1. Introduction

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) is a global health challenge affecting millions, with a rising prevalence despite advancements in understanding and preventative measures [

1]. T2DM is a multifactorial syndrome characterized by abnormalities in carbohydrate and fat metabolism, resulting from a combination of insulin resistance and reduced pancreatic beta-cell function [

2,

3,

4]. The physiological mechanism of insulin secretion involves the uptake of glucose by beta-cells, which increases the intracellular ATP/ADP ratio, leading to the closure of ATP-dependent potassium channels and subsequent depolarization of the cell membrane [

5]. This depolarization opens voltage-gated Ca²⁺ channels, causing an influx of Ca²⁺ and triggering the release of insulin [

6].

Sulphonylureas (SUs) are a class of oral hypoglycemic agents that stimulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta-cells by binding to the sulphonylurea receptor 1 (SUR1), a subunit of the ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel [

7,

8]. By binding to SUR1, SUs cause the closure of the KATP channel, mimicking the effect of high ATP concentrations and leading to membrane depolarization and subsequent insulin release [

9]. While this mechanism is well-established, the specific molecular interactions responsible for the different potencies and durations of action (hypoglycemic effects) among different generations of SUs are not fully understood [

10].

Computational chemistry and molecular docking have become invaluable tools in drug discovery and development, providing insights into ligand-protein interactions and molecular mechanisms in a time and cost-effective manner [

11,

12,

13]. This study leverages these in-silico methods to bridge the knowledge gap regarding the specific bioorganic mechanisms of sulphonylurea activity. We aim to identify the key amino acid residues on SUR1 that interact with SUs, determine the factors influencing their potency, and investigate the reasons behind their varying half-lives and hypoglycemic effects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protein and Ligand Preparation

