1. Introduction

Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is a fungal infection of the vaginal tissue and the vulva of the female reproductive tract that is caused mainly by

Candida albicans, an opportunistic fungal pathogen. Over 90% of VVC cases are attributed to

C. albicans, whereas the remaining 10% are caused by nonalbicans Candida (NAC) species, such as Nakaseomyces glabratus (formerly

Candida glabrata), Pichia kudriavzevii (formerly

C. krusei),

C. tropicalis and

C. parapsilosis [

1,

2,

3]. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) is characterized by three or more symptomatic episodes of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) within a year. RVVC is estimated to affect more than 130 million women in any given year, with a global annual prevalence of 3,871 per 100,000 females [

4]. Although most women report experiencing RVVC for 1–2 years, some women endure recurrent infections for 4–5 years or even for decades. [

5] This condition significantly impacts the quality of life of affected women, causing physical discomfort, psychological distress, and social stigma [

6,

7]. In qualitative research interviews, women with RVVC reported high levels of anxiety and fear regarding social interactions and dating as well as avoidance of sexual activity. [

8]. RVVC also imposes a substantial economic burden [

8]. In the United States, the total annual insurer and out-of-pocket costs for outpatient VVC treatment were estimated at US

$368 million in 2017. Additionally, the estimated annual economic impact of RVVC in the United States in 2010 from lost work hours was US

$1 billion. [

4,

9,

10].

The pathogenesis of RVVC is multifactorial and involves environmental factors, genetic predispositions and immune responses, including the role of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in the innate immune response [

11,

12].

2. Relevant Sections

2.1. Innate Immunity and Toll Like Receptors

Toll-like receptors, as evolutionarily conserved pattern recognition receptors, play a pivotal role in identifying pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [

13,

14], damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [

15] and initiating immune responses. These transmembrane proteins trigger signaling cascades that lead to the production of proinflammatory cytokines, which are essential for orchestrating the body's defense against infections [

15,

16]. TLRs are classified into several types, each recognizing specific PAMPs. Thus, TLR2 recognizes bacterial lipopeptides from gram-positive bacteria, TLR4 detects lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from gram-negative bacteria, and TLR3 is activated by double-stranded RNA [

17,

18] from viruses. This specificity enables the innate immune system to tailor its response to various different pathogens effectively. The engagement of TLRs with their ligands triggers intracellular signaling pathways, primarily the MyD88-dependent and TRIF-dependent pathways, which culminate in the activation of transcription factors such as nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and interferon regulatory factors (IRFs), leading to the expression of genes involved in inflammation and immune responses [

18].

During vulvovaginal candidiasis infection, PAMPs on the Candida’s surface are recognized by the innate immune system receptors, which activate intracellular signaling within vaginal epithelial cells [

19]. These signals stimulate a proinflammatory cytokine response that recruits immune cells, such as phagocytes and T cells, to eradicate the fungus. [

20].

2.2. Ligands of TLR2 and TLR4

TLR2 recognizes a wide range of ligands, which can be broadly categorized into microbial and endogenous components. Microbial ligands include triacylated and diacylated lipopeptides, peptidoglycans and lipoteichoic acid from bacteria as well as components from fungi and viruses [

21]. Endogenous ligands, such as heat shock proteins (HSPs) and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), can also activate TLR2, contributing to sterile inflammation and tissue repair processes [

22]. The interaction of TLR2 with these ligands triggers intracellular signaling cascades, primarily through the MyD88-dependent pathway, leading to the activation of NF-κB and the production of proinflammatory cytokines [

23].

TLR4 is primarily activated by LPS, a major component of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. The binding of LPS to TLR4 requires the presence of both the accessory protein CD14 and the MD-2 protein, which facilitates the formation of a signaling complex [

24]. This interaction initiates a robust immune response characterized by the production of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and the recruitment of immune cells to the site of infection. In addition to LPS, TLR4 can recognize a variety of other ligands, including endogenous molecules such as HSPs, fibronectin, and hyaluronic acid, which can be released during tissue injury or inflammation [

25]. These interactions have also been implicated in chronic inflammatory responses in various diseases, including cancer and autoimmune disorders [

26].

Figure 1.

Ligand recognition by TLR4 and TLR2 receptors. A. Recognition of LPS by TLR4: LPS, released from the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. LBP binds to LPS and presents it to CD14, which eventually leads to formation of TLR4-MD-2-LPS complex, resulting in dimerization of TLR4 subunits triggering TLR4 pathway. MD2 is necessary for TLR4 to bind to LPS and homodimerize. B. Recognition of LP, LTA by TLR2: TLR2 forms a heterodimer on the cell surface with co-receptors TLR1 or TLR6. The TLR2/TLR1 and TLR2/TLR6 heterodimers specifically bind LP, LTA released from gram-positive bacteria. The ligand binding to heterodimer brings the intracellular TIR domains close to each other and initiate signaling. Abbreviations: LPS, lipopolysaccharide; LBP, LPS binding protein; LTA, lipoteichoic acid; LP, lipopeptide; MD2, myeloid differentiation factor 2; Mal, MyD88-adapter-like; MyD88, myeloid differentiation 88 protein.

Figure 1.

Ligand recognition by TLR4 and TLR2 receptors. A. Recognition of LPS by TLR4: LPS, released from the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. LBP binds to LPS and presents it to CD14, which eventually leads to formation of TLR4-MD-2-LPS complex, resulting in dimerization of TLR4 subunits triggering TLR4 pathway. MD2 is necessary for TLR4 to bind to LPS and homodimerize. B. Recognition of LP, LTA by TLR2: TLR2 forms a heterodimer on the cell surface with co-receptors TLR1 or TLR6. The TLR2/TLR1 and TLR2/TLR6 heterodimers specifically bind LP, LTA released from gram-positive bacteria. The ligand binding to heterodimer brings the intracellular TIR domains close to each other and initiate signaling. Abbreviations: LPS, lipopolysaccharide; LBP, LPS binding protein; LTA, lipoteichoic acid; LP, lipopeptide; MD2, myeloid differentiation factor 2; Mal, MyD88-adapter-like; MyD88, myeloid differentiation 88 protein.

