1. Introduction

Ultrasonography is the most widespread diagnostic imaging modality. Ultrasound examinations are performed by physicians of various specialties as well as representatives of other medical professions, both for diagnostic purposes and during interventional procedures. The mobility of ultrasound machines with the possibility of imaging in real-time, safety resulting from the lack of medical contraindications and a wide range of applications contribute to the growing number of ultrasound examinations performed worldwide [

1]. However, the utility and popularity of ultrasonography may cause work overload and the development of work-related musculoskeletal diseases (WMSDs) in sonographers. According to our previous study 65,6% of sonographers experience pain during or shortly after performing ultrasound examinations which is most reported in the cervical and lumbosacral spine, shoulder and the wrist [

2]. These findings are in line with the results of similar studies [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Work efficiency, which is significantly influenced by ergonomics, affects the quality of work and the achievement of assumed goals. The sonographers’ discomfort may affect the course and accuracy of the examination as well as its result. To counteract WMSDs, associations related to healthcare and medical ultrasonography had proposed standards and recommendations regarding work ergonomics during ultrasound examinations [

8,

9,

10,

11]. These preventive principles are mostly based on observational studies of forced body positions and subjective opinions of sonographers regarding discomfort accompanying sonographic examinations, and incorporate recommendations developed for similar workstations, including computer work [

12,

13]. To date, there are only a few studies that quantitatively measured joint loads, and even fewer that had used dedicated equipment for measurements of the body kinematics in sonographers. Most of these studies relied on video recordings of physicians and technicians performing ultrasound examinations [

14,

15,

16,

17]. The remaining research implemented electrogoniometers and electromyography (EMG) to assess the biomechanics of the upper limb and spine [

14,

17,

18]. Various validated measurement methods are used to identify incorrect postures and points of physical overload and to assess the risk of WMSDs, including the Rapid Upper Limb Assessment (RULA), the Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA), the Ovako Working Posture Analysis System (OWAS) or the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) regulations [

19,

20,

21,

22]. A comprehensive review by Kee indicated that the RULA method is significantly stronger associated with WMSDs than the REBA and OWAS [

23]. Both RULA and REBA methods implement a point converter for the position angles of the arm, forearm and the wrist, as well as the neck, trunk and legs. Measurements are taken in the sagittal plane separately for each of the upper limb. The final score includes additional points for coronal parameters such as raised shoulder, abducted arm, moving the forearm and the wrist sideways from the midline, making RULA/REBA methods highly suitable for the analysis of sonographers position.

The purpose of this study was to measure, analyze and quantify the musculoskeletal loads in sonographers performing breast and abdominal ultrasound examinations with dedicated biomechanic methodology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This prospective study included 5 radiologists, three women and two men aged 29 to 39, who were substantially trained in breast and abdominal ultrasonography. The experience of the study participants ranged from 12 months (in this case, if at least 20 ultrasound examinations were performed per week) to 12 years.

The exclusion criteria for study participants, apart from the lack of required experience, included:

• previous musculoskeletal surgeries,

• history of serious injuries,

• the presence of endoprostheses or skeletal stabilizing implants,

• chronic and symptomatic diseases of the musculoskeletal system,

• acute pain or exacerbation of chronic pain during the study period,

• chronic or occasional (within 7 days preceding the study) use of painkillers, anti-inflammatory drugs, and antiepileptic drugs.

Ultrasound examinations were performed during routine patients’ follow-up in the Department of Diagnostic Imaging and Interventional Radiology of the University Clinical Center, Katowice, Poland. Sonographers performed examinations in the same setting, using the same equipment, and were sitting on a stool without lumbar support. All participants were right-handed. Each participant performed complete breast and abdominal ultrasound twice, amounting to 10 sets of breast and abdominal ultrasound examinations. A single set consisted of abdominal and breast examinations performed on one patient in continuity. A total of 10 patients participated in the study.

Both doctors and patients gave informed written consent to participate in the study. The study protocol has been approved by the bioethics committee of the Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland (BNW/NWN/0052/KBI/2/24).

2.2. Kinematic Analysis

Sonographer kinematics were monitored using Noraxon Ultium Motion system (Noraxon, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA). Sixteen sensors were attached with straps and adhesive tape symmetrically on the participants hands, forearms, arms, feet, lower legs and thighs as well as on the head, upper, mid and lower back, according to the previously described protocol [

24]. Sensor data was recorded in real time and analyzed with Noraxon MR3.18 software (

Figure 1).

