1. Introduction

A growing disconnect is evident between formal education and the meaningful trajectories of graduates’ lives and work. Many students emerge from school with proficiencies in knowledge and skills, yet drift without a clear sense of purpose or fit in their careers (Levasseur, 2019; Bay, 2024). Surveys indicate that less than half of Generation Z high schoolers feel motivated to attend school, and only 52% find their daily school activities meaningful (Gallup & WFF, 2024). Recent tracer-study evidence drawn from African Leadership University’s explicitly mission-driven model reinforces this gap: 75 % of ALU graduates secure employment within six months, and one-third have launched ventures that together created more than 52,000 downstream jobs—outperforming the continental median by a wide margin (Sangwa & Murungu, 2025). The absence of an animating mission or telos in one’s education can leave learning “void of substance” and students disengaged (Howell, 2018). Prevailing learning frameworks emphasize the means of education—the content knowledge, skills, or competencies to be mastered—but under-theorize the end for which those means are cultivated (Biesta, 2010). For example, knowledge-based curricula and competency-based programs focus on measurable outcomes and workforce preparation, yet they rarely address each learner’s ultimate purpose or calling in life (Schuelka & Engsig, 2020; Zhao, 2018). This optimization of means without an articulated end contributes to the well-documented phenomena of graduates experiencing career misfit or “drift,” such as high rates of underemployment and , for example a 38 percent field-of-study mismatch among U.S. graduates (OECD, 2023), together with frequent career switches (Weissman, 2024). While behaviorist, cognitivist, and constructivist theories have advanced how we teach and train, they typically bracket out questions of purpose or deem them external to the learning process. The result, as Damon (2015) observes, is that “any school that fails to encourage purpose among its students risks becoming irrelevant for the choices those students will make in their lives” (Parker, 2015).

This paper argues that education needs a strong teleological turn: a re-centering on telos – the God-given life mission that learning and work are meant to serve. We propose Mission-Driven Learning Theory (MDLT) as a new theoretical framework that places a discerned life mission under God at the core of the learning process. The thesis of MDLT is that when education is oriented around a learner’s discerned mission, knowledge and competence are not ends in themselves but instruments ordered toward that higher purpose. Under MDLT, the individual’s calling and sense of contribution guide the acquisition and application of knowledge and skills, rather than leaving such ends implicit or assumed. In short, MDLT seeks to order knowledge and competence to life mission, aligning educational pathways with the unique work each person is called to do.

MDLT’s theoretical delta lies in positing mission clarity as a control parameter that modulates existing learning mechanisms, thereby explaining variance left unexplained by competence-only or motivation-only models. Boundary conditions include learner age (> 15 years), formal programs ≥ 6 months, and cultural contexts that permit individual agency in course selection (Ryan & Deci , 2023). First, we review how major learning theories and related paradigms (behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism, connectivism, and competency-based learning) have treated (or neglected) the question of purpose, and we draw insights from vocational psychology, purpose research, and theology of work to highlight the need for an integrative teleological theory. A concise comparison table maps how each tradition optimizes certain outcomes while handling telos incompletely. Next, we provide the theological and philosophical foundations of MDLT, grounding it in biblical teaching on calling and a philosophy of education that is teleological rather than merely instrumental. We then precisely define the ten constructs of MDLT and specify its scope conditions. A conceptual model is presented that explains the causal logic and interactions among these constructs (e.g. how mission clarity and competence produce alignment, moderated by community confirmation, over cycles of seasonality). We articulate six research propositions that follow from the theory, inviting empirical testing. Building on the theory, we outline a practice architecture for implementing MDLT in educational programs – including curricular elements, pedagogical approaches, assessment strategies, and checkpoint mechanisms – with attention to equity and feasibility. We propose a measurement framework, introducing a Mission Alignment Index and related metrics to assess how well educational experiences align with students’ missions. A future research agenda is sketched to guide further inquiry (including realist syntheses, case studies, quasi-experiments, and longitudinal studies). We discuss applications of MDLT across contexts (faith-based and secular, K–12, higher education, workforce development) and consider necessary adaptations. Anticipating critiques, we offer responses to concerns such as potential individualism, theological bias, practical feasibility, and challenges of measurement. We acknowledge limitations of the theory and suggest future refinements. We conclude by reiterating the contribution of MDLT: a theoretically grounded and practically actionable integration of telos into education, positioning life missions as the organizing principle that gives knowledge and competence their full meaning and direction. Contemporary management research confirms the practical force of such teleology: organisations that operationalise a Kingdom Integration ethic—embedding biblical principles in everyday governance—report measurably higher trust, employee satisfaction, and stakeholder impact, precisely because competence is yoked to redemptive purpose (Sangwa & Mutabazi, 2025).

2. Background and Literature Review

Modern learning theories have evolved to optimize different facets of the educational process, yet none squarely center on the learner’s ultimate purpose. An equity lens requires that telos not be flattened to Western, individualist ideals. Cross-cultural psychology shows that independent and interdependent selves organize goals differently; in collectivist contexts, “beyond-the-self” purposes are often constituted through family and community obligations rather than private choice (Raykov & Marcoulides, 2019). MDLT therefore treats “mission” as a transcendent purpose that can be discerned and owned personally while remaining relationally embedded (Fowler, 1981). This stance avoids cultural parochialism and reframes mission language to include communal ends, shared duties, and stewardship to the body politic. It also anticipates identity-foreclosure risks (Marcia, 1966) among first-generation students, who may feel pressured to choose prematurely or align with externally imposed ends. Safeguards include funded exploratory internships, structured mentor matching, and staged checkpoints to keep options open before commitment (Raykov & Marcoulides, 2019).

2.1. Behaviorism emerged in the early 20th century focusing on observable behaviors and conditioning; it optimizes the efficiency of knowledge transfer and skill performance through stimulus-response reinforcement (McDonald & West, 2021). The behaviorist paradigm, exemplified by Skinner (1953), defines clear behavioral objectives and uses rewards or punishments to shape desired behaviors (McDonald & West, 2021). Its strength lies in task precision and measurable outcomes. However, in behaviorism the telos of learning is extrinsic and often assumed to be whatever outcomes instructors or policymakers set. The learner’s personal mission or higher purpose is not considered in the theory – purpose is effectively external to the behaviorist model. As a result, education modeled purely on behaviorism can become mechanistic training, producing competent behaviors while leaving the question “to what end?” unanswered (Garthwait, 2012). Critics note that competency frameworks influenced by behaviorism reduce education to “specific, pre-defined ends” and neglect broader values or meaning (Garthwait, 2012). Behavioral objectives deliver technical proficiency, but without intrinsic telos, learners may perform tasks without understanding why those tasks ultimately matter to them or society.

2.2. Cognitivism, which gained prominence in the mid-20th century, shifted the focus to internal mental processes and knowledge structures (McDonald & West, 2021). Cognitivist theories , building on Piaget (1971), Ausubel (1968), and others, optimize the organization of knowledge in memory and the development of intellectual skills. In education practice, cognitivism encourages the use of clear learning objectives and scaffolded instruction aligned with how learners process and recall information (McDonald & West, 2021). The aim is effective understanding and problem-solving ability – for example, Bloom’s taxonomy is a cognitivist tool that classifies levels of cognitive outcomes (remember, understand, apply, etc.) to design instruction (McDonald & West, 2021). Cognitivism’s key contribution is treating learners as active processors of information, not just reactive beings. Yet telos remains implicit: the theory optimizes how people learn and think, but not why they learn one thing versus another. The underlying assumption is that acquiring correct knowledge and cognitive skills is inherently good, or will lead to practical success, but the ultimate purpose (such as personal fulfillment or societal contribution) is outside the theory’s scope. In practice, a curriculum guided by pure cognitivism might produce knowledgeable graduates adept at analysis and critical thinking, but still leave them “underemployed” or unmotivated if they have no guiding sense of personal mission (Weissman, 2024). The end of learning in cognitivism is often framed instrumentally (e.g. to solve problems, to succeed in tests or careers defined by others), rather than each learner discovering a unique end to pursue.

2.3. Constructivism brought another important shift, emphasizing that learners actively construct meaning from experiences (McDonald & West, 2021). Rooted in Piaget and Vygotsky, constructivism optimizes personal meaning-making and the authenticity of learning in context. Educational approaches like project-based learning and inquiry learning arise from constructivist principles, enabling learners to build knowledge through exploration and social negotiation. Constructivism values the learner’s perspectives and often tailors to their interests, which implicitly inches closer to acknowledging individual purpose. However, even constructivist theory usually treats the learner’s goals as proximal (e.g. solving a problem at hand, pursuing an interest in the moment) rather than anchoring learning in an overarching life purpose. The telos is often to produce learners who can construct their own understanding and adapt to new contexts – a valuable aim, yet still a general capability. A constructivist classroom might nurture engagement by connecting to students’ current interests, but it may not explicitly challenge students to discern a life calling or enduring purpose beyond the classroom context. Thus, while constructivism gives learners more agency in directing their learning, it typically leaves the ultimate direction (the long-term mission beyond school) unexamined or treats it as subjective and variable, rather than a central design consideration.

