Submitted:

06 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Emerging Paradigm: From STEMI to Occlusion Myocardial Infarction

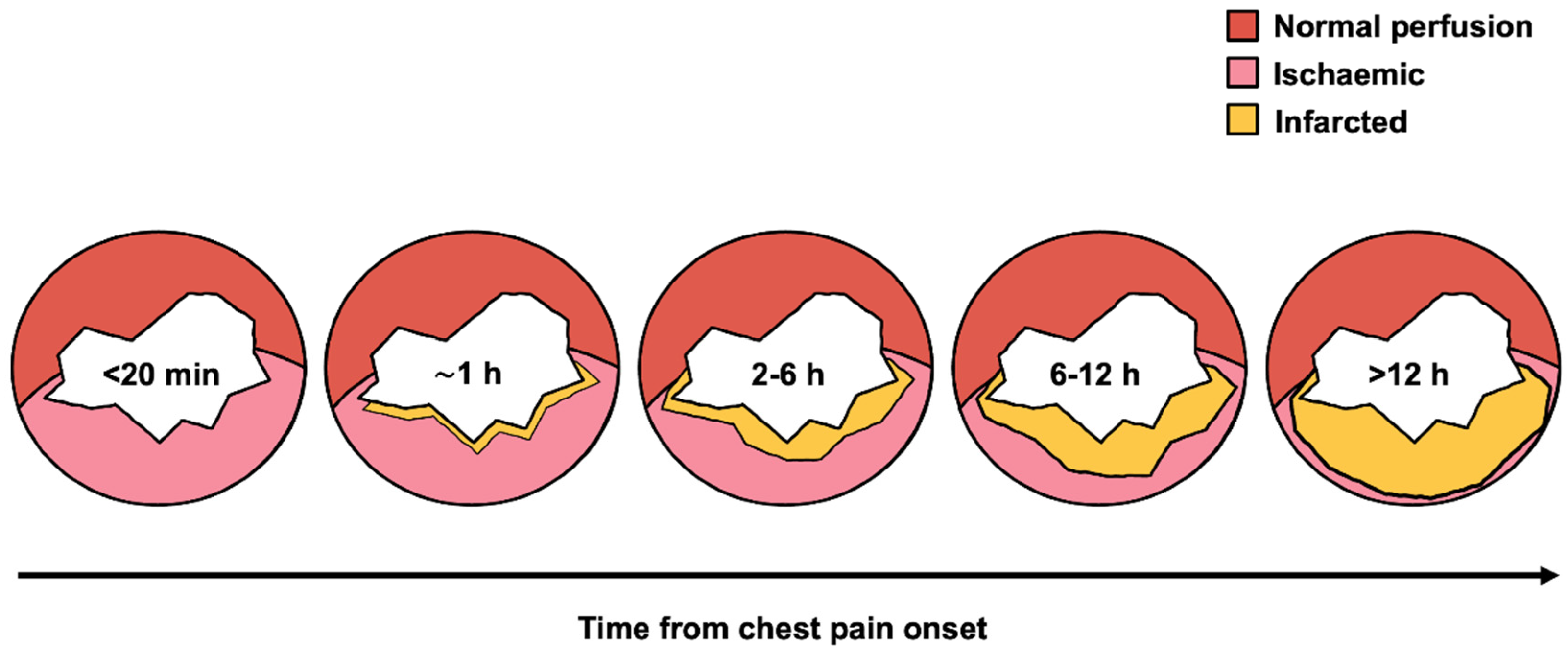

1.2. The “Time Is Muscle” Doctrine

1.3. Evolution of Reperfusion Strategies

2. Components and Determinants of Total Ischemic Time

2.1. Patient-Mediated Delays

- Sociodemographic factors: advanced age, female sex, rural residence, low education, social isolation, diabetes mellitus

- Cognitive factors: symptom misinterpretation, particularly with atypical presentations (dyspnea, sweating, non-chest pain) common in women, elderly, and diabetics

- Behavioral factors: initial contact with general practitioners instead of emergency medical services (EMS) activation; self-transport versus ambulance utilization

