1. Introduction

Work-related eye injuries are a significant public health concern worldwide, leading to vision loss [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Among these injuries, corneal foreign bodies (CFBs) are among the most commonly observed types of ocular trauma [

6]. CFB injuries can lead to workforce loss and permanent visual impairment. Eye injuries involving foreign bodies are frequently seen among workers in the construction and metal industries [

7]. Corneal foreign bodies, which account for 30.8% of all ocular traumas, represent the second most common type of eye injury [

8]. In developing countries, CFBs are the most frequently observed type of eye trauma [

9,

10]. They typically affect the superficial cornea; however, in cases of penetration or deeper injuries, they increase the risk of scarring and consequently, visual impairment [

11,

12,

13].

Although such injuries are often preventable with the use of protective eyewear, the use and demand for such protective equipment remain uncommon [

14,

15]. It has been reported that these types of injuries impose a significant economic burden through healthcare costs [

16]. Even in developed countries such as the United States and Canada, between 700–2000 workers present to emergency departments due to occupational eye injuries, leading to loss of work productivity [

17,

18]. Although more than three-quarters of these injuries could be prevented with personal protective equipment (PPE), significant problems persist regarding the availability and use of such gear [12.19].

Despite significant deficiencies in the implementation of preventive measures against CFB injuries, substantial issues are also reported in their management, with increasing rates of complications. Delayed presentation and access to healthcare services have emerged as important problems in addressing this issue. Studies have reported that such delays and access issues are more prevalent among those living and working in rural areas, those with lower socioeconomic status, and those who have not received occupational health and safety training [

15,

20]. Individual factors are also reported to contribute to delays in treatment, with some workers underestimating the injury and symptoms, and even attempting self-removal of the foreign body. Literature reports that treatment delays and unqualified interventions are often followed by complications such as rust ring formation, infectious keratitis, and prolonged healing periods [

20,

21,

22].

Considering the importance of this issue, identifying the extent of the problem on a regional level by determining the prevalence of delayed treatment, improper initial intervention, and lack of PPE use, as well as identifying contributing factors and setting priorities, is essential to enable necessary interventions.

This study aims to identify the factors affecting delayed treatment, improper initial intervention, and use of PPE in corneal foreign body (CFB) injuries occurring as occupational accidents.

2. Material Method

The present study has a cross-sectional design. It was conducted between September 2024 and February 2025 at the Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medicine, xxx. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the xxx (as required by journal rules)and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.Patients who presented to the Ophthalmology Clinic of Harran University Faculty of Medicine Hospital with work-related corneal foreign body injuries were included in the study. All patients who presented during the specified dates were included in the study. With the assumption that the independent variables of the study would have an effect size of 0.4 on the dependent variables, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be 81 in a calculation conducted at a 95.0% confidence level and 80.0% power. However, a total of 92 people were included in the study. Twenty-eight people were not included in the study because they refused to participate. Ethical approval was obtained from xxx Clinical Research Ethics Committee on xxx, with the number x(as required by journal rules), and informed consent was obtained from patients prior to the study. The inclusion criteria for the study were: having a corneal foreign body injury, being 18 years of age or older, having been injured during work-related activities, and voluntarily agreeing to participate in the study. The study data was collected by using a structured survey consisting of 20 questions. The survey consists of sections on socio-demographic characteristics, characteristics related to the work performed, and characteristics related to the injury. It took approximately 10 minutes for participants to complete the survey. Questions in the section on characteristics related to the injury, which included clinical assessment, were completed by the physician who performed the examination.

Dependent variables in the study were treatment delay, failure to use personal protective equipment (PPE), and inappropriate non-medical intervention.

Independent variables of the study were: Socio-demographic variables: age, gender, educational status, social security status; variables related to the work performed: job category, position at the workplace, professional status, status of receiving job-related training, status of receiving job-related courses/certificates, length of service in the job category, status of receiving compliance training from the occupational health and safety unit, and status of receiving occupational health and safety services; variables related to injury: content of the foreign body, previous exposure to foreign bodies within the last year, chronic eye disease status, ocular location of the foreign body, and the eye in which the foreign body is located.

Definitions

Substances such as metal, sand, gravel, wood, glass, and plant material that can penetrate the cornea and occur in the workplace or during the course of work are defined as foreign bodies. Personal protective equipment refers to devices, tools, or materials used to protect the face and head, such as helmets, face shields, and protective eyewear. Referrals made to a healthcare facility more than 4 hours after an injury are considered treatment delays. Interventions performed by individuals who have not received special training in this area, such as healthcare professionals, or attempts by individuals to use topical anaesthetics or remove foreign bodies themselves, were considered inappropriate initial interventions. The fact that patients with mild symptoms or whose symptoms improved with their own interventions did not go to the hospital, and that the clinic where the study was conducted was located outside the city centre and was difficult to reach may have caused a bias in patient selection. Furthermore, the inability to verify data based on participant statements is one of the limitations of the present study in terms of information bias. The data were evaluated by using descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, maximum, or percentage. Hypothesis testing was performed using the chi-square test for categorical data and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data. Analyses were conducted by using the SPSS 26.0 software.

