1. Introduction

Fault signal extraction, analysis, and diagnosis in industrial equipment are critical for ensuring production safety and improving operational efficiency. These challenges are pervasive across a broad spectrum of domains, including rotating machinery, power systems, and new energy equipment. For example, vibration signals from rolling bearings in rotating machinery, transient electrical signals in power transmission lines, and multiphysics coupling signals in the drivetrains of new energy vehicles all share common characteristics such as non-stationarity, strong noise interference, and feature ambiguity. These shared traits pose significant challenges to the accurate identification of early-stage faults across various sectors, including rotating machinery, power systems, and electric vehicles [

1]. Timely and effective fault diagnosis not only mitigates economic losses caused by unexpected downtime but also helps prevent catastrophic safety incidents, thereby playing a vital role in intelligent manufacturing and predictive maintenance paradigms [

2].

The primary bottleneck in fault diagnosis arises from the inherent complexity of vibration signals. On one hand, these signals are typically nonlinear and non-stationary, often influenced by diverse and mixed sources of noise present in real-world industrial environments. As noted by Mohd Ghazali and Rahiman [

3], dynamic variations in operational speed, load, and fault conditions are key contributors to signal non-stationarity, posing substantial challenges to conventional signal processing techniques. Furthermore, noise often masks critical fault-related frequencies, complicating the extraction of discriminative features. For instance, impact characteristics of bearing vibration signals may be buried in broadband noise; high-frequency decay components in power system fault transients can be easily mixed with harmonic interference; and vibration-electrical coupled signals in new energy drivetrains may involve complex multiphysical-field disturbances [

4]. On the other hand, although fault signals from different domains share certain statistical and structural properties, their specific manifestations can differ significantly. Mechanical systems are primarily characterized by the distribution of vibration energy, power systems depend on transient variations in voltage and current, and new energy vehicles require integration of multidimensional information such as motor speed, torque, and vibration. This heterogeneity places stringent demands on the generalization capability of fault diagnosis methods across different application domains [

5].

Despite significant advancements, current fault diagnosis techniques still exhibit notable limitations when addressing the aforementioned challenges. At the signal processing level, traditional methods such as the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) identify fault characteristic frequencies by transforming time-domain sequences into frequency-domain representations [

6]. However, because FFT assumes signal stationarity, it fails to effectively capture the time-varying features of non-stationary signals, often leading to inaccurate feature extraction. The Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) improves upon this by segmenting signals and applying FFT within a sliding window to produce time-frequency representations [

7]. Although STFT provides some capability for handling non-stationary signals, its effectiveness is constrained by the fixed window size, resulting in a trade-off between time and frequency resolution that limits its performance under dynamic conditions.

Wavelet Transform (WT), which employs scalable and translatable wavelet basis functions for multiresolution analysis [

8], partially overcomes the limitations of STFT by providing better localization of transient events in the time-frequency domain. However, its effectiveness heavily depends on the proper selection of the wavelet basis; inappropriate choices may introduce significant deviations in the analysis results. Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD), an adaptive decomposition technique [

9], decomposes signals into a series of Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) without requiring predefined basis functions. EMD is well-suited for nonlinear and non-stationary signals, enabling extraction of features across multiple frequency scales. Nevertheless, it suffers from mode mixing and endpoint effects, which can degrade the accuracy of the decomposition.

To address these issues, techniques such as Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD) and Complementary Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise (CEEMDAN) have been developed, introducing white noise to suppress mode mixing [

10,

11]. However, these approaches may still leave residual noise, limiting their effectiveness in real-world applications. Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD), an emerging signal decomposition technique, addresses many of the drawbacks of EMD by decomposing a signal into a set of band-limited intrinsic mode functions. VMD formulates the decomposition as a constrained variational optimization problem, minimizing the sum of the bandwidths of the modes while ensuring that their sum reconstructs the original signal. Supported by solid mathematical foundations, VMD exhibits strong robustness in noisy environments, making it highly attractive for fault diagnosis tasks. For example, Dibaj et al. [

12] demonstrated its effectiveness in isolating fault features in rotating machinery.

However, the performance of VMD is highly sensitive to its key parameters, specifically the number of modes (K) and the penalty factor (α). Improper selection can result in over-decomposition or under-decomposition, negatively impacting the quality of extracted features. Traditional parameter selection typically relies on empirical knowledge or extensive trial-and-error, which lacks systematic guidance and can be computationally inefficient.

At the model level, deep learning techniques--particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)--have made significant advances in fault diagnosis due to their ability to automatically learn hierarchical features from raw or preprocessed vibration signals, thereby reducing reliance on manual feature engineering and domain expertise. For example, Azamfar et al. [

13] highlighted the superior capability of CNNs in capturing complex signal patterns. Researchers have developed various CNN architectures tailored to vibration signal characteristics, such as transforming time-domain signals into two-dimensional time–frequency images for classification via 2D CNNs [

14], or employing 1D CNNs to directly process time-series data [

15].

However, conventional CNNs typically require large amounts of labeled data for training and are computationally intensive, with model sizes often exceeding 10⁶ parameters. This high computational demand limits their suitability for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices. With the advancement of Industry 4.0, edge computing has become increasingly important in industrial applications. By processing data locally near the source, edge computing significantly reduces network latency and enhances real-time responsiveness, enabling localized monitoring and rapid fault diagnosis. It also decreases dependence on cloud infrastructure, lowers bandwidth requirements, and improves data privacy.

Nevertheless, edge devices are inherently limited in computational power, memory, and energy capacity. Deep CNNs with large parameter counts and deep architectures are challenging to deploy in such environments, as their high computational cost and memory usage hinder real-time inference. Additionally, deep learning models are sensitive to data quality--noise can bias feature learning--and they generally lack interpretability, which is a critical concern in industrial applications that demand transparent decision-making.

To address these challenges, lightweight CNN architectures such as MobileNet and EfficientNet have been proposed [

16]. These models reduce parameter count and computational load through techniques like depthwise separable convolutions and global average pooling, and further improve efficiency via model quantization and hardware acceleration. While these methods enhance suitability for edge deployment, achieving a balance between diagnostic accuracy and computational efficiency remains a challenge for fault diagnosis tasks.

To overcome the threefold challenge of (1) non-stationary and noisy vibration signals, (2) computational inefficiency of deep models on edge platforms, and (3) limited model generalization, this study proposes a bearing fault diagnosis method that integrates Quantum-Inspired Optimization for Variational Mode Decomposition (QD-VMD) with a Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network (L-CNN). The proposed method first applies VMD to decompose vibration signals into intrinsic mode functions (IMFs). A quantum-inspired optimization algorithm is then used to adaptively optimize the critical VMD parameters, including the number of modes (K) and the penalty factor (α), ensuring high-quality decomposition even under noisy conditions. Compared with traditional optimization approaches, quantum-inspired methods explore the parameter space more efficiently and are less susceptible to local optima.

