Submitted:

03 September 2025

Posted:

05 September 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Two major paracellular pathways, leak and pore, can transport metabolites from the lumen into the extra-luminal space.

- The location of the open pathway along the gut (duodenum/jejunum, ileum, proximal colon, distal colon) determines which metabolites are available to be pathologically exported.

- The combination of pathway type and location shapes the resulting patient phenotype.

- Review the current literature and how our model is aligned with it.

- Discuss the salient aspects of paracellular pathways.

- Describe how we performed the mapping from symptoms to pathways and locations.

- Summarize our results.

2. Literature Review

- Anti-inflammatories: Limited benefits

- Narrow probiotics and short term trials: Mixed results

- Broad spectrum probiotics and long term trials: More promising

“Nevertheless, the emerging strategy of combining multi-strain probiotics with other functional ingredients previously implicated with anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative properties (e.g., polyphenols, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, l-carnitine, and coenzyme Q10) is a promising approach that may offer significant advantages for not only reducing fatigue but also increasing the well-being of patients with post-viral syndromes.” [2]

3. Paracellular Pathways

3.1. Locations

3.2. Characteristics

- The size range of molecules transported

- Charge selectivity (cations, anions, or both)

- Whether they can be activated independently of overt inflammation

- Mechanisms of closure or deactivation

- Anion-selective pores favor lactate and other organic acids.

- Cation-selective pores favor histamine and polyamines.

- Leak pathway is less selective, admitting medium to large molecules during periods of inflammation or cytoskeletal stress [7].

| Pathway | Size Range | Activation | Closure/Deactivation |

| Leak | Up to a few kDa | Inflammatory / cytoskeletal stress | Requires resolution of inflammation / cytoskeletal reset |

| Anion Pore | Small molecules (< 6–8 Å) | Claudin isoform–specific signals | Rapid closure via tight junction proteins |

| Cation Pore | Small molecules (< 6–8 Å) | Claudin isoform–specific signals | Rapid closure via tight junction proteins |

3.3. Pathway Interventions

3.4. Mucosal Membrane

3.5. Established vs. Emerging Disorders

Intestinal barrier dysfunction has been associated with various diseases, from autoimmune (inflammatory bowel diseases [IBDs], type 1 diabetes mellitus, celiac disease, multiple sclerosis, etc.) to neurological ones (mood disorders, autism spectrum disorders, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease), playing the role of a primer or aggravating factor in their evolution. Camilleri (2021). [8]

4. Symptom Path Mapping

- Most ME/CFS symptoms directly arise from gut-derived metabolites entering the extra-luminal space.

- Histamine-related symptoms reflect cation-selective pore activity.

- Leak pathways enable only limited movement of ionic compounds compared to pores.

- Pore channels permit high-conductance flux at a rate proportional to their population in the lumen.

- Distal-colon permeability requires breakdown of the protective mucosal layer.

4.1. Expectations

- Linking the location, metabolites and paths

- Linking the location, symptoms and paths

| Location | Leak metabolites (larger/relatively uncharged) | Pore metabolites (small, charged) |

|---|---|---|

| Duodenum/Jejunum | Dietary/microbial peptides; endotoxin fragments (LPS pieces); acetaldehyde | D-lactate−; histamine+; ammonium+; small bile-acid anions |

| Ileum | Microbial peptides; antigenic fragments; partially deconjugated bile acids (neutral fraction) | Bile-acid anions; tryptamine/serotonin-pathway small ions/amines |

| Proximal Colon | Microbial peptides; endotoxin fragments; larger fermentation products (neutral phenolics) | SCFA anions (acetate−, propionate−, succinate−); D-lactate-;histamine+ |

| Distal Colon* | Neutral aromatic phenolics (e.g., p-cresol); indole/phenyl derivatives; endotoxin fragments | Indoxyl sulfate−; p-cresyl sulfate−; thiosulfate− |

| Location | Leak Symptoms | Pore Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Duodenum/Jejunum | GI distress, alcohol/smell intolerance, post-prandial fatigue | Acute dizziness, anxiety, dysautonomia, rapid brain fog from D-lactate/histamine |

| Ileum | Bile acid diarrhea, abdominal pain, immune flares | Sleep rhythm disturbance, mood instability (bile acids, tryptamine spill) |

| Proximal Colon | Systemic malaise, low-grade inflammation, diffuse fatigue | Heaviness, orthostatic intolerance (succinate, SCFAs) |

| Distal Colon* | Toxic-feeling flares, chemical/odor sensitivity, inflammatory hits | Severe brain fog, vascular headaches, pruritus, dizziness, nausea (indoxyl sulfate, p-cresyl sulfate, sulfide) |

4.2. Gaseous Metabolites

- H2S is generated in the distal colon by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Normally detoxified by colonocytes, it becomes clinically relevant when the distal mucus layer is disrupted, producing headache, dizziness, and nausea.

- Ammonia is produced by urea-splitting bacteria throughout the gut. In equilibrium, the uncharged NH3 fraction can diffuse across membranes, while the NH4+ fraction requires pore-mediated transport. Excess systemic exposure is associated with confusion, fatigue, and mood disturbance.

| Gas | Source organisms/location | Transport route | Symptom associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2S | Sulfate-reducing bacteria (e.g., Desulfovibrio) in distal colon | Passive diffusion across membranes (conditional on mucus loss) | Headache, dizziness, nausea, “toxic” flare sensations |

| NH3 / NH4+ | Urease-positive bacteria (e.g., Proteus, Klebsiella, E. coli) throughout gut | NH3 diffuses freely; NH4+ requires pores | Confusion, mood lability, irritability, fatigue |

4.3. Symptom Evidence Summary

| Metabolite | Key Symptoms Associated | Evidence Level | Notes (Human Disease Context) |

| Acetaldehyde | Cognitive fog, headache, dizziness, GI discomfort | Mechanistic | Preclinical and case-level data (yeast, alcohol intolerance); no large cohort validation. |

| Ammonia / Ammonium (NH3) | Confusion, cognitive dysfunction, fatigue | Established | Robust evidence in hepatic encephalopathy and urea cycle disorders. |

| Bile acids | Diarrhea, urgency, circadian/mood disturbance | Established | Bile acid diarrhea, ileal resection, IBS-D. |

| D-lactate | Neurocognitive dysfunction, dizziness, fatigue, acidosis | Established | Documented in D-lactic acidosis and dysbiosis syndromes. |

| Histamine | Flushing, tachycardia, anxiety, pruritus, headaches | Established | Strong clinical links in MCAS, allergy, IBS, IBD. |

| Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) | Headache, nausea, sensory overload, visceral pain | Mechanistic | Strong toxicology/preclinical evidence; no direct human cohort validation. |

| Indoxyl sulfate | Fatigue, vascular dysfunction, neurocognitive effects | Established | Major uremic toxin in CKD; robust patient-level data. |

| LPS fragments / peptides | Inflammatory malaise, fever, gut permeability, fatigue | Established | Elevated in IBD, sepsis; systemic inflammation in patients. |

| Neutral phenolics (generic fermentation products) | Cognitive fog, gut irritation, behavioral effects | Mechanistic | Mostly preclinical; only p-cresol itself has strong human evidence. |

| p-Cresol | Cognitive fog, gut irritation, behavioral symptoms | Established | Elevated in autism and CKD patient cohorts. |

| p-Cresyl sulfate | Fatigue, vascular and CNS dysfunction | Established | Major uremic toxin in CKD; robust clinical evidence. |

| SCFAs (acetate, propionate, succinate) | Heaviness, fatigue, “crash” symptoms, inflammation | Established | Succinate (colitis), propionate (autism), acetate (systemic energy regulation). |

| Thiosulfate | Headache, nausea, sensory burden, GI pain | Mechanistic | Detected in humans as a sulfide metabolite marker, but weak symptom-level data. |

| Tryptamine / serotonin-pathway amines | Mood disturbance, circadian disruption, sleep issues | Mechanistic | Microbiome and preclinical links; human associations indirect, causality unproven. |

4.4. Mapping Procedure

- Data source: Symptom severity from Vaes (2023).

- Exclusion: Remove PEM and fatigue, as these are non-specific across clusters.

- Order of analysis: Leak → Pore → Gas → Anatomical location. Clusters may receive multiple assignments if multi-system burden is evident.

-

Pathway assignments:

- Leak (PCx): Inflammatory pain, malaise, pressure-type burdens.

-

Pore:

- −

- DJ: Alcohol/smell intolerance, dizziness, anxiety (histamine, D-lactate).

- −

- IL: Diarrhea, mood/circadian disturbance (bile acids, tryptamine).

- −

- PA (PC anion pore): SCFA/succinate features (heaviness, crash-like fatigue).

- −

- PC (PC cation pore): Orthostatic intolerance, autonomic dysfunction.

- Gas (DC): Sensory overload, vascular headache, chemical sensitivity, pruritus; requires severe GI burden and presumed mucus breakdown.

-

Strength levels:

- ++ = dominant or multiple relevant symptoms.

- + = moderate/secondary evidence.

- – = absent.

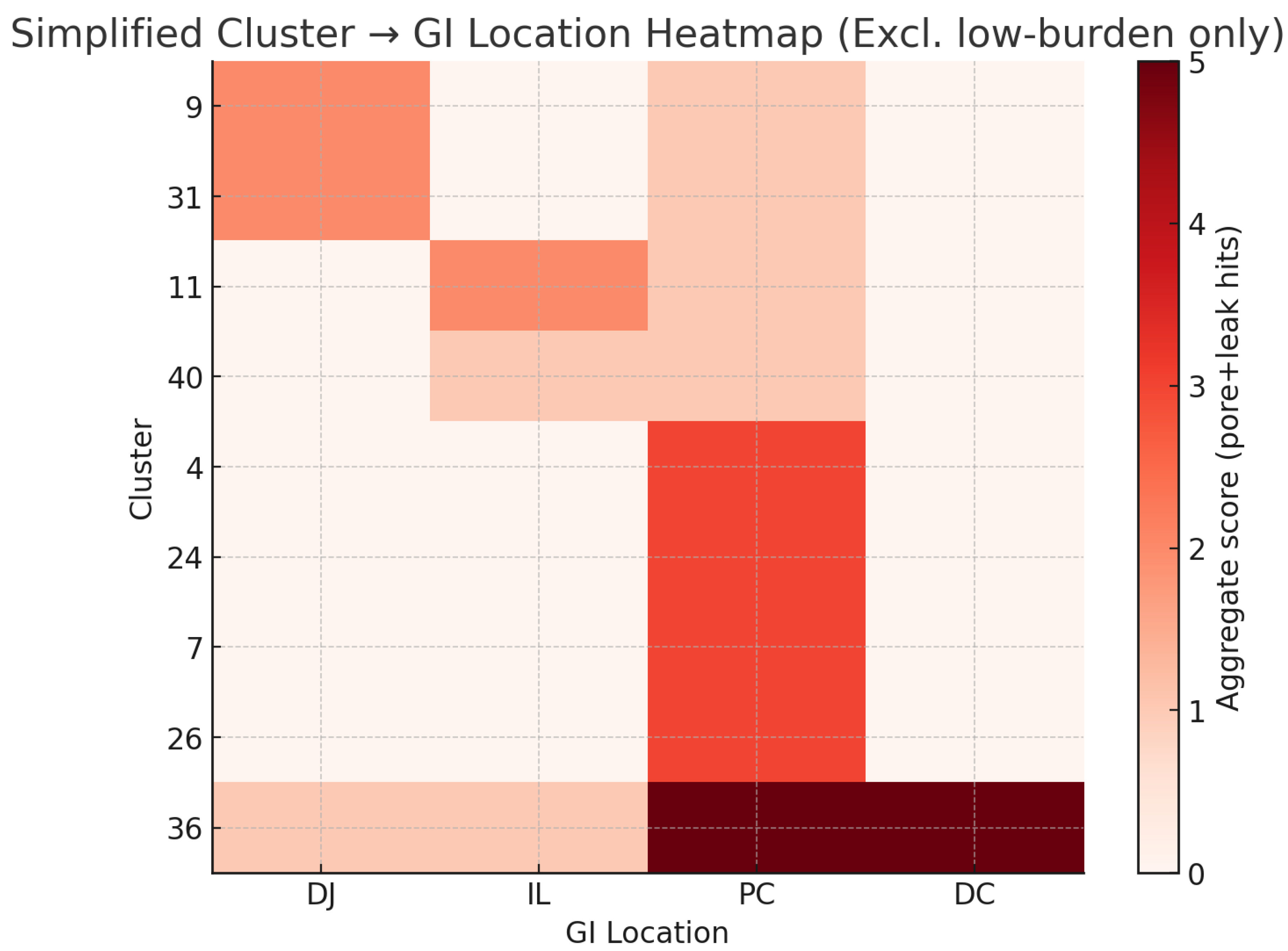

5. Results

5.1. Vaes Patient Cluster Mapping

| Vaes cluster (n) | DJ-pore (–) | DJ-leak | IL-pore (–) | IL-leak | PC-pore (–) | PC-pore (+) | PC-leak | DC-pore (–) | DC-leak | DC-gas | Rationale |

| 2 (24) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Low-burden profile; little to localize. |

| 4 (23) | – | – | – | – | ++ | – | + | – | – | – | Orthostatic HR → PC-pore (–); inflammatory “drag” → PC-leak. |

| 7 (30) | – | – | – | – | ++ | + | – | – | – | – | Cognition-dominant → PC-pore (–); minor autonomic hints → PC-pore (+). |

| 9 (26) | ++ | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | Alcohol/smell intolerance, dizziness → DJ-pore (–); minor PC-pore (–) plausible. |

| 11 (17) | – | – | ++ | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | Day–night/mood + loose stools → IL-pore (–); occasional PC-pore (–). |

| 19 (19) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Low symptom load; unassigned. |

| 24 (43) | – | – | – | – | ++ | – | + | – | – | – | Sound sensitivity/sleep + PEM → PC-pore (–); inflammatory fatigue hints → PC-leak. |

| 26 (18) | – | – | – | – | + | – | ++ | – | – | – | Temperature/pressure pain → PC-leak++; some autonomic → PC-pore (–). Distal-colon gas less likely without severe GI. |

| 28 (38) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Low, nonspecific. |

| 31 (15) | ++ | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | “Stomach/bowel” + mast-cellish sensitivities → DJ-pore (–); PC-pore (–) possible. |

| 36 (10) | + | – | + | – | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ | Highest burden: broad multi-pathway involvement; DJ/IL contributions; PC-pore (–/+) and PC-leak; DC-pore/leak present; DC-gas++ justified by severe burden/mucus loss. |

| 37 (18) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Lowest burden; unassigned. |

| 40 (20) | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | Diarrhea/sleep/mood → IL-pore (–); inflammatory drag → PC-leak. |

- DJ-pore (–): Duodenum/jejunum, anion-selective pore (histamine, D-lactate).

- DJ-leak: Duodenum/jejunum leak (larger peptides, acetaldehyde).

- IL-pore (–): Ileum, anion-selective pore (bile acids, tryptamine).

- IL-leak: Ileum leak (antigenic peptides, immune activation).

- PC-pore (–): Proximal colon, anion-selective pore (succinate, SCFAs).

- PC-pore (+): Proximal colon, cation-selective pore (histamine, polyamines).

- PC-leak: Proximal colon leak (inflammatory “drag,” pressure pain).

- DC-pore (–): Distal colon pore (aromatic phenolics, sulfates, conditional on mucus loss).

- DC-leak: Distal colon leak (endotoxin fragments, aromatic phenolics, mucus loss required).

- DC-gas: Distal colon gaseous metabolites (H2S, NH3), only when mucus integrity fails.

5.2. Vaes Clusters by GI Location

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

5.4. Result Summary

- Proximal colon signals ME/CFS even after exclusion of PEM and fatigue from the mapping process.

- Five clusters show evidence of multiple site involvement.

- Four clusters did not show clear evidence of multi-site involvement.

5.5. Proximal Colon

- Causative: The multiple metabolite flood and dysbiosis is exactly what is needed to explain ME/CFS.

- Coincidental: So many suspects with so many possible symptoms makes it impossible not to find clusters with similar signals.

- Accidental: The proximal colon signals could be an artifact of our mapping of symptoms to metabolites without stronger clinical evidence for each metabolite.

5.6. The Proximal Colon in Literature

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- Proximal colon dysfunction as the base layer.

- Regional dysfunction elsewhere in the gut explain additional symptoms.

- Distal colon involvement contingent on mucus breakdown, serving as a gating mechanism.

Appendix A. Metabolites, Symptoms and Paths

- Pathway feasibility — excluded molecules too large or otherwise implausible for passage via leak or pore routes.

- Gut origin plausibility — excluded metabolites lacking a credible microbial or dietary source in the gut.

- Phenotypic specificity — excluded metabolites whose symptom associations were redundant with better-documented candidates.

| Metabolite | Key Symptoms | Pathway |

| Acetaldehyde*1 | headache, flushing, nausea, brain fog | Leak |

| Bile acids (deconjugated)*2 | gastrointestinal problems, barrier dysfunction, abdominal pain, fatigue | Leak |

| Indoxyl sulfate*3 | fatigue, vascular dysfunction, pruritus, sleep problems | Leak |

| p-Cresol sulfate*4 | cognitive problems, fatigue, headache | Leak |

| Serotonin (5-HT)*5 | nausea, gastrointestinal problems, anxiety, headache, sleep problems | Leak |

| Norepinephrine*6 | tachycardia, anxiety, insomnia, gastrointestinal problems | Leak |

| Acetate**7 | fatigue, gastrointestinal problems | Pore-Anion |

| D-lactate | fatigue, brain fog, coordination problems, confusion, headache, nausea | Pore-Anion |

| Succinate**8 | fatigue, inflammation, brain fog, abdominal pain, GI problems | Pore-Anion |

| Formate**9 | headache, visual disturbances, dizziness, fatigue, confusion, nausea | Pore-Anion |

| Propionate**10 | fatigue, nausea, brain fog | Pore-Anion |

| Ammonium (NH4+) | brain fog, drowsiness, irritability, nausea, headache | Pore-Cation |

| Cadaverine**11 | nausea, gastrointestinal problems, dizziness, headache | Pore-Cation |

| Histamine | flushing, tachycardia, pruritus, GI problems, anxiety, sleep | Pore-Cation |

| Tyramine | migraine, blood pressure swings, palpitations, anxiety, insomnia | Pore-Cation |

| Putrescine**12 | GI problems, cognitive problems, headache, irritability | Pore-Cation |

Appendix B. CRP Strata in ME/CFS

Appendix C. Vaes Symptom Severity Data

| Symptomgroup | Symptoms | 2 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 19 | 24 | 26 | 28 | 31 | 36 | 37 | 40 |

| fatigue | Fatigue/Extreme tiredness | 2.79 | 3.13 | 3.20 | 2.85 | 2.94 | 2.53 | 2.95 | 3.28 | 2.50 | 2.73 | 3.50 | 2.39 | 2.8 |

| PEM | Dead, heavy feeling after starting exercise | 2.17 | 2.00 | 2.60 | 2.35 | 1.76 | 1.79 | 2.21 | 2.78 | 1.18 | 2.00 | 3.20 | 0.94 | 1.85 |

| PEM | Next-day soreness or fatigue after everyday activities | 2.46 | 2.39 | 2.73 | 2.77 | 2.18 | 2.00 | 2.58 | 2.78 | 2.05 | 2.13 | 3.30 | 2.00 | 2.5 |

| PEM | Mentally tired after the slightest effort | 2.29 | 2.52 | 3.00 | 2.62 | 2.71 | 2.37 | 2.65 | 3.00 | 2.11 | 1.87 | 3.40 | 1.50 | 2.35 |

| PEM | Physically tired after minimum exercise | 2.67 | 2.78 | 3.10 | 2.65 | 2.65 | 1.95 | 2.84 | 3.06 | 2.18 | 2.27 | 3.30 | 1.72 | 2.35 |

| PEM | Physically drained or sick after mild activity | 2.38 | 2.65 | 2.80 | 2.69 | 2.59 | 2.05 | 2.65 | 2.89 | 2.00 | 2.13 | 3.10 | 1.61 | 2.05 |

| PEM | Muscle fatigue after mild physical activity | 2.33 | 2.48 | 3.00 | 2.65 | 2.12 | 2.21 | 2.74 | 3.00 | 1.47 | 2.47 | 3.40 | 1.39 | 1.6 |

| PEM | Worsening of symptoms after mild physical activity | 2.67 | 2.70 | 3.07 | 2.65 | 2.47 | 2.00 | 2.91 | 3.11 | 2.11 | 2.53 | 3.60 | 1.61 | 1.6 |

| PEM | Worsening of symptoms after mild mental activity | 2.21 | 2.52 | 2.97 | 2.73 | 2.53 | 2.05 | 2.65 | 2.67 | 1.84 | 2.20 | 3.50 | 1.17 | 1.45 |

| PEM | Difficulty reading (dyslexia) after mild physical or mental activity | 1.67 | 1.78 | 2.43 | 2.69 | 1.47 | 1.47 | 1.60 | 2.11 | 0.61 | 1.87 | 3.40 | 0.50 | 0.85 |

| Sleep | Unrefreshing sleep | 2.33 | 2.96 | 2.90 | 2.77 | 2.65 | 2.26 | 3.07 | 2.89 | 2.39 | 2.60 | 3.40 | 1.56 | 2.1 |

| Sleep | Need to nap daily | 2.58 | 1.96 | 2.70 | 2.77 | 3.24 | 2.26 | 2.67 | 2.61 | 1.71 | 1.20 | 3.10 | 2.11 | 1.9 |

| Sleep | Problems falling asleep | 1.17 | 2.04 | 1.90 | 2.00 | 2.88 | 1.32 | 2.16 | 2.67 | 1.84 | 1.80 | 2.10 | 1.11 | 2.25 |

| Sleep | Problems staying asleep | 1.21 | 1.61 | 2.43 | 2.23 | 2.47 | 2.21 | 2.47 | 2.67 | 1.53 | 1.27 | 3.10 | 1.17 | 2.7 |

| Sleep | Waking up early in the morning (e.g. 3 AM) | 0.96 | 1.17 | 2.30 | 1.85 | 1.94 | 2.11 | 2.19 | 2.22 | 0.95 | 1.53 | 2.70 | 1.06 | 2.35 |

| Sleep | Sleeping all day and staying awake all night | 0.33 | 0.22 | 1.20 | 1.19 | 2.18 | 0.58 | 0.84 | 1.33 | 0.58 | 0.20 | 1.60 | 0.61 | 0.5 |

| Sleep | Daytime drowsiness | 2.00 | 1.78 | 2.67 | 2.62 | 2.59 | 1.63 | 1.93 | 2.44 | 1.92 | 1.60 | 3.20 | 1.39 | 1.3 |

| pain | Pain or aching in muscles | 2.29 | 2.09 | 2.70 | 2.15 | 2.06 | 2.05 | 2.56 | 3.17 | 1.26 | 2.20 | 3.40 | 1.89 | 2.3 |

| pain | Joint pain | 1.79 | 1.70 | 2.63 | 2.08 | 1.41 | 1.42 | 2.47 | 3.00 | 0.97 | 2.20 | 3.20 | 1.06 | 2.5 |

| pain | Eye pain | 0.62 | 1.39 | 1.73 | 1.58 | 1.65 | 1.11 | 1.63 | 2.28 | 1.00 | 1.47 | 2.50 | 0.39 | 0.75 |

| pain | Chest pain | 0.50 | 0.83 | 1.53 | 1.38 | 1.06 | 0.84 | 1.35 | 1.83 | 0.50 | 1.20 | 2.50 | 0.33 | 0.85 |

| pain | Bloating | 0.92 | 1.39 | 1.97 | 1.77 | 1.47 | 0.89 | 1.70 | 2.44 | 1.32 | 2.13 | 2.10 | 0.44 | 2.25 |

| pain | Abdomen / stomach pain | 0.54 | 1.65 | 1.73 | 1.96 | 1.53 | 0.95 | 1.70 | 2.44 | 1.55 | 2.33 | 2.30 | 0.61 | 1.75 |

| pain | Headaches | 2.25 | 2.57 | 2.40 | 2.42 | 2.47 | 1.68 | 1.86 | 2.67 | 1.82 | 2.13 | 3.20 | 1.17 | 1.55 |

| pain | Aching of the eyes or behind the eyes | 0.79 | 1.35 | 1.70 | 1.92 | 1.65 | 0.84 | 1.51 | 1.83 | 0.79 | 1.47 | 2.50 | 0.50 | 0.6 |

| pain | Sensitivity to pain | 0.88 | 0.52 | 1.97 | 1.73 | 0.18 | 0.84 | 1.26 | 2.06 | 0.53 | 1.20 | 3.20 | 0.50 | 1.05 |

| pain | Myofascial pain | 0.62 | 0.35 | 1.43 | 0.77 | 0.12 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 2.06 | 0.29 | 0.47 | 2.70 | 0.06 | 0.4 |

| neurocognitive | Muscle twitches | 0.96 | 1.13 | 1.70 | 1.62 | 0.76 | 1.63 | 1.28 | 2.17 | 0.21 | 1.27 | 2.40 | 0.67 | 1.3 |

| neurocognitive | Muscle weakness | 1.67 | 2.39 | 2.43 | 2.46 | 0.94 | 2.11 | 2.14 | 2.28 | 0.95 | 1.73 | 3.30 | 0.83 | 1.55 |

| neurocognitive | Sensitivity to noise | 1.50 | 2.00 | 2.53 | 2.85 | 2.12 | 2.26 | 2.63 | 3.06 | 1.66 | 1.67 | 3.30 | 0.83 | 2.1 |

| neurocognitive | Sensitivity to bright lights | 1.38 | 1.96 | 2.53 | 2.65 | 1.65 | 1.79 | 2.14 | 2.50 | 1.34 | 2.13 | 2.90 | 0.61 | 1.6 |

| neurocognitive | Problems remembering things | 1.83 | 2.22 | 2.87 | 2.38 | 1.94 | 2.58 | 2.05 | 2.89 | 1.71 | 2.07 | 3.30 | 1.06 | 1.65 |

| neurocognitive | Difficulty paying attention for a long period of time | 2.21 | 2.78 | 3.13 | 2.85 | 2.53 | 2.58 | 2.49 | 2.94 | 1.68 | 2.27 | 3.60 | 1.00 | 1.7 |

| neurocognitive | Difficulty finding the right word to say, or expressing thoughts | 1.67 | 2.30 | 2.83 | 2.35 | 1.94 | 2.26 | 2.07 | 2.50 | 1.42 | 1.87 | 3.20 | 0.89 | 1.7 |

| neurocognitive | Difficulty understanding things | 1.54 | 1.83 | 2.30 | 2.46 | 1.06 | 2.11 | 1.49 | 1.72 | 0.79 | 1.07 | 3.00 | 0.39 | 0.8 |

| neurocognitive | Only able to focus on one thing at a time | 2.00 | 2.17 | 2.90 | 2.62 | 2.12 | 2.42 | 2.37 | 2.56 | 1.50 | 2.07 | 3.50 | 0.78 | 1.3 |

| neurocognitive | Unable to focus vision | 0.75 | 0.74 | 1.80 | 1.50 | 0.71 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.33 | 0.37 | 0.53 | 2.70 | 0.11 | 0.5 |

| neurocognitive | Unable to focus attention | 1.17 | 1.91 | 2.10 | 2.31 | 1.88 | 1.89 | 1.70 | 2.00 | 0.71 | 0.93 | 3.20 | 0.22 | 1.1 |

| neurocognitive | Loss of depth perception | 0.29 | 0.78 | 1.67 | 1.77 | 0.24 | 1.16 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 0.60 | 2.90 | 0.11 | 0.55 |

| neurocognitive | Slowness of thought | 1.75 | 2.39 | 2.77 | 2.69 | 1.94 | 2.16 | 1.84 | 2.56 | 1.24 | 1.73 | 3.30 | 0.33 | 1.35 |

| neurocognitive | Absent-mindedness or forgetfulness | 1.38 | 2.17 | 2.83 | 2.54 | 1.88 | 2.26 | 1.88 | 2.50 | 1.26 | 1.33 | 3.30 | 0.83 | 1.25 |

| neurocognitive | Feeling disoriented | 0.46 | 0.83 | 1.97 | 1.96 | 0.47 | 1.00 | 0.72 | 1.50 | 0.29 | 1.07 | 2.90 | 0.17 | 0.2 |

| neurocognitive | Slowed speech | 0.54 | 1.43 | 1.90 | 1.65 | 0.47 | 1.32 | 0.60 | 1.22 | 0.39 | 0.73 | 2.50 | 0.11 | 0.2 |

| neurocognitive | Poor coordination | 1.04 | 1.39 | 2.03 | 2.12 | 0.41 | 1.53 | 1.23 | 1.89 | 0.50 | 1.27 | 3.30 | 0.44 | 0.6 |

| autonomic | Bladder problems | 0.88 | 0.30 | 1.00 | 1.65 | 0.41 | 0.89 | 1.05 | 1.72 | 0.29 | 1.27 | 2.10 | 0.22 | 0.9 |

| autonomic | Irritable bowel problems | 0.62 | 1.39 | 1.87 | 2.15 | 1.29 | 0.58 | 1.58 | 2.61 | 1.39 | 2.33 | 2.80 | 0.61 | 2.3 |

| autonomic | Nausea | 0.71 | 1.43 | 1.53 | 1.88 | 1.35 | 0.63 | 1.12 | 2.00 | 1.29 | 1.53 | 2.40 | 0.33 | 1 |

| autonomic | Feeling unsteady on feet | 0.96 | 2.04 | 1.73 | 2.54 | 1.12 | 1.68 | 1.81 | 1.83 | 0.79 | 1.27 | 3.10 | 0.44 | 1.35 |

| autonomic | Shortness of breath or trouble catching breath | 0.83 | 1.39 | 1.60 | 1.85 | 1.41 | 1.26 | 1.35 | 1.94 | 0.82 | 1.20 | 2.80 | 0.22 | 0.85 |

| autonomic | Dizziness or fainting | 0.62 | 1.87 | 1.47 | 2.23 | 1.35 | 1.74 | 1.70 | 2.00 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 2.60 | 0.39 | 1 |

| autonomic | Irregular heart beats | 1.04 | 1.22 | 1.33 | 1.62 | 1.18 | 1.21 | 1.53 | 1.94 | 0.92 | 1.27 | 2.20 | 0.50 | 0.55 |

| autonomic | Heart beats quickly after standing | 0.92 | 2.17 | 1.33 | 2.31 | 1.41 | 0.84 | 1.21 | 1.89 | 0.71 | 1.20 | 2.50 | 0.39 | 0.45 |