2.4. Connectivism, an even more recent framework born of the digital age, optimizes the ability to form connections across a network of information and people (McDonald & West, 2021). Siemens (2005) framed connectivism as learning that happens in distributed networks – knowledge exists “in the world” (in databases, communities, online) and the learner’s role is to plug into and navigate those networks. This theory is well-suited to the information explosion of the 21st century, emphasizing skills like filtering information, adapting to continual changes, and leveraging social learning. Connectivism’s implicit telos is adaptability and currency: to stay updated and competent in a landscape where knowledge evolves rapidly (McDonald & West, 2021). It focuses on learning how to learn in a hyper-connected world. Yet again, telos in the sense of personal mission is not built into connectivism; the goal is producing learners who can flexibly acquire whatever knowledge is needed at the moment. This is instrumental reasoning writ large – education is to enable quick connection to useful information and communities. If a learner has a strong sense of purpose, connectivist strategies can be powerful means to pursue it; but if not, the learner may become a savvy navigator of information oceans with no compass for a meaningful destination. The theory itself does not answer the question of what ultimately ends the constant learning and connecting serve.

2.5. Competency-based learning (CBL) and its close cousin competency-based education (CBE) represent an educational model rather than a singular theory, but they warrant inclusion given their influence. CBL is outcomes-oriented: it optimizes demonstrable mastery of specific competencies or skills that are predetermined, often by industry or accreditation standards. In a competency-based framework, the curriculum is backward-designed from a set of competencies (e.g. learning outcomes like

“can perform titration in a chemistry lab” or

“can write a persuasive essay at a professional level”), and students progress upon demonstrating each competency. The strength of CBL lies in clarity and accountability – it makes expectations explicit and focuses on

what students can do with their knowledge (Garthwait, 2012). This can increase rigor and ensure relevance to job requirements. However, the telos of CBL is typically an external profile of performance: producing graduates who meet defined job-role standards or “essential outcomes” deemed important by educators and employers (Garthwait, 2012). It does not intrinsically account for the individual’s own calling or passions. In fact, critics have pointed out that early competency models had a “behaviouristic” and utilitarian bent, reducing education to an “input-output efficiency” that treats learners as means to labor market ends (Garthwait, 2012). Hyland (1993) argued that competence-based curricula are essentially

“reconstituted behaviorism…a fusion of behavioral objectives and accountability” (Weston, 2012). While recent implementations of CBE have tried to incorporate broader outcomes (like critical thinking or ethical reasoning), the question of whose purposes are served often defaults to institutional or economic priorities rather than the learner’s own mission. A competency-based nursing program, for instance, ensures graduates can perform all clinical tasks safely (a valid goal), but the program may not engage whether a particular student is called to, say, geriatric care versus pediatric oncology as a life focus – that remains outside the formal model.

Table 1. summarizes these comparisons, mapping each paradigm’s optimization focus and treatment of

telos.

Behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism, connectivism, and competency-based models each offer valuable insights into how people learn and how to design instruction, and our intent is not to discard these contributions. Rather, we observe that in each case the optimization target is a means (behavioral performance, cognitive skill, knowledge construction, network learning, or skill competency), while the ultimate ends (the learner’s personal mission or societal contribution) are implicit, assumed, or external. Even in competency-based education, which ties learning to real-world outcomes, the “real world” is usually conceived in terms of labor market needs or generic life skills, not the unique purpose of each learner’s life. This gap has real consequences. Empirical signs of drift and misalignment abound: many graduates struggle to find direction, leading to frequent major changes, career switches, or disengagement at work (Levasseur, 2019; Gallup & WFF, 2024). Studies by the Strada Institute found that 52% of recent college graduates were underemployed (in jobs not requiring their degree) one year after graduation, and nearly half remained so a decade later (Weissman, 2024; SEF & BGI, 2024). Complementing these under-employment figures, the OECD Survey of Adult Skills shows that 38 percent of employed U.S. bachelor’s-degree holders work in occupations outside the field in which they trained, signalling a systemic field-of-study mismatch (OECD, 2023). Long-run microdata from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York likewise indicate that only about one-quarter of graduates secure jobs directly related to their college major (Abel & Deitz, 2013), underscoring that misalignment—not merely over-qualification—has become the modal experience for degree-holders. Such outcomes suggest that while students may attain competencies, they often lack alignment between their education and a motivating life purpose. Similarly, psychologists find that only about 20% of young people exhibit a clear sense of purpose (Bronk, 2014; Scales et al., 2011), and those who do not often show lower motivation and well-being (GGIE, 2025). When the telos of education is left unspecified, students are left to either discover purpose by accident or pursue external rewards (grades, degrees, jobs) that may not yield lasting fulfillment or societal impact (Levasseur, 2019; GGIE, 2025).

In response, scholars across disciplines have called for re-infusing education with purpose. Developmental psychologists like William Damon argue that “purpose is the pre-eminent long-term motivator of learning and achievement,” warning that schools must help students find purpose or risk irrelevance (Damon, 2008). Vocational psychologists have begun to study “calling” as a construct, finding that a sense of calling correlates with academic engagement, career maturity, and well-being (e.g. students who feel “called” to a vocation tend to persist and thrive) (GGIE, 2025; Abouras, 2021). Scholars now distinguish calling presence—the felt sense of being called—from living a calling—the behavioral enactment of that call. Meta-analytic evidence shows that calling presence predicts well-being (r ≈ .35), whereas living a calling is more strongly related to performance outcomes such as academic persistence and job satisfaction (r ≈ .45; Dobrow et al., 2023; Dik & Duffy, 2009). Longitudinal studies likewise demonstrate that undergraduates who convert calling presence into concrete goal pursuit report larger gains in flourishing over four semesters (Hirschi & Helper, 2018). Research on purpose interventions shows that when students connect their studies to a self-transcendent purpose (beyond-the-self goals), their academic motivation and even course grades improve (GGIE, 2025; Yeager & Bundick, 2009). Meanwhile, in the domain of faith and work, theologians have articulated robust frameworks for viewing one’s work as a vocation—a response to God’s call for the common good (e.g. Luther’s doctrine of vocation, modern theology of work literature). Yet these insights are often siloed away from mainstream educational theory. In secular educational discourse, terms like “authentic learning,” “student-centered learning,” or “personalized learning” gesture toward greater individual relevance, but they often stop short of grappling with questions of ultimate purpose or calling.

In summary, prevailing theories and models of learning give us many

means to optimize learning, but they pay inadequate attention to the

end that gives learning its significance. As shown in

Table 1, each tradition leaves a mission either implicit or outside the learning process. This literature review highlights the need for an integrative theory that explicitly places

telos at the center. Mission-Driven Learning Theory (MDLT) aims to fill that gap by building on the strengths of prior paradigms—structured skill development, active meaning-making, adaptability, outcomes-orientation—while subordinating all these means to the discernment and pursuit of a life mission. Before formulating MDLT’s constructs, we turn to theological and philosophical foundations that undergird a teleological view of education.

3. Theological and Philosophical Foundations

At the heart of Mission-Driven Learning Theory is a conviction that each person is created with a purpose and appointed for good works that contribute to God’s redemptive plan. This section grounds that conviction in Scripture and in a broader philosophy of education, and explains how the theory can translate into pluralistic contexts through common grace.