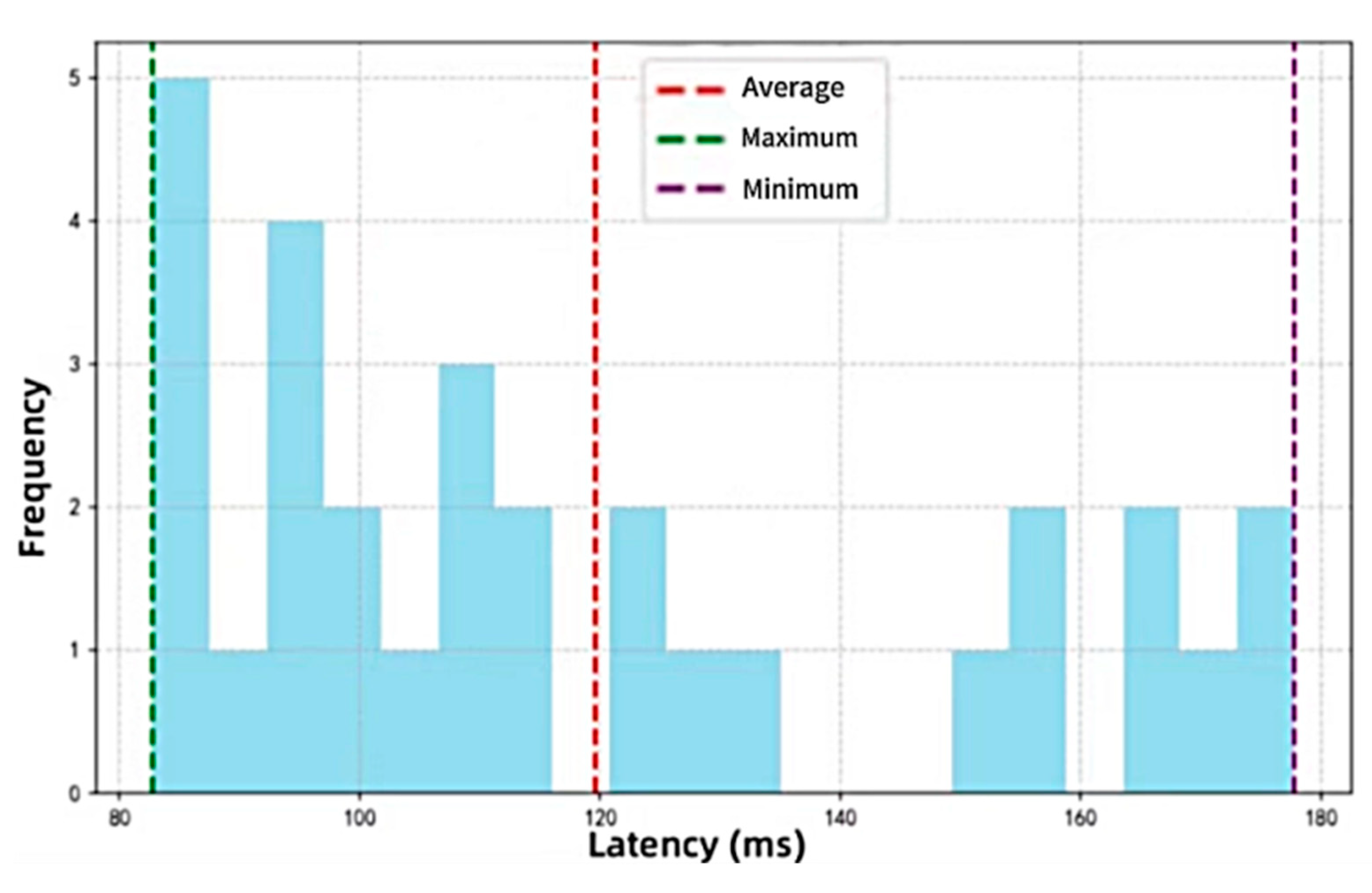

Next, a feature matrix is constructed from the decomposed IMFs, containing both time-domain features (e.g., kurtosis and skewness) and frequency-domain features (e.g., spectral amplitude and peak frequency). These features are input to a lightweight CNN designed with depthwise separable convolutions, global average pooling, channel attention mechanisms, and batch normalization, substantially reducing computational complexity while maintaining high diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, the model is optimized using mixed-precision quantization and TensorRT acceleration, minimizing inference latency and enabling efficient deployment on resource-constrained edge devices.

