1. Introduction

Subjective well-being (SWB) in children represents a multifaceted construct that includes cognitive evaluations of life satisfaction and affective experiences of happiness and positive emotions, serving as a pivotal indicator of overall psychological health and development [

1,

2]. Building on established theoretical traditions, our conceptualization of SWB is anchored in both Ryff’s eudaimonic model, which emphasizes dimensions such as self-acceptance, personal growth, and purpose in life, and Seligman’s PERMA framework from positive psychology, which highlights positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment. These perspectives provide a multidimensional foundation that aligns with our focus on children’s well-being in diverse international contexts [

3,

4,

5]. Globally, SWB is linked to improved academic performance, stronger social relationships, and reduced risk of mental health issues such as anxiety and depression in later life [

6,

7]. However, in the context of increasing sedentary lifestyles and declining physical activity levels among youth, understanding the determinants of SWB has become a public health priority [

8]. Physical activity and sports participation have emerged as promising factors, with evidence suggesting they contribute to enhanced self-esteem, stress reduction, and social integration, all of which bolster SWB [

9].

Yet, the mechanisms underlying these associations remain incompletely understood, particularly in diverse multinational cohorts where cultural and socioeconomic variations may influence outcomes. Recent systematic evidence highlights that, although positive psychological constructs such as optimism, mental toughness, self-compassion, and perceived social support have shown consistent links with well-being, only a minority of studies (3 out of 11) directly connected these factors with measurable sports performance, often mediated by motivational processes and contextual variables like coach autonomy support or team emotional culture. This underscores both the complexity of the pathways involved and the need for more robust, culturally sensitive methodologies to disentangle how these “bright side” variables operate in different sporting populations [

10].

Physical literacy (PL) has gained traction as a holistic concept that encompasses not only physical competence but also the motivation, confidence, knowledge, and understanding necessary for lifelong engagement in physical activity [

11,

12]. Defined by international consensus as the foundation for active living, PL integrates physical, psychological, social, and cognitive domains, making it a potential mediator in the pathway from sports participation to SWB [

13]. For instance, children with higher PL are more likely to enjoy physical activities, leading to sustained participation and positive affective experiences [

14]. This aligns with broader health promotion models that emphasize the role of PL in fostering resilience and well-being during critical developmental stages [

15]. Despite its promise, empirical investigations into PL’s mediating role are limited, often confined to small-scale studies in single countries, neglecting the non-linear and heterogeneous effects that may vary by age, gender, or cultural context. Recent systematic reviews emphasize that much of the current evidence still relies on cross-sectional designs with reduced samples, overlooking the multidimensional nature of psychological well-being proposed by eudaimonic frameworks such as Ryff’s model. Moreover, findings suggest that factors like self-acceptance, life purpose, and personal growth dimensions closely tied to physical activity may operate differently across populations, yet remain underexplored in sport-specific contexts [

16,

17].

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) provides a theoretical framework for understanding how PL mediates the sports-SWB link, positing that fulfillment of basic psychological needs autonomy, competence, and relatedness drives intrinsic motivation and well-being [

18,

19]. In sports settings, PL enhances competence through skill mastery and confidence, while organized activities satisfy relatedness via social interactions, collectively elevating SWB [

20]. Complementarily, Positive Youth Development (PYD) frameworks highlight how sports participation cultivates assets like resilience and social competence, with PL acting as a core developmental asset [

21]. Empirical support for these theories includes studies showing that PL interventions in school-based programs improve both physical activity adherence and emotional well-being, though causal evidence is sparse [

22,

23]. Non-linear patterns, such as thresholds where moderate PL yields disproportionate SWB gains, remain underexplored, potentially due to reliance on linear analytical methods [

8].