2.3. Signaling Pathways of TLR2 and TLR4

Upon ligand binding, TLR2 primarily activates the MyD88-dependent signaling pathway, which leads to the recruitment of various signaling molecules, including interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) and tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) [

23,

27]. This cascade results in the activation of NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), which are crucial for the transcription of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [

28]. Additionally, TLR2 can also activate the TRIF-dependent pathway, although this occurs less frequently. This pathway is associated with the production of type I interferons and is particularly important in the context of viral infections [

29]. The ability of TLR2 to engage multiple signaling pathways underscores its versatility in modulating immune responses.

TLR4 signaling also occurs through two pathways: the MyD88-dependent pathway and the TRIF-dependent pathway. The MyD88-dependent pathway is activated upon LPS binding and leads to the recruitment of IRAK and TRAF6, resulting in NF-κB activation and proinflammatory cytokine production [

30]. This pathway is critical for the early immune response to bacterial infections. The TRIF-dependent pathway is also activated by the binding of LPS to TLR4 and involves the recruitment of TRIF, leading to the activation of interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) and the subsequent production of type I interferons [

31]. This pathway is particularly important for antiviral responses and the regulation of adaptive immunity. The dual signaling capabilities of TLR4 allow for a robust and multifaceted immune response to a variety of pathogens.

Recent studies have highlighted the crosstalk between the TLR2 and TLR4 signaling pathways, suggesting that simultaneous activation of both receptors can enhance the immune response. For example, the costimulation of TLR2 and TLR4 in macrophages synergistically increases the production of proinflammatory cytokines, amplifying the overall immune response to infections [

32]. This crosstalk may also contribute to the development of chronic inflammatory conditions, where persistent activation of TLRs can lead to tissue damage and disease progression [

33].

2.4. Role of TLR2 and TLR4 in Fungal Recognition and RVVC

TLRs are integral to the ability of the innate immune system to detect fungal infections. Specifically, TLR2 and TLR4 have been shown to recognize components of the Candida cell wall, such as β-glucans and mannan, leading to the activation of inflammatory pathways and cytokine production [

6,

34]. This recognition is vital for the recruitment of immune cells to the site of infection, facilitating phagocytosis and the subsequent clearance of the pathogen [

35].

TLR2 recognizes phospholipomannans [

36], which leads to the local production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-6, which are key mediators of immune cell recruitment to the site of infection [

11,

37]. Similarly, TLR4 responds to O-linked mannans [

38], contributing to the inflammatory response. Genetic polymorphisms in these receptors can influence an individual's susceptibility to RVVC [

12]

Research indicates that TLR signaling not only promotes protective immune responses but also contributes to inflammatory pathology, potentially exacerbating the symptoms of RVVC [

34,

39]. This dual role underscores the complexity of TLR-mediated responses in fungal infections, where an excessive immune response may result in tissue damage and persistent symptoms.

The activation of TLRs leads to the production of various cytokines that orchestrate the immune response against Candida infections. In patients with RVVC, an exaggerated cytokine response, particularly in the presence of hyphae, has been observed, which are formed almost exclusively by

Candida albicans [

6,

40]. This heightened inflammatory response is believed to contribute to the symptoms associated with RVVC, negatively impacting quality of life.

Cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α are crucial for recruiting neutrophils and macrophages to the site of infection, promoting phagocytosis and fungal clearance [

41]. However, excessive cytokine production can lead to chronic inflammation, perpetuating the reinfection-inflammation cycle, which is characteristic of RVVC [

42,

43]. Understanding the balance between protective and pathological immune responses is essential for the development of targeted therapies for RVVC.

Figure 2.

During the infection process, Candida undergoes reversible yeast-to-hyphae transition, which causes changes in the type of surface carbohydrates, affecting the adhesion and invasion of vaginal epithelial cells. Candida infects vaginal vaginal epithelial cells directly through the invasion of hyphae and activates PAMPs with pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). In response to this, contact inflammatory immune mediators—chemokines, cytokines, antimicrobial peptides or damage-associated molecular patterns—are secreted, subsequently recruiting innate immune cells, such as macrophages, dendritic cells and neutrophils. These cells also recognize PAMPs through PRRs on their surfaces, bind to the pathogen, and stimulate its removal by phagocytosis.

Figure 2.

During the infection process, Candida undergoes reversible yeast-to-hyphae transition, which causes changes in the type of surface carbohydrates, affecting the adhesion and invasion of vaginal epithelial cells. Candida infects vaginal vaginal epithelial cells directly through the invasion of hyphae and activates PAMPs with pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). In response to this, contact inflammatory immune mediators—chemokines, cytokines, antimicrobial peptides or damage-associated molecular patterns—are secreted, subsequently recruiting innate immune cells, such as macrophages, dendritic cells and neutrophils. These cells also recognize PAMPs through PRRs on their surfaces, bind to the pathogen, and stimulate its removal by phagocytosis.

3. Discussion

3.1. Genetic Polymorphisms and Immune Response

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) strongly influence innate immune responses to pathogenic challenges and disease outcomes; therefore, individual susceptibility to infections varies, with some people being predisposed to certain infections and others being more resistant [

44]. In this context, host genetic variants in PRRs have long been thought to impair the antifungal immune response in RVVC patients. Genetic variations, including polymorphisms in TLRs and mannose-binding lectin, which may increase susceptibility to VVC [

20], have been observed in women with RVVC [

4,

45]. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms and other genetic alterations affecting key signaling proteins in the host may prompt the onset of VVC and increase susceptibility to RVVC [

20,

46]. Genetic variants in pattern recognition receptors or signal transducers have been found to impair the antifungal immune response in patients with RVVC [

20]. Variants in TLR2 and TLR4 have been associated with altered immune responses to Candida infections, suggesting that genetic predisposition plays a role in the pathogenesis of RVVC [

47,

48]. For example, certain TLR polymorphisms may impair the recognition of Candida components, leading to inadequate immune responses and increased susceptibility to recurrent infections [

12].

3.2. Polymorphisms in TLR4

The TLR4 gene is known to harbor several SNPs, with the most studied being Asp299Gly (rs4986790) and Thr399Ile (rs4986791). These two polymorphisms are in linkage disequilibrium. Linkage disequilibrium refers to the nonrandom association of alleles at different loci, which can often be observed in genetic studies. Several studies have reported that the Asp299Gly and Thr399Ile polymorphisms frequently cosegregate. Senhaji et al. conducted a meta-analysis that confirmed the presence of linkage disequilibrium between these two TLR4 polymorphisms, noting that they are often coinherited together as a haplotype [

49]. This finding is supported by the work of Ferwerda et al., who discussed how the proinflammatory phenotype associated with the Asp299Gly allele may have evolutionary implications, further suggesting the coinheritance of these alleles [

50]. The TLR4 Asp299Gly Thr399Ile haplotype has been reported to alter the leucine-rich repeat region of the receptor and decrease the efficiency of ligand recognition [

51].