2.2. Pre-Hospital System Delays

2.3. In-Hospital System Delays

3. Clinical Consequences of Delayed Reperfusion

3.1. Mortality Impact

3.2. Myocardial Salvage and Infarct Size

3.3. Long-Term Morbidity

3.4. Magnified Impact in High-Risk Populations

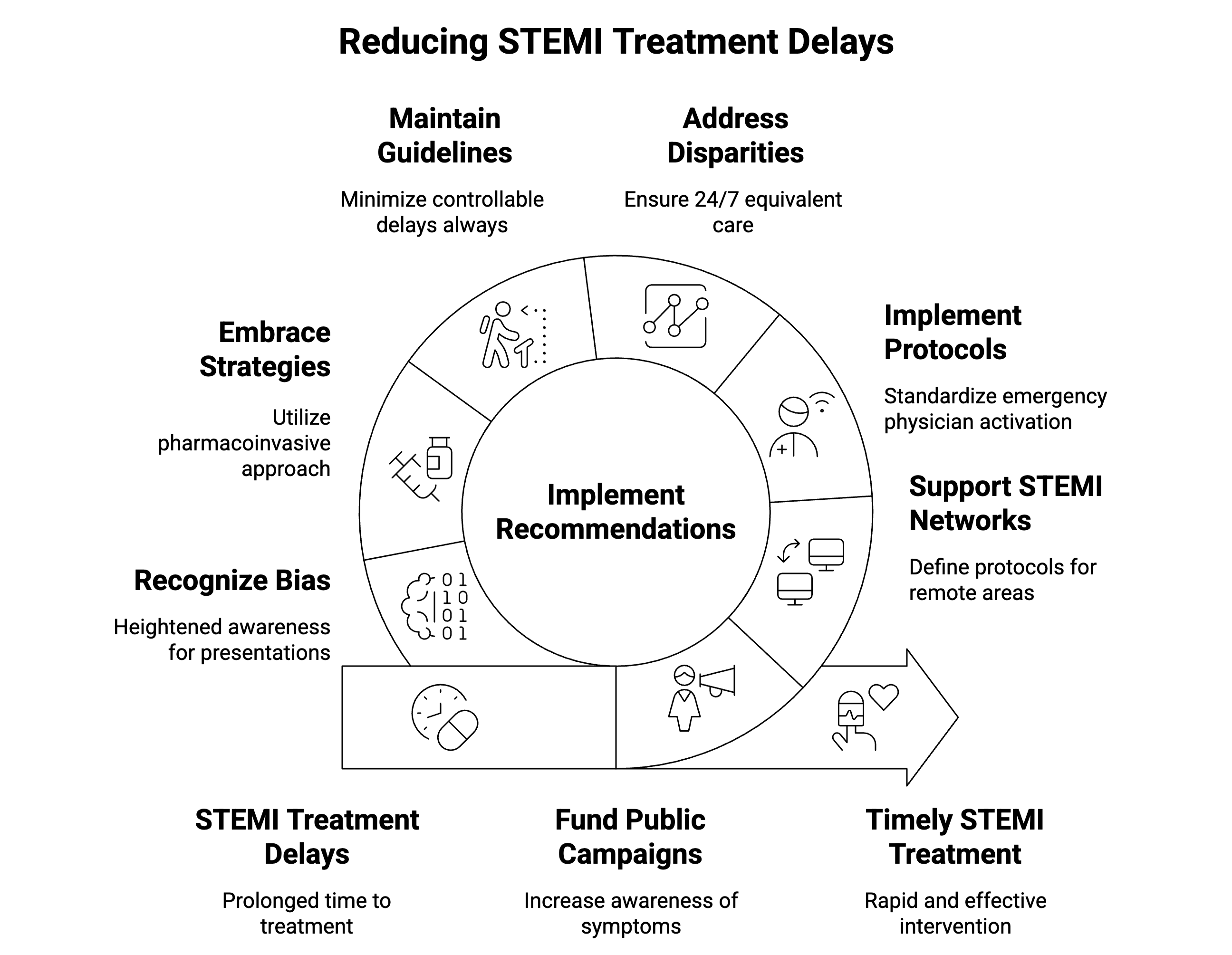

4. Evidence-Based Strategies to Mitigate Delay

4.1. Public Health Initiatives

4.2. Optimizing Pre-Hospital Care

- Pre-hospital ECG: As a Class I recommendation, pre-hospital ECG serves as a cornerstone intervention in acute MI management [1,2]. A systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated its association with substantial reductions in door-to-balloon time (mean difference >26 minutes) and significantly lower short-term mortality (odds ratio 0.72) [71]. The survival benefit is most pronounced in high-risk subgroups, including patients with cardiogenic shock or diabetes [72]. This finding reframes pre-hospital ECG beyond its role as a time-saving tool - it becomes a critical instrument for early risk stratification, enabling healthcare systems to preferentially accelerate care for the most vulnerable patients [1,2]. The “Stent - Save a Life!” initiative recognizes pre-hospital ECG as fundamental to effective STEMI networks [27].

- Regionalized networks: The “Stent - Save a Life!” initiative provides a structured methodology for establishing STEMI networks categorized by available resources: primary PCI networks (optimal), hub-and-spoke networks (acceptable long-term), pharmaco-invasive networks (transitional), and fibrinolysis networks (basic care requiring urgent upgrade) [1,2,27,73]. Direct transport protocols to PCI-capable centers significantly reduce mortality [75].

4.3. Streamlining In-Hospital Processes

- Emergency physician activation authority without cardiology consultation

- Single-call team notification systems

- 24/7 team availability within 20-30 minutes

- Regular performance feedback

4.4. Fibrinolysis and Pharmaco-Invasive Strategy

4.5. Upstream Glycoprotein IIb-IIIa Inhibitors

5. Persistent Challenges and Disparities

5.1. Geographic Disparities

5.2. Temporal Disparities

5.3. Demographic Disparities

- Women: Women with STEMI consistently present at older ages with greater comorbidity burdens, including diabetes and hypertension, which complicate their clinical presentation [36,107,108,109,110,111,112]. They more frequently experience atypical symptoms - shortness of breath, nausea, fatigue, and interscapular pain - leading to diagnostic and care-seeking delays [36,109]. These factors result in less timely reperfusion therapy and higher rates of in-hospital complications, including stroke and major bleeding, ultimately contributing to increased mortality compared with men [1,2,113].

- Racial/ethnic minorities: Black and Hispanic patients with STEMI face substantial disparities, experiencing lower odds of receiving timely, guideline-directed care such as prehospital ECGs and achieving door-to-balloon targets [114,115,116]. These populations consistently undergo invasive therapies like coronary angiography and PCI less frequently - a disparity that persists after adjusting for clinical and socioeconomic factors.

- Elderly: Older adults with STEMI experience particular vulnerability to systematic treatment delays, with the pre-hospital phase representing the most significant contributor [1,2,22,36,114,115,117]. These delays often stem from atypical presentations - confusion or weakness rather than chest pain - which patients and caregivers may attribute to other age-related conditions [118]. Even within established regionalized systems, elderly patients receive delayed reperfusion, partially explaining their elevated in-hospital mortality rates [1,2,118,119,120,121].

5.4. Challenges in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

6. Future Directions

6.1. Technological Innovation

- Artificial Intelligence: AI-ECG systems show promise for detecting not only classic STEMI but also subtle OMI patterns that traditional criteria often miss [8,9,125,126,127]. However, AI remains a promising yet unproven intervention facing substantial implementation hurdles. While many applications demonstrate strong performance in retrospective studies, prospective randomized controlled trials validating their safety and real-world impact on patient outcomes remain critically absent [128]. Implementation faces significant practical and ethical barriers. Practical challenges include high development costs, requirements for vast quantities of high-quality, unbiased training data, and the technical complexity of integrating AI tools with fragmented hospital IT systems [129]. Ethical and social challenges prove equally profound. Algorithmic bias may cause models to underperform in populations underrepresented in training data. Automation complacency risks clinicians over-relying on AI suggestions, while selective adherence may lead them to follow only recommendations that confirm pre-existing beliefs [129]. The “black box” problem of AI transparency and the need for clear accountability frameworks for AI-driven decisions must be addressed before widespread adoption [130]. Progress requires rigorous evaluation and cautious, ethically-grounded implementation - not merely technological advancement.

- Telemedicine: Real-time communication platforms between field crews and PCI centers reduce diagnostic uncertainty and optimize preparation [2,16,27]. Fifth-generation cellular technology provides the critical infrastructure for advanced mobile healthcare, offering robust communication pipeline which transforms ambulances into mobile diagnostic hubs, enabling high-definition video consultations and seamless transmission of large data files from paramedic-performed ultrasounds [131]. The technology allows expert-level clinical decision-making to begin at the patient’s bedside [132].

6.2. System Evolution

- Preparation: Establish task force and action plan with regional stakeholders

- Mapping: Identify PCI/non-PCI centers, assess transport times, confirm EMS availability

- Building: Assign roles based on available resources and network type

- Quality Assessment: Monitor key performance indicators continuously

6.3. Research Priorities

- Optimal timing for pharmaco-invasive PCI (2-24 hour window) and new subcutaneaous upstream antithrombotic therapies

- Effective public awareness campaign design

- Targeted interventions for persistent disparities

- Prospective validation of AI technologies

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | American College of Cardiology |

