Nanotechnology, the manipulation and utilization of materials at the nanometre scale, has emerged as a revolutionary field with vast applications across various scientific domains [

1]. In recent years, its integration into the study of fungi has opened new avenues for enhancing fungal activity, leading to significant advancements in agriculture, medicine, and environmental sustainability [

2]. Fungi play critical roles in ecosystems, including nutrient cycling, plant growth promotion, and bioremediation [

3]. However, harnessing their full potential has often been limited by challenges such as suboptimal growth conditions, pathogen resistance, and inefficient delivery systems for fungal inoculants [

4]. Nanotechnology offers innovative solutions to these challenges by providing tools and materials that can interact with fungi at the molecular level [

5]. One of the key applications of nanotechnology in mycology is the development of nanoparticle-based delivery systems [

6]. These systems can encapsulate and protect fungal spores or mycelium, ensuring their stability and enhancing their efficacy in various environments [

7]. For instance, nanoparticles can facilitate the controlled release of fungi in agricultural settings, promoting plant health and increasing crop yields through improved nutrient uptake and disease resistance [

8]. Moreover, nanomaterials can be engineered to enhance the enzymatic activity of fungi, thereby improving their ability to degrade pollutants and organic matter [

9]. This has profound implications for bioremediation efforts, where fungi are utilized to break down hazardous substances in contaminated soils and water bodies [

10]. The increased efficiency and specificity of fungal enzymes, achieved through nanotechnology, can significantly accelerate the detoxification process [

11]. In medicine, nanotechnology has the potential to transform fungal-based therapies [

12]. Fungal metabolites, such as antibiotics and anticancer agents, can be delivered more effectively using nanocarriers, leading to enhanced therapeutic outcomes [

13]. Additionally, nanomaterials can be used to develop antifungal coatings and materials, reducing the risk of infections and improving hygiene in medical settings [

14]. Despite these promising developments, the application of nanotechnology in enhancing fungal activity is still in its nascent stages [

15]. Further research is needed to understand the interactions between nanomaterials and fungal cells, optimize delivery systems, and assess the environmental and health impacts of nanotechnology [

16].

Despite the promising potential of fungi in various applications such as agriculture, bioremediation, and medicine, their full utilization is hindered by several challenges [

17]. These include suboptimal growth conditions, limited pathogen resistance, and inefficient delivery mechanisms for fungal inoculants [

18]. Traditional methods of enhancing fungal activity often fall short due to their inability to precisely control and optimize the conditions necessary for maximum fungal efficacy [

19]. Additionally, the stability and bioavailability of fungal spores or metabolites in different environments pose significant challenges [

20]. Nanotechnology, with its capacity to manipulate materials at the nanoscale, offers innovative solutions to these problems [

21]. However, the interactions between nanomaterials and fungal cells remain poorly understood, and the environmental and health impacts of these nanotechnological interventions are not fully elucidated [

22]. Addressing these challenges is critical for realizing the full potential of fungi in contributing to sustainable agricultural practices, effective bioremediation strategies, and advanced medical treatments [

23].

One promising method to overcome the limitations of traditional fungal enhancement techniques is the use of vaterite carriers [

24]. Vaterite, a polymorph of calcium carbonate, is an innovative nanomaterial known for its biocompatibility, high surface area, and ease of functionalization [

25]. These properties make vaterite an ideal carrier for delivering fungal spores and metabolites, thereby enhancing antifungal activity [

26]. When utilized as a carrier, vaterite nanoparticles can encapsulate and protect fungal bioactive compounds, improving their stability and prolonging their release in targeted environments [

27]. This controlled release mechanism ensures that the fungi remain active for extended periods, thereby increasing their efficacy against pathogens [

28]. Additionally, the porous structure of vaterite allows for the incorporation of multiple antifungal agents, potentially enhancing the synergistic effects and overall antifungal potency [

29]. By optimizing the delivery and activity of fungi, vaterite carriers offer a novel solution to the challenges faced in leveraging fungal applications for agricultural, environmental, and medical purposes, paving the way for more effective and sustainable antifungal strategies [

30].

The primary objective of this study is to enhance the antifungal effects of sertaconazole nitrate by employing vaterite carriers for topical drug delivery. Specifically, the research aims to formulate and evaluate a hydrogel incorporating these vaterite carriers, thereby improving the stability, controlled release, and efficacy of sertaconazole nitrate against fungal infections. The hypothesis is that the incorporation of sertaconazole nitrate into vaterite carriers within a hydrogel formulation will significantly enhance its antifungal activity compared to traditional topical formulations. It is anticipated that vaterite carriers will provide a sustained and controlled release of sertaconazole nitrate, improving its bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy against fungal pathogens. Additionally, the hydrogel matrix is expected to facilitate better skin penetration and prolonged retention of the drug at the site of infection, resulting in improved antifungal outcomes and patient compliance.

Materials and methods

Materials

The synthesis of Sertaconazole nitrate-fabricated calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) nanoparticles involves a series of carefully selected materials. Calcium chloride, sourced from Merck, serves as the cross-linking agent, while sodium carbonate from Universal Starch Chem Allied Ltd is used as an emulsifier agent. Oleic acid, obtained from Sisco Research, functions as the oil phase, and Tween-80, also from Sisco Research, acts as an additional emulsifier. The active pharmaceutical ingredient, Sertaconazole nitrate, is provided by Areete Life Sciences (AR Grade) and is the primary antifungal drug incorporated into the nanoparticles. For the formulation of the Sertaconazole nitrate-CaCO₃ antifungal nano-hydrogel, several materials are utilized. Carbopol 940 from Sisco Research serves as the gelling agent, while the synthesized Sertaconazole nitrate-CaCO₃ nanoparticles facilitate nano drug delivery. Propylene glycol, acquired from Merck, acts as the vehicle, and methyl paraben 0.5% from Merck functions as a preservative. Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), also from Merck, is used as a thickening agent, and distilled water from Merck is employed as the primary solvent. Lastly, triethanolamine from Sisco Research Laboratories (SRL) is included as a pH adjuster to ensure the optimal formulation of the hydrogel.

Characterization techniques play a crucial role in assessing the properties and efficacy of pharmaceutical formulations [

31]. UV-Vis spectroscopy provides valuable insights into the absorbance spectra of nanoparticles and drug carriers, aiding in the quantification of drug loading and carrier stability [

32]. FTIR spectroscopy elucidates molecular interactions between Sertaconazole Nitrate and vaterite nanoparticles, confirming chemical compatibility and structural integrity [

33]. SEM imaging techniques offer high-resolution visualization, revealing the morphology and size distribution of the vaterite nanoparticles, crucial for assessing their suitability as drug carriers [

34]. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) determines the hydrodynamic size distribution of nanoparticles in solution, ensuring uniformity and stability [

35]. Zeta potential measurements quantify the surface charge of nanoparticles, influencing their colloidal stability and interaction with fungal cell membranes, thus enhancing the antifungal efficacy of Sertaconazole Nitrate encapsulated within vaterite nanoparticles [

36]. These characterization techniques collectively optimize the formulation of Sertaconazole Nitrate-loaded vaterite nanoparticles, potentially enhancing their antifungal potency and therapeutic efficacy.

Evaluation of fungal activity for SN mediated vaterite carrier nanoparticles

In silico screening of Sertaconazole nitrate against fungal biofilms

Selection of Receptor and Ligand

For the selection of protein and ligand, the ligand chosen was Sertaconazole Nitrate, a widely studied antifungal agent used against Candida albicans. The protein target associated with this interaction is represented by the crystal structure of the N240A mutant of Candida albicans Mep2 (PDB ID: 6EJ6). This protein, a high-affinity ammonium permease, plays a significant role in nutrient acquisition and morphological transitions of Candida albicans, particularly under nitrogen-limiting conditions. The high-resolution structure, refined at 1.65 Å, provides detailed atomic insights essential for studying ligand binding and interaction affinities. By examining this mutant protein-ligand interaction, potential mechanisms and binding efficiencies of Sertaconazole Nitrate against Candida albicans Mep2 can be elucidated, potentially guiding new antifungal therapeutic strategies.

The molecular docking study using PyRx and Biovia Discovery Studio 2024 follows a systematic approach to assess the binding interactions of Sertaconazole Nitrate with the Candida albicans Mep2 protein mutant (PDB ID: 6EJ6) [

37]. Initially, protein and ligand preparation is carried out by importing the protein structure and removing extraneous molecules, while the ligand is converted to a compatible format (PDBQT) and minimized for stability using OpenBabel in PyRx. The receptor's binding site is targeted by defining a grid box around the active site, set to ensure adequate coverage. AutoDock Vina in PyRx is then used for the docking simulation, generating various poses and binding affinities (kcal/mol) for analysis. The top-ranked docked complex is subsequently imported into Biovia Discovery Studio 2024 to visualize detailed interactions between the ligand and protein residues. Key interaction types, such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and pi-pi stacking, are identified through the "2D Interaction" and "Ligand Interactions" tools, highlighting residues within 4 Å of the ligand. Binding site analysis and conformational assessments provide further insights into the stability and efficacy of the binding, and key interactions are visualized for documentation. This methodology offers a thorough evaluation of the ligand’s potential therapeutic efficacy by predicting and validating its binding orientation and affinity, essential for guiding antifungal therapy design.

The well diffusion method was used to assess SN-CaCO3 antifungal efficacy against infections in the skin [

38]. By brushing the surface of the agar with a sterile swab to inoculate nutritional agar plates with a sufficient amount of the test microorganism, an unaltered microbial lawn was produced [

39]. Using an industrial well puncher or a clean cork borer, drilling was made on the agar. Various SN-CaCO3 concentrations (20 µL) were introduced into the holes on multiple plates. The positive control consisted of wells holding an antifungal agent that was well-known (fluconazole). Following that, the plates underwent incubation for 18 to 24 hours at the microorganism's ideal temperature (25°C for fungus). The antifungal activity of SN-CaCO3 was evaluated by looking at the plates shortly after incubation and measuring the diameter of the visible inhibition zone surrounding each well in millimetres with a calibrated ruler [

40].

