1. Introduction

Due to the population growth and human development, the environment is experimenting severe problems including climate change (temperature increase, sea level elevation), soil, water, and air pollution, biodiversity loss, overharvesting, and deforestation, among others. Consequences of environmental damage affect direct or indirect human being. Pollution can lead to public health problems, such as respiratory illnesses or waterborne diseases. Economic impacts in agriculture, livestock farming, fishing, or tourisms has been observed. Problems regarding resource scarcity, food chains affection, as well as environmental disasters are increasing worldwide. To overcome this problematic a multidisciplinary approach should be developed and implemented, whereas the greenhouse gas emissions mitigation, renewable energies use, pollution reduction, as well as natural habitats remediation should be in focus.

Anaerobic digestion (AD) has been widely used for the simultaneous green energy production and waste management. Together with the energy production in form of biogas, anaerobic digestate results after AD process. This digestate is nutrient-rich and can be used as a valuable fertilizer, due to its content of essential nutrients for plant growth. On the other side, mycoremediation refers to the use of fungi for removal or break down of pollutants from soil and water. Fungi, i.e. mycorrhiza or endophytic fungi have the capacity to degrade pollutants like heavy metals or pesticides, so that they are less harmful for the environment. Digestate could be used for a better fungi growth and thus a more efficient pollutant mycoremediation. Few researches have been carried out regarding this topic. This systematic review explores the scientific research done during the last ten years regarding the effect of anaerobic digestate as soil amendment to achieve better or more efficient rates of soil remediation through fungal strains.

1.1. Anaerobic Digestion Process

AD comprises a series of biochemical reactions in which different bacterial consortia break down organic matter into individual components, forming a mixture of gas called biogas [

1]. Biogas is described as a byproduct of microbial metabolism, whereas different microorganisms convert organic matter almost entirely into biogas [

2,

3]. In principle, all kind of organic matter that is degraded under anaerobic conditions is suitable for biogas production, i.e. poultry droppings, agricultural crop wastes, or cattle manure [

2]. However, not all organic matter components can be broken down by the same bacterial strains. Biomass with high woody substance are slowly decomposed, due to lignin content. The organic material used to produce biogas is called substrate. The substrate´s chemical composition, in particular carbohydrates, fats, and protein content, is decisive for the amount of biogas produced and its methane content.

As in (CH

4: methane, CO

2: carbon dioxide, H

2: hydrogen), the process of biogas production is divided in four steps; hydrolysis, acidification (acidogenesis), acetic acid formation (acetogenesis), and methane formation (methanogenesis). During the hydrolysis, the complex compounds of biomass (carbohydrates, proteins, and fats) are broken down into simpler organic compounds. Proteins become amino acids, carbohydrates become sugars, and fats become fatty acids. The hydrolytic bacteria involved in this process release enzymes that biochemically decompose material. In the acidification step, acid-forming bacteria break down the intermediate products in lower fatty acids like acetic, propionic, and butyric acid, as well as carbon dioxide and hydrogen. In addition, small amounts of lactic acid and alcohols are also formed. During the acetogenesis, products derived from acidogenesis are then converted by acetogenic bacteria into biogas precursors such as acetic acid, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide. In this step, water content can negatively affect the process. An excessively high hydrogen content prevents the conversion of the intermediate products for energetic reasons. Products which inhibit methane formation could be formed, such as organic acids, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, isovaleric acid, as well as caproic acid. For this reason, acetogenic bacteria (hydrogen producers) must be in close association with hydrogen-consuming methanogenic archaea, which consume hydrogen together with carbon dioxide in order to form methane, and thus ensure acceptable environmental conditions for acetic acid-producing bacteria. During the methanogenesis, acetic acid, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide are mainly converted into methane by strictly anaerobic methanogenic archaea. Hydrogenotrophic methanogens produce methane from hydrogen and carbon dioxide, whereas the acetoclastic methanogens form methane by acetic acid division. It can be said that around 70 % of methane comes from acetic acid decomposition, and only 30 % from hydrogen utilization [

3,

4].

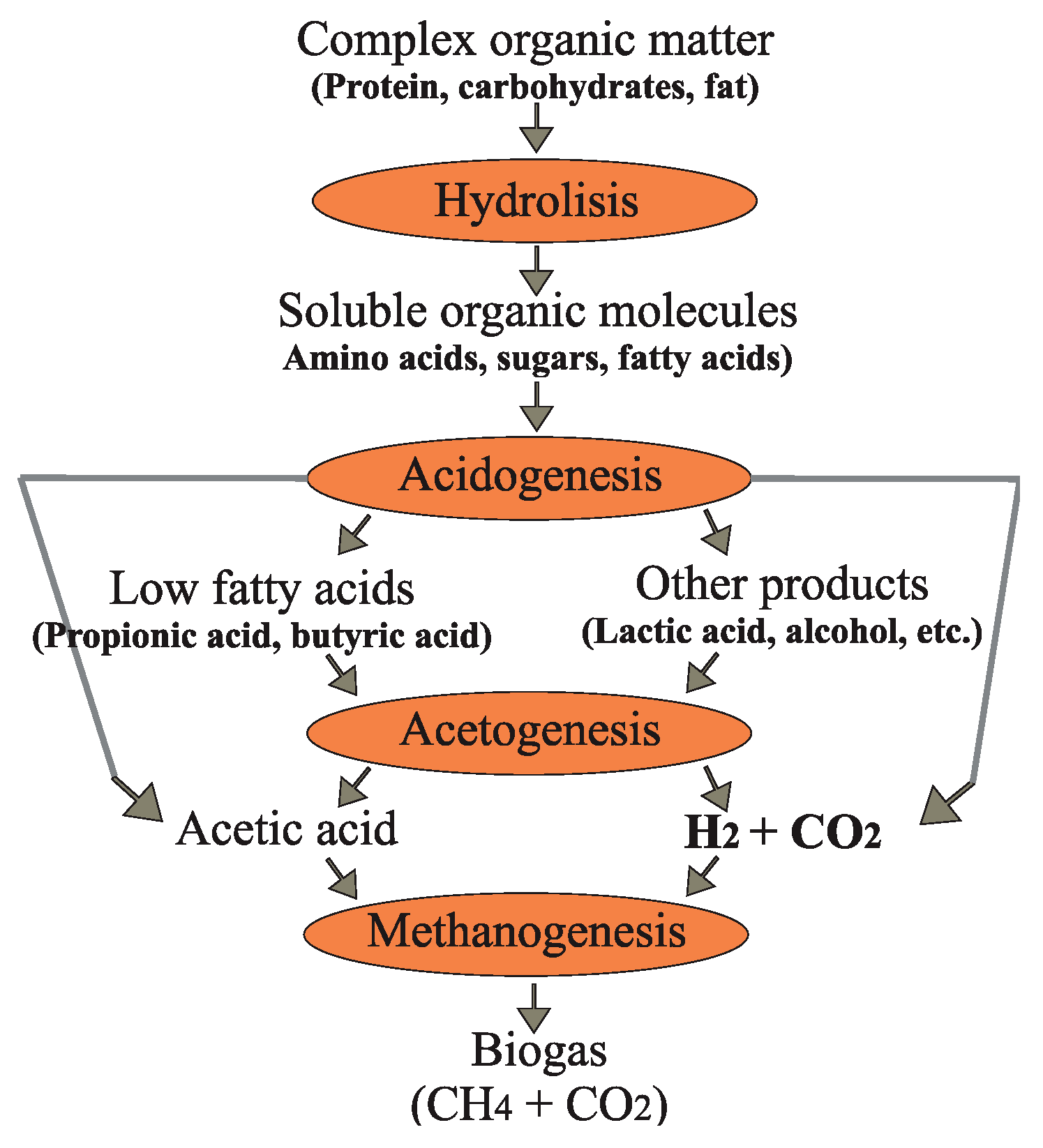

Figure 1.

Stages in biogas production (CH4: methane, CO2: carbon dioxide, H2: hydrogen).

Figure 1.

Stages in biogas production (CH4: methane, CO2: carbon dioxide, H2: hydrogen).

The different bacterial strains multiply at different speeds. The so-called doubling time is the time it takes for a bacterial population to double in size [

5]. Bacterial strains belonging to the first two steps, hydrolysis and acidogenesis, have a remarkable slower generation time, than methanogenic bacteria. Doubling time of bacteria strains involved during the biogas production is shown in

Table 1 [

5].

