1. Introduction

Cardiac masses are rare but significant findings during cardiac radiographic examinations. Even if they have a prevalence of 0.002% at autopsy, they play a crucial role causing alteration of hemodynamics and increasing the risk of cardiac arrhythmias [

1].

They can be classified as benign or malignant: approximately 75% of cardiac masses are benign. Benign masses include myxomas (50%), papillary fibroelastomas (20%), lipomas (15-20%), and hemangiomas (4%). Among malignant tumors, over 95% are sarcomas, while 5% are lymphomas [

2].

Also metastases and pseudotumors - such as valvular alterations that can be confused with masses, must be considered [

3].

The assessment of the cardiac masses requires a systematic approach [

4,

5]. First, it is necessary to assess the location of the mass determining whether it resides in the left or right heart, atrium or ventricle, or it is extracardiac, such as the pericardium or great vessels. Next, specify the site of attachment—whether it lies on the interatrial or interventricular septum, on the roof or lateral wall of the atrium, or on the ventricular free wall [

4,

6].

The morphology of the mass should also be thoroughly described detailing its dimensions, characterizing its shape as either regular or irregular, and noting its mode of attachment (sessile, pedunculated, or polylobate). Furthermore, evaluate the margins—whether the edge is well defined or irregular—and assess the mass's mobility through dynamic cine imaging. Comparing the mass's signal intensity with that of normal myocardium is essential [

4].

The possible infiltration into adjacent tissues may be indicated by the disruption of neighboring anatomical structures—such as interruptions in the typical epicardial and endocardial contours caused by extension into the pericardium and myocardium—or by a focal increase in myocardial thickness compared to adjacent segments. When this thickening is associated with abnormal kinesis in a region that does not follow a typical coronary distribution, an infiltrative behavior becomes more likely than ischemia [

5].

The analysis of contrast behavior, typically based on early and late gadolinium enhancement (EGE and LGE), provides essential insights into the vascularity and tissue composition of the lesion [

7]. All these imaging observations should be complemented by a thorough evaluation of the cardiac chambers regarding both their size and function [

5].

Traditionally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for cardiac masses detection [

4]. However, recent technological advancements in ionizing ray technologies, such as dual-energy CT and photon counting, have enabled the confident discovery, evaluation, and identification of cardiac masses through CT examinations [

8].

The advantages of CT scans over MRI include greater availability, shorter exam and reporting times, and broader accessibility. Moreover, CT is frequently used as a screening tool to identify early risks of cardiac ischemia and for follow-up after cardiac stent implantation and coronary bypass surgery. This widespread use allows for the incidental detection of silent cardiac masses and the early diagnosis and treatment of malignant pathologies [

9].

In this review, we present a series of cardiac masses, highlighting their imaging characteristics on CT and MRI, illustrated with cases from our routine clinical practice.

1.1. Computed Tomography

Computed Tomography (CT) is a Second-Level investigation and is widely available in many areas and allows for a comprehensive morphological evaluation of the heart. It is quick to perform, as the patient does not need to remain in one position for as long as during an MRI exam. However, this method has few contraindications such as contrast medium allergy and renal failure [

10,

11].

CT scanning protocols can be adapted to each patient, ensuring a personalized and optimal examination. The exam is conducted with cardiac synchronization, using electrodes to transmit an ECG trace to the machine, which allows for image acquisition when the heart is "stationary" [

12].

In addition to providing a panoramic view of the heart, CT offers higher resolution, enabling the analysis of structures smaller than a millimeter in diameter using the most advanced technologies available today [

10]. The use of contrast medium, dual-energy, and late iodine enhancement protocols further allows for accurate tissue characterization, though slightly inferior to that of MRI [

13].

Acquiring images of the heart throughout the entire cardiac cycle also permits the generation of CINE images, albeit with a temporal resolution lower than that of ultrasound.

1.1.1. CT Acquisition Technique

Achieving a high-quality coronary CT depends equally on the scanner hardware, the chosen acquisition protocol and careful patient preparation. Coronary arteries are narrow lumens tethered to a continuously beating heart, so you need submillimetric spatial resolution (about 0.5–0.6 mm) combined with ultra-fast data capture during a single breath-hold [

14].

Spatial resolution is driven by detector width, while temporal resolution hinges on its rotation speed. Thanks to 180° reconstruction algorithms in modern systems, each image slice is acquired with just a half-turn of the gantry—in effect, the temporal resolution equals half the full-rotation time [

13].

In Dual-Energy CT scanners, two X-ray sources sit 90° apart and fire alternately, slicing the required rotation into quarters. That yields a temporal resolution on the order of 80–85 ms. ECG gating is then used to lock image acquisition to the ideal cardiac phase [

13,

15,

16].

Finally, to visualize the tiny, tortuous coronary branches in any plane, it’s crucial to generate isotropic voxels—identical dimensions on all three axes—by employing very thin slice thicknesses and precise gantry mechanics [

17].

1.1.2. Temporal Resolution

Temporal resolution is based on the need to obtain clear images, avoiding the blurring effect, which results in a lack of detail definition [

18]. The elements that affect temporal resolution include rotation time, the reconstruction algorithm, heart rate, and cardio synchronization [

19].

Heart rate is crucial because the cardiac image needs to be acquired during an R-R interval. This interval must be long enough for the scanner to acquire an image within it. Systole coincides with the R wave, while telediastole is the phase before the next R wave. We use acquisition during telediastole because it is the phase during which the heart remains still for the longest period, resulting in a better image. However, telediastole is also the phase most affected by an increase in the patient's heart rate. In cases of high heart rate, it is preferable to use reconstruction in the systolic phase instead of the meso-telediastolic phase, as the systolic phase varies least in duration with changes in the patient's heart rate [

18].

Cardiosynchronization plays a fundamental role and influences the choice of gating between retrospective and prospective [

19]. Prospective acquisition involves selecting the phase of the cardiac cycle in which the machine will acquire and reconstruct images before starting the exam. This method, used with scanners featuring a 16 cm panel, has the advantage of delivering a smaller dose and is suitable for young patients with regular heart rates. During prospective acquisition, the scanner activates the X-ray tube only during the pre-established acquisition phase.

Retrospective gating involves acquiring images throughout the entire cardiac cycle, allowing the best phase for reconstruction to be chosen a posteriori. This method enables correction of artifacts if there is a rhythm alteration during acquisition but has the disadvantage of exposing the patient to radiation for the entire duration of the acquisition [

19].

1.1.3. The Role of Pitch and Radiation Dose Modulation

In coronary CT imaging, table movement—expressed as pitch—is critical: on scanners with 4–8 cm detector panels that can’t cover the entire cardiac volume in a single heartbeat, operators maintain a pitch under 1 to ensure overlap between successive rotations and avoid gaps in ultra-thin-slice reconstructions; high pitch is reserved solely for flash acquisitions.

Retrospective ECG-gated studies demand rigorous dose reduction through tube current modulation (mA) tailored to both patient size and cardiac phase—ramping up mA during the diagnostic sweet spot of 40 – 80 % of the cycle (late systole to mid-to-end diastole) and lowering it outside this window, thus producing high-definition frames when it matters and tolerable noise elsewhere. Protocols must adapt to individual physiology: in patients with stents or arrhythmia, phase-based mA modulation often becomes unfeasible, requiring a steady high current throughout to minimize artifacts, and kilovoltage must be increased for obese individuals or those with stents to maintain adequate image contrast and penetration [

19].

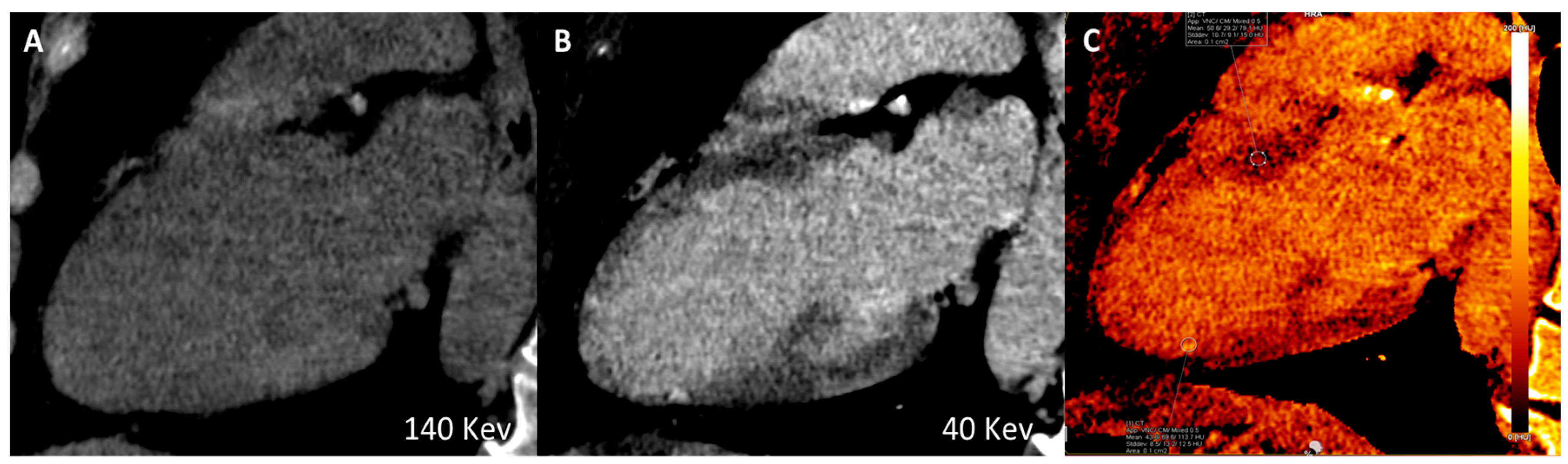

1.1.4. Dual Energy Acquisition and Late Enhancement Scans

New-generation CT systems leverage Dual Energy acquisition for detailed tissue characterization, allowing the creation of virtual non-contrast datasets and the detection of myocardial fibrosis—an indicator of ischemia, myocarditis or cardiomyopathy. They also support late-enhancement imaging: after the initial contrast bolus, a second injection is given and, following an eight-minute delay, new scans are acquired so that fibrotic myocardium—having a higher affinity for the contrast agent—stands out against normal myocardial tissue (

Figure 1) [

20,

21].

1.2. Magnetic Resonance

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a second-level imaging technique. Similar to CT scan, it needs cardiac synchronization, but it requires more time to perform [

22]. It offers less panoramic coverage and with less detailed resolution but it compensates with superior temporal resolution, allowing for high accuracy cine sequences. Moreover, tissue characterization is more precise with MRI [

19]. The multiparametric imaging capabilities, including T1 and T2 mapping and contrast agent administration, provide a comprehensive evaluation of various lesions [

23,

24].

MR Acquisition Technique

To obtain these comprehensive insights, a rigorous MRI protocol is required. ECG-gated balanced steady-state free precession sequences (b-SSFP) are fundamental for producing high-quality cine images of cardiac motion.

In addition to allowing the evaluation of ventricular function and cardiac dimensions by providing high-resolution images of the heart's movements during the cardiac cycle, cine sequences are also essential for evaluating the morphology and mobility of cardiac masses, providing detailed images that help distinguish between solid and fluid masses. In particular, they allow the evaluation of the hemodynamic impact of the mass, highlighting any obstructions to blood flow. Cine sequences also play an important role in monitoring a mass over time; any changes in movement and morphology can help assess the effectiveness of treatment or make a differential diagnosis [

5,

25].

Black-blood T1- and T2-weighted imaging precisely defines mass borders, while T1-weighted fat-saturation sequences mute adipose signal to sharpen lesion contrast; first-pass perfusion scans then reveal vascular perfusion patterns, and segmented phase-sensitive inversion recovery captures both early and delayed gadolinium uptake, which is crucial for highlighting scar or fibrotic tissue as hyperintense areas against normal myocardium. Late gadolinium enhancement not only pinpoints tissue damage but also distinguishes malignant masses—characterized by intense, heterogeneous uptake from high vascularity and necrosis—from benign lesions that enhance more uniformly, and it further refines the delineation of lesion margins [

5].

T1 mapping provides voxel-by-voxel measurements of longitudinal relaxation times, showing that fibrotic myocardium has longer T1 than healthy tissue and thereby enabling lesion classification—neoplastic masses typically yield lower T1 values, while thrombi and inflammatory lesions fall in between. Conversely, T2 mapping quantifies transverse relaxation to assess water content, unmasking myocardial edema as a sign of inflammation or acute injury and highlighting fluid-filled or necrotic cores within masses, thus distinguishing solid from liquid components. A comprehensive cardiac MRI always includes pericardial assessment to detect, characterize and grade any effusive collection [

5].

