Introduction

Old age is defined as the last stage of development in a person’s life. There are several criteria for defining old age: chronological, i.e., adults aged 65 and over; by social roles and status, especially after retirement; or functional, i.e., when a decline in physical and cognitive abilities becomes apparent [

1]. Ageing is accompanied by numerous challenges, such as retirement, the onset of disease, functional limitations, loss of social roles and the death of a spouse, friends, siblings or other close relatives. These life changes can affect both the structural and functional aspects of social networks in older adults, often negatively impacting the individual’s quality of life [

2].

Ageing is a dynamic process characterised by changes over time and is generally divided into biological, psychological and social ageing. Biological ageing refers to the gradual decline in physiological functions. Psychological ageing includes changes in cognitive and emotional functioning, while social ageing refers to changes in a person’s interaction with their environment and social roles [

3].

The loss of meaningful life roles, fewer social ties and less social activity can lead to social isolation and subsequent feelings of loneliness in older adults. Loneliness has profound effects on physical and psychological well-being. It is associated with memory loss, general unhappiness, loss of self-esteem, depression, high blood pressure and other chronic illnesses. These factors contribute to a reduced quality of life and increased mortality. Negative emotions associated with loneliness can arise from a discrepancy between the desired and perceived quality and quantity of social relationships or from a subjective feeling of social isolation and lack of meaningful social connections [

3]. A recent meta-analysis from Sulandari et al. confirmed that loneliness is strongly associated with lower life satisfaction and quality of life in older adults, underscoring its importance as a public health issue [

4]. A recent global meta-analysis involving over 1.25 million older adults reported a prevalence of loneliness of 27.6%, and identified loneliness as significantly associated with reduced quality of life and social support levels [

5]. Moreover, a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies found that loneliness is associated with a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality (HR 1.14; 95% CI 1.10–1.18), highlighting its detrimental impact on both survival and well-being in older adults [

6]. A systematic literature review focusing on community-dwelling older adults emphasizes that loneliness in this population is linked to reductions in subjective well-being and that different types of loneliness yield varied adverse outcomes [

4,

5,

6,

7].

The subjective experience of loneliness is strongly linked to the perceived quality of life. Quality of life is a multidimensional and complex concept that is often difficult to define precisely. It generally refers to a person’s subjective evaluation of their living conditions, which is characterised by their interaction with their physical and social environment. This assessment is influenced by personality traits, attitudes, values and beliefs and represents the individual’s unique perception of quality of life [

8]. Objective indicators of quality of life include economic stability, housing conditions, access to healthcare and social support systems. The concept can therefore be broadly defined as the subjective assessment of the impact of external conditions on personal life [

9].

Quality of Life in Old Age: A Multidimensional Concept and Its Challenges

Quality of life (QoL) in the context of older adults refers to a multidimensional concept that encompasses various aspects such as physical health, psychological well-being, autonomy, social relationships, personal beliefs and the environment in which a person lives. Although QoL is commonly understood as a subjective experience, it can also be assessed by objective indicators such as access to healthcare, safety and socioeconomic conditions [

10]. As the proportion of older adults in the population increases, the importance of health and social care systems in maintaining QoL becomes increasingly apparent.

In institutional care settings, QoL is largely dependent on interpersonal relationships with staff, participation in decision-making, and access to meaningful activities that maintain a person’s dignity and identity [

10]. For older adults living in the community, life satisfaction is enhanced by strong interpersonal relationships, social participation and maintaining independence. In addition, factors such as gender, education level and marital status have been shown to influence perceptions of life satisfaction in old age [

11].

Loneliness as a Challenge for Public Health

Loneliness is a growing problem in the older population and is considered one of the most important predictors of reduced psychosocial well-being. A distinction is made between emotional loneliness, which refers to the lack of close emotional ties, and social loneliness, which refers to the lack of broader social networks. Loneliness is usually described as a distressing experience resulting from the perceived inadequacy of social relationships and serves as a subjective indicator of an unmet need for social support [

12].

According to research by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), factors such as being alone, deteriorating health, loss of a partner and social exclusion contribute significantly to loneliness in old age [

13]. Loneliness has a negative impact on physical health through mechanisms such as suppression of the immune system, increased blood pressure and even an increased mortality rate. Psychologically, it contributes to the development of depression, anxiety, hopelessness and a diminished sense of purpose in life. As a result, loneliness is increasingly recognised as a public health problem on a par with smoking or physical inactivity [

14]. Particularly vulnerable groups include widowed older women, adults living in rural areas and those with lower levels of education. Interventions aimed at improving social engagement, increasing digital literacy and promoting group or intergenerational activities have been shown to have positive results in reducing loneliness [

15].

