2.1. Geographical and Geological Outline

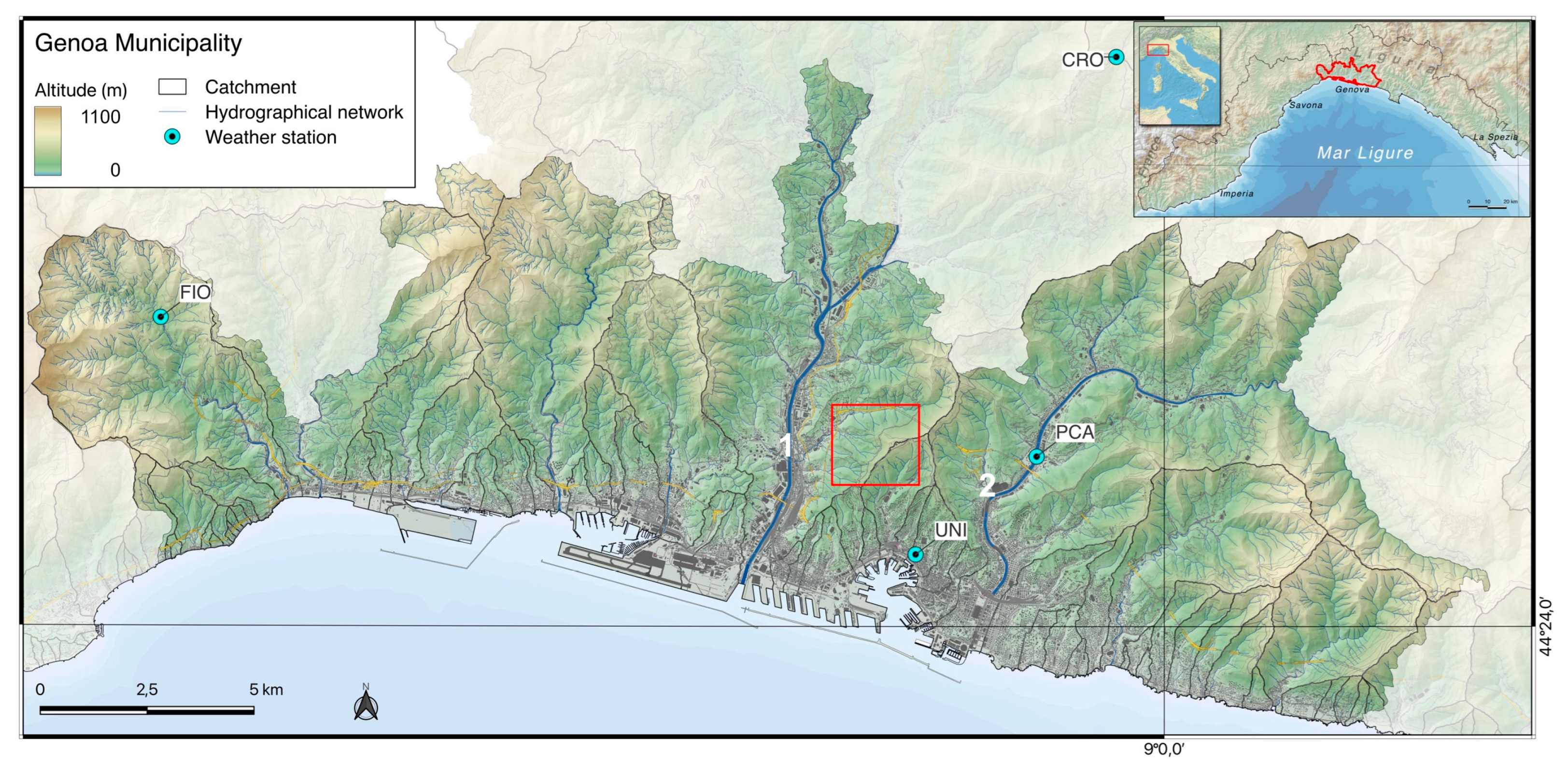

Genoa is a coastal city and the capital of Liguria region, located in the north-western Italian macro-region (

Figure 1); it extends over approximately 240 km

2, mostly distributed along a coastal strip stretching for 30 km from east to west (

Figure 1). Only subordinately the city also extends along the two main drainage axes that are orthogonal to the coastline: the Bisagno and Polcevera streams (

Figure 1), which limit the morphological amphitheater on which the historic city center has been built over time [

40].

The resident population of Genoa is about 560,000, but in the 1970s, when the industrial sector especially related to the port was at its peak, it reached 800,000. In that condition the urban planning had already foreseen a city of 1 million inhabitants.

The port area is one of the most important in the Mediterranean: it is the original settlement of the city and still today represents the main focus of industrial, commercial and transport activities. The extensive waterfront, which has been achieved by land filling and the consequent advancement of the coastline since historic times, clearly shows the anthropic transformations of the city that have occurred over the last 150 years due to the socio-economic growth and evolution.

From the administrative point of view, Genoa is divided into nine municipalities (Middle-East, Middle-West, Lower Bisagno Valley, Middle Bisagno Valley, Polcevera Valley, Middle-West, West, Middle-East, East) and 71 census sections. The population density reaches the highest values in the central part of the municipal area, particularly in the final stretch of the alluvial plain of the Bisagno stream, in the historical amphitheater behind the port area and near the mouth of the Polcevera stream. The highest value reaches 25,000 inhabitants/km2 in Marassi (Lower Bisagno Valley) at the east from the amphitheater in an area of high flood hazard, and west from it in Sampierdarena district (Middle West).

