1. Introduction

Natural disasters represent profound ecological and social disruptions, causing widespread damage, hardship, and loss of life. For older adults, a demographic particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of such catastrophes, the aftermath extends beyond physical destruction to encompass significant and lasting psychological challenges (Parker et al., 2016). The stress of coping with loss, trauma, and displacement can severely impact mental health and wellbeing. In this context, social support emerges as a critical buffer, serving as a protective factor that can mitigate negative outcomes and foster resilience (Kaniasty & Norris, 2009). However, the very fabric of social support is often threatened when disasters devastate communities, potentially eroding the networks that survivors rely upon most (Bonanno et al., 2010). Consequently, accurately measuring the perception of available support is paramount for understanding recovery trajectories. This study investigates the applicability of a key psychometric instrument, the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), for use with older adults recovering from natural disasters.

The gerontological literature has long established that robust social networks and high levels of perceived social support are strongly associated with better physical and mental health outcomes in older adulthood (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). Unlike received support, which pertains to actual supportive acts, perceived social support refers to an individual’s subjective appraisal that help will be available when needed from their network (Lakey & Cohen, 2000). This perception is a powerful psychological resource, linked to reduced rates of cognitive decline, lower morbidity, and increased longevity (Holt-Lunstad, 2018). For older disaster survivors, who may face compounded losses including the death of peers, destruction of community hubs, and forced relocation, the perception that support remains available may be a crucial determinant of their ability to cope and adapt (Cherry et al., 2015).

Despite its importance, a significant gap exists in the disaster literature concerning how older adults specifically perceive their social support following a catastrophic event. Many studies utilize scales designed for and validated on general adult populations, neglecting the unique social contexts and support structures of older adulthood (Knight et al., 2000). The MSPSS, developed by Zimet et al. (1988), is one such instrument. It is a brief, self-report measure designed to assess perceptions of support from three distinct sources: Family, Friends, and a Significant Other. While its psychometric properties are well-established across diverse populations, including adolescents and various patient groups (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000), its factorial validity, reliability, and applicability for older adults, particularly in the high-stress context of a natural disaster, remain unexplored.

The evaluation of an instrument’s construct validity is a fundamental step in social science research. Factor analysis, including both exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory (CFA) techniques, is essential for verifying whether a scale’s hypothesized structure holds true for a new population (Brown, 2015). Using a scale without such validation risks systematic measurement error and biased findings, ultimately limiting the utility of research for informing effective interventions (Podsakoff et al., 2012).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Natural Disasters

Although definitions vary, disasters are usually conceptualized as natural or human-made events that cause sweeping damage, hardship, or loss of life across one or more strata of society (Quarantelli, 1998). Disasters typically strike swiftly, but it can take years to recover from them. Natural disasters can cause lasting psychological harm and research indicates that survivors experience severe levels of psychological distress (Bonanno et al., 2011). When natural disasters happen, the survivors face a multitude of harms such as coping with loss, trauma, and possible physical harm. It can involve immediate life-threatening situations and the destruction of value (monetary, symbolic, emotional) and the stress that this causes can impact survivors’ mental health and social support can have a substantial impact with their ability to cope.

The lasting impact of natural disasters can beget a range of psychological consequences (Raphael & Maguire, 2009), but the most relevant question with regards to coping is how to survive without long lasting psychological effects. Surprisingly, the literature on disaster has not adequately addressed this question. It is known that social support is, at the same time a critical resource helping people cope, as it serves to be a protective factor for the survivors and their communities. Given, that natural disasters can devastate entire communities into collective trauma and irrevocably damage social life and the bonds associated with that (Erikson, 1976), researchers must address what can help survivors cope best with the aftermath.