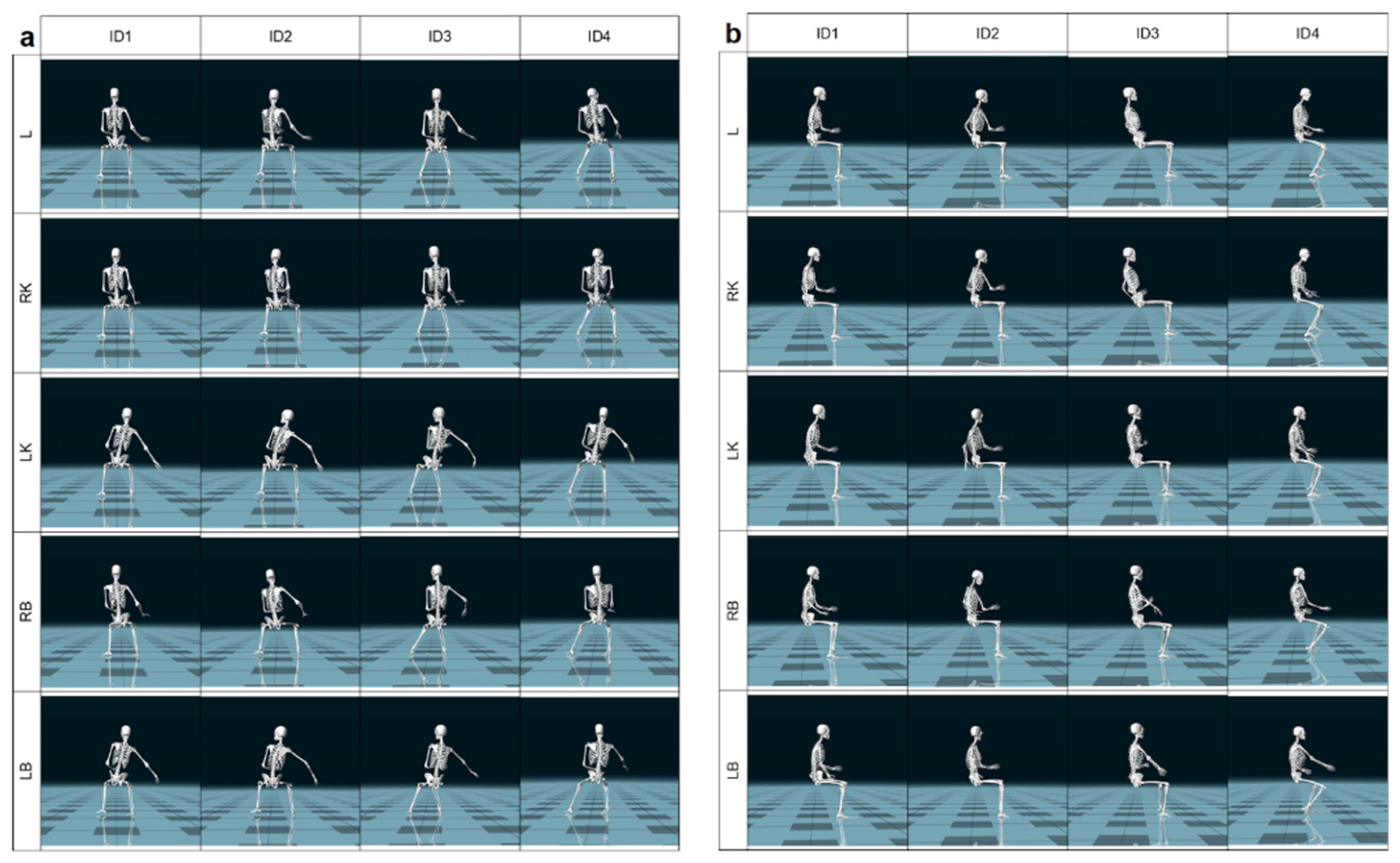

Based on the analysis of the kinematic recordings five critical positions of the transducer were identified and located over the right breast (RB), left breast (LB), liver (L), right kidney (RK) and left kidney (LK) (

Figure 2). The analysis included shoulder joint abduction, elbow joint flexion, dorsal/palmar wrist flexion, head flexion in the sagittal plane, and trunk flexion in the sagittal plane, which were considered for the transducer positions assessed. Additionally, for the REBA method, hip and knee joint flexions were also considered.

2.3. Biomechanical Analysis

The obtained angle measurements were analyzed according to the RULA and REBA methods [

19,

20]. The assessment was conducted using the official RULA and REBA assessment sheets. Both methods were developed to assess the risk of musculoskeletal disorders and the identification of physical exertion related to body position during work. For the RULA method, the analysis included postural scores for Group A and Group B, as well as Scores A and B derived from dedicated scoring tables. Additionally, for both groups, the muscle score, reflecting posture stability, and the force/load score, related to the weight handled by the physician—specifically the ultrasound transducer were assessed.

Similarly, for the REBA method, Scores A and B were calculated for both Group A and Group B based on the respective assessment tables. For Group A, only the force/load score—reflecting the load handled during the examination was evaluated. In contrast, for Group B, in addition to the force/load score, the coupling score, related to the quality of grip on the ultrasound transducer, and the activity score, capturing the frequency and extent of postural changes during the examination, were also assessed.

2.3.1. RULA Method

To perform the analysis using the RULA method, data recorded with the Noraxon Ultium Motion system were segmented according to a previously described framework. This approach allowed for the identification of anatomical structures most burdened within the musculoskeletal system of the diagnostic physician. Additionally, complete recordings of abdominal and breast examinations were analyzed to assess the overall ergonomic risk and the potential for occupational diseases resulting from tasks performed by sonographers.