Table 1.

CMR Protocol.

| Sequence |

Technique |

Slice Thickness |

Acquisition |

Notes |

| Axial T1w |

T1-weighted FSE |

8-10 mm (4-6 mm for high-resolution) |

Free-breathing acquisition covering the whole thoracic region |

Anatomical reference |

| Cine |

SSFP |

- |

VLA, 4-chamber, SAX, plus two custom orthogonal planes |

Detailed visualization of masses |

| T1-w |

Double IR FSE T1-w |

6 mm |

Optimized imaging planes identified earlier |

Repeat fat sat for enhanced contrast |

| T2-w |

Triple IR FSE T2-w |

6 mm |

Same imaging planes as previously determined |

Helpful for edema |

| First-Pass Perfusion |

Gd contrast-enhanced imaging |

- |

Optimized imaging plane for mass visualization |

Contrast dosage: 0.05-0.1 mmol/kg |

| Early Gadolinium Enhancement (EGE) |

Segmented T1-w double IR FSE |

6 mm |

Optimal planes selected earlier |

TI set at 450-500 ms |

| Post-Gd T1-w |

Double IR FSE T1-w post-Gd |

6 mm |

Optimal imaging planes chosen earlier |

Assessing contrast uptake in tissues |

| Late Gadolinium Enhancement (LGE) |

Segmented T1-weighted double IR FSE |

6 mm |

SAX for LV coverage, plus other optimized imaging planes |

TI determined using Look-Locker technique |

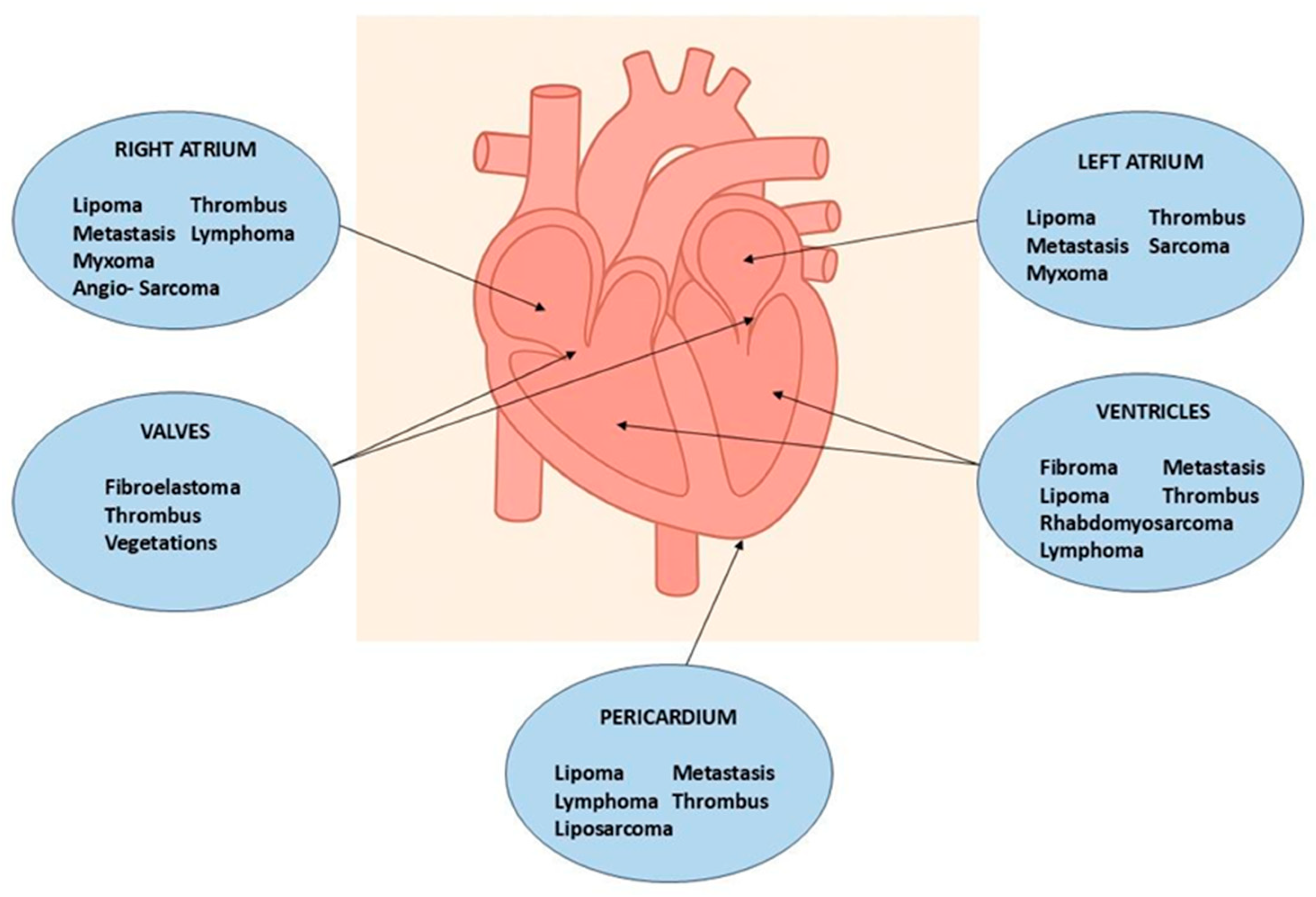

2. Systematic Approach for Diagnosing Cardiac Masses

To improve the diagnosis of cardiac masses, a systematic approach is advisable [

26]. The correct evaluation of a mass must consider the patient's age, location (

Figure 2), and radiological characteristics, utilizing both morphological and contrast aspects. Specifically, when evaluating a tumor mass, it is important to assess the probability of it being benign or malignant. Secondary lesions, such as metastases, are the most common diagnosis. In the case of a secondary mass, identifying the primary tumor through a total body CT scan is necessary. For primary masses, it's notable that 90% of cardiac tumors are benign and only 10% are malignant. Some types of cardiac masses are more frequent in pediatric or adult populations, their frequency of presentation is summarized in

Table 2 [

27].

3. Pseudotumors

Pseudotumors, the most frequent “masses” seen on cardiac imaging, chiefly include thrombi and benign anatomic variants —whether vascular quirks or chamber morphology differences—can masquerade as pathology and lead to diagnostic pitfalls [

28].

3.1. Thrombi

Thrombi reveal themselves as non-opacified (“vacuum”) areas after contrast injection (

Figure 3)—critical to recognize for proper treatment—and are classically found in the left atrium of patients with atrial fibrillation. On CT they appear as hypodense, non-enhancing lesions [

29]; on MRI their signal shifts with age: acute clots display intermediate intensity on both T1 and T2 (due to oxyhemoglobin), subacute thrombi become T1-dark and T2-bright as hemoglobin converts to methemoglobin and draws in water, and chronic, fibrosed clots lose water, appear dark on both T1 and T2, and generally lack contrast uptake (though longstanding fibrotic thrombi can show rim enhancement on delayed sequences), similar to normal fibrotic tissue [

2,

3,

12,

30].

3.2. Pericardial Cysts

A pericardial cyst (

Figure 4) is a congenital benign structure typically found in the right pericardiophrenic angle. It is usually an incidental finding, often discovered during an X-ray, and is generally small and asymptomatic. However, if very large, it can compress adjacent structures, both mediastinal and pulmonary. The appearance is typical of a cyst: hypodense on CT, hypointense on T1-weighted MRI, hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI, and it shows no contrast enhancement [

3,

9,

22].

3.3. Caseous Calcification of the Mitral Valve

Caseous calcification of the mitral valve is a rare variant involving the posterior mitral annulus in the atrioventricular groove. It is a necrotic mass with a core made of fat and chronic inflammatory infiltrate, surrounded by fibrocalcified material. This rare finding can be confused with a cardiac tumor or thrombus. On CT, it appears as a hyperdense calcium deposit surrounded by hypodense material. In MRI, early stages show hyperintensity on both T1 and T2 due to the high fluid content and liquefied necrosis, with the calcified area appearing intense. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) shows a hyperintense rim with fibrous content and an avascular center due to caseous necrosis (

Figure 5) [

2,

3].

4. Anatomical Variants

Anatomical variants are normal cardiac structures located in atypical places or remnants from embryonic development. These can be mistaken for thrombi or tumors. Most diagnostic errors occur with ultrasound, whereas CT and MRI, providing panoramic views, allow for better identification of these structures. Among the most common anatomical variants are the Eustachian valve, the Thebesian valve, and the Coumadin Ridge [

31].

The Coumadin ridge appears as a band-shaped fold on the lateral wall of the left atrium between the left pulmonary vein and the atrial appendage—formed by their fusion and enclosing the Marshall ligament (an autonomic nerve bundle) plus a small sinoatrial node—and often produces a Q-shaped echocardiographic sign (a narrow proximal segment with a bulbous tip); on MRI, its characteristic signal on gradient-echo sequences and contrast enhancement differentiate it from thrombus or tumor [

32].

Thebesian valve, or coronary sinus valve, is a delicate flap at the coronary sinus ostium in the right atrium, a vestige of the embryonic sinoatrial valve [

33].

The Eustachian valve, or inferior vena cava valve, is a variable-thickness ridge at the IVC–right atrial junction that once shunted oxygenated fetal blood through the foramen ovale; if incompletely resorbed it may mimic a thrombus or atrial mass and can complicate atrial septal defect or patent foramen ovale interventions [

34].

5. Benign Tumors

5.1. Myxomas

Myxomas are the most frequent primary cardiac tumors, occurring almost exclusively in patients aged 40–70 and accounting for about 25–50 % of benign cardiac masses [

28]. These lesions are usually solitary, measure 1–15 cm, and arise from the interatrial septum near the fossa ovalis—75 % in the left atrium, 20 % in the right atrium and 5 % in the ventricles. Grossly, they present as well-defined, smooth, oval formations often attached by a narrow stalk. Approximately one-quarter of individuals remain asymptomatic, with myxomas detected incidentally, while the remainder experience the classic triad of intracardiac obstruction, embolic events and systemic symptoms. Left-sided tumors obstructing the mitral valve provoke dyspnea, orthopnea and pulmonary edema; right-sided lesions lead to signs of right-heart failure. Because most myxomas originate in the left atrium, embolic complications—cerebral, coronary or peripheral—are predominantly systemic [

2].

Patients with atrial myxomas often present non-specific systemic signs—weight loss, fatigue and weakness—that can mimic infective endocarditis, and roughly 20% develop arrhythmias [

3].

On CT these tumors appear as hypodense masses attached to the interatrial septum, with repeated intralesional hemorrhages sometimes leading to dystrophic calcifications, particularly in right atrial lesions; when pedunculated, they may disturb valvular motion and even induce mitral prolapse (

Figure 6).

MRI reveals the heterogeneous aspect: most myxomas are T1-hypointense, with hyperintense hemorrhagic areas, and contrast uptake differentiates them from thrombi [

26].

5.2. Paraganglioma

Paraganglioma is a rare neuroendocrine tumor arising from paraganglia, clusters of autonomic nervous system cells located along nerve pathways [

36]. These tumors are classified as sympathetic or parasympathetic. Cardiac paragangliomas belong to the sympathetic subtype and typically secrete catecholamines, including adrenaline and noradrenaline. They are part of the mediastinal paragangliomas, and they can arise in multiple intracardiac and pericardial sites, such as the epicardium, atria, interatrial septum, or ventricle [

37].

On CT imaging, cardiac paragangliomas demonstrate intense, heterogeneous contrast enhancement [

38].

On MRI, they exhibit a “salt-and-pepper” appearance on T1-weighted sequences—hyperintense parenchymal areas interspersed with signal voids from vascular flow. On T2-weighted images, they show marked hyperintensity, and after contrast administration they show prolonged and heterogeneous enhancement (

Figure 7) [

39].

5.3. Cardiac Lipomas

Cardiac lipomas—though rare—are the most common non-myxomatous primary heart tumors: soft, slow-growing lesions that often reach large size without causing symptoms and typically sit extracardially within the pericardial sac. On echocardiography, it appears as a hyperechogenic mass due to its high fat content (

Figure 8) [

3].

