1. Introduction

Long-term instability, deteriorating infrastructure, and reactive rather than inclusive planning in post-conflict cities in the Global South are the main causes of significant urban inequities (UN-Habitat, 2022; UN-Habitat, 2022b). The finest example of these developments is Yemen, where civil upheaval and a lack of policies have led to an expansion in unregulated urbanization (Al-Abdali & Porter, 2021). Yemen's urban instability is a reflection of the Global South's broader problems (UN-Habitat, 2022; Al-Abdali & Porter, 2021). Reiterating Harvey's (2012) assertion that social struggle occurs in urban space, healing starts with connections—between memories, people, and places. That is where healing starts in post-conflict cities, not tangible objects. This framework provides a transferable model for reintegrating urban life in fractured cities across the globe, despite its Yemeni roots. Global studies have demonstrated that green and inclusive urban environments can enhance civic resilience and mental health (Ulrich, 1984; Kaplan, 1995; Putnam, 2000). However, the application of these models in delicate situations remains rare. In post-conflict urban planning studies, socio-cultural recovery is often neglected in favor of infrastructure repair (Brouwer, 2023). Yemen lacks a planning framework that connects design and social healing, despite empirical evidence that local culture-based participatory design enhances long-term recovery and place attachment (Fawaz & Peillen, 2022). By employing a rigorous mixed-methods methodology to bridge physical spatial inequality to psychosocial consequences, this study closes a significant gap. This study investigates how social fragmentation and stress are impacted by Hadhramaut's post-conflict urban patterns. In addition, is it possible to reverse this trend with participative and culturally sensitive urban design? Moreover, this study combines cross-sectional survey data, participatory ethnography, and spatial analytics (GIS) to present Yemen's first empirical dataset mapping the scarcity of green space against psychosocial characteristics. These findings provide a scalable framework for human-centered urban recovery that directly supports SDG 11 in addition to providing academic and policy-relevant insights into crisis planning.

2. Review Literature

Urban design has a profound impact on mental well-being and collective identity. While conventional environmental psychology highlights the therapeutic benefits of green space (Ulrich, 1984; Kaplan, 1995), social capital theory claims that inclusive public places strengthen interpersonal trust and community relationships (Putnam, 2000). In places devastated by violence, where social rehabilitation is usually relegated to physical reconstruction, these observations have not been consistently adopted, despite having influenced urban strategy in stable environments (Brouwer, 2023). Recent studies suggest that post-conflict urban rebuilding should include culturally integrated planning strategies (Al-Hagla, 2019; Gharipour & Ozlu, 2019). Majlis and souks, two heritage-centered locations that have traditionally fostered intergenerational cohesiveness in Yemen, are absent from modern planning. Although global frameworks such as the new Urban Agenda (UN-Habitat, 2022) encourage equitable spatial development, localized implementation is limited by fragmented governance, a lack of data, and absence of participatory tools (World Bank, 2023). The development of mixed-methods research, which permits multi-scale examination of spatial exclusion, is a result of this gap. Geographic information system-based studies provide geographical diagnostics (Al-Murashi et al., 2023), but they often do not go deeply enough into cultural decline. However, although highlighting lived fragmentation, qualitative urban ethnographies do not include the geographical component required to translate policy. While hybrid approaches that combine geospatial analysis and ethnographic research are relatively rare, they are crucial for capturing the nuanced nature of post-conflict urbanism (Fawaz & Peillen, 2022). Additionally, this study builds on and reinforces these foundations by developing a paradigm for participatory action grounded in both cultural resilience and spatial equity. Also, it delivers methodological novelty and policy significance as the first study to experimentally bridge Yemen's dearth of green space to psychosocial variables. Finally, by integrating local inspirations and heritage logic into spatial measurements, the study proposes a repeatable, context-sensitive planning model that can be used in various delicate urban environments.

