Introduction

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare but highly aggressive skin cancer that belongs to the group of non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC) [

1,

2]. Mostly diagnosed in patients between the 6

th and 8

th decade of life it is highly aggressive and develops very early distant and regional recurrences and distant metastases after treatment [

3].

Besides age and immunosuppression, recent studies could show that infection with the Merkel Cell Polyomarvirus (MCPyV) and UV exposure are among the most important factors for MCC development [

4,

5]. Nevertheless, there is still a significant lack of data in the majority of countries worldwide, in particularly of UV radiation over a long observation period and the possible link to carcinogenesis of MCC [

4].

In this study, we used data from MCC patients who were diagnosed between the years 1990 and 2018. Data were derived from the Austrian National Cancer Registry (ANCR), operated by the National Statistical Institution, Statistics Austria, in order to determine the incidence of MCC and the distribution within Austria. Those data, were secondly correlated with UV data and compared to patient’s demographics, TNM classification, body localization and overall survival after diagnosis.

Methods

Anonymous data on all Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) in patients were derived from the Austrian National Cancer Registry (ANCR). The ANCR is population-based and operated by the National Statistical Institution, Statistics Austria. All new cancer cases in the Austrian resident population are documented in the ANCR. According to the Cancer Statistics Act 1969 and the Cancer Statistics Ordinance 2019, hospitals are obliged to report every case of cancer and every death from cancer. In most federal states, regional or clinical tumor registries act as service providers for the hospitals and carry out data collection and processing in the respective state. Both for data directly from hospitals as well as for data from registries, plausibility and quality criteria apply that are closely linked to international recommendations. For follow-up and to ascertain death certificate only (DCO) cases, ANCR data is linked with the official causes of death (CoD) statistics derived from Statistics Austria since 1983 (

https://www.statistik.at/fileadmin/shared/QM/Standarddokumentationen/B_2/std_b_krebsstatistik.pdf). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee (1892/2017).

Clinicopathological information used for this study were tumor site, histology and behavior year of diagnosis, sex, age (5-years age groups, up to 95+), staging (based on TNM or description of the extent of disease), diagnosis, region of residence, date of death and overall survival (ICD-O classification, third edition). Unfortunately, data does not contain information regarding immunosuppression and the MCPyV status. Data on cause of death could not be used since CoD uses ICD-10 coding (ICD-10-GM Version 2025), which does not provide specific codes for MCC. MCC is subsumed under “other malignant neoplasms of the skin”.

The cohort of this study included all Austrian cancer cases with documented MCC diagnose from 1990 to 2018 and follow-up ends with December 31st, 2019 (Data stock from the ANCR on 17.12.2020). Data before 1990 could not be used, as the version of the classification used at that time did not allow the identification of MCC. From 1990 to 2002, tumor site was coded according to ICD-9 and histology code of ICD-O-1 (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Version 1) was used to code the tissue type. Not only were new incoming reports coded according to the new version, but the entire database was converted. The two-digit codes were replaced by corresponding four-digit codes. These are correspondingly unspecific for the period up to 1990, as the previous coding according to the two-digit code led to a considerable loss of information. The codes were recoded in accordance with international standards. From 2002 to 2006, the ICD-O-2 (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Version 2) was used for both localization and histology. The ICD-O-3 (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Version 3) has been used since 2006. Since 2020, the ICD-O-3 (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Version 3) has been used in revision 2. As with the previous change of coding classification, the entire database was recoded.

Using the ICD-O-3 code (C44/8247/3), we identified patients with MCC of the skin documented in the ANCR. Tumor site was determined using the last digit in the ICD-O-3 code for lip (=0), eyelid (=1), ears (=2), other/unspecified parts of the face (=3), scalp and neck (=4), trunk (=5), upper extremities and shoulder (=6), lower extremity and hip (=7), skin, overlapping several sub-areas (=8) and not specified (=9). Codes from 0 to 4 were merged and determined as head and neck. MCCs were coded as localized, regional or disseminated disease based on the TNM classification and further information, describing growth beyond the boundaries of the organ, lymph node status and the presence of distant metastases, received from clinical and pathological staging. MCC was diagnosed either by an open biopsy or by fine needle aspiration cytology.

Within the ANCR the municipality code of the patient´s main residence at time of diagnosis is stored and was assigned to federal states by ANCR for this study. Overall survival was counted from the day of diagnosis until date of death or end of follow-up, (December 31st, 2019). Incidence of disease per 100.000 residents was calculated according to the distribution of the Austrian population from 1990 to 2018 and are indicated as mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean). UV-exposure was available for each political district and year (including data of each single day, week and month) between 1958 and 2001.

