Submitted:

31 August 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

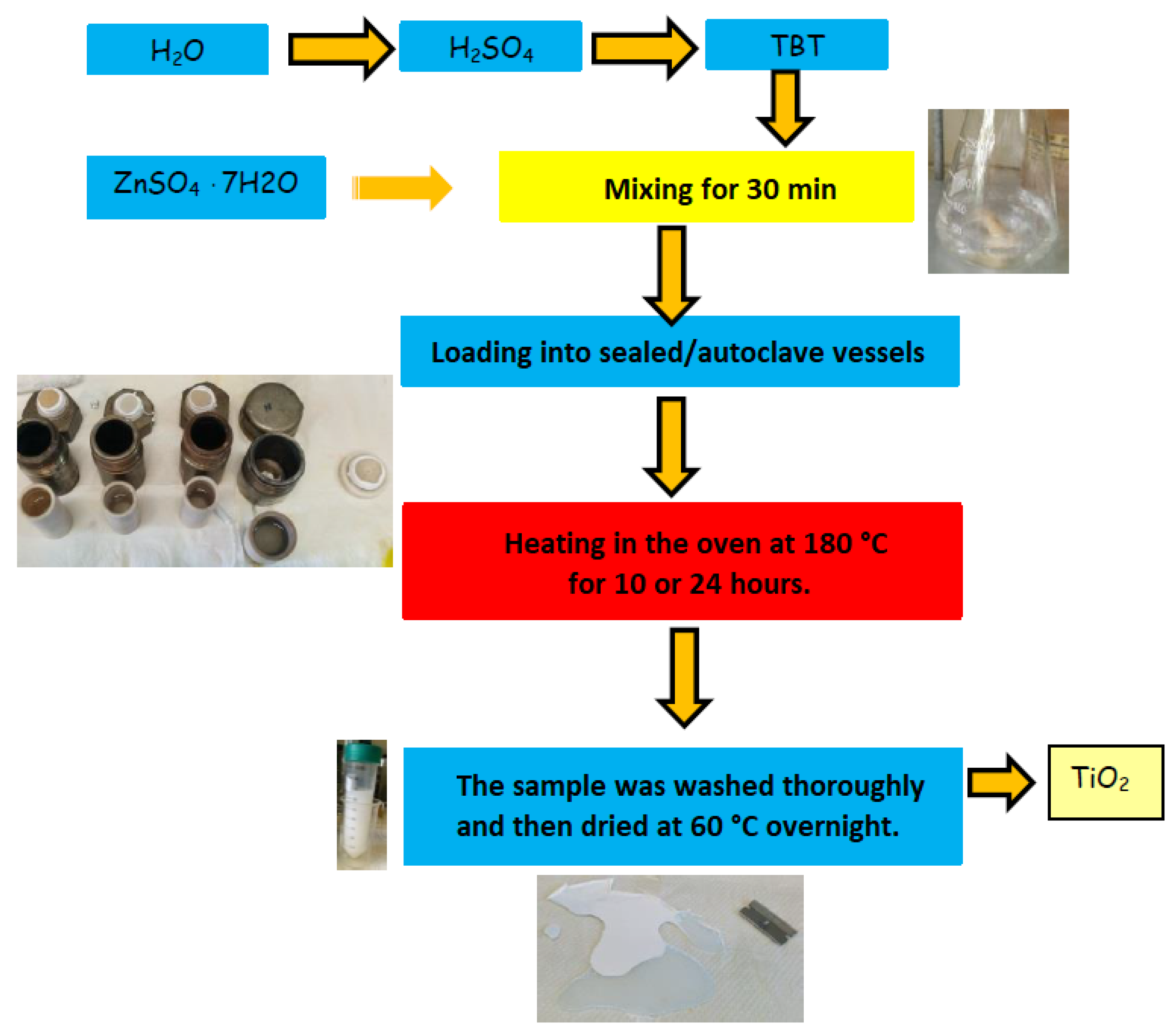

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