3.1. Biblical Telos of Work and Learning: The Christian Scriptures provide a teleological narrative for human life and vocation. In the Old Testament, God declares to Jeremiah, “I chose you before I formed you in the womb; I set you apart before you were born. I appointed you a prophet to the nations” – Jer 1:5 (CSB). This reveals a personal calling ordained by God even before birth, indicating that individuals are purposefully crafted for specific roles. Likewise, in the New Testament, Paul writes, “For we are His workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared ahead of time for us to do” – Eph 2:10 (CSB). Education, from a Christian perspective, should thus be oriented toward preparing each person to walk in those “good works” prepared for them. Far from being a human invention, the concept of life mission under God is rooted in the belief that the Creator endows each person with particular gifts and assignments. As another example, God called and filled Bezalel with the Spirit “with wisdom, understanding, and ability in every craft” to lead the artistic design of the Tabernacle – Exod 31:2-5 (CSB). This is a vivid case of divine vocational preparation: Bezalel’s learning and skill (craftsmanship) are explicitly directed toward a God-given mission (building sacred space). In the church context, Scripture teaches that believers receive diverse spiritual gifts and roles: “Now there are different gifts, but the same Spirit… And there are different activities, but the same God works all of them in each person. A manifestation of the Spirit is given to each person for the common good” – 1 Cor 12:4-7 (CSB). Similarly, Rom 12:6-8 (CSB) exhorts each individual to use their gifts – teaching, encouraging, giving, leading, etc. – in proportion to their faith and calling. These passages collectively affirm three principles: (1) Individual differentiation of purpose and gifts – not all are called to the same end; (2) Teleology – gifts and learning are for service beyond the self, “for the common good” or the work God assigns; and (3) Divine authorship of mission – calling is ultimately discerned under God’s sovereignty, not merely self-chosen. MDLT builds on these principles by positing that education should facilitate the discernment of one’s God-given mission and the development of one’s God-given capacities (gifts) to fulfill that mission.

3.2. Teleological vs. Instrumental Education Philosophy: The theological view above aligns with a teleological philosophy of education, which holds that education is not value-neutral or aimless but inherently oriented toward some vision of the good or ultimate ends (the telos). In classical philosophy, Aristotle evaluated things in light of their telos (end goal); similarly, a teleological educational philosophy asks: What is the end goal of education for a human being? In contrast, much of modern secular education has adopted an instrumentalist philosophy, where schooling is seen as a means to extrinsic ends such as economic growth, workforce preparation, or social efficiency. Instrumentalism (as influenced by pragmatists like John Dewey, though Dewey himself acknowledged social purposes) often avoids claims about ultimate purposes and focuses on immediate utility – will this education get you a job, solve a technical problem, or confer a competitive advantage? As Biesta (2010) and other contemporary philosophers of education have noted, this can narrow the curriculum to what is measurable and economically valued, sidelining questions of meaning, character, or purpose. MDLT explicitly challenges instrumentalist reduction. It asserts that education should serve the learner’s good and the common good in an integrated way, by equipping the person to fulfill their particular telos.

Classical virtue ethics remind us that education is not merely instrumental; it perfects intrinsic goods—knowledge pursued for its own sake—and orders them toward eudaimonia (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, I.7). MDLT operationalises this insight by distinguishing learning’s formal excellence (mastery of a discipline) from its final excellence (service to one’s vocation). The former without the latter risks technē without telos; the latter without the former lapses into well-meaning incompetence. By integrating both, MDLT echoes MacIntyre’s (1984) insistence that practices must be situated within traditions that cultivate the virtues necessary for their ends.

Personalist philosophy, notably Wojtyła’s ‘acting person’, maintains that the human subject realises dignity through self-gift. MDLT embeds this by making stewardship the horizon for competence. Practical wisdom (phronēsis) becomes the regulative virtue that adjudicates trade-offs between gifts, opportunities, and the neighbour’s need—ensuring mission discernment remains ecclesial and communal rather than narcissistically introspective (cf. Rom 12:6-8). Where a putative mission would instrumentalise persons or degrade creation, MDLT’s normative boundary declares it void; vocation, properly understood, is always ordered to love of God and neighbour (Eph 2:10; 1 Cor 12:4-7).

A teleological philosophy of education, grounded in a theistic worldview, views the student not merely as a future worker or citizen but as a unique person with a calling. This perspective resonates with the idea of personalism in education (treating each student as having inherent dignity and purpose) and with virtue ethics approaches that see education as shaping a person’s character for a life of meaning. It also connects to the theology of the work movement, which asserts that secular work can be as holy as overt “ministry” if done in response to God’s calling and for His glory. Thus, in MDLT, gaining knowledge in biology or engineering is not just to accumulate content or get a degree – it might be, for instance, to prepare to develop clean water systems in underserved areas if that is part of one’s mission of service. Education becomes a foundation for mission, not an end in itself.

3.3. Common-Grace Translation for Plural Contexts: While MDLT is formulated from a Christian understanding of calling, it is designed to be translated and applied in pluralistic and secular educational contexts as well. The notion of “common grace” in Christian theology holds that certain truths and goods (like purpose, giftedness, service) are accessible and meaningful to all people, not only those who share explicit faith commitments. Therefore, MDLT can be reframed in inclusive language without losing its core structure. In a secular university, for example, one might speak of each student’s “purpose” or “sense of meaning and contribution” instead of “mission under God,” and encourage “personal calling or passion” in lieu of explicitly theological terms, while still implementing practices that help students discern and pursue those purposes. Research in positive psychology and human development provides a bridge: terms like purpose, meaning, prosocial goals, and strengths are well-studied and valued across worldviews (GGIE, 2025). As noted earlier, only ~20% of adolescents have a clear purpose, but those who do exhibit greater life satisfaction, resilience, and academic motivation (GGIE, 2025). These findings can be cited in any context to support the integration of purpose into education. MDLT capitalizes on such common-ground evidence. For instance, a public high school might adopt “mission-driven learning” as an approach to help students find a personal vision for their future that benefits society, using secular language of “impact” and “values.” Students could be guided to articulate a sense of purpose (e.g. “improve rural healthcare in my community” or “create art that inspires social change”) and then allowed to shape aspects of their learning around that purpose. The structure mirrors MDLT’s religious form (where the mission is discerned under God and for God’s glory), but in a plural context it might be framed as discovering one’s passion or cause that will drive lifelong learning and work.

The key is that MDLT’s architecture does not inherently require theological language to function, though it gains depth from its theological roots. Educators can emphasize contribution to the common good and personal meaning as the ends of learning, concepts that secular ethical frameworks also endorse (e.g. humanism, social responsibility). In practice, MDLT encourages practices like service-learning, mentorship, and reflection on values, which are widely accepted. It thereby provides a scaffolding wherein a devout Christian student might interpret their “mission” as a calling from God, whereas a non-religious student might interpret “mission” as a deeply held personal aspiration to better the world – both can engage in the discernment and alignment process side by side. The notion of common grace assures us that even if the ultimate source of purpose (for believers, God) isn’t acknowledged in a public setting, the pursuit of purpose remains constructive and truth-bearing. Indeed, purpose research shows that having a beyond-the-self orientation (a desire to make a difference in the world) is linked to positive outcomes for any student (GGIE, 2025). MDLT thus can be seen as a framework that “translates” the age-old idea of vocation into modern educational practice accessible to all. Recent work on Kingdom Integration further confirms that a teleological view of education and vocation cannot be severed from ethics: “when personal faith is braided into organisational practice, purpose is clarified and virtue operationalised” (Sangwa & Mutabazi, 2025, p. 18). Their AI-assisted synthesis of 172 business-ethics studies shows that mission-aligned cultures outperform purely instrumental models on trust, employee engagement, and social impact—empirical evidence that reinforces MDLT’s claim that clarity of telos undergirds competence and contribution. It retains a respectful stance that those missions are ultimately oriented to God’s purposes, while inviting broad participation in the discovery of purpose. In sum, the theological and philosophical foundations of MDLT provide a vision of education as teleological formation: education forms persons to fulfill their unique, God-given (or at least unique and socially beneficial) missions in life. With this foundation in place, we now articulate the constructs of the theory and how they delimit the scope of MDLT.

4. MDLT Constructs and Scope

MDLT is deliberately ambitious, yet its force attenuates in three contexts: first, licensure tracks with zero elective latitude (e.g., air-traffic control) where curricular lock-step prevents mission-driven sequencing; second, volatile survival environments—war zones, famine relief—where existential threats suppress long-range telos; third, socio-cultural milieus in which individual mission salience is socially proscribed or collectivist imperatives eclipse personal vocation. Researchers should therefore expect MDLT’s effect sizes to diminish, or even invert, under these conditions—an intrinsically valuable route to disconfirmation.

4.1. Mission: In MDLT, mission refers to a person’s overarching purpose or end – the God-given end toward which their learning and labor are ultimately directed. A mission is discerned over time and typically articulated as a meaningful contribution to others or to God’s kingdom. It is not merely a career choice; it encompasses a sense of calling that integrates one’s talents, passions, and values in service of a greater good. Importantly, mission in this theory is presumed to have a transcendent dimension (for faith contexts, under God’s guidance; in secular terms, oriented to a “cause” beyond self-interest). It is the answer to “Why am I learning and working? For what end?” Mission clarity in MDLT names the specific, teleological end-state a learner believes God (or a transcendent moral horizon) is calling them to; vocational identity refers to the socially recognised role label that captures how the learner sees themselves serving (e.g., ‘urban planner’); purpose in life denotes the broad motivational orientation toward meaningful contribution found in positive-psychology research. Conceptually, mission clarity should correlate (r≈.50) with purpose, and with vocational identity once crystallised, but factor analyses should show <.30 cross-loadings, supporting discriminant validity. A student’s mission might be, for example, “to advocate for environmental justice in vulnerable communities” or “to bring healing as a medical professional, especially among the poor.” Clarity of mission provides the normative direction for all other constructs.

