1. Introduction

Applications in data augmentation [

7,

11], simulation [

9], anomaly detection, and biomedical signal synthesis [

13] are all supported by time series generation, a fundamental task in machine learning. Synthesizing realistic sequences that capture semantic structure and temporal connections is the aim. Nevertheless, it is still difficult to produce time series that are both semantically and structurally matched, especially in fields with intricate latent dynamics like physiological monitoring and human activity detection.

Advances in time-series generation employing foundation and transformer-based designs have been examined in recent surveys [

24,

25]. For better long-range forecasting, transformer variations like Autoformer [

35] use decomposition and auto-correlation techniques. Even while these techniques perform remarkably well in sequence modeling and forecasting, they frequently put realism or prediction accuracy ahead of interpretability and consistency across classes. The majority of current methods, in example, handle time series as undifferentiated temporal vectors without explicitly modeling frequency patterns or regime transitions, which restricts their use in contexts where structural control and semantic accuracy are crucial.

We provide FMD-GAN, a Frequency–Markov Diffusion Generative Adversarial Network that is intended to synthesize time series with both structural integrity and class consistency in order to overcome these constraints. The requirement to combine structural priors, specifically frequency decomposition and latent regime modeling, with semantic awareness in order to provide interpretable and controllable generation is what drives FMD-GAN.

Our system comprises three essential elements: frequency-aware denoising in a conditional diffusion process, Markov modeling of latent state transitions, and frequency-domain segmentation by spectral clustering. Stable and high-quality synthesis is made possible by score-based generative models [

27], which provide a rigorous method of training diffusion using stochastic differential equations (SDEs). By utilizing the interpretability of symbolic state modeling [

4], the expressiveness of conditional diffusion [

12,

22], and the compactness of Fourier-based representations [

19], FMD-GAN breaks down sequences into spectral regimes and applies class-conditioned diffusion guided by latent states. The methodology works well for conditional generation and structure-sensitive data augmentation since it also guarantees that created samples stay semantically aligned with their targets through a class-consistency loss.

We test FMD-GAN on four exemplary datasets from the UCR Time Series Archive, which span different domains and sequence lengths: ECG200, GunPoint, FordA, and UWaveGestureLibrary_X. FMD-GAN achieves competitive or superior performance across multiple metrics, including Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), Dynamic Time Warping (DTW), Class Consistency Accuracy (CCA), and Spectral Distance (SD), when compared to six state-of-the-art baselines, including GAN-based, conditional, and diffusion models. Our framework’s interpretability, robustness, and semantic coherence are further illustrated by extensive qualitative evaluations, which include t-SNE projections, residual maps, latent state overlays, and training dynamics.

Our main contributions are as follows:

We propose FMD-GAN, an innovative generative framework that combines spectral clustering, Markov-guided latent modeling, and frequency-aware diffusion to generate realistic and class-consistent time series.

We run extensive tests on four distinct UCR datasets, illustrating that FMD-GAN attains comparable or superior performance relative to six leading generative baselines across many assessment parameters.

We conduct comprehensive interpretability analysis utilizing t-SNE visualization, residual plots, and latent state overlays, demonstrating FMD-GAN’s capacity to maintain semantic structure and reveal significant generative dynamics.

2. Related Work

2.1. GAN-Based Models for Time Series Generation

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) are extensively utilized for time series generation because of their capacity to model intricate distributions. C-RNN-GAN [

8] was the initial framework to adapt GANs for sequential data through the utilization of recurrent architectures. TimeGAN [

7] further implemented supervised embedding alignment to guarantee temporal and semantic accuracy. RCGAN-UCR [

9] integrated class-conditional methods to improve discriminability. Despite their achievements in short-range realism, GAN-based models frequently experience instability, a deficiency in interpretability, and a constrained capacity to capture long-term structure [

29].

2.2. Diffusion Models for Temporal Generation

Diffusion-based generative models have recently garnered attention for their resilience and sampling consistency, especially in time-series domains [

36]. Score-based Stochastic Differential Equation frameworks and denoising diffusion probabilistic models provide well-founded training objectives and controllable generation. In the time-series domain, CSDI [

10] utilized conditional score matching for imputation, whilst Autoregressive DDPMs [

12] facilitate sequence-level conditioning. DiffWave [

22], Diffusion-TS [

15], and SigDiffusions [

16] aim to achieve high-fidelity signal generation for speech and physiological data. Nevertheless, the majority of these models are deficient in class-conditioning and neglect discontinuous latent transitions, hence constraining their semantic control and interpretability.

2.3. Class-Conditional and Structured Sequence Models

Conditioning mechanisms for regulating the semantics of generated sequences have been the subject of numerous studies. Sequence-level conditioning in DDPMs enhances label fidelity [

12], while class-aware GANs [

31] and conditional VAEs [

32] allow label-guided generation. In parallel, interpretable temporal transitions are provided by symbolic models such as HMMs [

4]. However, the majority of current frameworks do not incorporate symbolic state modeling into end-to-end diffusion processes.

2.4. Hybrid Models with Semantic and Structural Constraints

A condensed and comprehensible viewpoint for capturing global temporal trends is provided by frequency-domain modeling. While neural Fourier operators [

17] have been used to learn periodic and structured representations in time series data, informer [

19] introduced spectral attention for long-range forecasting. These methods emphasize how crucial it is to use signal structure to enhance generalization.

To improve interpretability, robustness, and semantic control, recent surveys [

24,

25] highlight the importance of integrating deep learning with symbolic priors, such as Markov segmentation and state transitions. In fields like physiological signal generation [

14], human motion modeling [

33], and dynamic system simulation [

34] that demand both high-fidelity synthesis and structural awareness, such hybrid approaches are especially pertinent.

However, in diffusion-based generative models, this hybrid approach is still not well studied. Our work advances this field by presenting FMD-GAN, a class-aware diffusion pipeline for semantically controllable and structurally faithful time series production that combines frequency-domain segmentation with Markovian latent transitions.

3. The Proposed Model

The suggested

Fourier–Markov Diffusion GAN (FMD-GAN) architecture is described in this section. It uses frequency-domain noise modulation and class-aware latent states to produce realistic and semantically coherent time series. As shown in

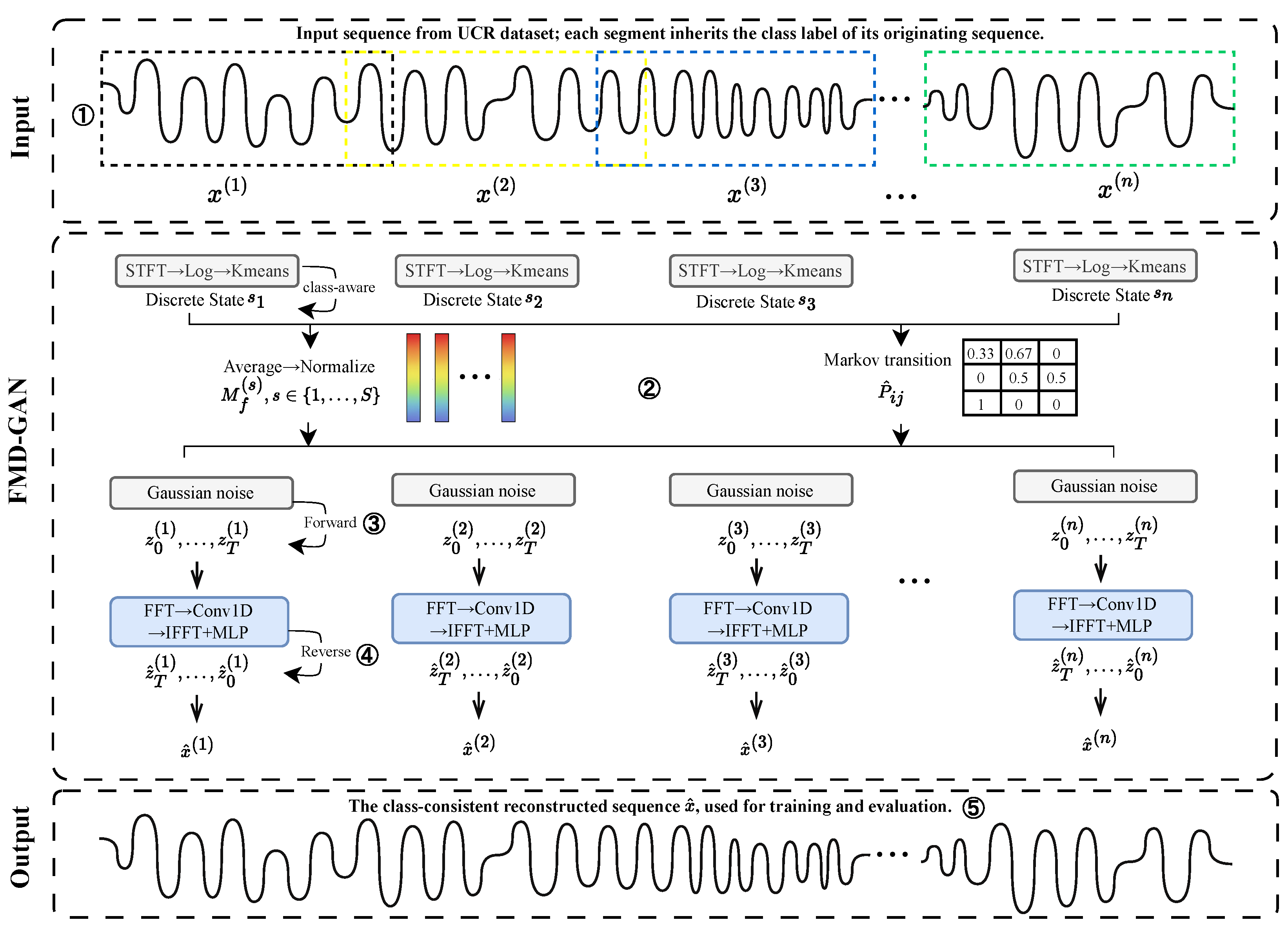

Figure 1, the model comprises five main stages: sliding-window segmentation, class-guided state assignment, forward diffusion with state-conditioned noise, reverse generation, and dual-branch adversarial training.