| autonomic | Blurred or tunnel vision after standing | 0.33 | 1.74 | 1.30 | 2.19 | 0.47 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 1.28 | 0.47 | 0.87 | 2.60 | 0.39 | 0.05 |

| autonomic | Graying or blacking out after standing | 0.42 | 2.09 | 1.83 | 2.50 | 1.35 | 1.21 | 1.72 | 1.78 | 1.08 | 1.33 | 2.80 | 0.44 | 0.55 |

| autonomic | Urinary urgency | 1.29 | 0.35 | 1.47 | 2.54 | 1.24 | 1.68 | 1.77 | 1.78 | 0.89 | 1.80 | 2.40 | 0.83 | 1.2 |

| autonomic | Waking up at night to urinate | 1.33 | 0.70 | 1.90 | 2.46 | 1.76 | 1.68 | 2.14 | 1.67 | 1.37 | 1.67 | 2.60 | 1.00 | 1.75 |

| autonomic | Inability to tolerate an upright position | 0.62 | 2.09 | 1.20 | 2.50 | 0.35 | 1.26 | 1.60 | 2.11 | 0.61 | 0.93 | 3.00 | 0.22 | 0.55 |

| neuroendocrine | Losing weight without trying | 0.08 | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.61 | 0.11 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 0.00 | 0.5 |

| neuroendocrine | Gaining weight without trying | 0.38 | 0.52 | 1.33 | 1.19 | 0.35 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 0.61 | 0.34 | 0.53 | 1.40 | 0.33 | 0.7 |

| neuroendocrine | Lack of appetite | 0.42 | 1.13 | 0.87 | 1.38 | 0.71 | 0.89 | 0.47 | 1.50 | 0.55 | 1.27 | 1.40 | 0.22 | 1 |

| neuroendocrine | Sweating hands | 0.46 | 0.74 | 0.50 | 0.81 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.65 | 1.06 | 0.21 | 0.33 | 1.20 | 0.11 | 0 |

| neuroendocrine | Night sweats | 0.71 | 1.52 | 1.47 | 1.73 | 1.41 | 0.63 | 1.86 | 1.56 | 1.21 | 1.00 | 2.60 | 0.72 | 1 |

| neuroendocrine | Cold limbs | 1.96 | 2.22 | 2.27 | 2.38 | 1.71 | 2.05 | 2.00 | 2.67 | 1.55 | 2.13 | 3.00 | 1.06 | 1.85 |

| neuroendocrine | Feeling chills or shivers | 1.42 | 1.48 | 1.87 | 2.04 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 1.44 | 2.06 | 0.87 | 1.80 | 2.80 | 0.17 | 1.05 |

| neuroendocrine | Feeling hot or cold for no reason | 1.71 | 1.83 | 2.00 | 2.35 | 1.29 | 1.37 | 1.93 | 2.89 | 1.42 | 1.67 | 2.90 | 0.61 | 1.45 |

| neuroendocrine | Feeling like you have a high temperature | 1.38 | 1.57 | 1.43 | 1.81 | 1.06 | 0.68 | 1.51 | 2.50 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 2.70 | 0.67 | 1 |

| neuroendocrine | Feeling like you have a low temperature | 1.17 | 0.39 | 1.20 | 1.50 | 0.47 | 0.16 | 0.74 | 1.22 | 0.53 | 1.47 | 2.30 | 0.00 | 0.95 |

| neuroendocrine | Alcohol intolerance | 0.17 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 1.85 | 0.47 | 0.68 | 0.21 | 0.78 | 0.37 | 0.80 | 1.90 | 0.00 | 0.1 |

| neuroendocrine | Intolerance to extremes of temperature | 0.92 | 1.22 | 2.00 | 2.54 | 0.82 | 0.95 | 2.30 | 2.50 | 0.97 | 2.40 | 3.40 | 0.39 | 1 |

| neuroendocrine | Fluctuations in temperature throughout the day | 1.12 | 1.26 | 1.10 | 1.85 | 0.53 | 0.32 | 1.19 | 2.67 | 0.87 | 1.07 | 2.50 | 0.50 | 1.05 |

| Immune | Sore throat | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.47 | 1.73 | 1.47 | 1.11 | 1.33 | 1.83 | 0.97 | 1.40 | 2.20 | 0.28 | 0.85 |

| Immune | Tender/sore lymph nodes | 0.71 | 0.91 | 1.50 | 1.69 | 0.76 | 0.42 | 1.07 | 1.72 | 0.42 | 1.07 | 2.40 | 0.22 | 0.45 |

| Immune | Fever | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 1.11 | 0.34 | 0.20 | 1.60 | 0.11 | 0.1 |

| Immune | Flu-like symptoms | 2.00 | 1.61 | 2.00 | 2.04 | 1.94 | 1.00 | 1.70 | 2.33 | 0.92 | 1.20 | 2.80 | 0.72 | 1.05 |

| Immune | Sensitivity to smells, food, medications, or chemicals | 0.25 | 0.70 | 1.40 | 2.46 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.19 | 1.67 | 0.76 | 1.53 | 2.30 | 0.17 | 0.8 |

| Immune | Sinus infections | 0.08 | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.85 | 1.47 | 0.74 | 0.44 | 1.94 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 2.30 | 0.06 | 0.6 |

| Immune | Viral infections with prolonged recovery periods | 0.62 | 1.17 | 0.77 | 1.23 | 0.94 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 1.94 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 2.70 | 0.06 | 0.55 |

| other | Sensitivity to mold | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.47 | 1.23 | 0.24 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 1.67 | 0.34 | 1.67 | 1.60 | 0.33 | 0.75 |

| other | Sensitivity to vibration | 0.29 | 0.96 | 1.60 | 1.96 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.84 | 1.89 | 0.26 | 1.20 | 2.60 | 0.11 | 0.6 |

