Submitted:

09 September 2025

Posted:

10 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Rationale

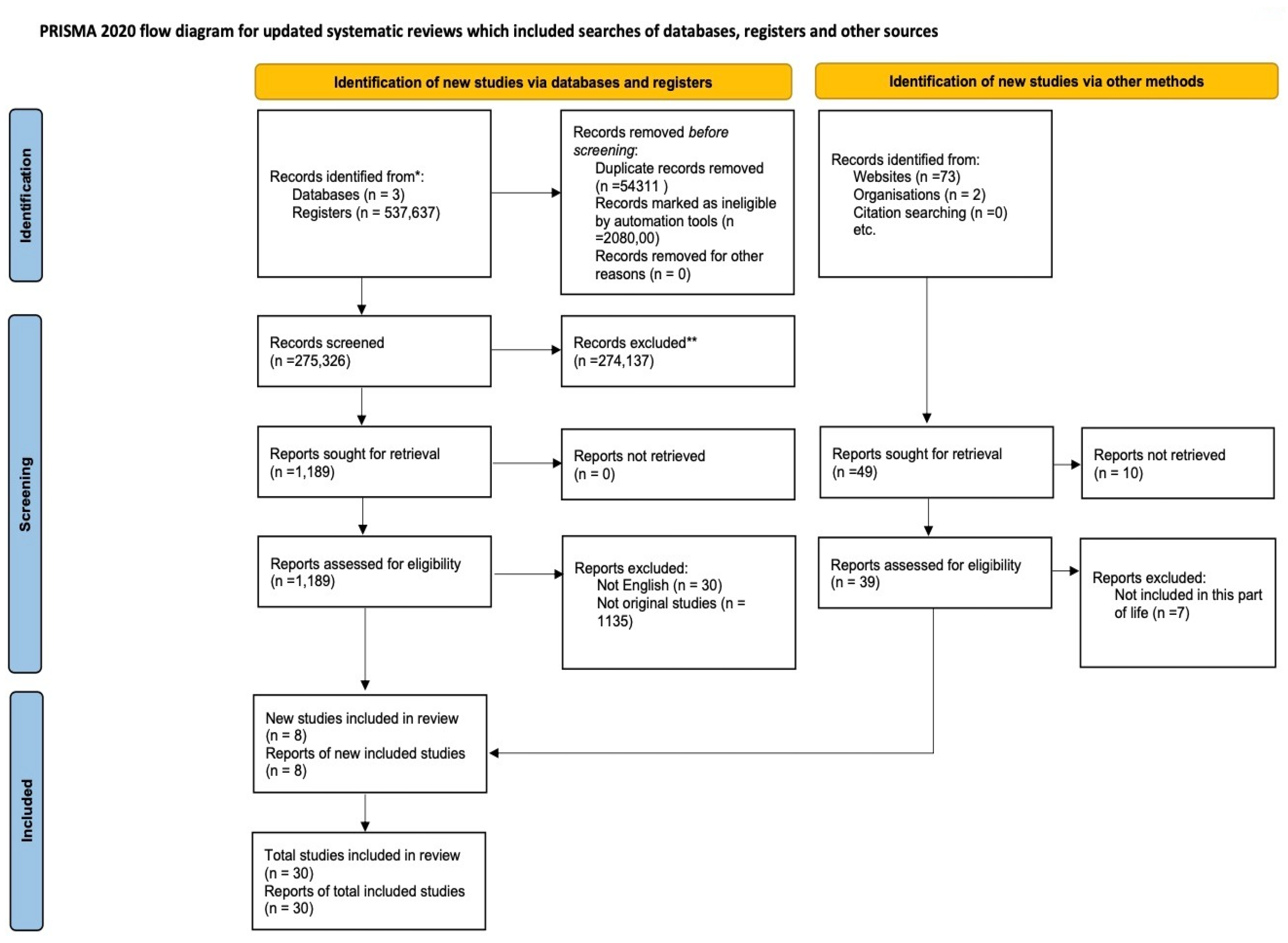

Methods and Materials

Study Design

Search Strategy

Quality Assessment

Data Analysis

Results

Overview of Included Policies

Study Characteristics

| Study ID | Policy/ articles name | Year | Policy Level | Country/Region | Policy Focused Area | Targeted Population | Policy Status | Objective | Outcomes | Equity Consideration | Global Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ghana's Free Delivery Care Policy [29] | 2003 | National | Ghana | Maternal Health Policy | Women of reproductive age who had recent live births | Implemented | Evaluate the impact of the free delivery policy on utilization and quality of delivery services, delivery outcomes, and the economic consequences for households. | The policy covered the following maternal health services: 1. Normal deliveries Assisted deliveries, including Caesarean sections Management of medical and surgical complications from deliveries, including: Repair of vesico-vaginal fistulae Repair of recto-vaginal fistulae 2. Services were provided across: Public health facilities Private health facilities Faith-based health facilities |

Universal Health Coverage | -Millennium Development Goals |

| 2 | National Women’s Health Strategy 2020–2030 | 2020 | National | Australia | Women’s health across the life course: reproductive, sexual, maternal, mental health, chronic illness, ageing, violence | All Australian women, with emphasis on those most at risk (e.g., rural, socially disadvantaged, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women) | Implemented, Active | To improve women’s health across Australia and reduce inequities | 1. Reproductive health and sexuality 2. Health of ageing women 3. Emotional and mental health 4. Violence against women 5. Occupational health and safety 6. Health needs of carers 7. Health effects of sex role stereotyping |

All women and girls in Australia, with additional focus on priority populations (e.g. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, rural/remote, low socioeconomic status, those with disability, LBTI communities, women affected by violence or justice system, veterans) | SDG3; SDG5; SDG10 |

| 3 | Israel: Reproduction and Abortion: Law and Policy [27] | 2012 | National | Israel | Funding of Reproductive care; Universal health coverage; equitable access to healthcare services | All Israeli residents | Implemented, Active | To analyse Israel’s specific policies and law on reproductive technologies and abortions and discusses their social, religious, and political context. |

1. Access to essential medical services 2. Prevention and treatment of diseases 3. Maternal and child health (Access to prenatal care, Safe delivery services) 4. Mental health 5. Chronic disease management 6. Prevention of genetic disorders 7. Reproductive autonomy and family planning |