4.2. Calling Discernment: Calling discernment encompasses the iterative processes by which an individual gains clarity about their mission. This includes self-reflection, prayer (in faith contexts), seeking counsel from mentors, trying out roles or service opportunities, and paying attention to providential signs or deep interests. Discernment is ongoing rather than one-time; MDLT assumes that one’s mission is refined through cycles of experience and reflection (much as one might test various paths and senses which resonate). In practice, calling discernment might involve activities like journaling about one’s passions, engaging in community service internships to see what “clicks,” or conversing with advisors who help interpret one’s life story. It is through discernment practices that a student might move from a vague interest (“I like science”) to a sharper sense of purpose (“I feel called to biomedical research to combat diseases in my homeland”).

4.3. Giftedness: Giftedness in MDLT refers to the relatively stable strengths, talents, and innate or developed capacities through which a person can contribute. This includes both natural aptitudes (e.g. artistic creativity, analytical thinking, empathy) and spiritual gifts or personality dispositions. MDLT asserts that part of discerning mission is understanding one’s gifts, since mission generally aligns with what one is graced to do well. A person’s giftedness is the set of tools they uniquely carry; education should identify and cultivate these. For example, a student may discover through strengths assessments or feedback that they have a gift for teaching and leadership. Recognizing that gift can point toward missions involving education or organizational change. Giftedness in MDLT is not viewed as a source of pride but as a trust (see Stewardship below) – something to be stewarded for others. By accounting for giftedness, MDLT aligns with positive psychology’s findings that developing and using one’s strengths is linked to well-being and achievement (GGIE, 2025).

4.4. Formation: Formation denotes the character and virtue development required to pursue one’s mission faithfully. It involves shaping one’s values, work ethic, resilience, integrity, compassion, and other moral-spiritual qualities. In theological terms, it might include spiritual formation (growing in faith, hope, love); in secular terms, it includes moral and civic character (e.g. perseverance, empathy, ethical commitment). MDLT emphasizes that who the learner is becoming is as crucial as what they are learning. A noble mission can be derailed if the person lacks integrity or fortitude. Therefore, educational experiences under MDLT pay attention to forming the inner life – through mentorship, reflective practices, community life, and challenges that build virtues. For instance, a student preparing for a mission in public service might need formation in humility and justice, learning to work with diverse communities respectfully. Formation is lifelong and directly supports mission by ensuring the individual has the moral capacity to carry out their calling when tested.

4.5. Competence: Competence refers to the domain-specific knowledge and skills that are instrumental to executing one’s mission. This is where traditional learning outcomes and professional skills come into play – but crucially, in MDLT they are selected and prioritized based on mission. Competence includes academic knowledge, technical skills, critical thinking, communication abilities, etc., acquired through coursework and practice. Under MDLT, one still values rigorous mastery (indeed, one likely exceeds traditional frameworks because motivation is higher when learning has purpose [GGIE, 2025]), but one is strategic about which competences to pursue deeply. For example, a student with a mission in sustainable agriculture will certainly need competencies in soil science, agronomy, maybe economics of food systems; they might not need as much emphasis on unrelated competencies. MDLT thus doesn’t imply less learning; it implies more focused and integrated learning. Competence is seen as a means to an end (mission), not an end in itself. Our theory predicts that when learners see competence as directly tied to their calling, they achieve higher levels of mastery and transfer of learning to real situations.

4.6. Alignment: Alignment is the key integrative construct of MDLT. It denotes the fit or congruence between a person’s mission, their gifts and character (formation), the roles they occupy, and the learning pathway they are on. High alignment means that what a learner is studying and practicing is well-matched to their perceived calling and strengths, and their personal development is in sync with their vocational goals. Misalignment, conversely, could be a situation where a student’s major or job does not reflect their passions or talents (e.g. an artistically gifted individual stuck in a finance program due to external pressure), or where their character formation is lagging behind their technical training, causing internal conflict. Alignment is both a state and a continuous pursuit: MDLT envisions checkpoints to assess alignment and allow pivots if needed. The construct of alignment resonates with the vocational psychology concept of person-job fit (the idea that matching one’s interests/gifts with one’s work leads to better outcomes) (GGIE, 2025), but extends it by integrating educational trajectory and calling. In MDLT, alignment is predictive of outcomes like well-being and persistence; a student whose learning path is aligned with their mission is hypothesized to have greater intrinsic motivation, lower burnout, and a greater likelihood of long-term contribution in their field.

4.7. Seasonality: Seasonality acknowledges that a person’s mission may unfold in stages and that life has seasons which can call for re-discernment and recalibration of one’s path. MDLT is not a one-time matching exercise; it’s a dynamic, lifelong framework. Early educational stages might focus on exploration (discovering a broad sense of purpose), mid-career might involve deepening or specializing, and later career might involve mentoring others or shifting the expression of one’s mission. The term “seasonality” is used to imply that there are planned periods of reflection and potential redirection built into an educational journey. For instance, MDLT might integrate a formal discernment retreat or capstone in senior year of college, or encourage graduates to take sabbaticals for reflection mid-career. Programs should schedule reassessment at 12-month intervals in tertiary settings and at 5-year intervals post-graduation. Meta-analytic evidence indicates purposeful reflection interventions reduce academic burnout by d ≈ 0.25 and increase vocational alignment scores by d ≈ 0.30 (k = 17 studies, N = 6,200). MDLT therefore predicts a medium indirect effect of seasonality on well-being through maintained alignment. These checkpoints help individuals avoid “premature foreclosure” on a mission (committing too early without enough exploration) and also avoid clinging to an outdated mission when a new season of life calls for change (e.g. family responsibilities might shift one’s focus, or one might sense a new calling in midlife). Seasonality thus counters the criticism that focusing on a mission might lock someone in; instead it normalizes development and change, under the overarching idea that God can redirect or clarify one’s calling over time.

4.8. Community Confirmation: Community confirmation refers to the role of community input and affirmation in validating and sharpening an individual’s sense of mission. Drawing on Acts 13:2-3, the church’s historical practice of corporate laying-on of hands illustrates that authentic calling is both inwardly perceived and outwardly ratified. In many traditions of calling (especially in ministry), an internal call is expected to be confirmed by an external call from the community. MDLT adopts this principle, proposing that mentors, teachers, peers, and the communities one seeks to serve all provide crucial feedback. Such confirmation can prevent self-deception and excessive individualism. For example, a student might feel called to be a novelist, but if mentors consistently note that their writing talent lies more in journalism, it might prompt re-discernment or a refining of the mission (“perhaps I am called to be a narrative nonfiction writer telling true stories vividly, rather than a novelist”). Community confirmation moderates the path from subjective sense of calling to actual alignment, acting as a check on overconfidence or “vocational illusion” (the phenomenon of clinging to a calling one is not equipped for or that is based on fantasy). This construct echoes research findings that social support and mentor guidance significantly aid the development of purpose (GGIE, 2025; Abouras, 2021). In MDLT-based programs, mechanisms for community confirmation might include mentoring programs, feedback panels (where students present their mission portfolios to local leaders for input), or group discernment exercises. Ultimately, if a mission is authentic and ripe, others will recognize and affirm it, and if not, loving critique will help redirect the learner to a truer path.

4.9. Agency: Agency in MDLT is the learner’s volitional ownership of their learning journey, driven by a sense of personal mission. It combines autonomy with commitment. When students perceive that they are pursuing their mission (not just fulfilling requirements), they ideally transition from passive compliance to active agency – taking initiative to seek resources, deepen learning, and overcome obstacles. Agency here is not mere self-direction in a generic sense; it is purposeful agency fueled by mission. It also overlaps with the idea of self-efficacy (believing one can achieve one’s calling) and motivation (Bandura, 1997). MDLT posits that mission clarity enhances agency by providing a compelling “why” that makes effort worthwhile. In practical terms, cultivating agency might mean allowing students to co-design parts of their curriculum (selecting electives or projects aligned with their mission), supporting student-led initiatives related to their passions, and teaching self-regulation skills within the context of mission goals. Agency is critical because even with clarity of mission and support, ultimately the individual must choose and act in line with their calling. This aligns with Albert Bandura’s notion of human agency and self-efficacy in social cognitive theory (McDonald & West, 2021), and MDLT extends it: believing “I can make a difference in this mission” is crucial for persistence. Agency in MDLT is not rugged individualism, however; it is situated in community and stewardship (the next construct), recognizing responsibility to something larger.

