Submitted:

05 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

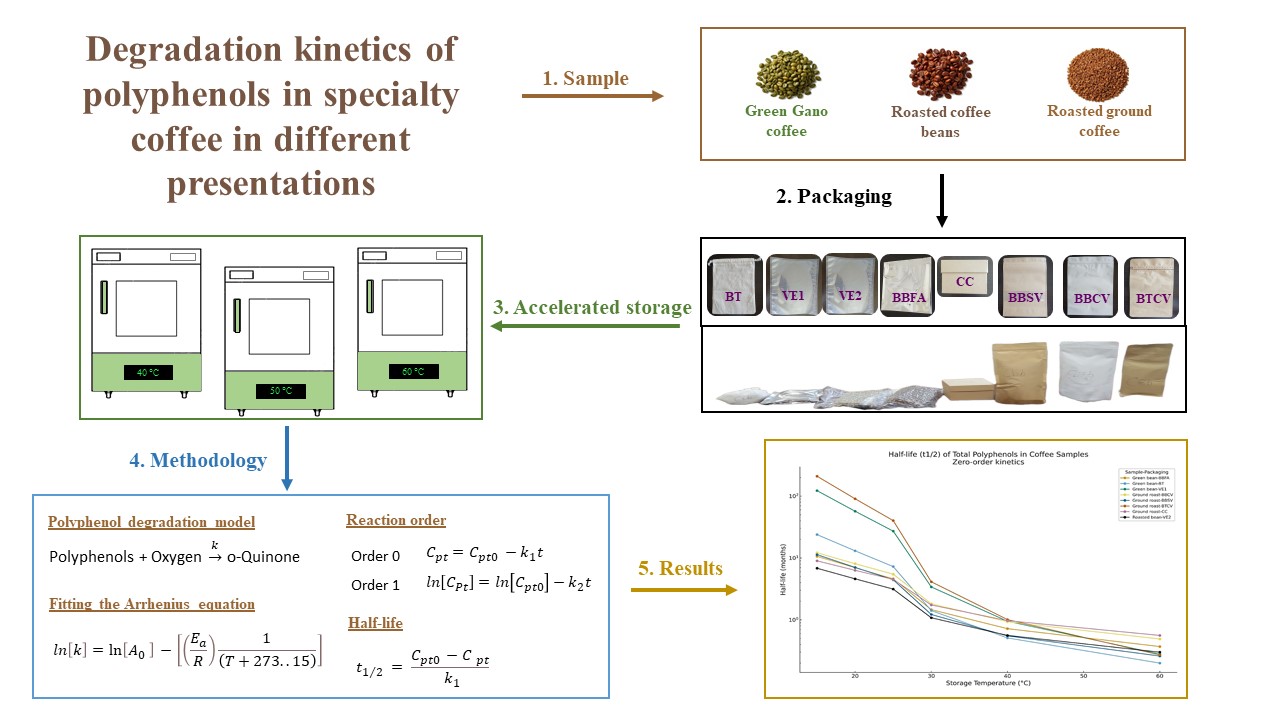

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of the Sample

2.3. Accelerated Storage

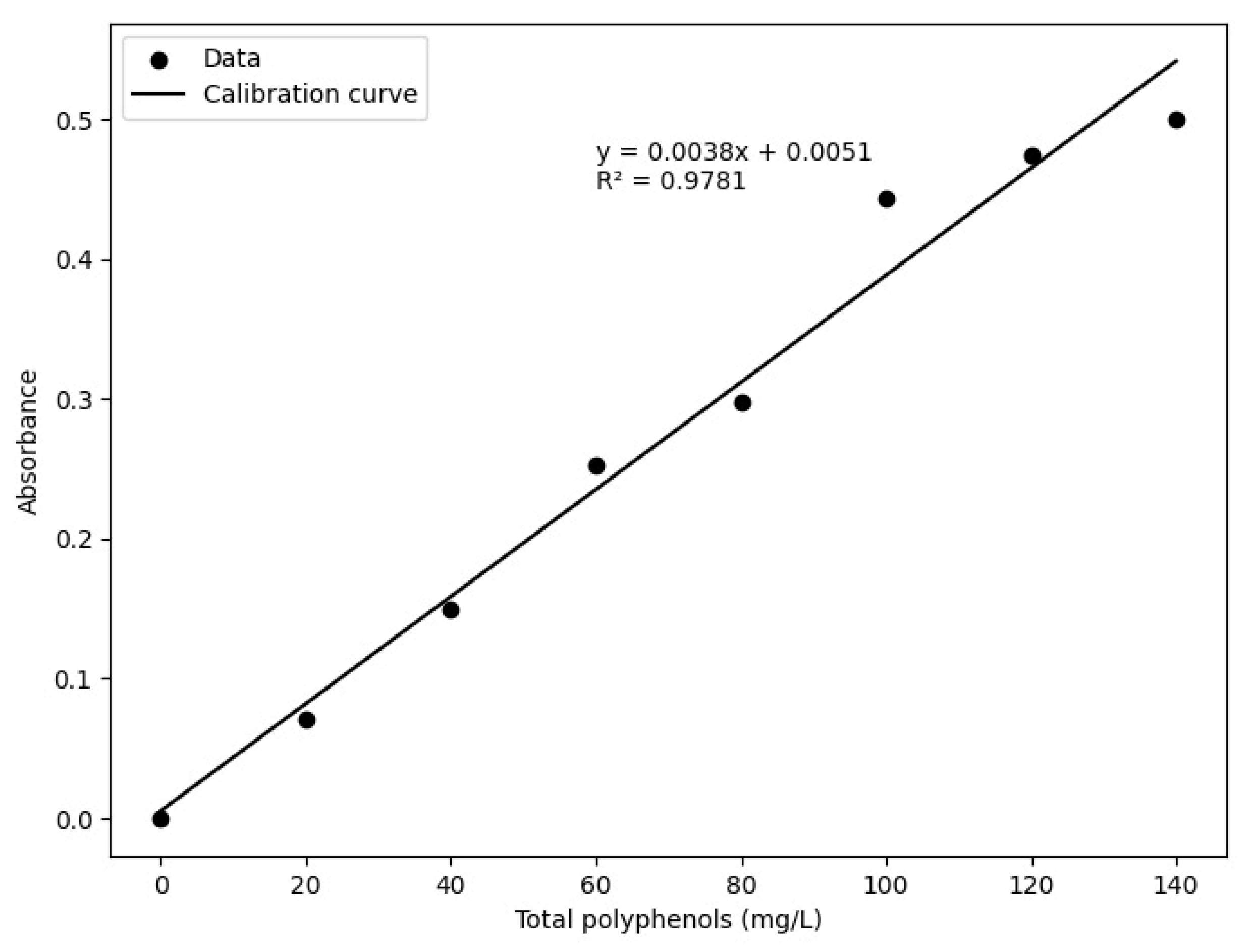

2.4. Total Polyphenol Content

2.5. Polyphenol Degradation Model

2.5.1. Chemical Kinetics

2.5.2. Determination of the Reaction Order

2.5.3. Calculation of Activation Energy (Ea) and Pre-Exponential Factor (A0)

2.5.4. Estimation of the Average Retention Time of Total Polyphenols

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

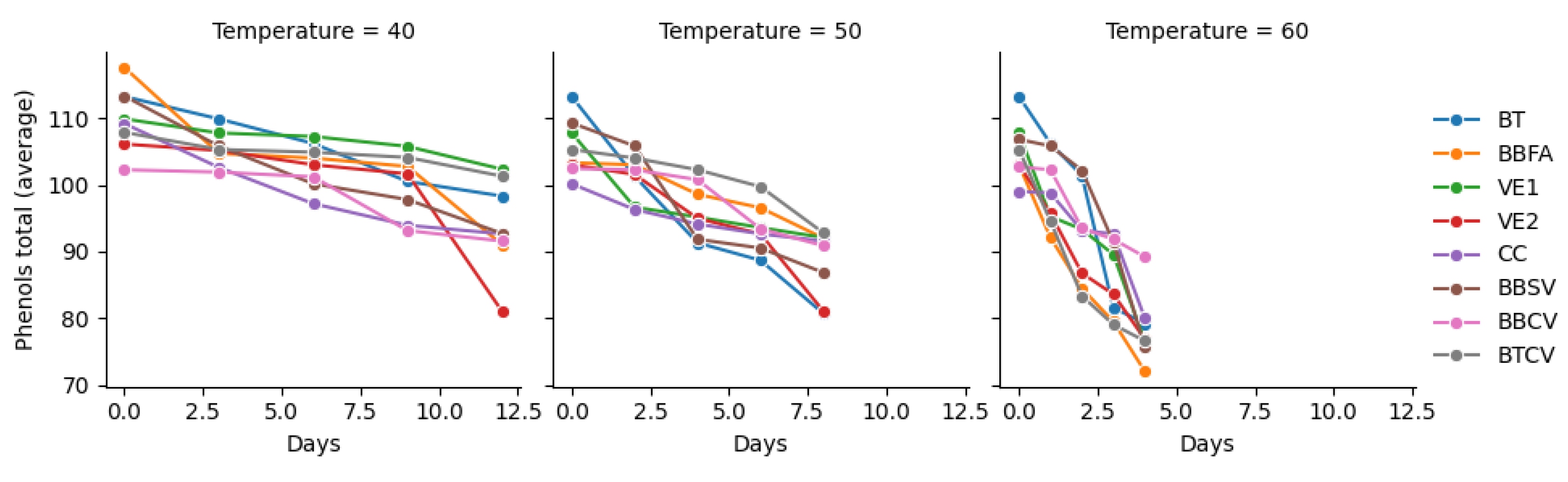

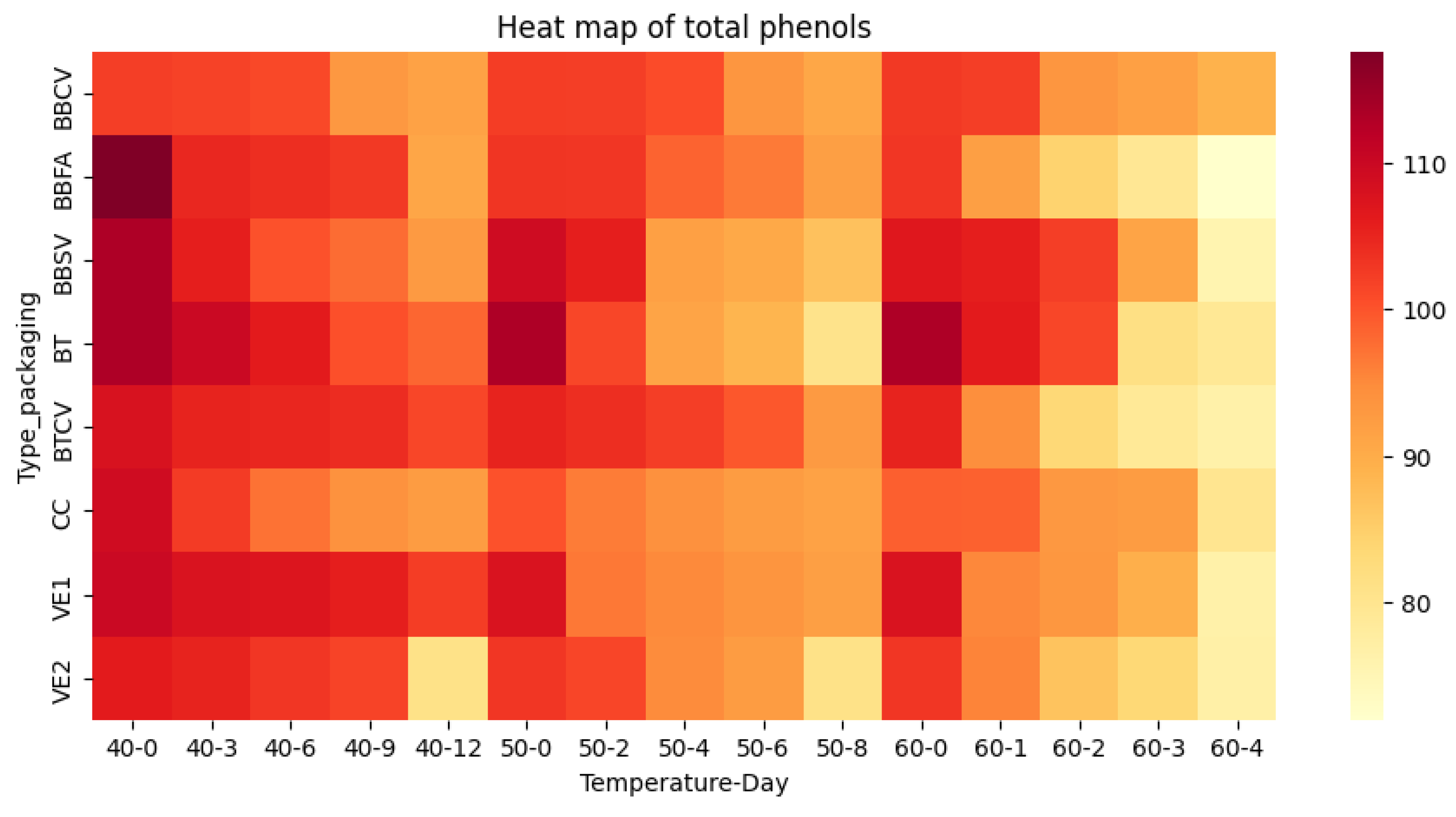

3.1. Quantification of Total Polyphenols

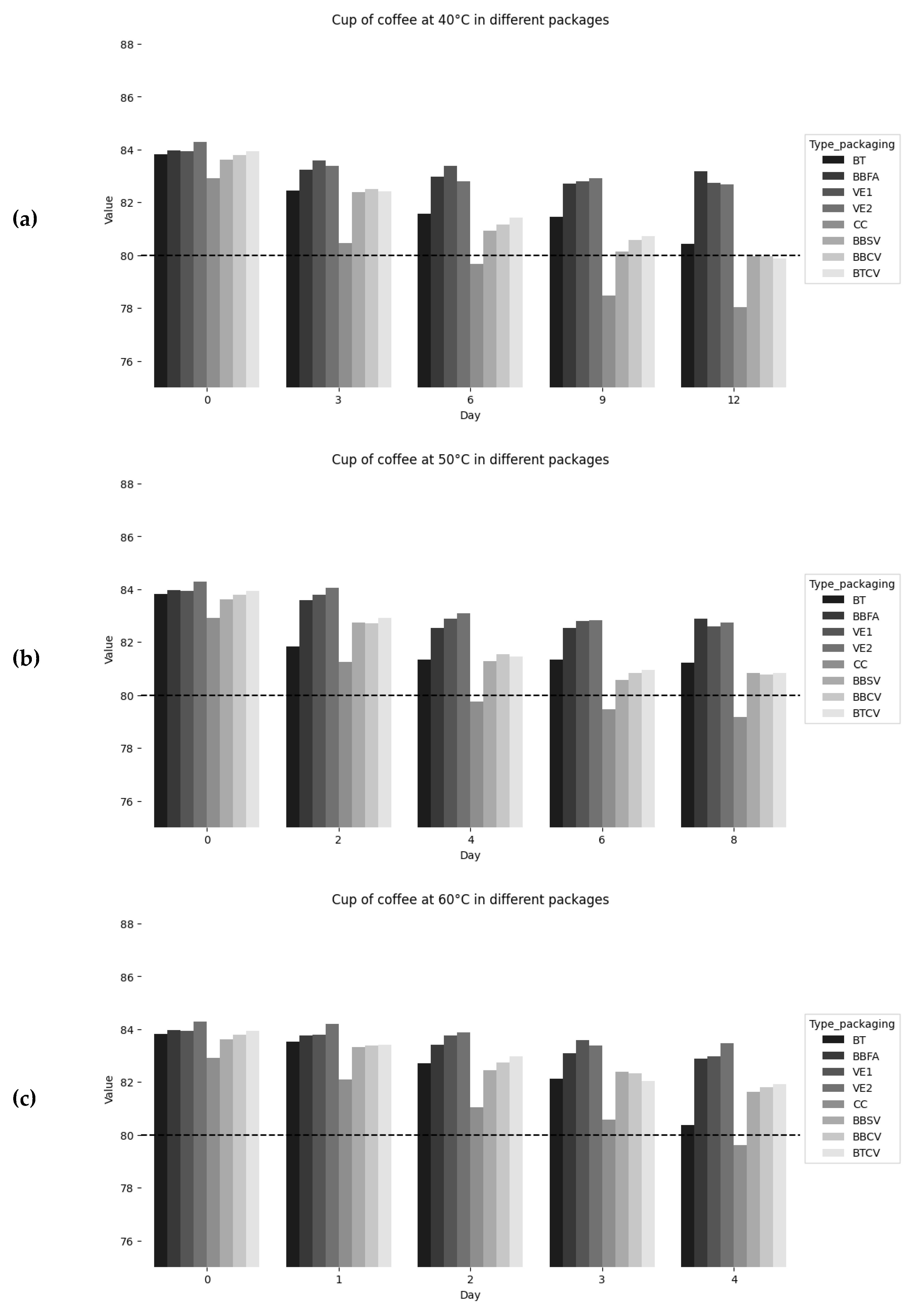

3.2. Determination of the Reaction Order

3.3. Determination of the Kinetic Constants of Deterioration (k)

3.4. Estimated Half-Life of Total Polyphenol Retention

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ponder, A.; Krakówko, K.; Kruk, M.; Kuliński, S.; Magoń, R.; Ziółkowski, D.; Jariene, E.; Hallmann, E. Organic and Conventional Coffee Beans, Infusions, and Grounds as a Rich Sources of Phenolic Compounds in Coffees from Different Origins. Molecules 2025, 30, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagó-Mas, A.; Korimová, A.; Deulofeu, M.; Verdú, E.; Fiol, N.; Svobodová, V.; Dubovỳ, P.; Boadas-Vaello, P. Polyphenolic Grape Stalk and Coffee Extracts Attenuate Spinal Cord Injury-Induced Neuropathic Pain Development in ICR-CD1 Female Mice. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkholder-Cooley, N.; Rajaram, S.; Haddad, E.; Fraser, G.E.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K. Comparison of Polyphenol Intakes According to Distinct Dietary Patterns and Food Sources in the Adventist Health Study-2 Cohort. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 2162–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bo’, C.; Bernardi, S.; Marino, M.; Porrini, M.; Tucci, M.; Guglielmetti, S.; Cherubini, A.; Carrieri, B.; Kirkup, B.; Kroon, P. Systematic Review on Polyphenol Intake and Health Outcomes: Is There Sufficient Evidence to Define a Health-Promoting Polyphenol-Rich Dietary Pattern? Nutrients 2019, 11, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdem, S.A.; Senol, F.S.; Budakoglu, E.; Orhan, I.E.; Sener, B. Exploring in Vitro Neurobiological Effects and High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography-Assisted Quantitation of Chlorogenic Acid in 18 Turkish Coffee Brands. J. Food Drug Anal. 2016, 24, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, Y.; Tashiro, T.; Kumagai, A.; Ohyanagi, H.; Horiuchi, T.; Takizawa, K.; Sugihara, N.; Kishimoto, Y.; Taguchi, C.; Tani, M.; et al. Coffee and Beverages Are the Major Contributors to Polyphenol Consumption from Food and Beverages in Japanese Middle-Aged Women. J. Nutr. Sci. 2014, 3, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giulia, S.; Eloisa, B.; Giulia, R.; Gloria, P.; Carlo, B.; Erica, L. Evaluation of the Behaviour of Phenols and Alkaloids in Samples of Roasted and Ground Coffee Stored in Different Types of Packaging: Implications for Quality and Shelf Life. Food Res. Int. 2023, 174, 113548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.H.; Tan, L. ’B; Hiramatsu, N.; Ishisaka, A.; Alfonso, H.; Tanaka, A.; Uemura, N.; Fujiwara, Y.; Takechi, R. Plasma Concentrations of Coffee Polyphenols and Plasma Biomarkers of Diabetes Risk in Healthy Japanese Women. Nutr. Diabetes 2016, 6, e212–e212. [CrossRef]

- Loftfield, E.; Shiels, M.S.; Graubard, B.I.; Katki, H.A.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Trabert, B.; Pinto, L.A.; Kemp, T.J.; Shebl, F.M.; Mayne, S.T.; et al. Associations of Coffee Drinking with Systemic Immune and Inflammatory Markers. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2015, 24, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.M.; Steluti, J.; Fisberg, R.M.; Marchioni, D.M. Dietary Intake and Food Contributors of Polyphenols in Adults and Elderly Adults of Sao Paulo: A Population-Based Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudrapal, M.; Khairnar, S.J.; Khan, J.; Dukhyil, A.B.; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; Alshabrmi, F.M.; Palai, S.; Deb, P.K.; Devi, R. Dietary Polyphenols and Their Role in Oxidative Stress-Induced Human Diseases: Insights Into Protective Effects, Antioxidant Potentials and Mechanism(s) of Action. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socała, K.; Szopa, A.; Serefko, A.; Poleszak, E.; Wlaź, P. Neuroprotective Effects of Coffee Bioactive Compounds: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajik, N.; Tajik, M.; Mack, I.; Enck, P. The Potential Effects of Chlorogenic Acid, the Main Phenolic Components in Coffee, on Health: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 2215–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, K. Do Coffee Polyphenols Have a Preventive Action on Metabolic Syndrome Associated Endothelial Dysfunctions? An Assessment of the Current Evidence. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Várady, M.; Tauchen, J.; Fraňková, A.; Klouček, P.; Popelka, P. Effect of Method of Processing Specialty Coffee Beans (Natural, Washed, Honey, Fermentation, Maceration) on Bioactive and Volatile Compounds. LWT 2022, 172, 114245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba, N.; Moreno, F.L.; Osorio, C.; Velásquez, S.; Fernandez-Alduenda, M.; Ruiz-Pardo, Y. Specialty and Regular Coffee Bean Quality for Cold and Hot Brewing: Evaluation of Sensory Profile and Physicochemical Characteristics. LWT 2021, 145, 111363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merga Sakata, W.; Gebreselassie Abtew, W.; Garedew, W. Organoleptic Quality Attributes and Their Association with Morphological Traits in Arabica Coffee (Coffea Arabica L.) Genotypes. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 2906424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rune, C.J.B.; Münchow, M.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A.; Giacalone, D. Pairing Coffee with Basic Tastes and Real Foods Changes Perceived Sensory Characteristics and Consumer Liking. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 30, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, V. de C.; da Silva, M.A.E.; da Veiga, V.F.; Pereira, H.M.G.; de Rezende, C.M. Ent-Kaurane Diterpenoids from Coffea Genus: An Update of Chemical Diversity and Biological Aspects. Molecules 2025, 30, 59. [CrossRef]

- Amiri, R.; Akbari, M.; Moradikor, N. Chapter Two - Bioactive Potential and Chemical Compounds of Coffee. In Progress in Brain Research; Moradikor, N., Chatterjee, I., Eds.; Neuroscience of Coffee Part A; Elsevier, 2024; Vol. 288, pp. 23–33.