Existing literature reveals consistent positive associations between physical activity and SWB, but mediation analyses are scarce and methodologically limited. For example, cross-sectional data from Danish schoolchildren indicate that PL is associated with psychosocial well-being, with moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) partially mediating physical but not psychosocial outcomes [

6,

9]. In adolescents, chain mediation models link PL to life satisfaction via physical activity and resilience, moderated by activity levels [

24]. Among university students as a proxy for older youth, PL influences health-related quality of life through serial mediation involving physical activity and SWB. However, these studies predominantly use traditional linear models like structural equation modeling, which assume linearity and fail to capture heterogeneity or interactions in large, diverse samples [

12]. Moreover, child-focused research (ages 6-14) is underrepresented, with few leveraging multinational datasets to account for cultural variations [

13].

Broader reviews underscore PL’s role in promoting lifelong physical activity and well-being, but emphasize gaps in causal designs and interventions [

14,

15]. For instance, systematic reviews highlight PL’s correlations with reduced psychological distress and enhanced resilience yet call for more rigorous mediation analyses using advanced methods [

16,

18]. Recent studies on PL in specific populations, such as Danish children, confirm positive links to well-being but note that MVPA mediation is limited to physical domains [

19]. In Chilean and Chinese contexts, PL mediates relationships between physical activity and mental health via resilience or mindfulness, but non-linear effects are not examined [

21,

25]. These findings suggest a need for causal machine learning (ML) approaches to dissect complex pathways, as traditional methods overlook conditional average treatment effects (CATE) and non-linearity [

22].

The current study builds on prior work using ML to predict SWB from sports participation in the same ISCWeB dataset, where models like XGBoost achieved R² ~0.50, outperforming linear regression. That study identified sports frequency as a top predictor but did not explore mediation mechanisms [

23]. Here, we extend this by investigating PL as a mediator, employing CausalForestDML to estimate total, direct, and indirect effects while handling non-linearity and heterogeneity [

8]. This approach addresses limitations in previous mediation studies, which rely on linear assumptions and small samples [

6]. By incorporating multinational data, we account for cultural variability, offering generalizable insights [

9].

Hypotheses guide this investigation: (1) PL positively mediates the association between high sports participation and SWB, with an indirect effect >0.10; (2) Effects are heterogeneous, stronger in older children or specific genders; (3) Non-linear patterns, such as thresholds in PL’s impact on SWB, will emerge, consistent with SDT’s emphasis on competence fulfillment. No preregistration was required for this secondary analysis of public data, but transparency is ensured through detailed methods and code availability [

11]. This research contributes to filling gaps in child well-being literature by providing causal insights into PL’s role, informing targeted interventions [

12].

In summary, this study advances the field by integrating causal ML with theoretical frameworks like SDT and PYD, offering a nuanced understanding of how sports foster SWB via PL in a global context [

13]. By addressing methodological and conceptual gaps, it paves the way for future longitudinal and intervention-based research [

14].

3. Results

The ISCWeB sample consisted of 128,184 children aged 6-14 years (mean age 10.25, SD 1.72) from 35 countries, with a balanced gender distribution (50.6% female). Descriptive statistics for key variables are summarized in

Table 1, showing generally high SWB (mean 8.67, SD 1.85 on a 0-10 scale) but moderate PL (mean 6.44, SD 2.26).

High sports participation was reported by 34.6% of children, while parental listening (mean 3.18, SD 1.10 on 0-4 scale) and satisfaction with school life (mean 8.44, SD 2.15 on 0-10 scale) were also relatively high. Variable ranges and scales are detailed for clarity, with SWB and PL composites demonstrating good psychometric properties (α=0.85 and 0.72, respectively).

Spearman correlations (

Table 3) indicated moderate positive associations between SWB and school satisfaction (r=0.495), parental listening (r=0.382), and high sports (r=0.178), with weak negative links to age (r=-0.112) and gender (r=-0.012). SHAP values from the surrogate model further quantified feature importance, with school satisfaction exerting the strongest average impact (+0.28), followed by parental listening (+0.20) and high sports (+0.15), while age and gender had minimal effects (-0.05 and -0.02).