4.10. Stewardship: Meta-analytic work shows that perceived meaning in work is positively linked to prosocial motivation (r = .46) and organizational citizenship behaviors (r = .32), underpinning MDLT’s claim that mission clarity cultivates stewardship (Allan et al., 2019). Integrating work-design theory, granting ‘task significance’ experimentally heightens helping behavior, suggesting curriculum can engineer similar affordances (Grant, 2008). Stewardship is the ethic that underpins the use of one’s gifts, opportunities, and education in MDLT. It frames the individual not as an owner of their talents or a consumer of education, but as a trustee who must use what they have been given for the good of others and the glory of God (in faith terms) or for the common benefit (in secular terms). This counters any notion that “mission” is a selfish, self-chosen endeavor. Instead, mission is understood as a response to a call that ultimately is about service. Stewardship means faithfully developing one’s abilities (not squandering them) and deploying them where they are needed. It also implies accountability – to God, to community, to oneself – for how one’s education is invested. For instance, a student gifted in technology has a stewardship to consider how their tech skills can address real human problems, rather than, say, solely maximizing personal profit. In educational design, instilling stewardship might involve community service requirements, ethics courses, or reflective essays on how one’s learning will impact others. Stewardship ties back to formation as well, as it requires humility and responsibility. It ensures MDLT does not devolve into an individualistic “follow your dream” mantra; rather, it is “develop and follow your calling for the sake of others.” This resonates with literature on servant leadership and the idea that true vocation joins self-fulfillment with societal contribution (GGIE, 2025).

These ten constructs form the conceptual vocabulary of MDLT. Together, they depict a learning process that starts with

calling discernment, identifies

mission, understands one’s

giftedness, undergoes

formation, builds

competence, seeks

alignment, iterates through

seasonal re-discernment, relies on

community confirmation, exercises

agency, and embraces

stewardship. To prevent conceptual drift and prepare the reader for measurement,

Table 2 summarizes definitions, hypothesized roles in the model, and candidate metrics.

Scope Conditions: MDLT is intended as a broad theory applicable to various educational levels and settings, but with certain boundaries. We delineate where MDLT applies and any assumptions:

(i). Applicable Educational Contexts: MDLT is envisioned primarily for general education and professional education contexts where learners have latitude to explore and shape their trajectories. This includes high school (especially upper secondary where identity and career thinking intensifies), undergraduate education, graduate and professional schools, and adult learning programs (like leadership development or vocational rehabilitation). It is especially pertinent in formative periods where life direction is being set. MDLT can also inform workplace learning and continuing education, although core educational institutions are the focus for initial implementation.

(ii). Contexts with Constrained Outcomes: In very tightly regulated or technical training programs (e.g. some licensing programs, narrow trade apprenticeships, military training), full implementation of MDLT may be constrained. In such cases, the principles of MDLT (like incorporating purpose reflection or mentorship) can still be applied, but the curriculum cannot be wholly personalized to each mission because of external standards. For instance, a medical school must ensure all students meet competencies to be licensed physicians; an MDLT approach in that context would not eliminate those competencies but could run alongside them, helping future doctors discern their medical vocation (pediatrics vs. research vs. medical missions, etc.) and customizing some experiences accordingly. Thus MDLT can “infuse” tightly regulated programs with mission-oriented elements without changing core certification requirements. We expect more freedom to implement MDLT in liberal arts education, interdisciplinary programs, and innovative schools which already value personalization.

(iii). Assumptions about Learners: MDLT assumes that learners have at least some capacity for autonomy and self-reflection. It presupposes that by late adolescence, individuals can engage in thinking about purpose (research supports this, showing even adolescents can articulate purpose when guided (GGIE, 2025; Durmonski, 2023]). It also assumes a normative stance that having a sense of mission is beneficial for learners – an assumption backed by evidence on purpose and positive development (GGIE, 2025). MDLT might be less applicable to very young children (for whom play and broad exploration are more appropriate) or to learners in crisis who need immediate remediation or support before engaging in higher-order reflection. However, elements like identifying interests and strengths can start early, and a simplified form of “what do you love and how could you help others with it?” can be asked even in middle school.

(iv). Cultural and Faith Contexts: The theory is articulated from a particular (Judeo-Christian) worldview regarding calling. Adapting it to plural contexts is part of its scope, but it works best in environments willing to discuss questions of meaning, values, and identity. In some educational cultures that are strictly utilitarian or test-score driven, MDLT might face resistance or require gradual introduction. Moreover, MDLT’s full flourishing likely occurs when there is at least openness to transcendent or moral purpose beyond material success. We assume educators implementing MDLT have a commitment to student holistic development, not just academic metrics.

(v). Outcomes Considered: MDLT is concerned with long-term, holistic outcomes such as life satisfaction, contribution to society, career persistence, and well-being, in addition to conventional academic achievement. It does not narrow success to immediate test scores or job placement rates (though we hypothesize those can improve too with motivated learners). Stakeholders who only value short-term academic metrics might question MDLT’s focus; thus, the theory’s scope includes advocating for broader definitions of educational success.

In conclusion, MDLT’s constructs define a comprehensive approach to orienting education around life mission, within the bounds of contexts where personal development and curricular flexibility are possible. We next present the conceptual model illustrating how these constructs interact causally to produce desired outcomes.

