1. Introduction

The local inflammatory response observed during lung resection surgery (LRS) also affects systemically when the proinflammatory mediators reach the bloodstream and eventually peripheral organs, including the liver [

1]. This is exacerbated when one lung ventilation (OLV) is required [

2].

The OLV is necessary to perform certain surgical procedures in thoracic surgery, it has an impact at the pulmonary level but also produces a systemic inflammatory response by releasing proinflammatory mediators into the bloodstream. OLV cause potential damage to the ventilated lung (biotrauma) and also due to ischemia/reperfusion (IR) and surgical manipulation in the intervened lung [

3].

Proinflammatory substances cause damage related to oxidative stress in lungs and increase the levels of inflammatory markers in plasma, such as IL-1, IL-6 and TNFα [

4,

5]

.

Clinical manifestations of acute liver damage are not frequent in LRS, however, liver plays an important role in the inflammatory systemic response and is specially sensible to IR [

6,

7]. Impaired liver clearance of pathogenic microorganisms and toxins from the circulation, and the release of hepatic cytokines can have important systemic effects and contribute to the pathogenesis of multi-organ failure. Therefore, the ARDS that can occur in up to 2% after LRS is considered a multi-organ dysfunction secondary to a systemic response [

8].

This approach fits within the framework of precision and personalized medicine, where perioperative strategies are tailored not only to the surgical procedure but also to the individual’s inflammatory susceptibility. Identifying modulatory drugs such as lidocaine may help develop patient-specific anesthetic regimens aimed at reducing organ damage and improving outcomes

Being able to modulate the systemic inflammatory response could prevent/reduce the damage caused by it and numerous therapeutic strategies have been studied [

9]. Lidocaine is a local anesthetic that in addition to its classics properties, has anti-inflammatory properties and is capable of modulating the inflammatory response [

10]. This quality has been observed at different levels of the inflammatory cascade, which has serious consequences in the liver, where different types of lesions are produced, such as intracellular and interstitial edema and necrosis of hepatocytes [

11].

The anti-inflammatory effect of lidocaine during surgical interventions is well known [

12,

13] [

14,

15]. Previously, our group showed that lidocaine attenuates the lung inflammatory response in an experimental model of LRS [

16], but there are no previous studies that analyze the molecular mechanisms by which lidocaine could act on the inflammatory response measured in the liver during LRS [

17]

.

Therefore, we hypothesized that lidocaine could act at hepatic level by attenuating the inflammatory response that occurs during LRS.

The main goal of our study was to investigate the effect of intravenous lidocaine administration during LRS on liver inflammatory response and to analyze the molecular mechanisms that would provide such benefits.

2. Materials and Methods

Experimental, randomized and blinded study. The study was carried out with the authorization of the Committees of Investigation (CI) and of Ethics in Animal Experimentation (CEEA) of the General Universitary Hospital Gregorio Marañón (HGUGM). The project will be arranged in the legal regulation and, especially, in the Law 32/2007, of November the 7th, for the care of the animals in his exploitation, transport, experimentation and sacrifice, and in the Royal decree 53/2013, of February the 1st, by which there are established the basic applicable procedure for the protection of the animals used in experimentation and other scientific ends, included teaching. All the experiments were performed according to European and Spanish laws for the caring of experimental animals.

2.1. Experimental Model

A total of 18 mini pigs, male and female, with an average weight between 30-40 kg underwent left thoracotomy for caudal lobectomy using one lung ventilation (OLV).

The 18 specimens were equally and randomly divided into three groups: lidocaine group (LIDO), control group (CONTROL), and sham group (SHAM). In the LIDO group lidocaine was administered as an initial bolus of 1.5 mg/kg followed by a continuous infusion of 1.5 mg/kg/h until the end of the surgery, in the CONTROL group the animals received the same volume of 0.9% saline solution. In the SHAM group, no OLV or lobectomy was performed, only thoracotomy and two lung ventilation.

The same samples (blood, lung and liver samples) were taken for analysis in all groups at baseline, 120 minutes after OLV, 60 minutes after TLV and 24h after surgery.

2.2. Anesthesia Protocol

A standardized anesthetic protocol was used to treat all animals in the same way.

An 18-hour fasting period was performed and only water was allowed freely up to two hours before the procedure.

Premedication was administered with intramuscular ketamine 10mg/kg (Ketolar®, Parke Davis, Pfizer, Dublin, Ireland), then the animal was transferred to the operating table and placed in the supine position with continuous monitoring of the electrocardiographic and pulsioximetry. Anesthetic induction was administered with fentanyl 3 mcg/kg (Fentanest, Kern Pharmaceuticals, Houston, TX), propofol 1% 4 mg/kg (Diprivan, AstraZeneca, Macclesfield, Cheshire, UK), and atracurium 0.6 mg/kg (Tracrium, Glaxo Smith Kline, Brentford, UK). Antibiotic prophylaxis was administred with benzathine penicillin (600,000 IU IM).

Maintenance was performed with continuous perfusion of propofol 2% (Diprivan®, AstraZeneca) and boluses of fentanyl and atracurium as required. Maintenance fluid therapy was administered with crystalloids, ringer lactate (Hartmann Braun, Barcelona) 5-6ml/kg/h.

Following induction, orotracheal intubation was performed with a Nº 6.5 cuff endotracheal tube positioned 2-3 cm above the carina to perform two lung ventilation (TLV). The correct position of the tube is checked by a fiberoptic bronchoscope (3.7mm flexible Karl-Storz fiberoptic bronchoscope, with working channel).

The IOT tube is connected to the respirator and volume-controlled mechanical ventilation was performed with protective lung ventilation parameters: FiO2 60%, tidal volume (TV) of 8 mL/kg, 6 mL/kg during OLV, peak pressure <30 cmH2O, PEEP of 5 cm H2O, inspiration-expiration ratio of 1:2 and respiratory rate 12-15 breath per minute to maintain normocapnia.

Respiratory parameters, capnography, peak pressure, mean pressure, and lung compliance were monitored. When OLV was required (in LIDO and CONTROL group) the proximal part of the IOT tube was connected with a second Murphy tube number 8.5-9 and advanced to the main right bronchus under fiberoptic bronchoscope vision.

When the procedure was completed, the animal was awakened and extubated. During the postoperative period, ketorolac 30 mg (Droal®, Vita S.A., La Paz, Bolivia) and dexketoprofen for pain were prescribed, and free access to water was allowed. At 24 hours postoperatively, we performed another anesthesic induction in the same conditions in order to collect samples, after that the animal was euthanized.

2.3. Surgical Protocol

The porcine model was placed in the right lateral decubitus position and a left thoracotomy was performed. The right femoral artery and vein were cannulated. A venous catheter and a PiCCO thermodilution catheter (PV2014L16 small adult femoral artery with a 4 French diameter and a length of 160 mm) were introduced through the arterial line.