We present a unique approach that combines latent state assignment and spectral clustering to guarantee class-consistent generation, allowing class-discriminative latent states to direct each time-series segment. In addition to controlling the forward diffusion process through frequency-domain masks, these states also condition adversarial learning and reverse generation, guaranteeing that the synthesized sequences match their original class labels semantically.

We denote vectors in

bold lowercase, matrices in uppercase, and time indices

. A complete pipeline is visualized in

Figure 1.

3.1. Sliding-Window Segmentation

Inspired by local receptive field strategies used in convolutional architectures [

37], we segment each input time series

into overlapping sub-sequences using a sliding-window approach. Each sub-sequence

is extracted with a fixed window length

l and hop size

h, where

indexes the window position. The total number of extracted windows is given by

.

This method breaks down each long sequence into a set of fixed-size segments that serve as separate training examples for the subsequent generative modeling and spectral analysis stages.

3.2. Class-Aware State Assignment via Spectral Features

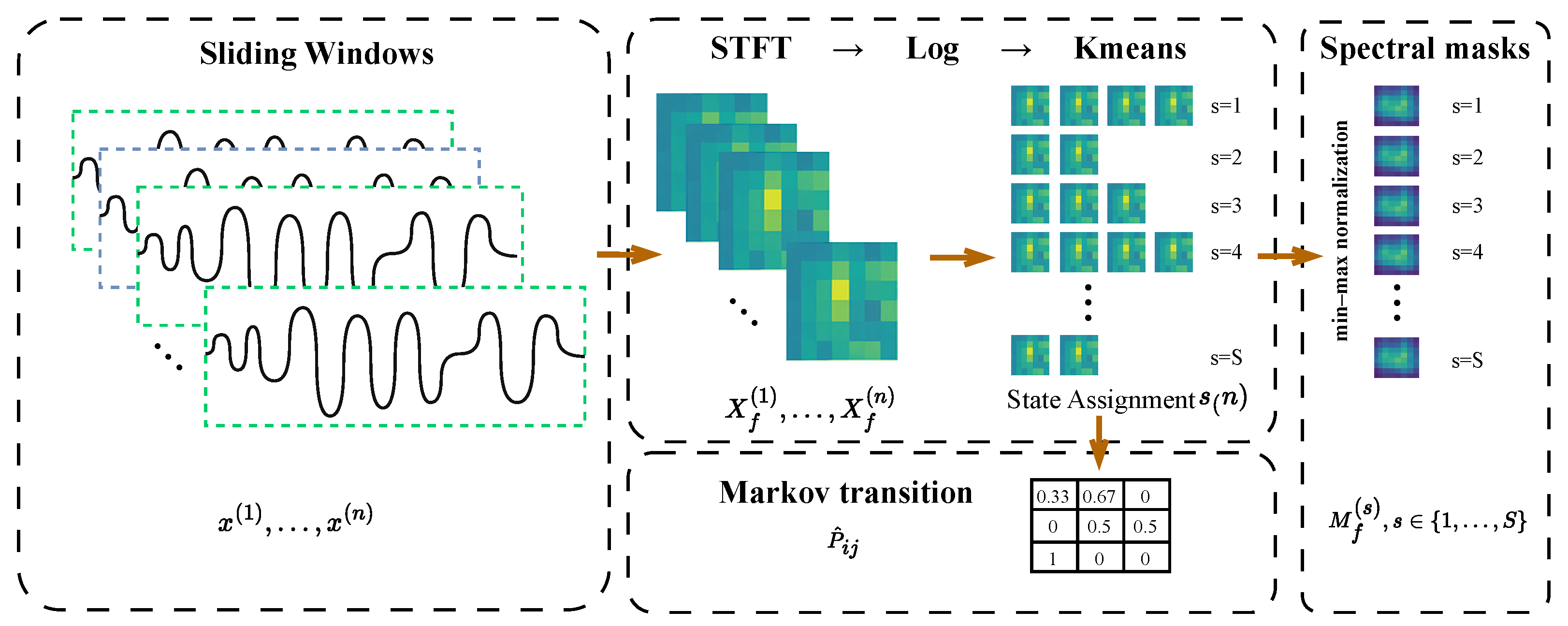

Building on the windowed segments obtained from the previous step, we now compute spectral features for each sub-sequence and assign class-aware latent states.

For each window

, we compute the magnitude spectrum via the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) [

2]:

where

K is the number of frequency bins. The magnitudes are logarithmically converted [

29] and aggregated across all windows to create a global spectral feature matrix.

An overview of this procedure is illustrated in

Figure 2, which summarizes the key stages from segmentation to state assignment, spectral mask construction, and transition modeling.

To promote class consistency during generation, we cluster the log-spectrum of each window using

k-means [

3], and align the resulting clusters with the ground-truth class labels:

where each latent state

represents a prototype spectral mode. When class labels

are available, we assign each cluster to a class-dominant label using majority voting over window-to-class associations. This implicitly encourages state assignments to reflect class-discriminative features.

The temporal transitions between adjacent latent states yield the empirical Markov transition matrix [

4]:

which captures the class-aware temporal structure within the dataset.

Finally, we group all windows by their assigned state

, average their STFT magnitudes, and apply min–max normalization across frequency bins to construct a state-specific spectral mask:

where

is the set of windows assigned to state

s. This procedure yields a bank of spectral masks

, each reflecting the characteristic frequency distribution of its corresponding latent state. These masks are later used to modulate frequency-domain noise during forward diffusion, enabling class-sensitive perturbation. Normalization ensures that each mask defines a valid variance template bounded in

, suitable for stochastic noise control [

21].

3.3. Fourier–Markov Diffusion with State-Conditioned Noise

The forward diffusion process begins with an initial latent vector for each segmented input. At every diffusion step , the latent representation is gradually perturbed with class-aware, state-conditioned Gaussian noise, modulated in the frequency domain.

Specifically, at each step, a spectral noise vector

is sampled from a zero-mean Gaussian distribution with a diagonal covariance matrix shaped by a state-specific spectral mask:

where

is the Fourier-domain mask corresponding to the current Markov state

, and ⊙ denotes elementwise multiplication. By encoding class-discriminative spectral patterns, these masks guarantee that injected noise preserves the original class’s semantic structure. This technique promotes class-consistent generative routes over time by encouraging the diffusion trajectory to stay in line with class semantics.

The latent is then updated as:

where

is a cosine-based variance schedule controlling the noise scale at each step.

At each diffusion step t, the Markov prior samples a new latent state , whose spectral mask defines the injection pattern of noise. The estimate of the state transition matrix over class-aware spectral clusters simulates temporal transitions in this stochastic process while preserving label-consistent fluctuations.

The model integrates both controlled variability and structural consistency by conditioning frequency-domain perturbations on latent states that evolve according to a Markov process and encapsulate class semantics. This ensures that the diffusion trajectory remains in line with class-specific dynamics that are seen in sequences from the real world.

The sampled state sequence is reused in the reverse process, enabling consistent class-sensitive conditioning across both forward and reverse diffusion stages.

3.4. Reverse Generation and Segment Aggregation

The reverse generator

reconstructs the class-consistent latent vector

from a heavily perturbed latent

by progressively denoising it through

T steps. At each reverse step

, the model learns to approximate the class-aware conditional distribution:

where

is the Markov state sampled during the forward process. State transitions encapsulate spectral patterns that correspond with class labels, hence each reversal step is directed by a semantically significant structure.

The reverse generator follows a hybrid spectral–temporal procedure:

where each channel’s temporal dimension is subjected to a fixed-size 1D FFT. To guarantee constant spectral resolution across all steps, we employ zero-padding for segments that are smaller than the FFT size, which is 64 by default.

where

denotes a state-conditioned convolutional filter applied in the frequency domain, and

are FiLM [

5] parameters generated from state embeddings. These layers function as class-sensitive modulators, enabling the generator to modify the denoising trajectory according to latent class attributes.

At the end of the process, the cleaned latent vector

is decoded into a window-level time series segment:

Here, represents the reconstructed segment of the n-th window. These segments are later aggregated to form the full-length synthetic sequence , which preserves both the structural variation and the semantic class identity of the original data.

After denoising each latent segment via the reverse process, the generator produces a set of window-level reconstructions

. To obtain the final sequence

, these overlapping segments are aggregated into a coherent time series through an overlap-aware stitching strategy [

38], similar to the classic overlap-add technique in STFT reconstruction.

Given a fixed hop size

, where

w is the segment/window length, overlapping regions are averaged to ensure temporal smoothness and reduce boundary artifacts. For each time step

, the reconstructed value is computed by:

where

is the set of windows covering position

l, and

is the offset of the

n-th window.

While preserving the class-discriminative local patterns present in each segment, this averaging technique promotes continuity. Both global structure and class-specific consistency are maintained in the final output , enabling reliable downstream applications like data augmentation, classifier training, or visual analysis.

The reconstructed sequence is then used in all evaluation scenarios and fed into a dual-branch discriminator during adversarial training.

3.5. Adversarial Training with Class-Aware Dual-Branch Discriminator

We use a class-aware dual-branch discriminator

and the WGAN-GP framework [

1] to synthesize realistic and class-consistent time series. Working with the entire reconstructed sequence

, the discriminator gives the generator adversarial feedback that directs it to replicate both class-specific temporal dynamics and global structure.