The relationship Between Loneliness and Quality Of Life

A growing body of research confirms a strong, bidirectional relationship between loneliness and QoL in old age. Older adults who report higher levels of loneliness tend to have lower levels of life satisfaction, emotional stability and optimism, as well as a more pessimistic outlook for the future [

13]. Conversely, a reduced QoL - particularly if it is due to poor health, financial insecurity and social exclusion - can exacerbate feelings of loneliness.

Correlational and longitudinal studies have shown that persistent loneliness is an important predictor of declining QoL in old age, particularly in the absence of adequate social support networks. The UNFPA [

13] has reported that older adults with higher levels of social isolation consistently score lower on all dimensions of QoL than their socially engaged peers. In response, a wide range of interventions focusing on social integration and emotional support have been developed to address this issue. These efforts not only improve individual wellbeing but also help to reduce pressure on health and social care systems [

16].

Purpose and Objective

The main objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between the subjective experience of loneliness and the quality of life of older adults in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County. Primorje-Gorski Kotar County is a multicultural region of Croatia with both urban and rural areas, and a relatively high proportion of older adults, partly due to retirement migration. This demographic context makes it a relevant setting for studying well-being and loneliness in ageing populations. The specific objectives were as follows:

-To investigate the influence of loneliness on the assessment of QoL in older adults;

-To investigate the experience of loneliness and QoL in older adults as a function of gender;

-To examine the experience of loneliness and QoL in older adults as a function of the living arrangments in which they live.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The study involved 153 males and females over the age of 63 living in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County. Sample size: No a priori power analysis was performed, but the final sample (N = 153) is comparable to similar studies in the field. Missing data: Minor discrepancies in the number of participants across analyses reflect incomplete responses on some items, which precluded calculation of composite scores in those cases. The inclusion criteria were persons living in their own household, able to care for themselves and able to perform activities of daily living. The exclusion criteria included mental disorders and physical illnesses that affect the ageing process, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Procedure

Data were collected using the paper-and-pencil method. The questionnaire included the Personal Wellbeing Index – Adult (PWI-A) and the short form of the UCLA Loneliness Scale [

17,

18]. The PWI-A and the short form of the UCLA Loneliness Scale were administered in validated Croatian translations, published and used in prior research. The distribution of the questionnaire was supported by the Belveder-Kozala Pensioners’ Club, the Čavle Pensioners’ Club, the Zamet Pensioners’ Club, the Orehovica Health Centre and the Kozala Health Centre.

Measurements

Personal Wellbeing Index for Adults (PWI-A)

The Personal Wellbeing Index (PWI-A) can consist of either seven or eight questions. The standard version contains seven core questions relating to satisfaction with different areas of life. The PWI-A scale, which is available for academic use, consists of seven items that assess satisfaction with QoL in the following areas: health, standard of living, life achievements, relationships with family and friends, personal security, sense of belonging to the community and future security. Respondents are asked: “How satisfied are you with…?”.

The answers are given on an 11-point scale (from 0 to 10), where 0 stands for “completely dissatisfied” and 10 for “completely satisfied”. The index may only be completed by the respondent him/herself. It is not permitted for another person to fill in the questions for the respondent. The average value of all areas results in the PWI-A [

17,

19].

UCLA Loneliness Scale (UCLA Scale)

Both unidimensional and multidimensional scales are used to measure loneliness. More specifically, several instruments have been developed based on two main criteria: (1) the duration of loneliness and (2) the dimensionality of loneliness. In terms of duration, the New York University Loneliness Scale (NYU) developed by Rubinstein and Shaver measures loneliness as a personality trait. The most used instrument is the UCLA Loneliness Scale [

20], which measures global loneliness as a state. However, numerous studies have shown that the scale is not unifactorial, as the number of factors varies in different samples. In addition, the results on gender differences in loneliness are inconsistent across different groups. Therefore, Allen and Oshagan [

21] proposed a short form of the UCLA scale consisting of seven items.