Vulnerable Populations (such as low-income individuals, elderly, those with chronic conditions) | Not mentioned ( Indirectly associated with Universal Health access) |

| 4 | National Population Policy | 2006 | National | Tanzania | "Population and development integration Reproductive health Gender equality Nutrition Environmental conservation Education Research Advocacy and communication (IEC)" |

Entire Tanzanian population, with special focus on women, youth, and vulnerable groups | Revised and Active | To evaluate progress in implementing reproductive health policies and programs after the 1994 ICPD (International Conference on Population and Development). | "Reproductive Health Services Addressed Antenatal Care (ANC) Childbirth care Obstetric emergency care Newborn care Postpartum care Post-abortion care Family planning Prevention and management of STIs and HIV/AIDS Cancer care Childhood illnesses and immunisable diseases Nutrition Prevention and management of fistulae and pregnancy-related morbidities" |

Yes, Adherence to gender equality and equity, children’s rights and rights for other vulnerable groups | National Development Vision 2025 Millennium Development Goals |

| 5 | Reproductive Health Policy Brief | 2019 | National | Australia | Reproductive Health | Australian women | Advisory/Research-informed (not direct implementation, supports National Women’s Health Policy 2010) | Highlight findings from ALSWH (2010–2018) to inform policy on reproductive health | Identified prevalence of PCOS (10%), endometriosis (10%), infertility (18.6%); menopause age data; hysterectomy impact; links to chronic diseases | Recognizes disparities in reproductive health outcomes (e.g., obesity, mental health, fertility problems) | Linked to National Women’s Health Policy 2010; indirectly aligned with global reproductive health frameworks (ICPD, WHO women’s health agenda |

| 6 | National Reproductive Health Service Policy and Standards (3rd Edition) | 2014 | National | Ghana | Reproductive health, maternal and child health, family planning, safe motherhood | Women, children, adolescents, couples, general population | Implemented | aimed at making explicit the direction of reproductive health in the context of universal access to care | Cancer screening Family planing Infertility care unsafe abortion and post-abortion care menopause Gender based violence |

Yes – includes vulnerable groups and promotes access for all | ICPD 1994 and WHO standards on reproductive and maternal health |

| 7 | HPV Screening, Invasive Cervical Cancer and Screening Policy in Australia | 2017 | National | Australia | Cervical cancer screening | Women aged 25–69 eligible for cervical screening | Implemented | To estimate the likely impact of Australia’s new 5-yearly primary HPV screening policy (Renewal Policy) on the incidence of cervical cancer compared with the previous 2-yearly cytology screening policy. | Reduce incidence of oncogenic HPV infections (by 20% by 2030) in women and adolescent girls; decrease age-standardised mortality rate from cervical cancer (to 20% by 2030). Improve quality of life of women with terminal cancer. Reduce incidence of invasive cancer (to 20% by 2030) | Focused on age group 30–69; didn't assess stratified outcomes for First Nations or migrant women | WHO/IARC-aligned in purpose; raises concern re: SDG 3.4 (premature mortality reduction); aligns with UN’s caution on overdiagnosis |

| 8 | National Guidelines for Cervical Cancer Screening Programme | 2012 | National (with separate expectations between Community, PHC, District, Regional, and Tertiary) | South Africa | Cervical Cancer Screening | Women 30 years and older | Implemented | To achieve a screening coverage of 70% among women aged 30 to 50 years by 2010. To offer at least three free Pap smears per woman over her lifetime, |

Reduction of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer (by >60%); Screening at least 70% of target population within 10 years of programme initiation | The programme was meant to be delivered through the primary health care system, making screening available at local clinics rather than centralised urban hospitals. | Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) |

| 9 | Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control Policy(30) | 2017 | National | South Africa | Cervical Cancer Screening; Cervical Cancer Prevention | Low risk asymptomatic women (30-50 years old); Women living with HIV and women with other immunosuppressive conditions; sex workers; adolescents; migrants | Implemented | – Implement a comprehensive prevention and control programme comprising three interlinked strategies: (1) reducing oncogenic HPV infections; (2) detecting and treating cervical precancer; and (3) ensuring timely treatment and palliative care for invasive cancer. | Reduce incidence of oncogenic HPV infections (by 20% by 2030) in women and adolescent girls; decrease age-standardised mortality rate from cervical cancer (to 20% by 2030). Improve quality of life of women with terminal cancer. Reduce incidence of invasive cancer (to 20% by 2030) | Adds HPV vaccination for girls aged 9–12 via strengthened school health services, expanding access to primary prevention. | Explicitly aligns with global frameworks, notably Sustainable Development Goal 3 (universal access to sexual and reproductive health, by 2030), Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health, and targets such as universal health coverage and NCD mortality reduction |

| 10 | Sweden’s international policy on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights [22] | 2021 | International | Sweden | Safe abortions; maternity care; neonatal care; access to contraceptives; promotion of gender equality; HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections | Women; new-born babies; infants; men | Implemented | o increase access to SRHR interventions, enhance knowledge, shift social norms, and strengthen accountability, with special focus on deprived areas and vulnerable groups, including LGBTQI populations | Reduce maternal mortality rates; reduce infant mortality; prevention of transmission of HIV to new-born babies and infants; reducing spread of HIV and AIDS | Focus on inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research. Planning, conducting, reporting of analyses for sex/gender and race/ethnicity differences. | - |

| 11 | Women's Health Plan: A plan for 2021-2024 | 2024 | National | Scotland | Women's Health and Gender Equality | Women (see equity considerations) | Implemented | o reduce avoidable health inequalities experienced by women and girls across their lifespans—from puberty through later years—by focusing on areas commonly stigmatized, overlooked, or dismissed as “women’s issues,” including heart health, menopause, menstrual health, endometriosis, contraception, abortion services, and access to information | "• ensure women who need it have access to specialist menopause services for advice and support on the diagnosis and management of menopause; • improve access for women to appropriate support, speedy diagnosis and best treatment for endometriosis; • improve access to information for girls and women on menstrual health and management options; • improve access to abortion and contraception services; • ensure rapid and easily accessible postnatal contraception; • reduce inequalities in health outcomes for women’s general health, including work on cardiac disease." |