Key factors to achieve the well-being of different bacterial strains, and thus efficient anaerobic digestion processes, should be put down in focus. Key factors to consider inside the bioreactor are temperature, oxygen, pH-value, nutrient supply, as well as inhibitory substances. Operating parameters which should be monitored during the AD process are hydraulic retention time or time that a substrate remains in the bioreactor (d), organic matter room load (kg·m

-3·d

-1), CH

4 productivity (m

CH43·m

-3·d

-1), CH

4 yield (m

3·t

-1), biomass degradability (%), and mixing of substrate in bioreactor. The composition of biogas can only be influenced to a limited extent by targeted process control. It primarily depends on the composition of the input material [

3].

1.2. Biogas Composition

Biogas composition may vary, but in general it contains methane (CH

4), carbon dioxide (CO

2), water (H

2O), hydrogen sulfide (H

2S), nitrogen (N

2), and hydrogen (H

2), as shown in

Table 2 [

3].

Regarding the quality of the gas mixture, the concentration of hydrogen sulfide (H

2S) plays an important role. H

2S is found in biogas as a trace gas in very small amounts, as is shown in

Table 2. Firstly, it should not be too high, since even low concentrations of this gas inhibit the degradation process. Secondly, high H

2S concentrations in biogas lead to corrosion damage in combined heat and power plants and boilers during use [

3,

6].

The methane content is of primary importance, as it represents the combustible portion of biogas, and thus directly influences its calorific value. The achievable yield of methane is essentially determined by the composition of the substrate used, mainly the proportion of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates. The specific methane yields of the aforementioned groups of substances decrease in the order mentioned. A higher methane yield can be achieved with fats than with carbohydrates [

3].

Table 3 shows the specific biogas yield and methane content of the corresponding substance group [

3].

Few biogas plants practice mono-digestion, which means the digestion of only one kind of substrate. Most of anaerobic digesters use different crops or seasonal substrates, what guarantees the effectiveness of the AD process, increasing digester loading capacity and methane production. This ameliorates the buffer capacity, lowering pH level within methanogenesis, contributing in a better nutrient balance, i.e., C/N ratio (carbon:nitrogen ratio), among others [

6]. Ref. [

7] suggested that the hydraulic retention time (HRT) and temperature in bioreactor are interconnected; as temperature increases, HRT decreases. Both parameters are very important for pathogen inactivation.

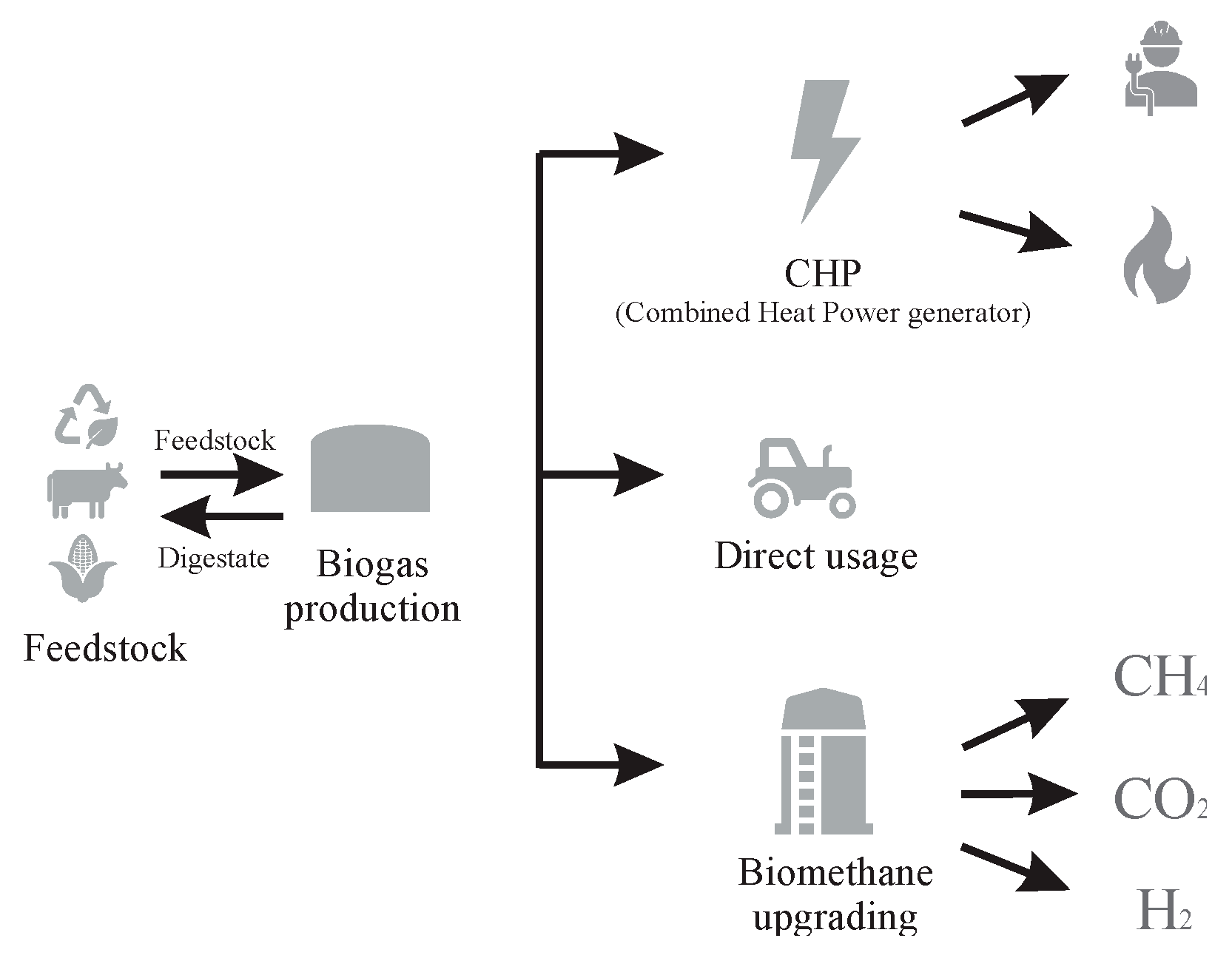

1.3. Use of Biogas

The produced biogas can directly be used as a cooking fuel, or be injected in a co-generator (CHP) for the simultaneous heat and power generation. Also, CH

4 content in biogas can be enriched to upgrade biogas to biomethane, so that it can be used with minimal modifications as natural gas. Finally, biogas can be used to produce value-added chemicals used in energy or industrial processes [

2,

4,

6,

8].

Figure 2, modified from [

8], shows the different pathways for biogas utilization.

Biogas is thus a clean energy source, which contributes to reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. [

2] reported that in Switzerland 8 % of renewables energies was produced from biogas. The use of biogas can also diminish the use of firewood for cooking. It was reported by [

2] that for 2040 about 200 million people will use biogas as cooking biofuel in Asia and Africa, contributing to the social development of emerging and developing lands [

2,

6]. In 2018, it was reported that China was the biggest biogas producer worldwide. Around 50 million small scale bioreactors are found, as well as 4000 farm scale and 2500 industrial scale reactors. India is also reported to have many small scale biogas plants, and Europe has an expanding tendency of biogas production [

6]. In year 2022, [

4] contabilized around 132000 biogas plants worldwide, being 17783 in European countries with an installed capacity of 10.5 GW. Also 700 biogas plants for biomethane upgrading were found, whereas almost 80 % of them were located in Europe. After 2005, the number of biogas plants increased tremendously, especially in Germany, France, Switzerland and Holland [

4].

Some biowastes such as sludges, manures, or agricultural residues, are being dispread in agricultural soils as biofertilizers or in open up landfills. The continual disposal of residues in soils can lead to accumulation of both, nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorous or potassium, or even heavy metals, leading to negative impacts in health of pasture-raised cattle [

4]. Besides, the use of biowastes disposal in soils implies a significant contamination source, whereas landfill gases consisting of volatile organic compounds, CH

4, and CO

2 are released in the environment indiscriminately. Landfill gases have a great impact in ozone layer depletion [

4].

AD could be successfully used for the optimal biowastes conversion to bioenergy in form of biogas, or even as biofertilizer. After biogas production, a partially stabilized wet suspension of less or even non-degradable materials, remains as residue [

4]. The remining residue is called anaerobic digestate, and can be used in agricultural soils as a biofertilizer, guaranteeing necessary nutrients for humus and soil structure maintenance, and thus crop growth [

6].

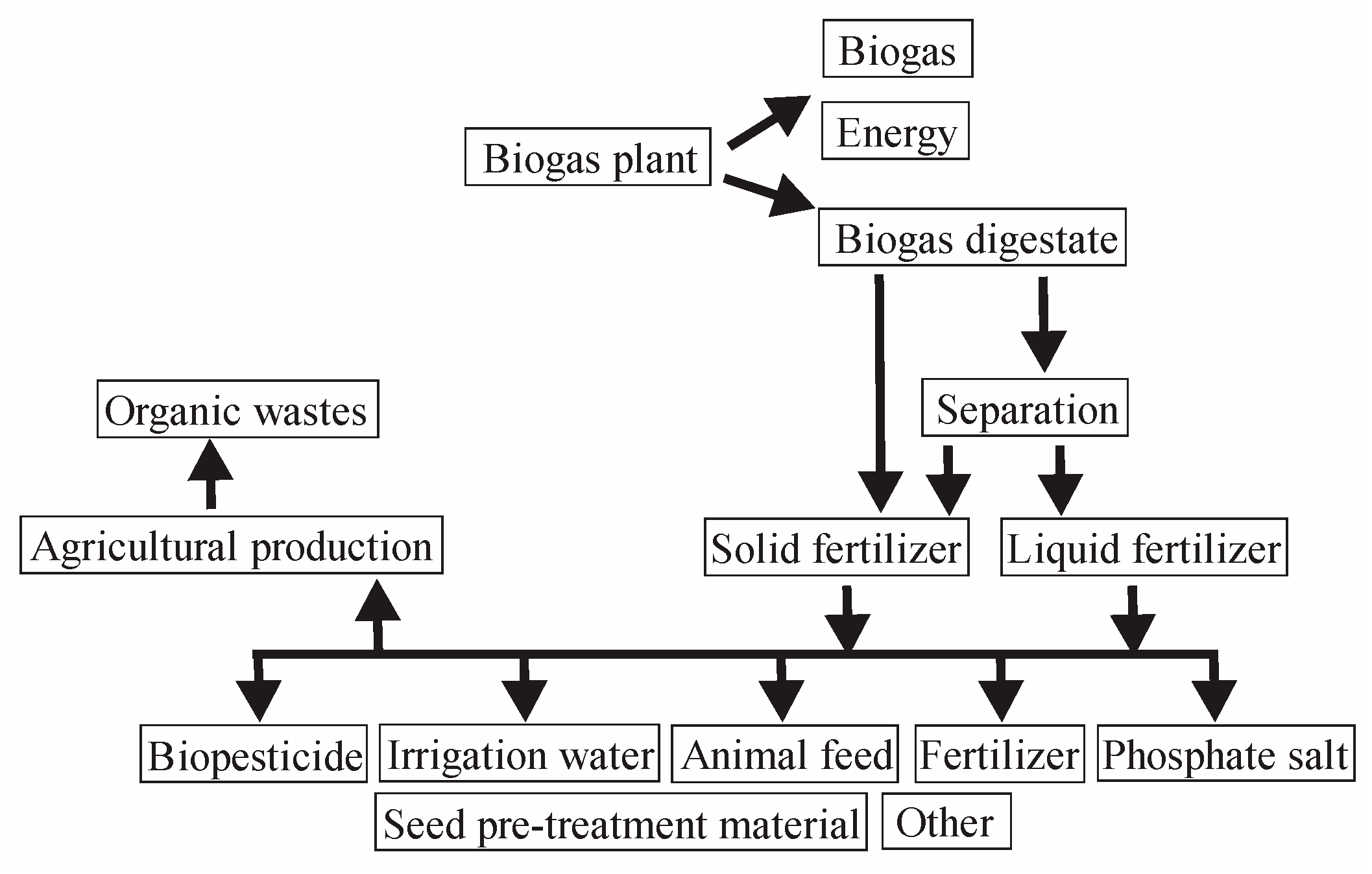

1.4. Anaerobic Digestate

As already pointed out, biogas digestate is reach in beneficial nutrients for plant growth. Nutrient content and properties depend on the biogas plant input material and the operation parameters used. Crucial factors affecting digestate quality are bacterial activity, water and nutrient content, C/N-ratio in input material, particle size and concentration, inhibitory or toxic compounds, pH, oxygen presence, microbial composition, as well as reactor temperature, design, and mixing [

9,

10,

11]. Several authors have reported that biogas digestate is a valuable product, it can be used for plant and animal nutrition, seed germination, irrigation, water obtention, or even for gaining bio-pesticides, phosphate salt, as well as carbon [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Figure 3 shows the possible uses of biogas digestate according to [

7].

When using digestate as biofertilizer, the biostability of the digestate should be taken in consideration, that means that digestate should not include pathogens or a high organic matter content, so that it should not be hazardous for living things. The main factor influencing the digestate biostability is the bioreactor temperature. After AD, mass content decreased by 90 – 95 %. Besides, when comparing digestate with cattle manure, pathogenic populations of

E. coli, and

Salmonella sp. were present in manure, whereas digestate run at mesophilic temperatures showed almost no pathogens [

18]. The only disadvantage of sanitization is the loss of N in ammonia, what can be overcome by adding ammonium sulfate in digestate [

7].

As already pointed out, AD substrate affects directly the biogas production yield as well as the digestate characteristics. When digesting urban residues, the amount of heavy metals in digestate, i.e. Cu, Zn, Cr, Cd, Pb, As, Ba, Ni, Co, Mn, Pt, and Sb, could be found in toxic concentrations, so that its use as biofertilizer is not recommended. According to [

19], dry matter, organic matter, pH, N, P, Cd, Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn, Hg, and Cr, should be analyzed in anaerobic digestate at least every six months. Limit values of trace elements (TE) in anaerobic digestate for agricultural use as fertilizer are limited to six elements showed in

Table 4.

To avoid this problematic, risk might be minimized reducing contaminant factors through denitrification applications and membrane filtration [

7]. Furthermore, remediation techniques could be carried out to diminish the concentration of heavy metals in soils.

1.5. Mycoremediation

Mycoremediation is a remediation method whereby fungi are used to degrade or remove polluted ecosystems. Mycorrhiza refer to the mutualistic associations of plant roots and mycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhizal fungal hyphae, which makes up the body of a mycorrhiza fungus, is fixed to plant roots and soil particles building filaments which tolerate contaminants such as heavy metals, leading to plant adaptation to nutriment diminishment, as well as temperature or pH modifications [

20]. Mycorrhizal fungi are found in roots of many plants. These symbiotic associations benefit the host plants, whereas water or soil nutrients uptake is enhanced, particularly P and N contents. Furthermore, mycorrhiza fungi collaborate with other soil microorganisms enhancing nutrient absorption [

21,

22]. The structure and function of mycorrhizal associations are wide, there are arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM), ectomycorrhiza (EcM), ectendomycorrhiza, arbutoid mycorrhiza, monotropoid mycorrhiza, ericoid, and orchid mycorrhiza. Amongst them, AM and EcM are the most common, moreover AM fungi has an economical and ecological importance. AM fungi are used as biofertilizers and cannot be cultivated without a host plant. The intracellular hyphal network of EcM shows more extensive associations than AMF [

21]. AMF could either increase heavy metal (HM) uptake and transport from roots to shoot, or stabilize HM in roots and shoots, diminishing uptake. Some authors report that AMF could accumulate HMs in a nontoxic form within the roots of the plant and in the extracellular mycelia [

21].

1.5.1. Effects of HM in Soils

HMs presence in soils could be hazardous for plants and consumers, when found over safe and tolerable limits. High concentrations of HM show a negative effect on microorganisms and microbial processes, leading to plant growth reduction. HM could land in soils by different ways, i.e. fossil fuels, mining and smelting, municipal wastes, and use of fertilizers or pesticides [

23,

24,

25]. Furthermore, some metals like Zn, Cu, Mn, Ni, and Co are essential for plant growth and are considered micronutrients, other metals such as Cd, Pb, or Hg does not show any biological function [

25]. An excessive concentration of HM can induce to metabolic disruptions in plants, altering cellular activities and affecting nutrient uptake, plant development, or even inducing reactive oxygen species production. This could be reflected in poor plant growth, turgor stem pressure reduction, leaf chlorosis, seed germination drop, and senescence [

23]. Metals could be found in soils in different forms such as free ions, soluble complexes, exchangeable ions, precipitated or insoluble oxides, carbonates and hydroxides, or even as silicate materials. The toxic effects of metals depend on their ability to be transferred from the soil to living organisms, so called bioavailability, and it depends on physico-chemical and biological factors [

25].