2.2. Perceived Social Support (PSS)

Although disasters may occur suddenly the stress associated with them is not just acute, as they create ongoing and enduring challenges for survivors and communities (Bonanno, 2004). Disasters put families, neighborhoods, and communities at risk. Survivors often receive immediate support from their families, relatives, and friends, and for this reason many survivors subsequently claim that the experience brought them closer together. There is evidence that social relationships can improve after disasters, especially within the immediate family (Raphael & Maguire, 2009). However, the bulk of evidence indicates that the stress of disasters can erode both interpersonal relationships and sense of community (Bonnano, 2004; McFarlane et al., 2009). Regardless of how they are affected, post-disaster social relations are important predictors of coping success and resilience.

According to the contemporary models of stress, social support is a great asset that not only alleviates stress, but also promotes preservation of psychological resources that are needed for successful coping (Goenjian et al., 2001). Studies that have examined the role of social support among victims of natural disasters show that those who had lower levels of perceived support showed greater distress (Cook & Bickman, 1990; Drabek & Key, 1984; Bolin & Bolton, 1986).

2.3. Older Adults and Perceived Social Support

Gerontological research has highlighted the influence of different configurations of social networks and social support on health outcomes. Social support has an important impact on the wellbeing of older adults. Some studies have shown that perceived social support is more important than received social support. Robust social networks are associated with better physical and mental health outcomes (Rodriguez-Laso et al., 2007; Umberson & Montez, 2010), whereas lack of social support has been linked to increased risk for mortality and morbidity (Thoits, 2011). Social support can be regarded as the perception that an individual is cared for and has supports available and the level of integration an individual has in a social network (Antonucci, 1990). Although family and friends typically deliver support, other associates (e.g., coworkers, neighbors) also serve as members in support networks (Seeman & Berkman, 1988).

The receipt of social support plays an important role in cognitive function in older adults. Studies have shown that the presence and degree of social support may reduce the rate of cognitive decline and dementia (Barnes De Leon et al., 2004). Additionally, social support has been shown to protect individuals against the harmful consequences of stressful events, thus exerting positive effects on wellbeing and cognition (Cohen & Willis, 1985). Some scales were originally designed for the assessment of PSS in adults, which are commonly used in studies with elderly, although these were neither specifically designed for elderly, nor were they designed from the perspective of this particular age group. However, there is a dearth of literature on how older adults perceive social support after a natural disaster and this study proposes to fill that gap by examining the structure of the MSPSS as it applies to older adults.

2.4. Theoretical Background

The evaluation of the structure and validity of new and existing measures of psychological traits is an imperative task in social science empirical research. One of the most important statistical techniques in this area is the common factor model: Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). As such, the scholarly literature suggests that self-report measures are commonly inundated with biases (Podsakoff et al., 2012) so it has become increasingly important to resolve this problem by using validated scales that can be generalized over different populations. This can reduce systematic error and help mitigate the bias and take into consideration the scales [sometimes] complex factorial structure.

Several scales designed to measure social support have been described in literature (Bruhm & Philips, 1984; House & Kahn, 1985; and Tardy, 1985). Both quantitative measures of support (e.g., the number of friends one can turn to in a crisis) and qualitative measures (e.g., perceptions of social support adequacy) have been investigated. The MSPSS was theoretically designed to assess perceptions of social support from three different sources: family, friends, and significant other (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000). Although the scale has been shown to be psychometrically sound, reliable, and having factorial and construct validity (Zimet et al., 1990) across college students, it has not been tested on older adults.

In particular, the present study aims to fill this methodological and practical gap by examining the factor structure, reliability, and validity of the MSPSS among older adults affected by a natural disaster. By rigorously testing this instrument, our research seeks to provide researchers and clinicians with a validated tool to accurately assess perceived social support in this vulnerable population. This, in turn, can facilitate the development of targeted support programs, inform policy decisions for disaster preparedness and response, and ultimately contribute to improving the recovery and long-term wellbeing of older adult disaster survivors.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Sources

This study conducted EFA and CFA using two different sets of datasets. The data for EFA were randomly collected in October 2020 from a smaller sample of older adults who aged over 50 and living in the area affected by 2019 Dallas tornado (N = 87). The data for CFA were randomly collected between November 2020 to January 2021 from a larger sample of older adults who aged over 50 and self-identified as affected by 2019 Dallas tornado (N = 205). The researcher used listwise deletion to exclude respondents with missing values in analytic variables, thus the final working samples for EFA and CFA were 82 and 197 respectively.