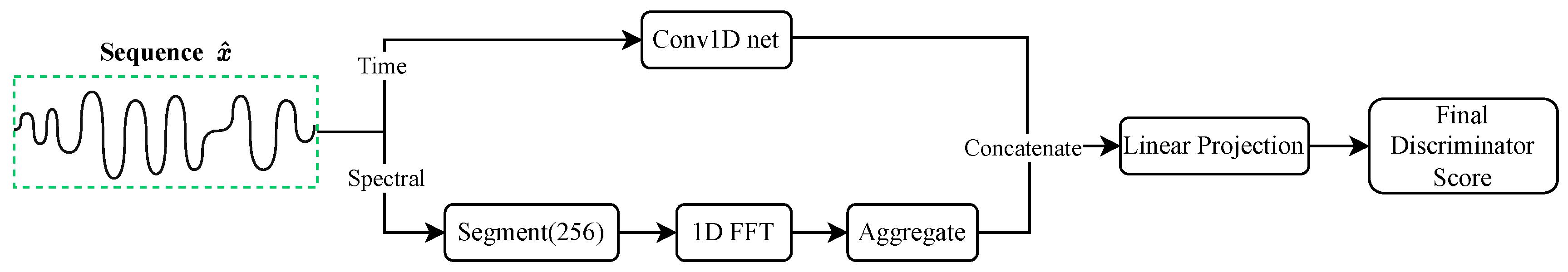

Two parallel branches make up the discriminator, as seen in

Figure 3. The

time branch evaluates local signal coherence and temporal continuity using a 1D convolutional network. The

spectral branch applies a fixed-size 1D FFT to each channel of

in order to assess holistic frequency-domain features. In order to improve numerical stability and highlight informative frequency patterns like rhythm or repetition, log-magnitude scaling (

is employed. The spectral branch divides each full-length input into non-overlapping windows of length 256 in order to guarantee constant frequency resolution over sequences of different lengths. A global spectral representation is created by averaging the magnitude spectra obtained from a 1D FFT of each window. The discriminator can capture long-range spectral structure while keeping a stable frequency bin size (

) across datasets thanks to this aggregation method. Because there is no windowing or framing, global spectral properties are preserved.

A scalar discriminator score is obtained by concatenating the outputs of both branches and passing them through a linear projection head. Both temporal fidelity and spectral coherence are reflected in this score, which allows to function as an auxiliary classifier that promotes class-consistent generation as well as a realism evaluator.

To further preserve class-specific dynamics, we incorporate a transition-level regularization based on Markov state assignments. From training data, we estimate an empirical state transition matrix , capturing typical evolution patterns. During generation, a latent sequence is sampled, inducing a predicted transition matrix . A KL divergence penalty is used to encourage consistency between and , promoting realistic intra-class transitions.

The final training objective integrates four components: an adversarial loss

, a spectral reconstruction loss, a transition regularization term, and a latent reconstruction penalty. The overall loss is defined as:

The spectrum loss enforces frequency alignment, the KL term maintains temporal dynamics, and the reconstruction penalty guarantees successful reversal of the diffusion process. Collectively, these aims empower FMD-GAN to generate coherent, structurally accurate, and class-sensitive time series.

3.6. Pseudocode of FMD-GAN Training

We summarize the complete training workflow of FMD-GAN in Algorithm 1, which integrates spectral clustering, forward diffusion, reverse generation, and adversarial optimization.

|

Algorithm 1: Training Procedure of FMD-GAN |

-

Require:

Time series , window length l, hop size h, number of states S

-

Ensure:

Trained generator , discriminator

- 1:

Segment into windows

- 2:

Compute STFT magnitudes

- 3:

Cluster via k-means

- 4:

Estimate transition matrix from

- 5:

Compute min–max normalized spectral masks

- 6:

while not converged do

- 7:

Sample n, initialize ,

- 8:

for to do

- 9:

Sample

- 10:

- 11:

- 12:

end for

- 13:

for down to 0 do

- 14:

- 15:

end for

- 16:

- 17:

Aggregate from all

- 18:

Compute total loss L via Eq. ( 14) - 19:

Update , using WGAN-GP - 20:

end while |

3.7. Computational Complexity Analysis

We now analyze the computational complexity of each stage in the proposed FMD-GAN framework. Let L be the length of the input time series, C the number of channels, l the window length, h the hop size, and the number of segments per sequence. The segmentation process itself requires operations, as each window is extracted from the original sequence.

The class-aware state assignment involves computing the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) for each segment, with a per-window cost of , resulting in a total complexity of . The subsequent spectral clustering via k-means over log-magnitude spectra incurs complexity, where I is the number of iterations and K is the number of frequency bins.

During the forward diffusion stage, each latent segment is perturbed over T steps. At each step, generating spectral noise and performing elementwise operations with the spectral mask requires , yielding a total of per segment. Given N segments, the overall complexity of forward diffusion is .

The reverse generation process applies a frequency-domain convolution using FFT-based filtering and FiLM modulation. Each FFT/IFFT pair has a complexity of , and the convolution and FiLM layers contribute an additional . Across T reverse steps and N segments, the total reverse generation complexity is .

Segment aggregation involves averaging overlapping regions, with a total time proportional to the sequence length, . The dual-branch discriminator performs both temporal and spectral discrimination. The time-branch convolution operates in , while the spectral branch computes an FFT and MLP over the whole sequence, incurring .

The total training difficulty per sequence per iteration is primarily determined by the STFT-based spectral clustering, the iterative forward and reverse diffusion processes, and the evaluation of the discriminator, culminating in an overall cost of:

This complexity is manageable in reality, as the fundamental elements—such as segment-wise operations and frequency-domain transformations—are highly parallelizable. Furthermore, the implementation of FFT-based spectral modeling diminishes computational expenses relative to recurrent or attention-based methods, rendering FMD-GAN particularly appropriate for extensive time series.

4. Experiment

We evaluate the effectiveness of FMD-GAN in the realm of class-preserving time series generation. Experiments are conducted using meticulously selected datasets from the UCR Time Series Archive [

6], covering diverse domains and sequence lengths.

4.1. Datasets

We assess FMD-GAN using four representative datasets from the UCR Time Series Archive [

6], chosen to encompass a varied spectrum of sequence lengths, class quantities, and application fields. This diversity facilitates a thorough evaluation of the model’s generalization ability across different structural and semantic patterns.

Table 1 delineates the principal attributes of the chosen datasets. ECG200 consists of brief univariate heartbeat impulses derived from electrocardiograms. GunPoint captures motion dynamics using arm motions. UWaveGestureLibrary_X comprises multivariate time series that depict spatial hand motions for eight distinct gesture types. FordA comprises extensive univariate sequences captured from engine sensors throughout various operating circumstances.

For each dataset, we utilize the official training and testing divisions supplied by UCR. During training, sequences are partitioned into overlapping sub-sequences utilizing a sliding window of length and a hop size of . Every segment is normalized to a mean of zero and a variance of one. During inference, produced segments are recombined by overlap-aware averaging to recreate the complete time series for assessment.

4.2. Baselines

We compare FMD-GAN against six competitive generative baselines, each representing a distinct paradigm in time series generation:

TimeGAN [

7] (Adversarial + Supervised): A hybrid model integrating RNN-based autoencoding, temporal supervision, and adversarial learning. It serves as a prevalent standard for sequential generation.

RCGAN-UCR [

9] (Conditional GAN): A recurrent conditional GAN initially designed for the synthesis of medical signals. We modify it for UCR datasets by conditioning on one-hot class labels.

TTS-CGAN [

18] (Prototype-guided GAN): A GAN model that produces time series by conditioning on class prototypes, hence improving semantic integrity and temporal coherence.

CSDI [

10] (Score-based Diffusion): A conditional score-based diffusion model for imputing time series data. We adapt it for unconditional generation by class-aware reverse sampling.

DiffWave [

22] (Denoising Diffusion): An audio synthesis diffusion model, modified for unconditional time series production with Gaussian noise schedules.

Diffusion-TS [

15] (Denoising Diffusion): A comprehensible time series generator utilizing autoregressive denoising diffusion, providing high fidelity across many tasks.

To facilitate an equitable comparison, all baselines are trained on identical windowed and normalized sequences as FMD-GAN (see to

Section 4.1), employing the same segment lengths, class conditioning procedures, and evaluation metrics. Hyperparameters are optimized through validation, and all models are assessed using identical splits.

These baselines provide a thorough assessment of FMD-GAN across adversarial, conditional, and diffusion-based frameworks, especially in structure-aware and class-preserving generation tasks.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

To thoroughly examine the quality of generated time series, we employ five representative metrics that together measure realism, structural fidelity, semantic consistency, and interpretability.

Fréchet Inception Distance (FID): Evaluates the distributional similarity between authentic and produced samples inside a learned embedding space. We employ a pretrained LSTM encoder to derive fixed-length representations and calculate the Fréchet distance between the empirical Gaussian distributions of these embeddings. A reduced FID signifies enhanced distributional alignment and authenticity.

Dynamic Time Warping (DTW): Determines structural alignment by calculating the best alignment cost between generated and actual sequences. Dynamic Time Warping accommodates local time variations and distortions, rendering it a resilient metric for temporal accuracy. Reduced DTW values signify enhanced structural preservation.

Class Consistency Accuracy (CCA): Evaluates semantic coherence by confirming that generated sequences accurately correspond to their designated class labels. A one-dimensional convolutional neural network classifier is trained on actual data and employed to forecast class labels for generated samples. A higher CCA indicates enhanced semantic fidelity and superior class-conditional generation quality.

Spectral Distance (SD): Assesses the preservation of frequency-domain structure by calculating the average Euclidean distance between the normalized power spectra of actual and produced sequences. We utilize the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to derive the magnitude spectrum for each sequence. Reduced SD values signify enhanced global structural alignment in the frequency domain, reinforcing the spectral modeling rationale underlying FMD-GAN.

