1. Introduction

A geometric (

Clifford) algebra is an extension of elementary algebra to work with geometrical objects such as vectors. It is built out of two fundamental operations: addition and geometric product, [

1]. The multiplication of vectors results in objects called multivectors. Compared with any other formalism for manipulating vectors,

Clifford algebra alone supports dividing by vectors. The geometric product was first mentioned by

Grassmann, who founded the so-called external algebra, [

2]. After that,

Clifford himself greatly expanded upon

Grassmann’s work to form geometric algebra, named after him

Clifford algebra [

1], by unifying both

Grassmann’s algebra and

Hamilton’s quaternion algebra (

. In the middle of the 20th century,

Hestenes repopularized the term geometric algebra [

4,

5].

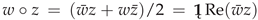

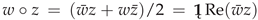

On the other hand, although rarely used explicitly, a geometric representation of complex numbers is implicitly based on its structure of the

Euclidean 2-dimensional vector space. If the binary operation of the product

of two complex numbers

and

z is considered as the sum of the inner product

and outer product

, where

= (1,

i0) and

į, and

i is an imaginary unit, it can be said that

is in the form of a geometric product of two

ivectors (two complex numbers), as two geometric objects belonging to the

ivector field

(to the field of complex numbers

). For any complex number

z, its absolute value

is its

Euclidean norm denoted by

, and the argument

of

z is the polar angle

. Since ordered pairs represent both complex numbers and vectors, the binary operation of the product of two complex numbers (two ordered pairs), in the form of the geometric product

(

), will be the basis for modifying

Grassmann’s geometric product of vectors, which is defined as the sum of the inner (scalar) and outer (vector) products of two vectors. By this modification, the geometric product of two vectors becomes commutative, similar to the product of complex numbers themselves, which still supports vector division.

It is a very old and interesting problem to obtain a natural extension of complex numbers, especially to three-dimensional complex numbers.

Hamilton interpreted complex numbers via couple numbers (ordered pairs of two real numbers), as points in the

Euclidean plane [

3], and he was looking for a way to do the same for points in a three-dimensional space. Points in space are triples of numbers.

Hamilton had known how to add and subtract triples. However, for a long time, he had been stuck on the problem of multiplication and division. In fact,

Frobenius proved, in 1877, that for a division algebra over the real numbers to be finite dimensional and associative, it cannot be three-dimensional. There are only three such division algebras:

,

and

, which have dimension 1, 2 and 4, respectively.

Segre[

15] described bicomplex numbers as points in a 4-dimensional space. Unlike

Hamilton’s quaternions, which are non-commutative and form a division algebra, bicomplex numbers are commutative and do not form a division algebra.

All told, many famous mathematicians have studied how to define multicomplex numbers and the corresponding function theory. Following this, and on the basis of the redefined geometric product of two vectors in the Euclidean plane, this paper presents the algebraic structure of the 3 field of complex vectors, as well as the corresponding integral identities.

The idea, on the basis of which the algebraic structure of the 3 field of complex vectors is defined, is as follows: At the beginning, a 2 field of complex vectors is introduced, which corresponds to the field of complex numbers , defined as a Cartesian product of one 1 real and one 1i-real vector space with a commutative geometric product of elements. Following the same pattern, in the next section a 3 field of complex vectors is introduced, which corresponds to the Cartesian product of one 3 real and one 3i-real vector space with a commutative geometric product of elements, defined as the sum of the geometric products of the elements in three complex planes. Each of these complex planes is the Cartesian products of one 1 real and one 1i-real vector space, which are vector subspaces of 3 real and 3i-real vector space, respectively. Clearly, one can take the Cartesian product of one 2 real and one 2i-real vector space in the same way. In that case, the geometric products of the elements in two complex planes are summed up, in order to obtain the commutative geometric product of the elements in this vector space.

2. The 2 Field of Complex Vectors

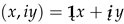

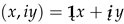

The ordered pairs

and

į form the basis of a 2-dimensional real

ireal vector (2

i-vector) space

, [

6,

9]. It is obvious that

is the

Cartesian product

of a one-dimensional real vector space and a one-dimensional

ireal vector space, and as such it is an additive

Abelian (commutative) group of

i-vectors

. On the other hand, it is possible to complete the

i-vector space

with a binary operation of the product of two

i-vectors

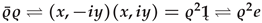

and

, which corresponds to the matrix product, in such a manner that

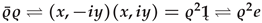

The inverse element

of the space

corresponds to the inverse matrix

. Here, both the commutative and associative axioms of multiplication and the distributive axiom are satisfied. Thus, the

i-vector space

becomes the field of complex numbers (

i-vectors)