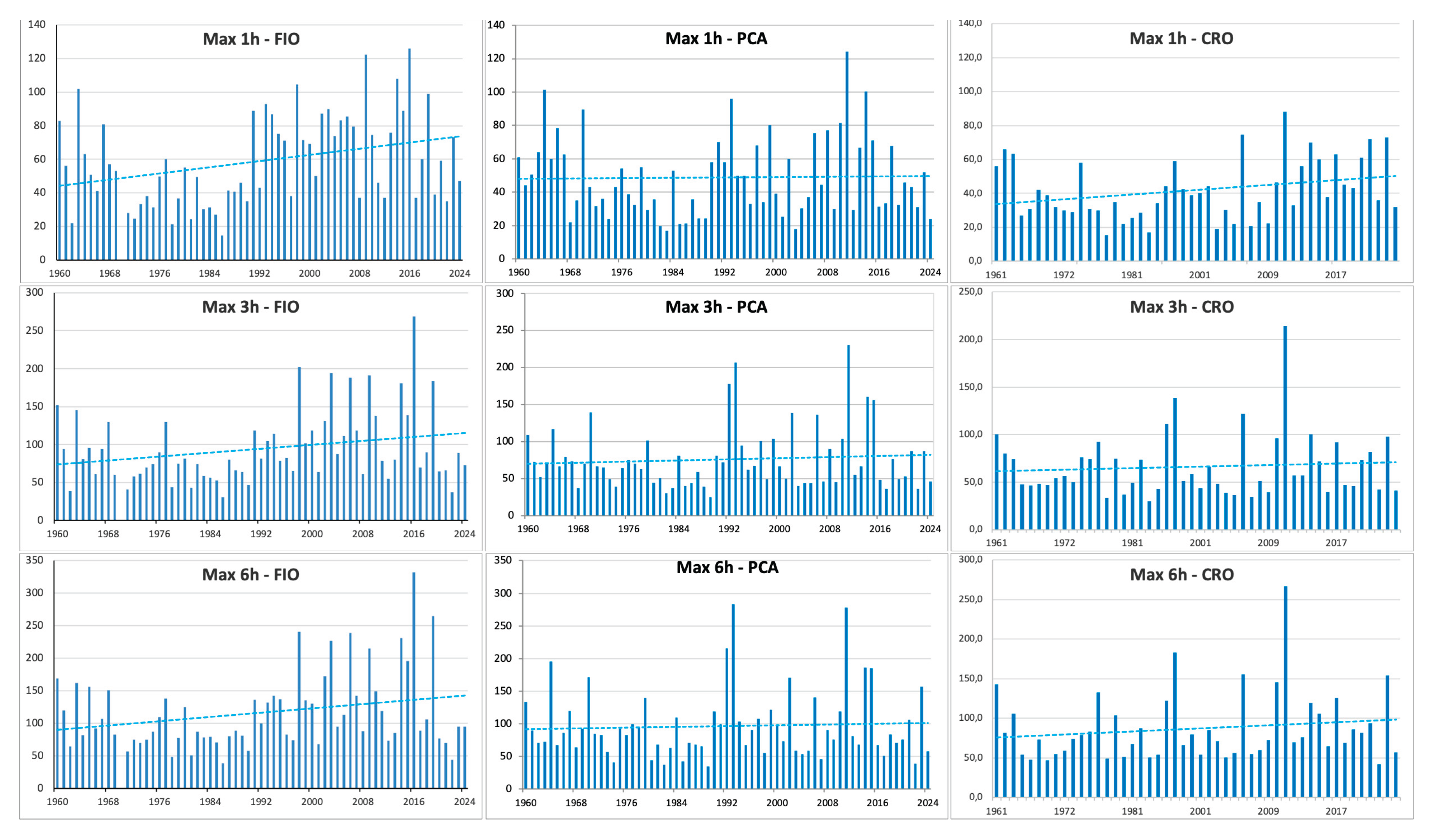

The physical-geographical features of Genoa are peculiar, both in terms of meteorological-climatic aspects and for the landscape. The meteo-climatic structure of Genoa is particular and has long been studied by researchers and meteorology experts. Due to its location at the northern apex of the western Mediterranean, in the late summer-autumn period the depression over the Gulf of Genoa is frequent, bringing intense and high intensity rainfall: the metropolitan city of Genoa in fact shows rainfall records at a Mediterranean scale. The highest values have been topped in occasion of the major flooding events: on 7-8 October 1970 (948 mm/24 h), 4 November 2011 (181 mm/h) and 4 October 2021 (883. 8 mm/24 h, 740.6/12h, 496 mm/6h and 377.8 mm/3h).

This last event, which was particularly intense, affected the hinterland to the west of the city but avoiding the municipal territory, causing many shallow landslides. During this event, the maximum values recorded over 12, 6 and 3 h exceeded the previous maximums that had been measured during the 1970 and 2011 phenomena.

On average, winters are mild and summers warm, with significant rainy periods in autumn and spring. The average annual rainfall is 1250 mm in the city center and varies significantly with altitude.

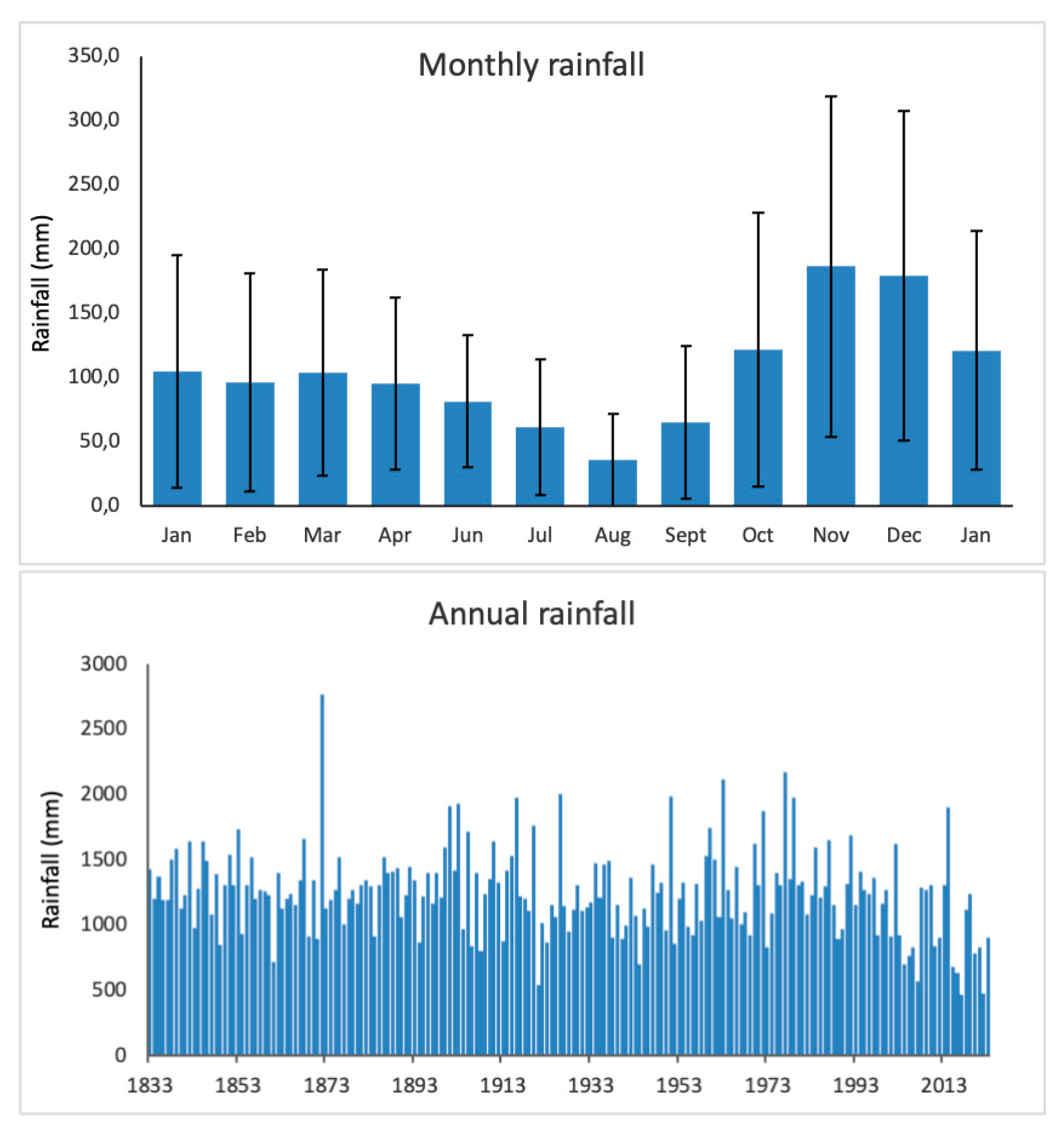

Figure 3 shows the average monthly values recorded at the Genoa University station, which has been operating since 1833. The higher value of the annual rainfall corresponds to some catastrophic events that occurred in the past, while the higher monthly values mainly occur in fall and, secondarily in spring.

Evidence of climate change in Genoa can be witnessed by an increase in the average annual air temperature and a decrease in the number of rainy days, resulting in an increase in the intensity of rainfall, leading to more frequent occurrences of floods and landslides [

41,

42]. Besides, proxies related to extreme rain events shows statistically significant increase over the period 1979-2019 [

43]. The last significant events occurred in December 2022 triggering a rock-fall that affected some buildings in the central-eastern sector of the city and in August 2023 when a very intense but highly concentrated rainfall in terms of space and time caused heavy ground effects in Genoa’s historic center [

44].

The Apennine Mountain range surrounds the city of Genoa with peaks reaching a maximum altitude of almost 1200 m in the eastern sector (Mt. Reixa, 1183) and over 1000 m in the eastern sector (Mt. Candelozzo, 1036 m). The area includes a large number of catchment basins mainly oriented perpendicular to the coastline. Not all the watersheds belong entirely to the municipality of Genoa: for example, both the upper Bisagno basin and the upper Polcevera one are included in other municipalities.

Based on the distance of the watershed from the coastline and the nature of the rock masses, slope gradients are generally high, especially in the eastern and western sectors of the municipal area (e.g., basins of the Nervi, Leira and Cerusa streams) where values above 50% are prevailing.

The morphometric and elevation features of the basins (

Figure 1) represent one of the most significant landslide factors, which results in a widespread hazard: during heavy rainfall, the reduced runoff time of small basins results in extremely rapid runoff (even less than 30’) and flash floods hit the floodplain resulting in high risk due to the high urbanization.