All measures are averaged across five independent trials with distinct random seeds to provide statistical robustness. Classifiers employed for CCA and embeddings utilized for FID and t-SNE remain constant throughout all methodologies. Standard deviations are presented in the relevant result tables where appropriate.

4.4. Implementation Details

Training Setup. All models are executed in PyTorch 1.13 and trained on a solitary NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. Both datasets utilize a fixed window length of and a hop size of for time series segmentation. The quantity of latent states is established at , and the count of diffusion steps is predetermined at . A linear beta schedule is utilized for the forward diffusion process.

Optimization. The Adam optimizer is employed with a learning rate of , a batch size of 64, and no weight decay. Each model undergoes training for 5000 iterations, although empirical convergence generally occurs at approximately 3800 steps. The checkpoint exhibiting the minimal validation Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) is chosen for final assessment.

Model Architecture. The generator has three temporal convolutional layers (kernel size 5, dilations 1–2–4), succeeded by two linear projections to align with the input channel dimension C. Every diffusion step is influenced by a spectral mask , with representing the quantity of positive frequency bins derived from a 256-point FFT. Zero-padding is utilized to guarantee that all segments conform to the FFT input dimensions.

Despite each input segment is 64 in length, we utilize a 256-point FFT to improve frequency resolution. The enhanced spectral granularity enables each mask to identify more distinctive frequency patterns for each latent state, thus enhancing both structure-aware generation and spectral consistency. Empirical observations indicate that reduced FFT sizes (e.g., 64) result in diminished modularity and alignment in generated sequences.

The reverse generator replicates the forward pipeline and executes incremental denoising based on latent states. The discriminator functions at the full-sequence level and has a dual-branch architecture, simultaneously optimizing for adversarial realism and class-aware precision. It employs 1D FFT-based spectral feature extraction, succeeded by LeakyReLU activations and LayerNorm.

Clustering and Latent State Assignment. We execute K-means clustering on the segment-level spectral embeddings to derive state labels for frequency masking. The cluster count is established at , with 100 iterations employed. To ensure numerical stability, we can employ PCA to reduce embeddings to 32 dimensions prior to clustering.

Loss Function and Weighting. The total loss combines three terms: reconstruction loss, spectral alignment loss, and KL divergence for latent regularization:

with weights set to

,

, and

. The spectral loss quantifies the mean squared error between actual and generated magnitude spectra, whereas the KL loss regulates the distribution of assignments among latent states.

4.5. Quantitative Results

Table 2 presents a comprehensive comparison of seven generative models across four benchmark datasets using three metrics: FID (↓), DTW (↓), and CCA (↑). All results are averaged over five distinct random seeds, and we noted a low standard deviation across runs (often below 1.0), signifying steady and consistent performance.

FMD-GAN consistently attains the lowest FID and DTW across three of four datasets, indicating robust distribution alignment and preservation of temporal structure. For example, in the GunPoint dataset, FMD-GAN decreases the average FID by more than 50% relative to TimeGAN, demonstrating its capacity to produce structurally accurate and realistic sequences. The DTW gap between actual and produced sequences is significantly reduced, indicating enhanced temporal alignment relative to both GAN and diffusion-based benchmarks.

Regarding CCA, which measures semantic similarity, FMD-GAN attains the highest or nearly top scores across the majority of datasets. While DiffWave attains the highest score on ChlorineConc, FMD-GAN continues to be very competitive overall, sustaining a robust equilibrium between structural fidelity and semantic preservation.

These results highlight the effectiveness of our Fourier–Markov diffusion models in producing class-consistent, high-fidelity time series. In contrast to models like CSDI and TimeGAN, which either lack structural priors or rely on unconditional generation, FMD-GAN more effectively preserves a balance between diversity and class specificity.

To enhance the evaluation of global structural faithfulness in the frequency domain, we utilize the Spectral Distance (SD) measure for all models. This measure calculates the mean Euclidean distance between the normalized power spectra of actual and created sequences. For each sequence, we implement the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and normalize its magnitude spectrum prior to calculating the distance. Reduced SD values signify enhanced conformity with the global frequency attributes of the target distribution.

Table 3 demonstrates that FMD-GAN attains the lowest standard deviation across all four datasets, hence affirming its efficacy in maintaining spectral structure. DiffWave and Diffusion-TS demonstrate competitive outcomes owing to their diffusion-centric architecture, whilst TTS-CGAN and CSDI exhibit middling performance. TimeGAN and RCGAN-UCR are excluded from this evaluation due to their generated sequences exhibiting spectrum instability, resulting in unreliable or noisy FFT results. This constraint highlights the benefit of frequency-aware systems like FMD-GAN in maintaining global structure.

These findings further corroborate the efficacy of FMD-GAN in maintaining spectral integrity. FMD-GAN attains the lowest standard deviation across all datasets, a benefit attributable to its spectral-aware architecture, which corresponds with its exceptional performance in FID and DTW, hence affirming cross-domain consistency rather than metric-specific optimization.

4.6. Ablation Study

We conduct ablation tests using the ECG200 and GunPoint datasets to assess the contribution of each essential component in FMD-GAN. These benchmarks were chosen for their unique temporal and spectral attributes, allowing us to evaluate the influence of each design decision on time-domain alignment, semantic coherence, and preservation of frequency structure.

We construct the following ablated variants:

NoMask: Eliminates the state-conditioned spectral mask , substituting it with isotropic Gaussian noise, therefore disregarding frequency-aware modulation.

NoMarkov: Substitutes the acquired Markovian transition matrix with uniform random sampling, hence undermining temporal state continuity.

NoDiff:Completely disables the forward diffusion, hence reducing the model to a traditional GAN trained on latent vectors.

FMD-GAN (Full): The comprehensive model integrating spectrum masking and Markov-guided denoising diffusion.

Table 4 presents the performance across four metrics: Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), Dynamic Time Warping (DTW), Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA), and Spectral Distance (SD). The complete strategy routinely attains greater outcomes. The lack of diffusion (NoDiff) results in the most significant degradation, underscoring the essential function of denoising-based temporal refinement. NoMask results in increased spectral divergence and diminished cross-correlation accuracy, signifying compromised spectral alignment and semantic integrity. NoMarkov demonstrates minor variations in FID and CCA, although it significantly enhances DTW and SD, underscoring its significance for temporal smoothness and structural consistency.

These findings affirm that each element significantly enhances the model’s efficacy, and that the integration of frequency-aware diffusion and Markov state transitions is crucial for structure-preserving generation. All data are averaged across five iterations, with standard deviations below 1.0, highlighting the statistical reliability of our conclusions.

4.7. Qualitative Analysis

4.7.1. Structure Visualization and Residual Analysis

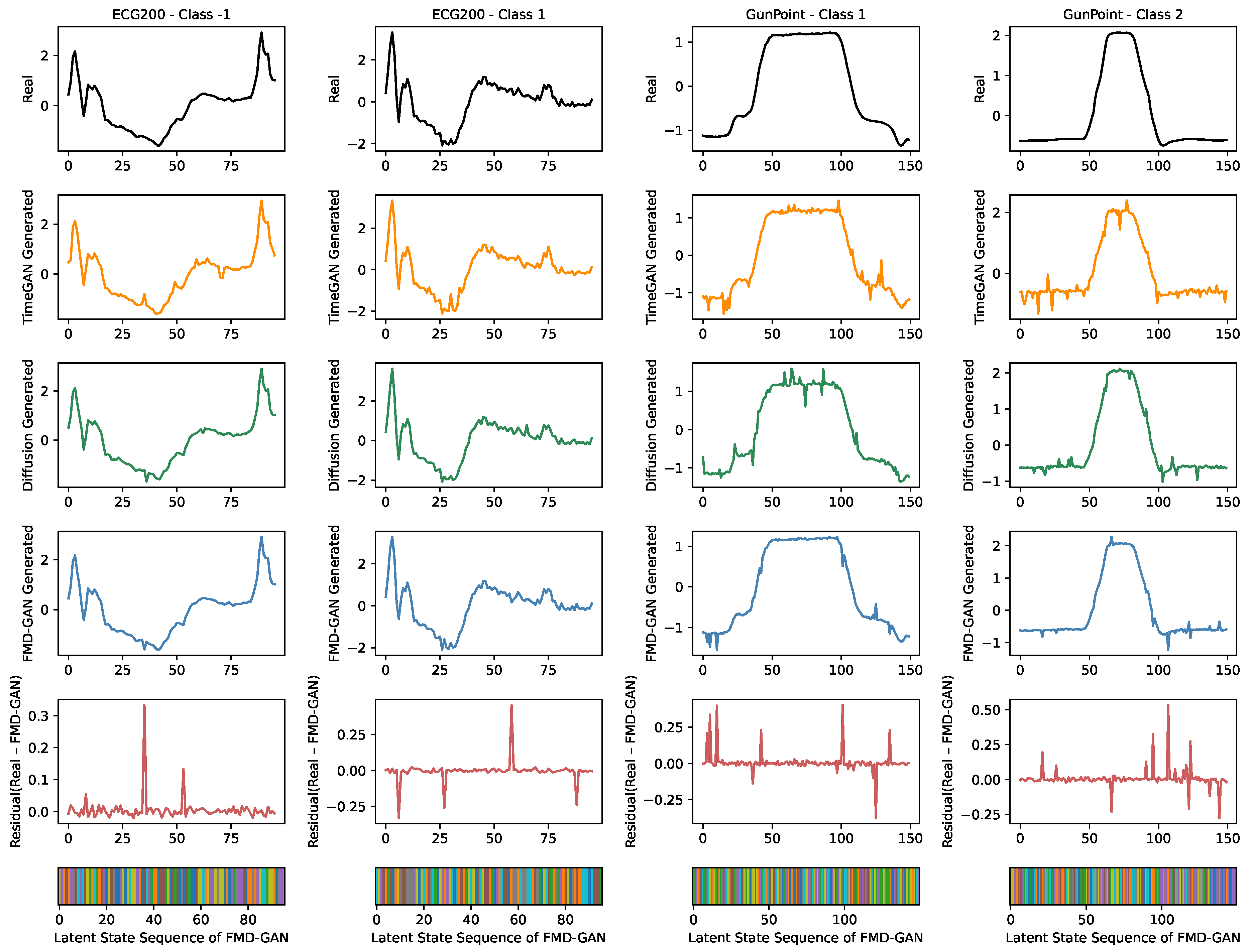

To further demonstrate the structural fidelity and class consistency of FMD-GAN, we present a qualitative comparison against two representative baselines: TimeGAN and Diffusion-TS. These methods are selected to exemplify two predominant paradigms in time series generation—GAN-based and diffusion-based approaches—providing a varied contrast to our Fourier–Markov design.