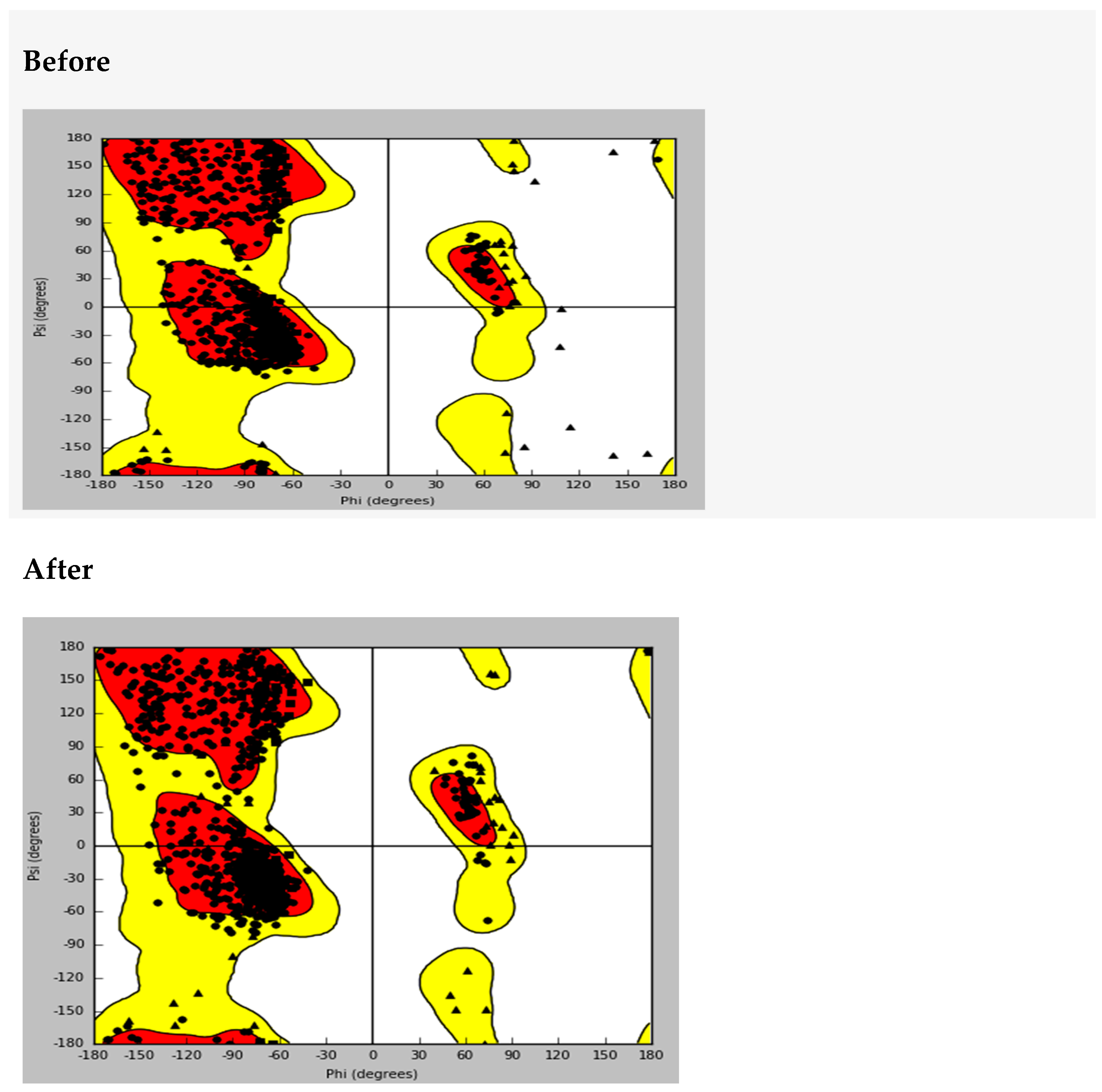

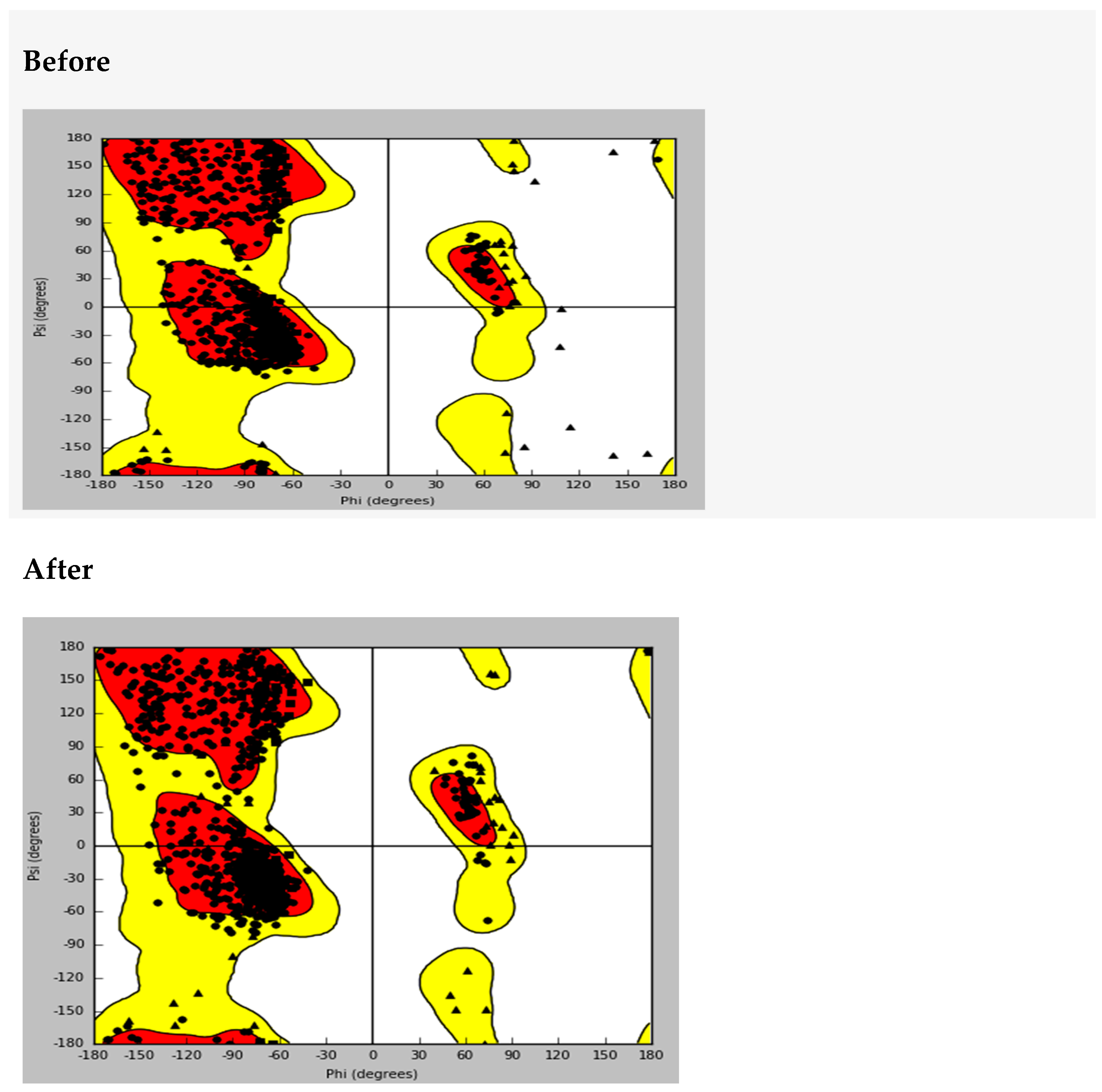

The protein structure of the sulphonylurea receptor 1 (PDB ID: 6PZA), which was co-crystallized with Glibenclamide, was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (RCSB). The protein was prepared using the Protein Preparation Wizard from the Schrödinger suite to minimize energy and relieve steric clashes. The quality of the 3D model was validated using a Ramachandran plot [

14,

15]. Ligands (sulphonylureas) were prepared using LigPrep to generate 3D coordinates and assign appropriate ionization/tautomeric states using the Epik tool.