MRI provides superior delineation of a cardiac lipoma’s course alongside the coronary arteries compared with CT. On CT these tumors manifest as uniform, hypodense masses situated either within the cardiac chambers or the pericardial space, whereas on MRI they appear vividly hyperintense on T1-weighted images and then lose signal on fat-saturation sequences [

22,

40,

41].

5.4. Fibroelastoma

Papillary fibroelastoma (

Figure 9), though an uncommon primary cardiac neoplasm overall, is the most frequent valvular tumor—comprising about 75 % of such lesions—and shows a clear male predominance; histologically it forms delicate papillary fronds built on a fibrous core surrounded by loose connective tissue, occasionally interspersed with elastic fibers, all sheathed by a single layer of hypertrophied endothelium. Approximately 80% of fibroelastomas are found in the aortic or mitral valves, with rarer occurrences in the tricuspid or pulmonary valves and even rarer involvement of the mitral chordae tendineae [

3].

On CT, fibroelastomas appear as small hypodense masses with irregular margins. On MRI, they present as well-defined, pedunculated masses of about 1.5 cm, showing an iso-hyperintense signal in T1 and T2 sequences and may exhibit mobility in CINE sequences. The characteristic appearance on echocardiogram is similar to a sea anemone. Its location can lead to the formation of thrombotic endocarditis components [

22,

42].

5.5. Cardiac Fibroma

Cardiac fibroma is a benign congenital tumor. It can be discovered during fetal life and is the second most common benign primary cardiac tumor in children after rhabdomyoma, being the second most frequent fetal cardiac tumor. Cardiac fibromas are often associated with arrhythmias and compromission of the hemodynamics of the heart, and can lead to congestive heart failure [

43]. However, it is not uncommon for patients to be asymptomatic [

22].

Cardiac fibromas (

Figure 10) are composed of fibroblasts surrounded by large quantities of collagen, forming a well-defined, solitary, endomyocardial tumor mass with smooth edges, usually greater than 5 cm in diameter, and can even obliterate the entire ventricular cavity. They most commonly originate from the free wall of the left ventricle, the interventricular septum, or the free wall of the right ventricle. Although cystic foci, hemorrhages, or necrosis are rare, calcifications are commonly found and are a typical manifestation of Gorlin syndrome [

3,

44].

On CT, fibromas appear as homogeneous masses with a density similar to cardiac muscle, rarely infiltrative, with homogeneous or finely inhomogeneous contrast enhancement. In MRI, due to their fibrotic and dense nature, fibromas usually appear hypointense on T2-weighted images and relatively isointense to cardiac muscle on T1-weighted images [

3,

45].

These tumors are typically homogeneous, poorly vascularized lesions that show minimal early contrast uptake yet stand out as marked hyperenhancement on late gadolinium sequences [

3].

5.6. Rhabdomyoma

Cardiac rhabdomyomas—the most common fetal cardiac tumor and closely linked to tuberous sclerosis—are benign, well-circumscribed, solid, non-encapsulated masses most often in the left ventricle but able to arise anywhere in the myocardium. Usually asymptomatic, they can occasionally obstruct the left ventricular outflow tract or trigger treatment-resistant arrhythmias. On echocardiography they appear as hyperechoic nodules adherent to the myocardium, with small lesions sometimes simulating diffuse thickening, while MRI demonstrates isointense signal on T1-weighted images, hyperintensity on T2-weighted sequences, and characteristically no contrast enhancement post-gadolinium [

2].

5.7. Hemangioma

Cardiac hemangiomas are rare vascular malformations made up of clusters of endothelial-lined channels separated by thin fibrous and fatty septa. Typically asymptomatic, they can nonetheless cause pericardial effusion, innocuous murmurs, arrhythmias, tamponade, cardiac arrest or even sudden death. Histologically they fall into capillary, cavernous or arteriovenous types and may involve any layer of the heart muscle, most commonly the left atrium. On echocardiography they appear as hyperechogenic masses; CT at baseline shows heterogeneous density that becomes markedly hyperenhanced after intravenous contrast; and MRI reveals a heterogeneous lesion that is iso- to hyperintense on T1-weighted sequences, intensely hyperintense on T2-weighted images, with equally heterogeneous contrast uptake [

22,

46,

47].

6. Malignant Tumors

Primary malignancies of the heart are exceptionally uncommon, whereas secondary manifestations from tumors elsewhere occur with far greater frequency; of those rare primary cardiac cancers, roughly 95 % are sarcomas, and the balance comprises lymphomas or pericardial mesotheliomas [

2,

3,

22,

27].

6.1. Sarcoma

Cardiac angiosarcoma (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12) is the most common malignant tumor of the adult heart. Patients usually present with symptoms and signs of heart failure or cardiac tamponade. These tumors typically originate from the right atrium and extend to the pericardium. There are two morphological types of sarcoma:

Well-defined mass: Protrudes into the cardiac chamber, appears on CT as a hypodense mass with irregular or nodular margins, usually originating from the free wall of the right atrium, and shows heterogeneous contrast uptake.

Diffuse infiltrative mass: Extends towards the pericardium, which can be obliterated by necrotic or hemorrhagic tumor. The prognosis is unfavorable because the pathology is usually asymptomatic until advanced and often metastatic [

3,

22,

27].

Histologically, angiosarcomas exhibit sheets of highly proliferative, anaplastic endothelial cells that invade perivascular spaces in a disorganized fashion, leading to frequent hemorrhage and necrosis; on MRI they appear heterogeneously signal-intense on both T1- and T2-weighted images, with irregular contrast uptake and patchy late gadolinium enhancement corresponding to fibrotic islands [

27].

6.2. Cardiac Rhabdomyosarcoma

Cardiac rhabdomyosarcoma —the most common malignant heart tumor in pediatric patients—can originate anywhere in the myocardium but often involves the valves and presents as multiple nodules that invariably infiltrate myocardial tissue and may extend into the pericardium; CT depicts these masses as hypodense lesions with smooth or lobulated margins within the chambers, while MRI shows isointense signal on T1, hyperintensity on T2, and typically homogeneous contrast enhancement with occasional central necrotic cores [

22,

48,

49].

There are also undifferentiated sarcomas, which make up about one-third of all cardiac sarcomas. Like angiosarcoma, they can appear as focal or infiltrative masses with necrosis and hemorrhages, resulting in variable cardiac MRI appearances. However, unlike angiosarcoma, they more often originate from the left atrium [

3].

6.3. Cardiac Lymphoma

Cardiac lymphoma is a rare tumor originating from the myocardium or pericardium. It can be classified as primary or secondary. Primary cardiac lymphoma is rare, representing only 10% of primary malignant cardiac tumors, whereas secondary cardiac involvement from systemic lymphoma is more common. Both forms are more prevalent in patients with HIV immunodeficiency [

3].

Clinically, lymphoma manifests symptoms such as dyspnea, edema, or arrhythmia, and pericardial effusion may pose a risk of cardiac tamponade. An intracavitary mass or pericardial effusion may be identified on an echocardiogram [

27].

On CT, cardiac lymphoma appears as multiple well-circumscribed polypoid masses or an infiltrative but poorly defined lesion, usually within the right atrium with pericardial effusion. It typically has an isodense or hypodense appearance compared to the myocardium, with rare areas of necrosis and inhomogeneous contrast enhancement [

22]. CMR imaging is essential in early diagnosis and assessment of response to therapy. In CMR examination, primary cardiac lymphomas appear as slightly heterogeneous isointense masses in T1-weighted images and iso- to hyperintense in T2-weighted sequences compared to normal myocardium. First-pass perfusion reveals mild homogeneous enhancement. LGE sequences show heterogeneous contrast uptake with less enhancement in central regions [

50,

51]

6.4. Metastases

Cardiac metastases are secondary tumors involving the heart, representing the spread of tumors via the lymphatic and blood vessels. Although rare, cardiac metastases are much more common than primary cardiac tumors, with a ratio of about 30:1 and a frequency of 18% in oncological patients. The most common primary tumors that metastasize to the heart include lung cancer, breast cancer, renal cancer, ovarian cancer, pleural mesothelioma, malignant melanoma (

Figure 13ta), chordoma (

Figure 14) and lymphoma [

52,

53].

Cardiac metastases are usually not identified during the initial staging of a tumor and may remain undetected for years, often diagnosed at autopsy. Clinically, patients can have dyspnea, congestive heart failure, malignant pericardial effusion, and nonspecific symptoms such as infarctions, arrhythmias, hypoxia, and hypotension [

3].

Typical features of cardiac metastasis include diffuse thickening of the pericardium, nodular infiltration of the myocardium, and associated desmoplastic reactions, leading to the onset of constrictive pericarditis. The occurrence of a single mass with endocardial or intracavitary involvement is much less common [

22].

On X-ray examination, the findings are not specific and may include cardiomegaly due to pericardial effusion or cardiac congestion and gross mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Echocardiogram is the first level method, but being operator dependent and with a limited field of view, although it is suitable for identifying pericardial effusion, it often does not identify ventricular masses. Transesophageal ultrasound allows the identification of subcentimetric masses located in the atria or near the valves. It is obviously necessary to resort to a second level investigation in order to characterize these findings [

3].

On CT, multiple masses or hypodense nodules can be identified at the basic exam with possible calcifications and inhomogeneous contrast enhancement; they can show signs of diffuse infiltration. Pericardial or epicardial masses can be associated with pericardial effusion usually of complex type, it is important to notice the remodeling of the cardiac chambers and the interventricular septum. It is also necessary to look for locoregional lymph nodes, and a diffuse thickening of the pericardium. The pericardium In fact is the most commonly affected site. The myocardium is usually invaded directly by the pericardium. The exception is melanoma which is typical to attack the myocardium primarily by blood.

MRI usually shows hypointense images in T1 and hyperintense in T2, with avid contrast enhancement after administration. Malignant melanoma shows T1 hyperintensity due to the paramagnetic properties of melanin, low intensity in , T2 images and heterogeneous appearance on LGE imaging [

54]. These characteristics allow for a specific diagnosis without the need for a biopsy [

3].

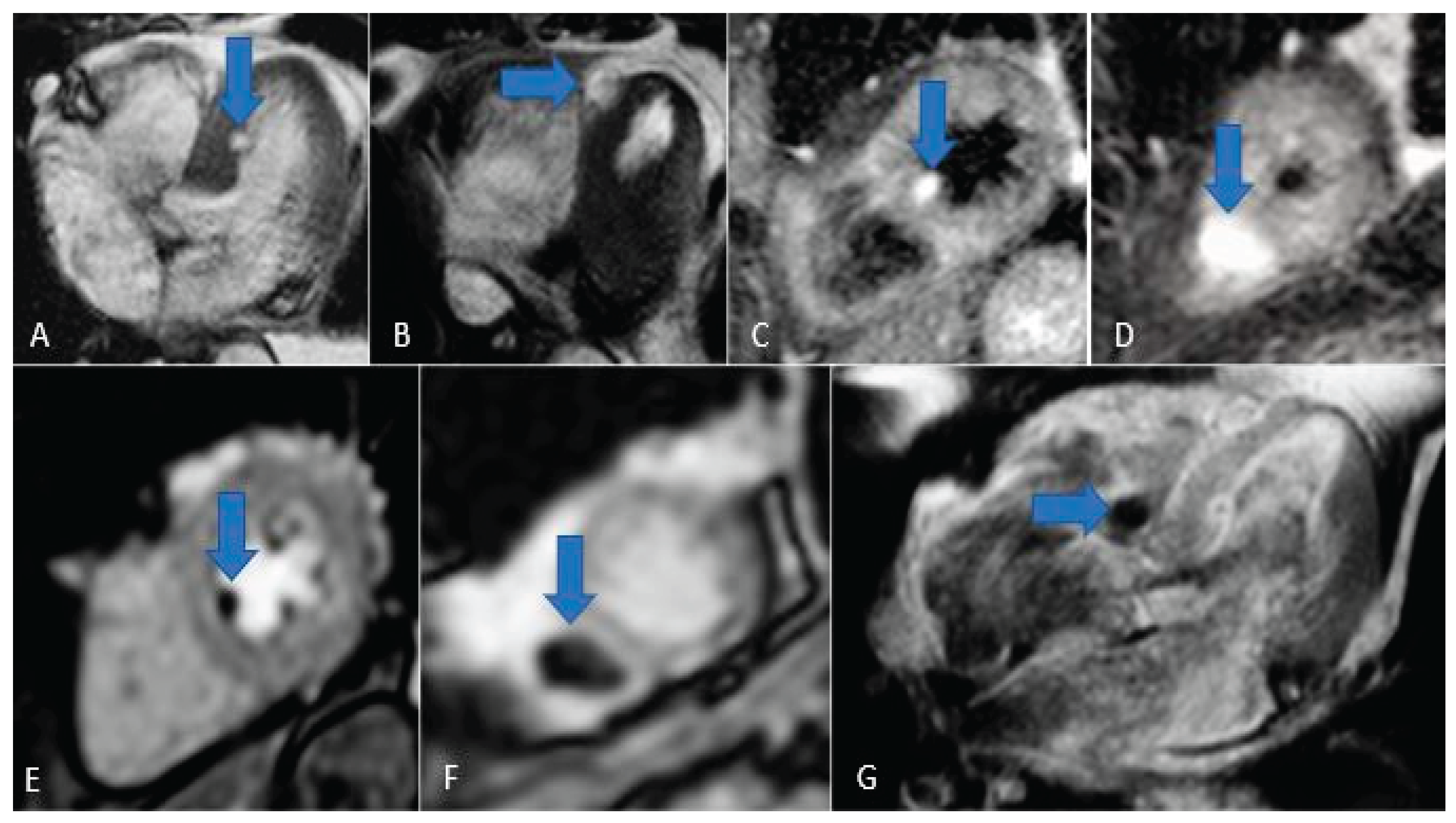

Figure 15.

