1. Introduction

The clinical success of implant surgery is fundamentally dependent on effective osseointegration, which is strongly influenced by the surface properties of titanium-based implants [

1]. Consequently, numerous surface modification techniques—particularly those designed to enhance surface roughness—have been developed to accelerate the biological process of osseointegration and facilitate immediate or early functional loading. Roughened implant surfaces outperform smooth surfaces by increasing the available bone-implant contact area and promoting cellular adhesion, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation [

2]. Among the various approaches, including acid etching, grit blasting, anodization, and calcium phosphate coating, the sandblasted, large-grit, acid-etched (SLA) technique has emerged as the clinical gold standard over the past several decades [

3].

Despite the well-documented success of SLA implants, their biological performance is compromised by “biological aging”, largely attributable to carbon contamination [

4]. Upon exposure to ambient air, hydrocarbons rapidly absorb to titanium surfaces, resulting in inevitable surface contamination [

5]. As a result, most commercially available dental implants are presumed to be heavily coated with carbonaceous molecules by the time they are clinically applied [

6]. This accumulation of surface carbon significantly diminishes protein adsorption, cellular attachment, proliferation, and differentiation—key processes required for robust osseointegration [

5]. Experimental evidence demonstrates that, compared with pristine implant surfaces, those aged for just four weeks exhibit markedly reduced fibronectin and albumin adsorption, decreased numbers of adherent osteogenic cells, and limited areas of newly formed bone [

5,

6,

7,

8].

In addition to carbon contamination, the time-dependent accumulation of hydrocarbons on titanium implant surfaces induces a progressive loss of hydrophilicity, a property widely recognized as one of the most influential factors governing cell attachment [

6,

9]. Newly processed titanium surfaces typically display superhydrophilicity, with contact angles near 0°, but after only four weeks of ambient storage they undergo a marked transition toward hydrophobicity, with angles exceeding 60° [

8]. Although the adoption of hydrophilicity as a direct indicator of bioactivity remains debated, it has been extensively investigated due to its close association with early cell–material interactions. Importantly, a clear inverse linear relationship between surface wettability and the number of adherent osteogenic cells has been demonstrated [

6], and hydrophilic surfaces have also shown improved hemocompatibility [

10] (

Figure 1), which accelerates the osteogenic cascade by supporting early calcium and phosphate ion adsorption at the implant–blood interface [

11]. Collectively, these findings suggest that maintaining or restoring hydrophilicity may be critical for optimizing early biological responses and achieving superior clinical outcomes in implant therapy.

As a result, surface decontamination or reactivation methods—most notably plasma treatment—have attracted increasing attention in recent years. Similar to ultraviolet photofunctionaliztion, plasma treatment is a post-manufacturing technique that can be applied chairside in clinical settings without altering implant topography [

12,19]. Plasma, widely regarded as the fourth state of matter, is defined as an electrically charged gas created by applying high voltage or high temperature to specific gases such as O₂, Ar, N₂, and NH₃, with the gas type determining the nature of reactive species incorporated onto the surface [

12,

13]. These reactive oxygen- or nitrogen-containing free radicals enhance surface decomposition capability, promote the removal of carbon contaminants, and increase wettability [

14]. Mechanistically, reactive oxygen species generated during plasma exposure induce redox reactions that break carbon bonds in organic molecules, decompose contaminants through volatilization, and form hydrophilic hydroxyl groups, thereby reducing oxidative stress and the initial inflammatory response in peri-implant tissues [

15,

16]. Clinically, non-thermal (atmospheric pressure) plasma is particularly advantageous due to its portability, open-air applicability, and rapid activation time [

12,

17,

18]. By restoring hydrophilicity without altering micro- or nanoscale roughness, plasma treatment strengthens the biological interface between titanium surfaces and surrounding bone and soft tissues, ultimately supporting improved osseointegration [

19,

20].

Numerous studies have investigated the effects of plasma treatment on titanium surfaces, particularly regarding the biological responses of surrounding tissues. In vitro, Ujino et al. demonstrated that atmospheric pressure plasma treatment increased bovine serum albumin (BSA) adsorption and enhanced rat bone marrow (RBM) cell adhesion on titanium disks [

16]. Since albumin prevents the adsorption of pro-inflammatory and bacteria-associated proteins, its preferential adsorption plays a pivotal role in promoting favorable osseointegration [

21]. Plasma-activated surfaces further exhibited denser attachment of osteoblasts and fibroblasts, elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity, and increased expression of transcription factors essential for osteoblastic differentiation [

16,

22]. At the in vivo level, Tsujita et al. reported consistent findings using plasma-treated titanium screws implanted in rat femurs, observing elongation of cell processes—an indicator of improved cell adhesion—together with reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and diminished carbon peaks, confirming effective surface decontamination [

10]. Collectively, these in vitro and in vivo results underscore the capacity of plasma treatment to enhance protein adsorption, promote osteogenic cell activity, and attenuate oxidative stress, thereby supporting a biologically favorable environment for osseointegration.

The aim of the present study was to determine whether the favorable biological effects of plasma surface activation, previously demonstrated in vitro and in vivo, are reproducible in clinical practice. Specifically, we sought to evaluate whether plasma treatment could stabilize implant stability during the early healing phase, thereby enabling functional loading as early as the fourth postoperative week. Although plasma treatment has recently gained attention, patient-based follow-up studies remain limited. In this investigation, plasma surface activation was performed using a novel device, the ACTILINK™ Reborn (Plasmapp Co., Ltd., Daejeon, Korea), which generates plasma under optimized vacuum conditions (5–10 Torr) to maximize hydrocarbon removal efficiency. This compact, chairside-compatible system (170 mm W × 266 mm D × 346 mm H) was specifically engineered for convenient clinical use [

23]. In a prior animal study, application of the ACTILINK™ system resulted in approximately 58% reduction in hydrocarbon contamination, a 25% increase in protein adsorption, and a 39% enhancement in cell attachment, collectively accelerating osseointegration in rabbit models [

24]. Building on this preclinical evidence, the present study aims to provide patient-based clinical data supporting the biological and practical benefits of chairside plasma treatment in dental implantology.

2. Materials and Methods

Ethics statement. This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Daegu Catholic University Medical Center (IRB No. 2025-06-021), and all procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Patients and case selection. From June 2023 to October 2024, forty-seven patients who underwent implant surgery at the Department of Dentistry, Daegu Catholic University Medical Hospital, were included in this study. A total of 73 implants were placed, comprising 28 in the maxilla and 45 in the mandible (

Table 1). Patients were enrolled irrespective of age or sex, except for those presenting systemic conditions known to critically impair osseointegration (e.g., uncontrolled diabetes, metabolic bone disease). Individuals unable to attend weekly follow-up visits due to physical limitations or geographic constraints were also excluded. Notably, smokers and bruxers were not excluded. This retrospective cohort study involved only implants that had undergone plasma surface treatment. To ensure the feasibility of early functional loading at the fourth postoperative week, implants were included only if they achieved a primary stability of ≥35 N·cm at placement, measured using a manual ratchet. A broad spectrum of cases was incorporated within these parameters, including those involving extensive bone augmentation (n=27), sinus elevation (n=7), and immediate placement in fresh extraction sockets (n=18).

Implant systems. Four distinct implant systems were used in this study: Biotem Implant Fixture (Biotem Implant Co., Ltd., Hanam-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea); OsseoSpeed™ (Astra Tech Implant System, Dentsply Sirona, Mölndal, Sweden); AnyOne Internal Fixture (Megagen Implant Co., Ltd., Daegu, South Korea); and IS-II Active Fixture (Neo Biotech Co., Ltd., Seoul, South Korea). The surface characteristics varied according to the manufacturer. Biotem implants featured a conventional sandblasted, large-grit, acid-etched (SLA) surface without further chemical modifications. Megagen implants employed the XPEED® surface, based on the SLA protocol but enhanced with calcium ion incorporation to accelerate bone healing. Neo Biotech’s IS-II Active implants also utilized a conventional SLA surface without additional surface agents. In contrast, Astra Tech’s OsseoSpeed™ implants were treated with a proprietary fluoride-modified titanium surface designed to promote early osseointegration.

Due to the retrospective design of this study, implant systems could not be standardized. Nevertheless, three of the four systems were based on SLA-type surface modification, which is widely accepted as a benchmark approach for enhancing osseointegration [

3]. Although OsseoSpeed™ implants differ in utilizing a fluoride-modified surface produced through TiO₂ sandblasting and hydrofluoric acid etching, their resulting surface roughness is comparable to that of SLA-treated implants. Importantly, irrespective of the specific pre-packaging surface modifications, all titanium implant surfaces are inevitably exposed to ambient air before placement, leading to hydrocarbon accumulation that reduces surface biocompatibility [

25].