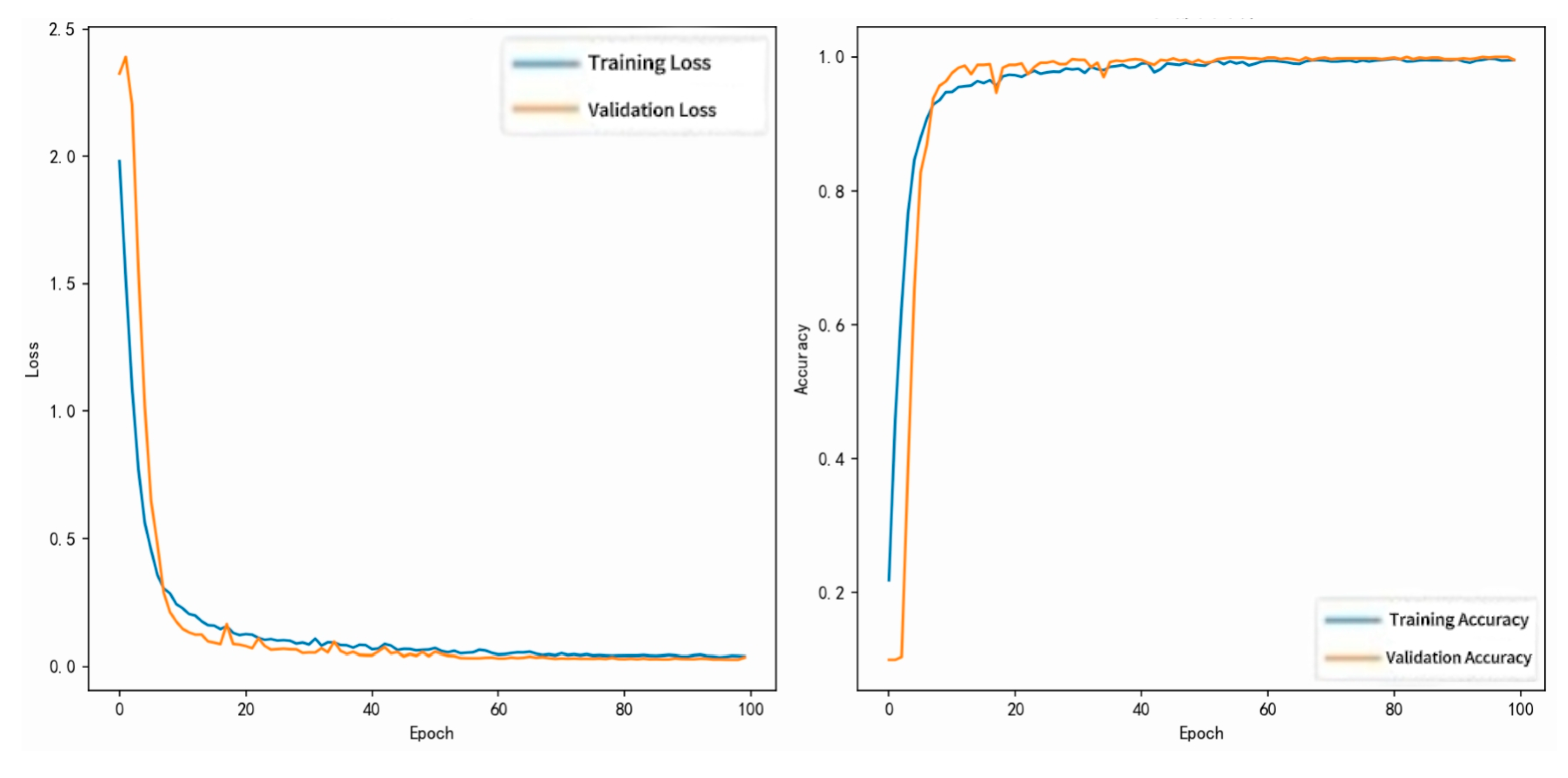

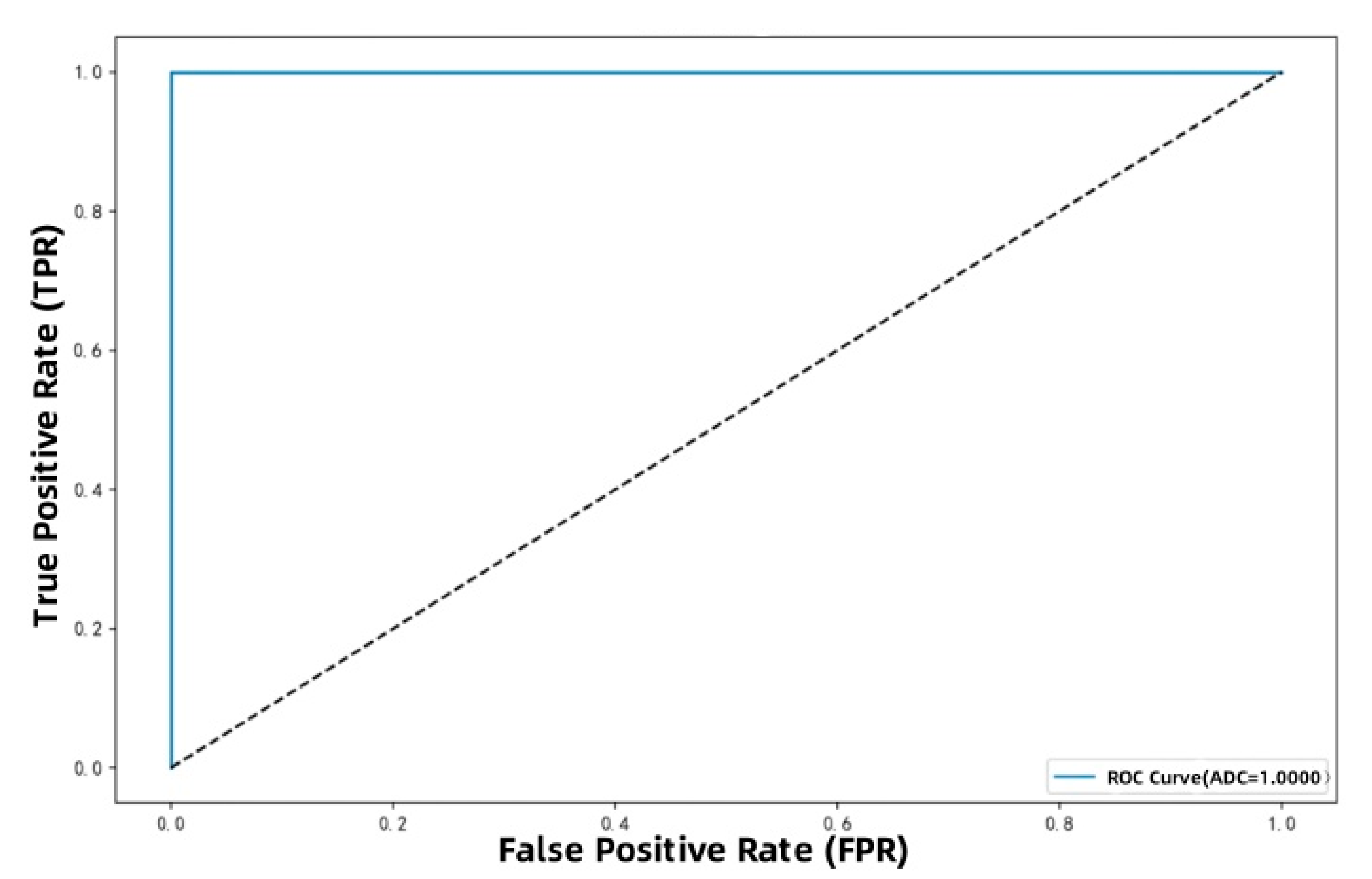

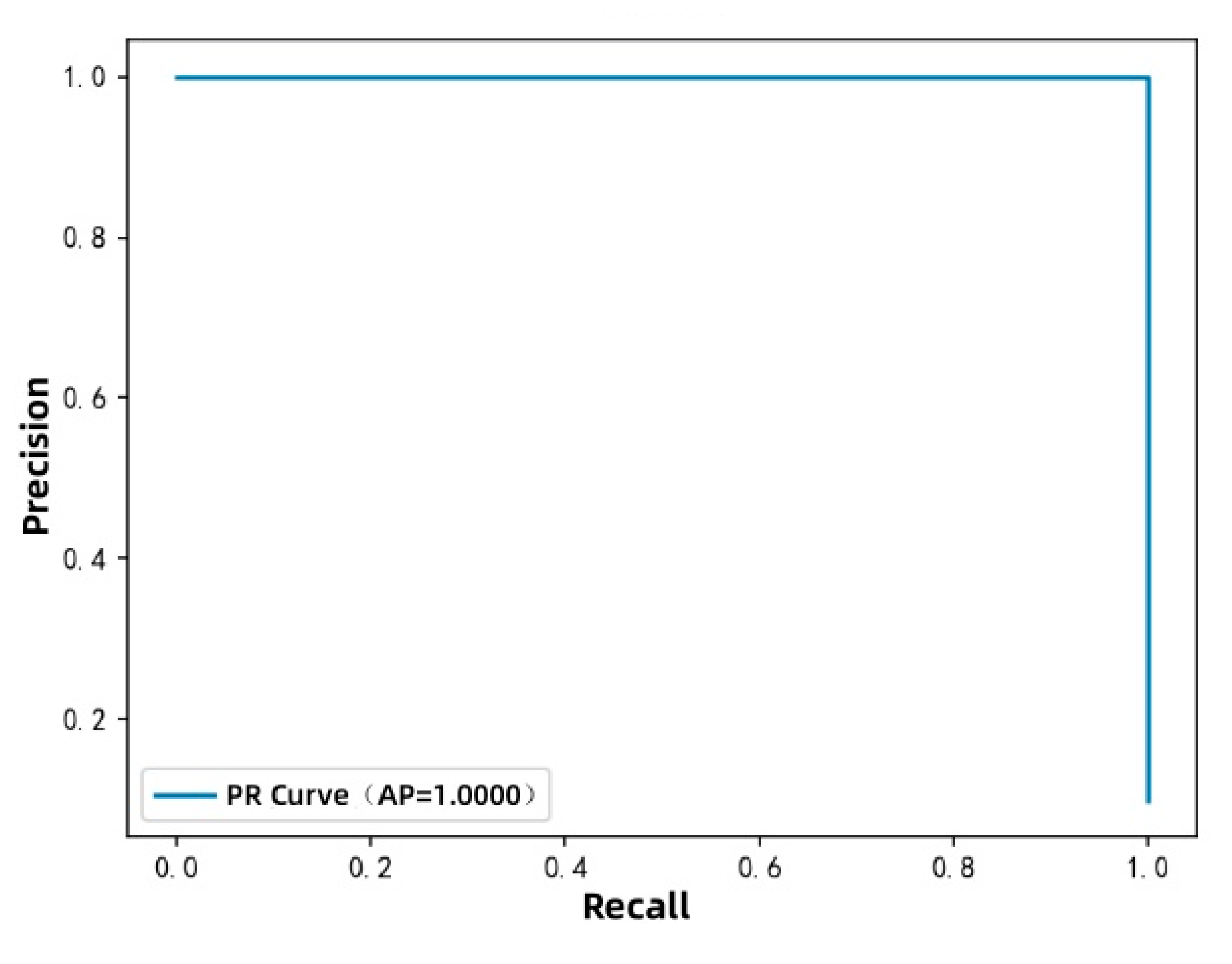

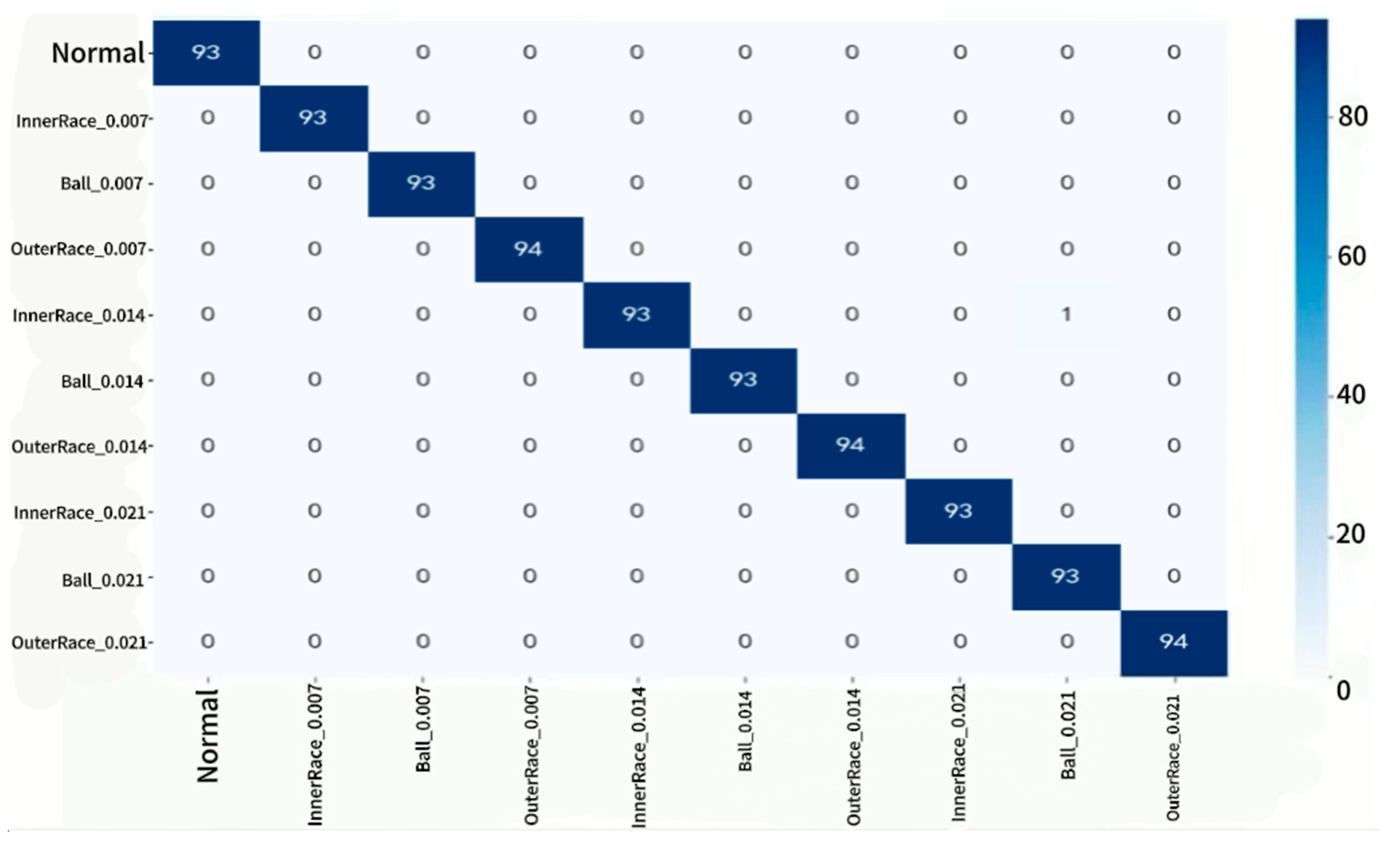

To validate the effectiveness and generalizability of the proposed method, a multi-level experimental framework is employed. Core experiments are conducted on the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) bearing dataset, serving as the primary benchmark. Through analysis of parameter optimization trajectories, quantitative evaluation of decomposition performance, and assessment of classification accuracy, the QD-VMD–L-CNN method is validated in terms of diagnostic accuracy, computational efficiency, and model compactness. Results are compared against baseline models such as conventional CNNs to demonstrate relative performance gains.

In addition, generalization experiments are performed using the IEEE PES Transmission Line Fault Dataset (IEEE PES Dataset) and the New Energy Vehicles Transmission System Dataset (NEV Dataset). These experiments involve cross-domain transfer testing to evaluate the method’s adaptability to heterogeneous signal types. Metrics such as Precision, Recall, and F1-score are quantitatively analyzed, and real-time inference performance on edge devices is assessed to confirm the model’s cross-domain generalization capability. By combining both domain-specific validation and cross-scenario testing, this experimental setup provides a comprehensive verification of the practical applicability of the QDVMD–L-CNN framework in complex industrial environments.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

(1) Systematic Construction of the QDVMD-LCNN Framework:

A novel fault diagnosis algorithm is proposed that integrates Quantum-Inspired Optimization, Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD), and a Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network (L-CNN) into a unified framework, termed QDVMD-LCNN. This approach bridges the gap between signal processing and classification in traditional methods, enhancing feature extraction robustness under strong noise and improving deployment efficiency on edge devices through the cross-domain fusion of quantum-inspired mechanisms and deep learning.

(2) Quantum-Inspired Optimization for VMD (QD-VMD):

A quantum-inspired optimization strategy is developed to adaptively determine the key VMD parameters--the number of modes (K) and the penalty factor (α)--which significantly improves decomposition quality and robustness under noisy conditions.

(3) Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network Architecture:

A low-complexity L-CNN architecture is designed using depthwise separable convolutions, global average pooling, and model quantization, enabling high-accuracy fault diagnosis with substantially reduced computational complexity and memory usage, making it well-suited for real-time inference on resource-constrained edge devices.

(4) Validation of Effectiveness and Generalizability Across Multiple Scenarios:Experiments on the CWRU bearing dataset demonstrate high classification accuracy, extremely low false positive rates, and minimal inference latency, fully meeting the demands of real-time industrial diagnostics. Furthermore, cross-domain evaluations with diverse datasets validate the model’s generalization capability across heterogeneous data and multi-physical domains, laying a foundation for the development of unified and scalable health monitoring platforms.