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ED | Emergency department |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| EMS | Emergency medical services |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| FMC | First medical contact |

| GP | Glycoprotein |

| MI | Myocardial infarction |

| NOMI | Non-occlusion myocardial infarction |

| NSTEMI | Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction |

| OMI | Occlusion myocardial infarction |

| PCI | Percutaneous coronary intervention |

| PPCI | Primary percutaneous coronary intervention |

| SCAI | Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions |

| STEMI | ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction |

| TIMI | Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (flow grade) |

References

- Rao, S.V.; O’Donoghue, M.L.; Ruel, M.; Rab, T.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Alexander, J.H.; Baber, U.; Baker, H.; Cohen, M.G.; Cruz-Ruiz, M.; et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2025, 151, e771–e862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.-A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, T.; West, N.E.; El-Omar, M. ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Clin. Med. Lond. Engl. 2016, 16, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, K.A.; Lowe, J.E.; Rasmussen, M.M.; Jennings, R.B. The Wavefront Phenomenon of Ischemic Cell Death. 1. Myocardial Infarct Size vs Duration of Coronary Occlusion in Dogs. Circulation 1977, 56, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroko, P.R. Editorial: Assessing Myocardial Damage in Acute Infarcts. N. Engl. J. Med. 1974, 290, 158–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Brener, S.J.; Mehran, R.; Lansky, A.J.; McLaurin, B.T.; Cox, D.A.; Cristea, E.; Fahy, M.; Stone, G.W. Implications of Pre-Procedural TIMI Flow in Patients with Non ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Revascularization: Insights from the ACUITY Trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyad, M.; Albandak, M.; Gala, D.; Alqeeq, B.; Baniowda, M.; Pally, J.; Allencherril, J. Reevaluating STEMI: The Utility of the Occlusive Myocardial Infarction Classification to Enhance Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2025, 27, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, W.H.; McLaren, J.T.T.; Meyers, H.P.; Smith, S.W. Occlusion Myocardial Infarction: A Revolution in Acute Coronary Syndrome. Postepy W Kardiologii Interwencyjnej Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2025, 21, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, J.; de Alencar, J.N.; Aslanger, E.K.; Meyers, H.P.; Smith, S.W. From ST-Segment Elevation MI to Occlusion MI: The New Paradigm Shift in Acute Myocardial Infarction. JACC Adv. 2024, 3, 101314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R.; Golwala, H.; Tripathi, A.; Bin Abdulhak, A.A.; Bavishi, C.; Riaz, H.; Mallipedi, V.; Pandey, A.; Bhatt, D.L. Impact of Total Occlusion of Culprit Artery in Acute Non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 3082–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gołąbek, N.; Jakubowski, W.; Król, S.; Kozioł, M.; Niewiara, Ł.; Kleczyński, P.; Legutko, J.; Dziewierz, A.; Surdacki, A.; Chyrchel, M. ECG Patterns Suggestive of High-Risk Coronary Anatomy in Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome – an Analysis of Real-World Patients. Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2023, 19, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzeciak, P.; Tajstra, M.; Wojakowski, W.; Cieśla, D.; Kalarus, Z.; Milewski, K.; Hrapkowicz, T.; Mizia-Stec, K.; Smolka, G.; Nadolny, K.; et al. Temporal Trends in In-Hospital Mortality of 7 628 Patients with Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Cardiogenic Shock Treated in the Years 2006–2021. An Analysis from the SILCARD Database. Pol. Heart J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leader, J.H.; Kanji, R.; Gorog, D.A. Spontaneous Reperfusion in STEMI: Its Mechanisms and Possible Modulation. Pol. Heart J. 2024, 82, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.C.; Ahn, Y. False Positive ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Korean Circ. J. 2013, 43, 368–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalas, K.; Kuliczkowski, W.; Pachana, J.; Mycka, R.; Rakoczy, B. Is ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Always a Simple Diagnosis? Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2023, 19, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.V. The 2025 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Acute Coronary Syndrome Guideline: A Personal Perspective. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 85, 2068–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvain, J.; Rakowski, T.; Lattuca, B.; Liu, Z.; Bolognese, L.; Goldstein, P.; Hamm, C.; Tanguay, J.-F.; Ten Berg, J.; Widimsky, P.; et al. Interval From Initiation of Prasugrel to Coronary Angiography in Patients With Non–ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewierz, A.; De Luca, G.; Rakowski, T. Every Minute of Delay (Still) Counts! Postepy W Kardiologii Interwencyjnej Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2025, 21, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroko, P.R.; Kjekshus, J.K.; Sobel, B.E.; Watanabe, T.; Covell, J.W.; Ross, J.; Braunwald, E. Factors Influencing Infarct Size Following Experimental Coronary Artery Occlusions. Circulation 1971, 43, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windecker, S.; Bax, J.J.; Myat, A.; Stone, G.W.; Marber, M.S. Future Treatment Strategies in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. The Lancet 2013, 382, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siudak, Z.; Hawranek, M.; Kleczyński, P.; Bartuś, S.; Kusa, J.; Milewski, K.; Opolski, M.P.; Pawłowski, T.; Protasiewicz, M.; Smolka, G.; et al. Interventional Cardiology in Poland in 2022. Annual Summary Report of the Association of Cardiovascular Interventions of the Polish Cardiac Society (AISN PTK) and Jagiellonian University Medical College. Postepy W Kardiologii Interwencyjnej Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2023, 19, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riehle, L.; Gothe, R.M.; Ebbinghaus, J.; Maier, B.; Bruch, L.; Röhnisch, J.-U.; Schühlen, H.; Fried, A.; Stockburger, M.; Theres, H.; et al. Implementation of the ESC STEMI Guidelines in Female and Elderly Patients over a 20-Year Period in a Large German Registry. Clin. Res. Cardiol. Off. J. Ger. Card. Soc. 2023, 112, 1240–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siudak, Z.; Grygier, M.; Tomaniak, M.; Kałużna-Oleksy, M.; Kleczyński, P.; Milewski, K.; Opolski, M.P.; Smolka, G.; Sabiniewicz, R.; Malinowski, K.P.; et al. Interventional Cardiology in Poland in 2023. Annual Summary Report of the Association of Cardiovascular Interventions of the Polish Cardiac Society (AISN PTK) and Jagiellonian University Medical College. Postepy W Kardiologii Interwencyjnej Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2024, 20, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Hong, Y.J.; Ahn, Y.; Jeong, M.H. Past, Present, and Future of Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2023, 2, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.D.; Van De Werf, F.J.J. Thrombolysis for Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 1998, 97, 1632–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeley, E.C.; Boura, J.A.; Grines, C.L. Primary Angioplasty versus Intravenous Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Quantitative Review of 23 Randomised Trials. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2003, 361, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candiello, A.; Alexander, T.; Delport, R.; Toth, G.G.; Ong, P.; Snyders, A.; Belardi, J.A.; Lee, M.K.Y.; Pereira, H.; Mohamed, A.; et al. How to Set up Regional STEMI Networks: A “Stent - Save a Life!” Initiative. EuroIntervention J. Eur. Collab. Work. Group Interv. Cardiol. Eur. Soc. Cardiol. 2022, 17, 1313–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleczyński, P.; Siudak, Z.; Dziewierz, A.; Tokarek, T.; Rakowski, T.; Legutko, J.; Bartuś, S.; Dudek, D. The Network of Invasive Cardiology Facilities in Poland in 2016 (Data from the ORPKI Polish National Registry). Kardiol. Pol. 2018, 76, 805–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januś, B.; Rakowski, T.; Dziewierz, A.; Fijorek, K.; Sokołowski, A.; Dudek, D. Effect of Introducing a Regional 24/7 Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Service Network on Treatment Outcomes in Patients with ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Kardiol. Pol. 2015, 73, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, D.; Dziewierz, A.; Siudak, Z.; Rakowski, T.; Zalewski, J.; Legutko, J.; Mielecki, W.; Janion, M.; Bartus, S.; Kuta, M.; et al. Transportation with Very Long Transfer Delays (>90 Min) for Facilitated PCI with Reduced-Dose Fibrinolysis in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010, 139, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertero, E.; Popoiu, T.