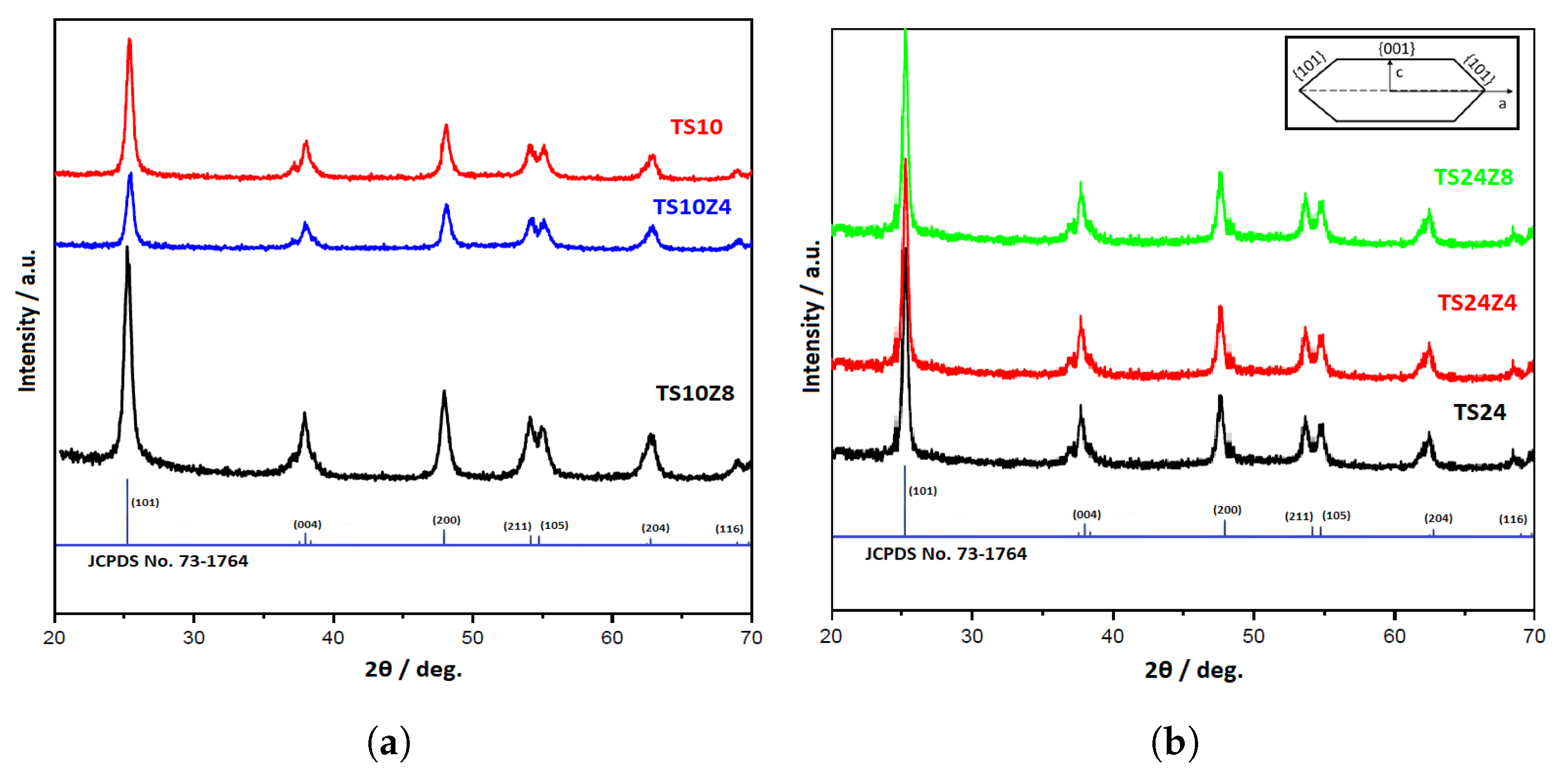

3.1. Crystalline Structures

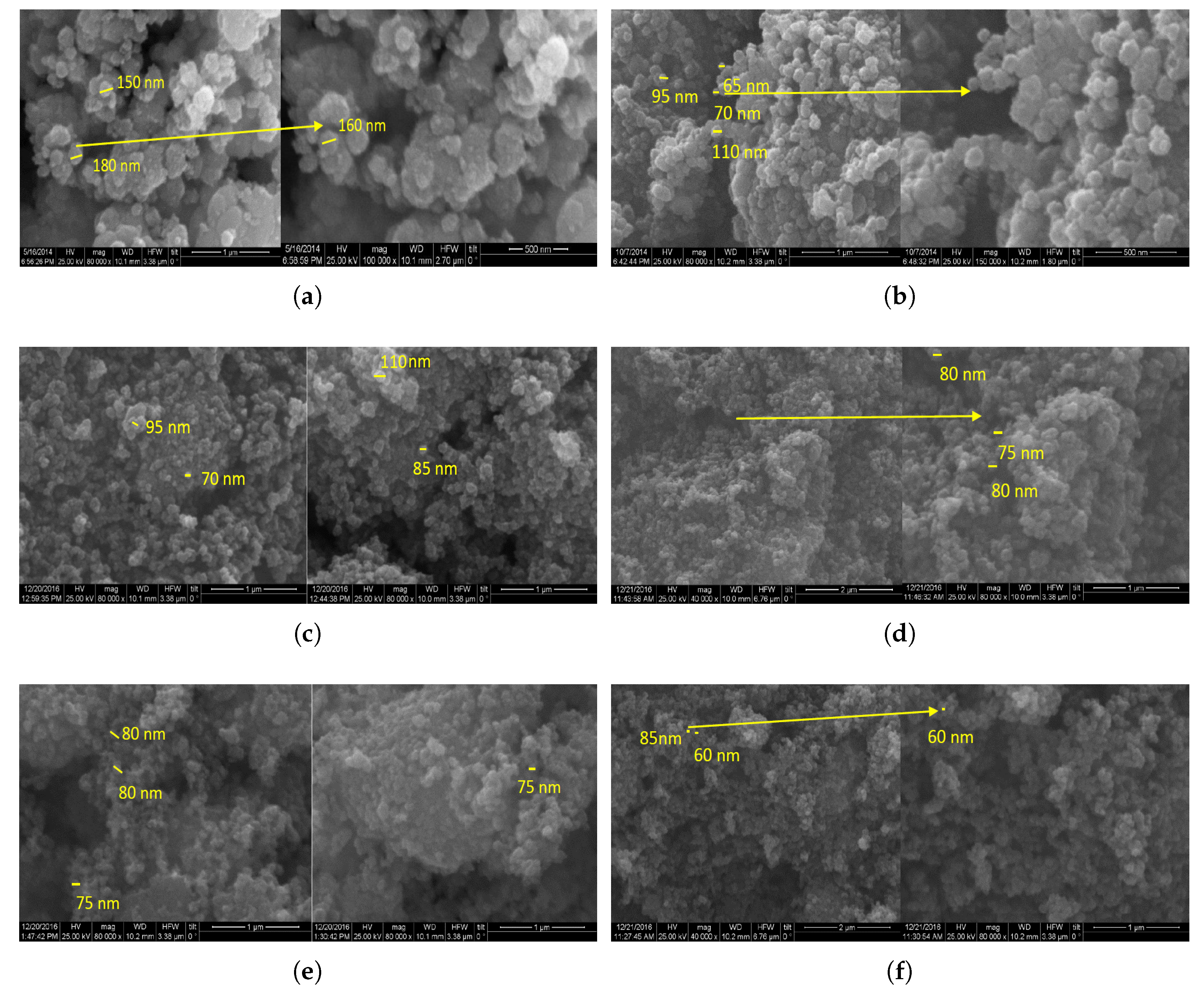

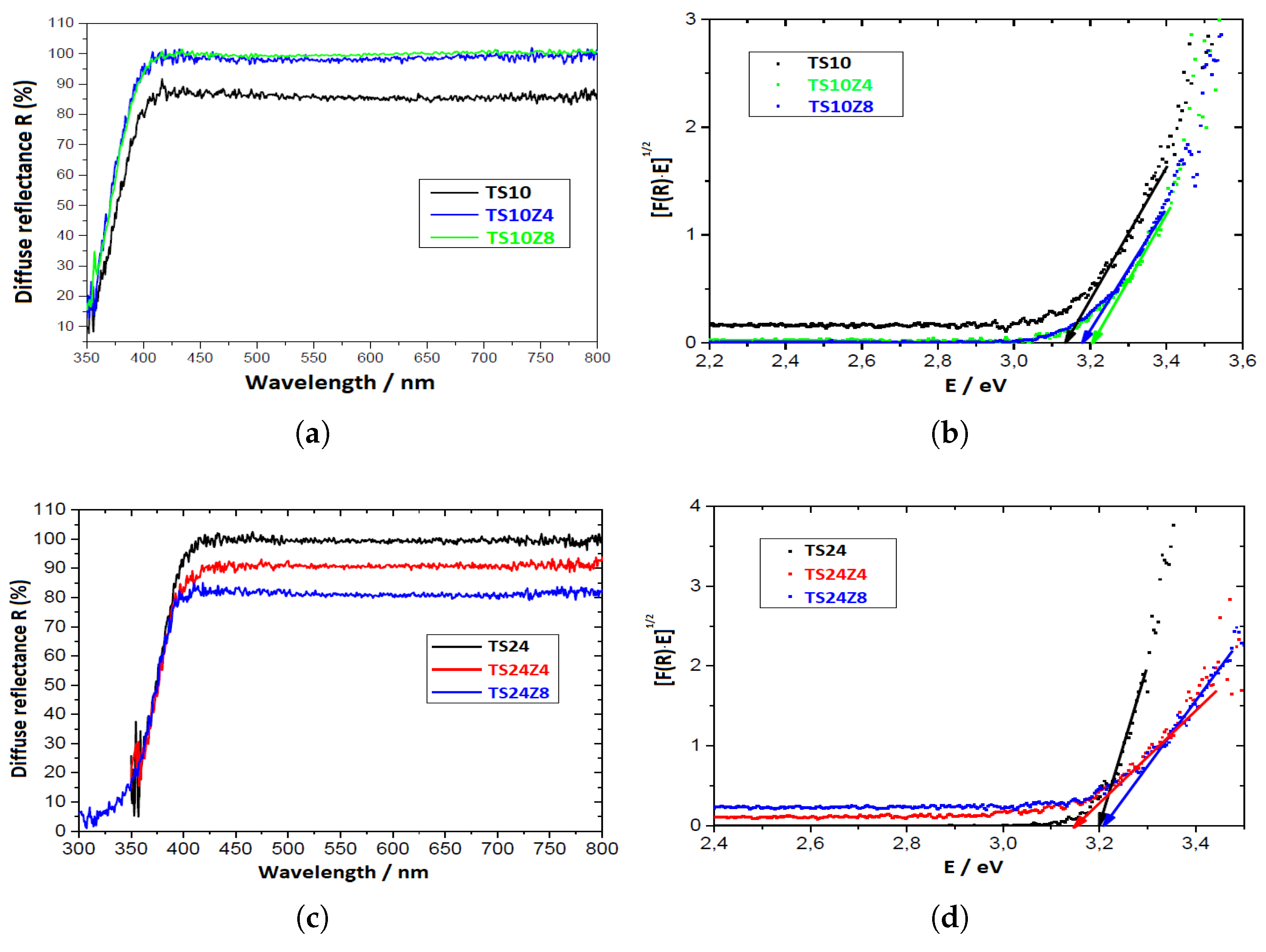