The aforementioned contributions systematically address three common challenges: (1) the difficulty of feature extraction caused by signal non-stationarity and strong noise interference; (2) the high computational resource demands of deep learning models, which hinder deployment on edge devices; and (3) limited cross-domain generalization capability. This work establishes a comprehensive technical pipeline of “adaptive parameter optimization--lightweight modeling--cross-domain validation,” which simultaneously enhances the robustness of signal decomposition via a quantum-inspired mechanism, overcomes resource constraints for edge deployment through a lightweight architecture, and verifies the method’s universal applicability through multi-domain validation. Together, these advances represent a systematic breakthrough that overcomes key bottlenecks in existing technologies.

The main chapters of this work are organized as follows:

Chapter 1 reviews related work, elucidates the mathematical principles of VMD and its applications across multiple domains, and discusses the core mechanisms of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) along with recent advances in lightweight model design, thus laying the theoretical foundation for the proposed method.

Chapter 2 details the technical aspects of the proposed diagnostic algorithm, including quantum-inspired VMD parameter optimization based on quantum sampling and rotation gate mechanisms, as well as the architecture design, regularization strategies, and deployment optimizations of the lightweight CNN.

Chapter 3 presents core experiments on the CWRU bearing dataset, analyzing parameter optimization trajectories, evaluating signal decomposition quality, and validating classification performance to demonstrate effectiveness within a single domain.

Chapter 4 conducts cross-domain generalization tests on datasets from power system transient signals and new energy vehicle transmission systems, verifying the method’s adaptability to heterogeneous scenarios.

Chapter 5 discusses the advantages, limitations, and future research directions of the method, analyzes practical application challenges, and proposes potential improvements.

Chapter 6 concludes the work by summarizing the core contributions and highlighting the algorithm’s efficacy and its support for multi-domain equipment health monitoring.

3. Methodology

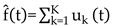

Building upon the aforementioned works, this paper proposes a fault diagnosis algorithm that integrates Quantum-Inspired Parameter Optimization (QIPO), Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD), and a Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network (L-CNN). The overall framework is illustrated in

Figure 1.

The diagram illustrates the end-to-end process from parameter optimization to fault classification. The algorithm is divided into three phases:

Phase I: A parameter optimization module based on quantum bit mechanics (QIPO) adaptively searches for the optimal configuration of key VMD parameters--specifically, the number of modes (K) and the penalty factor (α).

Phase II: The optimized parameters are then input into the VMD module to perform multi-modal decomposition of non-stationary signals and construct multi-scale feature representations.

Phase III: A lightweight convolutional neural network (L-CNN) is employed to classify the resulting feature tensor and identify fault categories.