Applying a round bottom 96-well microtiter plate in sterile conditions, the ability of synthesized SN-CaCO3 NPs to inhibit bacterial biofilm formation was examined, following a slightly modified protocol previously reported. The microtiter plate evaluation, commonly referred to as the 96-well plate assay, is a technique for studying bacterial adherence to an abiotic surface in biofilm formation research. In 96-well microtiter plates with a vinyl "U" bottom type, bacteria are cultured. After incubation, planktonic bacteria are removed by rinsing, and the adhering bacteria (biofilms) that remain are coloured with crystal violet dye to make them visible [

41]. The dyed biofilms dissolve and placed to a 96-well optically transparent flat-bottom plate for spectrophotometric measurements if quantify is necessary [

42]. At 620 nm, absorbance was measured to quantify biofilm development [

43].

A231 cell cultures for skin cancer were obtained from the National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS) located in the Indian state of Maharashtra. The skin cancer cells were cultured using Eagles Minimum Essential Medium, which contains 10% fetal bovine serum. The atmosphere was kept at 95% and carbon dioxide at 5% moisture content, respectively, while the living cancer cells was kept at 100% relative humidity. The cancer cell's temperature was kept constant at 37 ◦C. Twice a week, maintain cells were changed on, and the culture medium replaced twice a week [

44].

Using trypsin-ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA), monolayer cells were separated into suspensions of individual cells. The mixtures were diluted using 5% FBS medium to achieve a cell density of 1 × 10

5 cells/mL [

45]. The viable cells were then counted using a hemacytometer. After seeding the cell solution (100 mL) onto 96-well plates with 10,000 cells per well, the plates were incubated at 100% relative humidity for a while. After that, the dishes were maintained at 5% and 95% carbon dioxide and oxygen, respectively. For better cell adherence, the incubator temperature was 37◦C. The test samples are exposed to progressive cell dosages after a day. After dissolving them in a basic dimethyl sulfoxide, the sample solution is diluted in a serum-free medium to double the required final highest assessment concentrations. Four serial dilutions were used to generate five sample concentrations. The desired final sample quantities can be attained by filling the wells with 100 mL of the medium and 100 mL of the sample dilutions in aliquots. Following sample addition, the culture dishes were incubated for a further two days at 37◦C, 100% relative humidity, 5% CO

2, and 95% air. As reported by [

46,

47], the control medium consisted of three duplicates of each concentration.

This MTT examination was performed using 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl] 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, a yellow-colored, water-soluble tetrazolium salt. The enzyme succinate-dehydrogenase in live cells breaks down the tetrazolium chain in MTT, transforming it into an insoluble violet formazan. The number of viable cells and the amount of formazan produced are negatively correlated. After two days, each well received 15 mL of MTT (5 mg/mL) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution. The wells were then properly mixed and kept at 37 °C for 4 hours [

48]. The formazan crystals are dissolved using 100 mL of DMSO after the MTT medium has been removed. The amount of absorption at 570 nm was measured with a microplate reader. The following formula was used to determine the viability percentage:

To formulate a Sertaconazole-mediated calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) nanoparticle hydrogel, a systematic process and precise ingredient selection are essential for stability, effective delivery, and controlled release. The formulation begins by preparing a hydrogel base using Carbopol 940 (0.5-1% w/v) as the gelling agent, which is dispersed in distilled water (up to 90% of the total volume) under continuous stirring. After allowing 1-2 hours for full hydration, glycerin (2-5% w/v) is added to enhance moisture retention and improve the gel’s non-drying properties on the skin. In a separate beaker, the pre-synthesized Sertaconazole-mediated CaCO₃ nanoparticles are dispersed in ethanol (5-10% w/v) and sonicated for 10-15 minutes to ensure even distribution and prevent nanoparticle aggregation. This suspension is then gradually introduced to the gel base with continuous stirring, allowing the nanoparticles to integrate uniformly without settling. To complete gel formation, triethanolamine (TEA) is added dropwise, adjusting the pH to a skin-compatible range of 5.5 to 7, while also promoting Carbopol’s thickening action. The final gel is gently homogenized to achieve a smooth consistency and then transferred into airtight containers for storage. This carefully formulated hydrogel ensures stable dispersion and controlled release of Sertaconazole, enhancing its antifungal efficacy and making it suitable for sustained topical application.

Visually inspect the hydrogel for uniformity, colour, transparency, and any signs of phase separation or particulate matter. The texture should be smooth, with no grainy or uneven aspects, indicating consistent distribution of the nanoparticles [

49].

Measure the pH of the hydrogel using a calibrated pH meter. Skin-friendly hydrogels should ideally fall within the pH range of 5.5 to 7. Adjustments may be needed if the pH deviates, as it impacts both stability and skin compatibility [

50].

Use a viscometer or rheometer to assess the hydrogel’s viscosity and flow behavior. Consistency in viscosity across batches indicates stability, while non-Newtonian flow properties (e.g., pseudoplasticity) are desirable for ease of application and retention on skin [

51].

Spreadability is assessed by measuring the extent to which the hydrogel spreads on the skin or a surface, which is crucial for ensuring even coverage over the application area. Typically, a small amount of hydrogel is placed between two glass slides, and a specific weight is applied on top. The spread diameter is measured after a set time, with higher values indicating better spreadability. This parameter is essential for user comfort and therapeutic efficiency, as it ensures that the drug is evenly distributed [

52].

On the other hand, tests the hydrogel’s ability to be easily removed from the skin with water. A sample of the hydrogel is applied to the skin or another surface and then rinsed with water under gentle rubbing. The ease with which it washes off without leaving residue is an important aspect of user experience, particularly for topical applications. A washable hydrogel is preferred as it enhances patient compliance by allowing for easy removal after the treatment duration [

53].

To evaluate the permeation profile of Sertaconazole-mediated CaCO₃ nanoparticle hydrogel, a Franz diffusion cell assay was conducted over a 1-hour period with sample collection every 10 minutes [

54]. The assay setup involved placing a synthetic membrane (hydrated cellulose acetate) over the receptor compartment of the Franz cell, which was pre-filled with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C to simulate physiological conditions. An appropriate amount of the hydrogel was applied to the donor compartment above the membrane, and the system was sealed to prevent evaporation. The receptor medium was continuously stirred with a magnetic stirrer to maintain uniform drug distribution. Samples of 0.5 mL were withdrawn from the receptor compartment every 10 minutes, with the withdrawn volume replaced immediately with fresh, pre-warmed PBS to ensure consistent sink conditions. These samples were then analysed via UV-Vis spectrophotometry to quantify the amount of Sertaconazole that permeated through the membrane at each time interval. This time-dependent data allowed for the construction of a cumulative permeation profile, providing insight into the rate and extent of drug release from the hydrogel within the first hour, essential for assessing the formulation's effectiveness in topical delivery.

Results and discussion

UV analysis

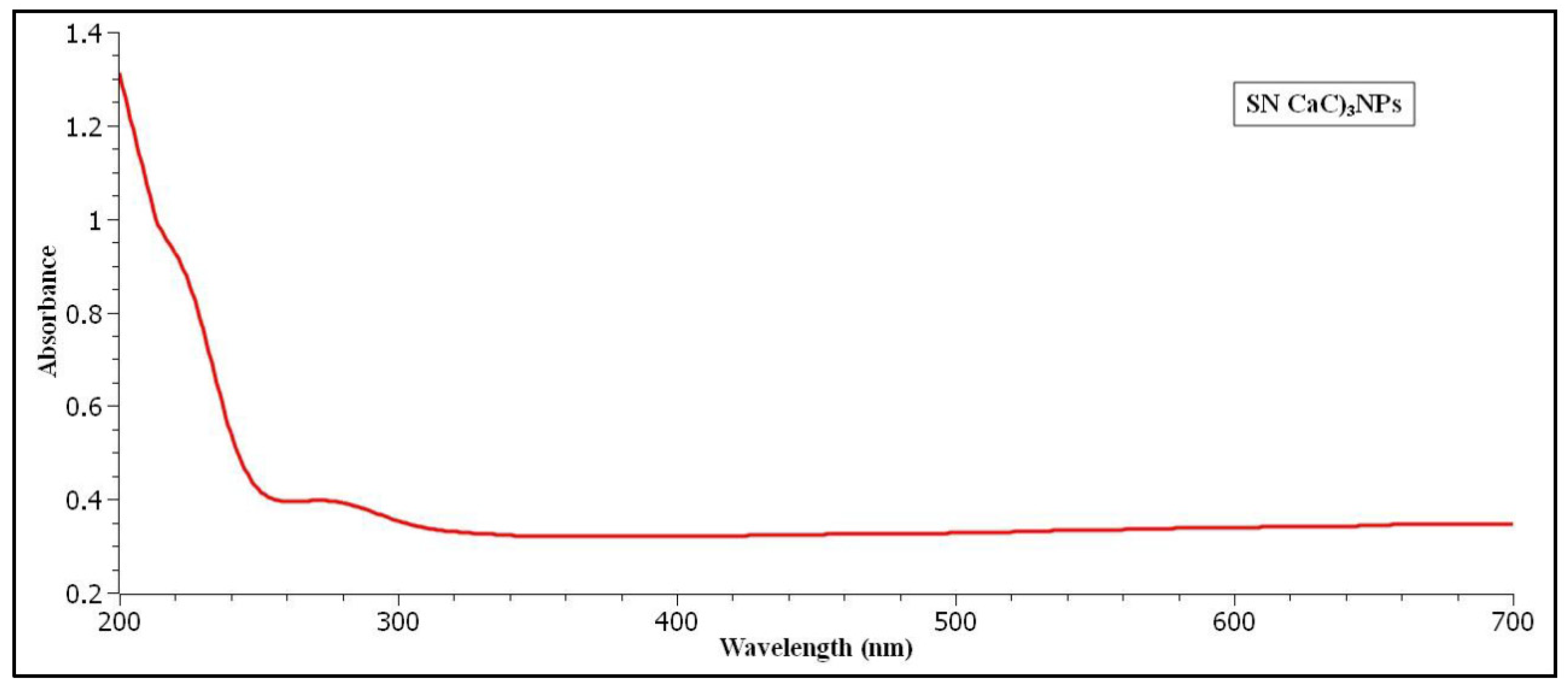

The UV Visible spectroscopy is evaluated for Sertaconazole nitrate fabricated CaCO3 Vaterite carrier nanoparticles. According to UV analysis calibrated in the range 200 nm to 700 nm. The pure ethanol is taken as base correction line. The colour of our nanoparticles is milky white which confirms synthesis of vaterite carrier nanoparticles. As a result, the UV peaks at 275 nm absorbance exhibits visible spectrum. The UV analysis graphical image is described in figure (

Figure 1).