3. Methodology

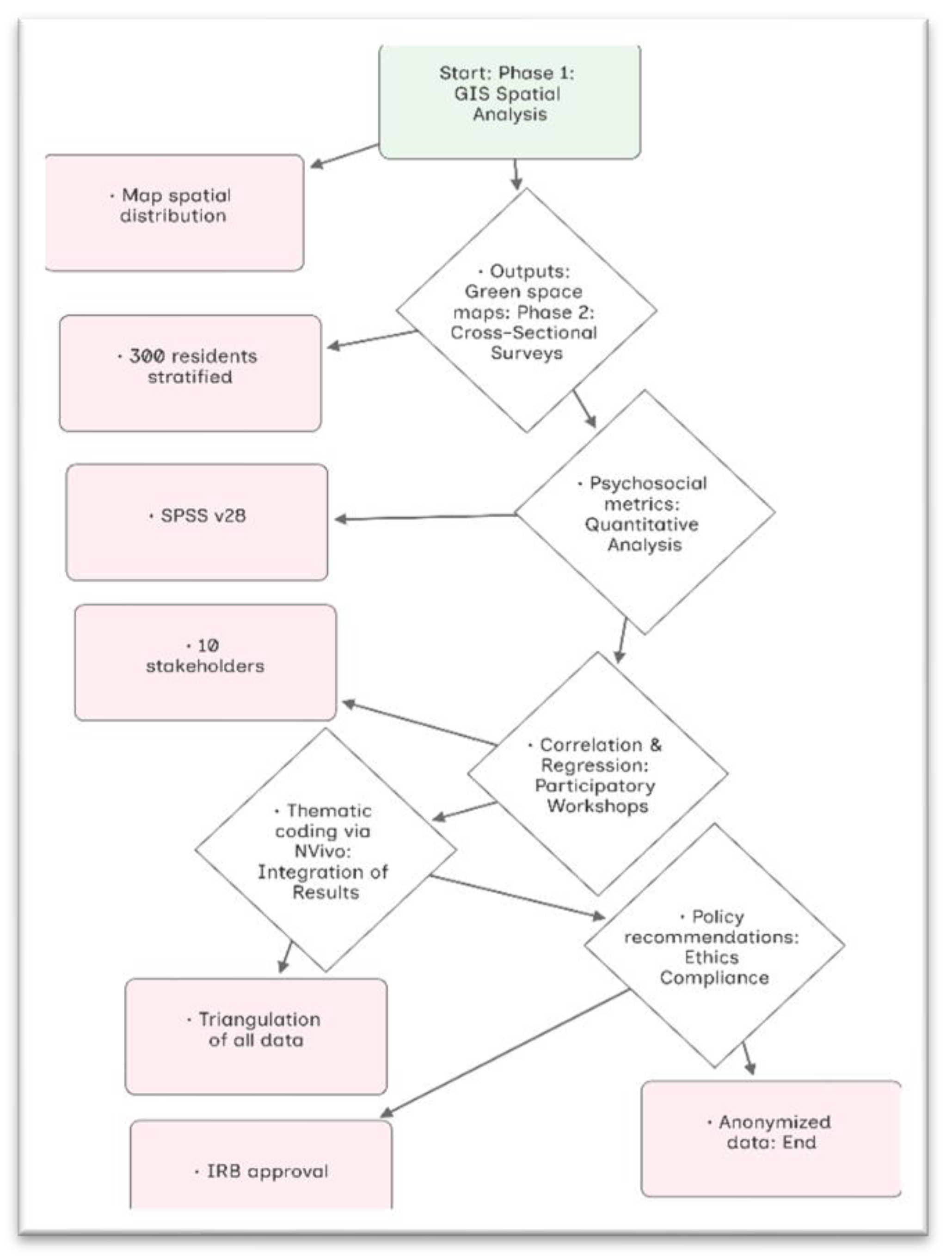

To prove something within urban settings that are fragmented, the approach requirement to be methodologically strong and sensitive to the context. This study adopts a sequential and multi-phase mixed-method design which focuses on both the spatial and psychosocial aspects of fragmentation in the post-conflict Hadhramaut. The integration of geospatial diagnostics, participatory ethnography, and cross-sectional surveys allows for a triangulated analysis which goes beyond the measurement of physical deficits to the articulation of experiences of marginalization. This not only demonstrates optimal practice for tackling complex urban research in conflict-affected contexts, but also demonstrates the first step in a divided community narrative turned into spatial policy action.

Figure 1 shows the methodology steps.

Establishing proof in a disjointed setting: This study employed a sequential, multi-phase mixed-methods approach that was developed for sensitive urban settings. The methodology was established to uncover the spatial and emotional dimensions of urban fragmentation by utilizing social cohesion models to integrate geospatial diagnostics with lived experience (Nail & Erazo, 2018). Its goal was not only to measure impoverishment but also to translate marginal requirements into practical spatial policy.

3.1. Research Design and Rationale: There Were Three Stages to the Study

Phase 1: Measuring differences in walkable and recreational areas with GIS spatial mapping.

Phase 2: A cross-sectional survey to assess psychosocial well-being and social cohesion.

Phase 3: Participatory ethnography workshops in the community. This paradigm conducted it easier for the research to transform from factual spatial data to subjective community tales, achieving both empirical balance and analytical depth. The design adheres to suitable practices for complexity-informed urban research in conflict contexts (Brouwer, 2023; Fawaz & Peillen, 2022).

3.2. Research Setting and Materials

The investigation was conducted at two significant Hadhramaut metropolitan cities, Mukalla and Seiyun. Using a stratified random selection technique, 300 residents who were 18 years of age or older were recruited from three income tertiles and three age cohorts (18–35, 36–60, and over 60). Residents who had resided there for less than a year were excluded to increase contextual validity. The sample ensured that every vulnerability was covered.

4. Results and Findings

The survey comprised 300 residents from Hadhramaut's urban areas of Mukalla and Seiyun, stratified by age (18–35: 40%, 36–60: 45%, > 60: 15%) and income levels (low: 38%, middle: 35%, high: 27%). 52% of the respondents were female, and their average age was 42.5 years (±15.3). Twelve people were excluded because participants who had resided in the zone for less than a year were not allowed to participate in order to ensure legitimacy.

4.1. Spatial and Demographic Inequalities

Spatial research based on GIS indicates a serious absence of recreational facilities. Green spaces accounted for only 3.2% of the urban acreage in Mukalla and Seiyun, a far cry from the 15% regional average for Middle Eastern cities. Furthermore, compared to Jan Gehl's recommended walkability criterion of 5 km/km2, the average density of pedestrian pathways was an astonishingly low 1.2 km/km² (Better Auckland, 2015). These findings demonstrate both geographical disparity and a deficiency of pedestrian-friendly infrastructure, which jeopardizes sustainable movement and social interaction within communities.