We visualize generated samples on two datasets, ECG200 and GunPoint, which exhibit distinct temporal patterns and frequency characteristics. For each dataset, we select one representative test sequence from each class and show four aligned visualizations:

Real: The original ground-truth sequence from the test set.

Generated: The sequence synthesized by each method (TimeGAN, Diffusion-TS, FMD-GAN).

Residual (FMD-GAN only): The pointwise discrepancy between the actual output and that of FMD-GAN, emphasizing its reconstruction accuracy.

Latent State (FMD-GAN only): A color-coded bar representing the Markov state allocated to each timestep throughout the creation process.

This comparison enables a visual evaluation of each model’s ability to represent global trends, local variations, and semantic class attributes.

Figure 4 illustrates representative class-specific samples from the ECG200 and GunPoint datasets, comparing the generative performance of

FMD-GAN against two competitive baselines:

TimeGAN and

Diffusion-TS. Each column displays the actual time series (top), succeeded by the outputs from the three models. For FMD-GAN, we further show the residual error and the latent Markov state sequence to improve interpretability.

Superior fidelity is demonstrated by FMD-GAN in maintaining both fine-grained temporal fluctuations and the global structure. While it preserves the abrupt transitions and plateau segments that define motion patterns on GunPoint, it recovers smooth baseline oscillations with precise synchronization on the ECG200 dataset. In contrast, Diffusion-TS introduces high-frequency noise and loses temporal consistency in some places, whereas TimeGAN tends to over-smooth and distort local details.

The FMD-GAN’s residual curves show accurate magnitude and time reconstruction; they are low-magnitude and concentrated close to signal boundaries. The Markov model’s latent state sequences frequently match significant signal regions like peaks, troughs, and constant segments, confirming the function of frequency-aware, state-conditioned diffusion in directing creation.

No post-processing or cherry-picking is done; all samples are chosen at random from the test sets that have been reserved. Latent noise and state routes are sampled to create FMD-GAN sequences, which show reliable and comprehensible outcomes across classes. These visual results corroborate the previously reported quantitative gains.

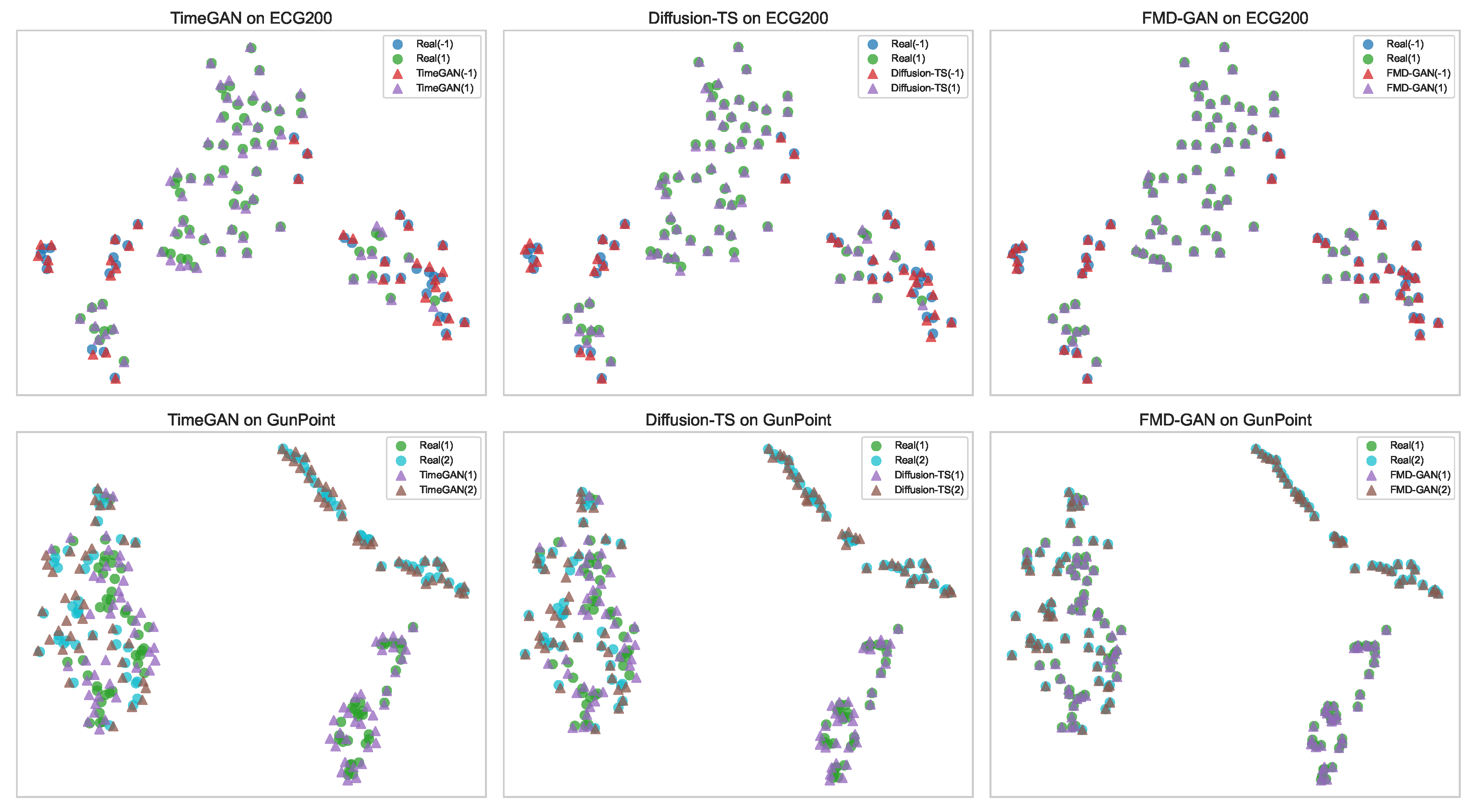

4.7.2. Latent Space Alignment via t-SNE

We use t-SNE [

23] to visualize the distribution of generated and real samples in order to assess whether FMD-GAN maintains the semantic structure of real sequences in the latent space.

Figure 5 presents a 2×3 grid: each column corresponds to a generative model (TimeGAN, Diffusion-TS, and FMD-GAN), and each row corresponds to a dataset (ECG200 and GunPoint).

Triangles in each subplot represent created samples, while circles represent real samples. Ground-truth class labels, indicated in parentheses (e.g., (1), (2), or ()), are used to color-code the data points. Strong alignment between generated and real data is shown by FMD-GAN, which forms close, class-consistent clusters. On the other hand, particularly on the GunPoint dataset, TimeGAN and Diffusion-TS show more dispersed distributions, misaligned classes, or mode collapse.

These findings imply that FMD-GAN’s superior class-aware modeling abilities are demonstrated by its ability to produce realistic sequences while preserving the underlying semantic structure in latent space.

