1. Introduction

In recent years, postmortem imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been increasingly used to investigate causes of death [

1]. These noninvasive methods play an essential role in cases involving suspicious deaths, suspected abuse, or potential medical malpractice. The primary advantages of postmortem imaging include the ability to examine the body without dissection and the relative ease of obtaining consent from the family of the deceased compared with traditional autopsy. Additionally, using imaging as a preliminary screening tool can help reduce unnecessary autopsies [

2]. However, limitations remain, such as lower diagnostic accuracy compared to autopsy and challenges in diagnosing certain conditions, such as pulmonary embolism [

2].

Artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, particularly deep learning (DL), have been widely adopted across various fields, from object recognition to conversational AI, and are becoming indispensable in daily life. Research on the application of image processing and DL to the interpretation of medical images, including CT and MRI, has become increasingly active, with progress being made in the field of medical imaging [

3,

4,

5]. DL-based support for image diagnosis has the potential to improve the efficiency of interpretation tasks of radiologists, enhance diagnostic accuracy, and reduce the risk of oversight [

6,

7,

8]. In particular, postmortem imaging is often conducted by nonspecialists in radiology; thus, applying DL to postmortem imaging could improve diagnostic performance and reduce both labor and costs.

To build a reliable DL model, collecting a substantial amount of high-quality labeled data is essential [

9]. However, the number of postmortem imaging cases is significantly lower than that of standard CT and MRI scans, leading to insufficient data for training DL models. To address this issue, this study aims to overcome the data scarcity problem by using publicly available datasets of non-postmortem medical images for training.

Different DL models have different structures and parameters. For practical implementation, it is crucial to optimize the predictive accuracy and reduce costs. Therefore, this study evaluates the efficiency of different models by comparing their accuracy, training time, inference time, and number of parameters.

This study aims to construct a model that can accurately detect intracranial hemorrhages in postmortem imaging, where data are limited, by employing transfer learning. By comparing diagnostic accuracy and computational costs, this study aims to provide insights into the effectiveness of DL in postmortem imaging.

2. Materials and Methods

This study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects in Japan. This study was approved by the institutional review board and conducted according to the guidelines of the committee (approval number: B200131). The requirement for informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective design of the study.

2.1. Postmortem Imaging Dataset

From cases autopsied at a university of legal medicine between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2020, 224 cases were selected, in which detailed autopsy records were available and radiographic images provided by investigative or medical institutions were accessible. Among these, 124 cases with axial head CT images captured after the estimated time of death were used as the test dataset. Of the 124 patients, 98 were male and 26 were female, aged between 0 and 97 years, with an average age of 58 years. Head hemorrhages were observed during conventional autopsy in 59 patients (48%).

2.2. Non-Postmortem Imaging Dataset

To train the DL model for intracranial hemorrhage detection, the RSNA Intracranial Hemorrhage Detection Challenge Dataset (RSNA2019 Dataset) [

10], published by the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA), was used as the training dataset. This dataset includes over 75,000 head CT axial slice images, each labeled with six types of hemorrhage: five specific types (epidural, intraparenchymal, intraventricular, subarachnoid, and subdural) and a label indicating the presence of any hemorrhage (any). The dataset was randomly divided into training (80%) and validation (20%) datasets. The latter dataset was used for early termination. Multiple DL models available in the pytorch-image-models (timm) [

11] were fine-tuned. The label indicating any hemorrhage (any) was used as the ground truth for the DL models.

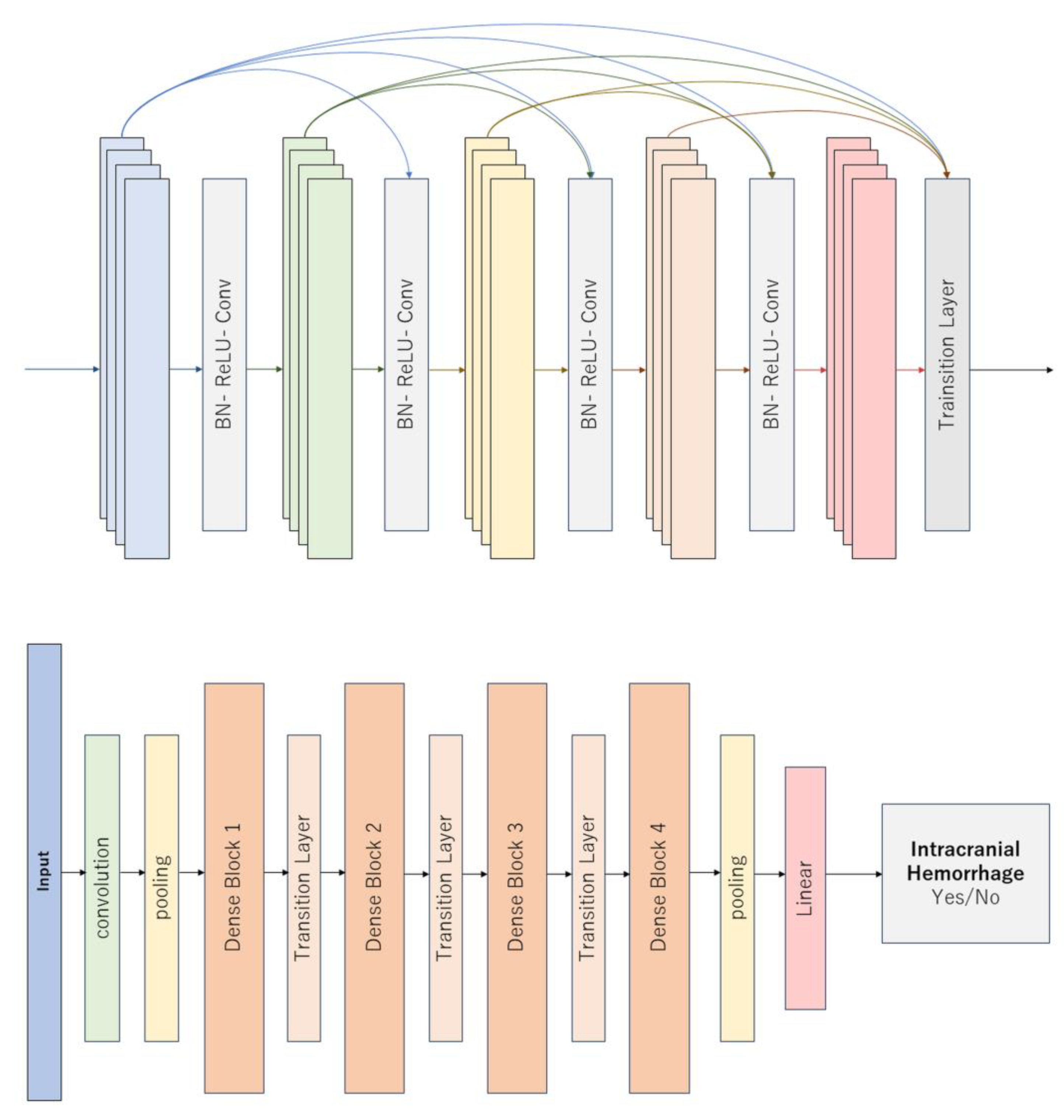

2.3. DL Models

15 DL models were selected from the timm library.

Table 1 lists the models, their release dates, and the number of parameters. A classification head was added to each model to enable the output to indicate the presence or absence of an intracranial hemorrhage.

Figure 1 illustrates a representative DL model.

2.3.1. Image Processing Steps for Each Case

Head CT images from the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine files were first loaded for each case. The original images were then adjusted to three different window settings [

10], resized to 256×256 (or 224×224), and converted into arrays of size 3×256×256 (or 3×224×224). The hyperparameters were fixed as follows: Adam optimizer, learning rate of 2×10

-5, batch size of 32, and early training termination. All the models were trained using identical hyperparameters.

2.3.2. Inference on Postmortem Images

A test dataset consisting of postmortem images was used to evaluate the fine-tuned DL models from the timm library. The ground truth was defined based on the presence or absence of a forensic intracranial hemorrhage. For each axial slice, the model, pretrained via transfer learning, calculated a probability indicating whether any type of hemorrhage (any) was present. Among these slices, the highest probability was then considered the “hemorrhage score” for that case. This score was compared with the ground truth labels for evaluation.

2.3.3. Evaluation Methods

Following training, the validation loss was calculated and the total training time was recorded. The inference time for the test set was measured. Subsequently, based on the hemorrhage score generated by the DL model and the presence or absence of a hemorrhage determined by autopsy, a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was created for patient-based evaluation and the Area Under the ROC Curve (ROC AUC) was computed. Furthermore, the Youden index was used to determine a threshold value and the sensitivity and specificity at that threshold were then calculated.

2.3.4. Statistical Analysis

To investigate the relationships between the four metrics (ROC AUC, training time, inference time, and number of parameters), Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were calculated. Scatter plots were created for each pairwise combination of the metrics.

2.3.5. Reader Study by a Radiology Resident

To provide a human benchmark, a fourth-year radiology resident independently reviewed the same postmortem head CT test set used for model evaluation. Cases were anonymized and presented in random order. The reader was blinded to autopsy findings, clinical information, and all model outputs. For each case, the reader assigned a five-point likelihood score for the presence of any intracranial hemorrhage (1 = definitely absent, 2 = probably absent, 3 = indeterminate, 4 = probably present, and 5 = definitely present). Using these ordinal scores and the autopsy-based reference standard, a patient-level ROC curve was constructed and the ROC AUC was computed. For comparability with the DL models, an optimal cutoff was determined using the Youden index and the sensitivity and specificity at that threshold were calculated.

3. Results

Table 2 lists the training and inference times, ROC AUC, sensitivity, and specificity determined using the Youden index for each model. The training time ranged from approximately 4×104 to 1.75×105 s, while the inference time ranged from approximately 100 to 200 s. Overall, the ROC AUC values were in the high 80–90% range, with the highest value being 90.7% for DenseNet201.

