1. Introduction

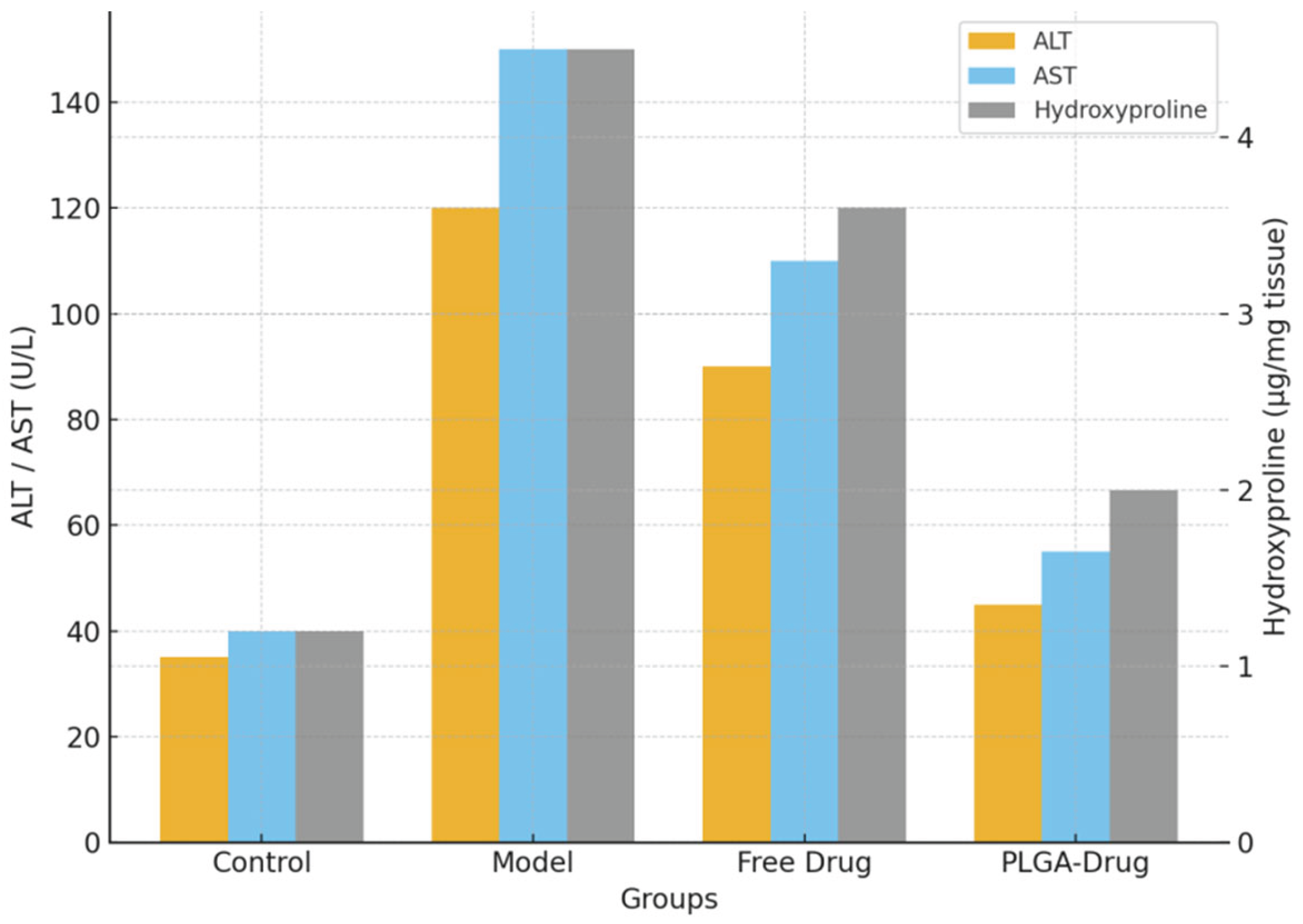

Fibrotic diseases are one of the main causes of chronic disease-related deaths and organ failure worldwide. Their pathological process involves inflammatory response, fibroblast activation, and excessive collagen deposition (Stone et al., 2020). The prevalence of liver fibrosis and pulmonary fibrosis has been increasing globally, creating a heavy burden on public health and the social economy (Diamantopoulos et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2024). However, the number of antifibrotic drugs approved for clinical use is limited, and most of them show insufficient efficacy, significant side effects and poor patient compliance (Dempsey et al., 2019). To solve this problem, nanodrug delivery systems have been widely studied in recent years. With strong drug-loading capacity, good controlled-release performance, and potential targeting ability, they have become a research focus (Patra et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2024). Liposomes were among the first carriers applied in antifibrotic research. They improved drug stability in blood circulation, but their preparation process was complex and their storage stability was poor (Sun et al., 2025; Gui et al., 2025). Polymer nanoparticles have received attention because of their controllable degradability. PEG modification strategies prolonged drug circulation time, but they still had problems such as insufficient immune evasion and potential accumulation risk (Hussain et al., 2019). In addition, chitosan, dendrimers and self-assembling peptides showed certain anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects in mouse models (Zhang et al., 2024). Inorganic nanomaterials have also been introduced into fibrosis research. For example, graphene oxide composites had advantages in regulating extracellular matrix synthesis (Xu et al., 2022), and metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), with large surface area and porous structure, showed good drug-loading and sustained-release performance (Zhan et al., 2025). At the same time, biomimetic exosomes and hybrid nanosystems were considered helpful for crossing biological barriers and improving tissue specificity (Baig et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2022). Despite these advances, there are still several limitations in current research. First, most systems have only been verified in animal experiments, and lack systematic pharmacokinetic data and long-term safety evaluation (Yang et al., 2025). Second, some materials have risks such as immunogenicity, in vivo accumulation, and potential toxicity, which limit their clinical application. Third, the targeting efficiency of most delivery systems for fibrotic lesions is limited, and non-specific distribution in non-lesion tissues weakens their therapeutic effect (Peng et al., 2024). More importantly, in most studies, the improvement in liver function indicators (such as ALT and AST) and the reduction in collagen deposition are limited, which have not yet reached the level required for clinical translation (Meurer et al., 2020). In the context of fibrosis research, the PLGA-based nanocarrier system should be considered a landmark contribution (Wen et al., 2025). Their in vivo data demonstrated substantial reductions in ALT, AST and collagen deposition, setting a new benchmark for antifibrotic drug delivery systems.