Plasma activation cycle. Immediately before surgical placement, each dental implant underwent a 1-minute plasma activation using the ACTILINK™ Reborn device (Plasmapp Co., Ltd., Daejeon, Republic of Korea). The system is equipped with three independent plasma modules, supported by a shared vacuum pump and pressure gauge, allowing plasma to be generated independently within each module [

4]. A fixture driver holder located at the center of the device secures the implant fixture during treatment. Once the fixture is seated, a cylindrical Pyrex® component descends to connect with a silicone stopper, sealing the chamber from ambient air and creating a partial vacuum [

24].

Each activation cycle lasts 60 seconds and consists of four sequential phases: (1) vacuum formation (30 s), during which a base pressure of 5 Torr is established via the vacuum pump; (2) plasma exposure (8 s), generated by a powered electrode at the top of the chamber and applied directly to the implant surface; (3) decontamination (17 s), in which residual surface impurities are removed through the vacuum port; and (4) venting (5 s), which evacuates the gas from the chamber [

24]. This process enables efficient removal of hydrocarbon contaminants while preserving the original surface topography of the implant.

Surgical procedures and prosthesis delivery. Routine local anesthesia was administered, and full-thickness mucoperiosteal flaps were elevated. Final drilling was performed using a drill 1.0 mm smaller than the intended implant diameter, and implants were placed with their coronal margin positioned 2 mm below the proximal bone crest. During drilling, each implant surface underwent immediate plasma activation using the ACTILINK™ Reborn device, with two consecutive treatment cycles applied to every fixture. In cases requiring bone grafting, Sticky Bone™—a combination of particulate graft material and autologous fibrin glue prepared from the patient’s blood—was utilized. The final insertion torque was measured with a calibrated torque wrench (LASAK Ltd., Prague, Czech Republic) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Postoperatively, patients received amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (500/125 mg) three times daily for infection control.

All sutures were removed two weeks after surgery. At three weeks postoperatively, impressions were taken for provisional restorations, which were delivered at week 4. Following one month of provisional prosthesis use, definitive impressions were obtained, and final prostheses were delivered at eight weeks postoperatively.

Implant stability measurements. To quantitatively evaluate implant stability, resonance frequency analysis (RFA) was performed at baseline (immediately after placement) and at postoperative weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, and up to week 8 using the MEGA ISQ™ device (Megagen Implant Co., Ltd., Daegu, South Korea). A transducer peg (Mega ISQ Peg) was hand-tightened into each implant fixture using finger force, applying an estimated torque of approximately 4–6 N·cm, as recommended by the manufacturer. For implants restored with provisional prostheses, the prostheses were temporarily removed prior to measurement. During assessment, the probe was positioned 1–2 mm from the peg, oriented perpendicular to its longitudinal axis, and maintained without direct contact [

26]. At each time point, three ISQ values were obtained—one each from the buccal, lingual, and mesial directions—and the mean value was recorded to two decimal places.

Statistical analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Time-dependent changes in implant stability were assessed using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). When significant differences were observed, pairwise comparisons were conducted with paired t-tests, and Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust for type I error in post hoc analysis. Time-dependent ISQ changes were also visualized with line graphs. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Tendency

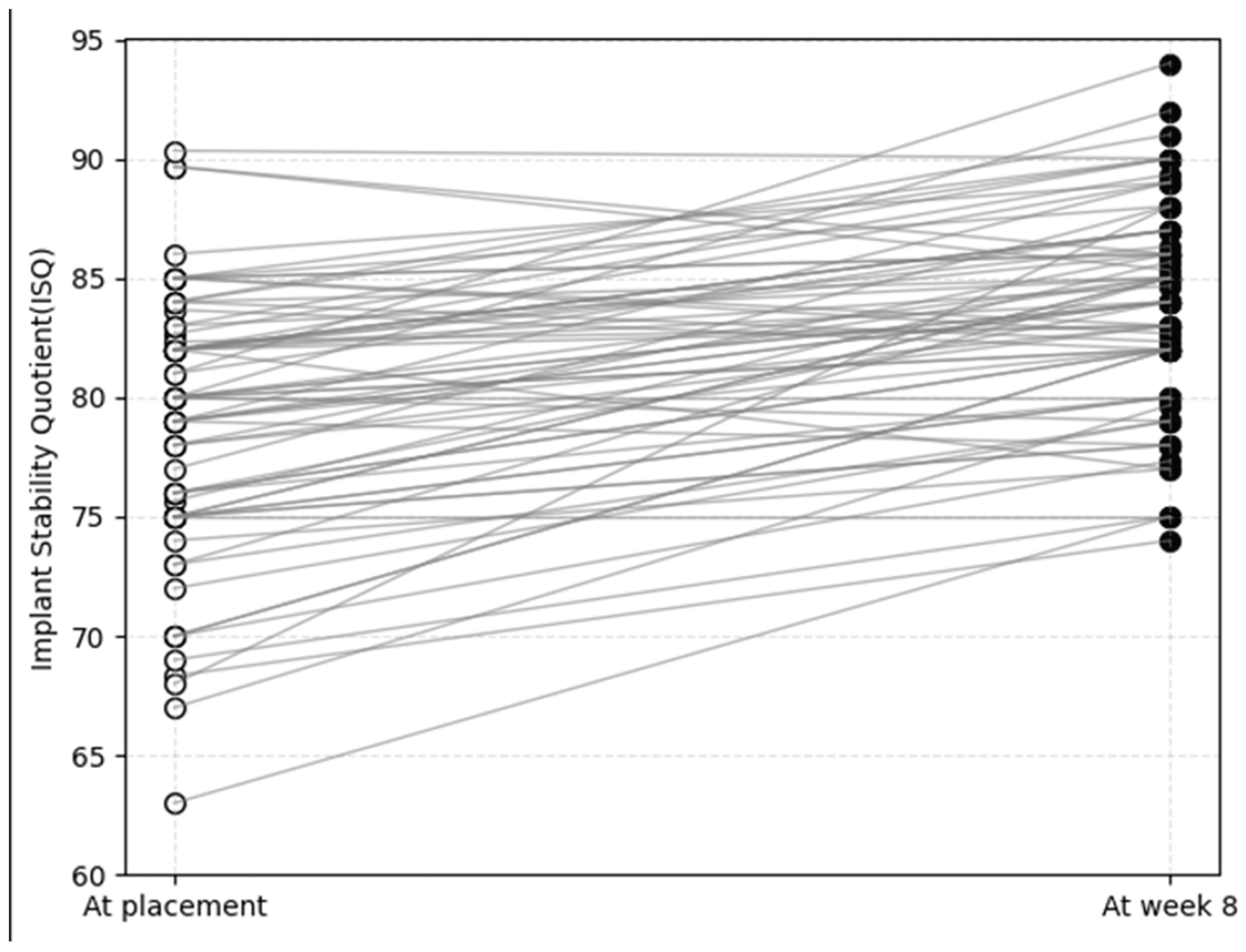

To compare overall trends in implant stability, initial ISQ values at placement (ISQ

i) and final ISQ values at week 8 (ISQ

8) were individually plotted (

Figure 2). Although ISQi values showed considerable variation, ranging from 63.0 to 90.3, most converged toward higher stability by week 8, except for three cases with exceptionally high initial values (>85.0). Ultimately, all implants reached ISQ values above 74.0 at week 8. A representative case with a relatively low ISQ

i of 68.0 demonstrated the steepest slope of stability gain, achieving an ISQ

8 of 88.0.