Chordoma metastasis. Note the hyperintensity in T2/STIR sequences (A, B, C and D) and the hypointensity in perfusion and LGE sequences (E, F and G).

Figure 15.

Chordoma metastasis. Note the hyperintensity in T2/STIR sequences (A, B, C and D) and the hypointensity in perfusion and LGE sequences (E, F and G).

7. Conclusions

Diagnosing cardiac masses is among the most significant advances in radiology. Modern imaging modalities, CT and MRI, enable a comprehensive evaluation of the myocardium and have expanded radiologists’ capabilities once the exclusive domain of echocardiography far beyond its limits. Early and accurate detection facilitates targeted therapies and improves patient survival.

Distinguishing benign from malignant lesions, as well as differentiating true masses from anatomical variants and pseudotumors, is essential for optimal clinical management. A systematic approach, carefully assessing lesion location, morphology, and imaging characteristics, provides a solid diagnostic framework. Cardiac-synchronized, contrast-enhanced studies further refine diagnostic accuracy and guide decisions on additional investigations. Magnetic resonance imaging in particular has revolutionized our ability to characterize cardiac pathology.

Because cardiac masses can disrupt the heart both in hemodynamics and electrical conduction, no lesion should be underestimated. Intracardiac thrombi, for example, can lead to coronary or extracardiac emboli with serious hemodynamic consequences, while benign tumors such as myxomas and papillary fibroelastomas may impair contractile function or provoke thrombogenesis.

In oncological patients, vigilance for cardiac metastases is mandatory. Prompt recognition of secondary lesions not only directs appropriate oncologic care but also preserves patients’ quality of life.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, B.M. and C.L.; methodology, S.P.; software, I.M..; validation, B.M., and C.L.; formal analysis, M.C..; investigation, R.T.; resources, F.D.; data curation, G.F.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.; writing—review and editing, S.P.; visualization, M.G.; supervision, I.M.; project administration, C.L.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Isobe, S. Murohara, T. Editorial: Cardiac tumors: Histopathological aspects and assessments with cardiac noninvasive imaging. J Cardiol Cases, 2015, 12, 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- Amano, J. Nakayama, J., Yoshimura, Y., Ikeda, U. Clinical classification of cardiovascular tumors and tumor-like lesions, and its incidences. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2013, 61, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, C. Rizzo, S., Valente, M., & Thiene, G. Cardiac masses and tumours. Heart, 2016, 102, 1230–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnes, J. Brink, M., Nijveldt, R.. How to evaluate cardiac masses by cardiovascular magnetic resonance parametric mapping? Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging., 2023, 24, 1605–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolisso, P., Bergamaschi, L., Angeli, F., Belmonte, M., Foà, A., Canton, L., Fedele, D., Armillotta, M., Sansonetti, A., Bodega, F., Amicone, S., Suma, N., Gallinoro, E., Attinà, D., Niro, F., Rucci, P., Gherbesi, E., Carugo, S., Musthaq, S., Baggiano, A., Pavon, A.G., Guglielmo, M., Conte, E., Andreini, D., Pontone, G., Lovato, L., Pizzi, C. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance to Predict Cardiac Mass Malignancy: The CMR Mass Score. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging, 2024, 17, e016115.

- Marano, R., Liguori, C., Savino, G., Merlino, B., Natale, L., Bonomo, L. (2011). Cardiac silhouette findings and mediastinal lines and stripes: radiograph and CT scan correlation. Chest, 2011, 139(5), 1186–1196.

- Chan, A. T., Fox, J., Perez Johnston, R., Kim, J., Brouwer, L. R., Grizzard, J., Kim, R. J., Matasar, M., Shia, J., Moskowitz, C. S., Steingart, R., Weinsaft, J. W. Late Gadolinium Enhancement Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Tissue Characterization for Cancer-Associated Cardiac Masses: Metabolic and Prognostic Manifestations in Relation to Whole-Body Positron Emission Tomography. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019, 8(10), e011709.

- Paolisso, P., Bergamaschi, L., Angeli, F., Belmonte, M., Foà, A., Canton, L., Fedele, D., Armillotta, M., Sansonetti, A., Bodega, F., Amicone, S., Suma, N., Gallinoro, E., Attinà, D., Niro, F., Rucci, P., Gherbesi, E., Carugo, S., Musthaq, S., Baggiano, A., Pavon, A.G., Guglielmo, M., Conte, E., Andreini, D., Pontone, G., Lovato, L., Pizzi, C. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance to Predict Cardiac Mass Malignancy: The CMR Mass Score. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging, 2024, 17(3), e016115.

- Cademartiri, F., Meloni, A., Pistoia, L., Degiorgi, G., Clemente, A., Gori, C., Positano, V., Celi, S., Berti, S., Emdin, M., Panetta, D., Menichetti, L., Punzo, B., Cavaliere, C., Bossone, E., Saba, L., Cau, R., Grutta, L., Maffei, E. Dual-Source Photon-Counting Computed Tomography-Part I: Clinical Overview of Cardiac CT and Coronary CT Angiography Applications J Clin Med, 2023, 12(11), 3627.

- Poterucha, T. J., Kochav, J., O'Connor, D. S., Rosner, G. F. Cardiac Tumors: Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Management. Curr Treat Options Oncol, 2019, 20(8), 66.

- Liguori, C., Tamburrini, S., Ferrandino, G., Leboffe, S., Rosano, N., Marano, I. Role of CT and MRI in Cardiac Emergencies. Tomography, 2022, 8(3), 1386–1400.

- Pontone, G., Rossi, A., Guglielmo, M., Dweck, M. R., Gaemperli, O., Nieman, K., Pugliese, F., Maurovich-Horvat, P., Gimelli, A., Cosyns, B., Achenbach, S. Clinical applications of cardiac computed tomography: a consensus paper of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging-part I. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging, 2022 , 23(3), 299-314.

- Rybicki, F.J. Sheth, T. Imaging Protocols for Cardiac CT. In MDCT:From Protocols to Practice; Kalra, M.K., Saini, S., Rubin, G.D., Eds. Springer, Milano, Italy, 2008, pp. 211-224.

- Tarkowski, P. Czekajska-Chehab, E. Dual-Energy Heart CT: Beyond Better Angiography-Review. J Clin Med. 2021, 10, 5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, A. C. Pourmorteza, A., Stutman, D., Bluemke, D. A., Lima, J. A. C. Next-Generation Hardware Advances in CT: Cardiac Applications. Radiology, 2021, 298, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liguori, C. Frauenfelder, G., Massaroni, C., Saccomandi, P., Giurazza, F., Pitocco, F., Marano, R., Schena, E. Emerging clinical applications of computed tomography. Med devices, 2015, 8, 265–278. [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, R., Harashima, S., Samejima, W., Shimizu, Y., Washizuka, F., Kariyasu, T., Nishikawa, M., Yamaguchi, H., Takeuchi, H., Machida, H. Acquisition and Reconstruction Techniques for Coronary CT Angiography: Current Status and Trends over the Past Decade. Radiographics, 2025, 45(7), e240083.

- Alizadeh, L. S. Vogl, T. J., Waldeck, S. S., Overhoff, D., D'Angelo, T., Martin, S. S., Yel, I., Gruenewald, L. D., Koch, V., Fulisch, F., & Booz, C. Dual-Energy CT in Cardiothoracic Imaging: Current Developments. Diagnostics (Basel), 2023, 13, 2116. [Google Scholar]

- Greuter, M. J. Flohr, T., van Ooijen, P. M., Oudkerk, M. A model for temporal resolution of multidetector computed tomography of coronary arteries in relation to rotation time, heart rate and reconstruction algorithm. Eur Radiol, 2007, 17, 784–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aversana, S. Ascione, R., De Giorgi, M., De Lucia, D. R., Cuocolo, R., Boccalatte, M., Sibilio, G., Napolitano, G., Muscogiuri, G., Sironi, S., Di Costanzo, G., Cavaglià, E., Imbriaco, M., Ponsiglione, A. Dual-Energy CT of the Heart: A Review. Journal of Imaging, 2022, 8, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vliegenthart, R., Pelgrim, G. J., Ebersberger, U., Rowe, G. W., Oudkerk, M., Schoepf, U. J. Dual-energy CT of the heart. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2012, 199(5 Suppl), S54–S63.

- Raff, G. L. Chinnaiyan, K. M., Cury, R. C., Garcia, M. T., Hecht, H. S., Hollander, J. E., O'Neil, B., Taylor, A. J., Hoffmann, U., Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. SCCT guidelines on the use of coronary computed tomographic angiography for patients presenting with acute chest pain to the emergency department: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr, 2014, 8, 254–271. [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, M. D'Angelo, T., Muscogiuri, G., Dell'aversana, S., Andreis, A., Carisio, A., Darvizeh, F., Tore, D., Pontone, G., & Faletti, R. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance of cardiac tumors and masses. World J Cardiol, 2021, 13, 628–649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dekkers, I. A. & Lamb, H. J. Clinical application and technical considerations of T1 & T2(*) mapping in cardiac, liver, and renal imaging. Br J Radiol, 2018, 91, 20170825. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, A., De Cobelli, F., Ironi, G., Marra, P., Canu, T., Mellone, R., Del Maschio, A. CMR in assessment of cardiac masses: primary benign tumors. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, 2014, 7(7), 733–736.

- Tyebally, S., Chen, D., Bhattacharyya, S., Mughrabi, A., Hussain, Z., Manisty, C., Westwood, M., Ghosh, A. K., Guha, A. Cardiac Tumors: JACC CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC CardioOncol, 2020, 2(2), 293–311.

- Bussani, R. Castrichini, M., Restivo, L., Fabris, E., Porcari, A., Ferro, F., Pivetta, A., Korcova, R., Cappelletto, C., Manca, P., Nuzzi, V., Bessi, R., Pagura, L., Massa, L., Sinagra, G. Cardiac Tumors: Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment. Curr Cardiol Rep, 2020, 22, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatram, P. Tumors of the Heart: Benign, Malignant and Metastatic. In Heart Diseases and Echocardiogram; Venkatram, P., Springer, Cham, Switzerland, 2024, pp. 297-310.

- Lorca, M. C. Chen, I., Jew, G., Furlani, A. C., Puri, S., Haramati, L. B., Chaturvedi, A., Velez, M. J., Chaturvedi, A. Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation of Cardiac Tumors: Updated 2021 WHO Tumor Classification. Radiographics, 2024, 44, e230126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnolo, P. Giglio, M., Di Marco, D., Cannaò, P. M., Agricola, E., Della Bella, P. E., Monti, C. B., Sardanelli, F. Diagnosis of left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with atrial fibrillation: delayed contrast-enhanced cardiac CT. Eur Radiol, 2021, 31, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparrow, P. J. Kurian, J. B., Jones, T. R., Sivananthan, M. U. MR imaging of cardiac tumors. Radiographics, 2005, 25, 1255–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broderick, L. S. Brooks, G. N., Kuhlman, J. E. Anatomic pitfalls of the heart and pericardium. Radiographics, 2005, 25, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodhi, A. M. Nguyen, T., Bianco, C., Movahed, A. Coumadin ridge: An incidental finding of a left atrial pseudotumor on transthoracic echocardiography. World J Clin Cases, 2015, 3, 831–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, G. S. Hill, A. J., Moisiuc, F., Krishnan, S. C. Variations in Thebesian valve anatomy and coronary sinus ostium: implications for invasive electrophysiology procedures. Europace, 2009, 11, 1188–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kydd, A. C., McNab, D., Calvert, P. A., Hoole, S. P., Rekhraj, S., Sievert, H., Shapiro, L. M., Rana, B. S.. The Eustachian ridge: not an innocent bystander. JACC. Cardiovasc Imaging, 2014, 7(10), 1062–1063.