2.2. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking was performed to predict the most favorable binding pose of each sulphonylurea ligand within the SUR1 binding pocket. The docking score, which is a combination of the Epik state penalty and the Glide score, was used for ranking and enrichment calculations. Docking method validation was performed by re-docking Gliclazide to 6PZA and comparing the results with previously published studies [

13].

2.3. Ligand Protein Interaction and MMGBSA Calculations

The binding interactions between the ligands and the protein were analyzed using ligand interaction diagrams. Parameters such as hydrogen bonding and pi-pi stacking were examined to understand the nature of the interactions. The binding energies of the sulphonylureas to SUR1 were determined using MMGBSA (Molecular Mechanics, General Born surface area) calculations. This method provides a more accurate estimation of binding free energy by accounting for solvation effects and conformational changes.

2.4. P450 Sites of Metabolism

The P450 sites of metabolism for each sulphonylurea were determined to understand the relationship between drug metabolism, half-life, and hypoglycemic effects. The intrinsic reactivity of SUs at CYP450 sites was calculated to identify the most likely metabolic pathways.

3. Results

Molecular Docking and Ligand-Protein Interactions

The protein structure for the sulphonylurea receptor 1 (SUR1) was prepared and validated using a Ramachandran plot, which confirmed its stereochemical quality and overall structural integrity (

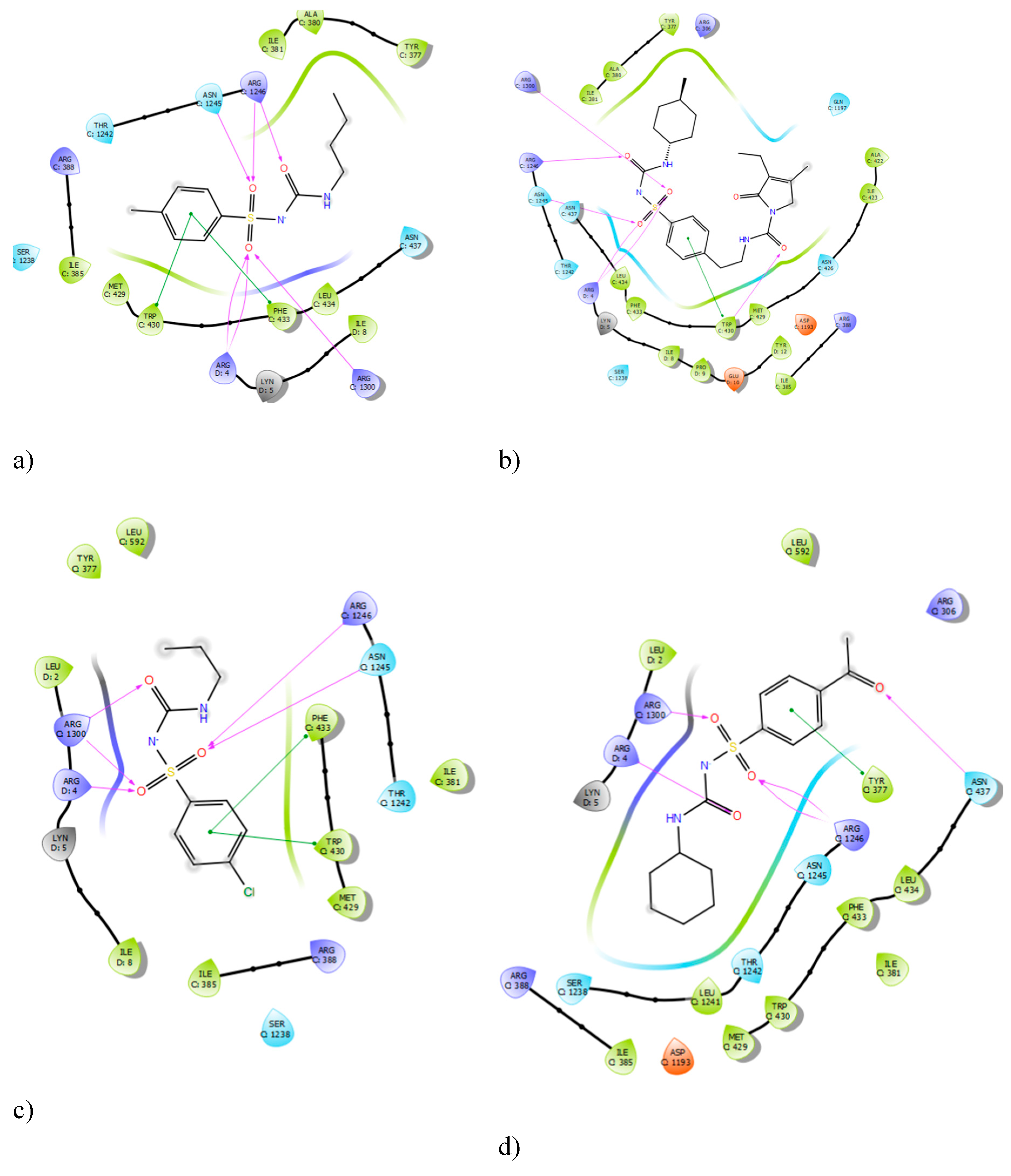

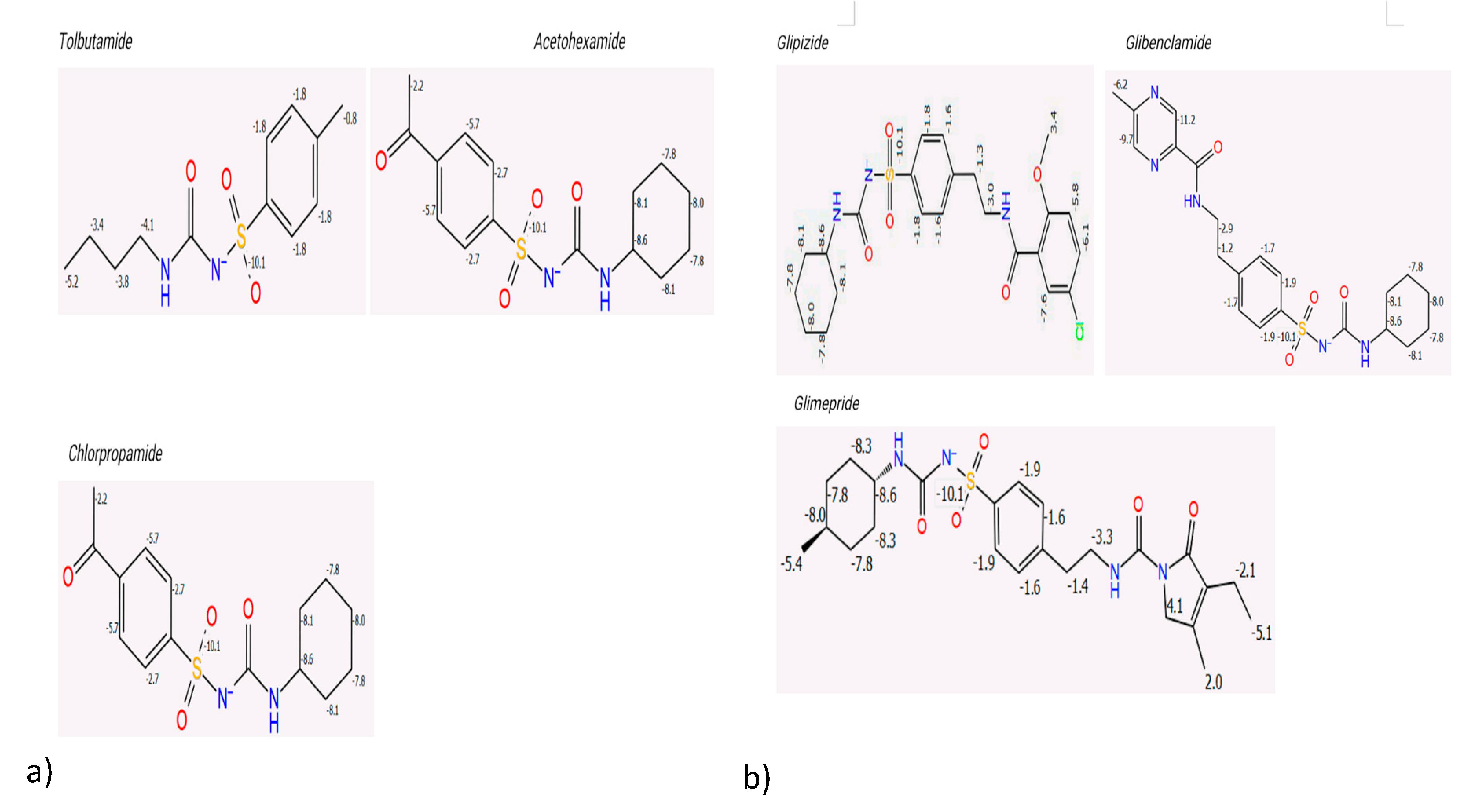

Appendix A.1). The molecular docking method was validated by comparing the binding interactions of complexed gliclazide with preliminary redocking results of the bound ligand, which was supported by the literature on pdb. The docking results successfully reproduced the hydrogen bond interactions of gliclazide with key residues ARG 1300 and ARG 1246, confirming the reliability of the computational approach used in this study.Analysis of the ligand interaction diagrams revealed consistent binding patterns across all sulphonylureas (SUs). The centrally located sulfonylurea group of each ligand consistently formed hydrogen bond interactions with the residues ARG 1300 and ARG 1246, as well as the ARG 4 residue. A summary of the frequency of these interactions is presented in

Table 1. The consistent interaction with these three arginine residues across all tested sulphonylureas suggests their critical role in the pharmacological activity of this class of drugs. This finding is further supported by previous studies which showed that mutating ARG 1246 and ARG 1300 significantly reduces sulphonylurea binding.

Figure 1.

Ligand Interaction Diagrams of Sulphonylureas with SUR1 with a)Tolbutamide, b) Glimepiride, c)Chlopropamide and d)glicazide.

Figure 1.

Ligand Interaction Diagrams of Sulphonylureas with SUR1 with a)Tolbutamide, b) Glimepiride, c)Chlopropamide and d)glicazide.

Table 1.

Frequency of Residue Interactions with Sulphonylurea Ligands.

Table 1.

Frequency of Residue Interactions with Sulphonylurea Ligands.

| |

ARG

1300 |

ARG

1246 |

ARG

4 |

ASN

1245 |

ASN

437 |

TRP

430 |

TRP

377 |

PHEN

433 |

TRP

30

|

TYR

12

|

| Glimepiride |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

| Glibenclamide |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

|

| Gliclazide |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Glipizide |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gliquidone |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

| Acetohexamide |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

|

| Tolbutamide |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| Chlorpropamide |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

| Tolazamide |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

Relationships between Activity and Computational Parameters

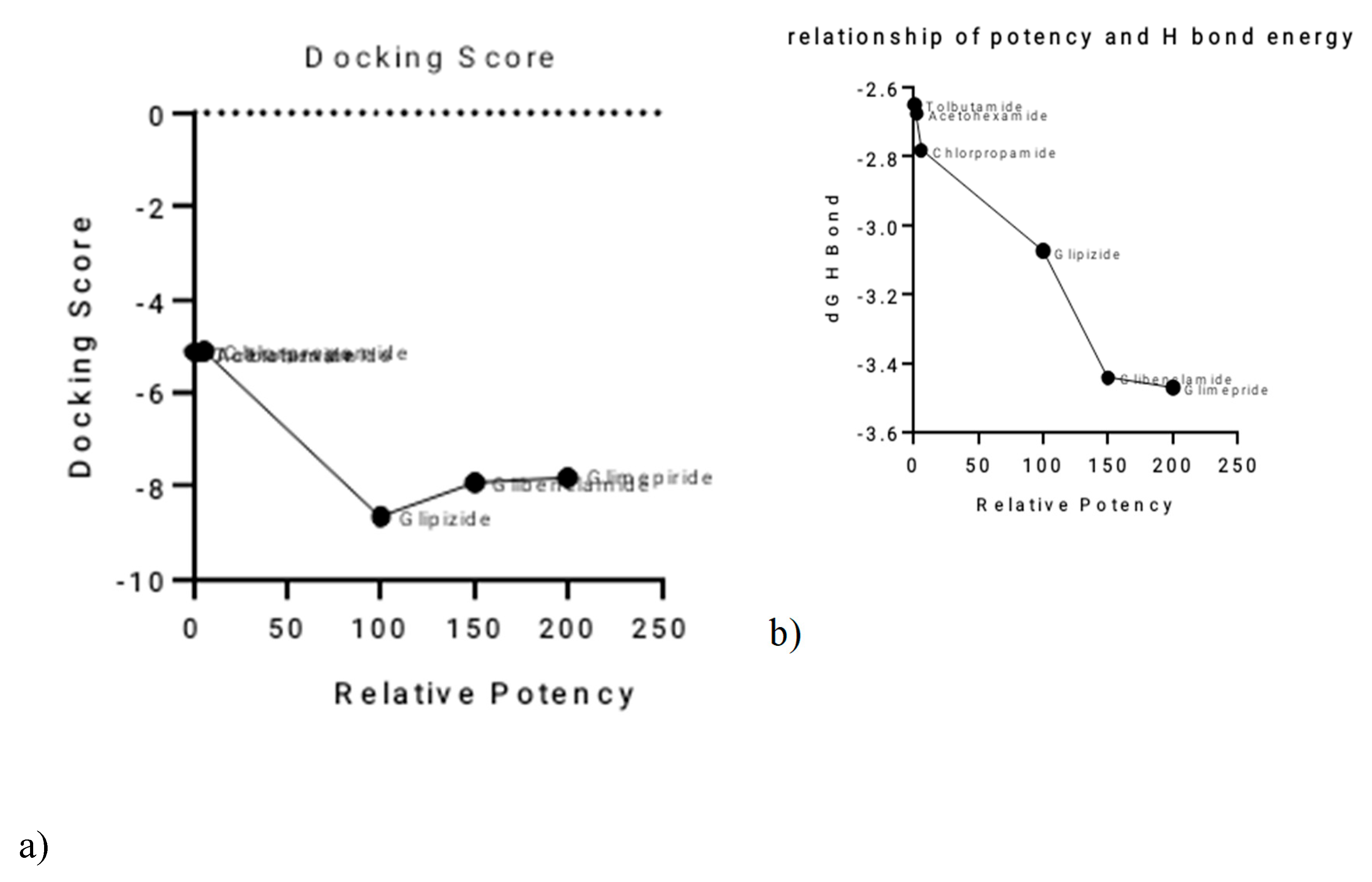

A clear inverse relationship was observed between the relative potency of the sulphonylureas and their total hydrogen bond energy (