Numerous studies have revealed a connection between TLR4 polymorphisms and susceptibility to infections. For example, the Asp299Gly polymorphism has been linked to a hypo-responsive state to LPS [

51], resulting in increased susceptibility to infections caused by gram-negative bacteria [

52,

53]. This hyporesponsiveness is particularly evident in individuals with the Asp299Gly variant, who exhibit diminished production of proinflammatory cytokines upon LPS stimulation [

52,

54]. Individuals carrying the Asp299Gly variant are at increased risk of developing severe infections, such as those caused by

Haemophilus influenzae and

Mycobacterium tuberculosis [

53]. A recent meta-analysis revealed that the TLR4 polymorphic locus rs10759932, which is located in an upstream regulatory region of the TLR4 gene, increased the risk of pulmonary tuberculosis [

55]. The G allele of rs4986790 (Asp299Gly mutation) is also an independent risk factor for pulmonary tuberculosis [

55].

Two other studies have demonstrated a link between this SNP and an increased risk of septic shock due to infection by gram-negativenegative individuals [

56,

57]. The TLR4 Asp299Gly haplotype has also been associated with an increased incidence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome [

58]. Ziakas et al. conducted a meta-analysis that highlighted the association of the TLR4 896 A>G and 1196 C>T SNPs with an increased risk for various infections, including malaria and other parasitic diseases [

59]. Both the TLR4-Asp299Gly and the TLR4-Thr399Ile variants confer an increased risk of severe malaria in Ghanaian children, linking these SNPs to disease manifestation [

60]. Rasouli et al. further elucidated the role of TLR4 polymorphisms in visceral leishmaniasis, demonstrating a higher prevalence of certain SNPs among affected individuals [

61].

The strongest association between TLR4 polymorphisms and disease susceptibility has been detected in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection, where infants heterozygous for Asp299Gly and Thr399Ile showed increased susceptibility to infection [

62]. Silva et al. reinforced this notion through a comprehensive meta-analysis, indicating that the TLR4 896A/G polymorphism is linked to a diverse spectrum of infections, emphasizing its complex role in immune response modulation [

63].

The mechanisms by which TLR4 SNPs influence disease susceptibility are multifaceted. The Asp299Gly polymorphism has been shown to alter TLR4 signaling pathways, leading to decreased NF-κB activation and altered cytokine production [

64]. This alteration can result in a diminished inflammatory response, which may predispose individuals to infections. Hold et al. demonstrated that both the Asp299Gly and Thr399Ile SNPs can upregulate the expression of TRIF-dependent genes, which play a catalytic role in the immune response to pathogens [

54]. These findings suggest that while these polymorphisms may confer susceptibility to certain infections, they may also enhance responses to others, thus demonstrating the intricate balance of immune regulation.

3.2. TLR4 Polymorphisms and Fungal Infections

TLR4 variants also influence antifungal immune responses. The TLR4 Asp299Gly Thr399Ile haplotype is associated with the development of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) in donors of allogeneic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) [

65]. However, the exact mechanism remains unknown, particularly since no fungal ligands have been identified to date. One proposed mechanism is that variations in the TLR4 gene alter cytokine production, which may affect the inflammatory response and the clearance of fungal infections [

12].

The crystal structure of TLR4 Asp299Gly/Thr399Ile has been solved as a complex with MD-2 and LPS [

66,

67]. Compared with the wild-type TLR4/MD-2/LPS complex structure, the overall arrangements of the two complexes were similar, and topical differences were present around only the Asp299Gly SNP site, which induced a structural change that modulated the surface properties of TLR4. This effect may be more apparent upon stimulation of TLR4 with ligands with weak agonistic activity. The impact of the Thr399Ile change was minor, as nearly no structural differences were observed [

67].

3.3. Polymorphisms in TLR2

TLR2, as a heterodimer with TLR1 or TLR6, recognizes a large number of common bacterial motifs, including lipopeptides, peptidoglycans, glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked proteins and zymosan. Dysregulation of TLR2 signaling due to genetic polymorphisms can lead to altered immune responses, potentially increasing susceptibility to infectious diseases [

68].

Several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified in the TLR2 gene, with the most studied being Arg677Trp (rs121917864) and Arg753Gln (rs5743708). These polymorphisms can affect the receptor's ability to recognize PAMPs and modulate immune responses [

68]. For example, the Arg677Trp variant has been associated with altered cytokine production in response to bacterial infections, suggesting a potential link to increased susceptibility to infectious diseases [

69]. Arg677Trp is common in African and Asian populations but is almost absent among Caucasian populations [

44]. In vitro, this SNP has been shown to inhibit both

Mycobacterium leprae- and

Mycobacterium tuberculosis-mediated NF-κB activation and production [

70]. In a studied Korean population and a Tunisian population, this SNP was associated with leprosy [

71] and susceptibility to tuberculosis [

72], respectively. Moreover, a study conducted in Iran revealed that the TLR2 Arg677Trp polymorphism was associated with a greater likelihood of infection among individuals exposed to

Mycobacterium tuberculosis [

73]. A meta-analysis revealed that the TLR2 Arg677Trp polymorphism was associated with an increased risk of severe periodontitis, confirming its role in modulating the immune response to oral pathogens [

74].

Studies have also revealed that the TLR2 Arg753Gln polymorphism is associated with increased susceptibility to tuberculosis and other infections. In this context, Bhanothu et al. reported that the TLR2 Arg753Gln variant is associated with the susceptibility of females to tuberculosis, suggesting that this SNP may influence immune responses to mycobacterial infections [

75,

76]. This polymorphism was also associated with an increased risk of developing tuberculosis in a Turkish population [

77], along with a significantly increased risk for some individuals to develop infective endocarditis [

78]. Additionally, TLR2 polymorphisms have been studied in the context of viral infections. Research has shown that certain TLR2 variants may influence the immune response to viruses such as dengue and HIV, potentially affecting disease outcomes [

79]. Kang et al. demonstrated that homozygosity for the TLR2 Arg753Gln SNP is a risk factor for cytomegalovirus disease following liver transplantation, indicating its potential role in modulating immune responses in transplant patients [

80]. Another study indicated that TLR2 polymorphisms are associated with the severity of dengue virus infection, suggesting that genetic variations in TLR2 may impact the host's ability to control viral replication [

81].

