1. Introduction

South African ‘air-dried’ meat products include biltong (similar to beef jerky) and droëwors (sausage sticks). Biltong is usually made from lean strips of beef marinaded in traditional spices (coriander, black pepper), salt, and vinegar dried at ambient temperature (75°F) and humidity (55% RH). Droëwors is made from residual beef and fat trimmings leftover from processing biltong, similarly marinaded, ground in a meat grinder, stuffed into casings, and dried under similar conditions as biltong to produce dried beef sticks.

In the United States, beef jerky processing is the standard for dried, shelf-stable beef product produced under United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS) compliance guidelines. Many processors cite USDA-FSIS lethality performance standards (Appendix A) for meat and poultry products for their temperature targets and hold times during processing (i.e., 145 °F for 4 min) which state that relative humidity (RH) must be 90% or higher for at least 25% of the total cooking time, or 1 hour, whichever is longest [

1]. Processors who do not adhere strictly to the USDA-FSIS Appendix A guidelines (i.e., humidity, cooking temperature) for the manufacture of dried beef or poultry jerky must provide validation that their process provides adequate pathogen reduction to ensure the product is safe and wholesome for human consumption. Validation can be done with an outside lab (or reference to acceptable peer-reviewed published literature) to validate that their process is sufficient in satisfying USDA-FSIS food safety requirements. If these parameters are not met, as with biltong processing, a microbial validation study must be provided to demonstrate that sufficient bacterial reductions of a ‘pathogen of concern’ (i.e.,

Salmonella) can be achieved during processing. Since biltong and droëwors processes are significantly different than beef jerky, USDA-FSIS provided 2 alternative processes by which processors could manufacture and sell these products [

2,

3]:

- i.

Test every lot of edible ingredients for Salmonella prior to use (must test negative) and use a process that is validated to provide ≥ 2-log reduction of a pathogen of concern (i.e., Salmonella), or

- i.

ii. Use a process that is validated to give ≥ 5-log reduction of a pathogen of concern (Salmonella).

Food processes designed to inhibit or reduce foodborne pathogens often require verification of the inhibitory capacity by using ‘challenge organisms’ artificially introduced into the food to determine the effect of the process on those pathogenic microorganisms. In discussions with USDA-FSIS on what they require in microbial validation studies, one of the required parameters was the use of ‘acid-adapted challenge cultures’ otherwise USDA-FSIS may not consider the process properly validated [

2,

4].

Acid tolerance was first recognized by Foster [

5,

6] and became more concerning as a food safety issue when it was recognized that certain organisms can become tolerant of acidic conditions [

7,

8]. This was significant in lieu of pathogens tolerating and surviving acidic conditions in the animal rumen and subsequently tolerating acidic rinse treatments on animal carcasses meant to eliminate them [

9]. Equally disconcerting were pathogens that may tolerate acidic-processed foods [

10,

11]. This concept was further developed into the methodology of inoculated food studies whereby challenge cultures would be conditioned to tolerate acidic conditions (i.e., acid-adapted). Growing pathogens in the presence of 1% glucose lowers the pH, and the resulting culture would be considered acid-adapted [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Alternative approaches were to acidify a culture post-growth using inorganic or organic acids [

6,

16]. Acid adaptation was listed in the National Advisory Committee for the Microbial Criteria for Food (NACMCF) ‘white paper’ on recommended parameters for inoculated challenge study protocols [

17]. They believed that acid-adapting pathogenic cultures intended for product inoculation would harden the organisms against sensitivity to acidic conditions they would encounter during processing. This would ensure that the process needs to be sufficiently robust if it were to demonstrate a significant reduction of the challenge cultures. This likely developed from studies during the 1990’s to reduce

E. coli O157:H7 and

Salmonella serovars on beef carcasses that resulted in foodborne illness from contaminated ground beef by treatments with various acidic antimicrobials [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Acid-adapting challenge cultures for use in validation studies would harden the cultures so that they wouldn’t easily succumb to acidic treatments. This was subsequently adopted by USDA-FSIS as a general recommendation for the preparation of pathogen challenge cultures in validation experiments involving acidic treatments and was requested by them when discussing biltong and droëwors processing.

USDA-FSIS has often relied on peer-reviewed published literature to affect policy on the strength of scientific data that could influence its stance on issues, such as acid-adaptation of challenge cultures. However, there have been a number of publications demonstrating the reverse effect on the use of acid-adapted cultures as had originally been proposed [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. The objective of this study was to determine whether acid-adapted treatment hardens or sensitizes

Salmonella challenge organisms to processing conditions during manufacture of biltong and droëwors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Bacterial cultures were grown in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB, BD Bacto, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) in 9-mL tubes and incubated at 37°C. Fresh overnight cultures (10-20 ml) were prepared for storage by centrifugation (6,000xg, 5°C). Cell pellets were resuspended in 2–5 mL of sterile TSB containing 15% glycerol and 1% trehalose, and then aliquoted to several glass vials and stored in cryoboxes in an ultra-low freezer (−80°C). Frozen stocks were revived by transferring 100 µL of the thawed cell suspension into 9 mL of TSB, incubating overnight at 37°C, and sub-culturing before use. Microbial enumeration on other media was always compared to counts obtained on Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA, BD Bacto; 1.5% agar), plated in duplicate.

Salmonella serovars used in this study included:

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Thompson 120 (chicken isolate),

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Heidelberg F5038BG1 (ham isolate),

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Hadar MF60404 (turkey isolate),

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Enteritidis H3527 (phage type 13a, clinical isolate), and

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium H3380 (DT 104 clinical isolate). These are well-characterized strains that have been used in numerous research publications involving antimicrobial interventions against

Salmonella spp [

2,

4,

29,

30,

31,

32]. These

Salmonella serovars were previously shown to be resistant to spectinomycin (5 ug/mL), clindamycin (5 ug/mL), and novobiocin (50 ug/mL) [

4] and were added to enumerative and selective media to further prevent background contamination. The individual and combined levels of antibiotics did not affect enumeration when added to plating or selective media.

Salmonella serovar I 4, 12:i:- [

5] was also provided by USDA-FSIS as a test culture that might prove difficult to demonstrate reduction by the air-dried biltong process as it was isolated from dried beef. This serovar served as our first example of comparing acid-adapted and non-adapted cultures.

Acid adaptation of the

Salmonella cultures was carried out according to Wilde et al. [

15] in which they were inoculated in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose [

14]. Cultures were maintained individually, harvested by centrifugation, and cell pellets were resuspended with 0.1% buffered peptone water (BPW, BD Difco) and held refrigerated until use (5 °C). For a mixed serovar inoculum, the individual resuspended cultures were mixed in equal proportions. The various processing tests in this study were performed using acid-adapted

Salmonella cultures in TSA containing 1% glucose as described above in comparison with non-acid-adapted cultures. USDA-FSIS ‘highly recommends’ the use of acid-adapted cultures when such inoculum strains would be used in processes involving acidic treatments to ensure that they are not easily overcome by acidic processing conditions. Non-acid-adapted cultures were grown in TSB with 0% glucose. In some experiments, we also examined non-acid-adapted cultures whereby TSB was supplemented with 1% glucose but buffered with 200 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) in order to match the metabolic availability of nutrients while buffering the media to prevent acidification during growth.

