Case

A 45-year-old woman with a known history of deep venous thrombosis (DVT), on warfarin and followed in a thrombosis clinic, called EMS for acute shortness of breath. Upon arrival at the hospital, she suffered cardiac arrest as the ambulance reached the emergency bay. Advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) was immediately initiated.

Initial rhythm was pulseless electrical activity (PEA). She had no known cardiac history and was on therapeutic anticoagulation, making massive pulmonary embolism (PE) the leading suspicion. After approximately 15 minutes of ongoing CPR, intravenous thrombolysis was administered.

The critical care team arrived shortly thereafter and inserted a resuscitative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) probe. Imaging confirmed proper chest compression positioning under a mechanical LUCAS device, ruling out left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. The right ventricle (RV) was severely dilated, but no visible intracardiac thrombus was identified.

At 30 minutes, despite thrombolysis, ROSC had not been achieved. Given ongoing electrical activity and adequate chest compressions, a resuscitative aortic occlusion catheter (COBRA-OS, FrontLine Medical Technologies, London, ON, Canada) was inserted via the femoral artery under ultrasound guidance and inflated after approximately 40 minutes of CPR.

Within five minutes of balloon inflation, TEE showed renewed cardiac contractions—technically a pseudo-PEA—as mechanical function remained poor and the aortic valve barely opened. At this stage, the patient had received approximately 6 mg of epinephrine per ACLS protocol.

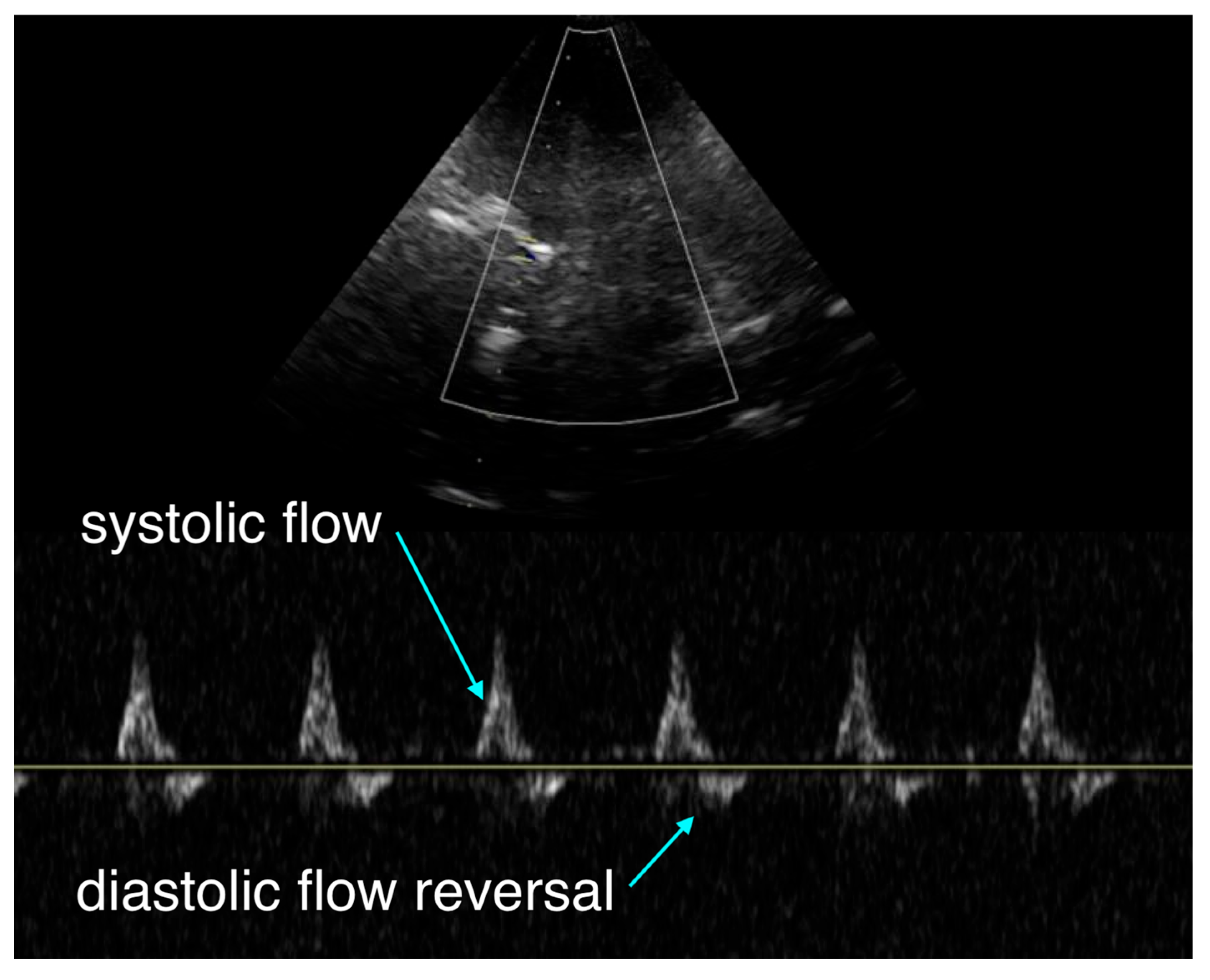

The team initiated transcranial Doppler (TCD) monitoring, which revealed systolic upstroke but diastolic flow reversal and no sustained forward flow during diastole (

Figure 1). This pattern suggested either severe cerebral vasoconstriction secondary to catecholamine effect or elevated intracranial pressure beyond diastolic arterial pressure.

At 55 minutes, both ventricles showed partial recovery of contractility. The aortic balloon was deflated to avoid excessive afterload and allow distal reperfusion. TEE demonstrated normal left-ventricular ejection fraction, an underfilled LV, and persistently dilated RV with TAPSE of approximately 10–11 mm. Blood pressure was now 150/90 mmHg, though capillary refill remained markedly prolonged (>5 seconds).

Given the ongoing requirement for high-dose epinephrine to maintain perfusion and evidence of predominant right-sided failure, the tertiary ECMO center was recontacted. Now that sustained ROSC had been achieved, the patient was accepted for transfer for potential mechanical circulatory support (MCS).

However, significant transport delays ensued: it took over 30 minutes to secure an ambulance, and another 35 minutes to reach the receiving facility. During transport, TEE remained in place, serving as a real-time hemodynamic monitor (

Figure 3). The probe was briefly disconnected and reconnected at intervals to minimize risk during patient maneuvering.

