1. Introduction

Pedestrian travel offers a wide range of benefits for both individuals and society. From a transportation perspective, it reduces vehicle travel, leading to lower air pollution, reduced CO2 emissions, and fewer environmental impacts (Cao, Handy, & Mokhtarian, 2006). From a local economic perspective, more pedestrians mean higher footfall and greater growth for local businesses. From a public health standpoint, walking increases physical activity, which improves health and reduces healthcare costs (Lee & Buchner, 2008). Countries with higher levels of active transportation often have the lowest obesity rates (Bassett, Pucher, Buehler, Thompson, & Crouter, 2008).

Planners and public health officials have therefore promoted policies that enhance the pedestrian environment through mixed land uses, interconnected street networks, street lighting, and other facilities (Cao et al., 2006). A growing number of empirical studies have examined the relationship between the built environment and pedestrian behaviour [e.g., (Cao et al., 2006; Ferrer, Ruiz, & Mars, 2015; Frank & Engelke, 2001)], providing evidence of such correlations.

Lighting is recognised as one of the environmental factors affecting pedestrians’ perceptions of security and reassurance, and it may encourage walking at night [see e.g., (Bopp et al., 2006; Heath et al., 2006; Kaparias, Bell, Miri, Chan, & Mount, 2012; Pain, MacFarlane, Turner, & Gill, 2006; Saelens & Handy, 2008)]. While the presence of street lighting has been consistently ranked highly among environmental determinants of walking (Pikora, Giles-Corti, Bull, Jamrozik, & Donovan, 2003), there remains a lack of evidence linking the quality and quantity of street lighting with actual pedestrian behaviour at night. Most studies have focused only on pedestrians’ cognitions and emotions under controlled conditions [see e.g., (Boyce, Eklund, Hamilton, & Bruno, 2000; Haans & de Kort, 2012; Rea, Bullough, & Brons, 2015)].

Few studies have investigated whether—and under what circumstances—such cognitions and emotions translate into behaviour change, such as avoiding streets after dark. For example, does a sense of insecurity caused by inadequate or ineffective street lighting lead pedestrians to avoid certain streets (or walking altogether) at night? Under which lighting conditions does this sense of insecurity remain purely cognitive, and under which does it dissipate? Put differently, what thresholds of street lighting quality or quantity must be met before pedestrians alter their behaviour at night?

The purpose of this paper is to highlight the importance of environmental factors, particularly street lighting. It reports on a pilot study that explores changes in pedestrian street use at night compared with the day, as well as the key factors influencing these changes. This pilot draws on qualitative and quantitative data from residents of two residential areas in Tehran, Iran, and addresses the question of whether specific qualities and quantities of street lighting affect people’s walking behaviour after dark.

2. Method

2.1. Study Settings

Two residential areas in Tehran, Iran, were studied. Although both sites are residential, they differ in terms of density, land use, and socio-economic characteristics. Land-use mix (diversity of uses and access to facilities) and residential density are recognised as key aspects of creating walkable neighbourhoods (Frank & Pivo, 1994). Based on these factors, one of the neighbourhoods selected for this study exhibits higher walkability characteristics (Case Study 2), while the other demonstrates lower walkability (Case Study 1).

The presence of other people—identified as one of the most important reassurance factors at night (Craig, Brownson, Cragg, & Dunn, 2002; Ferrer, Ruiz, & Mars, 2015; Fotios, Unwin, & Farrall, 2014)—was also considerably higher in Case Study 2 than in Case Study 1. The rationale for selecting these sites was to explore the validity of walkability and reassurance factors after dark, and to examine whether lighting quality and quantity influence these factors.

2.1.1. Case Study 1

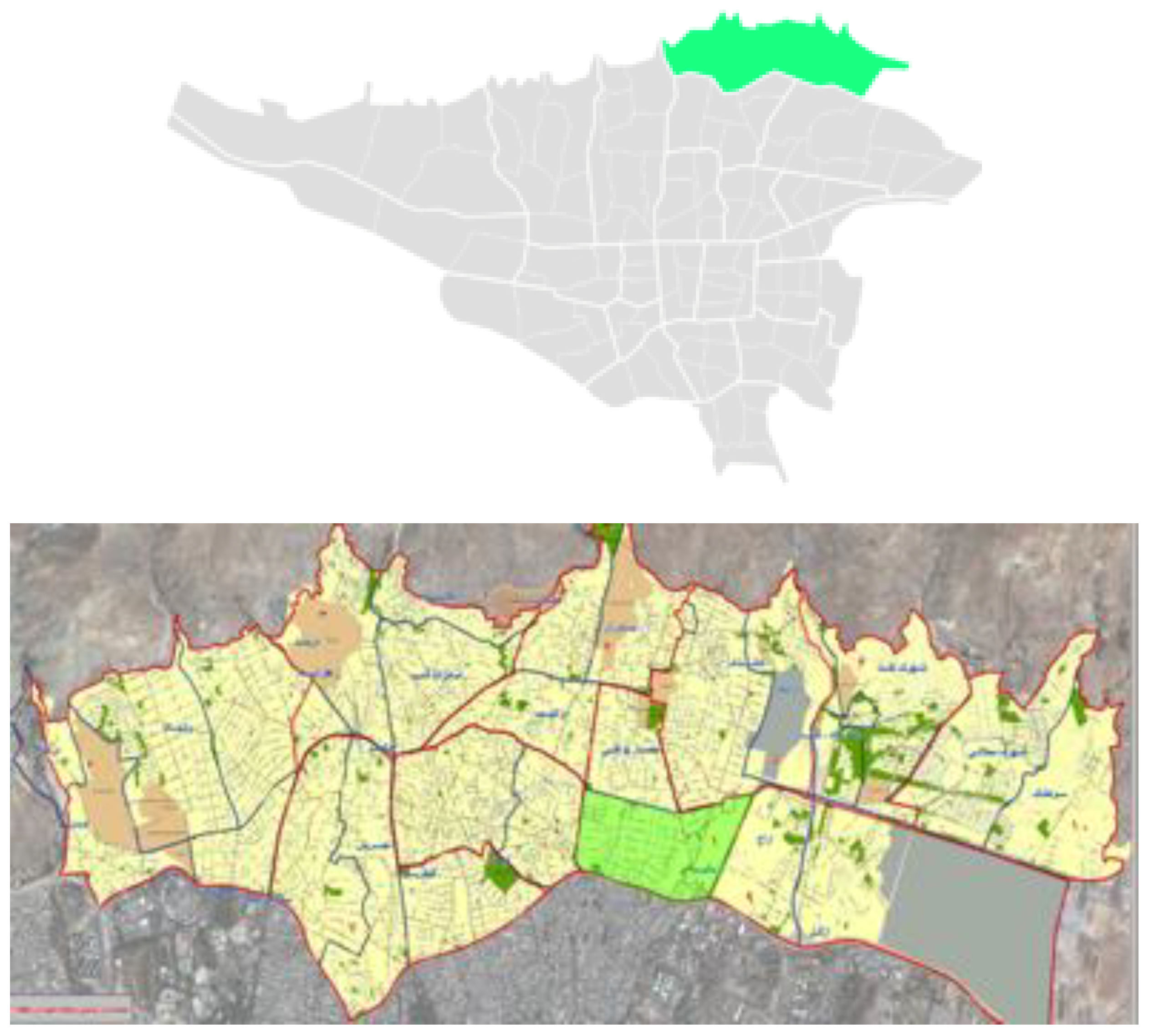

Case Study 1 is situated in Region 1, in the northern part of Tehran adjacent to the Alborz Mountains (

Figure 1). With a population density of 6,875 people per square kilometre, this area is among the least densely populated regions of the city. Historically semi-rural in character, the neighbourhood has undergone substantial transformation over the past two decades, with new developments replacing much of the vernacular fabric with a modern urban form. Nevertheless, certain sections of Region 1 continue to exhibit semi-rural characteristics. The site surveyed for this study is located within the developed urban area.

According to Iran’s national statistics website (2015), Region 1 records the highest level of social welfare among all regions of Tehran. The land-use pattern is predominantly residential, with only a limited presence of commercial, retail, and administrative functions.

2.1.2. Case Study 2

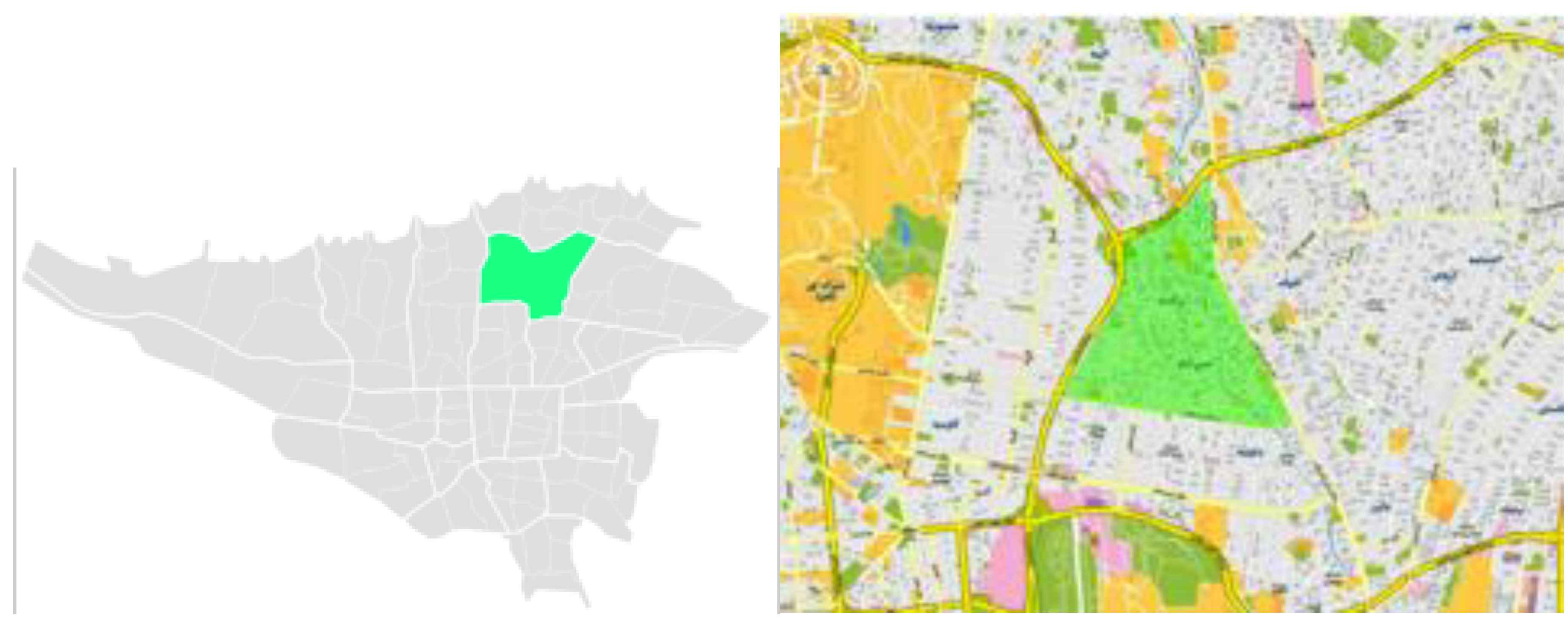

Case Study 2 is located in Region 3, in the north-eastern part of Tehran (

Figure 2). With a population density of 15,239 people per square kilometre, this area ranks among the most densely populated regions of the city. The original urban fabric was similar to that of Case Study 1; however, owing to its more central location within Tehran, Region 3 underwent significant redevelopment in 1955, shifting from an organic pattern to a modern urban design. According to Iran’s national statistics website (2015), Region 3 ranks sixth in Tehran’s classification of social wealth and economy. Compared with Case Study 1, this area contains a greater proportion of commercial, retail, and administrative buildings, and demonstrates a higher degree of land-use mix.

2.2. Behavioural Observation

Behaviour is defined as the way in which an individual responds to a particular situation. Behavioural observation refers to the systematic collection of behavioural data while subjects engage in specific activities under defined conditions, followed by the assessment of the collected data (Ciminero, Calhoun, & Adams, 1986). Such data may be evaluated for a range of purposes, including the description of behaviour, the design or selection of behavioural correction strategies, and the evaluation of the effectiveness of those strategies.

