1. Introduction

Since the early days of the industrial revolution, people have been migrating to cities in search of better living conditions (Sousa-Silva, Cameron, & Paquette, 2021). Today, more than half of the world’s population resides in cities, and urbanization is expanding rapidly, exacerbating the climate crisis and loss of biodiversity (WWF, 2023). Urban areas frequently experience higher levels of air pollutants due to dense traffic and industrial activities z(Vos, Maiheu, Vankerkom, & Janssen, 2013). The rapid urbanization and population growth have intensified pressure on available green spaces, highlighting the urgent need for effective urban forestry management strategies (Wolch, Byrne, & Newell, 2014).

This urban expansion has accelerated the degradation of urban ecosystems, leading to increased consumption of natural resources and the gradual loss of natural habitats (Rey Mellado, Franchini Alonso, & Del Pozo Sánchez, 2021). Rapid urbanization also leads to the expansion and densification of cities, resulting in the proliferation of impervious surfaces and a significant reduction in vegetated areas. The loss of urban greenery compromises biodiversity contributes to rising pollution levels and intensifies the urban heat island (UHI) effect, where built environments absorb and retain heat, raising ambient temperatures. These changes have profound negative effects on both environmental health and the physical and mental well-being of urban residents (Duan et al., 2019; Edeigba, Ashinze, Umoh, Biu, & Daraojimba, 2024).

In Latin American cities, rapid urbanization has often occurred in the absence of adequate planning, leading to widespread deforestation, soil sealing, and the fragmentation of natural and urban green spaces. Cities such as São Paulo, Mexico City, Buenos Aires, Bogotá, and Santiago have undergone dramatic expansion in recent decades, typically through horizontal sprawl that consumes peri-urban vegetation and disrupts ecological continuity. This unregulated growth contributes not only to biodiversity loss but also to localized increases in air and surface temperature, further exacerbating the urban heat island effect. These spatial patterns—driven by socioeconomic pressures, transportation infrastructure, and uneven zoning regulations—pose significant challenges for sustainable land use and environmental equity across the region (Wu, Sumari, Dong, Xu, & Liu, 2021).

The heat island effect, where urban areas are warmer than their rural surroundings, presents a major sustainability challenge (Fini et al., 2022; Oke, 1982). Cities also face increased greenhouse gas emissions and resource consumption, contributing to climate change and extreme weather events (Jordán, Rehner, & Samaniego, 2012). Climate models predict a temperature increase of 1.1 °C to 6.4 °C in the 21st century (Change, 2007), intensifying health risks in urban heat islands (Cummins & Jackson, 2001; Laaidi et al., 2012).

In the context of climate change and urbanization, cities play a crucial role in mitigating these impacts through well-planned urban forestry (Satterthwaite, 2008). Urban trees provide numerous benefits, including air filtration, microclimate regulation, carbon dioxide absorption, noise reduction, and biodiversity enhancement (Alanís, Jiménez, Mora-Olivo, Canizales, & Rocha, 2014). They also offer social benefits, such as improved health, recreation, and educational opportunities (Donoso & Piedrahita, 2009). Urban tree planting is vital for creating sustainable and resilient cities, improving quality of life, and conserving the environment (Donovan, 2017). Urban trees, especially those in public spaces, contribute to climate change mitigation and enhance urban biodiversity and human well-being (Harlan & Ruddell, 2011; E. G. McPherson et al., 1997; Nowak, Hirabayashi, Doyle, McGovern, & Pasher, 2018; O’Sullivan, Holt, Warren, & Evans, 2017; Salmond et al., 2016; Tyrväinen, Pauleit, Seeland, & De Vries, 2005).

The replacement of vegetated surfaces with paved and impervious materials increases surface temperatures and contributes directly to the UHI effect (Akbari & Konopacki, 2005). This makes trees essential in dense urban environments, not only for their aesthetic value but also for their direct cooling effects during hot periods, significantly influencing the local microclimate (Leuzinger, Vogt, & Körner, 2010).

In terms of the green index, the World Health Organization recommends 9 m2 of green space per inhabitant, while the Habitat Agenda suggests 15 m2. However, in Ecuador, only 5% of cities meet these standards, with an average of just 4.69 m2 per person (Censos, 2023). This emphasizes the urgent need for effective urban forestry management strategies to improve urban green coverage in the country. In this context trees are essential in a dense urban environment not only because of their aesthetic value but also for their cooling effect during hot periods, which impacts directly on the local microclimate (Leuzinger et al., 2010). Planting trees in cities can mitigate urban heat island effects directly through shading and indirectly through evapotranspiration cooling, especially in the case of cities that are powered by fossil fuels (Messier et al., 2022). A focus on increasing tree density ensures a more strategic approach that addresses the unique needs of each urban sector and maximizes the positive environmental impacts of urban greening in cities like Riobamba.

The ecosystem services provided by urban trees, such as air quality improvement, carbon capture, and reduction of heat island effects, are well-documented (Boyd & Banzhaf, 2007; Dobbs, Nitschke, & Kendal, 2014; F. Escobedo & Chacalo, 2008; E. G. McPherson et al., 1997; Ziter, Pedersen, Kucharik, & Turner, 2019). Trees enhance air quality by absorbing pollutants and producing oxygen, reduce greenhouse gases through carbon storage, and mitigate heat island effects by providing shade and reducing surface temperatures (G. McPherson, Simpson, Peper, Maco, & Xiao, 2005). Additionally, they prevent soil erosion, reduce flood risks, and offer psychological and emotional benefits, improving mental health and quality of life (F. J. Escobedo, Kroeger, & Wagner, 2011).

Understanding public perceptions of the benefits and potential disservices of urban trees is crucial for the success of urban forestry initiatives. While many studies report positive perceptions—such as their contributions to aesthetics, shade, and well-being—others highlight concerns regarding allergies, maintenance requirements, and safety risks (Donovan, 2017; Nowak et al., 2018; Tyrväinen et al., 2005)

However, most of these studies are based in North America or Europe, revealing a significant research gap in the Latin American context, particularly in medium-sized cities like Riobamba.

