Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

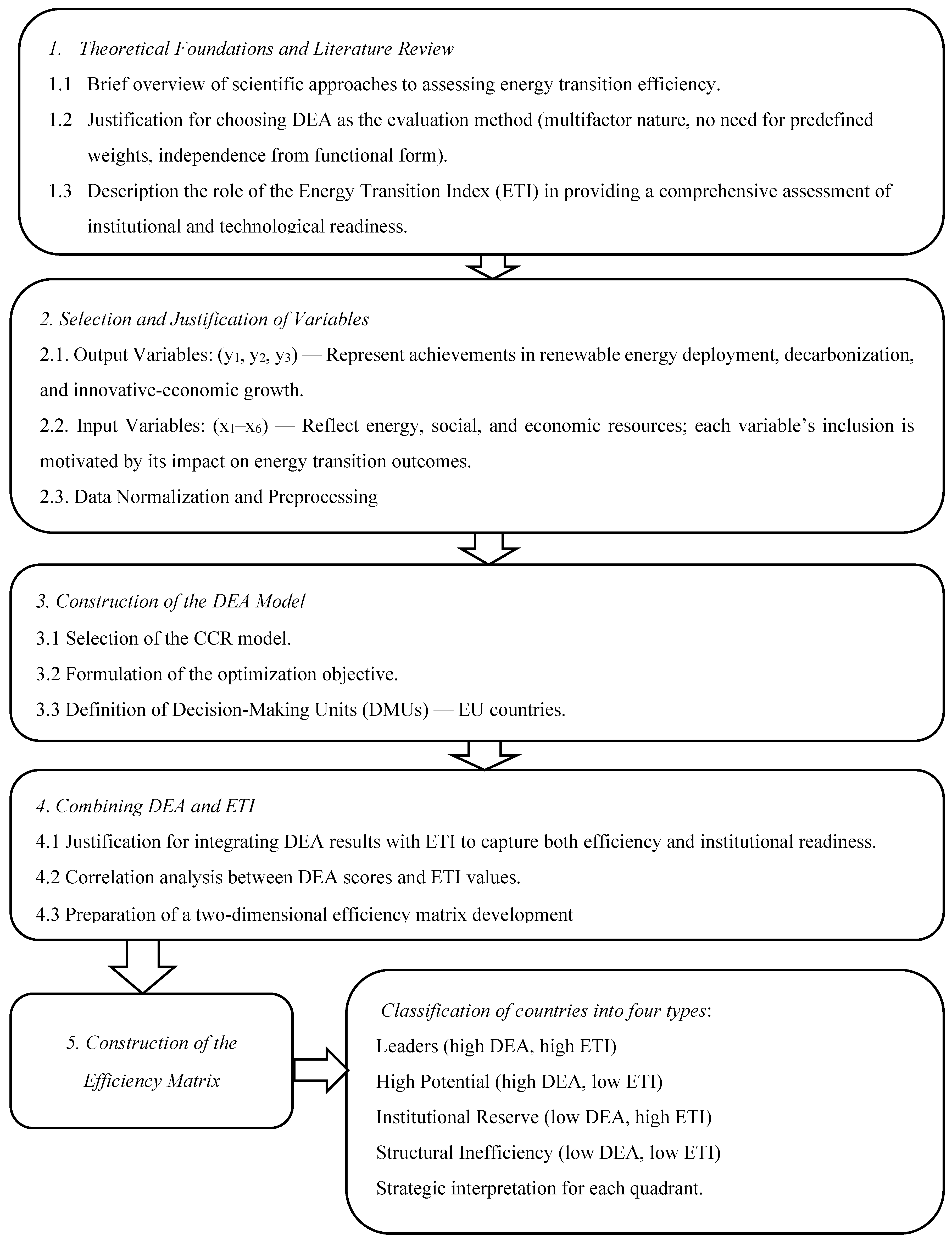

2. Materials and Methods

Research on Factors Affecting the Energy Transition

Methods for Studying the Effectiveness of the Energy Transition

Combining DEA and ETI for Energy Transition Effectiveness Evaluation

Methodology and Data

Outputs (Desirable Results):