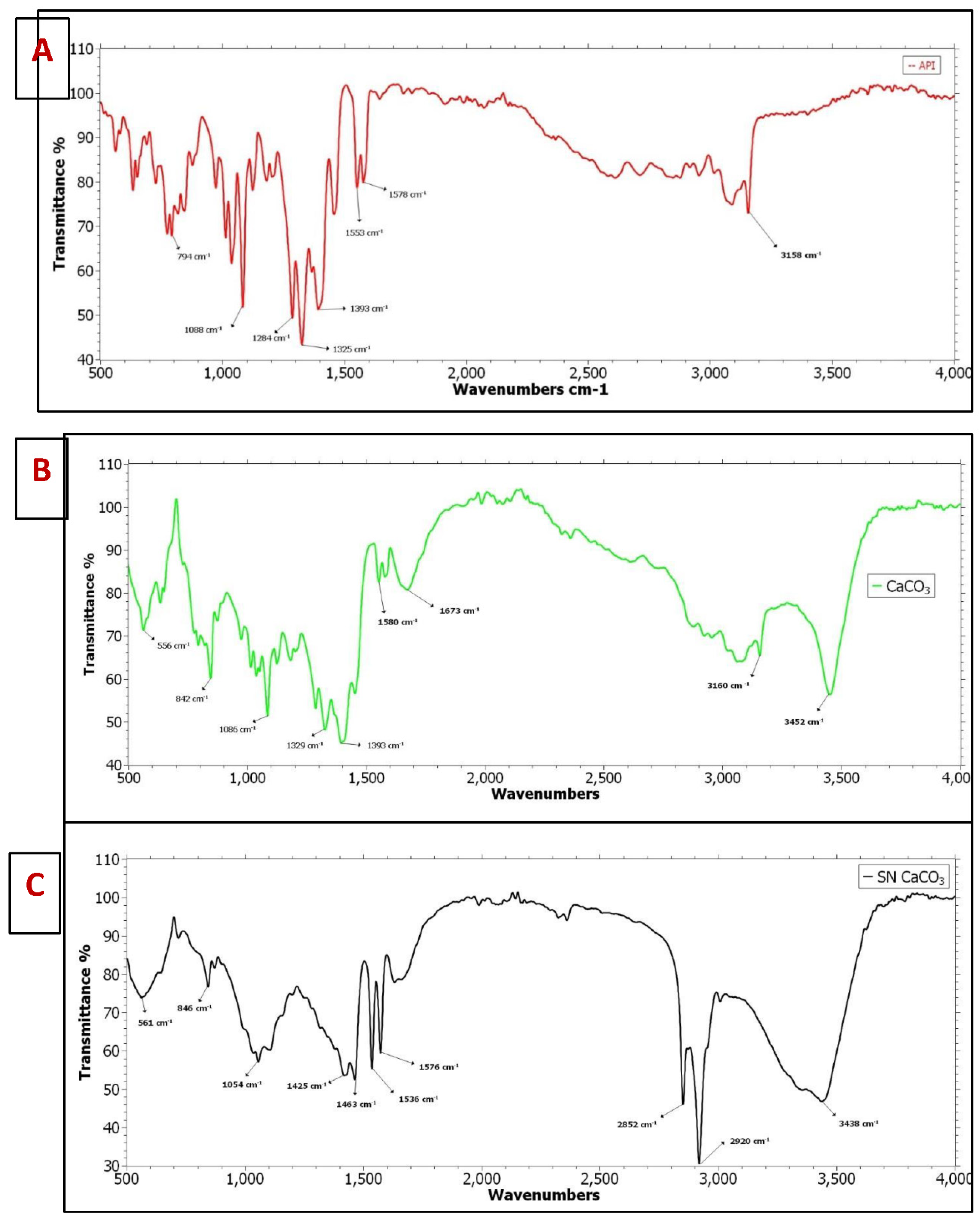

The FTIR analysis is predicted for 3 different samples which include Pure API (A), CaCO3 vaterite carrier (B) and Sertaconazole nitrate mediated CaCO3 nanoparticles (C). The combined FTIR graph is plotted by using Origin Pro 2023 software which is shown in figure (

Figure 2a). For the pure drug API Sertaconazole nitrate shows major 5 peaks in fingerprint regions which include 1325 cm-1 exhibits strong C-F stretching having fluoro-compound functional group. Then 1284 cm-1 shows strong C-N stretching having aromatic amine functional group likewise 1088 cm-1 shows strong C-O stretching expresses secondary alcohol. Furthermore, 1393 cm-1 exhibits strong S=O stretching having sulfate functionality. Also, 794 cm-1 shows strong C-H bending expresses 1,4 disubstituted functional group. Furthermore, In double bond region shows major couple of peaks having ranging 1553 cm-1 which shows strong N-O stretching nitro compounds and then 1578 cm-1 exhibits C=C stretching medium peak having cyclic alkene functionality. There is no major peak visible in triple bond region. In single bond region shows only one broad and stronger peak which exhibits O-H stretching carboxylic acid functional group. Similarly, CaCO3 vaterite carrier (B) was characterized by FTIR is shown in figure (

Figure 2b), in fingerprint regions 5 major peaks are identified among that 1393 cm-1 S=O stretching exhibits strong sulfate groups. Then 1329 cm-1 shows strong C-N stretching aromatic amine. Then 1086 cm-1 strong C-F stretching having fluoro compound functional group. Also 842 cm-1 C-Cl stretching strong peak expresses halo compounds. Likewise, 556 cm-1 having strong C-I stretching halo compound functional group. In double bond regions 1673 cm-1 exhibits strong C=O stretching primary amide functional group. Then 1580 cm-1 shows medium peak having N-H bending amine functional group. In triple bond region there is no major visible peak in this analysis. Additionally, In single bond region having 2 peaks which include 3160 cm-1 strong O-H stretching carboxylic acid functional group and 3452 cm-1 exhibit strong O-H stretching alcohol functional group. Finally, Sertaconazole Nitrate mediated CaCO3 nanoparticles is analysed in FTIR is described in figure (

Figure 2c), In fingerprint region shows 5 major peaks which includes 1463 cm-1 having medium peak exhibits C-H stretching alkane functional group, the peak 1425 cm-1 exhibits medium O-H bending carboxylic acid functional group, the peak 1054 cm-1 strong C-O stretching primary alcohol functionality. Then the peak 846 cm-1 strong C-Cl stretching shows halo compounds and peak 561 cm-1 shows strong C-I stretching exhibits halo compounds functional group. Furthermore, in double bond region 1535 cm-1 strong peak shows N-O stretching nitro compounds and 1576 cm-1 shows medium C=C stretching cyclic alkene functional groups. Then, in like A and B sample, for this sample C also having no visible peaks in triple bond regions. Finally in single bond region, the three major peak 2852 cm-1, 2920 cm-1, and 3438 cm-1 exhibits strong O-H stretching alcohol functional group. According to Deng et al., [

55] investigation 5-Fluorouracil coated CaCO3 NPs exhibits remarkable functional group. Similarly,

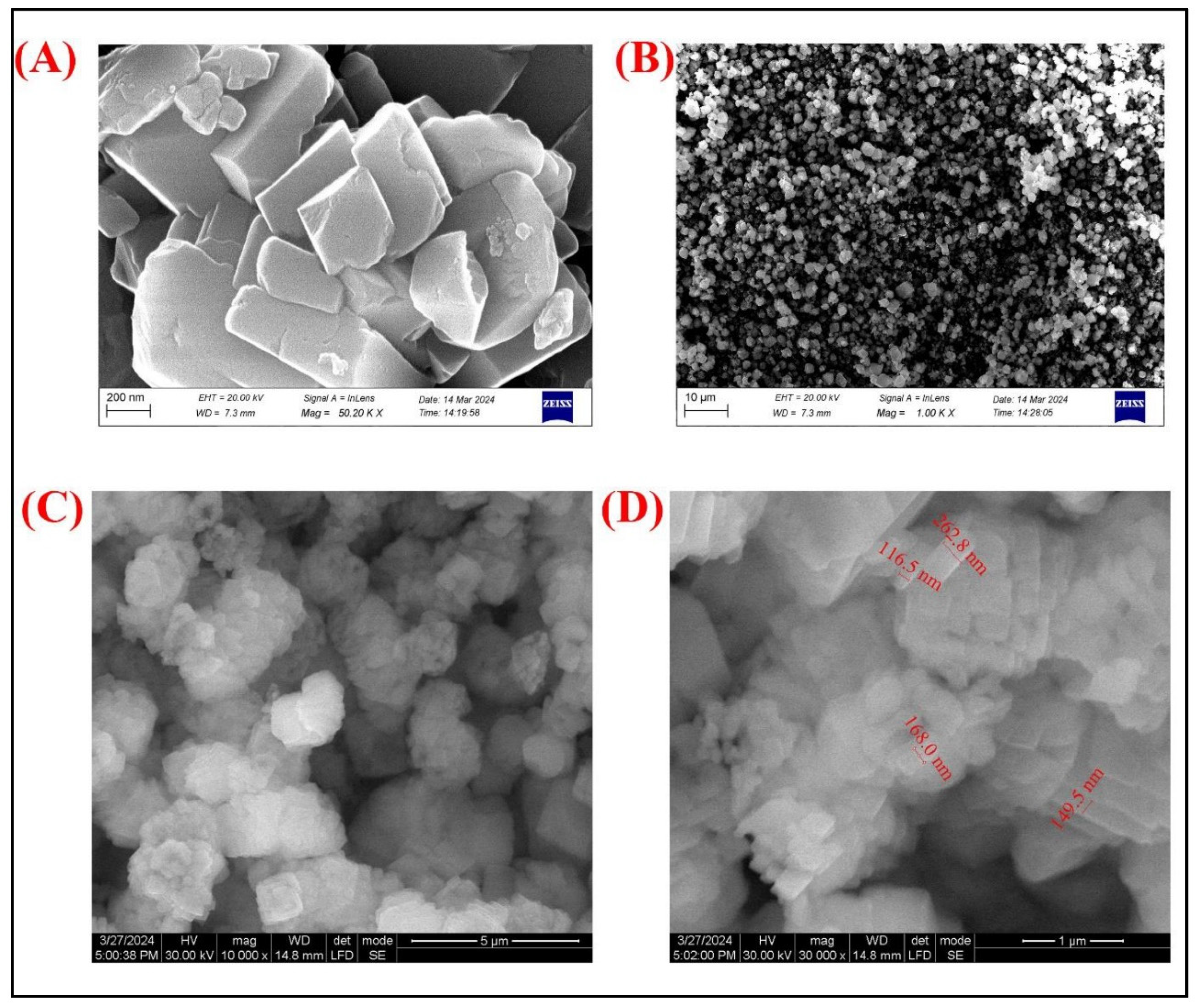

The SEM images (

Figure 3A and B) provide detailed morphological insights into the Sertaconazole-mediated CaCO₃ nanoparticles. Image (

Figure 3A), captured at a magnification of 50.20 KX, reveals a well-defined crystalline structure, with particles displaying angular, plate-like shapes indicative of CaCO₃ crystals. The surface of these particles appears smooth with slight irregularities, potentially due to the coating or embedding of Sertaconazole molecules. In Image (

Figure 3B), taken at a lower magnification of 10.0 KX, a more extensive distribution of particles is visible, showing homogeneity in particle formation with uniform dispersion. This suggests that the synthesis process yielded a consistent structure across a larger sample area, contributing to uniformity in particle morphology, which is advantageous for potential biomedical applications where size and shape uniformity are critical for drug delivery efficiency. According to Deng et al., [

55] investigation SEM shows uniform particle aggregation for CaCO3 NPs.