This study aims to address that gap by investigating public perceptions in the city of Riobamba, Ecuador. Specifically, it seeks to: (1) assess how residents perceive urban tree cover and its ecosystem services; (2) identify which benefits are most valued; and (3) evaluate public willingness to support or participate in urban forestry initiatives. By doing so, the study provides insight into how citizen attitudes may inform local environmental policy and public participation in greening strategies. This research contributes to a broader understanding of urban sustainability efforts in Latin America and supports future planning aimed at enhancing the ecological and social livability of Riobamba.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

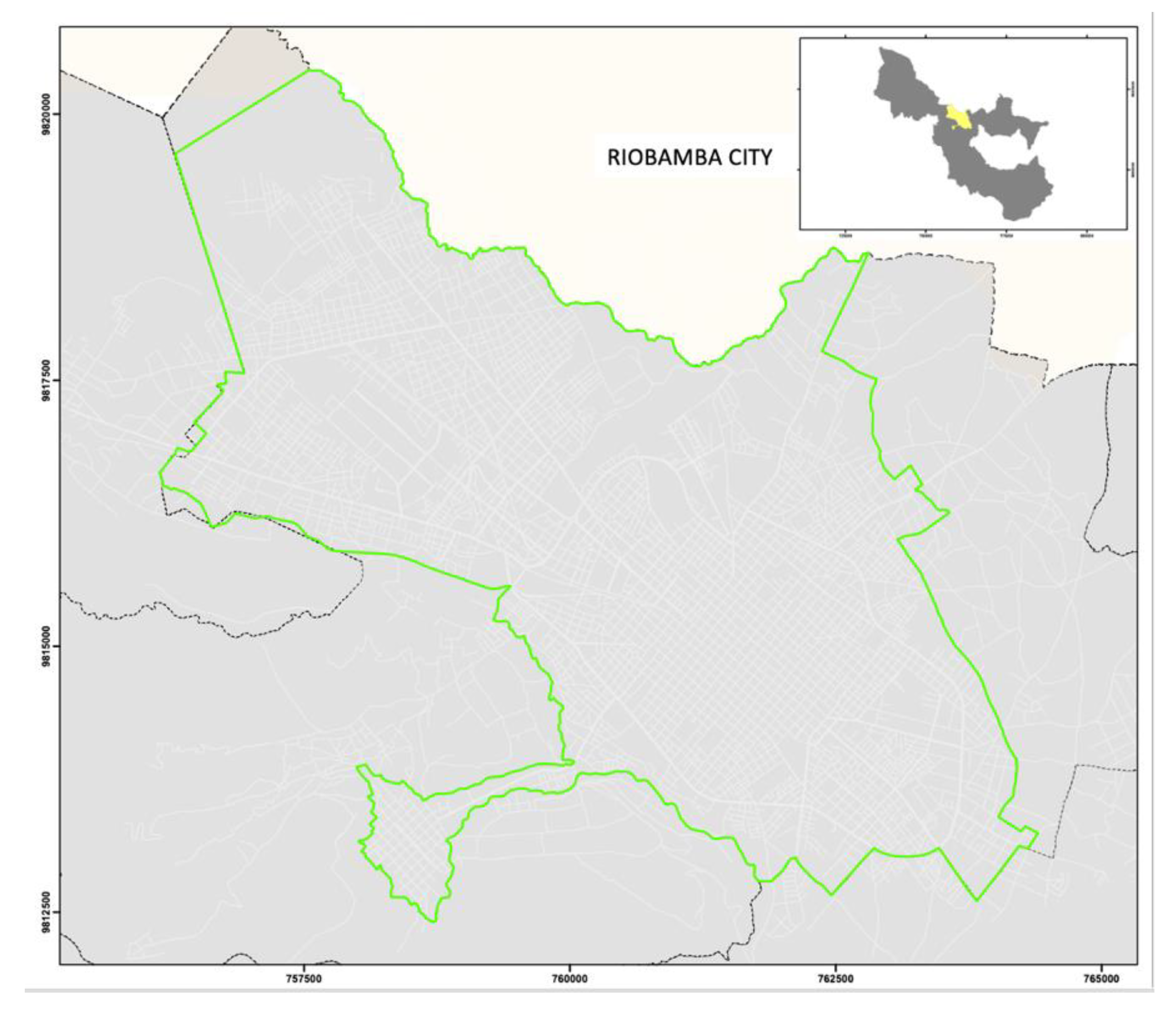

This study was conducted in the city of Riobamba, located in the central highlands of Ecuador at an elevation of approximately 2,754 meters above sea level. The city experiences a temperate highland climate with dry winters, classified as

Cwb (climate with dry winters and warm summers) under the Köppen climate classification system. Riobamba has an average annual temperature of 14 °C and is subject to moderate temperature variations throughout the year (

Figure 1).

Surface Temperature

Based on the data from the development and territorial planning plan, Riobamba is characterized by a cold climate due to its elevation of 2750 meters above sea level, experiencing an Andean cold climate. The monthly temperature variation indicates an annual average temperature of 13.4 °C, with a temperature amplitude of 2.8 °C throughout the year. Notably, the minimum temperature occurs in July, corresponding to the summer season, while maximum temperatures are observed at the end and beginning of the year.

This climatic scenario is significant in the context of global climate change, as evident from events like extreme temperature fluctuations and glacier reduction. In Ecuador, data from INAMHI (Instituto Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología) between 1969 and 2006 reveals an increase in the annual average temperature by 0.8 °C, with the maximum and minimum temperatures rising by 1.4 °C and 1 °C, respectively. Analyzing the temperature trends in Riobamba over the past 42 years (1976-2017), a slight decrease in average temperature is noted (-0.4 °C), while maximum temperature shows a subtle upward trend (slope = 0.2 °C). In contrast, minimum temperature and precipitation exhibit a significant increasing trend (0.3 °C and 0.39, respectively) at a 5% significance level. These trends underscore the evident impact of climate change in Riobamba, emphasizing the need for robust public policies to address environmental challenges, especially regarding health implications for the population.

Green Index

Urban green spaces play a crucial role in creating healthy, sustainable, and livable cities, as evidenced by international commitments and agreements emphasizing their establishment. The urban green index in Ecuador is 13.01 m2/inhabitant, which is within the range stated by the WHO, but many cities are not within that range, so Riobamba has one of the lowest values with 2.07 m2/inhabitant (Censos, 2023). Other more recent studies have calculated an urban green index for the city of Riobamba of 2.82 m2 per inhabitant, exceeding the figure determined by the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC) (Ocles Morales, 2021). The difference could be attributed to the increase in green areas through the planting of tree species promoted by the GADM of Riobamba, such as the “Plan Vida para Riobamba” project launched in 2018, which included the planting of thousands of trees in the city’s neighborhoods but has not been able to meet the objectives or the recommendations of international bodies.

Table 1.

Green area deficit per Macrozone in Riobamba city.

Table 1.

Green area deficit per Macrozone in Riobamba city.

| Macrozone |

Population |

Green area deficit m2 |

| 1 |

36345 |

3.85 |

| 2 |

34396 |

1.73 |

| 3 |

26021 |

4.13 |

| 4 |

18940 |

8.46 |

| 5 |

37596 |

0 |

| 6 |

10482 |

0 |

| 7 |

33689 |

3.59 |

| 8 |

41766 |

0 |

| 9 |

30330 |

1.27 |

| ZH (historical zone) |

9086 |

3.85 |

2.2. Methods

Research Design

The research followed a descriptive, cross-sectional design. This approach allowed for a detailed exploration of citizens’ perceptions and opinions regarding urban tree planting without manipulating variables or establishing causal relationships. The cross-sectional nature of the study enabled data collection at a single point in time, making it appropriate for assessing current perceptions. Additionally, secondary spatial and environmental data were incorporated to analyze relationships with tree density and citizen perceptions.