The short form of the UCLA scale, which is also available for academic use, was developed to measure the subjective experience of loneliness and social isolation. The scale consists of seven items, which are answered on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 means “does not apply to me at all” and 5 means “applies to me” completely” The score is calculated from the sum of the scores of all items divided by the number of items. A total score above three indicates a higher level of perceived loneliness, while a score below three reflects a lower level of perceived loneliness [

18,

22].

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations) were used to illustrate the basic characteristics of the sample. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to analyses the relationship between loneliness and QoL. An independent samples t-test was used to compare QoL and loneliness according to gender and to analyse differences between groups according to living arrangments. Data were analysed using Statistica version 14.0.0.15 [

23], with statistical significance p-values < 0.05. Reliability: In our sample, internal consistency was satisfactory (PWI-A α = 0.85; UCLA short form α = 0.81). This approach allows a precise and objective assessment of the impact of loneliness on the QoL of older adults and the investigation of group differences.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

The data on the gender distribution of the 153 participants show that 69.9% were female and 30.1% male (

Table 1). In response to the question “Who do you live with?”, 33.3% of participants stated that they lived alone, while 66.7% stated that they lived with household members (such as partners, children or other family members). The mean age of participants was 75.32 years with a standard deviation of 7.226. The youngest participant was 63 years old, while the oldest was 96 years old.

These characteristics provide a context for understanding the sample and may be important in interpreting differences in subjective well-being and loneliness in subsequent analyses.

The highest mean scores in

Table 2 for the PWI-A responses were recorded for the item “How satisfied are you with your personal relationships?” where the mean score was 8.22 with a standard deviation of 1.88, followed by “How satisfied are you with what you achieve in life?” with a mean score of 7.97 and a standard deviation of 1.80. The lowest mean response values were observed for the item “How satisfied are you with your health?” with a mean value of 6.03 and a standard deviation of 2.34, followed by “How satisfied are you with your future security?” with a mean value of 6.99 and a standard deviation of 2.09.

The highest mean score for UCLA in

Table 2 was for the item “I do not share my thoughts and ideas with others”, with a mean score of 2.77 and a standard deviation of 1.41. The lowest mean response value was obtained for the item “I am unhappy because I withdraw so much” with a mean of 1.90 and a standard deviation of 1.21. The mean value of the overall UCLA score was 2.52 ± 1.33

The data obtained for the observed factors show that the mean score of the PWI-A scale is 74.46, with a standard deviation of 15.40, while the mean score of the UCLA scale is 34.00, with a standard deviation of 27.14.

According to the categories of the PWI-A questionnaire, 6.7% (N=10) of the 150 respondents reported a “challenged” level of subjective well-being, 28.7% (N=43) reported an “impaired” level, while 64.7% (N=97) reported a “normal” level of subjective well-being.

When analysing the significance level for the questions “How satisfied are you with how safe you feel?”, “How satisfied are you with your sense of belonging to the community?” and “I do not share my thoughts and ideas with others”,” the significance value of the chi-square test is p1 < 0.05.

For the questions “Nobody knows me well” and “Adults are around me, but not with me”,” the chi-square test also shows a significance value of p2 < 0.05, which indicates a statistically significant difference in relation to the participants’ circumstances.

According to the significance values in

Table 3, a p-value of more than 0.05 (p > 0.05) indicates that the data follows a normal distribution, while a p-value of less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) indicates a deviation from normality. As the significance level in the Shapiro-Wilk test is not above 0.05 for either scale, the –normal distribution was not confirmed. Therefore, non-parametric statistical methods were used in the subsequent analysis.