This method establishes a closed-loop structure encompassing parameter search, signal decomposition, and model decision-making. It is characterized by high adaptability, strong scalability, and compatibility with embedded deployment, making it well-suited for complex signal recognition tasks in industrial environments.3.1. Subsection

3.1. Phase I: QIPO Process

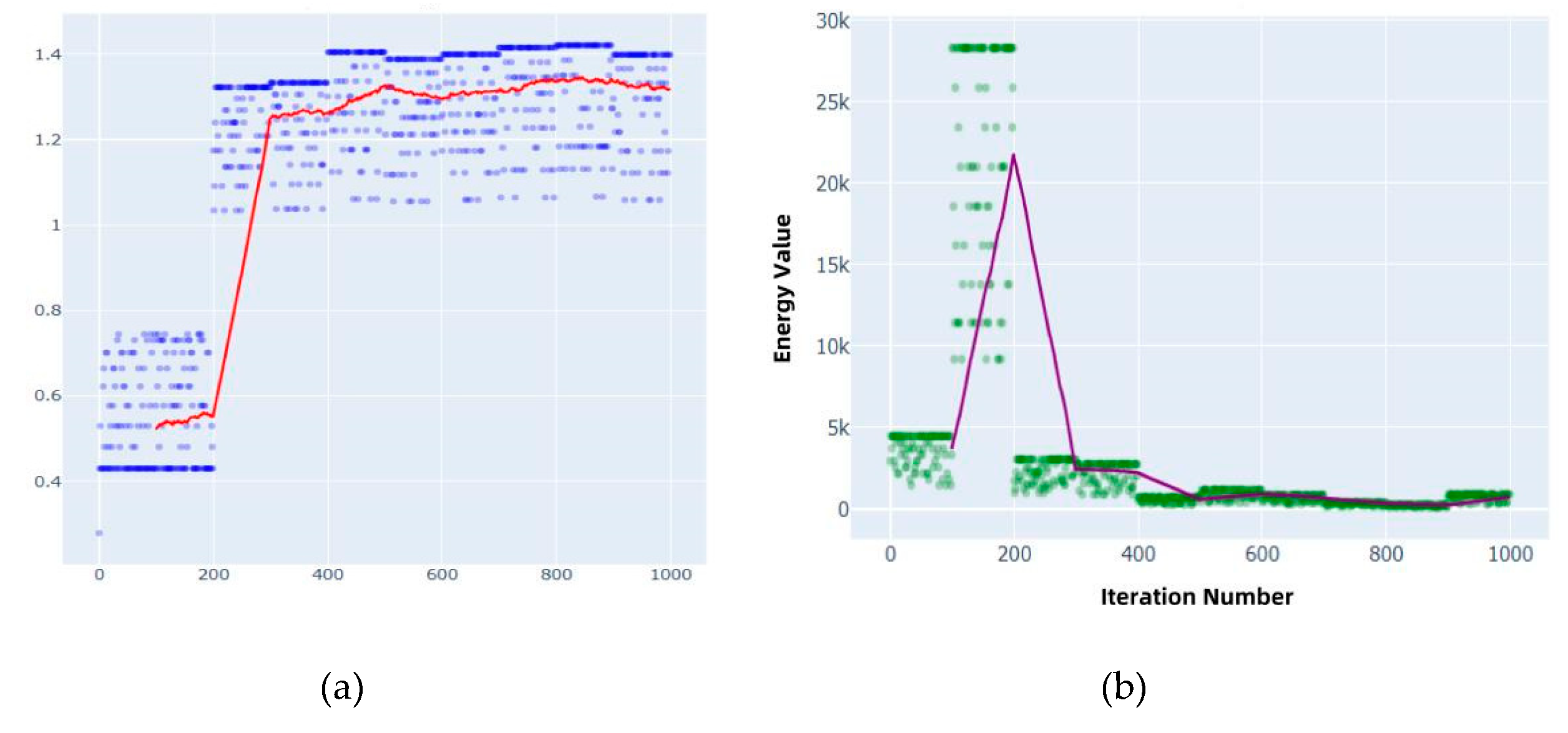

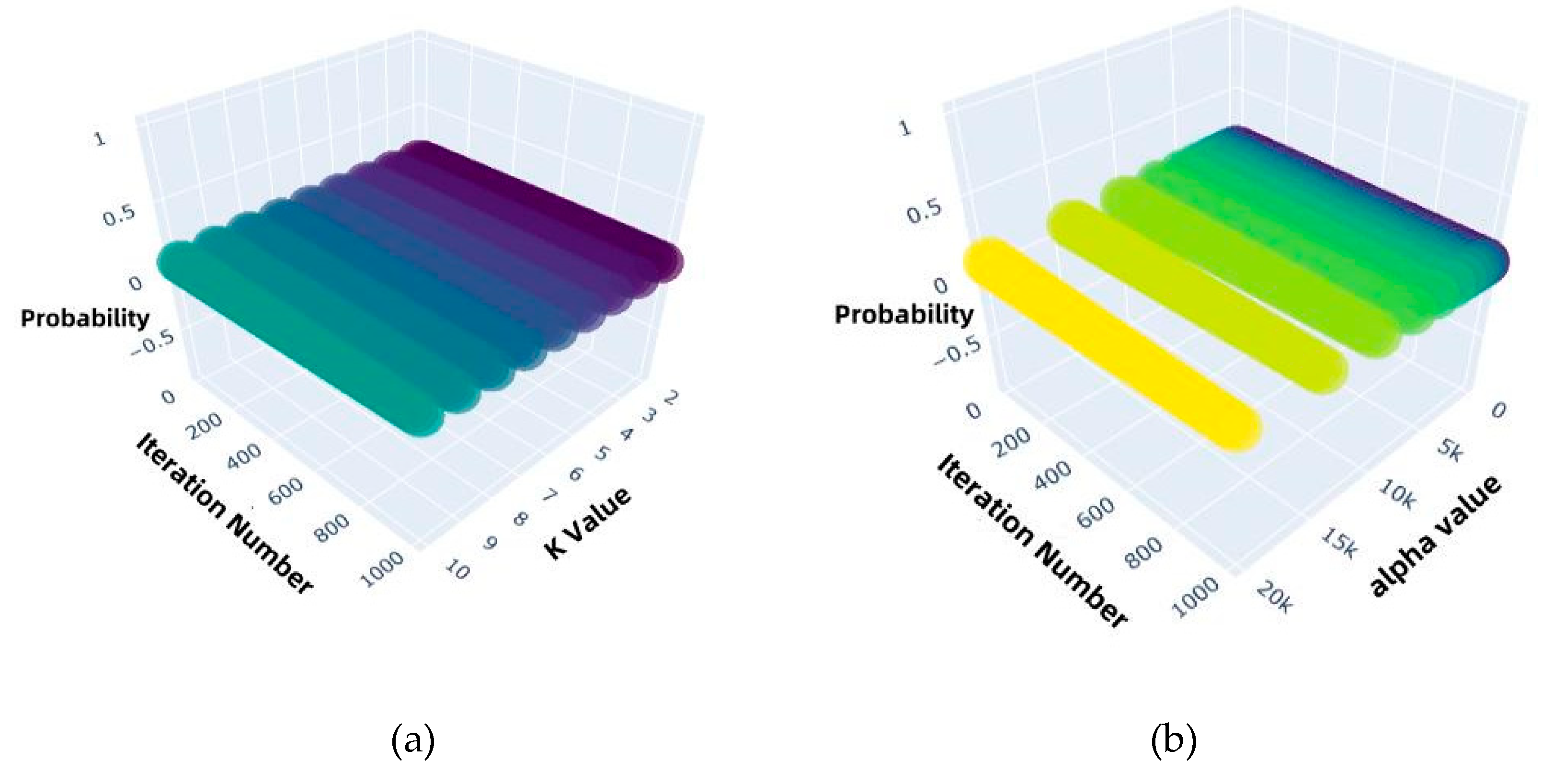

To address the limitations of Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD)--particularly its reliance on manually defined parameters and its limited adaptability to complex operating conditions--this phase introduces a Quantum-Inspired Parameter Optimization (QIPO) mechanism based on quantum probability modeling. The QIPO framework comprises three key steps: quantum state probability modeling, probability updating driven by reward feedback, and phase-guided local convergence via quantum rotation gates.

Step 1: Quantum State Probability Modeling

In this study, the parameter space is encoded as a finite-dimensional discrete set of quantum states, and a probability vector of length is constructed, where is the number of qubits, corresponding to available states. Each quantum state is uniquely mapped to a combination of VMD parameters (, ).