Figure 2a,b). Glimepiride, the most potent SU, exhibited the most negative total H-bond energy, with a value of −3.47064 kcal/mol. Conversely, the least potent SUs, such as Tolbutamide, had less negative H-bond energy values. This suggests that the strength of hydrogen bonding plays a significant role in determining the differences in potency among the sulphonylureas.The relationship between relative potency and total binding energy (

Figure 2c) showed a general trend where increased potency was associated with decreased total binding energy. This relationship was not perfectly linear, with a notable inflection point after Chlorpropamide. Similarly, the correlation between relative potency and ligand efficiency (

Figure 2d) also showed inverse proportionality, with some outliers, particularly Tolbutamide and Acetohexamide. A summary of these relationships and the corresponding values is provided in

Table 2.

Figure 2.

Correlation of Sulphonylurea Relative Potency with Key Computational Parameters.

Figure 2.

Correlation of Sulphonylurea Relative Potency with Key Computational Parameters.

Table 2.

Summary of Relative Potency against computational parameters.

Table 2.

Summary of Relative Potency against computational parameters.

| Drug |

Relative Potency (nm) |

Docking Score kcal/mol |

MMGBSA dG Bind H Bond

Kcal/mol |

MMGBSA_dG_Bind

Kcal/mol |

Ligand Efficiency

Kcal/mol |

| Tolbutamide |

1 |

-5.128 |

-2.65070 |

-18.8434 |

-0.285 |

| Acetohexamide |

2.5 |

-5.128 |

-2.6755

45 |

-17.1521 |

-0.246 |

| Chlorpropamide |

6 |

-5.102 |

-2.78334 |

-8.37358 |

-0.3 |

| Glipizide |

100 |

-8.656 |

-3.07364 |

-23.51570 |

-0.279 |

| Glibenclamide |

150 |

-7.937 |

-3.44163 |

-28.90450 |

-0.241 |

| Glimepride |

200 |

-7.803 |

-3.47064 |

-18.791 |

-0.229 |

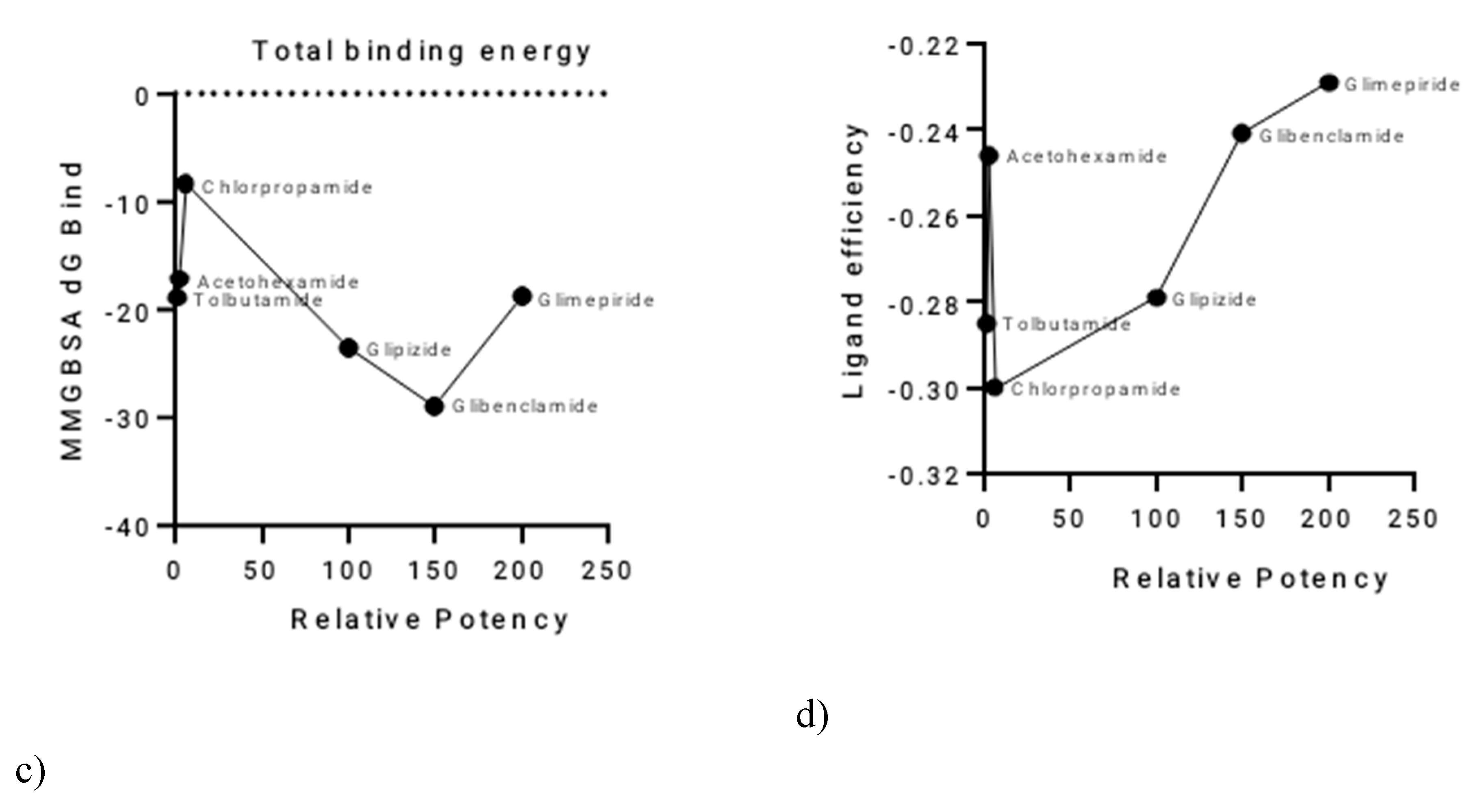

P450 Sites of Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics

The P450 sites of metabolism were determined to evaluate the intrinsic reactivity of each sulphonylurea. The results showed a significant inverse proportionality between the total intrinsic reactivity and the half-life of the drugs (

Figure 3 and

Table 3). Sulphonylureas with a higher total intrinsic reactivity tended to have shorter half-lives. This finding indicates that the number of metabolic sites and their intrinsic reactivity are key determinants of the different hypoglycaemic effects observed for each drug. First-generation sulphonylureas generally showed more intrinsic reactivity compared to the second-generation drugs, which aligns with their known shorter half-lives.