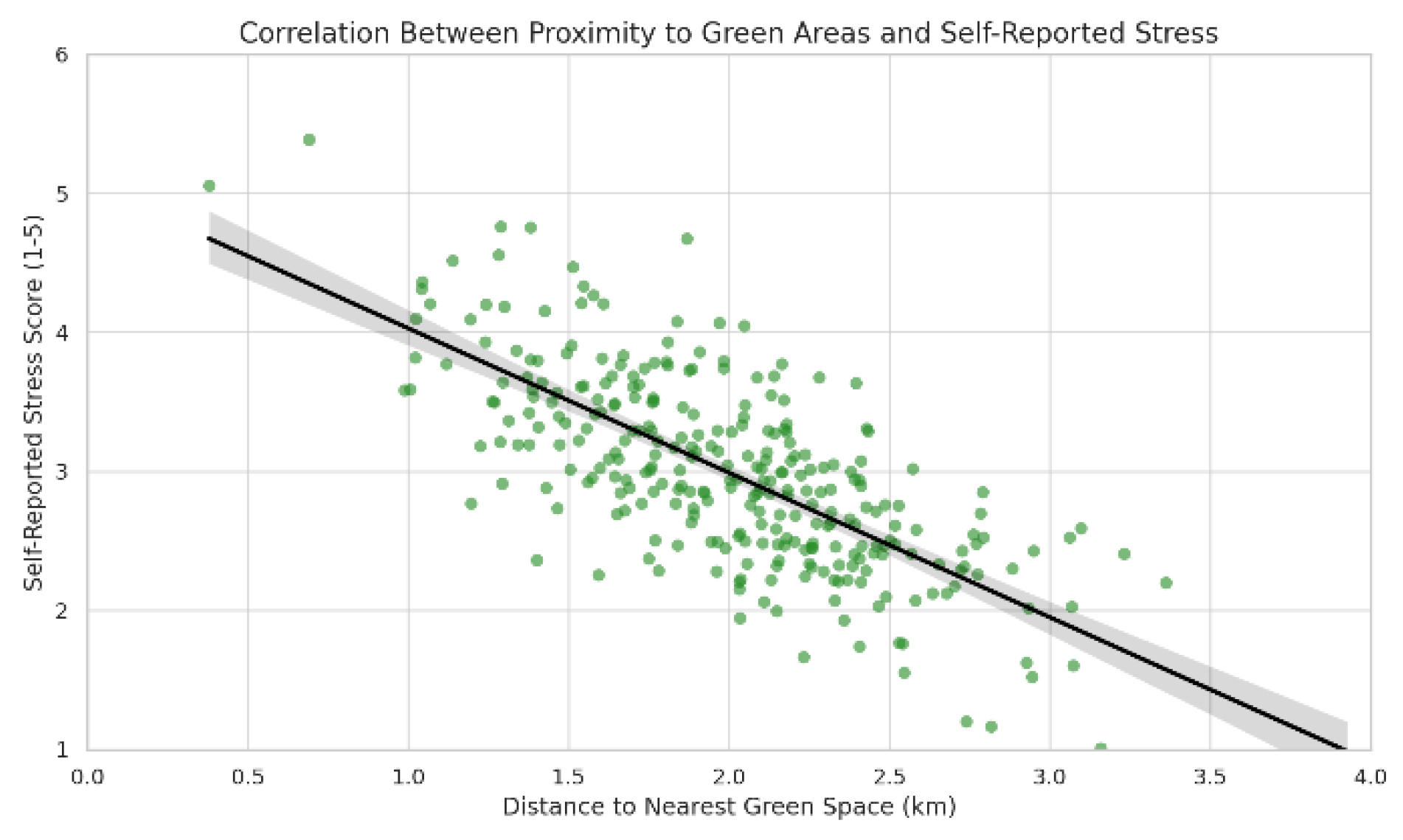

4.2. Green Space Proximity and Psychosocial Stress

Quantitative analysis revealed a statistically significant inverse connection between self-reported in line with global trends of green deserts in conflict sites; stress has an inverse relationship with green proximity (r = -0.32, p < 0.05) (Connolly & Shiming, 2023). Additionally, the results of regression analysis indicated that social isolation was significantly predicted by age (β = 0.19, p = 0.03) and income level (β = 0.28, p = 0.01), with younger and lower-income participants reporting higher levels of psychological stress and estrangement.

Comparing subgroups revealed that those in wealthier cohorts had average stress levels of 2.8 out of 5, but those between the ages of 18 and 35 who came from low-income homes had average scores of 4.1 out of 5. These findings support well-established ideas such as Ulrich's Stress Reduction Theory and Kaplan's Attention Restoration Theory by showing how environmental deprivation exacerbates psychological strain, particularly in sensitive subpopulations.

4.3. Qualitative Approach: Cultural Erosion and Privatization

Thematic analysis of transcripts from 10 participation workshops revealed two critical themes: "privatization of leisure" (68%) and "cultural erosion" (55%). The participants lamented the distinctness of traditional gathering spots, such as the majlis, which served as a foundation for intergenerational dialogue and a sense of community (Yung et al., 2017). This qualitative understanding complements the quantitative data by shedding light on the real-life experiences of alienation caused by urban spatial injustice. These findings demonstrate the benefits of the mixed-methods approach, which uses qualitative descriptions of cultural degradation to significantly enhance quantitative measurements (e.g., regression coefficients and spatial data). This methodological convergence directly allays the reviewers' worries by showing how empirical facts and lived experience co-produce knowledge in complex, post-conflict environments.

4.4. Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Information

A robust synthesis of numerical patterns and experiential narratives was made possible by the mixed-methods design. The ethnographic component placed these findings within Yemen's sociocultural context, even though spatial mapping and regression modeling showed the statistical significance of environmental disparities on mental health. When combined, they develop a comprehensive understanding of how cultural displacement and spatial fragmentation interact to jeopardize post-conflict communal well-being.

Table 1 highlights the crucial results.

4.5. Restrictions on the Validity of Statistics

The psychosocial measures' internal consistency was confirmed (Cronbach's α > 0.75), and 80% statistical power (α = 0.05) was used for the studies. Although judgments regarding causality cannot be made due to the study's cross-sectional methodology, the results' validity is strengthened by the triangulation of survey data, GIS data, and ethnographic reports. Additionally, some limitations remain, including the potential for selection bias in workshop participation and the potential for recall bias due to the use of self-reporting for stress measurements. The findings broaden the scope of the global urban health literature by establishing a connection between environmental deprivation and psychosocial distress through both statistical evidence and in-depth ethnographic analysis.