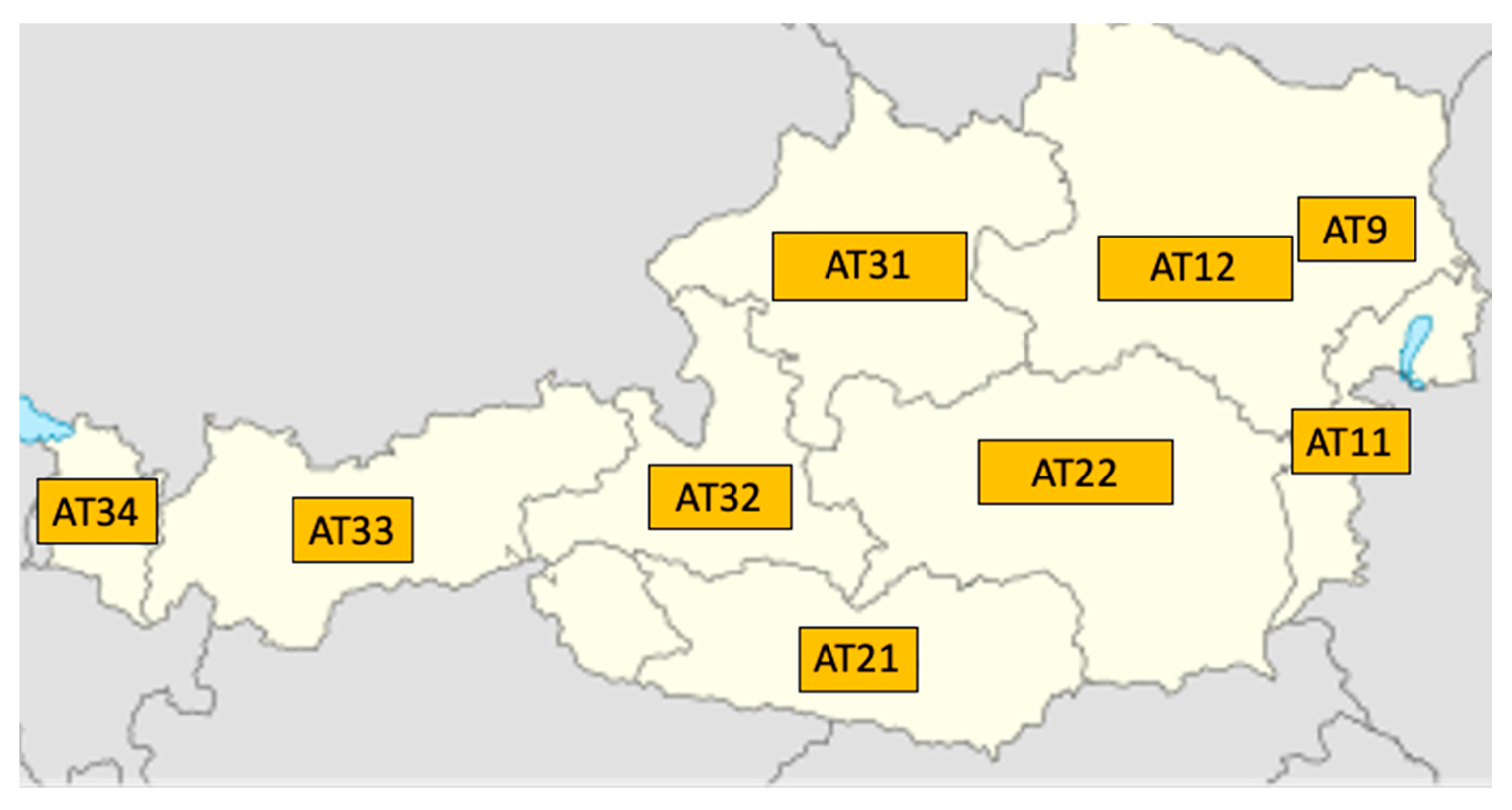

Unit of UV irradiation is counted in Watt per square meter (W/m2). Subsequently, the UV index is calculated from the highest UV value per day (half-hourly value) by multiplying the numerical value by a factor of 40 and rounding to a whole number. The UV index is therefore a pure numerical value without a unit. The mean (= annual average of all UV values that were measured daily), maximum (= highest UV value of the year) and sum (= the annual sum of all daily measured UV values of a year) of UV values were then calculated for each year according to NUTS (Nomenclature of territorial units for statistics) per county (AT 11 = Burgenland, AT 12= Lower Austria AT9 = Vienna,, AT 21= Carinthia, AT 22 = Styria, AT 31 = Upper Austria, AT 32 = Salzburg, AT 33 = Tyrol and AT 34 = Vorarlberg) [

6]

Figure 1.