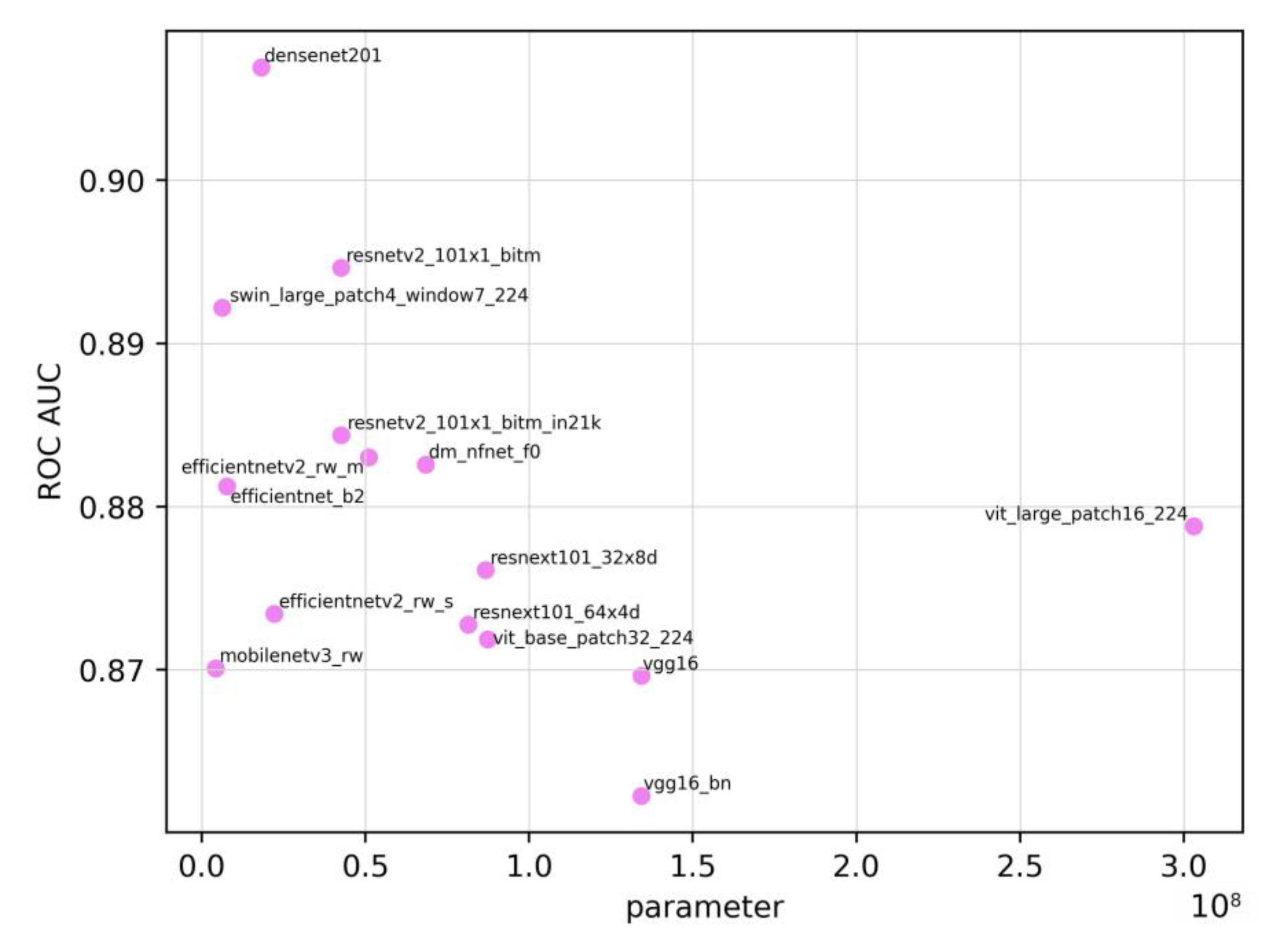

Figure 2 shows the relationship between the number of parameters and the ROC AUC. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between the ROC AUC and the number of parameters was -0.472. Owing to the limited number of models (n=15), p=0.076, indicating no statistically significant correlation. Although models with a larger number of parameters are generally thought to be more complex and perform better, a negative correlation was observed in this study.

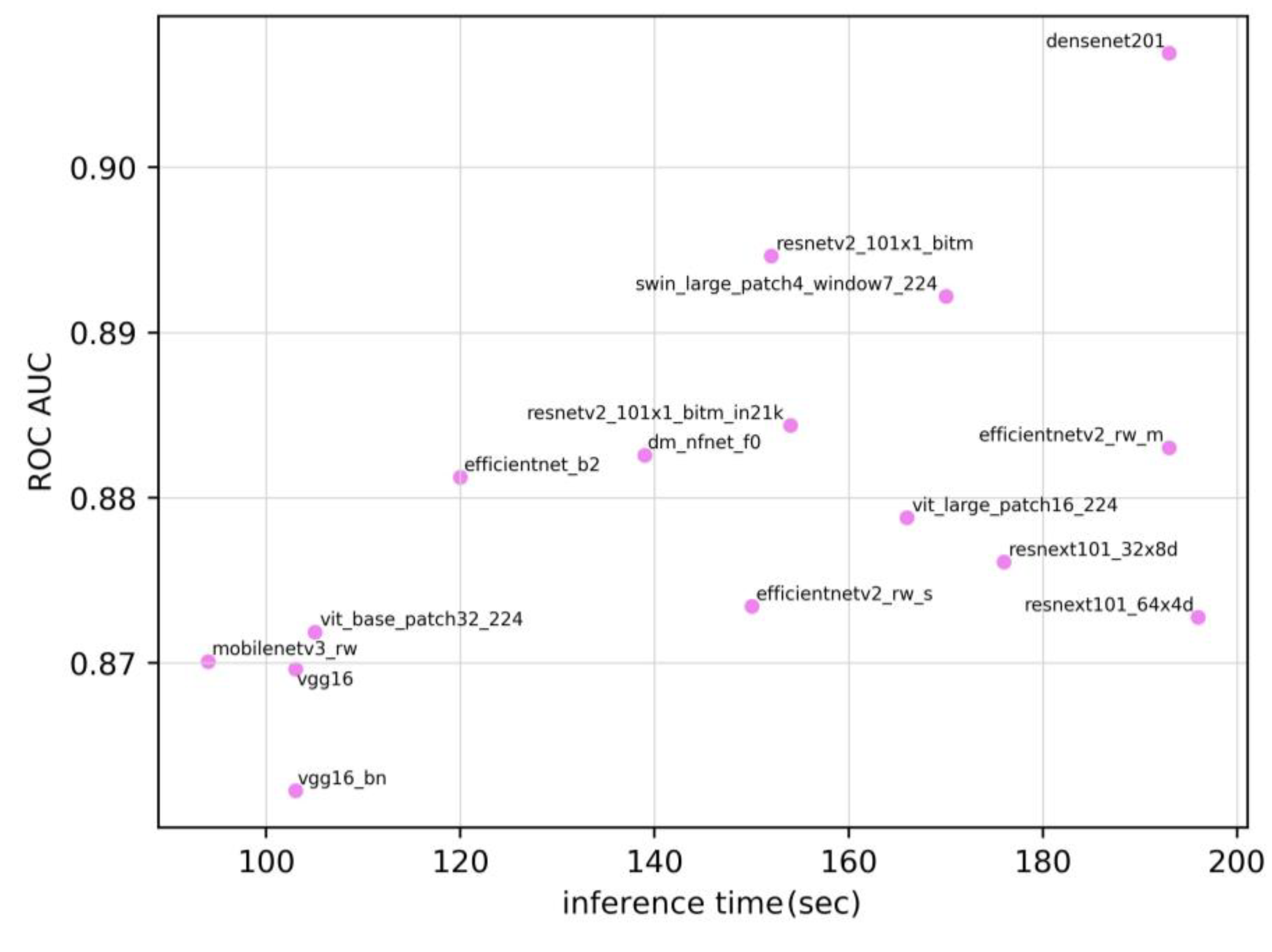

Figure 3 shows the relationship between the inference time and the ROC AUC. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was 0.586 (p=0.022). These results are indicative of a moderate positive correlation between the ROC AUC and inference time.

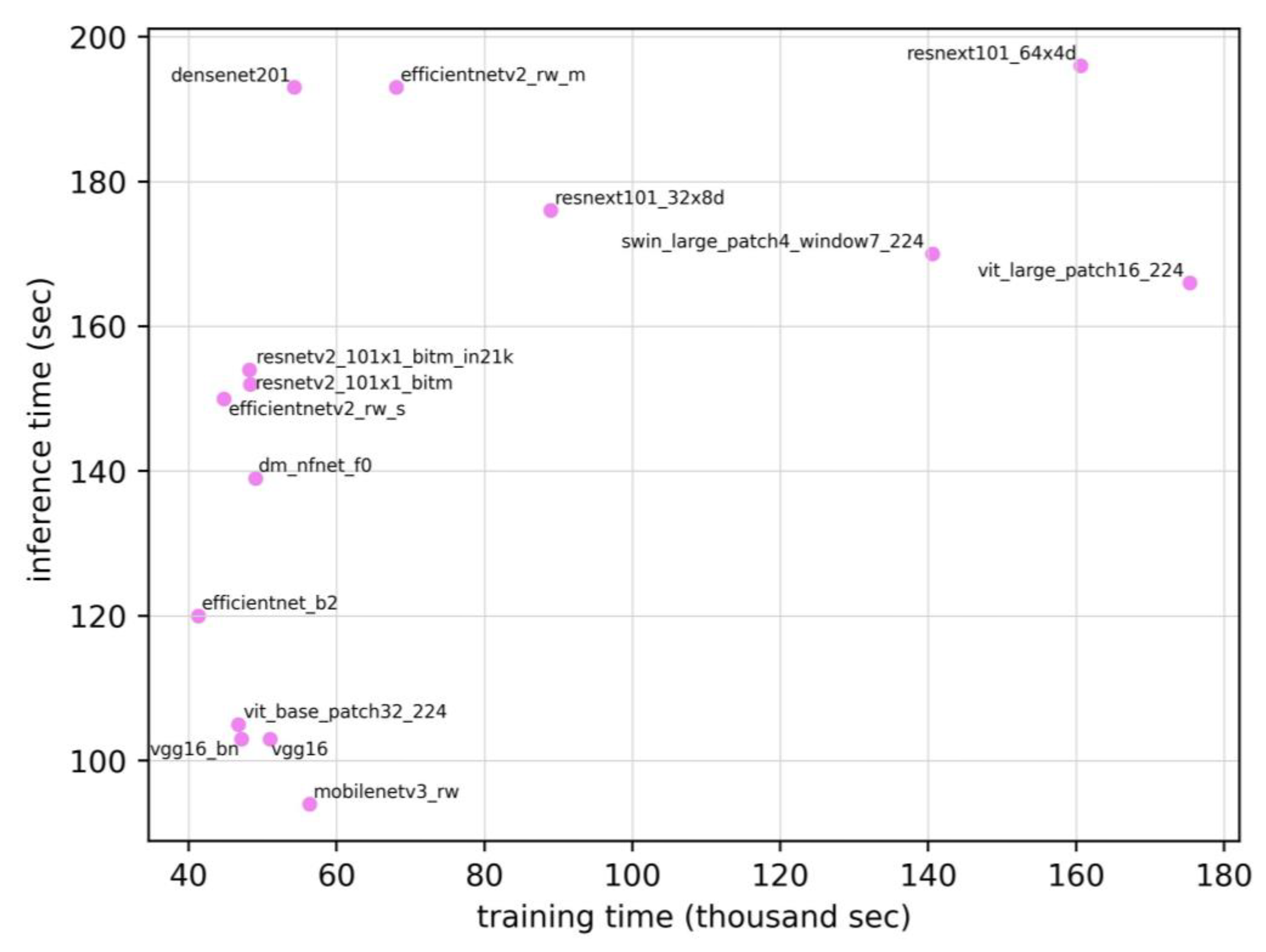

Figure 4 shows the relationship between the training time and inference time. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between the training time and inference time was 0.579 (p=0.024), suggesting a moderate positive correlation. Therefore, the models requiring longer training times tended to exhibit longer inference times. Meanwhile, the correlation coefficients for the other pairs (ROC AUC vs. training time, training time vs. number of parameters, and inference time vs. number of parameters) were 0.129, 0.144, and -0.038, respectively. None of these relationships were statistically significant. On the same test set, the radiology resident achieved an ROC AUC of 0.810, which was lower than the range observed for the DL models (0.862–0.907).

4. Discussion

In this study, transfer learning was performed on 15 different DL models using head CT images from non-postmortem CT examinations as training data. The resulting trained models were evaluated using postmortem head CT images as an external validation dataset. When conducting binary classification (presence or absence of a hemorrhage) on a patient basis, the ROC AUCs of the 15 DL models ranged from 0.862 to 0.907. Among the models, DenseNet201 performed the best, attaining an ROC AUC of 90.7%. A moderate negative correlation was observed between the ROC AUC and the number of parameters, whereas a moderate positive correlation was observed between the ROC AUC and inference time, as well as between training time and inference time. Notably, when benchmarked against a radiology resident who reviewed the same cases, all DL models achieved higher patient-level ROC AUCs (0.862–0.907) than the resident (0.810), indicating trainee-level or better performance on this dataset.

Although numerous studies have compared the performance of multiple models using general image datasets, such as ImageNet, most medical imaging studies have only compared a limited number of models. The strength of this study lies in the comparison of 15 different models under identical conditions. Along with model performance, the inference time, which is often a critical factor in practical applications, was also considered. The results demonstrated a negative correlation between the ROC AUC and the number of parameters, and positive correlations between the ROC AUC and inference time and between the training time and inference time.

In addition, a uniform batch size and learning rate were maintained across all models, which represents a major contribution of this study. The correlations observed between the ROC AUC and number of parameters, as well as between the ROC AUC and inference time, may be useful for model selection. However, it is important to note that the hyperparameters employed here may not be optimal for each model, and the results may change with more fine-tuned adjustments.

The new-generation Transformer-based models used in this study, specifically ViT and Swin, are relatively new architectures. Although they tend to have fewer parameters, their structures are more complex, often resulting in higher computational requirements. This complexity may partially explain the negative correlation between the number of parameters and ROC AUC.

In this study, the best DL model achieved an ROC AUC of 90.7%. As cranial processing for autopsy is highly labor-intensive, the findings of this study suggest that combining postmortem imaging with DL models could potentially reduce the workload of forensic pathologists. This human benchmark comparison suggests that, even under domain shift to postmortem imaging, the models perform favorably relative to a trainee reader, supporting their potential as decision-support tools in forensic workflows.

The training dataset used in this study consisted of head CT images from living patients; therefore, the model did not consider the characteristic changes of normal findings or hemorrhages commonly observed in postmortem CT images. To further improve accuracy, it is necessary to train the model using actual postmortem imaging data.

