1. Introduction

Human gaze behaviour is influenced by many factors, including lighting level and the observer’s ability to see their surroundings. This paper investigates how conventional pedestrian lighting affects the size and shape of the useful visual field (UVF) using an eye-tracking study. The results help clarify how the information available to pedestrians at night differs from daytime.

The spatial region of the visual field over which a pedestrian’s gaze tends to fall is essential for characterising visual adaptation at night. Gaze-behaviour analysis has previously been used to examine where pedestrians look during night and daytime (Davoudian & Raynham, 2012). However, that study limited its analysis to the classes of objects viewed and did not assess the overall pattern of view directions relative to the direction of travel along the street. The present study re-analyses the same eye-tracking videos by calculating the distribution of fixations about the axis of travel, thereby comparing the shape and size of the UVF in day versus night conditions. The UVF corresponds to the region around the point of fixation within which information can be perceived and processed during a visual task (Mackworth, 1965). The following section discusses factors affecting the UVF and the role of peripheral vision.

The UVF is the visual area from which information can be extracted without eye or head movements at a brief glance (Ball, Wadley, & Edwards, 2002). Its size is not fixed and is generally smaller than the full visual field; it can be influenced by several factors, including peripheral target conspicuity (Scialfa, Thomas, & Joffe, 1994). The size of the UVF is critical for environmental analysis and depends on the quantity and quality of visual information available (Rogé et al., 2004). Any deterioration in the UVF has major consequences for many everyday activities (Rogé, Pébayle, Kiehn, & Muzet, 2002).

Peripheral vision comprises most of the visual field, and the collaboration between central and peripheral vision is important for overall visual performance (Chan & Courtney, 1993). Central vision includes the fovea, parafovea, and perifovea, comprising approximately 18°20′ of visual angle (Riordan-Eva & Whitcher, 2008). Typically, a potentially informative or salient object is detected by peripheral vision, after which a saccade brings the object to the fovea for detailed inspection— a general principle of visual search and scanning behaviour (Inditsky, Bodmann, & Fleck, 1982). The central field of vision subserves recognition and tasks requiring fine detail, reading, colour perception, or precise motion analysis.

The aim of the present experiment was therefore to determine how far into the periphery visual information is utilised and to quantify the UVF for pedestrians during the day and, under conventional residential street-lighting conditions, at night.

Gaze-behaviour analysis has been used to investigate the UVF (Rogé, Pébayle, Campagne, & Muzet, 2005; Scialfa et al., 1994), and to examine where drivers look by capturing the majority of their eye movements (Land, 2006). Eye-tracking data provide insight into observers’ attentive behaviour, indicating where attention is deployed in the environment with or without the presence of other visual tasks (Duchowski, 2007).

2. Method

Participants and setting. Tests were conducted in both daytime and night-time conditions. Fifteen participants (8 male) took part at night, and five (2 male) took part during the day. Participants were aged 20–60 years and reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision. The walking routes were located in a residential area of Fulham, London. Eye movements were recorded with an SMI iViewX head-mounted eye-tracking device (HED).

Procedure. Wearing the eye tracker, participants walked along the test route and completed a simple wayfinding task: navigating from point A to point B using a schematic map. All participants undertook the task unaccompanied and met the researcher at the endpoint. A brief interview followed, during which the eye-tracker video was reviewed; participants described what they saw and their thoughts at different points along the route. For full methodological detail, see N. Davoudian & P. Raynham (2012). This research complied with the American Psychological Association Code of Ethics, received approval from the Institutional Review Board at University College London, and obtained informed consent from all participants.

Data processing. To identify fixation locations, ten still images per second were sampled from each video. To ensure all fixations were counted while avoiding multiple counts of the same location due to dwells, only fixations separated by more than 3° of visual angle were included. For each sampled frame, we measured: (i) the coordinates of the fixation point; (ii) the point at eye height on the centre of the footpath; and (iii) the tilt of the notional horizon (

Figure 1). These measurements were non-trivial because participants naturally turned and tilted their heads while walking, so the video lacked a fixed frame of reference. In total, 44,528 images were analysed.