Citizen Perceptions

Trees play a vital role in providing ecosystem services that directly and indirectly enhance human well-being (F. Escobedo & Chacalo, 2008). Previous research has shown that urban trees contribute to improved physical and mental health (Turner-Skoff & Cavender, 2019). Understanding citizen perception is fundamental to the success and sustainability of urban forestry initiatives. Public participation and community engagement are key to long-term effectiveness. The study captured perceptions related to the value of trees, their contribution to health and quality of life, and preferences for their placement within the city.

Survey

Data were collected through a structured questionnaire designed and administered via the KoboToolbox platform. The questionnaire included 25 items divided into three thematic blocks: (1) socio-demographic characteristics, (2) perceptions of the benefits and disservices of urban trees, and (3) citizen preferences and awareness regarding tree planting programs. The questions were primarily closed-ended, utilizing Likert scales, multiple-choice, and dichotomous (yes/no) formats.

The instrument was reviewed by experts in urban environmental management and piloted with 20 participants to ensure clarity and consistency. Revisions were made accordingly prior to full deployment.

Sample

The target population for this study consisted of residents aged 15 years and older residing in the urban area of Riobamba, totaling 278,649 individuals. To determine the appropriate sample size, the formula for simple random sampling for finite populations was applied, yielding a minimum required sample of 400 participants.

A

stratified cluster sampling method was implemented, with the city’s macrozones serving as strata. Within each macrozone (

Figure 2), systematic random sampling was employed to ensure equitable representation across geographic areas. This approach ensured that the sample accurately reflected the distribution of the population in each macrozone.

The survey was carried out over a period of 20 days in June and July 2023. A total of 400 valid responses were collected and analyzed. The distribution of the sample across macrozones is shown in

Table 2.

The survey was conducted over 20 days from June to July 2023, targeting the general residents. Of a total of 400 responses collected were analyzed according to

Table 2.

Data Collection and Analysis

All data were compiled and cleaned prior to analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics and general perceptions of urban trees. Inferential statistical techniques, specifically chi-square tests of independence, were applied to examine associations between demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, education level) and perceptions of urban trees, including the value attributed to trees, motivation for physical activity, preference for native species, and perceived safety.

Cross-tabulations were also conducted to further explore whether perceptions of specific benefits (e.g., aesthetics, shade) or disservices (e.g., maintenance, allergies) varied significantly among different demographic groups. All analyses were conducted using Jamovi version 2.3.0.0 and Microsoft Excel, and descriptive visualizations were produced to support the interpretation of results.