These data were then combined to render nationwide UV data and were correlated with incidence, using a Pearson/Spearman´s rho correlation (r). Next, we divided the dataset according to NUTS into East Austria (AT 11, AT 12 and AT 13) and West Austria (AT 21, AT 22, AT 31, AT 32, AT 33 and AT 34).

Patients´ data were analyzed using statistical software R version 3.0.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SPSS software (version 26; IBM SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). Incidences, as well as UV data (mean and maximal UV values), were separately compared using a paired t-test. Fishers’ exact test was used to compare proportions. All tests are two-sided and p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Between January 1

st 1990 and December 31

st 2018, a total of 538 patients with MCC of the skin were diagnosed in Austria and documented in the ANCR. All clinicopathological and demographic data are shown in

Table 1. In general, people diagnosed with MCC were elderly with 98.7% (n=531) of patients ≥ 50 years and 40.3% (n=217) even ≥ 80 years. There was a majority of 314 (58.4%) women compared to 224 (41.6%) men with a 1.4:1 ratio. The median age was 75 years and the median overall survival 33.9 months.

Diagnosis was carried out in 93.7% (n=504) following surgery and only in 1.9% (n=10) biopsy analysis was performed. Method of diagnosis was not retrievable for 24 samples. Although the number of patients with no exactly determined tumor site was 30.1% (n=162) in our cohort, the most common tumor site was the head and neck area with 37.9% (n=204), followed by upper (13.6%, n=73) and lower (12.1%, n=65) extremities. The lowest incidence rates were observed of the trunk (6.1%, n=33) and for overlapping regions (0.2%, n=1).

Staging

Staging was available for 308 (57.2%) out of 538 registered cases and only data of those 308 patients were used for further analysis. At the time of diagnosis, 136 (44.2%) patients showed already initial lymphatic node spread and 44 (14.3%) cases presented even with a distant metastatic disease. Tumor size was not determined, but only categorized as growth within the boundaries of the organ (

Table 1).