3. Results

A total of 92 participants were reached in the study. The mean age of the participants was 36.04±12.24, and the mean length of service at their current workplace was 11.86±10.98 years. All participants were male. It was found that 16.3% of the participants had an education level below primary school and 58.7% had social security (

Table 2).

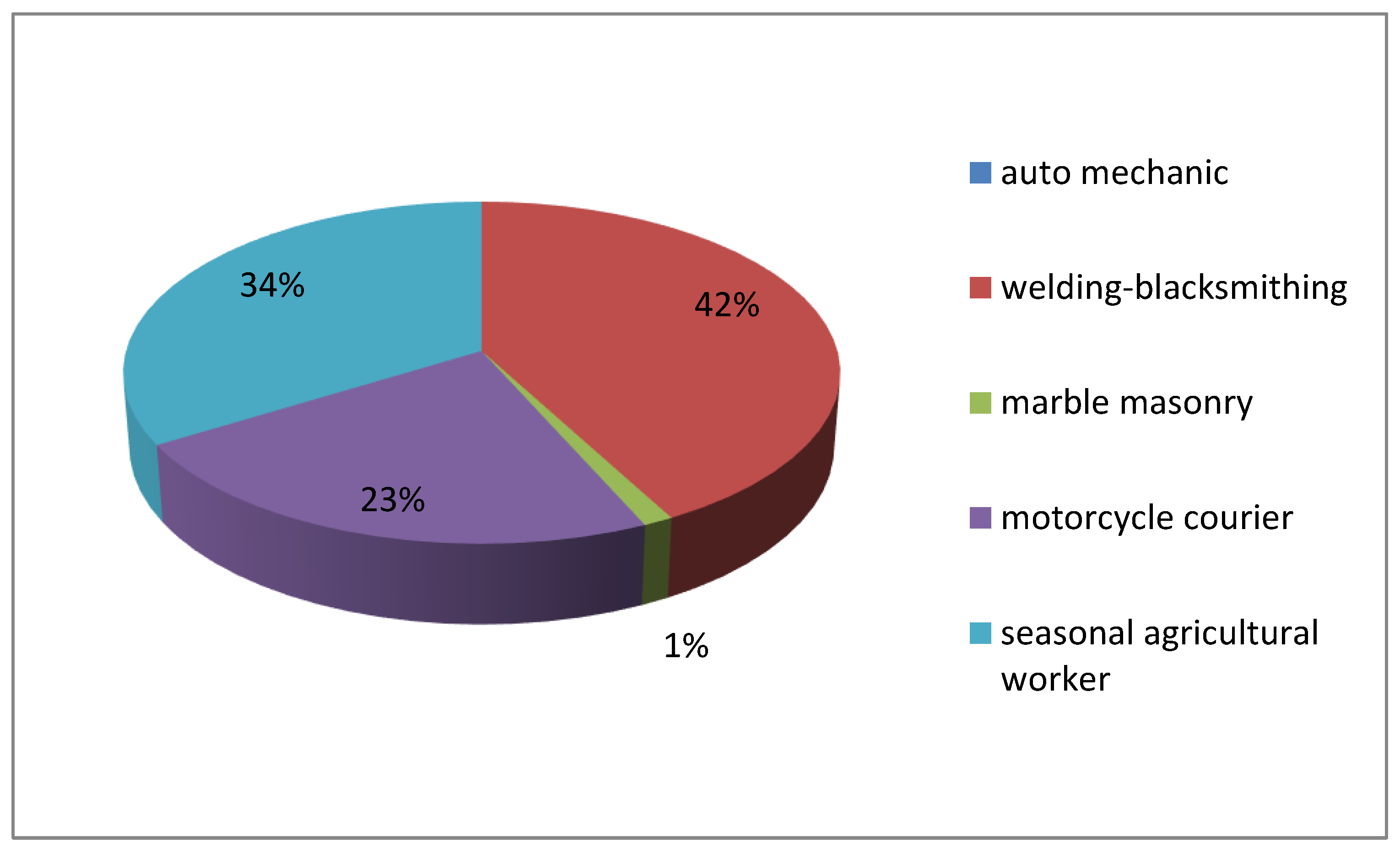

When work-related characteristics were examined, it was found that 38% worked in the welding/blacksmithing sector (

Figure 1), 29.3% were business owners, 68.5% were master craftsmen, 55.4% had not received any vocational training, 81.5% had not participated in any courses or certification programs related to their work, 71.7% had not received any occupational health and safety (OHS) training or on-the-job training from any OHS unit, and 70.7% had not received any OHS services (

Table 3).

When the characteristics of injuries were examined, it was found that 87% of foreign bodies causing injury were metal, 32.6% had been exposed to foreign bodies within the last year, 6.5% had a chronic eye disease, and 51.1% had right eye injuries (

Table 4).