2.2. Evaluation of Salmonella-Selective Agar Media for Enumeration of Salmonella from Droëwors Processing

We examined and compared four selective agar media in preparation for the enumeration of non-acid-adapted

Salmonella serovars during droëwors processing. These same media previously demonstrated significant differences in enumeration after various process stress situations with

Salmonella encountered during biltong processing [

4]. Biltong processing has an accumulation of antimicrobial factors (vinegar, salt, dessication) and bacteria at the beef surface resulting from a 60-65% moisture loss during processing. This results in stressful conditions on surface bacteria that causes a reduction of injured/stressed cells when plated on certain inhibitory selective media [

4]. In droëwors, the beef/fat, inoculum bacteria, and ingredients are ground up and evenly dispersed during processing and we were interested to see if similar stresses would result in similar media-influenced lethality during quantification using various

Salmonella-selective media. The selective media included TSA (non-selective), Selenite Cystine Agar (SCA), Hektoen Enteric (HE), and Xylose Lysine Desoxycholate (XLD) agars. All four of these agar media contained three antibiotics: spectinomycin (5 ug/mL), clindamycin (5 ug/mL), and novobiocin (50 ug/mL) to which the

Salmonella serovars were resistant.

2.3. Air-Dried Biltong Beef Process

The biltong process was performed exactly as described previously [

2,

33,

34] (

Figure 1). Briefly, beef pieces were placed in a chilled stainless steel tumbler chamber, harvested/mixed challenge cultures were added and tumbled for 10 min in order to distribute the inoculum. Then the marinade of spices (corriander, black pepper), salt, and vinegar were added and tumbled again for 30 min. The beef pieces were then hung in a drying oven set at 75°F and 55% relative humidity (RH). Samples were retrieved periodicially for microbial enumeration at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 days.

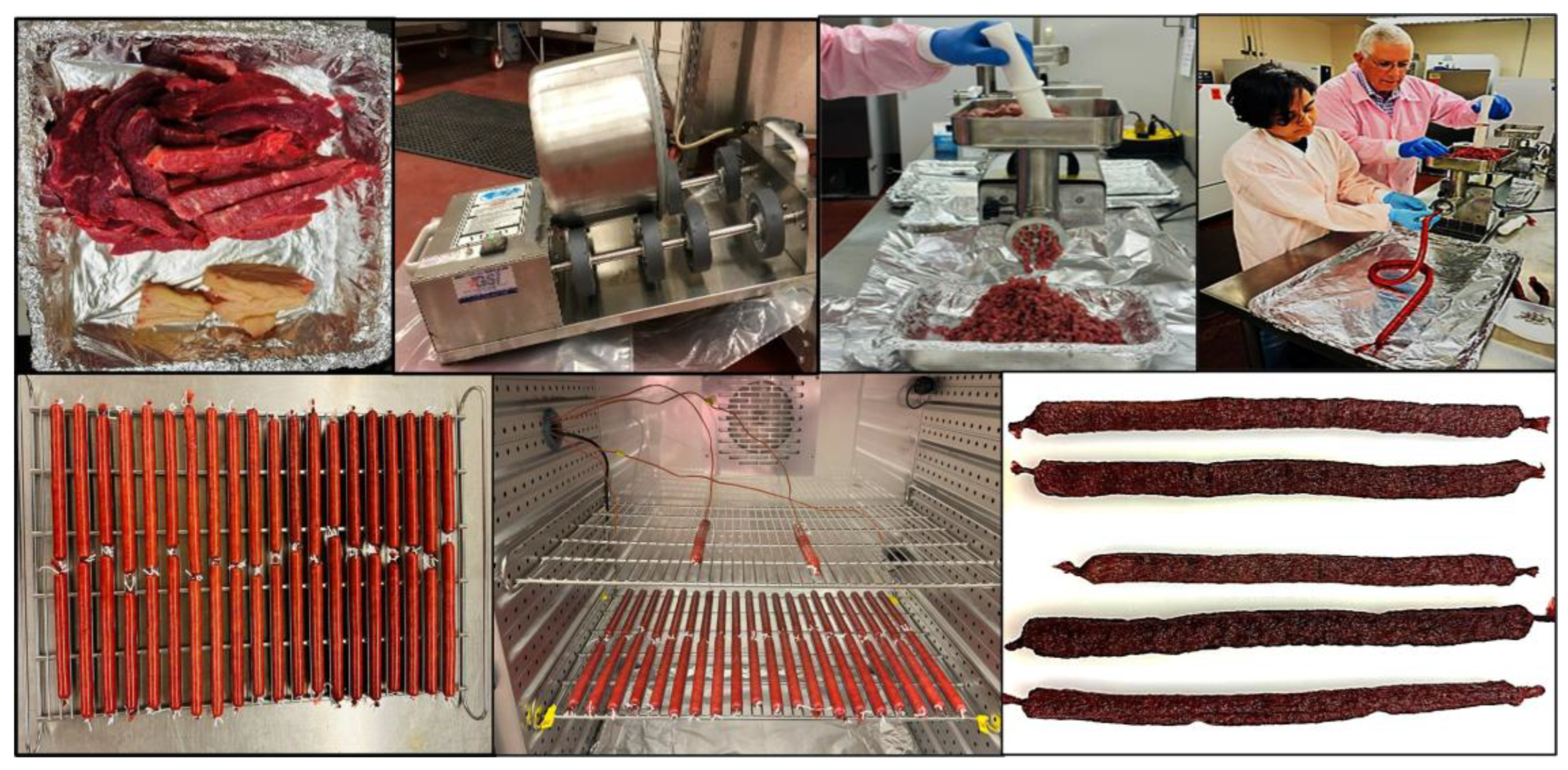

2.4. Air-Dried Droëwors Beef Process

The droëwors process was similar to the biltong process, except that fat (5%) was added to the beef, then inoculum was added and tumbled, followed by the marinade mixture of spices, salt, and vinegar and tumbled again for 30 min (

Figure 2). The inoculated/marinaded mixture of beef/fat was then ground using an LEM meat grinder (8 mm grind plate) and then again through a 2nd grind (10 mm grind plate) which also had a 12 mm stuffing horn to extrude the ground beef mixture into 17 mm collagen casings. The stuffed casings were tied with twine at approximately 6-7 inches and held in the refrigerator before being placed in the humidity oven.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Each experimental trial was performed in duplicate and each sampling period within a trial involved triplicate samples. The data for each experiment was presented as the mean of duplicate trials (2 trials x 3 replicates/sampling period/trial; n=6). All data were presented as the mean with standard deviation of the mean represented by error bars. Statistical analysis was done using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), or for timed series using one-way repeated measures ANOVA, using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences (p < 0.05). Data treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05); treatments with the same letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

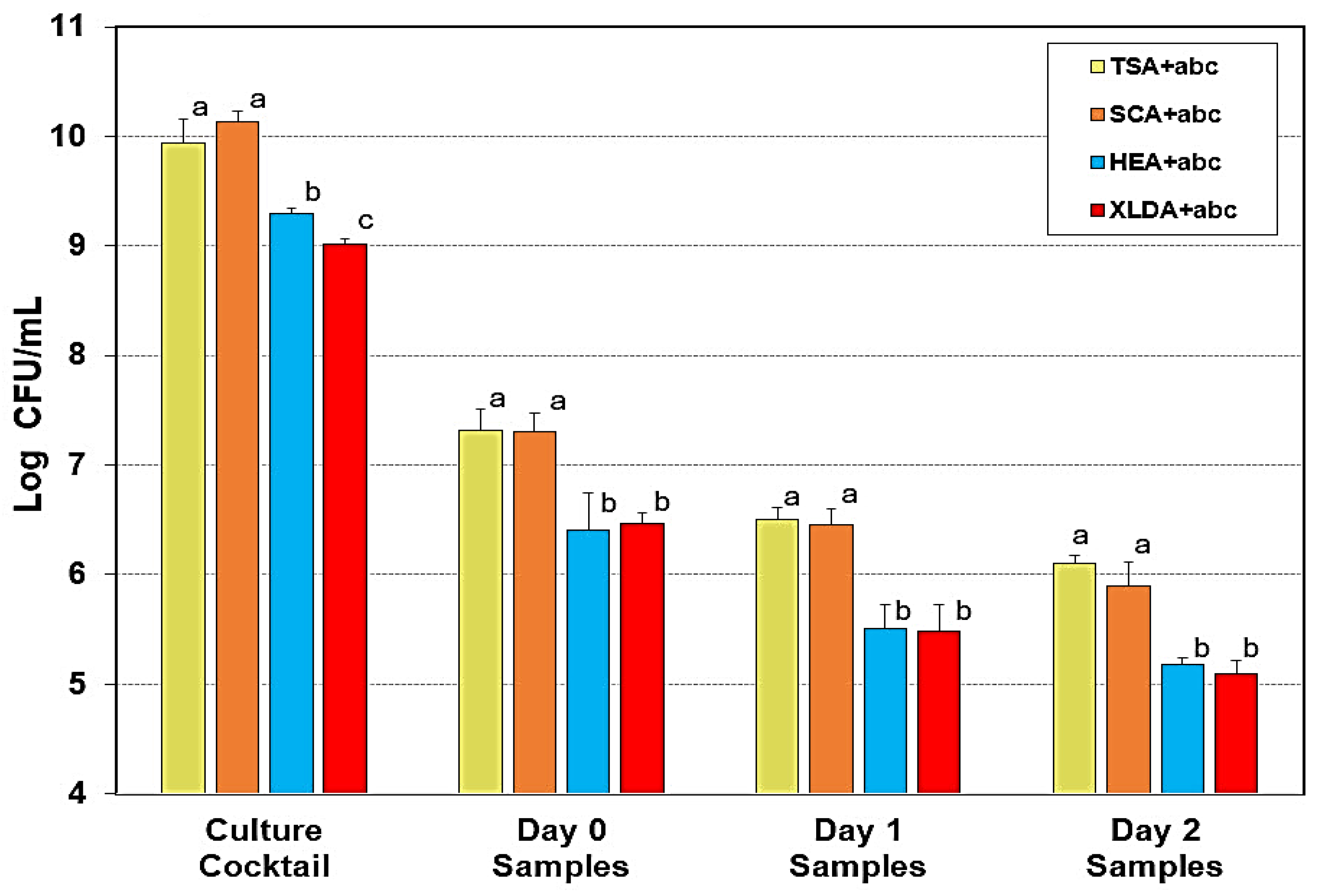

3.1. Comparison of Selective Media for Quantitative Enumeration of Salmonella Challenge Cultures After Droëwors Processing

In a prior study with biltong, background meat contamination was experienced that came up among the inoculated

Salmonella challenge organisms during plating on TSA + antibiotics, forcing us to seek a more selective media that allowed quantitative enumeration of

Salmonella [

4]. Several selective media (XLD, HE) were examined but these media have a history of inhibiting stressed, injured cells [

4,

35,

36,

37,

38]. We included an agar made with selenite cystine broth that is often used as an enrichment broth for

Salmonella and referred to it as selenite cystine agar (SCA). Our data confirmed that even with droëwors, SCA media was equivalent to TSA in enumeration of

Salmonella during droëwors processing compared to XLD or HE selective agars (

Figure 3).

The data shows significant reductions of Salmonella when plated on XLD and HE media compared to TSA and SCA, indicating inhibition of stressed or injured cells by those media. We have not noticed any significant background contamination from our raw beef in recent trials as observed previously as it could have been a seasonal or processor-related issue as we source our beef from a local processor who obtains it through a broker who obtain their beef from different sources. Because of the consistency in recovery, we have continued to use SCA media with the Salmonella challenge organisms for our studies.

3.2. Biltong Processing: Comparison of Acid-Adapted and Non-adapted Salmonella Challenge Cultures

After having performed a variety of validations and characterizations of biltong processing [

2,

4,

33,

34,

35], we contemplated validating whether acid-adapted challenge cultures would be more tolerant to processes involving acid treatment as had been postulated. This was especially concerning as we were about to embark on a study with droëwors to achieving a 5-log reduction with a hardy inoculum would improve the overall safety of these products.

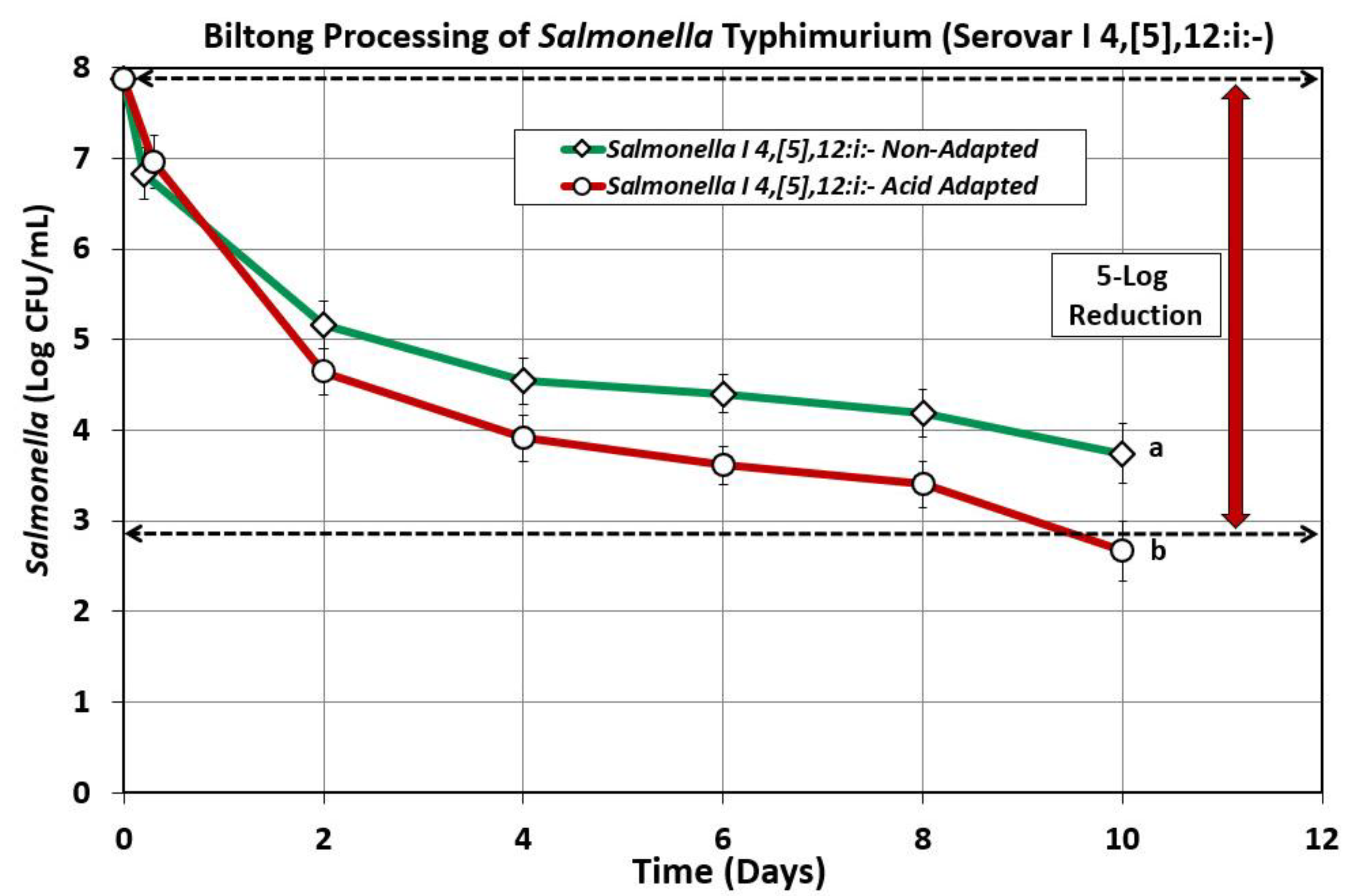

3.2.1. Salmonella enterica Typhimurium (serovar I 4,[5] 12:i:-)

Salmonella serovar I 4,[

5] 12:i:- [

36] was provided by USDA-FSIS as an isolate obtained from dried beef and it was questioned whether it’s desiccation resistance could serve as an ideal challenge organism for the biltong process. We examined the biltong process using both acid-adapted and non-acid-adapted culture preparations of

Salmonella I 4,[

5] 12:i:- (

Figure 4).

To our surprise, the acid-adapted

Salmonella Typhimurium serovar I, 4,[

5],12:i:- inoculum showed a greater log reduction (i.e., more sensitive) in the biltong process than the non-adapted culture. The requirement to use acid-adapted cultures was supposed to make it more difficult to achieve microbial reduction over non-adapted cultures because of the tolerance to acid that growth at low pH should have provided. The implication was that the non-adapted cultures present more resistance to the processing conditions than the acid-adapted cultures and questioned whether our mix of 5

Salmonella serovars would demonstrate the same distinction during processing.

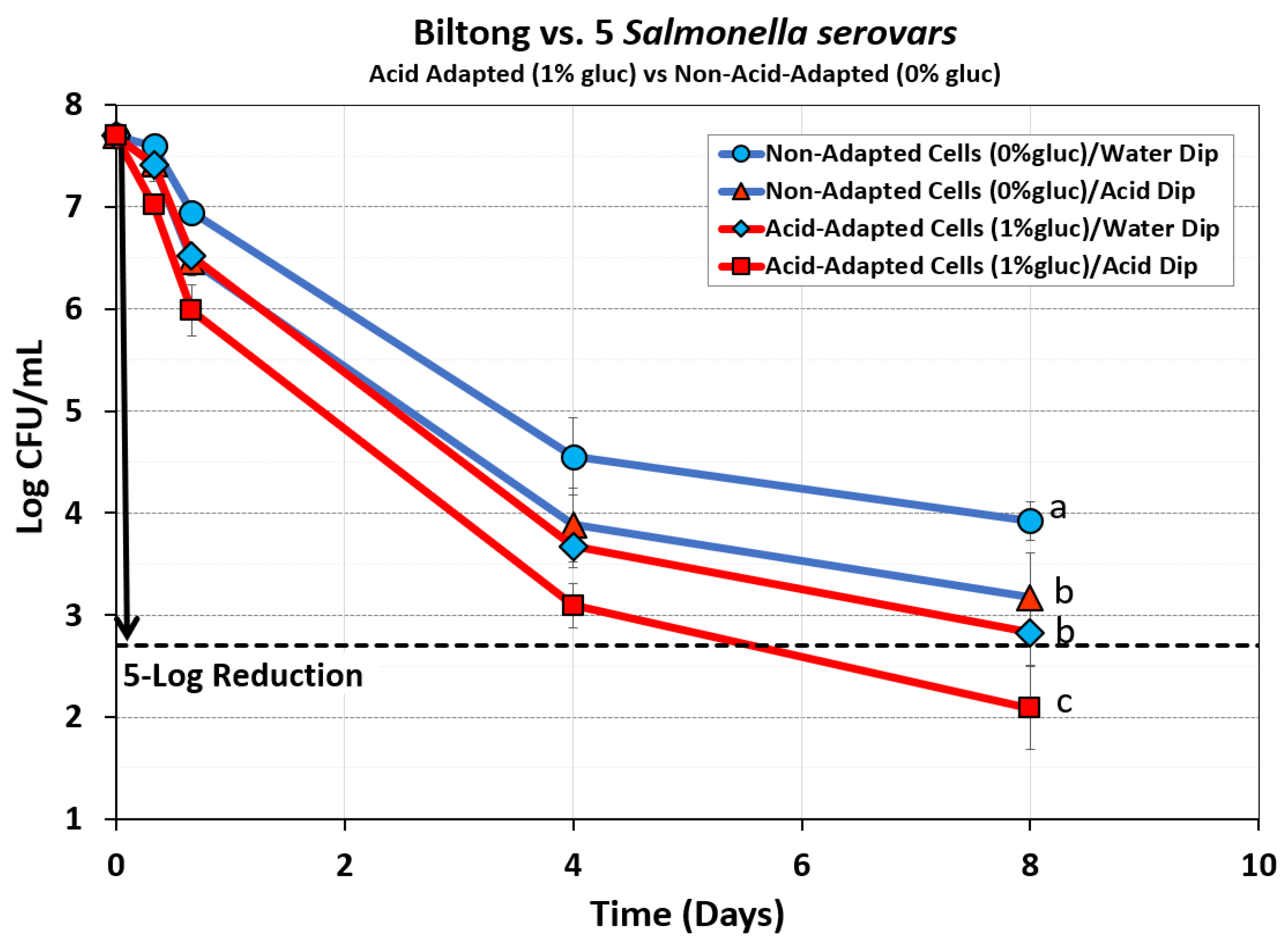

3.2.2. Mixture of Five Salmonella serovars: Acid-Adapted (1% glucose) vs Non-Adapted (0% Glucose)

This same comparison was then examined with the mix of five Salmonella serovars used in our prior biltong experiments and was intended for use in our upcoming study involving droëwors processing. As with