, to which the field of complex vectors

corresponds. Two ordered pairs of one real and one imaginary vector,

and

, such that the unit vectors

(

) and

(

) are orthonormal basis vectors of the real plane

, form an orthonormal vector basis of the field

, so that

and

į⇌

. The complex vectors

, as elements of

, correspond to the complex numbers

. If

, then

is the norm on the fields

and

. In addition,

and

. It is quite clear that the inverse element

allows division by a vector in

. On the other hand, on the basis of the above-mentioned geometric product

of two complex numbers (

i-vectors)

and

, the corresponding geometric product of two complex vectors

and

in

can be defined as follows:

where

and

, which is obviously commutative. Here,

So, the dot and cross products of two complex vectors

and

in

are as follows:

where

. Since

, it follows that

3. The 3 Field of Complex Vectors

Let

,

and

be orthonormal basis vectors of the 3

space of real vectors

. Then, the following three pairs of ordered pairs:

and

,

and

, as well as

and

, form orthonormal bases of three 2

fields of complex vectors

, which are component fields of the 3

field of complex vectors with elements

where

are complex vectors in the component fields, and here, as in the following text, the index

(

), repeated as subscript and superscript in the products, represents the summation over the range of the index

, according to the

Einstein summation convention.

The commutative geometric product of two 3

complex vectors

a and

b is defined as the sum of the geometric products of the component vectors

and

, as follows:

Clearly,

and

. In addition, the vector

where

and

, such that

is the inverse vector of the 3

complex vector

a, which allows division by the vector in the 3

field of complex vectors. On the other hand, if

is denoted by the bracket

, it follows that

3.1. Differential Forms in

To represent a complex vector

in polar form, one introduces a vector analogue c

s of the shorthand notation c

is for the algebraic operator

+

, as follows:

Let = cs, where is the exponential form of the operator cs, be a radial unit complex vector in . Therefore, , where and , is a complex vector logarithmic function, and Log, . If and sc, then the ordered pair of unit vectors is the inverse orthonormal basis with respect to the orthonormal basis of the field of complex vectors . For an arbitrary vector , the vector is the rotated vector a, in the positive mathematical direction, by the angle , and the vector by the angle . The geometric products of the vector a with the inverse basis vectors and rotate a by the angles and , respectively, in the positive mathematical direction.

If

is a differential operator, then

. Hence,

and

. Since

and

, the vector operators of partial derivatives are introduced as a vector analogue of the

Virtinger operators [

16],

where

and

. It is important to emphasize that when geometric products and geometric quotients are differentiated, the same rules apply as when ordinary products and quotients are differentiated, so that

. Let’s prove this,

Definition 1. The geometric product is an operator of a differential form.

The symmetric and antisymmetric parts of the geometric product

are as follows:

Therefore,

where

and

are the radial and transverse components of

, respectively. Accordingly, since

, it follows that

which leads to the following vector differential identity,

Consequently,

since

. The vector identity just derived can be obtained explicitly via the

Jacobian determinant of the bijective mapping

, defined by the system of vector equations

and

as follows:

In this case,

, which leads to (

22). The complex vector

, corresponding to the

i-vector

į, is the

Lebesgue vector measure of the infinitesimal surface in the field

.

Definition 2. Let . Then, the geometric product is an operator of a differential form.

3.2. Fundamental Theorem of Integral Calculus in the Field

Let

be a closed smooth

Jordan curve, bounding an arbitrary simply connected region

G in

, and

be a point on

, surrounded by a circle

with center at

and arbitrarily small radius

, which intersects the curve

at the points

and

. Similarly, an arbitrary point

inside

G is surrounded by circle

, which is connected to the circle

by two parallel straight line segments

and

, at a distance

from each other. The region

S, inside which are the points

and

, and which is bounded by the segments

and

as well as the arc segments on the boundaries

and

of the circles

and

, whose endpoints are the intersection points of the boundaries

and

with the segments

and

, is the so-called residue region. If

, the contour integration operators are as follows:

where

is the boundary of

. Based on the additive property of definite integrals, in the limit, as

,

where

and

denote the principal and total integral values [

9]-[

14], respectively, and

(

is the interior of

S).

On the one hand, as a vector analogue of the so-called areolar (weak) derivative in complex analysis, defined by

Pompeiu [

8], the vector differential operator

is the gradient (the plane derivative) of

where

, so that

. Accordingly, on the basis of the result of the

Kelvin-Stokes theorem (

Green’s theorem) [

6],

Here,

so that

Consequently,

where

. The vector integral operator

where

is the vector residue operator in

G. Obviously, the operator

is a synonym for

.

By choosing two points, one on the contour

and the other inside the region

G, the generality of the previously obtained results is not lost, so that the fundamental theorem of integral calculus in

can be formulated in what follows. Previously, let

be a vector differential form

, obtained by applying

to an arbitrary uniform scalar or vector field • in

, [

7].

Theorem 1.

Let γ be a closed smooth Jordan curve, bounding an arbitrary simply connected region G in . For an arbitrary uniform scalar or vector field • in , which is regular almost everywhere on G and whose vector differential form is totally integrable on γ, there holds

where .