One-lung ventilation (OLV) was started in the LIDO and CONTROL group and a caudal lobectomy was performed. After 120 minutes of one-lung ventilation (OLV120), TLV was restored for 60 minutes (TLV60). After performing all the determinations, and once TLV ventilation was restarted the expansion of the left cranial lobe was verified, also the tightness of the bronchial suture was checked to assure that there were no leaks and after that proceeded to close the thoracotomy by planes, leaving an intrapleural drainage tube that was connected to a unidirectional flow system (Heimlich valve).

After waking up the animal and 24 hours after the intervention, it was transferred back to the operating room and general anesthesia was performed again, following the same anesthetic protocol described above. Next, samples were collected: gasometric and hemodynamic study, blood extraction for biochemical studies, liver biopsy, and biopsies from the left cranial lobe and the mediastinal lobe.

To facilitate taking liver biopsies, prior to placing the animal in lateral decubitus, a subxiphoid median laparotomy of about 5 or 6 cm was performed.

Once we have the necessary samples, the porcine model was euthanized.

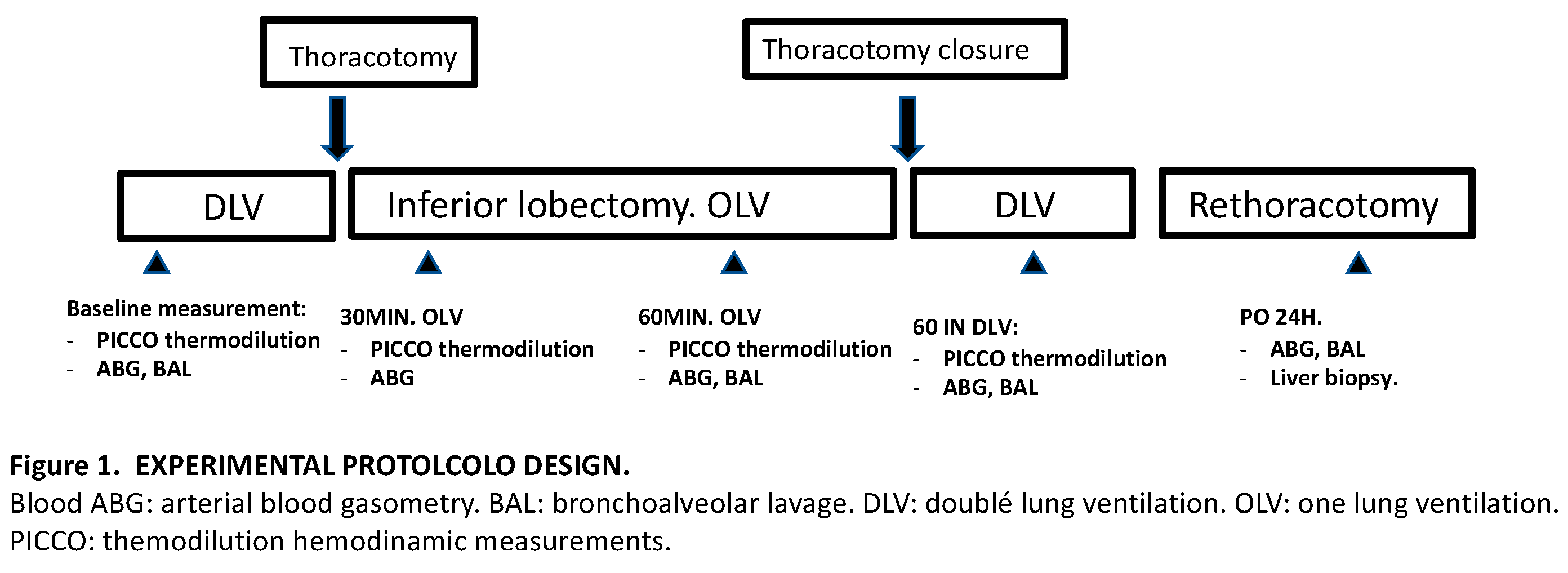

Experimental protocol design (

Figure 1):

Hemodynamic data were collected through the PiCCO monitor and transpulmonary thermodilution was performed periodically. Arterial blood gases were performed at different times during the procedure: baseline, 30 minutes of one-lung ventilation, 120 minutes of one-lung ventilation, 60 minutes after restarting two-lung ventilation, and 24 hours. after lobectomy.

BAL was performed at baseline, at 120 minutes of VUN, at 60 minutes after restarting TLV, and at 24 hours after lobectomy. The recovered liquid was centrifuged and frozen at -20°C until used.

2.4. Liver Samples

During the experiment, one liver sample was taken from each experimental animal, to carry out the pertinent biochemical studies. The liver biopsy was taken 24 hours after the lobectomy.

Each sample was placed in a cryotube, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored in a freezer ( -80ºC) until their subsequent analysis.

3. Determination of Biochemical Markers

3.1. Proinflammatory Mediators. Cytokines

Levels of TNF alfa, IL-1, IL-10 and MCP1 were measured in liver biopsies samples using porcine specific ELISA kits (Cusabio Biotech Co. Wuhan Hubei, China and MyBiosource, San Diego, USA), following manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, standards and samples were pipetted into pre-coated wells and any of the investigated protein present in the samples was bound by the immobilized antibody. After removing any unbound substances, a biotin-conjugated antibody specific for the investigated protein was added to the well. After washing, avidin conjugated horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was added to the wells. Following a wash to remove any unbound avidin-enzyme reagent, a substrate solution was added to the wells. After 10 min, the color development was stopped and the intensity of the color was measured at 450 nm. The intra-assay precision was CV%<8% and the inter-assay precision was CV%<10%.

3.2. Nitric Oxide

It was measured as content of nitrite + nitrate (NO2 - + NO3-), by means of the Griess reaction as nitrite ion (NO2−) concentration after nitrate (NO3) reduction to NO2−. Briefly, after incubation of the plasma with Escherichia coli NO3 reductase and NADPH+ (37 °C, 30 min), 300 µl of Griess reagent (0.5% naphthylenediamine dihydrochloride, 5% sulfonilamide, 25% phosphoric acid (H3PO4)) (Sigma-Aldrich, MI, USA) was added. The reaction was performed at 22 °C for 20 min, and the absorbance at 546 nm was measured, using sodium nitrite (NaNO2) solution as standard.

The measured signal was linear from 1 to 150 mM. (r= 0.994, p< 0.001, n=5). The detection threshold was 2 μM. The reproducibility of the experiment was evaluated in three independent experiments and each repeated three times. The average intra-assay variation calculated was less than 5%.

3.3. Messenger RNA Expression (mcp-1, il-1, tnf-α, il-10, nf-κb, inos)

It was performed using the reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) technique.

RNA was isolated from porcine liver samples using the method described by Chomczynski [

18] using the TRI reagent kit (Molecular Research Center, Inc, Cincinnati, OH, USA), following the manufacturer’s. RNA purity was measured with 1 agarose gel electrophoresis, and RNA concentrations and ratio 260/280 was determined by spectrophometry BioDrop™ (Fisher scientific, MA, USA).