Salmonella Typhimurium (serovar I 4,[

5] 12:i:-;

Figure 4), the data showed that using a mixture of 5

Salmonella serovars, we again demonstrated a greater reduction during biltong processing with the acid-adapted cultures than non-adapted challenge cultures (

Figure 5). The data showed that for acid-adapted vs non-adapted cultures with the same dip treatment, the acid-adapted cultures provided the greater log reductions. Similarly, for trials with the same culture pre-treatments, acid-dip treatments gave significantly greater log reductions (

p < 0.05) than water dip treatments (

Figure 5).

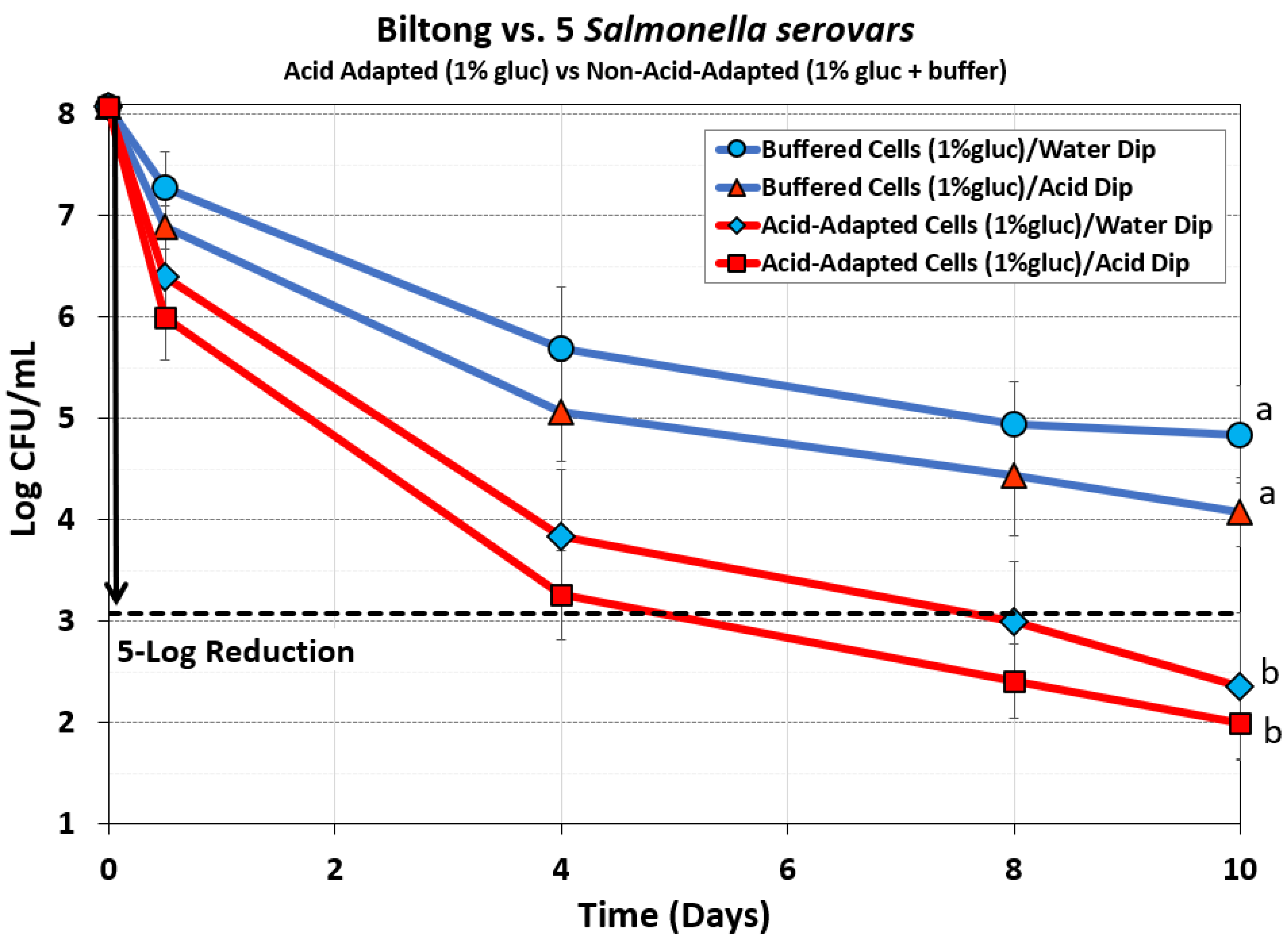

3.2.3. Mixture of 5 Salmonella serovars: Acid-Adapted (1% glucose) vs Non-Adapted (1% Glucose + Buffer)

The differences in the impact of acid-adapted vs. non-acid adapted cultures shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 was concerning, and it was thought that the additional 1% glucose added to the acid-adapted cultures would provide a significant nutritional difference compared to the cultures in media with only 0% glucose. We therefore examined whether a non-acid adapted culture treatment by adding 1% glucose along with buffer would provide a more balanced nutritional comparison, yet buffering to maintain media pH at near initial levels would be an improved variation of non-acid-adapted culture pre-treatments. However, this comparison provided an even greater disparity between the biltong processes using acid-adapted and non-adapted culture pre-treatments and further reduced the log reduction obtained by the non-adapted treatments even when extended to 10 days of processing (

Figure 6). As observed earlier, acid-dipped treatments gave greater reductions (not significantly different) compared to water-dipped treatments for both acid-adapted and non-adapted (buffered) culture treatments (

Figure 6).