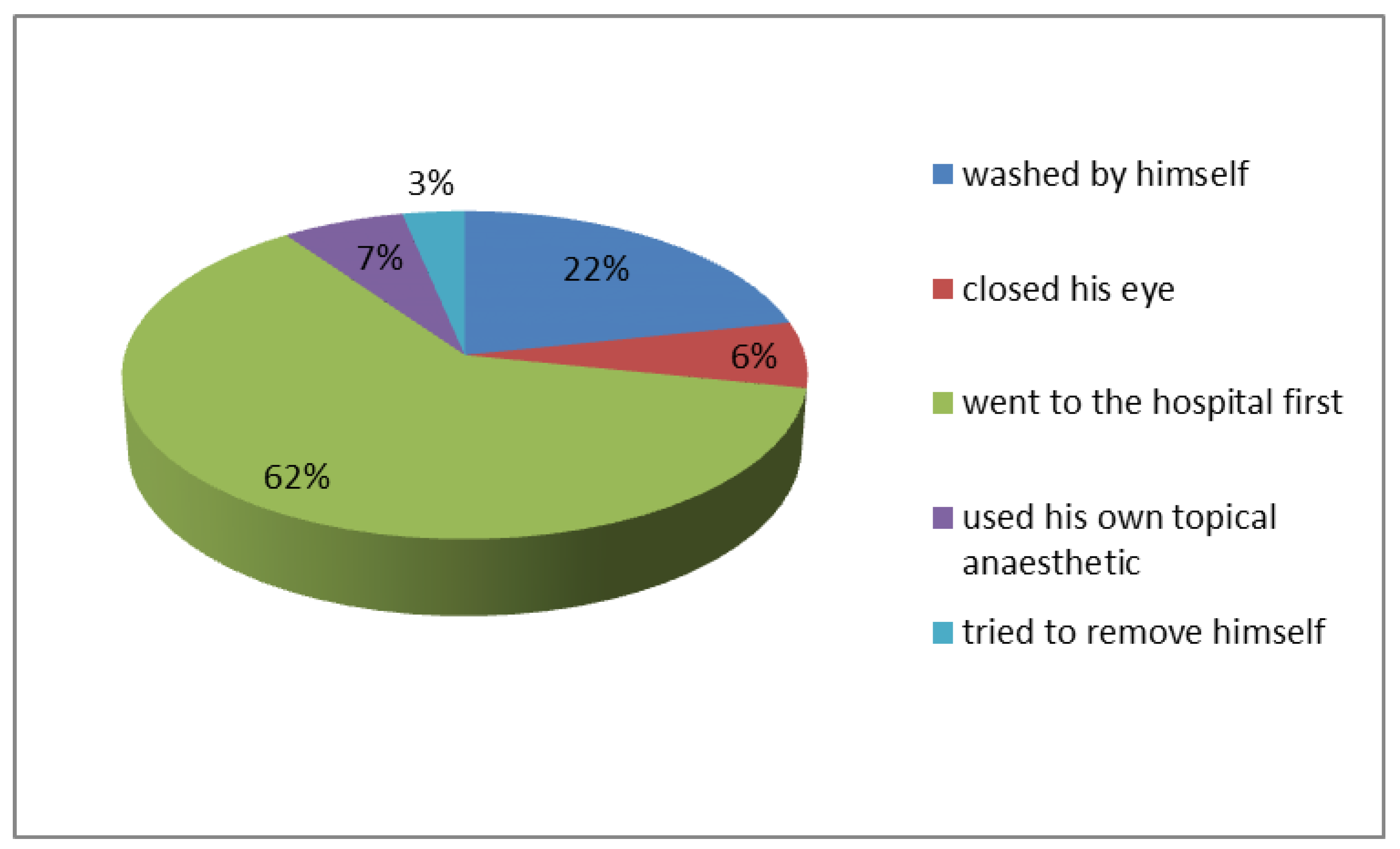

It was found that 46.7% of participants did not consistently use PPE, 75% experienced treatment delays, and 9.8% self-performed incorrect first intervention (

Table 2). It was also found that the most common reason for not using PPE was forgetting to wear it (31.5%), while the most common incorrect first interventions after trauma were self-administering topical anaesthetics (6.5%) and attempting to remove the injury themselves (3.3%) (