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

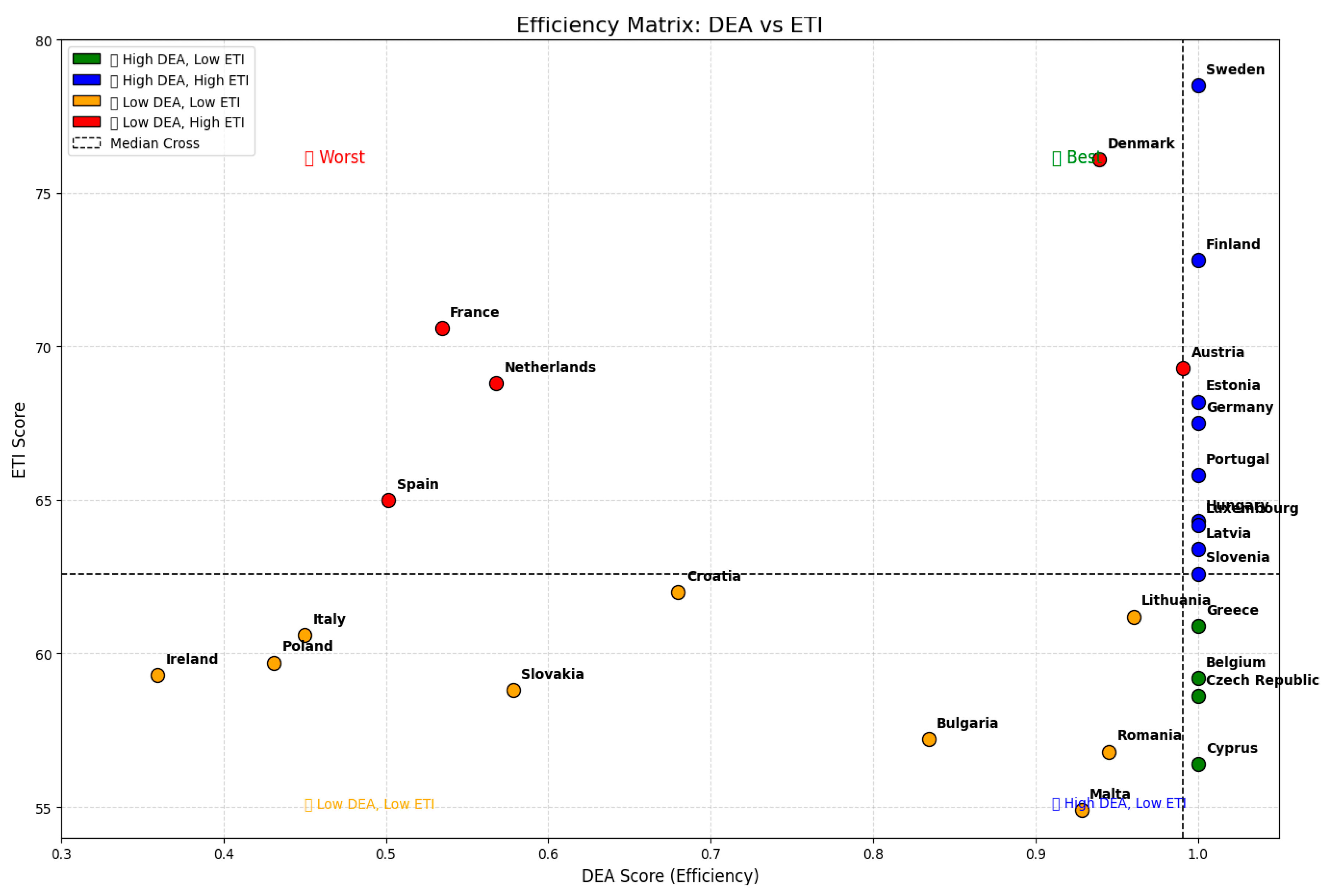

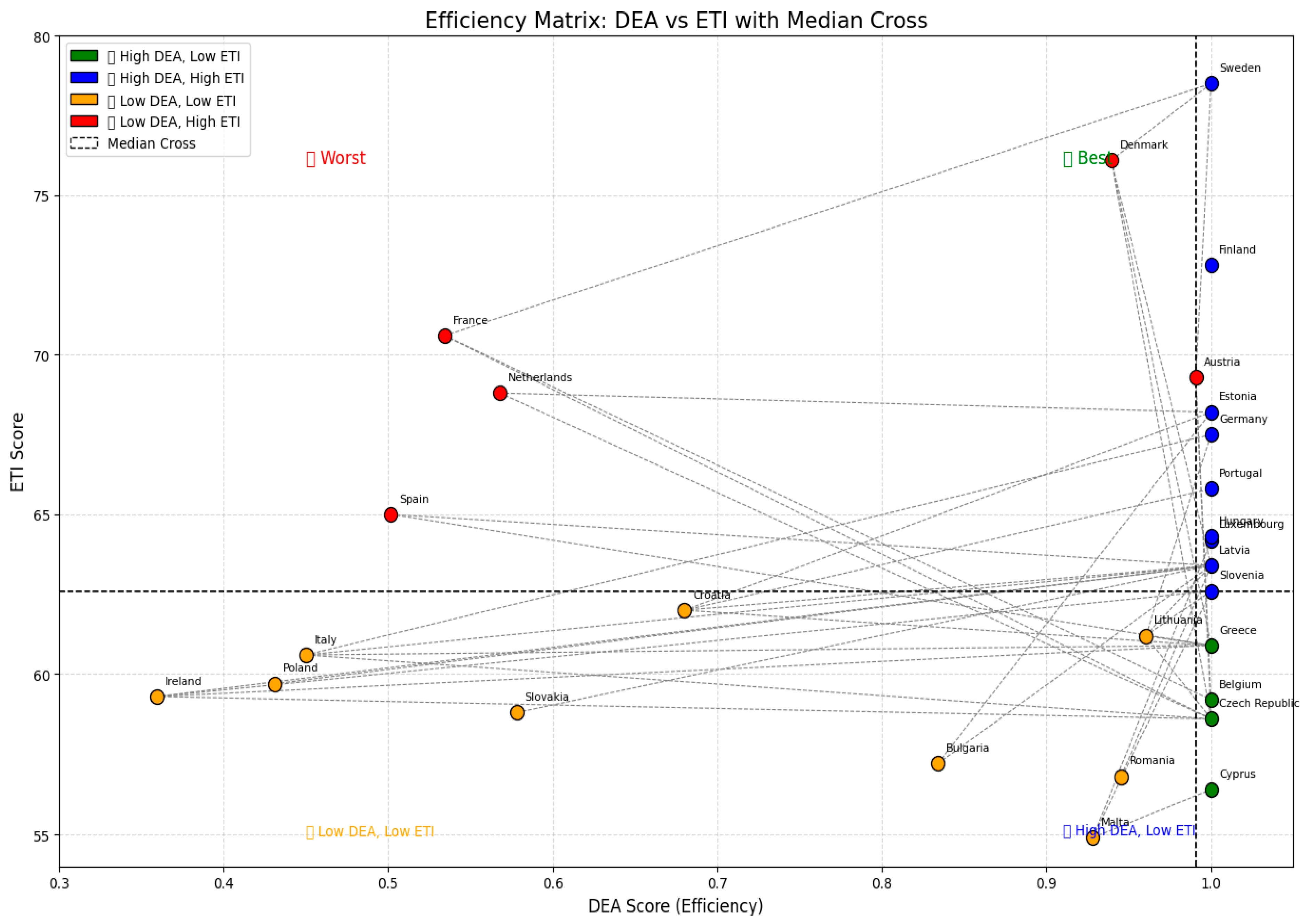

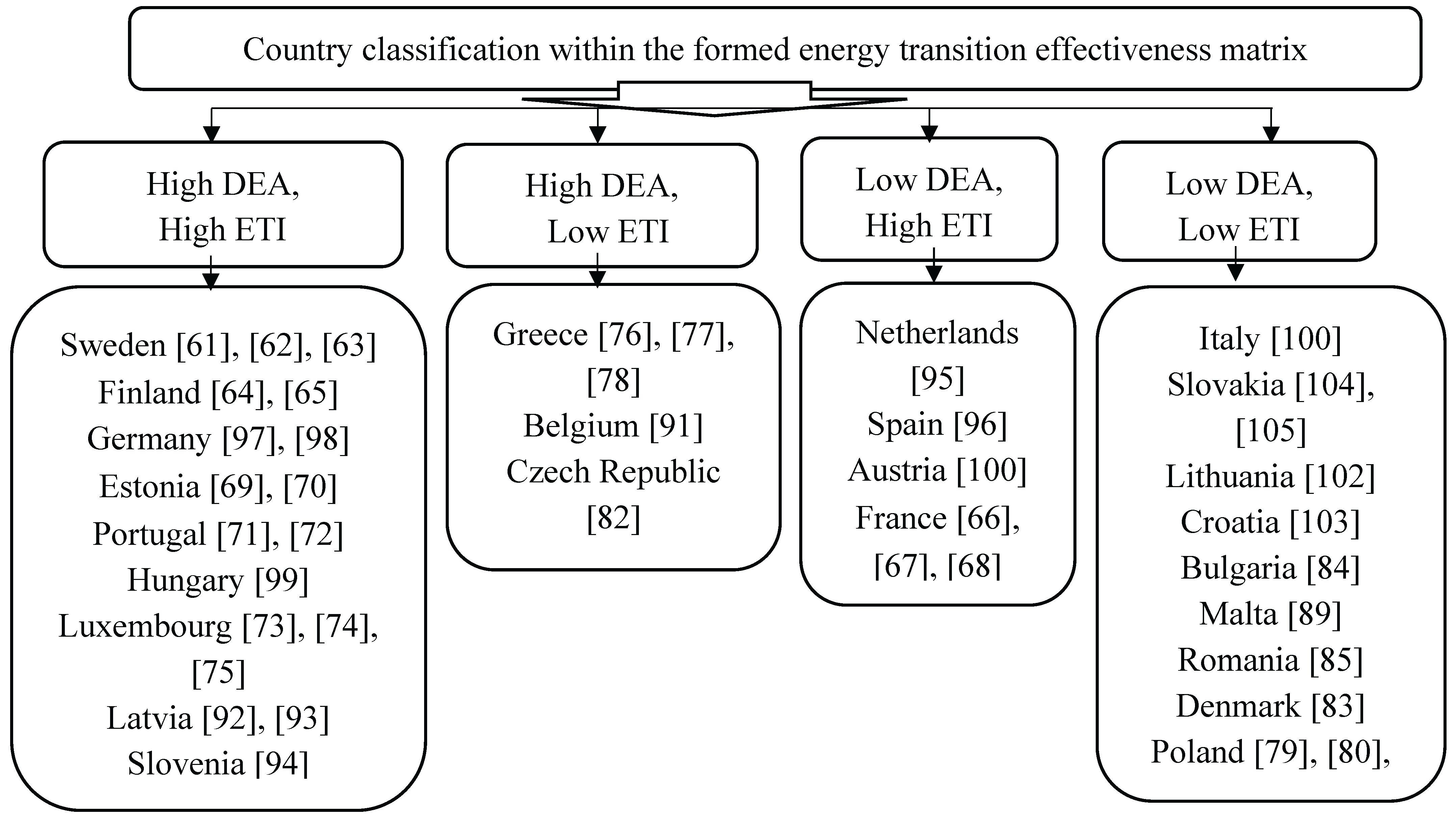

- High DEA, High ETI (blue points): Countries in this quadrant, such as Sweden, Finland, Germany, Estonia, Portugal, Luxembourg, Hungary, Latvia, and partly Slovenia, demonstrate high efficiency and successful energy transition. They are leaders that effectively use resources and actively develop RES, serving as benchmarks for other countries.

- High DEA, Low ETI (green points): Belgium, Czechia, Cyprus, and Greece, while effectively using their resources, show low progress in energy transition. This may indicate their focus on optimizing existing energy systems rather than rapidly transitioning to new energy sources.

- Low DEA, High ETI (red points): France, the Netherlands, Denmark, Spain and Austria show significant progress in the energy transition, but their internal processes and resource use are still suboptimal. This highlights the need for improving efficiency to achieve greater results in the transition.

- Low DEA, Low ETI (yellow points): countries such as Ireland, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Romania, Malta, and Lithuania face challenges both in efficiency and readiness for energy transition. These countries require a comprehensive approach to improving resource efficiency and accelerating the transition to sustainable energy systems.

Verification of the Results OBTAINED.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DEA | Data Envelopment Analysis |

| EIT | Energy Transition Index |

| EIS | Energy Intensity Score |

| DMU | Decision Making Unit |

| RES_share, % | Share of renewable energy in gross final energy consumption (%) |

| Imp_dep, % | Energy import dependency rate (%) |

| Fossi_share, % | Share of fossil fuels in total energy supply (%) |

| CCM_inv, million euro | Investments in carbon containment measures (million EUR) |

| JV_PST, % | Job vacancy rate in professional, scientific, and technical sectors (%) |

| GHG_red, % | Annual reduction rate of greenhouse gas emissions (%) |

| GDP_growth, % | Annual growth rate of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (%) |

| DS | Decoupling Score |

| IDU, million euro | Income by degree of urbanization (million EUR) |

| EC_per_capita | Final energy consumption per capita (kWh/person) |

Appendix A

| № | Indicator name | Variable code | DEA- role | Economic interpretation as a resource (disincentive) |

| 1 | Level of energy import dependence (%) | x1 | Input | Reflects the country's strategic vulnerability; high values indicate the need for external resources, which reduces the stability of the energy system. |

| 2 | Share of fossil fuels in the total energy balance (%) | x2 | Input | Carbon dependency indicator: a decrease in this share indicates a more environmentally efficient energy consumption structure. |