So, the integral formula in the previous theorem is a slightly generalized vector analogue of the

Cauchy-Pompeiu integral formula, [

17]. The sum of

, on the compact set of points

, at which the field • is regular (

is identically zero on

), is

. Hence,

, where

is the singular set, with

Lebesgue measure zero, of the field •. The sum on the right-hand side of the last integral equality can be in the indeterminate form of the difference of two infinities, which is equal to the finite integral value on the left-hand side.

3.3. Integral Calculus Formulas in the 3 Field of Complex

Vectors

Let

be simply connected regions bounded by closed smooth

Jordan curves

, such that they are projections of a smooth surface

S onto the component fields of the 3

field of complex vectors. The differential forms in the 3

field of complex vectors are as follows:

where

is an arbitrary uniform vector field in the 3

field of complex vectors,

and

. According to

Theorem 1., if the vector field

F is regular almost everywhere on

S, and the vector differential forms

and

are totally integrable on

, there holds

so that

Hence, to noted

and

.

Furthermore, since

where

,

and

, and in addition

, the vector identities (

41) and (

42) lead to the complex generalized

Stokes integral identity

where

, as well as to the complex vector integral identity

where

. Thus, the complex vector integral identities (

45) and (

46) are explicit consequences of the fundamental theorem of integral calculus in the

field of complex vectors, which follows.

Theorem 2.

Let γ be a closed smooth spatial curve in the field of complex vectors, bounding an arbitrary simply connected spatial surface S. For an arbitrary uniform complex vector field F, which is regular almost everywhere on S and whose differential form is totally integrable on γ, there holds

where .

On the other hand, it is quite possible to formulate the theorem, as follows, using a procedure similar to that used to formulate Theorem 1., based on the result of Green’s theorem, but now on the basis of Gauss-Ostrogradsky’s theorem.

Theorem 3.

Let S be a closed smooth surface in the field of complex vectors, bounding an arbitrary simply connected region V in that field. Then, for an arbitrary uniform complex vector field , which is regular almost everywhere on V and whose differential form is totally integrable on S, there holds

where .

Obviously, the integral formula (

48) is an explicit consequence of the following integral identities

where

,

and

. Therefore, if

and

, then

and outer product , where

and outer product , where  = (1, i0) and į, and i is an imaginary unit, it can be said that is in the form of a geometric product of two ivectors (two complex numbers), as two geometric objects belonging to the ivector field (to the field of complex numbers ). For any complex number z, its absolute value is its Euclidean norm denoted by , and the argument of z is the polar angle . Since ordered pairs represent both complex numbers and vectors, the binary operation of the product of two complex numbers (two ordered pairs), in the form of the geometric product (), will be the basis for modifying Grassmann’s geometric product of vectors, which is defined as the sum of the inner (scalar) and outer (vector) products of two vectors. By this modification, the geometric product of two vectors becomes commutative, similar to the product of complex numbers themselves, which still supports vector division.

= (1, i0) and į, and i is an imaginary unit, it can be said that is in the form of a geometric product of two ivectors (two complex numbers), as two geometric objects belonging to the ivector field (to the field of complex numbers ). For any complex number z, its absolute value is its Euclidean norm denoted by , and the argument of z is the polar angle . Since ordered pairs represent both complex numbers and vectors, the binary operation of the product of two complex numbers (two ordered pairs), in the form of the geometric product (), will be the basis for modifying Grassmann’s geometric product of vectors, which is defined as the sum of the inner (scalar) and outer (vector) products of two vectors. By this modification, the geometric product of two vectors becomes commutative, similar to the product of complex numbers themselves, which still supports vector division. and į form the basis of a 2-dimensional realireal vector (2 i-vector) space , [6,9]. It is obvious that is the Cartesian product of a one-dimensional real vector space and a one-dimensional ireal vector space, and as such it is an additive Abelian (commutative) group of i-vectors

and į form the basis of a 2-dimensional realireal vector (2 i-vector) space , [6,9]. It is obvious that is the Cartesian product of a one-dimensional real vector space and a one-dimensional ireal vector space, and as such it is an additive Abelian (commutative) group of i-vectors  . On the other hand, it is possible to complete the i-vector space with a binary operation of the product of two i-vectors and , which corresponds to the matrix product, in such a manner that

. On the other hand, it is possible to complete the i-vector space with a binary operation of the product of two i-vectors and , which corresponds to the matrix product, in such a manner that and į⇌. The complex vectors , as elements of , correspond to the complex numbers . If , then is the norm on the fields and . In addition,

and į⇌. The complex vectors , as elements of , correspond to the complex numbers . If , then is the norm on the fields and . In addition,  and . It is quite clear that the inverse element allows division by a vector in . On the other hand, on the basis of the above-mentioned geometric product of two complex numbers (i-vectors) and , the corresponding geometric product of two complex vectors and in can be defined as follows:

and . It is quite clear that the inverse element allows division by a vector in . On the other hand, on the basis of the above-mentioned geometric product of two complex numbers (i-vectors) and , the corresponding geometric product of two complex vectors and in can be defined as follows: