1. Introduction

Male ejaculatory disorders, predominantly characterized by either premature ejaculation (PE) or anejaculation (AE), represent prevalent and clinically significant subtypes of sexual dysfunction worldwide. PE is defined as ejaculation occurring rapidly, with minimal sexual stimulation and typically associated with distress or interpersonal difficulties, affecting up to 20–30% of men globally [

1]. In contrast, AE, a comparatively less prevalent but often more debilitating condition, involves the persistent or recurrent inability to ejaculate despite adequate sexual stimulation, leading not only to significant distress but also considerable impairment in fertility and quality of life [

2]. Accurate clinical differentiation between AE and PE is essential, as their underlying pathophysiology and optimal therapeutic approaches differ markedly. However, in clinical practice, these distinct conditions are frequently misdiagnosed or inadequately distinguished, resulting in inappropriate or ineffective treatments. Understanding the precise neurophysiological and clinical mechanisms underlying these ejaculatory disorders thus represents a critical unmet need in sexual medicine, with implications for improving diagnostic clarity and guiding targeted clinical interventions.

Vibration perception threshold (VPT) testing is frequently employed in clinical practice as an objective measure to evaluate peripheral sensory function in patients presenting with ejaculatory dysfunction [

3]. By quantifying the minimal vibration intensity perceived at specific anatomical points, VPT theoretically assesses the integrity of somatosensory pathways critical to sexual reflexes, including those involved in ejaculation. Consequently, VPT has been proposed as a potential diagnostic or adjunctive tool to differentiate ejaculatory disorder subtypes, particularly between peripheral sensory impairment and centrally mediated dysfunction [

4]. However, despite its widespread clinical use, the actual discriminative utility of VPT testing between AE and PE has never been rigorously validated. In daily clinical scenarios, VPT values for AE and PE patients often appear remarkably similar, raising substantial doubts about its effectiveness and clinical relevance in subtype differentiation [

5]. Furthermore, the underlying assumption that peripheral sensory function significantly differs between AE and PE has rarely been explicitly challenged or empirically tested. Thus, reliance on VPT testing without clear supportive evidence risks oversimplifying complex disorders and potentially overlooking critical central, inflammatory, or psychological mechanisms. Given these unresolved issues, there is an urgent need for systematic evaluation to determine the true diagnostic value of VPT testing in distinguishing AE from PE, and if insufficient, to identify alternative clinical parameters that reliably differentiate these conditions [

6]. Addressing this gap is essential not only to refine diagnostic accuracy but also to enhance targeted therapeutic interventions, ultimately improving patient outcomes in sexual medicine.

To address these objectives, we conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study involving 103 male patients clinically diagnosed with either AE or PE. We systematically analyzed comprehensive clinical data, including VPT measurements at ten distinct anatomical sites, spinal MRI evaluations (cervical and lumbar), chronic prostatitis status determined by expressed prostatic secretion microscopy and ultrasound findings, psychological assessments using standardized scales for depressive and anxiety symptoms, sexual desire score. Rigorous statistical methods, including correction for multiple comparisons and Firth-penalized logistic regression modeling, were employed to ensure robust identification of factors independently associated with AE.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

We conducted a single-center, retrospective, cross-sectional study at the Department of Andrology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University.between January 2025 and April 2025. Participants included consecutive male patients clinically diagnosed with either anejaculation (AE) or premature ejaculation (PE) at our specialized andrology outpatient clinic. AE was defined as the persistent or recurrent inability to achieve ejaculation despite adequate sexual stimulation, causing distress or functional impairment [

7]. PE was defined according to the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) criteria as ejaculation occurring within approximately one minute following vaginal penetration (lifelong PE) or a clinically significant reduction in ejaculation latency (acquired PE), accompanied by significant personal distress or interpersonal difficulty [

6].

Patients were excluded if they had known neurologic diseases affecting sensory or motor function (e.g., multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury), significant anatomical or structural abnormalities of the genitourinary system (e.g., prior pelvic or spinal surgery, penile deformities), or severe psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder). Additionally, individuals taking medications known to significantly influence ejaculatory function, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, or alpha-blockers, were excluded from analysis.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, and patient data were anonymized prior to analysis, waiving the requirement for written informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study.