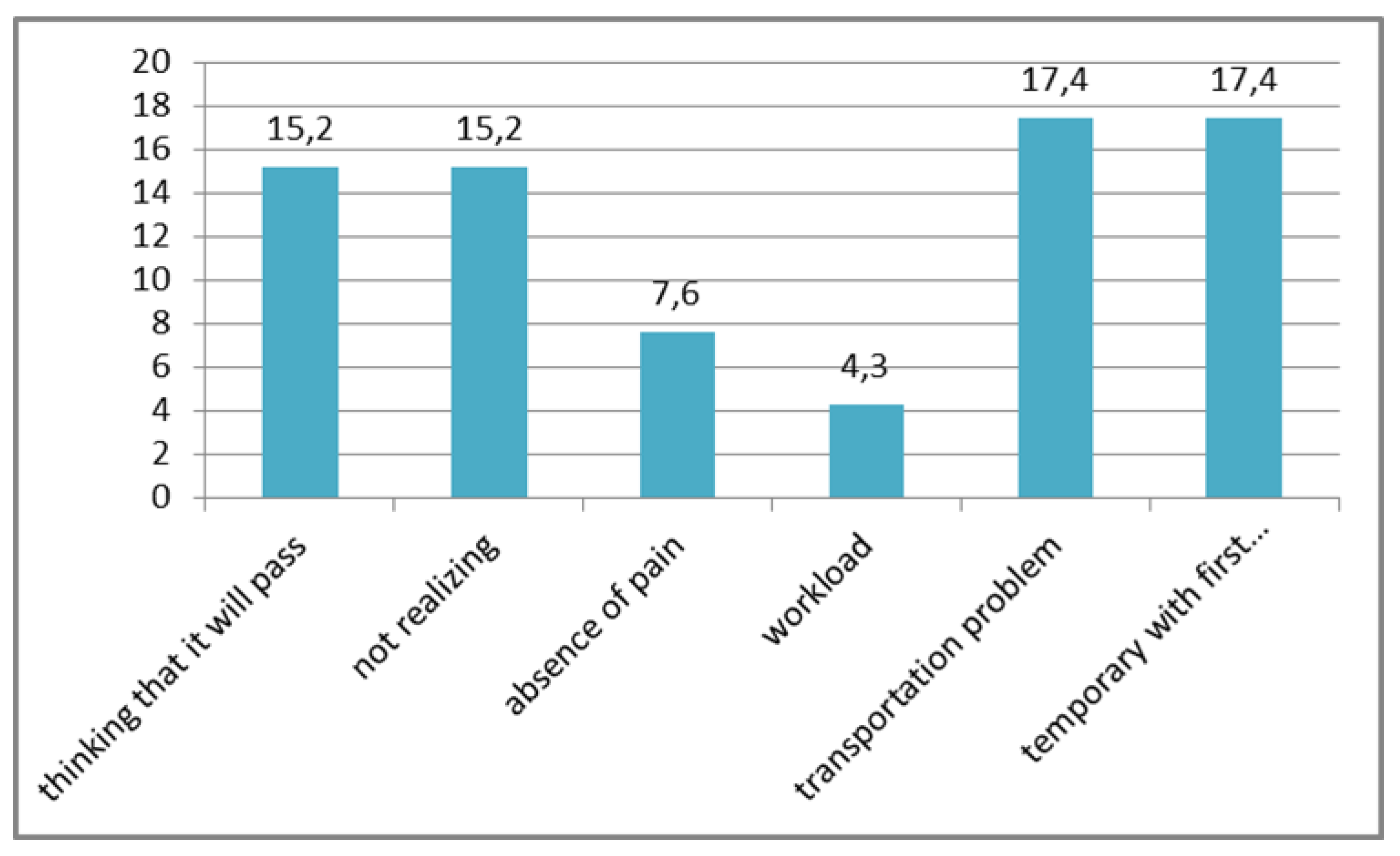

Figure 2). The most common reasons for delayed treatment were temporary relief after initial intervention (17.4%) and transportation problems (17.4%) (

Figure 3).

When the effect of socio-demographic characteristics was examined, the mean age of participants who performed the first intervention correctly was 35.28±11.80, while the mean age of participants who performed it incorrectly was 46.78±9.92. This difference was statistically significant (p<0.05). However, it was found that age did not have an effect on not using PPE and treatment delay (

Table 1). It was also found that social security status, educational status, and length of employment did not have an effect on not using PPE, treatment delay, and correct initial intervention (

Table 1,

Table 2).

When the effects of job-related characteristics were examined, it was found that treatment delays among workers in the auto repair sector were lower than among workers in other sectors (p<0.05). However, it was found that the sector in which the worker was employed had no effect on treatment delays or on whether first aid was administered correctly. It was found that workers who did not receive occupational safety and health services were less likely to use PPE constantly than workers who did receive such services (p<0.05). In addition, it was found that receiving OHS services did not have an effect on treatment delays or the correctness of first aid. Workplace location, occupational status, vocational training, participation in courses/certification programmes, and receiving orientation training/in-service training were not found to have a significant effect on not using PPE, treatment delays, or the correctness of the first intervention (

Table 3).

When the effects of injury-related characteristics were examined, no effect was found on not using PPE, treatment delay, or the correctness of initial intervention in relation to foreign body content, foreign body exposure in the last year, chronic eye disease, and which side of the eye was injured (

Table 4).

Table 1.

The relationship between age and length of service and dependent variables.

Table 1.

The relationship between age and length of service and dependent variables.

| |

Age |

Length of service |

| |

Mean±standard deviation |

Median (Min-max) |

Mean±standard deviation |

Median (Min-max) |

| The status of not using PPE |

|

| Constantly |

36.52± 12.76 |

34.50(17-66) |

11,57±11,47 |

9,50(0-45) |

| Temporarily |

36.35±11.59 |

37(15-58) |

12,10±10,65 |

10(1-40) |

| |

MWU=1029.000 p=0.848 |

MWU=930.000 p=0.527 |

| Treatment delay |

|

| Yes |

36.70±13.33 |

32(17-62) |

15,00±13,36 |

12(1-40) |

| No |

36.34±11.73 |

36(15-66) |

10,78±9,92 |

9(0-45) |

| |

MWU=775.500 p=0.871 |

MWU=654.500 p=0.281 |

| The status of performing the initial intervention correctly |

|

| Yes |

35.28±11.80 |

34(15-66) |

11,63±10,52 |

10(1-40) |

| No |

46.78±9.92 |

45(35-61) |

13,89±15,12 |

10(0-45) |

| |

MWU=165.000 p=0.006 |

MWU=364.000 p=0.995 |

Table 2.