3. Results

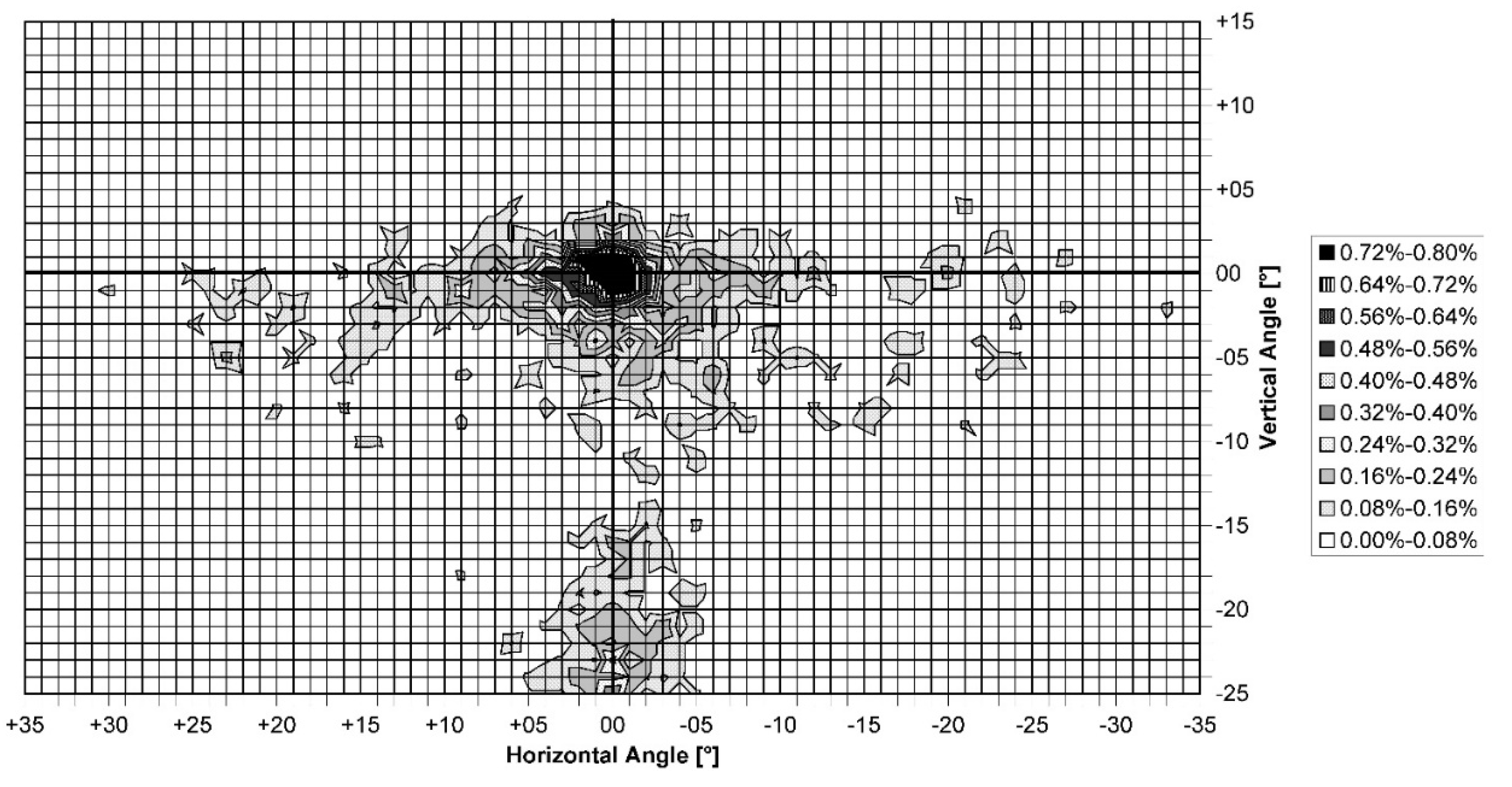

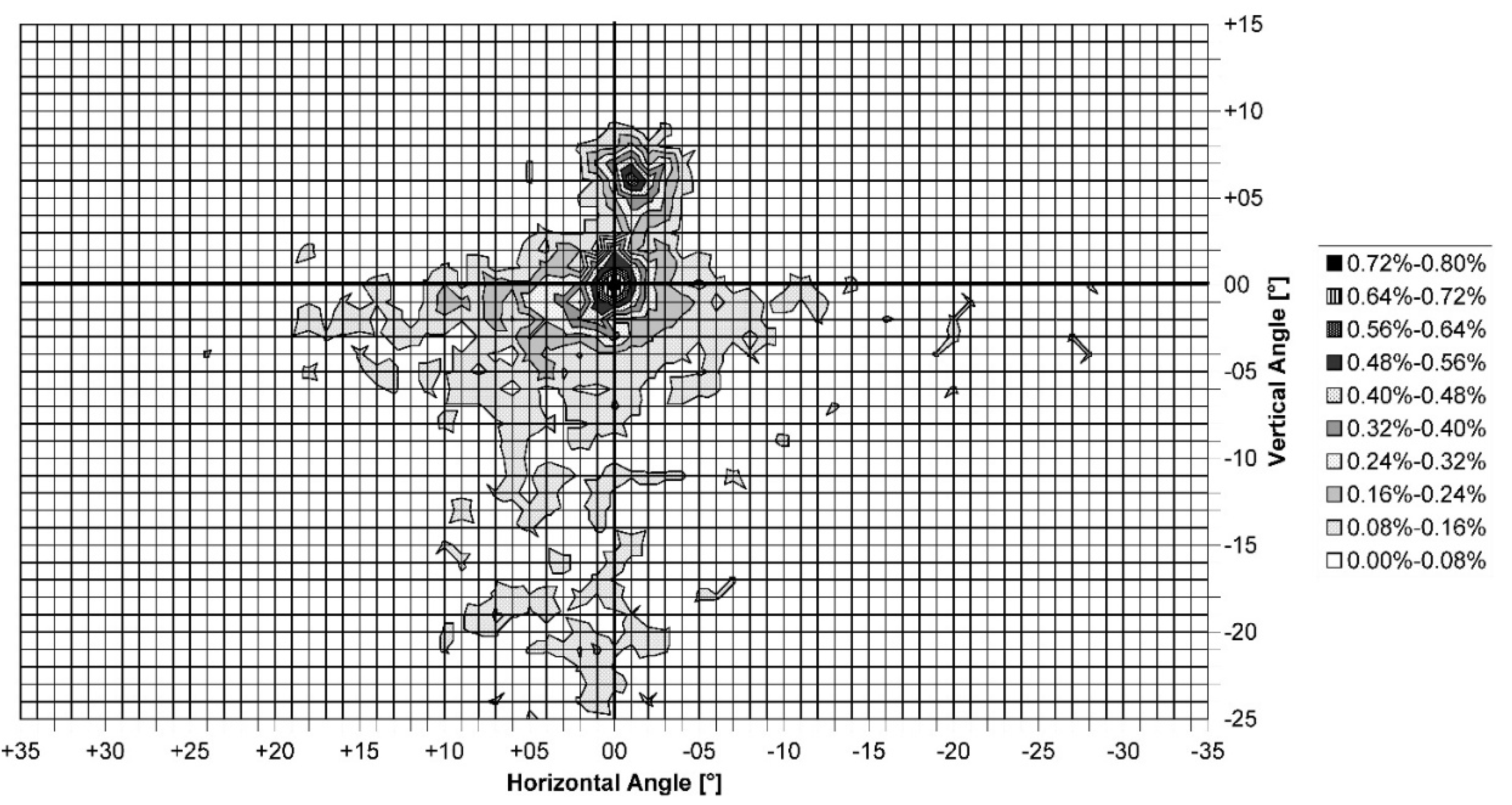

From the recorded eye-tracking data, we computed the angular deviation of gaze relative to the axis of travel along the street. The visual field was discretised into 1° × 1° bins, and fixations falling within each bin were tallied to derive the proportion of viewing time allocated to each direction.