| 3 | Investment in climate change mitigation measures (million euros) | x3 | Input | Despite the positive effect, investments are treated as a resource that is consumed to achieve sustainable development results. |

| 4 | Level of vacancies in the scientific and technical sector (%) | x4 | Input | High demand for innovative labour may indicate inefficient use of human capital, as an underutilized resource. |

| 5 | Income by level of urbanization (million euros) | x5 | Input | The economic capacity of urbanized areas is considered as a resource that promotes transformation, but with high consumption does not always provide proportional efficiency |

| 6 | Energy consumption per capita | x6 | Input | Reflects the energy intensity of the economy; lower consumption with the same results indicates greater energy efficiency. |

| № | Indicator name | Variable code | DEA- role | Value for assessing the efficiency of the energy transition | |||

| 1 | Total share of energy from renewable sources (% in gross final energy consumption) | y1 | Output | The basic indicators of sustainable development. It reflects the actual result of the transition to clean energy sources. The growth of this indicator indicates the achievement of the targets of the ecological transformation. | |||

| 2 | Decoupling Score (DS) | y2 | Output | The Decoupling Score (DS) is a single, “higher = better” index (0 to 1) that summarizes how a country’s economy and its greenhouse-gas emissions move together in each period. It uses annual GDP growth and GHG change as inputs. DS equals 1 when the economy grows while emissions are flat or falling (absolute decoupling); it lies between 0 and 1 when both grow but GDP grows faster (relative decoupling, the closer to 1, the cleaner the growth); it gives mid-range value when both GDP and emissions fall (recognizing emission cuts during downturns without over-rewarding recessions); and it is 0 in the worst case, when the economy contracts while emissions still rise. The score is easy to compare across countries and years, aligns with policy goals of cleaner growth, and should be read alongside multi-year trends and sectoral evidence. | |||

| 3 | EU Innovation Index (EIS) | y3 | Output | The EU Innovation Index (EIS) is an important indicator for assessing the effectiveness of the energy transition, as it reflects the level of innovation and technological progress in a country. A high EIS indicates the development of new renewable energy technologies, the optimization of energy systems through innovations such as smart grids, and active investment in research and development. This allows countries to adapt more quickly to the demands of the energy transition, reduce CO2 emissions, and improve resource efficiency, contributing to a successful transition to sustainable energy systems. | |||

Appendix B

References

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Transition Index 2025: Five strategies for a more resilient and competitive energy system. https://www.weforum. 2025.