Incidence

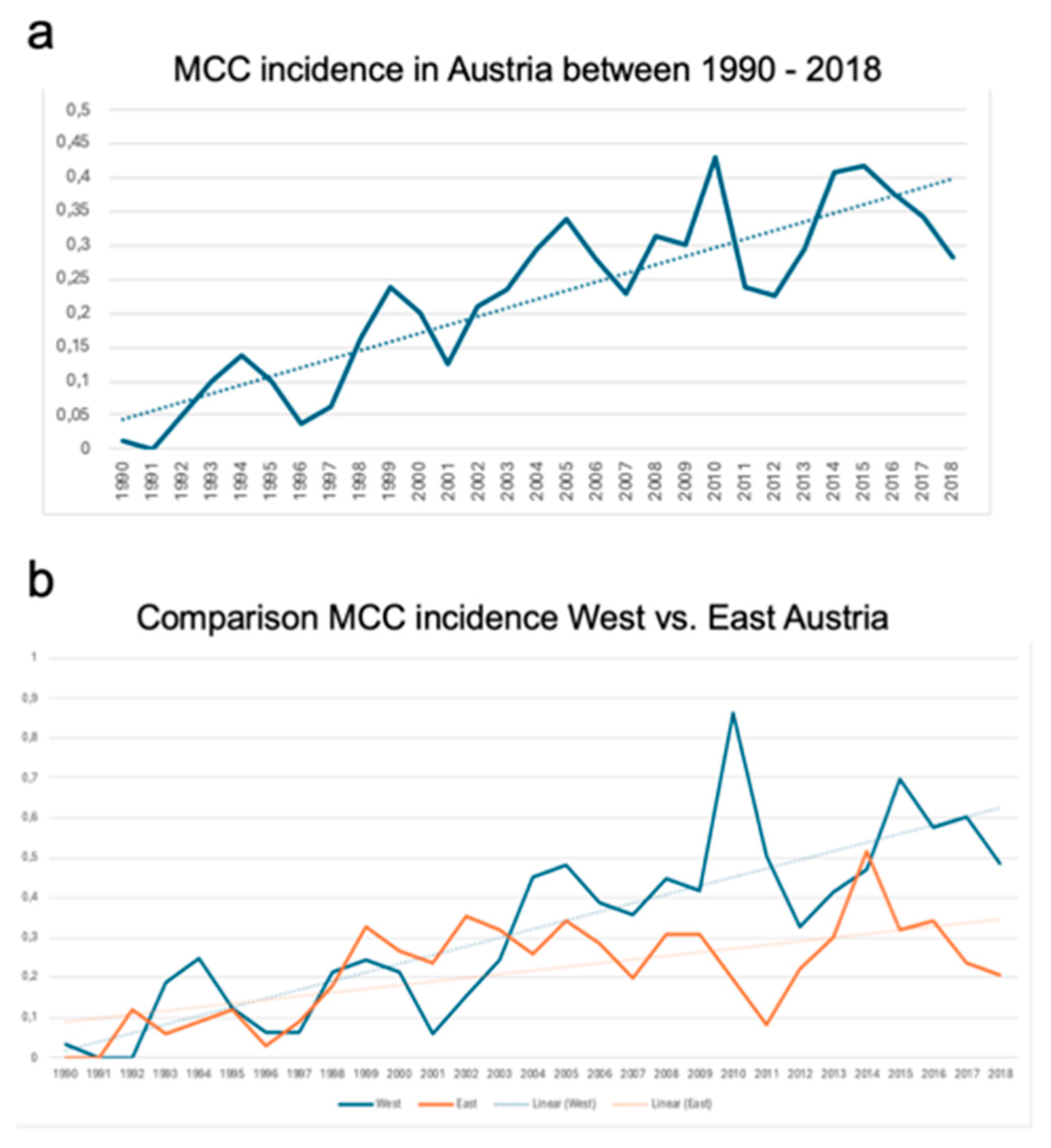

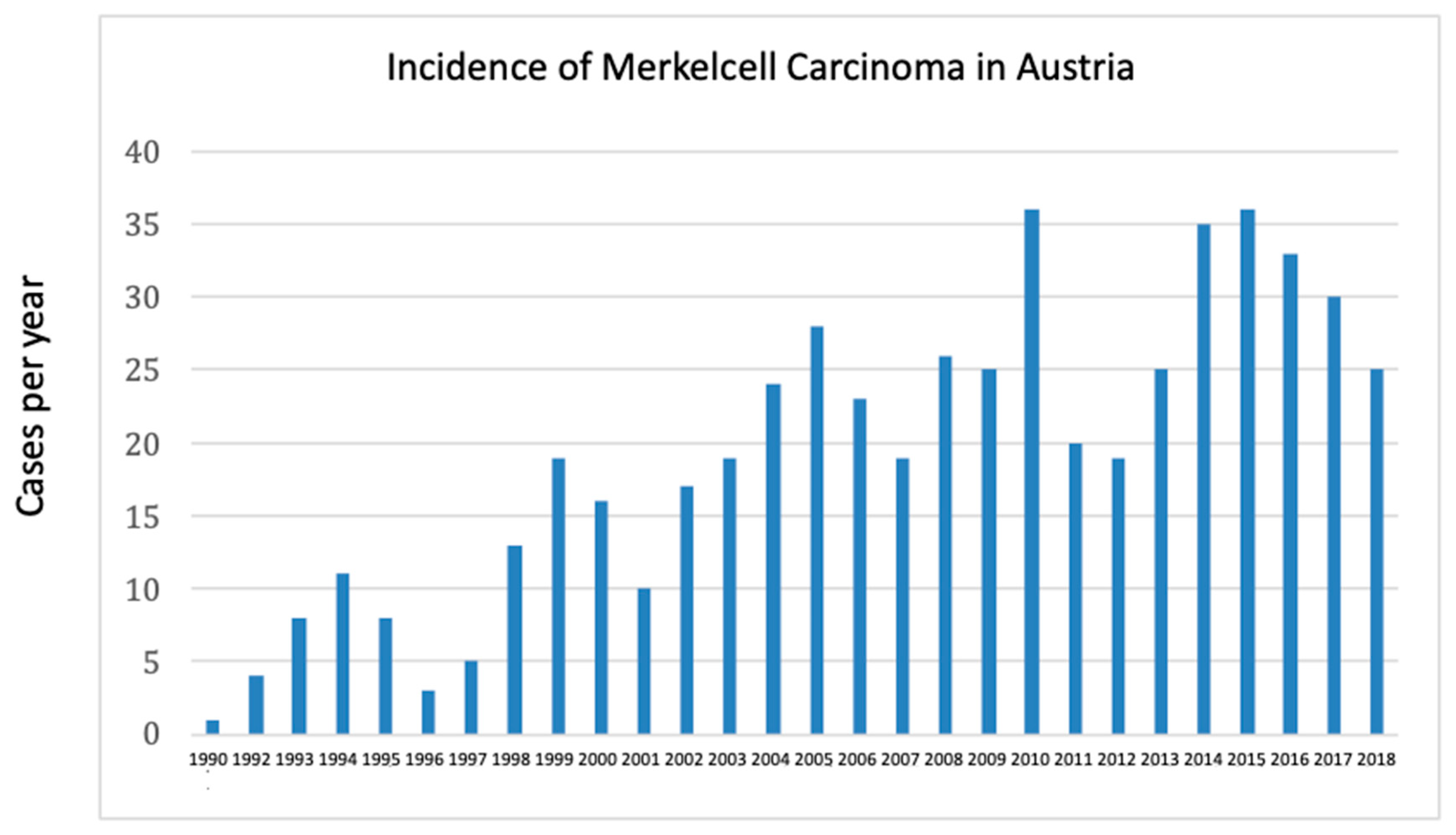

Incidence rates were adjusted to the Austrian population and are shown in the

Figure 2. The median incidence of disease per 100.000 was 0.234, with a noticeable uprising linear trend in the observation period (

Figure 2a and b).

Comparison analysis between West- and East-Austria showed significant differences (

Figure 2b) in terms of overall incidence rates. In detail, the mean incidence of MCC in West-Austria was 0.269 ± 0.04 compared to 0.180 ± 0.02 in East-Austria (p=0.005) between1990 and 2018.