The TEM images (

Figure 3C and D) further elucidate the structural characteristics and size distribution of the Sertaconazole-mediated CaCO₃ nanoparticles. In Image (

Figure 3C), taken at 10,000x magnification, the particles appear as aggregates of nearly spherical, nanometer-sized particles, indicative of successful nanoparticle formation. The high magnification image (

Figure 3D) provides precise measurements of particle sizes, showing a range from approximately 149.5 nm to 262.8 nm. This size distribution confirms the nanometric scale of the particles, which is desirable for enhanced permeability and retention in therapeutic applications. The consistency in particle size seen in TEM complements the uniform morphology observed in SEM, indicating a stable formulation process. Overall, these TEM images validate the nanoscale synthesis and suitability of Sertaconazole-mediated CaCO₃ nanoparticles for controlled drug delivery systems.

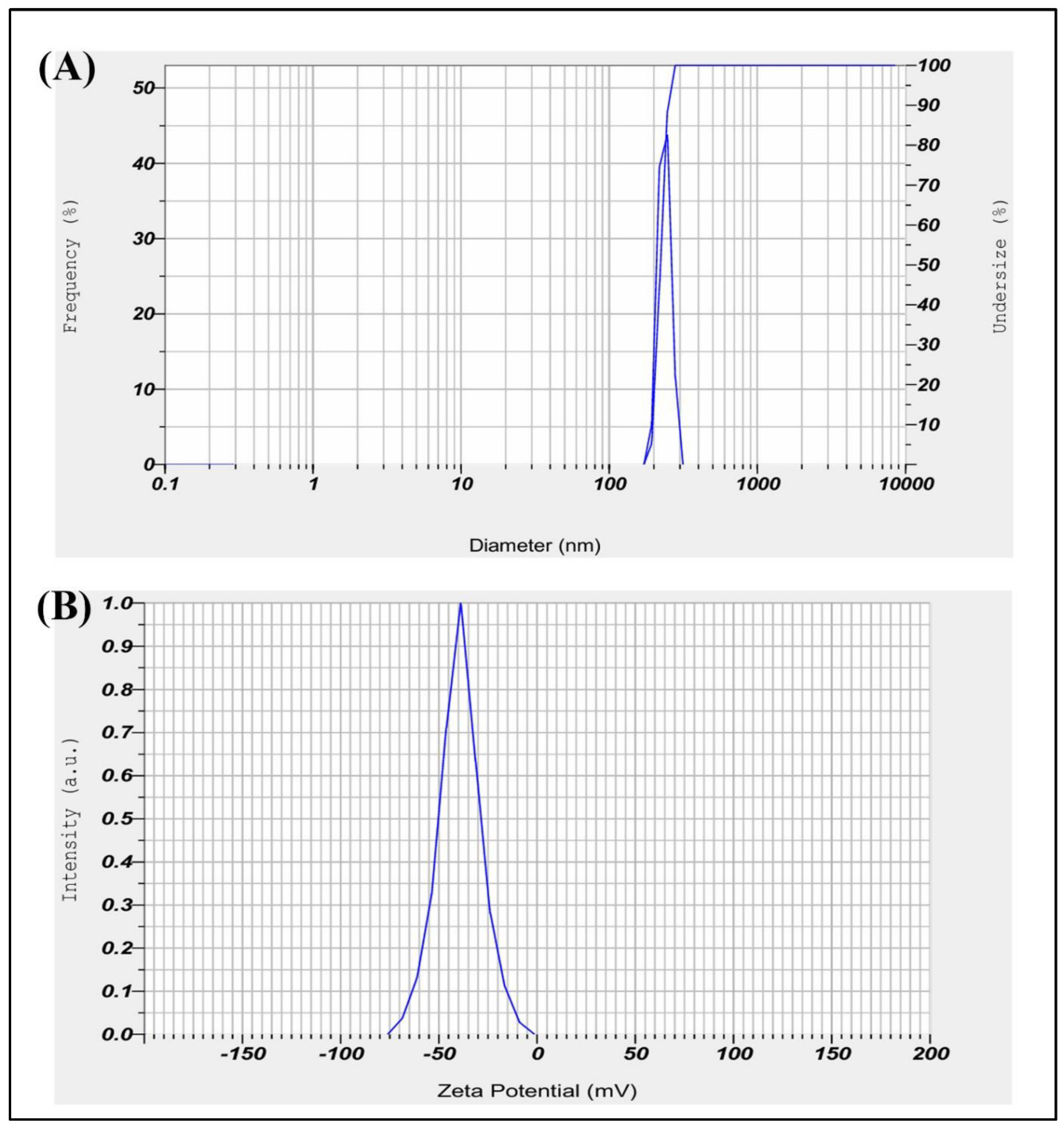

The dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis of Sertaconazole-mediated CaCO₃ nanoparticles yielded a primary particle size distribution with a mean diameter of 222.7 nm and a standard deviation of 20.6 nm (

Figure 4a). The monodisperse nature of the particle distribution is indicated by a single peak with a mode value of 223.4 nm, demonstrating consistency in particle size, which is beneficial for uniform drug delivery. However, the Z-average diameter was recorded as 4224.2 nm, suggesting the presence of larger agglomerates or aggregates in the suspension. The polydispersity index (PI) of 2.654 also indicates some degree of polydispersity, which may result from particle aggregation. This variation between the mean particle size and Z-average suggests that although the nanoparticles themselves are of desirable size for biomedical applications, optimization of the suspension or dispersion protocol may be necessary to minimize aggregation for consistent therapeutic performance. According to Deng et al., [

55] investigation DLS shows 827 nm for CaCO3 NPs.

The Zeta Potential measurement for Sertaconazole-mediated SN-CaCO₃ nanoparticles yielded a mean Zeta Potential of -39.4 mV, with an electrophoretic mobility mean of -0.000304 cm²/Vs (

Figure 4d). The sample temperature was 24.9°C, and the dispersion medium viscosity was 0.897 mPa·s. The measurement was conducted with an electrode voltage of 3.4 V, and the conductivity was recorded at 0.101 mS/cm. A Zeta Potential of -39.4 mV indicates that the nanoparticles possess a strong negative surface charge. This high negative potential suggests good stability of the nanoparticles in suspension, as the repulsive forces between particles reduce aggregation. For SN-CaCO₃ nanoparticles mediated by Sertaconazole, this stability is beneficial, potentially enhancing the particles bioavailability and effectiveness for drug delivery applications.