This study had several limitations. First, the number of training cases was small and the resulting accuracy may be insufficient for clinical applications. Furthermore, only a single-center external validation was conducted, and further validation at additional institutions is required. Our training focused exclusively on intracranial hemorrhages and thus did not include conditions such as cerebral infarction [

22], other intracranial pathologies, or pathologies in other organs [

7]. Finally, the reader comparison involved a single radiology resident; performance relative to board-certified radiologists and inter-reader variability were not assessed.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study developed a model that exhibited relatively high accuracy in discriminating intracranial hemorrhages on postmortem head CT scans using transfer learning. This study compared 15 different DL models using real clinical data, and the results can assist in guiding model selection in the application of AI in healthcare. To improve the ROC AUC further, more extensive training data are required, including the integration of datasets from multiple medical institutions and an increased number of postmortem CT cases. In addition, a more comprehensive model is required for actual applications in postmortem imaging.

Author Contributions

R.M: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing original draft, and review & editing. H.M: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing original draft, and review & editing. M.S: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, and Writing review & editing. T.M: Conceptualization, Methodology, and Writing review & editing. M.N: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, and Writing review & editing. A.K.K: Conceptualization, Data curation, and Writing review & editing. G.Y: Data curation, Resources, Validation, and Writing review & editing. M.T: Data curation, Investigation, and Writing review & editing. T.K: Data curation, Investigation, and Writing review & editing. Y.U: Data curation, Investigation, and Writing review & editing. R.K: Data curation, Investigation, and Writing review & editing. T.M: Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, and Writing review & editing.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers: 23K17229 and 23KK0148).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective design of the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy concerns, the data cannot be made publicly available. Individuals who are interested in accessing the data are requested to contact the authors directly. The datasets used in this study have different availability restrictions due to their nature and source:

Non-Postmortem Dataset: The RSNA Intracranial Hemorrhage Detection Challenge Dataset (RSNA2019) used for model training is publicly available through the Radiological Society of North America at

https://www.rsna.org/rsnai/ai-image-challenge/rsna-intracranial-hemorrhage-detection-challenge-2019.

Postmortem Dataset: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, H.M. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of Generative AI in Scientific Writing: During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI) to translate drafts written in Japanese into English. Following the use of this tool, the authors carefully reviewed and revised the translated content as necessary. The authors are responsible for the contents of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| AUC |

Area under the curve |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| DL |

Deep learning |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| ROC |

Receiver operating characteristic |

| ROC AUC |

Area under the ROC curve |

| RSNA |

Radiological Society of North America |

References

- Bolliger, S.A.; Thali, M.J. Imaging and virtual autopsy: looking back and forward. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, I.S.D.; Benamore, R.E.; Benbow, E.W.; Lee, S.H.; Harris, J.N.; Jackson, A.; Mallett, S.; Patankar, T.; Peebles, C.; Roobottom, C.; Traill, Z.C. Post-mortem imaging as an alternative to autopsy in the diagnosis of adult deaths: a validation study. Lancet, Elsevier BV. 2012, 379, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.Q.; Wang, J.Y.; Yu, S.Y.; Wu, G.G.; Wei, Q.; Deng, Y.B.; Wu, X.L.; Cui, X.W.; Dietrich, C.F. Artificial intelligence in medical imaging of the liver. World J. Gastroenterol., Baishideng Publishing Group Inc. 2019, 25, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, D.; Slomka, P.J.; Leeson, P.; Comaniciu, D.; Shrestha, S.; Sengupta, P.P.; Marwick, T.H. Artificial intelligence in cardiovascular imaging: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., Elsevier BV. 2019, 73, 1317–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Zhu, J.; Duan, Z.; Liao, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, W. Artificial intelligence in spinal imaging: current status and future directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, H.; Kitajima, K.; Kono, A.K.; Kuribayashi, K. Kijima, T.; Hashimoto, M.; Hasegawa, S.; Yamakado, K.; Murakami, T. Prognosis prediction of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma using conditional variational autoencoder on 3D PET images and clinical data. Med. Phys. 2023, 50, 7548–7557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, H.; Nishio, M.; Kanda, T.; Kojita, Y.; Kono, A.K.; Hori, M.; Teshima, M.; Otsuki, N.; Nibu, K.I.; Murakami, T. Diagnostic accuracy of deep-learning with anomaly detection for a small amount of imbalanced data: discriminating malignant parotid tumors in MRI. Sci. Rep., Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 2010, 10, 19388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishio, M.; Noguchi, S.; Matsuo, H.; Murakami, T. Automatic classification between COVID-19 pneumonia, non-COVID-19 pneumonia, and the healthy on chest X-ray image: combination of data augmentation methods. Sci. Rep., Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 2020, 10, 17532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, R.; Nikki, S.; Beg, R.; Ranjan, S.; Gope, S.K.; Mallick, R.R.; Dutta, A. A review of image detection, recognition and classification with the help of machine learning and artificial intelligence. SSRN Journal., Elsevier BV 2020. [CrossRef]