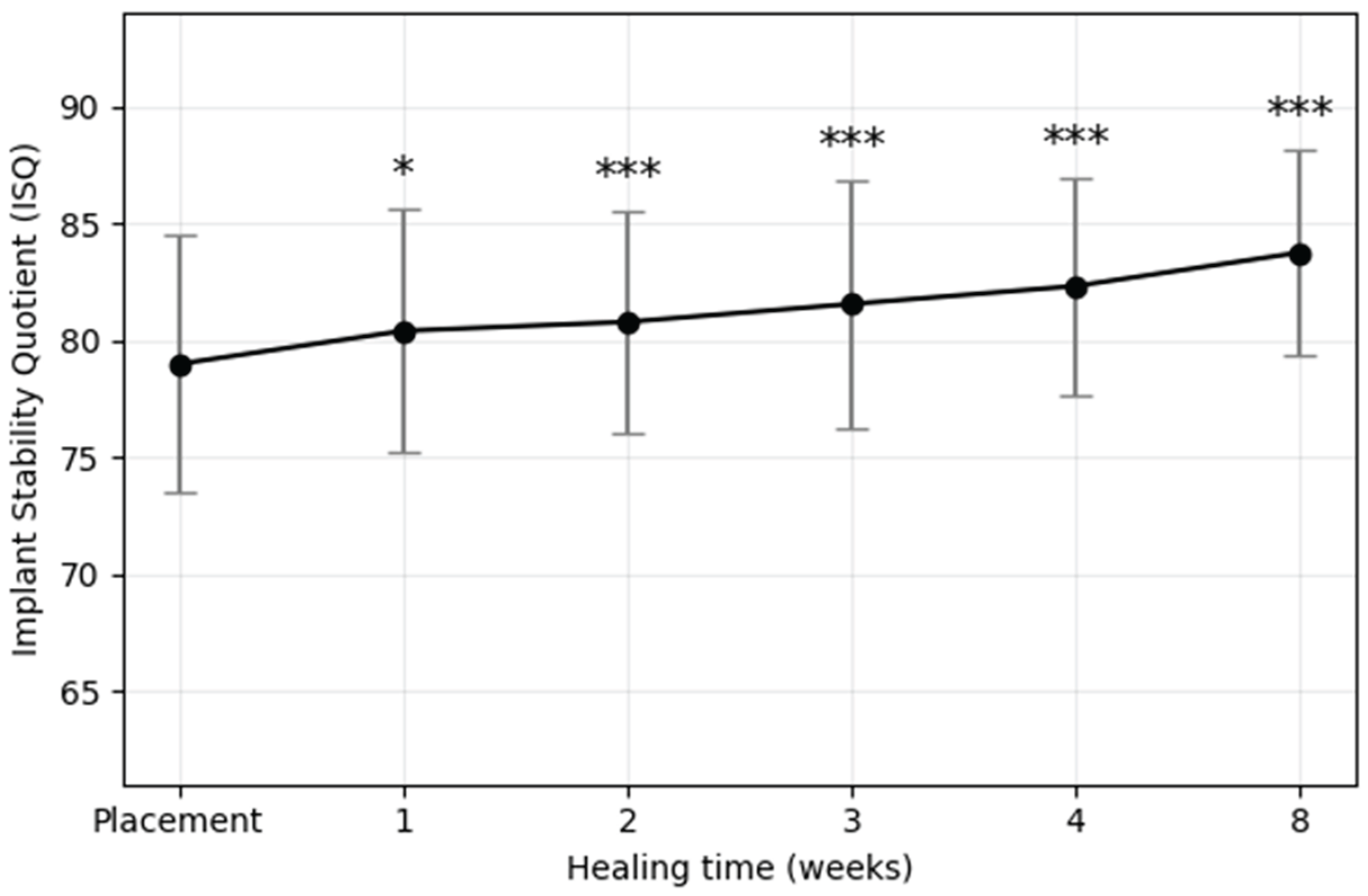

The mean ISQ values recorded at each postoperative time point are presented in

Figure 3 and

Table 2. Statistically significant differences relative to ISQ

i were indicated with asterisks (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). ISQ values demonstrated a consistent upward trajectory across the healing period, with no evidence of a transient stability dip. The steepest increase occurred within the first three weeks, followed by a moderate but steady rise thereafter. Repeated-measures ANOVA confirmed a significant effect of healing time on ISQ values, and post hoc analysis revealed that ISQ values at weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, and 8 were all significantly higher than ISQ

i. The mean ISQ8 value was 4.77 greater than the mean ISQ

i, and the standard deviation progressively decreased over time (from ±5.52 at baseline to ±4.36 at 8 weeks), suggesting reduced variability and improved predictability of implant stability.