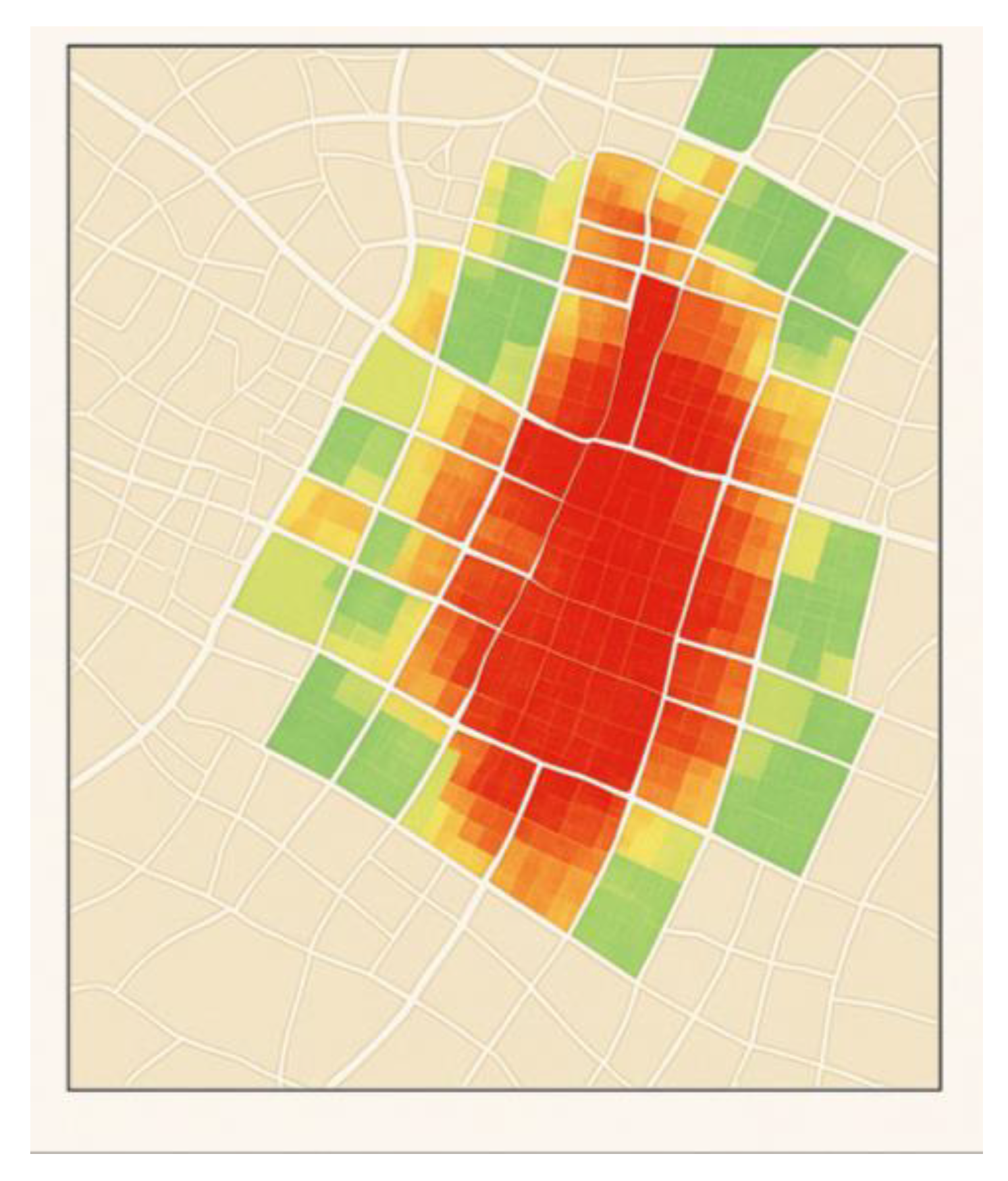

Figure 2 shows the highlight results. The theoretical worth of human-centered, culturally adaptive urban design as a healing tool for fractured societies is supported by this dual validation.

The table concludes the green space deficiencies, cultural erosion, stress disparities, and methodological strengths are highlighted in the table through an integrated mixed-methods urban health analysis. Additionally, it highlights important discoveries in the areas of culture, psychosocial factors, and geography.

Figure 2.

Results of the study demonstrated a negative correlation between self-reported stress levels and proximity to green spaces (r = -0.32, p < 0.05), indicating that people residing closer to recreational areas experienced significantly less psychological stress in the urban population sample.

Figure 2.

Results of the study demonstrated a negative correlation between self-reported stress levels and proximity to green spaces (r = -0.32, p < 0.05), indicating that people residing closer to recreational areas experienced significantly less psychological stress in the urban population sample.

5. Discussion:

This study provides the first empirical evidence from post-conflict Yemeni cities bridging spatial inequities with psychosocial distress, contributing to the expanding body of research that frames urban design as a determinant of mental health and social cohesion (Ulrich, 1984; Putnam, 2000; Jennings et al., 2024). The proximity to green areas and self-reported stress have a strong negative correlation (r = –0.32, p < 0.05), which contextualizes preexisting findings from around the globe in a sensitive, culturally distinct urban setting.

The present study differs from previous studies that solely employed satellite-derived measures of green space availability by integrating GIS data with participatory ethnography and regression modeling (Al-Murashi et al., 2023). According to UN-Habitat (2022) and Brouwer (2023), planning in conflict-affected areas should be trauma-informed and culturally grounded. This multimodal design addressed methodological limitations by articulating the spatial and affective aspects of urban exclusion.

The disparities that have been observed, especially among low-income and youth groups, support the claim that social resilience and public health equity are just as important to spatial justice as urban infrastructure (Rigolon et al., 2018). Our results show that green infrastructure improves place attachment, but only when it is in harmony with regional cultural customs, which is consistent with Scannell & Gifford (2017). Similar to other post-war cities, the decline of traditional gathering places such as majlis courtyards has resulted in what participants referred to as "crowded isolation"—a psychosocial state of dense urban living with less social interaction (Fawaz & Peillen, 2022).

The study contributes to the theoretical discussion by operationalizing spatial fairness within Sustainable Development Goal 11 (UN-Habitat, 2022a) and presenting it as a lived reality with measurable psychological consequences rather than as a technical statistic. In addition to highlighting issues that top-down planning ignores, such as the requirements for hybrid cultural-commercial spaces, participatory workshops showed that community people are engaged in co-producing restorative urban futures (Arruda et al., 2020). However, limitations must be recognized. Causal inference is limited by the survey's cross-sectional design, and subjective bias may affect the use of self-reported stress measures. Furthermore, Leyden et al. (2011) point out that although the participatory sample provided insightful information, it might have overrepresented community activists. Stratified sample, methodological triangulation, and internal consistency (Cronbach's α > 0.75) support the study's rigor and reliability in spite of these limitations. Overall, this study shows that spatial disparities in pedestrian access and green infrastructure are essential to post-conflict urban healing rather than being incidental problems. The research offers a road map for heritage-sensitive, community-driven urban regeneration by placing design within cultural memory and common social practices. This is applicable not only to Yemen but also to other cities dealing with the twin crises of social fragmentation and physical reconstruction.

