1. Introduction

Drug resistance is a major challenge in breast cancer (BC) therapy, particularly for patients with advanced disease. Even individuals at the same tumor stage may respond differently to chemotherapy. Although about 60% of patients with early-stage BC receive chemotherapy, only a minority truly benefit from it [

1]. To address this limitation, research is focusing not only on more effective anticancer agents but also on strategies to overcome resistance. One such approach involves the use of drug resistance modulators. These agents are not chemotherapeutics themselves, but when combined with chemotherapy, they can restore sensitivity in otherwise resistant tumors.

Galactosylceramide (GalCer) is best known as an essential component of myelin produced by oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells [

8]. This simple glycosphingolipid (GSL) is synthesized by galactosylceramide synthase (UGT8, EC 2.4.1.47) [

12] whose expression is highly increased in a subset of BC tumors with a significantly increased risk of lung metastases [

2,

6] and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [

4]. Gene expression profiles of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) have also been characterized by

UGT8 gene overexpression [

10,

11]. Accumulating data strongly suggest that GalCer plays an important role in BC progression [

9,

14]. Previous studies have also demonstrated that BC cells that naturally overexpress UGT8, or those that overexpress UGT8 after transduction with UGT8 cDNA, are more resistant to anti-cancer drug-induced cytotoxicity than their UGT8-negative counterparts [

13]. Conversely, inhibiting UGT8 expression in BC cells makes them more susceptible to doxorubicin (DOX). Therefore, we propose using chemical inhibitors to block UGT8 activity and, in this way, increase the sensitivity of BC cells to conventional chemotherapy. Previously, we demonstrated that murine 4T1.UGT8a mammary carcinoma (MC) cells overexpressing murine UGT8 (UGT8a) and producing excessive amounts of GalCer were, like human BC cells, more resistant to DOX in vitro and to DOX therapy when transplanted into Balb/c mice than control 4T1 cells that do not express UGT8a [

13]. Therefore, as proof of the concept that inhibiting UGT8 activity and therefore synthesis of GalCer increases BC cell sensitivity to anti-cancer drugs, we treated 4T1.UGTa cells in vitro and in vivo with DOX, either with or without UGT8 inhibitor: 3-(methylcarbamoyl)-7-(trifluoromethyl)thieno[3,2-b]pyridin-5-yl)-piperidin-4-yl-(S)-1-(trifluoromethoxy)propan-2-ylcarbamate [

15].

2. Results

2.1. In Vitro Sensitivity of Murine 4T1.UGT8a MC Cells Overexpressing UGT8a to DOX When Grown in the Presence of a UGT8 Inhibitor and Its Liposomal Formulation