2.2. Data Collection and Clinical Assessments

Clinical data were systematically collected from patient medical records, including detailed vibration perception threshold (VPT) test results, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, chronic prostatitis evaluations, and validated psychological assessments.VPT testing was performed using a standardized vibrotactile sensory analyzer (Bio-Thesiometer, Bio-Medical Instrument Co., Newbury, OH, USA), at ten distinct anatomical locations: the glans penis (at 12, 3, 6, and 9 o’clock positions), the penile root (at 12, 3, 6, and 9 o’clock positions), and bilateral index fingertips. Patients were tested in a quiet, controlled room, and the lowest detectable vibration intensity at each location was recorded. MRI scans were acquired using a SIGNA™ Premier 3.0 Tesla wide-bore MRI system (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA), equipped with SuperG 80/200 gradient coils, 146-channel radiofrequency reception, and a 70 cm bore diameter. Lumbar spinal abnormalities were evaluated at vertebral levels T12–L2, and cervical spinal abnormalities at C3–C8, including intervertebral disc protrusion, spinal stenosis, or nerve root compression [

8]. Findings were independently assessed and confirmed by two senior radiologists blinded to clinical diagnoses.Chronic prostatitis status was determined based on microscopic analysis of expressed prostatic secretions (EPS), with chronic prostatitis defined as ≥10 leukocytes per high-power microscopic field (×400), and corroborated by characteristic ultrasound imaging findings (e.g., heterogeneous echotexture, increased vascularity, or calcifications) [

9].Psychological assessments were conducted using validated scales, including the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression symptoms, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) for anxiety, and Sexual Desire Inventory–2 (SDI-2) [

10]. All scales were administered using validated Chinese-language versions by trained clinical staff, following standardized scoring protocols.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted systematically in two stages. First, differences in vibration perception threshold (VPT) measurements between AE and PE patients at each anatomical site were assessed individually using Mann–Whitney U tests. To account for multiple comparisons across the ten anatomical test locations, p-values were corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) method. Differences in other clinical and imaging parameters—including spinal MRI abnormalities (lumbar and cervical segments), presence of chronic prostatitis, psychological assessment scores (PHQ-9 and GAD-7), and sexual desire scores (SDI-2)—were evaluated between AE and PE groups. Continuous variables were compared using Mann–Whitney U tests due to their non-normal distribution, while categorical variables were analyzed by Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate.

In the second stage, variables demonstrating statistical significance (p < 0.05) in univariate analyses or identified as clinically relevant based on established biological plausibility were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model to identify factors independently differentiating AE from PE. Considering the limited number of AE cases (n = 21) and the resulting low event-per-variable ratio (EPV ≈ 5), we explicitly adopted Firth’s penalized logistic regression to minimize the risks of estimation bias and model instability inherent to traditional logistic regression approaches under small-sample conditions. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. Model performance was evaluated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and discrimination was quantified by the area under the ROC curve (AUC).Sensitivity analyses were additionally performed to evaluate the robustness and consistency of the main findings.

All statistical tests were two-sided, and statistical significance was set at a p-value < 0.05. Analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The “logistf” package was used to perform the Firth penalized logistic regression analysis, and the “pROC” package was utilized for ROC curve analyses.

3. Results

3.1. VPT Does Not Distinguish AE from PE

To investigate the potential of vibration perception threshold (VPT) assessments in distinguishing patients with anejaculation (AE) from those with premature ejaculation (PE), we first compared VPT measurements acquired from ten anatomically standardized test sites, as defined by the manufacturer’s protocol and consistent with routine clinical practice. The AE group consisted of 21 patients, while the PE group included 82 patients. All patients underwent standardized quantitative sensory testing. VPT values were recorded at ten anatomically standardized sites: the glans penis (at 12, 3, 6, and 9 o’clock), the penile root (at 12, 3, 6, and 9 o’clock), and the index fingertips of both hands, in accordance with established protocols. Additionally, a composite VPT mean across all ten sites was calculated for each patient.

As summarized in

Table 1, VPT measurements showed no statistically significant differences between AE and PE patients at any anatomical site after applying the false discovery rate (FDR) correction. At the glans 12 o’clock position, the AE group exhibited a slightly lower median VPT [5.00 (IQR 3.00–6.90)] than the PE group [6.20 (IQR 4.38–7.95)], yet this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.04; FDR-adjusted q = 0.20). Comparable patterns were observed at other glans sites, including the 3 o’clock (AE: 5.50 vs PE: 6.60, q = 0.33), 6 o’clock (AE: 6.00 vs PE: 7.65, q = 0.22), and 9 o’clock (AE: 4.40 vs PE: 6.80, q = 0.20) positions.