During flood events, often of flash flood type, shallow landslides are triggered and, depending on the morphological features of the territory, also debris-mudflows. These quickly moving masses cause a high hazard to the directly exposed elements such as buildings and infrastructure, and an indirect one related to the saturation of the culverts which are diffusively present in the urban area. The effects on the ground can be very serious and also include loss of life as well as substantial economic damage.

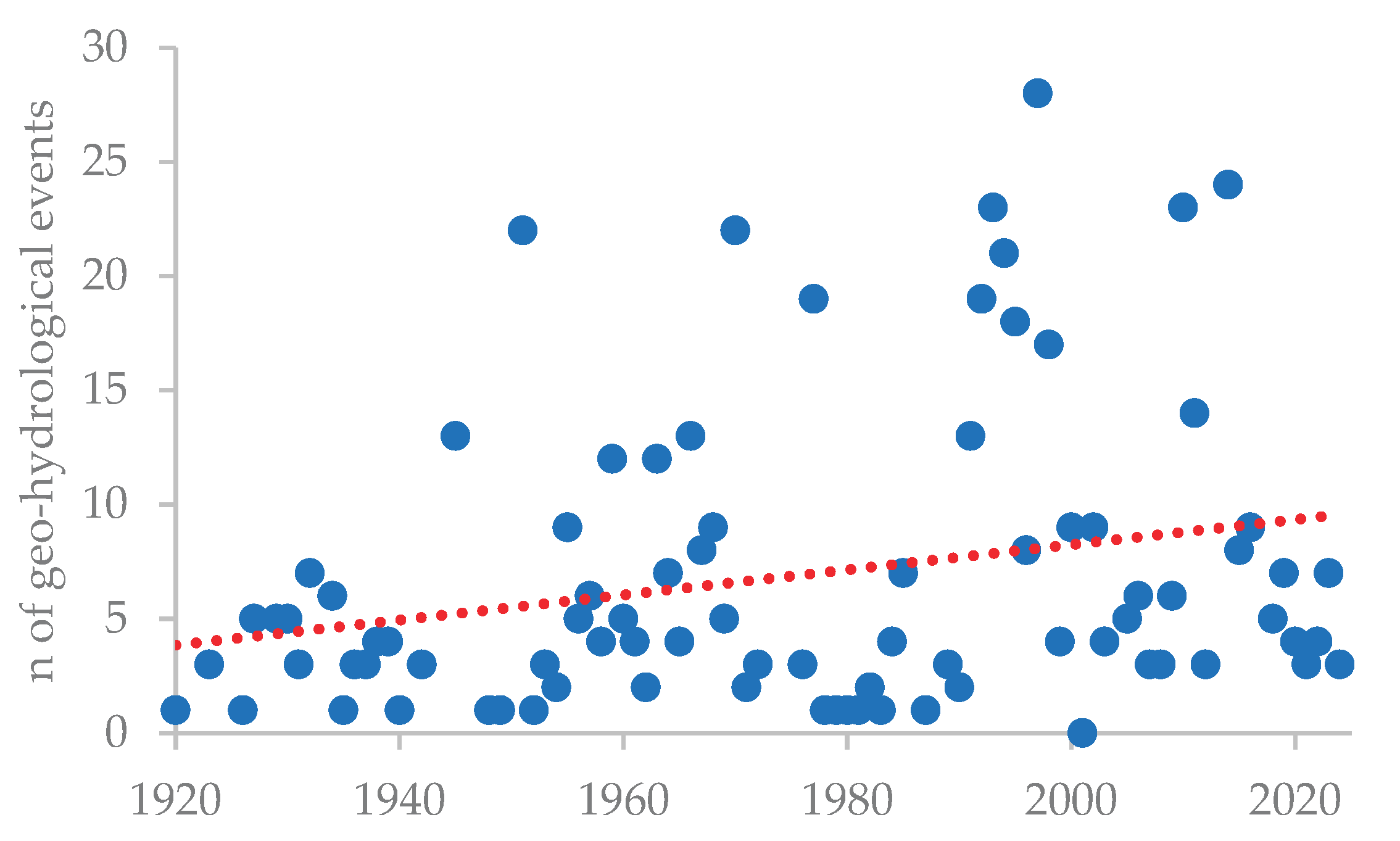

Table 1 shows the geo-hydrological hazard events that have characterized the Genoese territory in the last 100 years based on AVI project database [

59] properly updated.

The city of Genoa geologic features contribute substantially to the slope instability processes, then inducing the natural hazard:

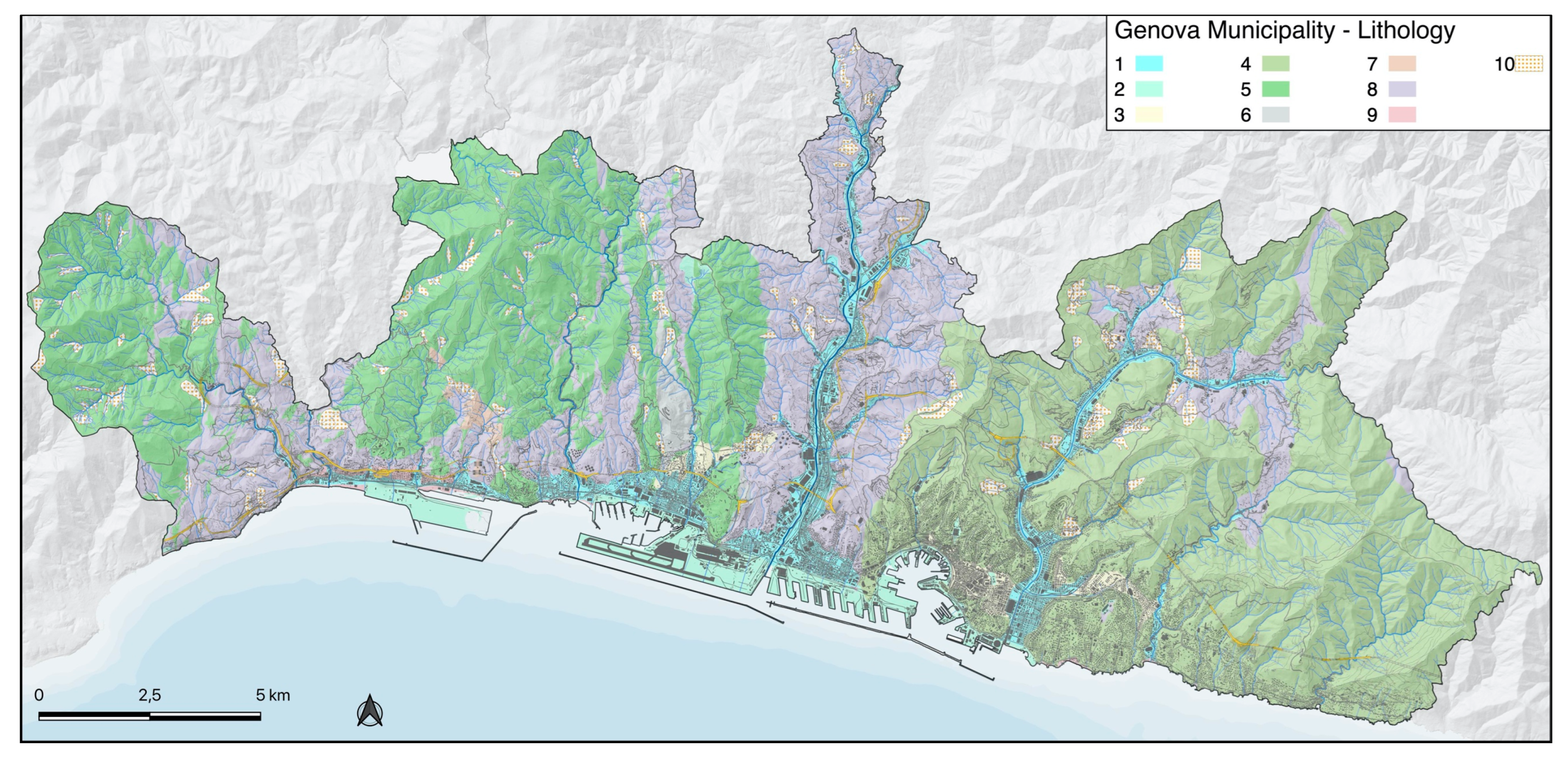

Figure 4 schematically shows the rock masses of the Genoa area, predominantly of sedimentary type in the East (limestone-marly flysch), and of ophiolitic type in the West (serpentinites and calcareous schist). The central sector is particularly complex and characterized by argillitic and siltitic flysch, basalts, and dolomites.