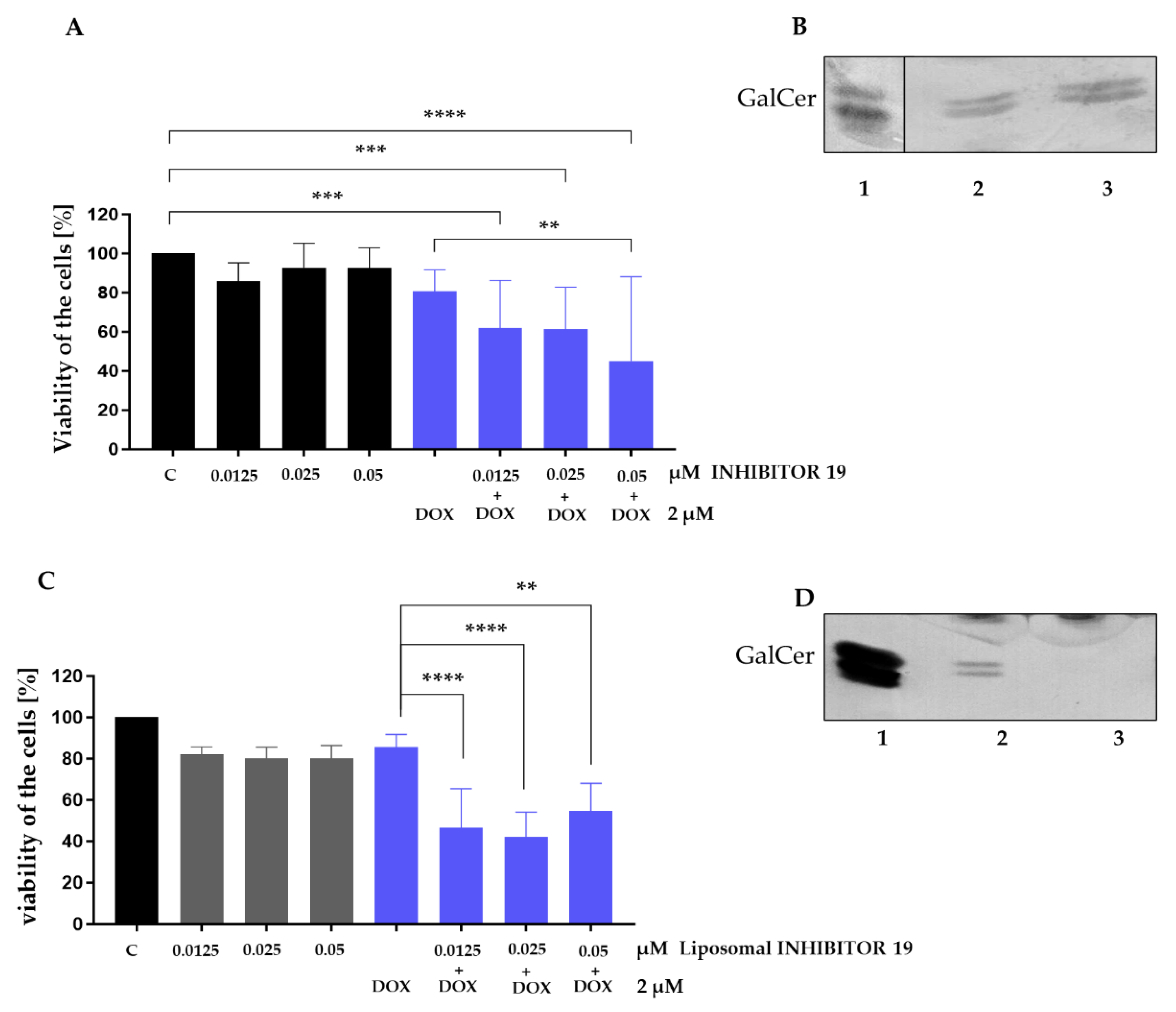

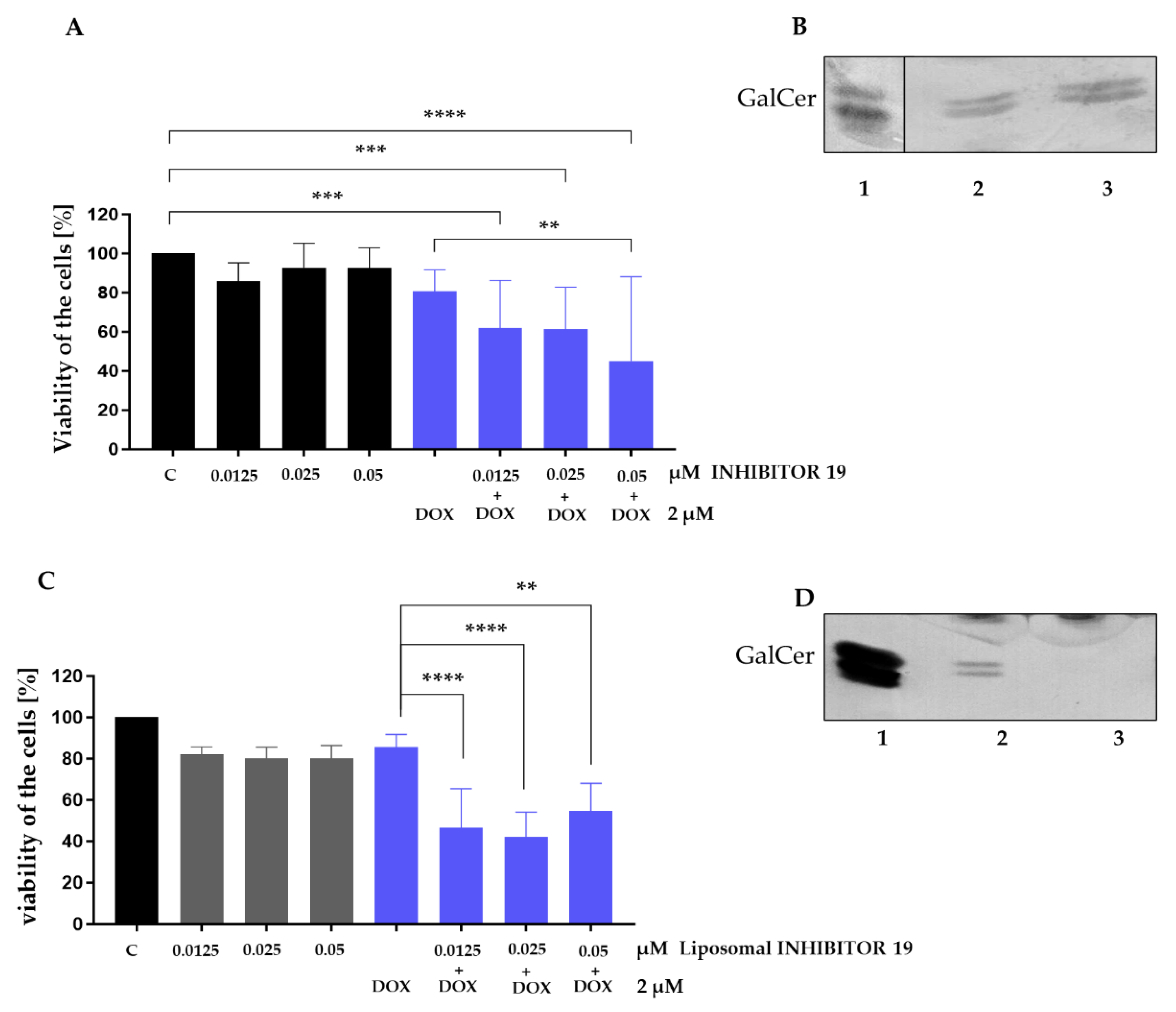

Murine MC 4T1.UGT8a cells overexpressing UGT8a were cultured for 48 hours in the presence of increasing concentrations of Inhibitor 19, a specific UGT8 inhibitor [

15]. Cell sensitivity to the inhibitor was assessed using the MTT assay. Inhibitor 19 was not toxic to murine MC cells up to a concentration of 0.05 µM (

Figure 1A). As expected, treatment with 2 µM DOX, an anti-cancer drug, alone did not affect 4T1.UGT8a cell viability [

13]. However, simultaneous treatment with DOX and increasing concentrations of Inhibitor 19 resulted in a slight increase in the sensitivity of UGT8-overexpressing cells to the drug (

Figure 1A).

As previously demonstrated, one mechanism by which BC cells are resistant to DOX relies on the accumulation of GalCer due to overexpression of UGT8 [

9,

13]. Consistent with these findings, we analyzed the level of GalCer in 4T1.UGTa cells incubated with Inhibitor 19. When neutral GSLs were purified from such cells and subjected to a high-performance thin-layer chromatogram (HP-TLC) binding assay with anti-GalCer antibodies, it was found that the amount of GalCer synthesized by cells treated with the UGT8 inhibitor was comparable to the amount produced by untreated cells (

Figure 1B). These results suggested that the decrease in cell viability when grown in the presence of DOX and Inhibitor 19 is not due to the specific inhibition of GalCer synthesis, but rather to the increased cytotoxicity of the inhibitor when applied with DOX.