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | e.g. alcohol/yeast metabolism9,10. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | serotonin syndrome features [17]. |

| 6 | autonomic dysfunction, norepinephrine physiology [18]. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | polyamine toxicity, food spoilage [28]. |

| 12 |

References

- Vaes, A. W. et al. Symptom-based clusters in people with ME/CFS: An illustration of clinical variety in a cross-sectional cohort. Journal of Translational Medicine 21, 112 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Jurek, M., Lee, J., Patel, S. & al., et. Biotic interventions in ME/CFS: Systematic review. Nutrients 16, 201 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Stallmach, A., Quickert, S., Puta, C. & Reuken, P. A. The gastrointestinal microbiota in the development of ME/CFS: A critical view and potential perspectives. Frontiers in Immunology 15, 1352744 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Günzel, D. & Yu, A. S. L. Claudins and the regulation of tight junction permeability. Physiological Reviews 93, 525–569 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Van Itallie, C. M. & Anderson, J. M. Claudins and epithelial paracellular transport. Annual Review of Physiology 68, 403–429 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Warren, J. R. & Marshall, B. J. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. The Lancet 321, 1273–1275 (1983). [CrossRef]

- Shen, L. et al. Myosin light chain kinase-dependent epithelial barrier dysfunction is regulated by NF-κb. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 409–414 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M. Intestinal barrier function in health and gastrointestinal disease. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 12836 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, C. J. Acetaldehyde metabolism in humans after ethanol ingestion: Role of polymorphisms in alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 14, 713–715 (1990).

- Kim, D. Y. et al. Acetaldehyde induces gut barrier dysfunction and microbial dysbiosis. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews 40, e1–e10 (2019).

- Camilleri, M. Bile acid diarrhea: Prevalence, pathogenesis, and therapy. Gut 58, 1364–1374 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Ridlon, J. M., Harris, S. C., Bhowmik, S., Kang, D. J. & Hylemon, P. B. Consequences of bile salt biotransformations by intestinal bacteria. Gut Microbes 7, 22–39 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Vanholder, R. et al. Uremic toxins: The middle molecules. Kidney International 63, 1934–1943 (2003).

- Niwa, T. Indoxyl sulfate is a nephro-vascular toxin. Journal of Renal Nutrition 20, S2–S6 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Sirich, T. L., Aronov, P. A., Plummer, N. S., Hostetter, T. H. & Meyer, T.W. P-cresol sulfate and indoxyl sulfate in hemodialysis patients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 24, 969–977 (2013).

- Vanholder, R., Pletinck, A., Schepers, E. & Glorieux, G. Uremic toxicity: Present state of the art. International Journal of Artificial Organs 37, 746–756 (2014).

- Boyer, E. W. & Shannon, M. Serotonin syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 352, 1112–1120 (2005).

- Goldstein, D. S. Catecholamine regulation of blood pressure in humans. Journal of Hypertension 24, 2311–2321 (2006).

- Frost, G. et al. The short-chain fatty acid acetate reduces appetite via a central homeostatic mechanism. Nature Communications 5, 3611 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y. P., Bernardi, A. & Frozza, R. L. Effects of acetate on metabolic health and disease. Nutrients 12, 419 (2020).

- Mills, E. L. et al. Succinate receptor 1 (SUCNR1) mediates intestinal inflammation and fibrosis. Nature 563, 346–350 (2018).

- Connors, J., Dawe, N. & Van Limbergen, J. Succinate and intestinal inflammation: The role of succinate dehydrogenase and succinate receptor 1. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology 6, 229–238 (2018).

- Jacobsen, D. & McMartin, K. E. Methanol and ethylene glycol poisonings: Mechanism of toxicity, clinical course, diagnosis and treatment. Medical Toxicology 1, 309–334 (1986).

- Tephly, T. R. The toxicity of methanol. Life Sciences 48, 1031–1041 (1991).

- MacFabe, D. F. et al. Neurobiological effects of intraventricular propionic acid in rats: Possible role of short chain fatty acids on the pathogenesis and characteristics of autism spectrum disorders. Behavioural Brain Research 176, 149–169 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Fattorusso, A., Di Genova, L., Dell’Isola, G. B., Mencaroni, E. & Esposito, S. Altered gut microbiota and SCFA in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research 12, 1373–1384 (2019).

- Lopes, C., Costa, A. & Brito, M. A. Polyamines in human health and disease. Clinical Nutrition 40, 5158–5170 (2021).

- Miller, K. A., Wang, Y. & Brooks, A. E. Putrescine and cadaverine: Intestinal microbiota-derived polyamines and their role in human health. Nutrients 13, 2705 (2021).

- Groeger, D. et al. Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 modulates host inflammatory processes beyond the gut. Gut Microbes 4, 325–339 (2013). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).