The geological history undergone by the rock formations, both ductile and brittle, and the consequent pattern of deformations occurred, together with the frequent coupling of geomaterials with different strength and deformability, is an additional predisposing element for slope instability and for triggering landslides characterized by different kinematics processes.

2.2. Research Methods

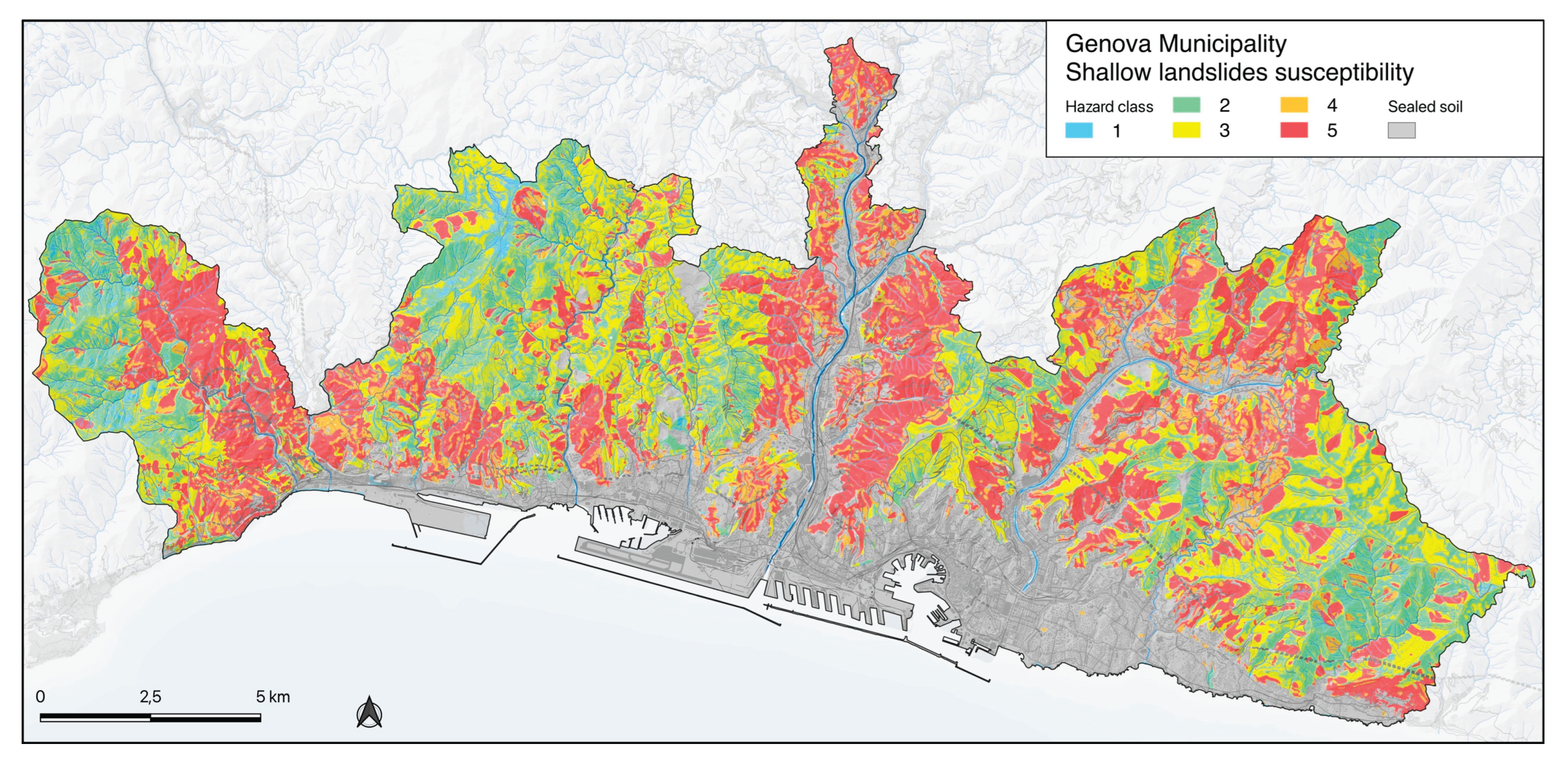

The susceptibility assessment for shallow landslides on the territory of the Municipality of Genoa was carried out by employing a semi-quantitative approach, which means combining a quantitative and a qualitative method. This approach makes it possible to combine numerical criteria with subjective analysis skills and experience. The objective component is based on descriptive statistics of census phenomena at the regional scale, while the subjective component is based on geomorphological analysis and evaluation.

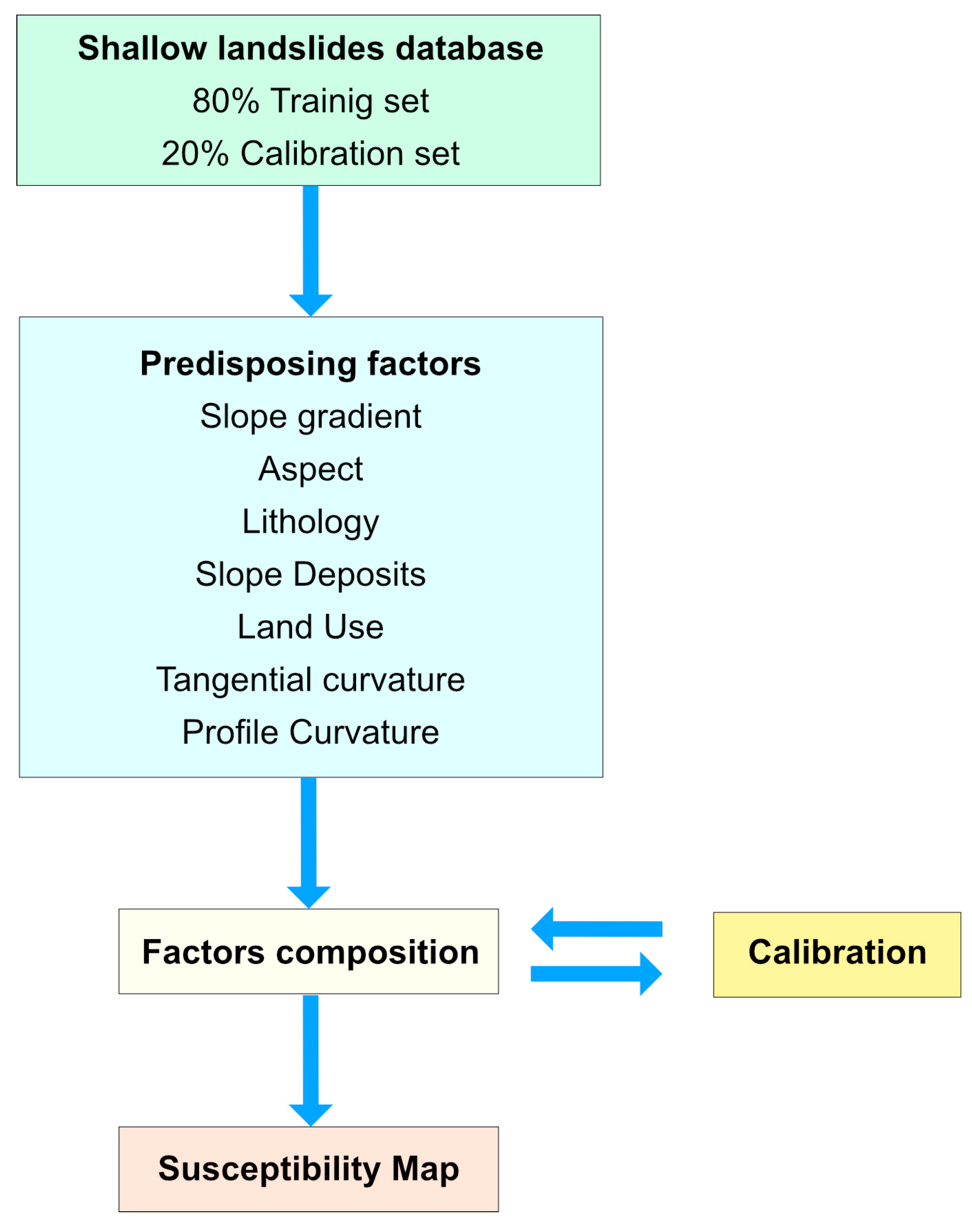

The method, schematized in

Figure 5, is based on identifying a set of descriptive parameters of the area as predisposing factors for the triggering of rapid runoff phenomena and related descriptive statistical evaluation. Then, the results of the descriptive statistics are assigned as weights to the different classes into which each predisposing factor has been divided, and the different factors are appropriately reclassified [

45].