Penile root measurements achieved slightly elevated VPT values in both AE and PE patients, but followed a similar trend in differences between AE and PE patient (all q > 0.05). For example, at the root 9 o’clock position, the AE group had a median VPT of 5.80 (IQR (3.60–6.70)), compared to 6.10 (IQR 4.22–7.30) in the PE group (p = 0.36; q = 0.58). No between-group differences were detected at fingertip sites, either. The median VPT at the right index finger was 4.30 (IQR 3.90–4.90) in AE patients and 4.85 (IQR 3.82–6.85) in PE patients (p = 0.10; q = 0.21), underscoring the absence of systemic sensory impairment in both cohorts. The average VPT across all 10 test sites was also not significantly different between AE and PE groups (AE: 6.18 vs PE: 5.98, q = 0.27).

Taken together, these findings provide no evidence that VPT testing can discriminate between AE and PE. Despite localized trends suggesting mildly elevated thresholds in AE patients, none reached statistical significance after multiple testing correction. Thus, peripheral sensory dysfunction, as assessed by VPT, is unlikely to serve as a distinguishing factor between the two ejaculatory dysfunction phenotypes.

3.2. Beyond Sensory Testing: Spinal and Prostatic Factors Associated with Anejaculation

Given the lack of discriminatory value observed in vibration perception thresholds (VPTs) between patients with anejaculation (AE) and those with premature ejaculation (PE), we extended our investigation to structural, inflammatory, and psychological domains that may underlie ejaculatory dysfunction. Specifically, we focused on spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) abnormalities, clinical evidence of chronic prostatitis, and validated psychological assessment scores.

3.2.1. Spinal MRI Abnormalities

Ejaculation is a complex neuromuscular event coordinated by supraspinal centers and integrated at the spinal cord level, particularly within lumbar and cervical segments [

11]. Structural pathologies affecting these regions—such as intervertebral disc protrusions, spinal canal narrowing, and vertebral degeneration—may interfere with the ejaculatory reflex arc or alter afferent/efferent neural transmission.

Given the possible role of cervical and lumbar spinal segments in coordinating ejaculatory reflexes, we selectively included MRI scans of these two regions. Imaging data from other spinal segments were not acquired. Radiological reports were systematically reviewed, and the presence or absence of clinically relevant structural abnormalities in the cervical or lumbar spine—such as disc herniation, spinal canal narrowing, or vertebral degeneration—was recorded. For the purposes of this analysis, we focused solely on a binary classification (abnormal vs. normal) within each segment, without further subclassifying the specific pathology types.

Lumbar spinal abnormalities were observed in 12 of 21 patients with anejaculation (57.1%) and 21 of 82 patients with premature ejaculation (25.6%), demonstrating a statistically significant difference (Chi-square test, p = 0.01;

Table 2). In contrast, cervical spinal abnormalities were present in only 2 AE patients (9.5%) versus 21 PE patients (25.6%), a difference that did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.20). These findings highlight a disproportionate association between lumbar structural pathology and anejaculation. While cervical involvement appears less relevant, the possibility of cumulative effects from multilevel spinal degeneration warrants further investigation.

3.2.2. Prostatic Inflammation

The prostate plays a pivotal role in the emission phase of ejaculation by coordinating autonomic outflow to the seminal vesicles, vas deferens, and bladder neck. Disruption of this intricate process—especially via chronic inflammation—has been hypothesized to impair both the sensory signaling and contractile mechanics required for effective ejaculation [

12]. To evaluate the presence of chronic prostatitis in our cohort, we applied a dual-criterion definition: (1) expressed prostatic secretion (EPS) with leukocyte ≥10 per high-power microscopic field (×400), and/or (2) abnormal seminal vesicle ultrasound findings suggestive of inflammation or obstruction (e.g., dilatation, wall thickening, echogenic inhomogeneity) [

9].

Based on these criteria, chronic prostatitis was diagnosed in 11 of 21 patients with anejaculation (52.4%) and 18 of 82 patients with premature ejaculation (22.0%), yielding a significant between-group difference (Chi-square test, p = 0.01;

Table 3). These findings support a possible mechanistic link between chronic pelvic inflammation and ejaculatory dysfunction, particularly in AE. From a pathophysiological perspective, persistent prostatic and seminal vesicle inflammation may impair smooth muscle contractility, disrupt neuroendocrine regulation, and generate nociceptive feedback that interferes with the ejaculatory reflex arc.

Importantly, this inflammatory burden may be clinically silent, as most AE patients did not report overt perineal pain or voiding symptoms [

13]. This underscores the relevance of objective EPS and imaging evaluation in identifying subclinical prostatitis that may otherwise be overlooked in routine assessments. These findings align with prior hypotheses that ejaculatory dysfunction may be a sentinel symptom of underlying chronic prostatitis, particularly in patients without classical pelvic pain syndromes.

3.2.3. Psychological Distress

Ejaculation is not purely a neurophysiological event, it is deeply modulated by cognitive, emotional, and psychosocial factors. Depression and anxiety, in particular, have been shown to alter hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis signaling, disrupt sympathetic tone, and impair central sexual motivation [

14]. To assess the psychological burden in our cohort, we employed two widely validated tools: the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale for anxiety symptoms. We also evaluated libido function using the Sexual Desire Inventory–2 (SDI-2) questionnaire.

Patients diagnosed with anejaculation (AE) exhibited a markedly greater burden of depressive symptoms compared to those with premature ejaculation (PE). Specifically, the median PHQ-9 score in the AE group was 10.00 (IQR: 6.00–17.00), whereas patients in the PE group had a median score of 6.50 (IQR: 2.25–10.00), with this difference reaching statistical significance (p = 0.01). Notably, the proportion of individuals meeting the threshold for moderate-to-severe depression (PHQ-9 ≥10) was substantially higher in the AE group, with 57.1% (12 of 21) of patients affected, compared to only 26.8% (22 of 82) in the PE group. This between-group disparity was statistically significant (χ2 = 5.65, p = 0.02), reinforcing the hypothesis that depressive symptomatology is both more prevalent and more severe in men with impaired ejaculation.

Although anxiety levels, as assessed by the GAD-7 scale, appeared higher in the AE cohort (median 7.00, IQR: 4.00–10.00) compared to the PE group (median 4.00, IQR: 1.00–7.00), the difference narrowly missed statistical significance (p = 0.05), suggesting a potential—but not definitive—role of anxiety in AE pathophysiology. Importantly, no significant difference was observed in libido between the groups, as measured by the SDI-2 (AE: median 39.00; PE: 38.00; p = 0.87), indicating that central sexual drive remained largely intact regardless of ejaculatory subtype.

Taken together, these findings position depressive symptoms as a prominent and potentially modifiable correlate of AE, distinct from generalized anxiety or reduced sexual desire. This distinction holds clinical value, as targeted psychological intervention—especially addressing depressive cognition—may yield therapeutic benefit in selected AE patients.

Table 4.

Comparison of Psychological Distress Scores Between AE and PE Patients.

Table 4.

Comparison of Psychological Distress Scores Between AE and PE Patients.

| Scale |

Group |

Mean ± SD |

Median (IQR) |

p-value |

| PHQ-9 (Depression Score) |

AE |

10.24 ± 5.72 |

10.00 (6.00–17.00) |

0.01 |

| PE |

6.24 ± 4.94 |

6.50 (2.25–10.00) |

| GAD-7 (Anxiety Score) |

AE |

6.95 ± 4.80 |

7.00 (4.00–10.00) |

0.05 |

| PE |

4.33 ± 3.83 |

4.00 (1.00–7.00) |

| SDI-2 (Sexual Desire Score) |

AE |

38.67 ± 17.86 |

39.00 (30.00–49.00) |

0.87 |

| PE |

38.21 ± 18.64 |

38.00 (25.00–50.00) |

3.3. Multivariable Analysis of Independent Factors Differentiating AE from PE

To identify independent factors that differentiate anejaculation (AE) from premature ejaculation (PE), we conducted a multivariable Firth penalized logistic regression analysis. This method was specifically selected due to the limited sample size and relatively low event-per-variable ratio (AE events: 21) to ensure stable and unbiased estimation. Candidate variables were chosen based on univariate statistical significance and biological plausibility: lumbar MRI abnormalities, chronic prostatitis diagnosis, depressive symptom severity (PHQ-9 scores), and mean vibration perception threshold (VPT_mean), despite the latter not achieving statistical significance individually, due to its potential clinical relevance as a marker of peripheral nerve function.

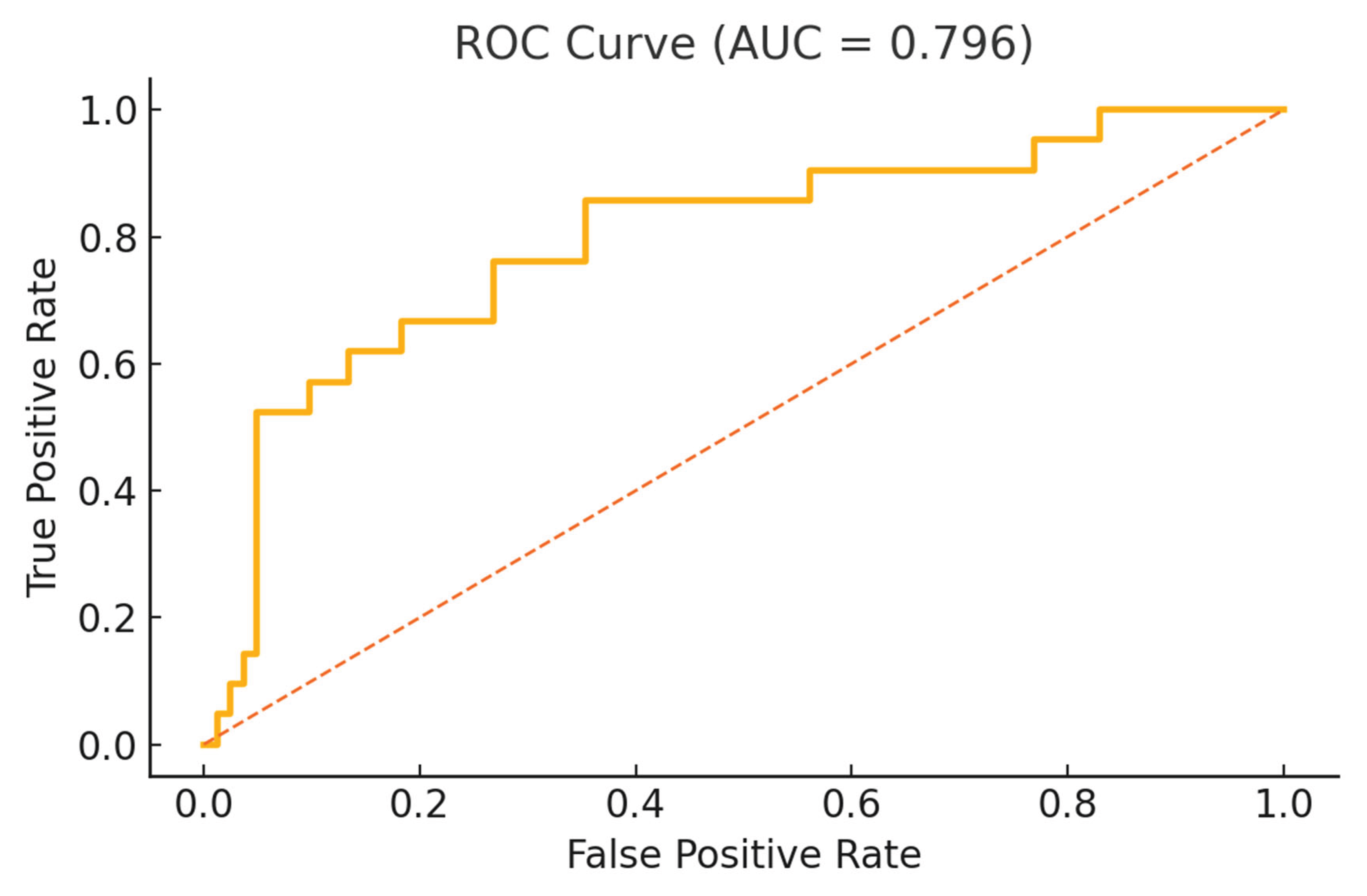

The model included a total of 103 patients (AE: 21, PE: 82) and demonstrated good discriminative capability, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC-AUC) of 0.796 (

Figure 1), suggesting that these selected variables collectively provided a robust differentiation between AE and PE.

The ROC curve evaluates the discriminatory ability of the multivariable Firth-penalized logistic regression model, which included lumbar MRI abnormalities, depressive symptoms, mean vibration perception threshold (VPT), and chronic prostatitis status as covariates. The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.796, indicating good overall model performance in distinguishing patients with anejaculation from those with premature ejaculation.