3.2. Morphology and Band Gap Analysis

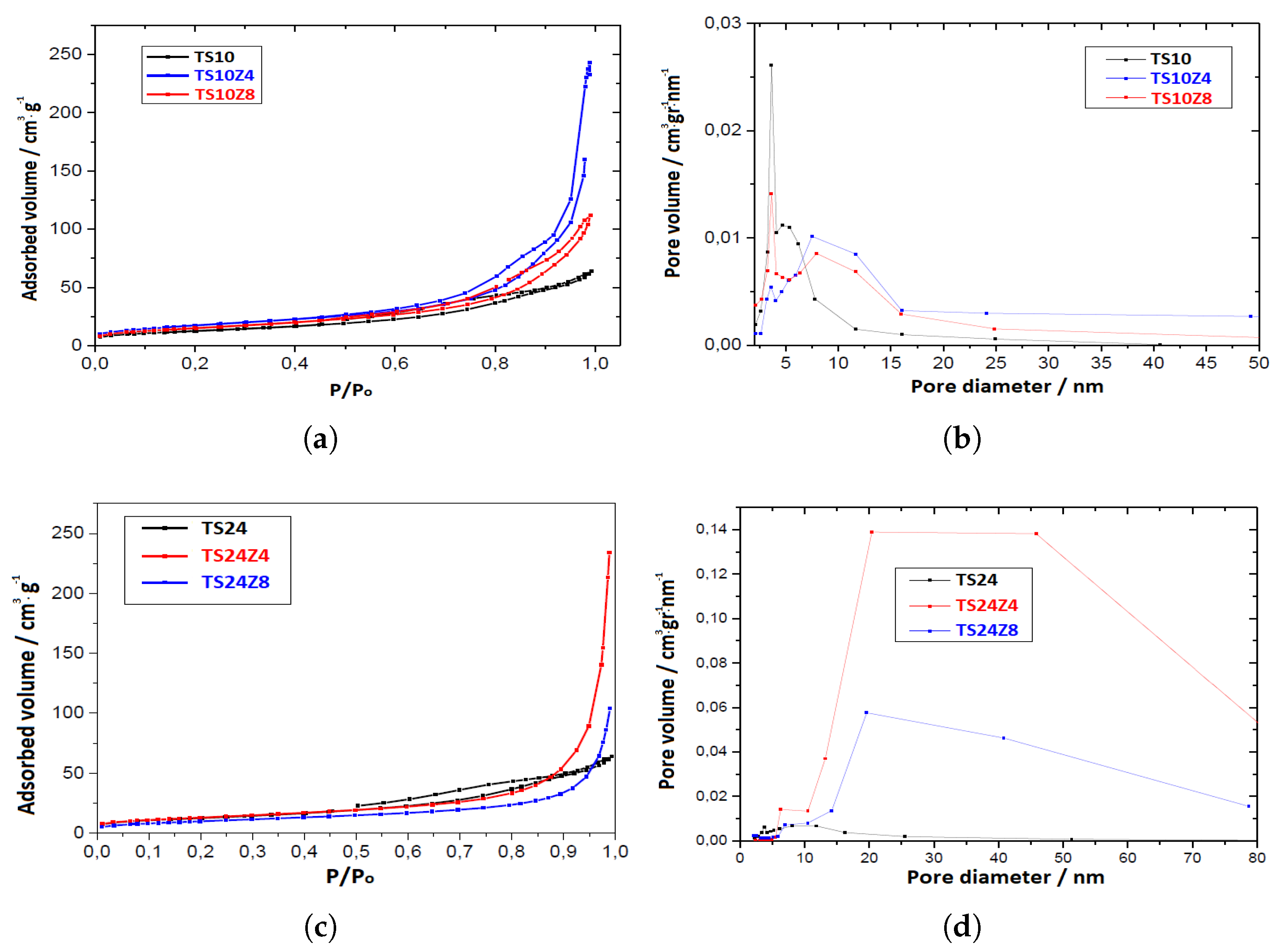

3.3. Specific Surface Area

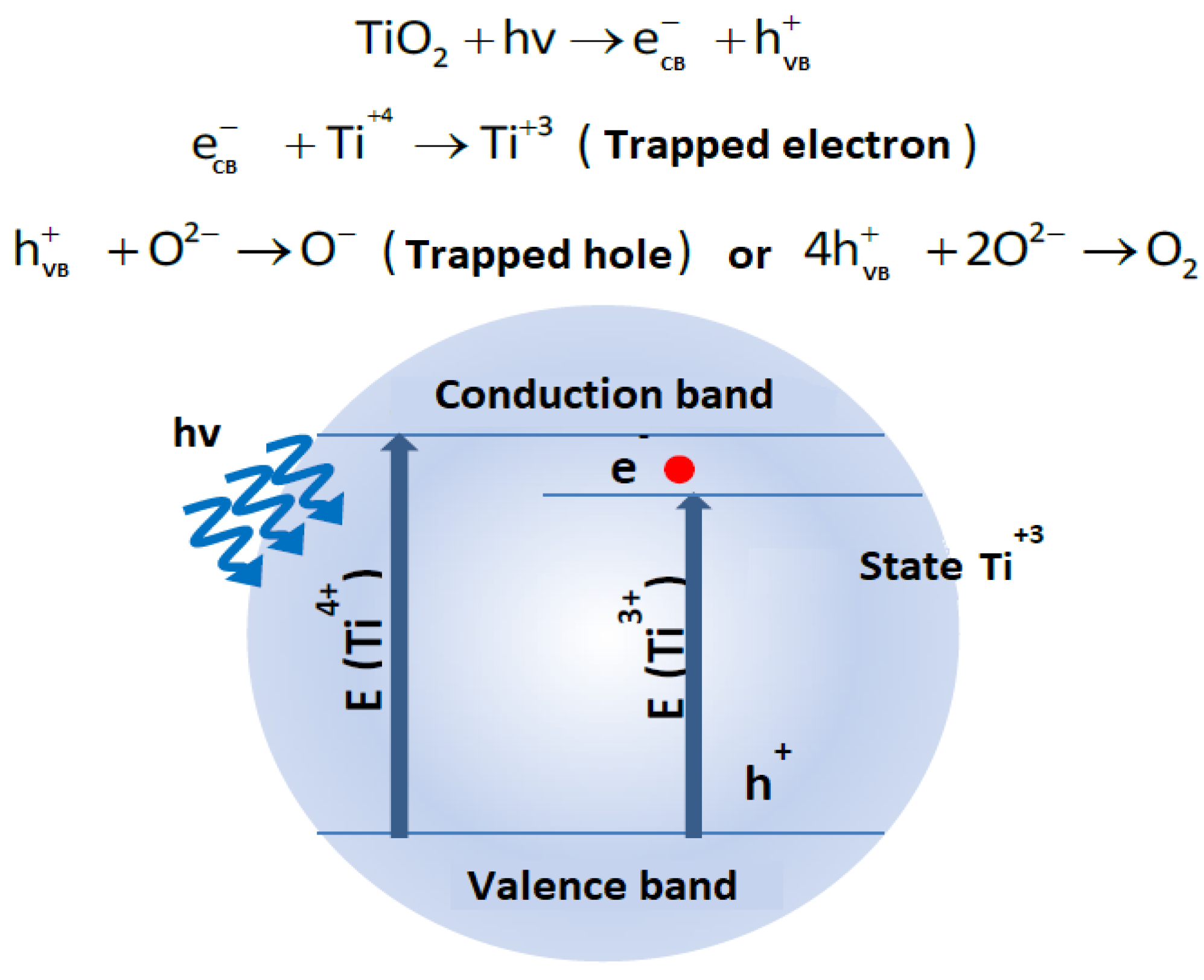