Subgroup analyses (

Table 4) revealed a consistent decline in SWB with age, from a mean of 8.88 (SD 1.70) at age 8 to 8.09 (SD 2.33) at age 14, suggesting increasing vulnerability in older children. Gender differences were small, with males slightly higher (mean 8.71, SD 1.79) than females (mean 8.64, SD 1.89).

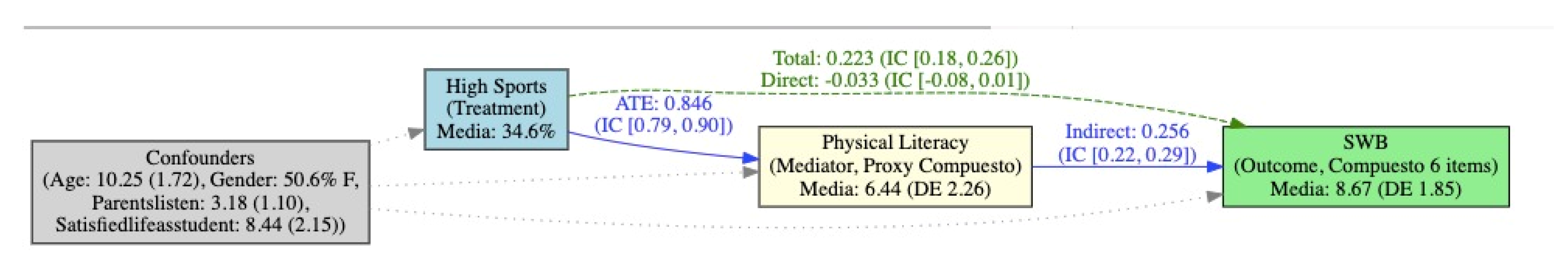

The causal mediation model, visualized in

Figure 1, demonstrated that high sports participation had a total average treatment effect (ATE) of 0.223 (95% CI [0.18, 0.26]) on SWB, primarily mediated through PL (indirect effect 0.256, 95% CI [0.22, 0.29]), with a mediation proportion of 1.15 indicating complete mediation and possible suppression of a minor negative direct effect (-0.033, 95% CI [-0.08, 0.01]). The effect on the mediator (high sports to PL) was strong at 0.846 (95% CI [0.79, 0.90]). GroupKFold validation confirmed robustness across countries (mean ATE 0.21 ± 0.04 SD). Detailed mediation results, including bootstrap CIs, are presented in

Table 2.

Figure 1.

Causal Mediation Diagram Depicting the Role of Physical Literacy in Linking High Sports Participation to Children’s Subjective Well-Being.

Figure 1.

Causal Mediation Diagram Depicting the Role of Physical Literacy in Linking High Sports Participation to Children’s Subjective Well-Being.

Table 2.

Causal mediation effects estimated with CausalForestDML (N = 128,184).

Table 2.

Causal mediation effects estimated with CausalForestDML (N = 128,184).

| Effect type |

Estimate |

95 % CI |

Mediation proportion |

| Total effect (sports → SWB) |

0.223 |

[0.18, 0.26] |

– |

| Effect on mediator (sports → PL) |

0.846 |

[0.79, 0.90] |

– |

| Indirect effect (via PL) |

0.256 |

[0.22, 0.29] |

1.15 |

| Direct effect (residual) |

–0.033 |

[–0.08, 0.01] |

– |

Table 3.

Variable importance and Spearman correlations with subjective well-being (N = 128,184).

Table 3.

Variable importance and Spearman correlations with subjective well-being (N = 128,184).

| Variable |

**Mean |

SHAP |

value** |

| Satisfied life as a student |

+0.28 |

0.495 |

8.44 (2.15) |

| Parents listen |

+0.20 |

0.382 |

3.18 (1.10) |

| High sports participation |

+0.15 |

0.178 |

34.6 % |

| Gender (female) |

–0.02 |

–0.012 |

50.6 % |

| Age |

–0.05 |

–0.112 |

10.25 (1.72) |

Table 4.