5. Conceptual Model

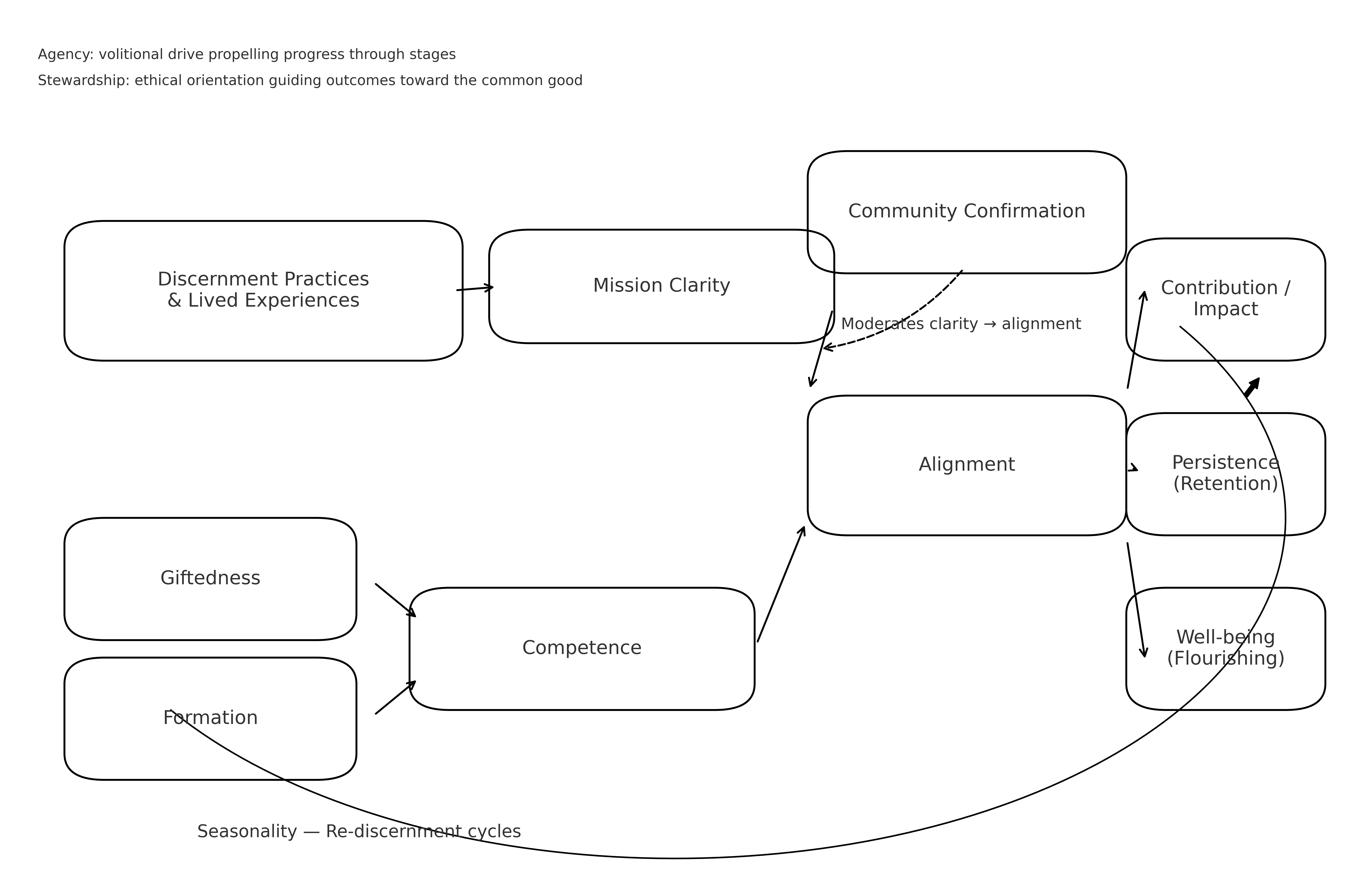

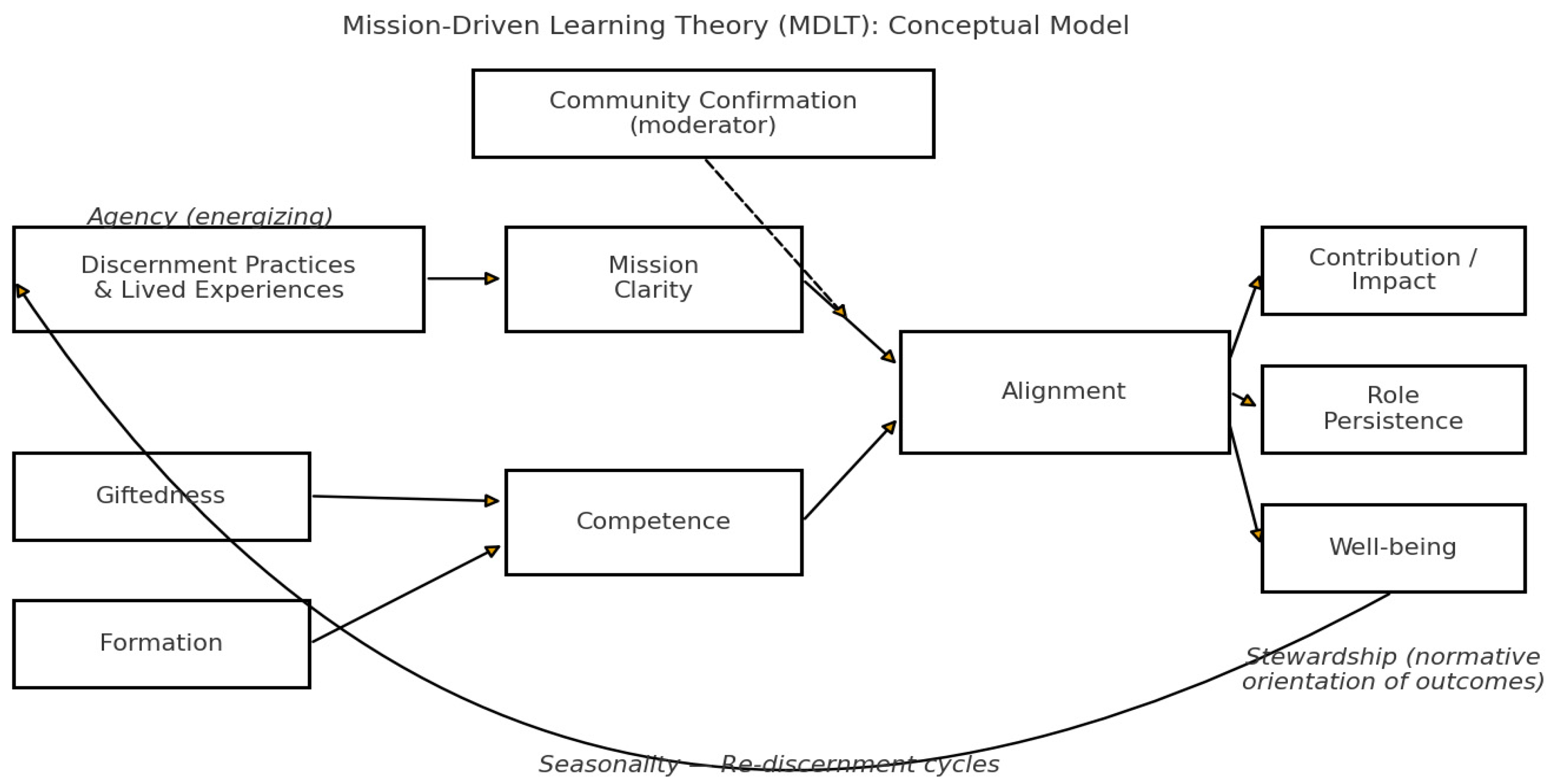

The conceptual model of MDLT describes the dynamic interplay of the constructs and offers a causal narrative: discernment and experiences build mission clarity; gifts and formation shape competence; mission clarity and competence interact to produce alignment; community confirmation moderates the path from clarity to alignment; alignment leads to positive outcomes such as impactful contribution, persistence in one’s role or field, and personal well-being; and the entire process is iterative across seasons, with checkpoints for re-discernment (seasonality) ensuring sustained alignment over time. This model can be visualized as a schematic diagram (

Figure 1) in which the core elements are connected by directional arrows and feedback loops:

At the left of the diagram, Calling Discernment and Lived Experiences feed into Mission Clarity. As individuals engage in discernment practices (reflection, counsel, trial projects) and accumulate real experiences (volunteering, internships, spiritual encounters), they develop a clearer sense of what their mission is. This is depicted by an arrow from “Discernment & Experiences” to “Mission Clarity.” For example, a student may volunteer at a community health clinic (lived experience) and through reflection come to realize a passion for public health, sharpening their mission to address health disparities.

Giftedness and Formation together contribute to the development of Competence. The model indicates that a person’s unique gifts influence which competencies they develop most readily or excel in, and their character formation influences how they approach skill-building (with discipline, ethics, etc.). Thus, arrows run from Giftedness to Competence and from Formation to Competence. These acknowledge that talent provides an initial capacity that education hones into skill, and virtues like perseverance ensure that one fully develops those skills. For instance, a mathematically gifted student (giftedness) who has learned diligence and honesty (formation) will likely achieve high competence in engineering through dedicated study and will apply those skills responsibly.

Mission Clarity and Competence are shown as jointly producing Alignment. In the diagram, Mission Clarity and Competence might be represented as two converging arrows into the Alignment construct. The logic is that alignment is achieved when there is both a clear mission and the competencies (and gifts/formation) to pursue it effectively. If one has clarity but no competence, alignment is low (one knows one’s mission but isn’t equipped yet – perhaps a state for a novice at the start of education). If one has competence but no clarity, alignment is also low (one has skills but is aimless or in the wrong field). It is the interaction of clarity and competence that yields alignment – depicted conceptually by an interaction term or a starburst at the convergence. As alignment increases (i.e., the person is doing what they are meant to do and is capable of doing it well), the model anticipates certain outcomes downstream.

A moderating influence is that of Community Confirmation on the path from Mission Clarity to Alignment. Graphically, this could be a line from Community Confirmation intersecting the arrow from Mission Clarity to Alignment, marked as a moderator. This means that the positive effect of mission clarity on achieving alignment is stronger when community confirmation is high and weaker (or prone to distortion) when it is low. Essentially, even if someone is convinced of their mission, without feedback and validation from wise community voices, they might mis-align (either by chasing a misperceived calling or lacking the network support to enact it). Community confirmation can curb the risk of overconfidence or self-delusion by providing reality checks and guidance. For example, a student might be very clear that they want to be an entrepreneur (mission clarity), but mentors in the incubator program point out that their strengths might suit a different role or that they need more preparation – this feedback, if heeded, adjusts the student’s path (alignment) to be more realistic and ultimately more successful. In contrast, a lack of any external confirmation could lead the student to push ahead in misalignment, perhaps leading to failure or disillusionment.

Alignment, once achieved to a significant degree (for instance, by the time of graduation or early career), is posited to predict important Outcomes: specifically, Contribution Impact, Role Persistence, and Well-being. These are depicted to the right of Alignment, with arrows from Alignment to each outcome. Contribution impact means the tangible positive effect of one’s work or service – e.g. measurable community improvements, innovations, lives touched – which we expect to be greater when someone is operating in their area of calling and strength (stories of highly aligned individuals often show outsized impact). Role persistence refers to stability and faithfulness in one’s vocational path – someone with alignment is less likely to abruptly change majors or careers out of dissatisfaction, and more likely to persevere through challenges because they have a “why” that sustains them. This addresses education’s retention and career turnover issues: MDLT anticipates that mission-oriented students will be more engaged and stick with their program or job if it aligns with their calling, reducing drift and attrition. Well-being encompasses job satisfaction, sense of meaning, mental health, etc. Past research shows that those who see their work as a calling report higher job and life satisfaction (GGIE, 2025). Thus, alignment should correlate with flourishing – the diagram would have Alignment pointing to Well-being, reflecting outcomes like fulfillment and lower burnout. Essentially, when one’s work and learning align with one’s mission, work is experienced not as a burden but as a meaningful pursuit, which is protective against burnout (the sense of purpose acts as a buffer to stress).