3.4. Photoconductivity

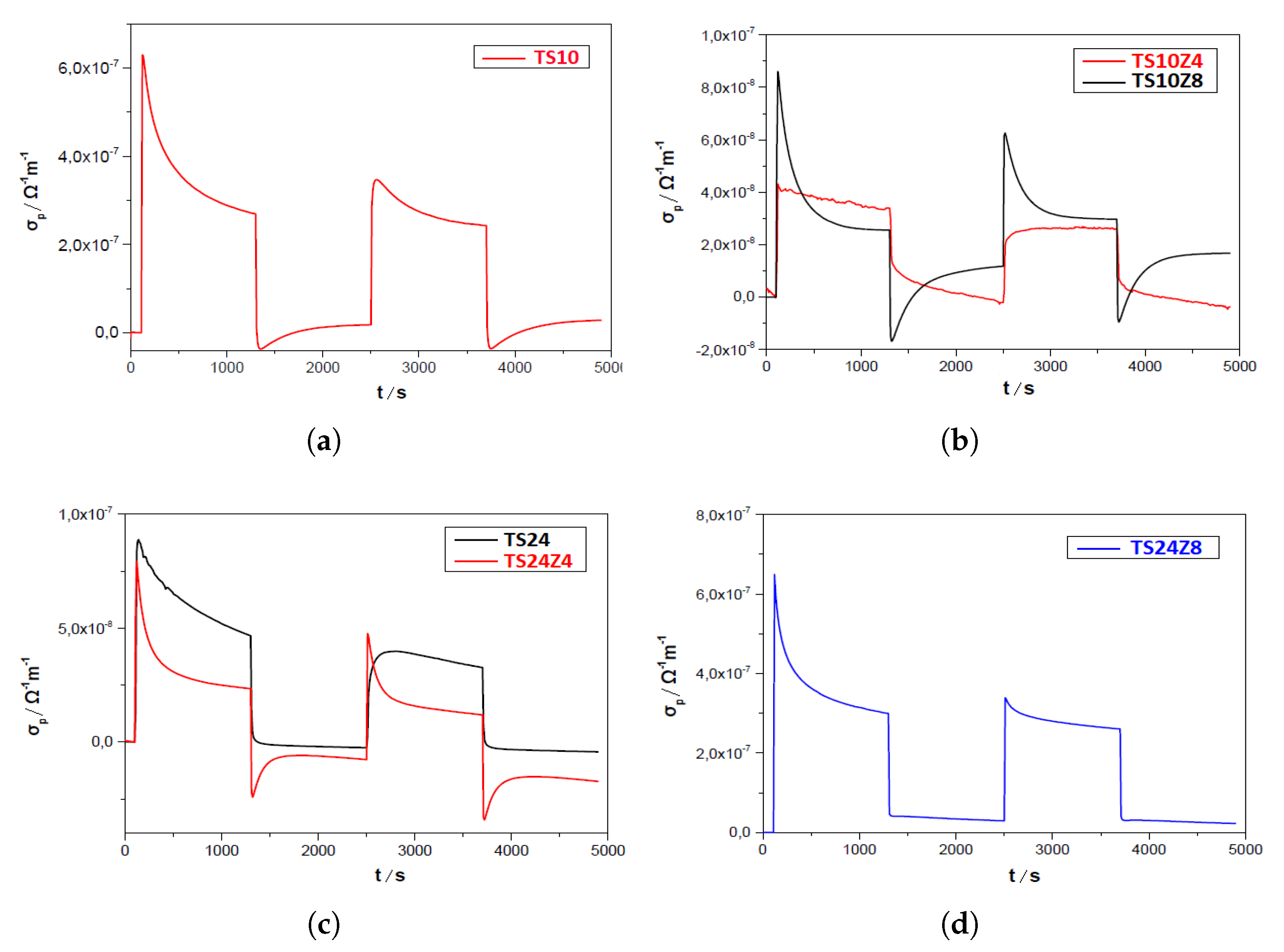

3.4.1. Vacuum

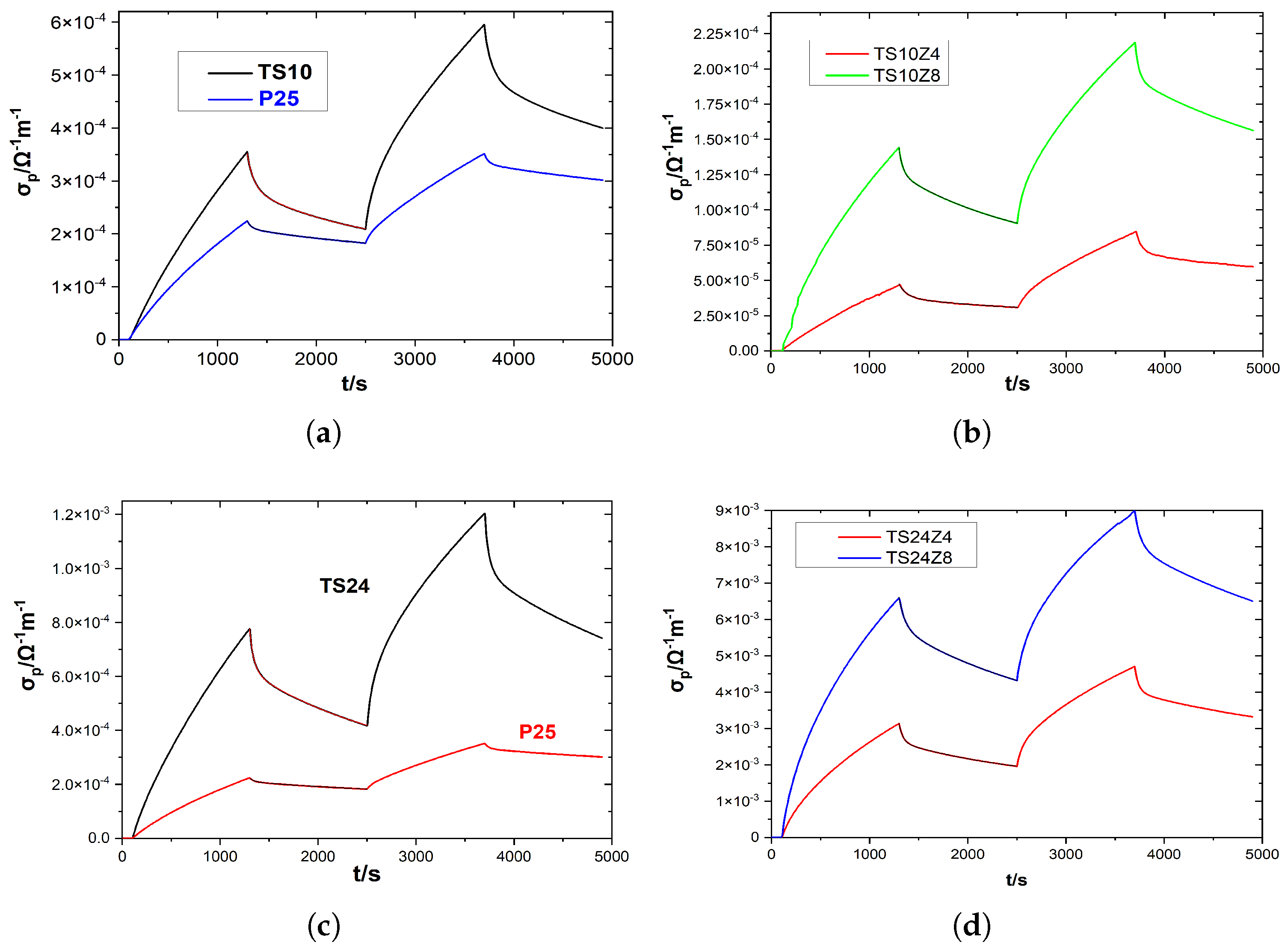

3.4.2. Air

3.5. Comparison Results

| Ref. | Synthesis method | Material | Property | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [32] | Sol-gel | /ZnO film | Photoconductivity | Performance reduced |