At the initial stage, the quantum state vector is modeled using a uniform distribution:

Here,

denotes the probability of the

-th quantum state, and i is the state index ranging from 0 to

. This strategy is conceptually analogous to the Hadamard transform in quantum computing, which produces an unbiased superposition across the entire parameter space, serving as a basis for global exploration. The initialization scheme, inspired by the Hadamard Transform [

17], can be regarded as generating a uniform coverage of the parameter space, providing a broad foundation for subsequent optimization.

To implement the mapping between quantum states with uniform distribution as defined in Equation (3) and VMD parameters, a discretized parameter space is constructed physically on the upper level. Since continuous hyperparameters are difficult to directly associate with discrete quantum states in a one-to-one manner, this study discretizes the number of modes K and the penalty factor α into the intervals and , respectively, and divides them into and segments. This forms a two-dimensional search grid of size . Each grid cell is uniquely mapped to a quantum state , ensuring a one-to-one correspondence between the discretized parameter space and the quantum state space of size. This mapping provides physical support for the quantum initialization defined in Equation (3), and underpins the reward-driven probability update mechanism introduced in Step 2.

This step establishes a one-to-one correspondence between the quantum states and the VMD core parameters (number of modes K and penalty factor α) through uniform probability initialization and mapping. It lays the foundation for efficient search and optimal determination of VMD parameters in the subsequent machine-driven optimization process.

Step 2: Probability Update Driven by Reward Feedback

To evaluate the quality of each parameter combination, a VMD decomposition metric based on an energy criterion is introduced:

Here, denotes the sum of the bandwidth energy across all modes, is the -th mode component, and is the number of modes. A smaller indicates better mode compactness and decomposition performance.

To balance decomposition quality and model complexity, the following reward function is constructed:

where

is the reward score,

is a small positive constant (typically 0.0001), and

is the penalty factor. ,,are the weights for the three components of the evaluation metric. This reward function penalizes energy and model complexity to prevent overfitting.

After obtaining the reward score for each quantum state, the probability vector is updated using a sampling mechanism that favors states with higher rewards. To this end, a normalized softmax-like function is adopted to adjust the state probabilities as follows:

Here, is the updated probability of the -th state, reflecting its optimization result. is the previous probability before updating. The scaling factor controls the strength of selection. If the distribution becomes overly concentrated, a sampling mechanism based on probability truncation is used to suppress overfitting and maintain exploratory diversity across the search space.

In this step, the decomposition index (Equation 4) is used to quantify VMD performance. Combined with the reward score (Equation 5), the parameter pair (K,α) is comprehensively evaluated. Through probability updates based on Equation (6), superior parameter combinations are sampled with higher probability, enabling adaptive search convergence and enhanced parameter clustering.

Step 3: Phase-Guided Local Convergence via Quantum Rotation Gates

In the post-exploration phase, a Quantum Rotator mechanism is introduced to simulate phase rotation, thereby refining the search direction and convergence efficiency. In this mechanism, a phase direction vector

is defined for each quantum state, where the state amplitude is represented as a complex number

. The phase

controls the interference direction in the search space. The quantum rotation operation updates the amplitude according to:

Here,

is the updated amplitude of the

-th quantum state, reflecting the optimization effect.

is the amplitude before updating. The rotation angle

is determined by the reward score

and the learning rate

. To implement the strategy of “coarse exploration first, fine exploitation later,” a staged decay strategy is adopted for

:

Here, is the time-dependent learning rate,

denotes the turning point from global to local search, and is the decay coefficient. This mechanism enables broad search in the early stage, while gradually narrowing the search scope and enhancing exploitation ability as rewards accumulate.

Under the action of the quantum rotation gate, the amplitude and phase of each state’s solution probability are recalculated. After that, normalization is applied using the following update rule:

This update process effectively simulates the constructive and destructive interference mechanisms observed in quantum systems: states with higher reward values experience larger phase shifts, leading to constructive interference in the superposition state and significantly increasing their sampling probabilities; in contrast, states with lower rewards are gradually suppressed due to destructive interference. This results in adaptive guidance of the search direction, thereby enhancing the sampler’s local convergence capability and its ability to escape local optima in complex non-convex spaces.

In this step, quantum rotation gates (Equations 7–8) are used to adjust the phase of each quantum state. Constructive interference is employed to strengthen the sampling probability of high-reward VMD parameter pairs (K,α) (as formulated in Equation 9), enabling fine-grained optimization and stable convergence of the parameter search process, ultimately leading to the determination of the optimal VMD parameter configuration.

3.2. Phase II: VMD Process

In this phase, the VMD parameter configuration obtained from Phase I is used to decompose the original signal into intrinsic mode components and to construct a corresponding feature tensor. This structured output is designed to serve as input for downstream neural network models. The process is divided into two steps:mode decomposition and feature construction, and signal reconstruction with fidelity constraints.

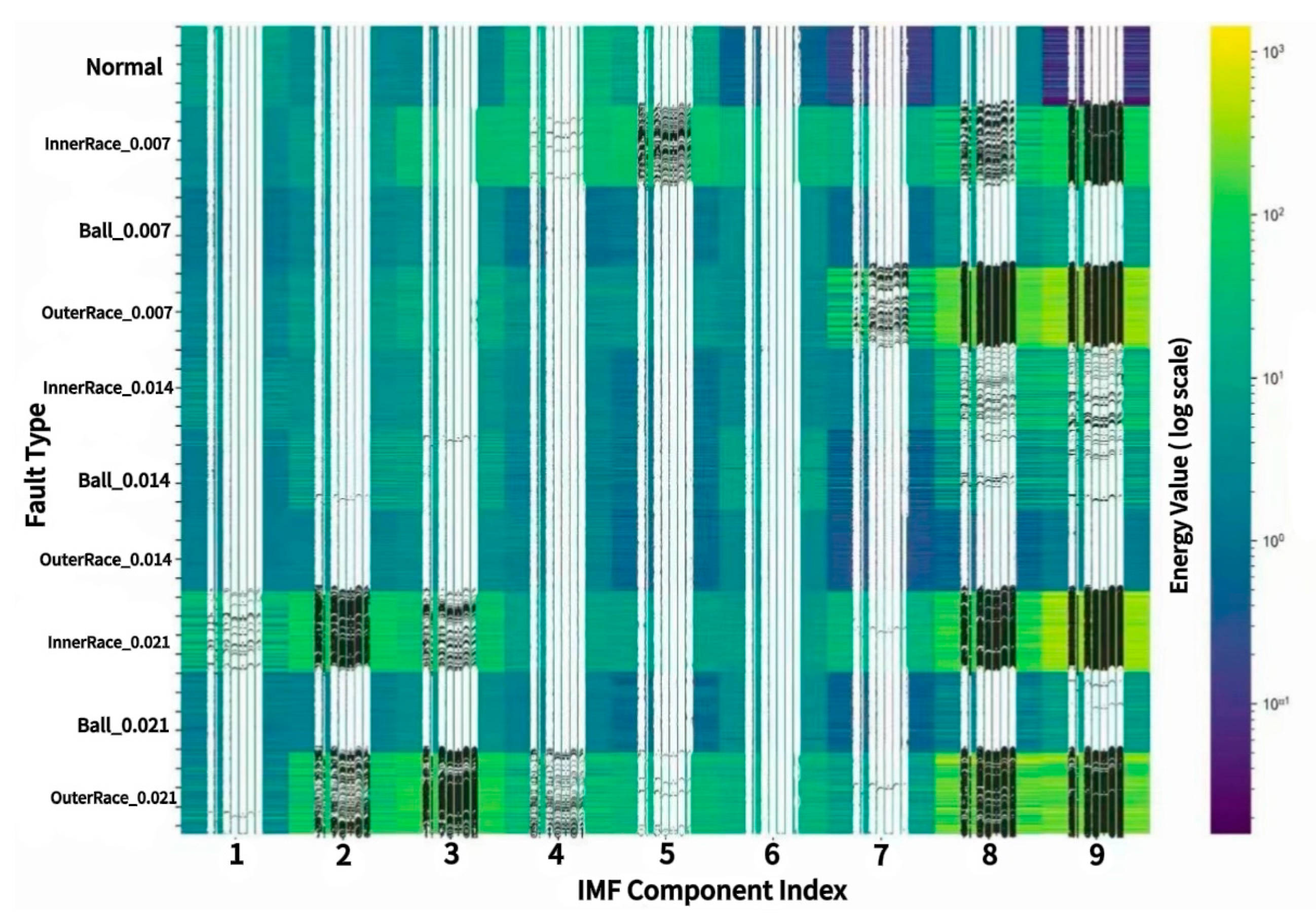

Step1: Mode Decomposition and Feature Tensor Construction

For the input signal , the VMD algorithm is employed to decompose it into Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs), denoted as . VMD achieves mode clustering and frequency band separation through the optimization objective in Equation (1). The decomposition is performed using an iterative Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM), ensuring convergence to a stable spectral decomposition result.