- Saad, E. A. Mukherjee, T., Gandour, G., Fatayerji, N., Rammal, A., Samuel, P., Abdallah, N., Ashok, T. Cardiac myxomas: causes, presentations, diagnosis, and management. Ir J Med Sci, 2024, 193, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X. Meng, X., Zhang, T., Zhao, L., Liu, F., Han, X., Liu, Y., Zhu, H., Zhou, X., Miao, Q., Zhang, S. Diagnosis and Outcome of Cardiac Paragangliomas: A Retrospective Observational Cohort Study in China. Front Cardiovasc Med, 2022, 8, 780382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punzo, B. Tramontano, L., Clemente, A., Seitun, S., Maffei, E., Saba, L., Nicola De Cecco, C., Bossone, E., Narula, J., Cavaliere, C., Cademartiri, F. Advanced imaging of cardiac Paraganglioma: A systematic review. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc, 2024, 53, 101437. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, J. G., Gho, J. M. I. H., Budde, R. P. J., Hofland, J., Hirsch, A. Multimodality Imaging of Cardiac Paragangliomas. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging, 2023, 5(4), e230049.

- Shu, S., Yuan, H., Kong, X., Wang, J., Wang, J., Zheng, C. The value of multimodality imaging in diagnosis and treatment of cardiac lipoma. BMC Med Imaging, 2021, 21(1), 71.

- Shu, S., Wang, J., Zheng, C. From pathogenesis to treatment, a systemic review of cardiac lipoma. J Cardiothorac Surg, 2021, 16(1), 1.

- Miller, A. Perez, A., Pabba, S., Shetty, V. Aortic valve papillary fibroelastoma causing embolic strokes: a case report and review. Int Med Case Rep J, 2017, 10, 109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Finke, K. Gietzen, T., Steven, D., Baldus, S., Ten Freyhaus, H., Maintz, D., Pennig, L., Gietzen, C. Cardiac fibromas in adult patients: a case series focusing on rhythmology and radiographic features. Eur Heart J Case Rep, 2024, 8(8), ytae410.

- Jatti, K., Dhandapani, R., Sharma, V., Ruzsics, B. Cardiac Fibroma Presenting With Left Bundle Branch Block in an Adult With Gorlin Syndrome. Tex Heart Inst J, 2023, 50(1), e207247.

- Grunau, G. L., Leipsic, J. A., Sellers, S. L., Seidman, M. A. Cardiac Fibroma in an Adult AIRP Best Cases in Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. Radiographics, 2018 , 38(4), 1022–2026.

- Cresti, A., Chiavarelli, M., Munezero Butorano, M. A. G., Franci, L. Multimodality Imaging of a Silent Cardiac Hemangioma. J Cardiovasc Echogr, 2015, 25(1), 31–33.

- Munteanu, I. R., Novaconi, R. C., Merce, A. P., Dima, C. N., Falnita, L. S., Manzur, A. R., Streian, C. G., Feier, H. B. Cardiac Hemangiomas: A Five-Year Systematic Review of Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcomes. Cancers, 2025, 17(9), 1532.

- Rasekhi, R. T., Hosseini, N., Babapoor-Farrokhran, S., Farrokhran, A. B., Behzad, B. A rare case of primary adult cardiac rhabdomyosarcoma with lower extremity metastasis. Radiol Case Rep, 2023, 18(5), 1666–1670.

- de Vries, I. S. A., van Ewijk, R., Adriaansen, L. M. E., Bohte, A. E., Braat, A. J. A. T., Fajardo, R. D., Hiemcke-Jiwa, L. S., Hol, M. L. F., Ter Horst, S. A. J., de Keizer, B., Knops, R. R. G., Meister, M. T., Schoot, R. A., Smeele, L. E., van Scheltinga, S. T., Vaarwerk, B., Merks, J. H. M., van Rijn, R. R. Imaging in rhabdomyosarcoma: a patient journey. Pediatr Radiol, 2023, 53(4), 788–812.

- Asadian, S., Rezaeian, N., Hosseini, L., Toloueitabar, Y., Hemmati Komasi, M. M. The role of cardiac CT and MRI in the diagnosis and management of primary cardiac lymphoma: A comprehensive review. Trends Cardiovasc Med, 2022, 32(7), 408–420.

- Xie, D. Li, Y., Tang, C., Zou, Q. MRI features of primary cardiac lymphoma: case report and literature review. Front Oncol, 2025, 15, 1596237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenberger, J. P., 3rd, Reynolds, D. A., Keung, J., Keung, E., Carter, B. W. Metastasis to the Heart: A Radiologic Approach to Diagnosis With Pathologic Correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2016, 207(4), 764–772.

- Stein, H., Bellesheim, M., Ganz, M., Miller, D., Syed, S., Minter, B. Esophageal Cancer With Cardiac Metastasis: Approach to Cardiac Masses in Patients With a Known Malignancy. Cureus, 2024, 16(7), e64486.

- Kotaru, S. L., Po, J. R., Tatineni, V., Tokala, H., Kalavakunta, J. K. Melanoma With Cardiac Metastasis. Cureus, 2023, 15(9), e46230.l.

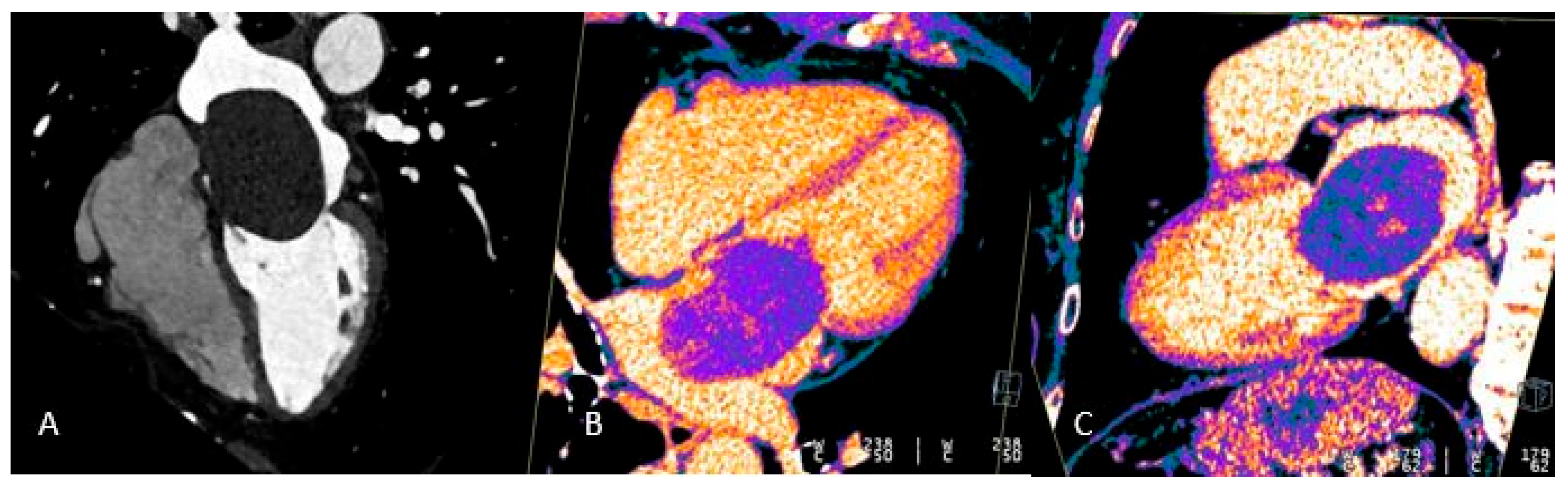

Figure 1.

Long-axis multiplanar reconstruction of the left ventricle acquired from a late iodine enhancement phase (8 minutes after dual-bolus injection) in a patient with hypokinesia of the inferior apical wall of the left ventricle. A) Virtual monoenergetic image 140 High-Kev. B) Virtual monoenergetic image 40 Low-Kev. C) Iodine Map image. A subendocardial iodine distribution (post ischemic scar) can be detected only using high tissue contrast low-Kev image and iodine map distribution recon.

Figure 1.

Long-axis multiplanar reconstruction of the left ventricle acquired from a late iodine enhancement phase (8 minutes after dual-bolus injection) in a patient with hypokinesia of the inferior apical wall of the left ventricle. A) Virtual monoenergetic image 140 High-Kev. B) Virtual monoenergetic image 40 Low-Kev. C) Iodine Map image. A subendocardial iodine distribution (post ischemic scar) can be detected only using high tissue contrast low-Kev image and iodine map distribution recon.

Figure 2.

Most frequent locations of cardiac masses.

Figure 2.

Most frequent locations of cardiac masses.