Considering the results obtained, we decided to encapsulate Inhibitor 19 in liposomes to decrease its toxicity. Due to the pronounced hydrophobicity of the inhibitor, we chose passive loading into conventional liposomes prepared by sonication. Pegylation was not applied, as the possibility of repeated liposome administration could have resulted in the ABC (accelerated blood clearance) effect, leading to reduced activity of PEG-modified vesicles. The small size and negative surface charge of the obtained liposomes were expected to facilitate their accumulation. The average size of Inhibitor 19-loaded liposomes was approximately 112 nm, whereas the mean liposomes peak was at 66 nm (

Suppl. Figure 1A), with a zeta potential of −58 mV. The Inhibitor 19 incorporation efficiency was high, reaching about 98–99%. The basic characteristics of the formulation are presented in

Suppl. Figure 1B.

When 4T1.UGT8a cells were cultured with the same concentrations of Inhibitor 19 as above, but encapsulated in liposomes; the compound's cytotoxicity against these cells remained unchanged (

Figure 1C). On the other hand, we found that the liposomal form of Inhibitor 19 is more effective at lower concentrations when applied with DOX to 4T1.UGT8a cells. A statistically significant decrease in the viability of MC cells was already observed at an inhibitor concentration as low as 0.0125 µM. To show that the observed increase in sensitivity to DOX is linked to inhibition of UGT8 activity by the encapsulated form of Inhibitor 19, as above, neutral GSLs were purified from 4T1.UGT8a cells grown in the presence of Inhibitor 19, and analyzed by HP-TLC chromatogram binding assay with anti-GalCer antibodies. We have found that the incubation of 4T1.UGT8a cells overexpressing UGT8a with the liposomal form of Inhibitor 19 resulted in highly dereased level of GalCer (

Figure 1D). This result strongly suggested that the changes in sensitivity of cells to DOX are the result of inhibition of GalCer synthesis. Therefore, taking into consideration the obvious advantages of using liposomes, further experiments were performed using the encapsulated form of Inhibitor 19.

Figure 1.

(A) Viability of murine mammary carcinoma 4T1.UGT8a cells overexpressing UGT8a and accumulating GalCer, treated for 48 h with increasing concentrations of UGT8 inhibitor (Inhibitor 19) alone (black bars) or in combination with doxorubicin (DOX, blue bars). Cell viability was determined using the MTT assay. Data represent mean ± SD of six replicates from two independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). C – control cells grown in complete medium; DOX – cells treated with doxorubicin. (B) Immunostaining of neutral glycosphingolipids (GSLs) from 4T1.UGT8a cells grown in the absence (lane 2) or presence of 0.025 µM Inhibitor 19 (lane 3). Neutral GSLs were separated by HP-TLC and detected using anti-GalCer rabbit polyclonal antibodies. Lane 1 – GalCer (galactosylceramide) standard. (C) Viability of murine 4T1.UGT8a cells overexpressing UGT8a and accumulating GalCer, treated for 48 h with increasing concentrations of the liposomal form of Inhibitor 19 alone or in combination with DOX. Cell viability was measured using the MTT assay. Data represent mean ± SD of six replicates from two independent experiments (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). (D) Immunostaining of neutral GSLs from 4T1.UGT8a cells grown in the absence (lane 2) or presence of 0.025 µM liposomal Inhibitor 19 (lane 3). Neutral GSLs were separated by HP-TLC and detected using anti-GalCer rabbit polyclonal antibodies. Lane 1 – GalCer standard.

Figure 1.

(A) Viability of murine mammary carcinoma 4T1.UGT8a cells overexpressing UGT8a and accumulating GalCer, treated for 48 h with increasing concentrations of UGT8 inhibitor (Inhibitor 19) alone (black bars) or in combination with doxorubicin (DOX, blue bars). Cell viability was determined using the MTT assay. Data represent mean ± SD of six replicates from two independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). C – control cells grown in complete medium; DOX – cells treated with doxorubicin. (B) Immunostaining of neutral glycosphingolipids (GSLs) from 4T1.UGT8a cells grown in the absence (lane 2) or presence of 0.025 µM Inhibitor 19 (lane 3). Neutral GSLs were separated by HP-TLC and detected using anti-GalCer rabbit polyclonal antibodies. Lane 1 – GalCer (galactosylceramide) standard. (C) Viability of murine 4T1.UGT8a cells overexpressing UGT8a and accumulating GalCer, treated for 48 h with increasing concentrations of the liposomal form of Inhibitor 19 alone or in combination with DOX. Cell viability was measured using the MTT assay. Data represent mean ± SD of six replicates from two independent experiments (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). (D) Immunostaining of neutral GSLs from 4T1.UGT8a cells grown in the absence (lane 2) or presence of 0.025 µM liposomal Inhibitor 19 (lane 3). Neutral GSLs were separated by HP-TLC and detected using anti-GalCer rabbit polyclonal antibodies. Lane 1 – GalCer standard.