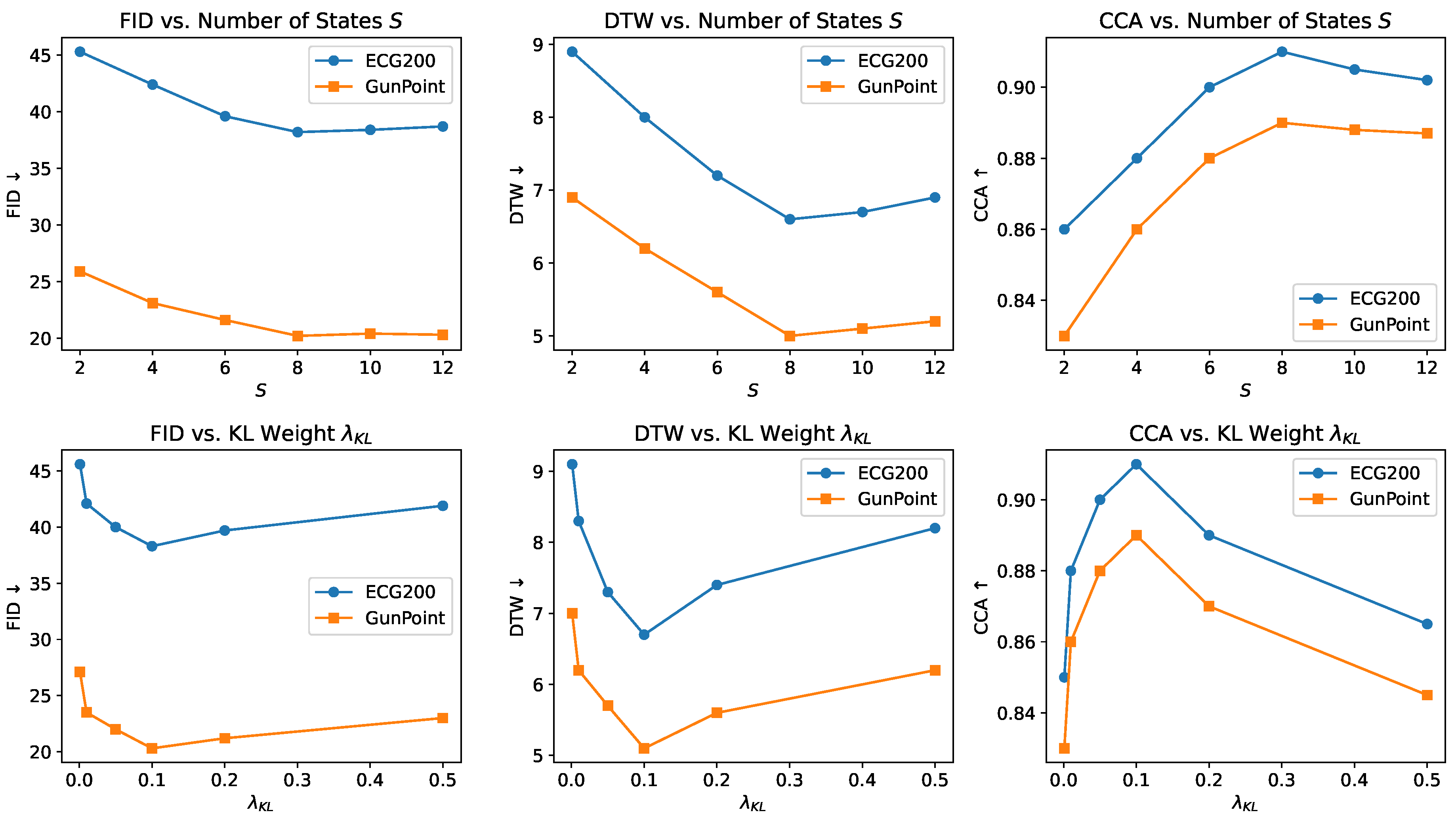

4.8. Sensitivity to Markov States and KL Regularization

To assess the robustness and parameter sensitivity of FMD-GAN, we analyze the impact of two critical hyperparameters: the number of latent Markov states S and the KL divergence weight . The regularization strength of the latent structure during diffusion and the temporal resolution of state transitions are both regulated by these parameters.

Impact of state number .Figure 6 (top) shows the generation quality under different values of

S on the ECG200 and GunPoint datasets. We observe that performance consistently improves as

S increases from 2 to 8, indicating that finer-grained state partitions help capture more detailed spectral-temporal structure. Notably, FID and DTW decrease while CCA improves with increasing

S, reaching optimal performance at

. However, further increasing

S to 10 or 12 results in saturation or slight degradation. This is probably the result of redundant over-segmentation, in which more states start modeling overlapping frequency bands, resulting in needless transitions and diminishing returns. These patterns support the idea that efficient generation requires a latent structure that is both expressive and compact.

Impact of KL regularization . As shown in

Figure 6 (bottom), the KL weight significantly affects the balance between flexibility and structural consistency. Reduced alignment and lower generation quality are the results of under-regularized transitions caused by small values (e.g.,

). On the other hand, excessively strict regularization (e.g.,

) restricts the state assignments excessively, which limits the model’s ability to adjust to semantic variation. The best FID, DTW, and CCA scores are consistently obtained with a modest setting of

across both datasets, confirming its choice as the default configuration.

To lessen stochastic variance, all outcomes are averaged across five separate runs using various seeds. The same training schedule and architecture are used to train each configuration for 5000 iterations. All primary results and ablation studies are set at and by default, unless otherwise specified.

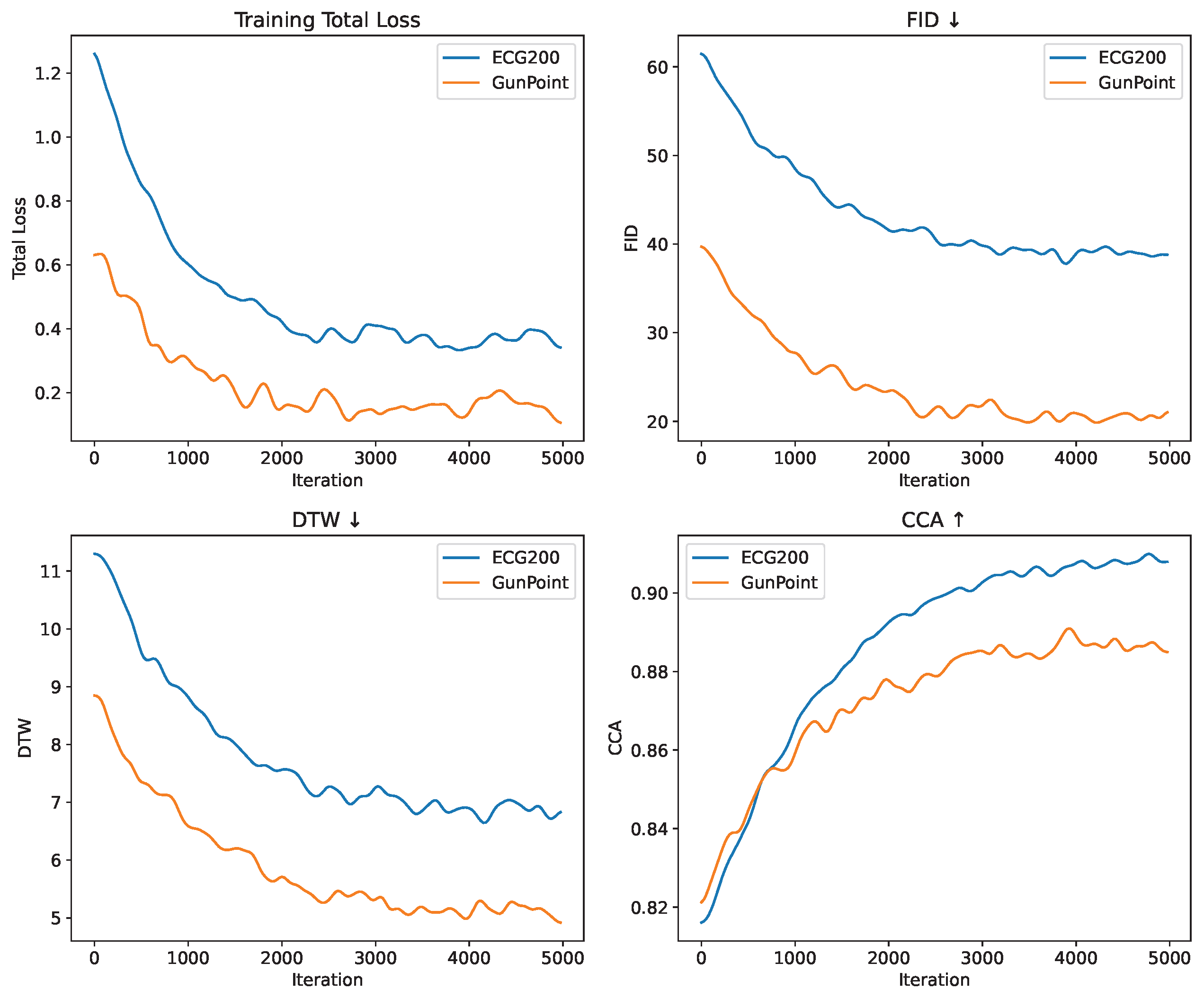

4.9. Training Dynamics and Convergence Stability

Over the course of training, we monitor four important metrics to evaluate the optimization behavior of FMD-GAN: total loss, Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), Dynamic Time Warping (DTW), and Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA). These metrics assess the latent structural consistency, temporal alignment, generation integrity, and training objective, respectively.

The evolution of these measures across 5000 training iterations on the ECG200 and GunPoint datasets is displayed in

Figure 7. Every 50 iterations, every value is recorded. For clarity, a moving average is applied after each curve has been averaged across five separate runs using various random seeds.

In both datasets, FMD-GAN exhibits steady and reliable convergence. During the first 1000 iterations, the overall loss rapidly decreases, and after 3000 iterations, it progressively plateaus. Over time, FID and DTW gradually decline, suggesting that the created sequences are more realistic and aligned. CCA rises concurrently, indicating greater structural correlation in latent space.

Because of its simpler waveform patterns and lower intra-class variability, GunPoint shows slightly smoother curves and slightly earlier stabilization in some metrics, especially FID and DTW, even though the overall trends are identical. However, about iteration 4000, both datasets converge. To account for possible late-stage enhancements and provide flexible checkpoint selection based on validation performance, training continues for up to 5000 cycles.

5. Discussion

The experimental assessment of FMD-GAN reveals that the incorporation of Fourier spectral embeddings with Markovian dynamics enhances both realism and class retention in generated time series relative to current GAN- and diffusion-based methodologies. The approach attains reduced FID and DTW scores while preserving elevated CCA alignment, signifying that the produced signals are both visually and statistically congruent with the originals and semantically aligned with the class labels.

In comparison to baseline models like TimeGAN, RCGAN-UCR, and CSDI, FMD-GAN attains a superior equilibrium between global temporal structure and local dynamics. This enhancement is due to the Fourier module’s capacity to capture frequency-domain regularities and the Markov diffusion layer’s function in enforcing sequential dependencies. The class-preserving constraint enables the model to surpass existing diffusion-based approaches (e.g., DiffWave and Diffusion-TS) in contexts where label fidelity is essential, such as medical ECG or sensor-based activity detection.