3.2. Measures

The focus of this study is the MSPSS which measures perceived support from family, friends, and significant others (Zimet et al., 1998). It includes 12 items: 1) There is a special person who is around when I am in need; 2) There is a special person with whom I can share my joys and sorrows; 3) My family really tries to help me; 4) I get the emotional help and support I need from my family; 5) I have a special person who is a real source of comfort to me; 6) My friends really try to help me; 7) I can count on my friends when things go wrong; 8) I can talk about my problems with my family; 9) I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows; 10) There is a special person in my life who cares about my feelings; 11) My family is willing to help me make decisions; and 12) I can talk about my problems with my friends. Respondents need to rate how they feel about each item using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Very strongly disagree” to 7 = “Very strongly agree”.

3.3. Data Analyses

First, univariate analyses were used to describe the average age and item scores of the two samples. Subsequently, EFA was conducted using SPSS 25.0 to preliminarily identify the underlying structure of PSS. Finally, the researcher performed CFA to test whether the data fit the model and test discriminant validity and convergent validity, using Amos 23.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptives

Table 1 showed the age and item scores of samples for EFA. The average age was 64.88 (

SD = 9.83). The mean scores of each item ranged from 4.99 to 5.37, indicating that the respondents moderately agree with these statements in general.

The descriptives of the sample for CFA were presented in

Table 2. The average age was 64.76 (

SD = 10.02). The mean scores of each item ranged from 5.28 to 5.73, indicating that the respondents moderately agree with these statements in general.

4.2. EFA Results

EFA was conducted on the 12 items of PSS. The researcher used two measures to test the fit between the data and the factor analysis to be conducted. The first measure, the Barlett Test of Sphericity (BTS), BTS = 1324.28, p < .001, which rejected the hypothesis that the correlation matrix was an identity matrix and showed that factor analysis was a proper statistical method for this data. The second measure was KMO. The obtained statistic was 0.90, which was a very good fit for the factor analysis method. Both tests indicated that EFA fit these data.

Principal axis factoring analysis with promax rotation was used in this study. After checking the scree plot, three distinct factors accounted for all the 12 items. These factors had initial eigenvalues between 0.84 to 8.67, explaining 85.84% of the variance (Factor 1 = 71.12%, Factor 2 = 8.72%, Factor 3 = 6.00%). Loadings and eigenvalues of each factor were presented in

Table 3. Items were included in a factor if their loading on that factor was larger than 0.4. Three factors were identified: Support from friends (Factor 1), Support from significant others (Factor 2), and Support from family (Factor 3). In this way, there were three subscales. Cronbach’s alpha of subscale 1—Support from friends was 0.97; of subscale 2 -- Support from significant others was 0.96; of subscale 3 -- Support from family was 0.94. All the three subscales had good reliability.