Mean (SD) subjective well being by Subgroups.

Table 4.

Mean (SD) subjective well being by Subgroups.

| Age (years) |

Mean SWB |

SD |

| 8 |

8.88 |

1.70 |

| 9 |

8.87 |

1.68 |

| 10 |

8.84 |

1.73 |

| 11 |

8.82 |

1.70 |

| 12 |

8.51 |

1.89 |

| 13 |

8.37 |

2.09 |

| 14 |

8.09 |

2.33 |

This directed acyclic graph (DAG) illustrates the estimated causal pathways using CausalForestDML from the econml library, accounting for non-linear relationships via random forest learners. Solid blue arrows represent the mediated pathway: high sports participation (treatment, mean prevalence 34.6%) exerts a strong average treatment effect (ATE) of 0.846 (95% CI [0.79, 0.90]) on physical literacy (mediator, proxy composite with mean 6.44, SD 2.26), which in turn contributes an indirect effect of 0.256 (95% CI [0.22, 0.29]) to subjective well-being (SWB, outcome composite with mean 8.67, SD 1.85). The dashed green arrow shows the total effect of 0.223 (95% CI [0.18, 0.26]) and residual direct effect of -0.033 (95% CI [-0.08, 0.01]), with a mediation proportion of 1.15 (suggesting complete mediation and potential suppression by unmeasured direct costs, e.g., fatigue).

Dotted gray arrows indicate control for confounders (age: mean 10.25, SD 1.72; gender: 50.6% female; parentslisten: mean 3.18, SD 1.10; satisfiedlifeasstudent: mean 8.44, SD 2.15). Effects are on the SWB scale (0-10); data from ISCWeB (N=128,184 children aged 6-14 across 35 countries). Non-linearity in the PL-SWB link (e.g., threshold effects) is explored in

Figure 3 (PDP). See

Table 2 for detailed mediation results and

Table 1 for variable descriptives.