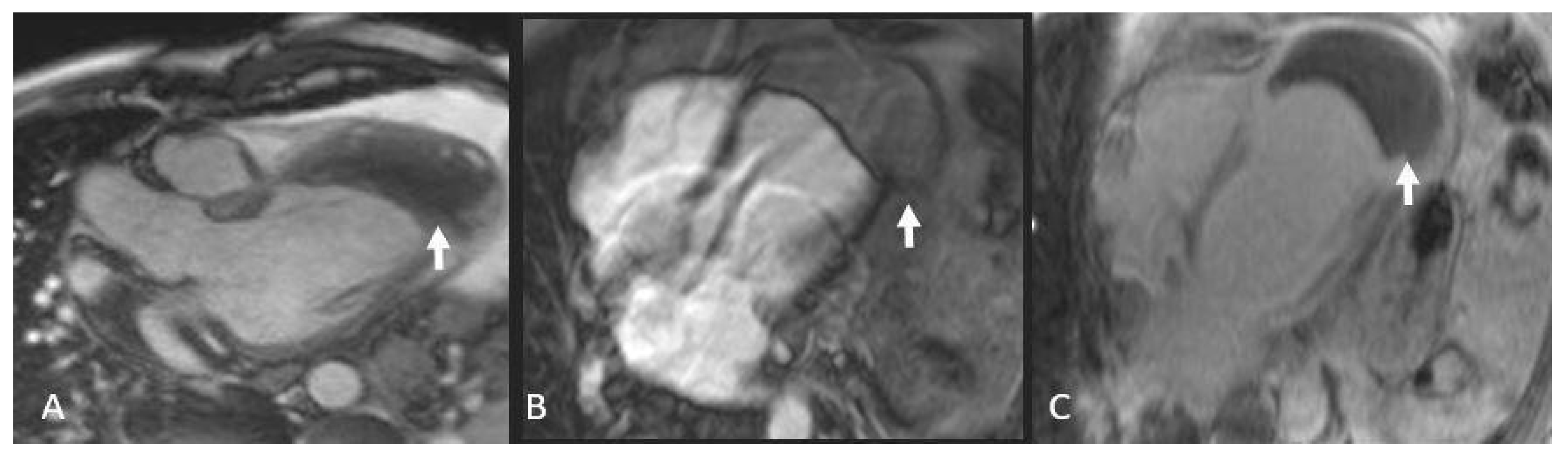

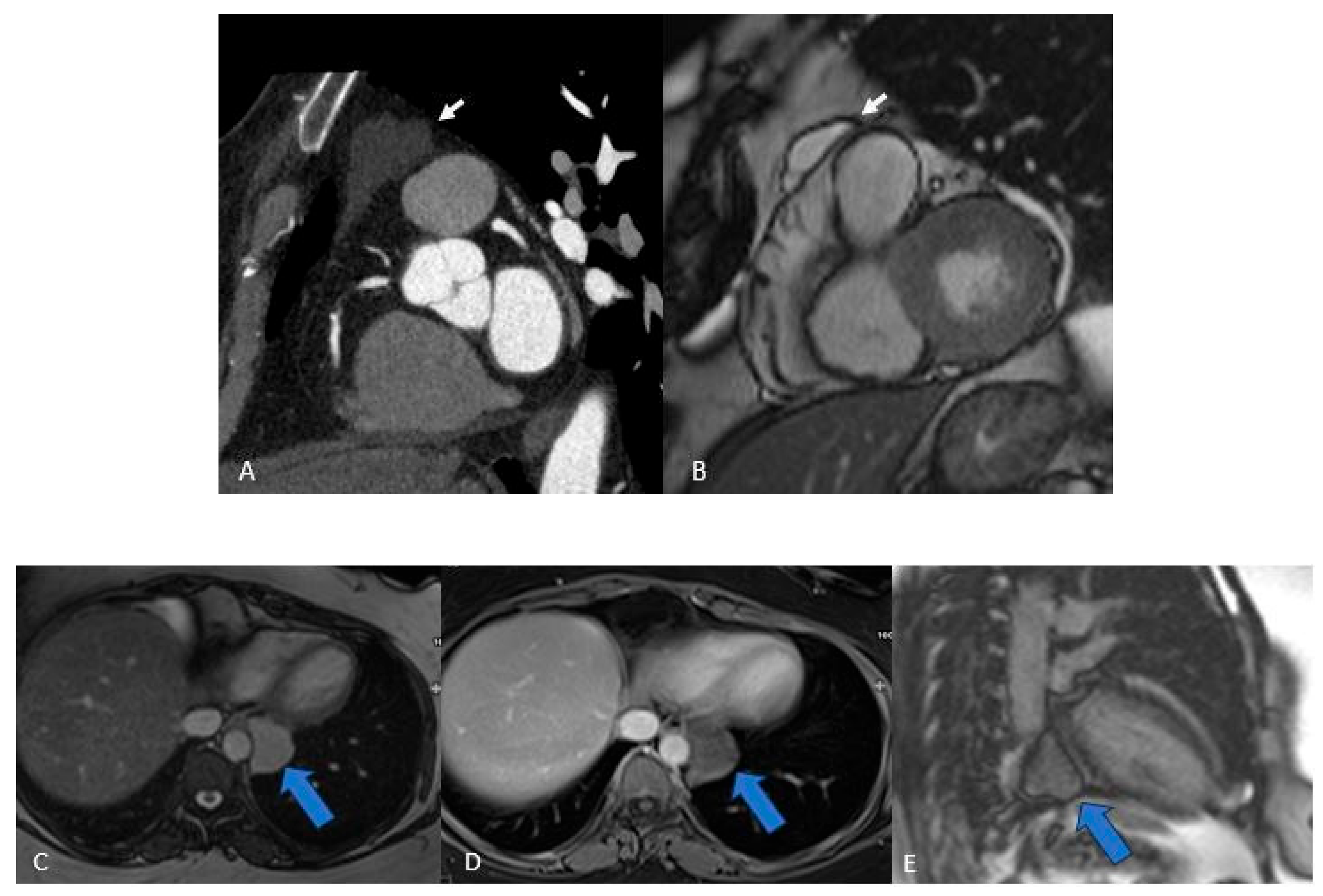

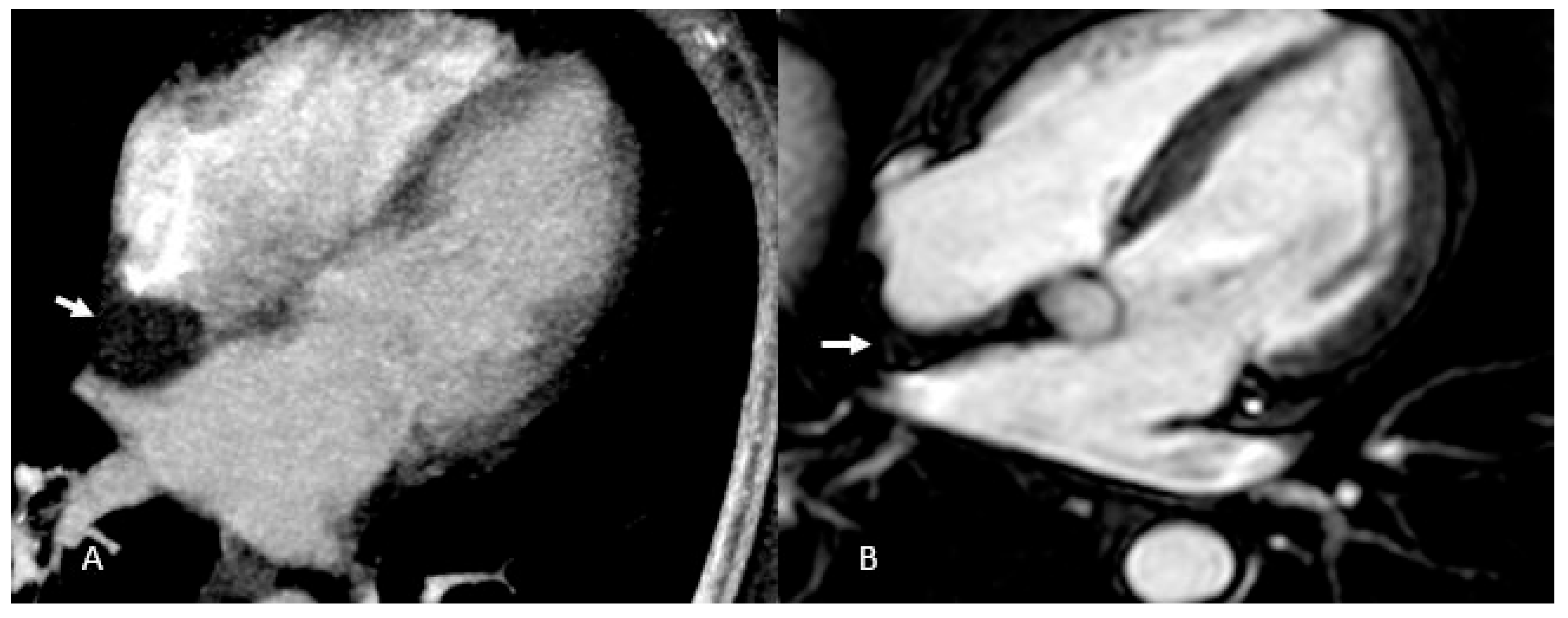

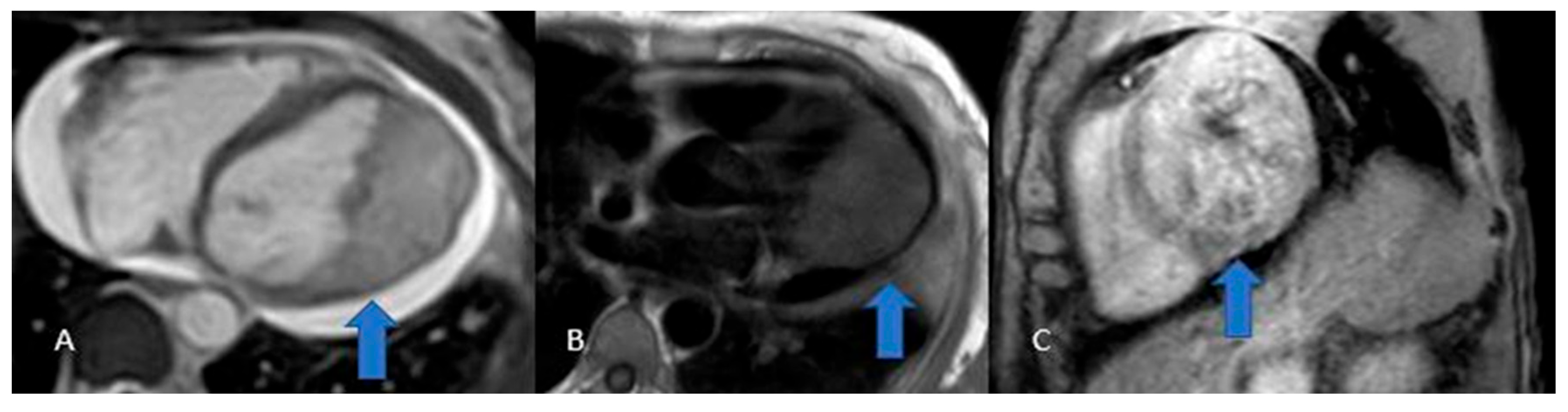

Figure 3.

Thrombus (white arrows). CINE (A), EGE (B), and LGE (C) sequences show a large thrombus (arrows) at the apex of the left ventricle. Note that it remains hypointense and does not take up contrast, which is typical of thrombi and helps in distinguishing them from other cardiac masses.

Figure 3.

Thrombus (white arrows). CINE (A), EGE (B), and LGE (C) sequences show a large thrombus (arrows) at the apex of the left ventricle. Note that it remains hypointense and does not take up contrast, which is typical of thrombi and helps in distinguishing them from other cardiac masses.

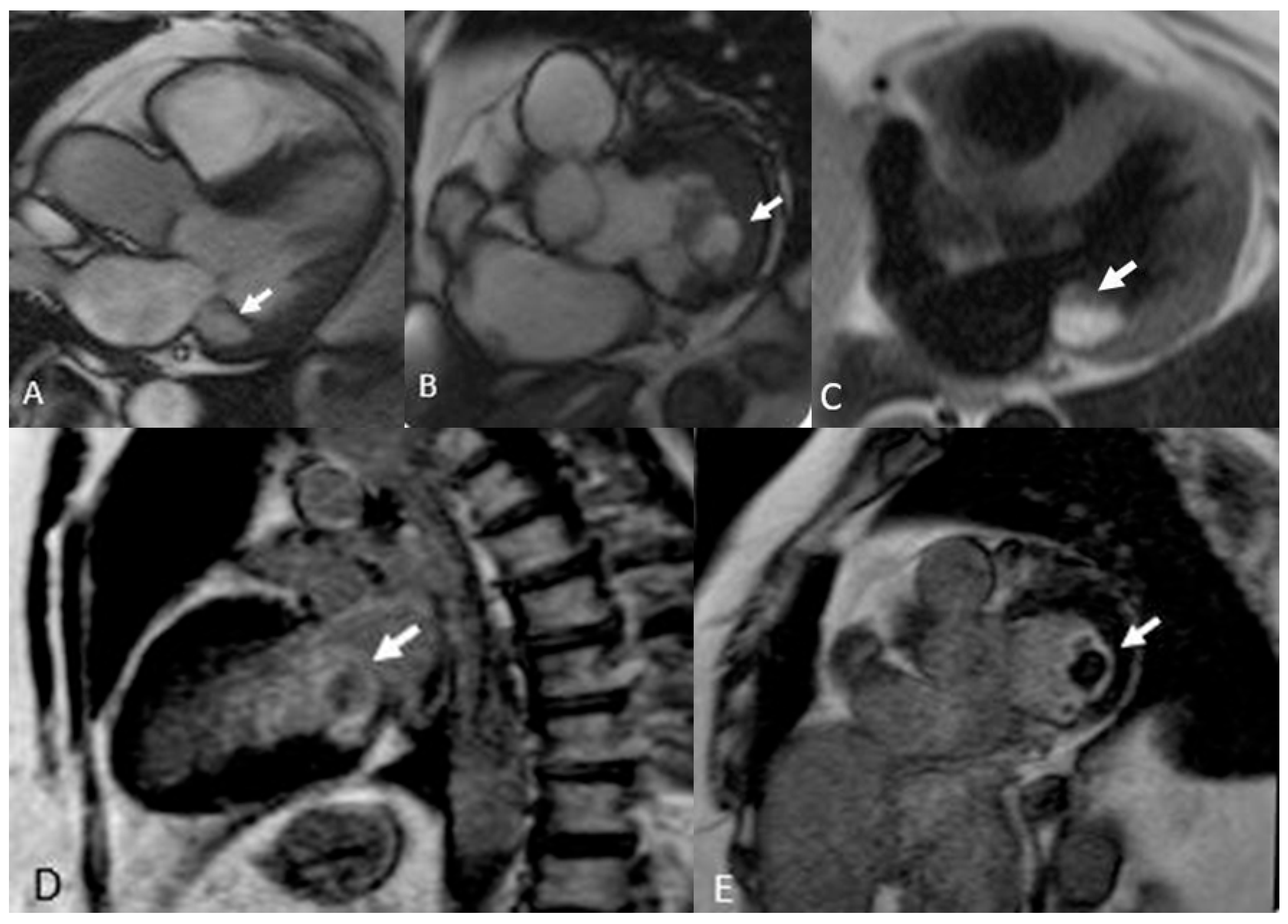

Figure 4.