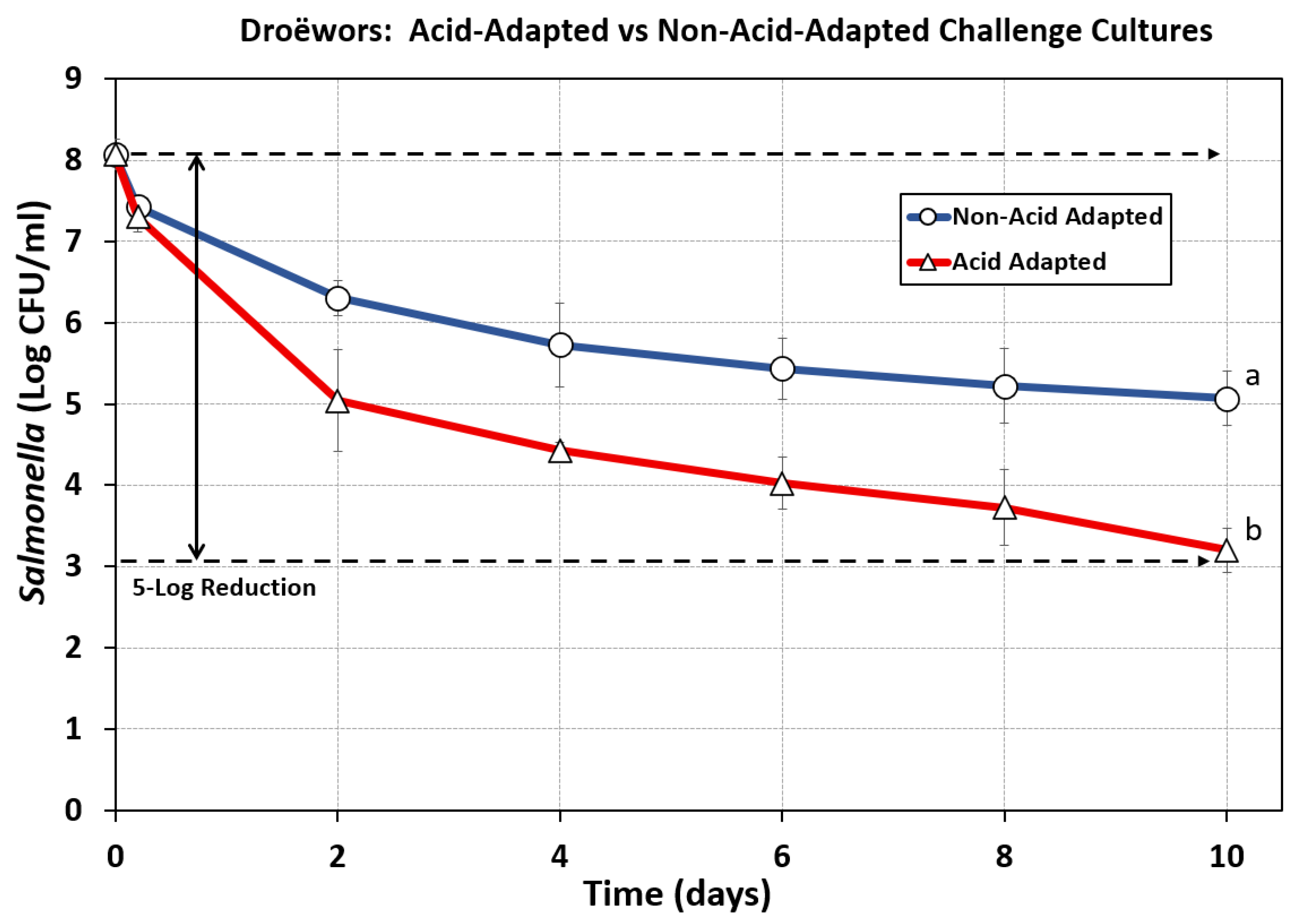

3.3. Droëwors Processing: Comparison of Acid-Adapted and Non-Adapted Salmonella Challenge Cultures

Droëwors is a sausage-like beef stick often made from leftover pieces of beef/fat trimmings from the biltong process that often complements products such as biltong. Acid-adapted and non-adapted Salmonella challenge cultures were also examined in droëwors processing to determine whether the effect would be different than that observed for biltong processing. The results would determine the manner in which we would approach culture preparation in lieu of upcoming droëwors processing experimentation.

Mixture of 5 Salmonella serovars: Comparison of Acid-Adapted (1% Glucose) vs Non-Acid-Adapted (0% Glucose) During Droëwors Processing.

Similar to what was observed with biltong processing, enumeration of

Salmonella recovered during droëwors processing again demonstrated that beef inoculated with acid-adapted cultures resulted in significantly greater reductions than that obtained with non-adapted cultures (

Figure 7). The use of non-acid adapted cultures of

Salmonella provided only a 3-log reduction during 10 days of desiccation in the humidity oven (55% RH, 75°F), far short of the 5-log reduction needed to achieve USDA-FSIS approval if not testing for presence of

Salmonella in every lot of edible ingredients used in droëwors manufacture.

4. Conclusions

The requirement by USDA-FSIS to use acid-adapted cultures during process validation experiments based on NACMCF recommendations may not apply to all dried beef processes involving acidic treatments. Understandably, the desire to use acid-tolerant cultures in validation studies that would not be overly sensitive to acidic treatment would be preferred in lieu of more acid-resistant strains that might naturally be present on meat/food products. Biltong and droëwors are complex processes, involving acidic treatment (vinegar in the marinade), salt, low water activity and desiccation in combination. The process of culture pre-treatment for acid adaptation may have induced stress and injury in the cultures that are impacted upon by the inhibitory conditions of the biltong/droëwors marinade and process (as evidenced by plate count differences on XLD agar), resulting in greater sensitivity by the challenge cultures to those processes as observed herein (

Figure 3; [

4]).

Various studies have demonstrated that acid-adaptation results in acid resistance of

Salmonella to various processes involving acidic treatments and have likely been the justification for regulatory preference on use of acid-adapted cultures [

37,

38]. However, we found just the opposite, that acid-adapted cultures performed as if they were more sensitive to processing conditions in both biltong and droëwors processing, giving larger reductions than non-adapted

Salmonella. This is similar to that found by Calicioglu et al. [

14,

39] comparing survival of non-adapted and acid-adapted

Salmonella cultures during storage of beef jerky, whether they were inoculated pre- or post-drying. It may be best to have a trial run with both culture treatments in a particular process to test which stratagem is better suited to the process. Although a 5-log reduction was not obtained using the non-adapted cultures, we have subsequently identified that including a natural plant extract (pyrolyzed extract of plant material) could easily achieve a 5-log reduction with both biltong and droëwors [

40].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M.; methodology, P.M., P.A., and C.K.; software, P.M.; validation, P.A., J.W., and C.K.; formal analysis, P.A., C.K., and J.W.; investigation, P.A., C.K., and J.W.; resources, P.M.; data curation, P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M., P.A.; writing—review and editing, P.A., C.K., and J.W.; visualization, P.M.; supervision, P.M., C.K., and P.A.; project administration, P.M.; funding acquisition, P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Food Safety and Defense grant (#2023-67017-40046) from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the OSU Gilliland/Advance Food Professorship in Microbial Food Safety (#21-57200), and the OSU Agricultural Experiment Station (#OKL03284).

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge discussions with Gary Moorcroft and Vorster Gauche on the topics of biltong and droëwors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- USDA-FSIS. FSIS compliance guideline for meat and poultry jerky produced by small and very small establishments. U.S. Food Safety and Inspection Service: Washington, D.C., 2014; pp 1-54.

- Karolenko, C.E.; Bhusal, A.; Nelson, J.L.; Muriana, P.M. Processing of biltong (dried beef) to achieve USDA-FSIS 5-log reduction of Salmonella without a heat lethality step. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 791.

- USDA-FSIS. FSIS Ready-to-Eat Fermented, Salt-Cured, and Dried Products Guideline. Availabe online: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media_file/documents/FSIS-GD-2023-0002.pdf (accessed on April 18, 2025).