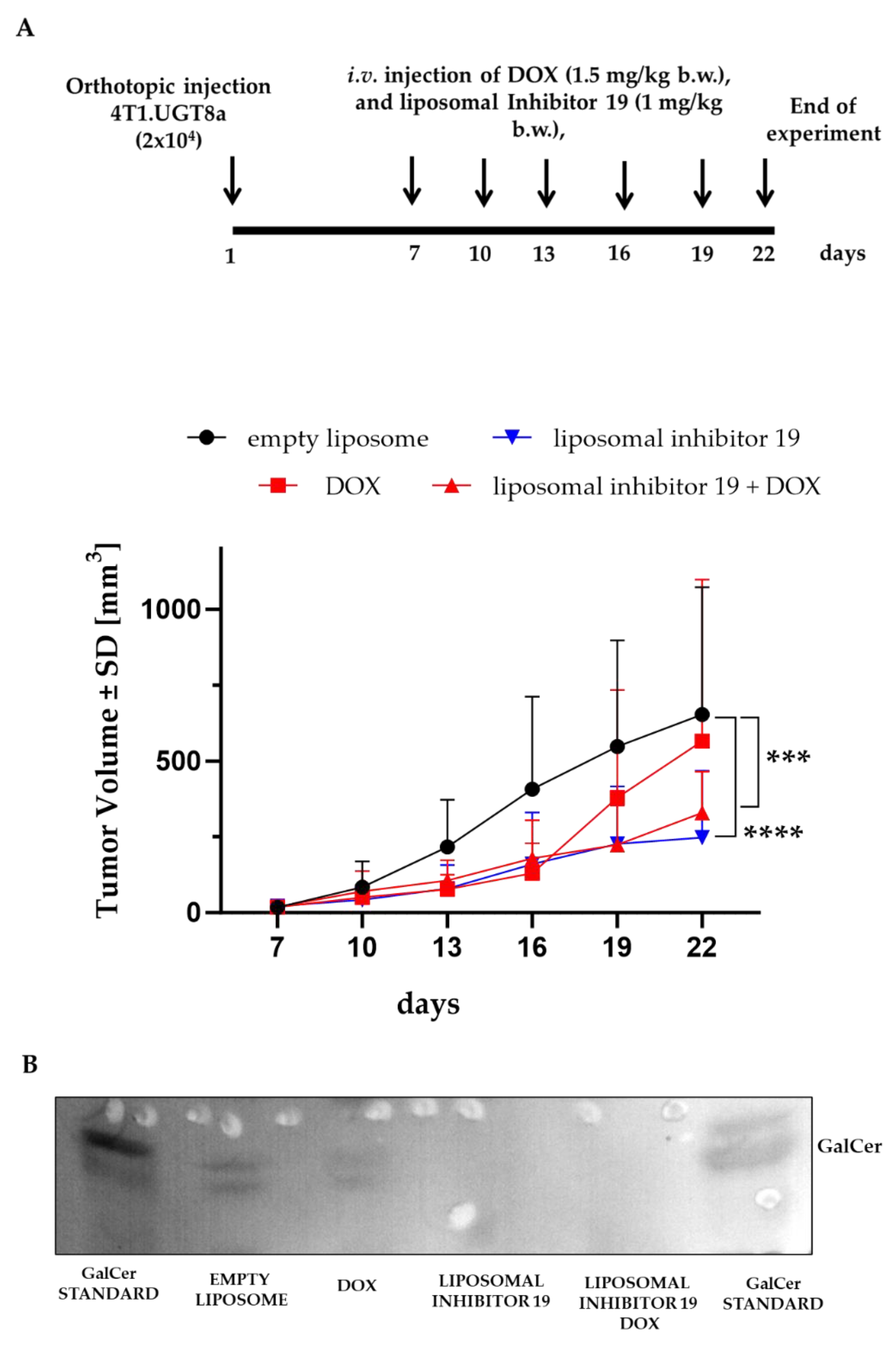

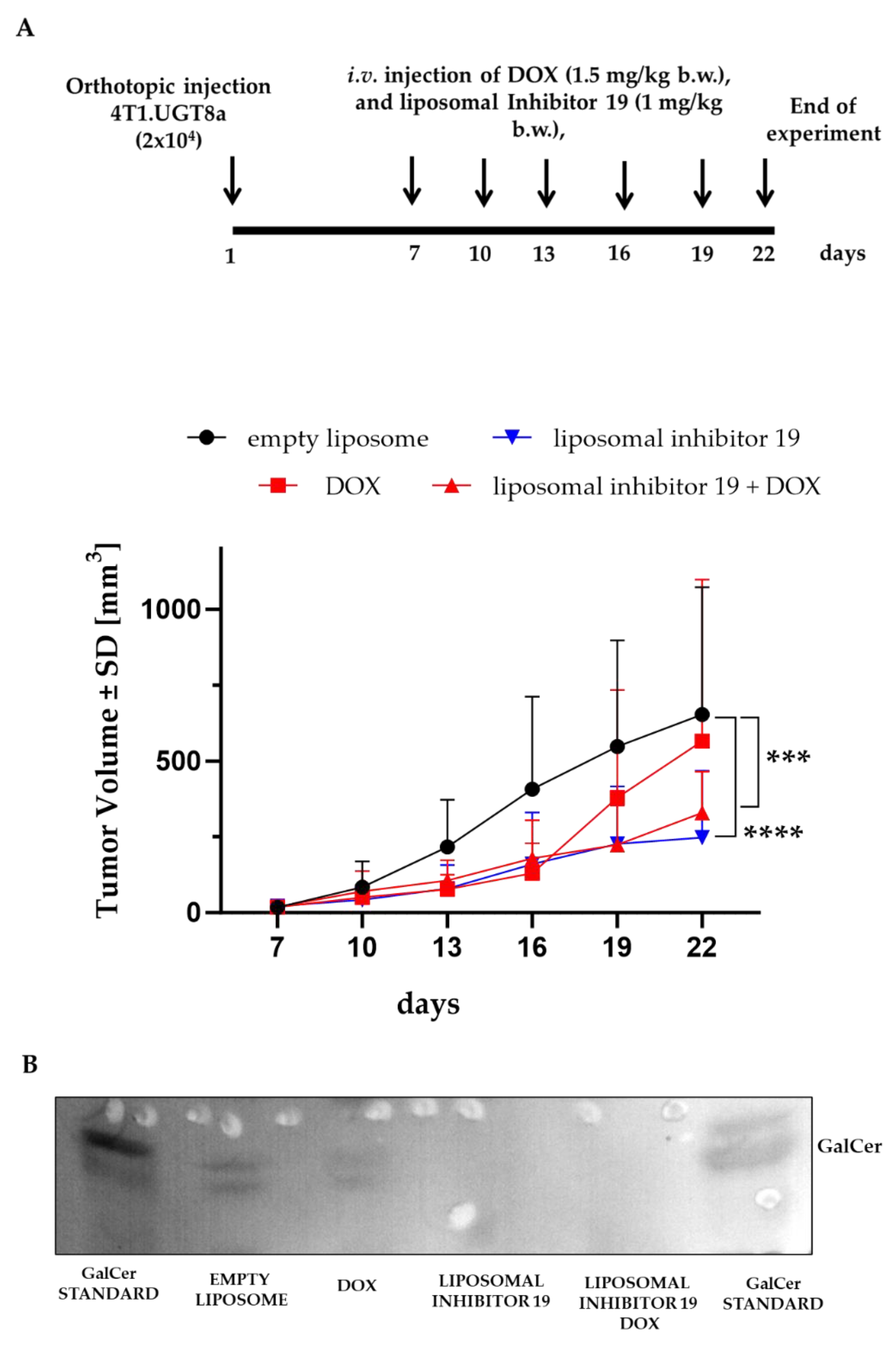

2.2. Effect of Inhibitor 19 Liposomes on the Growth of MC Tumors Following the Orthotopic Transplantation of 4T1.UGT8a Cells into Balb/c Mice

To evaluate the antitumor effectiveness of Inhibitor 19, Balb/c female mice were orthotopically transplanted with 4T1.UGT8a cells. In the preliminary experiment, tumor-bearing mice were injected intravenously three times a week with increased concentrations of the liposomal formulation of Inhibitor 19 (0.5 mg/kg body weight, (b.w.) 0.75 mg/kg b.w., and 1.0 mg/kg b.w.). After 22 days, animals were sacrificed, and the tumors were dissected. From such tumors, neutral GSLs were purified and subjected to HP-TLC binding assay with anti-GalCer antibodies (

Suppl. Figure 2). A decreased level of GalCer was already observed at a concentration of UGT8 inhibitor of 0.75-1.0 mg/ml. However, for further in vivo studies, 1.0 mg/kg b.w. of Inhibitor 19 was chosen, as at this concentration, GalCer level was highly decreased.

In the proper experiment, tumor-bearing mice were treated with 1 mg/kg b.w. of encapsulated Inhibitor19 and DOX (1.5 mg/kg b.w.) (

Figure 2A). Growth of the 4T1.UGT8 tumors were significantly suppressed compared to untreated animals or those treated with DOX alone (

Figure 2A). On day 22, the mean tumor volumes formed by 4T1.UGT8a cells in mice treated with the liposomal formulation of Inhibitor 19 and DOX were equal to 329 mm³ (±127) compared to tumor volumes of 653 mm³ (±392) and 593 mm³ (±493), respectively, formed by 4T1.UGT8a cells in untreated mice and mice treated with DOX alone. The lack of difference in 4T1.UGT8a tumor growth between mice treated with placebo (empty liposomes) and mice treated with empty liposomes and DOX confirmed our earlier results showing the resistance of 4T1 cells that overexpress UGT8a to this anti-cancer drug [

13]. We also found that treating the mice only with liposomal inhibitor 19 highly inhibits the growth of 4T1.UGT8a tumors [247 mm³ (±206)].

To further confirm that the suppression of 4T1.UGTa tumor growth is causally related to the inhibition of UGT8 activity and the absence of GalCer, as described above, neutral GSLs were isolated from these tumors. As expected, in tumors isolated from mice treated with Inhibitor 19, no band corresponding to GalCer was detected (

Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Allogenic tumor growth of 4T1.UGT8a cells in mice injected intravenously three times a week with empty liposomes (black dots), DOX (1.5 mg/kg b.w.) (red square), DOX (1.5 mg/kg b.w.) and liposomal form of Inhibitor 19 (1 mg/kg b.w.) (red triangle), and liposomal form of Inhibitor 19 (1 mg/kg b.w.) alone (blue triangle). Tumor growth was recorded every three days using metric calipers. Data are shown as the mean tumor volume for each group of mice (n=8) ±SD. (B) Immunostaining of neutral glycosphingolipids (GSLs) isolated from 4T1.UGT8a tumors. Neutral GSLs were separated by HP-TLC and detected using anti-GalCer rabbit polyclonal antibodies. Aliquot of total neutral GSLs corresponding to 30 mg tumor was applied to the HP-TLC plate. Empty liposome –tumor tissue from mice injected with empty liposomes, DOX – tumor tissue from mice mice injected with DOX alone, liposomal Inhibitor 19 – tumor tissue from mice injected with Inhibitor 19 alone, liposomal Inhibitor 19 DOX – tumor tissue from mice injected with Inhibitor 19 and DOX. .

Figure 2.

(A) Allogenic tumor growth of 4T1.UGT8a cells in mice injected intravenously three times a week with empty liposomes (black dots), DOX (1.5 mg/kg b.w.) (red square), DOX (1.5 mg/kg b.w.) and liposomal form of Inhibitor 19 (1 mg/kg b.w.) (red triangle), and liposomal form of Inhibitor 19 (1 mg/kg b.w.) alone (blue triangle). Tumor growth was recorded every three days using metric calipers. Data are shown as the mean tumor volume for each group of mice (n=8) ±SD. (B) Immunostaining of neutral glycosphingolipids (GSLs) isolated from 4T1.UGT8a tumors. Neutral GSLs were separated by HP-TLC and detected using anti-GalCer rabbit polyclonal antibodies. Aliquot of total neutral GSLs corresponding to 30 mg tumor was applied to the HP-TLC plate. Empty liposome –tumor tissue from mice injected with empty liposomes, DOX – tumor tissue from mice mice injected with DOX alone, liposomal Inhibitor 19 – tumor tissue from mice injected with Inhibitor 19 alone, liposomal Inhibitor 19 DOX – tumor tissue from mice injected with Inhibitor 19 and DOX. .

3. Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that overexpressing UGT8 enhances BC cell resistance to DOX-induced apoptosis, improving survival when cells are exposed to the anti-cancer drug [

9,

13]. Conversely, inhibiting UGT8 expression increases sensitivity to chemotherapeutics. Studies have shown that these anti-apoptotic effects are mediated by GalCer, a molecule produced by a reaction catalyzed by UGT8. We have shown that GalCer downregulates the levels of the pro-apoptotic TNFRSF1B and TNFRSF9 proteins and upregulates the levels of the anti-apoptotic Bcl2 protein at the transcriptional level. The regulatory protein that controls their expression is likely p53, the expression of which is GalCer-dependent [

13]. Based on these findings, we propose that inhibiting UGT8 activity with a small-molecule inhibitor would increase BC cells' sensitivity to standard chemotherapy. To test this hypothesis, we used 4T1.UGT8a murine MC cells that overexpress murine UGT8 (UGT8a). As it was shown, murine 4T1 cells represent a useful preclinical model for TNBC with a similar aggressive phenotype to the human cancer [

5]. As demonstrated, MC cells that accumulate GalCer, like human BC cells, become more resistant to DOX [

13]. When these cells were injected into Balb/c mice, they exhibited greater resistance to DOX therapy than control GalCer-negative 4T1 cells.

In our study, in order to inhibit the activity of UGT8, we used 3-(methylcarbamoyl)-7-(trifluoromethyl)thieno[3,2-b]pyridin-5-yl)-piperidin-4-yl-(S)-1-(trifluoromethoxy)propan-2-ylcarbamate, known under the trade name Inhibitor 19. This compound was originally used to inhibit the synthesis of GalCer in the brains and kidneys of mice as a potential small-molecule drug for treating lysosomal storage disorders, such as metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) [

15]. When 4T1.UGT8a cells were incubated with Inhibitor 19 alone, which was not toxic to the cells up to a concentration of 0.05 µM. However, when applied with DOX, it slightly decreased the viability of cells that are themselves resistant to the action of DOX. Unfortunately, the analysis of neutral GSLs purified from 4T1.UGT8a cells treated with Inhibitor 19 revealed that amounts of GalCer in such cells were comparable with amounts of GalCer in untreated cells, which demonstrated that this compound is not effective as a UGT8 inhibitor in the case of murine MC cells. Moreover, this indicated that the presence of DOX increases the cytotoxicity of the inhibitor for unknown reasons. As demonstrated with anti-cancer drugs, one way to overcome the cytotoxicity associated with their use is to encapsulate them in liposomes, which are increasingly employed for drug delivery in the treatment of various diseases [

17]. These spherules, which range in diameter from 20 nm to several µm, are composed of a polar lipid bilayer that entraps a central aqueous space [

3]. Therefore, to overcome these difficulties, we decided to encapsulate Inhibitor 19 in liposomes composed of soy phosphatidylcholine (SPC 90G) and dipalmitoylphosphatidylglycerol (DPPG) at a molar ratio of 80:20. This formulation was chosen because it was not toxic to murine MC 4T1 cells and encapsulated relatively high amounts of the inhibitor in comparison with other tested formulas.

To evaluate the inhibitory properties of the liposomal form of Inhibitor 19, the neutral GSLs were purified from the 4T1.UGT8a cells that were treated with the liposomal UGT8 inhibitor. Then, the GSLs were subjected as before to an HP-TLC chromatogram binding assay with anti-GalCer antibodies. Unlike the free form of Inhibitor 19, the encapsulated form was highly effective in inhibiting UGT8 enzymatic activity, as evidenced by the lack of binding of anti-GalCer antibodies to neutral GSLs from inhibitor-treated cells compared to cells grown in the absence of this compound. Importantly, such cells became more sensitive to the effects of DOX, reflected by lower survival rates in the presence of the inhibitor. Based on these in vitro results, the in vivo antitumor effects of Inhibitor 19 were evaluated by orthotopically injecting mice with MC 4T1.UGT8a cells that overexpress UGT8a. The mice were then treated with DOX and Inhibitor 19 intravenously. When mice were inoculated with 1.5 mg/kg of b.w. of DOX and a 1 mg dose of liposomal inhibitor 19/kg of b.w. three times a week for three weeks, the average tumor volume was 329 mm³ (±127). By comparison, the average tumor volume formed by 4T1.UGT8a cells treated with DOX alone were 593 mm³ (±493). This indicates that animals treated with DOX and a UGT8 inhibitor exhibited 55% tumor regression compared to those treated with DOX alone. Additionally, we found that treating the mice with liposomal inhibitor 19 alone inhibits the growth of 4T1.UGT8a tumors in a manner comparable to doxorubicin and the UGT8 inhibitor. These results are consistent with our previous findings that suppressing UGT8 expression in human BC cells using shRNA significantly reduces their tumorigenic potential when transplanted into nude mice [

9].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cells and Culture Conditions

The murine 4T1 mammary carcinoma (MC) cell line was obtained from the Cell Line Collection at the Ludwik Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy (Wroclaw, Poland). The 4T1.UGT8 cells, which overexpress mouse UGT8a, and the control 4T1.C cells were previously described by Suchanski et al. (2024) [

13]. The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Cytogen, Poland), 2 mM L-glutamine, and antibiotics (Biowest, USA).