1.5.2. Mycorrhiza for Metal Remediation

As already pointed out, mycorremediation refers to degrading or removing contaminants from the environment, using fungi cultivated in a host plant. It is an economic and effective alternative to reduce concentrations of soil contaminants. Metal-tolerance plants are being used to extract HM from soils, translocating and accumulating into shoots, leaves, and other structures. When colonizing these plants with mycorrhizal fungi, greater plant growth, protective mechanisms and buffer capacity for abiotic stress can be achieved. Several studies have shown an increase of metal uptake in plants inoculated with AMF, especially regarding As, Cr, Cd, Pb, Zn, Mn, Cu, Al, and Co. Thereby, an increased metal content in roots, shoots, and fronds was found, so that phytoextraction could easily take place [

21,

23].

In soils heavily contaminated with HMs, plant colonization through mycorrhiza has been detected. Several authors report high levels of mycorrhizal colonization in agricultural soils polluted with heavy metals [

25].

Plant AMF tolerance may take place due to different factors. On the one hand, a higher nutrient (especially P) uptake lead to higher plant growth, and thus higher biomass availability for metal distribution within the plant. On the other hand, AMF-assisted plants have the capacity to bioaccumulate metals, hindering their translocation to shoots and roots [

23,

26,

27].

Mycorremediation could be used as a low-cost alternative for soil remediation, showing beneficial effects on plant growth, metal attenuation, and productivity.

1.5.3. Use of Anaerobic Digestate in Mycoremediation

As already mentioned, anaerobic digestate is the substance remaining after anaerobic digestion to biogas and biomethane production. Thus, anaerobic digestate is rich in nutrients and can be used as biofertilizer or even as soil amendment. Digestate has the potential to ameliorate biological, chemical and physical soil properties, i.e. by pH-adjustment or soil aggregation and boosting, influencing soil microbiota and enzymatic activity [

28].

In the rhizosphere, a nutrient interchange between plants and microorganisms takes place. In any case, microorganisms composition depends on the soil management techniques [

28]. Anaerobic digestate could be applied in soils where mycorrhiza colonize plant roots, promoting a better soil nutrient adsorption, especially regarding P and N. [

12] reported that AM fungi has the capacity to change soil characteristics, whereby AMF filamentous hyphae causes that plants reach water and nutrients more extensively in the soil, reducing the irrigation needs and the use of chemical fertilizers. It has been proved that the combination of anaerobic digestate with mycorrhiza has beneficial impacts for soil nutrient and organic carbon contents, resulting in a more efficient plant growth [

29]. Furthermore, the application of biogas digestate derive in a higher fungi or mycorrhizal root colonization, augmenting symbiotic benefits for plant development, even in polluted soils whereas plants can adapt better to stress [

12,

19,

28,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

1.6. Fundamental Framework

Further studies should be carried out regarding the influence of digestate on soils inoculated with mycorrhiza, in order to understand changes in structure and composition of mycorrhiza, as well as soil nutrient accessibility and mycorremediation potential.

The present paper comprehends a systematic review related to the scientific research done the past 10 years regarding the use of anaerobic digestate for fungi cultivation and mycorrhizal colonization for soil remediation. The effects of digestate application and fungi colonization in soil nutrients/contaminants behavior, microbial community, as well as plant growth and organic matter removal, are discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

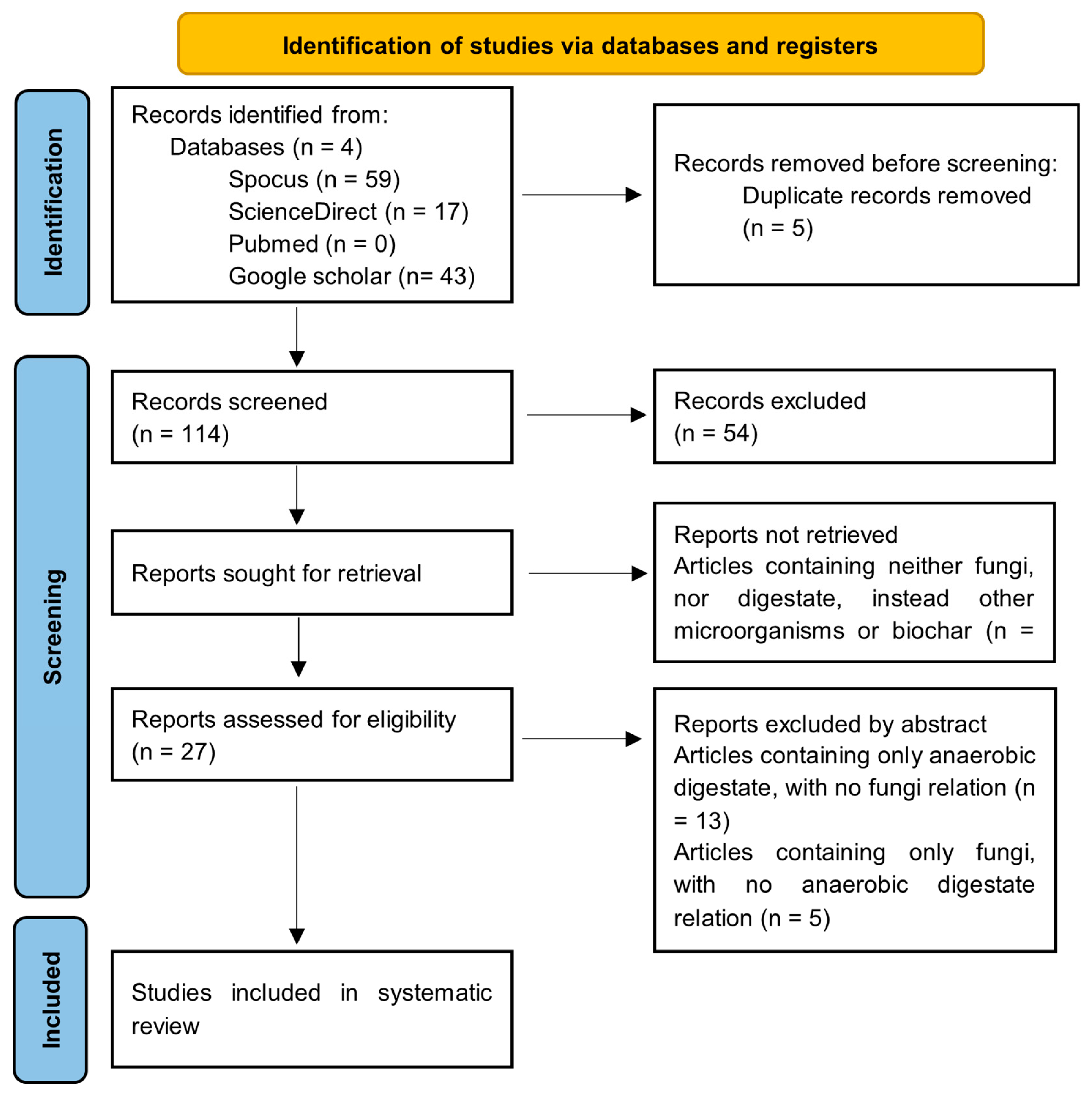

In order to enhance reliability, transparency, and integrity of the report, PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines were followed for the development of the present review.

2.1. Articles Selection

An initial search was carried out for English-language scientific articles published between years 2015 and 2025 in databases SCOPUS, SCIENCE DIRECT, PUBMED and on GOOGLE SCHOLAR using Boolean operators AND and OR. Different combination of terms were used with the Boolean connectors, corresponding to each used platform, as shown in

Table 5.

In total, 119 articles were initially found, whereupon the inclusion and exclusion criteria were stablished.

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

In order to include the articles for the systematic review, only empirical research within years 2015 and 2025 were included. Only articles with scientific experimental techniques were considered.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

Review articles, chapters, manuals or books were excluded. Articles were also excluded, when the main topic was not related neither to anaerobic digestate and its use for fungal growth, nor to the use of anaerobic digestate as soil amendment for plant growth or for soil remediation.