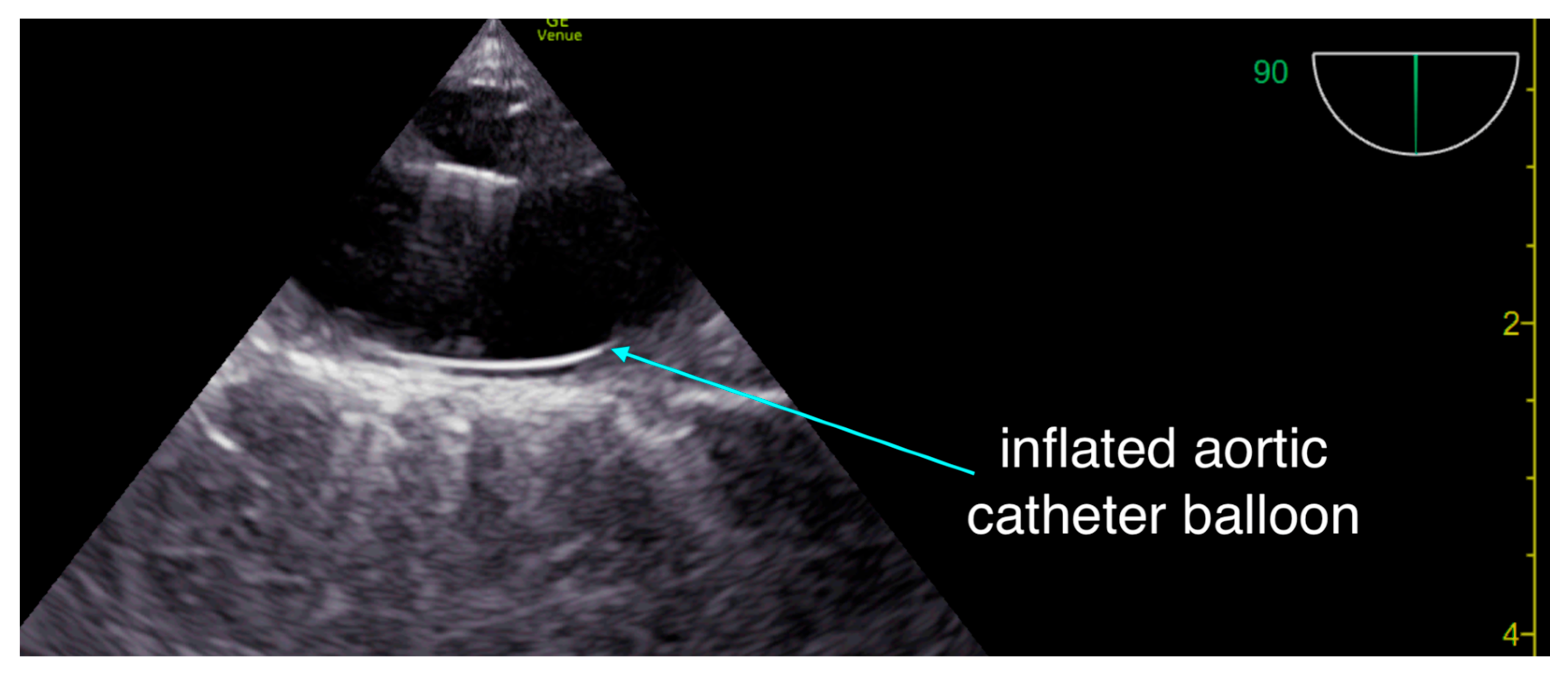

Figure 2.

Our team uses resuscitative trans-esophageal thoracic ultrasound to ascertain appropriate guidewire placement in the thoracic aorta and to monitor appropriate balloon inflation and position - in addition to monitoring for appropriate position of chest compressions.

Figure 2.

Our team uses resuscitative trans-esophageal thoracic ultrasound to ascertain appropriate guidewire placement in the thoracic aorta and to monitor appropriate balloon inflation and position - in addition to monitoring for appropriate position of chest compressions.