- Chwiłkowska-Kubala, A.; Cyfert, S.; Malewska, K.; Mierzejewska, K.; Szumowski, W. The impact of resources on digital transformation in energy sector companies. The role of readiness for digital transformation. Technol. Soc. 2023, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirma, V.; Neverauskienė, L.O.; Tvaronavičienė, M.; Danilevičienė, I.; Tamošiūnienė, R. The Impact of Renewable Energy Development on Economic Growth. Energies 2024, 17, 6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Oleńczuk-Paszel, A.; Sompolska-Rzechuła, A. Quality of Life and Energy Efficiency in Europe—A Multi-Criteria Classification of Countries and Analysis of Regional Disproportions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haby, M.M.; Reveiz, L.; Thomas, R.; Jordan, H. An integrated framework to guide evidence-informed public health policymaking. J. Public Heal. Policy 2025, 46, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariram, N.P.; Mekha, K.B.; Suganthan, V.; Sudhakar, K. Sustainalism: An Integrated Socio-Economic-Environmental Model to Address Sustainable Development and Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, F-C.; Knecht, A. Ressourcen – Merkmale, Theorien und Konzeptionen im Überblick. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Yaryhina, H.; Ziankova, I.; Sati, R.; Litvinenko, V. Efficient use of resources in the field of energy efficiency through the principles of the circular economy.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 02009.

- Desing, H.; Widmer, R.; Bardi, U.; Beylot, A.; Billy, R.G.; Gasser, M.; Gauch, M.; Monfort, D.; Müller, D.B.; Raugei, M.; et al. Mobilizing materials to enable a fast energy transition: A conceptual framework. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosenko, A.; Khomenko, O.; Kononenko, M.; Polyanska, A.; Buketov, V.; Dychkovskyi, R.; Polański, J.; Howaniec, N.; Smolinski, A. Sustainable management of iron ore extraction processes using methods of borehole hydro technology. Int. J. Min. Miner. Eng. 2025, 16, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.-Z. The effect of natural resources and economic factors on energy transition: New evidence from China. Resour. Policy 2022, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA, World Energy Transitions Outlook: 1.5C Pathway (IRENA, Abu Dhabi 2021). Available at: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2021/March/IRENA_World_Energy_Transitions_Outlook_2021.

- Hailes, O.; E Viñuales, J. The energy transition at a critical juncture. J. Int. Econ. Law 2023, 26, 627–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercedes, М.; Cantarero, V. Of renewable energy, energy democracy, and sustainable development: A roadmap to accelerate the energy transition in developing countries. Energy Research & Social Science, 2020, 70, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykhailyshyn, K.; Polyanska, A.; Psyuk, V.; Antoniuk, O.; Dychkovskyi, R.; Dyczko, A.; Šoštarić, S.B. How to achieve the energy transition taking into account the efficiency of energy resources consumption.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 01026.

- Ivano-Frankivsk National Technical University of Oil and Gas; Polyanska, A. ; Pazynich, Y.; Dnipro University of Technology; Petinova, O.; South Ukrainian National Pedagogical University named after K. D. Ushynsky; Nesterova, O.; Mykytiuk, N.; Bodnar, G. Formation of a Culture of Frugal Energy Consumption in the Context of Social Security, pp. 60-87. J. Int. Comm. Hist. Technol. 2024, 29, 60–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.S.; Marques, A.C. How do energy forms impact energy poverty? An analysis of European degrees of urbanisation. Energy Policy 2022, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatzkan, O.; Cohen, R.; Yaniv, E.; Rotem-Mindali, O. Urban Energy Transitions: A Systematic Review. Land 2025, 14, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renou-Maissant, P.; Abdesselam, R.; Bonnet, J. Trajectories for Energy Transition in EU-28 Countries over the Period 2000–2019: a Multidimensional Approach. Environ. Model. Assess. 2022, 27, 525–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cui, J.; Gong, Q. Research on total factor energy efficiency in western China based on the three-stage DEA-Tobit model. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0294329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkin, C.A.; Sargent, E.H.; Schrag, D.P. Energy transition needs new materials. Science 2024, 384, 713–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddi, M. The Geopolitics of Energy Transition: New Resources and Technologies. In: Berghofer, J., Futter, A., Häusler, C., Hoell, M., Nosál, J. (eds) The Implications of Emerging Technologies in the Euro-Atlantic Space. Palgrave Macmillan, 2023, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.A.; Richter, J.; O’lEary, J. Socio-energy systems design: A policy framework for energy transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, K. The emerging field of energy transitions: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 1, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xia, S.; Huang, P.; Qian, J. Energy transition: Connotations, mechanisms and effects. Energy Strat. Rev. 2024, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slameršak, A.; Kallis, G.; O’nEill, D.W. Energy requirements and carbon emissions for a low-carbon energy transition. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraji, M.K.; Streimikiene, D. Challenges to the low carbon energy transition: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Energy Strat. Rev. 2023, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheb, H.; Obaidi, O.; Mukhtar, S.; Shirani, H.; Ahmadi, M.; Yona, A. Comprehensive Analysis and Prioritization of Sustainable Energy Resources Using Analytical Hierarchy Process. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, S.; Rodrigues, F.; Pereira, J. Clustering of renewable energy assets to optimize resource allocation and operational strategies. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2025, 63, 831–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pali, F.; Dsouza, R.; Ryu, Y.; Oishee, J.; Aikkarakudiyil, J.; Gaikwad, M.A.; Norouzzadeh, P.; Buckner, S.; Rahmani, B. Energy Transitions over Five Decades: A Statistical Perspective on Global Energy Trends. Computers 2025, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapukhliak, I.; Zaiachuk, Y.; Polyanska, A.; Kinash, I. Applying fuzzy logic to assessment of enterprise readiness for changes. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 2277–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, M.; Bowhay, R. ; Bowman,M.; Knaack, P., Sachs, L., Smolenska, A., Stewart, F., Tayler, T., Toledano, P., Eds.; Walkate, H. A handbook to strategic national transition planning: supplementary guidance and examples, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Yuan, Y.; Goto, M. A literature study for DEA applied to energy and environment. Energy Econ. 2017, 62, 104–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, W.D.; Tone, K.; Zhu, J. Data envelopment analysis: Prior to choosing a model. Omega 2014, 44, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-N.; Nguyen, T.T.-V.; Chiang, C.-C.; Le, H.-D. Evaluating renewable energy consumption efficiency and impact factors in Asia-pacific economic cooperation countries: A new approach of DEA with undesirable output model. Renew. Energy 2024, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, A.-C.; Wang, S.-M.; Zhan, Y.; Chen, J.; Hsiao, H.-F. A Study of Total-Factor Energy Efficiency for Regional Sustainable Development in China: An Application of Bootstrapped DEA and Clustering Approach. Energies 2022, 15, 3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; You, J.; Li, H.; Shao, L. Energy Efficiency Evaluation Based on Data Envelopment Analysis: A Literature Review. Energies 2020, 13, 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-N.; Dang, T.-T.; Tibo, H.; Duong, D.-H. Assessing Renewable Energy Production Capabilities Using DEA Window and Fuzzy TOPSIS Model. Symmetry 2021, 13, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana-Jiménez, M.; Lozano-Ramírez, J.; Sánchez-Gil, M.C.; Younesi, A.; Lozano, S. A Novel Slacks-Based Interval DEA Model and Application. Axioms 2024, 13, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peykani, P.; Esmaeili, F.S.S.; Pishvaee, M.S.; Rostamy-Malkhalifeh, M.; Lotfi, F.H. Matrix-based network data envelopment analysis: A common set of weights approach. Socio-Economic Plan. Sci. 2024, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.S.; Steffen, V.; de Francisco, A.C.; Trojan, F. Integrated data envelopment analysis, multi-criteria decision making, and cluster analysis methods: Trends and perspectives. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.; Silva, C.; Ferreira, L.M.D. Barriers to energy transition: Comparing developing with developed countries. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fostering Effective Energy Transition 2023 Edition INSIGHT REPORT JUNE 2023. Available at: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Fostering_Effective_Energy_Transition_2023.