4.3. CFA Results

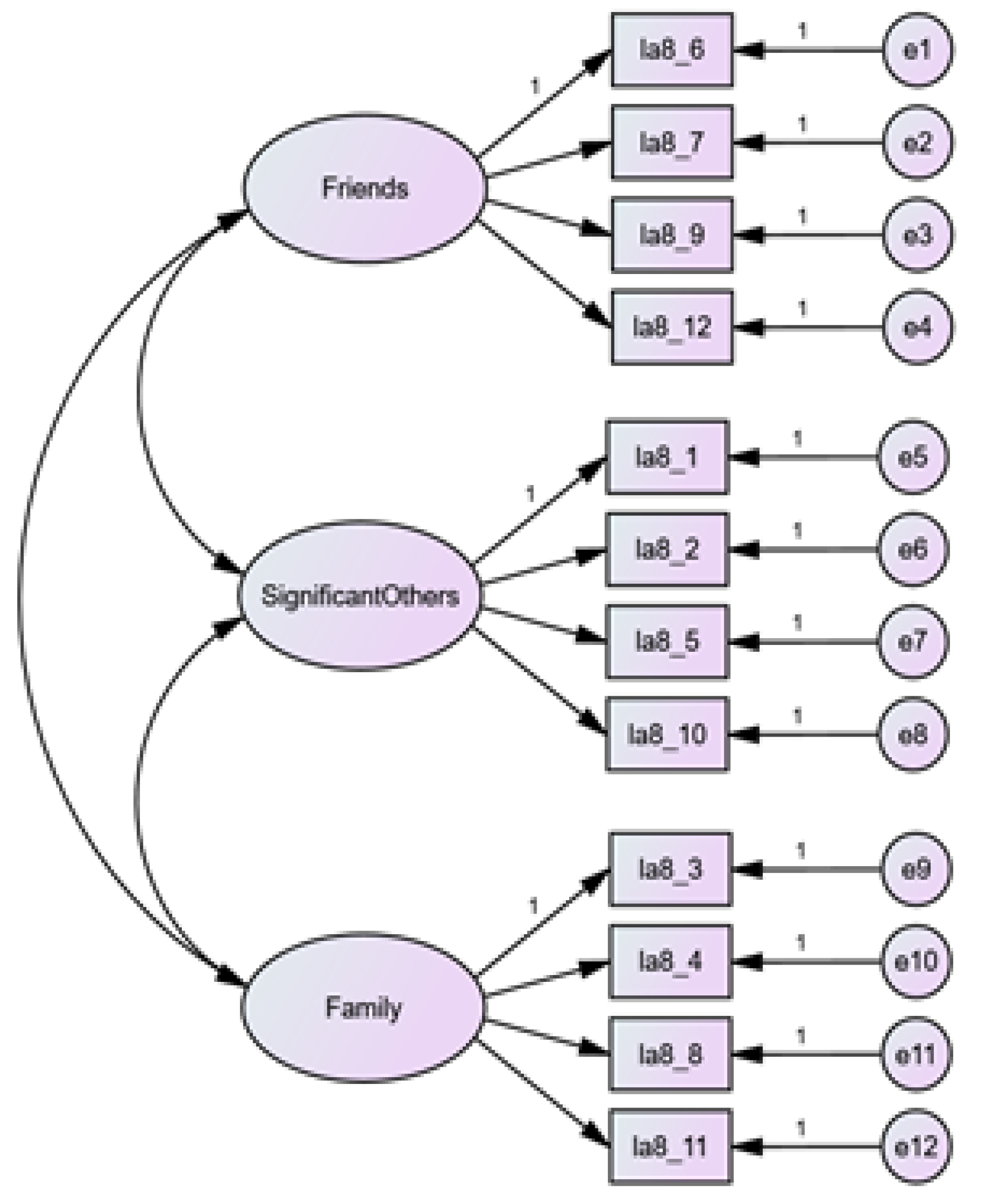

The measurement model was showed in

Figure 1. The confirmatory factor analysis of 12 items in 3 factors yielded a good fit (

χ2 = 183.870, df = 51,

p < .001). The value of CFI was 0.957 and of RMSEA was 0.110.

Table 4 showed that all the unstandardized factor loadings were significant, so none of the items need to be removed from the model. The standardized estimates of factor loadings were all larger than 0.6, which meant that they can very well reflect the latent variable.

Table 4 also presented the results about convergent validity test. The values of SMC were all above 0.36, indicating sufficient item reliability. Values of composite reliability were all above 0.7, which suggested a good internal consistency. All the values of AVE were above 0.5, showing that each construct closely correlates with related variables, i.e., good convergent validity.

Table 5 demonstrated the results of divergent validity. For each factor, the square root of each AVE was larger than the correlation coefficients between this factor and other factors. Take the factor of friends as an example, 0.931 was larger than 0.746 and 0.758. Therefore, it is believed that this scale had good divergent validity.