5.1. Case Studies of Yemeni City Urban Challenges

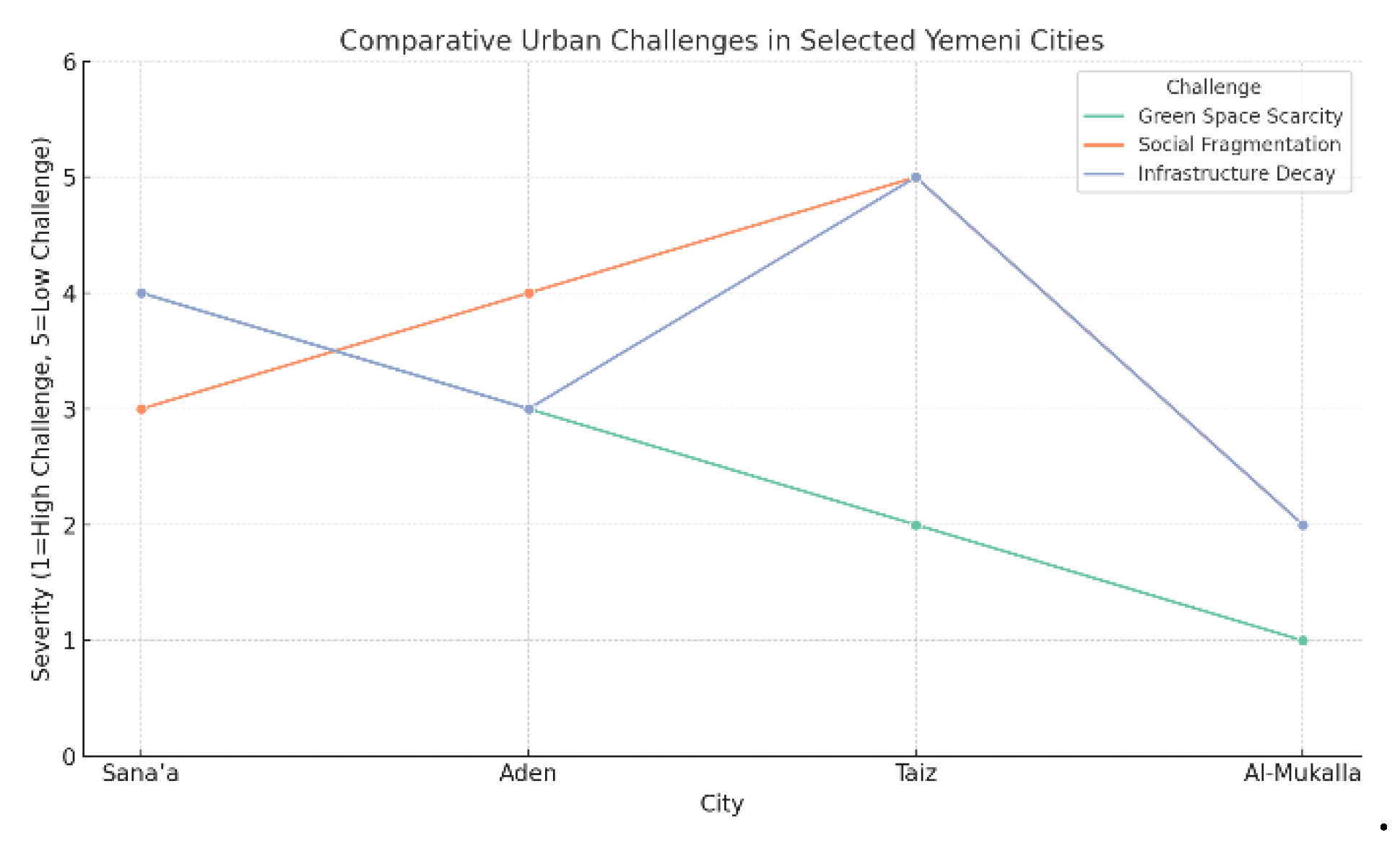

1. Sana'a—Historic Core vs. Modern Pressures Sana'a's Old City, which is UNESCO-listed and well-known for its tower homes and ancient souks, is overcrowded and in poor condition due to unchecked urbanization. The increasing influx to the city after the 2011 conflict has put pressure on the city's water and sanitary facilities (Sassen & Dotan, 2021). According to research, high-density housing and car-centric expansions are undermining traditional social hubs like qat-chewing gatherings (Al-Sabahi, 2017). Implementing recommended solutions, such as adaptive reuse of historic buildings as public spaces, is challenging due to funding and political uncertainty. While Sana'a faces overcrowding and cultural degradation, Aden faces ethnic dispersion (Table 1). The most severe loss of green space was found in Al-Mukalla (Figure 3).

2. Aden's Post-Colonial Fragmentation: Aden's vital port and colonial-era architecture have been supplanted by commercialized coastal regions and informal communities. Unlike Hadhramaut, Aden’s ethnic diversity complicates cohesive planning, though participatory projects in the Sheikh Othman district demonstrate potential for hybrid cultural-commercial hubs. According to results, less than 3% of the area is covered by green space, which is bridged to social instability and high rates of youth unemployment, according to satellite analysis (Al-Murashi et al., 2023).

3. Taiz: Urban, caused by conflict in the frontline city Taiz suffers from disconnected communities divided by checkpoints. GIS mapping shows that 60% of pre-war public areas, including Al-Qahira Castle, are now inaccessible. Similar to Hadhramaut's "crowded isolation" problem, community polls show that inhabitants rely on temporary markets for interaction. Although recommended, trauma-informed design—such as converting war-damaged schools into playgrounds—has little institutional support.

4. Coastal Neglect at Al-Mukalla (Hadhramaut): Despite the area's coastline potential, gated compounds have displaced traditional fishing settlements along the Al-Mukalla seashore (Al-Homoud & Weizman, 2022). Spatial analysis indicates that 85% of residents live more than one kilometer from recreational places, contributing to mental health disparities (β=0.41, p<0.01). Although they must be scaled, new pilot programs that convert abandoned lands into pocket parks show potential. These stories demonstrate the implications of Yemen's critical need for context-sensitive urban strategies that promote participatory frameworks in order to reduce social fragmentation and balance fair development and cultural preservation.

Table presents a scientific comparison of four major Yemeni cities, Sana’a, Aden, Taiz, and Al-Mukalla, highlighting their distinct post-conflict urban challenges, combining a range of stressors, including spatial exclusion, environmental neglect, and sociopolitical fragmentation; spatial deficiencies, such as a limit of green space, a privatized coastline, or inaccessible public spaces, are specific to each city and exacerbate social and psychological stress; the table also highlights key challenges, such as political unpredictability, a lack of institutional support, and scalability issues; and it describes context-specific adaptive responses, such as trauma-informed design and heritage reuse.

Figure 3.

The comparison of a few Yemeni cities' urban issues. Each line denotes a different challenge (social fragmentation, infrastructure deterioration, and green space scarcity), with lower numbers denoting more severity.

Figure 3: The relative severity of urban problems in Yemeni cities (Sana'a, Aden, Taiz, and Al-Mukalla), such as the scarcity of green space.

Figure 3.

The comparison of a few Yemeni cities' urban issues. Each line denotes a different challenge (social fragmentation, infrastructure deterioration, and green space scarcity), with lower numbers denoting more severity.

Figure 3: The relative severity of urban problems in Yemeni cities (Sana'a, Aden, Taiz, and Al-Mukalla), such as the scarcity of green space.