- Radtke, J. Understanding the Complexity of Governing Energy Transitions: Introducing an Integrated Approach of Policy and Transition Perspectives. Environ. Policy Gov. 2025, 35, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, Z.T.; Anderson, T.; Seadon, J.; Brent, A. A thematic analysis of the factors that influence the development of a renewable energy policy. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrilho-Nunes, I.; Catalão-Lopes, M. Factors Influencing the Transition to a Low-Carbon Energy Paradigm: A Systemic Literature Review. Green Low-Carbon Econ. 2024, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xia, S.; Huang, P.; Qian, J. Energy transition: Connotations, mechanisms and effects. Energy Strat. Rev. 2024, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconescu, M.; Marinas, L.E.; Marinoiu, A.M.; Popescu, M.-F.; Diaconescu, M. Towards Renewable Energy Transition: Insights from Bibliometric Analysis on Scholar Discourse to Policy Actions. Energies 2024, 17, 4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Zhou, B.; Liao, Z. Decoupling Analysis of Economic Growth and Carbon Emissions in Xinjiang Based on Tapio and Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index Models. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shengrong, Lu; Yao, Liu. Decoupling Elasticity Analysis of Transportation Structure and Carbon Emission Efficiency of Transportation Industry in the Context of Intelligent Transportation. Artificial Intelligence, Medical Engineering and Education, 2024, 86–93. https://doi.org/10.3233/ATDE231318 .

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation and Hollanders, H. European Commission: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation and Hollanders, H., European Innovation Scoreboard 2023, Publications Office of the European Union, 2023. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10. 2777. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhouse gas emissions across EU countries. Quarterly greenhouse gas emissions in the EU. Eurostat website. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?

- Overall share of energy from renewable sources, 2004-2023 (% of gross final energy consumption). Eurostat website. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:T1_Overall_share_of_energy_from_renewable_sources,_2004-2023_(%25_of_gross_final_energy_consumption).

- Energy imports dependency. Eurostat website. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/nrg_ind_id/default/table?

- Share of fossil fuels in gross available energy. Eurostat website. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/NRG_IND_FFGAE__custom_4713496/bookmark/table? 5435.

- Investments in climate change mitigation by NACE Rev. 2 activity. Eurostat website. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/env_ac_ccminv__custom_13950904/bookmark/table? 6654.

- Job vacancy statistics by NACE Rev. 2 activity - quarterly data. Eurostat website. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/jvs_q_nace2__custom_13499757/bookmark/table? 4652.

- Mean and median income by degree of urbanisation. Eurostat website. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ilc_di17/default/table?

- Energy consumption per capita, 2023. Eurostat website. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/images/2/22/Map_1-Energy_consumption_per_capita.

- Ring, M.; Wilson, E.; Ruwanpura, K.N.; Gay-Antaki, M. Just energy transitions? Energy policy and the adoption of clean energy technology by households in Sweden. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliszewska-Nienartowicz, J.; Stefański, O. Decentralisation versus centralisation in Swedish energy policy: the main challenges and drivers for the energy transition at the regional and local levels. Energy Policy 2024, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhuyse, F.; Piseddu, T.; Jokiaho, J. Climate neutral cities in Sweden: True commitment or hollow statements? Cities 2023, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyvönen, J.; Koivunen, T.; Syri, S. Possible bottlenecks in clean energy transitions: Overview and modelled effects – Case Finland. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finland is on track to meet some of the world's most ambitious carbon neutrality targets. This is how it has done it. 2023. https://www.weforum. 2023.

- Lebrouhi, B.E.; Schall, E.; Lamrani, B.; Chaibi, Y.; Kousksou, T. Energy Transition in France. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochot, V.; Khalilpour, K.; Hoadley, A.F.; Sánchez, D.R. French economy and clean energy transition: A macroeconomic multi-objective extended input-output analysis. Sustain. Futur. 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamnatou, C.; Cristofari, C.; Chemisana, D. Renewable energy sources as a catalyst for energy transition: Technological innovations and an example of the energy transition in France. Renew. Energy 2023, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikstena, R.; Lagzdiņa, Ē.; Brizga, J.; Kudrenickis, I.; Ernšteins, R. Energy Citizenship in Energy Transition: The Case of the Baltic States. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meitern, M. Navigating the rise of energy communities in Estonia: Challenges and successes through case studies. Energy Policy 2025, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairrão, D.; Soares, J.; Almeida, J.; Franco, J.F.; Vale, Z. Green Hydrogen and Energy Transition: Current State and Prospects in Portugal. Energies 2023, 16, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, F.; Leitão, S.; Marques, M.C. Energy transition in Portugal: The harnessing of solar photovoltaics in electric mobility and its impact on the carbon footprint. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arababadi, A.; Leyer, S.; Hansen, J.; Arababadi, R.; Pignatta, G. Characterizing the Theory of Energy Transition in Luxembourg, Part Two—On Energy Enthusiasts’ Viewpoints. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arababadi, A.; Leyer, S.; Hansen, J.; Arababadi, R. Characterizing the theory of energy transition in Luxembourg—Part three—In the residential sector. Energy Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1296–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arababadi, A.; Leyer, S.; Arababadi, R.; Pignatta, G. Theoretical Considerations about Energy Transition in Luxembourg. Built Environment Research Forum. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 9.

- Chatzinikolaou, D. Integrating Sustainable Energy Development with Energy Ecosystems: Trends and Future Prospects in Greece. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaprakakis, D.A.; Proka, A.; Zafirakis, D.; Damasiotis, M.; Kotsampopoulos, P.; Hatziargyriou, N.; Dakanali, E.; Arnaoutakis, G.; Xevgenos, D. Greek Islands’ Energy Transition: From Lighthouse Projects to the Emergence of Energy Communities. Energies 2022, 15, 5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezilis, L.; Lavidas, G. Future scenarios for 100% renewables in Greece, untapped potential of marine renewable energies. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodny, J.; Tutak, M.; Grebski, W. Empirical Assessment of the Efficiency of Poland’s Energy Transition Process in the Context of Implementing the European Union’s Energy Policy. Energies 2024, 17, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarski, S.; Urych, B.; Smolinski, A. National Energy and Climate Plan—Polish Participation in the Implementation of European Climate Policy in the 2040 Perspective and Its Implications for Energy Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janikowska, O.; Generowicz-Caba, N.; Kulczycka, J. Energy Poverty Alleviation in the Era of Energy Transition—Case Study of Poland and Sweden. Energies 2024, 17, 5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechancová, V.; Pavelková, D.; Saha, P. Community Renewable Energy in the Czech Republic: Value Proposition Perspective. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denmark 2023 Energy Policy Review. International Energy Agency (IEA). 23. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/9af8f6a2-31e7-4136-94a6-fe3aa518ec7d/Denmark_2023. 20 December.