3. Results

Demographic Characteristics

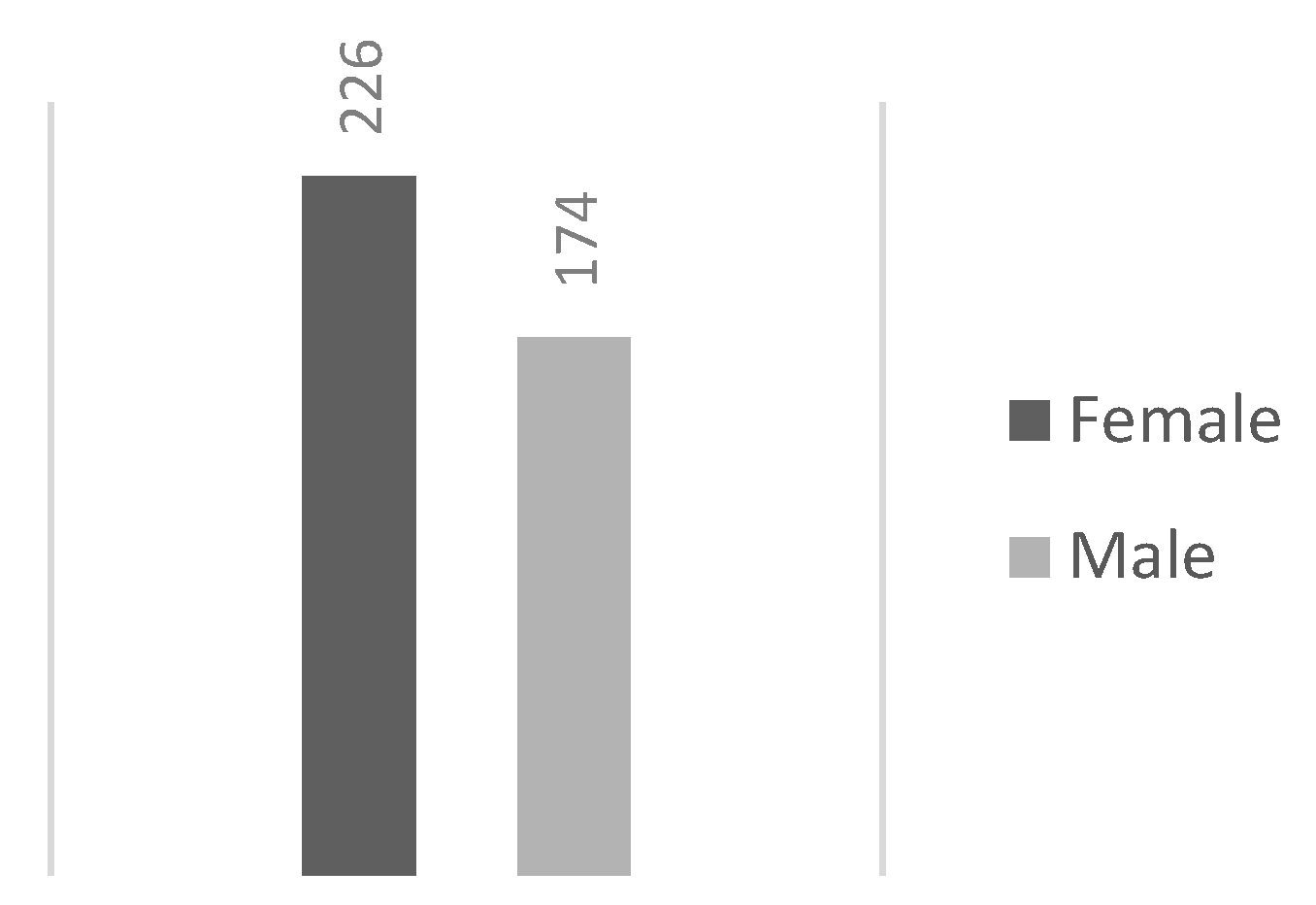

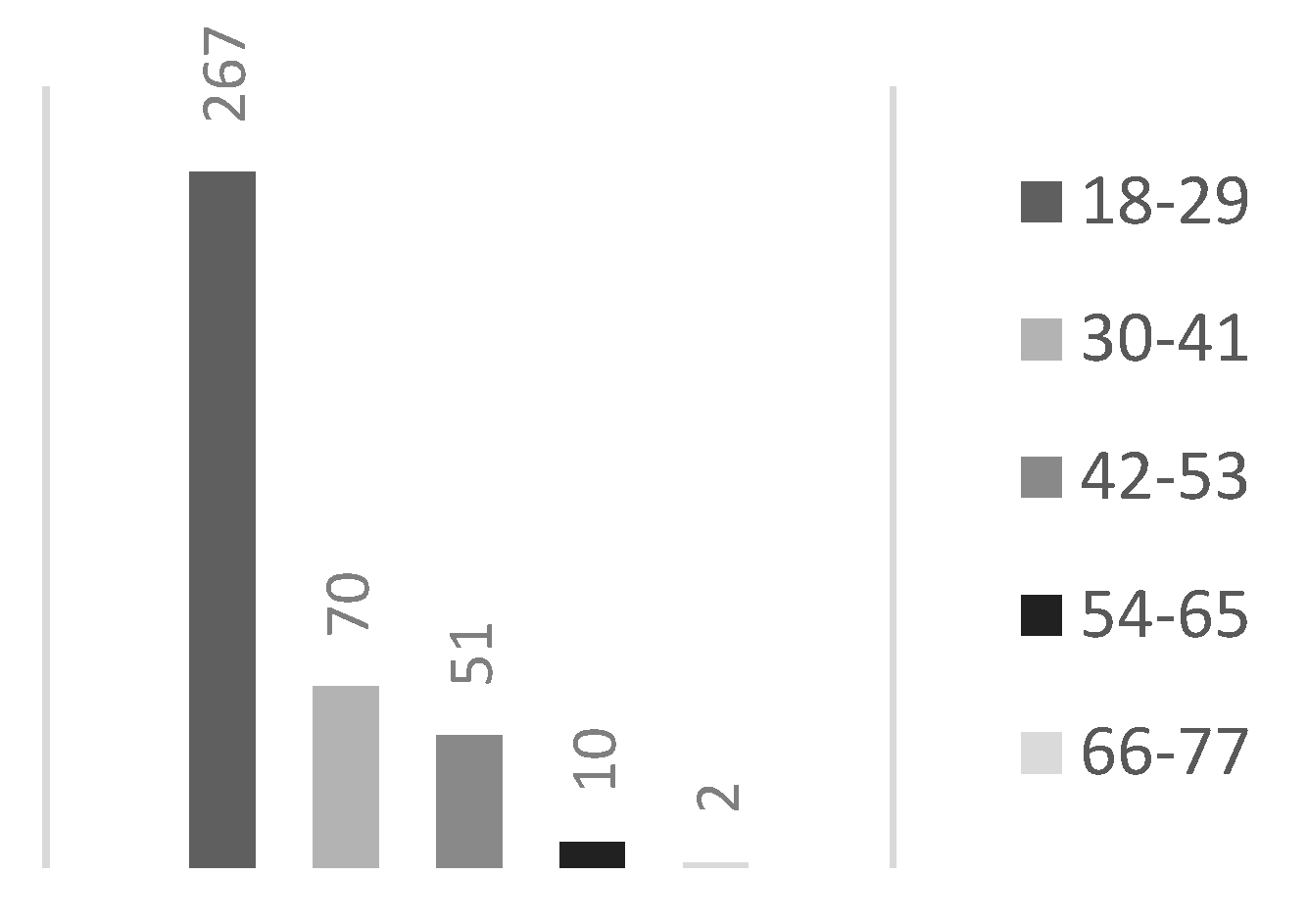

A frequency analysis was conducted to determine the demographic characteristics of the 400 respondents to the survey. The gender distribution revealed a higher proportion of females (226 respondents, 56.5%) compared to males (174 respondents, 43.5%) (

Figure 3). The age distribution indicated that most respondents were young adults, with the largest group being 18-23 years old (217 respondents, 54.3%), followed by smaller groups in the age brackets of 24-29 years (49 respondents, 12.3%), 30-35 years (36 respondents, 9.0%), 36-41 years (30 respondents, 7.5%), and 42-47 years (36 respondents, 9.0%) (

Figure 4). Only a few respondents were older, with 19 respondents (4.8%) in the 48-53 years bracket, 6 respondents (1.5%) in the 54-59 years bracket, 5 respondents (1.3%) in the 60-65 years bracket, and 2 respondents (0.5%) in the 66-71 years bracket.