Nonetheless, certain limits exist. Initially, although Fourier–Markov coupling enhances performance, the computational expense escalates with the quantity of diffusion steps, which may restrict scalability to extensive sequences. Secondly, hyperparameter sensitivity, such as diffusion step size and Fourier truncation length, was noted, potentially impacting robustness across diverse datasets. Ultimately, while the model demonstrates effective generalization across several benchmarks, additional assessment on irregularly sampled or significantly noisy real-world time series (e.g., financial tick data, IoT streams) remains necessary.

6. Conclusions

This research presents FMD-GAN, a generative framework that combines frequency-aware diffusion, Markov-guided state transitions, and spectral clustering to generate class-consistent time series. High-fidelity sequence generation based on latent spectral states is accomplished by the model’s capacity to maintain semantic identity while encapsulating structural heterogeneity over time. The model attains exceptional or competitive outcomes across various quantitative metrics, including Spectral Distance (SD), Class Consistency Accuracy (CCA), Dynamic Time Warping (DTW), and Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), demonstrating robust alignment with real data in terms of statistical distribution and class semantics.

Ablation studies demonstrate that spectrum masking and Markovian state transitions are essential for the model’s efficacy, while sensitivity analysis underscore the consistent generation quality across various latent state quantities and KL divergence weights. Qualitative assessments, such as residual analysis, state overlays, and t-SNE visualizations, demonstrate that FMD-GAN preserves interpretable and class-discriminative latent representations, exhibiting stable convergence across datasets.

7. Future Work

Based on these findings, numerous study avenues are proposed:

Augmented architectures: Integrating transformer-based denoisers may enhance the capacity to capture long-range dependencies and intricate sequential structures, which diffusion-only models frequently inadequately address. Recent developments in time-series Transformers, including Informer [

19] and Autoformer [

35], exhibit significant promise for effective long-sequence modeling. Furthermore, adaptive or attention-based spectrum masks may allow the model to concentrate on frequencies pertinent to the job, as indicated in recent transformer-based reviews for time series [

25].

Generalization to intricate data: Future research will investigate the extension of FMD-GAN to multivariate and multimodal time series, where inter-channel interactions are essential. The production of variable-length sequences continues to pose a difficulty in generative modeling and may be enhanced by probabilistic sequence alignment methods [

27]. Semi-supervised extensions would be beneficial in areas with limited labeled data, consistent with current research on foundation models for time series [

35].

Domain-specific applications encompass anomaly production, physiological signal simulation, and specialized augmentation activities. Recent advancements in ECG creation using GANs and diffusion models [

13,

26] indicate that authentic synthetic data can enhance medical diagnosis. Likewise, probabilistic augmentation for sensor-based activity recognition has demonstrated enhancements in downstream classifier efficacy [

11].

Dynamic adaptability: Existing constraints of offline spectral clustering and fixed-length inputs may impede implementation in streaming environments. Future directions encompass dynamic mask learning and end-to-end trainable state assignment. Techniques such as score-based diffusion utilizing stochastic differential equations [

27] and adaptive embedding strategies in Transformers [

25] may inform real-time and scalable solutions. This will improve the adaptability and operational preparedness of FMD-GAN in dynamic settings, including IoT and financial tick streams.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Q. and Y.M.; Methodology, Y.M. and D.Q.; Software, Y.M.; Validation, D.Q. and Y.M.; Formal analysis, Y.M.; Resources, Y.M.; Data curation, Y.M.; Writing – original draft, D.Q.; Visualization, D.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- I. Gulrajani, F. I. Gulrajani, F. Ahmed, M. Arjovsky, V. Dumoulin, and A. Courville, Improved Training of Wasserstein GANs. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2017.

- J. B. Allen, Short term spectral analysis, synthesis, and modification by discrete Fourier transform. IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing 1977, 25, 235–238. [CrossRef]

- S. Lloyd, Least squares quantization in PCM. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1982, 28, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. R. Rabiner, A tutorial on hidden Markov models and selected applications in speech recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 1989, 77, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Perez, F. E. Perez, F. Strub, H. de Vries, V. Dumoulin, and A. Courville, FiLM: Visual reasoning with a general conditioning layer. in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), 2018.

- H. A. Dau, E. H. A. Dau, E. Keogh, K. Kamgar, C.-C. M. Yeh, Y. Zhu, S. Gharghabi, C. A. Ratanamahatana, Yanping, B. Hu, N. Begum, A. Bagnall, A. Mueen, G. Batista, and Hexagon-ML, The UCR Time Series Classification Archive. 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.cs.ucr.edu/~eamonn/time_series_data_2018/.

- J. Yoon, D. J. Yoon, D. Jarrett, and M. van der Schaar, Time-series Generative Adversarial Networks. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2019.

- O. Mogren, C-RNN-GAN: Continuous recurrent neural networks with adversarial training. in NIPS Workshop on Constructive Machine Learning, 2016.

- C. Esteban, S. L. C. Esteban, S. L. Hyland, and G. Rätsch, Real-valued (Medical) Time Series Generation with Recurrent Conditional GANs. in NeurIPS Workshop on Machine Learning for Health, 2017.

- Y. Tashiro, J. Y. Tashiro, J. Song, and S. Ermon, CSDI: Conditional Score-based Diffusion Models for Probabilistic Time Series Imputation. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2021.

- Q. Wen, J. Q. Wen, J. Gao, L. Sun, X. Xu, et al., Time-series data augmentation for deep learning: A survey. in Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), 2020.

- K. Rasul, et al., Autoregressive Denoising Diffusion Models for Multivariate Probabilistic Time Series Forecasting. in International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2021.

- E. Adib, F. E. Adib, F. Afghah, and J. J. Prevost, Synthetic ECG Signal Generation Using Generative Neural Networks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.03268. [Google Scholar]

- E. Adib, A. E. Adib, A. Fernandez, F. Afghah, and J. J. Prevost, Synthetic ECG Signal Generation using Probabilistic Diffusion Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.02475. [Google Scholar]

- X. Yuan and Y. Qiao, Diffusion-TS: Interpretable Diffusion for General Time Series Generation. in International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). arXiv, arXiv:2403.01742.

- B. Barancikova, Z. B. Barancikova, Z. Huang, and C. Salvi, SigDiffusions: Score-Based Diffusion Models for Long Time Series via Log-Signature Embeddings. arXiv, arXiv:2406.10354.

- K. Yi, Q. Zhang, S. Wang, and H. He, Neural Time Series Analysis with Fourier Transform: A Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.02173. [Google Scholar]

- X. Li, A. H. H. Ngu, and V. Metsis, TTS-CGAN: A Transformer Time-Series Conditional GAN for Biosignal Data Augmentation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.13676. [Google Scholar]

- H. Zhou, et al., Informer: Beyond Efficient Transformer for Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting. in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), 2021.

- I. Ismail, et al., DAWN: An End-to-End Differentially Private Time-series Classifier. in International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2020.

- J. Han, J. J. Han, J. Pei, and H. Tong, Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques, 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann, 2022.

- Z. Kong, W. Z. Kong, W. Ping, J. Huang, K. Zhao, and B. Catanzaro, DiffWave: A versatile diffusion model for audio synthesis. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.09761. [Google Scholar]

- L. van der Maaten and G. Hinton, Visualizing data using t-SNE. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Y. Liang, H. Y. Liang, H. Wen, Y. Nie, Y. Jiang, M. Jin, D. Song, S. Pan, and Q. Wen, Foundation Models for Time Series Analysis: A Tutorial and Survey. in Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’24), pp. 3376–3396, 2024.

- Q. Wen, T. Zhou, C. Zhang, W. Chen, Z. Ma, J. Yan, and L. Sun, Transformers in Time Series: A Survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.07125. [Google Scholar]

- Neifar, N.; Ben-Hamadou, A.; Mdhaffar, A.; Jmaiel, M. DiffECG: A Versatile Probabilistic Diffusion Model for ECG Signals Synthesis. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.01875. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2306, 01875. [Google Scholar]

- Y. Song, J. Y. Song, J. Sohl-Dickstein, D. P. Kingma, A. Kumar, S. Ermon, and B. Poole, Score-Based Generative Modeling through Stochastic Differential Equations. in International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2021.

- Y. Song and S. Ermon, Improved Techniques for Training Score-Based Generative Models. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2020.

- A. van den Oord, S. A. van den Oord, S. Dieleman, H. Zen, K. Simonyan, O. Vinyals, A. Graves, N. Kalchbrenner, A. Senior, and K. Kavukcuoglu, WaveNet: A Generative Model for Raw Audio. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.03499. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2020.

- Li, D.; Chen, D.; Jin, Y.; Shi, L.; Goh, R.S.M.; Ng, S.K. Mad-GAN: Multivariate anomaly detection for time series data with generative adversarial networks. in International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks (ICANN), pp. 703–716, 2019. Springer.

- Sohn, K.; Yan, X.; Lee, H. Learning Structured Output Representation using Deep Conditional Generative Models. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2015.

- K. Fragkiadaki, S. K. Fragkiadaki, S. Levine, P. Felsen, and J. Malik, Recurrent network models for human dynamics. in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), pp. 4346–4354, 2015.

- Lasko, T.A.; Denny, J.C.; Levy, M.A. Computational phenotype discovery using unsupervised feature learning over noisy, sparse, and irregular clinical data, PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e66341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Wu, Y. H. Wu, Y. Xu, J. Wang, G. Long, C. Jiang, and T. Zhang, Autoformer: Decomposition Transformers with Auto-Correlation for Long-Term Series Forecasting. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2021.