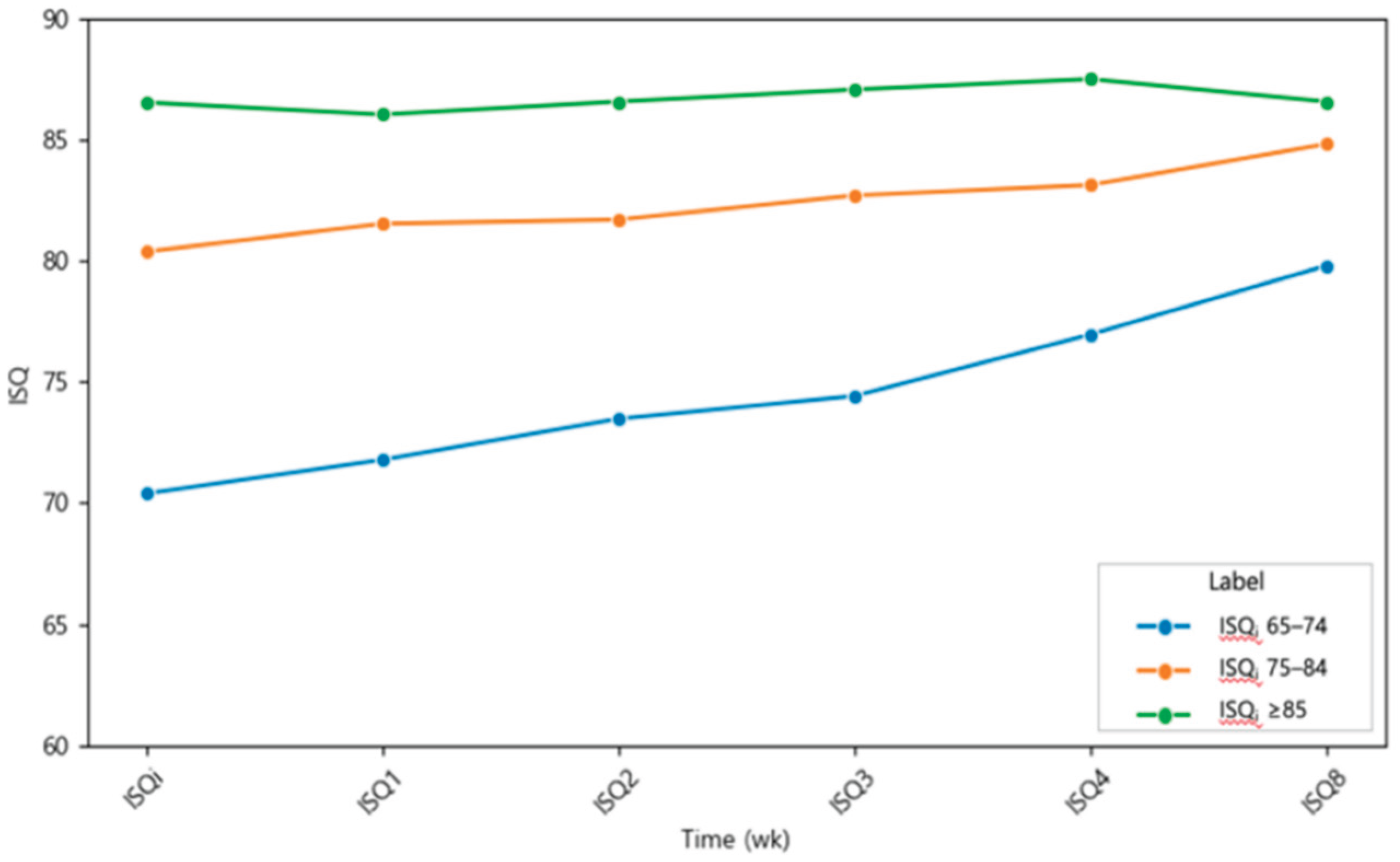

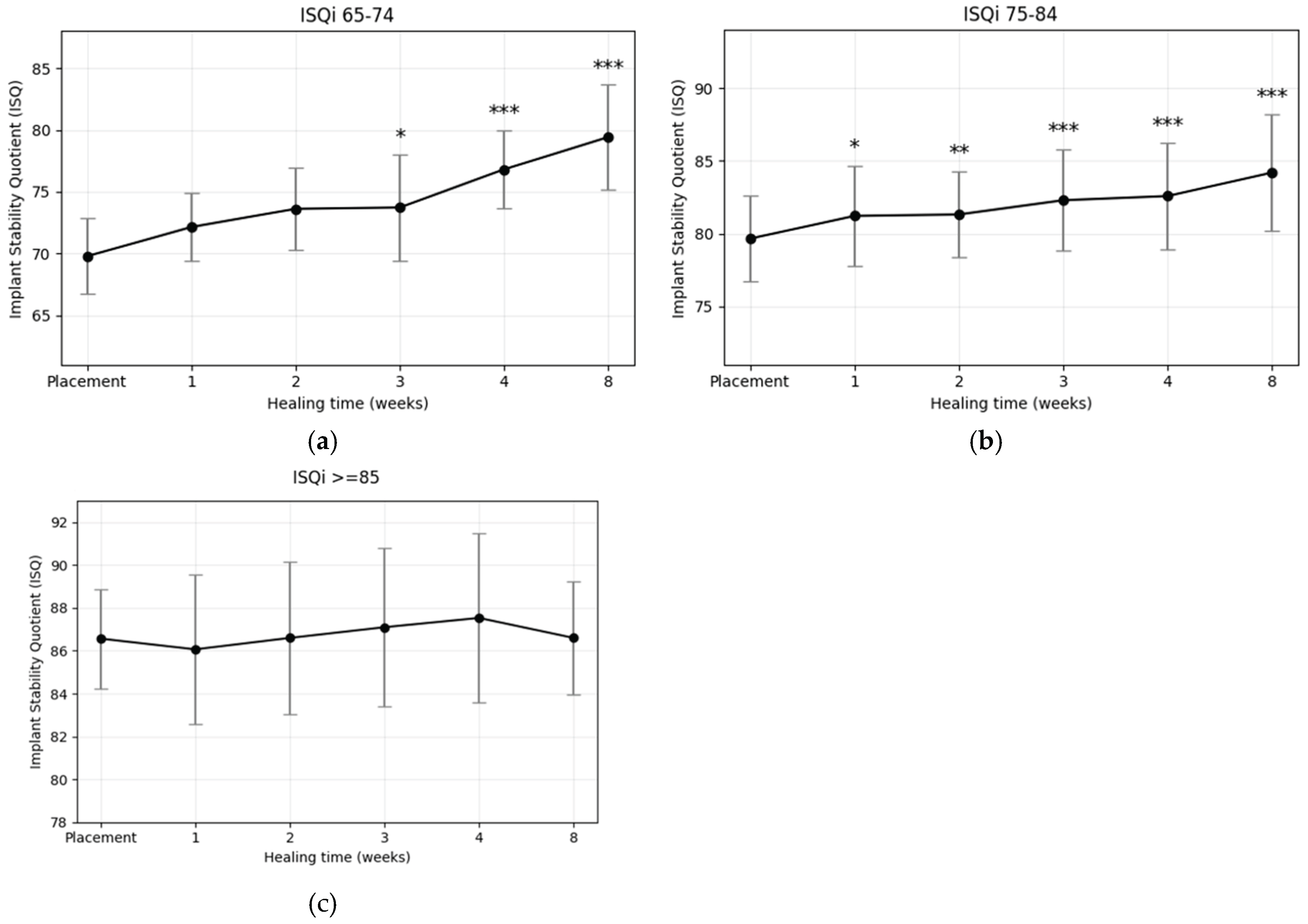

3.2. Initial ISQ (ISQi) Ranges

For comparative analysis, the dataset was stratified into three cohorts according to primary ISQ values: (1) moderate initial stability (ISQi 65–74), (2) moderately high initial stability (ISQi 75–84), and (3) high initial stability (ISQi ≥85). ISQ values at each follow-up visit were labeled according to the corresponding postoperative week (ISQi to ISQ8). In the moderate stability group (ISQi 65–74), ISQ values increased continuously throughout the healing period, with only a transient plateau observed at week 3. Although no statistically significant differences were detected during the first two weeks, a significant increase emerged at week 3 (p < 0.05) and persisted through week 8. In the moderately high stability group (ISQi 75–84), ISQ values also followed a steadily increasing trajectory, with significant improvements evident from week 1 onward and maintained across all subsequent time points. Importantly, neither group exhibited a stability dip at any stage of the healing period. In contrast, implants in the high stability group (ISQi ≥85) demonstrated no distinct trend of increase or decrease over time. No statistically significant differences were identified at any follow-up point, and while mean ISQ values consistently remained above 86, the final mean at week 8 regressed slightly toward the basline level.

Changes in implant stability from placement to week 8 for each ISQ

i group (65–74, 75–84, and ≥85) are summarized in

Table 3, with mean weekly values presented in

Table 4. The corresponding trends are illustrated in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5a–c. Paired t-tests were performed to assess whether mean differences between baseline and week 8 ISQ values were statistically significant within each group. In the ISQ

i 65–74 group, which exhibited the lowest primary stability, implants showed the most pronounced increase, with a mean ISQ gain of 9.64 (p < 0.001). Similarly, the ISQ

i 75–84 group demonstrated a significant rise, with a mean increase of 4.55 ISQ at week 8 compared with baseline (p < 0.001). In contrast, implants in the ISQ

i ≥85 group showed no significant change; the mean ISQ at week 8 decreased slightly relative to baseline. These findings indicate that plasma treatment led to significant stability gains when the initial ISQ was ≤84, whereas implants with very high primary stability (≥85) exhibited no further improvement over time.

To further characterize the dynamics of implant stability, the osseointegration speed index (OSI), defined as the monthly increase in ISQ, was calculated (

Table 3). Only cohorts that demonstrated a statistically significant change between baseline (ISQ

i) and week 8 (ISQ

8) were included; thus, the high-stability group (ISQ

i ≥85) was excluded. OSI was calculated as (ISQ

8 – ISQ

i) / 2, representing the mean increase in ISQ units per month over the 8-week observation period. As OSI is directly proportional to overall ISQ change, intergroup differences in OSI reflected the corresponding statistical significance observed for ISQ changes. In the ISQ

i 65–74 group, the OSI was 6.43 ± 3.10, more than twice that of the ISQ

i 75–84 group, which showed an OSI of 3.03 ± 2.48. This indicates that implants with lower initial stability exhibited a substantially faster rate of stability gain compared with those with moderately high initial stability.

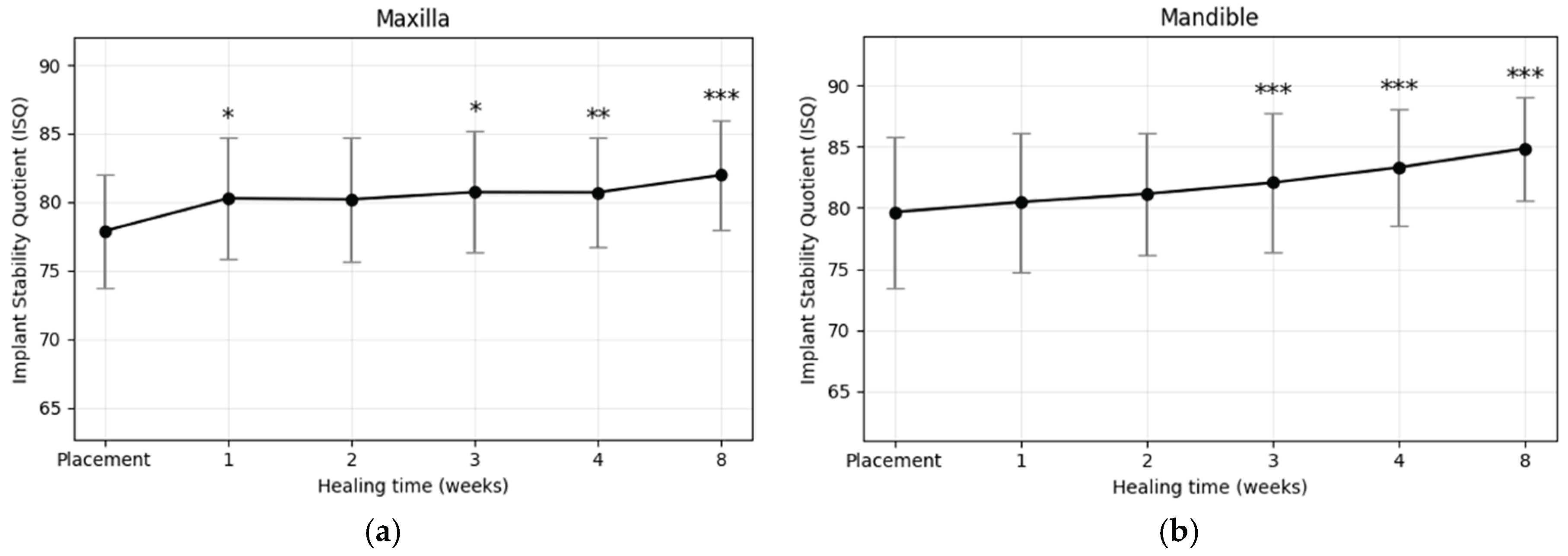

3.3. Implant Location

A statistically significant increase in ISQ values during the healing period was observed in implants placed in both the maxilla and mandible (

Figure 6a,b). Paired t-test results (

Table 5) confirmed significant mean ISQ gains in the maxilla (ΔISQ = 4.08 ± 3.96, p < 0.001) and mandible (ΔISQ = 5.19 ± 4.97, p < 0.001). At baseline, initial ISQ values were slightly higher in the mandible (79.66 ± 6.18) compared with the maxilla (77.88 ± 4.13). This difference persisted at week 8, with mean ISQ values of 84.85 ± 4.23 in the mandible and 81.96 ± 4.04 in the maxilla. The osseointegration speed index (OSI) was also greater in the mandible (0.65 ± 0.62) than in the maxilla (0.51 ± 0.49), indicating a faster rate of stability gain over the 2-month period. Collectively, implants placed in the mandible exhibited higher primary stability and greater subsequent increases in stability than those in the maxilla (p < 0.001), likely reflecting the denser, more compact bone quality of the mandible.