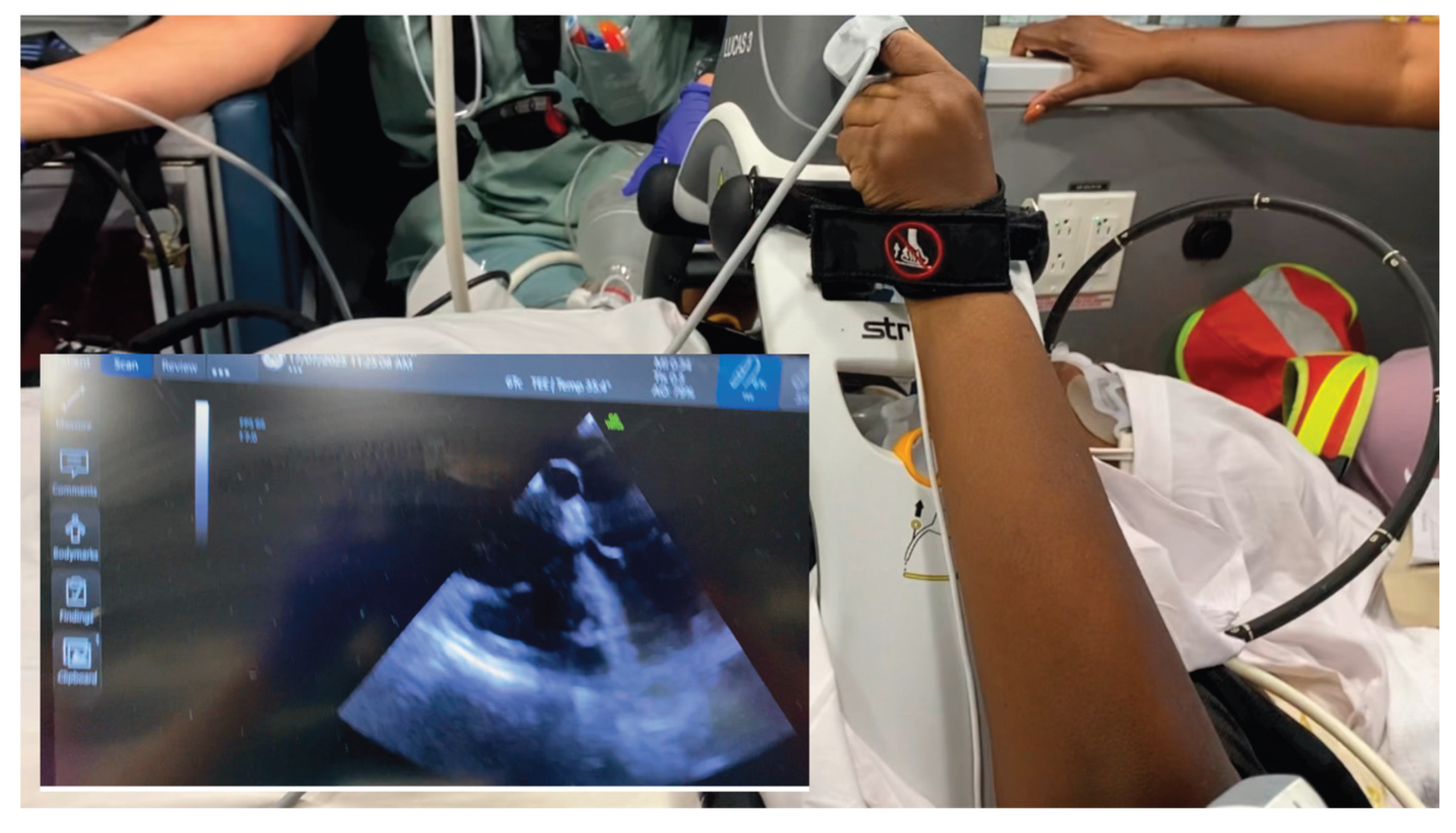

Figure 3.

In-transit critical-care hemodynamic monitoring setup. The ultrasound screen is positioned adjacent to the accompanying physician, allowing real-time visualization of cardiac function and hemodynamics during transfer with the indwelling TEE probe (inset in the image here for illustrative purposes).

Figure 3.

In-transit critical-care hemodynamic monitoring setup. The ultrasound screen is positioned adjacent to the accompanying physician, allowing real-time visualization of cardiac function and hemodynamics during transfer with the indwelling TEE probe (inset in the image here for illustrative purposes).

Throughout transport, the patient remained on an epinephrine infusion, with end-tidal CO₂ > 40 mmHg and systolic arterial pressures >100 mmHg, although pulse pressure was narrow (diastolic 70–90 mmHg).

Upon arrival, neurologic examination revealed Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) 3, minimal pupillary reactivity, and absent gag reflex. Repeat TCD again showed systolic flow with diastolic reversal and no forward diastolic flow. Attempts to transition from epinephrine to norepinephrine and vasopressin resulted in profound hypotension and rapid biventricular deterioration.