Ciminero et al. (1986) identify three primary approaches to behavioural observation: self-report, direct behavioural observation, and psychophysiological recording. The self-report approach encompasses data obtained through behavioural interviews, questionnaires and inventories, as well as self-monitoring procedures. For the purposes of this study, the self-report method was employed, combining interviews with questionnaires.

2.2.1. Procedure

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with residents in the two study areas. Respondents were first asked to indicate, on a schematic map of the area, a walking route they typically used during the day. They were then asked whether they would take the same route at night for the same purpose, or whether they would choose an alternative route. Respondents were also given the option of indicating that they would use another mode of transport, such as a private car, or that they did not use the streets at night. Where respondents reported a change in route or mode of transport, they were asked to provide reasons for this decision. Importantly, no direct mention of street lighting, darkness, or safety/security was made by the researcher during the interviews.

The streets identified as being used by respondents during the day and at night were subsequently surveyed to document lighting conditions, land use, and general route characteristics (see Appendix 1).

2.3. Objective Measurements

Objective measures of the built environment have been widely examined to understand their influence on walking behaviour (Badland & Schofield, 2005; Cervero & Kockelman, 1997; Handy & Clifton, 2001; Rodríguez & Joo, 2004). For instance, Cervero and Kockelman (1997) demonstrated that higher density, greater land-use diversity, and pedestrian-oriented designs are associated with reduced automobile trip rates and increased walking and cycling. The presence—or absence—of other people has also been identified as an influential factor in route choice and walking behaviour (Craig, Brownson, Cragg, & Dunn, 2002; Ferrer, Ruiz, & Mars, 2015).

Lighting conditions have similarly been shown to play a role, with both the amount and uniformity of illuminance affecting perceived personal safety [e.g., (Boyce, Eklund, Hamilton, & Bruno, 2000; Knight, 2009)]. Street width is another influential factor in safety perceptions: narrow alleys are generally perceived as more dangerous than wider ones (Herzog & Flynn-Smith, 2001).

2.4. Participants

A total of 28 residents, aged between 18 and 71 years (M = 43.4), from the selected study areas were interviewed. Demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 1.

3. Results

3.1. Interviews

Table 2 presents the destinations of participants for each walk, along with the number who reported changing their route at night, those who maintained the same route, and those who opted to use private cars instead. As shown, the proportion of residents who did not alter their routes or means of transportation at night was substantially higher in Case Study 2 than in Case Study 1.

Table 3 summarises participants’ reasons for selecting or avoiding particular routes at night. The

access to help category (Fotios, Unwin, & Farrall, 2014) includes factors such as the presence of other people in the streets, shops remaining open at night, or a preference for walking with companions. This factor is closely related to residential density, as denser neighbourhoods are more likely to have people present in the streets.

The street lighting category reflects whether specific routes were described as bright or dark, while the width of street category captures preferences for main roads and avoidance of narrow streets. In Case Study 1, two-thirds of daytime walking routes were narrow (less than 8 m wide) and comprised shared spaces, whereas all routes in Case Study 2 were wide (greater than 14 m) and had designated pedestrian pavements. Shared space is defined here as a street with reduced motor vehicle dominance, where all users share the same space rather than follow the clearly delineated rules characteristic of conventional designs. Such environments signal to pedestrians the potential presence of vehicles while requiring drivers to engage more actively with their surroundings due to the likelihood of pedestrian activity (Kaparias, Bell, Miri, Chan, & Mount, 2012).

In both study areas, main roads were characterised by higher vehicular and pedestrian traffic as well as higher illumination levels. Concerns about trip hazards were expressed primarily by older participants, specifically those aged 60–69.

Table 4 presents the changes in walking behaviour and car use among older participants. Of the eleven older pedestrians, seven (63%) reported changing their route or mode of transportation at night, compared with 41% of younger participants. The table also indicates that 21% of all residents (6 out of 28) chose to use a private car at night for destinations they typically reached on foot during the day.

3.2. Surveys

Figure 3 illustrates sample routes taken by participants to the same destination during the day and at night. Based on these maps, a lighting survey of the identified routes was subsequently conducted (see

Appendix 1,

Table 1 and

Table 2).

