Submitted:

03 September 2025

Posted:

04 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database

2.2. Population

2.3. Variables

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Anatomic Characteristics

3.3. Procedure Details

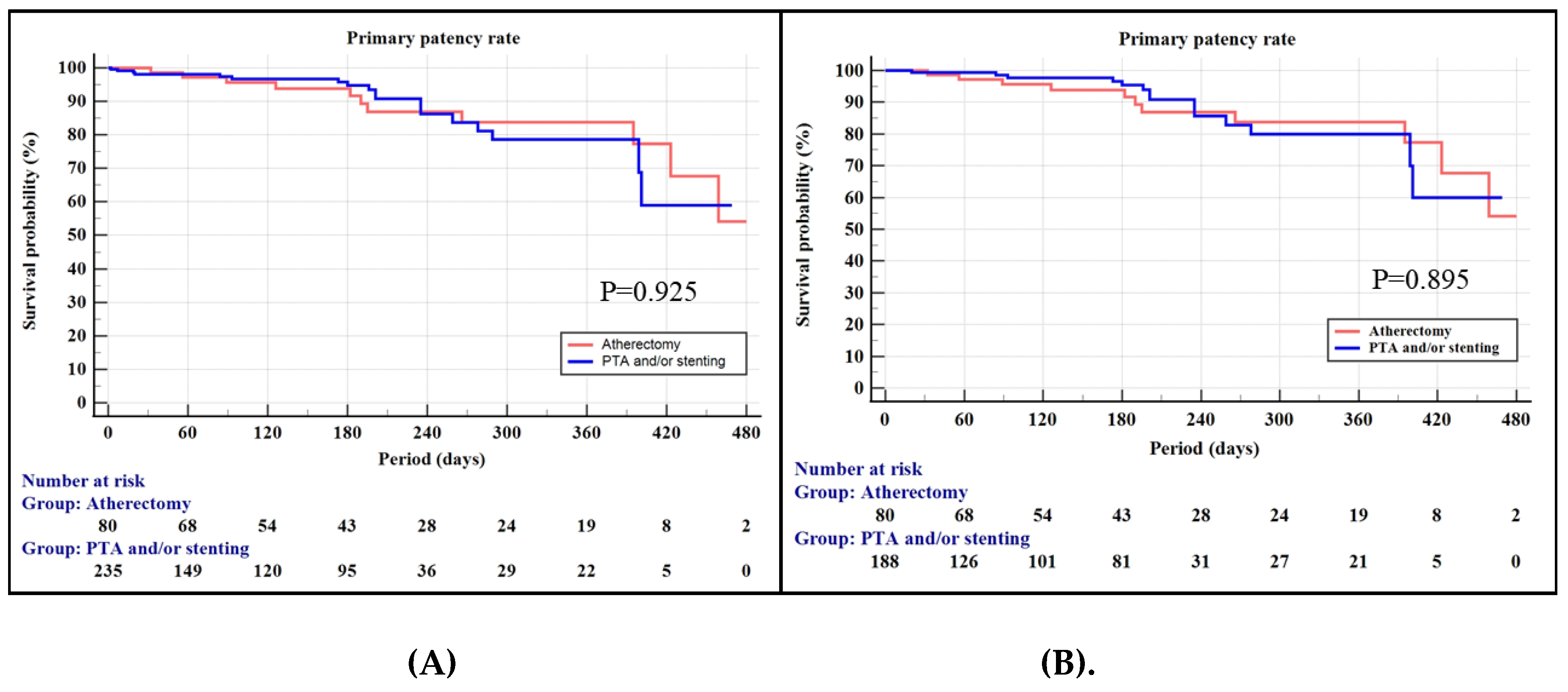

3.4. Primary Patency Rate of the Propensity-Matched Cohorts

3.5. Functional and Safety Outcomes

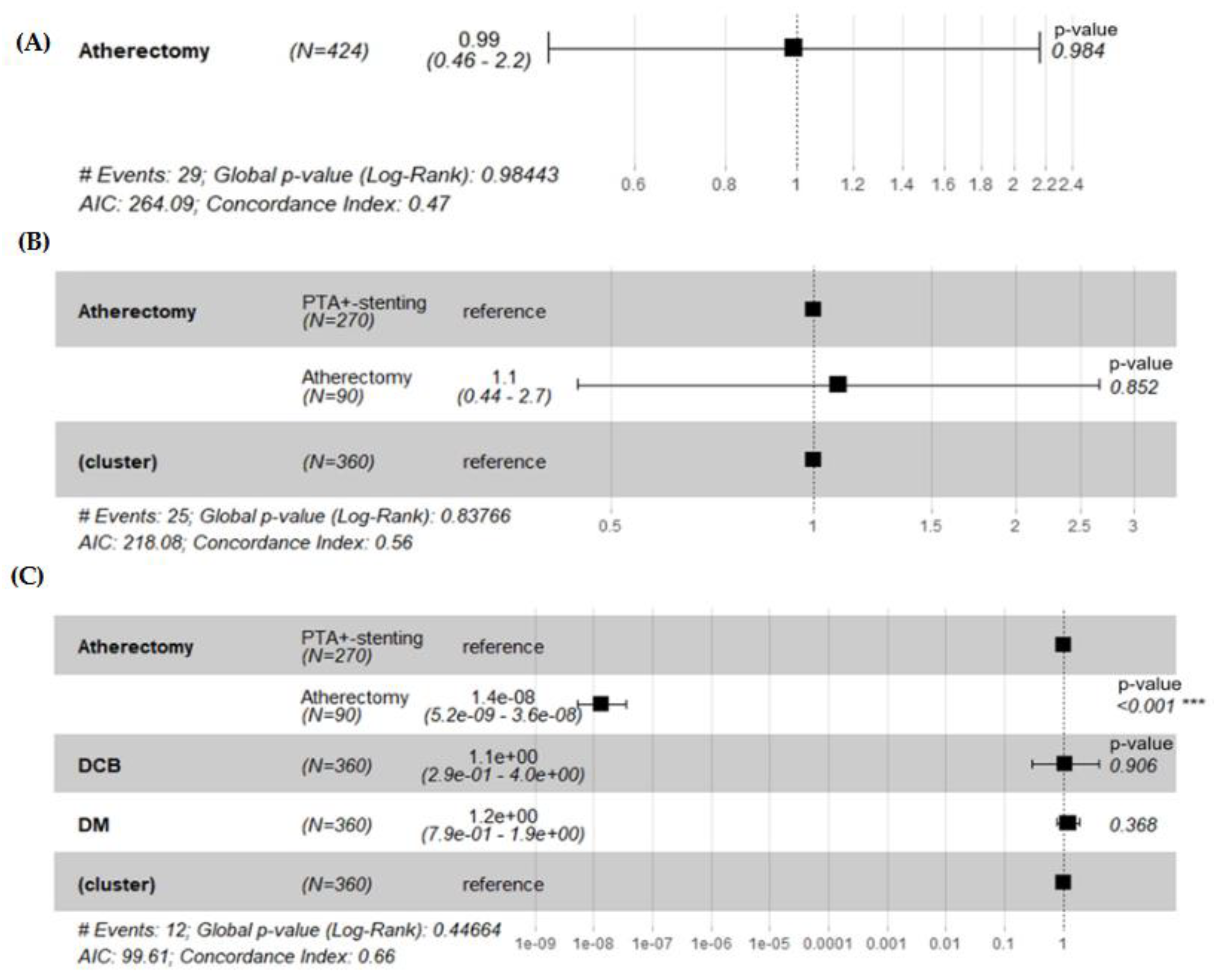

3.6. Hazard Ratio

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLTI | Chronic limb-threatening ischemia |

| PA | Percutaneous atherectomy |

| DCB | drug-coated balloon |

| US | United States |

| KSVS | Korean Society for Vascular Surgery |

| WIQ | Walking Impairment Questionnaire |

| TASC | TransAtlantic InterSociety Consensus |

| SFA | Superficial femoral artery |

| CT | Computed tomogram angiography |

| MRA | Magnetic resonance image angiography |

| ABI | Ankle-Brachial index |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| EPD | Embolic protection device |