Considers gender inequities as a factor influencing SRHRs. Defines sexual rights as meaning all people irrespective of sex, age, ethnicity, disability, gender identity, or sexual orientation have a right to their own body and sexuality. | Yes. bilateral, multilateral, operational, and nomative work that Sweden in different ways carries out in international contexts. |

| 12 | The NHS Wales Women's Health Plan | 2024 | National | Wales | Women's Health and Gender Equality | Women (see equity considerations) | Implemented | To close the gender health gap in Wales by transforming the way healthcare services are designed and delivered for women and those assigned female at birth—ensuring they are listened to, their health needs are understood, and care is equitable across the lifespan | "Menstrual Health (Including: Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (HMB), Endometriosis, Fibroids, Adenomyosis, Polycystic Overy Syndrome (PCOS), Pre-menstual Syndromes (PMS), Pre-menstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD)); Endometriosis and Adenomyosis; Contraception, Post-Natal Contraception and Abortion Care; Preconception Health; Pelvic Health and Incontinence; Menopause; Violence Against Women, Domestic Abuse and Sexual Violence; Aging Well and Long-term Conditions Across the Life Course (Including: Adolescent Health and Wellbeing; Sexual Health, HIV and Blood Borne Viruses; Mental Health and Wellbeing; Alzheimer's and Dementia; Diabetes; Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; Cardiovascular Disease; Cancer Recovery; Musculoskeletal Conditions; Palliative and End of Life Care)" |

"Includes transgender men, non-binary people, and intersex people or people with variations in sex characteristics." |

e NHS Wales Women’s Health Plan is globally aligned through its commitment to the SDGs, WHO’s life-course approach, and international frameworks on gender equality and health equity |

| 13 | Women's Health Strategy for England | 2022 | National | England | Improvement of women's health | Women | Implementation | - | "Tackling disparities in access to services and experiences of services and outcomes. Women with additional risk factors or barriars to have equitable access. Menstrual health and gynaecological conditions (heavy menstrual bleeding, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), endometriosis, adenomyosis, fibrosis, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (and also urogynaecological conditions including urinary incontinence, vaginal prolapse, recurrent urinary tract infections), and gynaecological cancers. Fertility, pregnancy, pregnancy loss, and postnatal support (contraception, preconception health, fertility and infertility, pregnancy loss and stillbirth, birth trauma, support for expectant and new mothers and their partners. Personalised care. Menopause. Mental Health and Wellbeing. Cancers (uterus, ovarian, cervical, vulval, vaginal)." |

Includes trans men and non-binary people recorded female at birth. Addresses wider determinants of health (ranging across social, economic, and environmental factors). Notes that black and minority ethnic groups and disabled and lone parent women face especially worse health disparities. Intersectionality and vulnerability is addressed. | Though not explicitly named in the strategy, its focus on equitable access, improved health systems, and rights-based care supports SDG 3 (Good Health & Well-Being) and SDG 5 (Gender Equality). The fiscal framing also resonates with global economic rationale for investing in women’s health |

| 14 | Chronic conditions policy brief | 2019 | National | Australia | Chronic disease conditions of women | Women (ages ranging from 30s to 90s), specifically from Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH) | Implemented | The brief synthesizes key findings from ALSWH data (since around 2010) on chronic conditions among Australian women, aiming to inform and guide the development of national health policies— | Multimorbidity, frailty, mental health, urinary incontinence, injury from falls, obesity, diabetes, stroke, arthritis, cancer, cardiovascular disease | Addressed transgender men and non-binary people with female reproductive organs wrt cancer screening. Addresses disparities experienced by "women from under-served and seldom-heard groups". Considers groups with barriers to health, such as women experiencing: homelessness, refugees, asylum seekers, women in prisons; also: disabled women, lesbian and bisexual women, and black and Asian women. | While primarily national in scope, the brief aligns with international frameworks by recognizing chronic conditions as life-course, non-communicable diseases, advocating evidence-based, equity-focused strategies—paralleling WHO priorities and Sustainable Development Goal 3 on universal health and NCD reduction. |

| 15 | Pregnancy and maternal health policy brief | 2019 | National | Australia | Pregnancy and maternal health | Women in reproductive age | Ongoing | highlight maternal mortality and morbidity trends, underscore gaps in prenatal/postnatal care, and recommend strategic interventions—like improved access to quality services, care continuum strengthening, and workforce capacity building | Gestational diabetes, hypertension, low birth weight, maternal depression and anxiety, childhood obesity, antenatal health behavior | Emphasis typically on reducing disparities—addressing racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic inequities in maternal outcomes; promoting culturally responsive care, inclusive data collection, and community-based support. | Alignment with SDG 3, especially Target 3.1 (maternal mortality reduction) and 3.8 (universal health coverage); adherence to WHO’s human-rights based, life-course maternal health frameworks; often reflects the reproductive justice approach, which centers intersectional, rights-based access to care |

| 16 | Sexual and health policy brief [28] | 2019 | National | 2017 | Sexual health policy brief | Australian women | Ongoing | To present key research findings on sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and contraceptive use among Australian women, with the goal of informing national health policy and improving sexual health outcomes | STIs (e.g., chlamydia), thrush, contraceptive behavior, reproductive heal | highlights disparities in sexual health outcomes across ages, regions (urban vs rural), socio-economic status, and cultural or identity groups | Aligns implicitly with global health efforts such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 3) related to sexual and reproductive health and the WHO’s STI prevention frameworks |

| 17 | Women’s Health: Best Practices in Sex Education Implemented by Local Governments [20] | 2017 | National | Japan | Sexual and reproductive health education; HIV/AIDS and STD prevention; youth sex education | Students (elementary to high school), school teachers, and education stakeholders | Ongoing | to contribute to the promotion of sex education within educational institutions throughout Japan through the wide sharing of these practices |

Knowledge of STDs, contraception, reproductive health, sexual behaviors, HIV/AIDS prevention | Emphasizes clear policy, long-term implementation, evaluation, and multi-stakeholder collaboration—ensuring culturally and regionally responsive inclusion | WHO health priorities on reproductive health access, STI s |

| 18 | National action plan for endometriosis [31] | 2017 | National | Australia | Endometriosis awareness, early diagnosis, treatment, and support | Public population | Active and Ongoing | improved quality of life for women living with endometriosis and reduced burden of disease for individuals and for the nation | Chronic pelvic pain, infertility, fatigue, mental health impacts, delayed diagnosis | Not mentioned | Aligned with WHO/UNESCO recommendations on Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) |

| 19 | RANZCOG Submission to the National Women’s Health Strategy [21] | 2023 | National | Australia and New Zealand | Women’s health equity, reproductive health, maternal health, gynaecological care | Women and girls | Implemented | aims to evaluate strategies for advancing women’s health by (1) placing wāhine/women+ at the centre of care through addressing knowledge gaps, inequities, and social determinants of health; (2) ensuring integrated, accessible, and fully funded multidisciplinary services spanning community, hospital, and maternity care; (3) strengthening leadership, governance, and data systems to enhance accountability and quality; and (4) developing sustainable workforce planning and support mechanisms | Improved maternal care, abortion access, reproductive choice, chronic disease management, menopause support, culturally safe care | Not mentioned | Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC) |

| 20 | Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights under the Reproductive and Child Health Policy – Compromising Women's Dignity [17] |