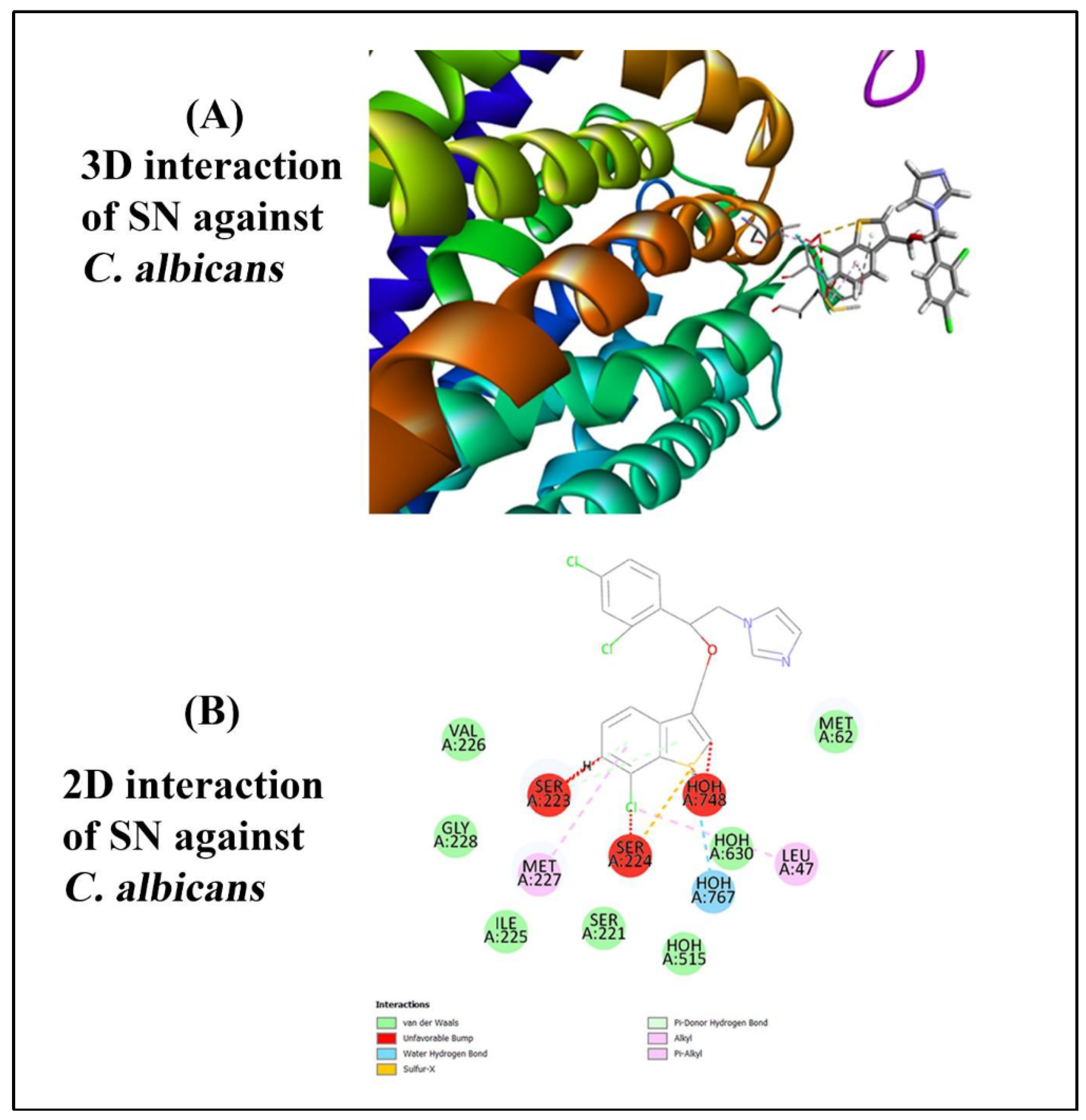

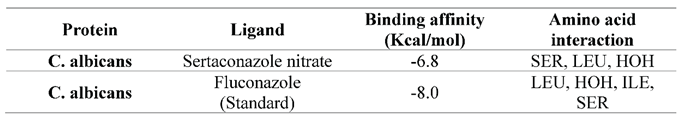

The molecular docking simulations were performed using PyRx software to predict the binding affinity and binding modes of the selected ligands to the target protein. The results of the docking simulations revealed significant differences in the binding affinities and binding poses among the ligands. Among the ligands tested, Sertaconazole nitrate ligand exhibited the predicted binding affinity, with a docking score of -6.8 kcal/mol. The docking pose of Sertaconazole nitrate within the binding site showed several key interactions, including hydrogen bonding with residues A767. These interactions are consistent with the known binding mode of Ligand based on experimental data, validating the accuracy of the docking predictions. In contrast, Fluconazole (control) displayed a lower binding affinity compared to Ligand A, with a docking score of -8.0 kcal/mol. The docking pose of Ligand showed more hydrogen bonding interactions and a less favourable binding orientation within the binding site. However, analysis of the binding mode revealed the presence of key hydrophobic contacts with residues Val103 and Trp105, contributing to the overall stability of the ligand-protein complex. Finally, the 2D interaction and 3D interaction is shown in figure (

Figure 5 A & B) as well as binding affinity of ligand against receptor is discussed in table (

Table 1)

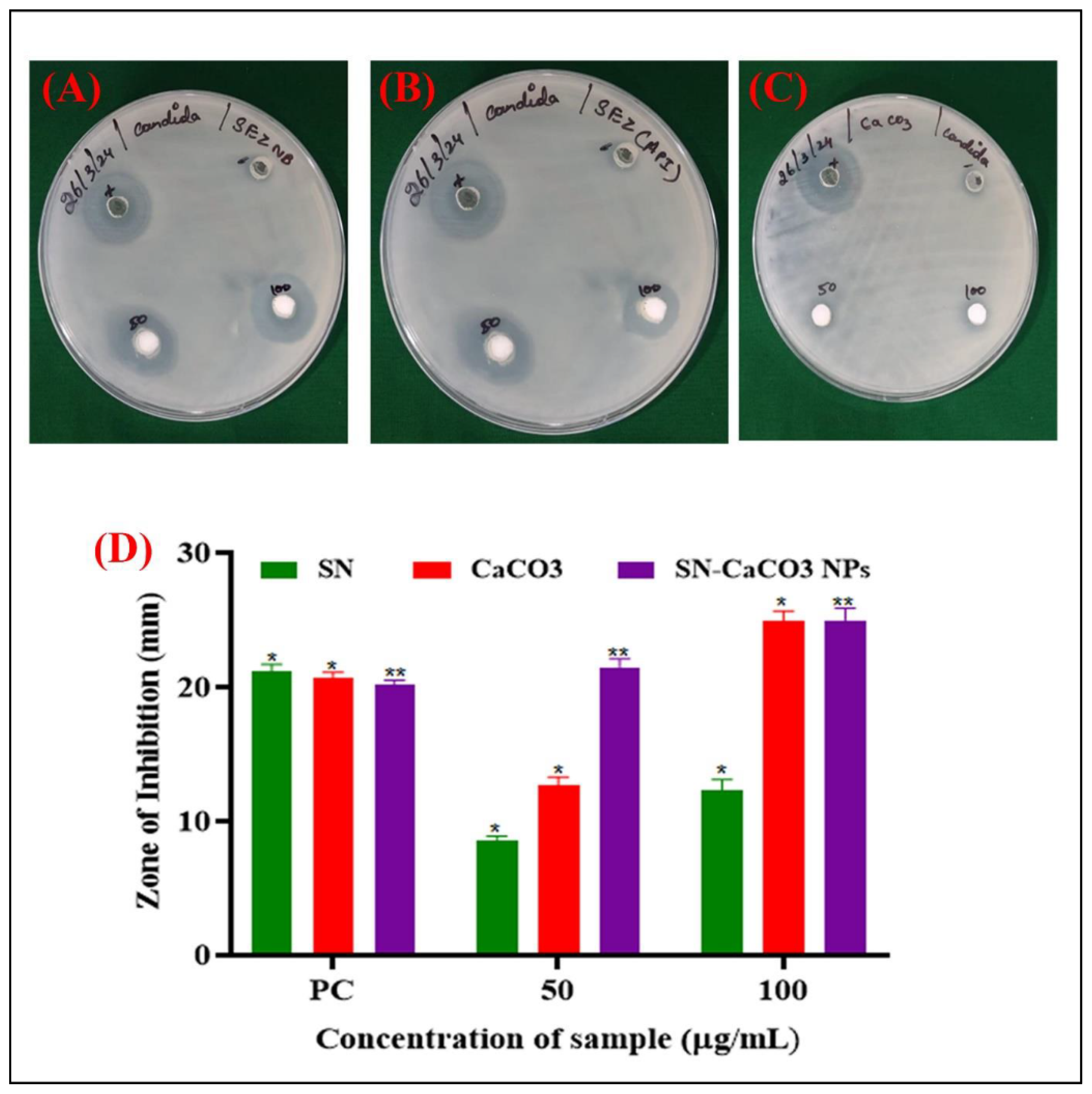

The well diffusion method results for Sertaconazole nitrate (SN), calcium carbonate (CaCO₃), and Sertaconazole nitrate-loaded CaCO₃ nanoparticles (SN-CaCO₃ NPs) at various concentrations (50 and 100 µg/ml) reveal notable differences in antimicrobial effectiveness (

Figure 6). The diameter of inhibition zones (in mm) is recorded for each formulation, providing insight into their ability to inhibit microbial growth. For the positive control (PC), the inhibition zones were consistent, showing values of 21.2 mm, 20.7 mm, and 20.2 mm for SN, CaCO₃, and SN-CaCO₃ NPs, respectively. This indicates that all formulations have antimicrobial activity that is comparable to the standard, with SN-CaCO₃ NPs performing similarly to SN and CaCO₃ alone. At a 50 µg/ml concentration, SN exhibited an inhibition zone of 8.6 mm, while CaCO₃ showed a slightly higher activity with a 12.7 mm zone. Interestingly, SN-CaCO₃ NPs demonstrated a significantly larger inhibition zone of 21.5 mm, indicating an enhanced antimicrobial effect when SN is loaded onto CaCO₃ nanoparticles. This enhancement may be due to improved stability, bioavailability, and targeted release provided by the nanoparticle structure, which likely increases the effectiveness of SN in reaching and inhibiting microbial cells.

At 100 µg/ml, the trend continues with SN and CaCO₃ alone showing inhibition zones of 12.3 mm and 24.9 mm, respectively, whereas SN-CaCO₃ NPs had the highest inhibition zone of 25 mm. This suggests that at higher concentrations, the combination of SN with CaCO₃ nanoparticles provides maximum antimicrobial efficacy, potentially due to the synergistic effect of the nanoparticle carrier enhancing drug delivery and retention at the target site.