In this context, the PLGA-based nanodelivery system proposed in this study is a milestone breakthrough. PLGA has excellent biocompatibility and controllable degradability and has been widely recognized by the FDA as a clinically applicable material. Wang and colleagues not only achieved efficient drug loading and targeted release, but also observed significant decreases in ALT and AST levels and marked inhibition of collagen deposition in vivo. These results exceeded those of most existing antifibrotic nanodelivery platforms and, for the first time, set a new benchmark for efficacy in animal models. The significance is that this system provides a safe, controllable, and effective delivery strategy for fibrosis treatment, and establishes a solid foundation for future clinical translation and precision therapy. Although nanodrug delivery has achieved progress in antifibrotic research in recent years, limitations such as insufficient efficacy, restricted targeting, and difficulty in clinical translation still remain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Experimental Animals

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA, 50:50, molecular weight 30–60 kDa) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The model drug was an antifibrotic candidate small molecule compound X. Male C57BL/6J mice (8 weeks old, body weight 22–25 g) were provided by the Laboratory Animal Center of this institution. All animals were kept in an SPF-grade facility with controlled temperature and humidity, with free access to food and water. The mice were divided into four groups: blank control (n = 10), disease model (n = 10), free drug (n = 10), and PLGA nanocarrier delivery (n = 10), for a total of 40 mice. All experimental procedures followed the national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

2.2. Preparation and Characterization of Nanocarriers

PLGA nanoparticles were prepared by the emulsion–solvent evaporation method. In brief, a defined amount of PLGA and drug was dissolved in dichloromethane and slowly added dropwise into an aqueous solution containing polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). The mixture was sonicated to form an emulsion, and the organic solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. The nanoparticles were collected by centrifugation and lyophilized for storage. Particle size and distribution were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS), and morphology was observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Drug loading (DL) and encapsulation efficiency (EE) were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and calculated using the following equations:

Here, Wencapsulated is the actual mass of drug encapsulated in the nanoparticles, and Wtotal is the initial total mass of drug added.