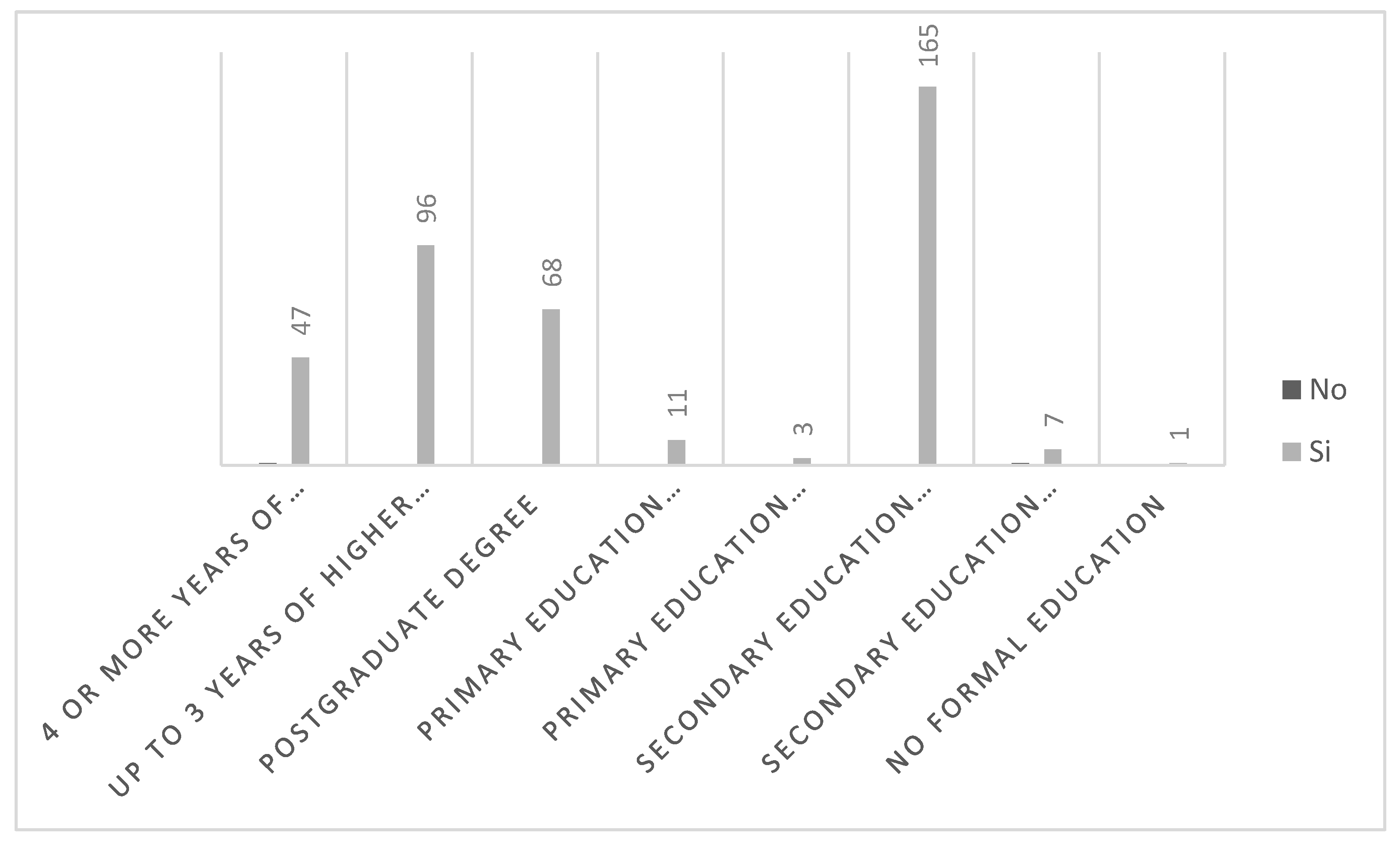

Regarding education levels, a significant portion of respondents had completed secondary education (165 respondents, 41.3%), while others had up to 3 years of higher education (96 respondents, 24.0%) or held postgraduate degrees (68 respondents, 17.0%). Smaller numbers had completed 4 or more years of tertiary education (48 respondents, 12.0%), primary education (11 respondents, 2.8%), or had primary incomplete (3 respondents, 0.8%). Very few respondents had secondary incomplete (8 respondents, 2.0%) or no education at all (1 respondent, 0.3%).

In terms of marital status, most respondents were single (304 respondents, 76.0%), followed by those who were married or cohabiting (74 respondents, 18.5%). Fewer respondents were divorced (19 respondents, 4.8%), widowed (2 respondents, 0.5%), or preferred not to disclose their marital status (1 respondent, 0.3%).

Overall, the respondents were predominantly young, female, and single, with most having completed secondary education. The predominance of young, educated respondents suggests a population segment that is likely more aware of and supportive of environmental initiatives, highlighting the importance of targeting such demographics in urban forestry policies and communication strategies.

Respondent Perceptions on Urban Green Space

Upon analyzing the responses gathered through the Perception of Urban Trees in Riobamba survey, a comprehensive overview of the community’s perspectives on urban trees has emerged. The participants, representing diverse locations within Riobamba, provided valuable insights into their perceptions of the role of trees in urban environments.

The survey’s findings demonstrate an unusually high degree of understanding and respect for the important function that urban trees play in Riobamba. Nearly all respondents 99.5% agreed that urban trees and forests are important for enhancing air quality and mitigating the negative health consequences of air pollution (Wolf et al., 2020), underscoring a shared understanding of the ecological importance of urban greenery. Moreover, when considering the impact of urban trees on temperature regulation, 61.3% states that trees contribute significantly, with an additional 24.8% expressing that their contribution is substantial. This recognition extends to the perceived benefits for well-being and mental health, with 65.3% of respondents attributing significant importance to the presence of trees in urban spaces.

The survey delves into the ecological impact of urban trees, revealing that 65.5% of the population believes that trees significantly contribute to increasing urban fauna, such as birds and butterflies. The findings also highlight the community’s sensitivity to climate change, as 69.5% have observed a significant warming of the city’s temperature, while 47.8% have noticed a significant cooling effect.

Perceptions of Safety and Lifestyle

Responder also associated trees with improvements in social well-being, expressing a strong willingness to actively engage in initiatives promoting urban forestry. Impressively, 57.8% are eager to participate in volunteer programs for tree planting and care, indicating a community-driven interest in contributing to the enhancement of the city’s green infrastructure. This aligns with the sentiment that 66.8% of the population believes that establishing tree-covered areas should be a top priority in the city’s planning and development.

The survey also provides insight into how people perceive the effect of urban trees on safety. Of those surveyed, 47.8% said that having trees in parks and streets significantly improves their sense of security in their neighborhood. The results show that trees may lower the rate of certain crimes and that the size, location, and health of the trees may all have an impact (Wolf et al., 2020). Furthermore, a noteworthy 65.3% of participants expressed a greater inclination to partake in physical activities in regions with copious tree coverage, underscoring the capacity of urban trees to favorably impact lifestyle decisions and demonstrating favorable correlations with urban tree exposure. In cross-sectional research, objectively assessed neighborhood tree cover was linked to greater levels of play among children, self-reported leisure walking in adults, and walking and cycling related to commuting among adolescents (Larsen et al., 2009; Nehme, Oluyomi, Calise, & Kohl III, 2016).

Civic Engagement and Preferences

Community engagement showed a mixed pattern, although 57.8% of respondents reported being willing to participate in volunteer programs for tree planting and care, the overall level of active involvement was not as high as the general awareness of benefits. At the same time, 66.8% of respondents considered that establishing tree-covered areas should be a top priority in the city’s planning and development. This contrast highlights that, while the community strongly values urban trees and recognizes their importance, the degree of direct participation remains relatively limited.