2010 | National | India | maternal health, child mortality, gender equality and HIV/AIDS | women's and children's | Implemented | To bring women's and children's health to the attention of Parliamentarians, with detailed policy recommendations and actions for MPs. | women in the intervention districts reported an increase in their discussions about family planning with spouses, from 42.3% to 90%; an increase in the use of family planning methods, from 7% to 35%; more women reported being involved in decision-making at home, up from 49% to 71%; more women reported that they felt they had a right to refuse sex if they wished, from 37% to 95%; and more women reported expressing sexual needs to her spouse, from 25.4% to 67.5% | Yes, Inner Spaces Outer Faces Initiative (ISOFI): A Gender and Sexuality Project in Uttar Pradesh |

Yes, achieving the Millennium Development Goals |

| 21 | National Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Policy [17] | 2022 | National | Myanmar | Sexual and Reproductive Health |

General population | Implemented | 1. To inform decision makers, development/implementing partners, health providers, and beneficiaries about the policy and ensure that they are supported by the policy in their work and/or lives. 2. To aid in the reform of existing laws, regulations, and definitions that restrict access to essential SRHR information and services, especially among adolescents, youth, and marginalized and vulnerable groups. |

Comprehensive, high-quality health information and services will be provided to all women throughout pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. All individuals of reproductive age will have equitable access to quality and inclusive FP information, commodities, and services and will have the freedom to decide on the desired number of children and determine the healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies. The highest achievable standard of sexual and reproductive health for all adolescents will be pursued by protecting and fulfilling adolescents’ right to information, quality and inclusive services, in addition to promoting enabling environments and opportunities to develop life skills. All individuals will have their dignity and rights upheld, including their right to health. Gender-sensitive approaches will be mainstreamed throughout all levels of the health system, and individuals affected by GBV will have timely access to quality, comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services. All women, men, and young people will have access to information, prevention, early diagnosis, and care for reproductivze health morbidities. |

Assuring gender equality in health through gender-sensitive approaches to be mainstreamed throughout all levels of the health system, and individuals affected by gender-based violence will have ready access to quality, comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services | 1. Beijing Platform for Action 2. Every Woman, Every Child 3. Family Planning 2020 & 2030 4. Millennium Development Goals 5. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 6. International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) Programme of Action 7. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women 8. Convention on the Rights of the Child |

| 22 | National Reproductive Health Policy [18] | 2010 | National | Sudan | reproductive health | General population | Implemented | To assure quality reproductive and sexual health care that women survive pregnancy and childbirth and enjoy a good family life; adolescent and young children have optimal physical and sexual development; the sexually transmitted infections/HIV, reproductive tract infections, cervical cancer and other RH morbidities, including fistula, are combated; traditional practices harmful for reproductive and sexual health are prevented; and family planning services are made available | Provision of post-abortion care, antenatal care including PMTCT, skilled assistance during childbirth, essential obstetric care, postnatal care, and appropriate management of fistula cases. Provision of “continuum of care” model by addressing the three delays: delay in decision-making to seek medical care during obstetric emergencies; delay in transporting woman to an appropriate referral hospital; and delay in receiving adequate care at the hospital. Provision of neonatal care with special emphasis on improving the antitetanus coverage to both mothers and the neonates. Services regarding reproductive choices and birth spacing methods provided free of charge. General practitioners and specialist physicians shall provide the whole range of family planning services. At primary health care level, health visitors and medical assistants shall provide family planning information and services for child spacing and welfare of women. In remote villages and nomadic settings, village midwives and community health workers shall act as change agent and in addition to providing hormonal contraceptives and condoms, refer clients to health facilities. The induction of abortion, except under medical advice, is pronounced illegal by this policy. Emphasizes promoting adolescent reproductive and sexual health, including combating sexually transmitted infections, and reproductive tract infections. Measures shall be taken for ensuring early diagnosis of cervical cancer and that other RH morbidities including complications of unsafe abortion and vesico-vaginal fistula are combated. Pre-marital care for the health and life of the family and future generations; this shall be incorporated within the provided services. Premarital counseling, to include counseling on nutrition, HIV testing, genetically transmitted diseases, harmful behaviors and misconceptions regarding sexual and reproductive health/ Traditional practices that are harmful for reproductive and sexual health particularly female genital mutilation, early marriage, and GBVs are prevented. Procedures like cloning and semen donation are prohibited and not allowed under law; therefore are not supported by this policy. |

Yes, unity and empowerment in accessing and availing reproductive health care is seen in the policy in the context of social determinants of health. |

Yes , o achieving MDG 5, thus contributing to the Millennium Declaration for Achieving MDGs, particularly 3, 4, 5 and 6 |

| 23 | NatioNal Medical StaNdard For reproductive HealtH [20] | 2020 | National | Nepal | reproductive HealtH | General population | Implemented | to provide policymakers, health officers, hospital directors or health facility in-charges, clinical supervisors and service providers of all level of governments in federal context with accessible, clinically-oriented information to guide the provision of reproductive health services in Nepal |

Information: right to accurate, appropriate, understandable, and unambiguous information related to reproductive health and sexuality, and to overall health. Information and materials for clients need to be available in all parts of the healthcare facility. Access to services: right to services that are affordable, are available at convenient times and places, are fully accessible with no physical barriers, and have no inappropriate eligibility requirements or social barriers, including discrimination based on sex, gender, age, marital status, fertility, nationality or ethnicity, social class, religion, or sexual orientation. Informed choice: right to make a voluntary, well-considered decision that is based on options, comprehensible information, and understanding. The informed choice process is a continuum that begins in the community, where people get information even before they come to a facility for services. It is the service provider’s responsibility either to confirm that a client has made an informed choice or to help the client reach an informed choice. Safe services: Clients have a right to safe services, which require skilled providers, attention to infection prevention, and appropriate and effective medical practices. Safe services also mean proper use of service-delivery guidelines, quality assurance mechanisms within the facility, counselling and instructions for clients, and recognition and management of complications related to medical and surgical procedures. Privacy and confidentiality: Clients have a right to privacy and confidentiality during the delivery of services. This includes privacy and confidentiality during counselling, physical examinations, and clinical procedures, as well as in the staff’s handling of clients’ medical records and other personal information. Dignity, comfort, and expression of opinion: right to be treated with respect and consideration. Service providers need to ensure that clients are as comfortable as possible during the procedures. Clients should be encouraged to express their views freely, even when their views differ from those of service providers. Continuity of care: right to continuity of services, supplies, referrals, and follow-up necessary to maintaining their health. |