- Lin, L.; Li, Z.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Gao, J. Diffusion models for time-series applications: a survey. Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering 2024, 25, 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, and G. E. Hinton, ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Communications of the ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boll, S. Suppression of acoustic noise in speech using spectral subtraction. IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing 2003, 27, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

An outline of the FMD-GAN architecture. Class-aware spectral clustering is used to divide each input time series into overlapping windows and assign a latent state. A Markov chain is used to simulate temporal transitions between latent states, and each state uses a learnt spectral mask to modify the forward diffusion noise. A reverse generator recovers the denoised output conditioned on the latent state, ensuring class-consistent reconstruction. A dual-branch discriminator is used to train the model under adversarial supervision, and its generation quality and class consistency are assessed.

Figure 1.

An outline of the FMD-GAN architecture. Class-aware spectral clustering is used to divide each input time series into overlapping windows and assign a latent state. A Markov chain is used to simulate temporal transitions between latent states, and each state uses a learnt spectral mask to modify the forward diffusion noise. A reverse generator recovers the denoised output conditioned on the latent state, ensuring class-consistent reconstruction. A dual-branch discriminator is used to train the model under adversarial supervision, and its generation quality and class consistency are assessed.

Figure 2.

Overview of the class-aware state assignment pipeline. The input time series is segmented into overlapping windows . Each window is transformed via STFT to obtain the magnitude spectrogram , followed by logarithmic scaling. Spectral features are clustered via k-means to assign latent states , aligned with class labels through majority voting. A Markov transition matrix is estimated from the sequence of states. Additionally, each state’s spectral mask is computed by averaging the spectrograms of all windows assigned to that state and applying min–max normalization.

Figure 2.

Overview of the class-aware state assignment pipeline. The input time series is segmented into overlapping windows . Each window is transformed via STFT to obtain the magnitude spectrogram , followed by logarithmic scaling. Spectral features are clustered via k-means to assign latent states , aligned with class labels through majority voting. A Markov transition matrix is estimated from the sequence of states. Additionally, each state’s spectral mask is computed by averaging the spectrograms of all windows assigned to that state and applying min–max normalization.

Figure 3.

FMD-GAN’s class-aware dual-branch discriminator architecture. A segmented 1D FFT module in the spectral branch and a Conv1D network in the temporal branch process the reconstructed sequence . The input is first split into non-overlapping windows of length 256 by the spectral branch, which then performs FFT to each segment and aggregates the magnitude spectra of each. A final discriminator score reflecting frequency-domain coherence and temporal continuity is generated by concatenating and projecting features from both branches.

Figure 3.

FMD-GAN’s class-aware dual-branch discriminator architecture. A segmented 1D FFT module in the spectral branch and a Conv1D network in the temporal branch process the reconstructed sequence . The input is first split into non-overlapping windows of length 256 by the spectral branch, which then performs FFT to each segment and aggregates the magnitude spectra of each. A final discriminator score reflecting frequency-domain coherence and temporal continuity is generated by concatenating and projecting features from both branches.

Figure 4.

Qualitative analysis of the ECG200 and GunPoint datasets. Each column presents a class-specific sample, featuring the actual sequence (top) alongside results from TimeGAN, Diffusion-TS, and FMD-GAN. Residual errors and latent Markov states are depicted solely for FMD-GAN, as these elements are inapplicable to the baseline models.

Figure 4.

Qualitative analysis of the ECG200 and GunPoint datasets. Each column presents a class-specific sample, featuring the actual sequence (top) alongside results from TimeGAN, Diffusion-TS, and FMD-GAN. Residual errors and latent Markov states are depicted solely for FMD-GAN, as these elements are inapplicable to the baseline models.

Figure 5.

Latent space visualization via t-SNE on ECG200 (top row) and GunPoint (bottom row). Real test samples (circles) and produced sequences (triangles) are compared in each subfigure using the following models: TimeGAN (left), Diffusion-TS (middle), and FMD-GAN (right). Class labels are used to color-code points. Class-aware and semantically consistent generation is demonstrated by FMD-GAN, which exhibits superior alignment between generated and real distributions.

Figure 5.

Latent space visualization via t-SNE on ECG200 (top row) and GunPoint (bottom row). Real test samples (circles) and produced sequences (triangles) are compared in each subfigure using the following models: TimeGAN (left), Diffusion-TS (middle), and FMD-GAN (right). Class labels are used to color-code points. Class-aware and semantically consistent generation is demonstrated by FMD-GAN, which exhibits superior alignment between generated and real distributions.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis of FMD-GAN on ECG200 and GunPoint. Top row: Performance under varying number of latent Markov states S. Bottom row: Performance under different KL weights . Metrics include FID (↓), DTW (↓), and CCA (↑), all averaged over 5 runs. Optimal results are achieved near and , confirming the robustness and generalizability of the model.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis of FMD-GAN on ECG200 and GunPoint. Top row: Performance under varying number of latent Markov states S. Bottom row: Performance under different KL weights . Metrics include FID (↓), DTW (↓), and CCA (↑), all averaged over 5 runs. Optimal results are achieved near and , confirming the robustness and generalizability of the model.

Figure 7.

Training dynamics and convergence analysis. Dynamic Time Warping (DTW), Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA), Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), and total loss evolution during training on the ECG200 and GunPoint. Every curve has been averaged and smoothed across five runs. All measures show steady convergence for FMD-GAN, with performance stabilizing at iteration 4000.

Figure 7.

Training dynamics and convergence analysis. Dynamic Time Warping (DTW), Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA), Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), and total loss evolution during training on the ECG200 and GunPoint. Every curve has been averaged and smoothed across five runs. All measures show steady convergence for FMD-GAN, with performance stabilizing at iteration 4000.

Table 1.

Summary of datasets used for evaluation.

Table 1.

Summary of datasets used for evaluation.

| Dataset |

#Classes |

Length |

#Instances |

Domain |

| ECG200 |

2 |

96 |

200 |

Biomedical |

| GunPoint |

2 |

150 |

200 |

Human motion |

| UWaveGestureLibrary_X |

8 |

315 |

896 |

Multivariate gesture |

| FordA |

2 |

500 |

1320 |

Industrial sensor |

Table 2.

Quantitative comparison using FID (↓), DTW (↓), and CCA (↑) across four datasets. Values are averaged over five random seeds. Best scores per column are bolded.

Table 2.

Quantitative comparison using FID (↓), DTW (↓), and CCA (↑) across four datasets. Values are averaged over five random seeds. Best scores per column are bolded.

| Model |

ECG200 |

GunPoint |

FordA |

ChlorineConc |

| |

FID ↓ |

DTW ↓ |

CCA ↑ |

FID ↓ |

DTW ↓ |

CCA ↑ |

FID ↓ |

DTW ↓ |

CCA ↑ |

FID ↓ |

DTW ↓ |

CCA ↑ |

| TimeGAN |

50.9 |

11.6 |

0.90 |

47.9 |

6.4 |

0.87 |

50.4 |

16.8 |

0.77 |

38.0 |

10.6 |

0.89 |

| RCGAN-UCR |

45.8 |

17.3 |

0.84 |

29.1 |

13.3 |

0.76 |

53.1 |

14.5 |

0.88 |

34.2 |

19.6 |

0.88 |

| TTS-CGAN |

51.1 |

7.9 |

0.84 |

21.8 |

7.3 |

0.84 |

49.8 |

19.5 |

0.81 |

34.8 |

12.0 |

0.79 |

| CSDI |

48.5 |

9.8 |

0.88 |

25.3 |

6.7 |

0.85 |

47.6 |

13.2 |

0.86 |

33.6 |

9.7 |

0.87 |

| DiffWave |

42.7 |

6.7 |

0.90 |

22.4 |

5.9 |

0.88 |

45.3 |

10.2 |

0.88 |

31.2 |

8.3 |

0.90 |

| Diffusion-TS |

38.2 |

7.2 |

0.91 |

20.7 |

5.2 |

0.89 |

43.9 |

9.9 |

0.89 |

28.9 |

7.3 |

0.89 |

| FMD-GAN (Ours) |

38.4 |

6.7 |

0.91 |

20.1 |

5.1 |

0.89 |

41.8 |

9.6 |

0.89 |

28.5 |

7.1 |

0.88 |

Table 3.

Spectral Distance (SD ↓) comparison across four datasets.

Table 3.

Spectral Distance (SD ↓) comparison across four datasets.

| Model |

ECG200 |

GunPoint |

Coffee |

Beef |

| TTS-CGAN |

0.092 |

0.084 |

0.113 |

0.105 |

| CSDI |

0.081 |

0.075 |

0.109 |

0.093 |

| DiffWave |

0.064 |

0.058 |

0.091 |

0.078 |

| Diffusion-TS |

0.062 |

0.055 |

0.087 |

0.072 |

| FMD-GAN (Ours) |

0.053 |

0.046 |

0.079 |

0.065 |

Table 4.

Ablation study on ECG200 and GunPoint datasets using FID (↓), DTW (↓), CCA (↑), and SD (↓). Lower SD indicates better spectral structure preservation. All results are averaged over 5 random seeds.

Table 4.

Ablation study on ECG200 and GunPoint datasets using FID (↓), DTW (↓), CCA (↑), and SD (↓). Lower SD indicates better spectral structure preservation. All results are averaged over 5 random seeds.

| |

ECG200 |

GunPoint |

| Variant |

FID ↓ |

DTW ↓ |

CCA ↑ |

SD ↓ |

FID ↓ |

DTW ↓ |

CCA ↑ |

SD ↓ |

| NoMask |

43.7 |

8.5 |

0.86 |

0.074 |

23.9 |

6.1 |

0.85 |

0.067 |

| NoMarkov |

41.5 |

8.2 |

0.88 |

0.069 |

22.4 |

5.8 |

0.86 |

0.063 |

| NoDiff |

46.2 |

9.1 |

0.83 |

0.089 |

26.1 |

6.6 |

0.82 |

0.079 |

| FMD-GAN (Full) |

38.4 |

6.7 |

0.91 |

0.053 |

20.1 |

5.1 |

0.89 |

0.046 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).