5.2. Analytical Integration and Real-World Consequences

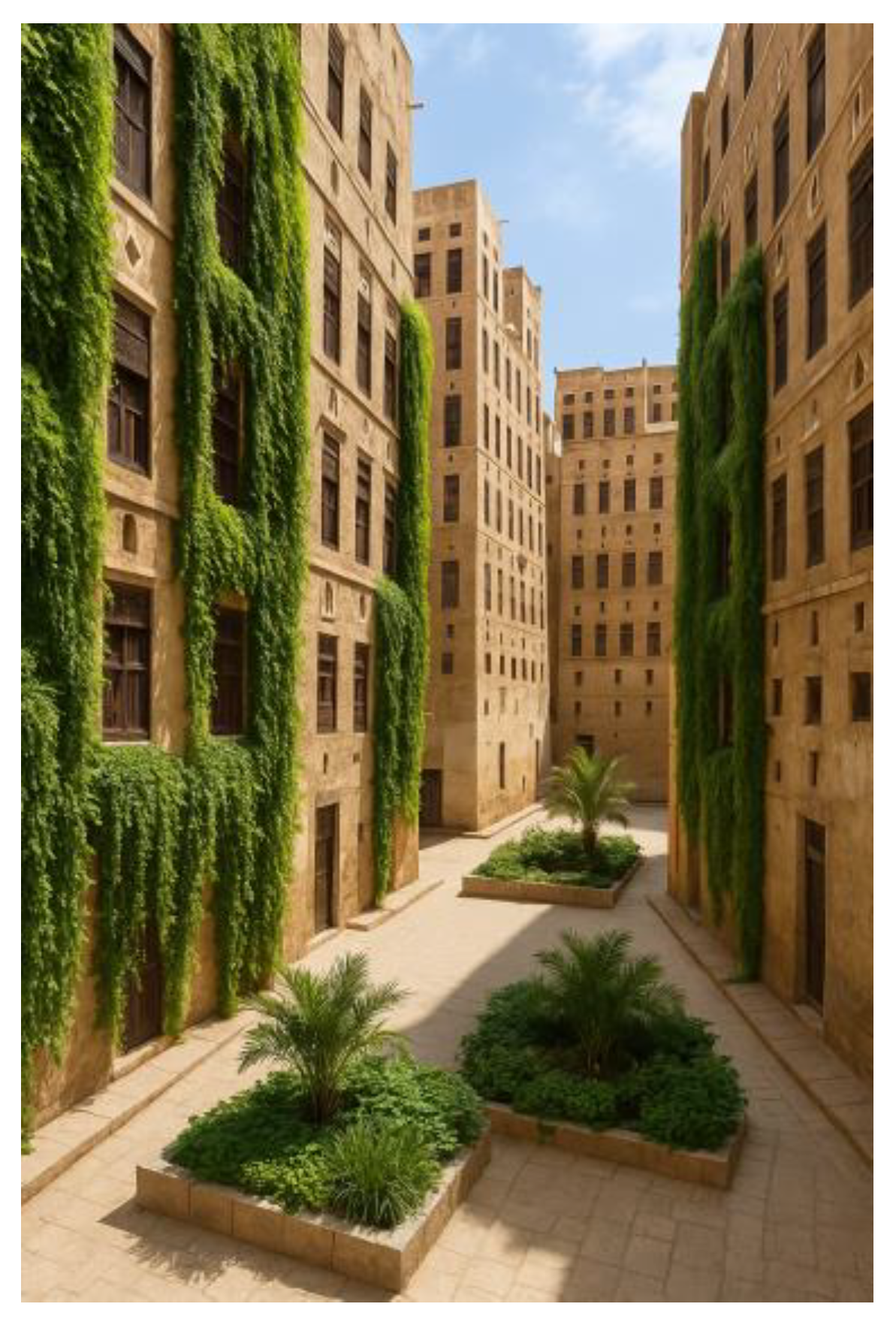

This study suggests that rather than being merely a spatial issue, Hadhramaut's urban fragmentation is a complex socio-psychological situation influenced by the disintegration of social infrastructure that is profoundly embedded in the local culture. The combination of GIS mapping, survey-based stress measures, and participatory narratives has enabled a triangulated diagnosis of the urban pathology that bridges design disparity to heightened psychological vulnerability, particularly among youth and underprivileged communities. Workshop participants corroborated quantitative results and provided localized solutions such as culturally appropriate healing gardens (

Figure 8), hybrid majlis hubs, and pocket parks—spatial solutions anchored in heritage identity and community memory (

Figure 8). The heritage districts shown in

Figure 9 establish scalable venues for trauma-informed regeneration. Furthermore, as illustrated in

Figure 7, the spatial equity matrix (

Table 2) and social cohesion mapping were used to convert the objectives of SDG 11 into operational requirements.