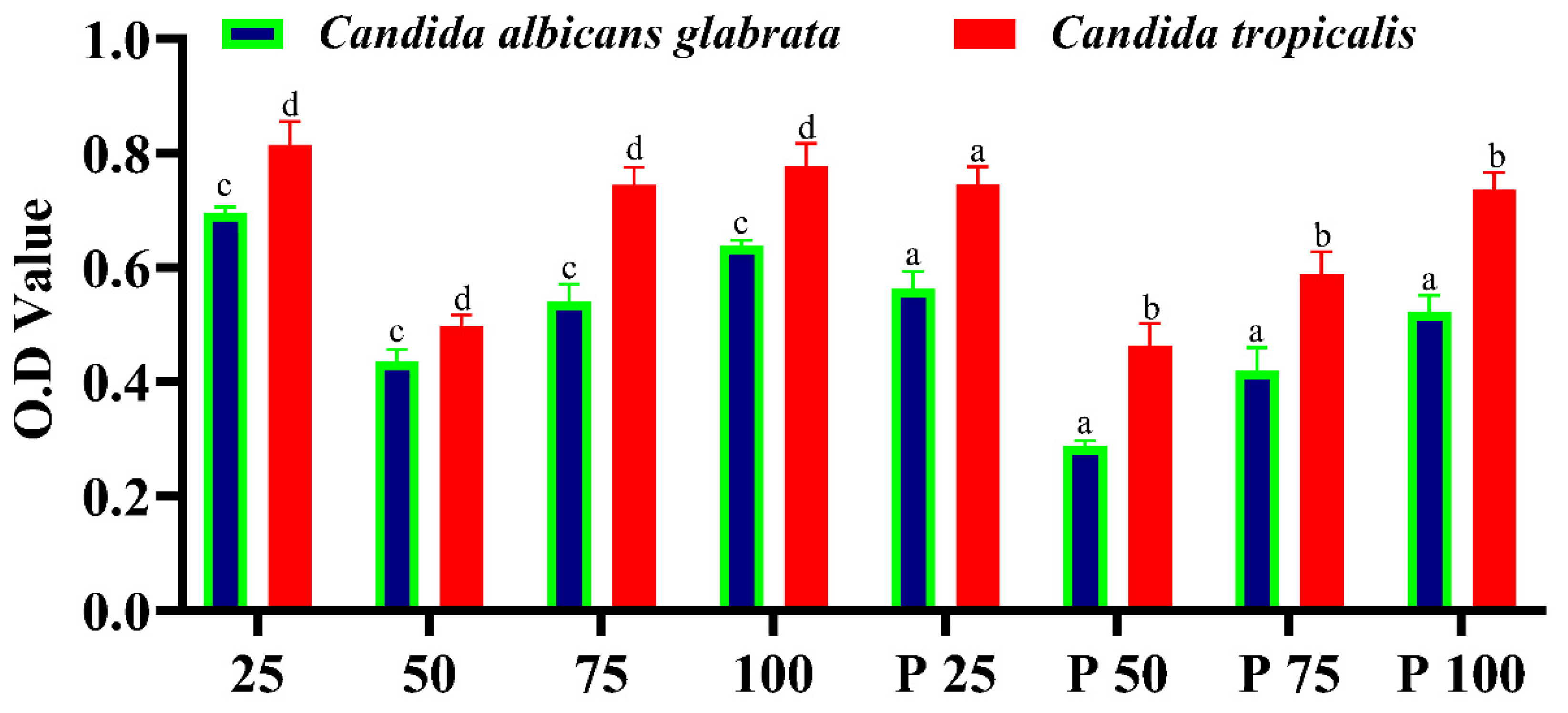

The biofilm microtiter assay results highlight the potential of Sertaconazole-mediated SN-CaCO₃ nanoparticles (NPs) as biofilm inhibitors. Across different concentrations, these nanoparticles demonstrate a capability to inhibit biofilm formation, although their effectiveness varies. At lower concentrations (25 and 50 µg/ml), the inhibition is moderate, while higher concentrations show a similar trend with some fluctuations. When compared to the positive control, Fluconazole, the Sertaconazole-mediated SN-CaCO₃ NPs are less effective overall, as Fluconazole displays consistently lower absorbance values, indicating stronger biofilm inhibition (

Figure 7).

The mechanism of action for SN-CaCO₃ NPs lies primarily in their ability to release Ca²⁺ ions, which can interfere with microbial cell wall integrity, disrupt biofilm structure, and impair the quorum sensing pathways essential for biofilm development. In addition, CaCO₃ NPs act as carriers for Sertaconazole, enhancing its solubility, stability, and targeted delivery to the biofilm. This combination allows the antifungal agent to effectively penetrate the biofilm matrix, disrupt fungal cell membranes, and inhibit cellular processes critical for biofilm sustainability. The negative surface charge of these nanoparticles, as indicated by the Zeta potential measurements, also aids in maintaining their stability in suspension and reduces aggregation, which improves bioavailability and interaction with the biofilm.

The implication of this study suggests that while SN-CaCO₃ NPs loaded with Sertaconazole have potential as biofilm inhibitors, further optimization is required to match or surpass the efficacy of established antifungals like Fluconazole. These nanoparticles hold promise as a novel drug delivery system that can target biofilm-associated infections more effectively by enhancing drug stability and biofilm penetration. Such a targeted approach is crucial in combating biofilm-forming pathogens, particularly in infections that are resistant to conventional therapies. Future research could explore adjustments in NP composition or modifications in Sertaconazole concentration to improve biofilm inhibition and broaden the scope of clinical applications for SN-CaCO₃ nanoparticles in antifungal treatments.

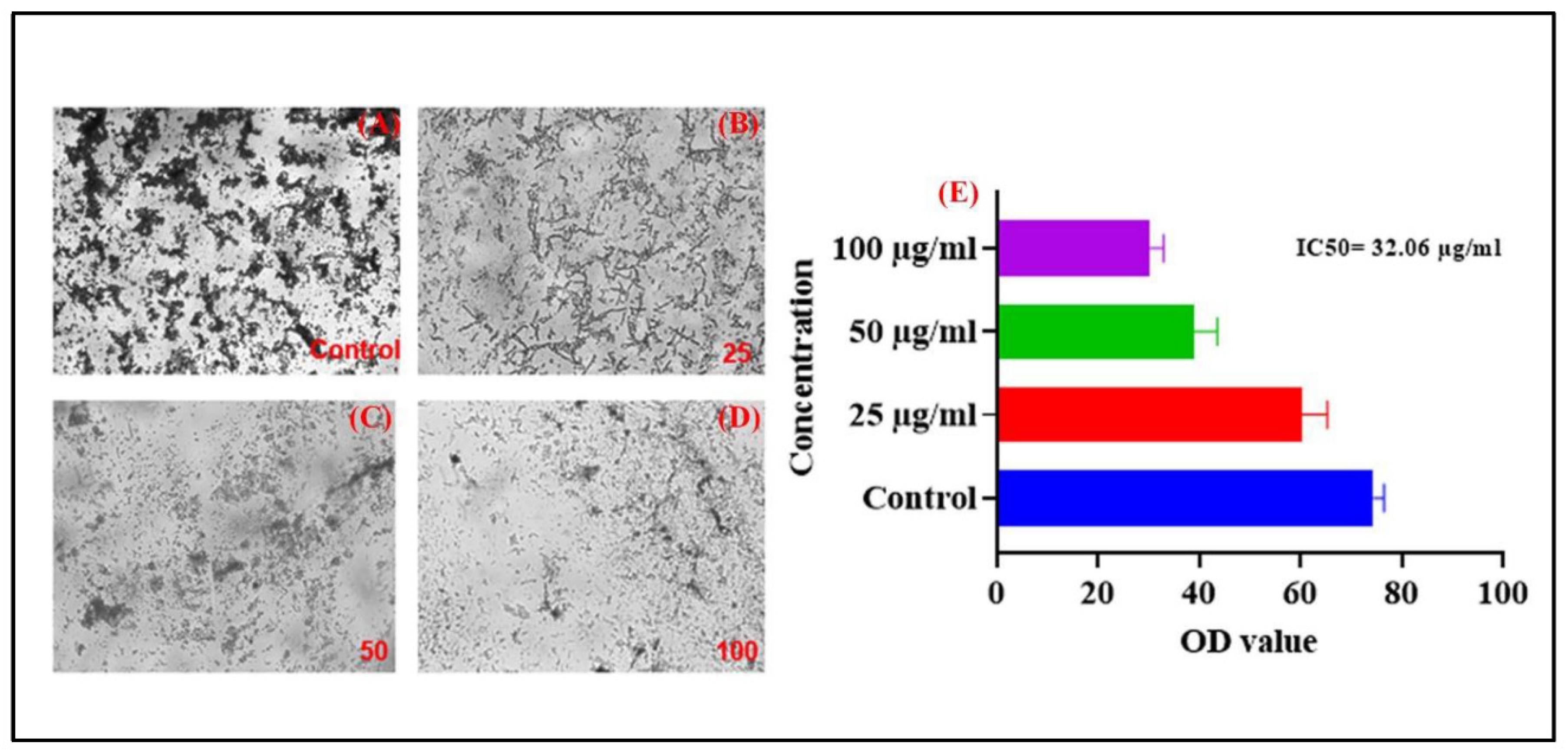

The results of the in vitro cytotoxicity assay provide insights into the potential toxic effects of A231 on mammalian cells, which is crucial for assessing its safety profile and potential therapeutic applications. Cytotoxicity assays are essential in drug development to evaluate the potential adverse effects of candidate compounds on human cells and tissues. The control group consisting of untreated cells demonstrated normal cell viability and proliferation, indicating the suitability of the assay conditions and the absence of any cytotoxic contaminants. This serves as a baseline for comparison with the treated cells to assess the cytotoxic effects of A231.Treatment with A231 resulted in dose-dependent cytotoxic effects as evidenced by the significant reduction in cell viability at higher concentrations. The observed decrease in cell viability indicates that A231 has the potential to induce cell death or inhibit cell proliferation in maximum concentration. The dose-dependent cytotoxic effects of A231 highlight the importance of carefully optimizing the compound concentration for therapeutic applications to minimize potential toxicity while maximizing efficacy. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of cytotoxicity induced by A231 and to determine its therapeutic window for safe and effective use in vivo. In our current study SN CaCO3 exhibit IC50 value 32.06 % which is expressed in graphical image (

Figure 8E) as well as morphology of cell shrinkage is shown (

Figure 8 A-D).

The evaluation of the Sertaconazole nitrate-loaded calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) vaterite carrier hydrogel revealed favorable physical characteristics that indicate its suitability for topical application. The hydrogel is milky white in color, has no odor, and exhibits a consistent texture, which are desirable attributes for patient acceptability. The pH of the hydrogel was measured at 5.9, close to the natural skin pH, minimizing the risk of skin irritation and making it suitable for dermatological applications.

The hydrogel’s viscosity was observed to be 5549 centipoise (cp), suggesting a thick yet manageable consistency that aids in uniform application and adherence to the skin without excessive run-off. This level of viscosity also indicates that the hydrogel can hold the drug in place, providing prolonged contact with the skin, which may enhance the drug’s effectiveness. Spreadability was recorded at 1.9 gm.cm/sec, indicating adequate ease of application while ensuring that the formulation covers the desired area effectively. Additionally, the hydrogel is washable, which adds to its user-friendliness, allowing easy removal when needed.