The RULA method is based on specially designed assessment sheets that enable a systematic evaluation of musculoskeletal load. The ergonomic assessment is conducted using images or video recordings captured in the sagittal plane [

25,

26].

The first step in the analysis involves evaluating flexion at the shoulder joint, followed by flexion at the elbow joint, wrist dorsiflexion/palmar flexion, and wrist twist. Based on these measurements, Group Score A is determined using Table A, which pertains to the upper body. Two additional indicators are then incorporated: Muscle Use Score (non-static posture—frequent changes in position more than 4 times per minute) and Force/Load Score (less than 4.4 lb—holding only the ultrasound transducer). These values are added to compute the final Group A Score.

Next, Group B is assessed—this includes the posture of the head, trunk, and legs. As the clinician was seated without backrest and the legs were in contact with the ground, the legs were considered as providing support. Based on these observations, the Group Score B was determined using Table B. Similarly to Group A, indicators of Muscle Use Score (non-static posture) and Force/Load Score (again below 4.4 lb) were added. The sum of these values constitutes the Group B Score.

In the final step, Table C is used to combine the upper body (Group A) and lower body (Group B) scores to calculate the overall RULA score, which reflects the general level of ergonomic risk.

The ergonomic risk levels, as defined by the RULA method, are defined as follows: 1-2—acceptable posture; 3-4—further investigation, change may be needed; 5-6—further investigation, change soon; ≥7—investigate and implement change.

2.3.2. REBA Method

The analysis was supplemented with an assessment using the REBA method, which allowed for a comparison of results and a more detailed identification of ergonomic risk factors. The REBA analysis was conducted using previously prepared data recorded with the Noraxon Ultium Motion system, following the segmentation and data processing procedure described earlier.

The REBA method is a modification of the RULA method and is also based on specially designed assessment worksheets that enable a systematic evaluation of musculoskeletal load. Like RULA, the ergonomic assessment using REBA is conducted based on images or video recordings taken in the sagittal plane [

25,

27].

In the REBA method, Group A refers to the posture of the head, trunk, and legs, which were evaluated using dedicated assessment sheets. The first step involved scoring the position of the head, followed by the trunk, and finally the legs. The legs were assigned the maximum score, as the physician was in a seated position. Based on the obtained values, the Posture Score A was determined using Table A. Subsequently, the Force/Load Score was assessed—here, the lowest value (<11 lb) was assigned, as the physician was only holding the ultrasound probe. The final Score A was calculated as the sum of Group Score A and the Force/Load Score.

Next, Group B was evaluated, corresponding to the upper extremities. Points were assigned for flexion in the shoulder, elbow, and wrist joint (dorsal/palmar flexion). Based on these values, Posture Score B was determined using Table B. An additional component, the Hand Coupling Score, was also assessed. In this case, a value corresponding to Well-Fitting Handle and Mid-Range Power Grip was selected, as the ultrasound probe was ergonomically shaped and fit well in the hand. The final Score B was calculated as the sum of the Posture Score B and the Hand Coupling Score.

In the final stage of the analysis, the Activity Score was determined. One point was added for repeated small range actions (more than four times per minute). The final REBA score was calculated using the values from Table C, based on Score A and Score B, to which the Activity Score was added.

The levels of ergonomic risk according to the REBA method are defined as follows: 1—negligible risk; 2-3—low risk, change may be needed; 4-7—medium risk, further investigate, change soon; 8-10—high risk, investigate and implement change; ≥11—very high risk, implement change.

3. Results

As a result of the data quality verification process, all incomplete recordings and those containing registration errors were excluded. Ultimately, 4 out of the 10 recorded sessions from 4 out of 5 radiologists (ID1-ID4) were qualified for the analysis. The evaluation was conducted using two ergonomic assessment methods, namely RULA and REBA. The results are presented separately according to the method used.