Figure 2 presents the daytime gaze distribution, and

Figure 3 illustrates the night-time distribution.

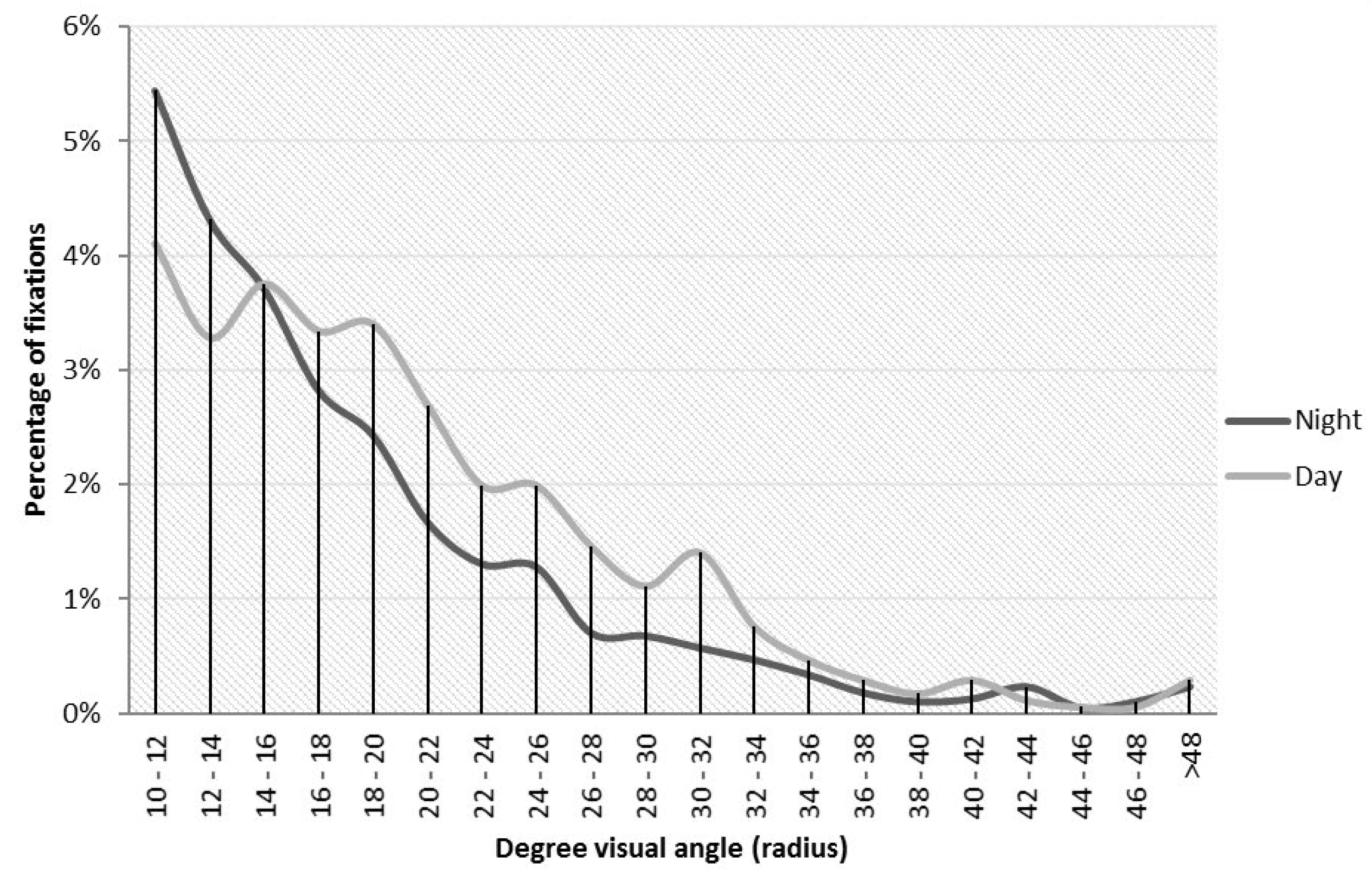

Figure 4 depicts the distribution of gaze beyond 10° of visual angle under daytime and night-time conditions. An independent-samples