Reverse transcription of 2 mg of RNA for cDNA synthesis was performed using the StaRT Reverse Transcription Kit (AnyGenes, Paris, France). qRT-PCR was performed using 7500 Fast Real Time PCR System thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, MA, USA) with the TB Green® Ex Taq™ (Tli RNase H Plus) (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) and 300 nM concentrations of specific validated primers (AnyGenes, Paris, France). The qPCR amplification cycles were a 95 °C 10 min cycle, followed by 45 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s and at 60 °C for 30 s and finally melting curve analysis, following the recommendations of the manufacturer (95 °C for 10 s, 65 °C for 30 s and 95 °C for 0 s).

Amplification of 18S mRNA was used as a loading control for each sample. The gene expression level was analyzed in triplicate for each sample. Relative changes in mRNA expression were calculated using the 2-∆∆CT method [

19].

3.4. Protein Expression (tnf-α, il-1β, il-10, bad, bax, bak, bcl-2, mcl-1, inos, enos and nf-κb) and Variables Related to Apoptosis (Puma, Khloto)

It was performed by Western blot using specific anti-TNFa (Endogen), anti-IL1b and anti-IL6 (Bio Genesis), anti-nitric oxide Synthase I, anti-nitric oxide Synthase II, anti-nitric oxide Synthase III, (Chemicon International, Inc.), anti-NFkappaB (Endogen), and anti-IkappaB (Endogen).

Western blotting was used to measure levels of TNF-α, IL-1b, IL-6, iNOS, eNOS, Nf-κB and iκBb. Briefly, liver samples, after homogenization with modified RIPA lysis buffer (PBS, Igepal, Sodium deoxycholate (D5670-5G), 10% SDS, PMSF, 0.5M EDTA and 100 mM EGTA) to which protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma #P-2714), PMSF (#P7626, 1mM), sodium orthovanadate (#S6506, 2mM) and sodium pyrophosphate (#S6422, 20mM) were added, were sonicated and boiled for 10 min at 100 °C in the ratio 1:1 with gel-loading buffer (100 mmol/L TrisHCl [pH 6.8], 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, bromophenol blue 0.1, 200 mmol/L dithiothreitol).

Total protein equivalents (25 μg) for each sample were separated by SDS-PAGE by using 10% Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ Precast acrylamide Gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA) and were transferred onto a PVDF membrane using Trans-Blot® Turbo™ Transfer System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA).

The membrane was immediately placed into blocking buffer containing 5% non-fat milk in 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.01% Tween-20. The blot was allowed to block at 37 °C for 1 h. The membrane was incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:1000) for 12 h at 4 °C, followed by incubation with a goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA) (1:7000).

Protein detection was performed using the Clarity Western ECL Substrate assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA) and ECL Plus (Amersham Life Science Inc., Bucking-hamshire, UK) by chemiluminescence with the BioRad® ChemiDoc MP Imaging System to determine the relative optical densities. Pre-stained protein markers were used for molecular weight determinations. Housekeeping gene GAPDH was used as loading control (1:5000) (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Proteins were quantified using BioRad® Image Lab software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA).

3.5. Statistical Analysis

The experiment data was collected in an Access database designed for the project. To determine if the data followed a normal distribution, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used. To determine whether the results of the different experimental groups were homogeneous at baseline, the ANOVA-F test was performed. To determine whether the differences between the means of the different groups were statistically significant, a repeated measures ANOVA was performed. After rejecting the Null Hypothesis of equality of means by means of ANOVA, the Tukey test was used to compare means between different experiments. All data are expressed as mean ± the standard deviation of the mean. The analysis of results was carried out with the statistical package SPSS 23.

4. Results

4.1. General, Hemodynamic and Gasometric Parameters

Our results showed high stability in gasometric and hemodynamic parameters between both, CONTROL and LIDO group.

No differences were observed between the three groups related to animal weight or duration of the procedure.

4.2. Liver Biopsy

We perform all our measurements in the liver biopsy we take in each porcine model at the 24h time point.

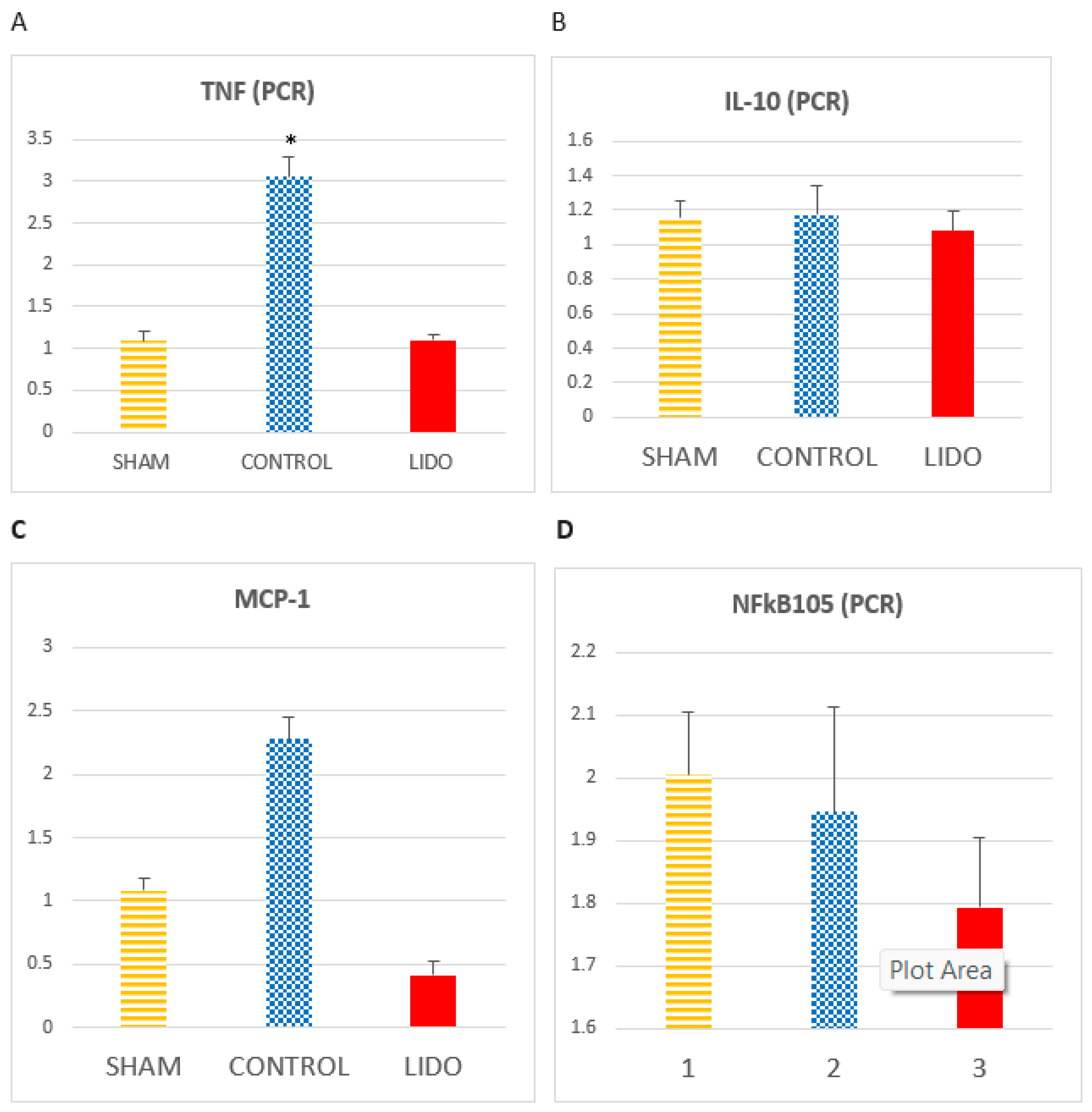

4.3. Inflammatory Markers Analyzed by PCR in Liver

There is an increase in TNF in the CON group compared to LIDO (P<0.001) and SHAM (p<0.001). The increase in the LIDO group with respect to SHAM is not significant (p=0.526).

