Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Method

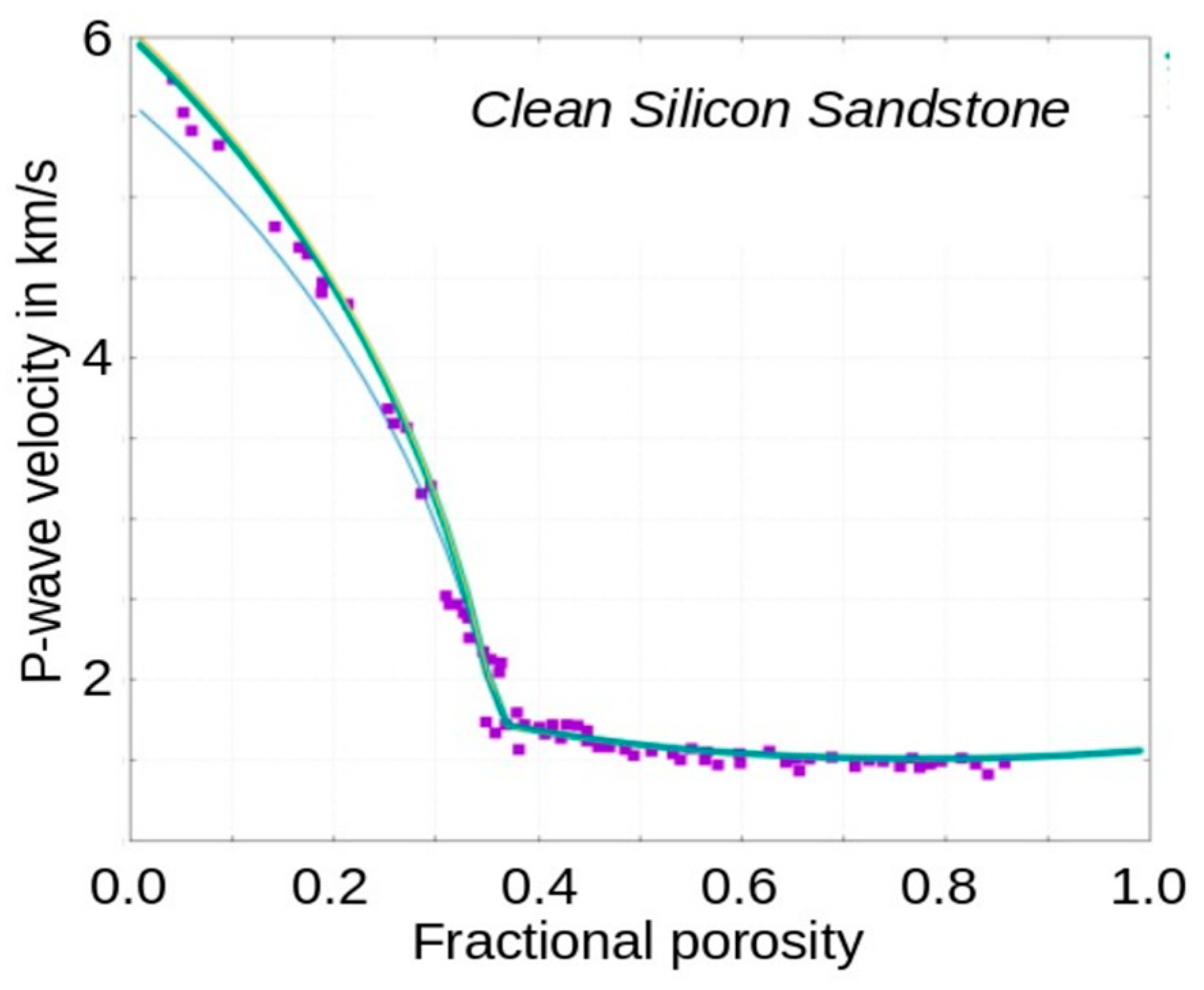

Sandstone

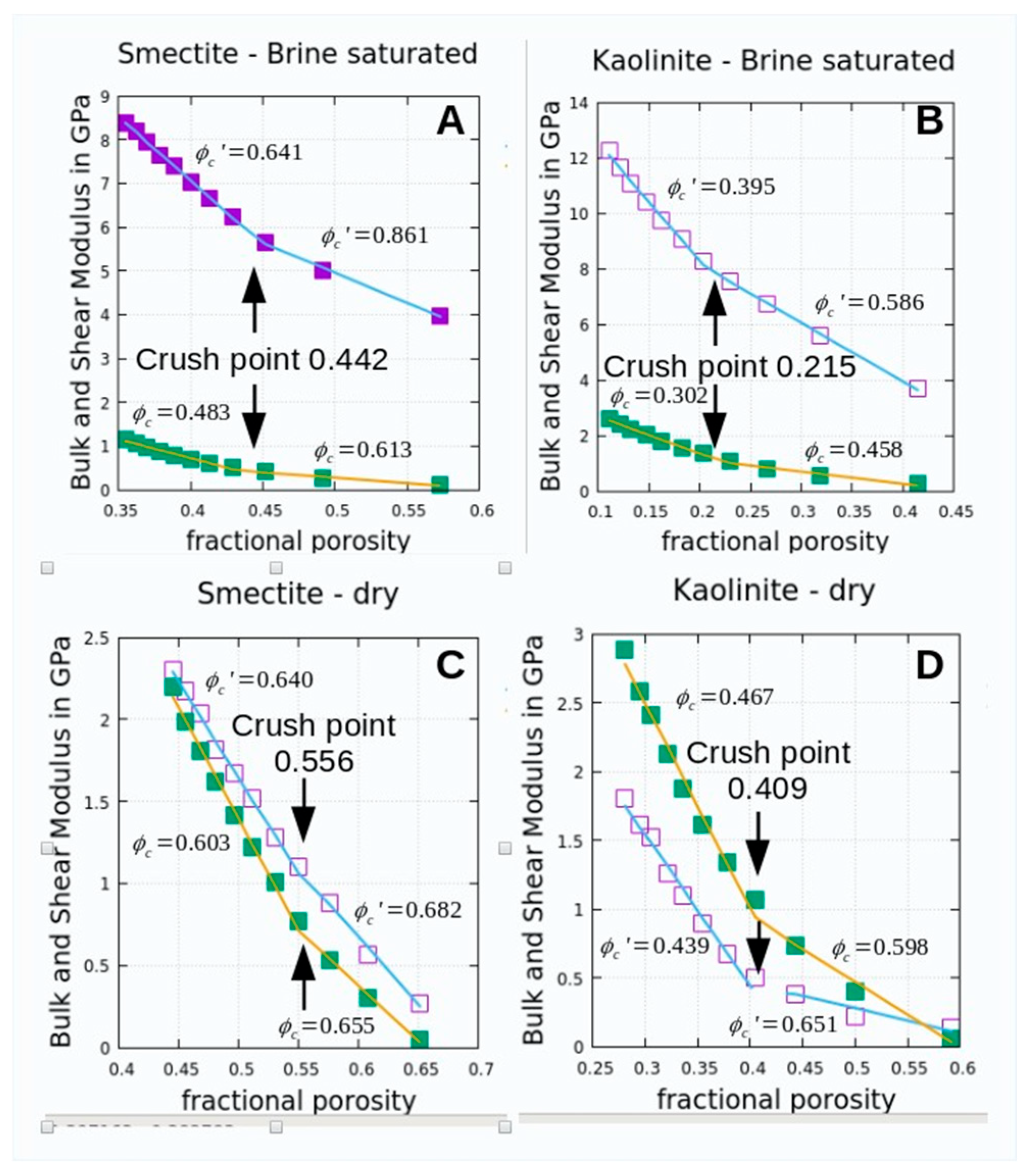

Shale

Avoiding

Quartz-Shale Composite Models

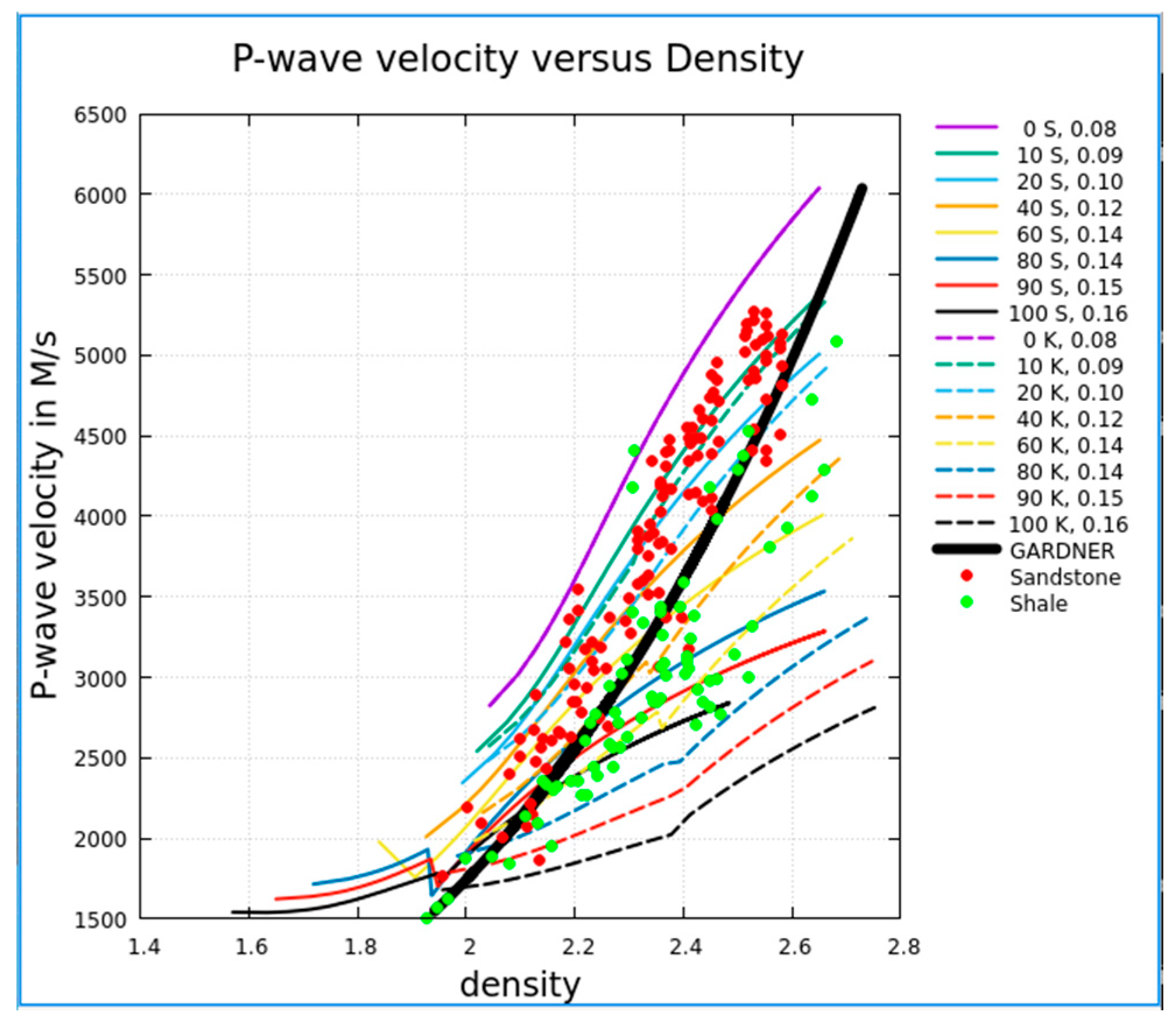

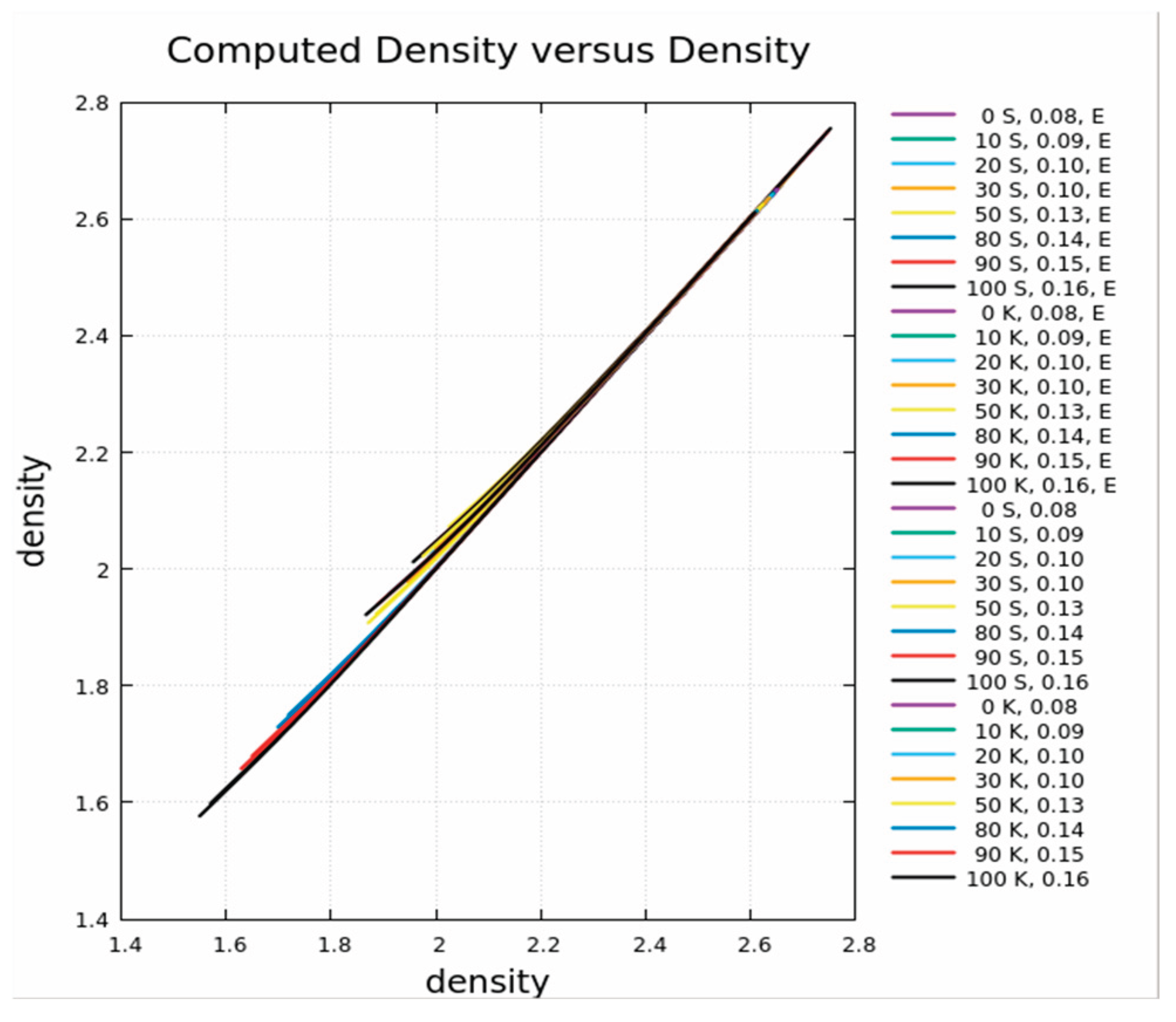

Results

Conclusions

Modified Gassmann-Nur Model

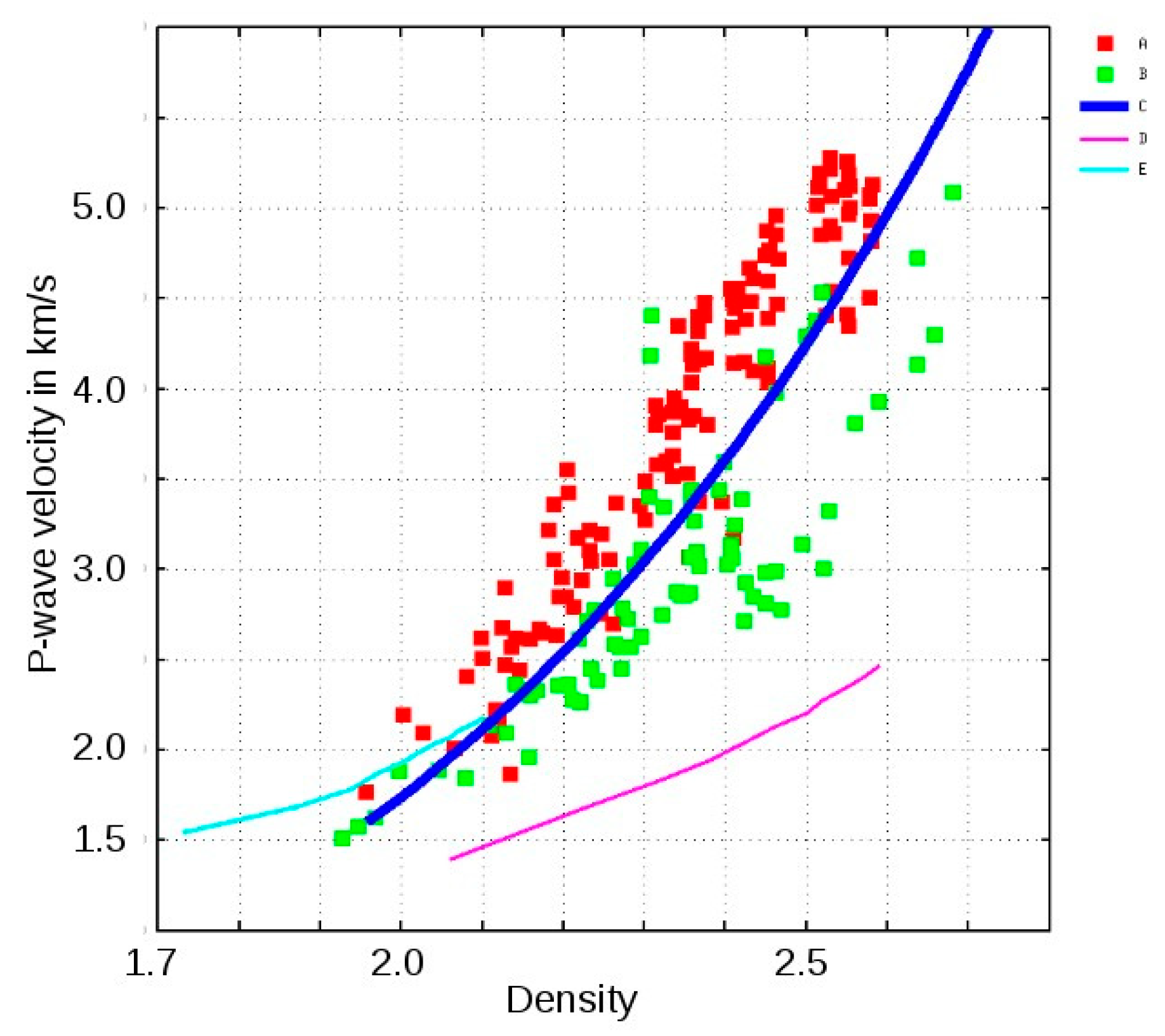

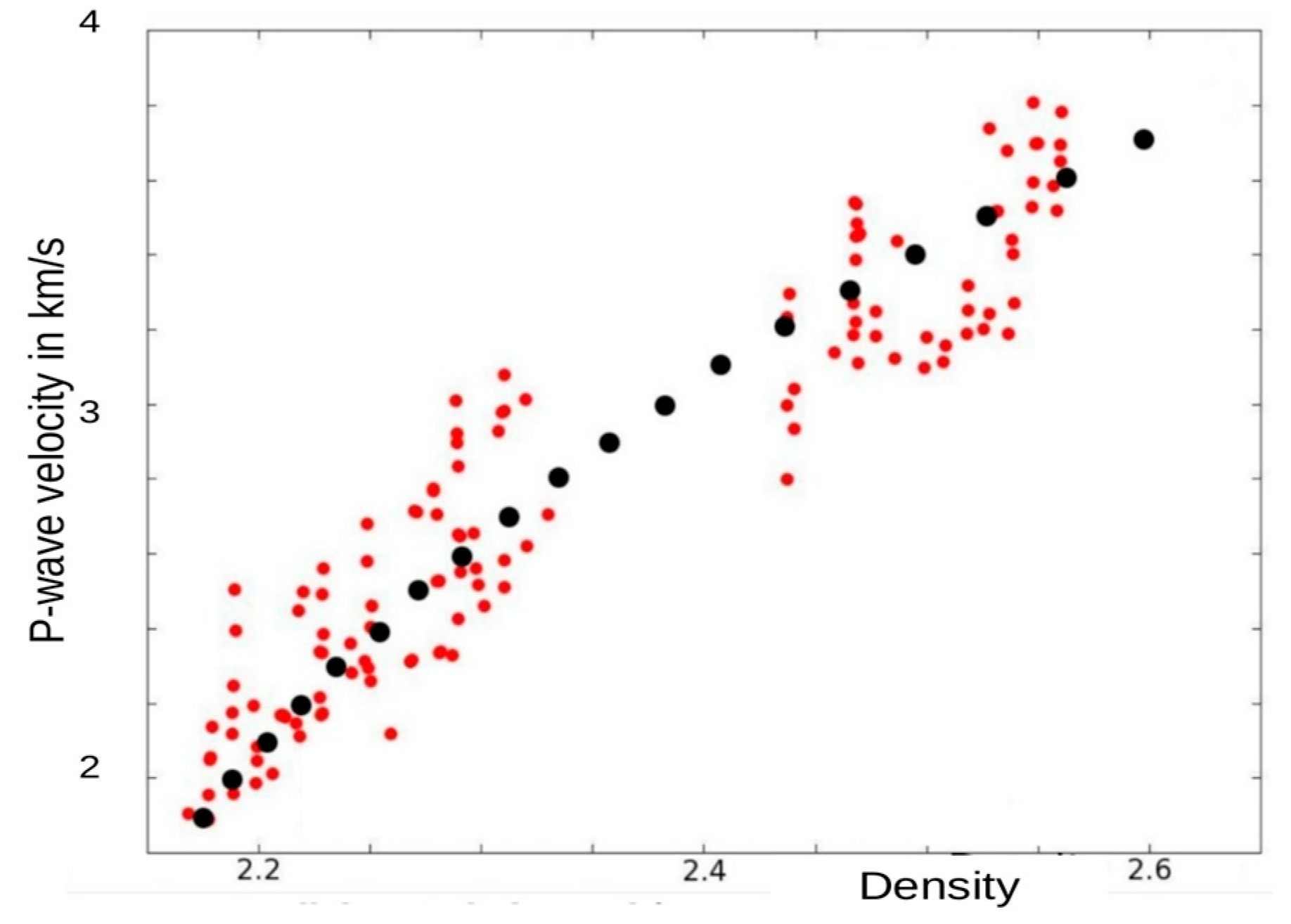

Gardner’s Equation

Funding