Two Pericardial Cyst in different location: A (CT) and B (MRI), superior recess of the pericardium anterolaterally to pulmonary artery CT. C, D, E, (MRI) the cyst is located in the infero-lateral atrioventricular groove close to the esophagus and descending aorta. The cystic nature of the lesions (arrows) is evident, and their well-defined borders help differentiate them from solid masses, aiding in the accurate diagnosis.

Figure 4.

Two Pericardial Cyst in different location: A (CT) and B (MRI), superior recess of the pericardium anterolaterally to pulmonary artery CT. C, D, E, (MRI) the cyst is located in the infero-lateral atrioventricular groove close to the esophagus and descending aorta. The cystic nature of the lesions (arrows) is evident, and their well-defined borders help differentiate them from solid masses, aiding in the accurate diagnosis.

Figure 5.

Annular Caseous Necrosis (arrows). Note the slightly hyperintense appearance in Cine SS T2 sequences (A and B), which becomes very hyperintense in T1 Black Blood (C). In LGE sequences (D and E), the contrast enhancement of the border is typical of fibrotic lesions, with a central necrotic core, which is important for identifying necrotic tissue.

Figure 5.

Annular Caseous Necrosis (arrows). Note the slightly hyperintense appearance in Cine SS T2 sequences (A and B), which becomes very hyperintense in T1 Black Blood (C). In LGE sequences (D and E), the contrast enhancement of the border is typical of fibrotic lesions, with a central necrotic core, which is important for identifying necrotic tissue.

Figure 6.

Giant myxoma of the left atrium: Angio CT (A), Dual Energy 4-ch CT (B), and Dual Energy VLA CT (C) images. Note the presence of micro-spots of contrast within the mass in dual energy. acquisitions. These micro-spots help differentiate myxomas from thrombi, which typically do not show such contrast uptake, aiding in accurate diagnosis and treatment planning.

Figure 6.

Giant myxoma of the left atrium: Angio CT (A), Dual Energy 4-ch CT (B), and Dual Energy VLA CT (C) images. Note the presence of micro-spots of contrast within the mass in dual energy. acquisitions. These micro-spots help differentiate myxomas from thrombi, which typically do not show such contrast uptake, aiding in accurate diagnosis and treatment planning.

Figure 7.

Cardiac paraganglioma (arrow): CT exam (A and B) shows inhomogeneous enhancement. On MRI sequences, Cine HLA (C) it shows homogeneous hyperintensity, while on Short Axis FIESTA (D) it is hypointense and inhomogeneous.

Figure 7.

Cardiac paraganglioma (arrow): CT exam (A and B) shows inhomogeneous enhancement. On MRI sequences, Cine HLA (C) it shows homogeneous hyperintensity, while on Short Axis FIESTA (D) it is hypointense and inhomogeneous.

Figure 8.

Cardiac lipoma (A) and Atrial Septum Lipomatosis (B): CT exam (A) shows a round fatty mass in the interatrial septal area (arrow), suggestive for lipoma, while on MRI (B) the hourglass hypointense shape in the interatrial septum (arrow) is suggestive for lipomatosis.

Figure 8.

Cardiac lipoma (A) and Atrial Septum Lipomatosis (B): CT exam (A) shows a round fatty mass in the interatrial septal area (arrow), suggestive for lipoma, while on MRI (B) the hourglass hypointense shape in the interatrial septum (arrow) is suggestive for lipomatosis.

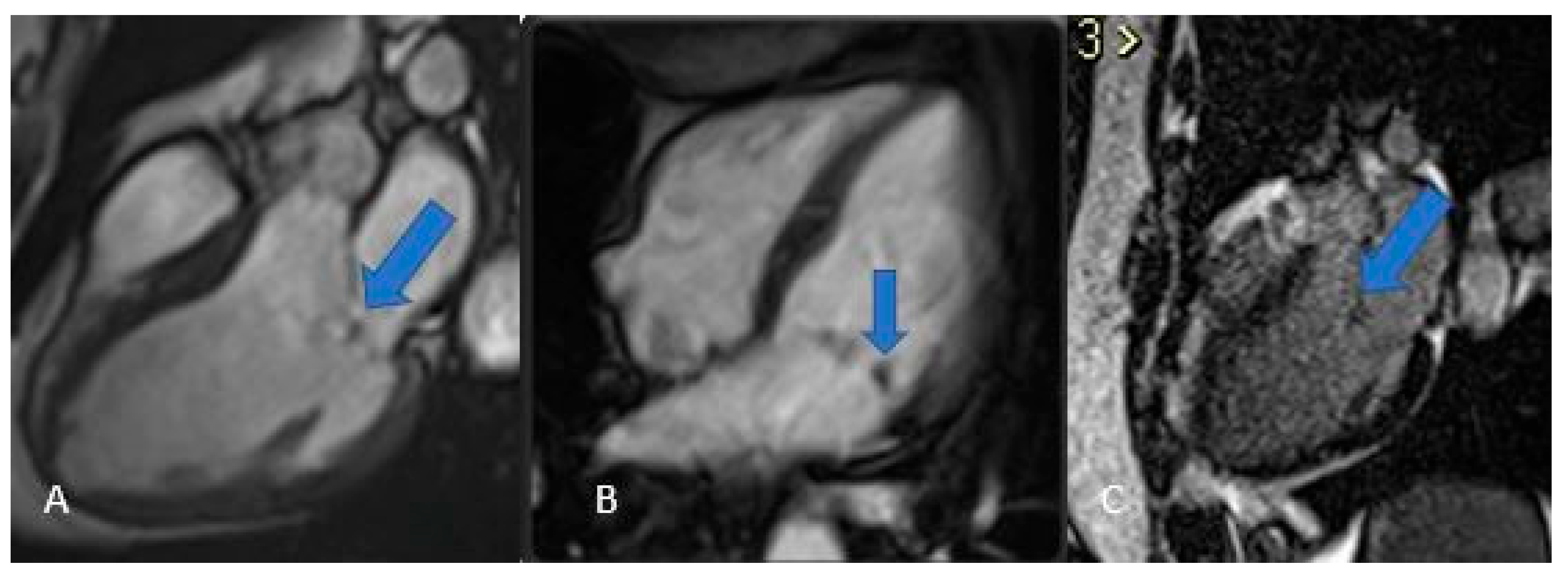

Figure 9.

Fibroelastoma: MRI images Steady State T2 in 3 and 4 chamber projection (A and B) and LGE (C) show a small polypoid formation adhered to the mitral valve.

Figure 9.

Fibroelastoma: MRI images Steady State T2 in 3 and 4 chamber projection (A and B) and LGE (C) show a small polypoid formation adhered to the mitral valve.

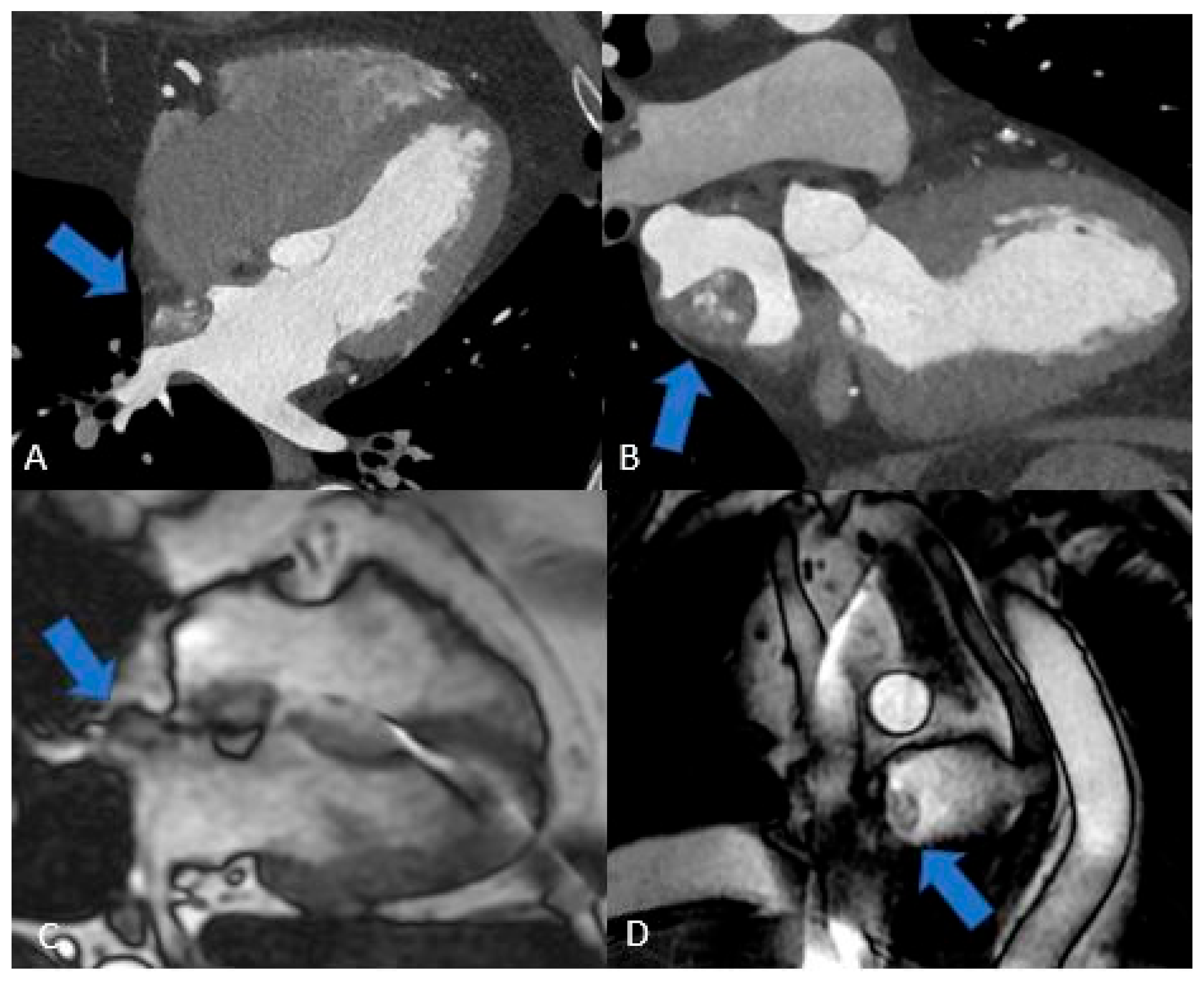

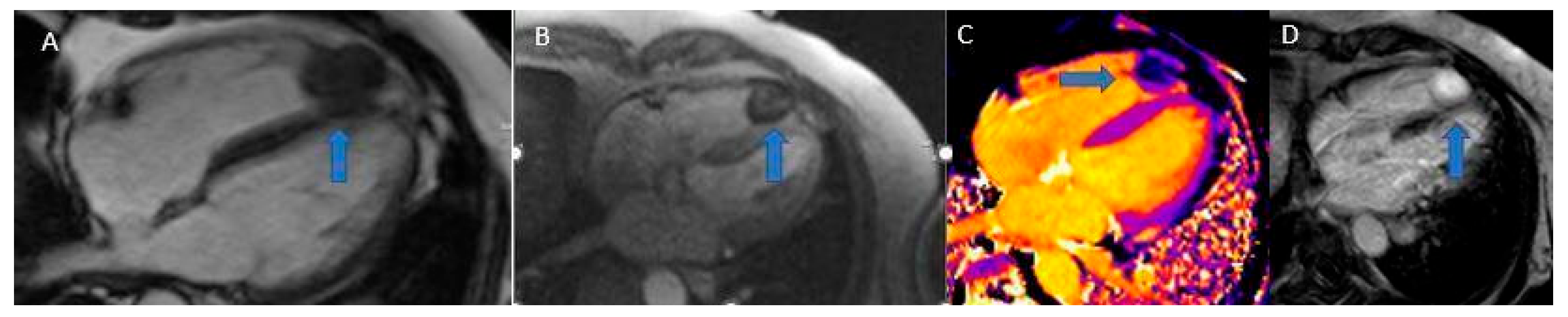

Figure 10.

Fibroma (blue arrows): Cine SSFP (A), Perfusion (B), T1 mapping (C), LGE (D). Note the low contrast uptake in perfusion with higher signal intensity in LGE, typical of a fibrotic formation.

Figure 10.

Fibroma (blue arrows): Cine SSFP (A), Perfusion (B), T1 mapping (C), LGE (D). Note the low contrast uptake in perfusion with higher signal intensity in LGE, typical of a fibrotic formation.