4.2. Encapsulation of Inhibitor 19

Liposomes were prepared using the thin lipid film hydration method. Soy phosphatidylcholine (SPC 90G) and dipalmitoylphosphatidylglycerol (DPPG) were dissolved in a molar ratio of 80:20. A chloroform solution of Inhibitor 19 [(3-(Methylcarbamoyl)-7-(trifluoromethyl)thieno[3,2-b]pyridin-5-yl)piperidin-4-yl (S)-(1- (trifluoromethoxy)propan-2-yl) carbamate, Cayman Chemical, USA)] was added to this mixture at a lipid: Inhibitor 19 weight ratio of 10:1. The chloroform organic phase was evaporated, and the resulting lipid film was hydrated with ultrapure MILIQ water to obtain an MLV (multilamellar vesicle) liposome suspension. This mixture was then homogenized using a Sonics Vibracell VCX-130 (Sonics & Materials, USA.) ultrasonic homogenizer at 30% amplitude for 1 minute of sonication. The resulting SUV (small unilamellar vesicle) liposome suspension was then centrifuged to remove unencapsulated and water-insoluble Inhibitor 19 by spinning in a laboratory centrifuge at 13,000 RPM for 2 minutes. The supernatant containing the liposome suspension with encapsulated Inhibitor 19 was separated from any potential sediment and subjected to further processing and analysis. Inhibitor 19 liposomes were then analyzed using DLS (Dynamic Light Scattering) to determine their size, homogeneity, and zeta potential with a Malvern Zetasizer NanoZS (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., United Kingdom). The encapsulation efficiency and concentration of Inhibitor 19 in the liposomes were determined using the HPLC (High-Performance Liquid Chromatography) method based on a Waters 600 Controller and Pump coupled system and Waters 996 PDA Detector. (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA).

4.3. Cell Survival Assay

An MTT assay was used to determine cell viability. Cells were seeded in individual 96-well plates (5×10³ cells/well) (Nunc, USA) and incubated for 48 hours with 0.0125 µM, 0.025 µM, and 0.05 µM of Inhibitor 19 (Cayman Chemical) or its liposomal formulation at the same concentrations with or without 2 µM doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX) (Pfizer, USA). Then, the medium was discarded and the cells were incubated with an MTT solution (5 mg/mL, Merck) for four hours at 37°C. After discarding the MTT solution, 100 µL of DMSO (Chempur, Poland) was added to each well to dissolve the formed formazan. Absorbance at 560 nm was measured using a SparkControl Multilabel Reader (Tecan, USA). The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times independently.

4.4. In Vivo Tumor Growth Assay

The experiment was carried out on six-week-old female Balb/c mice obtained from the Animal Facility of the Center for Experimental Medicine at the Medical University of Bialystok (Poland). The Local Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation (Wroclaw, Poland) approved the animal experiment under protocol No. 33/2019/P1. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was reported under the ARRIVE guidelines. The mice were maintained under a 12-hour day/night cycle with unrestricted access to food and water.

Suspensions of 4T1 murine MC cells (2×10⁴ cells/50 µL PBS) mixed with an equal volume of ice-cold BD Matrigel Matrix High Concentration (Corning, USA) were injected orthotopically into the mammary fat pad. Tumor growth was monitored every three days by measuring tumor diameters with a caliper. Tumor volume (TV) was calculated using the formula TV (mm³) = (d² × D)/2, where d is the shortest diameter and D is the longest diameter. For therapeutic experiments, mice were injected intravenously three times a week with a liposomal formulation of Inhibitor 19 (1 mg/kg b. w.) and DOX (1.5 mg/kg b.w.). The mice were euthanized via cervical dislocation after being lightly anesthetized with isoflurane (Forane, Abbott Laboratories, USA).

4.5. Purification of Neutral Glycosphingolipids

Neutral GSLs were extracted from 10

7-10

8 cells or 30 mg of homogenized tumor tissues with chloroform/methanol/water, 20/10/1, 10/20/1, and 10/10/1 by volume and purified as previously described [

16]. In brief, the combined extracts were desalted on a Sephadex G-25 superfine column (Pharmacia Biotech, Sweden) after mild alkaline hydrolysis with 0.2 M KOH in methanol. The neutral GSLs were separated from the gangliosides using a DEAE-Sephadex A-25 column (Pharmacia Biotech).

4.6. High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography (HP-TLC) and Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC)-Binding Assay

Neutral GSLs were analyzed by HP-TLC on silica gel 60 HP-TLC plates (Merck) with a solvent system of chloroform/methanol/water (65/35/8 by volume). The neutral GSL standards were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

GalCer was detected using a TLC-binding assay [

7] with rabbit polyclonal anti-GalCer antibodies (Merck, Germany) and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Promega).

4.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, USA). The results were considered statistically significant when p ≤ 0.05.

5. Conclusions

Our results showed that the liposomal form of Inhibitor 19 remarkably enhanced the antitumor effects of DOX therapy in DOX-resistant, GalCer-producing, mammary carcinoma cells that overexpress UGT8a. This UGT8 inhibitor's antitumor effect is based on GalCer synthesis inhibition because GalCer acts as an anti-apoptotic molecule [

13]. Therefore, we propose that therapy with small-molecule UGT8 inhibitors together with anti-cancer drugs is a novel approach to overcoming drug resistance in a subset of BC tumors that overexpress UGT8 [

2].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1A and B: Size distribution plot and basic characteristics of the formulation used in the experiment.