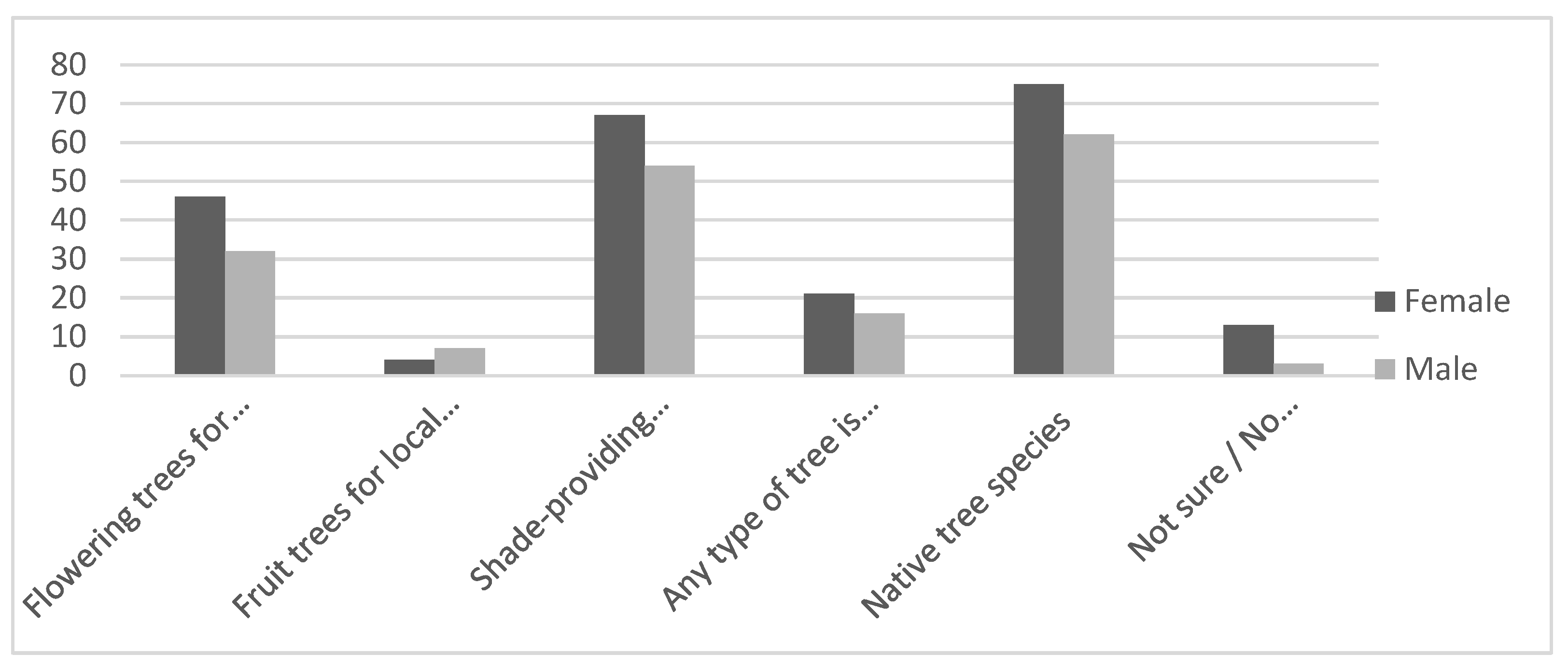

In terms of preferences, the community exhibits a strong desire for native tree species (34.3%) and those providing ample shade (30.3%), indicating a preference for trees that align with the region’s natural ecosystem. Lastly, an impressive 63.2% of respondents believe that urban trees can play a pivotal role in mitigating climate change, emphasizing the community’s recognition of trees as essential components of a sustainable and resilient urban environment in Riobamba.

Multivariable Analysis

To further explore the influence of sociodemographic factors on perceptions of urban trees, chi-square tests of independence were conducted between selected variables. The analysis revealed a statistically significant association between education level and the perception of the importance of trees (χ2 = 27.303, df = 7, p < 0.001). This result suggests that respondents with higher educational attainment were more likely to attribute greater importance to urban trees, highlighting the role of education in shaping environmental awareness and valuation.

In contrast, no significant associations were found between gender and preference for native tree species (p = 0.284), gender and motivation for physical activity in green areas (p = 0.133), education level and motivation for physical activity (p = 0.327), or gender and perception of safety (p = 0.849). These results indicate that, although perceptions of urban trees are widely positive across the community, they are not strongly differentiated by gender or education in most domains. The exception remains the perception of importance, which shows a clear dependence on education level, reinforcing the relevance of environmental education programs in promoting stronger pro-environmental attitudes.

The clustered bar chart shows that respondents with higher levels of education consistently rated urban trees as more important for air quality, well-being, and environmental benefits. This pattern is consistent with the statistically significant chi-square result (χ

2 = 27.303, df = 7, p < 0.001), which confirmed that perceptions of importance are associated with education level. Respondents with postgraduate or completed higher education were especially likely to rate trees as “very important,” highlighting the role of education in fostering environmental awareness (

Figure 5).

The bar chart illustrates that both men and women expressed a clear preference for native species and shade-providing trees, with little difference between genders. This finding reinforces the descriptive analysis, which showed that gender does not significantly influence tree species preference (χ

2 = 6.232, p = 0.284). The alignment of preferences across genders reflects shared cultural and ecological values, suggesting broad community support for the use of native and functional species in urban forestry planning (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

The urban heat island effect (UHI), in which temperatures are greater in urban areas than in surrounding rural areas (Arnfield, 2003), is a result of the record-breaking summer air temperatures that cities around the world are experiencing. This has major health implications for humans (Ziter et al., 2019). The variation in surface temperatures across different macrozones, as depicted in

Table 3, plays a pivotal role in shaping the urban environment of Riobamba. These temperature variations, coupled with the identified green area deficits per macrozone outlined in

Table 4, contribute significantly to the discussion surrounding urban planning, environmental sustainability, and the potential impact of climate on residents’ well-being.

Macrozones 5, 6, and 8, characterized by a higher average temperature of 16 °C, stand out as having a relatively warmer climate. A larger green area deficit also occurs in these warmer macrozones, underscoring the possible difficulties in reaching the suggested green space goals. Several studies reveal a significant impact of land-cover patterns on air temperature (Ziter et al., 2019). Given that the most effective strategies for mitigating urban heat will involve modifications to both green and gray infrastructure, the elevated temperatures in some macrozones highlight the significance of strategically planting trees and developing green infrastructure to address the deficit in green areas and contribute to temperature regulation (Ziter et al., 2019).

On the other hand, Macrozone 4, with a cooler average temperature of 13 °C, exhibits a smaller green area deficit. While the temperature is relatively cooler, indicating a potentially more favorable environment for certain tree species, there is still room for additional green spaces to align with international recommendations. This macrozone presents an opportunity to introduce diverse tree species that thrive in cooler climates.

The temperature and green area deficit data collectively highlight the need for nuanced and zone-specific urban planning strategies. For instance, in Macrozone 6, where both temperature and green area deficits are relatively high, targeted interventions, such as urban forestry projects and the establishment of green corridors, could offer dual benefits—ameliorating the deficit in green spaces and contributing to temperature regulation.

In Macrozone 1 and Macrozone 4, with lower temperatures and varying green area deficits, the focus may involve selecting tree species that are well-suited to cooler climates, thereby optimizing the ecological impact of urban greenery.

The survey results present a comprehensive snapshot of the community’s perceptions and attitudes towards urban trees in Riobamba, reflecting a collective awareness of the vital role trees play in the city’s ecosystem. With Riobamba situated in a unique climatic context characterized by its Andean cold climate, the impact of global climate change is evident in temperature trends. The slight decrease in the average temperature, coupled with an upward trend in maximum temperature and increased precipitation, underscores the significance of climate-related challenges that necessitate thoughtful urban planning and environmental policies.