Figure 3.

Intrinsic Reactivity of First and Second-Generation Sulphonylureas.

Figure 3.

Intrinsic Reactivity of First and Second-Generation Sulphonylureas.

Table 3.

Summary of Relative Potency, Pharmacodynamic, and Pharmacokinetic Parameters for Sulphonylureas.

Table 3.

Summary of Relative Potency, Pharmacodynamic, and Pharmacokinetic Parameters for Sulphonylureas.

| Drug |

Half-life (Hr) |

Total intrinsic reactivity |

| Tolbutamide |

5 |

-77.1 |

| Acetohexamide |

10 |

-85.9 |

| Chlorpropamide |

12 |

-96.9 |

| Glipizide |

25 |

-33.88 |

| Glibenclamide |

29 |

-77.5 |

| Glimepiride |

36 |

-39.9 |

4. Discussion

This study utilized a computational approach to provide a deeper understanding of the bioorganic mechanisms of sulphonylurea activity, offering valuable insights that complement traditional experimental methods. The molecular docking results confirmed that sulphonylureas bind to the SUR1 protein, with the consistent identification of ARG 1300, ARG 1246, and ARG 4 as critical binding residues. This finding is significant as it provides a precise molecular target for drug design. The bidentate hydrogen bonding observed between chlorpropamide and ARG 1300 is a key structural insight into the ligand-protein interaction, which can be further exploited for designing more effective drugs. The validation of these residues with previous studies strengthens the conclusions of this work [

16].

The analysis of the relationship between computational parameters and drug activity yielded important findings. The lack of a direct correlation between docking scores and potency suggests that while docking can predict a favorable binding pose, it may not fully capture the nuanced interactions that define therapeutic potency [

11]. Instead, the inverse proportionality between the total hydrogen bond energy and potency provides a more direct measure of binding strength and its impact on drug effectiveness [

17]. This highlights the importance of specific non-covalent interactions in determining the overall drug-receptor affinity, a key consideration for rational drug design.

Furthermore, the study successfully linked the number of CYP450 intrinsic reactivity sites to the observed half-lives and hypoglycemic side effects of the sulphonylureas. The finding that first-generation sulphonylureas, with fewer metabolic sites, have significantly longer half-lives provides a clear bioorganic explanation for their prolonged hypoglycemic effects and higher risk of inducing hypoglycaemia compared to the second-generation drugs [