-A.; Maack, C. Mitochondrial Calcium in Cardiac Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury and Cardioprotection. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2024, 119, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, G.M.; Meier, P.; White, S.K.; Yellon, D.M.; Hausenloy, D.J. Myocardial Reperfusion Injury: Looking beyond Primary PCI. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 1714–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, M.H.; Chruscicki, A.; Christenson, J.; Cairns, J.A.; Lee, T.; Turgeon, R.; Tallon, J.M.; Helmer, J.; Singer, J.; Wong, G.C.; et al. Association of Pre-Hospital Time Intervals and Clinical Outcomes in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2022, 3, e12764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.T.; Ibrahim, A.; Buckley, A.; Maguire, C.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, J.; Arnous, S.; Kiernan, T.J. Total Ischaemic Time in STEMI: Factors Influencing Systemic Delay. Br. J. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawles, J.M.; Metcalfe, M.J.; Shirreffs, C.; Jennings, K.; Kenmure, A.C. Association of Patient Delay with Symptoms, Cardiac Enzymes, and Outcome in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Eur. Heart J. 1990, 11, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewierz, A.; Rakowski, T.; Mamas, M.A.; Tkaczyk, F.; Sowa, Ł.; Malinowski, K.P.; Olszanecka, A.; Siudak, Z. Impact of Historical Partitions of Poland on Reperfusion Delay in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Referred for Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (from the ORPKI Registry). Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2024, 134, 16793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero, F.; Bastante, T.; Cuesta, J.; Benedicto, A.; Salamanca, J.; Restrepo, J.-A.; Aguilar, R.; Gordo, F.; Batlle, M.; Alfonso, F. Factors Associated With Delays in Seeking Medical Attention in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome. Rev. Espanola Cardiol. Engl. Ed 2016, 69, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Ji, K.; Nan, J.; Lu, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Liao, L.; Tang, J. Factors Associated with Decision Time for Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2013, 14, 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraim, F.M.; Carey, M.G. Predictors of Pre-Hospital Delay among Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 75, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beig, J.R.; Tramboo, N.A.; Kumar, K.; Yaqoob, I.; Hafeez, I.; Rather, F.A.; Shah, T.R.; Rather, H.A. Components and Determinants of Therapeutic Delay in Patients with Acute ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Tertiary Care Hospital-Based Study. J. Saudi Heart Assoc. 2017, 29, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, A.K.; Ali, M.J.; Best, P.J.; Bieniarz, M.C.; Bufalino, V.J.; French, W.J.; Henry, T.D.; Hollowell, L.; Jauch, E.C.; Kurz, M.C.; et al. Systems of Care for ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studnek, J.R.; Garvey, L.; Blackwell, T.; Vandeventer, S.; Ward, S.R. Association Between Prehospital Time Intervals and ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction System Performance. Circulation 2010, 122, 1464–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedema, M.D.; Newell, M.C.; Duval, S.; Garberich, R.F.; Handran, C.B.; Larson, D.M.; Mulder, S.; Wang, Y.L.; Lips, D.L.; Henry, T.D. Causes of Delay and Associated Mortality in Patients Transferred With ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2011, 124, 1636–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Ernst, N.; Suryapranata, H.; Ottervanger, J.P.; Hoorntje, J.C.A.; Gosselink, A.T.M.; Dambrink, J.-H.; de Boer, M.-J.; van ’t Hof, A.W.J. Relation of Interhospital Delay and Mortality in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Transferred for Primary Coronary Angioplasty. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 95, 1361–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, J.M.; Armstrong, E.J.; Hoffmayer, K.S.; Bhave, P.D.; MacGregor, J.S.; Hsue, P.; Stein, J.C.; Kinlay, S.; Ganz, P. Impact of Door-to-Activation Time on Door-to-Balloon Time in Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarctions: A Report from the Activate-SF Registry. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2012, 5, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, Y.-T.; Hung, J.-F.; Zhang, S.-Q.; Yeh, Y.-N.; Tsai, M.-J. The Impact of Emergency Department Arrival Time on Door-to-Balloon Time in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Receiving Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokarek, T.; Dziewierz, A.; Plens, K.; Rakowski, T.; Jaroszyńska, A.; Bartuś, S.; Siudak, Z. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention during On- and off-Hours in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Hell. J. Cardiol. HJC Hell. Kardiologike Epitheorese 2021, 62, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menees, D.S.; Peterson, E.D.; Wang, Y.; Curtis, J.P.; Messenger, J.C.; Rumsfeld, J.S.; Gurm, H.S. Door-to-Balloon Time and Mortality among Patients Undergoing Primary PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, S.S.; Curtis, J.P.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Nallamothu, B.K.; Epstein, A.J.; Krumholz, H.M. ; National Cardiovascular Data Registry Association of Door-to-Balloon Time and Mortality in Patients Admitted to Hospital with ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction: National Cohort Study. BMJ 2009, 338, b1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bychowski, J.; Michalski, T.; Bachorski, W.; Jaguszewski, M.; Gruchała, M. Treatment Delays and In-Hospital Outcomes in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction from the Tertiary Center in Poland. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarek, T.; Dziewierz, A.; Malinowski, K.P.; Rakowski, T.; Bartuś, S.; Dudek, D.; Siudak, Z. Treatment Delay and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, P.W.; Gershlick, A.H.; Goldstein, P.; Wilcox, R.; Danays, T.; Lambert, Y.; Sulimov, V.; Rosell Ortiz, F.; Ostojic, M.; Welsh, R.C.; et al. Fibrinolysis or Primary PCI in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1379–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassen, J.F.; Bøtker, H.E.; Terkelsen, C.J. Timely and Optimal Treatment of Patients with STEMI. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2013, 10, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, E.; Primary Coronary Angioplasty, vs. Thrombolysis Group Does Time Matter? A Pooled Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials Comparing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and in-Hospital Fibrinolysis in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, G.; Cassetti, E.; Marino, P. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention-Related Time Delay, Patient’s Risk Profile, and Survival Benefits of Primary Angioplasty vs Lytic Therapy in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2009, 27, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.J.; Swinford, R.D.; Gadde, P.; Lillis, O. Acute Effects of Delayed Reperfusion on Myocardial Infarct Shape and Left Ventricular Volume: A Potential Mechanism of Additional Benefits from Thrombolytic Therapy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1991, 17, 1641–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francone, M.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Carbone, I.; Canali, E.; Scardala, R.; Calabrese, F.A.; Sardella, G.; Mancone, M.; Catalano, C.; Fedele, F.; et al. Impact of Primary Coronary Angioplasty Delay on Myocardial Salvage, Infarct Size, and Microvascular Damage in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Insight from Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 2145–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalling, R.W. Ischemic Time: The New Gold Standard for ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Care. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 2154–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Ma, Q.; Jiao, Y.; Wu, J.; Yu, T.; Hou, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zheng, L.; Sun, Z. Prognostic Value of Myocardial Salvage Index Assessed by Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Reperfused ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redfors, B.; Mohebi, R.; Giustino, G.; Chen, S.; Selker, H.P.; Thiele, H.; Patel, M.R.; Udelson, J.E.; Ohman, E.M.; Eitel, I.; et al. Time Delay, Infarct Size, and Microvascular Obstruction After Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Suryapranata, H.; Ottervanger, J.P.; Antman, E.M. Time Delay to Treatment and Mortality in Primary Angioplasty for Acute Myocardial Infarction: Every Minute of Delay Counts. Circulation 2004, 109, 1223–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, M.; Francuz, P.; Podolecki, T.; Kowalczyk, J.; Mitręga, K.; Olma, A.; Kalarus, Z.; Streb, W. Predictive Factors of Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Improvement after Myocardial Infarction Treated Invasively. Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2023, 19, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węgiel, M.; Surmiak, M.; Malinowski, K.P.; Dziewierz, A.; Surdacki, A.; Bartuś, S.; Rakowski, T. In-Hospital Levels of Circulating MicroRNAs as Potential Predictors of Left Ventricular Remodeling Post-Myocardial Infarction. Med. Kaunas Lith. 2024, 60, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, A.; Lombardi, F. Postinfarct Left Ventricular Remodelling: A Prevailing Cause of Heart Failure. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2016, 2016, 2579832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepper-Christensen, L.; Lønborg, J.; Høfsten, D.E.; Sadjadieh, G.; Schoos, M.M.; Pedersen, F.; Jørgensen, E.; Kelbæk, H.; Haahr-Pedersen, S.; Flensted Lassen, J.; et al. Clinical Outcome Following Late Reperfusion with Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2021, 10, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uleberg, B.; Bønaa, K.H.; Halle, K.K.; Jacobsen, B.K.; Hauglann, B.; Stensland, E.; Førde, O.H. The Relation between Delayed Reperfusion Treatment and Reduced Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A National Prospective Cohort Study. Eur. Heart J. Open 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Diepen, S.; Zheng, Y.; Senaratne, J.M.; Tyrrell, B.D.; Das, D.; Thiele, H.; Henry, T.D.; Bainey, K.R.; Welsh, R.C. Reperfusion in Patients With ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction With Cardiogenic Shock and Prolonged Interhospital Transport Times. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochan, A.; Lee, T.; Moghaddam, N.; Milley, G.; Singer, J.; Cairns, J.A.; Wong, G.C.; Jentzer, J.C.; Van Diepen, S.; Alviar, C.; et al. Reperfusion Delays and Outcomes Among Patients With ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction With and Without Cardiogenic Shock. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odongo, M. Health Communication Campaigns and Their Impact on Public Health Behaviors. J. Commun. 2024, 5, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.E.; Stub, D.; Ngu, P.; Cartledge, S.; Straney, L.; Stewart, M.; Keech, W.; Patsamanis, H.; Shaw, J.; Finn, J. Mass Media Campaigns’ Influence on Prehospital Behavior for Acute Coronary Syndromes: An Evaluation of the Australian Heart Foundation’s Warning Signs Campaign. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moxham, R.N.; d’Entremont, M.-A.; Mir, H.; Schwalm, J.; Natarajan, M.K.; Jolly, S.S. Effect of Prehospital Digital Electrocardiogram Transmission on Revascularization Delays and Mortality in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. CJC Open 2024, 6, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortolani, P.; Marzocchi, A.; Marrozzini, C.; Palmerini, T.; Saia, F.; Taglieri, N.; Alessi, L.; Nardini, P.; Bacchi Reggiani, M.-L.; Guastaroba, P.; et al. Pre-Hospital ECG in Patients Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Interventions within an Integrated System of Care: Reperfusion Times and Long-Term Survival Benefits. EuroIntervention 2011, 7, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagliumi, G. Emerging Data and Decision for Optimizing STEMI Management: The European Perspective. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2009, 11, C19–C24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagai, A.; Al-Khalidi, H.R.; Muñoz, D.; Monk, L.; Roettig, M.L.; Corbett, C.C.; Garvey, J.L.; Wilson, B.H.; Granger, C.B.; Jollis, J.G. Bypassing the Emergency Department and Time to Reperfusion in Patients With Prehospital ST-Segment–Elevation: Findings From the Reperfusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction in Carolina Emergency Departments Project. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013, 6, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le May, M.R.; Wells, G.A.; So, D.Y.; Glover, C.A.; Froeschl, M.; Maloney, J.; Dionne, R.; Marquis, J.-F.; O’Brien, E.R.; Dick, A.; et al. Reduction in Mortality as a Result of Direct Transport From the Field to a Receiving Center for Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, A.A.; Alghammass, M.A.; Aldhahri, F.S.; Alsebti, A.A.; Alfulaij, A.Y.; Alrashed, S.H.; Faleh, H.A.; Alshameri, M.; Alhabib, K.; Arafah, M.; et al. The Impact of Introduction of Code-STEMI Program on the Reduction of Door-to-Balloon Time in Acute ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Single-Center Study in Saudi Arabia. J. Saudi Heart Assoc. 2018, 30, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginanjar, E.; Sjaaf, A.C.; Alwi, I.; Sulistiadi, W.; Suryadarmawan, E.; Wibowo, A.; Liastuti, L.D. CODE STEMI Program Improves Clinical Outcome in ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Open Access Emerg. Med. 2020, Volume 12, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, J.Q.; Tong, D.C.; Sriamareswaran, R.; Yeap, A.; Yip, B.; Wu, S.; Perera, P.; Menon, S.; Noaman, S.A.; Layland, J. In-hospital ‘CODE STEMI’ Improves Door-to-balloon Time in Patients Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2018, 30, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pasquale, G. The Avoidable Delay in the Care of STEMI Patients Is Still a Priority Issue. IJC Heart Vasc. 2022, 39, 101011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazel, R.; Joseph, T.I.; Sankardas, M.A.; Pinto, D.S.; Yeh, R.W.; Kumbhani, D.J.; Nallamothu, B.K. Comparison of Reperfusion Strategies for ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Multivariate Network Meta-analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jortveit, J.; Pripp, A.H.; Halvorsen, S. Outcomes after Delayed Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention vs. Pharmaco-Invasive Strategy in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction in Norway. Eur. Heart J. - Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2022, 8, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Gibson, C.M.; Bellandi, F.; Murphy, S.; Maioli, M.; Noc, M.; Zeymer, U.; Dudek, D.; Arntz, H.-R.; Zorman, S.; et al. Early Glycoprotein IIb-IIIa Inhibitors in Primary Angioplasty (EGYPT) Cooperation: An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. Heart Br. Card. Soc. 2008, 94, 1548–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DE Luca, G.; Bellandi, F.; Huber, K.; Noc, M.; Petronio, A.S.; Arntz, H.-R.; Maioli, M.; Gabriel, H.M.; Zorman, S.; DE Carlo, M.; et al. Early Glycoprotein IIb-IIIa Inhibitors in Primary Angioplasty-Abciximab Long-Term Results (EGYPT-ALT) Cooperation: Individual Patient’s Data Meta-Analysis. J. Thromb. Haemost. JTH 2011, 9, 2361–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van’t Hof, A.W.J.; Ten Berg, J.; Heestermans, T.; Dill, T.; Funck, R.C.; van Werkum, W.; Dambrink, J.-H.E.; Suryapranata, H.; van Houwelingen, G.; Ottervanger, J.P.; et al. Prehospital Initiation of Tirofiban in Patients with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Primary Angioplasty (On-TIME 2): A Multicentre, Double-Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2008, 372, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ten Berg, J.M.; van ’t Hof, A.W.J.; Dill, T.; Heestermans, T.; van Werkum, J.W.; Mosterd, A.; van Houwelingen, G.; Koopmans, P.C.; Stella, P.R.; Boersma, E.; et al. Effect of Early, Pre-Hospital Initiation of High Bolus Dose Tirofiban in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction on Short- and Long-Term Clinical Outcome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 55, 2446–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, K.; Holmes, D.R.; van ’t Hof, A.W.; Montalescot, G.; Aylward, P.E.; Betriu, G.A.; Widimsky, P.; Westerhout, C.M.; Granger, C.B.; Armstrong, P.W. Use of Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitors in Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Insights from the APEX-AMI Trial. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 1708–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, D.; Siudak, Z.; Janzon, M.; Birkemeyer, R.; Aldama-Lopez, G.; Lettieri, C.; Janus, B.; Wisniewski, A.; Berti, S.; Olivari, Z.; et al. European Registry on Patients with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Transferred for Mechanical Reperfusion with a Special Focus on Early Administration of Abciximab -- EUROTRANSFER Registry. Am. Heart J. 2008, 156, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, S.G.; Tendera, M.; de Belder, M.A.; van Boven, A.J.; Widimsky, P.; Janssens, L.; Andersen, H.R.; Betriu, A.; Savonitto, S.; Adamus, J.; et al. Facilitated PCI in Patients with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2205–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, S.G.; Tendera, M.; de Belder, M.A.; van Boven, A.J.; Widimsky, P.; Andersen, H.R.; Betriu, A.; Savonitto, S.; Adamus, J.; Peruga, J.Z.; et al. 1-Year Survival in a Randomized Trial of Facilitated Reperfusion: Results from the FINESSE (Facilitated Intervention with Enhanced Reperfusion Speed to Stop Events) Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009, 2, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, H.C.; Lu, J.; Brodie, B.R.; Armstrong, P.W.; Montalescot, G.; Betriu, A.; Neuman, F.-J.; Effron, M.B.; Barnathan, E.S.; Topol, E.J.; et al. Benefit of Facilitated Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in High-Risk ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients Presenting to Nonpercutaneous Coronary Intervention Hospitals. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009, 2, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoos, M.M.; De Luca, G.; Dangas, G.D.; Clemmensen, P.; Ayele, G.M.; Mehran, R.; Stone, G.W. Impact of Time to Treatment on the Effects of Bivalirudin vs. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitors and Heparin in Patients Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Insights from the HORIZONS-AMI Trial. EuroIntervention J. Eur. Collab. Work. Group Interv. Cardiol. Eur. Soc. Cardiol. 2016, 12, 1144–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heestermans, T.; de Boer, M.-J.; van Werkum, J.W.; Mosterd, A.; Gosselink, A.T.M.; Dambrink, J.-H.E.; van Houwelingen, G.; Koopmans, P.; Hamm, C.; Zijlstra, F.; et al. Higher Efficacy of Pre-Hospital Tirofiban with Longer Pre-Treatment Time to Primary PCI: Protection for the Negative Impact of Time Delay. EuroIntervention J. Eur. Collab. Work. Group Interv. Cardiol. Eur. Soc. Cardiol. 2011, 7, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bor, W.L.; Zheng, K.L.; Tavenier, A.H.; Gibson, C.M.; Granger, C.B.; Bentur, O.; Lobatto, R.; Postma, S.; Coller, B.S.; van ’t Hof, A.W.J.; et al. Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Tolerability of Subcutaneous Administration of a Novel Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitor, RUC-4, in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. EuroIntervention J. Eur. Collab. Work. Group Interv. Cardiol. Eur. Soc. Cardiol. 2021, 17, e401–e410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentur, O.S.; Li, J.; Jiang, C.S.; Martin, L.H.; Kereiakes, D.J.; Coller, B.S. Application of Auxiliary VerifyNow Point-of-Care Assays to Assess the Pharmacodynamics of RUC-4, a Novel αIIbβ3 Receptor Antagonist. TH Open Companion J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 5, e449–e460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kereiakes, D.J.; Henry, T.D.; DeMaria, A.N.; Bentur, O.; Carlson, M.; Seng Yue, C.; Martin, L.H.; Midkiff, J.; Mueller, M.; Meek, T.; et al. First Human Use of RUC-4: A Nonactivating Second-Generation Small-Molecule Platelet Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (Integrin αIIbβ3) Inhibitor Designed for Subcutaneous Point-of-Care Treatment of ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikken, S.A.O.F.; Selvarajah, A.; Hermanides, R.S.; Coller, B.S.; Gibson, C.M.; Granger, C.B.; Lapostolle, F.; Postma, S.; van de Wetering, H.; van Vliet, R.C.W.; et al. Prehospital Treatment with Zalunfiban (RUC-4) in Patients with ST- Elevation Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Rationale and Design of the CELEBRATE Trial. Am. Heart J. 2023, 258, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillerson, D.; Li, S.; Misumida, N.; Wegermann, Z.K.; Abdel-Latif, A.; Ogunbayo, G.O.; Wang, T.Y.; Ziada, K.M. Characteristics, Process Metrics, and Outcomes Among Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction in Rural vs Urban Areas in the US: A Report From the US National Cardiovascular Data Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2022, 7, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhris, M.; Buache, J.; Chenard, P.; Pradel, V.; Virot, P.; Aboyans, V. Rural Urban Differences in Management and Outcomes of Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction; Insights from SCALIM a French Regional Registry. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardas, P.; Kwiatek, A.; Włodarczyk, P.; Urbański, F.; Ciabiada-Bryła, B. Is the KOS-Zawał Coordinated Care Program Effective in Reducing Long-Term Cardiovascular Risk in Coronary Artery Disease Patients in Poland? Insights from Analysis of Statin Persistence in a Nationwide Cohort. Pol. Heart J. 2024, 82, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshchehreh, M.; Groves, E.M.; Tehrani, D.; Amin, A.; Patel, P.M.; Malik, S. Changes in Mortality on Weekend versus Weekday Admissions for Acute Coronary Syndrome in the United States over the Past Decade. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 210, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Deshmukh, A.; Sakhuja, A.; Taneja, A.; Kumar, N.; Jacobs, E.; Nanchal, R. Acute Myocardial Infarction: A National Analysis of the Weekend Effect over Time. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 217–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowska-Sanetra, J.; Sanetra, K.; Synak, M.; Milewski, K.; Gerber, W.; Buszman, P.P. The Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Patients Hospitalized Due to Acute Coronary Syndrome. Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2023, 19, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Verdoia, M.; Cercek, M.; Jensen, L.O.; Vavlukis, M.; Calmac, L.; Johnson, T.; Ferrer, G.R.; Ganyukov, V.; Wojakowski, W.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Mechanical Reperfusion for Patients With STEMI. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2321–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójcik, M.; Karpiak, J.; Zaręba, L.; Przybylski, A. High In-Hospital Mortality and Prevalence of Cardiogenic Shock in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Concomitant COVID-19. Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2023, 19, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeymer, U. Maintaining Optimal Care for Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients during War Times. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamas, M.A.; Martin, G.P.; Grygier, M.; Wadhera, R.K.; Mallen, C.; Curzen, N.; Wijeysundera, H.C.; Banerjee, A.; Kontopantelis, E.; Rashid, M.; et al. Indirect Impact of the War in Ukraine on Primary Percutaneous Coronary Interventions for ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction in Poland. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewierz, A.; Siudak, Z.; Rakowski, T.; Kleczyński, P.; Dubiel, J.S.; Dudek, D. Early Administration of Abciximab Reduces Mortality in Female Patients with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (from the EUROTRANSFER Registry). J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2013, 36, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huded, C.P.; Johnson, M.; Kravitz, K.; Menon, V.; Abdallah, M.; Gullett, T.C.; Hantz, S.; Ellis, S.G.; Podolsky, S.R.; Meldon, S.W.; et al. 4-Step Protocol for Disparities in STEMI Care and Outcomes in Women. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 2122–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, B.; Acevedo, M.; Appelman, Y.; Bairey Merz, C.N.; Chieffo, A.; Figtree, G.A.; Guerrero, M.; Kunadian, V.; Lam, C.S.P.; Maas, A.H.E.M.; et al. The Lancet Women and Cardiovascular Disease Commission: Reducing the Global Burden by 2030. The Lancet 2021, 397, 2385–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolub, G.; Mamas, M.A.; Malinowski, K.P.; Zabojszcz, M.; Dardzińska, N.; Jaskulska, P.; Hawranek, M.; Siudak, Z. Closing Gender Gap in Time Delays and Mortality in STEMI: Insights from the ORPKI Registry. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewierz, A.; Vogel, B.; Zdzierak, B.; Kuleta, M.; Malinowski, K.P.; Rakowski, T.; Piotrowska, A.; Mehran, R.; Siudak, Z. Operator-Patient Sex Discordance and Periprocedural Outcomes of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (from the ORPKI Polish National Registry). Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2023, 19, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziewierz, A.; Zdzierak, B.; Malinowski, K.P.; Siudak, Z.; Zasada, W.; Tokarek, T.; Zabojszcz, M.; Dolecka-Ślusarczyk, M.; Dudek, D.; Bartuś, S.; et al. Diabetes Mellitus Is Still a Strong Predictor of Periprocedural Outcomes of Primary Percutaneous Coronary Interventions in Patients Presenting with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (from the ORPKI Polish National Registry). J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kałużna-Oleksy, M.; Paradies, V. Women in Interventional Cardiology – Patients’ and Operators’ Perspectives. Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2023, 19, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, M.; Mehta, A.; Balakrishna, A.M.; Saad, M.; Ventetuolo, C.E.; Roswell, R.O.; Poppas, A.; Abbott, J.D.; Vallabhajosyula, S. Race, Ethnicity, and Gender Disparities in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Crit. Care Clin. 2024, 40, 685–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glickman, S.W.; Granger, C.B.; Ou, F.-S.; O’Brien, S.; Lytle, B.L.; Cairns, C.B.; Mears, G.; Hoekstra, J.W.; Garvey, J.L.; Peterson, E.D.; et al. Impact of a Statewide ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction Regionalization Program on Treatment Times for Women, Minorities, and the Elderly. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2010, 3, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya’qoub, L.; Lemor, A.; Dabbagh, M.; O’Neill, W.; Khandelwal, A.; Martinez, S.C.; Ibrahim, N.E.; Grines, C.; Voeltz, M.; Basir, M.B. Racial, Ethnic, and Sex Disparities in Patients With STEMI and Cardiogenic Shock. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewierz, A.; Siudak, Z.; Rakowski, T.; Dubiel, J.S.; Dudek, D. Age-Related Differences in Treatment Strategies and Clinical Outcomes in Unselected Cohort of Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Transferred for Primary Angioplasty. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2012, 34, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jervis Somo, L.; Okobi, O.E.; Asomugha-Okwara, A.; Osias, K.; Mordi, P.O.; Enyeneokpon, E.; Etakewen, P.O.; Okoro, C. Retrospective Analysis of Atypical Chest Pain Presentations in Older Adults and Their Association With Missed Acute Coronary Syndrome Diagnosis in the Emergency Department: National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS)-Based Study. Cureus 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konuş, A.H.; Özderya, A.; Çırakoğlu, Ö.F.; Sayın, M.R.; Yerlikaya, M.G. The Relationship between Advanced Lung Cancer Inflammation Index and High SYNTAX Score in Patients with Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Postepy W Kardiologii Interwencyjnej Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2024, 20, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Lu, C.; Mo, J.; Wang, T.; Li, X.; Yang, Y. Efficacy and Safety of Different Revascularization Strategies in Patients with Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction with Multivessel Disease: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Postepy W Kardiologii Interwencyjnej Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2024, 20, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, V.; Kanwar, M.K.; Barnett, C.F.; Cowger, J.A.; Damluji, A.A.; Farr, M.; Goodlin, S.J.; Katz, J.N.; McIlvennan, C.K.; Sinha, S.S.; et al. Cardiogenic Shock in Older Adults: A Focus on Age-Associated Risks and Approach to Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopar-Nieto, R.; González-Pacheco, H.; Arias-Mendoza, A.; Briseño-De-la Cruz, J.L.; Araiza-Garaygordobil, D.; Sierra-Lara Martínez, D.; Mendoza-García, S.; Altamirano-Castillo, A.; Dattoli-García, C.A.; Manzur-Sandoval, D.; et al. Infarto de miocardio con elevación del ST no reperfundido: nociones de un país de ingresos bajos a medios. Arch. Cardiol. México 2023, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, A.; Moolla, M.; Jeemon, P.; Punnoose, E.; Ashraf, S.M.; Pisharody, S.; Viswanathan, S.; Jayakumar, T.G.; Jabir, A.; Mathew, J.P.; et al. Timeliness of Reperfusion in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Outcomes in Kerala, India: Results of the TRUST Outcomes Registry. Postgrad. Med. J. 2025, 101, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, M.; Doğan, Z. ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction for Pharmacoinvasive Strategy or Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Gaza (STEPP 2- PCI) Trial. Arch. Med. Sci. – Atheroscler. Dis. 2024, 9, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S.R.; Helseth, H.C.; Baker, P.O.; Keller, G.A.; Meyers, H.P.; Herman, R.; Smith, S.W. Artificial Intelligence Detection of Occlusive Myocardial Infarction from Electrocardiograms Interpreted as “Normal” by Conventional Algorithms. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.S.; Zadrozniak, P.; Jasina, G.; Grotek-Cuprjak, A.; Andrade, J.G.; Svennberg, E.; Diederichsen, S.Z.; McIntyre, W.F.; Stavrakis, S.; Benezet-Mazuecos, J.; et al. Artificial Intelligence for Direct-to-Physician Reporting of Ambulatory Electrocardiography. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Jeon, K.L.; Lee, Y.-J.; You, S.C.; Lee, S.-J.; Hong, S.-J.; Ahn, C.-M.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, B.-K.; Ko, Y.-G.; et al. Development of Clinically Validated Artificial Intelligence Model for Detecting ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2024, 84, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P.-H.; Lin, C.; Lin, C.-S.; Liu, W.-T.; Lin, T.-K.; Tsai, D.-J.; Hung, Y.-J.; Chen, Y.-H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lin, S.-H.; et al. Economic Analysis of an AI-Enabled ECG Alert System: Impact on Mortality Outcomes from a Pragmatic Randomized Trial. Npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, A.; Nichol, A.A.; Martinez-Martin, N.; Larson, D.B.; Abramoff, M.; Wolf, R.M.; Char, D. Ethical Considerations in the Design and Conduct of Clinical Trials of Artificial Intelligence. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2432482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonicki, Z. Large Multi-Modal Models – the Present or Future of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine? Croat. Med. J. 2024, 65, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldajani, A.; Chaabo, O.; Brouillette, F.; Anchouche, K.; Lachance, Y.; Akl, E.; Dandona, S.; Martucci, G.; Pelletier, J.-P.; Piazza, N.; et al. Impact of a Mobile, Cloud-Based Care-Coordination Platform on Door-to-Balloon Time in Patients With STEMI: Initial Results. CJC Open 2024, 6, 1094–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damaševičius, R.; Bacanin, N.; Misra, S. From Sensors to Safety: Internet of Emergency Services (IoES) for Emergency Response and Disaster Management. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2023, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Manshaii, F.; Tioran, K.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yang, M.; Yin, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, K. Wearable Biosensors for Cardiovascular Monitoring Leveraging Nanomaterials. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Verburg, A.; Hof, A.V.; Ten Berg, J.; Kereiakes, D.J.; Coller, B.S.; Gibson, C.M. Current and Future Roles of Glycoprotein IIb–IIIa Inhibitors in Primary Angioplasty for ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, H.; Nojima, T.; Fujisaki, N.; Tsukahara, K.; Yamamoto, H.; Yamada, T.; Aokage, T.; Yumoto, T.; Osako, T.; Nakao, A. Therapeutic Strategies for Ischemia Reperfusion Injury in Emergency Medicine. Acute Med. Surg. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronick, S.L.; Kurz, M.C.; Lin, S.; Edelson, D.P.; Berg, R.A.; Billi, J.E.; Cabanas, J.G.; Cone, D.C.; Diercks, D.B.; Foster, J. (Jim); et al. Part 4: Systems of Care and Continuous Quality Improvement: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2015, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Primary PCI | Fibrinolysis | Pharmaco-invasive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Mechanical opening | Thrombus dissolution |