Figure 3.

Three dimensional structure of TLR4 and localization of their major polymorphisms.

Figure 3.

Three dimensional structure of TLR4 and localization of their major polymorphisms.

3.4. TLR2 Polymorphisms and Fungal Infections

The role of TLR2 in fungal infections has also been explored, particularly in the context of invasive fungal diseases. Studies have brought to light that TLR2 is involved in the recognition of fungal components, such as β-glucans, and plays a critical role in the immune response to fungi such as

Candida albicans and Aspergillus species [

82]. Polymorphisms in the TLR2 gene may affect susceptibility to these infections, with certain variants associated with an increased risk of invasive fungal disease in immunocompromised patients [

83]. For example, the R753Q TLR2 polymorphism increased the risk for candidaemia in a limited study through decreased IFN-γ and IL-8 levels [

84]. Similarly, a study examining TLR2 polymorphisms in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients revealed that specific genetic variants were linked to an increased risk of developing invasive aspergillosis, underscoring the importance of TLR2 in antifungal immunity [

85].

The Pro631His (rs5743704) SNP in TLR2 has been implicated in the development of idiopathic recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC). More specifically, the TLR2 Pro631His polymorphism was associated with an almost 3-fold increase in susceptibility to RVVC. [

86]. Moreover, TLR2 deficiency influences susceptibility to systemic candidiasis in mice [

87].

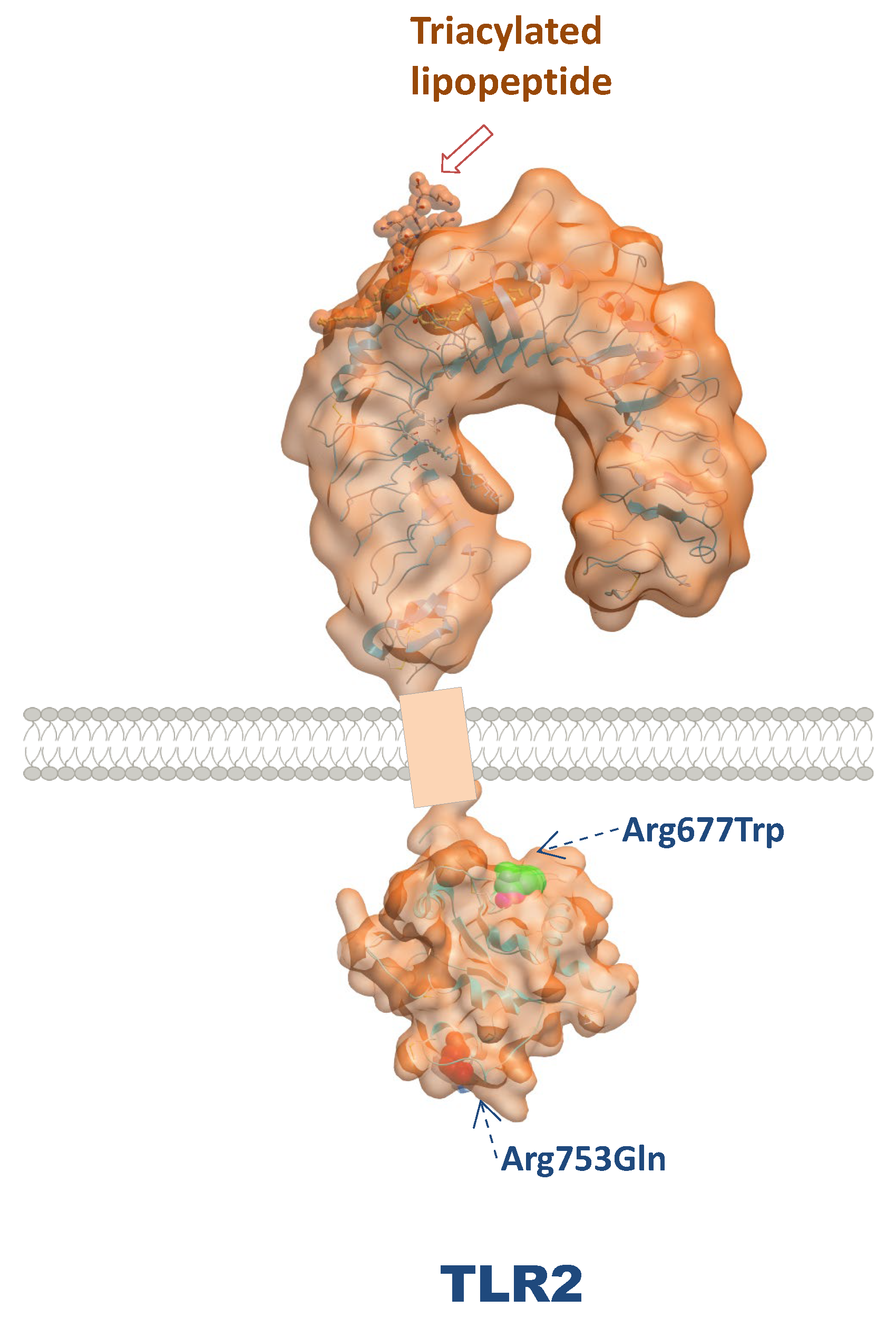

Figure 4.

Three dimensional structure of TLR2 and localization of their major polymorphisms.

Figure 4.

Three dimensional structure of TLR2 and localization of their major polymorphisms.