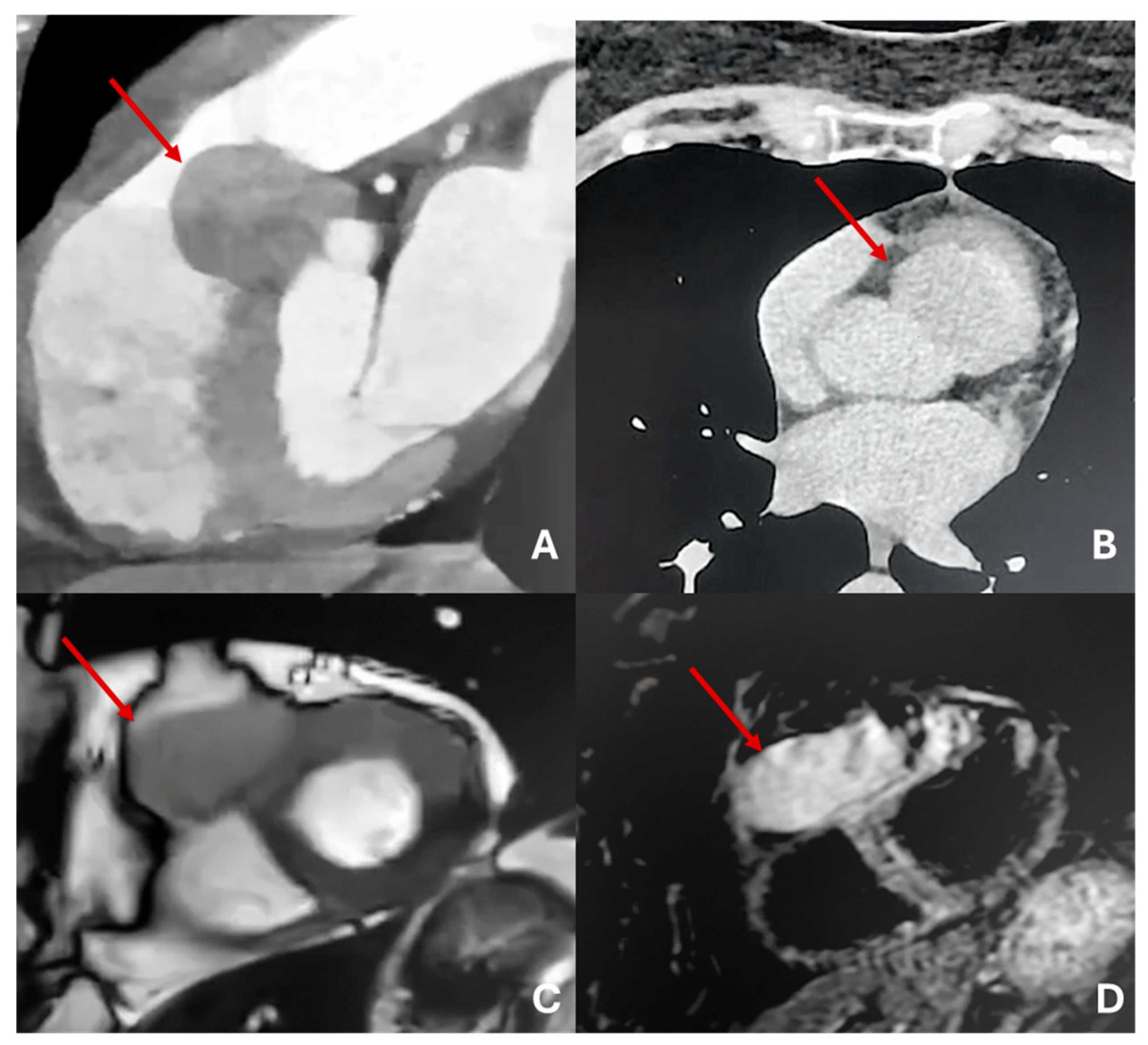

Figure 11.

Giant hemangioma originating from the anterior-basal interventricular septum, as seen on CT (A), showing progressive and intense enhancement on delayed post-contrast CT acquisition (B). The lesion demonstrates heterogeneous hypointensity on T2-steady state-weighted MRI (C), marked hyperintensity on fat-saturated T2-weighted images (D).

Figure 11.

Giant hemangioma originating from the anterior-basal interventricular septum, as seen on CT (A), showing progressive and intense enhancement on delayed post-contrast CT acquisition (B). The lesion demonstrates heterogeneous hypointensity on T2-steady state-weighted MRI (C), marked hyperintensity on fat-saturated T2-weighted images (D).

Figure 12.

Massive sarcoma of anterior-lateral wall of left ventricle with massive pericardial effusion and left pulmonary lobe metastases. Isodense in T2-weighted images (A) and T1 (B) with inhomogeneous LGE (C).

Figure 12.

Massive sarcoma of anterior-lateral wall of left ventricle with massive pericardial effusion and left pulmonary lobe metastases. Isodense in T2-weighted images (A) and T1 (B) with inhomogeneous LGE (C).

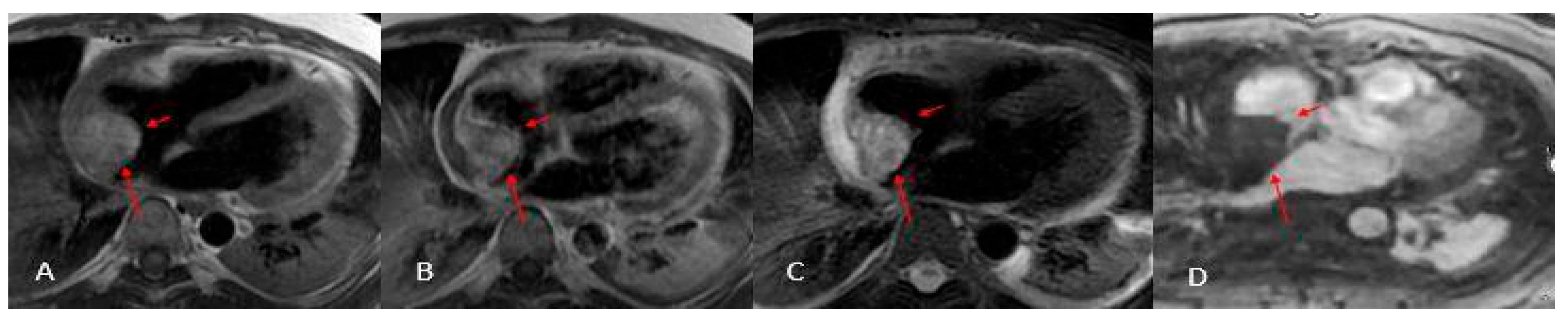

Figure 13.

Angiosarcoma (arrows). Note the heterogeneous contrast enhancement and the slightly brighter appearance in T2 (C) compared to T1 (A and B). These features are indicative of the aggressive nature of angiosarcomas and aid in differentiating them from benign lesions. In perfusion (D) it shows no uptake.

Figure 13.

Angiosarcoma (arrows). Note the heterogeneous contrast enhancement and the slightly brighter appearance in T2 (C) compared to T1 (A and B). These features are indicative of the aggressive nature of angiosarcomas and aid in differentiating them from benign lesions. In perfusion (D) it shows no uptake.

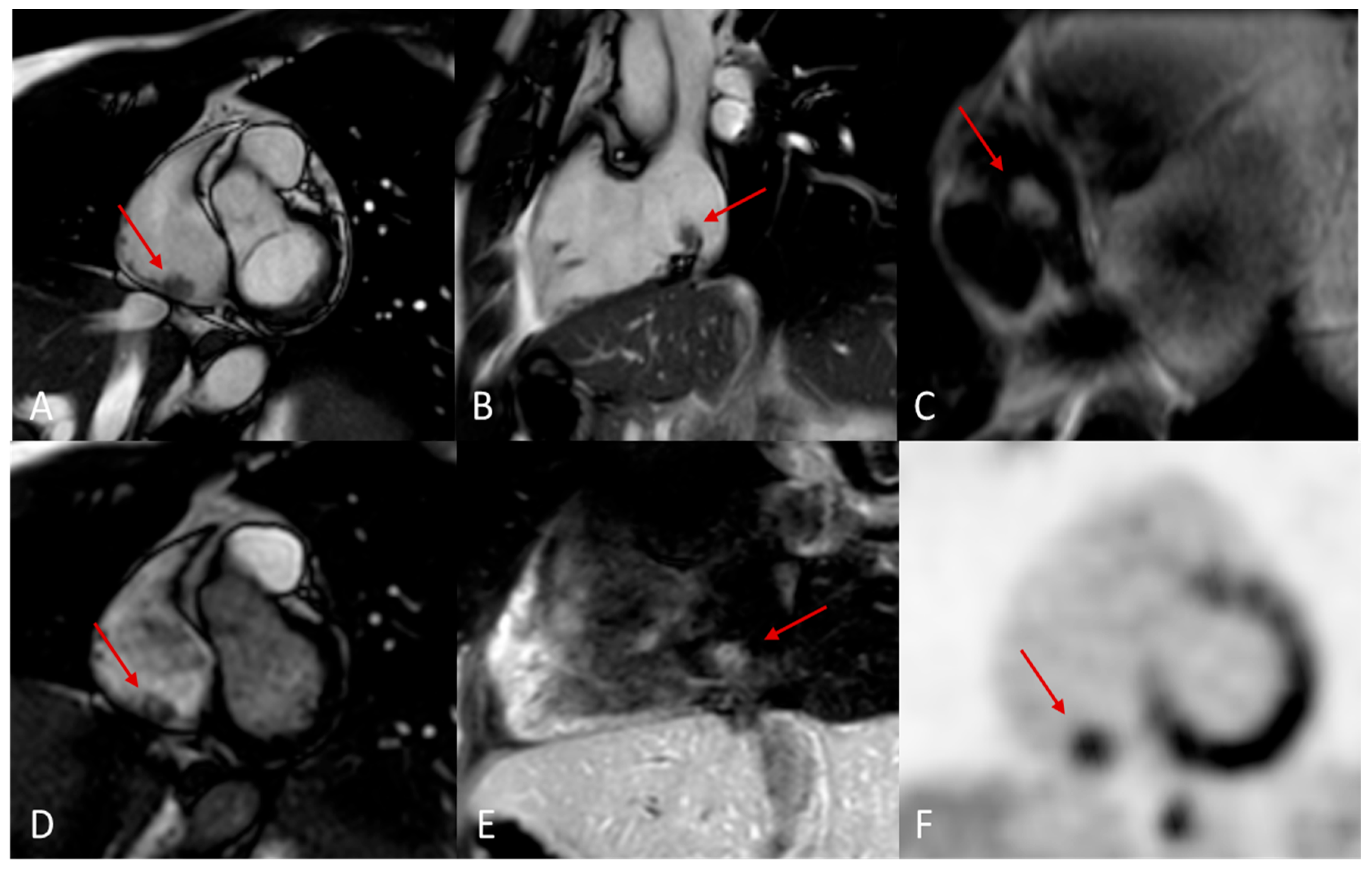

Figure 14.

Melanoma metastasis (red arrows). 14 x 10 mm nodular lesion on the inferior wall of the right atrium (A, B) characterized by hyperintensity in T1w-black blood 4ch (C), inhomogeneous enhancement in short-axis perfusion sequences (D) and weak enhancement in T1w-fat sat after 20 minutes (E). Positron emission tomography image in the short axis plane shows increased SUV (5.7) of the nodular lesion.

Figure 14.

Melanoma metastasis (red arrows). 14 x 10 mm nodular lesion on the inferior wall of the right atrium (A, B) characterized by hyperintensity in T1w-black blood 4ch (C), inhomogeneous enhancement in short-axis perfusion sequences (D) and weak enhancement in T1w-fat sat after 20 minutes (E). Positron emission tomography image in the short axis plane shows increased SUV (5.7) of the nodular lesion.

Table 2.

Most probable diagnosis of cardiac masses in pediatric and adult patients.

Table 2.

Most probable diagnosis of cardiac masses in pediatric and adult patients.

| Pediatric patients (%) |

Adult patients (%) |

| Rhabdomyoma (45%) |

Myxoma (45%) |

| Fibroma (15%) |

Lipoma (20%) |

| Teratoma (15%) |

Papillary fibroelastoma (15%) |

| Myxoma (15%) |

Others (20%) |

| Others (10%) |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).