2.1.3. Systematic Search

Duplicates generated due to the use of different databases were excluded, so that five duplicates out of 119 articles were found. A total of 114 articles were screened, from which 54 articles were excluded due to the publication type, at this point only empirical research was considered, leaving only 60 papers. From these 60 papers, 33 of them were not retrieved, because they contained neither fungi, nor digestate information, instead they described other microorganisms, bacteria, or biochar use for soil remediation. From the remaining 27 papers, 18 were excluded because they considered soil remediation either only with fungi or only with digestate, but they did not consider the simultaneous application of both. At the end, only nine research articles were left, including four articles regarding fungi growth in anaerobic digestate and five papers about the effect of mycorrhizal fungi and digestate application for plant growth or soil remediation.

Figure 4 summarizes the PRISMA flow diagram resulted after every stage of the article’s selection process.

The use of anaerobic digester for fungal growth, for both improvement of plant development as well as soil remediation, has not been widely researched, although there is existing literature demonstrating that digestate can be used as soil amendment for mycoremediation, whereas fungi cultivation in anaerobic digestate could give a reference of how fungi development takes place under substrates derived from anaerobic digestion. When considering the publication years of the articles accepted, between 2015 and 2020 only two articles were published, whereas the last five years, seven articles regarding the topic were found. This fact represents the necessity to find new methods for soil remediation.

The results of the systematic search are presented below beginning with mycoremediation, and the countries contributing to this research regarding the use of fungi for soil remediation, and the most commonly techniques used.

3. Results and Discussion

From the total of 119 articles found at the first steps of the systematic research, only nine articles, which means 8 %, deal with the inoculation or cultivation of fungi in anaerobic digestate, looking forward to understand their existing symbiosis between plant growth and/or metal remediation. In order to understand the influence of anaerobic digestate in fungi, articles regarding two main topics were included. On the one hand, five articles were considered regarding the inoculation of fungi in anaerobic digestate in order to evaluate plant growth or pollutant removal. On the other hand, four articles referring to fungi cultivation in anaerobic digestate and its influence in contaminant removal were included.

As already pointed out, anthropogenic activities trigger the accumulation of pollutants in soils, whereas the increasingly accretion of these elements become hazardous for the environment and human health. To overcome this problematic, biological, chemical, and physical methods of metal remediation have been developed, nevertheless many of these technologies are expensive and can indeed affect soil structure and microbiome. Phytoremediation stands for a cost effective and environmentally friendly method, through which plants and microbiome interact in order to remove, immobilize, or degrade heavy metals in soils. Metal tolerant plants are grown in contaminated soils, so that metal spread can be diminished and the soil surfaced can be stabilized. This strategy is called phytostabilization and has the disadvantage to be slow, due to the time span required for plant growth. Also, the biomass accumulating HMs represent a disposal problem. To overcome this problematic, sowing metal tolerant plants inoculated with microbiota resistant to HM toxicity, has been introduced in the past years, being defined as bioaugmentation-assisted phytoremediation. Microbiota used for this purpose is plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) or arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi (AMF) [

34].

Ref. [

28] reported that AMF provide P and other nutrients to plants receiving carbohydrates in exchange, and protecting them from drought and pathogens. AMF has shown the ability to change the bacterial community composition, furthermore, AMF hyphae has been pointed out to capture different bacterial strains, which otherwise would affect plant nutrient uptake and growth. [

19] reported that during colonization, fungi mycelium decomposes growing substrate secreting enzymes which have the capacity of breaking down organic matter into simpler compounds. Besides, fungi can accumulate trace elements, or even dissolve metals through root exudates.

On the other hand, the demand of food production increases as the worldwide population grows. This intensifies the necessity to supply agricultural soil with organic or inorganic fertilizers. Soil fertilization, even as a forest management practice, contributes in soil fertility preservation, enhancing microbial populations and enzymatic activity. However, a continuously soil fertilization with inorganic N and P fertilizers could enhance N and P accumulation resulting in negative ecological effects such as soil acidification, eutrophication, and biodiversity loss [

28].

Ever since the anaerobic digestion for biogas production has been widely used in the past years, the resulting digestate has been pointed out as an efficient and low-cost organic soil fertilizer. Anaerobic digestate can be used as soil amendment and could improve the physical, chemical, and biological soil properties, neutralizing soil pH, boosting soil´s total N, and augmenting both, soil microbial community composition, and enzymatic activities [

28].

Biogas digestate is rich in organic P and N nutrients, it is supposed to contribute to plant growth and AMF colonization. Nevertheless, some authors suggested that using anaerobic digestate could affect AMF species richness and diversity [

28]. The effects of anaerobic digestate as soil amendment on AMF communities has not been widely studied. Information should be investigated regarding the influence of organic fertilizers in symbiotic fungus, especially focusing in how rhizosphere structure and microbiome composition influence soil nutrient availability, plant growth, and even pollutant removal.

In order to have a deeper understanding on the mechanisms of fungi colonization in anaerobic digestate, research articles regarding fungi cultivation in anaerobic digestate were included in the systematic review.

Table 6 and

Table 7 show a summary of the scientific literature resulted from the systematic review.

Table 6 focuses on the articles regarding fungi cultivation in anaerobic digestate and

Table 7 on the digestate as soil amendment for plant growth and pollutant removal.

The effects of digestate application on soils has been analyzed through the present study. Effect of the biomass source for the digestate obtention, the fungal strains, organic matter removal and plant growth, as well as the microbial communities formed and fungi colonization are summarized in the following subchapters. These results confirm the necessity of studying further the topic, for the successfully remediation of polluted sites. A deeper analysis of the pollutants to be removed, the available fungal strains, and the digestate conditions need to be tested in the specific required cases.

3.1. Biomass Source for Anaerobic Digestion

Biomass source utilized during the process of anaerobic digestion is a key factor for nutrient availability. From the articles considered, only four articles used digestate from the solely anaerobic digestion of cattle manure [

12,

28,

32,

35].

Table 8 shows the results of different biomass source used in the digestate. [

19] and [

31] used digestate from co-digesting cattle manure and food waste, and only [

33] compared the effect of using only cattle manure anaerobically digested and the co-digestion of cattle manure with food wastes. Edible fungus has been successfully grown in anaerobic digestate, due to the C, P, and N contents, as well as nutrient availability. [

33] compared fungi growth in anaerobic digestate from only manure and from manure and food wastes. The second one resulted in a higher nutrient availability, whereas a higher content of K, Ca, Fe, Mg, Mn, and Na was found. Nevertheless, mycelium colonization and fungi yield were lower, due to the relatively food waste salt content and thus higher conductivity. On the other side, TN, B, Cu, and Zn were higher in digestate from only manure.

Ref. [33] reported that when cultivating fungi in anaerobic digestate, C/N/P ratios varied according to digestate concentrations. C/N ratios of 44:1 to 55:1 resulted in the most effective growth yield. The most successfully N/P ratio was reported 4:1 to 12:1. N/P ratio was affected when increasing digestate concentration. These facts suggest that digestate source and concentration should be adjusted for an efficient fungi and plant growth, as well as remediation rates.

3.2. Fungal Strains Researched

Nutrient availability depends greatly on the fungi species. Primarily

, A. bisporus and

A. subrufescens were studied for antibiotics, anticonvulsant as well as PFAS removal [

31,

32]. [

19] identified different fungi strains and found a higher degradability in

Pleurotus ostreatus,

Lentinula edodes, and

Pleurotus eryngii. From the articles considered for this systematic review, AMF such as

Funneliformis mosseae,

Rhizophagus irregularis, or

Claroideoglomus etunicatum, were successfully inoculated in anaerobic digestate [

12,

30,

34].

Table 9 lists the articles selected through the systematic research, describing the fungi strain, plant tested, as well as effects in plant growth and pollutant/nutrient behavior.

Specific fungal strains result in different growth rates. [

19] reported a higher degradative ability as well as growth rate in anaerobic digestate for

Pleurotus ostreatus,

Lentinula edodes, as well as

Pleurotus eryngii. This difference depends on both, fungi strain and substrate characteristics, such as C/N:ratio, pH, and contaminants content. This author reported that the concentration of trace elements in anaerobic digestate affect directly the concentration of trace elements in the fungi. Although anaerobic digestate represents an adequate nutrient source, nutrient availability depends greatly on the fungi species.