3.5. Polymorphisms in TLRs, Other Than TLR2 and TLR4, and Fungal Infections

Genetic variations in the TLR1, TLR3, TLR5 and TLR9 TLRs have also been proposed as risk factors for fungal disease. TLR1 appears to be an important repository of genetic variability, increasing susceptibility to candidaemia [

88]. For TLR9, the variant rs5743836 (in the promoter region) is associated with the development of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) [

89]. Another association involves TLR5, in which an SNP leading to an early stop codon (Arg392X) has been shown to disrupt flagellin recognition [

90]. In HSCT recipients, the presence of this variant was associated with the development of IPA [

90], suggesting a likely important antifungal function of TLR5. Despite being classically acknowledged as a prototypical receptor for double-stranded RNA, TLR3 has been implicated in fungal recognition and activation of adaptive immune responses. In particular, the regulatory variant rs3775296 in TLR3 was demonstrated to increase the risk of IPA after HSCT [

91]. However, the nonsynonymous SNP rs3775291 (Leu412Phe) in TLR3 was detected more frequently in patients suffering from chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC) [

92]

3.6. Interactions with Other Immune Components

The immune response to Candida spp. is not solely dependent on TLRs; other components of the innate immune system, such as C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), also play a significant role. CLRs, including Dectin-1, work in concert with TLRs to enhance the recognition and clearance of Candida [

42,

93]. The collaboration between TLRs and CLRs is vital for a comprehensive immune response, as they recognize different fungal components and activate distinct signaling pathways. In this context, genetic factors, such as those related to the mannose-binding lectin (MBL) pathway, increase the risk of RVVC. MBL deficiency has been shown to increase susceptibility to RVVC, highlighting the importance of a well-coordinated immune response in preventing recurrent infections [

94]. The interplay between these genetic factors and the immune system underscores the need for a comprehensive understanding of the immunological landscape in RVVC patients.

Moreover, the interaction between TLRs and other PRRs, such as Dectin-1, is crucial for a robust antifungal response. Dectin-1 recognizes β-glucans, while TLRs detect other fungal components, creating a synergistic effect that enhances the immune response against Candida [

42,

95]. This interplay underscores the importance of a well-functioning innate immune system in preventing RVVC.

Furthermore, the role of the inflammasome in the immune response to Candida spp. has gained attention. The NLRP3 inflammasome, for example, is activated in response to Candida spp. infection, leading to the processing of proinflammatory cytokines [

41]. This interaction highlights the complexity of the immune response, where multiple pathways converge to combat fungal infections.

4. Conclusions, Clinical Implications and Future Research Directions

The identification of specific TLR polymorphisms associated with RVVC risk can aid in the development of targeted treatments and prevention strategies. Understanding how genetic variability in immune receptors affects infection susceptibility opens possibilities for personalized therapeutic approaches, potentially using immunomodulators or antifungal therapies tailored to individual genetic profiles. TLRs themselves are also potential targets for therapeutic interventions. TLRs can be both friends and foes since improperly regulated TLR signaling can result either in the overactivation of immune responses, leading to pathologic inflammation, or in diminished inflammatory responses, which may predispose individuals to infections. In this context, recent efforts have focused on the development of both TLR antagonists as anti-inflammatory drug candidates and TLR agonists as immunotherapeutics [

76,

96]. Further research is warranted to investigate other polymorphisms in TLR-related pathways and their potential interactions with environmental factors that may contribute to RVVC, as well as to elucidate how these pathways might be therapeutically targeted to prevent recurrence.

This literature review summarizes current insights into the genetic underpinnings of RVVC, focusing on polymorphisms in TLR2 and TLR4 as significant factors in the host immune response, and highlights future directions for research and clinical practice to improve outcomes for those affected by RVVC.

Author Contributions

J.R., C.V. and M.M. collected the literature. J.R. written the manuscript. J.R., Ar.T. and At.T. designed and critically checked the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

References

- Kalia, N.; Singh, J.; Kaur, M. Immunopathology of Recurrent Vulvovaginal Infections: New Aspects and Research Directions. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binsaad, A.J.A.; Al-Abd, N. The Prevalence of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (Vvc) Among Women Suffering Vaginitis Attended a Private Gynecological Clinic, Aden-Yemen. Electronic Journal of University of Aden for Basic and Applied Sciences 2021, 2, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, O.E.; Gerstein, A.C. Differential Response Of Candida Species Morphologies and Isolates to Fluconazole and Boric Acid. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2022, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D.W.; Kneale, M.; Sobel, J.D.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R. Global burden of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: A systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, e339–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobel, J.D. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016, 214, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosati D, Bruno M, Jaeger M, Kullberg BJ, Veerdonk Fvd, Netea MG, Oever Jt. An Exaggerated Monocyte-Derived Cytokine Response to Candida Hyphae in Patients With Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020, 225, 1796–1806.

- Zhu, Y.; Li, T.; Fan, S.R.; Liu, P.; Liang, Y.; Liu, P. Health-Related Quality of Life as Measured With the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) Questionnaire in Patients With Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2016, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blostein, F.; Levin-Sparenberg, E.; Wagner, J.; Foxman, B. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Ann Epidemiol 2017, 27, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foxman, B.; Muraglia, R.; Dietz, J.P.; Sobel, J.D.; Wagner, J. Prevalence of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis in 5 European countries and the United States: Results from an internet panel survey. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2013, 17, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, H.M.E.; Ahmed, S.S.; Liu, J.; Xu, Z.; Peters, B.M. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: A Current Understanding and Burning Questions. J Fungi (Basel) 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardizzoni, A.; Wheeler, R.T.; Pericolini, E. It Takes Two to Tango: How a Dysregulation of the Innate Immunity, Coupled With Candida Virulence, Triggers VVC Onset. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeekens, S.P.; Frank, L.v.d.V.; Kullberg, B.J.; Netea, M.G. Genetic Susceptibility To Candida Infections. Embo Molecular Medicine 2013, 5, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Wu, K.H.; Wu, H.P. Unraveling the Complexities of Toll-Like Receptors: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, T.; Du, Y.; Xing, C.; Wang, H.Y.; Wang, R.F. Toll-Like Receptor Signaling and Its Role in Cell-Mediated Immunity. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. The Role of Pattern-Recognition Receptors in Innate Immunity: Update on Toll-Like Receptors. Nature Immunology 2010, 11, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-N.; Joe, Y.; Surh, Y.J.; Chung, H.T. Differential Regulation of Toll-Like Receptor-Mediated Cytokine Production by Unfolded Protein Response. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubarenko, A.V.; Ranjan, S.; Çolak, E.; George, J.; Frank, M.; Weber, A.N. Comprehensive Modeling and Functional Analysis of Toll-like Receptor Ligand-recognition Domains. Protein Science 2010, 19, 558–569. [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, K.; Akira, S. Toll-Like Receptors. Current Protocols in Immunology 2015, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, B.; Ferreira, C.; Alves, C.T.; Henriques, M.; Azeredo, J.; Silva, S. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: Epidemiology, microbiology and risk factors. Crit Rev Microbiol 2016, 42, 905–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, D.; Bruno, M.; Jaeger, M.; Ten Oever, J.; Netea, M.G. Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: An Immunological Perspective. Microorganisms 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasaei, R.; Sarodaya, N.; Kim, K.S.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hong, S.H. Importance of Deubiquitination in Macrophage-Mediated Viral Response and Inflammation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 8090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Yu, J. Modulation of Toll-Like Receptor Signaling in Innate Immunity by Natural Products. International Immunopharmacology 2016, 37, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Neill, L.A.; Bowie, A.G. The family of five: TIR-domain-containing adaptors in Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 2007, 7, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liao, M.; Wang, J. TLR4 Signaling in the Development of Colitis-Associated Cancer and Its Possible Interplay With microRNA-155. Cell Communication and Signaling 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi Jh Sun, S.C. Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor-Associated Factor Regulation of Nuclear Factor ΚB and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathways. Frontiers in Immunology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Gozalbo, D. Role of Toll-Like Receptors in Systemic I Candida Albicans I Infections. Frontiers in Bioscience-Scholar 2016, 21, 278–302. [Google Scholar]