We observed how the IL-1 levels increase in the CON group compared to the LIDO group (p=0.008) and the SHAM group (p=0.004). There is an increase in IL-1 in the LIDO group compared to the SHAM group (P=0.003). The results of TNF and IL-1 were similar when the measurement was performed with the W-H technique.

MCP1 in the LIDO group presents a significantly lower value than in the SHAM (p=0.003) and CONTROL (p=0.004) groups. MCP1 in the CONTROL group is higher than in the SHAM (p=0.078).

The IL-10 values are also decreased, although not significantly, in the LIDO group compared to the SHAM and CONTROL group (ANOVA: p=0.748).

NFkB in the LIDO group significantly decreased in the analysis performed at 24h compared to the SHAM and CONTROL group (ANOVA p=0.749).

Figure 2.

Marcadores inflamatorios medidos por PCR en biopsia hepática. Bar graphs show the expression inflammatory biomarkers in liver biopsy samples 24 hours after the procedure, and compare the control group (CON) with the lidocaine group (LIDO) and with the SHAM group. (A), TNF-α; (B) IL-10; (C) MCP1; (D) NFKB. *P<0.005 CON grupo vs SHAM group.

Figure 2.

Marcadores inflamatorios medidos por PCR en biopsia hepática. Bar graphs show the expression inflammatory biomarkers in liver biopsy samples 24 hours after the procedure, and compare the control group (CON) with the lidocaine group (LIDO) and with the SHAM group. (A), TNF-α; (B) IL-10; (C) MCP1; (D) NFKB. *P<0.005 CON grupo vs SHAM group.

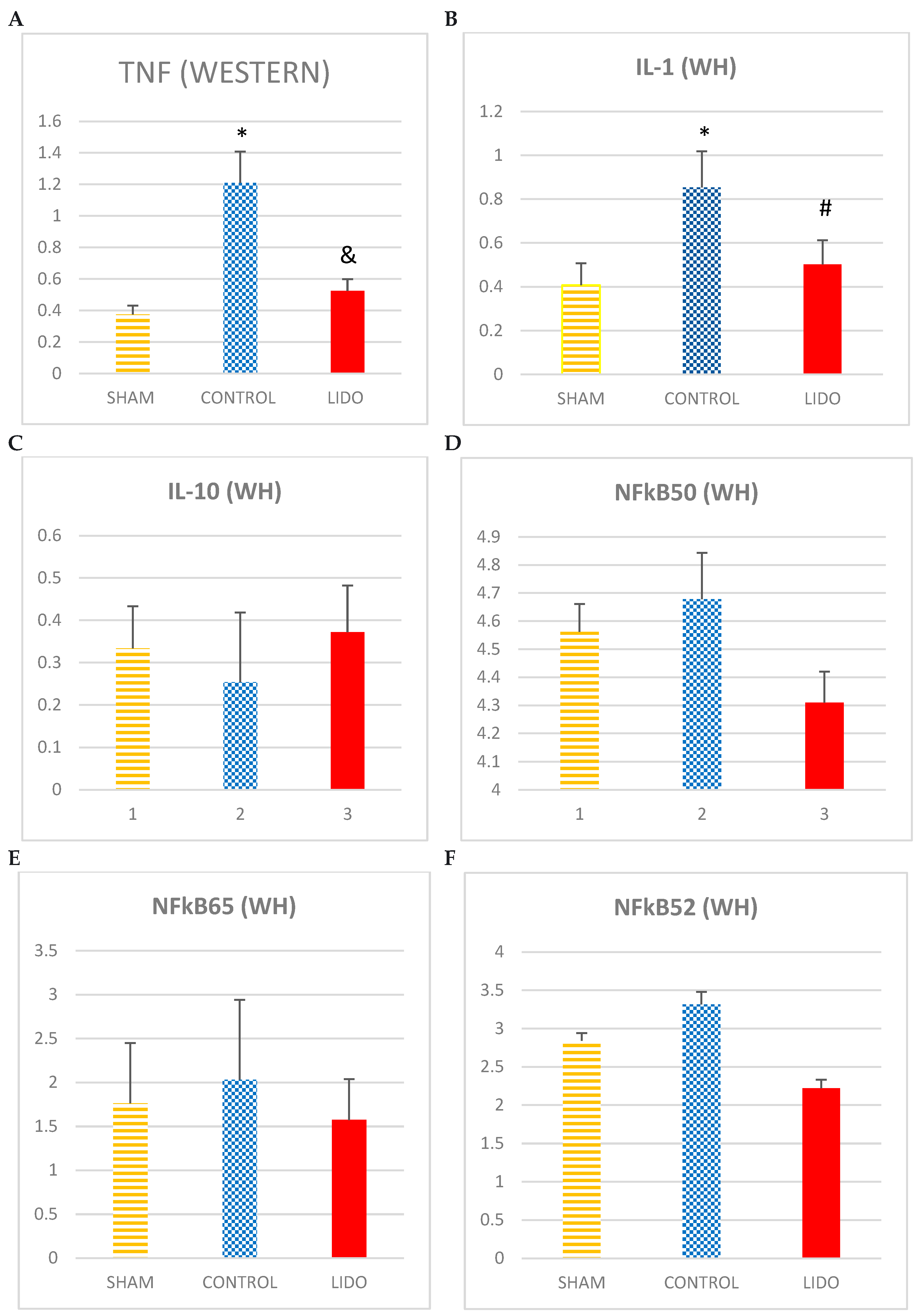

4.4. Inflammatory Markers Analyzed by WB Technique in Liver

The levels of TNF and IL1 increase CONTROL in relation to SHAM and LIDO.

Regarding the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10, the levels are higher in the LIDO group compared to CONTROL and SHAM (ANOVA: p=0.055).

The different proteins of the NFkB family analyzed show an increase in the CONTROL group with respect to the SHAM and LIDO group: NFkB105 (ANOVA: p=0.749) NFkB65 (ANOVA: p= 0.522) NFkB50 (ANOVA: p=0.749).