t-test showed that gaze allocation beyond 10° was significantly lower at night than during the day,

t(7781) = 4.031,

p = 0.0001.

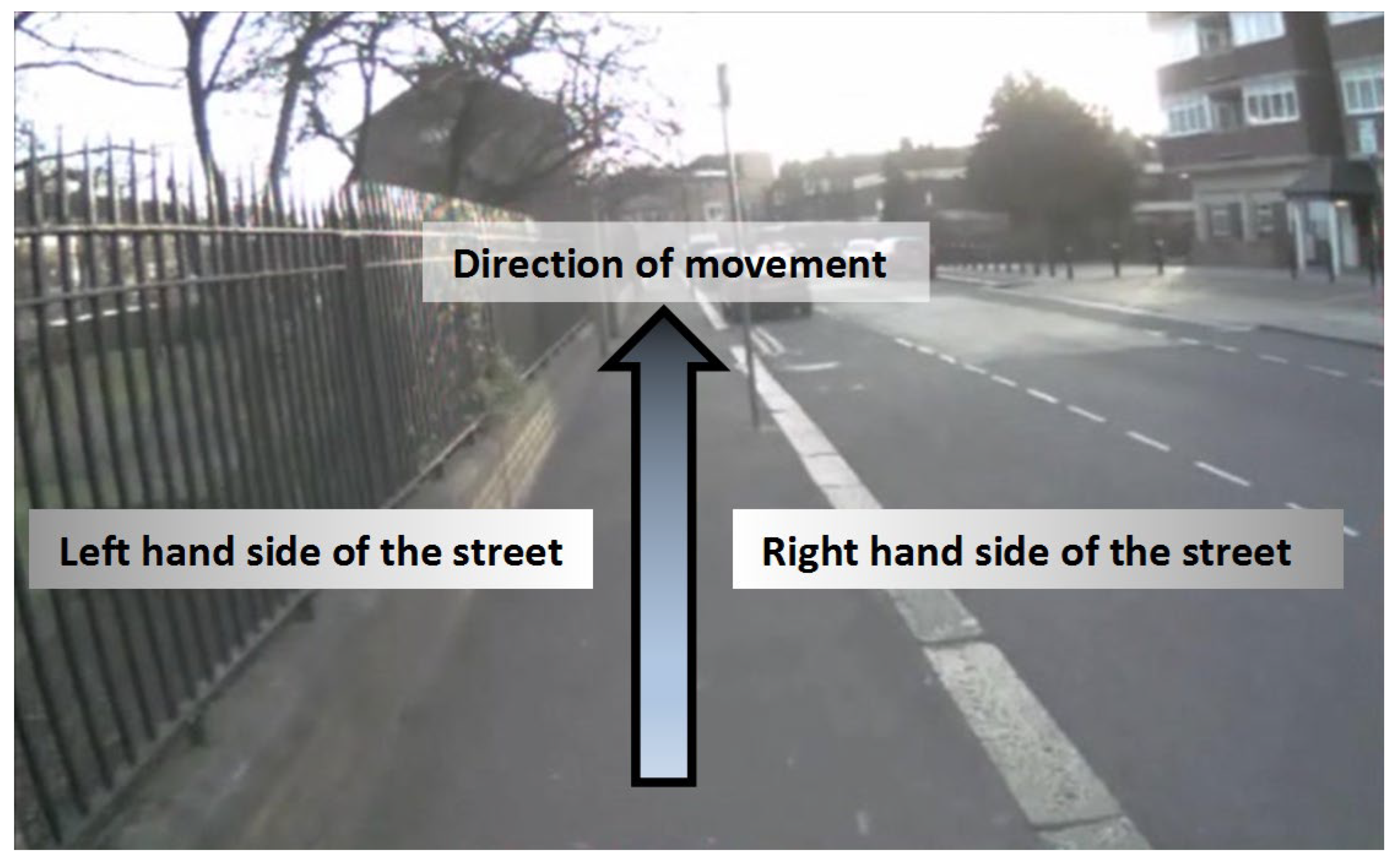

These results suggest that peripheral information available during the day is less accessible after dark. To characterise the nature of daytime peripheral fixations (beyond 10°), we examined the objects/areas fixated: fixations were substantially more frequent on vertical surfaces (73.79%) than on horizontal surfaces (26.21%). It should be noted that the availability of horizontal surfaces was asymmetric on either side of the walking direction (

Figure 5).

The right-hand side of the walking direction offered greater availability of horizontal surfaces than the left-hand side. Comparing fixations on horizontal surfaces to the left versus the right revealed a significant increase in fixations where horizontal surfaces were more available (

p < 0.01;

Table 1).

Additionally, we examined the categories of objects fixated in the periphery. The analysis did not indicate a preference for specific object types: fixations ranged from incidental environmental features to critical, task-relevant elements such as moving cars and bicycles.

Interview data further showed that most night-time participants (13 of 15) reported feeling unsafe along the test route, whereas daytime participants characterised the neighbourhood as a reasonably pleasant residential area. Elevated state anxiety during the night-time condition may therefore constitute a confounding factor.

4. Discussion

This study compared the pedestrian UVF in daytime and night-time conditions. The results show that the UVF contracts towards central vision at night, consistent with a tunnel-vision phenomenon (Chan & Courtney, 1993).

The size of the UVF is determined not only by peripheral factors (e.g., retinal anatomy, visual acuity) but also by central characteristics such as the brain’s information-processing capacity (Saida & Ikeda, 1979). Prior research indicates that gaze behaviour can be biased during spatial decision-making in wayfinding and spatial perception (Wiener, Hölscher, Büchner, & Konieczny, 2012), and by elevated anxiety (Wieser, Pauli, Grosseibl, Molzow, & Mühlberger, 2010). Night-time lighting conditions also influence pedestrians’ perception of space, fear of crime, and wayfinding in streets (Del-Negro, 2015; Fotios, Unwin, & Farrall, 2015; Uttley & Fotios, 2017).