18]. This is a critical insight for clinical practice, informing the selection of appropriate sulphonylurea therapy. It underscores how computational prediction of metabolic pathways can be used to forecast clinical outcomes and reduce the risk of adverse drug reactions.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully used a computational approach to determine the bioorganic mechanisms of sulphonylurea activity and the causes of their differing hypoglycemic effects. Through molecular docking, we established that the interaction of sulphonylureas with the amino acid residues ARG 1300, ARG 1246, and ARG 4 on the sulphonylurea receptor 1 is critical for their therapeutic activity. The differences in potency among sulphonylurea generations can be attributed to their varying total hydrogen bond energies, which showed an inverse relationship with their potency. Furthermore, the study concluded that the differences in the number of CYP450 intrinsic reactivity sites and the molecular size of the drugs are responsible for the varying half-lives and the associated hypoglycemic side effects. These findings provide a deeper understanding of the molecular basis of sulphonylurea pharmacology and offer valuable insights for the rational design of new antidiabetic agents with improved efficacy and reduced side effects.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, Tafara Masuka. and Craig Chirenje; methodology, Tafara Masuka; software, Dr A Wakandigara.; validation, Craig Chirenje, Dr A Wakandigara, Amos Misi and Dr P Mushonga; formal analysis, Adoren Ngarivhume & Craig Chirenje; investigation, Tafara Masuka & Roy Bisenti.; resources, Dr A Wakandigara; data curation, Craig Chirenje, Adoren Ngarivhume and Tafara Masuka; writing—original draft preparation, Tafara Masuka & Roy Bisenti.; writing—review and editing, Roy Bisenti, Adoren Ngarivhume, Dr P Mushonga, & Dr A. Wakandigara; visualization, Roy Bisenti; supervision, Craig Chirenje, Adoren Ngarivhume & Amos Misi; project administration, Tafara Masuka & Craig Chirenje.; funding acquisition, Amos Misi. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Ramachandra’s Plot Before and After Protein Preparation

References

- Rob A, Hoque A, Miah Md Asaduzzaman, Ahmed A, Khalil R, Thomas D, et al. The Global Challenges of Type 2 Diabetes. Bangladesh J Med. 2025, 36, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra JVS, Dias MMG, Brilhante AJVC, Terra MF, García-Arévalo M, Figueira ACM. Multifactorial Basis and Therapeutic Strategies in Metabolism-Related Diseases. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruze R, Liu T, Zou X, Song J, Chen Y, Xu R, et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: connections in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatments. Front Endocrinol. 2023, 14.

- LeRoith, D. β-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes: role of metabolic and genetic abnormalities. Am J Med. 2002, 113, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamarit-Rodriguez, J. Stimulus–Secretion Coupling Mechanisms of Glucose-Induced Insulin Secretion: Biochemical Discrepancies Among the Canonical, ADP Privation, and GABA-Shunt Models. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 2947–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ježek P, Holendová B, Jabůrek M, Tauber J, Dlasková A, Plecitá-Hlavatá L. The Pancreatic β-Cell: The Perfect Redox System. Antioxidants. 2021, 10, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F. Diabetes and Antidiabetic Drugs. Benthamdirect.com. 2024, 220–294. [Google Scholar]

- Aljabali, B. An Overview of the Pharmacogenetics of Sulfonylurea in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Adv Pharm Res. 2024, 8, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri K. SULFONYLUREAS: A REVIEW OF THEIR SAFETY. Certif J │ Seshadri Al World J Pharm Res [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jan 1];12. Available from: https://wjpr.s3.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com/article_issue/777e1f47e487639a31ce18de51dd029f.pdf.

- Rébecca Goutchtat. Modeling intestinal glucose absorption with oral D-Xylose test for the study of its contribution on postprandial glucose response : studies in minipigs and in humans. Hal.science [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jan 1]; Available from: https://theses.hal.science/tel-04426309/.

- Macip G, Garcia-Segura P, Mestres-Truyol J, Saldivar-Espinoza B, Ojeda-Montes MJ, Gimeno A, et al. Haste makes waste: A critical review of docking-based virtual screening in drug repurposing for SARS-CoV-2 main protease (M-pro) inhibition. Med Res Rev. 2021, 42, 744–769. [Google Scholar]

- Utkarsha Naithani, Vandana Guleria. Integrative computational approaches for discovery and evaluation of lead compound for drug design. Front Drug Discov. 2024, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Oluwafisayo Akintemi E, Kuben Govender K, Singh T. Molecular Dynamics and Docking Investigation of Flavonol Aglycones against Sulfonylurea Receptor 1 (SUR1) for Anti–diabetic Drug Design. ChemistrySelect. 2024, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Bahia MS, Kaspi O, Touitou M, Binayev I, Dhail S, Spiegel J, et al. A comparison between 2D and 3D descriptors in QSAR modeling based on bio-active conformations. Mol Inform. 2023, 42, 2200186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima S, Albuquerque MG. Development, validation and analysis of a human profurin 3D model using comparative modeling and molecular dynamics simulations. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2023, 42, 5428–5446. [Google Scholar]

- Lee VS, Sukumaran SD, Tan PK, Kuppusamy UR, Arumugam B. Role of surface-exposed charged basic amino acids (Lys, Arg) and guanidination in insulin on the interaction and stability of insulin–insulin receptor complex. Comput Biol Chem. 2021, 92, 107501. [Google Scholar]

- Haritha M, Sreerag M, Suresh CH. Quantifying the hydrogen-bond propensity of drugs and its relationship with Lipinski’s rule of five. New J Chem. 2024, 48, 4896–4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins L, Costello RA. Nih.gov. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK551568/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).