| [33] | Percipitation | powder | // | x8.6 increase in air |

| [34] | Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) | powder | Surface area | Increased activity |

| [35] | Hydrothermal/solvothermal | /ZnO powder | Photoconductivity | 65 % increase in vacuum |

| [36] | Atomic layer deposition (ALD) | film | Photocurrent density | x8 increase |

| [37] | Electrochemical | film | Conversion efficiency | Improved |

| CW | Hydrothermal | powder | Photoconductivity | x30 increase in vacuum |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kang, X.; Liu, S.; Dai, Z.; He, Y.; Song, X.; Tan, Z. Titanium dioxide: from engineering to applications. Catalysts 2019, 9, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, M.; Zafar, M. Titanium dioxide nanostructures as efficient photocatalyst: Progress, challenges and perspective. International Journal of Energy Research 2021, 45, 3569–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaez, M.; Nolan, N.T.; Pillai, S.C.; Seery, M.K.; Falaras, P.; Kontos, A.G.; Dunlop, P.S.; Hamilton, J.W.; Byrne, J.A.; O’shea, K.; et al. A review on the visible light active titanium dioxide photocatalysts for environmental applications. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2012, 125, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agócs, T.Z.; Puskás, I.; Varga, E.; Molnár, M.; Fenyvesi, É. Stabilization of nanosized titanium dioxide by cyclodextrin polymers and its photocatalytic effect on the degradation of wastewater pollutants. Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry 2016, 12, 2873–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Areerachakul, N.; Sakulkhaemaruethai, S.; Johir, M.; Kandasamy, J.; Vigneswaran, S. Photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants from wastewater using aluminium doped titanium dioxide. Journal of water process engineering 2019, 27, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Guo, D.; Shen, T.; Hou, X.; Zhu, M.; Liu, S.; Hu, Q. Titanium dioxide/magnetic metal-organic framework preparation for organic pollutants removal from water under visible light. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2020, 589, 124484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, C.; Gannon, P.; Gilson, P.; Kafizas, A.; Parkin, I.P.; Binions, R. Air purification by heterogeneous photocatalytic oxidation with multi-doped thin film titanium dioxide. Thin Solid Films 2013, 537, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Z.; Yu, H. Novel method of coating titanium dioxide on to asphalt mixture based on the breath figure process for air-purifying purpose. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2016, 28, 04015188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Kumar, N.; Kim, K.H.; Park, J. Photocatalytic efficacy of air purifiers equipped with self-cleaning titanium dioxide xerogel coatings against gaseous formaldehyde: A study using DRIFTS and DFT analysis. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 486, 150269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasanen, J.; Suvanto, M.; Pakkanen, T.T. Self-cleaning, titanium dioxide based, multilayer coating fabricated on polymer and glass surfaces. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2009, 111, 2597–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, Z.N.; Saleem, Z.; Riaz, S.; Naseem, S.; Saleemi, F. Deposition of porous titanium oxide thin films as anti-fogging and anti-reflecting medium. Optik 2016, 127, 5124–5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syafiq, A.; Balakrishnan, V.; Rahim, N.A. Durable self-cleaning nano-titanium dioxide superhydrophilic coating with anti-fog property. Pigment & Resin Technology 2024, 53, 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, S.; Petrovsky, V.; Dogan, F. Effects of sintering temperature on the microstructure and dielectric properties of titanium dioxide ceramics. Journal of materials science 2010, 45, 6685–6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, L.A.; Obianyo, I.I.; Amu, O.O.; Omoniyi, A.O.; Onwualu, A.P.; Soboyejo, A.B. Effects of titanium dioxide coatings on building composites for sustainable construction applications. Cogent Engineering 2022, 9, 2151168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felice, B.; Seitz, V.; Bach, M.; Rapp, C.; Wintermantel, E. Antimicrobial polymers: Antibacterial efficacy of silicone rubber–titanium dioxide composites. Journal of Composite Materials 2017, 51, 2253–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulazeem, L.; Al-Amiedi, B.; Alrubaei, H.A.; AL-Mawlah, Y.H. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles as antibacterial agents against some pathogenic bacteria. Drug Invention Today 2019, 12, 963–967. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Lin, P.; Ye, D.; Miao, H.; Cao, L.; Zhang, P.; Xu, J.; Dai, L. Enhanced Long-Term Antibacterial and Osteogenic Properties of Silver-Loaded Titanium Dioxide Nanotube Arrays for Implant Applications. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2025, 3749–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Hou, C. Application of nano-titanium dioxide in food antibacterial packaging materials. Bioengineering 2024, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, P.S.; Tseng, C.M.; Kuo, T.C.; Shih, C.K.; Li, M.H.; Chen, P. Microwave-assisted synthesis of titanium dioxide nanocrystalline for efficient dye-sensitized and perovskite solar cells. Solar Energy 2015, 120, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balis, N.; Zaky, A.A.; Perganti, D.; Kaltzoglou, A.; Sygellou, L.; Katsaros, F.; Stergiopoulos, T.; Kontos, A.G.; Falaras, P. Dye sensitization of titania compact layer for efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. ACS Applied Energy Materials 2018, 1, 6161–6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.Y.; Al-Salman, H.; Hussein, H.H.; Juraev, N.; Mahmoud, Z.H.; Al-Shuwaili, S.J.; Ahmed, H.H.; Ami, A.A.; Ahmed, N.M.; Azat, S.; et al. Experimental and theoretical study of improved mesoporous titanium dioxide perovskite solar cell: The impact of modification with graphene oxide. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Liu, L.; Tan, J.