- Zhelev, P. Green Transformation: Bulgaria’s Path in the Energy Transition Process. In: Bulgaria in the Global Economy. Societies and Political Orders in Transition 2025, Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-87923-4_13.

- Paliwa kopalne w transformacji energetycznej – przypadek Rumunii. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. - Miner. Resour. Manag. 2023, 39, 85–106. [CrossRef]

- Akçaba, S.; Eminer, F. Sustainable energy planning for the aspiration to transition from fossil energy to renewable energy in Northern Cyprus. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venizelou, V.; Poullikkas, A. Navigating the Evolution of Cyprus’ Electricity Landscape: Drivers, Challenges and Future Prospects. Energies 2025, 18, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maonaigh, C. , Reilly, L., Fitzgerald, L. Marginalised experiences in Ireland’s energy transition – moving towards a just and inclusive policy agenda. Public policy. Available at https://publicpolicy.

- Kotzebue, J.R.; Weissenbacher, M. The EU's Clean Energy strategy for islands: A policy perspective on Malta's spatial governance in energy transition. Energy Policy 2020, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crichton, R.; Mette, J.; Tambo, E.; Nduhuura, P.; Nguedia-Nguedoung, A. The impact of Austria’s climate strategy on renewable energy consumption and economic output. Energy Policy 2023, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpens, G.; Jeanmart, H.; Maréchal, F. Belgian Energy Transition: What Are the Options? Energies 2020, 13, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberga, A.; Pakere, I.; Bohvalovs, Ģ.; Brakovska, V.; Vanaga, R.; Spurins, U.; Klasons, G.; Celmins, V.; Blumberga, D. Impact of the 2022 energy crisis on energy transition awareness in Latvia. Energy 2024, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagzdiņa, Ē.; Brizga, J.; Kudreņickis, I..; Ikstena, R.; Ernšteins, R. Advancing Energy Citizenship: Hindering and Supporting Factors in Latvia’s Energy Transition. In: Fahy, F., Vadovics, E. (eds) Energy Citizenship Across Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, 2025. Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-70157-3_7 .

- Crnčec, D., Sučić, B., Merše, S. Slovenia: Drivers and Challenges of Energy Transition to Climate Neutrality. In: Mišík, M., Oravcová, V. (eds) From Economic to Energy Transition. Energy, Climate and the Environment. Palgrave Macmillan, 2021. Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55085-1_9 .

- Proka, A.; Hisschemöller, M.; Loorbach, D. Transition without Conflict? Renewable Energy Initiatives in the Dutch Energy Transition. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garha, N.S.; Mira, R.G.; González-Laxe, F. Energy Transition Narratives in Spain: A Case Study of As Pontes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Tu, H.; Zhang, H.; Luo, S.; Ma, Z.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z. Systematic evaluation and review of Germany renewable energy research: A bibliometric study from 2008 to 2023. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulich, A.; & Zema, T. The Green Energy Transition in Germany: A Bibliometric Study. Forum Scientiae Oeconomia, 2023, 11(2), 175–195. [CrossRef]

- Gulyás, T.; Palkovics, L.; Gondola, C. Analysis of Potential Energy Transition Schemes in Hungary: From Natural Gas to Electricity. Chemical Engineering Transactions, 2024, 114, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murano, G.; Caffari, F.; Calabrese, N.; Dall’ombra, M. Meeting 2030 Targets: Heat Pump Installation Scenarios in Italy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crichton, R.; Mette, J.; Tambo, E.; Nduhuura, P.; Nguedia-Nguedoung, A. The impact of Austria’s climate strategy on renewable energy consumption and economic output. Energy Policy 2023, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genys, D.; Krikštolaitis, R.; Pažėraitė, A. Lithuanian Energy Security Transition: The Evolution of Public Concern and Its Socio-Economic Implications. Energies 2024, 17, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slijepčević, S.; Villa, Ž.K.-D. Public Attitudes toward Renewable Energy in Croatia. Energies 2021, 14, 8111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figulová, A.; Gondášová, I. energy transition in Slovakia – destiny in/and change. EJTS European Journal of Transformation Studies, 2023, 11 (1), 169-187.

- Karatayev, M.; Gaduš, J.; Lisiakiewicz, R. Creating pathways toward secure and climate neutral energy system through EnergyPLAN scenario model: The case of Slovak Republic. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 2525–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasniqi, I. Evaluating strategic approaches to energy transition: leadership, policy, and innovation in European countries. Econ. Environ. 2024, 90, 929–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | GHG Growth Rate (%) [52] | GDP Growth Rate (%) | (GHG-GDP elasticity) | Regime | DS |

| Belgium | 5.1 | 1.1 | 4,667 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,176 |

| Bulgaria | 4.0 | 4.1 | 0,981 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,505 |

| Czechia | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1,233 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,448 |

| Denmark | 2.6 | 3.9 | 0,655 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,604 |

| Germany | 1.6 | -0.4 | -4,040 | Worst-case (GDP↓,GHG↑) | 0,000 |

| Estonia | -11.3 | 1.2 | -9,390 | Absolute decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↓) | 1,000 |

| Ireland | 3.1 | 9.2 | 0,333 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,750 |

| Greece | 8.1 | 2.7 | 3,006 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,250 |

| Spain | 2.4 | 3.2 | 0,757 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,569 |

| France | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0,331 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,751 |

| Croatia | 6.1 | 3.9 | 1,566 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,390 |

| Italy | 4.1 | 1.0 | 4,126 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,195 |

| Cyprus | 4.4 | 2.6 | 1,674 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,374 |

| Latvia | -1.4 | -0.4 | 3,453 | Both falling (GDP↓,GHG↓) |

0,467 |

| Lithuania | 10.8 | 4.0 | 2,704 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,270 |

| Luxembourg | -2.3 | 1.8 | -1,292 | Absolute decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↓) | 1,000 |

| Hungary | 4.7 | 0.4 | 11,783 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,078 |

| Malta | 1.7 | 2.8 | 0,615 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,619 |

| Netherlands | 4.1 | 1.9 | 2,163 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,316 |

| Austria | -1.7 | -0.5 | 3,382 | Both falling (GDP↓,GHG↓) |

0,464 |

| Poland | 1.6 | 4.1 | 0,400 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,714 |

| Portugal | 2.4 | 2.9 | 0,813 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,552 |

| Romania | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0,662 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,602 |

| Slovenia | 9.4 | 1.5 | 6,266 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,138 |

| Slovakia | 2.6 | 1.7 | 1,514 | Relative decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↑) |