- Hameed, A.; Hussain, S.A.; Ijaz, M.U.; Ullah, S.; Pasha, I.; Suleria, H.A.R. Farm to Consumer: Factors Affecting the Organoleptic Characteristics of Coffee. II: Postharvest Processing Factors. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 1184–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.-L.; Alafifi, J.H.; Quan, C.-X.; Al-Romaima, A.; Qiu, M.-H. Exploring the Complexities of Bitterness: A Comprehensive Review of Methodologies, Bitterants, and Influencing Factors Centered around Coffee Beverage. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 0, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapčíková, B.; Lapčík, L.; Barták, P.; Valenta, T.; Dokládalová, K. Effect of Extraction Methods on Aroma Profile, Antioxidant Activity and Sensory Acceptability of Specialty Coffee Brews. Foods 2023, 12, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, D.S.; Albuquerque, T.G.; Costa, H.S.; Bragotto, A.P.A. Thermal Contaminants in Coffee Induced by Roasting: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, E.B.; Wardiana, E.; Hilmi, Y.S.; Komarudin, N.A. The Changes in Chemical Properties of Coffee during Roasting: A Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 974, 012115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzelczyk, J.; Budryn, G.; Kołodziejczyk, K.; Ziętala, J. The Influence of Maceration and Flavoring on the Composition and Health-Promoting Properties of Roasted Coffee. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misto, M.; Lestari, N.P.; Purwandari, E. Chlorogenic Acid Content of Local Robusta Coffee at Variations of Roasting Temperature. J. Pendidik. Fis. Indones. 2022, 18, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Saroglu, O.; Karadag, A.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Zoccatelli, G.; Conte-Junior, C.A.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G.A.; Ou, J.; Bai, W.; Zamarioli, C.M.; et al. Available Technologies on Improving the Stability of Polyphenols in Food Processing. Food Front. 2021, 2, 109–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Long, J.; Gong, Z.; Nong, K.; Liang, X.; Qin, T.; Huang, W.; Yang, L. Current State of Knowledge on the Antioxidant Effects and Mechanisms of Action of Polyphenolic Compounds. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2021, 16, 1934578X211027745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, N.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Fei, P. Preparation of Acylated Chitosan with Caffeic Acid in Non-Enzymatic and Enzymatic Systems: Characterization and Application in Pork Preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 194, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, A.; McHenry, M.P.; McHenry, J.A.; Solah, V.; Bayliss, K. Enzymatic Browning: The Role of Substrates in Polyphenol Oxidase Mediated Browning. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Nicolás, J.; García-Carmona, F. Enzymatic and Nonenzymatic Degradation of Polyphenols. In Fruit and Vegetable Phytochemicals; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2009; pp. 101–129 ISBN 978-0-8138-0939-7.