Agaricus bisporus provide significant amounts of K and Na, while

Agaricus subrufescens is an important source of Cu and Zn, indicating the specific fungi capacity to bioaccumulate such elements. [

19] suggested that Si content could result in augmentation of microbial interaction, whereas pathogens plant colonization could be hindered.

3.3. Effect on Pollutants/Nutrients Analyzed

In the selected articles, not only heavy metals were considered as pollution source. The idea was to gather a wider approach of the mechanisms involved between fungi and anaerobic digestate, for plant growth and contaminants removal.

Table 9 shows the results of the articles describing the fungi strain, plant tested, as well as effects in plant growth and pollutant/nutrient behavior. [

32] tested the uptake of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in fungi cultivation, resulting in a lower accumulation PFAS in fungi through digestate. The capacity to remove two antibiotics and one anticonvulsant was tested by [

31], showing that antibiotics were not accumulated in fungi. Different chemical elements were analyzed for their biodegradation, i.e. Ca, Co, Cr, Fe, K, Mg, Mn, Mo, Na, Ni, Se, Si, and Zn.

3.3.1. Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and Antibiotics

The material remaining after fungi harvesting has been used for degrading polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and other persistent organic pollutants, as well as for heavy metal biosorption, or even as biological control for nematodes pests in soils [

27,

36]. [

32] tested the uptake of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in fungi cultivation. PFAS are used in many industrial and consumer products and are persistent in the environment, being accumulated in the human body. From the research,

A. bisporus revealed a higher PFAS concentration, in comparison to

A. subrufescens. Ultra-short chain PFAS showed much greater accumulation compared to long chain PFAS. Also, temperature has a direct influence in the degradation rate of organic matter, whereas digestate composition may become different, influencing pollutant sorption and bioavailability. Meanwhile, short-chained acids are less affected by pH changes, than long-chained.

Ref. [

31] compared antibiotics removal in two different fungi,

A. subrufescens and

A. bisporus. In general, ciprofloxacin removal rate was by 83–90% and carbamazepine by 57–97%, even though the antibiotic content was low.

A. subrufescens showed a higher efficiency in contaminant removal. This fungus is considered tropical and was cultivated at higher temperatures. Authors did not report further conditions about the exact growing temperature, but suggested that this fact could had influenced the higher removal rate. Contaminant concentrations in

A. subrufescens was lower, even when the initial concentration was the same. From the fungi cultivation was observed that organic acids resulted in a higher organic matter degradation with a pH decrease. Control test, with no fungi cultivation, showed a lower organic matter degradation with an increased pH.

3.3.2. Pollutant/Nutrients Analyzed

Table 9 lists the pollutants/nutrient analyzed in the selected research articles. [

19] reported Zn as antagonist of some metals such as Cd, Pb, and Ni. Zn presence in fungi hinder high concentrations of other toxic metals. Cd was mycelium age specific, the older the mycelium, the lower Cd accumulation.

In a study from [

12] anaerobic digestate increased the total nitrogen, nitrate nitrogen ammonia nitrogen, as well as available phosphorus content in

Pennisetum soil, reducing soil organic matter.

The behavior of phosphate and sulphate content was compared using inorganic fertilizer and digestate as organic fertilizer [

35]. It was reported that the content of both micronutrients was higher in the anaerobic digestate. Nitrate content was nevertheless lower in digestate, in comparison to inorganic fertilizer, whereas uptake of P, S, N, K, Ca, Zn, B, and Mg was higher. The organic fertilizer resulted in higher pH and available P concentration, but a lower total grass dry matter. Bacteria utilizing sulfonate- and phosphonate were up to five times more abundant in the organic fertilizer. Phytate-utilizing and calcium phosphate-utilizing bacteria were not significantly different between treatments.

Ref. [30] reported a significant decreased of Pb, when inoculating coriander with AMF using anaerobic digestate as soil amendment, resulting in a higher Pb extractability. Trace elements concentration did not change for soil vegetation. A higher bioavailability of Cd, Pb, and Zn was shown when no amendment was applied in the soil. When the vegetated soil was inoculated with AMF, bioavailability of this elements decreased. By non-vegetated soil was inoculated with AMF, Cd, Zn, and Cu bioavailability increased. Cd was the predominantly accumulated element in the coriander shoots.

Ref. [30] demonstrated a decrease in Cd and Zn extractability, also known as bioavailability, as well as in the Pb and Cd accumulation in coriander shoots. It was pointed out, that aromatic plants such as coriander, release metabolites in the rhizosphere to manage nutrient bioavailability and metal stress. The mechanisms involved are related to the organic acids content, which are released as exudates influencing TE availability forming complexes with metal ions or modifying soil characteristics. Several studies have shown that organic amendments increase the immobilization of metals and metalloids. This immobilization results from different processes, i.e. adsorption onto mineral surfaces, formation of stable compounds and organic ligands, surface precipitation, or even ion exchange. These processes were suggested but not deeply researched in previous studies. [

37] suggested that applying composted anaerobic digestate could minimize TE mobility and thus toxicity, resulting from the amount of dissolved organic matter. The study from [

30] showed an increased total and organic C, P, and Mg contents when applying composted anaerobic digestate, improving soil TE immobilization and plants nutrition, resulting in coriander shoot growth. However, same author reported no significant effect in shoot growth, when inoculating with AMF. Mechanisms related to TE immobilization by AMF inoculation are related to glomalin-related soil proteins production in mycorrhizosphere, TE gathered in fungal structures, such as vacuoles or fungal vesicles in mycorrhizal roots, as well as TE adsorption by extraradical hyphae [

38]. Due to the high P and N content in anaerobic digestate, an increased available P in soil has been reported [

28].

Further results suggest that anaerobic digestate has a greater impact on the diversity of fungal communities in rhizospheric soil, than in bacterial communities. According to [

28], Nitrogen content was not significantly increased after anaerobic digestion application, but nitrate nitrogen was.

3.4. Effect on Plant Growth and Organic Matter Removal

Anaerobic digestate could be used as organic amendment for soil inoculation through mycorrhizal fungus, hence soil quality and health improvement can take place.

Table 9 summarizes the plant growth obtained from the articles selected for this systematic review. [

30] reported that using anaerobic sludge in soil inoculated with AMF

Funneliformis mosseae resulted in a better growth of coriander as well as Cd and Zn immobilization in soil and thus lower Cd plant uptake.

In a further study from [

30] it was reported that

F. mosseae (AMF) inoculation neither promoted plant growth, nor root colonization. Anaerobic digestate could improve physical characteristics in soils, such as air permeability, water retention, stability, aggregates, and resistance to soil erosion, releasing nutrients slowly for a long-term plant growth [

12].

Nutrient availability is a key factor for an efficient plant and microbial community growth. The use of anaerobic digestate could guarantee the application of essential micronutrients such as N, P, S, C/N ratio, or even heavy metals i.e. Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, P, or Zn. [

30] reported that the application of anaerobic digestate for coriander cultivation under AMF inoculation play a crucial role for restoring soil functionality. Soil processes, such as formation and decomposition of organic matter, as well as cycles of respiration and nutrition, have been impacted by microbial communities. Also soil composition and structure can be regulated by AMF.

Fungi shows advantages over plant production, due to the fact that they can be grown in processed substrates, i.e. composted, pasteurized, or even sterilized media. In the process, some toxic compounds in the substrate could be reduced. [

19] reported that fungi mycelium grows within the substrate decomposing material, whereas colonization takes place through secreted enzymes breaking down complex organic matter into simpler components. [

39] demonstrated that fungi root exudates dissolve metals from substrate in mycelium zone, influencing mineral adsorption.

It has been reported by [

33] that saprophytic whiterot fungi produce extracellular enzymes that degrade cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin biopolymers, what could enhance the organic matter removal, or even soil remediation grade.

3.5. Effect on Microbial Community

Several authors ([

28,

30,

35]) have demonstrated that the application of soil amendment in form on anaerobic digestate result in an enrichment of microbial communities in soil. [

28] documented a significant increase of AMF

Glomus and

Paraglomus, when using anaerobic digestate. When applying anaerobic digestate in soil, more organic matter needs to be decomposed, thus a wider variety of microorganisms is needed. It has been also demonstrated that different concentrations of anaerobic digestate promote the growth of different fungi.

Glomus showed a higher abundance when applying increased concentrations or anaerobic digestate, while

Paraglomus growth was higher with smaller anaerobic digestate concentration.