One method of adjusting to the changing climate is to plant more trees (Ziter et al., 2019). The poll finds that respondents strongly agree on the value of urban trees, despite the city’s unique climate. Most people (99.5%) acknowledge that trees have a positive impact on air quality, which is in line with international norms. This highlights the crucial role that trees play in reducing environmental difficulties because using urban vegetation is frequently encouraged as a useful strategy to lower concentrations (Beckett, Freer-Smith, & Taylor, 2000). Furthermore, the identification of trees’ significant (61.3% substantially and 24.8% much) contribution to temperature regulation underscores their ability to mitigate the effects of climate change, including temperature extremes. Numerous studies have demonstrated the advantages that trees offer to communities and their citizens, and this belief has sparked national, international, and local campaigns to encourage the planting of urban trees (McDonald, Kroeger, Boucher, Wang, & Salem, 2016).

These findings feed into the perceptions investigated in this research, in which the community’s sensitivity to climate change is evident in the majority’s observation of significant warming (69.5%) and cooling effects (47.8%). This increased consciousness highlights the necessity of smart urban planning to improve a city’s ability to adapt to shifting weather patterns and to become more sustainable and habitable (Turner-Skoff & Cavender, 2019).

Notably, the survey underscores the community’s proactive stance towards urban forestry, with a significant percentage expressing willingness to participate in tree planting and care programs. This community-driven interest aligns with the majority’s belief (66.8%) that establishing tree-covered areas should be a top priority in the city’s planning and development. Urban forests can be most successfully integrated into sustainability strategies by planning alongside tar-getted site design and keeping an eye out for the particular characteristics of trees that contribute to human health and climate adaptation (Pataki et al., 2021). This presents a promising avenue for community engagement and collaboration in fostering a greener and more sustainable urban environment.

Research has shown that the amount of green space and the distance that urban dwellers must travel to that green space can influence the benefits of trees on public health (Annerstedt Van Den Bosch et al., 2016). These benefits are further highlighted by the perceived impact of urban trees on safety (47.8%) and their influence on physical activity motivation (65.3%).

The expressed preferences for native tree species (34.3%) and those providing ample shade (30.3%) reflect a desire for a harmonious integration of trees that align with the city’s natural ecosystem.

5. Conclusions

These temperature and green area deficit considerations underscore the interconnectedness of climate, urban planning, and the ecological landscape. Tailoring interventions based on the unique characteristics of each macrozone is essential for creating a sustainable and climate-resilient urban environment in Riobamba. As urban planners navigate the complexities of balancing temperature regulation and addressing green area deficits, a holistic approach that considers both climatic factors and specific zone requirements will be key to fostering a resilient and vibrant cityscape.

The survey results not only illuminate the community’s appreciation for the ecological significance of urban trees but also provide valuable insights for informed decision-making in urban planning and environmental policy development. The findings reinforce the importance of strategic interventions, community involvement, and a nuanced understanding of local preferences to create a resilient and sustainable urban landscape in Riobamba.

Addressing this deficit in a targeted manner, urban planners and local authorities can play a pivotal role in fostering sustainable urban development, enhancing the well-being of residents, and ensuring the resilience of Riobamba’s green infrastructure amidst the ongoing challenges of urbanization. This comprehensive examination of green areas within the context of Riobamba’s new urban code forms the cornerstone for our informed decision-making processes and the effective implementation of policies, ultimately contributing to the creation of a healthier and more sustainable urban environment.

Author Contributions

A.S.H., A.G.P., F.M.B., J.R.V., P.B.A., R.S.H., M.M.P., N.P.L., and D.V.N. contributed collaboratively to the development of this research article. A.S.H. was involved in conceptualization, methodology, and investigation. A.G.P. was responsible for project supervision and administration. F.M.B. contributed to formal analysis, validation, and visualization. J.R.V. supported data curation and resources. P.B.A. contributed to methodology and formal analysis. R.S.H. assisted in investigation and validation. M.M.P. contributed to visualization and critical review. N.P.L. was responsible for statistical analysis, validation, and review. D.V.N. contributed to writing and review. The original draft was prepared by A.S.H. with input from all authors during the writing—review and editing phases. All authors read and agreed to the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it involved anonymous surveys and public data analysis without personal identifiers, posing no risk to participants.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials are used in accordance with the guidelines of the journal as listed in the reference section. This study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles, and no specific ethical concerns were identified. Readers can access the datasets generated during the current study.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their heartfelt appreciation to the residents of Riobamba, whose active engagement and insightful contributions greatly enriched the success of this research. A special note of gratitude is extended to Fondo Verde for their indispensable support in postdoctoral training. Their dedicated commitment to environmental initiatives played a pivotal role in advancing our comprehension of and knowledge of prioritizing urban tree planting in Riobamba, Ecuador.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The study was conducted with full independence, and the authors were not influenced by any personal or financial relationships that could have affected the objectivity or impartiality of the reported research results. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results. The research was carried out with the sole intention of contributing to the scientific understanding of citizen perceptions and benefits related to the prioritization of urban tree planting in Riobamba, Ecuador.

References

- Akbari, H.; Konopacki, S. Calculating energy-saving potentials of heat-island reduction strategies. Energy policy 2005, 33(6), 721–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanís, E.; Jiménez, J.; Mora-Olivo, A.; Canizales, P.; Rocha, L. Estructura y composición del arbolado urbano de un campus universitario del noreste de México. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias 2014, 1(7), 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Annerstedt Van Den Bosch, M.; Mudu, P.; Uscila, V.; Barrdahl, M.; Kulinkina, A.; Staatsen, B.; Egorov, A. I. Development of an urban green space indicator and the public health rationale. Scandinavian journal of public health 2016, 44(2), 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnfield, A. J. Two decades of urban climate research: a review of turbulence, exchanges of energy and water, and the urban heat island; a Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society; International Journal of Climatology, 2003; Volume 23, 1, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett, K. P.; Freer-Smith, P.; Taylor, G. Particulate pollution capture by urban trees: effect of species and windspeed. Global Change Biology 2000, 6(8), 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J.; Banzhaf, S. What are ecosystem services? The need for standardized environmental accounting units. Ecological economics 2007, 63(2–3), 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Censos, I. N. d. E. y. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos » Indice Verde Urbano. 2023. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/indice-verde-urbano/.