UV Data

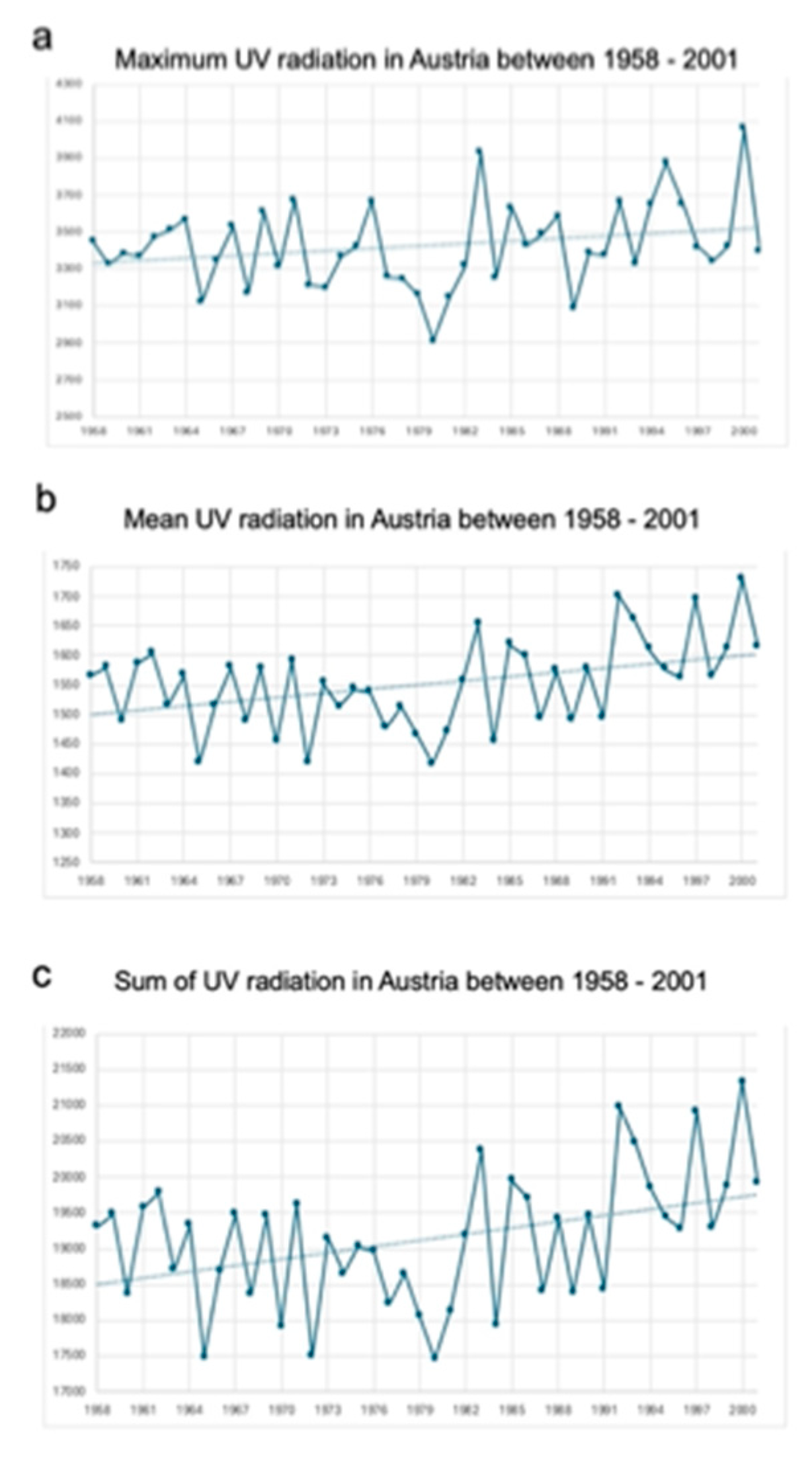

Maximum, mean, and sum of UV values in Austria are presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 3. UV values were significantly increasing over time and there is also a difference between the western and eastern parts of Austria.