| PPR | Primary patency rates |

| TLR | Target lesion revascularization |

| IVUS | Intravascular ultrasound |

| EVT | Endovascular treatment |

References

- Conte, M.S.; Pomposelli, F.B.; Clair, D.G.; Geraghty, P.J.; McKinsey, J.F.; Mills, J.L.; Moneta, G.L.; Murad, M.H.; Powell, R.J.; Reed, A.B.; et al. Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines for atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the lower extremities: Management of asymptomatic disease and claudication. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 61 (Suppl. 3), 2S–41S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation, E.S.; Tendera, M.; Aboyans, V.; Bartelink, M.-L.; Baumgartner, I.; Clément, D.; Collet, J.-P.; Cremonesi, A.; De Carlo, M.; Erbel, R.; et al. ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral artery diseases: Document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries * The Task Force on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Artery Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Hear. J. 2011, 32, 2851–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thukkani, A.K.; Kinlay, S. Endovascular Intervention for Peripheral Artery Disease. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1599–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korosoglou, G.; Giusca, S.; Andrassy, M.; Lichtenberg, M. The Role of Atherectomy in Peripheral Artery Disease: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Vasc. Endovasc. Rev. 2019, 2, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnowski, A.; Lindquist, J.D.; Herzog, E.C.; Jensen, A.; Dybul, S.L.; Trivedi, P.S. Changes in the National Endovascular Management of Femoropopliteal Arterial Disease: An Analysis of the 2011–2019 Medicare Data. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2022, 33, 1153–1158.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noory, E.; Böhme, T.; Steinhauser, Y.; Salm, J.; Beschorner, U.; de Forest, A.; Bollenbacher, R.; Westermann, D.; Zeller, T. Acute and Mid-Term Results of Atherectomy in Femoropopliteal Lesions. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.; Zhou, Y.; Paty, P.S.; Teymouri, M.; Jafree, K.; Bakhtawar, H.; Hnath, J.; Feustel, P. Percutaneous common femoral artery interventions using angioplasty, atherectomy, and stenting. J. Vasc. Surg. 2016, 64, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnabatidis, D.; Katsanos, K.; Spiliopoulos, S.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Kagadis, G.C.; Siablis, D. Incidence, Anatomical Location, and Clinical Significance of Compressions and Fractures in Infrapopliteal Balloon-Expandable Metal Stents. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2009, 16, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taneva, G.T.; Pitoulias, A.G.; Avranas, K.; Kazemtash, M.; Abu Bakr, N.; Dahi, F.; Donas, K.P. Midterm outcomes of rotational atherectomy-assisted endovascular treatment of severe peripheral arterial disease. J. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 79, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, Q.; Pu, H.; Qin, J.; Wang, X.; Ye, K.; Lu, X. Atherectomy Combined with Balloon Angioplasty versus Balloon Angioplasty Alone for de Novo Femoropopliteal Arterial Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2021, 62, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Hwang, D.; Yun, W.-S.; Huh, S.; Kim, H.-K. Effectiveness of Atherectomy and Drug-Coated Balloon Angioplasty in Femoropopliteal Disease: A Comprehensive Outcome Study. Vasc. Spéc. Int. 2024, 40, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Wang, H.; Ding, W.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Z. Atherectomy plus drug-coated balloon versus drug-coated balloon only for treatment of femoropopliteal artery lesions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vascular 2021, 29, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehara, A.; Mintz, G.S.; Shimshak, T.M.; Ricotta, J.J.; Ramaiah, V.; Foster, M.T.; Davis, T.P.; Gray, W.A. Intravascular ultrasound evaluation of JETSTREAM atherectomy removal of superficial calcium in peripheral arteries. EuroIntervention 2015, 11, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazu, Y.; Fujihara, M.; Takahara, M.; Kurata, N.; Nakata, A.; Yoshimura, H.; Ito, T.; Fukunaga, M.; Kozuki, A.; Tomoi, Y. Intravascular ultrasound-based decision tree model for the optimal endovascular treatment strategy selection of femoropopliteal artery disease—results from the ONION Study-. CVIR Endovasc. 2022, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, M.; Kozuki, A.; Tsubakimoto, Y.; Takahara, M.; Shintani, Y.; Fukunaga, M.; Iwasaki, Y.; Nakama, T.; Yokoi, Y. Lumen Gain After Endovascular Therapy in Calcified Superficial Femoral Artery Occlusive Disease Assessed by Intravascular Ultrasound (CODE Study). J. Endovasc. Ther. 2019, 26, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakura, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Taniguchi, Y.; Tsurumaki, Y.; Momomura, S.-I.; Fujita, H. Intravascular ultrasound enhances the safety of rotational atherectomy. Cardiovasc. Revascularization Med. 2018, 19, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, T.; Fujita, T.; Kashima, Y.; Tsujimoto, M.; Otake, R.; Kasai, Y.; Sato, K. Fracking compared to conventional balloon angioplasty alone for calcified common femoral artery lesions using intravascular ultrasound analysis: 12-month results. CVIR Endovasc. 2023, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-H.; Katsetos, M.; Dahal, K.; Azrin, M.; Lee, J. Use of rotational atherectomy for reducing significant dissection in treating de novo femoropopliteal steno-occlusive disease after balloon angioplasty. 15. [CrossRef]

- Abusnina, W.; Al-Abdouh, A.; Radaideh, Q.; Kanmanthareddy, A.; Shishehbor, M.H.; White, C.J.; Ben-Dor, I.; Shammas, N.W.; Nanjundappa, A.; Lichaa, H.; et al. Atherectomy Plus Balloon Angioplasty for Femoropopliteal Disease Compared to Balloon Angioplasty Alone: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaar, C.I.O.; Shebl, F.; Sumpio, B.; Dardik, A.; Indes, J.; Sarac, T. Distal embolization during lower extremity endovascular interventions. J. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 66, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shammas, N.W.; Dippel, E.J.; Coiner, D.; Shammas, G.A.; Jerin, M.; Kumar, A. Preventing Lower Extremity Distal Embolization Using Embolic Filter Protection:Results of the PROTECT Registry. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2008, 15, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, B.C.; Oderich, G.S.; Fleming, M.D.; Misra, S.; Duncan, A.A.; Kalra, M.; Cha, S.; Gloviczki, P. Clinical significance of embolic events in patients undergoing endovascular femoropopliteal interventions with or without embolic protection devices. J. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 59, 359–367.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Quan, J.; Dong, J.; Ding, N.; Han, Y.; Cong, L.; Lin, Y.; Liu, J. Comparison of mid-outcome among bare metal stent, atherectomy with or without drug-coated balloon angioplasty for femoropopliteal arterial occlusion. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, B.H.; Sullivan, T.M.; Childs, M.B.; Young, J.R.; Olin, J.W. High incidence of restenosis/reocclusion of stents in the percutaneous treatment of long-segment superficial femoral artery disease after suboptimal angioplasty. J. Vasc. Surg. 1997, 25, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gökgöl, C.; Diehm, N.; Kara, L.; Büchler, P. Quantification of Popliteal Artery Deformation During Leg Flexion in Subjects With Peripheral Artery Disease: A Pilot Study. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2013, 20, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, H.; Fereydooni, A.; Zhuo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tonnessen, B.H.; Guzman, R.J.; Chaar, C.I.O. Comparison of Atherectomy to Balloon Angioplasty and Stenting for Isolated Femoropopliteal Revascularization. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 69, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, R.; Puckridge, P.; Spark, J.; Delaney, C. The Impact of Intravascular Ultrasound on Femoropopliteal Artery Endovascular Interventions: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 76, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics |

All (N = 424) |

Atherectomy (n = 90) |

PTA± Stenting (n = 334) |

P value |

| Age, years | 72 (66–78) | 69 (64–75) | 72 (66–79) | 0.016 |

| Male gender | 345 (81.4) | 77 (85.6) | 268 (80.2) | 0.137 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23 (21–25) | 23 (22–25) | 23 (21–25) | 0.306 |

| Hypertension | 329 (77.6) | 71 (78.9) | 258 (77.2) | 0.999 |

| Diabetes | 266 (62.7) | 56 (62.2) | 210 (64.8) | 0.709 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 136 (32.1) | 26 (29.5) | 110 (34.0) | 0.523 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 200 (48.3) | 45 (50.0) | 155 (47.8) | 0.722 |

| Coronary artery disease | 139 (34.2) | 33 (36.7) | 106 (33.5) | 0.615 |

| Pulmonary disease | 118 (29.3) | 39 (43.3) | 79 (25.2) | 0.001 |

| Smoking Ex-smoker Current smoker |

43 (10.4) 124 (29.2) |

3 (3.4) 28 (31.5) |

40 (12.3) 96 (29.4) |

0.651 |

| Medication Antiplatelet Anticoagulant |

269 (63.4) 38 (9.0) |

64 (71.1) 9 (10.0) |

205 (61.4) 29 (8.7) |

0.001 0.001 |

| Rutherford category Claudication Rest pain Minor tissue loss Major tissue loss |

167 (39.4) 142 (23.5) 62 (14.6) 53 (12.5) |

58 (64.4) 27 (30.0) 4 (4.4) 1 (1.1) |

109 (31.7) 125 (36.3) 58 (16.9) 52 (14.5) |

<0.001 |

| WIQ score | 51 (33–66) | 55 (37–69) | 50 (31–64) | 0.106 |

| ASA classification | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 0.125 |

| Characteristics |

All (N = 424) |

Atherectomy (n = 90) |

PTA± Stenting (n = 334) |

P value |

| Lesion type De novo In-stent restenosis Re-intervention |

333 (78.5) 41 (9.7) 39 (9.2) |

69 (76.7) 7 (7.8) 7 (7.8) |

264 (79.0) 34 (10.2) 32 (9.6) |

0.725 |

| Lesion site Proximal SFA Mid-SFA Distal SFA P1 P2 P3 |

190 (44.8) 217 (51.2) 204 (48.1) 117 (27.6) 60 (14.2) 35 (8.3) |

50 (55.6) 45 (50.0) 48 (53.3) 29 (32.2) 13 (14.4) 6 (6.7) |

140 (41.9) 172 (51.5) 156 (46.7) 88 (26.3) 47 (14.1) 29 (8.7) |

0.745 |

| TASC classification TASC A TASC B TASC C TASC D |

77 (18.2) 198 (46.7) 65 (15.3) 64 (15.1) |

17 (18.9) 42 (46.7) 16 (17.8) 14 (15.6) |

60 (18.0) 156 (46.7) 49 (14.7) 50 (15.0) |

0.684 |

| Calcium grade No calcification Circumference 1˚~89˚ Circumference 90˚~179˚ Circumference 180˚~269˚ Circumference 270˚~360˚ |

91 (21.5) 82 (19.3) 42 (9.9) 49 (11.6) 114 (26.9) |

16 (17.8) 17 (18.9) 8 (8.9) 11 (12.2) 34 (37.8) |

75 (22.5) 65 (19.5) 34 (10.2) 38 (11.4) 80 (24.0) |

0.063 |

| Concomitant inflow lesions None Acute Chronic |

288 (67.9) 59 (13.9) 77 (18.2) |

67 (74.4) 14 (15.6) 9 (10.0) |

221 (66.2) 45 (13.5) 68 (20.4) |

0.101 |

| Concomitant outflow lesions None Acute Chronic |

230 (54.2) 95 (22.4) 99 (23.3) |

53 (58.9) 19 (21.1) 18 (20.0) |

177 (53.0) 76 (22.8) 81 (24.3) |

0.192 |

| Characteristics |

All (N = 424) |

Atherectomy (n = 90) |

PTA± Stenting (n = 334) |

P value |

| Use of re-entry device | 5 (1.2) | 0 | 5 (1.5) | 0.589 |

| Balloon diameter (n = 242) 4-5.5 mm 6-7 mm |

159 (65.7) 83 (34.3) |

11 (45.8) 13 (54.2) |

148 (67.9) 70 (32.1) |

0.041 |

| Balloon inflation pressure (n = 118) < 10 atm 10-15 atm > 15-20 atm |

48 (40.7)) 66 (55.9) 4 (3.4) |

1 (7.1) 12 (85.7) 1 (7.1) |

47 (45.2) 54 (51.9) 3 (2.9) |

0.007 |

| Residual stenosis (n = 211) < 30% 30~50% > 50% |

192 (91.0) 14 (6.6) 5 (2.4) |

16 (84.2)03 (15.8) |

176 (91.7) 14 (7.3) 2 (1.0) |

0.017 |

| Use of the drug-coated balloon | 180 (42.5) | 53 (58.9) | 127 (38.0) | < 0.001 |