- Marongiu, L.; Gornati, L.; Artuso, I.; Zanoni, I.; Granucci, F. Below the Surface: The Inner Lives of TLR4 and TLR9. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2019, 106, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadi, P.; García-Perdomo, H.A.; Karpiński, T.M. Toll-Like Receptors: General Molecular and Structural Biology. Journal of Immunology Research 2021, 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Cader, M.S.; Amarasinghe, A.; Abdul-Careem, M.F. Activation of Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Pathways Leading to Nitric oxide-Mediated Antiviral Responses. Archives of Virology 2016, 161, 2075–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown-Longo, P.J.; Higgins, P.J. Integration of Canonical and Noncanonical Pathways in TLR4 Signaling: Complex Regulation of the Wound Repair Program. Advances in Wound Care 2017, 6, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu Rh Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qu, J.; Cao, W.; Zhang, E.; He, J.; Cai, Z. How Are McPip1 and Cytokines Mutually Regulated in Cancer-Related Immunity? Protein & Cell 2020, 11, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheenstra, M.R.; Harten RMv Veldhuizen, E.J.; Haagsman, H.P.; Coorens, M. Cathelicidins Modulate TLR-Activation and Inflammation. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, S.G.; Hsu, F.-C.; Carter, D.; Orr, M.T. The Science of Vaccine Adjuvants: Advances in TLR4 Ligand Adjuvants. Current Opinion in Immunology 2016, 41, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, C.; Romani, L.; Carvalho, A. Cracking the Toll-Like Receptor Code in Fungal Infections. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy 2010, 8, 1121–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedovic, B.; Posteraro, B.; Leoncini, E.; Ruggeri, A.; Amore, R.; Ricciardi, W.; Boccia, S. Mannose-Binding Lectin Codon 54 Gene Polymorphism and Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed Research International 2014, 2014, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouault, T.; Ibata-Ombetta, S.; Takeuchi, O.; Trinel, P.A.; Sacchetti, P.; Lefebvre, P.; Akira, S.; Poulain, D. Candida albicans phospholipomannan is sensed through toll-like receptors. J Infect Dis 2003, 188, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, J.; Peters, B.M.; Noverr, M.C.; Fidel, P.L. Novel Mechanism Behind the Immunopathogenesis of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: “Neutrophil Anergy”. Infection and Immunity 2018, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netea, M.G.; Gow, N.A.; Munro, C.A.; Bates, S.; Collins, C.; Ferwerda, G.; Hobson, R.P.; Bertram, G.; Hughes, H.B.; Jansen Tet, a.l. Immune sensing of Candida albicans requires cooperative recognition of mannans and glucans by lectin and Toll-like receptors. J Clin Invest 2006, 116, 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Joosten, L.A.; Netea, MG. The interplay between inflammasome activation and antifungal host defense. Immunol Rev 2015, 265, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, D.; Bruno, M.; Jaeger, M.; Oever Jt Netea, M.G. Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: An Immunological Perspective. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, S.; Sutterwala, F.S. Fungal Pathogen Recognition by the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Virulence 2010, 1, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, M.-Y.; Li, M.; Bu, Q.-R.; Yang, Y.; Song, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, T.; Li, N. The Effect of Herbal Medicine in Innate Immunity to Candida Albicans. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, C.; Carvalho, A.; Esposito, A.; Bistoni, F.; Romani, L. DAMP Signaling in Fungal Infections and Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skevaki, C.; Pararas, M.; Kostelidou, K.; Tsakris, A.; Routsias, J.G. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of Toll-like receptors and susceptibility to infectious diseases. Clin Exp Immunol 2015, 180, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babula, O.; Lazdane, G.; Kroica, J.; Linhares, I.M.; Ledger, W.J.; Witkin, S.S. Frequency of interleukin-4 (IL-4) -589 gene polymorphism and vaginal concentrations of IL-4, nitric oxide, and mannose-binding lectin in women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis 2005, 40, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojang, E.; Ghuman, H.; Kumwenda, P.; Hall, R.A. Immune Sensing of Candida albicans. J Fungi (Basel) 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantinga, T.S.; Johnson, M.D.; Scott, W.K.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Meer JWMvd Perfect, J.R.; Kullberg, B.J.; Netea, M.G. Human Genetic Susceptibility ToCandidainfections. Medical Mycology 2012, 50, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, N.; SAK; Mohseni, S.; Aslani, N.; Ansari, S.; Badali, H. Is Human Dectin-1 Y238X Gene Polymorphism Related to Susceptibility to Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis? Current Medical Mycology 2016, 2, 15–19. [CrossRef]

- Senhaji, N.; Diakite, B.; Serbati, N.; Zaid, Y.; Badre, W.; Nadifi, S. Toll-Like Receptor 4 Asp299Gly and Thr399Ile Polymorphisms: New Data and a Meta-Analysis. BMC Gastroenterology 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferwerda, B.; McCall, M.; Alonso, S.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Mouktaroudi, M.; Izagirre, N.; Syafruddin, D.; Kibiki, G.; Cristea, T.; Hijmans Aet, a.l. <i>TLR4</I>polymorphisms, Infectious Diseases, and Evolutionary Pressure During Migration of Modern Humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 16645–16650. [Google Scholar]