- Change, I. P. O. C. Climate change 2007: The physical science basis. Agenda 2007, 6(07), 333. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, S. K.; Jackson, R. J. THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT AND CHILDREN’S HEALTH. Pediatric Clinics of North America 2001, 48(5), 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, C.; Nitschke, C. R.; Kendal, D. Global Drivers and Tradeoffs of Three Urban Vegetation Ecosystem Services. PLoS One 2014, 9(11), e113000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, M. P.; Piedrahita, P. Valoración económica del arbolado urbano en 28 comunas de Chile. Quebracho-Revista de Ciencias Forestales 2009, 17(1–2), 88–100. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, G. H. Including public-health benefits of trees in urban-forestry decision making. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2017, 22, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, W.; Wang, C.; Pei, N.; Zhang, C.; Gu, L.; Jiang, S.; Xu, X. Urban forests increase spontaneous activity and improve emotional state of white mice. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2019, 46, 126449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeigba, B. A.; Ashinze, U. K.; Umoh, A. A.; Biu, P. W.; Daraojimba, A. I. Urban green spaces and their impact on environmental health: A Global Review. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 2024, 21(2), 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, F.; Chacalo, A. Estimación preliminar de la descontaminación atmosférica por el arbolado urbano de la ciudad de México. Interciencia 2008, 33(1), 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo, F. J.; Kroeger, T.; Wagner, J. E. Urban forests and pollution mitigation: Analyzing ecosystem services and disservices. Environmental pollution 2011, 159(8–9), 2078–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fini, A.; Frangi, P.; Comin, S.; Vigevani, I.; Rettori, A. A.; Brunetti, C.; Ferrini, F. Effects of pavements on established urban trees: Growth, physiology, ecosystem services and disservices. Landscape and Urban Planning 2022, 226, 104501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlan, S. L.; Ruddell, D. M. Climate change and health in cities: impacts of heat and air pollution and potential co-benefits from mitigation and adaptation. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2011, 3(3), 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordán, R.; Rehner, J.; Samaniego, J. Megacities in Latin America: role and challenges. In Risk habitat megacity; 2012; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Laaidi, K.; Zeghnoun, A.; Dousset, B.; Bretin, P.; Vandentorren, S.; Giraudet, E.; Beaudeau, P. The impact of heat islands on mortality in Paris during the August 2003 heat wave. Environmental health perspectives 2012, 120(2), 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K.; Gilliland, J.; Hess, P.; Tucker, P.; Irwin, J.; He, M. The influence of the physical environment and sociodemographic characteristics on children’s mode of travel to and from school. American Journal of Public Health 2009, 99(3), 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuzinger, S.; Vogt, R.; Körner, C. Tree surface temperature in an urban environment. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2010, 150(1), 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.; Kroeger, T.; Boucher, T.; Wang, L.; Salem, R. Planting healthy air: a global analysis of the role of urban trees in addressing particulate matter pollution and extreme heat. Planting healthy air: a global analysis of the role of urban trees in addressing particulate matter pollution and extreme heat 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, E. G.; Nowak, D.; Heisler, G.; Grimmond, S.; Souch, C.; Grant, R.; Rowntree, R. Quantifying urban forest structure, function, and value: the Chicago Urban Forest Climate Project. Urban ecosystems 1997, 1, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, G.; Simpson, J. R.; Peper, P. J.; Maco, S. E.; Xiao, Q. Municipal forest benefits and costs in five US cities. Journal of forestry 2005, 103(8), 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messier, C.; Bauhus, J.; Sousa-Silva, R.; Auge, H.; Baeten, L.; Barsoum, N.; Zemp, D. C. For the sake of resilience and multifunctionality, let’s diversify planted forests! Conservation Letters 2022, 15(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehme, E. K.; Oluyomi, A. O.; Calise, T. V.; Kohl, H. W., III. Environmental correlates of recreational walking in the neighborhood. American journal of health promotion 2016, 30(3), 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, D. J.; Hirabayashi, S.; Doyle, M.; McGovern, M.; Pasher, J. Air pollution removal by urban forests in Canada and its effect on air quality and human health. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2018, 29, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, O. S.; Holt, A. R.; Warren, P. H.; Evans, K. L. Optimising UK urban road verge contributions to biodiversity and ecosystem services with cost-effective management. Journal of environmental management 2017, 191, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocles Morales, J. J. Cálculo del índice verde del componente forestal del área urbana del cantón de Riobamba provincia de Chimborazo, 2021.

- Oke, T. R. The energetic basis of the urban heat island. Quarterly journal of the royal meteorological society 1982, 108(455), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataki, D. E.; Alberti, M.; Cadenasso, M. L.; Felson, A. J.; McDonnell, M. J.; Pincetl, S.; Whitlow, T. H. The benefits and limits of urban tree planting for environmental and human health. Frontiers in ecology and evolution 2021, 9, 603757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey Mellado, R.; Franchini Alonso, M. T.; Del Pozo Sánchez, C. Soluciones basadas en la Naturaleza: estrategias urbanas para la adaptación al cambio climático. Hábitat y Sociedad 2021, (14), 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmond, J. A.; Tadaki, M.; Vardoulakis, S.; Arbuthnott, K.; Coutts, A.; Demuzere, M.; Wheeler, B. W. Health and climate related ecosystem services provided by street trees in the urban environment. Environmental Health 2016, 15(S1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, D. Cities’ contribution to global warming: notes on the allocation of greenhouse gas emissions. Environment and urbanization 2008, 20(2), 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Silva, R.; Cameron, E.; Paquette, A. Prioritizing street tree planting locations to increase benefits for all citizens: Experience from Joliette, Canada. Frontiers in ecology and evolution 2021, 9, 716611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-Skoff, J. B.; Cavender, N. The benefits of trees for livable and sustainable communities. PLANTS, PEOPLE, PLANET 2019, 1(4), 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Pauleit, S.; Seeland, K.; De Vries, S. Benefits and uses of urban forests and trees. In A reference book; Urban forests and trees, 2005; pp. 81–114. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, P. E.; Maiheu, B.; Vankerkom, J.; Janssen, S. Improving local air quality in cities: to tree or not to tree? Environmental pollution 183 2013, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolch, J. R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J. P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landscape and Urban Planning 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K. L.; Lam, S. T.; McKeen, J. K.; Richardson, G. R. A.; Van Den Bosch, M.; Bardekjian, A. C. Urban Trees and Human Health: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17(12), 4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Sumari, N. S.; Dong, T.; Xu, G.; Liu, Y. Characterizing urban expansion combining concentric-ring and grid-based analysis for Latin American cities. Land 2021, 10(5), 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF. Soluciones urbanas basadas en la naturaleza. Ciudades que lideran el camino 2021. 2023. Available online: https://www.wwf.org.pe/?372910/Soluciones-urbanas-basadas-en-la-naturaleza-Ciudades-que-lideran-el-camino-2021.

- Ziter, C. D.; Pedersen, E. J.; Kucharik, C. J.; Turner, M. G. Scale-dependent interactions between tree canopy cover and impervious surfaces reduce daytime urban heat during summer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116(15), 7575–7580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).