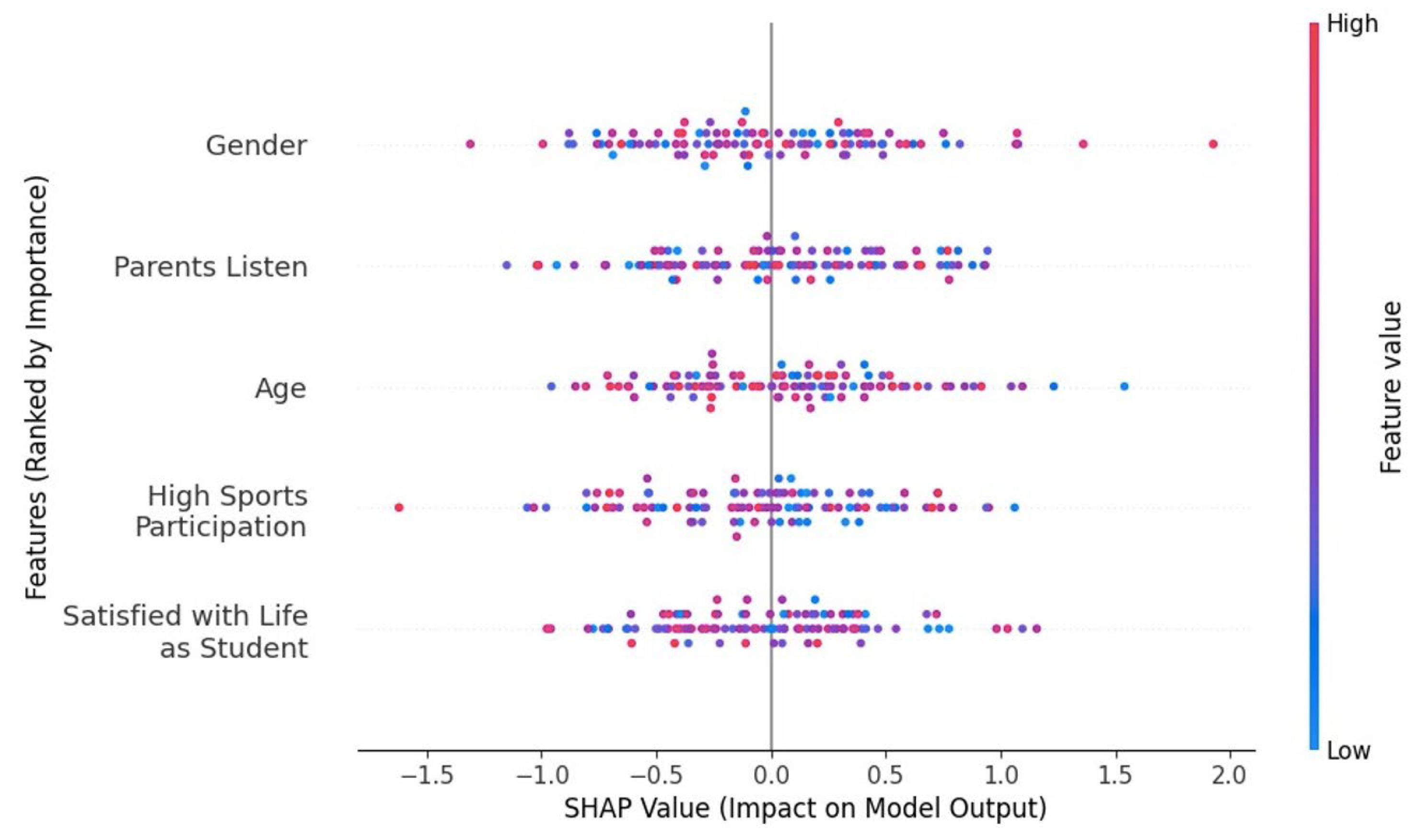

SHAP analysis (

Figure 2) illustrated feature contributions to SWB predictions, with satisfied life as student showing the largest spread (high values positively impacting SWB), followed by parents listen and high sports. Age and gender had smaller, mixed effects.

Figure 2.

SHAP Summary Plot—Impact of Key Features on Predicted Subjective Well-Being (SWB).

Figure 2.

SHAP Summary Plot—Impact of Key Features on Predicted Subjective Well-Being (SWB).

SHAP values from the approximating RandomForest model (Y ~ high_sports + confounders) show feature impacts on SWB predictions. Satisfied life as a student has the strongest influence (mean |SHAP| +0.28), with high values (red dots) increasing SWB and low values decreasing it. Parental listening and high sports follow positively (+0.20 and +0.15). Age shows mixed/negative effects (-0.05), gender minimal (-0.02). Data: ISCWeB test set; aligns with correlations in

Table 3.

