Submitted:

09 September 2025

Posted:

10 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Elastic and Hyperelastic Constitutive Equations

2.1. Consitutive Equations

2.2. Determination of Hyperelastic Material Parameters

3. Materials and Methods

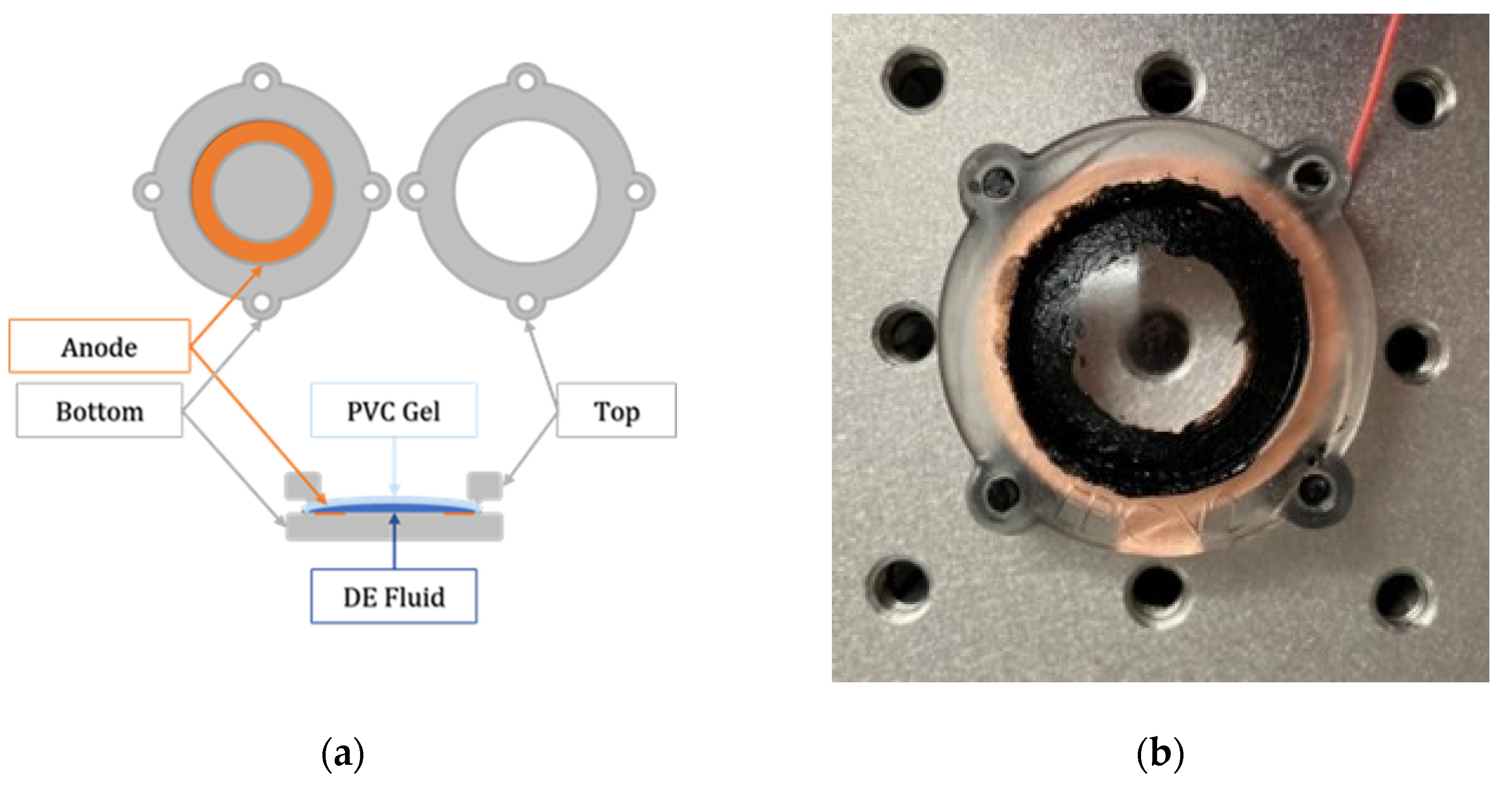

3.1. EPIC Actuator

3.2. Material Preparation of PVC Gel Samples

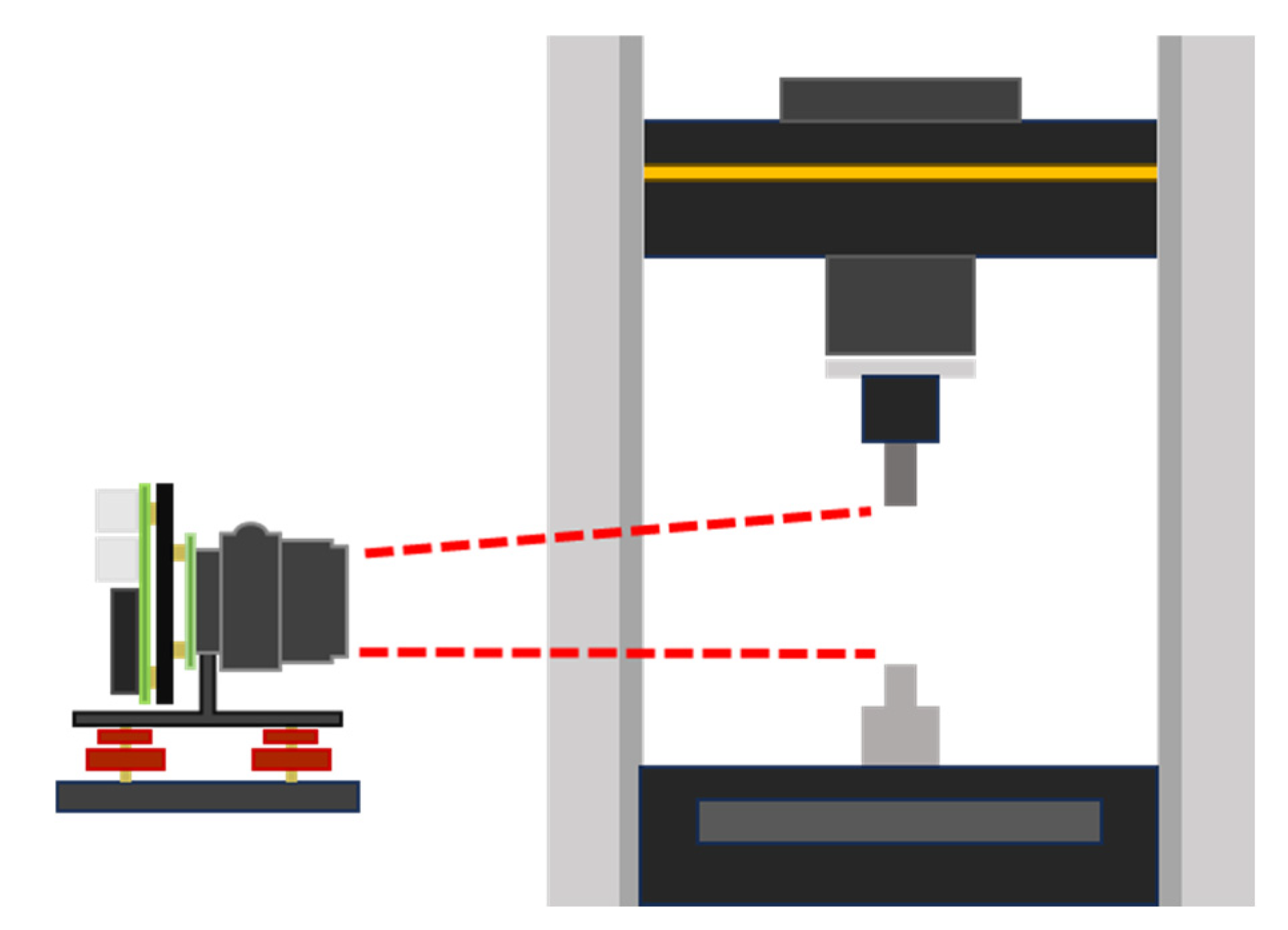

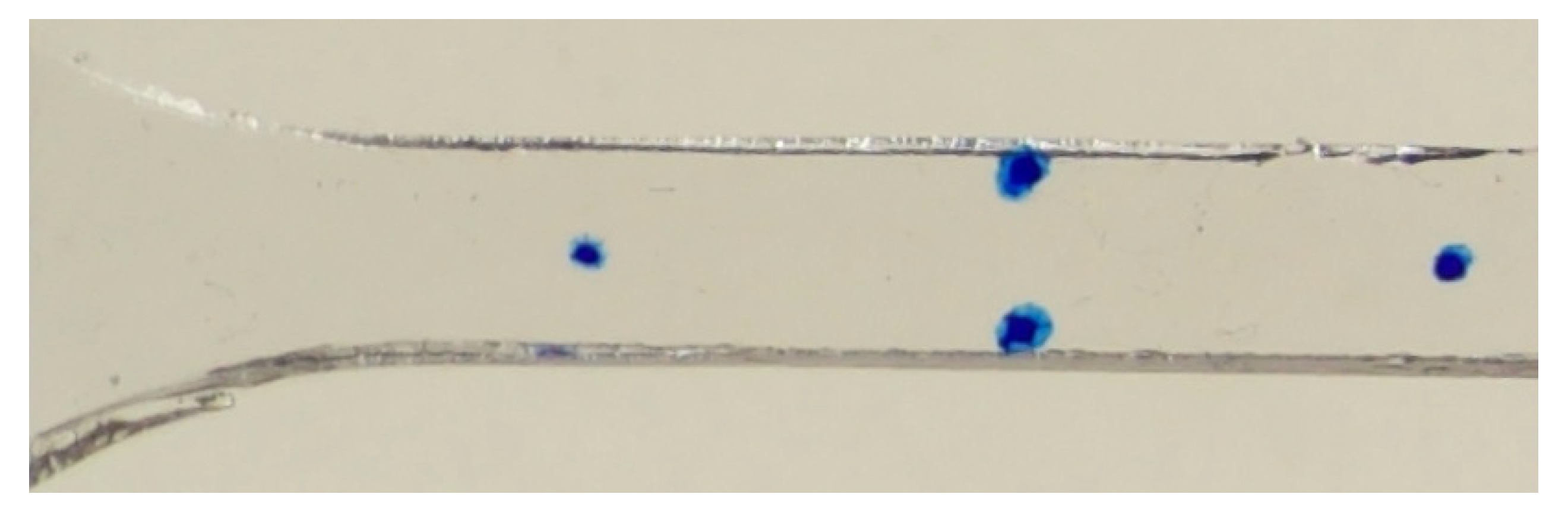

3.3. Tensile Testing

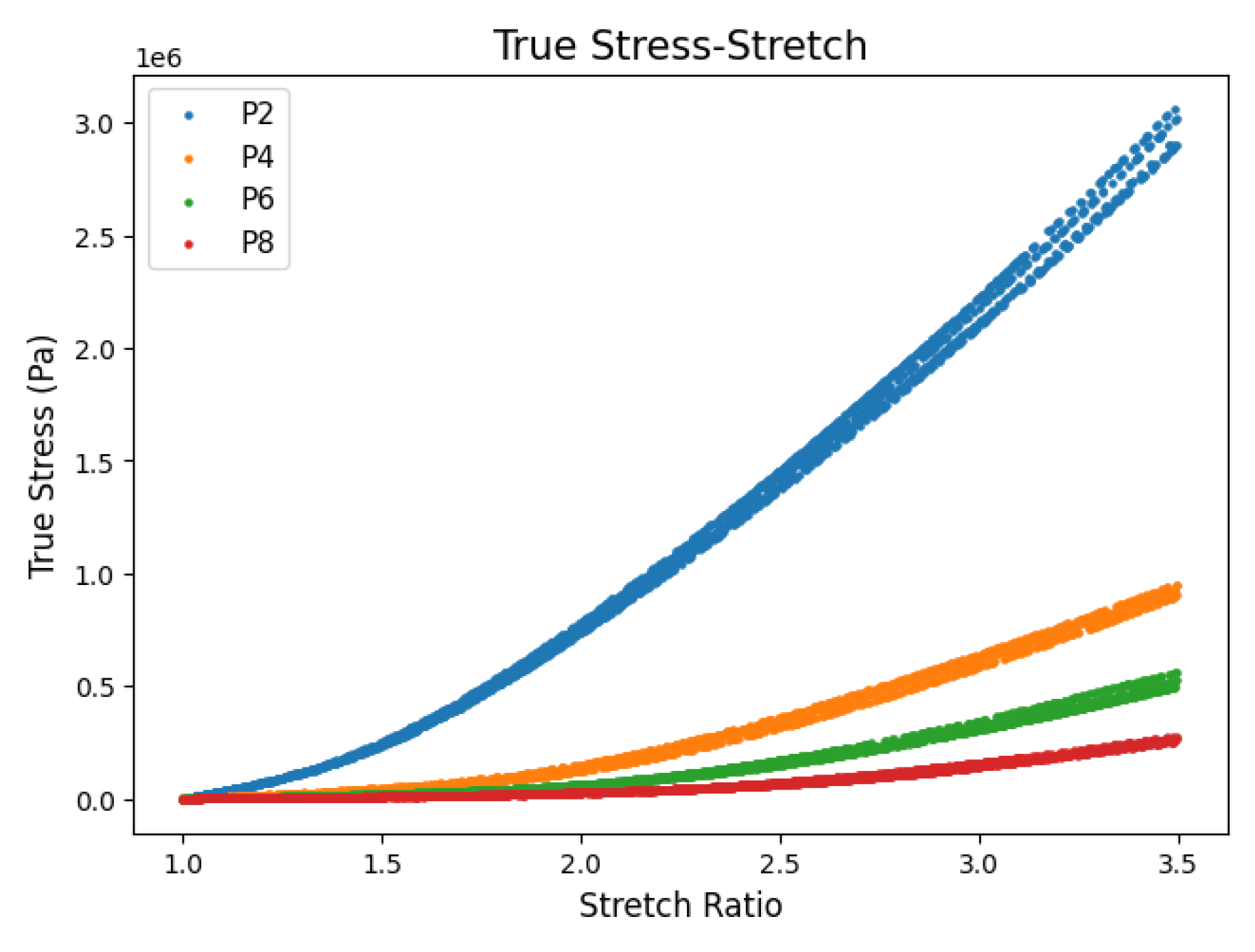

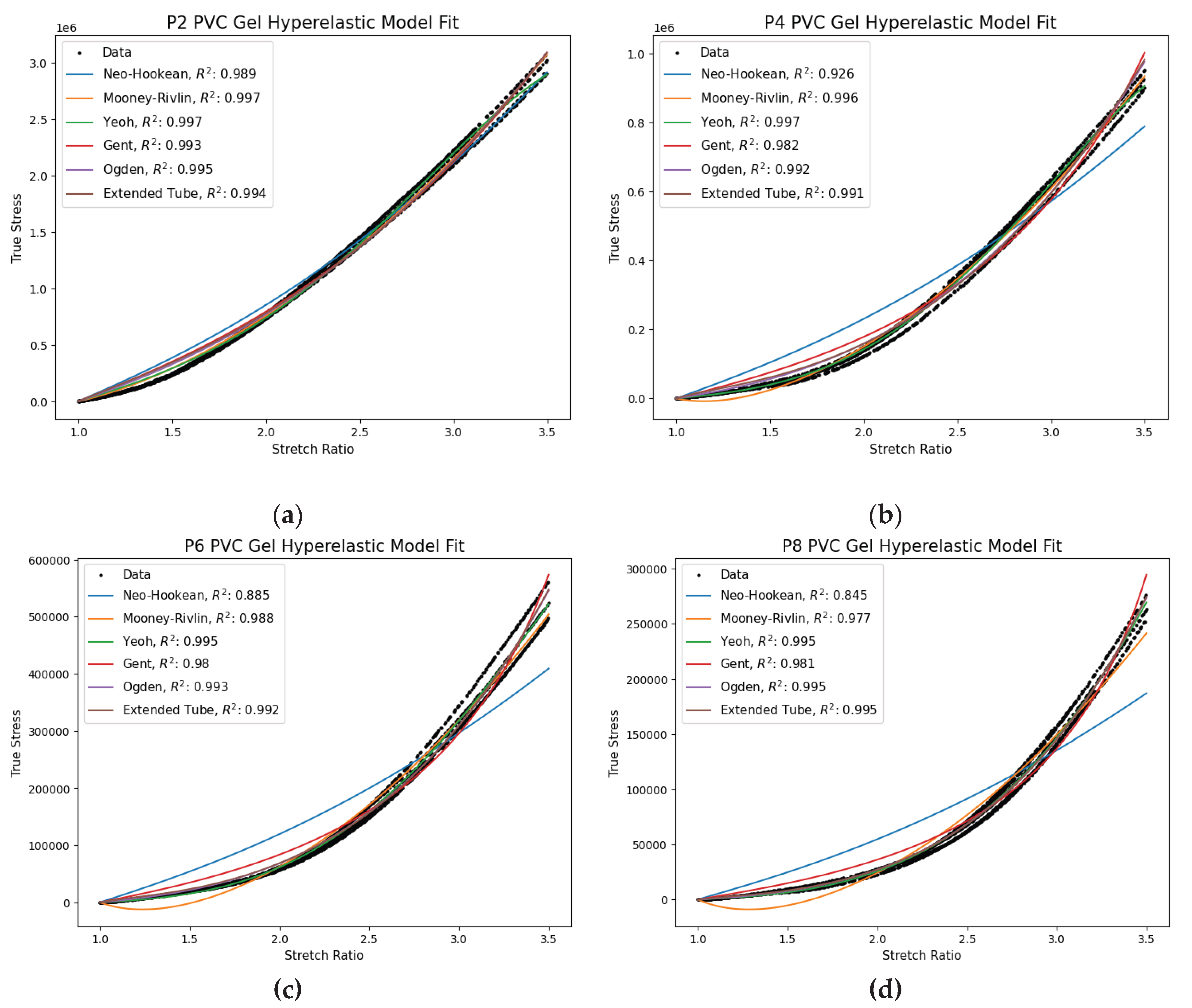

4. Results and Discussion

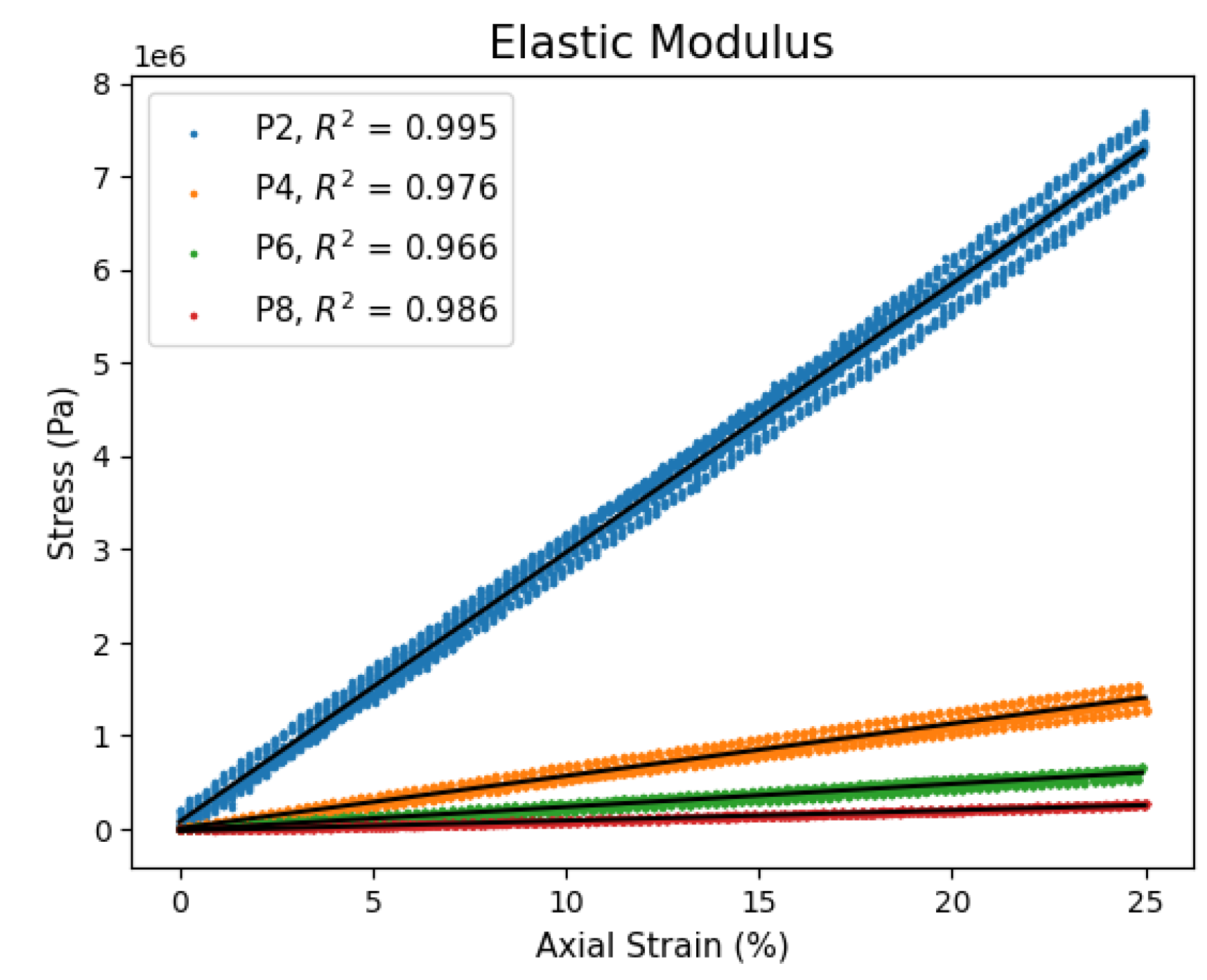

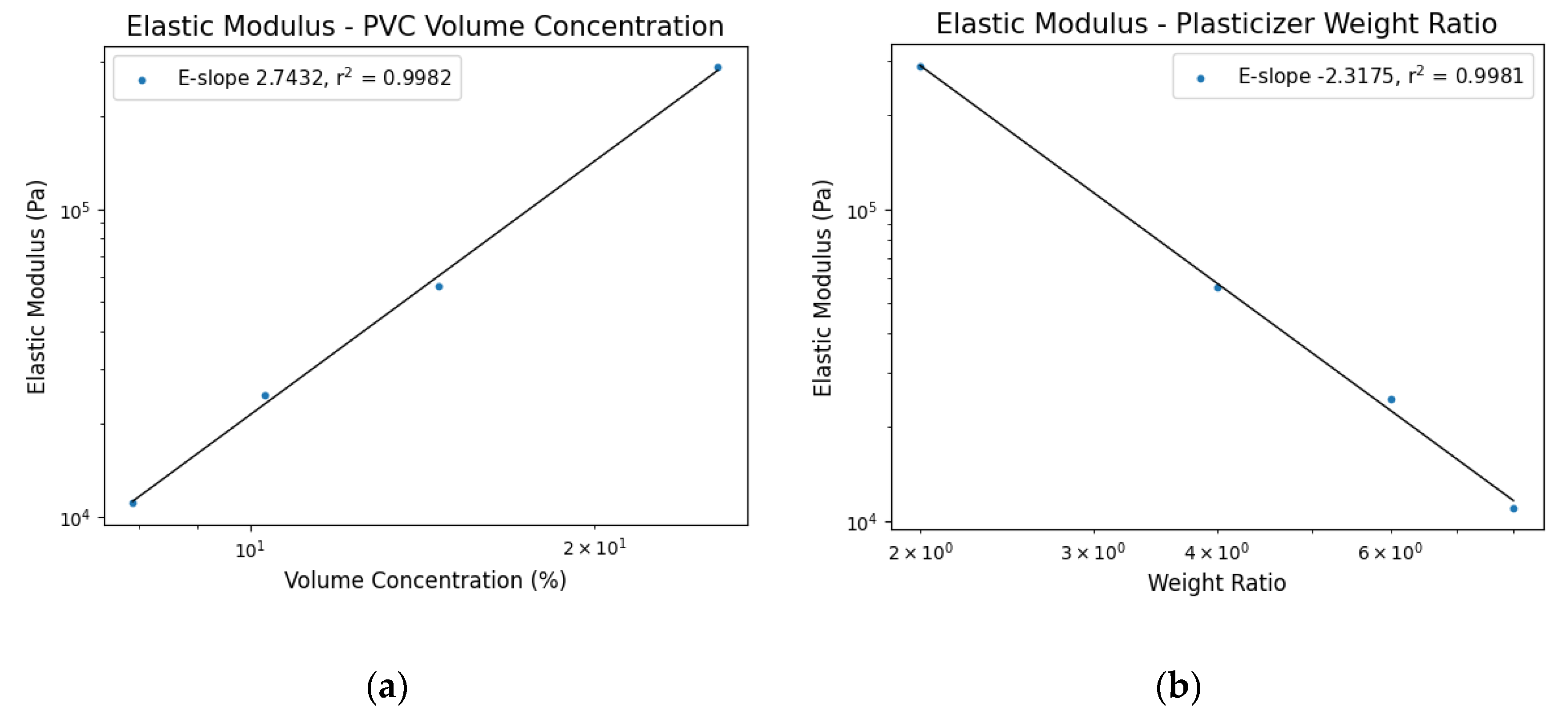

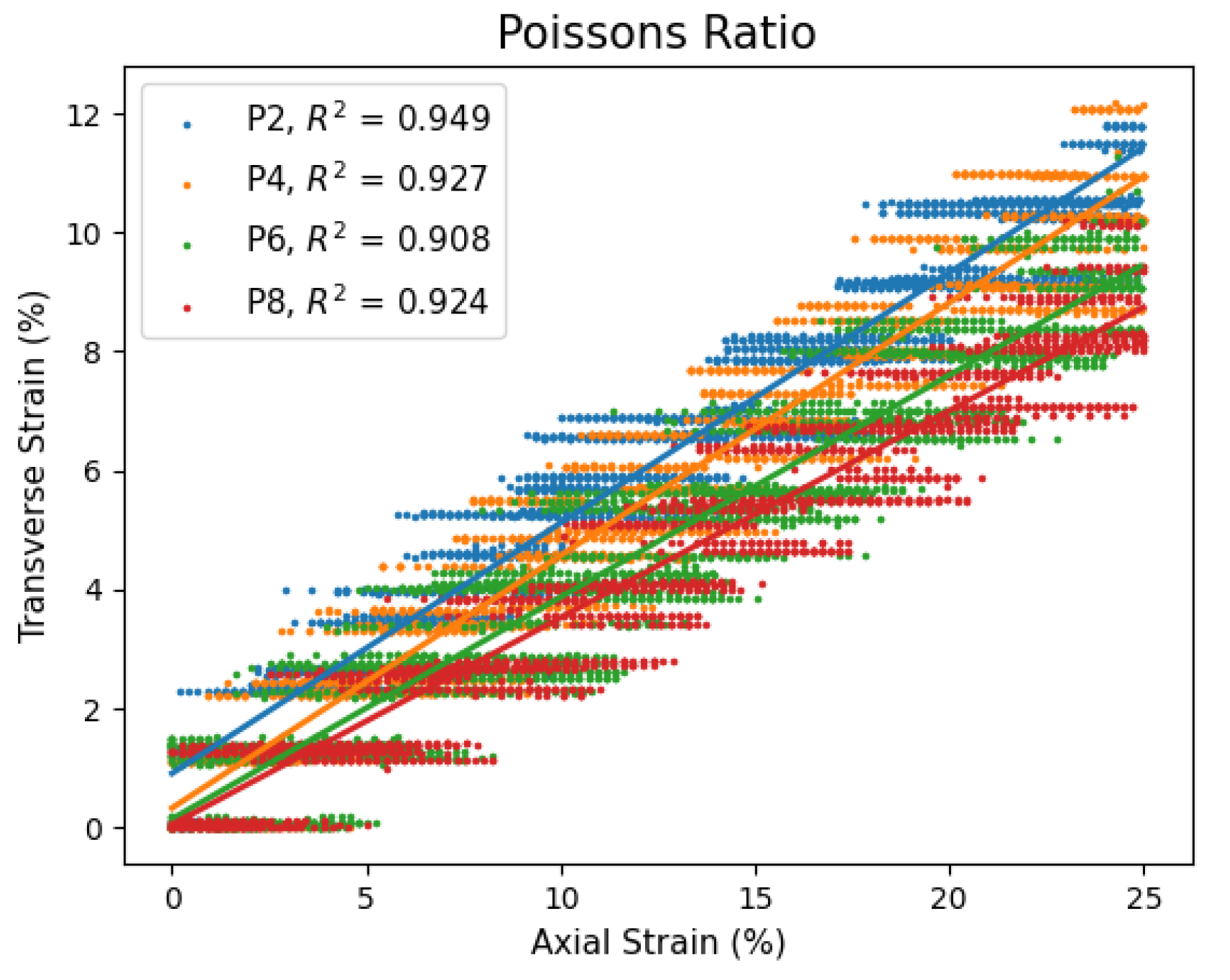

4.1. Elastic Modeling

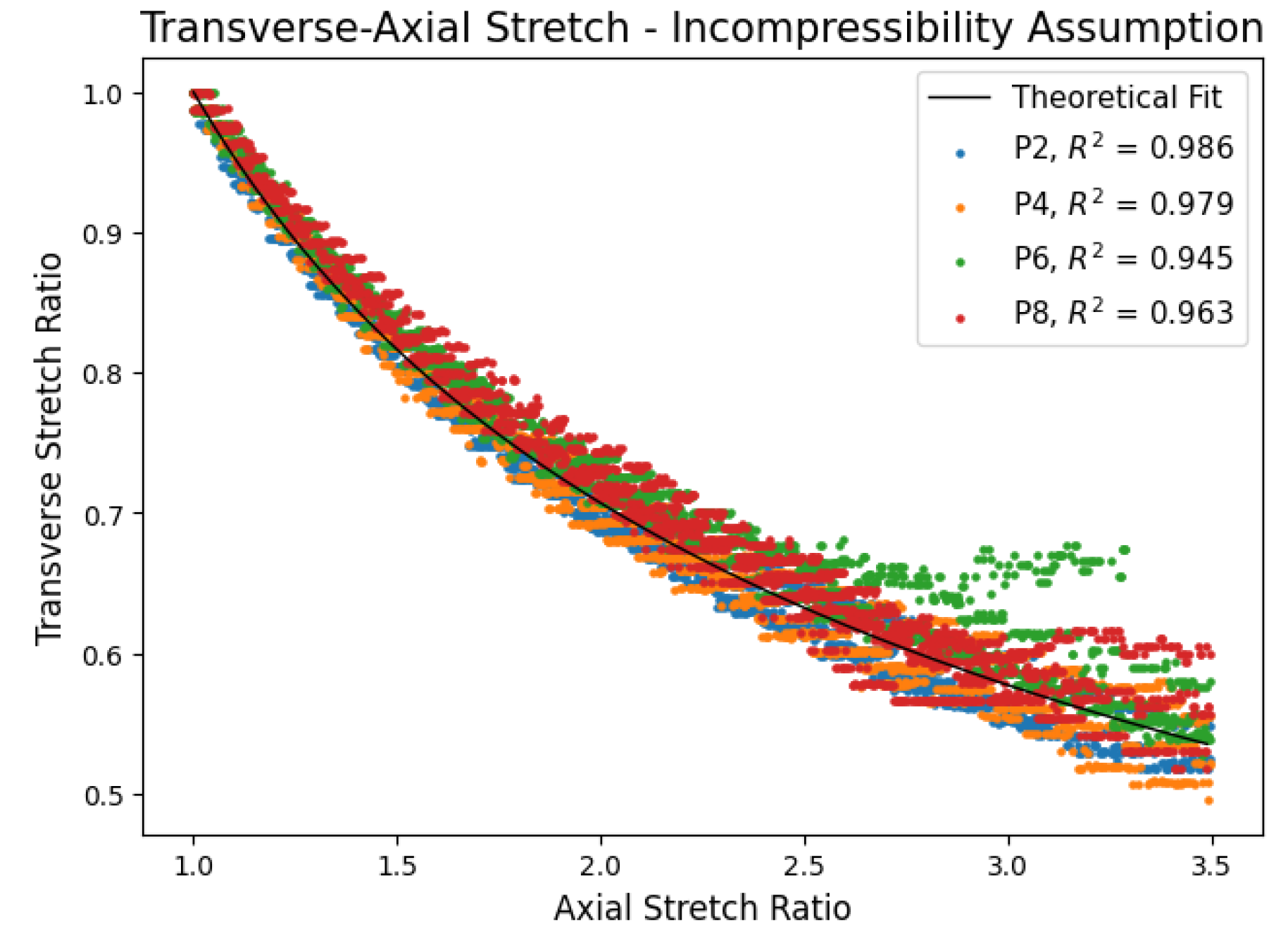

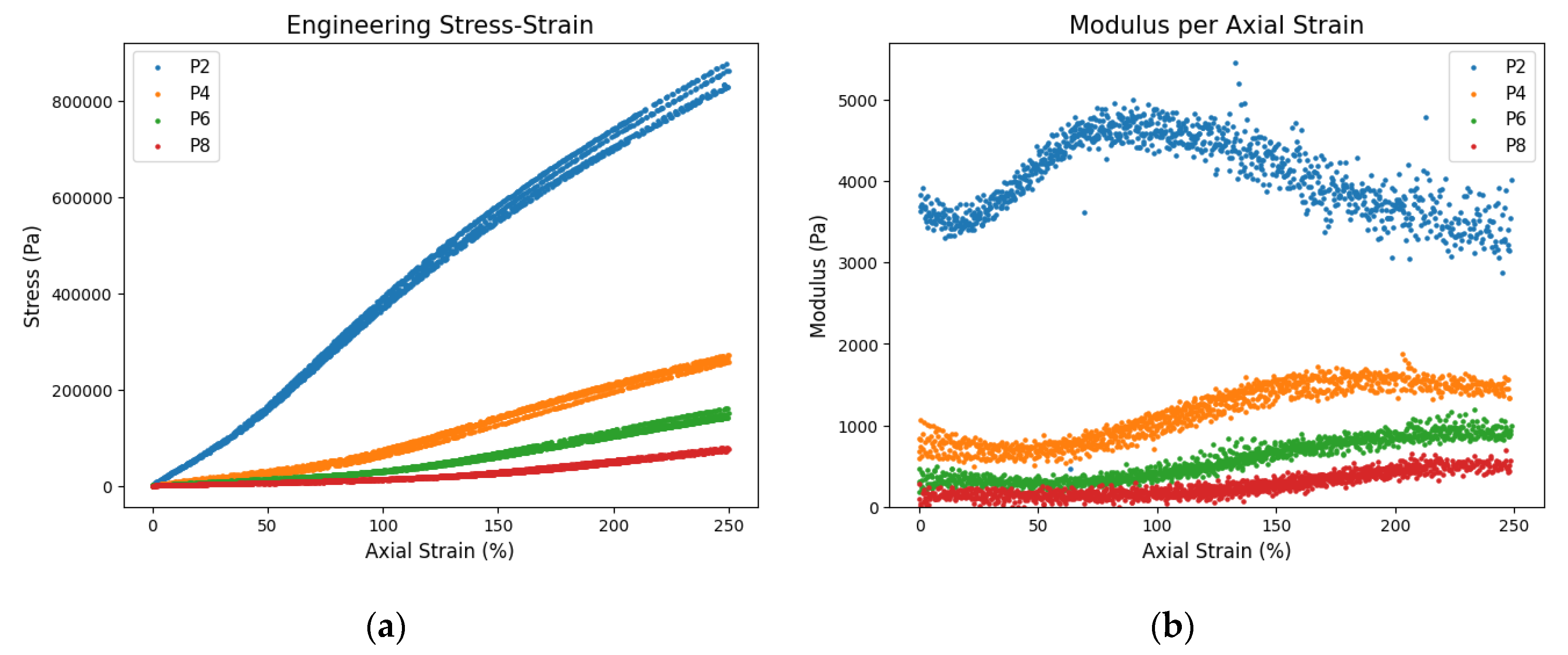

4.2. Hyperelastic Modeling