Initial lysis followed by coronary angiogram / PCI |

| Time indication | FMC-to-device ≤120 min | PCI unavailable or >120 min | FMC-to-device >120 min |

| Advantages | >95% success definitive treatment |

Rapid deployment anywhere | Combines speed with definitive therapy |

| Disadvantages | Time-dependent; infrastructure needs |

~65% success bleeding risk |

Intracranial hemorrhage risk requires coordination |

| Delayed presentation efficacy | Benefit diminishes significantly |

Efficacy declines after hours | Superior to delayed primary PCI |

| Time interval | Definition | Guideline target | Common delay sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient delay | Symptom onset to FMC | Minimize | Symptom misinterpretation, denial, general practitioner contact, self-transport |

| Pre-hospital system | FMC to hospital arrival | Minimize | EMS dispatch, scene time, transport distance |

| Door-in-door-out | Non-PCI hospital arrival to departure | ≤30 min | Transport availability, ED processes, diagnostics |

| FMC / Door-to-ECG | FMC / Hospital arrival to ECG | ≤10 min | Triage delays, symptom recognition failure |

| Door-to-activation | Hospital arrival to cath lab activation | ≤20 min | ECG interpretation, decision-making |

| FMC / Door-to-balloon | FMC / Hospital arrival to device inflation | ≤90 min | Team assembly, complex procedures, instability |

| Total ischemic time | Symptom onset to reperfusion | ≤120 min (optimal | All combined delays |

| Barrier domain | High-resource setting | Low/middle-income setting |

|---|---|---|

| Patient/community | Symptom misinterpretation; denial; failure to use EMS | Lack of basic awareness; fear of catastrophic cost; reliance on traditional medicine |

| Pre-hospital system | EMS on-scene time; inter-hospital transfer delays; “weekend effect” | Lack of organized EMS; no pre-hospital ECG/triage; long transport over poor infrastructure |

| In-hospital system | Cath lab activation delays; ED dwell time; simultaneous presentations | Paucity of PCI-capable centers; lack of trained specialists; inability to provide 24/7 service |

| Financial | Insurance co-pays/deductibles; market share competition between hospitals | Prohibitive out-of-pocket cost of PCI; lack of universal health coverage |

| Primary reperfusion strategy | Primary PCI (default) | Pharmaco-invasive (often the only feasible option) |

| Stakeholder | Key recommendations | Specific actions |

|---|---|---|

|

Policymakers & public health officials |

Fund sustained public awareness campaigns |

• Focus on typical and atypical symptoms • Emphasize immediate activation of emergency medical services (e.g., 1-1-2 / 9-1-1) • Ensure cultural competency |

| Support regional STEMI networks |

• Define protocols for rural/remote areas • Ensure pharmaco-invasive strategy availability • Mandate performance reporting |

|

|

Healthcare system leaders |

Implement standardized protocols |

• Establish emergency physician activation authority • Deploy single-call notification systems • Monitor performance continuously |

| Address temporal disparities | • Ensure 24/7 equivalent care quality • Optimize off-hours staffing models |

|

| Use standardization to promote equity |

• Reduce care variability • Target vulnerable populations |

|

| Clinicians | Maintain guideline adherence | • Minimize all controllable delays • Focus on door-to-ECG and door-to-balloon metrics |

| Embrace flexible strategies | • Utilize pharmaco-invasive approach when appropriate • Implement risk-stratified triage protocols |

|

| Recognize bias potential | • Maintain heightened awareness for atypical presentations • Address disparities proactively |

|

| Researchers | Identify priority research areas | • Develop patient delay reduction strategies • Create disparity elimination interventions • Optimize pharmaco-invasive approaches • Validate AI-based risk stratification and triage tools in diverse populations |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).