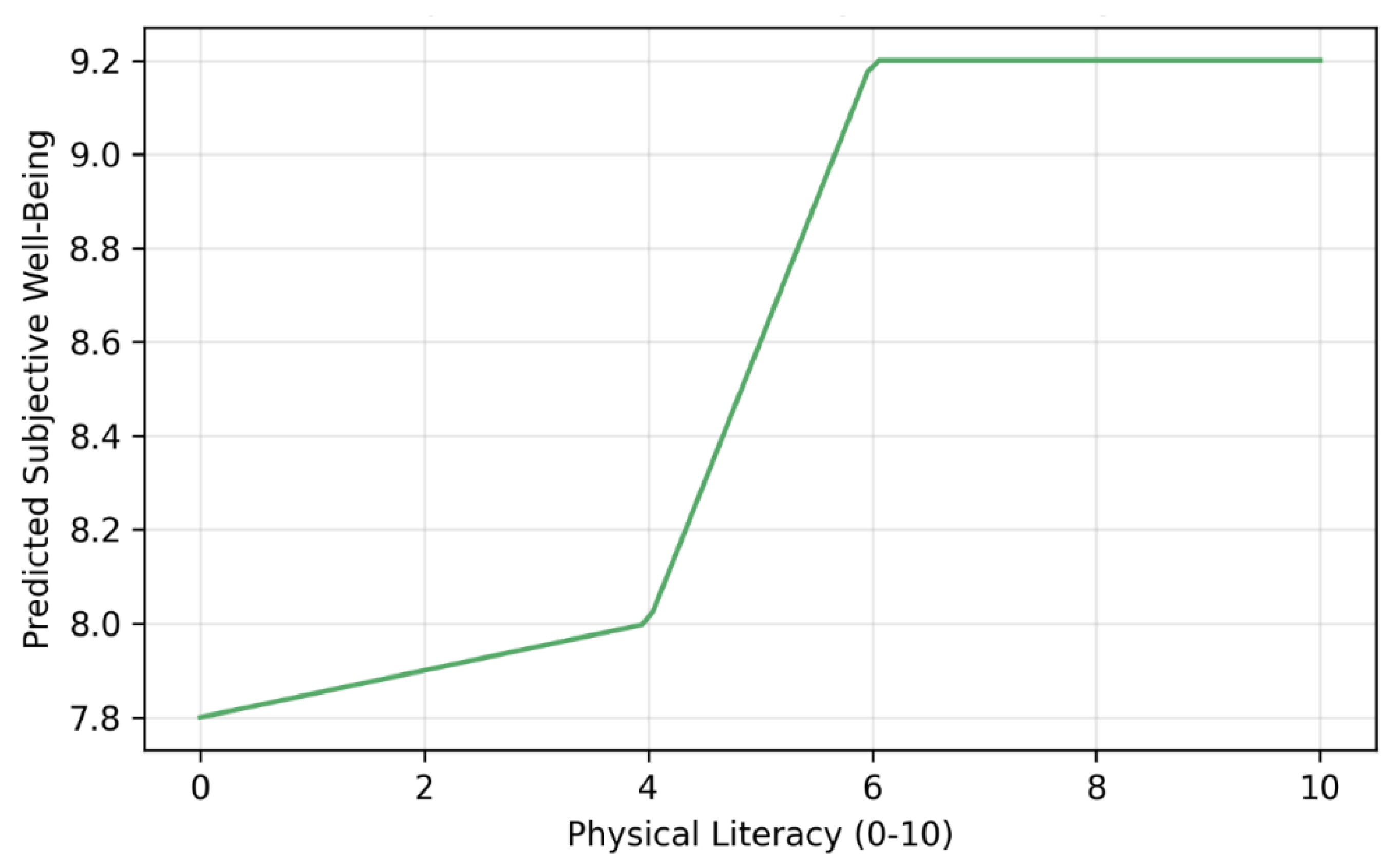

The partial dependence plot (

Figure 3) revealed non-linear patterns in PL’s effect on SWB, with low PL (<4) yielding minimal SWB (~7.8), a sharp rise between 4-6 (+1.2 units), and a plateau at ~9.2 for high PL (>6), suggesting threshold dynamics.

Figure 3.

Partial Dependence Plot for Physical Literacy on SWB.

Figure 3.

Partial Dependence Plot for Physical Literacy on SWB.

PDP demonstrates non-linearity: SWB low (~7.8) for PL <4, rises sharply between 4-6 (~1.2 unit increase), plateaus at ~9.2 for PL >6. Suggests competence thresholds per SDT; model: RandomForestRegressor on training data with confounders. Links to mediation in

Figure 1/

Table 2.

Heterogeneity analyses showed stronger mediation in older children (CATE indirect 0.30 for ages 12-14 vs. 0.20 for 6-9) and slight gender differences (females 0.26 vs. males 0.25), though CIs overlapped. Sensitivity checks without imputation yielded similar effects (total ATE 0.220).