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PVC | Polyvinyl chloride |

| PX | Plasticizer to PVC weight ratio (X:1) |

| DBA | Dibutyl adipate plasticizer |

| THF | Tetrahydrofuran |

| DEA | Dielectric elastomer actuator |

| EPIC | Electrohydraulic actuator powered by induced interfacial charges |

| HASEL | Hydraulically amplified self-healing electrostatic |

| DE | Dielectric |

| KAIST | Korea Advanced Institute of Science & Technology |

| BOPP | Biaxially oriented polypropylene |

| LM | Levenberg–Marquardt |

References

- M. Z. Uddin, M. Yamaguchi, M. Watanabe, H. Shirai, and T. Hirai, “Electrically induced creeping and bending deformation of plasticized poly(vinyl chloride),” Chem Lett, no. 4, 2001. [CrossRef]

- M. Z. Uddin, M. Watanabe, H. Shirai, and T. Hirai, “Effects of plasticizers on novel electromechanical actuations with different poly(vinyl chloride) gels,” J Polym Sci B Polym Phys, vol. 41, no. 18, 2003. [CrossRef]

- H. Xia, T. Ueki, and T. Hirai, “Electrical response and mechanical behavior of plasticized PVC actuators,” in Advanced Materials Research, 2009. [CrossRef]

- H. Xia and T. Hirai, “Space charge distribution and mechanical properties in plasticized PVC actuators,” in 2009 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation, ICMA 2009, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li and M. Hashimoto, “PVC gel based artificial muscles: Characterizations and actuation modular constructions,” Sens Actuators A Phys, vol. 233, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li and M. Hashimoto, “PVC gel soft actuator-based wearable assist wear for hip joint support during walking,” Smart Mater Struct, vol. 26, no. 12, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li and M. Hashimoto, “Design and prototyping