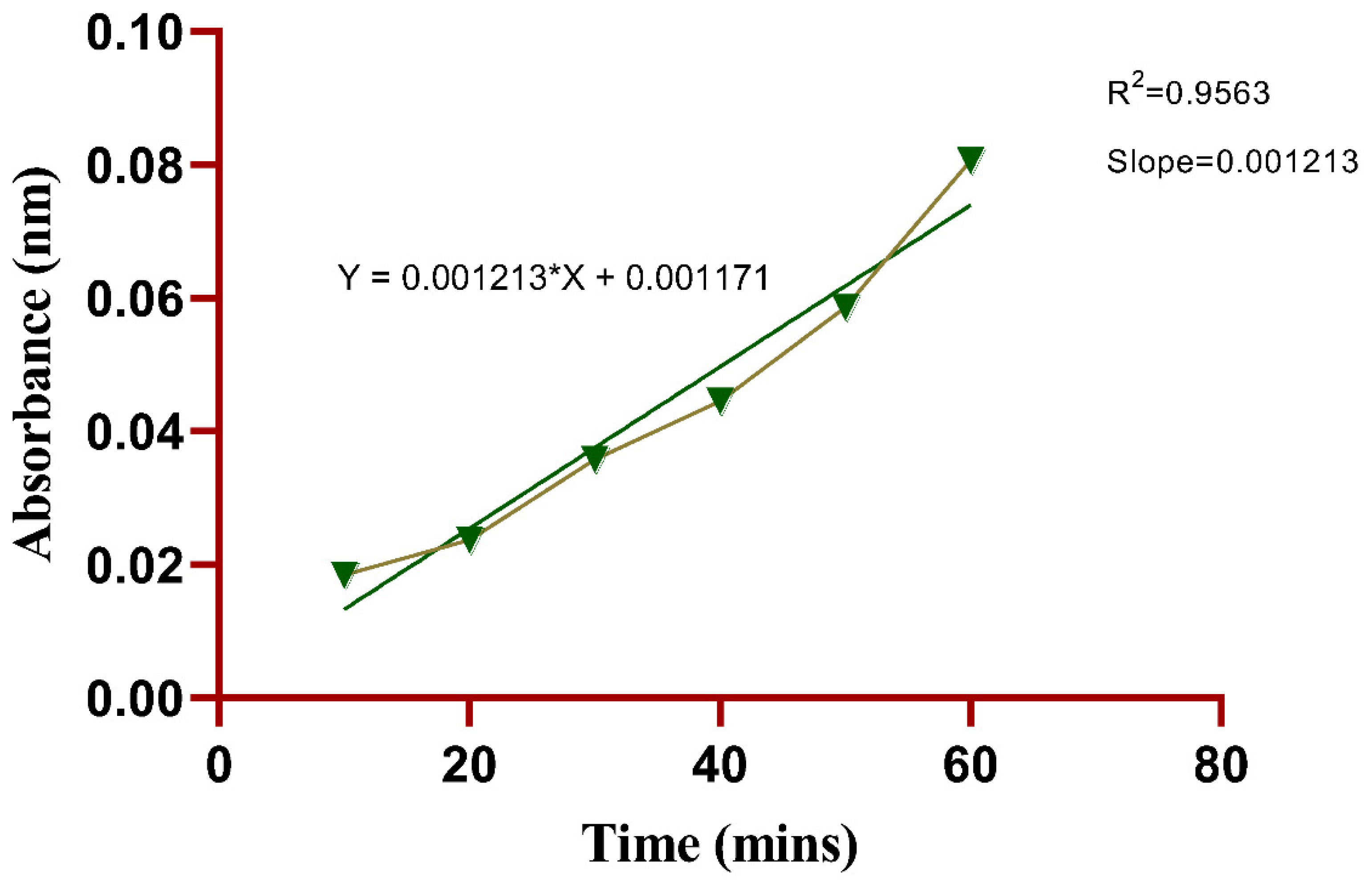

In evaluating the drug permeation of SN-CaCO3 nanoparticle-mediated hydrogel using the Franz diffusion method, the data indicates a consistent increase in absorbance over time, correlating with the permeation of the drug through the hydrogel barrier (

Figure 9). At the initial 10-minute mark, absorbance values across trials remain close to baseline, averaging 0.0184 nm, suggesting minimal permeation in the early stages. As time progresses, there is a steady increase in absorbance, with the 20-minute mark showing an average absorbance of 0.0237 nm, indicating early permeation of the drug. The trend continues with absorbance values rising steadily, reaching an average of 0.0358 nm by 30 minutes, which reflects enhanced permeation likely due to diffusion gradients stabilizing and allowing more consistent drug passage. At the 40- and 50-minute intervals, the increase remains steady, with mean absorbance values of approximately 0.0445 nm and 0.0586 nm, respectively. By 60 minutes, absorbance values reach the highest average of 0.0806 nm, suggesting a peak in permeation rate, where the hydrogel structure facilitates maximum drug diffusion. This progression indicates a stable and controlled drug release from the SN-CaCO3 NP-mediated hydrogel, demonstrating its potential for sustained drug delivery applications. The slight variations among trials reflect reproducibility while affirming the hydrogel’s effectiveness in modulating drug diffusion over time.

The synthesis and characterization of Sertaconazole nitrate-loaded CaCO₃ vaterite nanoparticles present a novel approach for improving antifungal efficacy through a nanoparticle-based drug delivery system. UV and FTIR analyses confirmed the structural integrity of SN and successful encapsulation in the CaCO₃ vaterite carrier. The SEM and TEM images validated the uniform morphology and nanometric size, which are ideal for targeted drug delivery. DLS and Zeta potential measurements indicated stability in suspension, essential for maintaining the bioavailability of SN-CaCO₃ NPs. The antifungal activity evaluation, particularly in biofilm inhibition assays, demonstrated that SN-CaCO₃ NPs significantly enhanced antimicrobial activity compared to SN alone. The formulation's cytotoxicity assays highlight a promising therapeutic window for targeted applications, particularly in combating biofilm-forming infections. Additionally, the topical hydrogel exhibited optimal pH, viscosity, and spreadability, making it suitable for skin application. This research underscores the potential of SN-CaCO₃ vaterite NPs as an effective, stable, and biocompatible antifungal agent for topical applications, suggesting a promising future in antifungal and biofilm-targeted therapies.

Author Contributions

BR, UU, RAMJ, and MI: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Software, editing, Investigation, Data curation. Finally, all the authors read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowlegements

We are grateful to the management and dean of Crescent School of Pharmacy, B S Abdur Rahman Crescent Institute of Science & Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India for providing all the necessary facility and lab facilities to conduct the research work.

References

- B. Elzein, “Nano Revolution: “Tiny tech, big impact: How nanotechnology is driving SDGs progress",” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 10, p. e31393, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Roth, N. M. Westrick, and T. T. Baldwin, “Fungal biotechnology: From yesterday to tomorrow,” Front. Fungal Biol., vol. 4, p. 1135263, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Moonjely, “Fungi: Essential Elements in the Ecosystems,” in The Impact of Climate Change on Fungal Diseases, M. G. Frías-De-León, C. Brunner-Mendoza, M. D. R. Reyes-Montes, and E. Duarte-Escalante, Eds., in Fungal Biology. , Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 19–35. [CrossRef]

- P. Budhwar, A. Malik, M. T. T. De Silva, and P. Thevisuthan, “Artificial intelligence – challenges and opportunities for international HRM: a review and research agenda,” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 33, no. 6, pp. 1065–1097, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Pokrajac et al., “Nanotechnology for a Sustainable Future: Addressing Global Challenges with the International Network4Sustainable Nanotechnology,” ACS Nano, vol. 15, no. 12, pp. 18608–18623, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Dhanjal et al., “Mycology-Nanotechnology Interface: Applications in Medicine and Cosmetology,” IJN, vol. Volume 17, pp. 2505–2533, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. A. R. Gow and M. D. Lenardon, “Architecture of the dynamic fungal cell wall,” Nat Rev Microbiol, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 248–259, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Mgadi, B. Ndaba, A. Roopnarain, H. Rama, and R. Adeleke, “Nanoparticle applications in agriculture: overview and response of plant-associated microorganisms,” Front. Microbiol., vol. 15, p. 1354440, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Wang, Y. Liu, C. Du, and R. Gao, “Current Strategies for Real-Time Enzyme Activation,” Biomolecules, vol. 12, no. 5, p. 599, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Khatoon, J. P. N. Rai, and A. Jillani, “Role of fungi in bioremediation of contaminated soil,” in Fungi Bio-Prospects in Sustainable Agriculture, Environment and Nano-technology, Elsevier, 2021, pp. 121–156. [CrossRef]

- N. M. Khalil, “Recent Progress on Fungal Enzymes,” in Plant Mycobiome, Y. M. Rashad, Z. A. M. Baka, and T. A. A. Moussa, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023, pp. 319–338. [CrossRef]

- V. Janakiraman et al., “Applications of fungal based nanoparticles in cancer therapy– A review,” Process Biochemistry, vol. 140, pp. 10–18, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Behar, S. Sharma, R. Parihar, S. K. Dubey, S. Mehta, and V. Pandey, “Role of fungal metabolites in pharmaceuticals, human health, and agriculture,” in Fungal Secondary Metabolites, Elsevier, 2024, pp. 519–535. [CrossRef]

- W. Ntow-Boahene, D. Cook, and L. Good, “Antifungal Polymeric Materials and Nanocomposites,” Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., vol. 9, p. 780328, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Usman et al., “Nanotechnology in agriculture: Current status, challenges and future opportunities,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 721, p. 137778, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Chaudhari, V. Vairagade, A. Thakkar, H. Shende, and A. Vora, “Nanotechnology-based fungal detection and treatment: current status and future perspective,” Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol, vol. 397, no. 1, pp. 77–97, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Chaurasia and S. L. Bharati, “Applicability of fungi in agriculture and environmental sustainability,” in Microbes in Land Use Change Management, Elsevier, 2021, pp. 155–172. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Wilson, T. Pretorius, and S. Naidoo, “Mechanisms of systemic resistance to pathogen infection in plants and their potential application in forestry,” BMC Plant Biol, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 404, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Garvey, E. Meade, and N. J. Rowan, “Effectiveness of front line and emerging fungal disease prevention and control interventions and opportunities to address appropriate eco-sustainable solutions,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 851, p. 158284, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Corona Ramirez et al., “Assessment of fungal spores and spore-like diversity in environmental samples by targeted lysis,” BMC Microbiol, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 68, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. A. Omran, “Fundamentals of Nanotechnology and Nanobiotechnology,” in Nanobiotechnology: A Multidisciplinary Field of Science, in Nanotechnology in the Life Sciences. , Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 1–36. [CrossRef]

- E. P. Stater, A. Y. Sonay, C. Hart, and J. Grimm, “The ancillary effects of nanoparticles and their implications for nanomedicine,” Nat. Nanotechnol., vol. 16, no. 11, pp. 1180–1194, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Asghar et al., “The application of Trichoderma spp., an old but new useful fungus, in sustainable soil health intensification: A comprehensive strategy for addressing challenges,” Plant Stress, vol. 12, p. 100455, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Wani, A. Rajput, and P. Pingale, “Herbal Nanoformulations: A Magical Remedy for Management of Fungal Diseases,” Journal of Herbal Medicine, vol. 42, p. 100810, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Borkowski, P. Działak, K. Berent, M. Gajewska, M. D. Syczewski, and M. Słowakiewicz, “Mechanism of bacteriophage-induced vaterite formation,” Sci Rep, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 20481, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Zafar, J. Campbell, J. Cooke, A. G. Skirtach, and D. Volodkin, “Modification of Surfaces with Vaterite CaCO3 Particles,” Micromachines, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 473, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. B. Trushina, T. N. Borodina, S. Belyakov, and M. N. Antipina, “Calcium carbonate vaterite particles for drug delivery: Advances and challenges,” Materials Today Advances, vol. 14, p. 100214, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Mehrotra and K. Pathak, “Controlled release drug delivery systems: principles and design,” in Novel Formulations and Future Trends, Elsevier, 2024, pp. 3–30. [CrossRef]