| Stent placement | 148 (34.9) | 3 (3.3) | 145 (43.4) | < 0.001 |

| Stent diameter 4 mm 5 mm 6 mm 7 mm |

2 (1.4) 33 (22.3) 99 (66.9) 14 (9.5) |

003 (100)0 |

2 (1.4) 33 (22.8) 96 (66.2) 14 (9.7) |

0.646 |

| Use of embolic protection device SpiderFX Emboshield |

83 (19.6) 77 (92.8) 6 (7.2) |

83 (92.2) 77 (92.8) 6 (7.2) |

000 | < 0.001 |

| Use of closure device | 201 (47.4) | 72 (80.0) | 129 (38.6) | < 0.001 |

| Characteristics |

Atherectomy (n = 90) |

PTA± Stenting (n = 270) |

P value |

| Age, years | 69 (64–75) | 71 (66–79) | 0.066 |

| Male gender | 77 (85.6) | 215 (79.6) | 0.137 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.2 (21.6–25.0) | 22.7 (20.6–25.0) | 0.294 |

| Hypertension Controlled with 1 drug Controlled with 2 drugs Requires more than two drugs or is uncontrolled |

26 (28.9) 30 (33.3) 15 (16.7) |

102 (37.8) 80 (29.6) 29 (10.7) |

0.159 |

| Diabetes Mellitus Controlled by oral drug Controlled by insulin Type I diabetes or uncontrolled |

34 (14.4) 6 (6.7) 37 (41.1) |

94 (34.8) 19 (7.0) 65 (24.1) |

0.052 |

| Smoking Ex-smoker Current smoker (< 1 pack/day) Current smoker (  1 pack/day) 1 pack/day) |

3 (3.4) 14 (15.7) 14 (15.7) |

29 (10.7) 44 (16.3) 35 (13.0) |

0.936 |

| Indication Intermittent claudication Rest pain Minor tissue loss Major tissue loss |

49 (54.4) 34 (37.8) 5 (4.7) 2 (2.2) |

118 (43.7) 102 (37.8) 41 (15.2) 9 (3.3) |

0.077 |

| Characteristics |

All (N = 424) |

Atherectomy (n = 90) |

PTA± Stenting (n = 334) |

P value |

| Ankle-brachial index Pre-procedure Post-procedure P value |

0.41 ± 0.29 0.90 ± 0.24 < 0.001 |

0.47 ± 0.26 0.94 ± 0.24 < 0.001 |

0.36 ± 0.31 0.91 ± 0.24 < 0.001 |

0.003 0.340 |

| Walking Impairment Questionnaire score Pre-procedure Post-procedure P value |

51.9 ± 25.0 86.3 ± 16.4 < 0.001 |

52.3 ± 22.4 87.5 ± 12.9 < 0.001 |

46.1 ± 25.8 85.8 ± 17.8 < 0.001 |

0.106 0.523 |

| Amputation rate | 29 (6.8) | 11 (12.2) | 18 (5.4) | 0.032 |

| Mortality rate | 12 (2.8) | 2 (2.2) | 10 (3.0) | 0.695 |

| Cause of death | 3 Myocardial infarction 2 Pneumonia 1 ARDS 1 Cancer progression 1 COVID 1 Hydropneumothorax 1 Ischemic colitis 1 Sepsis 1 Subdural hemorrhage |

1 COVID 1 Pneumonia |

3 Myocardial infarction 1 ARDS 1 Cancer progression 1 Hydropneumothorax 1 Ischemic colitis 1 Pneumonia 1 Sepsis 1 Subdural hemorrhage |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).