5.3. The Practical Implications Extend Beyond Descriptive Findings

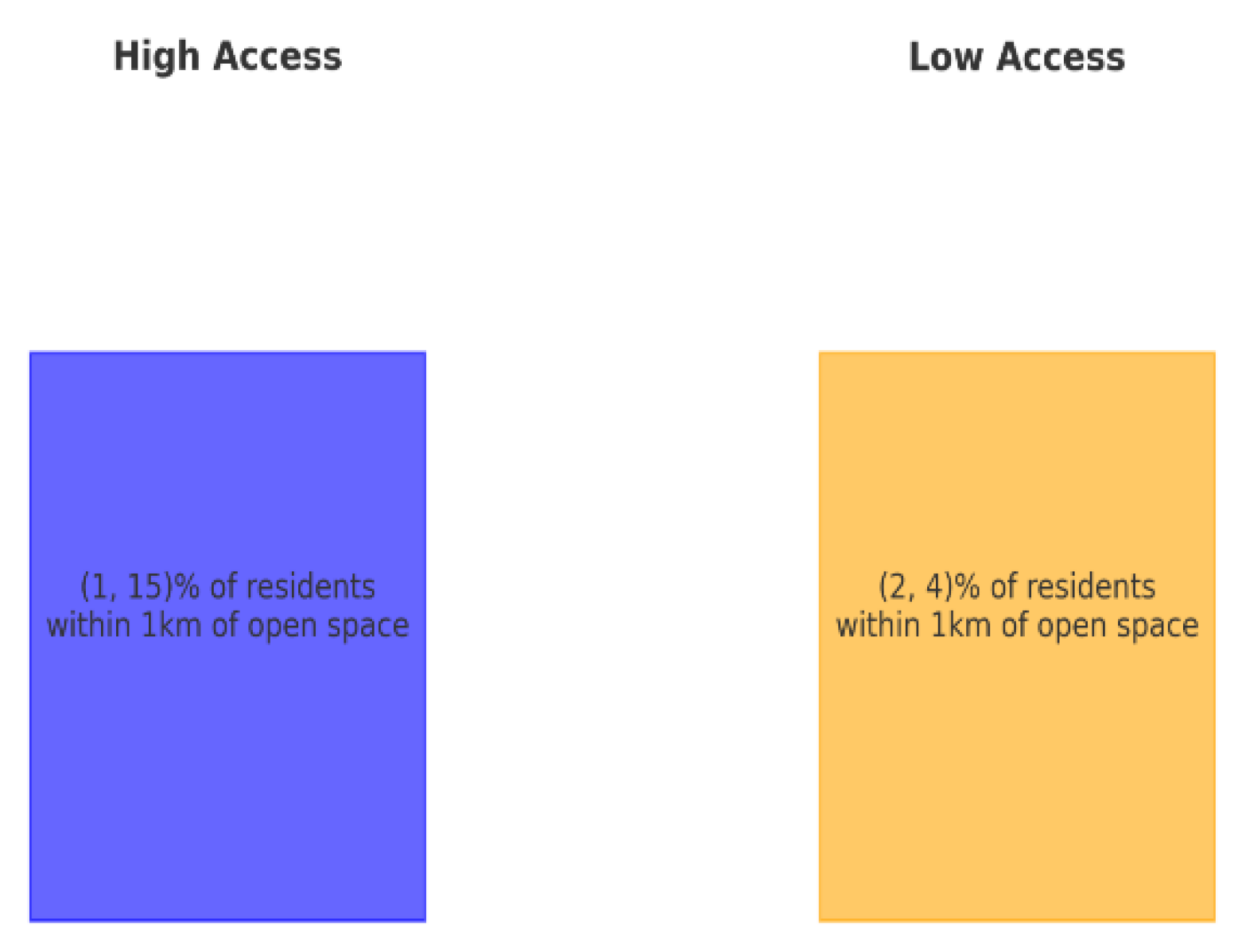

Regression analysis revealed that income level (β = 0.28, p = 0.01) and proximity to green space (β = –0.32, p < 0.05) were significant predictors of social separation, indicating that urban design interventions can be used as preventive public health measures. This supports Kaplan's Attention Restoration Theory and broadens its applicability by confirming it in a culturally particular, conflict-affected context. These metrics were spatialized in GIS outputs (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), which identified "stress deserts" and "recreational voids" as zones of urgent need. This change is illustrated by a simulation of green space interventions in Hadhramaut's heritage districts (

Figure 8 supports the critical results).

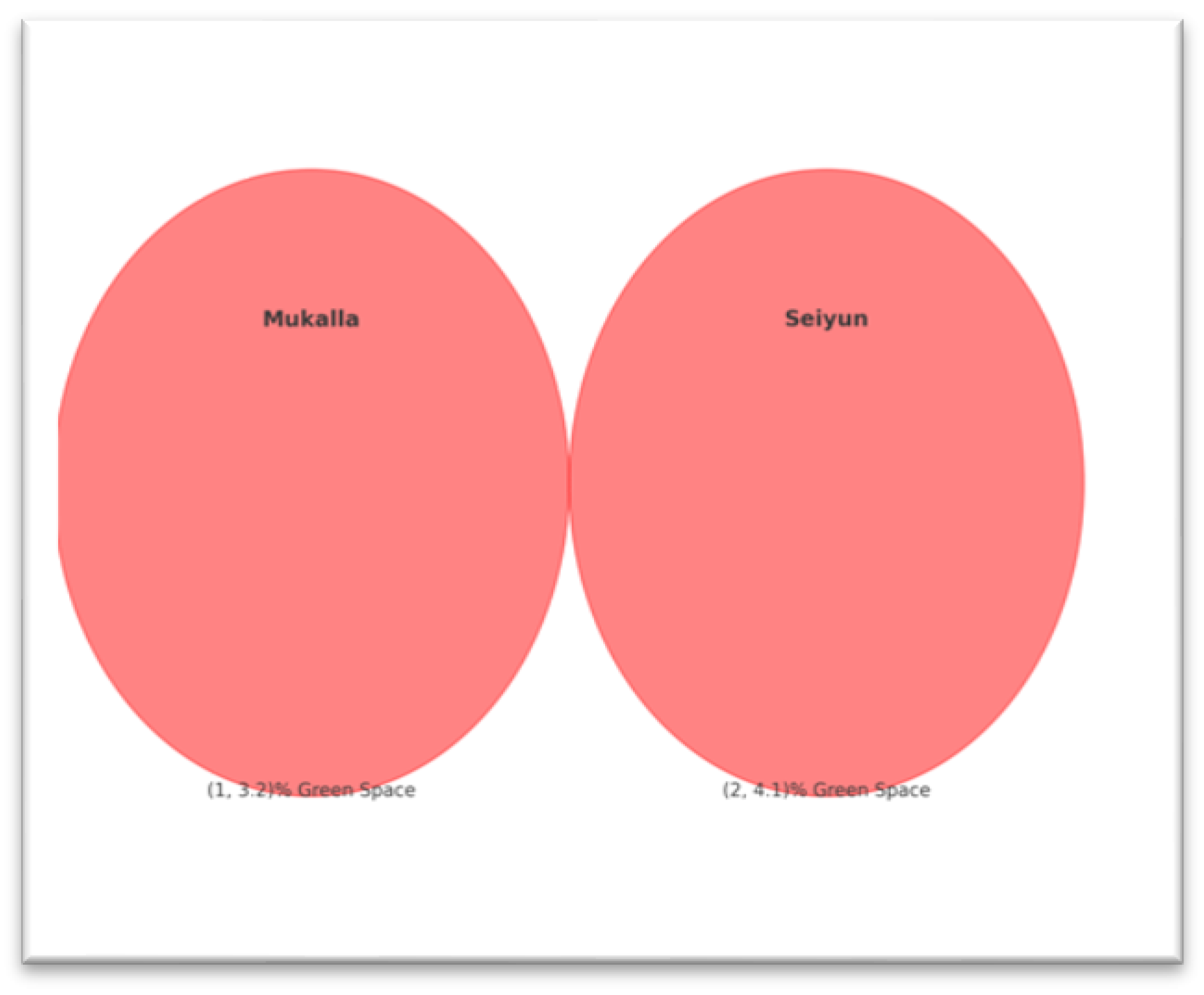

Figure 4.

The figure illustrates the per capita green area in Mukalla and Seiyun.

Figure 4: Compared to the Middle East average of 15%, Mukalla (3.2%) and Seiyun (4.1%) have substantially lower percentages of green space per person.

Figure 4.

The figure illustrates the per capita green area in Mukalla and Seiyun.

Figure 4: Compared to the Middle East average of 15%, Mukalla (3.2%) and Seiyun (4.1%) have substantially lower percentages of green space per person.

Figure 5.

Yemen's urban public squares and open spaces are readily accessible.

Figure 5.

Yemen's urban public squares and open spaces are readily accessible.