Yes, attention to equity for ELEMENTS Of Care | International Reference Texts/Materials e.g. FP Global Handbook 2018, Medical Eligibility Criteria, 2015 (WHO) Scientific Research/Evidence |

| 24 | Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn Child and Adolescent + Health of Ageing(RMNCAH+A) Strategy | 2025 | National | Bhutan | RMNCAH+ Healthy ageing strategy | women, children, and adolescents | implemented | provide strategic guidance to the national and district level managers to implement the life course approach and continuum of evidence-based interventions along the life course in achieving the human capital to its fullest potential | There are four strategic outcomes that are inter-related and mutually reinforcing and contribute to 13th FYP health outcome of “improved health and wellbeing for all Bhutanese”. The strategic outcomes are linked to several outputs identified by the MOH in the health sector section of the 13th FYP | Yes, Enhance the capability of at national and subnational levels to carry out stewardship functions with special focus on PHC. PHC oriented health systems are critical for better health outcomes, equity and efficiency | Yes. Aligned with SGD and WHO and UNFDP indicators |

| 25 | National Health Policy [19] | 2011 | National | Botswana | Comprehensive national health system policy | All people living in Botswana | Implemented | Strengthen health system to ensure universal access, address disease burden | Expanded facilities; improved ART access; progress on malaria reduction; persistent inequities in maternal/child mortality & HRH shortages | Explicit focus on reducing inequities across social groups, regions, gender, disadvantaged; incorporates social determinants of health | Anchored in WHO health system “six building blocks,” MDGs, Ouagadougou Declaration, Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness |

| 26 | National Sexual and Reproductive Health Policy | 2022 | National | Mauritius | Sexual and Reproductive Health | General population | Implemented | to provide guidance to the Ministry of Health and Wellness and all stakeholders on the coordination and implementation of relevant programmes in response to the country’s Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights and needs. | have their bodily integrity, privacy, and personal autonomy respected; • freely define their own sexuality, including sexual orientation and gender identity and expression; • decide whether and when to be sexually active; • choose their sexual partners; • have safe and pleasurable sexual experiences; • decide whether, when, and whom to marry; • decide whether, when, and by what means to have a child or children, and how many children to have; and • have access over their lifetimes to the information, resources, services, and support necessary to achieve all the above, free from discrimination, coercion, exploitation, and violence. |

Mainstream SRHR issues of equity and empowerment | UNDP’s Sustainable Developments Goals WHO’s Reproductive Health strategy 2004 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) 1994 4th World Conference on Women (Beijing) 1995 |

| 27 | National Policy on Sexual and Reproductive Health [14] | 2013 | National | The kingdom of Swaziland | Sexual and Reproductive Health | Women, men, adolescents, youth, ageing population | Implemented | Provide coordinated, integrated SRH services; improve maternal and child health; reduce HIV/STI burden; promote gender equity and rights | Increased ANC coverage (94%); facility deliveries (74%); integration of HIV/SRH; policy guidelines for FP, PMTCT, cervical cancer | Emphasis on gender equality, community participation, rights-based approach | Explicitly aligned with ICPD PoA, FWCW, MDGs, AU SRHR framework, Maputo Plan of Action, SADC protocols |

| 28 | National Reproductive Maternal,, Newborn, Child And Adolescent Health (RMNCAH) Policy [15] | 2018 | National | Rwanda | Reproductive maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health | women, new born, children and adolescents | Implemented | The continuum of care throughout the life cycle and health system which has been proved to have a high impact on reducing maternal, neonatal and child mortality and morbidity. | Strengthen inter-sectoral collaboration and coordination and harmonize existing policies to address the social determinants of poor RMNCAH outcomes, and conduct research to identify major obstacles and the most effective coordination mechanisms. Implement and monitor a harmonized, integrated and sustainable package of quality client and youth-friendly essential RMNCAH promotion, prevention and treatment interventions, commodities and innovative technologies at hospital, health centre and community levels and conduct research on the cost-effectiveness of interventions. Build capacity of training institutions, managers and health care providers in integrated RMNCAH care so that health staff at all levels from community upwards are able to deliver quality, integrated, client and youth-friendly RMNCAH services. Strengthen health systems and research towards universal coverage of RMNCAH services paying attention to the deployment and retention of health staff, financial and geographical access to services by under-served and vulnerable groups/ beneficiaries and use the HMIS to monitor equity. Intensify health promotion efforts to increase community knowledge and skills on RMNCAH interventions and promote health seeking behaviour. Strengthen governance systems and accountability (joint planning, budget allocation, implementation, monitoring and evaluation) of integrated RMNCAH interventions at central, decentralised and community levels, including with public-private partnerships and through Imihigo and performance- based contracts. |

Yes, All women, new born babies, children and adores- cents - without distinction of age, gender, marital status, ability (mental or physical), race, religion, sexuality, political beliefs, geographical situation, or socio-economic status - have a right to equal and universal access to RMNCAH interventions | Millennium Develop- mint Goals |

| 29 | Population and Reproductive Health Policy | 1998 | National | Sri Lanka | "Population stabilization Reproductive health Family planning Gender equality Youth/adolescent health Elderly care Migration and urbanization Public awareness Data systems" |

Women of reproductive age, the elderly, urban migrants, general population, national policymakers and institutions. | Implemented | to review existing data and discover emerging issues of population in Sri Lanka in order to propose appropriate policy interventions which will facilitate the promotion of overall development in the country |

Safe motherhood Maternal morbidity and mortality Subfertility and infertility Anemia in reproductive-aged women and pregnant mothers Unwanted pregnancies Reproductive tract infections (RTIs) Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV/AIDS Reproductive cancers (e.g., cervical, ovarian, breast, prostate) |