3.1. RULA Analysis

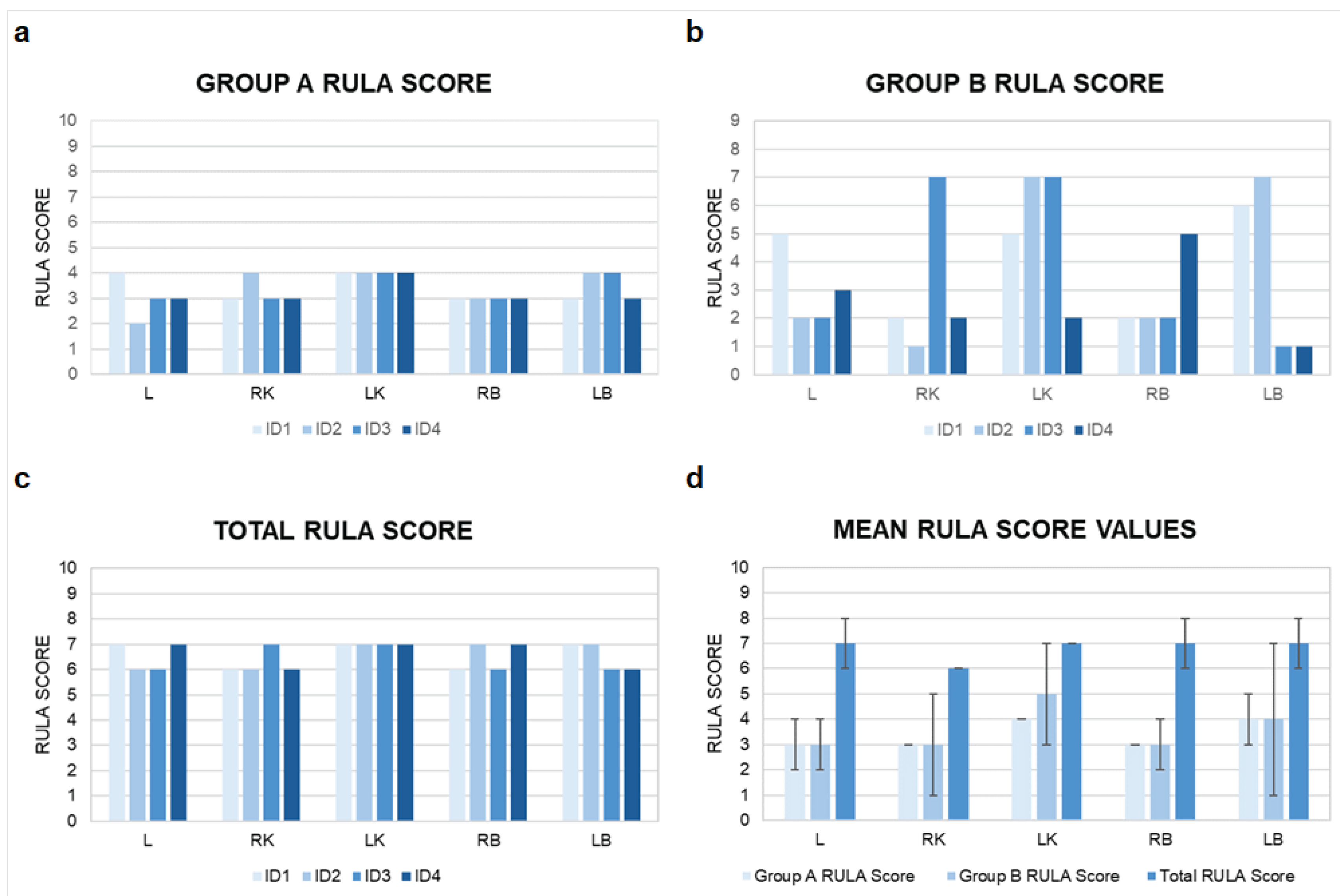

The results obtained using the RULA method are presented collectively in

Figure 3.

In the analysis conducted for Group A, which relates to the loading of the upper limb, imaging of the left kidney was consistently associated with the highest level of musculoskeletal load. It is important to emphasize that due to the fixed position of the ultrasound machine and the operator’s placement on the right side of the patient, accessing the left side of the body necessitated a non-physiological working posture. This included twisting and leaning the torso to the left, along with increased shoulder flexion of the right upper limb, which was the dominant working limb. Such a biomechanical arrangement promotes overload, particularly in the right upper limb.

For anatomical structures located closer to the examiner’s working position—such as the right kidney or right breast—a more neutral and ergonomically favorable posture could be maintained. This was reflected in lower RULA scores. The individual RULA scores for Group A indicate that left kidney imaging generates loading levels within the range of 3–4. Other anatomical structures received scores in the 2–3 range.

In Group B, which pertains to the loading of the torso (i.e., head, trunk, and legs), the highest levels of individual musculoskeletal load occurred during the imaging of the left kidney and left breast, which were scored the highest by most examiners (up to 7 RULA points). These high scores primarily resulted from torso positioning—significant forward flexion (sagittal plane), lateral bending, and rotation. Thus, torso posture was the main factor influencing the final score for this group. An exception was ID4, for whom the highest load was recorded during right breast imaging, possibly due to individual differences in scanning technique or workstation arrangement.

The analysis of total RULA scores indicates that musculoskeletal strain is consistently high across all evaluated anatomical regions, with particularly substantial loading observed during imaging of the left kidney, liver, and both breasts.

When analyzing group mean values, left kidney imaging was associated with the highest load among all structures, with mean RULA scores of 4 in Group A and 5 in Group B. Due to the high total scores also observed for the liver and both breasts, urgent consideration should be given to optimizing scanning techniques and workstation ergonomics to minimize overload risk.

Low standard deviations confirm that the high musculoskeletal load is consistent, regardless of individual scanning technique or examiner posture. This indicates that the risk of overload is systemic, not merely a result of inter-individual differences, emphasizing the need for broad ergonomic improvements.

The analysis of RULA scores for diagnosticians’ posture throughout the entire duration of the examination revealed that although the average values in Groups A and B may appear relatively low, the overall mean total score was 7 (

Table 1).