of a novel lightweight walking assist wear using PVC gel soft actuators,” Sens Actuators A Phys, vol. 239, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, Y. Maeda, and M. Hashimoto, “Lightweight, Soft Variable Stiffness Gel Spats for Walking Assistance,” Int J Adv Robot Syst, vol. 12, no. 12, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Shibagaki, T. M. Shibagaki, T. Matsuki, M. Hashimoto, and T. Hirai, “Application of a contraction type PVC gel actuator to brakes,” in 2010 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation, ICMA 2010, 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Hashimoto, M. Shibagaki, and T. Hirai, “Development of a Negative Type Polymer Brake Using a Contraction Type PVC Gel Actuator,” Journal of the Robotics Society of Japan, vol. 29, no. 8, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, B. Sun, T. Chen, B. Hu, M. Guo, and Y. Li, “Design and prototyping of a novel gripper using PVC gel soft actuators,” Jpn J Appl Phys, vol. 60, no. 8, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Frank, Z. Z. Frank, Z. Olsen, T. Hwang, and K. J. Kim, “A multi-degree of freedom bending actuator based on a novel cylindrical polyvinyl chloride gel,” 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Ali and T. Hirai, “Characteristics of the creep-induced bending deformation of a PVC gel actuator by an electric field,” J Mater Sci, vol. 46, no. 24, 2011. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim, J. Ma, M. Kim, J. Nam, and K.-U. Kyung, “High-Output Force Electrohydraulic Actuator Powered by Induced Interfacial Charges,” Advanced Intelligent Systems, vol. 3, no. 5, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Kirkman, P. Rothemund, E. Acome, and C. Keplinger, “Electromechanics