Surrounding the entire model is a cyclical arrow labeled Seasonality (Re-Discernment Cycles). This indicates that over time, there are iterations. After some years of working in alignment, a person might encounter a new life stage or external change prompting re-discernment – for example, considering a shift in mission focus or re-training (perhaps moving from direct practice to teaching the next generation, as often happens in mid-career professionals). Seasonality ensures the model is not linear but cyclical and adaptive. An aligned individual can become misaligned if they grow but their role doesn’t, or if their mission clarifies further. Thus, planned reflection points (e.g. a mid-career sabbatical or a graduate program enrollment) feed back into renewed Calling Discernment and Mission Clarity, updating the cycle. In a figure, seasonality could be drawn as a circular arrow looping from outcomes or later stages back to the beginning of the process, encompassing the whole model in a spiral.

Implicit in the model but also noteworthy is the role of Agency and Stewardship (which might not be separate boxes but embedded in how the process functions). Agency is what propels the individual through the model – the personal drive to engage in discernment, practice gifts, seek alignment. Stewardship influences the direction of outcomes – ensuring that as alignment and impact increase, they are oriented ethically and benefit others. If one were to include them explicitly, agency might be an energizing force indicated by a lightning bolt icon pushing the person through each stage, and stewardship might be a guiding compass icon keeping the outcomes in check with values.

To illustrate concretely: imagine a schematic “

Figure 1: Mission-Driven Learning Theory Model.” On the left, a box “Discernment Practices & Experiences” with an arrow to “Mission Clarity.” Two boxes “Giftedness” and “Formation” with arrows to “Competence.” Mission Clarity and Competence arrows converge on “Alignment” at center. A dotted arrow from “Community Confirmation” (above) intersects the arrow from Mission Clarity to Alignment (signifying moderation). From “Alignment” in the center, arrows go out to three outcome boxes on the right: “Contribution/Impact,” “Persistence (Retention),” “Well-being (Satisfaction/Thriving).” Finally, a circular arrow labeled “Seasonality – Re-discernment” loops from the outcomes back around to the Discernment box, indicating the cycle continues. This captures the verbal narrative above: discernment yields clarity, gifts+formation yield competence, clarity+competence yield alignment (checked by community), alignment yields good fruit, and the journey continues with adaptation.

Table 3.

Differential Predictions and Falsification Windows.

Table 3.

Differential Predictions and Falsification Windows.

| Focal Variable |

Self-Determination Theory |

Person–Environment Fit |

MDLT |

Risk of Disconfirmation for MDLT |

| Motivation when autonomy & competence are high but life mission is low |

High intrinsic motivation |

Moderate engagement |

Moderate-to-low engagement |

If motivation remains high despite low mission clarity |

| Burnout under value conflict |

Moderate |

High |

High unless seasonality checkpoint triggers realignment |

If burnout rates do not fall after structured re-discernment |

| Long-term contribution (10 yrs) |

Unspecified |

Job performance |

Societal impact aligned with stated telos |

If alumni impact is unrelated to articulated mission |

H1 Early-semester discernment practices (Weeks 1-8) will increase Mission Clarity by β ≥ .30 at Semester 2. H2 Mission Clarity × Domain Competence at Semester 6 will predict Alignment (β ≥ .20). H3 Alignment at Semester 8 will predict Graduation Persistence (OR ≥ 1.50) and Early-Career Role Stability at +12 months (hazard ratio ≤ 0.70). Through this model, MDLT provides a causal structure that can be empirically tested and practically implemented. The next section will translate this into formal propositions that articulate our key theoretical claims in a form ready for research scrutiny.

6. Propositions

Translating MDLT into testable propositions helps clarify its claims and invite empirical examination. We propose six key propositions:

P1. Mission clarity predicts persistence in learning and reduces program or early-career drift, beyond the effects of prior achievement.

Justification: Students who have a clear sense of purpose or calling are hypothesized to be more resilient and persistent in their educational path. Even controlling for prior academic achievement (grades, test scores), mission clarity should add explanatory power for outcomes like continuous enrollment, program completion, or sticking with one’s chosen field in the early career years. Prior research supports this logic: for example, adolescents with identified “purposeful work goals” find schoolwork more meaningful and report greater motivation (GGIE, 2025; Yeager & Bundick, 2009). Yeager and Bundick (2009) found that youth with a sense of purpose connected their academic efforts to that purpose and, as a result, engaged more deeply Yeager & Bundick, 2009). In higher education, having a career purpose has been linked to lower dropout rates and better adjustment (e.g., students who feel their studies have a meaningful direction are less likely to drift or change majors arbitrarily) (Moran, 2018). Mission clarity provides a stabilizing “North Star” that keeps learners from quitting when challenges arise or from being swayed by every alternative opportunity. Conversely, lack of clarity often manifests as frequent switching of majors, “shopping around” in jobs post-graduation, or disengagement – patterns seen in graduates who wander through several false starts. We expect empirical research to show that, all else equal, a one-unit increase in measured mission clarity (e.g., via a Purpose Scale) is associated with a significant decrease in the likelihood of dropping out or changing majors, even controlling for GPA, socioeconomic status, etc. A longitudinal study could test P1 by measuring incoming students’ purpose clarity and tracking their academic persistence. We predict a positive association, confirming that mission clarity contributes uniquely to persistence beyond academic ability. This addresses a major practical problem in education – many students leave or change direction not for lack of ability, but for lack of why. MDLT posits that strengthening the why (telos) combats this drift.

P2. Alignment between one’s gifts, formation (character), and chosen learning pathway predicts greater gains in competence and higher well-being than misalignment.

Justification: Alignment here refers to a congruence measure: how well a student’s program of study or training corresponds to their known strengths and values. P2 suggests that students in high alignment will both learn more effectively (competence gains) and experience better well-being (satisfaction, stress management, etc.) compared to those in a state of misalignment. This is rooted in person-environment fit theory (GGIE, 2025) and self-determination theory. When students use their signature strengths in pursuing goals they value, they tend to enter a state of intrinsic motivation and “flow” which enhances learning outcomes and psychological health. For example, research on strengths-based education shows that when students can leverage their strengths in academic work, they achieve more and feel more fulfilled (GGIE, 2025). Complementing calling research, the definitive meta-analysis on person–environment fit found a corrected mean correlation of .43 with job satisfaction and .31 with performance (Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, & Johnson, 2005). In higher education, a 60-study meta-analysis of interest–major congruence showed that students whose Holland types match their field earn GPAs .17 SD higher and are 25 % more likely to persist (Nye et al., 2017). These findings strengthen P2’s claim that alignment between mission, gifts, and learning environment yields both competence gains and psycho-social flourishing. In an academic context, a student aligned with their gifts (say a socially gifted, empathetic student in a human services major, as opposed to being in, say, an isolated lab environment) is likely to excel and feel happier. Well-being indicators such as lower anxiety, higher life satisfaction, and academic self-concept are expected to be higher in aligned students (GGIE, 2025). Competence gains can be measured by grades, skill assessments, or performance tasks; alignment should facilitate deeper engagement and persistence at tasks, leading to mastery. Misalignment, by contrast, often leads to disengagement or poorer performance – e.g., a highly creative student forced into a rote learning environment might underperform and feel frustrated. P2 can be tested by assessing alignment (via surveys on whether students feel their studies reflect their strengths and values) and correlating with academic outcomes and surveys of well-being. We anticipate a significant positive correlation: those who report high alignment show higher GPA or competency test improvements and higher well-being scores, controlling for baseline ability or well-being. This proposition reinforces that fitting the person to the learning pathway (not just the pathway to generic standards) yields benefits.

P3. Participation in structured discernment practices increases mission clarity, which in turn mediates gains in motivation and transfer of learning.