- Arbour, N.C.; Lorenz, E.; Schutte, B.C.; Zabner, J.; Kline, J.N.; Jones, M.; Frees, K.; Watt, J.L.; Schwartz, D.A. TLR4 mutations are associated with endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in humans. Nature genetics 2000, 25, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; O'Connor, B.P.; Zemans, R.L.; Zhou, X.; Yang, I.V.; Schwartz, D.A. The Toll-like receptor 4 polymorphism Asp299Gly but not Thr399Ile influences TLR4 signaling and function. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenhu, E.; Terasjarvi, J.; Cruzeiro, M.L.; Savonius, O.; Rugemalira, E.; Roine, I.; He, Q.; Pelkonen, T. Gene Polymorphisms of TLR4 and TLR9 and Haemophilus influenzae Meningitis in Angolan Children. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hold, G.L.; Berry, S.; Saunders, K.A.; Drew, J.; Mayer, C.; Brookes, H.; Gay, N.J.; El-Omar, E.M.; Bryant, C.E. The TLR4 D299G and T399I SNPs are constitutively active to up-regulate expression of Trif-dependent genes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muheremu, A.; Jiang, J.; Yakufu, M.; Aili, A.; Li, L.; Luo, Z. Relationship between tool-like receptor 4 gene polymorphism and the susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Transl Res 2022, 14, 3893–3903. [Google Scholar]