Table 4 summarises the survey conducted across both sites, based on the interview results. A Mann–Whitney test was applied to compare pavement illuminance levels between the sites. The analysis revealed no significant difference in pavement illuminance between the two sites (p > 0.05). The test was also employed to examine whether illuminance levels differed significantly across the four route categories presented in

Table 5. No significant differences were found between Site 1 and Site 2 for

changed routes (routes used during the day but avoided at night) or

unchanged routes (routes used both during the day and at night), with p > 0.05. However, alternative routes selected at night exhibited significantly higher illuminance levels (p < 0.05).

In addition, the Mann–Whitney test was used to compare street width across the different route categories.

4. Discussion

The behavioural observation method was employed in this study to provide additional insights beyond those offered by conventional experimental approaches. A key advantage of behavioural observation is that it is conducted in real-life situations, allowing researchers to capture the context and meaning underpinning what people say and do. This approach is particularly valuable in circumstances where manipulation of independent variables, such as street lighting, is not feasible. It also avoids the artificial conditions that experimental studies may create.

Findings from this study demonstrate that the neighbourhood with higher walkability elements (Frank & Pivo, 1994) during the day and stronger reassurance factors at night (e.g., access to help; Fotios, Unwin, & Farrall, 2014) exhibited the lowest rates of route change, street avoidance, or substitution with car use at night. Despite the influence of multiple walkability and reassurance factors, street lighting emerged as the primary reason cited by residents for altering their night-time routes.

An important finding is that, although the two study sites differ considerably in terms of land-use mix, residential density, access to help, and street width, the illuminance levels of the rejected routes were the same in both cases. In other words, while Case Study 2 benefitted from stronger walkability and reassurance factors compared with Case Study 1, the threshold of light level at which residents changed their behaviour remained constant across both contexts. This suggests that perceived brightness or darkness operates independently of other reassurance and walkability factors in shaping behavioural decisions. Specifically, a minimum light level appears to be required for pedestrians to continue using streets at night. In the study areas, routes with an average pavement illuminance of 4–5 lux were rejected, while those with approximately 8 lux were used consistently during both day and night.

The results further indicate that age plays a significant role. While it is already established that age correlates with substitutive walking behaviour during the day (Piatkowski, Krizek, & Handy, 2015), this study shows that the quality of street lighting influences older pedestrians’ behaviour to a much greater extent than that of younger pedestrians (

Table 4). From a purely visual performance perspective, the light levels in both case study areas were sufficient to support safe walking. However, perceptions of safety and security were more salient among older participants, who more frequently reported adapting their behaviour because it made them feel safer, and who more often expressed doubts about their own abilities (Bernhoft & Carstensen, 2008).

The study also found a 21% increase in the use of private cars at night compared with the day for the same destinations, suggesting that inadequate street lighting may influence modal choice. It should be noted, however, that the sample size was small, and the generalisability of these findings requires confirmation through further research.

5. Conclusion

The primary aim of this study was to examine whether street lighting influences walking behaviour at night. The behavioural observation method was employed to provide insights beyond those offered by previous experimental studies in this field. The findings indicate that, irrespective of other environmental factors, street lighting is the principal determinant of changes in residents’ night-time walking behaviour.

Results further suggest that a minimum lighting level is required to prevent such behavioural changes. This threshold appears to operate independently of both broader environmental factors (e.g., walkability and reassurance) and the minimum requirements for visual performance. The effect is particularly pronounced among older pedestrians, whose behaviour was significantly more sensitive to lighting conditions than that of younger participants. In addition, the study identified a 21% increase in the use of private cars at night for journeys typically made on foot during the day, underscoring the wider implications of inadequate street lighting for travel behaviour.

Appendix 1

Table 1.

– Street lighting survey: Routes taken during day, Site 1.

Table 1.