Ref. [

35] reported significantly higher bacteria feeders, nematode abundance and root colonization in mycorrhiza arbuscules, hyphae and vesicles, using anaerobic digestate as fertilizer compared to the use of inorganic fertilizer. Nematode abundance and bacteria feeders showed a higher prevalence of bacteria feeding nematodes from the

Cephalobidae and

Rhabditidae families. [

30] reported a significant increase in the total microbial biomass using anaerobic digestate as soil amendment. Soil metabolic potential as well as functional richness were low in non-amended soils, nevertheless this value increased when growing coriander in these soils. Dehydrogenase activity was though not altered in non-amended soils.

Phosphomonoesterase activity was not affected whether by amendment nor by coriander.

The application of organic amendments has demonstrated the enrichment of microbial communities in soils, whereas plant associated microorganisms reduce TE uptake by plants. This could be a reason why [

30] reported a significant decrease in extractable Cd and Zn, while Pb and Cd were accumulated in coriander shoots. Furthermore, rhizosphere microorganisms have the capacity to regulate plant uptake and TE bioavailability through mechanisms of oxidation, reduction, complexation, immobilization, adsorption, or dissolution [

40].

After AMF addition, [

12] reported an improvement in richness and diversity of fungi in hybrid

Pennisetum soil, however AMF effect was reduced after application of anaerobic digestate. It was suggested, that the different application concentrations could affect the separation of bacterial and fungal diversity. The addition of AMF increased the abundance of

Acidea, reducing

Plectosphaerella abundance, when no digestate was applied. When digestate was used, no difference of both species was found, whether with or without AMF.

Ref. [

28] reported that the application of high concentrated anaerobic digestate resulted in a significant enrichment of species richness and Shannon diversity of AMF in rhizosphere of poplar plantations. The lower concentration of anaerobic digestate tested showed a decreased in AMF diversity. The abundance of the dominant genera

Glomus and

Paraglomus increased significantly. Also, soil fertility and the presence of more soil microorganisms increased with the application of digestate, due to the fact that organic fertilizers provide a higher amount of organic matter to be decomposed.

4. Conclusions

The findings on the use of anaerobic digestates as soil conditioner inoculated with fungi underline their long-term ecological potential for the remediation of polluted soils. This strategy is proving to be a promising and cost-effective tool for improving soil functionality and stability, rather than directly promoting plant growth.

The origin of the biomass used for anaerobic digestion plays a crucial role in determining the quality of the digestate. If the digestate is derived exclusively from cattle manure, its application to fungi inoculated soils will result in increased organic matter decomposition and mycelial colonization, as well as lower salinity and electrical conductivity. In contrast, the addition of mixed organic waste can increase the concentrations of TE and HM, which can impair the development of the microbial community and limit remediation efficiencies.

While the fungal strain selected for inoculation is a key factor, it must be evaluated in conjunction with other variables such as digestate composition, application concentration, pH, temperature, and contaminant type. Although authors specify that pH and temperature in particular affects the degradation of organic matter and removal of contaminants, no further analysis were reported regarding both parameters. Temperate conditions resulted to be more efficient than colder temperatures.

The combined application of fungi and digestate contributed to the reduction of Pb content and its increased bioavailability, while improving soil pH and availability of phosphorus, phosphates, and sulfates as soil nutrients. Aromatic plants such as coriander promote metal complexation and immobilization through their root exudates and the release of organic acids, especially when applied together with anaerobic digestate.

Interestingly, to improve the bioavailability of certain heavy metals, i.e. Cd, Zn, Cu, the absence of vegetation during certain phases of remediation may be necessary — an aspect that warrants further investigation.

Overall, the use of anaerobic digestate, especially from cattle manure, promotes microbial diversity and improves the processes associated with soil remediation and stabilization. However, the benefits to plant growth are less consistent and appear to be secondary to the effects on soil health. Future research should focus on pollutant-specific remediation strategies using digestate from manure, ideally in combination with tropical fungal strains to maximize effectiveness under different environmental conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.LV-S. and J.A.R-M.; methodology, Y.M-B. and A.A-R.; validation, M.C.G-L.; formal analysis, J.C-G. and H.P.; investigation, M.LV-S. and Y.M-B.; resources, M.A.R-L.; data curation, J.C-G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.LV-S. and J.A.R-M.; writing—review and editing, M.LV-S., Y.M-B., M.C.G-L. and J.A.R-M.; visualization, R.CH-S. and C.E.Z-G.; supervision, J.A.R-M.; project administration, A.A-R. and J.A.R-M.; funding acquisition, M.A.R-L. and J.C-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The funding for this research was specifically provided by the Secretaría de Investigación, Innovación y Posgrado of the Universidad Autónoma de Queretaro, covering a partial contribution exclusively for the publication of the scientific article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the Dirección de Investigación, Innovación y Posgrado of the Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro for partially funding the publication of this article. We also extend our thanks to Dr. Alejandro Zentella Dehesa from Laboratory 2, Unit of Biochemistry at the Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubirán” (INCMNSZ) for generously providing the research facilities and the breast cancer cell lines used in this study, and to Dr. José Luis Ventura for his invaluable support in conducting the in vitro experiments at INCMNSZ.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AD |

Anaerobic digestion |

| Al |

Aluminum |

| AM |

Arbuscular mycorrhiza |

| As |

Arsenic |

| B |

Boron |

| Ba |

Barium |

| C |

Carbon |

| Ca |

Calcium |

| Cd |

Cadmium |

| Ce |

Cerium |

| CH4 |

Methane |

| CHP |

Combined heat power generator |

| C/N |

Carbon/nitrogen |

| C/N/P |

Carbon/nitrogen/phosphorous |

| Co |

Cobalt |

| CO2 |

Carbon dioxide |

| Cr |

Chromium |

| Cu |

Cupper |

| EcM |

Ectomycorrhiza |

| Fe |

Iron |

| Ge |

Germanium |

| H2 |

Hydrogen |

| Hg |

Mercury |

| H2O |

Water |

| HM |

Heavy metal |

| HRT |

Hydraulic retention time |

| H2S |

Hydrogen sulfide |

| Ir |

Iridium |

| K |

Potassium |

| Li |

Lithium |

| Mn |

Manganese |

| Mo |

Molybdenum |

| Mg |

Magnesium |

| n |

Number |

| N |

Nitrogen |

| Na |

Sodium |

| Ni |

Nickel |

| Nd |

Neodymium |

| N/P |

Nitrogen/phosphorous |

| O2 |

Oxygen |

| ODM |

Organic dry matter |

| Os |

Osmium |

| P |

Phosphorous |

| Pb |

Lead |

| PAHs |

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons |

| PFAS |

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances |

| PGPR |

Promoting rhizobacteria |

| Pr |

Praseodymium |

| Pt |

Platinum |

| Rb |

Rubidium |

| S |

Sulphur |

| Sb |

Antimony |

| Se |

Selenium |

| Sn |

Tin |

| Sr |

Strontium |

| Si |

Silicon |

| Ta |

Tantalium |

| Te |

Tellurium |

| TE |

Trace elements |

| Ti |

Titanium |

| Tl |

Thallium |

| TN |

Total nitrogen |

| U |

Uranium |

| V |

Vanadium |

| W |

Tungsten |

| Zr |

Zirconium |

| Zn |

Zinc |

References

- Uddin, M. M.; Wright, M. M. Anaerobic digestion fundamentals, challenges, and technological advances. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2023,8(9):2819-2837. [CrossRef]

- Kabeyi, M.J.B.; Olanrewaju, O.A. Biogas Production and Applications in the Sustainable Energy Transition. J. Energy. 2022, 8750221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FNR. Leitfaden Biogas, von der Gewinnung zur Nutzung, 7th ed.; Fachagentur Nachwachsende Rohstoffe e.V.: Gülzow-Prüzen, Germany, 2016; pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zupancic, M.; Možic, V.; Može, M.; Cimerman, F.; Golobicˇ, I. Current Status and Review of Waste-to-Biogas Conversion for Selected European Countries and Worldwide. Sustain. 2022,14(1823). [CrossRef]

- KGaA KSS & C. Biogas: Grundlagen der Gärbiologie; KWS Mais GmbH: Einbeck, Germany, 2009; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Kougias, P. G.; Angelidaki, I. Biogas and its opportunities—A review. Front. Environ. Sci Eng. 2018,12(3):14. [CrossRef]