On the basis of this literature, several explanations can be proposed for the loss of peripheral information at night:

Reduced visual saliency: Lower conspicuity of peripheral objects at night means fewer stimuli capture attention, leading to fewer peripheral saccades and a reduced UVF (Scialfa, Thomas, & Joffe, 1994).

Processing-capacity adjustment: Lower illumination may prompt the visual system to restrict the UVF so that the information load per fixation remains manageable (Saida & Ikeda, 1979); increased cognitive workload at night can produce tunnel-vision–like changes in scanning (Leibowitz & Appelle, 1969).

Anxiety-related bias: Higher anxiety at night can bias gaze behaviour towards central, threat-monitoring regions (Wieser et al., 2010).

A combination of the above factors.

Irrespective of the precise mechanism, the UVF at night is smaller than during the day. It is reasonable to assume that daytime patterns represent more favourable visual conditions than night-time. Consequently, any changes to street lighting intended to mitigate this contraction should consider providing more light at the point of fixation and increasing light on vertical targets in the periphery. These findings may improve understanding of the information lost at night relative to daytime—implicating changes in spatial perception, reassurance, and wayfinding—and can inform the estimation of the effective field of view used when assessing adaptation luminance.

5. Conclusion

This study shows that, under conventional street-lighting conditions, pedestrians’ useful visual field (UVF) contracts at night. The loss of information occurs predominantly for vertical targets in the periphery. While street-lighting design has traditionally prioritised horizontal illuminance, our results emphasise the importance of vertical illuminance and the need to account for it explicitly in street-lighting design.