of planar HASEL actuators,” Extreme Mech Lett, vol. 48, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.eml.2021.101408. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, S. K. Mitchell, E. H. Rumley, P. Rothemund, and C. Keplinger, “High-Strain Peano-HASEL Actuators,” Adv Funct Mater, vol. 30, no. 7, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Kellaris, V. G. Venkata, G. M. Smith, S. K. Mitchell, and C. Keplinger, “Peano-HASEL actuators: Muscle-mimetic, electrohydraulic transducers that linearly contract on activation,” Sci Robot, vol. 3, no. 14, 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Acome et al., “Hydraulically amplified self-healing electrostatic actuators with muscle-like performance,” Science (1979), vol. 359, no. 6371, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Kang, S. Kim, and Y. Cha, “Multimodal motion of soft origami tripod using electrohydraulic actuator,” p. 1294809, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- Washington, J. Su, and K. J. Kim, “Actuation Behavior of Hydraulically Amplified Self-Healing Electrostatic (HASEL) Actuator via Dimensional Analysis,” Actuators, vol. 12, no. 5, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Faccinto, D. J. Faccinto, D. Fisher, A. Sennain, J. Neubauer, and K. J. Kim, “Electromechanical applications of PVC gels and EPIC actuators in varifocal lenses,” 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Rothemund, N. Kellaris, and C. Keplinger, “How inhomogeneous zipping increases the force output of Peano-HASEL actuators,” Extreme Mech Lett, vol. 31, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Walter, “Elastic properties of polvinyl chloride gels,” Journal of Polymer Science, vol. 13, no. 69, 1954. [CrossRef]