3.4. Length and Width of Implant Fixtures

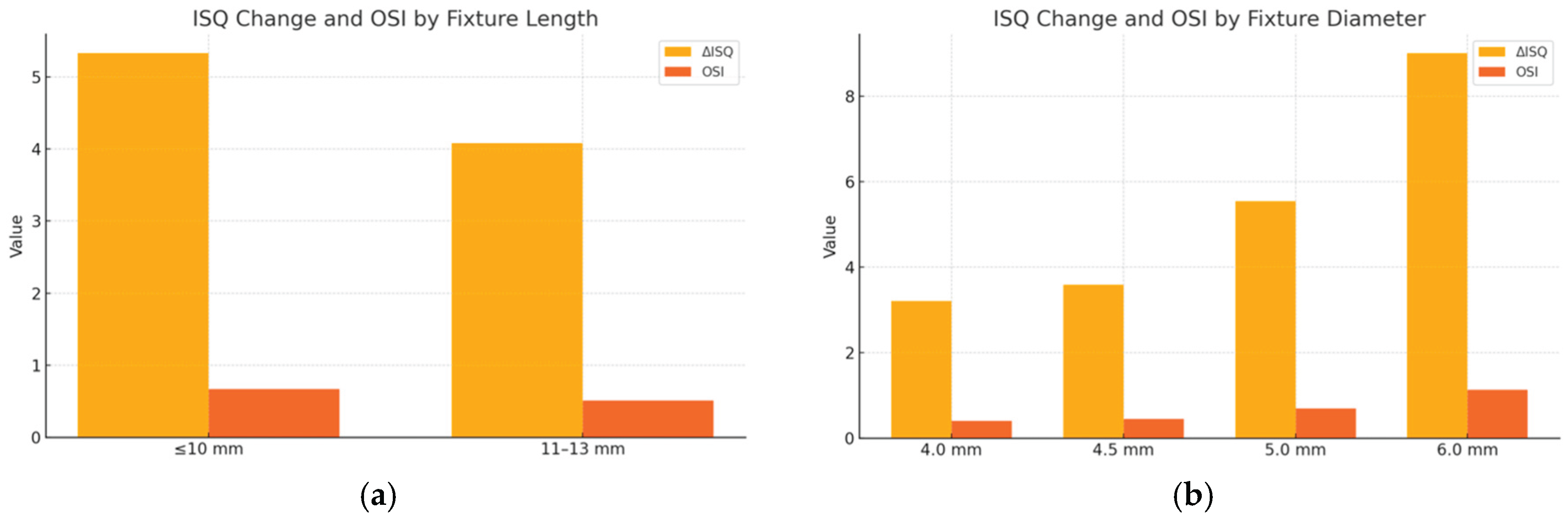

The influence of implant fixture length and diameter on ISQ changes from placement to 8 weeks postoperatively was evaluated (

Table 6 and

Table 7). As shown in

Table 6, implants with a fixture length ≤10 mm demonstrated a greater increase in ISQ values (ΔISQ = 5.33 ± 4.77) compared with those 11–13 mm in length (ΔISQ = 4.08 ± 4.37). The OSI was likewise higher in the shorter-length group (0.67 ± 0.60 vs. 0.51 ± 0.54), and the difference in mean ISQ at week 8 reached statistical significance (p < 0.05), suggesting that shorter implants may exhibit enhanced osseointegration dynamics during early healing.

Table 7 summarizes the results stratified by implant fixture diameter. Although wider-diameter implants tended to show greater increases in ISQ and higher OSI values—with 6.0 mm implants demonstrating the largest mean ISQ gain (ΔISQ = 9.00 ± 3.61) and highest OSI (1.13 ± 0.45)—these differences did not reach statistical significance, likely due to variability and limited sample size.

Figure 7.

Changes in implant stability quotient (ΔISQ) and osseointegration speed index (OSI) between placement and week 8 according to implant fixture dimensions. (a) Fixture length: implants ≤10 mm showed greater ΔISQ and OSI compared with longer implants; (b) Fixture diameter: wider implants tended to show greater ΔISQ and OSI, with 6.0 mm implants exhibiting the largest increase, although differences were not statistically significant.

Figure 7.

Changes in implant stability quotient (ΔISQ) and osseointegration speed index (OSI) between placement and week 8 according to implant fixture dimensions. (a) Fixture length: implants ≤10 mm showed greater ΔISQ and OSI compared with longer implants; (b) Fixture diameter: wider implants tended to show greater ΔISQ and OSI, with 6.0 mm implants exhibiting the largest increase, although differences were not statistically significant.

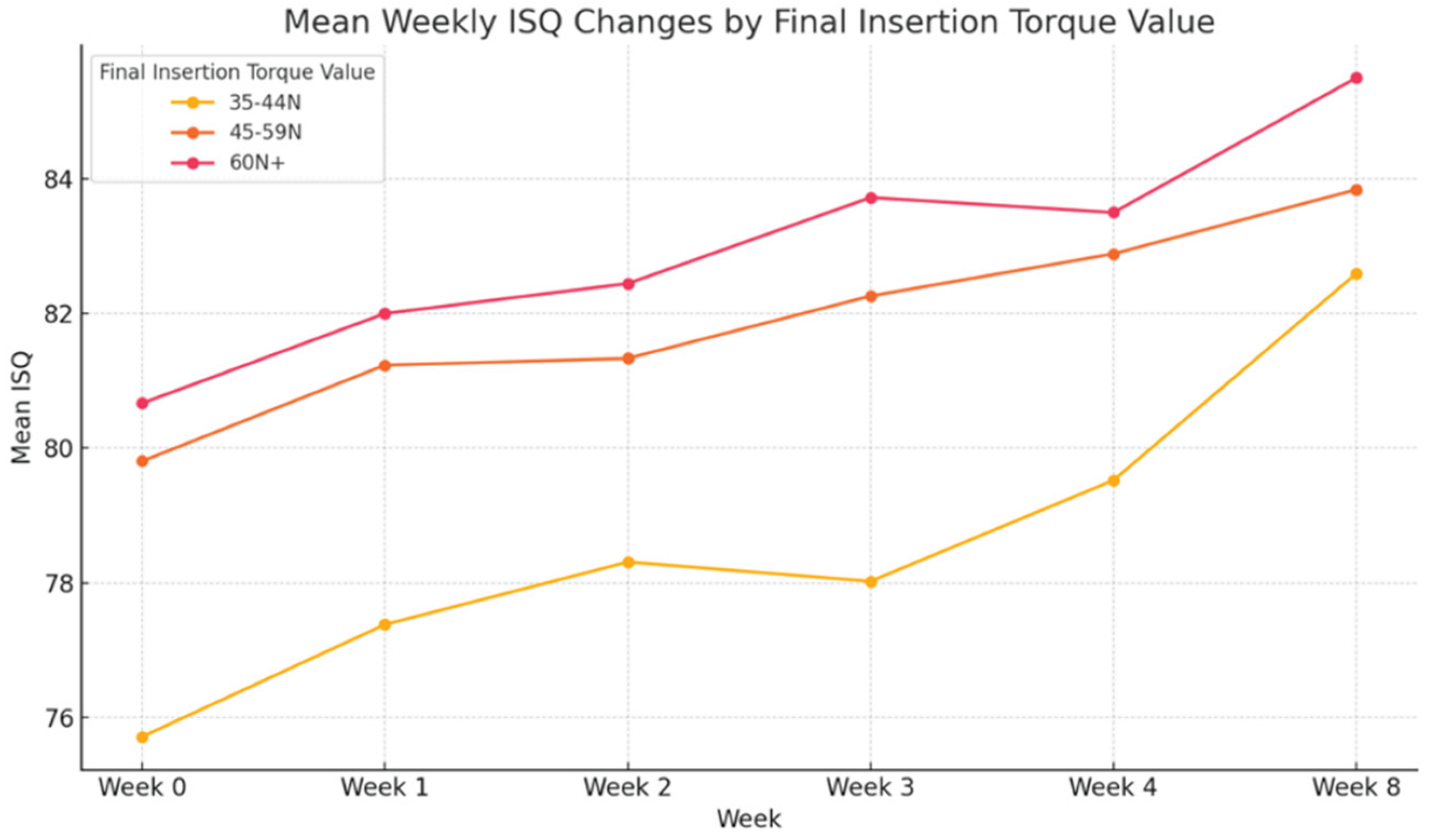

3.5. Final Insertion Torque Value

The correlation between final insertion torque and ISQ change was evaluated (

Figure 8,

Table 8). Implants were stratified into three groups: 35–44 N·cm, 45–59 N·cm, and ≥60 N·cm. Across all time points, higher torque values were associated with greater ISQ measurements. The ≥60 N·cm group consistently showed the highest stability, with mean ISQ increasing from 80.67 at placement to 85.50 at week 8. By contrast, the 35–44 N·cm group began with the lowest ISQ (75.71) and reached 82.60 by week 8. Although all groups demonstrated progressive stability gains, implants placed with higher torque exhibited faster and more predictable increases in ISQ, indicating a positive correlation between primary mechanical stability and early osseointegration. Statistically significant differences among groups were observed at weeks 0, 1, 3, and 4 (p < 0.05). However, interpretation of the ≥60 N·cm subgroup should be made cautiously due to its limited sample size (n=7).

4. Discussion

This retrospective single-arm cohort study quantitatively investigated the clinical efficacy of gas plasma treatment on dental implants by assessing changes in implant stability and the rate of osseointegration using the implant stability quotient (ISQ). Plasma activation aims to restore or enhance the biological activity of implant surfaces that may undergo biological aging during storage. The objective of this study was to validate, in a clinical setting, the beneficial effects of plasma-treated implants that have been consistently demonstrated in preclinical studies. As shown previously, animal experiments confirmed that plasma treatment accelerates peri-implant bone formation by introducing superhydrophilicity and removing hydrocarbon contaminants from titanium surfaces.