In the adjusted analysis (

Table 5), lumbar MRI abnormalities remained significantly associated with AE, with an adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 5.73 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.14–28.83, p = 0.04). Depressive symptom severity, measured by PHQ-9, was independently associated with AE, indicating a 4.6% increased odds for AE with each one-point increment in PHQ-9 score (OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.00–1.09, p = 0.04). Mean VPT demonstrated a significant inverse relationship, with each unit increase associated with a 3.1% decrease in the odds of AE (OR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.94–1.00, p = 0.03). Notably, chronic prostatitis, though significant in univariate analysis, did not independently differentiate AE from PE in this adjusted model (OR = 3.35, 95% CI: 0.63–17.90, p = 0.17).

Sensitivity analyses, including the binary categorization of VPT based on median split and exclusion of chronic prostatitis, consistently supported the primary findings. These analyses confirmed that the directions and significance of associations for lumbar MRI abnormalities, depressive symptoms, and VPT_mean were robust across alternative modeling strategies, with ROC-AUC ranging from 0.746 to 0.832.

These findings highlight lumbar MRI abnormalities, depressive symptom severity, and peripheral nerve integrity as independent and clinically relevant factors that differentiate AE from PE, suggesting the importance of multidisciplinary evaluation—including spinal imaging, psychological screening, and sensory nerve function testing—in patients presenting with ejaculatory dysfunction. Chronic prostatitis, by contrast, did not maintain significance after adjustment, indicating it may not represent a primary distinguishing factor between AE and PE.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study challenge traditional clinical and neurophysiological perspectives on anejaculation (AE). Historically regarded either as predominantly psychogenic or as a consequence of advanced neurologic pathology [

15], AE appears more accurately conceptualized as a syndrome involving impaired neuro-integration. Our data suggest that AE arises from disruptions in spinal neural pathways, potentially modulated by depressive symptoms and subtle alterations in peripheral sensory processing, rather than from isolated structural, inflammatory, or psychological factors alone.

Anejaculation is inherently rare—estimates place its prevalence well below 1% of men presenting with sexual dysfunction—so accruing larger cohorts within a single centre proved infeasible despite systematic case identification [

2]. Our AE sample of 21 truly mirrors real-world clinical practice, where most urology or andrology clinics encounter only a handful of new AE cases annually [

5]. Importantly, a smaller, well-characterized cohort can yield more precise insights than a larger, heterogeneous one. To bolster confidence in our findings despite the modest AE sample, we (1) restricted our multivariable model to four predictors in line with EPV recommendations, (2) applied Firth’s penalization to guard against small-sample estimation bias and separation, (3) performed sensitivity analyses—including alternate VPT coding and exclusion of prostatitis—that preserved effect sizes and direction, and (4) demonstrated good model discrimination (AUC = 0.80). Taken together, these design elements and analytic safeguards ensure that our conclusions remain robust and generalizable, even within the possible constraints imposed by AE’s low prevalence.

The absence of statistically significant differences in vibration perception threshold (VPT) at individual anatomical sites between AE and PE patients, even after false discovery rate (FDR) correction, initially suggests limited peripheral sensory impairment. However, the observed significant inverse association between the mean composite VPT and AE in the adjusted multivariable model provides evidence that subtle but cumulative differences in peripheral sensory integrity may still contribute to ejaculatory dysfunction. Single-site VPT measurements likely lack sufficient sensitivity to capture these subtle differences [

16], while the composite mean more robustly reflects the aggregate peripheral sensory input to central ejaculatory networks. Hence, although gross peripheral neuropathy is unlikely, mild impairment or variations in peripheral sensory integration may still hold clinical relevance.

Our observation of a significant association between AE and structural lumbar spinal abnormalities further strengthens the hypothesis of spinal involvement. Many of the lumbar MRI findings in AE patients—such as mild disc protrusions or subtle spinal canal narrowing—were modest and typically would not prompt neurological concern. However, the anatomical localization of these subtle abnormalities corresponds closely to the known spinal ejaculation generator (SEG), a multi-segmental network integrating autonomic, somatic, and descending supraspinal inputs crucial for ejaculatory function [

17]. The clinical significance of these seemingly minor structural disruptions is thus heightened in AE, suggesting that even minimal anatomical changes at critical spinal segments can meaningfully impact the complex coordination required for ejaculation. While cervical spinal involvement was less prominent statistically, the potential contributory role of cervical segments via descending autonomic modulation remains plausible and warrants future investigation.