- M. Yamano, N. M. Yamano, N. Ogawa, M. Hashimoto, M. Takasaki, and T. Hirai, “A contraction type soft actuator using poly vinyl chloride gel,” in 2008 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics, ROBIO 2008, 2009. [CrossRef]

- H. Xia and T. Hirai, “Electric-field-induced local layer structure in plasticized PVC actuator,” Journal of Physical Chemistry B, vol. 114, no. 33, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Z. Frank and K. J. Kim, “On the mechanism of performance improvement of electroactive polyvinyl chloride (PVC) gel actuators via conductive fillers,” Sci Rep, vol. 12, no. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Hwang, Z. Frank, J. Neubauer, and K. J. Kim, “High-performance polyvinyl chloride gel artificial muscle actuator with graphene oxide and plasticizer,” Sci Rep, vol. 9, no. 1, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, Y. Y. Li, Y. Tsuchiya, A. Suzuki, Y. Shirai, and M. Hashimoto, “Influence of the number of stacked layers on the performance of PVC gel actuators,” in IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics, AIM, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. TSUCHIYA and M. HASHIMOTO, “Development of contraction type sheets using PVC gel,” The Proceedings of JSME annual Conference on Robotics and Mechatronics (Robomec), vol. 2015, no. 0, 2015. [CrossRef]

- N. Gent and N. Shimizu, “Elasticity, tear strength, and strength of adhesion of soft PVC gels,” J Appl Polym Sci, vol. 32, no. 6, 1986. [CrossRef]

- F. Gallego, M. E. Muñoz, J. J. Peña, and A. Santamaría, “Dynamic viscoelastic measurements of pvc gels,” Eur Polym J, vol. 24, no. 4, 1988. [CrossRef]

- D. López, C. Mijangos, M. E. Muñoz, and A. Santamaría, “Viscoelastic properties of thermoreversible gels from chemically modified PVCs,” Macromolecules, vol. 29, no. 22, 1996. [CrossRef]

- G. Youssef, “Hyperelastic behavior of polymers,” Applied Mechanics of Polymers, pp. 117–144, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Bergström, “Elasticity/Hyperelasticity,” Mechanics of Solid Polymers, pp. 209–307, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Bhat and A. Keerthan, “Power-Yeoh: A Yeoh-Type Hyperelastic Model with Invariant I2 for Rubber-like Materials,” Engineering Proceedings, vol. 59, no. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Puglisi and G. Saccomandi, “The Gent model for rubber-like materials: An appraisal for an ingenious and simple idea,” Int J Non Linear Mech, vol. 68, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Kaliske and G. Heinrich, “An extended tube-model for rubber elasticity: Statistical-mechanical theory and finite element implementation,” Rubber Chemistry and Technology, vol. 72, no. 4, 1999. [CrossRef]

- M. Ali, T. Ueki, D. Tsurumi, and T. Hirai, “Influence of plasticizer content on the transition of electromechanical behavior of PVC gel actuator,” Langmuir, vol. 27, no. 12, pp. 7902–7908, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. C. Yang and P. H. Geil, “Morphology and Properties of PVC/Solvent Gels,” Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B, vol. 22, no. 3, 1983. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bao, Z. Weng, Z. Huang, and Z. Pan, “The crystallinity of PVC and its effect on physical properties,” International Polymer Processing, vol. 11, no. 4, 1996. [CrossRef]

- M. Seki, S. Yamamoto, Y. Aoki, K. Takagi, Y. Izumi, and S. Nojima, “Small-angle x-ray scattering study of thermoreversible poly(vinyl chloride) gels,” J Polym Sci B Polym Phys, vol. 39, no. 20, 2001. [CrossRef]

- H. -K Boo and M. T. Shaw, “Gelation and interaction in plasticizer/PVC solutions,” Journal of Vinyl Technology, vol. 11, no. 4, 1989. [CrossRef]

- Y. Aoki, L. Li, H. Uchida, M. Kakiuchi, and H. Watanabe, “Rheological images of poly(vinyl chloride) gels. 5. Effect of molecular weight distribution,” Macromolecules, vol. 31, no. 21, 1998. [CrossRef]

- L. Li and Y. Aoki, “Rheological images of poly(vinyl chloride) gels. 3. Elasticity evolution and the scaling law beyond the sol-gel transition,” Macromolecules, vol. 31, no. 3, 1998. [CrossRef]

- Y. Aoki, L. Li, and M. Kakiuchi, “Rheological images of poly(vinyl chloride) Gels. 6. Effect of temperature,” Macromolecules, vol. 31, no. 23, 1998. [CrossRef]

- M. Kakiuchi, Y. Aoki, H. Watanabe, and K. Osaki, “Viscoelastic properties of poly(vinyl chloride) gels: Universality of gel elasticity,” Macromolecules, vol. 34, no. 9, 2001. [CrossRef]

- L. Li and Y. Aoki, “Rheological images of poly(vinyl chloride) gels. 1. The dependence of sol-gel transition on concentation,” Macromolecules, vol. 30, no. 25, 1997. [CrossRef]

| Plasticizer Ratio |

Elastic Modulus (Pa) |

|---|---|

| P2 | 288751 |

| P4 | 56058 |

| P6 | 24707 |

| P8 | 11047 |

| Plasticizer Ratio |

Poisson’s Ratio |

|---|---|

| P2 | 0.42 |

| P4 | 0.43 |

| P6 | 0.37 |

| P8 | 0.35 |

| Plasticizer Ratio | Coefficient of Determination | |

|---|---|---|

| P2 | 0.9972 | [85622, 5800, -272] |

| P4 | 0.9971 | [9061, 3175, -116] |

| P6 | 0.9946 | [3106, 1545, -40] |

| P8 | 0.9952 | [1365, 593, -5.99] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).