The groups that underwent OLV surgery showed lower IkBb expression than the SHAM group. In addition, the values in the LIDO group were lower than in the CON group (p=0.006).

Figure 3.

Marcadores inflamatorios medidos por WB en biopsia hepática. Bar graphs show the expression inflammatory biomarkers in liver biopsy samples 24 hours after the procedure, and compare the control group (CON) with the lidocaine group (LIDO) and with the SHAM group. *P < 0.005 CON group versus SHAM group; #P < 0.005 LIDO group versus SHAM group; & P < 0.005 LIDO group versus CON group. (A), TNF-α; (B) IL-1; (C) IL-10; (D) NFkB50 (E) NFkB65 (F) NFkB52 (G)IkBa (H)IkBb. TNF = tumor necrosis factor; IL = interleukin; NFkB = nuclear factor kappa B.

Figure 3.

Marcadores inflamatorios medidos por WB en biopsia hepática. Bar graphs show the expression inflammatory biomarkers in liver biopsy samples 24 hours after the procedure, and compare the control group (CON) with the lidocaine group (LIDO) and with the SHAM group. *P < 0.005 CON group versus SHAM group; #P < 0.005 LIDO group versus SHAM group; & P < 0.005 LIDO group versus CON group. (A), TNF-α; (B) IL-1; (C) IL-10; (D) NFkB50 (E) NFkB65 (F) NFkB52 (G)IkBa (H)IkBb. TNF = tumor necrosis factor; IL = interleukin; NFkB = nuclear factor kappa B.

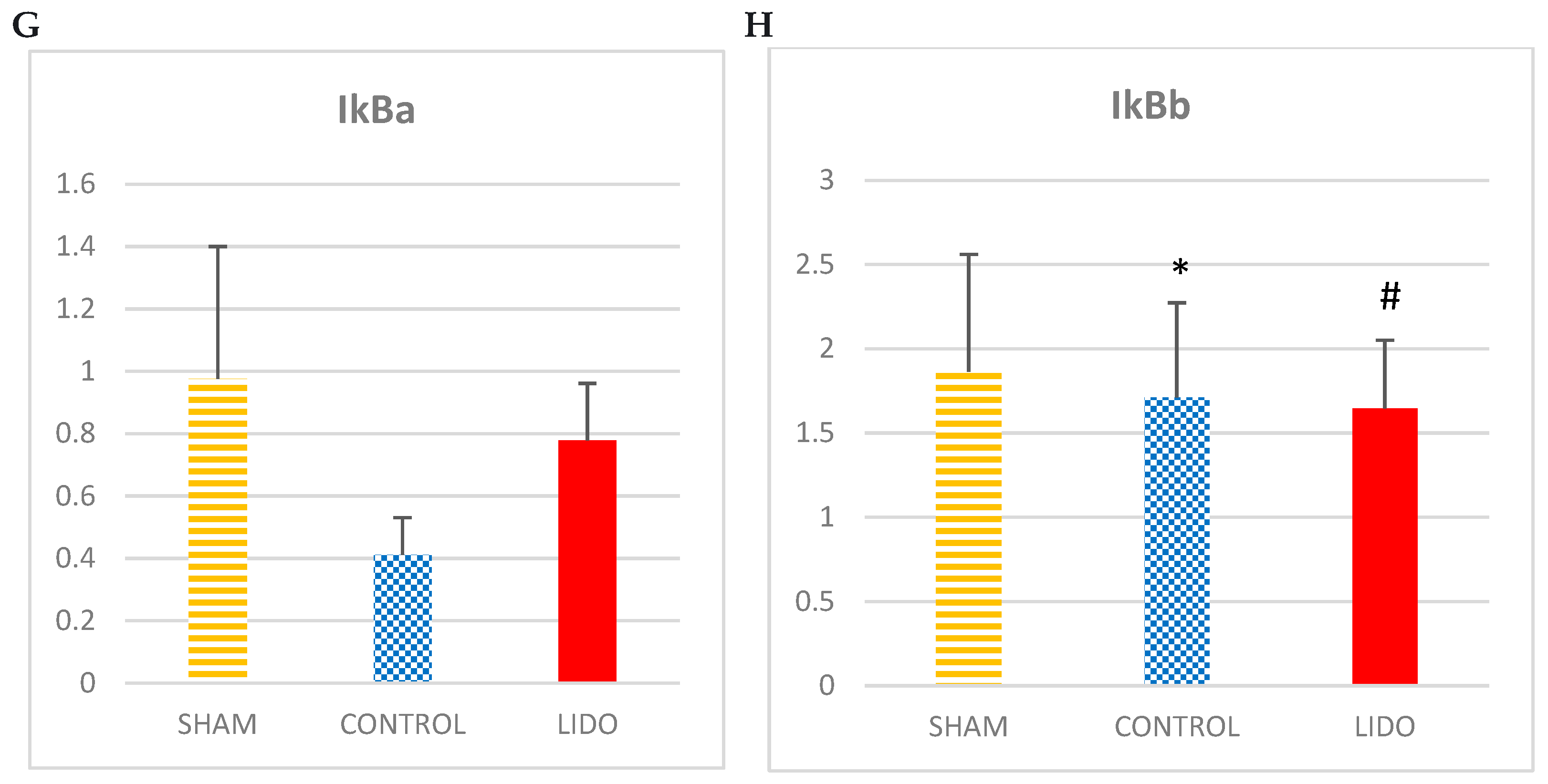

4.5. Nitric Oxide Metabolism

The inducible nitric oxide synthase enzyme (iNOS) is increased in the CONTROL and LIDO groups related to SHAM (P=0.01 and p=0.005 respectively4). In addition, the CON group presented significantly higher levels than the LIDO group (p=0.004). These results were similar when the measurement was performed with the W-H technique. In the case of the endothelial nitric oxide (eNOS) enzyme, eNOS showed lower expression in the CON and LIDO groups than in the SHAM group (p=0.006 and p=0.001), also having lower values in the CON group compared to the SHAM group. LIDO group (p=0.011). The iNOS/eNOS ratio is significantly higher in the CONTROL group compared to SHAM (p= 0.006) and LIDO (p=0.005).

Figure 4.

Nitric oxide (NO) metabolism. Bar graphs show protein (WB) expressions of nitric oxide metabolism comparing the control group (CON) with the lidocaine group (LIDO) and with the SHAM group. In liver biopsy 24 hours after the procedure. *P < 0.003 CON group versus SHAM group; #P < 0.003 LIDO group versus SHAM group; &P < 0.003 LIDO group versus CON group. (A) Protein expression of eNOS in liver biopsy (B) Protein expression of iNOS in liver biopsy (C) ratio iNOS/eNOS. iNOS: isoforma inducible de NO, eNOS: isoforma endothelial de NO.

Figure 4.