- Flanders, A.E.; Prevedello, L.M.; Shih, G.; Halabi, S.S.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Ball, R.; Mongan, J.T.; Stein, A.; Kitamura, F.C.; Lungren, M.P.; Choudhary, G.; Cala, L.; Coelho, L.; Mogensen, M.; Morón, F.; Miller, E.; Ikuta, I.; Zohrabian, V.; McDonnell, O.; Lincoln, C.; Shah, L.; Joyner, D.; Agarwal, A.; Lee, R.K.; Nath, J. RSNA-ASNR 2019 Brain Hemorrhage CT Annotators, Construction of a machine learning dataset through collaboration: the RSNA 2019 brain CT hemorrhage challenge. Radiol. Artif. Intell., Radiological Society of North America (RSNA). 2020, 2, e190211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PyTorch-image-models: the largest collection of PyTorch image encoders / backbones. Including train, eval, inference, export scripts, and pretrained weights—ResNet, ResNeXT, EfficientNet, NFNet, Vision Transformer (ViT), MobileNetV4, MobileNet-V3 & V2, RegNet, DPN, CSPNet, Swin Transformer, MaxViT, CoAtNet, ConvNeXt, and more. GitHub. https://github.com/huggingface/pytorch-image-models. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; van der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. arXiv. 2016. cs.CV. http://arxiv.org/abs/1608.06993. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Brock, A.; De, S.; Smith, S.L.; Simonyan, K. High-performance large-scale image recognition without normalization. arXiv. 2021. cs.CV. http://arxiv.org/abs/2102.06171. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv [cs.LG]. 2019. http://arxiv.org/abs/1905.11946. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNetV2: smaller models and faster training. arXiv. 2021. cs.CV. http://arxiv.org/abs/2104.00298. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; Le, Q.V.; Adam, H. Searching for MobileNetV3. arXiv. 2019. cs.CV. http://arxiv.org/abs/1905.02244. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Identity mappings in deep residual networks. arXiv. 2016. cs.CV. http://arxiv.org/abs/1603.05027. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Xie, S.; Girshick, R.; Dollár, P.; Tu, Z.; He, K. Aggregated residual transformations for deep neural networks. arXiv. 2016. cs.CV. http://arxiv.org/abs/1611.05431. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: hierarchical vision Transformer using shifted windows. arXiv. 2021. cs.CV. http://arxiv.org/abs/2103.14030. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv. 2014. cs.CV. http://arxiv.org/abs/1409.1556. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterhiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; Uszkoreit, J.; Houlsby, N. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv. 2020. cs.CV. http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.11929. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Nishio, M.; Koyasu, S.; Noguchi, S.; Kiguchi, T.; Nakatsu, K.; Akasaka, T.; Yamada, H.; Itoh, K. Automatic detection of acute ischemic stroke using non-contrast computed tomography and two-stage deep learning model. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed., Elsevier BV. 2020, 196, 105711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Identity mappings in deep residual networks. arXiv. 2016. cs.CV. http://arxiv.org/abs/1603.05027. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Xie, S.; Girshick, R.; Dollár, P.; Tu, Z.; He, K. Aggregated residual transformations for deep neural networks. arXiv. 2016. cs.CV. http://arxiv.org/abs/1611.05431. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: hierarchical vision Transformer using shifted windows. arXiv. 2021. cs.CV. http://arxiv.org/abs/2103.14030. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv. 2014. cs.CV. http://arxiv.org/abs/1409.1556. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterhiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; Uszkoreit, J.; Houlsby, N. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv. 2020. cs.CV. http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.11929. (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Nishio, M.; Koyasu, S.; Noguchi, S.; Kiguchi, T.; Nakatsu, K.; Akasaka, T.; Yamada, H.; Itoh, K. Automatic detection of acute ischemic stroke using non-contrast computed tomography and two-stage deep learning model. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed., Elsevier BV. 2020, 196, 105711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).