- Karolenko, C.E.; Bhusal, A.; Gautam, D.; Muriana, P.M. Selenite cystine agar for enumeration of inoculated Salmonella serovars recovered from stressful conditions during antimicrobial validation studies. Microorganisms 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.W.; Hall, H.K. Inducible pH homeostasis and the acid tolerance response of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol 1991, 173, 5129-5135. [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.W.; Hall, H.K. Adaptive acidification tolerance response of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 771-778. [CrossRef]

- Gorden, J.; Small, P.L. Acid resistance in enteric bacteria. Infection and Immunity 1993, 61, 364-367. [CrossRef]

- Merrell, D.S.; Camilli, A. Acid tolerance of gastrointestinal pathogens. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2002, 5, 51-55. [CrossRef]

- Berry, E.D.; Cutter, C.N. Effects of acid adaptation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 on efficacy of acetic acid spray washes to decontaminate beef carcass tissue. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2000, 66, 1493-1498. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P.M.; Harrison, M.A. Resistance and adaptation to food antimicrobials, sanitizers, and other process controls. Food Technology-Champaign Then Chicago- 2002, 56, 69-78.

- Slabbert, R.S. Acid tolerance and organic acid susceptibility of selected food-borne pathogens. Interim : Interdisciplinary Journal 2013, 12, 42-50. [CrossRef]

- Samelis, J.; Ikeda, J.S.; Sofos, J.N. Evaluation of the pH-dependent, stationary-phase acid tolerance in Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella Typhimurium DT104 induced by culturing in media with 1% glucose: a comparative study with Escherichia coli O157:H7. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2003, 95, 563-575. [CrossRef]

- Fratamico, P.M. Tolerance to Stress and Ability of Acid-Adapted and Non–Acid-Adapted Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium DT104 To Invade and Survive in Mammalian Cells In Vitro. Journal of food protection 2003, 66, 1115-1125.

- Calicioglu, M.; Sofos, J.N.; Samelis, J.; Kendall, P.A.; Smith, G.C. Effect of acid adaptation on inactivation of Salmonella during drying and storage of beef jerky treated with marinades. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 89, 51-65. [CrossRef]

- Wilde, S.; Jørgensen, F.; Campbell, A.; Rowbury, R.; Humphrey, T. Growth of Salmonella enterica Serovar Enteritidis PT4 in media containing glucose results in enhanced RpoS-independent heat and acid tolerance but does not affect the ability to survive air-drying on surfaces. Food Microbiol. 2000, 17, 679-686. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.-H.; Deng, Y.; Beuchat, L.R. Behavior of Acid-Adapted and Unadapted Escherichia coli O157:H7 When Exposed to Reduced pH Achieved with Various Organic Acids. Journal of Food Protection 1999, 62, 451-455. [CrossRef]

- NACMCF. Parameters for determining inoculated pack/challenge study protocols (National Advisory Committee on the Microbiological Criteria for Foods). J. Food Prot. 2010, 73, 140-202. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.; Lucia, L.M.; Kemp, G.K.; Acuff, G.R. Reduction of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella Typhimurium on Beef Carcass Surfaces Using Acidified Sodium Chlorite. Journal of Food Protection 1999, 62, 580-584. [CrossRef]

- Cutter, C.N.; Siragusa, G.R. Efficacy of Organic Acids Against Escherichia coli O157:H7 Attached to Beef Carcass Tissue Using a Pilot Scale Model Carcass Washer1. Journal of Food Protection 1994, 57, 97-103. [CrossRef]

- Dickson, J.S.; Anderson, M.E. Microbiological Decontamination of Food Animal Carcasses by Washing and Sanitizing Systems: A Review. Journal of Food Protection 1992, 55, 133-140. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.; Lucia, L.M.; Goodson, K.J.; Savell, J.W.; Acuff, G.R. Comparison of Water Wash, Trimming, and Combined Hot Water and Lactic Acid Treatments for Reducing Bacteria of Fecal Origin on Beef Carcasses. Journal of Food Protection 1998, 61, 823-828. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Fernández, A.; Bernardo, A.; López, M. Acid adaptation sensitizes Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium to osmotic and oxidative stresses. JFSFQ 2010, 61, 148-152. [CrossRef]

- Leyer, G.J.; Johnson, E.A. Acid adaptation sensitizes Salmonella Typhimurium to hypochlorous acid. Appl Environ Microbiol 1997, 63, 461-467. [CrossRef]

- Lianou, A.; Nychas, G.E.; Koutsoumanis, K.P. Variability in the adaptive acid tolerance response phenotype of Salmonella enterica strains. Food Microbiol 2017, 62, 99-105. [CrossRef]

- Wesche, A.M.; Gurtler, J.B.; Marks, B.P.; Ryser, E.T. Stress, sublethal injury, resuscitation, and virulence of bacterial foodborne pathogens. J Food Prot 2009, 72, 1121-1138. [CrossRef]

- Gruzdev, N.; Pinto, R.; Sela, S. Effect of desiccation on tolerance of Salmonella enterica to multiple stresses. Appl Environ Microbiol 2011, 77, 1667-1673. [CrossRef]

- Gavriil, A.; Thanasoulia, A.; Skandamis, P.N. Sublethal concentrations of undissociated acetic acid may not always stimulate acid resistance in Salmonella enterica sub. enterica serovar Enteritidis Phage Type 4: Implications of challenge substrate associated factors. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0234999. [CrossRef]

- Greenacre, E.J.; Lucchini, S.; Hinton, J.C.; Brocklehurst, T.F. The lactic acid-induced acid tolerance response in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium induces sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006, 72, 5623-5625. [CrossRef]

- Juneja, V.K.; Hwang, C.A.; Friedman, M. Thermal inactivation and postthermal treatment growth during storage of multiple Salmonella serotypes in ground beef as affected by sodium lactate and oregano oil. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, M1-6. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, C.E.; Smith, J.V.; Broadbent, J.R. Efficacy of washing meat surfaces with 2% levulinic, acetic, or lactic acid for pathogen decontamination and residual growth inhibition. Meat Sci. 2011, 88, 256-260. [CrossRef]

- Juneja, V.K.; Eblen, B.S.; Marks, H.M. Modeling non-linear survival curves to calculate thermal inactivation of Salmonella in poultry of different fat levels. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 70, 37-51. [CrossRef]

- Juneja, V.K.; Yadav, A.S.; Hwang, C.A.; Sheen, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Friedman, M. Kinetics of thermal destruction of Salmonella in ground chicken containing trans-cinnamaldehyde and carvacrol. J. Food Prot. 2012, 75, 289-296. [CrossRef]

- Gavai, K.; Karolenko, C.; Muriana, P.M. Effect of biltong dried beef processing on the reduction of Listeria monocytogenes, E. coli O157:H7, and Staphylococcus aureus, and the contribution of the major marinade components. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Karolenko, C.; Muriana, P. Quantification of process lethality (5-log reduction) of Salmonella and salt concentration during sodium replacement in biltong marinade. Foods 2020, 9, 1570.