- X. San et al., “Unlocking the mysterious polytypic features within vaterite CaCO3,” Nat Commun, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 7858, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Wu, R. Song, T. Liu, and C. Li, “Antifungal therapy: Novel drug delivery strategies driven by new targets,” Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, vol. 199, p. 114967, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Ahsan et al., “Analytical Techniques for the Assessment of Drug Stability,” in Drug Stability and Chemical Kinetics, M. S. H. Akash and K. Rehman, Eds., Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2020, pp. 121–145. [CrossRef]

- C. Vogt, C. S. Wondergem, and B. M. Weckhuysen, “Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy,” in Springer Handbook of Advanced Catalyst Characterization, I. E. Wachs and M. A. Bañares, Eds., in Springer Handbooks. , Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023, pp. 237–264. [CrossRef]

- N. E. Eleraky, M. A. Attia, and M. A. Safwat, “Sertaconazole-PLGA nanoparticles for management of ocular keratitis,” Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, vol. 95, p. 105539, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Vladár and V.-D. Hodoroaba, “Characterization of nanoparticles by scanning electron microscopy,” in Characterization of Nanoparticles, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 7–27. [CrossRef]

- A. Wishard and B. C. Gibb, “Dynamic light scattering – an all-purpose guide for the supramolecular chemist,” Supramolecular Chemistry, vol. 31, no. 9, pp. 608–615, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Rasmussen, J. N. Pedersen, and R. Marie, “Size and surface charge characterization of nanoparticles with a salt gradient,” Nat Commun, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 2337, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. F. Ayodele et al., “Illustrated Procedure to Perform Molecular Docking Using PyRx and Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer: A Case Study of 10kt With Atropine,” Prog Drug Discov Biomed Sci, vol. 6, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Gizaw et al., “Phytochemical Screening and In Vitro Antifungal Activity of Selected Medicinal Plants against Candida albicans and Aspergillus niger in West Shewa Zone, Ethiopia,” Advances in Pharmacological and Pharmaceutical Sciences, vol. 2022, pp. 1–8, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Q. Yu, J. Li, Y. Zhang, Y. Wang, L. Liu, and M. Li, “Inhibition of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) on pathogenic biofilm formation and invasion to host cells,” Sci Rep, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 26667, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Timoszyk and R. Grochowalska, “Mechanism and Antibacterial Activity of Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) Functionalized with Natural Compounds from Plants,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 14, no. 12, p. 2599, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Ankudze and D. Neglo, “Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from peel extract of Chrysophyllum albidum fruit and their antimicrobial synergistic potentials and biofilm inhibition properties,” Biometals, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 865–876, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Coffey and G. G. Anderson, “Biofilm Formation in the 96-Well Microtiter Plate,” in Pseudomonas Methods and Protocols, vol. 1149, A. Filloux and J.-L. Ramos, Eds., in Methods in Molecular Biology, vol. 1149. , New York, NY: Springer New York, 2014, pp. 631–641. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Hawar, H. S. Al-Shmgani, Z. A. Al-Kubaisi, G. M. Sulaiman, Y. H. Dewir, and J. J. Rikisahedew, “Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Alhagi graecorum Leaf Extract and Evaluation of Their Cytotoxicity and Antifungal Activity,” Journal of Nanomaterials, vol. 2022, pp. 1–8, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Ejma-Multański, A. Wajda, and A. Paradowska-Gorycka, “Cell Cultures as a Versatile Tool in the Research and Treatment of Autoimmune Connective Tissue Diseases,” Cells, vol. 12, no. 20, p. 2489, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Imath et al., “Fioria vitifolia-mediated silver nanoparticles: Eco-friendly synthesis and biomedical potential,” Journal of Water Process Engineering, vol. 66, p. 106020, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Mosmann, “Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays,” Journal of Immunological Methods, vol. 65, no. 1–2, pp. 55–63, Dec. 1983. [CrossRef]

- A. Monks et al., “Feasibility of a High-Flux Anticancer Drug Screen Using a Diverse Panel of Cultured Human Tumor Cell Lines,” JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 83, no. 11, pp. 757–766, Jun. 1991. [CrossRef]

- R. Pascua-Maestro, M. Corraliza-Gomez, S. Diez-Hermano, C. Perez-Segurado, M. D. Ganfornina, and D. Sanchez, “The MTT-formazan assay: Complementary technical approaches and in vivo validation in Drosophila larvae,” Acta Histochemica, vol. 120, no. 3, pp. 179–186, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- I. Jayawardena, P. Turunen, B. C. Garms, A. Rowan, S. Corrie, and L. Grøndahl, “Evaluation of techniques used for visualisation of hydrogel morphology and determination of pore size distributions,” Mater. Adv., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 669–682, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. M. FitzSimons, E. V. Anslyn, and A. M. Rosales, “Effect of pH on the Properties of Hydrogels Cross-Linked via Dynamic Thia-Michael Addition Bonds,” ACS Polym. Au, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 129–136, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Bhattad, “Review on viscosity measurement: devices, methods and models,” J Therm Anal Calorim, vol. 148, no. 14, pp. 6527–6543, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. U. A. Khan, M. A. Aslam, M. F. B. Abdullah, W. S. Al-Arjan, G. M. Stojanovic, and A. Hasan, “Hydrogels: Classifications, fundamental properties, applications, and scopes in recent advances in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine – A comprehensive review,” Arabian Journal of Chemistry, vol. 17, no. 10, p. 105968, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Mehta, M. Sharma, and M. Devi, “Hydrogels: An overview of its classifications, properties, and applications,” Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials, vol. 147, p. 106145, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Sahoo, N. R. Pani, and S. K. Sahoo, “Microemulsion based topical hydrogel of sertaconazole: Formulation, characterization and evaluation,” Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, vol. 120, pp. 193–199, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- X. Deng, Z. Yang, K. W. Chan, N. Ismail, and M. Z. Abu Bakar, “5-Fluorouracil in Combination with Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles Loaded with Antioxidant Thymoquinone against Colon Cancer: Synergistically Therapeutic Potential and Underlying Molecular Mechanism,” Antioxidants, vol. 13, no. 9, p. 1030, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

UV analysis of synthesized Sertaconazole driven CaCO3 NPs.

Figure 1.

UV analysis of synthesized Sertaconazole driven CaCO3 NPs.

Figure 2.

FTIR analysis (A). FTIR spectrum for Sertaconazole nitrate, (B) FTIR spectrum for CaCO3 vaterite carrier, and (C) SN-CaCO3 NPs.

Figure 2.

FTIR analysis (A). FTIR spectrum for Sertaconazole nitrate, (B) FTIR spectrum for CaCO3 vaterite carrier, and (C) SN-CaCO3 NPs.

Figure 3.

(A) & (B) are SEM images of SN-CaCO3 NPs and (C) and (D) are TEM images of SN-CaCO3 NPs.

Figure 3.

(A) & (B) are SEM images of SN-CaCO3 NPs and (C) and (D) are TEM images of SN-CaCO3 NPs.

Figure 4.

(A) DLS particle size analysis for SN-CaCO3 NPs, and (B) Zeta potential charge and stability analysis peak of SN-CaCO3 NPs.

Figure 4.

(A) DLS particle size analysis for SN-CaCO3 NPs, and (B) Zeta potential charge and stability analysis peak of SN-CaCO3 NPs.

Figure 5.

In-silico molecular interactions of Sertaconazole against fungal pathogen. (A) 3D interaction, and (B) 2D interaction.

Figure 5.

In-silico molecular interactions of Sertaconazole against fungal pathogen. (A) 3D interaction, and (B) 2D interaction.

Figure 6.

Antifungal activity by well diffusion method. (A) Sertaconazole nitrate tested in agar well diffusion against C. albicans, (B) CaCO3 vaterite carrier against C. albicans, (C) enhanced SN-CaCO3 NPs against C. albicans, and (D) Zone of inhibition column plot with mean±SD, experiments are conducted in triplicates. The asterisk (*) denotes statistically significance while (*p<0.001) and (*p<0.0005) respectively.

Figure 6.

Antifungal activity by well diffusion method. (A) Sertaconazole nitrate tested in agar well diffusion against C. albicans, (B) CaCO3 vaterite carrier against C. albicans, (C) enhanced SN-CaCO3 NPs against C. albicans, and (D) Zone of inhibition column plot with mean±SD, experiments are conducted in triplicates. The asterisk (*) denotes statistically significance while (*p<0.001) and (*p<0.0005) respectively.

Figure 7.

Fungal biofilm eradication by microtiter plate assay. The column plot describes statistically significance analysed by One way ANOVA, which was denoted in alphabetical letters where, ‘a’ (p<0.05), ‘b’ (p<0.002), ‘c’ (p<0.0005) and ‘d’ (p<0.0001).

Figure 7.

Fungal biofilm eradication by microtiter plate assay. The column plot describes statistically significance analysed by One way ANOVA, which was denoted in alphabetical letters where, ‘a’ (p<0.05), ‘b’ (p<0.002), ‘c’ (p<0.0005) and ‘d’ (p<0.0001).

Figure 8.

Cytotoxicity assay of SN-CaCO3 NPs (A) Control (Untreated cells), (B) 25 μg/mL of SN-CaCO3 NPs treated with A231 cancer cells, (C) 50 μg/mL of SN-CaCO3 NPs treated with cells, (D) 100 μg/mL of SN-CaCO3 NPs treated with cancer cells and (D) The cell viability of SN-CaCO3 NPs was plotted in column graph with mean±SD.

Figure 8.

Cytotoxicity assay of SN-CaCO3 NPs (A) Control (Untreated cells), (B) 25 μg/mL of SN-CaCO3 NPs treated with A231 cancer cells, (C) 50 μg/mL of SN-CaCO3 NPs treated with cells, (D) 100 μg/mL of SN-CaCO3 NPs treated with cancer cells and (D) The cell viability of SN-CaCO3 NPs was plotted in column graph with mean±SD.

Figure 9.

Simple linear Regression plot of triplicated experiments possess Skin permeation (In vitro) upto 60 minutes.

Figure 9.

Simple linear Regression plot of triplicated experiments possess Skin permeation (In vitro) upto 60 minutes.

Table 1.

Molecular docking of Receptor against ligand with binding affinity and interactions.

Table 1.

Molecular docking of Receptor against ligand with binding affinity and interactions.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).