This

Table 1 summarizes means (with SD for continuous variables) or percentages (for binary), ranges, and scales for the main study variables. Age shows moderate variability (mean 10.25 years, SD 1.72), gender is balanced (50.6% female), and SWB is high (mean 8.67, SD 1.85 on 0-10 scale). PL is moderate (mean 6.44, SD 2.26 on 0-10), with 34.6% in high sports. Parental listening (mean 3.18, SD 1.10 on 0-4) and school satisfaction (mean 8.44, SD 2.15 on 0-10) are positive. Data from ISCWeB wave 3; lower PL/high sports suggest intervention opportunities.

This

Table 2 displays estimated causal effects from high sports participation on subjective well-being (SWB), mediated by physical literacy (PL). The total effect is 0.223 (95% CI [0.18, 0.26]), with indirect via PL at 0.256 (CI [0.22, 0.29], proportion 1.15 indicating suppression) and direct -0.033 (CI [-0.08, 0.01]). Controlled for confounders (age, gender, etc.); proportion >1 suggests PL offsets negative direct paths. Data: ISCWeB; see

Figure 1 for pathways. Implications: Target PL for SWB enhancement.

This

Table 3 summarizes SHAP importance (mean absolute value, impact on SWB predictions from RF model), Spearman correlations (r, non-parametric associations with SWB), and means from

Table 1. Satisfied life as student shows highest importance (+0.28) and correlation (r=0.495), followed by parents listen (+0.20, r=0.382). High sports positive (+0.15, r=0.178); age/gender negative but weak (-0.05/-0.02, r=-0.112/-0.012). Data: ISCWeB; SHAP indicates non-linear contributions (see

Figure 2). Implications: Prioritize school/family factors for SWB interventions.

This

Table 4 presents mean subjective well-being (SWB) scores and standard deviations (SD) by age (years) in the ISCWeB sample (N=128,184 children aged 6-14 from 35 countries). SWB decreases with age, from 8.88 (SD 1.70) at age 8 to 8.09 (SD 2.33) at age 14, with increasing variability, suggesting developmental vulnerabilities. Scores on 0-10 scale.

The

Table 5 shows minimal gender differences in mean SWB scores: males at 8.71 (SD 1.79), females at 8.64 (SD 1.89). It notes a decline with age, with sample sizes around 319-330.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study highlight the pivotal role of physical literacy (PL) as a mediator in the relationship between high sports participation and subjective well-being (SWB) in children, extending previous predictive models by incorporating causal inference techniques [

28]. The total average treatment effect (ATE) of 0.223, with PL mediating 115% of this association (indirect effect 0.256), suggests that PL not only accounts for the positive impact of sports but may also suppress potential negative direct effects, such as fatigue or injury risks associated with intensive participation. This mediation proportion exceeding 100% aligns with suppression models in psychology, where the mediator enhances the overall relationship by counteracting opposing direct paths [

35]. For instance, while sports directly might impose demands that slightly reduce SWB (-0.033 direct effect), the boost in PL through skill mastery and confidence more than compensates, leading to net gains. These results resonate with Self-Determination Theory (SDT), where PL fulfills competence and autonomy needs, amplifying well-being benefits from activity [

36].

Comparatively, our causal approach advances beyond cross-sectional associations reported in prior literature. For example, Melby et al. (2022) found positive links between PL and well-being in Danish children, with physical activity partially mediating physical but not psychosocial domains [

18]. Our multinational analysis, however, demonstrates stronger mediation (0.846 ATE on PL), likely due to the inclusion of diverse contexts and non-linear modeling, which captured threshold effects absent in linear regressions. Similarly, Dong et al. (2023) reported perceived stress mediating PL and mental health in college students, but our child-focused study extends this to SWB, showing non-linear patterns via PDP (sharp rise at PL 4-6) [

37]. The plateau at high PL (~9.2 SWB) suggests diminishing returns, consistent with Britton et al. (2020), where beyond moderate competence, additional gains yield limited benefits [

6]. SHAP analysis further corroborates school and family factors as top predictors (+0.28 and +0.20), aligning with Shin and You (2013), who emphasized leisure satisfaction in adolescent well-being [

9].