- Vauzour, D.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Corona, G.; Oruna-Concha, M.J.; Spencer, J.P.E. Polyphenols and Human Health: Prevention of Disease and Mechanisms of Action. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1106–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia-Fang, T.; Irvan, J.J. The Analysis of Chlorogenic Acid and Caffeine Content and Its Correlation with Coffee Bean Color under Different Roasting Degree and Sources of Coffee (Coffea Arabica Typica). Processes 2021, 9, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwiková, O.; Komprda, T.; Šottníková, V.; Svoboda, Z.; Simonová, J.; Slováček, J.; Jůzl, M. Effects of Different Processing Methods of Coffee Arabica on Colour, Acrylamide, Caffeine, Chlorogenic Acid, and Polyphenol Content. Foods 2022, 11, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, K.K.; Jae-Min, L.; Young, J.K.; Wook, K. Alterations in pH of Coffee Bean Extract and Properties of Chlorogenic Acid Based on the Roasting Degree. Foods 2024, 13, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIczbiński, P.; Bukowska, B. Polifenoles Del Té y Del Café y Sus Propiedades Biológicas Según Las Últimas Investigaciones in Vitro. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 175, 114265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, R.D.; Trevisan, F.; de Vos, R.C.H. Coffee Berry and Green Bean Chemistry – Opportunities for Improving Cup Quality and Crop Circularity. Food Res. Int. 2022, 151, 110825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maksimowski, D.; Pachura, N.; Oziembłowski, M.; Nawirska-Olszańska, A.; Szumny, A. Coffee Roasting and Extraction as a Factor in Cold Brew Coffee Quality. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, K.; Gantner, M.; Tatarak, A.; Hallmann, E. The Content of Polyphenols in Coffee Beans as Roasting, Origin and Storage Effect. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Musa Özcan, M.; Uslu, N.; Salamatullah, A.M.; Hayat, K. Effect of Microwave and Oven Roasting Methods on Total Phenol, Antioxidant Activity, Phenolic Compounds, and Fatty Acid Compositions of Coffee Beans. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rangel, J.C.; Benavides, J.; Heredia, J.B.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A. The Folin–Ciocalteu Assay Revisited: Improvement of Its Specificity for Total Phenolic Content Determination. Anal. Methods 2013, 5, 5990–5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anese, M.; Manzocco, L.; Nicoli, M.C. Modeling the Secondary Shelf Life of Ground Roasted Coffee. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 5571–5576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, R.G. da; Vieira, T.M.F. de S. ; Lira, S.P. de Potential Antioxidant of Brazilian Coffee from the Region of Cerrado. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 38, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priftis, A.; Stagos, D.; Konstantinopoulos, K.; Tsitsimpikou, C.; Spandidos, D.A.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Tzatzarakis, M.N.; Kouretas, D. Comparison of Antioxidant Activity between Green and Roasted Coffee Beans Using Molecular Methods. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 7293–7302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Agostino, C.; Chillocci, C.; Polli, F.; Surace, L.; Simonetti, F.; Agostini, M.; Brutti, S.; Mazzei, F.; Favero, G.; Zumpano, R. Smartphone-Based Electrochemical Biosensor for On-Site Nutritional Quality Assessment of Coffee Blends. Molecules 2023, 28, 5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwiecki, K.; Nogala-Kałucka, M.; Polewski, K. Determination of Total Phenolic Compounds in Common Beverages Using CdTe Quantum Dots. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e12863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louzada Pereira, L.; Carvalho Guarçoni, R.; Soares De Souza, G.; Brioschi Junior, D.; Rizzo Moreira, T.; Schwengber Ten Caten, C. Propositions on the Optimal Number of Q-Graders and R-Graders. J. Food Qual. 2018, 2018, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kc, Y.; Parajuli, A.; Khatri, B.B.; Shiwakoti, L.D. Phytochemicals and Quality of Green and Black Teas from Different Clones of Tea Plant. J. Food Qual. 2020, 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, Q.T.M.; Tan, G.L.Y.; Loo, S.M.; Azhar, F.Z.; Menon, A.S.; Hii, C.L. The Drying Kinetics and Polyphenol Degradation of Cocoa Beans. J. Food Process Eng. 2016, 39, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak, A.; Gawlik-Dziki, U. The Study of Interactions between Active Compounds of Coffee and Willow ( Salix Sp.) Bark Water Extract. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, G.M.; Palomo-Ligas, L.; Nery-Flores, S.D.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Sáenz-Galindo, A.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; Zakaria, Z.A.; Aguilar, C.N.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R. Coffee Pulp as a Source for Polyphenols Extraction Using Ultrasound, Microwave, and Green Solvents. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2022, 32, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hečimović, I.; Belščak-Cvitanović, A.; Horžić, D.; Komes, D. Comparative Study of Polyphenols and Caffeine in Different Coffee Varieties Affected by the Degree of Roasting. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidayat, M.A.; Puspitaningtyas, N.; Gani, A.A.; Kuswandi, B. Rapid Test for the Determination of Total Phenolic Content in Brewed-Filtered Coffee Using Colorimetric Paper. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 3384–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husniati, H.; Oktiani, D. Chlorogenic Acid Isolation from Coffee as Affected by the Homogeneity of Cherry Maturity. Pelita Perkeb. 2019, 35, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktaviani, L.; Astuti, D.I.; Rosmiati, M.; Abduh, M.Y. Fermentation of Coffee Pulp Using Indigenous Lactic Acid Bacteria with Simultaneous Aeration to Produce Cascara with a High Antioxidant Activity. Heliyon 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severini, C.; Derossi, A.; Ricci, I.; Caporizzi, R.; Fiore, A. Roasting Conditions, Grinding Level and Brewing Method Highly Affect the Healthy Benefits of a Coffee Cup. Int J Clin Nutr Diet 2018, 4, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzejska, R.E.; Gielecińska, I.; Hallmann, E.; Wojda, B. Polyphenols vs. Caffeine in Coffee from Franchise Coffee Shops: Which Serving of Coffee Provides the Optimal Amount of This Compounds to the Body. Molecules 2024, 29, 2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Shen, J.; Silva, A.; Dennis, D.A.; Barrow, C.J. A Simple 96-Well Microplate Method for Estimation of Total Polyphenol Content in Seaweeds. J. Appl. Phycol. 