Correlation Analysis

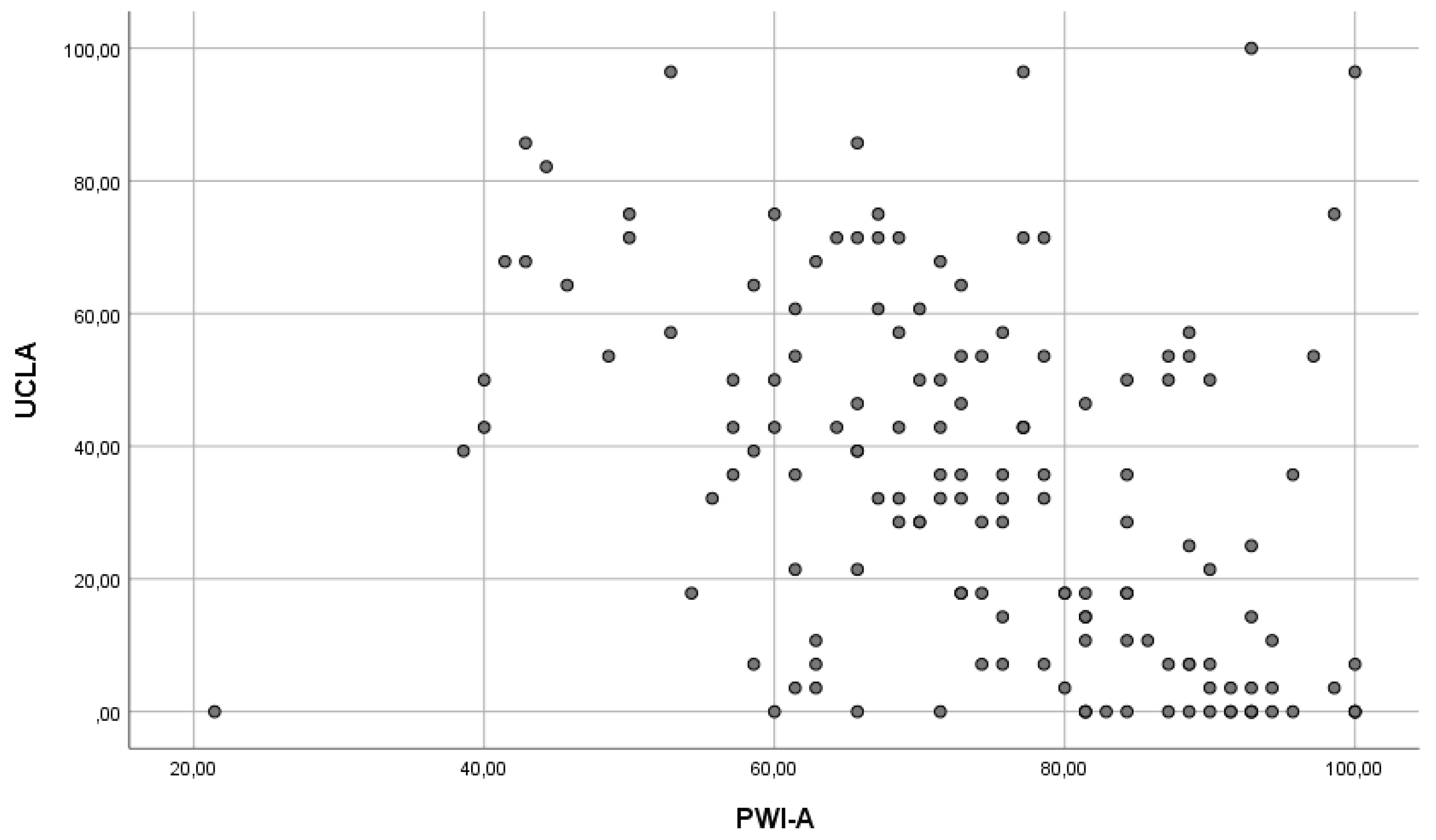

To analyse the relationship between subjective well-being and perceived loneliness, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated. A moderate negative correlation was found between PWI-A and UCLA scores (r = -0.448, p < 0.01), suggesting that higher levels of subjective well-being are associated with lower levels of perceived loneliness.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of the correlation between PWI-A and UCLA.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of the correlation between PWI-A and UCLA.

Differences in Subjective Well-Being and Loneliness by Gender and Living Arrangments

The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to analyses the differences in subjective well-being (PWI-A) and loneliness (UCLA) according to gender and living arrangments. This non-parametric test was used due to the lack of normal distribution of the data (

Table 3).

Using the significance value for the PWI-A variable (

Table 4), it was found that p < 0.05, indicating that women scored significantly higher on subjective well-being than men (p = 0.036). For loneliness, the gender difference was not statistically significant. The rank analysis showed that females had a higher mean rank, suggesting that their ratings for the observed factor were higher compared to the male participants.

Differences in Subjective Well-Being and Loneliness According to Living Arrangments

When examining the significant values for the analyses factors depending on who the participants live with (

Table 5), it was found that there was no statistically significant difference in the responses based on living arrangements (p > 0.05).

Discussion

Our findings confirm that loneliness is significantly and negatively correlated with subjective well-being in older adults. This aligns with previous studies that highlight loneliness as a major factor in reduced life satisfaction. A significant negative correlation was found between the PWI-A and the UCLA Loneliness Scale (r = –0.448; p < 0.01), reflecting previous findings that loneliness is one of the most important predictors of reduced life satisfaction in later life [

24,

25,

26,

27].