Plasma activation has also been proposed as a practical alternative to ultraviolet (UV)-based surface functionalization. While UV treatment can improve surface bioactivity, it is limited by higher costs, the need for crystalline packaging to permit UV penetration, and a prolonged activation process of at least three hours, making it unsuitable for chairside use [

4]. By contrast, plasma treatment delivers stronger surface energy, achieves more effective removal of organic contaminants, and can be applied immediately before implant placement—an important consideration given the rapid re-adsorption of hydrocarbons from ambient air [

27].

Implant stability is widely recognized as a reflective parameter of osseointegration [

28]. Assessing stability across multiple time points provides clinically relevant insights into the optimal healing period for individual patients. Although several methods exist for evaluating implant stability—including push-out and pull-out tests, removal torque analysis, percussion tests, and histological examination—resonance frequency analysis (RFA) is considered the most practical and non-invasive technique for routine clinical application [

29]. ISQ values ≥70 is generally accepted as indicative of sufficient stability for functional loading. However, because single ISQ values correlate poorly with bone quality, recent studies have emphasized the clinical importance of tracking ISQ changes over time rather than relying solely on isolated values [

30]. Consistent with this approach, the present study focused on longitudinal changes in ISQ, highlighting stability progression during the healing phase rather than point measurments alone.

A critical issue during healing phase is the potential occurrence of a “stability dip,” defined as a temporary decline in implant stability caused by the gradual loss of mechanical (primary) stability before biological (secondary) stability is fully established [

31]. Implants are particularly vulnerable to osseointegration failure during this period [

32], and therefore, conventional protocols advise against functional loading until the dip has resolved, limiting the feasibility of immediate or early loading [

33]. As stability dips are typically observed between the 2nd and 8th postoperative weeks, the present study was designed with an 8-week follow-up to detect any potential decline [

34].

Surface properties are thought to play a decisive role in the occurrence and magnitude of stability dips [

35]. Surface functionalization strategies such as plasma treatment enhance bone–implant integration and promote earlier biological stability, thereby compensating for the loss of mechanical stability [

11]. Indeed, prior reports have shown that surface-treated implants often do not exhibit a distinct stability dip [

11,

34], and one study confirmed that plasma treatment specifically reduces the likelihood of a dip and accelerates stability recovery if it occurs [

36]. Consistent with these findings, no pronounced stability dip was detected in the present study.

This study demonstrated a consistent time-dependent increase in implant stability following plasma surface treatment, as evidenced by steadily rising ISQ values over the 8-week healing period without any detectable dip. This finding suggests that plasma activation may enhance the early healing environment, potentially accelerating osseointegration and facilitating early functional loading. Notably, implants with relatively low initial stability (ISQi 65–74) exhibited the greatest ISQ gains and the highest OSI values, indicating that plasma treatment may be particularly beneficial in cases with suboptimal baseline conditions. Conversely, implants with very high primary stability (ISQi ≥85) showed minimal change, implying a ceiling effect in the context of already optimal bone-implant contact. Additionally, implants placed in the mandible demonstrated significantly higher stability and faster integration compared to those in the maxilla, which aligns with the known differences in bone quality between these regions. Shorter implants (≤10 mm) also showed greater improvement in ISQ, potentially reflecting a greater sensitivity to surface modifications. Although higher insertion torque was associated with improved stability outcomes—especially in the ≥60 N·cm group—further research with larger sample sizes is warranted to validate these findings. Overall, these results support the clinical utility of plasma surface treatment in enhancing early implant stability and suggest that its benefits may be most pronounced in challenging clinical scenarios.

Numerous studies have shown that primary implant stability strongly influences the development of overall stability during the healing phase [

34,

37,

38]. Implants with moderate baseline stability generally demonstrate progressive improvement, whereas those with very high initial stability may show minimal gains or even slight reductions over time [

37]. Specifically, implants with ISQ values below 60 typically exhibit substantial increases, while those with higher initial ISQ values (≥60) tend to demonstrate only minor changes or occasional declines [

39,

40]. In other words, implants placed in low-density bone often “catch up” in stability with those placed in denser bone during healing [

38]. Consistent with these reports, the present study confirmed that implants with the lowest primary ISQ (65-74) exhibited the greatest increase in stability over the 8-week observation period.

High initial stability is generally associated with elevated insertion torque, which, when excessive, may induce compression necrosis [

41]. This phenomenon arises from excessive mechanical stress at the bone–implant interface, compromising blood flow and potentially impairing early-phase healing [

42]. Furthermore, underpreparation of the osteotomy site can exacerbate this effect by causing irreversible microdamage to surrounding bone [

43]. These mechanisms may help explain the relatively limited ISQ gains observed in the high initial stability group in the present study.

To compensate for the absence of a control group in this single-arm study, relevant literature on untreated implants without post-packaging surface modification was reviewed for comparison. Suzuki et al. calculated osseointegration speed index (OSI) values from ISQ changes across multiple studies of untreated implant surfaces and reported OSI values generally below 1.0 [

33]. In contrast, plasma-activated implants in the present study demonstrated substantially higher OSI values (6.43 for ISQi 65–74 and 3.03 for ISQi 75–84). Moreover, the final ISQ values observed at week 8 (79.42–86.60) exceeded those previously reported for untreated implants, despite the shorter observation period [

33]. Taken together, these findings provide strong clinical support that plasma surface treatment accelerates and reinforces osseointegration, particularly in implants with lower initial stability.

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, as a retrospective analysis, the type of implant fixture could not be standardized, potentially introducing variability related to differences in implant design and surface characteristics. Second, preoperative cone-beam CT scans were not consistently obtained—particularly in straightforward posterior mandibular cases with adequate bone height—limiting the ability to objectively assess bone quality, which may have influenced outcomes. Third, the absence of a control group without plasma treatment represents a fundamental limitation, as it prevents direct evaluation of the specific contribution of plasma activation to implant stability and osseointegration. Future studies should incorporate standardized implant systems, comprehensive radiographic assessment, and controlled comparative designs to fully elucidate the sustained impact of plasma treatment on implant stability and clinical success.

5. Conclusions

This retrospective cohort study demonstrated that chairside plasma surface treatment using non-thermal atmospheric pressure plasma significantly improved early implant stability, as evidenced by progressive increases in ISQ values throughout the 8-week healing period without any observable stability dip. Plasma activation effectively enhanced the biological performance of SLA-based implant surfaces by removing hydrocarbon contaminants and restoring superhydrophilicity, thereby facilitating protein adsorption, cellular attachment, and early osteogenic activity. Notably, implants with lower initial stability (ISQi 65–74) showed the most pronounced improvements in ISQ and the highest OSI values. This suggests that plasma treatment is particularly advantageous in cases with less favorable initial conditions by promoting rapid osseointegration and enabling functional loading as early as four weeks postoperatively. Furthermore, increased stability gains in mandibular implants, shorter fixtures, and those with higher insertion torque values underscore the adaptability and broad applicability of plasma surface activation. These findings support the clinical utility of chairside plasma treatment as a promising surface enhancement modality to accelerate osseointegration and enable safe early functional loading in a variety of implant scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.-S.S.; methodology, investigation, resources, data curation, Y.-K.K. and H.-K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-K.K.; writing, review and editing, H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University Hospital of Daegu, with approval from the local university ethics committee (protocol code: IRB No. 2025-06-021, date of approval: 26 June 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author on request.