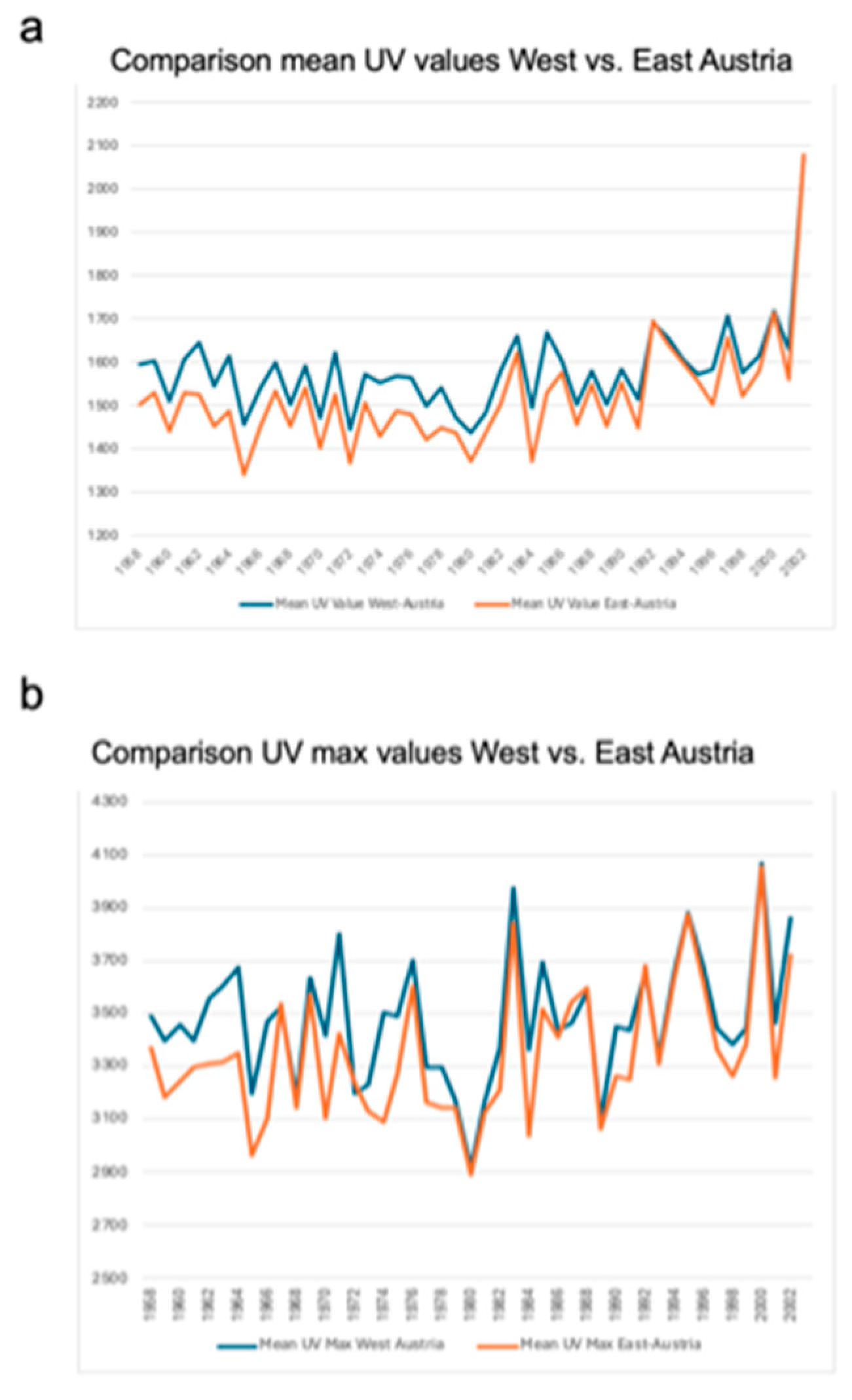

In particular, graphical illustration shows a noticeable upward trend for all three UV variables between 1958 and 2001. Comparison analyses showed significant differences in the UV radiation load between west and east Austria. Mean UV radiation load (1581.59 ± 101.76 vs. 1517.84 ± 119.35; p < 0.001) was significantly higher in the western part of Austria compared to the eastern part as well as the maximum UV values (3478.24 ± 234.03 vs. 3347.25 ± 252.60; p < 0.001) (

Figure 4 and

Table 3).

Correlation Analysis Between UV Radiation and Incidence

Overall, the national incidence rate correlated significantly with mean UV radiation load (p=0.033, r= 0.503) as well as the sum of UV radiation (p=0.033, r= 0.503) countrywide. No significant correlation was detected between incidence and maximal UV radiation (p=0.172, r= 0.337). Moreover, separate subanalysis for West and East Austria showed no significant correlation in terms of incidence and UV radiation load.

Survival

Univariate and multivariate analyzes were done using Cox-regression. Clinical factors like age, UV exposure, presence of nodal involvement, site of the tumor and geographic data were included. None of the parameters had an influence on survival and data on disease-specific survival were not available (Data not shown).

Discussion

This study presents for the first time epidemiological and long-time observational data on MCC and UV radiation in Austria. Analyzes showed that particularly elderly people are confronted with this disease and that the head/neck region and the upper extremities are the most common localization of MCC. These data are in concordance with other publications from Scandinavia, Finland, Netherlands and Australia [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Except to one single epidemiological study from the USA, female patients are more prone to develop MCC than males [

11]. Based on our data and current literature, we could confirm this observation and we only can speculate that this fact may be linked to a higher life expectancy rate of females compared to male patients [

12]. Although tumor size was not available through the ANCR, we could observe that at the point of diagnosis most carcinomas were high stage tumors with presences of nodal and even distant metastatic disease. This finding is new and compared to Scandinavian data, tumor stage was significantly advanced in our Austrian population [

7].

One of the key findings of our study is that, after population adjusting, we could clearly show that MCC is rising from the early 1990ies to the second decade of the 2000s. To adjust our incidence data, we used primarily the Austrian population [

12]. But since our data are in clear concordance with other epidemiological publications [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], we assume our data being accurate regarding this point. Moreover, when comparing to the most recently published study of Zaar et al. [

7], we could observe that the incidence is significantly higher in Austria compared to Sweden. In particular, the incidence rate in Sweden was ranging for both sexes between 0.11 to 0.19 whereas in Austria we had an increase of 0.04 to 3.45. As stated shortly in the previous paragraph, we also observed that Austrian patients presented with more nodal involvement (44%) and distant metastatic disease (14%), whereas in the Swedish study only 10% had lymph node involvement and 3% distant metastatic disease. We do not have data on patients’ distribution with nodal and metastatic disease within Austrian counties, but there is a certain possibility that patients from remote regions wait longer to see a physician compared to patients from urban areas.

Secondly, we also could observe how knowledge in medicine evolves. In particular, since the first description of the specific antigen for MCC CK19 by Moll and colleagues in 1984, we could observe simultaneously a first rise in MCC in the early 1990-ties. Looking at the incidence a decade later, in 1994, the number increased to 7 patients and two more decades later in 2010 the number of MCC has tripled per year (

Figure 5).

Now it is of course difficult to distinguish whether it is a true increase of incidence of disease or is it a result of gaining more knowledge regarding the use of CK19 [

13] as a specific diagnostic immunohistochemical tool in skin pathology and particularly MCC. This is for sure a key point of discussion that can, in our point of view, only be resolved by gaining more information from other institutions and countries worldwide. Furthermore, by looking at the timeline of MCC incidence, we also could see that first description of the MCPyV in 2008 [

14] was also, in a kind of, linked to an increase of diagnosis. Someone can also argue that a rise of incidences may also be attributed by a higher awareness of physicians, but the simultaneous increase of UV radiation may underline the importance of carcinogenesis and MCC [

15,

16].