– Street lighting survey: Routes taken during day, Site 1.

| Route ID |

Average width of streets (m) |

Average illuminance on pavements (lux) |

Average distance between light poles (m) |

Lamp

type |

Average height of light poles (m) |

Used at night? |

| 1 |

7.5 |

7 |

12 |

HPS |

10 |

Yes |

| 2 |

14 |

3 |

12 |

HPS & MH |

10 |

Yes |

| 3 |

9 |

5 |

10.0- 15.0 |

HPS & MH |

10 |

Yes |

| 4 |

16.5 |

14.5 |

12.0-15.0 |

HPS |

10 |

Yes |

| 5 |

10 |

2 |

12 |

MH |

12 |

No |

| 6 |

5.6 |

3.5 |

11 |

HPS |

10 |

No |

| 7 |

5.6 |

3.5 |

11 |

HPS |

10 |

No |

| 8 |

7.5 |

7 |

12 |

HPS |

10 |

No |

| 9 |

7.9 |

1.5 |

10 |

MH |

10 |

No |

| 10 |

5.9 |

2 |

12 |

HPS & MH |

10 |

No |

| 11 |

16.5 |

14 |

10 |

HPS |

10 |

No |

| 12 |

16 |

1 |

15 |

MH |

10 |

No |

| 13 |

14 |

14 |

10 |

HPS |

10 |

No |

| 14 |

7.5 |

4 |

12 |

HPS |

10 |

No |

Table 2.

Street lighting survey: Routes taken during day, Site 2.

Table 2.

Street lighting survey: Routes taken during day, Site 2.

| Route ID |

Average width of streets (m) |

Average illuminance on pavements (lux) |

Average distance between light poles (m) |

Lamp

type |

Average height of light poles (m) |

Used at night? |

| 15 |

18.2 |

8 |

10 |

HPS & MH |

12 |

Yes |

| 16 |

14 |

6 |

10 |

HPS |

12 |

Yes |

| 17 |

18.3 |

8 |

12 |

HPS & MH |

10 |

Yes |

| 18 |

14 |

6 |

10 |

HPS |

12 |

Yes |

| 19 |

16 |

10 |

15 |

HPS |

10 |

Yes |

| 20 |

18.3 |

8 |

12 |

HPS & MH |

10 |

Yes |

| 21 |

16 |

10 |

15 |

HPS |

10 |

Yes |

| 22 |

16 |

10 |

15 |

HPS |

10 |

Yes |

| 23 |

16 |

10 |

15 |

HPS |

10 |

Yes |

| 24 |

18.2 |

4 |

12 |

HPS & MH |

10 |

Yes |

| 25 |

16 |

5 |

12 |

MH |

10 |

No |

| 26 |

16 |

4 |

12 |

HPS |

10 |

No |

| 27 |

18.2 |

8 |

12 |

MH |

10 |

No |

| 28 |

18.2 |

6 |

10 |

HPS |

12 |

No |

References

- Badland, Hannah M, & Schofield, Grant M. (2005). The built environment and transport-related physical activity: what we do and do not know. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 2(4), 433-442. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, David R, Pucher, John, Buehler, Ralph, Thompson, Dixie L, & Crouter, Scott E. (2008). Walking, cycling, and obesity rates in Europe, North America, and Australia. J Phys Act Health, 5(6), 795-814. [CrossRef]

- Bernhoft, Inger Marie, & Carstensen, Gitte. (2008). Preferences and behaviour of pedestrians and cyclists by age and gender. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 11(2), 83-95. [CrossRef]

- Bopp, Melissa, Wilcox, Sara, Laken, Marilyn, Butler, Kimberly, Carter, Rickey E, McClorin, Lottie, & Yancey, Antronette. (2006). Factors associated with physical activity among African-American men and women. American journal of preventive medicine, 30(4), 340-346. [CrossRef]

- Boyce, Peter R, Eklund, Neil H, Hamilton, Barbara J, & Bruno, Lisa D. (2000). Perceptions of safety at night in different lighting conditions. Lighting Research and Technology, 32(2), 79-91. [CrossRef]

- Boyce, PR, Eklund, NH, Hamilton, BJ, & Bruno, LD. (2000). Perceptions of safety at night in different lighting conditions. Lighting Research and Technology, 32(2), 79-91. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Xinyu, Handy, Susan L, & Mokhtarian, Patricia L. (2006). The influences of the built environment and residential self-selection on pedestrian behavior: evidence from Austin, TX. Transportation, 33(1), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Cervero, Robert, & Kockelman, Kara. (1997). Travel demand and the 3Ds: density, diversity, and design. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 2(3), 199-219.