Yes,Emphasis on gender equity, underserved areas, rural/urban balance | Not mentioned, Aligns with ICPD 1994, MDG 5, SDGs (esp. SDG 3, 5) |

| 30 | Reproductive Health, Gender & Rights in Mongolia [16] | 2000 | National | Mangilao | Reproductive Health, Gender & Rights | General population | Implemented | Aims at creating a favorable environment for positive support and actions in the field of reproductive health, through advocacy with law and policy-makers and programme managers at all levels | This report provides a critical analysis of the legal environment related to reproductive health and gender, and as such provides the necessary background to identify gaps which need to be addressed in the current laws. The workshop mentioned above provides us with a series of recommendations for such changes to be advocated for and these are presented in Appendix 1. It is hoped that this report will be a useful reference tool for Members of Parliament, for policy-makers, decision-makers and programme-managers, for NGOs, for international donors for a better understanding of the legal environment in Mongolia for reproductive health and for gender. | It was relatively straightforward for government to implement strong legal guarantees for equality in employment under a centrally planned system. | Yes |

| Study ID | Policy/ article name | Year | Country | Authority (5) | Accuracy (5) | Coverage (5) | Objectivity (5) | Date (5) | Significance (5) | Total score (30) | Total Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ghana's Free Delivery Care Policy [29] | 2003 | Ghana | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 22 | Medium |

| 2 | National Women’s Health Strategy 2020–2030 | 2020 | Australia | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 26 | High |

| 3 | Israel: Reproduction and Abortion: Law and Policy [27] | 2012 | Israel | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 25 | High |

| 4 | National Population Policy | 2006 | Tanzania | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 25 | High |

| 5 | Reproductive Health Policy Brief | 2019 | Australia | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 22 | Medium |

| 6 | National Reproductive Health Service Policy and Standards (3rd Edition) | 2014 | Ghana | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 25 | High |

| 7 | HPV Screening, Invasive Cervical Cancer and Screening Policy in Australia | 2017 | Australia | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 24 | Medium |

| 8 | National Guidelines for Cervical Cancer Screening Programme | 2012 | South Africa | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 24 | Medium |

| 9 | Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control Policy [30] | 2017 | South Africa | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 25 | High |

| 10 | Sweden’s international policy on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights [22] | 2021 | Sweden | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 27 | High |

| 11 | Women's Health Plan: A plan for 2021-2024 | 2024 | Scotland | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 27 | High |

| 12 | The NHS Wales Women's Health Plan | 2024 | Wales | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 27 | High |

| 13 | Women's Health Strategy for England | 2022 | England | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 27 | High |

| 14 | Chronic conditions policy brief | 2019 | Australia | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 24 | Medium |

| 15 | Pregnancy and maternal health policy brief | 2019 | Australia | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 24 | Medium |

| 16 | Sexual and health policy brief [28] | 2019 | Australia | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 22 | Medium |

| 17 | Women’s Health: Best Practices in Sex Education Implemented by Local Governments [20] | 2017 | Japan | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 21 | Medium |

| 18 | National action plan for endometriosis [13] | 2017 | Australia | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 23 | Medium |

| 19 | RANZCOG Submission to the National Women’s Health Strategy [21] | 2023 | Australia & New Zeland | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 26 | High |

| 20 | Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights under the Reproductive and Child Health Policy – Compromising Women's Dignity [17] |

2010 | India | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 23 | Medium |

| 21 | National Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Policy [17] | 2022 | Myanmar | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 26 | High |

| 22 | National Reproductive Health Policy [18] | 2010 | Sudan | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 23 | Medium |

| 23 | NatioNal Medical StaNdard For reproductive HealtH [20] | 2020 | Nepal | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 25 | High |

| 24 | Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent + Health of Ageing (RMNCAH+A) Strategy [23] | 2025 | Bhutan | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 26 | High |

| 25 | National Health Policy [19] | 2011 | Botswana | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 25 | High |

| 26 | National Sexual and Reproductive Health Policy | 2022 | Mauritius | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 26 | High |

| 27 | National Policy on Sexual and Reproductive Health [14] | 2013 | The kingdom of Swaziland | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 25 | High |

| 28 | National Reproductive Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCAH) Policy [15] | 2018 | Rwanda | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 22 | Medium |

| 29 | Population and Reproductive Health Policy | 1998 | Sri Lanka | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 22 | Medium |

| 30 | Reproductive Health, Gender & Rights in Mongolia [16] | 2000 | Mongolia | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 19 | Medium–Low |

| Theme | Contextual Evidence | Findings/ Patterns | Implications for IVF & Geriatric Mothers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legal & Policy Frameworks | Policies such as Israel’s Reproduction and Abortion Law (2012), Sweden’s Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights policy (2006), and Australia’s National Women’s Health Strategy (2020–2030) provide frameworks for reproductive rights, access to assisted reproductive technologies, and menopause care(22). | Rights-based approaches have increasingly replaced purely maternal/child-focused policies, yet implementation is inconsistent. Many LMIC policies reference reproductive health broadly but lack explicit provisions for IVF or age-related fertility interventions. | IVF access for older women is often constrained by age limits, religious or cultural norms, and coverage gaps. Legal clarity and supportive regulation are needed to ensure older women have equitable access to reproductive technologies and fertility counseling. |

| Financing & Coverage | Ghana’s Free Delivery Care Policy (2007) and Nigeria’s Saving One Million Lives illustrate targeted financing models; Australia’s strategy includes dedicated funding for chronic conditions and reproductive health [29]. | Fee removal, insurance coverage, and government subsidies can improve service uptake, but LMICs face sustainability challenges and hidden costs that reduce access for older or IVF-seeking women. | Older women seeking IVF or geriatric maternal care may face high out-of-pocket costs in LMICs, while HICs provide better coverage through insurance and public health financing. Dedicated funding streams for assisted reproductive technologies are essential. |

| Service Delivery & Workforce | Decentralization in Argentina (abortion care), Scotland and Wales (menopause services), and Sri Lanka’s integrated MCH services demonstrate workforce adaptation to population needs. | Nurse- and midwife-led services expand access; integration of reproductive, chronic, and menopause care improves continuity. Gaps persist in provider training, age-specific care, and adolescent-sensitive approaches. | Geriatric mothers and older IVF patients require specialized clinical expertise, including high-risk pregnancy management and menopausal support. Workforce training in these areas ensures safer outcomes and patient-centered care. |

| Equity & Structural Determinants | Australia’s equity focus on Indigenous, rural, and LBTI women; South Africa’s cervical cancer screening policy for high-risk groups; Ghana’s reproductive health policies highlighting rural and poor populations. | Policies increasingly recognize social, economic, and cultural barriers, but targeted interventions for marginalized older women or IVF patients are limited. | Older women and IVF patients often face compounded inequities, including rural residence, low income, and cultural barriers. Equity-oriented policies should prioritize access, counseling, and support services for these groups. |

| Perimenopause, Menopause, Post-Menopause | Australian Reproductive Health Policy, NHS Wales Women’s Health Plan, Scotland’s Women’s Health Plan, and Ghana’s reproductive health policies address menopause care, HRT, and chronic condition management. | Recognition of menopausal symptoms and chronic disease management is increasing. Integration into primary care remains limited in many LMICs; guidance is inconsistent regarding fertility, late pregnancies, and hormonal support. | Older women pursuing IVF or experiencing late pregnancies need tailored menopause management, HRT counseling, and screening for chronic conditions. Policies must integrate reproductive planning and geriatric maternal care for optimal health outcomes. |