5. Discussion

This study validated the MSPSS for use with older adults following natural disasters, successfully confirming the instrument’s original three-factor structure measuring support from family, friends, and significant others. The robust psychometric properties—including high internal consistency (α = 0.94-0.97), strong factor loadings, and excellent convergent and discriminant validity—demonstrate the scale’s reliability in capturing distinct dimensions of perceived support within this vulnerable population. The preservation of these distinct support categories suggests that even amid disaster-related disruption, older adults maintain differentiated perceptions of their support networks, which carries important implications for both research and practice.

The validation enables more precise assessment of support sources, allowing practitioners to identify whether support deficits originate from family systems, friendship networks, or absence of significant others. This specificity facilitates targeted interventions such as family counseling, social connection programs, or partner support services. The generally high support levels observed may reflect either the “relational renewal” phenomenon where disasters strengthen community bonds, or possibly a resilience factor where better-supported individuals were more likely to participate in research. By providing a validated measurement tool, this study addresses a significant gap in disaster literature, enabling researchers to better investigate how perceived social support mediates recovery outcomes including trauma reduction, depression mitigation, and cognitive preservation in older survivors. While these findings establish the MSPSS as psychometrically sound for this population, further research should examine its applicability across diverse cultural contexts where family structures and support perceptions may vary significantly. Longitudinal studies tracking support patterns across disaster recovery phases would also strengthen understanding of how social support evolves over time. This validation represents an important step toward developing evidence-based, personalized support interventions that can enhance recovery and wellbeing for older adults affected by natural disasters.

6. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the findings are based on a sample from a single disaster type (tornado) in a specific geographic location (Dallas), which may limit generalizability to other disaster contexts and cultural settings. Second, while including adults aged 50+, the study did not stratify by narrower age groups or control for key demographic variables like socioeconomic status, ethnicity, or pre-existing health conditions, which may influence social support perceptions. Third, the cross-sectional design provides only a snapshot of support perceptions; a longitudinal approach would better capture how social support evolves throughout disaster recovery phases. Finally, while adequate for factor analysis, a larger sample size would permit more sophisticated analyses and enhance the stability of the results. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of response biases, such as social desirability or recall bias. The study also did not account for potential variations in disaster exposure intensity among participants, which could affect perceived support levels. The use of a convenience sampling method, while practical, may have resulted in a sample that is not fully representative of the entire affected older adult population, potentially overlooking the most isolated and vulnerable individuals. Furthermore, the study did not incorporate qualitative measures to provide richer context to the quantitative scores, which could have helped explain some of the nuances behind the perceived support ratings. Finally, the psychometric validation focused on the internal structure of the scale but did not assess other forms of validity, such as predictive validity against key mental health outcomes like PTSD or depression. Future research should address these limitations to further validate the MSPSS across diverse disaster-affected older adult populations.

7. Implications

There are several practical implications in this study. First the results of this study highlight how measuring perceived social support is important in disaster recover- both in the short term and long term. The previous literature in natural disasters indicates that perceived social support can reduce loneliness, help in overcoming trauma, and promote quality of life. Second, the development of interventions programs aimed at disaster recovery can help to alleviate the long-term psychological risks associated with being exposed to a natural disaster. Finally, as older adults are more vulnerable to isolation, educating the service providers and providing scales and tools that can assist in assessing their mental health are critical to providing meaningful connections- which can increase quality of life.

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support is a valid and reliable instrument. It can be used by gerontologists and natural disaster scholars alike for research purposes, for screening elderly who are at risk of low social support, developing emotional interventions for promoting it, understanding how older adults are coping with the aftermath of a natural disaster, and in evaluating outcomes of interventions. Moreover, social policymakers will be able to consider the different aspects of natural disaster planning in developing specific support programs for the elderly, unique to a particular country. As there is a lack of sufficient studies on the domain of the elderly’s perception of support after disasters (with scales designed based on cultural norms and social context), it is necessary to assess perceived social support under the current social conditions in each country.