0,398 |

| Finland | -6.1 | 0.9 | -6,789 | Absolute decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↓) | 1,000 |

| Sweden | -2.3 | 1.9 | -1,232 | Absolute decoupling (GDP↑,GHG↓) | 1,000 |

|

RES_ share, % [54] |

Imp_ dep, % [55] |

Fossi_ share, % [56] |

CCM_inv, million euro [57] | JV_PST, % [58] | DS |

EIS [52] |

IDU, mln euro [59] | EC_per capita [60] | |

| Austria | 40.84 | 61.1 | 66.42 | 2756.33 | 7.4 | 0.464 | 119.9 | 34130 | 145 |

| Belgium | 14.74 | 76.1 | 73.62 | 3682.74 | 8.5 | 0.176 | 125.8 | 29244 | 200 |

| Bulgaria | 22.58 | 39.7 | 66.32 | 194.90 | 0.7 | 0.505 | 46.7 | 10048 | 112 |

| Croatia | 28.05 | 55.7 | 67.28 | 353.61 | 1.93 | 0.390 | 69.6 | 120690 | 96 |

| Czech Republic | 48.59 | 41.7 | 71.47 | 981.11 | 8.0 | 0.448 | 94.7 | 16665 | 149 |

| Denmark | 44.92 | 38.9 | 57.23 | 5039.79 | 3.35 | 0.604 | 137.6 | 37853 | 117 |

| Estonia | 40.95 | 3.5 | 68.51 | 172.73 | 2.38 | 1.000 | 98.6 | 18216 | 138 |

| Finland | 50.75 | 29.6 | 38.26 | 1769.69 | 3.7 | 1.000 | 134.3 | 32690 | 253 |

| France | 22.28 | 44.9 | 48.15 | 21606.03 | 2.95 | 0.751 | 105.3 | 29445 | 138 |

| Germany | 21.55 | 66.4 | 78.77 | 18589.47 | 6.8 | 0.00 | 117.8 | 31091 | 130 |

| Greece | 25.27 | 75.6 | 82.18 | 339.83 | 3.2 | 0.250 | 79.5 | 12144 | 34 |

| Hungary | 17.36 | 62.1 | 69.43 | 1424.54 | 3.7 | 0.078 | 70.4 | 9548 | 106 |

| Ireland | 15.25 | 77.9 | 87.67 | 425.47 | 1.68 | 0.750 | 115.8 | 38642 | 115 |

| Italy | 19.56 | 78.4 | 78.32 | 4976.76 | 2.08 | 0.195 | 90.3 | 24143 | 103 |

| Latvia | 43.22 | 32.7 | 57.08 | 378.11 | 2.7 | 0.467 | 52.5 | 14390 | 98 |

| Lithuania | 31.93 | 68.0 | 64.46 | 804.90 | 1.78 | 0.270 | 83.8 | 16115 | 107 |

| Poland | 16.50 | 48.0 | 88.00 | 2899.62 | 0.9 | 0.714 | 62.8 | 12740 | 112 |

| Portugal | 35.16 | 66.9 | 68.27 | 150.14 | 2.43 | 0.552 | 85.6 | 15705 | 90 |

| Romania | 25.76 | 27.9 | 72.47 | 1258.56 | 0.83 | 0.602 | 33.1 | 9263 | 68 |

| Slovakia | 16.99 | 57.7 | 63.78 | 417.20 | 0.43 | 0.398 | 65.6 | 9781 | 127 |

| Slovenia | 25.07 | 49.3 | 60.93 | 141.72 | 4.1 | 0.138 | 95.1 | 20487 | 120 |

| Spain | 24.85 | 68.4 | 72.38 | 2911.79 | 0.98 | 0.569 | 89.2 | 22278 | 109 |

| Sweden | 66.39 | 26.4 | 31.39 | 5921.94 | 3.9 | 1.000 | 134.5 | 31849 | 187 |

| Luxembourg | 11.62 | 90.6 | 78.69 | 137.00 | 5.0 | 1.000 | 117.2 | 64863 | 234 |

| Netherlands | 17.15 | 40.45 | 89.13 | 2485.59 | 4.53 | 0.316 | 128.7 | 32404 | 179 |

| Malta | 15.08 | 97.56 | 96.28 | 64.66 | 2.78 | 0.619 | 85.8 | 24848 | 247 |

| Cyprus | 20.21 | 92.21 | 88.83 | 16.93 | 2.85 | 0.374 | 105.4 | 23907 | 125 |

| RES_share, % | Imp_dep, % |

Fossi_ share, % |

CCM_inv, million euro | JV_PST, % | DS | EIS | IDU, mln euro | EC_per capita | |

| Austria | 0.534 | 0.388 | 0.381 | 0.873 | 0.136 | 0.464 | 0.169 | 0.777 | 0.493 |

| Belgium | 0.057 | 0.228 | 0.254 | 0.830 | 0.000 | 0.176 | 0.113 | 0.821 | 0.242 |

| Bulgaria | 0.200 | 0.615 | 0.383 | 0.992 | 0.967 | 0.505 | 0.870 | 0.993 | 0.644 |

| Croatia | 0.300 | 0.445 | 0.366 | 0.984 | 0.814 | 0.390 | 0.651 | 0.000 | 0.717 |

| Czech Republic | 0.675 | 0.594 | 0.292 | 0.955 | 0.062 | 0.448 | 0.411 | 0.934 | 0.475 |

| Denmark | 0.608 | 0.624 | 0.544 | 0.767 | 0.638 | 0.604 | 0.000 | 0.743 | 0.621 |

| Estonia | 0.536 | 1.000 | 0.344 | 0.993 | 0.758 | 1.000 | 0.373 | 0.920 | 0.525 |

| Finland | 0.714 | 0.723 | 0.879 | 0.919 | 0.595 | 1.000 | 0.032 | 0.790 | 0.000 |

| France | 0.195 | 0.560 | 0.704 | 0.000 | 0.688 | 0.751 | 0.309 | 0.819 | 0.525 |

| Germany | 0.181 | 0.331 | 0.163 | 0.140 | 0.211 | 0.000 | 0.189 | 0.804 | 0.562 |

| Greece | 0.249 | 0.233 | 0.103 | 0.985 | 0.657 | 0.250 | 0.556 | 0.974 | 1.000 |

| Hungary | 0.105 | 0.377 | 0.328 | 0.935 | 0.595 | 0.078 | 0.643 | 0.997 | 0.671 |

| Ireland | 0.066 | 0.209 | 0.006 | 0.981 | 0.845 | 0.750 | 0.209 | 0.736 | 0.630 |

| Italy | 0.145 | 0.204 | 0.171 | 0.770 | 0.796 | 0.195 | 0.453 | 0.866 | 0.685 |

| Latvia | 0.577 | 0.690 | 0.546 | 0.983 | 0.719 | 0.467 | 0.814 | 0.954 | 0.708 |

| Lithuania | 0.371 | 0.314 | 0.416 | 0.964 | 0.833 | 0.270 | 0.515 | 0.939 | 0.667 |