3.2. REBA Analysis

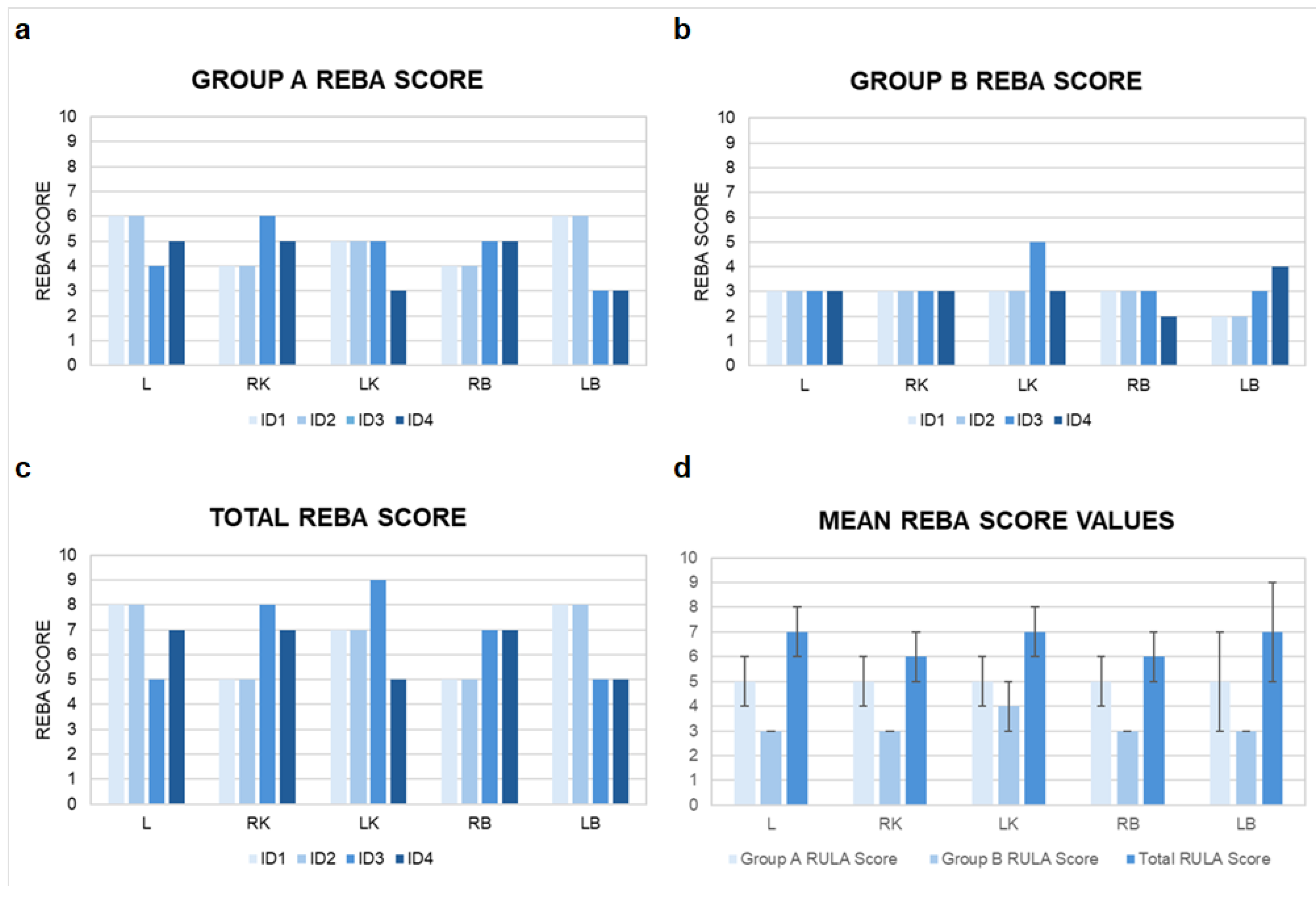

The aggregated results obtained using the REBA method are presented in

Figure 4.

The individual analysis of REBA scores for Group A, concerning the load on the body trunk (i.e., head, torso, and legs) during diagnostic procedures, revealed the highest levels of musculoskeletal strain during imaging of the liver and left breast. The REBA scores for these anatomical locations were most frequently in the range of 5–6. It is particularly noteworthy that the high scores were primarily attributable to torso positioning—including significant forward flexion, rotation, and lateral bending—which contributed most heavily to the overall strain in this parameter. Torso posture proved to be the decisive factor influencing the REBA outcomes in this group.

The REBA score analysis for Group B, which focuses on the upper limb load, indicates moderate ergonomic risk levels. Most individual assessments fell within the 2–3 point range. An exception was noted in the case of left kidney imaging by examiner ID3, where the REBA score reached 5, indicating a moderate risk level. This result highlights the necessity for a more detailed analysis and potential adjustments in workstation configuration or scanning technique. Other anatomical structures—including the liver, right kidney, and both breasts—showed no elevated scores, implying more ergonomic examiner postures during those procedures.