Contrary to some expectations, women in our sample reported higher subjective well-being than men, while no significant gender difference in loneliness was found. This nuanced result underscores the importance of context and requires further research. Our findings confirm the well-documented gender differences in well-being and loneliness, which are corroborated by studies from Sri Lanka [

28] and China [

29].

We did not observe significant differences in loneliness or well-being according to living arrangement. While prior studies often report that living alone is associated with greater loneliness, our findings suggest that other factors, such as quality of social relationships, may be more important. Prior research—such as the work of Kousha et al. [

30] suggests that living alone is frequently associated with greater loneliness and lower QoL. This discrepancy could be due to sample characteristics or cultural factors and emphasises the need for future studies with larger and more representative populations.

Although this study did not find statistically significant differences regarding cohabitation, previous research consistently shows that living alone is often associated with increased loneliness and lower quality of life (QoL) [

28,

31]. Studies by Tourani et al. [

27] and Shpakou et al. [

32] highlight that subjective well-being is strongly influenced by relationship satisfaction and the availability of emotional support, even in institutional settings. Similarly, Wijesiri et al. [

28] found that older adults living with their spouse and children report better psychological well-being and overall QoL. These findings underscore the important role of family dynamics and emotional connectedness. In collectivist cultures in particular, as emphasized by Kousha et al. [

30], family support serves as a vital protective factor against loneliness and psychological distress. Overall, the evidence suggests that social relationships and living arrangement remain fundamental determinants of well-being in later life.

An insightful contribution from Xie et al. [

29] reveals that subjective age—how old individuals feel rather than their chronological age—is directly related to loneliness. This relationship is mediated by resilience and self-esteem: those who feel younger tend to be more resilient and possess higher self-esteem, which in turn buffers against loneliness and enhances psychological well-being.

Although these individual factors were not the primary focus of Shpakou et al. [

32], their work underlines the influence of environmental and institutional settings on loneliness and well-being. Our findings, which show that satisfaction with social relationships contributes positively to overall well-being, are consistent with this emphasis on social context [

24].

Recent international studies further support our results. Attafuah et al. [

33] emphasize that accessible healthcare, financial independence, religious commitment, and strong family support systems improve older adults’ QoL, particularly in low-resource urban areas. Similarly, Stevens [

34] discusses the emotional burden of loneliness among older women, while Newman-Norlund et al. [

35] highlight the profound psychosocial consequences of situational isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Loneliness is increasingly recognized as a multidimensional and cumulative phenomenon. It is not only defined by the absence of social contact but also by dissatisfaction with existing relationships and the perceived loss of meaningful societal roles [

29,

34]. Xie et al. [

29] demonstrate that resilience and self-esteem serve not only as protective factors but also as mediators that help older adults cope with age-related transitions.

Finally, the broader literature indicates that loneliness is not only a psychological concern but also a significant health risk. It has been linked to cardiovascular disease, cognitive decline, sleep disturbances, and even increased mortality [

36,

37,

38]. Given its multifaceted impact on physical, emotional, and social health, loneliness should be addressed as a serious public health issue rather than merely a symptom of ageing.

Limitations: Results are based on self-report measures and a sample that, while adequate, may not fully capture all subgroups. We did not control for age or other covariates. Regression analyses could provide further insight into interactions between gender, age, and living arrangements.

Conclusions

Loneliness has a significant negative impact on the subjective assessment of quality of life in older adults. Gender differences were found only for subjective well-being, with women reporting higher well-being than men, while no significant gender differences were found for loneliness. Living arrangement did not significantly influence either outcome.

No statistically significant differences in loneliness or QoL were found in relation to living arrangement, i.e., who the participants live with. It was originally hypothesised that people living alone would report higher levels of loneliness and lower perceived QoL.

Several limitations should be noted. Firstly, although a random sample was used in the study, this limits the generalisability of the results, particularly due to contextual and demographic specificities. Secondly, the use of self-report may have led to biases, including social desirability and recall errors, especially for sensitive topics such as loneliness and mental health. Third, due to the non-normal distribution of several variables, non-parametric statistical methods were used, which may reduce the sensitivity of the analyses [

39]. The results of the UCLA scale are presented as mean values; however, due to the lack of regression analyses, the question of the interaction between gender, living arrangements, and loneliness remains open. Finally, cultural factors specific to the local context may limit the transferability of the results to broader populations.