- Karolenko, C.E.; Wilkinson, J.; Muriana, P.M. Evaluation of various lactic acid bacteria and generic E. coli as potential nonpathogenic surrogates for in-plant validation of biltong dried beef processing. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1648.

- Soyer, Y.; Moreno Switt, A.; Davis, M.A.; Maurer, J.; McDonough, P.L.; Schoonmaker-Bopp, D.J.; Dumas, N.B.; Root, T.; Warnick, L.D.; Gröhn, Y.T., et al. Salmonella enterica serotype 4,5,12:i:-, an emerging Salmonella serotype that represents multiple distinct clones. J Clin Microbiol 2009, 47, 3546-3556. [CrossRef]

- Leyer, G.J.; Johnson, E.A. Acid adaptation induces cross-protection against environmental stresses in Salmonella typhimurium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 1842-1847.

- Leyer, G.J.; Johnson, E.A. Acid adaptation promotes survival of Salmonella spp. in cheese. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 2075-2080.

- Calicioglu, M.; Sofos, J.N.; Samelis, J.; Kendall, P.A.; Smith, G.C. Inactivation of acid-adapted and nonadapted Escherichia coli O157:H7 during drying and storage of beef jerky treated with different marinades. J. Food Prot. 2002, 65, 1394-1405. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, P.; Muriana, P. Air-Dried Beef: Comparison of Acid-Adapted and Non-Adapted Salmonella Serovars in Process Validation to Achieve 5-log Reduction. In Proceedings of International Association of Food Protection, Cleveland, OH, July 28, 2025.

Figure 1.

Biltong process: Whole bottom round; cut into ~100-gm pieces of beef and surface inoculated with gloved finger; addition of marinade ingredients; marination in a tumbler bin; beef pieces after marination; beef hanging in a humidity oven; biltong beef pieces cut in half (~5 days).

Figure 1.

Biltong process: Whole bottom round; cut into ~100-gm pieces of beef and surface inoculated with gloved finger; addition of marinade ingredients; marination in a tumbler bin; beef pieces after marination; beef hanging in a humidity oven; biltong beef pieces cut in half (~5 days).

Figure 2.

Droëwors process: Beef and fat trimmings leftover from biltong, tumbled first with inoculated culture (10 min) and then with added ingredients (30 min), ground twice, stuffed into collagen casings, and sectioned into sausages, dried in a humidity oven, and finished droëwors beef sticks.

Figure 2.

Droëwors process: Beef and fat trimmings leftover from biltong, tumbled first with inoculated culture (10 min) and then with added ingredients (30 min), ground twice, stuffed into collagen casings, and sectioned into sausages, dried in a humidity oven, and finished droëwors beef sticks.

Figure 3.

Comparison of selective media on enumeration of an inoculum mixture of 5 Salmonella serovars during droëwors processing. Droëwors-processed beef was plated on TSA, SCA, XLD, and HE (all containing antibiotics that the Salmonella were resistant to). Treatments within the same sampled grouping were analyzed by ANOVA using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences; treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05); those with the same letters show no significant difference (p > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Comparison of selective media on enumeration of an inoculum mixture of 5 Salmonella serovars during droëwors processing. Droëwors-processed beef was plated on TSA, SCA, XLD, and HE (all containing antibiotics that the Salmonella were resistant to). Treatments within the same sampled grouping were analyzed by ANOVA using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences; treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05); those with the same letters show no significant difference (p > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Comparison of biltong processing of beef inoculated with acid-adapted and non-adapted culture treatments of

Salmonella Typhimurium serovar I, 4,[

5],12:i:-. Treatments were analyzed by RM-ANOVA using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences; treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Comparison of biltong processing of beef inoculated with acid-adapted and non-adapted culture treatments of

Salmonella Typhimurium serovar I, 4,[

5],12:i:-. Treatments were analyzed by RM-ANOVA using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences; treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Comparison of processing of biltong beef inoculated with acid-adapted or non-adapted culture treatments of 5 Salmonella serovars (S. Thompson 120, S. Heidelberg F5038BG1, S. Hadar MF60404, S. Enteritidis H3527, and S. Typhimurium H3380. Additionally, inoculated beef was dipped in either water or 5% lactic acid for 30 sec before marination. Treatments were analyzed by RM-ANOVA using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences; treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05); those with the same letters are not significantly different (p > 0.05). Acid-adapted cultures are represented by red lines, acid-dipped biltong is represented by red-filled symbols, and water-dipped biltong as blue-filled symbols.

Figure 5.

Comparison of processing of biltong beef inoculated with acid-adapted or non-adapted culture treatments of 5 Salmonella serovars (S. Thompson 120, S. Heidelberg F5038BG1, S. Hadar MF60404, S. Enteritidis H3527, and S. Typhimurium H3380. Additionally, inoculated beef was dipped in either water or 5% lactic acid for 30 sec before marination. Treatments were analyzed by RM-ANOVA using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences; treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05); those with the same letters are not significantly different (p > 0.05). Acid-adapted cultures are represented by red lines, acid-dipped biltong is represented by red-filled symbols, and water-dipped biltong as blue-filled symbols.

Figure 6.

Comparison of processing of biltong beef inoculated with acid-adapted (1% glucose) or non-adapted (1% glucose + buffer) TS broth culture treatments of 5 Salmonella serovars (S. Thompson 120, S. Heidelberg F5038BG1, S. Hadar MF60404, S. Enteritidis H3527, and S. Typhimurium H3380. Additionally, inoculated beef was dipped in either water or 5% lactic acid for 30 sec before marination. Treatments were analyzed by RM-ANOVA using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences; treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05); those with the same letters are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

Figure 6.

Comparison of processing of biltong beef inoculated with acid-adapted (1% glucose) or non-adapted (1% glucose + buffer) TS broth culture treatments of 5 Salmonella serovars (S. Thompson 120, S. Heidelberg F5038BG1, S. Hadar MF60404, S. Enteritidis H3527, and S. Typhimurium H3380. Additionally, inoculated beef was dipped in either water or 5% lactic acid for 30 sec before marination. Treatments were analyzed by RM-ANOVA using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences; treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05); those with the same letters are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

Figure 7.

Droëwors processing: comparison of beef inoculated with acid-adapted (1% glucose) or non-adapted (0% glucose) TS broth culture treatments of 5 Salmonella serovars (S. Thompson 120, S. Heidelberg F5038BG1, S. Hadar MF60404, S. Enteritidis H3527, and S. Typhimurium H3380). Treatments were analyzed by RM-ANOVA using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences; treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Droëwors processing: comparison of beef inoculated with acid-adapted (1% glucose) or non-adapted (0% glucose) TS broth culture treatments of 5 Salmonella serovars (S. Thompson 120, S. Heidelberg F5038BG1, S. Hadar MF60404, S. Enteritidis H3527, and S. Typhimurium H3380). Treatments were analyzed by RM-ANOVA using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences; treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).