Conflicts of interest

Appendix A Path to Gassman’s Equations

References

- Castagna, J.P., Batzle, M.L., & Kan, T.K. (1993). Rock physics – the link between rock properties and AVO response. In J.P. Castagna & M.M. Backus (Eds.), Offset-dependent reflectivity: theory and practice of AVO Analysis. SEG, 135-171.

- Aplin, A.C.; Yang, Y.; Hansen, S. Assessment of β the compression coefficient of mudstones and its relationship with detailed lithology. 2000, 12, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, G.H.F.; Gardner, L.W.; Gregory, A.R. Formation velocity and density-the diagnostic basics for stratigraphic traps. Geophysics 1974, 39, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondol, N.H.; Jahren, J.; Bjørlykke, K.; Brevik, I. Elastic properties of clay minerals. Lead. Edge 2008, 27, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassmann, F. ELASTIC WAVES THROUGH A PACKING OF SPHERES. Geophysics 1951, 16, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavko, G.; Mukerji, T. Comparison of the Krief and critical porosity models for prediction of porosity and VP/VS. Geophysics 1998, 63, 925–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginbotham, J.H.; Macesanu, C.; Brown, M.P.; Ramirez, O.; Joanne, C. An alternative amplitude analysis theory. SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts 2012. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–5.

- Nur, A., Mavko, G., Dvorkin, J., & Galmundi, D. (1998). Critical porosity: A key to relating physical properties to porosity in rocks. The Leading Edge, 357.

- Mavko, G., Mukerji, T., & Dvorkin, J. (2009). The Rock Physics Handbook (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Vernik, L.; Kachanov, M. Modeling elastic properties of siliciclastic rocks. Geophysics 2010, 75, E171–E182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernik, L.; Kachanov, M. 2010.

- Higginbotham, J.H. Gassmann-Nur-Aplin Pore Pressure Prediction. SEG Annual Meeting Technical Program Expanded Abstracts. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Higginbotham, J.H.; Brown, M.P.; Ramirez, O. 2011.

- Berryman, James G., (1999), Origin of Gassmann’s equations, GEOPHYSICS 64: 1627-1629.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).