The different factors are combined by means of other weights, the identification of which is done by applying the heuristic method AHP Analytic Hierarchy Process [

46,

47,

48,

49] by combining subjective evaluations by experts [

50,

51]. This methodology is a modified version of the one already proposed and tested in Mediterranean environment [

17] in a previous research. Further, the susceptibility analysis results are applied to the risk assessment of the gas and water distribution pipelines in the Genoa Municipality.

AHP is a semi-quantitative multi-criteria decision-support technique used to compare heterogeneous physical quantities and widely applied in natural hazard management [

52] and landslide susceptibility analysis [

6,

7,

17,

53,

54,

55,

56]. The assignment of weights to each identified factor and their subsequent normalized combination allowed to obtain a shallow landslide susceptibility map [

57,

58].

The basic data used is the inventory of landslide phenomena in Italy from the IFFI project, from data collected through the Copernicus system following the most recent intense events, and from data acquired by the governing authority of the basin plans involving the municipal area [

59]: from the combination of several geodatabases, 485 phenomena of rapid landslides and fast-developing shallow landslides that occurred in the municipal area were extracted.

The case history of such phenomena in Liguria and beyond is wide and increasing since the year 2000 [

43]: the events that occurred in western Liguria in 2000, the hundreds of shallow landslides triggered during the flash flood that affected the Cinque Terre/Vara Valley in 2011, the events of October/November 2014 in Genoa Province, and the landslide that in Leivi, in the hinterland 50 km east from Genoa, claimed two lives, the 2016 Lavina di Rezzo (Imperia) rapid flow and the 2019 landslides in Cava Lupara (Genoa), Cenova di Rezzo (Imperia) and Madonna del Monte (Savona) that caused the collapse of the viaduct along the A6 highway.

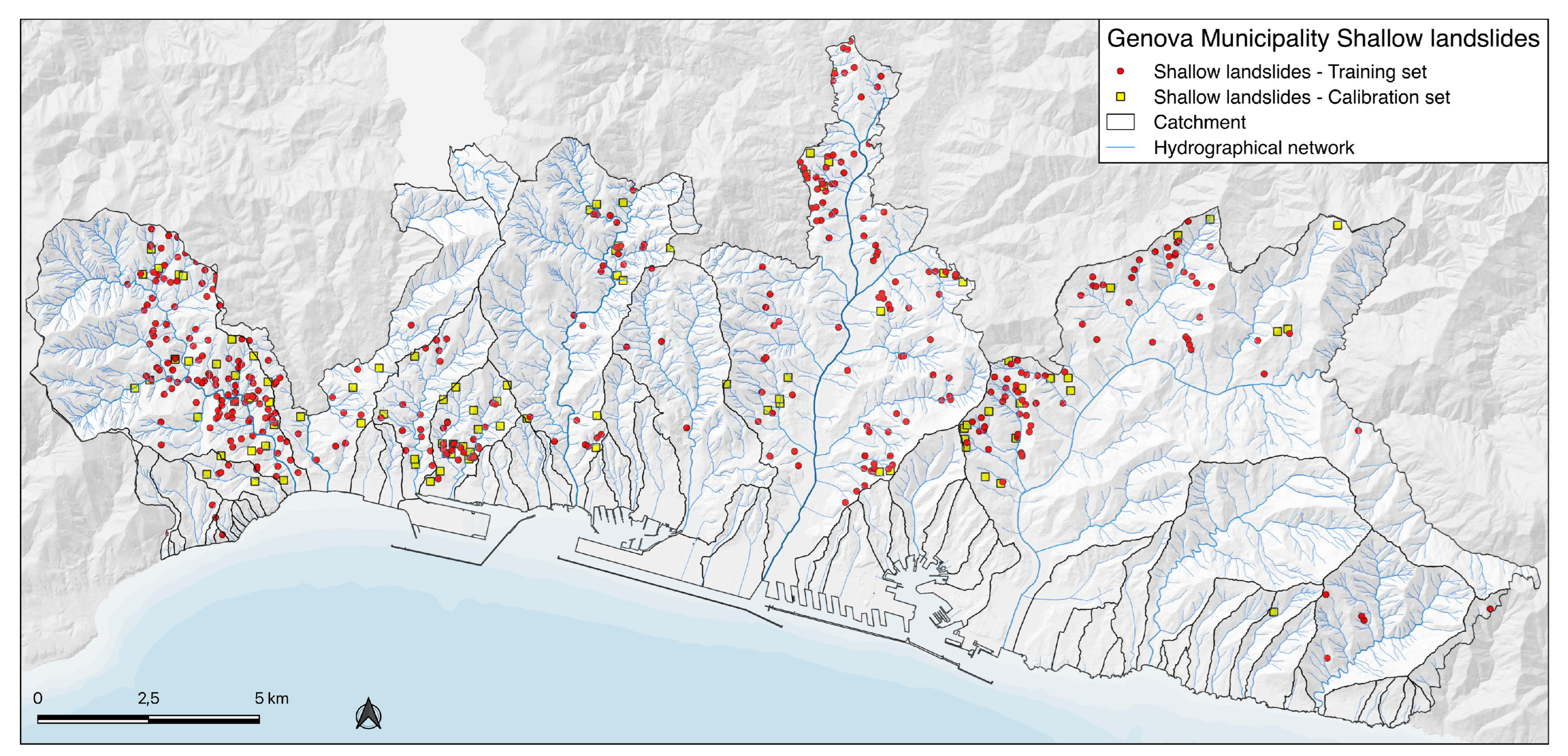

The set of census events at the municipal scale was divided by random extraction into two subsets: a training set of 388 phenomena accounting for 80 percent of the total and a calibration set of 97 phenomena accounting for the remaining 20 percent (

Figure 6).