The effect of sociodemographic variables on dependent variables.

Table 2.

The effect of sociodemographic variables on dependent variables.

| |

The status of not using PPE |

Treatment delay |

The status of performing the initial intervention correctly |

|

| |

Constantly |

Temporarily |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

| |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

%** |

| The status of having social security |

| Yes |

21 |

38.9 |

33 |

61.1 |

13 |

24.1 |

41 |

75.9 |

49 |

90.7 |

5 |

9.3 |

58.7 |

| No |

22 |

57.9 |

16 |

42.1 |

10 |

26.3 |

28 |

73.7 |

34 |

89.5 |

4 |

10.5 |

42.3 |

| |

Chi-square =2.518 p=0.113 |

Chi-square =0.000 p=1.00 |

Chi-square =0.000 p=1.00 |

| Educational status |

| Below primary education |

8 |

53.3 |

7 |

46.7 |

2 |

13.3 |

13 |

86.7 |

12 |

80.0 |

3 |

20.0 |

16.3 |

| Primary education and above |

35 |

45.5 |

42 |

54.5 |

21 |

27.3 |

56 |

72.7 |

71 |

92.2 |

6 |

7.8 |

83.7 |

| |

Chi-square =0.77 p=0.782 |

p=0.341$ |

p=0.160$

|

| Total |

43 |

46.7 |

49 |

53.3 |

23 |

25.0 |

69 |

75.0 |

83 |

90.2 |

9 |

9.8 |

|

Table 3.

The effect of characteristics related to the work performed on dependent variables.

Table 3.

The effect of characteristics related to the work performed on dependent variables.