A multidisciplinary discussion concluded that initiation of ECMO at over 2 hours post-ROSC was unlikely to yield neurologically meaningful recovery. Support was withdrawn after family discussion.

Discussion

1. Personalizing Resuscitation Through Physiologic Monitoring

Modern resuscitation must evolve beyond algorithmic ACLS into patient-specific, physiology-guided management. Multiple tools used during this case—TEE, TCD, aortic occlusion, and NIRS—provide complementary data streams that together can guide individualized care.

Transcranial Doppler (TCD) offers a noninvasive window into cerebral flow during arrest, a domain largely invisible to current monitors. The pattern of antegrade systolic but reversed diastolic flow seen here has been previously described in pediatric arrest literature [

1]. This waveform indicates critically impaired downstream flow, consistent with either severe vasoconstriction or markedly elevated intracranial pressure. Within our own conceptual framework of hemodynamic interfaces, this represents uncoupling of interface 2, the arteriolar–capillary interface, where cerebral perfusion is compromised despite adequate proximal pressure [

2]. This tool may allow clinicians to differentiate between potentially reversible vasoconstrictive hypoperfusion and irreversible intracranial hypertension, a distinction currently impossible in real time.

Resuscitative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was pivotal throughout the arrest, first confirming appropriate compression vector and absence of LVOT obstruction, and later tracking evolving ventricular function. In addition to its diagnostic role, TEE can serve as a continuous hemodynamic monitor, even during transport [

3,

4]. Unlike transthoracic views, which are often impossible due to chest compression devices and immobilization, the indwelling probe allows uninterrupted visualization of ventricular filling and contraction. In this case, TEE enabled optimization of chest-compression quality, verification of guidewire placement for the aortic occlusion catheter, and continuous reassessment of perfusion state—functions that extend its utility far beyond diagnosis.

Resuscitative aortic occlusion - the physiologic rationale in non-traumatic cardiac arrest lies in selectively augmenting coronary and cerebral perfusion while minimizing systemic catecholamine burden [

5]. By creating a proximal pressure gradient favoring central organ perfusion, aortic occlusion can enhance myocardial and cerebral flow without the deleterious microcirculatory constriction caused by high-dose vasopressors. In this case, the improvement in cardiac motion after balloon inflation suggests that mechanical augmentation of perfusion pressure may have contributed to achieving ROSC, though the contribution of delayed thrombolysis cannot be excluded.

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) provides another dimension of physiologic feedback by continuously measuring venous-weighted regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO₂) [

6]. This measurement reflects the balance between oxygen delivery and consumption, not simply arterial oxygen content. Multiple studies have linked higher or rising intra-arrest rSO₂ values with increased likelihood of ROSC and improved neurologic outcomes, whereas persistently low readings correlate with futility [

7]. Real-time rSO₂ trends allow providers to assess the adequacy of chest compressions, ventilation, and perfusion pressure. In some cases, sudden rises of 10 percentage points or more have signaled ROSC before palpable pulses were detected.

Taken together, these modalities illustrate the emerging paradigm of physiology-based resuscitation. By integrating real-time monitoring of macrocirculation, microcirculation, and organ oxygenation, clinicians can dynamically adapt interventions to the individual patient’s evolving physiology.

2. Equitable Access to Mechanical Circulatory Support

Despite potential physiologic salvageability, this patient could not access timely mechanical circulatory support (MCS). This systemic inequity remains a critical determinant of outcome, and illustrates the dire need for medical systems to expand rapid access to mechanical circulatory support for unstable patients.

Trials such as ARREST [

8] and DANGER [

9] demonstrate improved survival when extracorporeal CPR (ECPR) or mechanical support is instituted early enough in refractory arrest or cardiogenic shock. However, many community hospitals lack immediate ECMO access or cannulation teams. Even within major cities, geography and logistics continue to dictate survival chances. As this case demonstrates, over an hour’s delay in transfer effectively nullified the physiologic recovery that had been achieved.

