster XIVa gut bacteria (Roseburia spp.) by chitin-glucan fiber improves host metabolic alterations induced by high-fat diet in mice. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2012, 23, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Gregory, J.C.; Org, E.; Buffa, J.A.; Gupta, N.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Mehrabian, M. , et al. Gut Microbial Metabolite TMAO Enhances Platelet Hyperreactivity and Thrombosis Risk. Cell 2016, 165, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, C.E.; Aardema, N.D.J.; Bunnell, M.L.; Larson, D.P.; Aguilar, S.S.; Bergeson, J.R.; Malysheva, O.V.; Caudill, M.A.; Lefevre, M. Effect of Choline Forms and Gut Microbiota Composition on Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Response in Healthy Men. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Chemical composition (g/100g food) | Cricket | Acocil | Chinicuil | Beef | Picanha | Egg | Lentil |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | 51.84 | 43.3 | 28.7 | 75.0 | 57.1 | 50.6 | 25.3 |

| Lipids | 6.73 | 4.54 | 63.0 | 2.97 | 21.0 | 30.3 | 0.63 |

| Carbohydrates | 4.84 | 2.12 | 0.93 | 3.40 | 1.97 | 11.4 | 53.9 |

| Soluble fiber | 8.90 | 0.00 | 14.8 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 13.2 |

| Insoluble fiber | 5.36 | 7.12 | 4.51 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.81 |

| Ashes | 22.0 | 34.2 | 1.13 | 3.02 | 3.72 | 4.20 | 2.05 |

| Resistant starch | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 3.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).