Nitric oxide (NO) metabolism. Bar graphs show protein (WB) expressions of nitric oxide metabolism comparing the control group (CON) with the lidocaine group (LIDO) and with the SHAM group. In liver biopsy 24 hours after the procedure. *P < 0.003 CON group versus SHAM group; #P < 0.003 LIDO group versus SHAM group; &P < 0.003 LIDO group versus CON group. (A) Protein expression of eNOS in liver biopsy (B) Protein expression of iNOS in liver biopsy (C) ratio iNOS/eNOS. iNOS: isoforma inducible de NO, eNOS: isoforma endothelial de NO.

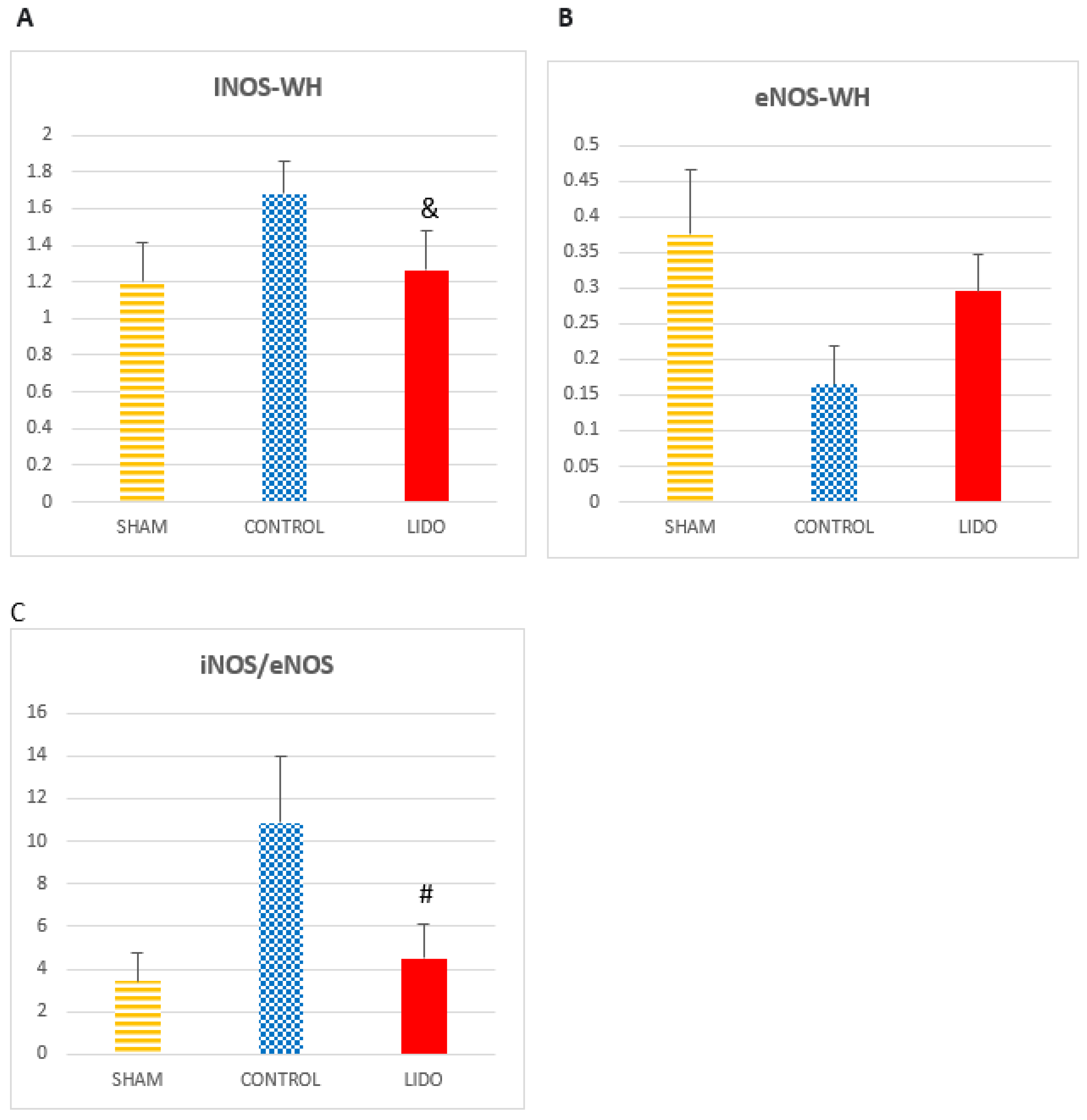

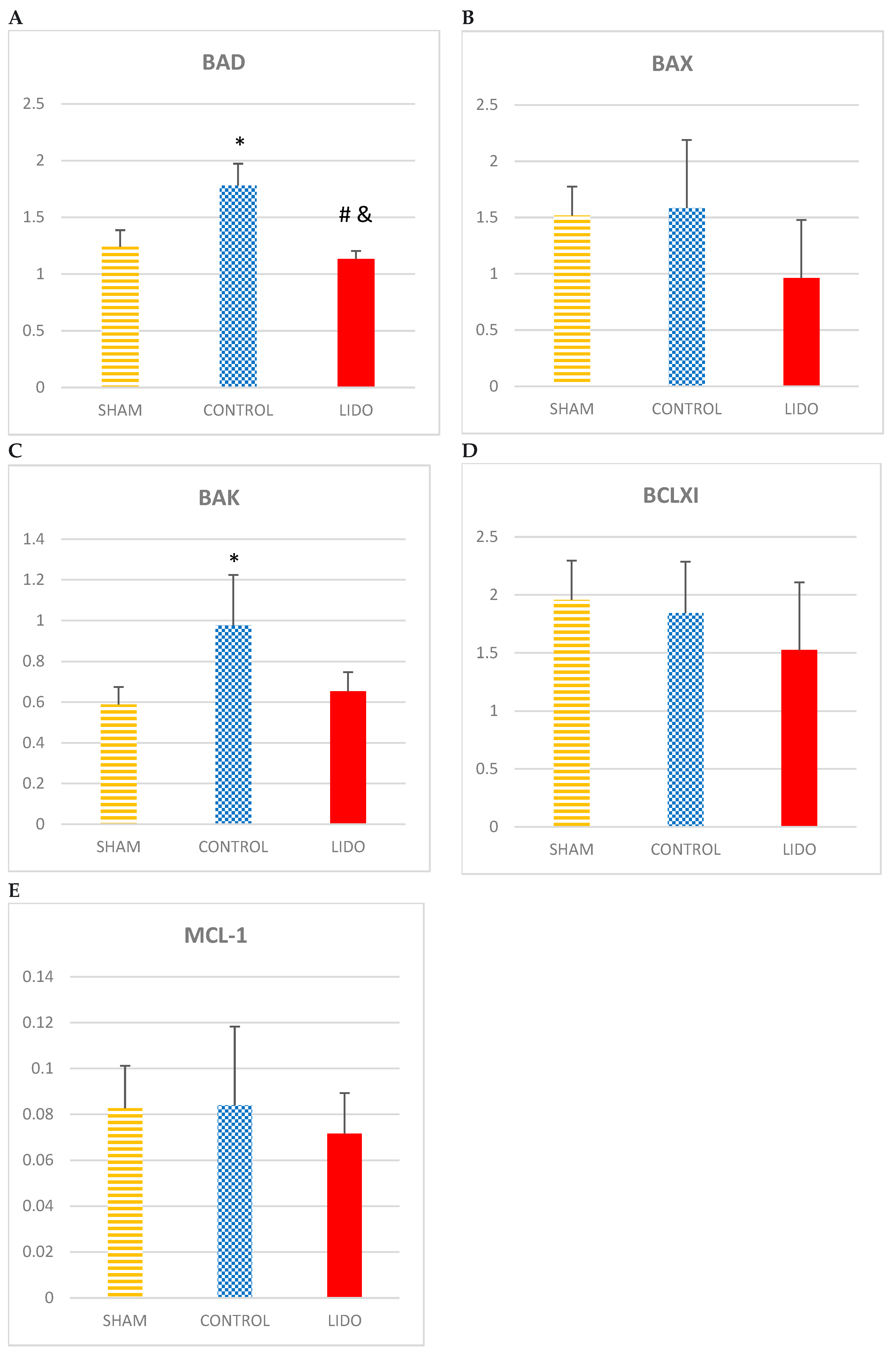

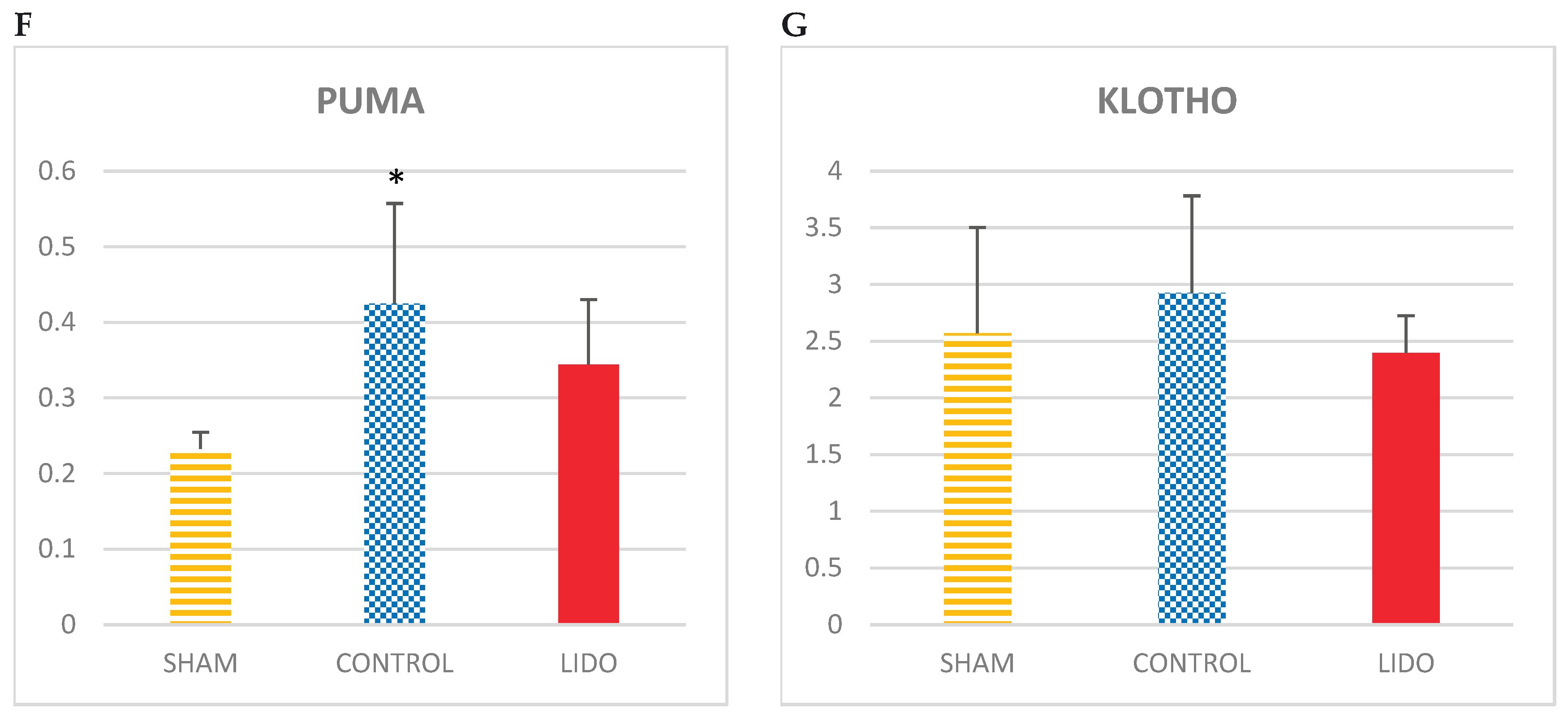

4.6. Apoptosis

If we analyze the apoptosis variables BAD, BAX and BAK, we find that the values obtained are higher in the CONTROL group related to SHAM and LIDO, the measurements of BAD (p=0.004) and BAK (p=0.004) being statistically significant. In the LIDO group, it is observed how the measurements of these variables of apoptosis are lower compared to those obtained in the CONTROL group; BAD (P=0.004), BAK (P=0.007). BAX and BCLXI decreased in the LIDO group compared to the others (ANOVA: p=1) and (ANOVA: p=0.631) respectively.

The MCL1 values are decreased in the LIDO group, although not significantly, compared to SHAM and CONTROL (ANOVA: p=0.631).