To further discuss the influence of UV radiation on carcinogenesis in general, our data showed for the first time that the UV radiation was significantly different between the Western and Eastern part of Austria. Although Austria is among the smaller countries in Europe it is nevertheless a very interesting observation. However, although mean and sum UV values correlated significantly to the MCC incidence, we could not find any correlation between high UV exposure in West Austria and development of MCC. A hypothesis for no correlation might be that the sum and not maximum values of UV exposure is linked to carcinogenesis. This is specifically true for basalcell carcinoma but to our knowledge this is not shown for MCC yet.

Nevertheless, besides the new data we could present, this study has flaws. In particular, we were not able to gain tumor size and the disease-specific survival data. This problem is contributed to lack of IT structures and subsequently of data mining during the 1980-ies until the 2000-ies and should be resolved by new setting up new databases. Secondly, we were not able to retrieve MCPyV status of MCC patients that were diagnosed between 2010 and 2018. This issue is for sure the next key target in diagnosis and particularly for therapy of MCC patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study shows that MCC is a rare disease in Austria, but the incidence is significantly increasing compared to other countries. This study supports the finding that high UV exposure is linked to an increased incidence of MCCs. As a consequence, there is a strong need for further informational campaigns to increase awareness of MCC among clinicians and the general population.

Author Contributions

BE: conceptualized the study, and wrote the manuscript. AS, FS, SJ, SG and RS analyzed the data and contributed to the interpretation of the results. MCG conceptualized the study, led the project and contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study obtained no financial support from third party funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (1892/2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived as only anonymized registry data were used.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Toker, C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1972, 105, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erovic, I.; Erovic, B.M. Merkel cell carcinoma: The past, the present, and the future. J Skin Cancer. 2013, 2013, 929364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haymerle, G.; Janik, S.; Fochtmann, A.; et al. Expression of Merkelcell polyomavirus (MCPyV) large T-antigen in Merkel cell carcinoma lymph node metastases predicts poor outcome. PLoS ONE. 2017, 12, e0180426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erovic, B.M.; Al Habeeb, A.; Harris, L.; Goldstein, D.P.; Ghazarian, D.; Irish, J.C. Significant overexpression of the Merkelcell polyomavirus (MCPyV) large T antigen in Merkel cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2013, 35, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haymerle, G.; Fochtmann, A.; Kunstfeld, R.; Pammer, J.; Erovic, B.M. Merkelcell carcinoma: Overall survival after open biopsy versus wide local excision. Head Neck. 2016, E1014–E1018. [Google Scholar]

- Vanicek, K.; Frei, T.; Lyinska, Z.; Schmalwieser, A. UV Index for the public. Publication of the European Communities, Brussels, Belgium. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zaar, O.; Gillstedt, M.; Lindelöf, B.; Wennberg-Larkö, A.M.; Paoli, J. Merkel cell carcinoma incidence is increasing in Sweden. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016, 30, 1708–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukko, H.; Bohling, T.; Koljonen, V.; et al. Merkel cell carcinoma - a population-based epidemiological study in Finland with a clinical series of 181 cases. Eur J Cancer. 2012, 48, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichgelt, B.A.; Visser, O. Epidemiology and survival of Merkel cell carcinoma in the Netherlands. A population-based study of 808 cases in 1993-2007. Eur J Cancer. 2011, 47, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Youlden, D.R.; Soyer, H.P.; Youl, P.H.; Fritschi, L.; Baade, P.D. Incidence and survival for Merkel cell carcinoma in Queensland, Australia, 1993–2010. JAMA Dermatol. 2014, 150, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaae, J.; Hansen, A.V.; Biggar, R.J.; et al. Merkelcell carcinoma: Incidence, mortality, and risk of other cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010, 102, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office for National Statistics. Revised European Standard Population 2013 (2013 ESP). 2013. Available online: http://www.ons.gov.uk.

- Moll, R.; Moll, I.; Franke, W.W. Identification of Merkel cells in human skin by specific cytokeratin antibodies: Changes of cell density and distribution in fetal and adult plantar epidermis. Differentiation. 1984, 28, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Shuda, M.; Chang, Y.; Moore, P.S. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008, 319, 1096–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koepke, P.; De Backer, H.; Bais, A.; et al. EUR 23338 - COST Action 726 - Modelling solar UV radiation in the past: Comparison of algorithms and input data. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Blumthaler, M. UV Monitoring for Public Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018, 11, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).