Upon completion of the decomposition, statistical features in the frequency domain are extracted from each IMF to form a feature vector

,including metrics such as energy, entropy, mean square root,etc. All feature vectors are then sorted in descending order according to the center frequency of the corresponding modes, and stacked to construct a two-dimensional feature tensor:

Here, X serves as the final feature representation tensor for input into neural networks. It has advantages in structural regularity, information compactness, and frequency consistency, facilitating stable and efficient downstream modeling.

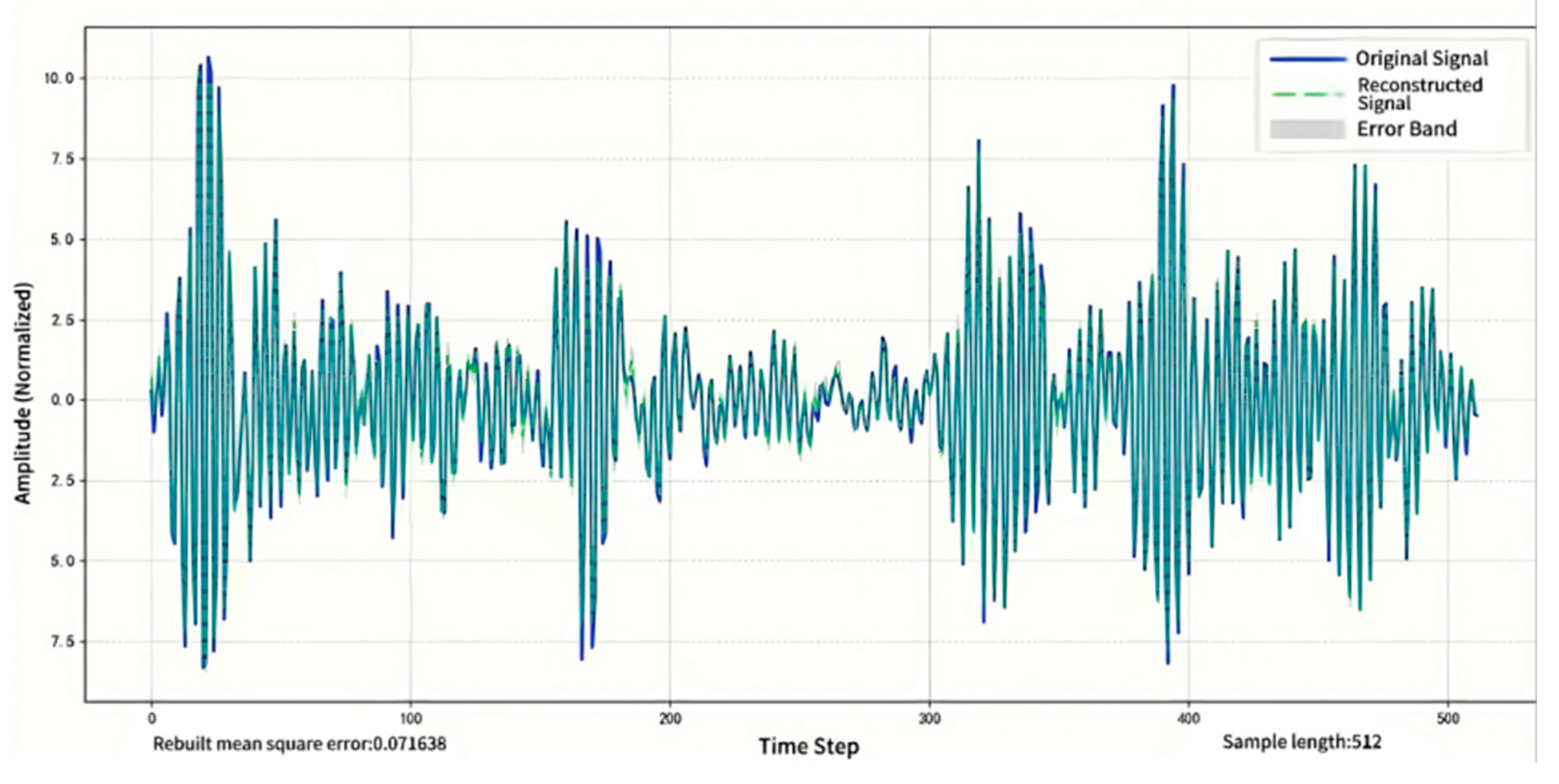

Step 2: Signal Reconstruction and Structural Fidelity Design

To verify whether the constructed features retain frequency separation while accurately reconstructing the original signal characteristics, a reconstruction mechanism is designed to assess fidelity. Each IMF is summed over time to reconstruct the signal, expressed as:

Here, denotes the signal reconstructed from the IMFs. The reconstruction accuracy is evaluated by comparing it with the original signal , using Mean Squared Error (MSE) as the metric to measure structural fidelity.

Here, denotes the signal length, and the MSE represents the average deviation between the reconstructed signal and the original signal. This metric reflects the effectiveness of the reconstruction process in preserving the signal’s dynamic characteristics. A lower MSE indicates greater information retention during IMF decomposition, resulting in more reliable and expressive representations. Furthermore, this structure enables verification of both the frequency stability of the modal sequence and inter-sample consistency, thereby providing a semantically interpretable and controllable input foundation for subsequent convolutional modeling.

3.3. Phase III: L-CNN

After multi-scale modal feature extraction by QD-VMD, an efficient classifier is needed to achieve high-precision fault identification across different modalities and scenarios. Given that real-world industrial deployments often rely on resource-constrained edge devices (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson Nano), this study proposes a Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network (L-CNN) to balance diagnostic speed, energy efficiency, and classification accuracy.

3.3.1. Network Architecture Design

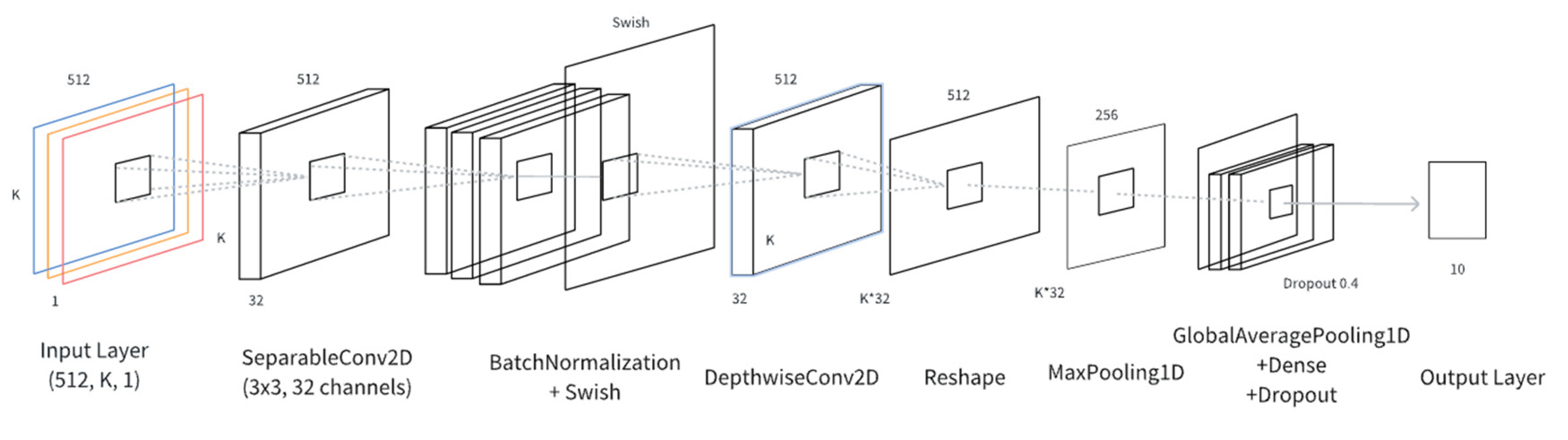

The overall architecture of the proposed L-CNN is illustrated in

Figure 2, which outlines the modular structure and feature flow of the network. This facilitates understanding of parameter connectivity and information propagation across different stages of the model.