Chronic prostatitis was significantly more common among AE patients in univariate analysis; however, its independent significance was not maintained after adjusting for lumbar MRI abnormalities, depressive symptoms, and peripheral sensory function. Thus, while chronic inflammation of the prostate and seminal vesicles has known potential to alter sensory and autonomic tone through neuro-inflammatory mechanisms [

18], our results indicate that its role in AE may primarily be modulatory rather than independently causative. Clinically, the frequent absence of overt pelvic pain or voiding symptoms among AE patients highlights the subtlety and complexity of prostate-related inflammation. The potential interaction between chronic prostatic inflammation and structural or psychological vulnerabilities deserves continued attention, although it may not represent a primary distinguishing factor between AE and PE.

Depressive symptoms, as measured by the PHQ-9 score, emerged as a significant differentiating factor between AE and PE patients, independently maintaining significance after multivariable adjustment. Each incremental increase in depressive symptoms conferred an approximately 5% greater odds of AE relative to PE. The precise pathophysiological mechanisms linking depression and AE likely involve diminished dopaminergic drive, enhanced central inhibition, and impaired hypothalamic–spinal signaling [

19,

20,

21]. Depression’s ability to suppress central activation of sexual reflexes might exacerbate vulnerabilities introduced by structural spinal changes or subtle sensory integration deficits [

22]. Importantly, neither anxiety nor libido levels were independently associated with AE, emphasizing depression’s unique contribution within the psychosocial dimension.

Together, these results support a revised neurofunctional model of AE, distinct from the conventional “reflex failure” paradigm associated with overt neurologic disease or the “performance anxiety” model traditionally attributed to PE [

23]. AE in this framework is not a single-domain dysfunction but rather a disorder characterized by converging disruptions in spinal neural integrity, depressive modulation, and subtle impairments in peripheral sensory input. Chronic prostatitis may further modulate this framework, particularly in patients with underlying structural or psychological susceptibilities, though it does not independently differentiate AE from PE.

Clinically, these insights have immediate implications. Firstly, clinicians evaluating AE should maintain a higher index of suspicion for subtle structural spinal abnormalities. Mild lumbar pathology, previously dismissed as clinically irrelevant [

24], may warrant early MRI investigation in patients with AE, especially if accompanied by depressive symptoms. While routine spinal imaging is not universally indicated, targeted lumbar and potentially cervical MRI should be considered earlier in the diagnostic algorithm when AE cannot be clearly attributed to psychological or peripheral causes.Secondly, subclinical inflammation should retain a position in the diagnostic evaluation of ejaculatory disorders, though it should be interpreted cautiously. While our results do not support chronic prostatitis as an independent primary factor, the frequent presence of subtle inflammation may still represent an important modulatory influence within a vulnerable neurosexual system [

25]. Clinically silent prostatitis, detectable through expressed prostatic secretion (EPS) microscopy or seminal vesicle ultrasound, may offer actionable therapeutic targets, particularly in combination with structural or psychological interventions.Thirdly, depressive symptoms should not be regarded solely as psychological reactions to sexual dysfunction, but as active modulators of the neurophysiological processes governing ejaculation. Even subclinical depressive symptoms can alter central inhibitory control of sexual reflexes and impair effective spinal and hypothalamic signaling [

22,

26]. Recognizing and addressing depressive symptoms through early psychiatric evaluation and intervention, potentially alongside neuromodulatory therapies, may significantly enhance clinical outcomes in AE management.

Looking ahead, several research directions warrant prioritization. Prospective studies employing advanced spinal imaging techniques, such as diffusion tensor imaging or spinal functional MRI, are necessary to further delineate the structural abnormalities most closely linked to ejaculatory dysfunction [

17,

27]. Longitudinal monitoring of depressive symptoms in AE patients may better define psychological factors’ temporal relationship with symptom onset and progression. Additionally, future trials should systematically evaluate combination therapies—such as targeted spinal interventions, anti-inflammatory treatment in specific subpopulations, and psychiatric co-management—to establish effective evidence-based management strategies for AE [

2,

13].

To summary, we advocate a shift towards a more integrative and nuanced understanding of AE, which emerges not as the endpoint of isolated pathology, but rather as the clinical manifestation of interacting vulnerabilities within a complex neural network. Adopting this perspective may significantly improve diagnostic accuracy, therapeutic targeting, and ultimately, patient outcomes in this challenging ejaculatory disorder.