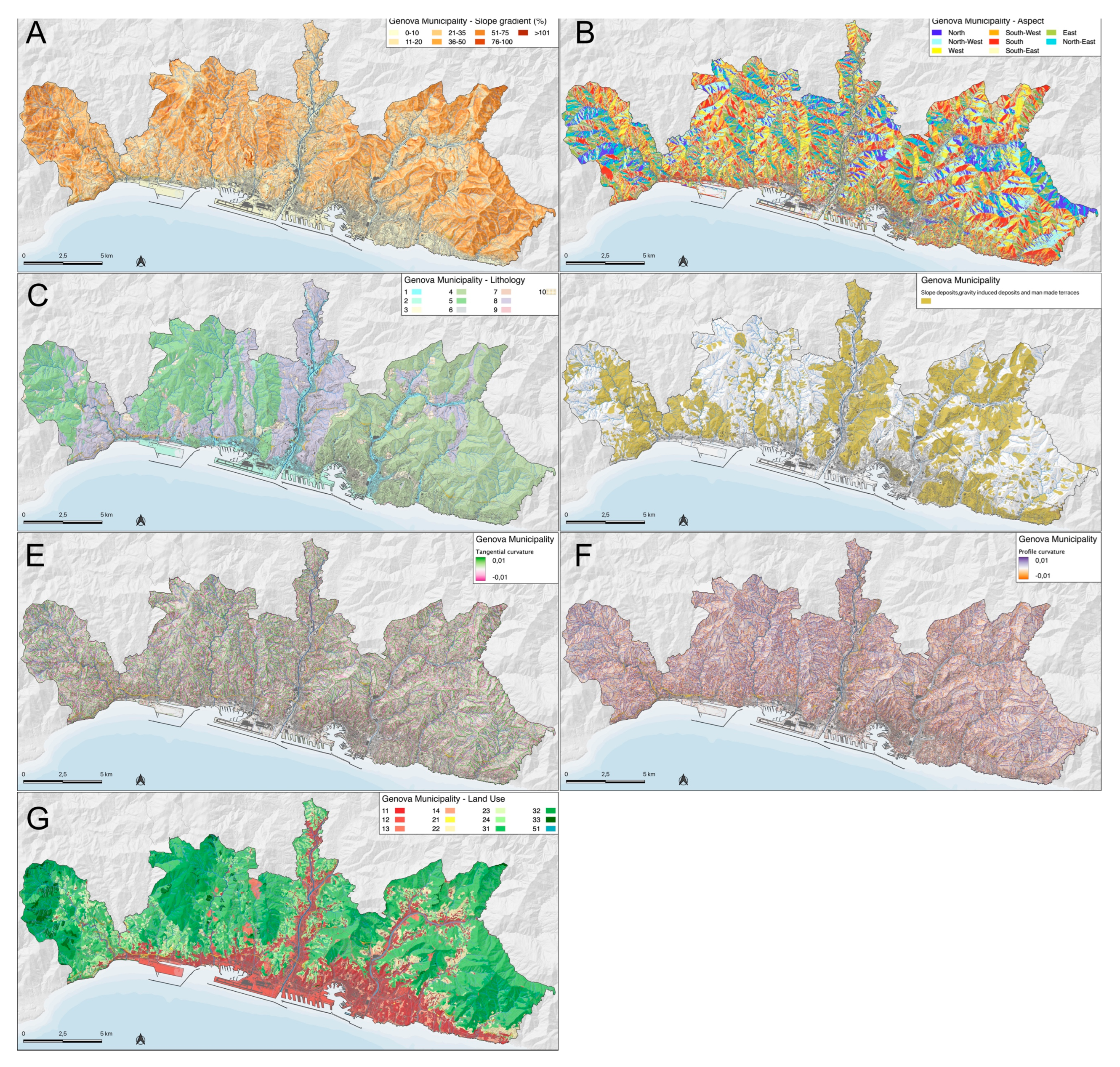

The first set has been used to obtain descriptive statistics of phenomena with respect to the seven identified predisposing factors (

Figure 7): slope gradient, slope aspect, lithology, land-use, planar curvature and tangential surface curvature, and presence of slope debris cover.

These data, whose characteristics are summarized in

Table 2, were partly obtained from the available data of regional databases at the scale 1:10,000, and partly obtained by application of processing algorithms to the 5 m mesh DTM made by the Region of Liguria. Debris covers are also considered to play a major role in terms of the probability of triggering shallow landslides. Therefore, basing on evidences of recent phenomena occurring in the area, it was decided to additionally include the slope cover factor in the analysis of shallow landslide susceptibility: this geomorphological data was obtained by composing the informative layer included in the geological map made by the Municipality of Genoa, with original field surveys and remote sensing analysis that allowed a more detailed recognition and mapping of the anthropogenic terraces widely spread in the Ligurian territory.

The presence of anthropogenic terraces has often been found to be crucial in triggering the phenomenon that have affected the region over the past 20 years. Their identification has been conducted through a dedicated analysis according to the methods identified in the same morpho-climatic environment [

60,

61,

62] in other researches. The analysis has been fulfilled using the DTM obtained from the ALS survey acquired by the Municipality of Genoa in 2018 with 1m resolution. The analysis is based on the computation of the SVF -Sky View Factor (SAGA GIS algorithm), whose reliability and accuracy was deemed satisfactory for the purposes at hand [

63].

The predisposing factors identification has been conducted according to the extensive bibliography available and allows the evaluation of both geological-morphological-morphometric characteristics and anthropogenic influence through land use. Descriptive statistics made it possible to objectively assign different weights to the relevant classes into which each factor has been divided. The weights in the combination of the seven factors were assigned by adapting the values obtained through the AHP technique developed and applied in recent research in a surrounding area [

17]. The weights between factors used are shown in

Table 3. The reliability of the result was subsequently verified by the calibration process, i.e., by checking the susceptibility classes corresponding to the 97 landslides in the calibration set.