Justification: This proposition implies a causal sequence: implementing interventions like workshops on purpose, reflective journaling, mentorship, or service-learning (all examples of discernment practices) will boost students’ clarity about their mission/purpose. That improved mission clarity then leads to higher academic motivation and better transfer of learning to real-life contexts. The idea is that when students regularly reflect on and refine their “why,” they connect their coursework to that reason, which energizes their effort and helps them apply what they learn beyond the classroom. There is evidence for each link. On the first link: purpose development programs have shown efficacy (Beloborodova & Leontiev, 2024). For instance, one study tested a purpose-focused curriculum for college students and found it indeed increased students’ sense of calling and vocational identity compared to controls (Beloborodova & Leontiev, 2024). Another example, as found in an educational intervention, having high school students write about how learning could help them contribute to their community significantly increased their academic effort (a self-transcendent purpose intervention) (Yeager & Bundick, 2009). A recent multi-site RCT with 3,674 secondary students confirmed these effects: a brief self-transcendent purpose writing task improved science course grades by 0.18 GPAs and reduced semester failure odds by 22 % (Yeager et al., 2014). A meta-analysis of purpose interventions across 26 studies likewise reported medium effects on self-regulation (g = 0.45) and near-transfer learning (g = 0.34; Yeager et al., 2014), providing strong causal backing for P3. On the second link: once students have more mission clarity, we know from earlier arguments that their motivation (especially intrinsic motivation) rises (GGIE, 2025). They see meaning in tasks and are more likely to persist and do deep learning. Transfer of learning – the application of knowledge to new situations – is often a challenge in education. But if a student has a clear context or mission to apply knowledge to, they are more likely to connect theoretical concepts to practice. For example, a business student with a clear mission to alleviate poverty may more readily transfer concepts from economics class to designing a social enterprise model, because they are constantly filtering knowledge through the lens of that mission. Empirical work can test P3 by randomly assigning some students to undergo structured calling discernment activities (e.g. a semester course on vocation, with reflective exercises and service projects) and others to a control condition, then measuring changes in mission clarity and subsequent motivation (e.g. using the Self-Regulation Questionnaire or measures of engagement) and transfer (perhaps via scenario-based assessments requiring applying knowledge). We expect to see that the intervention group shows significant increases in purpose clarity, which statistically mediates (explains) higher motivation and better performance on transfer tasks. P3 underscores MDLT’s claim that intentional pedagogical practices aimed at calling discernment have downstream academic benefits – they are not fluffy add-ons, but leverage points for better learning.

P4. Community confirmation moderates the effect of self-perceived calling on outcomes: specifically, when a student’s sense of calling is affirmed by mentors or peers, it leads to stronger positive outcomes (e.g. confidence, goal progress), but when unconfirmed it may lead to overconfidence or “vocational illusion” that hampers development.

Justification: This proposition addresses the social dimension of calling. A student’s self-perceived mission (“I believe I am called to do X”) can have powerful motivational effects – but without reality checks, it might become unrealistic or disconnected from actual aptitude (vocational illusion), or even narcissistic. We posit that confirmation from the community (like mentors saying “Yes, you have a real gift and passion for this, I see it in you” or a community benefiting and validating the student’s contribution) will amplify the positive effect of having a calling, while lack of confirmation or negative feedback (“this might not be your strength”) will dampen it or protect against potential negative outcomes. Support for this comes from vocational research noting that having an “unanswered calling” or unsupported calling can lead to distress (Abouras, 2021; Duffy & Dik, 2013). Other studies have found that people reporting a calling without living it out (which could be due to lack of opportunity or perhaps lack of fit) have lower well-being than those living their calling (Dobrow et al., 2023). Community confirmation can be seen as a proxy for alignment and opportunity – if your mentors and relevant community encourage you, you’re more likely to get opportunities to act on your calling and do so effectively. Conversely, if everyone around you is skeptical of your perceived calling, maybe you either misdiscerned or you’ll face barriers, and charging ahead regardless might lead to failure or disappointment (overconfidence effect). We can test P4 by measuring calling (self-perceived) and gathering data on confirmation (like a mentor-rated scale of “I think this student’s goals are a good fit for them” or if applicable, a 360-feedback from peers). Outcomes to examine might include progress towards goals (like how many steps taken in career preparation), skill improvement, or psychological outcomes (confidence vs. frustration). The moderation means we’d likely find that self-perceived calling is strongly correlated with, say, academic project success only when confirmation is high. If confirmation is low, those with high self-belief in a calling might actually not perform any better (or could even perform worse if overconfidence leads to ignoring constructive feedback). This proposition is important to address a critique: MDLT doesn’t encourage students to follow pipe dreams blindly; it insists on a dialogue with community truth-telling. P4 encourages educators to integrate feedback loops, such as panels or mentoring, precisely to calibrate student callings with reality.

P5. Programs organized around MDLT (with integrated calling curriculum, mentoring, and personalized pathways) yield stronger long-term contribution outcomes than knowledge-only or competency-only designs, when controlling for incoming student characteristics.

Justification: P5 is a macro-level claim: if you implement MDLT in an educational program, the graduates of that program will on average contribute more in their careers and communities long-term than graduates from a traditional program, assuming similar starting populations. Contribution outcomes could be operationalized as things like leadership roles attained, innovations created, community service engagement, or recognized accomplishments in one’s field after, say, 5-10 years. This is admittedly an ambitious proposition and challenging to test, but not implausible. Supporting reasoning: A curriculum that explicitly cultivates mission and alignment should produce graduates who are purpose-driven, aligned, and resilient, which in turn fosters greater impact (a motivated individual will seek opportunities to make a difference, not just punch a clock). Gallup’s large-scale studies lend credence: college alumni who had mentoring and “experiential and deep learning” opportunities (akin to MDLT elements) are more likely to be engaged in their work and thriving in well-being later (Howell, 2018; Gallup & WFF, 2024 ). Engagement at work often correlates with higher performance and impact. Additionally, consider anecdotal evidence: institutions like certain purpose-driven colleges or faith-based universities often tout that their alumni disproportionately go into service-oriented careers or leadership – indicating an effect of mission-centric education. MDLT would predict that if two schools have similar student bodies at entrance, the one embedding mission discernment, mentorship, etc., will see more of its grads actually stick with and excel in fields that matter to them. A quasi-experimental evaluation could compare, for instance, an MDLT-based honors program vs. a regular program, or an institution that implements a “purpose curriculum” vs. one that does not, tracking outcomes in alumni surveys. We would control for SAT scores, GPA, etc., to ensure differences are due to the program, not selection. The expectation (P5) is that the MDLT group would report higher rates of meaningful accomplishments: e.g., they started more nonprofits, achieved notable advancements in their companies, or remained in service professions with greater satisfaction, compared to the non-MDLT group. This proposition essentially claims that MDLT doesn’t just feel good – it produces tangibly different kinds of graduates, those who are change agents or high contributors. It’s a bold claim requiring longitudinal research.

P6. Seasonality checkpoints that invite re-discernment reduce burnout and premature career foreclosure, improving sustained alignment over time.

Justification: This proposition addresses the longevity of one’s vocational journey. Premature foreclosure is a term from identity development (Marcia, 1966) referring to committing to an identity without sufficient exploration. In careers, it could mean locking into a particular job identity too early (perhaps due to parental or financial pressure) and later regretting it, or conversely, stubbornly sticking to an early-career mission without adapting even as one’s circumstances change, potentially leading to burnout. P6 posits that if educational programs (and later workplaces or professional bodies) intentionally introduce periodic “seasonality checkpoints” – structured times to reflect, possibly pivot or adjust one’s path – individuals will experience less burnout (emotional exhaustion, loss of enthusiasm) and avoid getting stuck in ill-fitting roles. Instead, they will maintain or regain alignment. Evidence for this can be extrapolated from research on career adaptability and mid-career development. Savickas’ career construction theory suggests that revisiting one’s narrative and adapting is key to career satisfaction. Also, studies show that people who engage in lifelong learning or make planned career changes often report renewed engagement rather than burnout. Burnout tends to happen when one feels trapped in a mismatch between self and work or when work lacks meaning – seasonality encourages re-aligning work with evolving self and mission, thereby re-infusing meaning (de Bloom et al., 2012). Another thread of evidence: In employee wellness literature, sabbaticals or structured reflection interventions are linked to improved well-being and retention post-sabbatical (people come back rejuvenated, often with new purpose) (Davidson et al., 2010). To test P6, one might implement an intervention where young professionals attend a guided retreat or reflection seminar at certain intervals (say, two years into a job, or during grad school transitions) vs. a control group that doesn’t. Outcomes measured could be burnout scales, and whether they make any positive career adjustments (e.g., shifting roles in their organization to better use strengths). We expect those with checkpoints show lower burnout and are more likely to realign their responsibilities to fit their core mission. In an academic context, students given a chance each year to reconsider and tweak their educational plan (without penalty or stigma) might end up more satisfied and on-track by graduation, whereas those who feel locked in from year one might burn out or drop out. Essentially, P6 underscores flexibility within faithfulness – MDLT is not rigid one-and-done; it encourages a healthy cycle of renewal that ultimately extends one’s capacity to contribute without flaming out. If supported, this proposition would advocate that educational and organizational policies incorporate periodic reflection and re-planning phases as a norm.