Regarding the apoptosis variables PUMA and KLOTHO, the levels of PUMA were significantly elevated in the LIDO and CON groups with respect to the sham (p=0.004 and p=0.007 respectively), with no differences when compared between them.

PUMA levels were significantly elevated in the LIDO and CON groups compared to SHAM (p=0.004 and p=0.007 respectively), with no differences when compared between them.

Regarding KLOTHO levels, there is an increase in the CONTROL group compared to the others (ANOVA: p=0.423). It is in the LIDO group where the lowest value of KLOTHO exists.

Figure 5.

Apoptosis in liver biopsies. Bar graphs show the expression of apoptotic mediators in liver biopsies 24hours after the procedure and compare the control group (CON) with the lidocaine group (LIDO) and with the SHAM group. *P < 0.003 CON group versus SHAM group; #P < 0.003 LIDO group versus SHAM group; &P < 0.003 LIDO group versus CON group. (A), BAD; (B) BAX (C) BAK (D) BCLXI; (E) MCL1 (F) PUMA (G) KLOTHO.

Figure 5.

Apoptosis in liver biopsies. Bar graphs show the expression of apoptotic mediators in liver biopsies 24hours after the procedure and compare the control group (CON) with the lidocaine group (LIDO) and with the SHAM group. *P < 0.003 CON group versus SHAM group; #P < 0.003 LIDO group versus SHAM group; &P < 0.003 LIDO group versus CON group. (A), BAD; (B) BAX (C) BAK (D) BCLXI; (E) MCL1 (F) PUMA (G) KLOTHO.