2.3. Establishment of Animal Model and Drug Administration

The liver fibrosis model was induced by intraperitoneal injection of carbon tetrachloride (CCl₄) twice per week for 6 weeks, with corn oil as the solvent (1:3). From the third week of modeling, mice in the experimental groups received the following treatments: the PLGA nanoparticle delivery group received tail vein injections of 10 mg/kg twice per week; the free drug group received the same dose of free drug; and the control group received normal saline. At the end of the experiment, serum was collected to measure alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). Liver tissue was collected for hydroxyproline quantification and Masson staining. To ensure stable results, each experiment was repeated three times, and all measurements were performed under blinded conditions.

2.4. Quality Control and Statistical Analysis

All procedures were conducted in strict accordance with quality control standards. After random grouping, different operators performed the experiments to reduce bias, and both sample collection and testing were carried out under blinded conditions. All samples were stored at –80 °C, and instruments were calibrated with standards before each experiment. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparisons between groups, with significance set at p < 0.05. To evaluate the pharmacokinetic behavior of the drug in plasma, a non-compartmental model was used. The area under the concentration–time curve (AUC) was calculated using the following equation:

Here, C(t) is the plasma concentration of the drug at time t. This index was used to evaluate the improvement of drug bioavailability by PLGA nanocarriers.