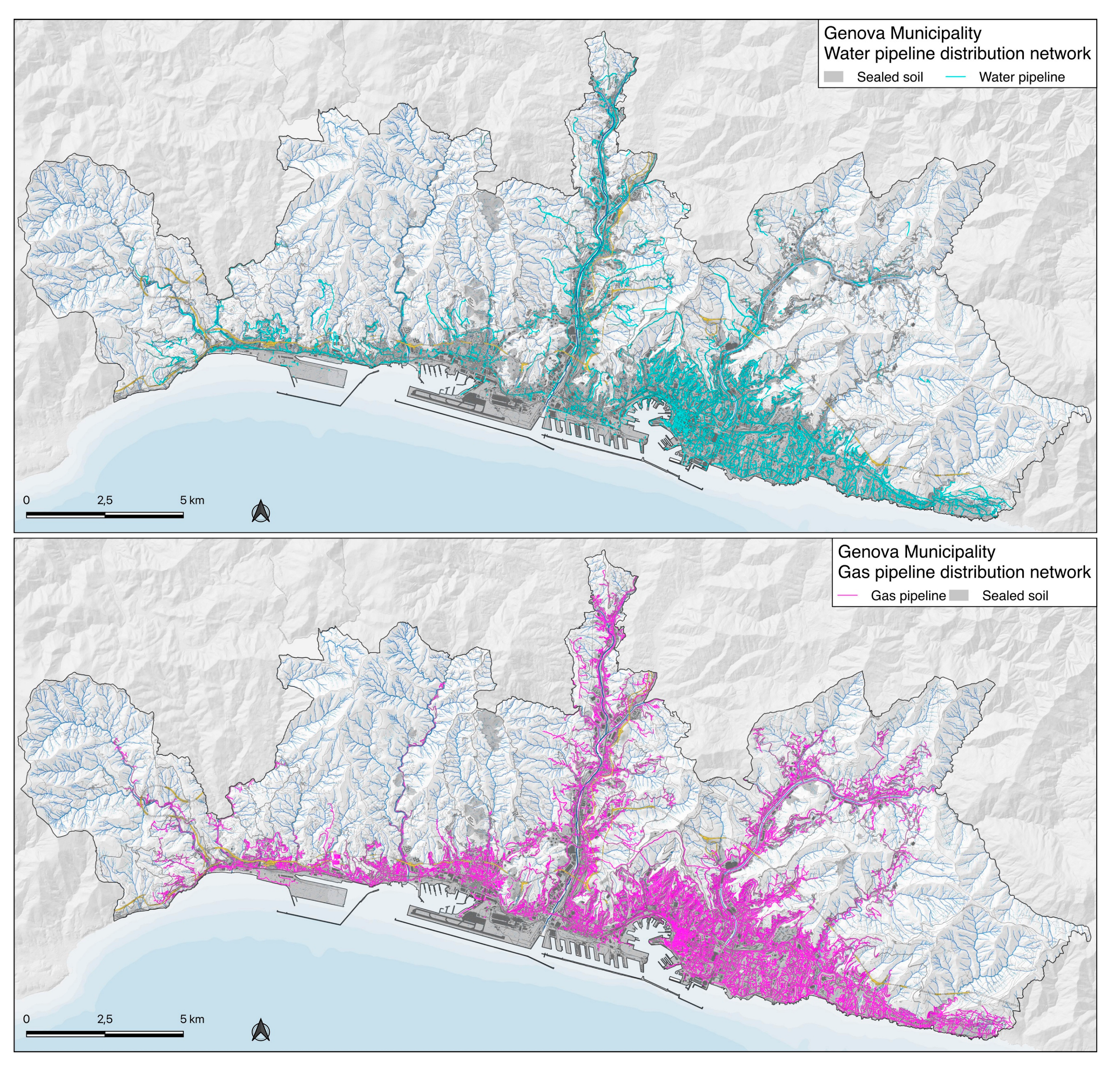

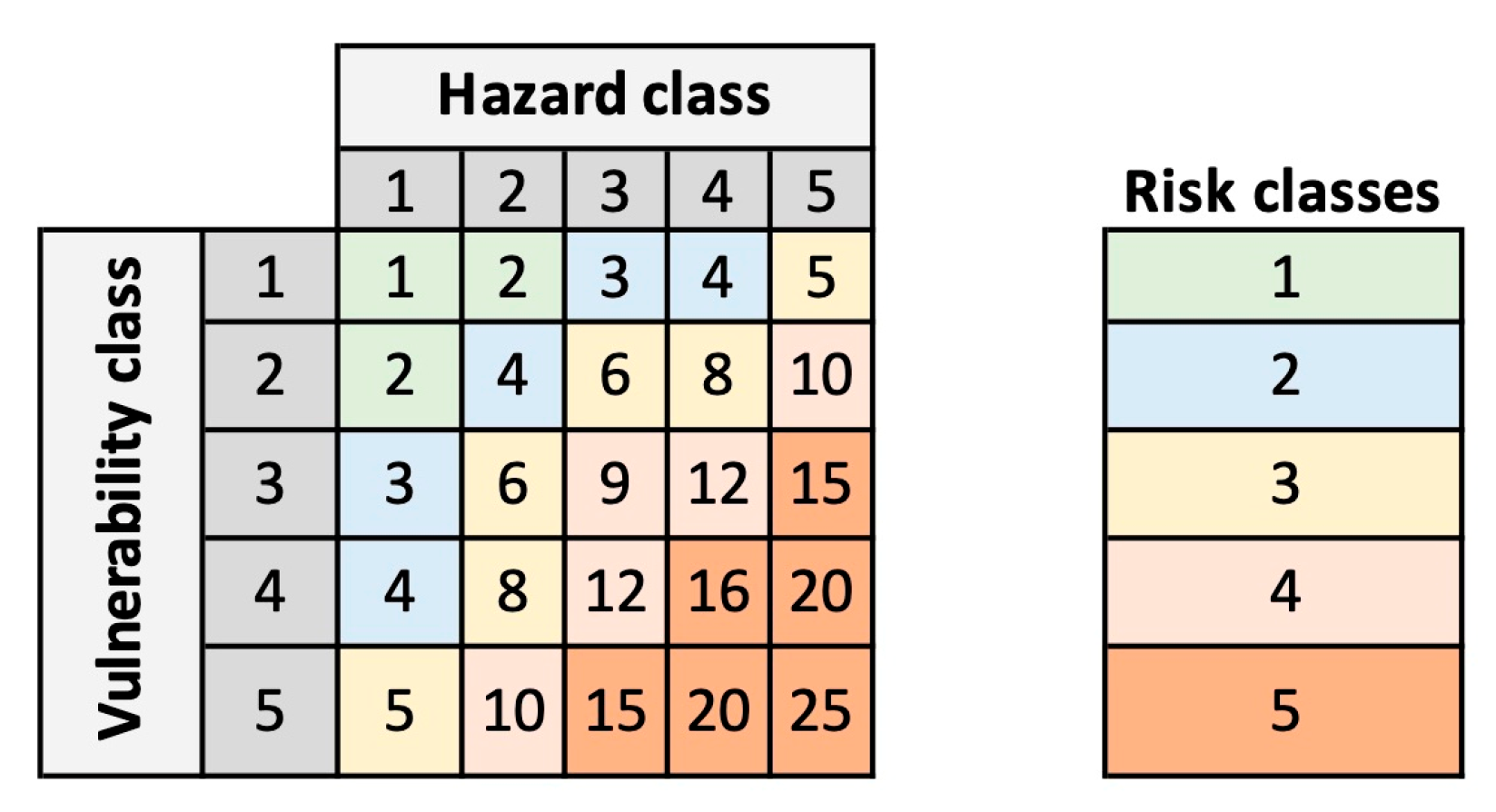

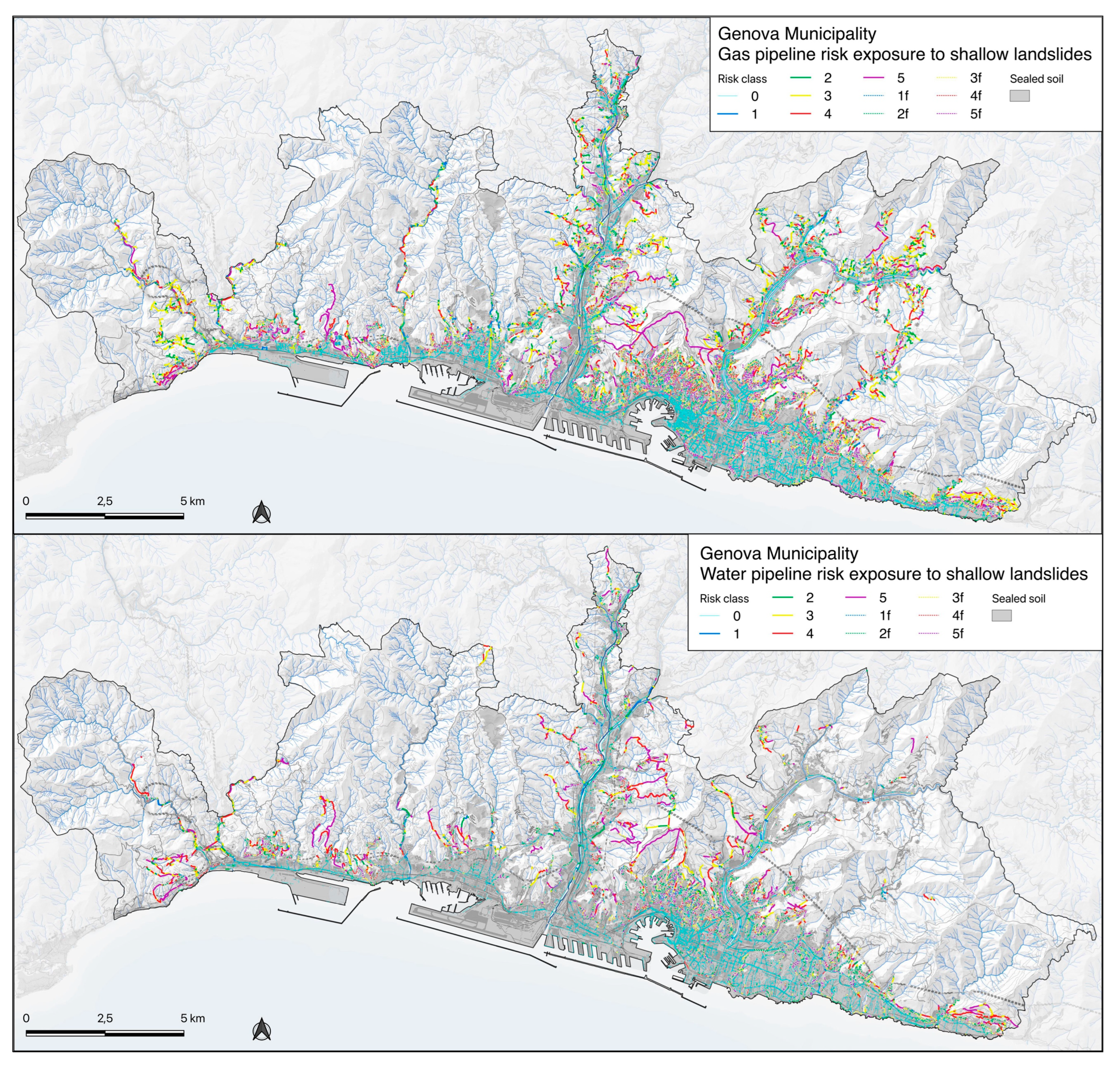

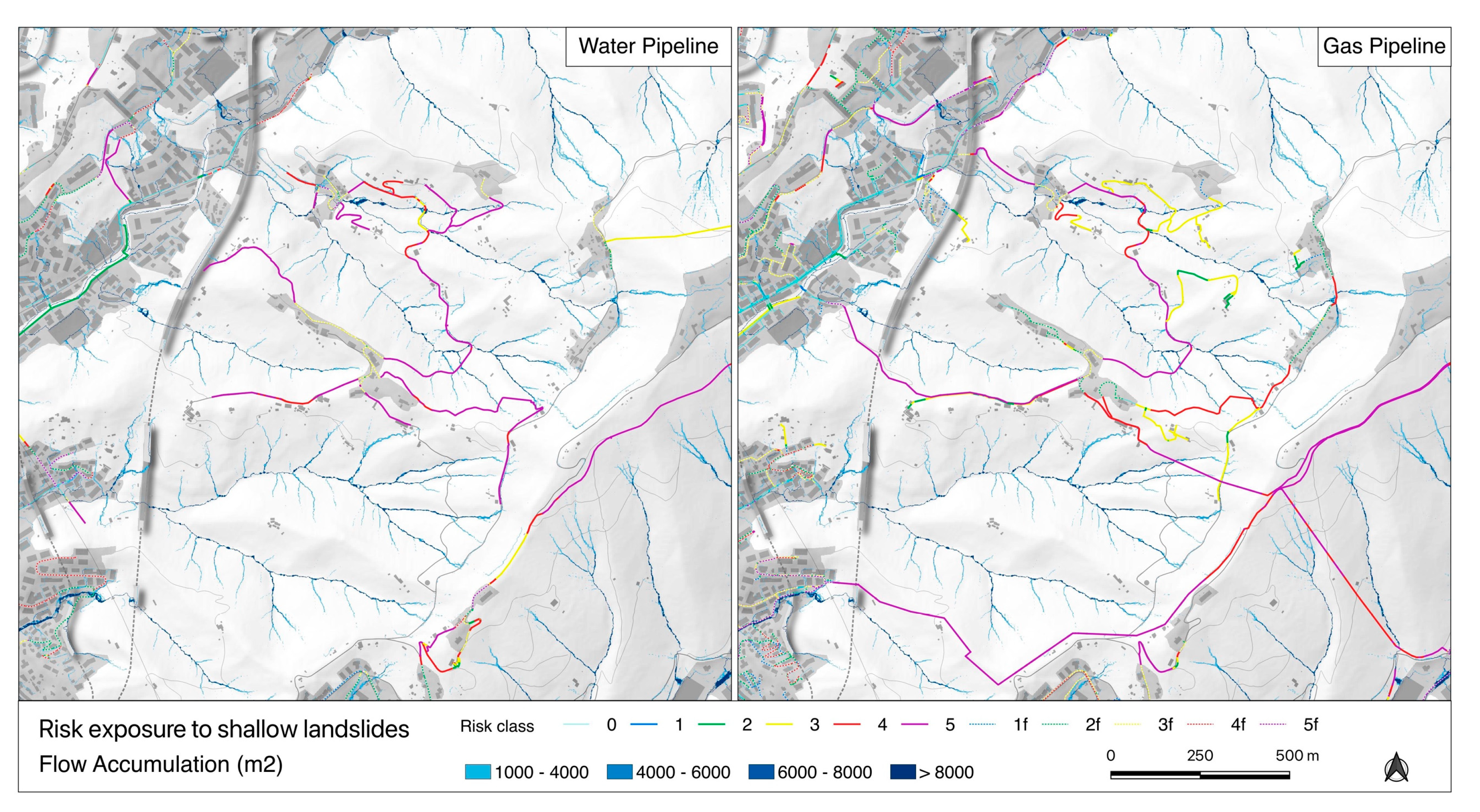

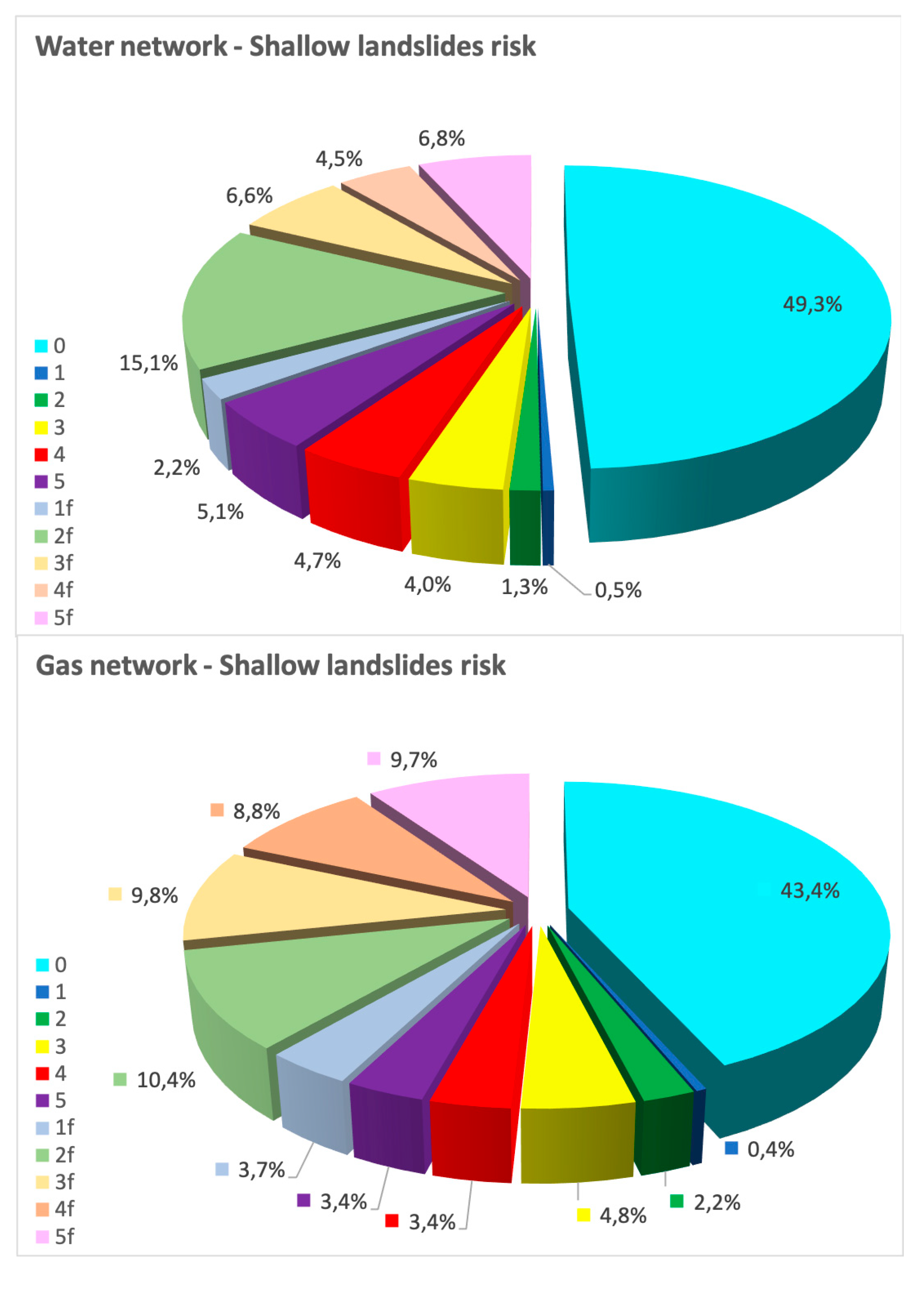

The risk assessment of the water and gas distribution networks has been approached evaluating the vulnerability of the twos through the local diameter of the pipes and then calculating the related risk [

64,

65,

66]. The following

Table 4 identifies the 5 vulnerability classes that have been defined according to the pipe’s diameters, which ranges from 10 to 900 cm for the water network, and from 15 to 800 cm for the gas one. Then, the 5 risk classes have been obtained combining the vulnerability classes with the hazard ones identified by the susceptibility computation: figures in the risk matrix have been obtained after the product of the hazard score and the vulnerability score. Finally, the results have been conservatively classified in the 5 risk classes in

Figure 8.