It therefore behooves us, as a medical community, to improve availability and access to these therapies for our patients. Transfer to tertiary care centers, despite willingness on all sides, as this case illustrates, often results in harmful delays. A similarly inherent problem with mobile ECMO units is the time required for a team to assemble and reach the patient. Developing hub-and-spoke ECMO networks, where satellite hospitals initiate cannulation before transfer, could reduce time to reperfusion for well selected patients. Such models, coupled with mobile teams and regional coordination, have already shown success internationally [

10]. Policy-level initiatives are essential to ensure that survival is not determined by postal code. This is an approach we are currently working on between our centers, and we urge others to do so as well and share their experience.

Ultimately, while technology enables personalization of resuscitation, health-system design determines who benefits from it. The ethical imperative for critical care networks is to ensure that geography does not define survivability in cardiac arrest.

Conclusion

It is important to realize that cardiac arrest is a rapidly evolving field, and that ACLS in its present form is no longer the cutting edge of resuscitation, and we as clinicians should no longer be satisfied with it outside of the first handful of minutes of management: the evidence for ECPR is already here. Femoral arterial lines, resuscitative TEE, aortic occlusion catheters are being studied, and those with experience using them keep accumulating anecdotal but often powerful evidence of management-changing interventions. Trans-cranial Doppler sonography as well as near-infrared spectroscopy may help target neuroprotective resuscitation. These are all ways in which resuscitation from cardiac arrest can be personalized in hopes of improving outcomes. Naturally, there is a tremendous amount of research that needs to be done, making this a space to watch.

However, meaningful progress also depends on equitable access to MCS and rapid ECMO initiation for carefully selected patients, ensuring that advanced resuscitative tools are available to all, regardless of location.

References

- Iordanova, B; Wainwright, MS; Koehler, RC. Alterations in cerebral blood flow after resuscitation from cardiac arrest: applications for pediatric care. Front Pediatr. 2017, 5, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rola, P; Kattan, E; Siuba, MT; Haycock, K; Crager, S; Spiegel, R; Hockstein, M; Bhardwaj, V; Miller, A; Kenny, JE; Ospina-Tascón, GA; Hernandez, G. Point of view: a holistic four-interface conceptual model for personalizing shock resuscitation. J Pers Med. 2025, 15(5), 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teran, F; Diederich, T; Owyang, CG; et al. Resuscitative transesophageal echocardiography in critical care. J Intensive Care Med. 2025, 40(3), 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douflé, G; et al. Echocardiography for adult ECMO patients. Crit Care. 2015, 19, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rola, P; St-Arnaud, P; Karimov, T; Brede, JR. REBOA-assisted resuscitation in non-traumatic cardiac arrest due to massive pulmonary embolism: a case report with physiological and practical reflections. J Endovasc Resusc Trauma Manag. 2021, 5(2), 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Cardiopulmonary Bypass: Principles and Practice., 4th ed.; Gravlee, GP, Davis, RF, Kurusz, M, Utley, JR, Eds.; Wolters Kluwer Health: Philadelphia, PA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Baugstø, I; Gjesdal, N; King, SE; Pedersen, SA; Bache-Wiig, LPB; Skjærvold, NK; Uleberg, O; et al. Cerebral oxygen monitoring during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a scoping review. Resuscitation Plus. 2025, 26, 101082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannopoulos, D; Bartos, J; Raveendran, G; Walser, E; Connett, J; Murray, TA; Collins, G; Zhang, L; Kalra, R; Kosmopoulos, M; et al. Advanced reperfusion strategies for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and refractory ventricular fibrillation (ARREST): a phase 2, single-center, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2020, 396(10265), 1807–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møller, JE; Engstrøm, T; Jensen, LO; et al. Microaxial flow pump or standard care in infarct-related cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2024, 390(15), 1382–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatti, A; et al. ECMO cannulation across New England: trends in transports and cannulating centers from 2011 to 2022. Heart Lung. 2025, 78, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).