Combined Thematic and Contextual Analysis

Peri-Menopause, Menopause, and Post-Menopause Health

Financing and Health System Capacity

Service Delivery Models and Health Workforce

Policy Drivers and Global Influences

Equity and Structural Determinants

Narrative Synthesis

Discussion

Comparison with Prior Policy Trajectories

Implications for Perimenopause, Menopause, and Post-Menopause

Clinical Implications

Strengths and Limitations

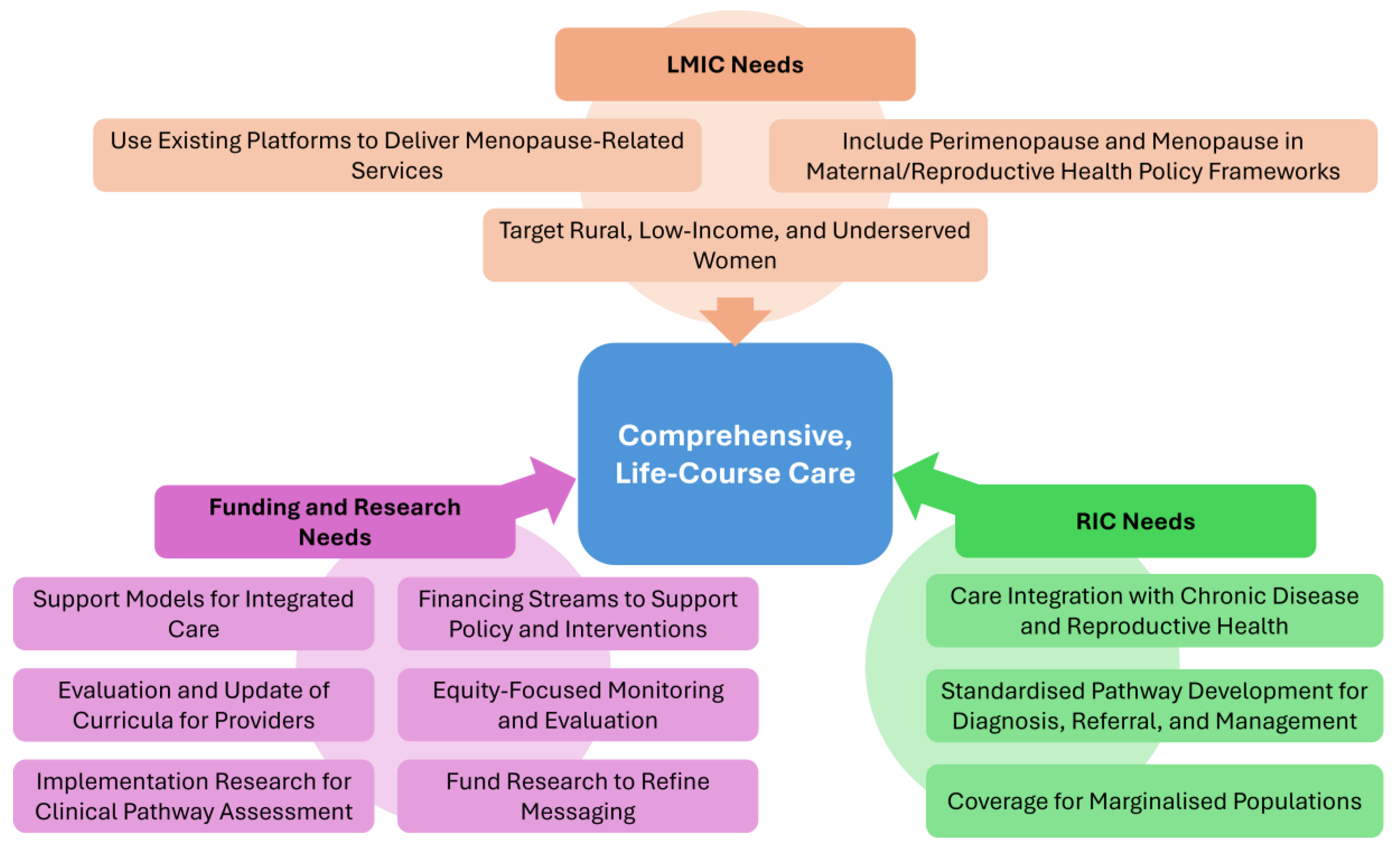

Policy Recommendations

| Domain | High-Income Countries (HICs) | Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) | Funding & Research Needs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Integration | Embed menopause in national women’s health strategies with enforceable entitlements and service standards. | Expand beyond maternal/reproductive health to explicitly include perimenopause and menopause in policy frameworks. | Multi-donor and domestic financing streams to support real-time policy development and pilot interventions. |

| Clinical Pathways | Develop clear, standardized pathways for diagnosis, referral, and management, linked to workforce training. | Create simplified, scalable clinical guidelines adaptable for rural and resource-limited settings. | Fund implementation research to assess clinical pathway effectiveness. |

| Provider Training | Incorporate menopause-specific education into medical, nursing, and allied health curricula. | Strengthen training for primary care and community health workers to identify and manage midlife health needs. | Continuous evaluation and updating of curricula based on emerging evidence. |

| Service Delivery | Integrate menopause care with chronic disease and reproductive health services for seamless care. | Use existing maternal and reproductive health platforms to deliver menopause-related services where new services are not yet feasible. | Support pilot models for integrated care, with funding for scale-up. |

| Equity and Access | Ensure coverage for marginalized populations, including migrants, LGBTQ+ individuals, and low-income groups. | Target rural, low-income, and underserved women, reducing financial and geographic barriers to care. | Establish equity-focused monitoring and evaluation frameworks with disaggregated data. |

| Public Awareness | Implement campaigns to normalize menopause and reduce stigma, engaging workplaces and communities. | Address cultural barriers and misinformation through locally adapted education and outreach. | Fund qualitative and participatory research to refine messaging. |

| Monitoring & Evaluation | Establish robust systems with age- and menopause-stage disaggregated data for quality and outcome tracking. | Build basic data collection capacity within health information systems to track service uptake and outcomes. | Support real-time digital tools for data collection and policy feedback loops. |

| Research & Evidence Base | Support longitudinal studies on menopause trends, interventions, and workforce impacts [28]. | Prioritize baseline epidemiological studies to map prevalence, symptom burden, and access gaps. | Allocate funding for cross-country comparative studies and policy evaluations. |