5. Discussion

Surgery increases proinflammatory cytokines, which leads to a systemic inflammatory response. Our group previously found that lidocaine could prevent the inflammatory damage caused by OLV and attenuate apoptosis [

16]. In this study we verified that the administration of intravenous lidocaine during LRS in a porcine experimental model is associated with an attenuation of the hepatic inflammatory response.

Inflammation is part of the pathogenesis of liver diseases and is regulated by inflammatory mediators [

20]. Kupffer cells, hepatic macrophages, play a determining role in cellular stress and hepatic inflammation, they are considered key cells in the inflammatory process [

21].

The liver plays a determining role in regulating the systemic inflammatory response, being especially sensitive to inflammatory changes (6) (8). Hepatocytes release inflammatory mediators after contact with perioperatory cytokines, amplifying the perioperative inflammatory response [

22].

In our study, we observed the relevance of the biotrauma associated with OLV, animals in the SHAM group (without OLV) developed a lower hepatic inflammatory response. This can be due to mechanical ventilation of the dependent lung and due to the IR process or surgical manipulation in the non-ventilated lung [

23].

Multiple investigations have shown that lidocaine can modulate the perioperative systemic inflammatory response [

14,

15,

24] however, its protective effects on perioperative liver inflammation has not been so well studied.

5.1. Inflammation

Intravenous lidocaine reduce the adhesion of PMN to the endothelium and its migration to the site of inflammation, attenuates vascular inflammation, increases anti-inflammatory cytokines and decreases inflammatory cytokines [

25].

We observed an increase in the production of oxygen radicals and adhesion molecules, and we related it to an increase in interactions between PMN neutrophils and liver vascular endothelial cells that was attenuated by lidocaine administration. The role of MCP-1 as a regulator of the activation, migration, and infiltration of monocytes and macrophages to the site of inflammation is essential to start the inflammatory response(26). In our study, the expression of MCP was attenuated in the LIDO group and we believe this is one of the mechanisms by which lidocaine attenuated liver inflammation. Gallos et al obtained similar results in the prevention of hepatorenal damage in a septic rat model and found that lidocaine administration improved survival, decreased cell adhesion molecules and MCP-1 [

26]. We hypothesize that the action model of lidocaine in lung macrophage PMNs could be extrapolated to liver PMNs, so that its modulatory effect on inflammation could be directly related to the effects that lidocaine has on liver kupffer cells. Reinforcing this hypothesis, in another experimental study it was observed that lidocaine decreased the NFkB signaling pathway in murine macrophages with lipopolysaccharide-induced sepsis [

27]

. NF-KB activation raised the expression of proinflammatory cytokines [

28,

29]

Perioperative liver inflammation increases NFkB and TNFα liver expression [

29]

, there is research supporting that lidocaine blockade of NFkB pathway is dose-dependent [

24,

30]

.

Although in our study we did not show that the administration of lidocaine directly alters this signaling pathway, probably because such high doses were not reach as in the studies previously mentioned, we do appreciate that the cytoplasmic inhibitor of NF-KB (IKB), which blocks the activation and translocation to the nucleus of NF-Kb, was decreased in the control group and did not change in the lidocaine group, so we think that part of the protective effect of lidocaine is due to the maintenance of levels of inhibitors of this pathway, this inhibition is probably related to the effect of NO on this IKB, as has been shown in other previous studies [

28,

31,

32].

5.2. NO

The relationship between the increase in NO concentration in infection, inflammation or sepsis is well known [

33]. After liver injury, hepatocytes express inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) with a consequent increase in NO production, which contributes to hepatocyte injury. iNOS has a proinflammatory action, decreases available NO, and causes oxidative stress [

34,

35]

. Using a murine model of inflammation-related liver damage, Yuang GJ et al found that the increase in liver NO is attributable to a decrease in eNOS and an increase in iNOS, since iNOS knockout mice were protected against such liver injury [

29]

.

Several experimental studies using macrophage cells [

31,

36] have shown how lidocaine inhibits NO production in a dose-dependent manner, apparently by suppressing L-arginine uptake. Furthermore, it inhibits iNOS, possibly involving voltage-gated sodium channels (36).

In other cell cultures [

33] an inhibitory effect of TNF-alpha induced by eNOS activation has also been observed in lung microvascular endothelial cells, which prevents NO production and further propagation of inflammatory signalling [

27]. However, at the hepatic level there is no extensive bibliography in this regard.

In our work, the administration of lidocaine protected against the mismatch between iNOS/eNOS, mainly at the expense of the increase in eNOS that balances the decrease in iNOS in the LIDO group compared to the other groups. There is probably a compensation between both isoforms and that is why NOx metabolism remains stable, demonstrating the hepatic protective effect of lidocaine on NO metabolism. Previously our group showed that lidocaine provided a balance between both isoforms in both lungs [

36]. Huang et al treat macrophages with LPS to allow assessment of the significant inhibitory effects of lidocaine on iNOS transcription, making evident the anti-inflammatory capacity of lidocaine [

36]

. We believe that the fact that lidocaine suppresses the release of NO by activated macrophages could be the key to attenuating liver damage in a context of postoperative inflammatory liver damage.

Perhaps another protective effect of lidocaine observed in our study come from the recognized protection that lidocaine has in IR phenomena, through decreased adhesion and migration of PMNs or inhibition of activated neutrophils [

16,

19].

5.3. Apoptosis

Apoptosis plays an important role in hepatocyte damage. Mechanisms of hepatic apoptosis are complicated by multiple signaling pathways [

32]

. In our study we verified how the balance between pro and anti-apoptotic mediators in liver biopsies from animals that had received lidocaine leaned towards antiapoptosis. Lidocaine has been shown in the majority of the studies to have an antiapoptotic protective role in different inflammatory states [

25,

32,

38,

39]. The specific mechanisms by which lidocaine attenuates apoptosis are not clear, it is known that blocks the extrinsic pathway of apoptosis by decreasing proinflammatory cytokines, especially TNFα, and blocking the intrinsic pathway through the decrease in the bcl-2 and PUMA family proteins. We believe that the decrease in PUMA expression was the major determinant of the antiapoptotic effect observed in our study. PUMA acts as a key mediator of the function of p53 in the cytosol, which is an important transcription factor that activates and regulates apoptosis. Song Cheng et al. suggest that during early liver regeneration, PUMA downregulation may contribute to the suppression of apoptosis and inflammation [

40]. They analyzed how after liver resection surgery, there is a progressive increase in the levels of PUMA, BAX and BCL-XL, which is related to an increase in apoptosis, in Kupffer cells induction and in neutrophils infiltration, as well as a higher number of fulminant hepatitis and mortality.

Our study reinforces the concept that perioperative modulation of inflammation with intravenous lidocaine could be integrated into personalized anesthesia protocols. By identifying patients with higher risk of systemic inflammatory or hepatic injury—based on biomarkers such as NFkB activation or MCP-1 levels—clinicians may tailor lidocaine use as a precision medicine strategy