The analysis of total REBA scores, reflecting the overall musculoskeletal load during imaging of specific anatomical structures, showed consistently elevated values across all examined cases. The highest loads were associated with imaging of the left and right kidneys, with scores up to 9, indicating a very high overload risk. Lower scores (approximately 5) were observed during imaging of the right kidney and right breast, denoting moderate strain that still warrants ergonomic attention.

The analysis of mean REBA scores for each anatomical structure in both Group A and Group B indicates a substantial musculoskeletal load during diagnostic activities. Total REBA scores for most structures were in the 6–7 range. Notably, the highest mean REBA scores were recorded for the left side of the body in Group A, with an average score of 5, closely followed by Group B, with an average of 3. Similarly, right kidney and right breast imaging yielded scores between 3 and 5, indicating a moderate risk of strain. Analysis of standard deviations showed low variability in most cases, suggesting that musculoskeletal strain was relatively uniform and not significantly influenced by individual differences in examiner technique. An exception was noted for left breast imaging in Group A, which exhibited slightly higher variability, possibly reflecting greater diversity in examiner posture during this particular examination.

The analysis of REBA scores for examiner postures throughout the entire examination procedure reveals that, although the average values in Groups A and B fall within the moderate range, the overall mean score reaches 5 (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

In the analysis conducted for RULA Group A relating to the upper limb the examination of the left kidney was associated with the highest level of musculoskeletal load, which included twisting and leaning the torso to the left, along with increased shoulder flexion. Left kidney scans also showed the highest loads when analyzing group mean RULA values. Other organs received scores in the 2–3 range, suggesting postures that are close to acceptable or require only moderate attention. This classification highlights the need to pay particular attention to the ergonomics of scanning structures located contralaterally to the dominant hand to prevent upper-body musculoskeletal overload. Adequately, the REBA score analysis for Group B indicated moderate ergonomic risk levels suggesting a need only for ongoing monitoring or minor adjustments. Generally low to moderate scores may reflect favorable working conditions for the upper limb. However, even isolated instances of elevated strain emphasize the importance of accounting for individual postural differences and scanning techniques in ergonomic risk evaluation. Regardless of the specific anatomical location, total REBA scoring confirmed a significant and persistent risk of musculoskeletal strain, highlighting the necessity for ergonomic optimization in clinical environments. The particularly high values observed during imaging of left-sided structures likely stem from the need to operate in torso rotation and forward bending, which contributes to overloading and signals a need for organizational and technical adjustments to the workstation.

In RULA Group B, which concerns the loads occurring in the torso, the highest levels of musculoskeletal loads occurred during the imaging of the left kidney and the left breast. Based on the average RULA scores for the anatomical structures in both groups, it can be concluded that the total musculoskeletal load is high. For almost all evaluated structures—except the right kidney—the total RULA score was 7, indicating a need for immediate intervention. The individual analysis of REBA scores for Group A revealed the highest levels of musculoskeletal strain during imaging of the left breast and the liver. In the case of both RULA and REBA body trunk analyzes, the high scores were primarily attributable to significant forward flexion, rotation, and lateral bending of the torso. Due to the proximity of the right side of the patient to the examiner, a more ergonomic posture was often possible during the imaging of right-sided structures, such as the right kidney and right breast. These cases were associated with lower REBA scores, reflecting improved torso positioning and reduced overall musculoskeletal burden. Although no instances of very high risk levels were observed in this group, the findings clearly underscore the importance of ergonomic consideration—particularly with respect to torso alignment—when planning workstation setups and examination techniques to minimize musculoskeletal overload.

Consistently high total RULA scores (>5) indicate musculoskeletal strain across all anatomical regions, particularly the left kidney, liver, and both breasts. High and comparable RULA scores for nearly all structures suggest that the positioning of sonographers and scanning techniques generate significant muscular tension and postural overload across various body regions, regardless of the specific area being examined. According to the adopted risk scale, scores in the range of 5–6 indicate the urgent need for further investigation and ergonomic adjustments, while scores of 7 or higher reflect a high risk of injury and the immediate need for corrective measures. Comparable results were seen in the case of total REBA scores, which showed consistently elevated values across all examined cases ranging from 5 to 9. According to the REBA risk classification, scores of 8–10 indicate high risk, requiring immediate corrective actions, while values in the 4–7 range represent moderate risk, also necessitating ergonomic intervention. REBA scores point to a high ergonomic risk particularly during imaging of the left breast and liver, where scores reached 8. These patterns indicate an overall high level of ergonomic burden during ultrasound examinations, emphasizing the need for optimization of both workstation design and scanning technique.