References

- Antonucci, TC. (1990). Social supports and social relationships. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 1990, 3, 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA Social resources and cognitive decline in a population of older African Americans and whites. Neurology 2004, 63, 2322–2326. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolin, R., Bolton, P. (1986). Race, Religion, and Ethnicity in Disaster Recovery, University of Colorado, Boulder.

- Bonanno, G.A. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist 2004, 59, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G. A. , Brewin, C. R., Kaniasty, K., & Greca, A. M. L. Weighing the costs of disaster: Consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychological science in the public interest 2010, 11, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G. A. , Brewin, C. R., Kaniasty, K., & Greca, A. M. L. Weighing the costs of disaster: Consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychological Science in the Public Interest 2010, 11, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Canty-Mitchell, J. , & Zimet, G. D. Psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in urban adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology 2000, 28, 391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, K. E. , Silva Brown, J., Marks, L. D., Galea, S., Volaufova, J., & Lefante, C. Longitudinal assessment of cognitive and psychosocial functioning after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research 2015, 20, 27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Canty-Mitchell, J. & Zimet, G.D. Psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in urban adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology 2000, 28, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cohen S, Wills T Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bulletin 1985, 98, 310–357. [CrossRef]

- Cook, J., Bickman, L. Social support and psychological symptomology following a natural disaster, Journal of Traumatic Stress 1990, 3, 541-556.

- Drabek, T., Key, W. (1986). Mobilizing social support networks in times of disaster, Trauma and its Wake. Brunner/Mazel, New York.

- Erikson, K. Loss of Community at Buffalo Creek, American Journal of Psychiatry 1976, 133, 302–305.

- Goenjian, A.K. , Molina, L., Steinberg, A.M., Fairbanks, L.A., Alvarez, M.L., Goenjian, H.A., Pynoos, R. Posttraumatic stress and depressive reactions among Nicaraguan adolescents after Hurricane Mitch. American Journal of Psychiatry 2001, 158, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt-Lunstad, J. Why social relationships are important for physical health: A systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Annual Review of Psychology 2018, 69, 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt-Lunstad, J. , Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty, K. , & Norris, F. H. (2009). Distinctions that matter: Received social support, perceived social support, and social embeddedness after disasters. In Y. Neria, S. Galea, & F. H. Knight, B. G., Gatz, M., Heller, K., & Bengtson, V. L. Age and emotional response to the Northridge earthquake: A longitudinal analysis. Psychology and Aging 2000, 15, 627–634. [Google Scholar]

- Lakey, B. , & Cohen, S. (2000). Social support and theory. In S. Cohen, L. G. Underwood, & B. H. Gottlieb (Eds.), Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists (pp. 29–52). Oxford University Press.

- Norris (Eds.), Mental health and disasters (pp. 175–200). Cambridge University Press.

- Parker, G. , Lie, D., Siskind, D. J., Martin-Khan, M., Raphael, B., Crompton, D., & Kisely, S. Mental health implications for older adults after natural disasters—a systematic review and meta analysis. International Psychogeriatrics 2016, 28, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M. , MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar]

- Quarantelli, E.L. (1998). What is a disaster? Perspectives on the question. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Raphael, B. , Maguire, P. (2009). Disaster mental health research: Past, present, and future. In Neria, Y., Galea, S., Norris, F.H. (Eds.), Mental health and disasters. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Rodriguez-Laso A, Zunzunegui MV, Otero A The effect of social relationships on survival in elderly residents of a Southern European community: a cohort study. Geriatric Journal 2007, 7, 19–21.

- Seeman TE, Berkman LF Structural characteristics of social networks and their relationship with social support in the elderly: who provides support. Social Science Medicine 1988, 26, 737–749. [CrossRef]

- Thotis, P. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 2011, 52, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson D, Montez JK Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 2010, 51, 4–66.

- Zimet, G.D. , Powell, S.S., Farley, G.K., Werkman, S. & Berkoff, K.A. Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment 1990, 55, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zimet, G. D. , Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).