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest

References

- Minkin MJ. Menopause: Hormones, Lifestyle, and Optimizing Aging. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kimberly Peacock; Karen Carlson; Kari M. Ketvertis; Chaddie Doerr. Menopause (Nursing): StatPearls [Internet]. 2023.

- Mohammad Haddadi F-sT, Isa Akbarzadeh, Tahereh Eftekhar, Sedigheh Hantoushzadeh, Fatemeh Hedayati, Sepideh Ahmadi & Ahmad Delbari The sleep quality in women with surgical menopause compared to natural menopause based on Ardakan Cohort Study on Aging (ACSA). 2025. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Menopause 2024 [Available from: Menopause [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/menopause.

- Remme M VA, Fernando G, Bloom DE. Investing in the health of girls and women: a best buy for sustainable development. BMJ 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kathryn Godburn Schubert CEB, Katy Kozhimmanil, Susan F Wood,. To Address Women's Health Inequity, It Must First Be Measured. 2022. [CrossRef]

- NHS. Hormone Replacement Thaerapy 2023 [Available from: [cited 2025 Aug 27]. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/hormone-replacement-therapy-hrt/.

- YelaGabriela Pravatta RezendeRenan Massao NakamuraCristina Laguna Benetti-PintoIrfan MuhammadRabia KareemJeremy van VlymenAshish ShettyGanesh DangalSuman PantNirmala RathnayakeLanka DassanayakeJian Qing ShiOm KurmiSaval KhanalSohier ElneilMARIE Consortium GDGBPTPMBCHAPST-KM-AFKUEEMM-HTY-KSA. A Perspective on Economic Barriers and Disparities to Access Hormone Replacement Therapy in Low and Middle-Income Countries (MARIE-WP2d) 2025 [.

- Rakibul M Islam JR, Sadia Katha, Md Anwer Hossain, Siraj Us Salekin, Anika Tasneem Chowdhury, Ashraful Kabir, Lorena Romero, Susan R Davis,. Menopause in low and middle-income countries: a scoping review of knowledge, symptoms and management. Climacteric. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Manisha Gore & Julia Morgan. Indigenous women’s experiences, symptomology and understandings of menopause: a scoping review. BMC Women's Health. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Walker-Bone K DS. Menopause, women and the workplace. Climacteric. 2025. [CrossRef]

- David Moher AL, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G Altman; PRISMA Group,. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009. [CrossRef]

- Australian goverment-department of health. National action plan for endometriosis. 2018.

- Health TKOS-Mo. National policy on reproductive and sexual health. 2013.

- Republic of Rwanda-Ministry of Health. National reproductive maternal, newborn, child and adolescent (RMNCAH) health policy. 2018.

- Arthi Patel L, Australian Volunteers International, D. Amarsanaa, Centre for Human Rights and Development,. Reproductive Health, Gender & Rights in Mongolia. 2000.

- Ministry of health-Myanmar. National Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Policy. 2022.

- Sudan Government of National Unity - Federal Ministry of Health. National Reproductive Health Policy. 2010.

- Ministry of Health G-B. National Health Policy-“Towards a Healthier Botswana”. 2011.

- Government of Nepal- Ministry of Health and Population. National Medical Standard For Reproductive Health. 2020.

- Submission of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Aotearoa New Zealand- Women’s Health Strategy. 2023.

- Public health agency of Sweden. National Strategy for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR). 2022.

- Ministry of Health - Royal Government of Bhutan. REPRODUCTIVE, MATERNAL, NEWBORN, CHILD AND ADOLESCENT + HEALTH OF AGEING (RMNCAH+A) STRATEGY. 2025-2029.

- Lisa Ann Richey. Women's Reproductive Health & Population Policy: Tanzania. Review of African Political Econom. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Government of New Zealand. Women in New Zealand - United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. 2016.

- UNFPA. ANNUAL REPORT 2017. 2017.

- The Law Library of Congress. Israel: Reproduction and Abortion: Law and Policy. 2012.

- Hsiu-Wen Chan and Gita Mishra. Sexual Health Policy Brief -Australian Longitudenal study on Women health. Women’s health. 2019.

- Ofori-Adjei D. Ghana’s Free Delivery Care Policy. GHANA MEDICAL JOURNAL. 2007.

- Department of health- South Africa. National guideline for cervical cancer screening programme. 2000.

- Gayathri Delanerolle PP, Sohier Elneil,Vikram Talaulikar, George U Eleje, Rabia Kareem, Ashish Shetty, Lucky Saraswath, *Om Kurmi,Cristina Laguna Benetti-Pinto, Ifran Muhammad, Nirmala Rathnayake, Teck-Hock Toh, Ieera Madan Aggarwal, Jian Qing Shi, Julie Taylor,, Kathleen Riach KP, Ian Litchfield, Helen Felicity Kemp, Paula Briggs, and the MARIE collaborative. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. The Lancet Global helath. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chukwuka Elendu TWO, George S. Blewusi, Oluwatobi O.M., Meduoye, Emmanuel C. Ogelle, Arube R. Egbo, Vivian C. Nwankwo,Kingsley C. Amaefule,, SLE, Abdirahman A. Mohamed, Oyinkansola S. Ogedengbe, Ovonomor P. Aggreh, Dorin I. Obi, Victor I. Orji, Sikiru O. Bakare, Fahidah D. Adediran, Fiyinfoluwa Adetoye, Babatunde A. Akande, Omolara C. Ogunsola, Aishat M. Olanlege,. FDAapprovesVeozah(Fezolinetant)for menopausalsymptoms:anewnonhormonaloption. Annals of medicine and surgery. 2025.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).