| |

The status of not using PPE |

Treatment delay |

The status of performing the initial intervention correctly |

|

| |

Constantly |

Temporarily |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

| |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

%** |

| Field of work |

|

| Auto Mechanics |

3 |

33.3 |

6 |

66.7 |

6 |

66.7 |

3 |

33.3 |

8 |

88.9 |

1 |

11.1 |

9.8 |

Welding/

Blacksmithing |

13 |

37.1 |

22 |

62.9 |

6 |

17.1 |

29 |

82.9 |

32 |

91.4 |

3 |

8.6 |

38.0 |

MTİ/

Marble crafting |

17 |

58.6 |

12 |

41.4 |

6 |

20.7 |

23 |

79.3 |

25 |

86.2 |

4 |

13.8 |

31.5 |

| Motorcycle courier |

10 |

52.6 |

9 |

47.4 |

5 |

26.3 |

14 |

73.7 |

18 |

94.7 |

1 |

5.3 |

20.7 |

| |

Chi-square =3.854 p=0.278 |

Chi-square =9.791 p=0.020 |

Chi-square =1.044 p=0.791 |

|

| Position at work |

|

| Employer |

14 |

51.9 |

13 |

48.1 |

9 |

33.3 |

18 |

66.7 |

23 |

85.2 |

4 |

14.8 |

29.3 |

| Employee |

29 |

44.6 |

36 |

55.4 |

14 |

21.5 |

51 |

78.5 |

60 |

92.3 |

5 |

7.7 |

70.7 |

| |

Chi-square =0.163 p=0.686 |

Chi-square =0.856 p=0.355 |

Chi-square = $ p=0.441 |

|

| Occupational status |

|

|

|

|

| Craftsman |

28 |

44.4 |

35 |

55.6 |

16 |

25.4 |

47 |

74.6 |

56 |

88.9 |

7 |

11.1 |

68.5 |

| Foreman |

6 |

60.0 |

4 |

40.0 |

2 |

20.0 |

8 |

80.0 |

9 |

90.0 |

1 |

10.0 |

10.9 |

| Apprentice |

9 |

47.4 |

10 |

52.6 |

5 |

26.3 |

14 |

73.7 |

18 |

94.7 |

1 |

5.3 |

20.7 |

| |

Chi-square =0.843 p=0.656 |

Chi-square =0.156 p=0.925 |

Chi-square =0.566 p=0.753 |

|

| Vocational training |

|

|

|

|

| No training |

27 |

52.9 |

24 |

47.1 |

13 |

25.5 |

38 |

74.5 |

45 |

88.2 |

6 |

11.8 |

55.4 |

Apprenticeship/

Technical high school |

16 |

39.0 |

25 |

61.0 |

10 |

24.4 |

31 |

75.6 |

38 |

92.7 |

3 |

7.3 |

44.6 |

| |

Chi-square =1.253 p=0.263 |

Chi-square =0.00 p=1.00 |

$ p=0.726 |

|

| Participation in course/certificate program |

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

6 |

35.3 |

11 |

64.7 |

4 |

23.5 |

13 |

76.5 |

17 |

100.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

18.5 |

| No |

37 |

49.3 |

38 |

50.7 |

19 |

25.3 |

56 |

74.7 |

66 |

88.0 |

9 |

12.0 |

81.5 |

| |

Chi-square =0.606 p=0.436 |

$ p=1.00 |

$ p=0.202 |

|

| The status of having received orientation training/in-service training |

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

10 |

38.5 |

16 |

61.5 |

4 |

15.4 |

22 |

84.6 |

25 |

96.2 |

1 |

3.8 |

28.3 |

| No |

33 |

50.0 |

33 |

50.0 |

19 |

28.8 |

47 |

71.2 |

58 |

87.9 |

8 |

12.1 |

71.7 |

| |

Chi-square =0.588 p=0.443 |

Chi-square =1.144 p=0.285 |

$ p=0.437 |

|

| The status of having received OHS service |

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

35 |

53.8 |

30 |

46.2 |

15 |

23.1 |

50 |

76.9 |

57 |

87.7 |

8 |

12.3 |

70.7 |

| No |

8 |

29.6 |

19 |

70.4 |

8 |

29.6 |

19 |

70.4 |

26 |

96.3 |

1 |

3.7 |

29.3 |

| |

Chi-square =4.494 p=0.034 |

Chi-square =0.157 p=0.692 |

$ p=0.274 |

|

Table 4.

The effects of other injury-related characteristics on dependent variables.

Table 4.

The effects of other injury-related characteristics on dependent variables.

| |

The status of not using PPE |

Treatment delay |

The status of performing the initial intervention correctly |

|

| |

Constantly |

Temporarily |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

| |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

n |

%* |

%** |

| Content of foreign body |

|

| Metal |

35 |

43.8 |

45 |

56.3 |

20 |

25.0 |

60 |

75.0 |

72 |

90.0 |

8 |

10.0 |

87.0 |

| Gravel/stone/sand |

4 |

50 |

4 |

50 |

2 |

25.0 |

6 |

75.0 |

8 |

100.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

8.7 |

| Wood/plant pieces |

4 |

100 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

25.0 |

3 |

75.0 |

3 |

75.0 |

1 |

25.0 |

4.3 |

| |

Chi-square 4.879 p=0.087 |

Chi-square =0.00 p=1.00 |

Chi-square =1.921 p=0.383 |

|

| Exposure to foreign body within the last year |

|

| Yes |

11 |

36.7 |

19 |

63.3 |

9 |

30.0 |

21 |

70.0 |

28 |

93.3 |

2 |

6.7 |

32.6 |

| No |

32 |

51.6 |

30 |

48.4 |

14 |

22.6 |

48 |

77.4 |

55 |

88.7 |

7 |

11.3 |

67.4 |

| |

Chi-square =1.264 p=0.261 |

Chi-square =0.264 p=0.608 |

$ p=0.713 |

|

| Chronic disease in the eye |

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

4 |

66.7 |

2 |

33.3 |

3 |

50.0 |

3 |

50.0 |

5 |

83.3 |

1 |

16.7 |

6.5 |

| No |

39 |

45.3 |

47 |

54.7 |

20 |

23.3 |

66 |

76.7 |

78 |

90.7 |

8 |

9.3 |

93.5 |

| |

$ p=0.413 |

$ p=0.163 |

$ p=0.471 |

|

| The side of the eye that was injured |

|

|

|

|

| Right |

25 |

53.2 |

22 |

46.8 |

14 |

29.8 |

33 |

70.2 |

43 |

91.5 |

4 |

8.5 |

51.1 |

| Left |

18 |

40.0 |

27 |

60.0 |

9 |

20.0 |

36 |

80.0 |

40 |

88.9 |

5 |

11.1 |

48.9 |

| |

Chi-square =1.121 p=0.290 |

Chi-square =0.710 p=0.399 |

$ p=0.737 |

|

4. Discussion

The majority of the study participants were male, had completed only primary education, and were employed in heavy labor sectors. These findings are consistent with previous studies [

23,

24]. The most frequently reported occupation was metalworking, and consistent with other studies, the most common type of foreign body was metallic [

19,

25,

26,

27]. Metal cutting has been identified as the activity most commonly associated with eye injuries [

28]. Due to the characteristics of the study area, CFB injuries were also frequently observed among agricultural workers. An operational study conducted in Şanlıurfa similarly emphasized the importance of providing agricultural workers with health services that encompass safe living environments, improved hygiene, personal protective equipment (PPE), and workplace accident prevention [

29,

30].

Early intervention in foreign body-related eye injuries is crucial to facilitate rapid healing and prevent complications. Delayed or incorrect interventions can prolong recovery and increase the risk of complications such as infection and corneal scarring [

15,

16]. In this study, the treatment delay rate was found to be relatively high at 75.0%. Although studies investigating treatment-seeking times are limited, it has generally been reported that 47.5% to 65% of patients present within the first 24 hours. The higher rate of delay in the present study may be attributed to the stricter threshold used to define treatment delay—specifically, a 4-hour cutoff—compared to previous studies [

15,

25,

26].

Treatment delays were less frequent among auto-repair workers compared to other occupational groups. This could be due to their closer proximity to healthcare services. In contrast, sectors such as agriculture and metalworking are typically conducted in rural or peri-urban areas, which can significantly delay access to medical care. Furthermore, the lower exposure to CFBs and potentially less severe injuries in these groups may contribute to their relatively prompt treatment-seeking behavior.