Recognition of vertical illuminance in standards is emerging. For example, the recent edition of EN 13201-2 (EN-13201-2, 2015) includes an option to require vertical illuminance where road lighting is intended to meet the needs of pedestrians and cyclists. However, the standard currently suggests applying vertical requirements primarily when facial recognition is necessary. The findings of this study suggest there are benefits to specifying vertical illuminance even when facial recognition is not the primary task, to support peripheral information uptake, wayfinding, and reassurance after dark.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out as part of the EPSRC funded MERLIN II project, the project is run as collaboration between University College London and University of Sheffield, UK.

References

- Ball, K. K.; Wadley, V. G.; Edwards, J. D. Advances in technology used to assess and retrain older drivers. Gerontechnology 2002, 1(4), 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.; Courtney, A. J. Effects of cognitive foveal load on a peripheral single-target detection task. Perceptual and motor skills 1993, 77(2), 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davoudian, N.; Raynham, P. What do pedestrians look at at night? Lighting Research and Technology 2012, 1477153512437157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Negro, D. THE INFLUENCE OF LIGHTING ON WAYFINDING IN THE URBAN ENVIRONMENT. Paper presented at the CIE Annual Meeting, Manchester, UK; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Duchowski, A. Eye tracking methodology: Theory and practice; Springer Science & Business Media, 2007; Vol. 373. [Google Scholar]

- EN-13201-2. (2015). Road lighting. In Part 2: Performance requirements.

- Fotios, S.; Unwin, J.; Farrall, S. Road lighting and pedestrian reassurance after dark: A review. Lighting Research & Technology 2015, 47(4), 449–469. [Google Scholar]

- Inditsky, B.; Bodmann, H.; Fleck, H. Elements of visual performance Contrast metric—visibility lobes—eye movements. Lighting Research and Technology 1982, 14(4), 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, M. F. Eye movements and the control of actions in everyday life. Progress in retinal and eye research 2006, 25(3), 296–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leibowitz, H.; Appelle, S. The effect of a central task on luminance thresholds for peripherally presented stimuli. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 1969, 11(4), 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackworth, N. H. Visual noise causes tunnel vision. Psychonomic Science 1965, 3(1-12), 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan-Eva, P.; Whitcher, J. Vaughan & Asbury’s general ophthalmology; Wiley Online Library, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rogé, J.; Pébayle, T.; Campagne, A.; Muzet, A. Useful visual field reduction as a function of age and risk of accident in simulated car driving. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2005, 46(5), 1774–1779. [Google Scholar]

- Rogé, J.; Pébayle, T.; Kiehn, L.; Muzet, A. Alteration of the useful visual field as a function of state of vigilance in simulated car driving. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour 2002, 5(3), 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogé, J.; Pébayle, T.; Lambilliotte, E.; Spitzenstetter, F.; Giselbrecht, D.; Muzet, A. Influence of age, speed and duration of monotonous driving task in traffic on the driver’s useful visual field. Vision research 2004, 44(23), 2737–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saida, S.; Ikeda, M. Useful visual field size for pattern perception. Perception & Psychophysics 1979, 25(2), 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scialfa, C. T.; Thomas, D. M.; Joffe, K. M. Age differences in the useful field of view: an eye movement analysis. Optometry & Vision Science 1994, 71(12), 736–742. [Google Scholar]

- Uttley, J.; Fotios, S. Using the daylight savings clock change to show ambient light conditions significantly influence active travel. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2017, 53, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, J. M.; Hölscher, C.; Büchner, S.; Konieczny, L. Gaze behaviour during space perception and spatial decision making. Psychological research 2012, 76(6), 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieser, M. J.; Pauli, P.; Grosseibl, M.; Molzow, I.; Mühlberger, A. Virtual social interactions in social anxiety—the impact of sex, gaze, and interpersonal distance. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2010, 13(5), 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).