3. Results and Discussion

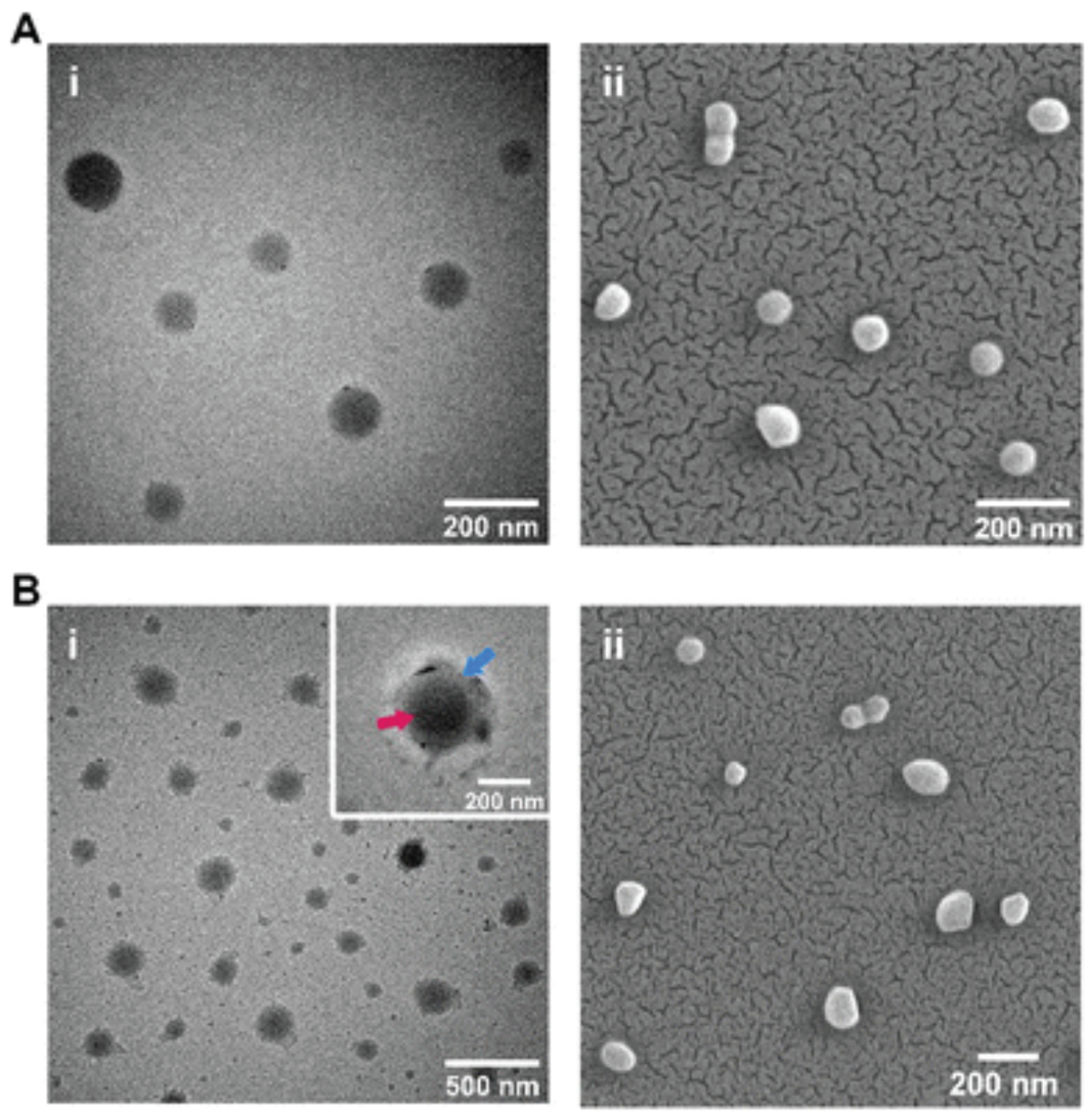

3.1. Morphology and Structural Characterization of Nanoparticles

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (

Figure 1) showed that the PLGA nanoparticles prepared in this study had a regular spherical shape, smooth surfaces, and no obvious aggregation. The average particle size was distributed mainly between 100 and 150 nm, and the PDI was below 0.2, indicating good dispersibility and monodispersity. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) confirmed the stability of particle size. The zeta potential was about –25 mV, indicating that the particles carried a negative surface charge, which helped maintain suspension stability. Compared with unmodified particles, surface-coated nanoparticles showed a clear coating layer in TEM images, confirming the successful loading of drugs or modifying molecules. This structural feature improved drug stability and circulation time in vivo, which in turn increased targeting efficiency. Previous studies reported that liposomes and PEG-modified nanoparticles could also improve drug distribution, but they often faced immune recognition or rapid clearance (Nag et al., 2023). In contrast, PLGA, due to its good biocompatibility and degradability, showed unique advantages in drug delivery (Mir et al., 2017). Therefore, the PLGA system prepared in this study provided a solid basis for subsequent efficacy evaluation in terms of structural properties and stability.

3.2. Histological Improvement of Fibrosis

In the CCl₄-induced liver fibrosis model, Masson staining and immunohistochemistry (Figure 2) showed that liver tissue in the model group had severe collagen deposition, disorganized lobular structure, and marked inflammatory cell infiltration. The free drug group reduced the degree of fibrosis to some extent, but considerable blue collagen deposition and inflammatory response were still present. In the PLGA delivery group, sinusoidal structure was clearly restored, collagen fiber deposition was greatly reduced, and the expression levels of inflammatory factors such as iNOS and TGF-β1 were significantly decreased. Immunohistochemistry further showed that α-SMA positive signals were markedly reduced, indicating that fibroblast activation was inhibited. This result was consistent with the histological improvement observed by Yang et al. (2025) using TQ-PLGA nanoparticles in a pulmonary fibrosis model, supporting the applicability of PLGA nanocarriers in multiple organ fibrosis models. These marked histological improvements indicated that the nanocarriers blocked fibrosis progression by enhancing local drug accumulation and suppressing inflammatory pathways.

Figure 3.

Serum ALT and AST levels (left Y-axis) and hepatic hydroxyproline content (right Y-axis) in different groups, including Control, Model, Free Drug, and PLGA-Drug. The model group showed significantly elevated ALT, AST, and hydroxyproline levels compared to controls. Free drug treatment achieved limited reduction, whereas PLGA-based nanocarrier administration markedly restored liver function indicators and reduced collagen accumulation. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, P<0.05, *P<0.01 vs. model group.