- Baştabak, B.; Koçar, G. A review of the biogas digestate in agricultural framework. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2020,22(5):1318-1327. [CrossRef]

- Mertins, A.; Wawer, T. How to use biogas?: A systematic review of biogas utilization pathways and business models. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2022,9(1):59. [CrossRef]

- Behera, K. S.; Park, J. M.; Kim, K. H.; Park, H. S. Methane production from food waste leachate in laboratory-scale simulated landfill. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1502–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.T.; Williams, J.W. Modern analogs in quaternary paleoecology: Here Today, Gone Yesterday, Gone Tomorrow? Annu. Rev. Earth Planet Sci 2004, 32, 495–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Arshad, M. Anjum M, Mahmood T, Dawson L. The anaerobic digestion of solid organic waste. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Ran, Q.; Zhou, J.; Bi, M.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S.; Fan, Y.; Nie, G.; He, W. Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Biogas Slurry Application on Plant Growth, Soil Composition, and Microbial Communities of Hybrid Pennisetum. Sustain. 2024;16(19). [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, Z.; Ullah, H.; Datta, A.; Anwar, M.; Ali, A. Yield and Profitability of Tomato as Influenced by Integrated Application of Synthetic Fertilizer and Biogas Slurry. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 2018, 24, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronga, D.; Setti, L.; Salvarani, C.; De Leo, R.; Bedin, E.; Pulvirenti, A.; Milc, J.; Pechionni, N.; Francia, E. Effects of solid and liquid digestate for hydroponic baby leaf lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) cultivation. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 244, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehmann, A.; Bach, I.M.; Bilbao, J.; Lewandowski, I.; Müller, T. Phosphates recycled from semi-liquid manure and digestate are suitable alternative fertilizers for ornamentals. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 243, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Qi, G. Andriamanohiarisoamanana, F. J.; Yamashiro, T.; Iwasaki, M.; Nishida, T.; Tangtaweewipat, S.; Umetsu, K. Potential of anaerobic digestate of dairy manure in suppressing soil-borne plant disease. Anim. Sci. J. 2018;89(10):1512-1518. [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, D.; Lee, D. J.; Chang, J. S. Integration of anaerobic digestion and microalgal cultivation for digestate bioremediation and biogas upgrading. Bioresour. Technol. 2019,290(121804). [CrossRef]

- Goberna, M., Podmirseg, S. M.; Waldhuber, S.; Knapp, B. A.; García, C.; Insam, H. Pathogenic bacteria and mineral N in soils following the land spreading of biogas digestates and fresh manure. Appl Soil Ecol. 2011,49:18-25. [CrossRef]

- Jasinska, A.; Stoknes, K.; Niedzielski, P.; Budka, A.; Mleczek, M. Mushroom production on digestate: Mineral composition of cultivation compost, mushrooms, spent mushroom compost and spent casing. J Agric Food Res. 2024,18(101518). [CrossRef]

- Akpasi, S. O.; Anekwe, I. M. S.; Tetteh, E. K.; Amune, U. O.; Shoyiga, H. O.; Mahalangu, T. P.; Kiambi, S. L. Mycoremediation as a Potentially Promising Technology: Current Status and Prospects—A Review. Appl Sci. 2023,13(4978). [CrossRef]

- Sepehri, M.; Khodaverdiloo, H.; Zarei, M. Fungi and Their Role in Phytoremediation of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soils. In: Fungi as Bioremediators, Goltapeh, E. M., Danesh, Y. R., Varma, A., Eds. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 2013: pp. 313-345.

- Goltapeh, E. M.; Danesh, Y. R.; Prasad, R.; Varma, A. Mycorrhizal Fungi: What We Know and What Should We Know? In: Varma A, ed. Mycorrhiza: State of the Art, Genetics and Molecular Biology, Eco-Function, Biotechnology, Eco-Physiology, Structure and Systematics. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2008,3-27. [CrossRef]

- Trocio, D. Y. C.; Paguntalan, D. P. Review on the Use of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Bioremediation of Heavy Metal Contaminated Soils in the Philippines. Philipp. J. Sci. 2023;152(3). ISSN: 0031-7683.

- Colpaert, J. V. Chapter 11 Heavy metal pollution and genetic adaptations in ectomycorrhizal fungi. In Stress in Yeast and Filamentous Fungi, Avery S. V., Stratford M., West P. V. Eds. British Mycological Society Symposia Series; 2008; Volume 27, pp. 157-173.

- Leyval, C.; Turnau, K.; Haselwandter, K. Effect of heavy metal pollution on mycorrhizal colonization and function: physiological, ecological and applied aspects. Mycorrhiza 1997, 7, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrol, N.; Tamayo, E.; Vargas, P. The heavy metal paradox in arbuscular mycorrhizas: from mechanisms to biotechnological applications. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 6253–6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Pankaj, U.; Chand, S.; Verma, R. K. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi-Assisted Phytoextraction of Toxic Metals by Zea mays L. From Tannery Sludge. Soil Sediment. Contam. Int. J. 2019, 28, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. Y.; Wang, B. T.; Jin, L.; Ruan, H. H.; Lee, H. G.; Jin, F. J. Impacts of Biogas Slurry Fertilization on Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungal Communities in the Rhizospheric Soil of Poplar Plantations. J. Fungi. 2022,8(12). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Naeth, M. A. Soil amendment with a humic substance and arbuscular mycorrhizal Fungi enhance coal mine reclamation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022,823(153696). [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, J.; Duclercq, J.; Facon, N.; Dewaele, D.; Laruelle, F.; Tisserant, B.; Saharaoui, A. L.-H. Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) in Combination with Organic Amendments and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Inoculation: An Efficient Option for the Phytomanagement of Trace Elements-Polluted Soils. Microorganisms. 2022,10(11). [CrossRef]

- Nesse, A. S.; Jasinska, A.; Stoknes, K.; Aanrud, S. G.; Risinggard, K. O.; Kallenborn, R.; Sogn, T. A.; Ali, A. M. Low uptake of pharmaceuticals in edible mushrooms grown in polluted biogas digestate. Chemosphere 2024, 351, 141169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesse, A. S.; Jasinska, A.; Ali, A. M.; Sandblom, O.; Sogn, T. A.; Benskin, J. P. Uptake of Ultrashort Chain, Emerging, and Legacy Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Edible Mushrooms (Agaricus spp.) Grown in a Polluted Substrate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023,71(11):4458-4465. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.J.; Milligan, E.; Carver, J.; Roy, E. D. Integrating anaerobic co-digestion of dairy manure and food waste with cultivation of edible mushrooms for nutrient recovery. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 285, 121312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulo, A. M.; Caetano, N. S.; Marques, A. P. G. C. The Potential of Bioaugmentation-Assisted Phytoremediation Derived Maize Biomass for the Production of Biomethane via Anaerobic Digestion. Plants. 2023,12(20). [CrossRef]

- Ikoyi, I.; Egeter, B.; Chaves, C.; Ahmed, M.; Fowler, A.; Schmalenberger, A. Responses of soil microbiota and nematodes to application of organic and inorganic fertilizers in grassland columns. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2020, 56, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenkolb, T.; Vilcinskas, A. Metabolites from nematophagous fungi and nematicidal natural products from fungi as an alternative for biological control. Part I: metabolites from nematophagous ascomycetes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 3799–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palansooriya, K. N.; Shaheen, S. M.; Chen, S. S.; Tsang, D. C. W.; Hashimoto, Y.; Hou, S.; Bolan, N. S.; Rinklebe, J.; Ok, Y. S. Soil amendments for immobilization of potentially toxic elements in contaminated soils: A critical review. Environ Int. 2020, 134, 105046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeeshma, E.; Puthur, J. T. Direct and indirect influence of arbuscular mycorrhizae on enhancing metal tolerance of plants. Arch Microbiol. 2020,202(1):1-16. [CrossRef]

- Senila, M.; Resz, M. A.; Senila, L.; Torok, I. Application of Diffusive Gradients in Thin-films (DGT) for assessing the heavy metals mobility in soil and prediction of their transfer to Russula virescens. Sci Total Environ. 2024,909(168591). [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Shahid, M.; Niazi, N. K.; Murtaza, B.; Bibi, I.; Dumat, C. A comparison of technologies for remediation of heavy metal contaminated soils. J Geochem Explor. 2017, 182, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).