Author Contributions

Investigation, A.U., A.M., J.S., and K.J.; visualization, A.U., K.J.; methodology, A.U., J.S., A.M.; writing- review& editing, A.U., A.M., J.G., and M.U.; conceptualization, A.U., and M.U.; supervision, M.U., J.G., and P.D.; funding acquisition, M.U., P.D., and J.G.; project administration, M.U.; writing- original draft, M.U. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Funding

Grant support for this work was provided by the National Science Center, Poland (Grant no. 2019/35/B/NZ5/01392). The APC is financed by Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Sciences and the Wroclaw Medical University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Second Local Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation (033/2019/P1, Wroclaw, Poland), 19 June 2019.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Colombo, P.E.; Milanezi F., Weigelt B., Reis-Filho J.S.: Microarrays in the 2010s: the contribution of microarray-based gene expression profiling to breast cancer classification, prognostication and prediction. Breast Cancer Research, 2011, 13: 212. [CrossRef]

- Dziegiel, P.; Owczarek, T.; Plazuk, E.; Gomulkiewicz, A.; Majchrzak, M.; Podhorska-Okolow, M.; Driouch, K.; Lidereau, R.; Ugorski, M. Ceramide galactosyltransferase (UGT8) is a molecular marker of breast cancer malignancy and lung metastases. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 103, 524–531. [CrossRef]

- Izadiyan Z, Misran M, Kalantari K, Webster TJ, Kia P, Basrowi NA, Rasouli E, Shameli K. Advancements in Liposomal Nanomedicines: Innovative Formulations, Therapeutic Applications, and Future Directions in Precision Medicine. Int J Nanomedicine. 2025;20:1213-1262. [CrossRef]

- Ji J., Xie M.R., Qian Q.L., Xu Y.X., Shi W., Chen Z.F., Ren D.X., Liu W.W., He X.B., Lv M.X., et al: SOX9-mediated UGT8 expression promotes glycolysis and maintains the malignancy of non-small cell lung cancer. Biochem Bioph Res Co 2022, 587:139-145. [CrossRef]

- Kaur P., Nagaraja G.M., Zheng H., Gizachew D., Galukande M., Krishnan, ASea A.: A mouse model for triple-negative breast cancer tumor-initiating cells (TNBC-TICs) exhibits a similar aggressive phenotype to the human disease. BMC Cancer, 2012, 12: 120. [CrossRef]

- Landemaine T., Jackson A., Bellahcene A., Rucci N., Sin S., Abad B.M., Sierra A., Boudinet A., Guinebretiere J.M., Ricevuto E., Nogues C., Brifford M., Bieche I., Cherel P., Garcia T., Castronovo V., Teti A., Lidereau R., Driouch K.: A six-gene signature predicting breast cancer lung metastasis. Cancer Res 68: 6092–6099. [CrossRef]

- Magnani JL, Nilsson B, Brockhaus M, Zopf D, Steplewski Z, Koprowski H, Ginsburg V (1982) A monoclonal antibody-defined antigen associated with gastrointestinal cancer is a ganglioside containing sialylated lacto N-fucopentaose II. J Biol Chem 257: 14365–14369. [CrossRef]

- Marcus, J.; Popko, B. Galactolipids are molecular determinants of myelin development and axo-glial organization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2002, 1573, 406–413. [CrossRef]

- Owczarek, T.B.; Suchanski, J.; Pula, B.; Kmiecik, A.M.; Chadalski, M.; Jethon, A.; Dziegiel, P.; Ugorski, M. Galactosylceramide Affects Tumorigenic and Metastatic Properties of Breast Cancer Cells as an Anti-Apoptotic Molecule. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84191. [CrossRef]

- Santuario-Facio SK, Cardona-Huerta S, Perez-Paramo YX, Trevino V, Hernandez-Cabrera F, Rojas-Martinez A, Uscanga-Perales G, Martinez-Rodriguez JL, Martinez-Jacobo L, Padilla-Rivas G et al: A New Gene Expression Signature for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Using Frozen Fresh Tissue before Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Mol Med 2017, 23. [CrossRef]

- Segaert P, Lopes MB, Casimiro S, Vinga S, Rousseeuw PJ: Robust identification of target genes and outliers in triple-negative breast cancer data. Stat Methods Med Res 2019, 28(10-11):3042-3056. [CrossRef]

- Sprong H, Kruithof B, Leijendekker R, Slot JW, van Meer G, et al. (1998) UDP galactose: ceramide galactosyltransferase is a class I integral membrane protein of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 273: 25880–25888. [CrossRef]

- Suchanski J., Reza S., Urbaniak A., Woldanska W., Kocbach B., Ugorski M.: Galactosylceramide Upregulates the Expression of the BCL2 Gene and Downregulates the Expression of TNFRSF1B and TNFRSF9 Genes, Acting as an Anti-Apoptotic Molecule in Breast Cancer Cells. Cancers (Basel). 2024 Jan 17;16(2):389. [CrossRef]

- Suchanski, J.; Grzegrzolka, J.; Owczarek, T.; Pasikowski, P.; Piotrowska, A.; Kocbach, B.; Nowak, A.; Dziegiel, P.; Wojnar, A.; Ugorski, M. Sulfatide decreases the resistance to stress-induced apoptosis and increases P-selectin-mediated adhesion: A two-edged sword in breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res. 2018, 20, 133. [CrossRef]

- Thurairatnam S., Lim S., Barker R.H., Choi-Sledeski Y.M., Hirth B.H., Jiang J., Macor J. E., Makino E., Maniar S., Musick K., Pribish J.R., Munson M., Brain Penetrable Inhibitors of Ceramide Galactosyltransferase for the Treatment of Lysosomal Storage Disorders. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2020 Jun 16;11(10):2010-2016. eCollection 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ugorski, M.; Pahlsson, P.; Dus, D.; Nilsson, B.; Radzikowski, C. Glycosphingolipids of Human Urothelial Cell-Lines with Different Grades of Transformation. Glycoconj. J. 1989, 6, 303–318. [CrossRef]

- Wang S., Chen Y., Guo J., Huang Q.: Liposomes for Tumor Targeted Therapy: A Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jan 31;24(3):2643. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).