As shown in

Figure 2, the input to the model is a modal fusion feature tensor of size (512,K,1), where 512 denotes the number of time steps, and K is the number of modes extracted by QD-VMD. The architecture is designed as follows:

(1) Layer: The input tensor is processed by a SeparableConv2D layer with a kernel size of 3×3, 32 output channels, and ‘same’ padding. This layer decouples spatial and channel-wise convolutions, significantly reducing the number of parameters and computational cost while maintaining effective feature perception.

(2) Layer: The extracted feature maps are normalized to accelerate training and improve numerical stability. This is followed by a Swish activation function, which enhances non-linear representation capabilities. Its smooth derivative characteristics help mitigate gradient vanishing in lightweight models.

(3) Layer: A depthwise convolution is applied to each channel independently, allowing for enhanced modeling of local patterns within each mode and further improving computational efficiency. The output is then reshaped into a one-dimensional sequence via a Reshape Layer to align with the subsequent temporal processing steps.

(4) Layer: A max pooling operation with a pool size of 2 is used to downsample the sequence, retaining salient features and reducing redundancy and model complexity. To further improve responsiveness to key features, a lightweight Channel Attention Mechanism is introduced, dynamically enhancing fault-relevant information by learning the importance weights of each channel.

(5) Layer: In the aggregation stage, global average pooling is applied across all channels, replacing fully connected layers to compress features, reduce parameter redundancy, and improve robustness to input variations. A Dense Layer with 128 units is then used, activated by the Swish function and regularized with an L2 penalty (coefficient: 1e-4), enhancing feature fusion while preventing overfitting. To further improve generalization under small-sample conditions, a Dropout Layer (dropout rate: 0.4) is applied to simulate input noise and increase training robustness.

(6) Output Layer: A Dense output layer with 10 units and a Softmax activation is used to produce the final classification results, mapping high-dimensional features to probabilities over ten bearing fault categories.

To support the architectural design,

Table 1 lists the parameter settings and output dimensions of each layer in L-CNN, clearly indicating the model compression path and key computational stages,where K is the number of models.

3.3.2. Regularization and Model Compression

To prevent overfitting and control model size, L-CNN incorporates regularization and compression mechanisms in the fully connected layers. Specifically, L2 regularization is applied via kernel_regularizer=tf.keras.regularizers.l2(1e-4) to penalize large weights, promote network sparsity, and reduce storage overhead.

Additionally, strategic Dropout with a rate of 0.4 is introduced after the Dense layer to enhance generalization capability. Unlike some studies that apply dropout directly to convolutional layers, this design restricts dropout to the fully connected layers, effectively avoiding interference with feature extraction efficiency while significantly reducing inference computational cost.

3.3.3. Overall Architectural Optimization

The L-CNN architecture employs a hierarchical feature extraction strategy, progressing from shallow to deep layers to incrementally aggregate both local and global information. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the initial layers use SeparableConv2D to extract localized receptive features, followed by DepthwiseConv2D and a channel attention mechanism to enhance feature representation. Final classification is performed using GlobalAveragePooling1D and Dense layers.

Additionally, L-CNN supports multi-branch inputs, enabling parallel processing of various feature types extracted by QD-VMD, such as time-domain features (e.g., peak value, kurtosis) and frequency-domain features (e.g., spectral magnitude, peak frequency). Select layers incorporate a weight-sharing mechanism to reuse parameters across branches, improving both training and inference efficiency. This design allows L-CNN to flexibly adapt to a wide range of fault diagnosis scenarios, including--but not limited to--bearings, gearboxes, and power equipment in industrial systems.

3.3.4. Quantization and Deployment Optimization

To meet the latency and power constraints of edge devices, L-CNN is designed to be fully compatible with INT8 quantization. All convolutional layers are coupled with Batch Normalization and Swish activation functions to maintain inference accuracy after quantization. Intermediate feature tensor dimensions are carefully reduced--for example, from (512, K, 32) to lower channel dimensions--to minimize memory access and energy consumption.

At inference, computational complexity is controlled to approximately 0.00104 GFLOPs, ensuring strict adherence to low-latency and low-power requirements for industrial edge deployment.

With this design, the final L-CNN model supports joint modeling of multi-modal vibration and electrical signal features extracted by QD-VMD. The total parameter count is approximately 5.5 × 10⁴, with a memory footprint of about 0.21 MB, demonstrating strong model compactness and adaptability. The architecture integrates depthwise separable convolutions, Batch Normalization, Swish activation, channel attention, and global pooling-based classification, achieving an effective balance between computational efficiency and expressive capability.

6. Discussion

The proposed QDVMD-LCNN algorithm exhibits significant advantages in bearing fault diagnosis and cross-domain generalization. Nevertheless, as a novel hybrid approach, several technical and practical aspects warrant further investigation. The following discusses key limitations and potential directions for future optimization from the perspectives of core module boundaries and the stability of module interactions.

(1) Mechanism Characteristics and Potential Challenges of QIPO

QIPO achieves structured parameter encoding and efficient search through quantum state probability modeling and phase interference in rotation gates. Its qubit-based representation enhances the modeling of parameter coupling and leads to superior convergence in non-convex spaces. However, this mechanism is currently applied to low-dimensional parameter spaces (two dimensions in this study). Extension to higher-dimensional scenarios may encounter “quantum state explosion,” resulting in sharply increased computational complexity. Effectively balancing rotation gate updates and avoiding local minima remains a challenging issue.

(2) Dual Functions and Scenario Adaptation Boundaries of VMD

VMD serves not only as a tool for signal denoising and frequency decomposition but also as the backbone for organizing feature tensors, thereby impacting downstream model performance. By tuning its parameters, VMD produces structurally differentiated IMFs that capture essential frequency components. However, its ability to handle non-periodically modulated signals (e.g., hydraulic system pulse noise) is limited. Future research could explore variational hierarchical wavelets or multi-scale VMD to improve adaptability to complex, nonlinear, and mixed-frequency signals.

(3) Efficiency–Accuracy Trade-off in L-CNN

L-CNN achieves extreme model compactness (with only 5.5 × 10⁴ parameters) through depthwise separable convolutions and global pooling, supporting the hypothesis that well-structured features allow shallow networks to perform effective classification. However, when feature coupling is strong, overly shallow architectures may create classification bottlenecks. Investigating dynamic network architectures, such as adaptive depth adjustment based on input complexity, could further enhance model adaptability.

(4) Robustness and Chain Risks in the Three-Stage Interactive Structure

The strong coupling among the optimization, decomposition, and modeling modules forms a positive feedback loop, where parameter optimization improves decomposition quality and simplifies downstream learning. Nevertheless, performance degradation in any single module (e.g., QIPO being trapped in a local optimum) can trigger cascading failures. Strengthening inter-module feedback mechanisms, such as refining VMD parameters based on classification loss, is necessary to enhance overall system robustness.

These limitations do not detract from the effectiveness of the algorithm; rather, they highlight promising directions for further improvement. By advancing parameter optimization dimensionality, enhancing signal decomposition adaptability, developing dynamically adjustable network architectures, and reinforcing module interaction stability, the potential of QDVMD-LCNN for deployment in complex industrial environments can be further realized.