2006, 18, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derossi, A.; Ricci, I.; Caporizzi, R.; Fiore, A.; Severini, C. How Grinding Level and Brewing Method (Espresso, American, Turkish) Could Affect the Antioxidant Activity and Bioactive Compounds in a Coffee Cup. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 3198–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustini, S.; Yusya, M.K. The Effect of Packaging Materials on the Physicochemical Stability of Ground Roasted Coffee. Curr. Res. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2020, 1, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamanu, E.; Gatea, F.; Pelinescu, D.R. Bioavailability and Bioactivities of Polyphenols Eco Extracts from Coffee Grounds after In Vitro Digestion. Foods 2020, 9, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawada, T. Estimated Dietary Polyphenol Intake and Major Food Sources. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 126, 1758–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariotti-Celis, M.S.; Martínez-Cifuentes, M.; Huamán-Castilla, N.; Vargas-González, M.; Pedreschi, F.; Pérez-Correa, J.R. The Antioxidant and Safety Properties of Spent Coffee Ground Extracts Impacted by the Combined Hot Pressurized Liquid Extraction–Resin Purification Process. Molecules 2018, 23, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehaya, F.M.; Mohammad, A.A. Thermostability of Bioactive Compounds during Roasting Process of Coffee Beans. Heliyon 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Hofmann, T. Quantitative Studies on the Formation of Phenol/2-Furfurylthiol Conjugates in Coffee Beverages toward the Understanding of the Molecular Mechanisms of Coffee Aroma Staling. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 4095–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantoush, Z.; Apostolovic, D.; Kravic, B.; Prodic, I.; Mihajlovic, L.; Stanic-Vucinic, D.; Cirkovic Velickovic, T. Green Tea Catechins of Food Supplements Facilitate Pepsin Digestion of Major Food Allergens, but Hampers Their Digestion If Oxidized by Phenol Oxidase. J. Funct. Foods 2012, 4, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, G.; Stepaniak, U.; Topor-Mądry, R.; Szafraniec, K.; Pająk, A. Estimated Dietary Intake and Major Food Sources of Polyphenols in the Polish Arm of the HAPIEE Study. Nutrition 2014, 30, 1398–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odžaković, B.; Džinić, N.; Kukrić, Z.; Grujić, S. Influence of Coffee Blends and Roasting Process on the Antioxidant Activity of Coffee. J. Eng. Process. Manag. 2019, 11, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, V.A.; Muthusamy, S. Mathematical Modeling and Kinetic Behavior of Indian Umblachery Cow Butter and Its Nutritional Degradation Analysis under Modified Atmospheric Packaging Technique. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, e14042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitton, R.; Berglin, M.; Elwing, H.; Colin, C.; Delage, L.; Potin, P.; Bianco-Peled, H. The Influence of Halide-Mediated Oxidation on Algae-Born Adhesives. Macromol. Biosci. 2007, 7, 1280–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anis, N.; Ahmed, D. Modelling and Optimization of Polyphenol and Antioxidant Extraction from Rumex Hastatus by Green Glycerol-Water Solvent According to Response Surface Methodology. Heliyon 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gago, B.; Lundberg, J.O.; Barbosa, R.M.; Laranjinha, J. Red Wine-Dependent Reduction of Nitrite to Nitric Oxide in the Stomach. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 43, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokić, S.; Velić, D.; Bilić, M.; Bucić-Kojić, A.; Planinić, M.; Tomas, S. Modelling of Solid-Liquid Extraction Process of Total Polyphenols from Soybeans. Czech J. Food Sci. 2010, 28, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, D.P. Kinetics of Ultrasound-Assisted Flavonoid Extraction from Agri-Food Solid Wastes Using Water/Glycerol Mixtures. Resources 2016, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijngaard, H.H.; Brunton, N. The Optimisation of Solid–Liquid Extraction of Antioxidants from Apple Pomace by Response Surface Methodology. J. Food Eng. 2010, 96, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bors, W.; Christa, M.; Stettmaier, K.; Yinrong, L.; L. Yeap, F. Antioxidant Mechanisms of Polyphenolic Caffeic Acid Oligomers, Constituents of Salvia Officinalis. Biol. Res. 2004, 37, 301–311. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, H.S.; El Azab, E.F. Efficacy of Green Coffee as an Antioxidant in Beef Meatballs Compared with Ascorbic Acid. Food Chem. X 2022, 14, 100336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psarra, C.; Gortzi, O.; Makris, D.P. Kinetics of Polyphenol Extraction from Wood Chips in Wine Model Solutions: Effect of Chip Amount and Botanical Species: Polyphenol Extraction from Wooden Chips in Wine Model. J. Inst. Brew. 2015, 121, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordevic, S.; Dordevic, D.; Danilović, B.; Tremlova, B.; Gablo, N. Development of Edible/Biodegradable Packaging Based on κ-Carrageenan with Spent Coffee Grounds as Active Additives. Adv. Technol. 2023, 12, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Li, L.; Bai, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Fu, Y.; Moyo, R. Extraction Optimization, Antioxidant Activity, and Tyrosinase Inhibitory Capacity of Polyphenols from Lonicera Japonica. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 1786–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simedru, D.; Becze, A. Complex Profiling of Roasted Coffee Based on Origin and Production Scale. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, A.R.; Park, K.W.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Han, J. Influence of Roasting Conditions on the Antioxidant Characteristics of Colombian Coffee (Coffea Arabica L.) Beans. J. Food Biochem. 2014, 38, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Days | Total polyphenol content (mg/L) | ||||||||