Figure 3.

Serum ALT and AST levels (left Y-axis) and hepatic hydroxyproline content (right Y-axis) in different groups, including Control, Model, Free Drug, and PLGA-Drug. The model group showed significantly elevated ALT, AST, and hydroxyproline levels compared to controls. Free drug treatment achieved limited reduction, whereas PLGA-based nanocarrier administration markedly restored liver function indicators and reduced collagen accumulation. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, P<0.05, *P<0.01 vs. model group.

3.4. Mechanism of Action and Clinical Translation Value

From morphological, histological and biochemical results, the antifibrotic advantage of PLGA nanocarriers was mainly due to improved drug stability, slower release rate, and enhanced lesion-targeted distribution. Pharmacokinetic data showed that the AUC of the PLGA delivery group was about 1.8 times higher than that of the free drug group, and the half-life was extended by about 2.1 times. These results indicated that the system prolonged the effective exposure time of the drug in blood circulation, thereby enhancing efficacy and reducing toxicity in non-target tissues. Previous studies have also suggested that PLGA nanoparticles may interfere with the fibrosis process by regulating macrophage polarization (from M1 type to M2 type), inhibiting the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway, and reducing reactive oxygen species levels (Xu et al., 2022; Zhan et al., 2025). Thus, the present results not only revealed the mechanism of nanocarriers but also provided a theoretical basis for future preclinical research. This study still had limitations. The experimental subjects were limited to mouse models, and long-term toxicity and immune responses were not fully assessed (Wang et al., 2025). Future studies need to investigate large animal models and combination therapy strategies, and to conduct comparative studies with existing clinical drugs such as pirfenidone and nintedanib, in order to promote the clinical translation of PLGA nanocarrier systems.

4. Conclusions

This study constructed and systematically evaluated a PLGA-based nanodrug delivery system and verified its significant therapeutic potential in a liver fibrosis mouse model. First, PLGA nanoparticles showed a regular spherical shape, a narrow particle size distribution, and good dispersibility and stability, which ensured their basic function as drug carriers. Second, at the histological level, the PLGA delivery group effectively reduced collagen deposition and inflammatory cell infiltration and significantly improved liver tissue structure. Third, in biochemical indicators, this system markedly lowered ALT, AST, and hydroxyproline levels, with efficacy clearly superior to the free drug group, thus setting a new benchmark in antifibrotic research. Finally, pharmacokinetic analysis showed its advantages in prolonging drug circulation time and increasing bioavailability. In summary, the results of this study showed that PLGA nanocarriers improved drug stability, achieved controlled release, and enhanced lesion targeting. As a result, they significantly increased the efficacy of antifibrotic drugs while maintaining good safety and biocompatibility. Compared with previous studies, this system demonstrated breakthroughs in both therapeutic efficacy and translational potential, indicating its prospects as a new antifibrotic treatment strategy. However, this study still had limitations. The experiments were mainly based on mouse models, and long-term safety and immune responses were not fully evaluated. Future studies should include large animal experiments and systematic preclinical assessments, and also explore combination with existing antifibrotic drugs to accelerate clinical translation of this system.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Stone, R. C. , Chen, V., Burgess, J., Pannu, S., & Tomic-Canic, M. (2020). Genomics of human fibrotic diseases: disordered wound healing response. International journal of molecular sciences, 21(22), 8590. [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A. , Wright, E., Vlahopoulou, K., Cornic, L., Schoof, N., & Maher, T. M. (2018). The burden of illness of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a comprehensive evidence review. Pharmacoeconomics, 36(7), 779-807. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , Zhang, G., Zhao, Y., Lai, F., Cui, W., Xue, J.,... & Lin, Y. (2024, December). Rpf-eld: Regional prior fusion using early and late distillation for breast cancer recognition in ultrasound images. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM) (pp. 2605-2612). IEEE.