It is concerning that 38.0% of patients attempted initial intervention without professional healthcare assistance. While eye washing and covering the eye are acceptable initial responses, the use of topical anesthetics or attempts to remove the foreign body independently can exacerbate corneal damage, prolong recovery, and result in complications such as corneal ulcers or permanent vision loss [

31,

32,

33].

More than half of the participants (55.4%) had no formal vocational education, and 81.5% had not attended any job-related courses or certification programs. Furthermore, 71.7% had not received any orientation or in-service training from an occupational health and safety (OHS) unit, and 70.7% had not received any form of OHS service. These findings reveal significant deficiencies in access to professional training and occupational health services.

Although none of the participants consistently used PPE, 46.7% reported that they either did not prefer to use it regularly or did not have access to the necessary equipment. This indicates an ongoing risk for CFB injuries as long as these occupational activities persist. A field study conducted in 2020 with 500 workers showed that the incidence of eye injuries was 12.5% higher among those who did not use PPE compared to those who did [

34]. Zakrzewski et al. also found that although 74.1% of welders had eye protection, 66.9% were not wearing it at the time of injury [

35]. Similarly, Agrawal et al. reported that 86% of patients were not wearing eye protection at the time of injury. The lower rates observed in this study may be associated with the longer occupational experience of the participants [

25].

The relatively low prevalence of improper initial interventions may be linked to the fact that most participants had completed at least primary education. While receiving OHS services and participating in vocational training programs are expected to increase PPE use, no significant differences were found in treatment delay or PPE usage between those who received such services and those who did not. This may suggest that the content and scope of OHS education are inadequate. The high percentage of participants (32%) who reported experiencing a similar injury in the past year supports this interpretation. Moreover, despite 68.5% of participants identifying as skilled workers, the majority lacked formal vocational training and had not attended certification or job-related training programs—factors that may contribute to recurrent occupational accidents.

A prior study indicated that while receiving OHS services positively influenced PPE compliance, it had no significant impact on reducing treatment delays or improving the accuracy of first-aid interventions [

31]. The same study emphasized that although OHS education improves PPE adherence, it often does not address post-injury management. Furthermore, PPE alone is insufficient to prevent all workplace injuries and must be complemented by training and risk assessment strategies [

36]. In our study, continuous non-use of PPE was more common among those who did not receive OHS services. A 2021 study found that occupational safety specialists provided proper PPE training in 79.7% of the workplaces they served, while 20.3% did not provide such education [

35,

36]. These findings emphasize the critical role of comprehensive OHS services and training in workplace safety.

Nonetheless, the overall low PPE usage rates—especially the lack of habitual eye protection among workers—remain a significant barrier to preventing ocular injuries.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS A significant proportion of the study population is uneducated and lacks social security. Metalworking and agricultural sectors represent high-risk occupations for CFB injuries. Inappropriate initial interventions were more common among older workers. Continuous PPE use was more prevalent among those who received OHS services. All workers should be ensured access to qualified occupational health and safety services. Within these services, high-risk groups—such as metalworkers, agricultural laborers, older workers, and those with low educational attainment—should be prioritized in both occupational health training and vocational education to mitigate their vulnerability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplemental Digital Content 1 – STROBE Checklist.

Author Contributions

Funda Yüksekyayla worked on all stages of the study, including design, data collection, statistical analysis, and manuscript writing. İbrahim Koruk contributed to epidemiological design, statistical interpretation, and literature review. Ali Hakim Reyhan provided clinical data and contributed to interpretation of results. Çağrı Mutaf assisted with clinical evaluation and data verification. İrfan Uzun ensured data accuracy and contributed to patient evaluations. Esma Büşra Bayramoğlu conducted surveys and managed data entry. Nurullah Demir conducted surveys and managed data entry.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for taking the time to participate in this study.

Ethical Considerations & Disclosure(s)

Ethical approval was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Harran Univercity session number 12 dated 26.08.2024.

STROBE Compliance Statement

This study complies with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) reporting guidelines. The completed checklist has been submitted as Supplemental Digital Content (SDC). (See Supplemental Digital Content 1 – STROBE Checklist.).

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Macewen CJ. Eye injuries: a prospective survey of 5671 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:888-94. [CrossRef]

- Fea A, Bosone A, Rolle T, Grignolo FM. Eye injuries in an Italian urban population: report of 10,620 cases admitted to an eye emergency department in Torino. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246(2):175-9. [CrossRef]

- Welch LS, Hunting KL, Mawudeku A. Injury surveillance in construction: eye injuries. Appl Occup Environ Hyg. 2001;16(7):755-62. [CrossRef]

- AlMahmoud T, Al Hadhrami SM, Elhanan M, Alshamsi HN, Abu-Zidan FM. Epidemiology of eye injuries in a high-income developing country: an observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(26):e16083. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed F, House RJ, Feldman BH. Corneal abrasions and corneal foreign bodies. Prim Care. 2015;42:363-75.

- Ozkurt ZG, Yuksel H, Saka G, Guclu H, Evsen S, Balsak S. Metallic corneal foreign bodies: an occupational health hazard. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2014;77:81-3.