| T 40°C / HR 65% | |||||||||

| Green bean | Roasted bean | Ground roast | |||||||

| BT | BBFA | VE1 | VE2 | CC | BBSV | BBCV | BTCV | ||

| 0 | 113.250.02a | 117.610.01a | 109.890.01a | 106.110.00a | 109.180.02a | 113.310.09a | 102.250.02a | 107.870.01a | |

| 3 | 109.890.02a | 104.710.00b | 107.780.03a | 105.150.01ab | 102.610.01c | 105.820.02b | 101.900.00c | 105.300.03ab | |

| 6 | 106.200.01a | 104.010.01a | 107.250.02a | 103.010.03ab | 97.170.02d | 100.150.01c | 101.200.05bc | 104.890.02a | |

| 9 | 100.500.01b | 102.750.02a | 105.760.01a | 101.640.01b | 93.920.03d | 97.780.01c | 93.130.02d | 104.100.01a | |

| 12 | 98.310.01b | 91.030.02c | 102.340.02a | 81.030.02e | 92.630.02c | 92.690.02c | 91.550.01c | 101.290.01a | |

| Days | Total polyphenol content (mg/L) | ||||||||

| T 50°C / HR 65% | |||||||||

| Green bean | Roasted bean | Ground roast | |||||||

| BT | BBFA | VE1 | VE2 | CC | BBSV | BBCV | BTCV | ||

| 0 | 113.250.02a | 103.310.01c | 107.780.03b | 103.010.03c | 100.150.01d | 109.270.01b | 102.430.04c | 105.300.03c | |

| 2 | 101.290.01c | 102.750.02bc | 96.640.00e | 101.550.00c | 96.290.02e | 105.820.02a | 102.250.02bc | 104.010.03ab | |

| 4 | 91.290.00e | 98.570.02c | 95.150.01d | 94.970.01d | 94.100.01d | 91.820.02e | 100.760.02b | 102.250.03a | |

| 6 | 88.660.03d | 96.550.02b | 93.570.01c | 92.610.01c | 92.630.02c | 90.500.03d | 93.390.00c | 99.710.01a | |

| 8 | 80.680.02e | 91.990.04b | 92.080.01b | 81.030.01e | 91.550.01b | 86.820.03d | 90.850.03c | 92.780.03b | |

| Days | Total polyphenol content (mg/L) | |||||||

| T 60°C / HR 65% | ||||||||

| Green bean | Roasted bean | Ground roast | ||||||

| BT | BBFA | VE1 | VE2 | CC | BBSV | BBCV | BTCV | |

| 0 | 113.250.02a | 102.750.02c | 107.780.03b | 103.010.03c | 99.010.03d | 106.820.03b | 102.690.03c | 105.300.03bc |

| 1 | 106.200.01a | 92.080.04e | 95.240.03d | 95.680.01d | 98.750.02c | 105.820.02a | 102.250.02b | 94.540.01de |

| 2 | 101.380.02a | 84.450.00f | 93.310.02c | 86.730.03ef | 93.130.01cd | 102.170.04a | 93.480.02c | 83.310.01f |

| 3 | 81.550.01d | 79.450.03d | 89.540.01b | 83.570.05cd | 92.630.02a | 91.380.01a | 91.820.06a | 79.010.02d |

| 4 | 79.180.01c | 71.990.00d | 76.460.01c | 76.820.00c | 79.970.00c | 75.590.00c | 89.180.04a | 76.550.01c |

| Sample | Packaging | Order | Temperature | |||

| 40 °C | 50 °C | 60 °C | Selection | |||

|

Regression (R2) |

Regression (R2) |

Regression (R2) |

||||

| Green bean | BT | 0 | y = -1.309x + 113.48 (0.9858) | y = -3.8889x + 110.59 (0.9576) |