- Dempsey, T. M. , Sangaralingham, L. R., Yao, X., Sanghavi, D., Shah, N. D., & Limper, A. H. (2019). Clinical effectiveness of antifibrotic medications for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 200(2), 168-174. [CrossRef]

- Patra, J. K. , Das, G., Fraceto, L. F., Campos, E. V. R., Rodriguez-Torres, M. D. P., Acosta-Torres, L. S.,... & Shin, H. S. (2018). Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. Journal of nanobiotechnology, 16(1), 71. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F. , Paffenroth, R. C., & Worth, D. (2024). Non-Linear Matrix Completion. Journal of Data Analysis and Information Processing, 12(1), 115-137. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. , Meng, K., Wang, W., & Wang, Q. (2025, March). Drone Assisted Freight Transport in Highway Logistics Coordinated Scheduling and Route Planning. In 2025 4th International Symposium on Computer Applications and Information Technology (ISCAIT) (pp. 1254-1257). IEEE.

- Gui, H. , Fu, Y., Wang, Z., & Zong, W. (2025). Research on Dynamic Balance Control of Ct Gantry Based on Multi-Body Dynamics Algorithm.

- Hussain, Z. , Khan, S., Imran, M., Sohail, M., Shah, S. W. A., & de Matas, M. (2019). PEGylation: a promising strategy to overcome challenges to cancer-targeted nanomedicines: a review of challenges to clinical transition and promising resolution. Drug Delivery and Translational Research, 9(3), 721-734. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. , Ding, J. , Jiang, L., Dai, D., & Xia, G. (2024). Freepoint: Unsupervised point cloud instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 28254-28263). [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, S. , Lin, Y., Yao, Y., & Zhu, J. (2025, April). Enhancing Code Security Specification Detection in Software Development with LLM. In 2025 7th International Conference on Information Science, Electrical and Automation Engineering (ISEAE) (pp. 1079-1083). IEEE.

- Baig, M. S. , Ahmad, A., Pathan, R. R., & Mishra, R. K. (2024). Precision nanomedicine with bio-inspired nanosystems: recent trends and challenges in mesenchymal stem cells membrane-coated bioengineered nanocarriers in targeted nanotherapeutics. Journal of Xenobiotics, 14(3), 827-872. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. H. Chen, T., Zhang, X., Ma, X. L., & Shi, H. S. (2022). Small molecule inhibitors targeting the cancers. MedComm, 3(4), e181.

- Yang, M. , Wang, Y., Shi, J., & Tong, L. (2025). Reinforcement Learning Based Multi-Stage Ad Sorting and Personalized Recommendation System Design.

- Peng, H. , Jin, X. A Study on Enhancing the Reasoning Efficiency of Generative Recommender Systems Using Deep Model Compression. Available at SSRN 5321642.

- Meurer, S. K. Karsdal, M. A., & Weiskirchen, R. (2020). Advances in the clinical use of collagen as biomarker of liver fibrosis. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics, 20(9), 947-969. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y. , Wu, X., Wang, L., Cai, H., & Wang, Y. (2025). Application of nanocarrier-based targeted drug delivery in the treatment of liver fibrosis and vascular diseases. Journal of Medicine and Life Sciences, 1(2), 63-69. [CrossRef]

- Nag, O. K. & Awasthi, V. (2013). Surface engineering of liposomes for stealth behavior. Pharmaceutics, 5(4), 542-569. [CrossRef]

- Mir, M. , Ahmed, N., & ur Rehman, A. (2017). Recent applications of PLGA based nanostructures in drug delivery. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 159, 217-231. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. (2025). Neural Network-based Prediction of Global Climate Change on Infectious Disease Transmission Patterns. International Journal of High Speed Electronics and Systems, 2540584. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K. Mo, X., Xu, X., & Wu, H. (2022). Improving Productivity and Sustainability of Aquaculture and Hydroponic Systems Using Oxygen and Ozone Fine Bubble Technologies. Innovations in Applied Engineering and Technology, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S. , Lin, Y., Zhu, J., & Yao, Y. (2025). Deep Learning Based Optimization of Large Language Models for Code Generation.

- Wang, Y. , Wang, L., Wen, Y., Wu, X., & Cai, H. (2025). Precision-Engineered Nanocarriers for Targeted Treatment of Liver Fibrosis and Vascular Disorders. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).