| Poland | 0.089 | 0.527 | 0.000 | 0.866 | 0.942 | 0.714 | 0.716 | 0.969 | 0.644 |

| Portugal | 0.430 | 0.326 | 0.349 | 0.994 | 0.752 | 0.552 | 0.498 | 0.942 | 0.744 |

| Romania | 0.258 | 0.741 | 0.274 | 0.942 | 0.950 | 0.602 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.845 |

| Slovakia | 0.098 | 0.424 | 0.428 | 0.981 | 1.000 | 0.398 | 0.689 | 0.995 | 0.575 |

| Slovenia | 0.246 | 0.513 | 0.478 | 0.994 | 0.545 | 0.138 | 0.407 | 0.899 | 0.607 |

| Spain | 0.242 | 0.310 | 0.276 | 0.866 | 0.932 | 0.569 | 0.463 | 0.883 | 0.658 |

| Sweden | 1.000 | 0.757 | 1.000 | 0.726 | 0.570 | 1.000 | 0.030 | 0.797 | 0.301 |

| Luxembourg | 0.000 | 0.074 | 0.164 | 0.994 | 0.434 | 1.000 | 0.195 | 0.501 | 0.087 |

| Netherlands | 0.101 | 0.607 | -0.020 | 0.886 | 0.492 | 0.316 | 0.085 | 0.792 | 0.338 |

| Malta | 0.063 | 0.000 | -0.146 | 0.998 | 0.709 | 0.619 | 0.496 | 0.860 | 0.027 |

| Cyprus | 0.157 | 0.057 | -0.015 | 1.000 | 0.700 | 0.374 | 0.308 | 0.869 | 0.584 |

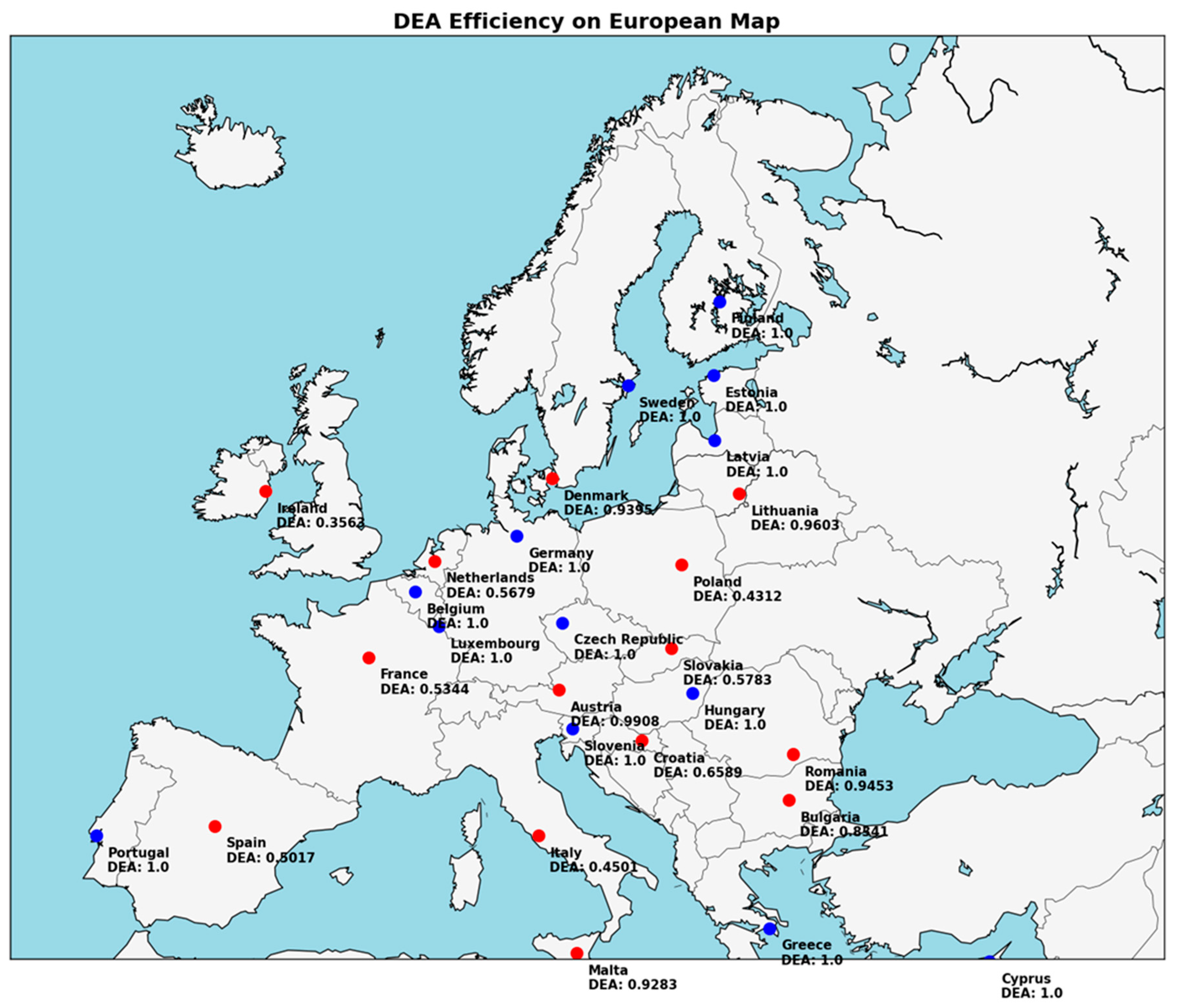

| # | Country | DEA Efficiency Index | ETI |

| 1 | Belgium | 1 | 59.2 |

| 2 | Czech Republic | 1 | 58.6 |

| 3 | Estonia | 1 | 68.2 |

| 4 | Finland | 1 | 72.8 |

| 5 | Greece | 1 | 60.9 |

| 6 | Latvia | 1 | 63.4 |

| 7 | Portugal | 1 | 65.8 |

| 8 | Slovenia | 1 | 62.6 |

| 9 | Sweden | 1 | 78.5 |

| 10 | Luxembourg | 1 | 64.2 |

| 11 | Cyprus | 1 | 56.4 |

| 12 | Germany | 1 | 67.5 |

| 13 | Hungary | 1 | 64.3 |

| 14 | Austria | 0.9908 | 69.3 |

| 15 | Lithuania | 0.9603 | 61.2 |

| 16 | Romania | 0.9453 | 56.8 |

| 17 | Denmark | 0.9395 | 76.1 |

| 18 | Malta | 0.9283 | 54.9 |

| 19 | Bulgaria | 0.8341 | 57.2 |

| 20 | Croatia | 0.6589 | 62.0 |

| 21 | Spain | 0.5017 | 65.0 |

| 22 | Slovakia | 0.5783 | 58.8 |

| 23 | Netherlands | 0.5679 | 68.8 |

| 24 | France | 0.5344 | 70.6 |

| 25 | Italy | 0.4501 | 60.6 |

| 26 | Poland | 0.4312 | 59.7 |

| 27 | Ireland | 0.3563 | 59.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).