References

- Yeo, I.S. Modifications of dental implant surfaces at the micro- and nano-level for enhanced osseointegration. Materials 2020, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buser, D.; Schenk, R.K.; Steinemann, S.; Fiorellini, J.P.; Fox, C.H.; Stich, H. Influence of surface characteristics on bone integration of titanium implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1991, 25, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, T.S.; Jung, H.D.; Kim, S.; Moon, B.S.; Beak, J.; Park, C.; Song, J.; Kim, H.E. Multiscale porous titanium surfaces via a two-step etching process for improved mechanical and biological performance. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 12, 025008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jeon, H.J.; Jung, A.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; et al. Improvement of osseointegration efficacy of titanium implant through plasma surface treatment. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2022, 12, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Ogawa, T. The biological aging of titanium implants. Implant Dent. 2012, 21, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamikawa, H.; Att, W.; Ikeda, T.; Hirota, M.; Ogawa, T. Long-term progressive degradation of the biological capability of titanium. Materials 2016, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, S.R.; Lamghari, M.; Sampaio, P.; Moradas Ferreira, P.; Barbosa, M.A. Osteoblast adhesion and morphology on TiO₂ depends on the competitive preadsorption of albumin and fibronectin. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2008, 84, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Att, W.; Hori, N.; Takeuchi, M.; Ouyang, J.; Yang, Y.; Anpo, M.; Ogawa, T. Time dependent degradation of titanium osteoconductivity: An implication of biological aging of implant materials. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 5352–5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshinari, M.; Matsuzaka, K.; Inoue, T.; Oda, Y.; Shimono, M. Bio-functionalization of titanium surfaces for dental implants. Mater. Trans. 2002, 43, 2494–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujita, H.; Nishizaki, H.; Miyake, A.; Takao, S.; Komasa, S. Effect of plasma treatment on titanium surface on the tissue surrounding implant material. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strnad, J.; Urban, K.; Povysil, C.; Strnad, Z. Secondary stability assessment of titanium implants with an alkali-etched surface: A resonance frequency analysis study in beagle dogs. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2008, 23, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coelho, P.G.; Giro, G.; Teixeira, H.S.; Marin, C.; Witek, L.; Thompson, V.P.; Tovar, N.; Silva, N.R.F.A. Argon based atmospheric pressure plasma enhances early bone response to rough titanium surfaces. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2012, 100, 1901–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, P.; Chappé, J.M.; Fonseca, C.; Vaz, F. Plasma surface modification of polycarbonate and poly(propylene) substrates for biomedical electrodes. Plasma Process. Polym. 2010, 7, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Park, J.K.; Choi, Y.C. Effect of N₂, Ar, and O₂ plasma treatments on surface properties of metals. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 053301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, L.; Zhang, T.; Ren, G.; Yang, Z. Oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by nanosized titanium dioxide in PC12 cells. Toxicology 2010, 267, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ujino, D.; Nishizaki, H.; Higuchi, S.; Komasa, S.; Okazaki, J. Effect of plasma treatment of titanium surface on biocompatibility. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.S.; Cho, W.T.; Lee, J.H.; Joo, J.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Lim, Y.; et al. Prospective randomized controlled clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of ACTILINK plasma treatment for promoting osseointegration and bone regeneration in dental implants. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.W.; Park, J.H.; Kim, Y.H. Effect of atmospheric pressure plasma treatment on the titanium surface and tissue compatibility. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 2257. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Yang, M.; Ma, K.; Zhang, Q.; Bai, N.; Liu, Y. Improvement of implant osseointegration through nonthermal Ar/O₂ plasma. Dent. Mater. J. 2023, 42, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minati, L.; Migliaresi, C.; Lunelli, L.; Viero, G.; Dalla Serra, M.; Speranza, G. Plasma assisted surface treatments of biomaterials. Biophys. Chem. 2017, 229, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, P.; Farrar, D.; Perry, C.C. Interpretation of protein adsorption: Surface-induced conformational changes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 8168–8173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaki, C.; Schneider, G.B.; Zaharias, R.; Seabold, D.; Stanford, C. Effects of implant surface microtopography on osteoblast gene expression. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2005, 16, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plasmapp Inc. ACTILINK product specification sheet. 2024. Available online: https://www.plasmapp.com (accessed on 2025-08-06).

- Nevins, M.; Chen, C.Y.; Parma Benfenati, S.; Kim, D.M.; et al. Gas plasma treatment improves titanium dental implant osseointegration: a preclinical in vivo experimental study. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrektsson, T.; Wennerberg, A. On osseointegration in relation to implant surfaces. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megagen Implant Co., Ltd.; MEGA ISQ™ user manual. Version 2.0. Daegu, South Korea: Megagen Implant Co., Ltd.; 2021. Available online: https://megagen.com/manuals/megaisq (accessed on 2025-08-06).

- Berger, M.B.; Bosh, K.B.; Cohen, D.J.; Boyan, B.D.; Schwartz, Z. Benchtop plasma treatment of titanium surfaces enhances cell response. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunski, J.B. Biomechanical factors affecting the bone–dental implant interface. Clin. Mater. 1992, 10, 153–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsumi, M.; Park, S.H.; Wang, H.L. Methods used to assess implant stability: Current status. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2007, 22, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fu, M.W.; Fu, E.; Lin, F.G.; Chang, W.J.; Hsieh, Y.D.; Shen, E.C. Correlation between resonance frequency analysis and bone quality assessments at dental implant recipient sites. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2017, 32, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sennerby, L.; Meredith, N. Implant stability measurements using resonance frequency analysis: Biological and biomechanical aspects and clinical implications. Periodontol. 2000 2008, 47, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra, S.; Wood, M.C.; Taylor, T.D. Early wound healing around endosseous implants: A review of the literature. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2005, 20, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Ogawa, T. Implant stability change and osseointegration speed of immediately loaded photofunctionalized implants. Implant Dent. 2013, 22, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balshi, S.F.; Allen, F.D.; Wolfinger, G.J.; Balshi, T.J. A resonance frequency analysis assessment of maxillary and mandibular immediately loaded implants. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2005, 20, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Simůnek, A.; Kopečka, D.; Brazda, T.; Strnad, I.; Čapek, L.; Slezák, R. Development of implant stability during early healing of immediately loaded implants. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2012, 27, 619–627. [Google Scholar]

- Stacchi, C.; Rapani, A.; Montanari, M.; Martini, R.; Lombardi, T. Effect of vacuum plasma activation on early implant stability: A single-blind split-mouth randomized clinical trial. Preprints.org 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simunek, A.; Strnad, J.; Kopecka, D.; Brazda, T.; Pilathadka, S.; Chauhan, R.; et al. Changes in stability after healing of immediately loaded dental implants. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2010, 25, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Friberg, B.; Sennerby, L.; Meredith, N.; Lekholm, U. A comparison between cutting torque and resonance frequency measurements of maxillary implants: A 20-month clinical study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1999, 28, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glauser, R.; Sennerby, L.; Meredith, N.; Lundgren, A.; Gottlow, J.; Hämmerle, C.H.F. Resonance frequency analysis of implants subjected to immediate or early functional occlusal loading: Successful vs. failing implants. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2004, 15, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makary, C.; Rebaudi, A.; Sammartino, G.; Naaman, N. Implant primary stability determined by resonance frequency analysis: Correlation with insertion torque, histologic bone volume, and torsional stability at 6 weeks. Implant Dent. 2012, 21, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do Vale Souza, J.P.; de Moraes Melo Neto, C.L.; Piacenza, L.T.; et al. Relation between insertion torque and implant stability quotient: a clinical study. Eur. J. Dent. 2021, 15, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, R.; Sasi, A.; Mohamed, S.C.; Joseph, S.P. “Compression Necrosis” – a cause of concern for early implant failure? Case report and review of literature. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2024, 16, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocchero, M.; Toia, M.; Cecchinato, D.; Becktor, J.P.; Coelho, P.G.; Biomechinical, J.R. Biologic, and clinical outcomes of undersized implant surgical preparation: a systematic review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2016, 31, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

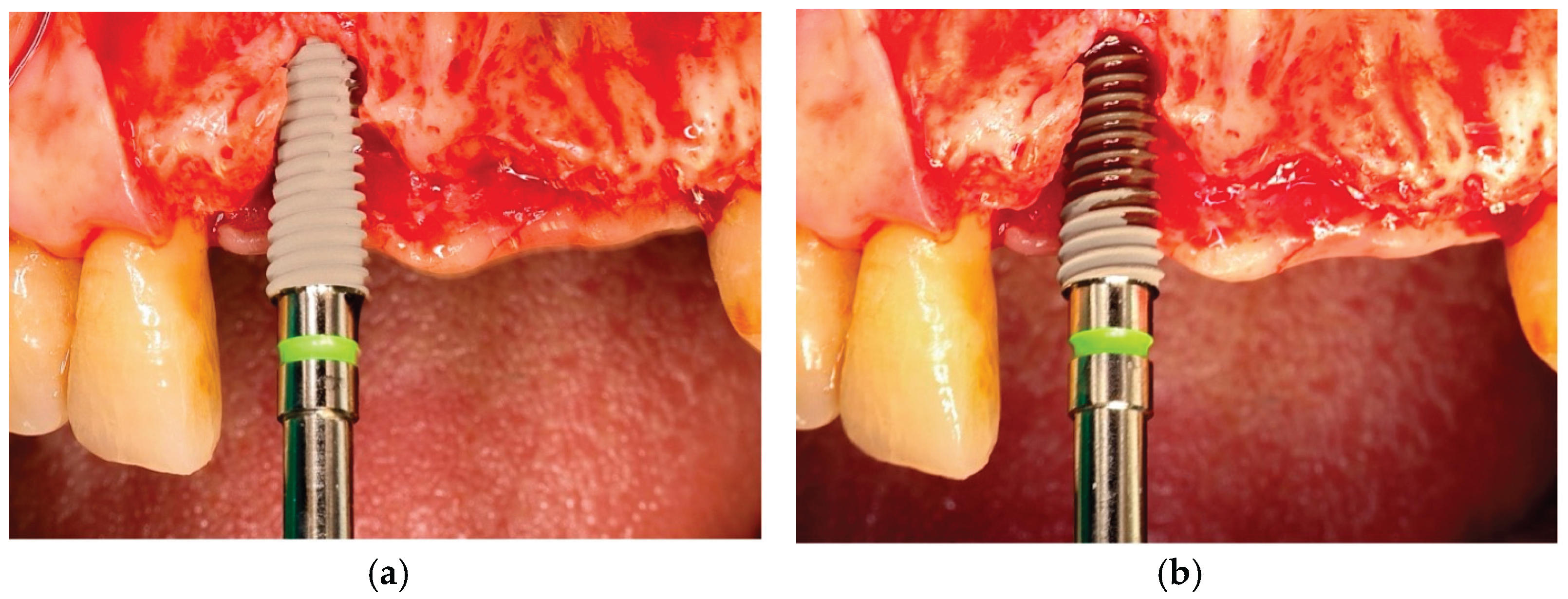

Figure 1.