- Agnese, D.M.; Calvano, J.E.; Hahm, S.J.; Coyle, S.M.; Corbett, S.A.; Calvano, S.E.; Lowry, S.F. Human toll-like receptor 4 mutations but not CD14 polymorphisms are associated with an increased risk of gram-negative infections. J Infect Dis 2002, 186, 1522–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, E.; Mira, J.P.; Frees, K.L.; Schwartz, D.A. Relevance of mutations in the TLR4 receptor in patients with gram-negative septic shock. Archives of internal medicine 2002, 162, 1028–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, N.J.; Yang, I.A.; Pulletz, M.C.; de Courcy-Golder, K.; Andrews, A.L.; Pappachan, V.J.; Holloway, J.W. Polymorphisms in Toll-like receptor 4 and the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Biochemical Society transactions 2003, 31(Pt 3), 652–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziakas, P.D.; Prodromou, M.L.; El Khoury, J.; Zintzaras, E.; Mylonakis, E. The role of TLR4 896 A>G and 1196 C>T in susceptibility to infections: A review and meta-analysis of genetic association studies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockenhaupt, F.P.; Cramer, J.P.; Hamann, L.; Stegemann, M.S.; Eckert, J.; Oh, N.R.; Otchwemah, R.N.; Dietz, E.; Ehrhardt, S.; Schroder NWet, a.l. Toll-like receptor (TLR) polymorphisms in African children: Common TLR-4 variants predispose to severe malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, M.; Keshavarz, M.; Kalani, M.; Moravej, A.; Kiany, S.; Badiee, P. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) polymorphisms in Iranian patients with visceral leishmaniasis. Mol Biol Rep 2012, 39, 10795–10802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awomoyi, A.A.; Rallabhandi, P.; Pollin, T.I.; Lorenz, E.; Sztein, M.B.; Boukhvalova, M.S.; Hemming, V.G.; Blanco, J.C.; Vogel, S.N. Association of TLR4 polymorphisms with symptomatic respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants and young children. J Immunol 2007, 179, 3171–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.A.; Santana, D.S.; de Oliveira, L.G.; Monteiro, E.O.L.; Lima, L. The relationship between 896A/G (rs4986790) polymorphism of TLR4 and infectious diseases: A meta-analysis. Front Genet 2022, 13, 1045725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, L.; Xiong, Y.; Song, C.; Piao, W.; Vogel, S.N.; Medvedev, A.E. The Asp299Gly polymorphism alters TLR4 signaling by interfering with recruitment of, M.y.D.8.8.; TRIF. J Immunol 2012, 188, 4506–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochud, P.Y.; Chien, J.W.; Marr, K.A.; Leisenring, W.M.; Upton, A.; Janer, M.; Rodrigues, S.D.; Li, S.; Hansen, J.A.; Zhao LPet, a.l. Toll-like receptor 4 polymorphisms and aspergillosis in stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 2008, 359, 1766–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohto, U.; Fukase, K.; Miyake, K.; Shimizu, T. Structural basis of species-specific endotoxin sensing by innate immune receptor TLR4/MD-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 7421–7426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohto, U.; Yamakawa, N.; Akashi-Takamura, S.; Miyake, K.; Shimizu, T. Structural analyses of human Toll-like receptor 4 polymorphisms, D.2.9.9.G.; T399I. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 40611–40617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, L.; Xiao, S.; Chen, W.; Hu, F.; Li, F.; Guo, P.; Chen, X.; Cai, W.; Tang, X. The Association of TLR2, TLR3, and TLR9 Gene Polymorphisms With Susceptibility to Talaromycosis Among Han Chinese AIDS Patients in Guangdong. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elloumi, N.; Tahri, S.; Fakhfakh, R.; Abida, O.; Mahfoudh, N.; Hachicha, H.; Marzouk, S.; Bahloul, Z.; Masmoudi, H. Role of Innate Immune Receptors TLR4 and TLR2 Polymorphisms in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Susceptibility. Annals of Human Genetics 2022, 86, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.J.; Lee, S.B.; Chae, G.T. A polymorphism in the toll-like receptor 2 is associated with IL-12 production from monocyte in lepromatous leprosy. Cytokine 2002, 20, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.J.; Chae, G.T. Detection of Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) mutation in the lepromatous leprosy patients. FEMS immunology and medical microbiology 2001, 31, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ali, M.; Barbouche, M.R.; Bousnina, S.; Chabbou, A.; Dellagi, K. Toll-like receptor 2 Arg677Trp polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to tuberculosis in Tunisian patients. Clinical and diagnostic laboratory immunology 2004, 11, 625–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davoodi, H.; Ghaemi, E.A.; Jamali, A.; Naeeme, J.S.; Shakeri, F. Arg677Trp and Arg753Gln Polymorphisms in TLR2 Genes Detected in Patients With Tuberculosis in Golestan Province, Iran. Jundishapur Journal of Microbiology 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.; Abasijiang, A.; Wu, Z.P.; Wang, T.T.; Jin, Z. Association of TLR-2 Gene Polymorphisms With the Risk of Periodontitis: A Meta-Analysis. Disease Markers 2020, 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhanothu, V.; Lakshmi, V.; Theophilus, J.; Rozati, R.; Badhini, P.; Vijayalaxmi, B. Investigation of Toll-Like Receptor-2 (2258g/A) and Interferon Gamma (+874t/A) Gene Polymorphisms Among Infertile Women With Female Genital Tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Spaink, H.P. The Role of TLR2 in Infectious Diseases Caused by Mycobacteria: From Cell Biology to Therapeutic Target. Biology 2022, 11, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogus, A.C.; Yoldas, B.; Ozdemir, T.; Uguz, A.; Olcen, S.; Keser, I.; Coskun, M.; Cilli, A.; Yegin, O. The Arg753GLn polymorphism of the human toll-like receptor 2 gene in tuberculosis disease. The European respiratory journal : Official journal of the European Society for Clinical Respiratory Physiology 2004, 23, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, J.; Tamayo, E.; Florez, S.; Telleria, J.J.; Bustamante, E.; Lopez, J.; San Roman, J.A.; Alvarez, F.J. [Toll-like receptor 2 R753Q polymorphisms are associated with an increased risk of infective endocarditis]. Revista espanola de cardiologia 2011, 64, 1056–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masin, P.S.; Visentin, H.A.; Elpidio, L.N.S.; Sell, A.M.; Visentainer, L.; Quirino Alves de Lima, N.; Zacarias, J.M.V.; Couceiro, P.; Shinzato, A.H.; Rosa MSet, a.l. Genetic Polymorphisms of Toll-Like Receptors in Leprosy Patients From Southern Brazil. Frontiers in Genetics 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.S.; Abdel-Massih, R.; Brown, R.A.; Dierkhising, R.A.; Kremers, W.K.; Razonable, R.R. Homozygosity for the Toll-Like Receptor 2 R753Q Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism Is a Risk Factor for Cytomegalovirus Disease After Liver Transplantation. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2012, 205, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zheng, L.; Chen, P.; Liang, G. Myeloid Differentiation Primary Response Protein 88 (MyD88): The Central Hub of TLR/IL-1R Signaling. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 63, 13316–13329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, C.; Choi, K.-Y.G.; Kroeker, A.; Denechezhe, L.; Orr, P.; Mookherjee, N.; Larcombe, L. Polymorphisms in the P2X7 Receptor, and Differential Expression of Toll-Like Receptor-Mediated Cytokines and Defensins, in a Canadian Indigenous Group. Scientific Reports 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakath, F.B.; Varatharajan, S.; Premkumar, P.S.; Syed, C.; Ward, H.; Kang, G.; Ajjampur, S.S.R. Toll-Like Receptors and Mannose Binding Lectin Gene Polymorphisms Associated With Cryptosporidial Diarrhea in Children in Southern India. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2021, 105, 1706–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woehrle, T.; Du, W.; Goetz, A.; Hsu, H.Y.; Joos, T.O.; Weiss, M.; Bauer, U.; Brueckner, U.B.; Marion Schneider, E. Pathogen specific cytokine release reveals an effect of TLR2 Arg753Gln during Candida sepsis in humans. Cytokine 2008, 41, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, B.M.; Noha, A.S.M.; Manal, A.A.M.; Engy, S.M. Role of Toll-Like Receptors 2 and 4 Genes Polymorphisms in Neonatal Sepsis in a Developing Country: A Pilot Study. Journal of Pediatric Infectious Diseases 2020, 15, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosentul, D.C.; Delsing, C.E.; Jaeger, M.; Plantinga, T.S.; Oosting, M.; Costantini, I.; Venselaar, H.; Joosten, L.A.; van der Meer, J.W.; Dupont Bet, a.l. Gene polymorphisms in pattern recognition receptors and susceptibility to idiopathic recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Front Microbiol 2014, 5, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netea, M.G.; Brown, G.D.; Kullberg, B.J.; Gow, N.A. An integrated model of the recognition of Candida albicans by the innate immune system. Nat Rev Microbiol 2008, 6, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plantinga, T.S.; Johnson, M.D.; Scott, W.K.; van de Vosse, E.; Velez Edwards, D.R.; Smith, P.B.; Alexander, B.D.; Yang, J.C.; Kremer, D.; Laird GMet, a.l. Toll-like receptor 1 polymorphisms increase susceptibility to candidemia. J Infect Dis 2012, 205, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, A.; Pasqualotto, A.C.; Pitzurra, L.; Romani, L.; Denning, D.W.; Rodrigues, F. Polymorphisms in toll-like receptor genes and susceptibility to pulmonary aspergillosis. J Infect Dis 2008, 197, 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawn, T.R.; Verbon, A.; Lettinga, K.D.; Zhao, L.P.; Li, S.S.; Laws, R.J.; Skerrett, S.J.; Beutler, B.; Schroeder, L.; Nachman Aet, a.l. A common dominant TLR5 stop codon polymorphism abolishes flagellin signaling and is associated with susceptibility to legionnaires' disease. J Exp Med 2003, 198, 1563–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.; De Luca, A.; Bozza, S.; Cunha, C.; D'Angelo, C.; Moretti, S.; Perruccio, K.; Iannitti, R.G.; Fallarino, F.; Pierini Aet, a.l. TLR3 essentially promotes protective class I-restricted memory CD8(+) T-cell responses to Aspergillus fumigatus in hematopoietic transplanted patients. Blood 2012, 119, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahum, A.; Dadi, H.; Bates, A.; Roifman, C.M. The L412F variant of Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) is associated with cutaneous candidiasis, increased susceptibility to cytomegalovirus, and autoimmunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011, 127, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatinguais, R.; Willment, J.A.; Brown, G.D. C-type Lectin Receptors in Antifungal Immunity: Current Knowledge and Future Developments. Parasite Immunology 2022, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosentul, D.C.; Delsing, C.E.; Jaeger, M.; Plantinga, T.S.; Oosting, M.; Costantini, I.; Venselaar, H.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Meer JWMvd Dupont Bet, a.l. Gene Polymorphisms in Pattern Recognition Receptors and Susceptibility to Idiopathic Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Frontiers in Microbiology 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Castrillón-Betancur, J.C.; Klaile, E.; Slevogt, H. The Interaction of Human Pathogenic Fungi With C-Type Lectin Receptors. Frontiers in Immunology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, H.; Zamyatina, A. Therapeutic Targeting of TLR4 for Inflammation, Infection, and Cancer: A Perspective for Disaccharide Lipid A Mimetics. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).