Nevertheless, this study makes an important contribution to understanding the impact of loneliness on older adults’s QoL. By integrating global perspectives with locally anchored data, it emphasizes the importance of culturally sensitive, gender-specific and holistic approaches to tackling loneliness in older populations.

Future research should aim to use larger and more representative samples to improve the generalizability of results. Longitudinal studies would be particularly valuable to track changes over time and identify causal relationships. In addition, further research should investigate the role of protective psychosocial factors - such as resilience, self-esteem and social support networks - as possible moderators of loneliness and well-being. Intervention-based studies are also needed to assess the effectiveness of targeted programs to reduce loneliness and improve subjective well-being, particularly in older adults living alone or in residential care. Particular attention should be paid to fostering intergenerational relationships, promoting resilience and tackling stigmatization associated with ageing and loneliness.

Declaration of Helsinki STROBE reporting guidelines

This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. The STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology) guideline was followed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, LJ and MS; Methodology, MS and ŽJ; Software, LJ; Validation, BM, MS and ŽJ; Formal Analysis, LJ and KG; Investigation, LJ; Resources, MS; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, LJ and MS; Writing—Review & Editing, KG, MS, BM, ŽJ; Supervision, ŽJ; Project Administration, LJ; All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Studies of the University of Rijeka (Date 28. 05. 2025., number 600-05/25-01/120). In the introductory part of the questionnaire, participants were given clear information about the purpose of the study, its target population, the anonymity of participation and the use of personal data for research purposes only. Participants were also instructed on how to complete the questionnaire. Regarding the informed consent statement, informed consent was obtained from all individuals involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The study dataset is available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the elderly participants for their kindness and willingness to participate in the study and complete the questionnaire. Special thanks also go to the Belveder-Kozala Pensioners’ Club, the Čavle Pensioners’ Club, the Zamet Pensioners’ Club, the Orehovica Health Centre and the Kozala Health Centre for their valuable help in distributing the questionnaire.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vuletić G, et al. Quality of life and health. Osijek: Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, J. J. Strossmayer University; 2011. Available from: http://bib.irb.hr/datoteka/592441.KVALITETA_IVOTA_I_ZDRAVLJE.pdf Accessed 2025 January 15.

- Torres Z, Oliver A, Tomás JM. Understanding the effect of loneliness on quality of life in older adults from longitudinal approaches. Psychosoc Interv [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 10];33(3):171–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a11. Accessed 2025 January 10. [CrossRef]

- Brajković L. Indicators of life satisfaction in older adulthood [dissertation]. Zagreb: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Medicine; 2010.

- Sulandari S, Okely JA, Bandelow S, Farrow M, Galvin JE, Fielding R, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between physical capability, social support, loneliness, mental health, and life satisfaction in older adults. Gerontologist. 2024;64(5):e295–309. [CrossRef]

- Salari N, Kazeminia M, Shohaimi S, Vaisi-Raygani A, Mohammadi M, Hallajzadeh J, et al. The global prevalence and associated factors of loneliness among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2025;12:104. [CrossRef]

- Nakou A, Daskalopoulou C, Niarchou M, Stefanis C, Chrousos G, Chrysohoou C. Loneliness, social isolation, and mortality in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2025;29(3):399–412. [CrossRef]

- Di Perna G, Rossi E, Chiorri C. A systematic literature review of loneliness in community-dwelling older adults. Soc Sci. 2023;12(1):21. [CrossRef]

- Slavuj L. Objective and subjective indicators in the study of the concept of quality of life. Geoadria. 2012;17(1):73–92. Available from: https://doi.org/10.15291/geoadria.238. Accessed 2025 January 10. [CrossRef]

- Vuletić G, Stapić M. Quality of life and loneliness among elderly people. Klinička psihologija [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2025 Jun 10];6(1–2):61–61. Available from: https://hrcak.srce.hr/167454 Accessed 2025 January 15.

- Salić N. Quality of life of older persons in institutional care from the user’s perspective. Soc Humanit Stud. 2024;7(1):1067–96. [CrossRef]

- Jovičić A. Quality of life of pensioners in the Republic of Croatia: Differences by gender, education and marital status [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372666333. Accessed 2025 February 6.