- McGwin G Jr, Owsley C. Incidence of emergency department treated eye injury in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:662-8.

- Qayum S, Anjum R, Garg P. Epidemiological pattern of ocular trauma in a tertiary hospital of Northern India. Int J Med Clin Res. 2016;7:420-2.

- Islam SS, Doyle EJ, Velilla A, Martin CJ, Ducatman AM. Epidemiology of compensable work-related ocular injuries and illnesses: incidence and risk factors. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42:575-81.

- Macedo Filho ET, Lago A, Duarte K, Liang SJ, Lima AL, Freitas D. Superficial corneal foreign body: laboratory and epidemiologic aspects. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2005;68(6):821-3.

- Ramakrishnan T, Constantinou M, Jhanji V, Vajpayee RB. Corneal metallic foreign body injuries due to suboptimal ocular protection. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2012;67(1):48-50. [CrossRef]

- Brissette A, Mednick Z, Baxter S. Evaluating the need for close follow-up after removal of a non-complicated corneal foreign body. Cornea. 2014;33(11):1193-6.

- Pizzarello LD. Ocular trauma: time for action. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1998;5:115-6.

- United States Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration - Eye and Face Protection. Available from: https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/etools/eyeandface/index.html. Accessed 2019 Jan 14.

- Fong LP. Eye injuries in Victoria, Australia. Med J Aust. 1995;162:64-8.

- United States Department of Labor. Prevent eye injuries at work. Prof Safety. 2003;48:17.

- Government of Alberta. Eye protection at the work site. Available from: https://humanservices.alberta.ca/documents/WHS-PUB-PPE007.pdf. Accessed 2013 Dec 10.

- Agu AP, Umeokonkwo CD, Adeke AS, et al. Awareness of occupational hazards, use of personal protective equipment and workplace risk assessment among welders in Mechanic Village, Abakaliki, South-East Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2022;62(3):113-21.

- Jayamanne DG, Bell RW. Non-penetrating corneal foreign body injuries: factors affecting delay in rehabilitation of patients. J Accid Emerg Med. 1994;11(3):195-7. [CrossRef]

- Rebattu B, Baillif S, Ferrete T, et al. Corneal foreign bodies: are antiseptics and antibiotics equally effective? Eye (Lond). 2023;37(13):2664-72. [CrossRef]

- Camodeca AJ, Anderson EP. Corneal foreign body. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

- Tetteh KK, Owusu R, Axame WK. Prevalence and factors influencing eye injuries among welders in Accra, Ghana. Adv Prev Med. 2020;2020:2170247. [CrossRef]

- Zghal Mokni I, Nacef L, Kaoueche M, et al. Epidemiology of work related eye injuries. Tunis Med. 2007;85:576-9.

- Agrawal C, Girgis S, Sethi A, et al. Etiological causes and epidemiological characteristics of patients with occupational corneal foreign bodies: a prospective study in a hospital-based setting in India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(1):54-7. [CrossRef]

- Lipscomb HJ, Dement JM, McDougall V, Kalat J. Work-related eye injuries among union carpenters. Appl Occup Environ Hyg. 1999;14(10):665-76. [CrossRef]

- Lombardi DA, Pannala R, Sorock GS, et al. Welding related occupational eye injuries: a narrative analysis. Inj Prev. 2005;11(3):174-9. [CrossRef]

- Ahn JY, Ryoo HW, Park JB, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of work-related eye injuries and risk factors associated with severe eye injuries: a registry-based multicentre study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2020;27(2):105-14. [CrossRef]

- Simsek Z, Koruk İ, Doni NY. An operational study on implementation of mobile primary healthcare services for seasonal migratory farmworkers, Turkey. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:1906-12. [CrossRef]

- Koruk İ. İhmal edilen bir grup: göçebe mevsimlik tarım işçileri. TTB Mesleki Sağlık ve Güvenlik Dergisi. 2010;10(38):18-22.

- Ambikkumar A, Arthurs B, El-Hadad C. Corneal foreign bodies. CMAJ. 2022;194(11):E419. [CrossRef]

- Wipperman JL, Dorsch JN. Evaluation and management of corneal abrasions. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87(2):114-20.

- Loporchio D, Mukkamala L, Gorukanti K, et al. Intraocular foreign bodies: a review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016;61(5):582-96. [CrossRef]

- AlMahmoud T, Elkonaisi I, Grivna M, et al. Eye injuries and related risk factors among workers in small-scale industrial enterprises. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2020;27(6):453-9. [CrossRef]

- Zakrzewski H, Chung H, Sanders E, Hanson C, Ford B. Evaluation of occupational ocular trauma: are we doing enough to promote eye safety in the workplace? Can J Ophthalmol. 2017;52(4):338-42. [CrossRef]

- Koehler K, Ruggles J, Rule AM. Above and beyond: when we ask personal protective equipment to be community protective equipment. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2021;31(1):31-3. [CrossRef]

- Akboğa Kale Ö, Eskişar T. Kişisel koruyucu donanım kullanımının önemi ve gelişim planlaması için bir alan çalışması. Çalışma ve Toplum. 2021;4(71):2739-52. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).