Clinical images of (a) untreated implant versus; (b) plasma treated implant. Plasma enhanced hemocompatibility, resulting in blood soaking appearance on implants.

Figure 1.

Clinical images of (a) untreated implant versus; (b) plasma treated implant. Plasma enhanced hemocompatibility, resulting in blood soaking appearance on implants.

Figure 2.

Individual implant stability quotient (ISQ) values of plasma-treated implants at baseline (placement) and after 8 weeks of healing. Each line represents the transition of a single implant from its initial ISQ (ISQi) to the final ISQ at week 8 (ISQ8).

Figure 2.

Individual implant stability quotient (ISQ) values of plasma-treated implants at baseline (placement) and after 8 weeks of healing. Each line represents the transition of a single implant from its initial ISQ (ISQi) to the final ISQ at week 8 (ISQ8).

Figure 3.

Mean implant stability quotient (ISQ) values of plasma-treated implants during the 8-week healing period. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. A significant time-dependent increase in ISQ values was observed, with the greatest gain occurring during the first three weeks. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared with baseline (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Mean implant stability quotient (ISQ) values of plasma-treated implants during the 8-week healing period. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. A significant time-dependent increase in ISQ values was observed, with the greatest gain occurring during the first three weeks. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared with baseline (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Temporal development of implant stability quotient (ISQ) values according to the initial stability groups: ISQi 65–74 (blue), ISQi 75–84 (green), and ISQi ≥85 (orange). Values represent mean ISQ at each time point. Standard deviations are provided in

Table 4. Statistical significance was evaluated using repeated-measures ANOVA followed by paired t-test with Bonferroni correction; * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus baseline (at placement).

Figure 4.

Temporal development of implant stability quotient (ISQ) values according to the initial stability groups: ISQi 65–74 (blue), ISQi 75–84 (green), and ISQi ≥85 (orange). Values represent mean ISQ at each time point. Standard deviations are provided in

Table 4. Statistical significance was evaluated using repeated-measures ANOVA followed by paired t-test with Bonferroni correction; * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus baseline (at placement).

Figure 5.

Changes in implant stability quotient (ISQ) over time by primary stability at placement. (a) ISQi 65–74: steepest increase, significant from week 3 onward (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001); (b) ISQi 75–84: gradual but significant increase from week 1 onward; (c) ISQi ≥85: no statistically significant change, values remained consistently high.

Figure 5.

Changes in implant stability quotient (ISQ) over time by primary stability at placement. (a) ISQi 65–74: steepest increase, significant from week 3 onward (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001); (b) ISQi 75–84: gradual but significant increase from week 1 onward; (c) ISQi ≥85: no statistically significant change, values remained consistently high.

Figure 6.

Weekly changes in implant stability quotient (ISQ) of plasma-treated implants placed in (a) the maxilla and (b) the mandible. Both groups showed significant increases during healing, with greater stability gains observed in the mandible (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Weekly changes in implant stability quotient (ISQ) of plasma-treated implants placed in (a) the maxilla and (b) the mandible. Both groups showed significant increases during healing, with greater stability gains observed in the mandible (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Figure 8.

Mean weekly implant stability quotient (ISQ) changes stratified by final insertion torque. Higher torque values showed greater and more consistent stability gains.

Figure 8.

Mean weekly implant stability quotient (ISQ) changes stratified by final insertion torque. Higher torque values showed greater and more consistent stability gains.

Table 1.

Patient and implant data. The distribution of torque value at initial placement and implantation site is shown.

Table 1.

Patient and implant data. The distribution of torque value at initial placement and implantation site is shown.

| Patients |

Implants |

Initial torque (N·cm) |

| Number |

Age range |

Total Number |

Maxilla |

Mandible |

35N-40N |

45N-50N |

>50N |

| 47 |

38-86 |

73 |

28 |

45 |

14 |

52 |

7 |

Table 2.

Mean ISQs ± SDs during the healing period.

Table 2.

Mean ISQs ± SDs during the healing period.

| |

Time (week) |

| Placement |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

8 |

| ISQ |

78.97±5.52 |

80.39±5.23 |

80.78±4.78 |

81.54±5.28 |

82.31±4.64 |

83.74±4.36 |

Table 3.

Results of t-test analysis comparing ISQ values at baseline and at week 8 across three initial ISQ categories.

Table 3.

Results of t-test analysis comparing ISQ values at baseline and at week 8 across three initial ISQ categories.

| Initial Stability Range |

Number of Implants |

At Placement |

At Week 8 |

Change (ΔISQ) |

OSI |

| ISQi 65-74 |

9 |

69.78 ± 3.06 |

79.42 ± 4.23 |

9.64 ± 4.65***

|

6.43 ± 3.10 |

| ISQi 75-84 |

54 |

79.65 ± 2.93 |

84.20 ± 3.98 |

4.55 ± 3.73***

|

3.03 ± 2.48 |

| ISQi ≥85 |

10 |

86.57 ± 2.32 |

86.60 ± 2.62 |

0.03 ± 3.10 |

NA |

Table 4.

Mean ISQs ± SDs in each group over time.

Table 4.

Mean ISQs ± SDs in each group over time.

| |

Time (week) |

| Groups |

Placement |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

8 |

| ISQi 65-74 |

69.77±3.06 |

72.14±2.74 |

73.61±3.34 |

73.72±4.29 |

76.81±3.14 |

79.42±4.23 |

| ISQi 75-84 |

79.65±2.93 |

81.22±3.46 |

81.32±2.97 |

82.29±3.49 |

82.58±3.64 |

84.20±3.98 |

| ISQi ≥85 |

86.57±2.32 |

86.07±3.50 |

86.60±3.55 |

87.10±3.71 |

87.53±3.95 |

86.60±2.62 |

Table 5.

Results of t-test analysis comparing ISQ values at baseline and at week 8 in the maxilla and mandible.

Table 5.

Results of t-test analysis comparing ISQ values at baseline and at week 8 in the maxilla and mandible.

| Jaw location |

Number of Implants |

At Placement |

At Week 8 |

Change (ΔISQ) |

OSI |

| Maxilla |

28 |

77.88 ± 4.13 |

81.96 ± 4.04 |

4.08 ± 3.96***

|

0.51 ± 0.49 |

| Mandible |

45 |

79.66 ± 6.18 |

84.85 ± 4.23 |

5.19 ± 4.97***

|

0.65 ± 0.62 |

Table 6.

Results of t-test analysis of changes in ISQ values according to implant length.

Table 6.

Results of t-test analysis of changes in ISQ values according to implant length.

| Length |

Number of Implants |

At Placement |

At Week 8 |

Change (ΔISQ) |

OSI |

| ≤10mm |

40 |

79.72 ± 4.76 |

85.05 ± 4.31*

|

5.33 ± 4.77 |

0.67 ± 0.60 |

| 11mm≤13mm |

33 |

78.08 ± 6.29 |

82.16 ± 3.93*

|

4.08 ± 4.37 |

0.51 ± 0.54 |

Table 7.

Results of t-test analysis of changes in ISQ values according to implant fixture diameter.

Table 7.

Results of t-test analysis of changes in ISQ values according to implant fixture diameter.

| Diameter |

Number of Implants |

At Placement |

At Week 8 |

Change (ΔISQ) |

OSI |

| 4.0 |

11 |

78.15 ± 5.36 |

81.36 ± 3.75 |

3.21 ± 4.96 |

0.40 ± 0.62 |

| 4.5 |

21 |

79.84 ± 4.55 |

83.43 ± 3.56 |

3.59 ± 3.12 |

0.45 ± 0.39 |

| 5.0 |

38 |

78.72 ± 6.25 |

84.25 ± 4.70 |

5.54 ± 5.01 |

0.69 ± 0.63 |

| 6.0 |

3 |

79.22 ± 3.24 |

88.22 ± 3.34 |

9.00 ± 3.61 |

1.13 ± 0.45 |

Table 8.

Comparison of ISQ value changes by final insertion torque value using t-test analysis. .

Table 8.

Comparison of ISQ value changes by final insertion torque value using t-test analysis. .

| Final insertion torque value |

Number of Implants |

At Placement |

At Week 8 |

Change (ΔISQ) |

| 35-44N·cm |

14 |

75.14 ± 5.53 |

82.60 ± 3.95*

|

5.33 ± 4.77*

|

| 45-59N·cm |

52 |

79.66 ± 5.44 |

83.87 ± 4.56*

|

4.08 ± 4.37*

|

| ≥60N·cm |

7 |

80.43 ± 4.08 |

85.14 ± 3.53*

|

4.71 ± 3.94*

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).