- Ellwardt L, Aartsen M, Deeg D, Steverink N. Does loneliness mediate the relation between social support and cognitive functioning in later life? Soc Sci Med. 2013;98:116–24. [CrossRef]

- UNFPA. Loneliness and social isolation of older adults in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: Survey among people aged 65+. Sarajevo: UNFPA; 2021. Available from: https://ba.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/survey_on_loneliness_final_bcs_0.pdf. Accessed 2024 October 15.

- CRORIS. Loneliness of older adults as an increasingly important public health issue [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://www.croris.hr/crosbi/publikacija/prilog-skup/679059. Accessed 2024 October 15.

- Gardiner C, Geldenhuys G, Gott M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older adults: an integrative review. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(2):147–57. [CrossRef]

- Lacković-Grgin K. Loneliness – phenomenology, theories and research. Jastrebarsko: Naklada Slap; 2008.

- Cummins RA. Personal Wellbeing Index Manual: 6th Edition, Version 2. Geelong: Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University; 2024. Available from: https://www.acqol.com.au/uploads/pwi-a/pwi-a-english.pdf. Accessed 2024 October 10.

- Lacković-Grgin K, et al. Collection of psychological scales and questionnaires. Zadar: University of Zadar, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences; 2019. p. 77–9. Available from: https://morepress.unizd.hr/books/index.php/press/catalog/view/28/24/365. Accessed 2024 October 20.

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39:472–80. [CrossRef]

- Allen RL, Oshagan H. The UCLA Loneliness Scale: Invariance of social structural characteristics. Pers Individ Dif. 1995;19(2):185–95. [CrossRef]

- TIBCO Software Inc. Statistica (Version 14.0.0.15) [computer software]. 2020. Available from: https://www.tibco.com/products/tibco-statistica. Accessed 2025 March 10.

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta-analysis. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 2001;23(4):245–66. [CrossRef]

- Victor CR, Bowling A. A longitudinal analysis of loneliness among older adults in Great Britain. J Psychol. 2012;146(3):313–31. [CrossRef]

- Cattan M, White M, Bond J, Learmouth A. Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older adults: A systematic review. Ageing Soc. 2005;25(1):41–67. [CrossRef]

- Grover S. Loneliness in older adults: Impact and interventions. Indian J Psychiatry. 2022;64(2):98–106. [CrossRef]

- Fokkema T, De Jong Gierveld J, Dykstra PA. Cross-national differences in older adult loneliness. J Psychol. 2012;146(1–2):201–28. [CrossRef]

- Tourani S, Behzadifar M, Martini M, Aryankhesal A, Taheri Mirghaed M, Salemi M, et al. Health-related quality of life among healthy elderly Iranians: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):18. [CrossRef]

- Wijesiri HSMSK, Wasalathanthri S, De Silva Weliange S, Ranathunga I, Sivayogan S. Quality of life and its associated factors among home-dwelling older adults residing in the District of Colombo, Sri Lanka: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e068773. [CrossRef]

- Xie J, Zhang B, Yao Z, Zhang W, Wang J, Zhao C, et al. The effect of subjective age on loneliness in older adults: The chain mediating role of resilience and self-esteem. Front Public Health. 2022;10:907934. [CrossRef]

- Kousha M, Shahraki M, Askarizadeh G, Mohammadi M, Abdollahi E. Loneliness and quality of life in older adults living alone. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):401. [CrossRef]

- Zarei M, Bakhshi S, Bahrami F, Ghaedi Heidari F. Relationship between loneliness and quality of life in older adults: The mediating role of social support and depression. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):281. [CrossRef]

- Shpakou A, Klimatckaia L, Furiaeva T, Piatrou S, Zaitseva O. Ageism and loneliness in the subjective perceptions of elderly people from nursing homes and households. Fam Med Prim Care Rev. 2021;23(4):475–480. [CrossRef]

- Attafuah PYA, Everink I, Abuosi AA, Birt L, van der Vorst M, Stiekema AP, et al. Quality of life of older adults and associated factors in Ghanaian urban slums: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e057264. [CrossRef]

- Stevens N. Combating loneliness: A friendship enrichment programme for older women. Ageing Soc. 2001;21(2):183–202. [CrossRef]

- Newman-Norlund RD, Ball A, Beeler A, et al. Situational social isolation during COVID-19 in older adults. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2022;8:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227–37. [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet. 2018;391(10119):426. [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq R, Shoib S, Shah T, Mushtaq S. Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health: A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(9):WE01–WE04. [CrossRef]

- Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 4th ed. London: SAGE Publications; 2013.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).