Previous research on sonographers had shown similar conclusions regarding RULA scores. One study examined the musculoskeletal loads according to the RULA method during ultrasound examinations of the thyroid gland, abdominal cavity and venous thrombosis of the lower limbs [

14]. The measurements were performed based on the analysis of the video recording during the ultrasound examinations and using electrogoniometers. In this study, all scans showed significant Group A scores resulting from awkward upper limb postures, forceful manual exertions, and applied static muscle contraction. Group B scores were consistently found to be higher for left sided organs which required the most immediate attention. Right sided and unilateral scans were found to require additional investigation and possible changes, especially regarding the right upper limb. In a study by Habes et al. the main ergonomic stress factors observed were right shoulder flexion and abduction, sustained static forces, and various types of transducer grips [

15]. Friesen et al. determined more detailed values of sonographers joint angles in which trunk side flexion toward the patient ranged from 5° to 10°, shoulder abduction from 10° to 60°, shoulder flexion from 30° to 40°, and elbow flexion from 30° to 110° [

16]. A different video-based study showed sonographers spend 68% of scanning time with >30o shoulder abduction, 63% time with >30o shoulder outward rotation, and 37% time with the neck bent forward, laterally or twisted >20o [

17]. The shoulder was unsupported or static for 73% of scanning time mainly during carotid ultrasound compared with abdominal, obstetrical or lower limbs examinations. For patients with a larger abdomen more wrist flexion and extension were used to reach the closer and further areas of the abdomen [

15]. Sonographers also had to twist the neck to the left to view the monitor, flex and abduct the left shoulder, and extend the elbow to operate the control panel. Based on the EMG analysis of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus and trapezius muscles the static amplitude probability distribution functions exceeded 3% maximum velocity contraction corresponding to a medium risk rating for shoulder and neck disorders [

17]. The same study reported an average grip force during scanning of 4 kg with the peak forces reaching over 27 kg. The minimal applied force of 1 kg provides little or no opportunity to rest and is associated with increased risk of hand/wrist cumulative trauma disorders, including carpal tunnel syndrome [

28]. Additional identified factors contributing to the loads experienced by the sonographers were bed width (higher loads observed for wide beds) and the lack of elbow support [

15].

The analysis of scores for sonographers’ postures throughout the entire duration of both breast and abdominal examinations revealed that the average values in Groups A and B were low and moderate for RULA and REBA methods, respectively. Nevertheless, the overall mean total score reached 7 for RULA indicating a high level of musculoskeletal strain, and 5 in case of REBA, corresponding to a notable level of strain. The persistence of such high values underscores the urgent need to optimize working conditions and adapt scanning techniques to effectively reduce musculoskeletal loading among sonographers. The main emphasis should be on maintaining a neutral body position during sonographic examinations, education and training in ergonomics as well as sensible management of the work schedule. Continuous monitoring and the implementation of ergonomic interventions are essential for improving workplace comfort and occupational safety.

4.1. Study Limitations

One limitation of our study is the small sample size. Only 4 out of 10 sets of examinations from 4 out of 5 sonographers were analyzed due to the presence of incomplete data or incorrect data transfer caused by the sensor’s signal interference. The inclusion criterion for the analysis was a complete recording of both breast and abdominal ultrasound enabling the selection of key moments of the examination for each critical position. An additional limitation of the study is the lack of assessment of the influence of sonographers’ and patients’ anthropometric data on kinematic results. However, a reliable assessment would require examining a large group of individuals with a wide range of body types.

4.2. Study Strengths

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study utilizing motion sensors to assess the kinematics of sonographers. The use of sensors allowed to obtain the most appropriate and precise measurements and therefore to exclude any measurement errors related to the assessment of body position in a single plane. It is also the first study to analyze biomechanics and postural loads during breast ultrasound examinations.

5. Conclusions

The highest loads among all analyzed structures were measured over the left kidney and the left breast but also the liver. Anatomical structures located closer to the examiner’s working position determined a more neutral and ergonomically favorable posture. Adopting a forced body position during ultrasound examinations seems unavoidable, therefore solutions should be sought that will reduce physical strain, including training in work ergonomics and developing supporting devices that relieve the musculoskeletal system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.W. and R.M.; methodology, M.W., R.M., A.G.-K. and A.M.-B.; software, R.M. and A.G.-K.; validation, R.M., A.G.-K. and M.H.; formal analysis, R.M., A.G.-K., M.W. and M.H.; investigation, M.W., M.H. I.R. and M.C.; resources, M.W., K.S.-R., A.G.-K. A.M.-B. and R.M.; data curation, M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.W., M.H.; writing—review and editing, A.G.-K. and A.M.-B. and R.M.; visualization, M.W., M.H.; supervision, K.S.-R., A.G.-K. and R.M.; project administration, M.W.; funding acquisition, M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the Medical University of Silesia, grant number BNW-2-075/K/5/K.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland (BNW/NWN/0052/KBI/2/24, 30.01.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Winder, M.; Owczarek, A.J.; Chudek, J.; Pilch-Kowalczyk, J.; Baron, J. Are We Overdoing It? Changes in Diagnostic Imaging Workload during the Years 2010–2020 including the Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciekalski, M.; Rosół, I.; Filipek, M.; Gruca, M.; Hankus, M.; Hanslik, K.; Pieniążek, W.; Wężowicz, J.; Miller-Banaś, A.; Guzik-Kopyto, A.; Michnik, R.; Winder, M. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Polish sonographers-A questionnaire study. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2024, 53, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros-Gomes, S.; Orme, N.; Nhola, L.F.; Scott, C.; Helfinstine, K.; Pislaru, S.V.; Kane, G.C.; Singh, M.; Pellikka, P.A. Characteristics and Consequences of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Pain among Cardiac Sonographers Compared with Peer Employees: A Multisite Cross-Sectional Study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2019, 32, 1138–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, K.; Roll, S.; Baker, J. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders (WRMSD) Among Registered Diagnostic Medical Sonographers and Vascular Technologists: A Representative Sample. J Diagn Med Sonogr 2009, 25, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremark Simonsen, J.; Axmon, A.; Nordander, C.; Arvidsson, I. Neck and upper extremity pain in sonographers—Associations with occupational factors. Appl Ergon 2017, 58, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogan, A. Pain Levels and Injuries by Sonographic Specialty: A Research Study. J Diagn Med Sonogr 2021, 38, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wareluk, P.; Jakubowski, W. Evaluation of musculoskeletal symptoms among physicians performing ultrasound. J Ultrason 2017, 17, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AIUM Practice Principles for Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorder. J Ultrasound Med 2023, 42, 1139–1157. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Society of Diagnostic Medical Sonography. Available online: https://www.sdms.org/docs/default-source/Resources/work-related-musculoskeletal-disorders-in-sonography-white-paper.pdf (accessed on 31.03.2025).