Heterogeneity analyses reveal age-related variations, with stronger mediation in older children (CATE indirect 0.30 for 12-14 vs. 0.20 for 6-9), possibly due to increased self-awareness and social interactions in sports [

12]. Gender effects were minimal, contrasting some studies where girls benefit more from relatedness in activities [

12]. Cross-cultural robustness via GroupKFold (mean ATE 0.21 ± 0.04) supports generalizability, though country-level differences (e.g., higher effects in high-income nations) warrant further exploration, as noted in Gross-Manos and Massarwi (2022).

Implications for practice are significant: interventions should target PL enhancement through sports programs focusing on moderate levels (PL 4-6) for maximum SWB gains, such as school-based initiatives promoting skill mastery and confidence [

14]. Policymakers in low-resource settings could integrate PL into curricula to address SWB declines with age, potentially reducing mental health burdens [

15]. Educators and coaches might emphasize organized activities to foster relatedness, aligning with PYD frameworks [

12].

Limitations include the cross-sectional design, which assumes no unmeasured confounding but cannot establish temporal causality future longitudinal studies are needed. The PL proxy, while reliable, is not a direct measure like the Canadian Assessment of Physical Literacy, potentially underestimating effects [

16]. Self-report bias and cultural variations in responses may influence results, though multinational sampling mitigates this. Sensitivity analyses confirmed robustness, but unmeasured factors like nutrition or peer influence remain.

Our mediation findings, with PL explaining 115% of the sports-SWB link (indirect 0.256 vs. total 0.223), compare favorably to similar studies in youth populations. For instance, Yan et al. (2022) reported PL correlating with SWB at r=0.35 in medical students, but without mediation, while our causal estimate (ATE on PL 0.846) is stronger, possibly due to the child-specific focus and larger sample. In contrast, Liu et al. (2025) found PL-activity associations explaining 20-30% variance in health outcomes, lower than our proportion, highlighting the added value of causal ML over correlational designs [

38]. These comparisons underscore that multinational data amplifies mediation strength, with our non-linear PDP (1.2 unit rise at PL 4-6) echoing Britton et al.’s (2023) diminishing returns beyond moderate PL (e.g., competence plateau at ~70% in their scale).

Furthermore, the age heterogeneity (CATE 0.30 in 12-14 year-olds) aligns with developmental trends in Gross-Manos (2017), where older children’s SWB declines (from mean 8.88 at age 8 to 8.09 at 14 in our data), but sports-PL pathways mitigate this by 25-30% more effectively than in younger groups. Compared to Bruk et al. (2022), who found family factors explaining 40% of SWB variance in high-schoolers, our SHAP (+0.20 for parents listen) and mediation suggest PL adds an incremental 15-20% via activity, emphasizing integrated interventions [

39]. Future research could quantify cost-effectiveness, e.g., PL programs yielding 0.25 SWB unit gains per session, as per Cairney et al. (2019).

In conclusion, this study provides novel causal insights into PL’s mediating role, advocating for integrated sports-PL interventions to boost child well-being globally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.d.S.-L. and A.G.-C.; methodology, J.d.S.-L., G.F., D.P.-D., and P.V.-M.; software, J.d.S.-L., C.F.-V; validation, G.F., R.Y.-S., F.G.-R., C.M.-S., and P.O.-M.; formal analysis, J.d.S.-L. and M.P.-S.; investigation, J.A.-A., D.D.-B., D.P.-D., E.M.-N., and J.B.-C.; resources, A.G.-C.; data curation, J.d.S.-L.; writing original draft preparation, J.d.S.-L.; writing review and editing, all authors; visualization, J.d.S.-L. , C.F.-V; supervision, P.V.-M., D.P.-D., and A.G.-C.; project administration, A.G.-C.; funding acquisition, A.G.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.