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, Z.; Xia, D.; Shu, H.; Yang, X.; Wang, X. One-pot synthesis of bicrystalline titanium dioxide spheres with a core–shell structure as anode materials for lithium and sodium ion batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2014, 269, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Yin, G.; Du, C.; Sun, X. Ti-based oxide anode materials for advanced electrochemical energy storage: lithium/sodium ion batteries and hybrid pseudocapacitors. Small 2019, 15, 1904740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, K.; Ao, H.; Gong, Y.; Yu, K.; Liang, C. Template-free synthesis of hollow titanium dioxide microspheres and amorphous titanium dioxide microspheres with superior lithium and sodium storage performance. Journal of Energy Storage 2025, 105, 114759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Weng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; Mi, Y.; Chong, R.; Han, H.; Li, C. Achieving overall water splitting using titanium dioxide-based photocatalysts of different phases. Energy & Environmental Science 2015, 8, 2377–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, A.; Nishioka, S.; Maeda, K. Water splitting on rutile TiO2-based photocatalysts. Chemistry–A European Journal 2018, 24, 18204–18219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Prasad Singh, G.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, A.; Singh, P.; Ansu, A.K.; Sharma, A.; Alam, T.; Yadav, A.S.; Dobrota, D. Nanocomposite marvels: Unveiling breakthroughs in photocatalytic water splitting for enhanced hydrogen evolution. ACS omega 2024, 9, 6147–6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanavicius, S.; Jagminas, A.; Ramanavicius, A. Gas sensors based on titanium oxides. Coatings 2022, 12, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Kumar, Y.; Husain, S. Fabrication of symmetric polyaniline/nano-titanium dioxide/activated carbon supercapacitor device in different electrolytic mediums: role of high surface area of carbon and facile interactions with nano-titanium dioxide for high-performance supercapacitor. Energy Technology 2023, 11, 2200931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, F.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, T.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Ma, J.; Zhang, K.; Ouyang, H.; Qiu, X.; et al. Titanium dioxide nanomaterials: Progress in synthesis and application in drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandoliya, R.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, V.; Joshi, R.; Sivanesan, I. Titanium dioxide nanoparticle: A comprehensive review on synthesis, applications and toxicity. Plants 2024, 13, 2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgakopoulos, T.; Todorova, N.; Pomoni, K.; Trapalis, C. On the transient photoconductivity behavior of sol–gel TiO2/ZnO composite thin films. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2015, 410, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, C.; Arulraj, A. One-step synthesis of needle-like lanthanum-doped TiO2 nanomaterials and their photoconductivity activity in air medium. Materials Letters 2025, 380, 137733. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara, Y.; Yamakawa, T.; Sakai, Y.; YAMASAKI, A.; SATOKAWA, S.; KOJIMA, T. Synthesis of TiO2 by CVD using Titanium Tetraisopropoxide and their Photocatalytic Activity. Journal of Ecotechnology Research 2010, 15, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Georgakopoulos, T.; Todorova, N.; Boukos, N.; Pomoni, K.; Trapalis, C. Evaluation of the photoconductive and photocatalytic properties of nanocrystalline TiO2/ZnO powder systems prepared by one-step hydro-solvothermal method. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2025, 322, 118637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasinska, A.; Singh, T.; Wang, S.; Mathur, S.; Kraehnert, R. Enhanced photocatalytic performance in atomic layer deposition grown TiO2 thin films via hydrogen plasma treatment. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A 2015, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Kamble, A.A.; Ubale, P.A.; Jadhav, A.L.; Jadhav, S.L.; Kadam, A.V.; Kanamadi, C.M.; Bhuse, V.M. Studies on optical, structure, and photoconductivity of titanium dioxide thin films prepared by chemical bath deposition via aqueous route. In Proceedings of the Macromolecular Symposia. Wiley Online Library, Vol. 400; 2021; p. 2100020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, M.; Du, P.; Zhao, J.; Fan, H. Phase control of hierarchically structured mesoporous anatase TiO 2 microspheres covered with {001} facets. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2012, 22, 21965–21971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Feng, Q.; Yamasaki, N. Formation mechanism of fine anatase crystals from amorphous titania under hydrothermal conditions. Journal of materials research 1998, 13, 825–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, K.; Ovenstone, J. Crystallization of anatase from amorphous titania using the hydrothermal technique: effects of starting material and temperature. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 1999, 103, 7781–7787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, T.; Liu, H.; Huang, B.; Zhang, Q. Hierarchical flower-like nanostructures of anatase TiO2 nanosheets dominated by {001} facets. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2016, 657, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, W.J.; Tan, L.L.; Chai, S.P.; Yong, S.T.; Mohamed, A.R. Highly reactive {001} facets of TiO 2-based composites: synthesis, formation mechanism and characterization. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 1946–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofianou, M.V.; Tassi, M.; Psycharis, V.; Boukos, N.; Thanos, S.; Vaimakis, T.; Yu, J.; Trapalis, C. Solvothermal synthesis and photocatalytic performance of Mn4+-doped anatase nanoplates with exposed {0 0 1} facets. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2015, 162, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A. Modified Kubelka–Munk model for calculation of the reflectance of coatings with optically-rough surfaces. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 2006, 39, 3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P. The use of van der waals adsorption isotherms in determining the surface area of iron synthetic ammonia catalysts. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1935, 57, 1754–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmett, P.H.; Brunauer, S. The use of low temperature van der Waals adsorption isotherms in determining the surface area of iron synthetic ammonia catalysts. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1937, 59, 1553–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K.S. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity (Recommendations 1984). Pure and applied chemistry 1985, 57, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouquerol, J.; Avnir, D.; Everett, D.; Fairbridge, C.; Haynes, M.; Pernicone, N.; Ramsay, J.; Sing, K.; Unger, K. Guidelines for the characterization of porous solids. In Studies in surface science and catalysis; Elsevier, 1994; Vol. 87, pp. 1–9.