- The Australasian Sonographers Association. Available online: https://www.sonographers.org/publicassets/e02a231f-e2de-ef11-9137-0050568796d8/SDMS_Industry_Standards_Aug17.pdf (accessed on 31.03.2025).

- The Society of Radiographers. Available online: https://www.sor.org/getmedia/d25064fe-ad05-42c0-a777-efaca0d2eb35/sor_industrystandards_prevention_musculoskeletal.pdf_1 (accessed on 31.03.2025).

- Harrison, G.; Harris, A. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in ultrasound: Can you reduce risk? Ultrasound 2015, 23, 224–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zangiabadi, Z.; Makki, F.; Marzban, H.; Salehinejad, F.; Sahebi, A.; Tahernejad, S. Musculoskeletal disorders among sonographers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2024, 24, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, D.R.; Campbell-Kyureghyan, N.H. Quantification of scan-specific ergonomic risk-factors in medical sonography. Int J Ind Ergon 2010, 40, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habes, D.J.; Baron, S. Ergonomic evaluation of antenatal ultrasound testing procedures. Appl Occup Environ Hyg. 2000, 15, 521–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesen, M.N.; Friesen, R.; Quanbury, A.; Arpin, S. Musculoskeletal injuries among ultrasound sonographers in rural Manitoba: a study of workplace ergonomics. AAOHN J 2006, 54, 32–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Village, J.; Trask, C. Ergonomic analysis of postural and muscular loads to diagnostic sonographers. Int J Ind Ergon 2007, 37, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschoarelli, L.; Oliveira, A.B.; Coury, H. Assessment of the ergonomic design of diagnostic ultrasound transducers through wrist movements and subjective evaluation. Int J Ind Ergon 2008, 38, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAtamney, L.; Nigel Corlett, E. RULA: a survey method for the investigation of work-related upper limb disorders. Appl Ergon 1993, 24, 91–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hignett, S.; McAtamney, L. Rapid entire body assessment (REBA). Appl Ergon 2000, 31, 201–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karhu, O.; Kansi, P.; Kuorinka, I. Correcting working postures in industry: A practical method for analysis. Appl Ergon 1977, 8, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, R.R.; Lu, M.L.; Occhipinti, E.; Jaeger, M. Understanding outcome metrics of the revised NIOSH lifting equation. Appl Ergon 2019, 81, 102897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kee, D. Systematic Comparison of OWAS, RULA, and REBA Based on a Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piętakiewicz, W.; Sykała, A.; Trybuszkiewicz, P.; Trepiak, R.; Szczyrba, K.; Roszak, M.; Michnik, R.; Molenda, M.; Miller-Banaś, A. (2024). Application of the NORAXON myoMotion system in the scope of 5S methodology applications. In: TalentDetector2024_Winter: International Students Scientific Conference, 26th 24. Bonek, W.M., Ed.; Publisher: Department of Engineering Materials and Biomaterials, Silesian University of Technology, Zabrze, Poland, pp. 386–395. 20 January.

- Central Institute for Labour Protection, National Research Institute. https://www.ciop.pl/CIOPPortalWAR/appmanager/ciop/pl?_nfpb=true&_pageLabel=P620059861340178661073&html_tresc_root_id=300012898&html_tresc_id=300012923&html_klucz=32274 (accessed on 1.06.2025). (accessed on 1.06.2025).

- Ergo Plus. https://ergo-plus.com/wp-content/uploads/rapid-upper-limb-assessment-rula-1.png?x51169 (accessed on 1.06.2025). (accessed on 1.06.2025).

- Ergo Plus. https://ergo-plus.com/wp-content/uploads/rapid-entire-body-assessment-reba-1.png?x51169 (accessed on 1.06.2025). (accessed on 1.06.2025).

- Silverstein, B.A. (1985). The prevalence of upper extremity cumulative trauma disorders in industry. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan 1985, University Microfilms International.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).