- Ciminero, Anthony R, Calhoun, Karen S, & Adams, Henry E. (1986). Handbook of behavioral assessment: Wiley New York.

- Craig, Cora L, Brownson, Ross C, Cragg, Sue E, & Dunn, Andrea L. (2002). Exploring the effect of the environment on physical activity: a study examining walking to work. American journal of preventive medicine, 23(2), 36-43.

- Ferrer, Sheila, Ruiz, Tomás, & Mars, Lidón. (2015). A qualitative study on the role of the built environment for short walking trips. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour, 33, 141-160. [CrossRef]

- Fotios, Steve, Unwin, Jemima, & Farrall, Stephen. (2014). Road lighting and pedestrian reassurance after dark: A review. Lighting Research and Technology, 1477153514524587. [CrossRef]

- Frank, Lawrence D, & Engelke, Peter O. (2001). The built environment and human activity patterns: exploring the impacts of urban form on public health. Journal of Planning Literature, 16(2), 202-218. [CrossRef]

- Frank, Lawrence D, & Pivo, Gary. (1994). Impacts of mixed use and density on utilization of three modes of travel: single-occupant vehicle, transit, and walking. Transportation research record, 44-44.

- Haans, Antal, & de Kort, Yvonne AW. (2012). Light distribution in dynamic street lighting: Two experimental studies on its effects on perceived safety, prospect, concealment, and escape. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32(4), 342-352.

- Handy, Susan L, & Clifton, Kelly J. (2001). Local shopping as a strategy for reducing automobile travel. Transportation, 28(4), 317-346. [CrossRef]

- Heath, Gregory W, Brownson, Ross C, Kruger, Judy, Miles, Rebecca, Powell, Kenneth E, Ramsey, Leigh T, & Services, Task Force on Community Preventive. (2006). The effectiveness of urban design and land use and transport policies and practices to increase physical activity: a systematic review. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 3, S55. [CrossRef]

- Herzog, Thomas R, & Flynn-Smith, Jennifer A. (2001). Preference and perceived danger as a function of the perceived curvature, length, and width of urban alleys. Environment and Behavior, 33(5), 653-666. [CrossRef]

- Kaparias, Ioannis, Bell, Michael GH, Miri, Ashkan, Chan, Carol, & Mount, Bill. (2012). Analysing the perceptions of pedestrians and drivers to shared space. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour, 15(3), 297-310. [CrossRef]

- Knight, C. (2009). Effect of lamp spectrum on perception of comfort and safety. Paper presented at the Proceedings of experiencing light 2009: International conference on the effects of light on wellbeing.

- Lee, I-Min, & Buchner, David M. (2008). The importance of walking to public health. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 40(7 Suppl), S512-518. [CrossRef]

- Pain, Rachel, MacFarlane, Robert, Turner, Keith, & Gill, Sally. (2006). ‘When, where, if, and but’: qualifying GIS and the effect of streetlighting on crime and fear. Environment and Planning A, 38(11), 2055-2074. [CrossRef]

- Piatkowski, Daniel P, Krizek, Kevin J, & Handy, Susan L. (2015). Accounting for the short term substitution effects of walking and cycling in sustainable transportation. Travel Behaviour and Society, 2(1), 32-41. [CrossRef]

- Pikora, Terri, Giles-Corti, Billie, Bull, Fiona, Jamrozik, Konrad, & Donovan, Rob. (2003). Developing a framework for assessment of the environmental determinants of walking and cycling. Social science & medicine, 56(8), 1693-1703. [CrossRef]

- Rea, MS, Bullough, JD, & Brons, JA. (2015). Parking lot lighting based upon predictions of scene brightness and personal safety. Lighting Research and Technology, 1477153515603758. [CrossRef]

- Rodrı́guez, Daniel A, & Joo, Joonwon. (2004). The relationship between non-motorized mode choice and the local physical environment. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 9(2), 151-173. [CrossRef]

- Saelens, Brian E, & Handy, Susan L. (2008). Built environment correlates of walking: a review. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 40(7 Suppl), S550.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).