y = -9.2778x + 114.87 (0.9341) |

0 |

| 1 | y = -0.0124x + 4.733 (0.9849) |

y = -0.0406x + 4.7097 (0.9706) |

y = -0.098x + 4.7533 (0.9237) |

|||

| BBFA | 0 | y = -1.837x + 115.04 (0.8546) |

y = -1.4415x + 104.4 (0.9526) |

y = -7.4152x + 100.97 (0.9835) |

1 | |

| 1 | y = -0.018x + 4.7475 (0.8549) |

y = -0.0147x + 4.6494 (0.9486) |

y = -0.0859x + 4.6204 (0.9920) |

|||

| VE1 | 0 | y = -0.570x + 110.03 (0.9303) |

y = -1.7237x + 103.94 (0.763) |

y = -6.8333x + 106.13 (0.9200) |

0 | |

| 1 | y = -0.005x + 4.7011 (0.9261) |

y = -0.0174x + 4.643 (0.7781) |

y = -0.0748x + 4.6704 ( 0.9119) |

|||

| Roasted bean | VE2 | 0 | y = -1.7895x + 110.13 (0.6643) |

y = -2.6462x + 105.22 (0.9109) |

y = -6.4503x + 102.06 (0.9814) |

0 |

| 1 | y = -0.0191x + 4.7089 (0.6466) |

y = -0.0286x + 4.6609 (0.8929) |

y = -0.0722x + 4.6296 (0.9867) |

|||

| Ground roast | CC | 0 | y = -1.3928x + 107.46 (0.9369) |

y = -1.0424x + 99.114 ( 0.9356) |

y = -4.4181x + 101.54 (0.8184) |

1 |

| 1 | y = -0.0139x + 4.6777 (0.9457) |

y = -0.0109x + 4.5964 (0.9417) |

y = -0.0491x + 4.6246 (0.8003) |

|||

| BBSV | 0 | y = -1.6423x + 111.8 (0.9698) |

y = -3.0117x + 108.89 (0.9044) |

y = -7.6901x + 111.73 (0.8585) |

1 | |

| 1 | y = -0.016x + 4.7182 (0.9773) |

y = -0.0308x + 4.6922 (0.9108) |

y = -0.0838x + 4.7276 (0.8343) |

|||

| BBCV | 0 | y = -1.0058x + 104.04 (0.8365) |

y = -1.6009x + 104.34 (0.8713) |

y = -3.7456x + 103.38 (0.9101) |

0 | |

| 1 | y = -0.0104x + 4.6461 (0.8353) |

y = -0.0165x + 4.6492 (0.8692) |

y = -0.039x + 4.6394 (0.9151) |

|||

| BTCV | 0 | y = -0.4786x + 107.56 (0.9192) |

y = -1.4664x + 106.68 (0.8766) |

y = -7.3012x + 102.34 (0.9264) |

0 | |

| 1 | y = -0.0046x + 4.6782 (0.9181) |

y = -0.0148x + 4.6713 (0.8651) |

y = -0.0817x + 4.6306 (0.9421) |

|||

| Sample | Packaging | Ea (kJ/mol*K) | A0 | Arrhenius equation determined |

| Green bean | BT | 85.085 | 2.06E+14 | |

| BBFA | 59.714 | 1.22E+10 | ||

| VE1 | 107.67 | 4.82E+17 | ||

| Roasted bean | VE2 | 55.419 | 2.85E+09 | |

| Ground roast | CC | 49.321 | 1.75E+08 | |

| BBSV | 66.850 | 2.16E+11 | ||

| BBCV | 56.886 | 2.86E+09 | ||

| BTCV | 118.04 | 2.09E+19 |

| Sample | Packaging | Storage temperature (°C) | k (days-1) |

t1/2 order zero (months) |

| Green bean | BT | 15 | 0.0790631 | 23.87 |

| 20 | 0.1448005 | 13.04 | ||

| 25 | 0.2598701 | 7.26 | ||

| 30 | 1.3429945 | 1.41 | ||

| 40 | 3.6884747 | 0.51 | ||

| 60 | 9.5343346 | 0.20 | ||

| BBFA | 15 | 0.1844677 | 10.63 | |

| 20 | 0.2820690 | 6.95 | ||

| 25 | 0.4252168 | 4.61 | ||

| 30 | 1.3465856 | 1.46 | ||

| 40 | 2.7363711 | 0.72 | ||

| 60 | 5.3289017 | 0.37 | ||

| VE1 | 15 | 0.0149565 | 122.45 | |

| 20 | 0.0321659 | 56.94 | ||

| 25 | 0.0674234 | 27.16 | ||

| 30 | 0.5388931 | 3.40 | ||

| 40 | 1.9353609 | 0.95 | ||

| 60 | 6.4372803 | 0.28 | ||

| Roasted bean | VE2 | 15 | 0.2592307 | 6.82 |

| 20 | 0.3844649 | 4.60 | ||

| 25 | 0.5627154 | 3.14 | ||

| 30 | 1.6402242 | 1.08 | ||

| 40 | 3.1673386 | 0.56 | ||

| 60 | 5.8794484 | 0.30 | ||

| Ground roast | CC | 15 | 0.2026485 | 8.98 |

| 20 | 0.2877919 | 6.32 | ||

| 25 | 0.4039308 | 4.50 | ||

| 30 | 1.0466383 | 1.74 | ||

| 40 | 1.8799240 | 0.97 | ||

| 60 | 3.2600315 | 0.56 | ||

| BBSV | 15 | 0.1668885 | 11.32 | |

| 20 | 0.2684727 | 7.03 | ||

| 25 | 0.4250620 | 4.44 | ||

| 30 | 1.5448715 | 1.22 | ||

| 40 | 3.4168621 | 0.55 | ||

| 60 | 7.2057031 | 0.26 | ||

| BBCV | 15 | 0.1413287 | 12.11 | |

| 20 | 0.2118019 | 8.08 | ||

| 25 | 0.3131404 | 5.47 | ||

| 30 | 0.9389597 | 1.82 | ||

| 40 | 1.8450157 | 0.93 | ||

| 60 | 3.4813704 | 0.49 | ||

| BTCV | 15 | 0.0085808 | 209.52 | |

| 20 | 0.0198655 | 90.50 | ||

| 25 | 0.0447145 | 40.21 | ||

| 30 | 0.4365327 | 4.12 | ||

| 40 | 1.7730255 | 1.01 | ||

| 60 | 6.6204522 | 0.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).