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Rong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Pan, C. Characterization of oxygen vacancy associates within hydrogenated TiO2: a positron annihilation study. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2012, 116, 22619–22624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao-Quan, C.; Huan-Bin, L.; Guo-Bang, G. Preparation of nanometer crystalline TiO2 with high photo-catalytic activity by pyrolysis of titanyl organic compounds and photo-catalytic mechanism. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2005, 91, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Gao, S.; Huang, B.; Dai, Y. Preparation of Ti3+ self-doped TiO2 nanoparticles and their visible light photocatalytic activity. Chinese Journal of Catalysis 2015, 36, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yang, X.; Sheng, W.; Xing, M.; Zhang, J. Facile synthesis of the Ti3+ self-doped TiO2-graphene nanosheet composites with enhanced photocatalysis. Scientific reports 2015, 5, 8591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisuk, A.; Klansorn, E.; Praserthdam, P. Effects of reaction medium and crystallite size on Ti3+ surface defects in titanium dioxide nanoparticles prepared by solvothermal method. Catalysis Communications 2008, 9, 1810–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Xu, T.; Yin, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, C. Management on the location and concentration of Ti3+ in anatase TiO2 for defects-induced visible-light photocatalysis. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2015, 176, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satuf, M.L.; Brandi, R.J.; Cassano, A.E.; Alfano, O.M. Photocatalytic degradation of 4-chlorophenol: a kinetic study. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2008, 82, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.; Huang, Z.; Lv, K.; Tang, D.; Yang, C. Facile preparation of Ti3+ self-doped TiO2 nanosheets with dominant {0 0 1} facets using zinc powder as reductant. Journal of alloys and compounds 2014, 601, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Huang, B.; Meng, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Lou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qin, X.; Zhang, X.; Dai, Y. Metallic zinc-assisted synthesis of Ti 3+ self-doped TiO 2 with tunable phase composition and visible-light photocatalytic activity. Chemical Communications 2013, 49, 868–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakopoulos, T.; Apostolopoulou, A.; Todorova, N.; Pomoni, K.; Trapalis, C.; Stathatos, E. Evaluation of photoconductive and photoelectrochemical properties of mesoporous nanocrystalline TiO2 powders and films prepared in acidic and alkaline media. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2017, 692, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, A.; Jawahar, I.; Biju, V. Photogenerated charge carrier processes in carbonate derived nanocrystalline ZnO: photoluminescence, photocurrent response and photocatalytic activity. Applied Physics A 2024, 130, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruda, H.E. Photoconductivity of Nanowire Systems. Photoconductivity and Photoconductive Materials: Fundamentals, Techniques and Applications 2022, 2, 493–522. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, J.T.; Wilkins, M.H.F. Phosphorescence and electron traps-I. The study of trap distributions. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1945, 184, 365–389. [Google Scholar]

- Georgakopoulos, T.; Sofianou, M.; Pomoni, K.; Todorova, N.; Giannakopoulou, T.; Trapalis, C. The environment effect on the electrical conductivity and photoconductivity of anatase TiO2 nanoplates with silver nanoparticles photodeposited on {101} crystal facets. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2016, 56, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Xie, C.; Wu, J.; Zeng, D.; Liao, Y. A comparative study on UV light activated porous TiO2 and ZnO film sensors for gas sensing at room temperature. Ceramics International 2012, 38, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoshenko, V.Y.; Duzhko, V.; Dittrich, T. Diffusion photovoltage in porous semiconductors and dielectrics. physica status solidi (a) 2000, 182, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reagent / Material | Abbreviation | Source | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Titanium butoxide (Ti) | TBT | Merck | M = 340.36 g/mol = 1.00 kg/L |

| Sulfuric acid () | SA | Fluka | M = 98.08 g/mol = 1.84 kg/L |

| Zinc sulfate heptahydrate (O) | ZS | Sigma-Aldrich | M = 287.53 g/mol = 2.07 kg/L |

| Samples | ZS (g) | Abbreviation | Reaction time (h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10h | 0 | TS10 | 10 |

| 10h 4% ZS | 0.120 | TS10Z4 | 10 |

| 10h 8% ZS | 0.183 | TS10Z8 | 10 |

| 24h | 0 | TS24 | 24 |

| 24h 4% ZS | 0.120 | TS24Z4 | 24 |

| 24h 8% ZS | 0.183 | TS24Z8 | 24 |

| Samples | d(101) nm | d(004) nm | d(200) nm |

|---|---|---|---|

| TS10 | 15.77 | 17.95 | 15.04 |

| TS10Z4 | 16.06 | 15.28 | 16.13 |

| TS10Z8 | 16.65 | 18.14 | 16.50 |

| TS24 | 17.50 | 21.69 | 17.80 |

| TS24Z4 | 19.71 | 18.62 | 19.27 |

| TS24Z8 | 22.18 | 24.34 | 22.65 |

| Samples | (eV) |

|---|---|

| TS10 | 3.16 |

| TS10Z4 | 3.21 |

| TS10Z8 | 3.19 |

| TS24 | 3.20 |

| TS24Z4 | 3.12 |

| TS24Z8 | 3.21 |

| Samples | S(/g) | (/g) | (nm) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS10 | 45.33 | 0.099 | 7.28 | 27.26 |

| TS10Z4 | 62.48 | 0.376 | 19.64 | 58.82 |

| TS10Z8 | 54.85 | 0.173 | 10.65 | 39.64 |

| TS24 | 47.63 | 0.173 | 13.41 | 39.68 |

| TS24Z4 | 46.20 | 0.362 | 24.54 | 57.92 |

| TS24Z8 | 36.15 | 0.161 | 16.17 | 37.91 |

| Samples | (eV) | (eV) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P25 | 1.53 | 2.24 | 3.52 | 0.671 | 0.671 |

| TS10 | 1.46 | 3.55 | 5.96 | 0.682 | 0.614 |

| TS10Z4 | 4.66 | 4.66 | 8.43 | 0.689 | 0.620 |

| TS10Z8 | 6.22 | 1.44 | 2.20 | 0.688 | 0.602 |

| TS24 | 1.44 | 7.78 | 1.20 | 0.690 | 0.604 |

| TS24Z4 | 6.04 | 3.14 | 4.71 | 0.688 | 0.602 |

| TS24Z8 | 9.98 | 6.70 | 9.00 | 0.692 | 0.613 |

| Samples | ||

|---|---|---|

| TS10 | 1.46 | 2.65 |

| TS10Z4 | 2.78 | 3.40 |

| TS10Z8 | 2.26 | 2.55 |

| TS24 | 3.50 | 4.46 |

| TS24Z4 | 3.49 | 2.34 |

| TS24Z8 | 2.76 | 4.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).