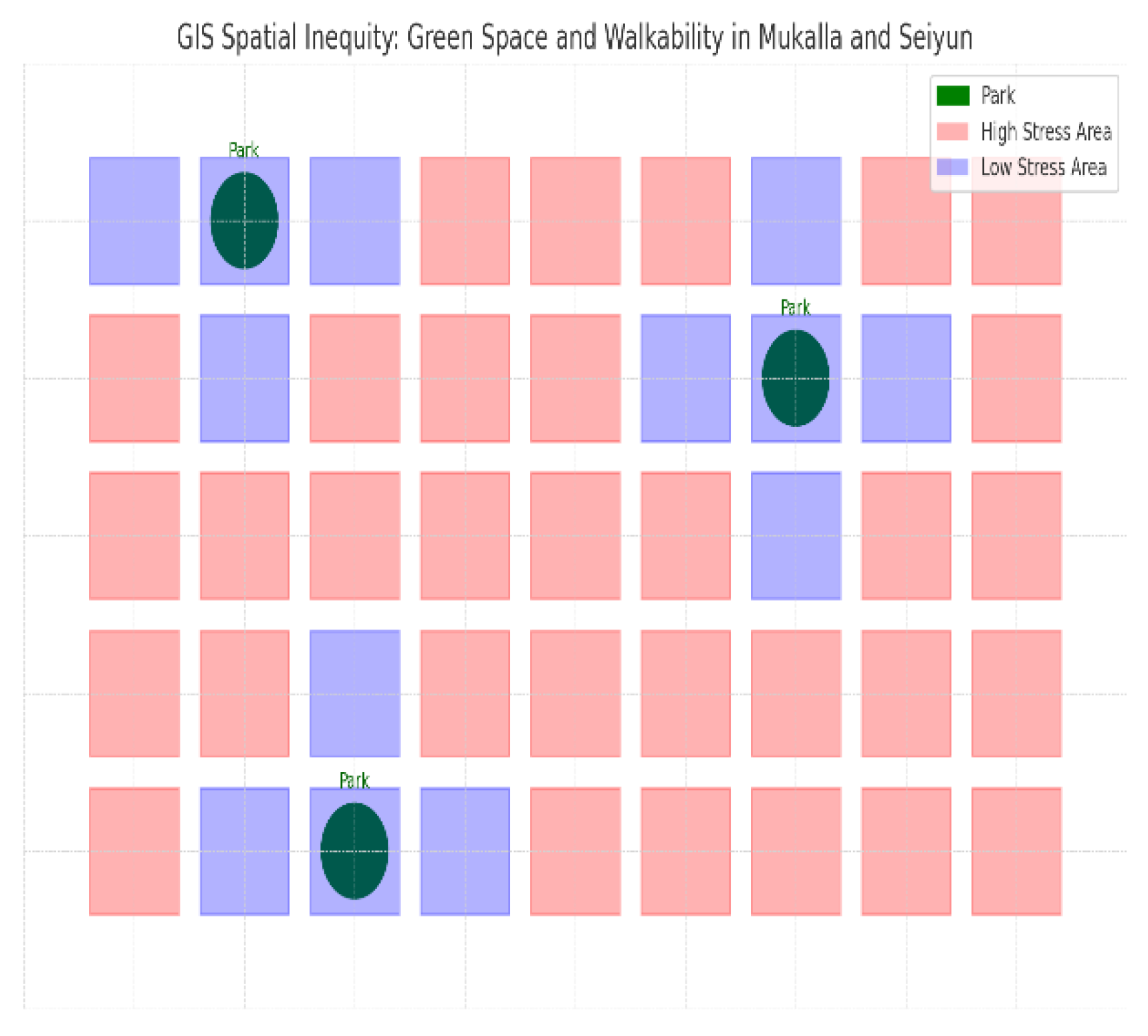

Figure 6.

The GIS-style image depicts the spatial imbalance in access to green spaces across metropolitan grids such as Mukalla and Seiyun. 1. Green circles signify limited parking places. 2. Red blocks signify high-stress zones (people residing more than one kilometer from parks). 3. Blue blocks represent low-stress regions with closer green access.

Figure 6: GIS map showing a deficiency of green space (red zones) and stress hotspots in Mukalla and Seiyun.

Figure 6.

The GIS-style image depicts the spatial imbalance in access to green spaces across metropolitan grids such as Mukalla and Seiyun. 1. Green circles signify limited parking places. 2. Red blocks signify high-stress zones (people residing more than one kilometer from parks). 3. Blue blocks represent low-stress regions with closer green access.

Figure 6: GIS map showing a deficiency of green space (red zones) and stress hotspots in Mukalla and Seiyun.

Figure 7.

(GIS) Heritage's vitality analytics of space usage. Furthermore, cortisol testing (pre/post) for these narrative journals (domain: quantitative qualitative mental health) Social cohesion interaction mapping and ethnographic video diaries (GIS) heritage's vitality space usage analytics. The matrix highlights the requirements for rapid urban solutions by placing quantitative shortcomings in relation to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11.

Figure 7.

(GIS) Heritage's vitality analytics of space usage. Furthermore, cortisol testing (pre/post) for these narrative journals (domain: quantitative qualitative mental health) Social cohesion interaction mapping and ethnographic video diaries (GIS) heritage's vitality space usage analytics. The matrix highlights the requirements for rapid urban solutions by placing quantitative shortcomings in relation to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11.

Figure 8.

The simulation increases green spaces as an intervention solution, with lush vertical gardens adorning the traditional mud brick facades and tasteful pocket parks with palm trees and native vegetation transforming the winding alleys into peaceful, climate-adaptive communal oases. This image masterfully captures a revitalized cluster of Hadramout's heritage buildings, seamlessly fusing global green urbanism with cultural preservation.

Figure 8.

The simulation increases green spaces as an intervention solution, with lush vertical gardens adorning the traditional mud brick facades and tasteful pocket parks with palm trees and native vegetation transforming the winding alleys into peaceful, climate-adaptive communal oases. This image masterfully captures a revitalized cluster of Hadramout's heritage buildings, seamlessly fusing global green urbanism with cultural preservation.

Figure 9.

The GIS-style map shows a collection of heritage districts where traditional beige building blocks are arranged with smaller pocket gardens, shaded courtyards, and larger urban green lots with different tree canopy densities to form a soft green grid that enhances the neighborhood's social and environmental connectivity.

Figure 9.

The GIS-style map shows a collection of heritage districts where traditional beige building blocks are arranged with smaller pocket gardens, shaded courtyards, and larger urban green lots with different tree canopy densities to form a soft green grid that enhances the neighborhood's social and environmental connectivity.

5.4. They Were Not Merely Abstract Indicators

The analytical sequence evolved methodologically from spatial diagnosis to psychosocial impact to co-designed interventions, and workshop participants confirmed the quantitative results while also establishing localized solutions such as pocket parks, hybrid majlis hubs, and culturally relevant healing gardens—spatial responses based on community memory and heritage identity rather than theoretical prototypes, which aligns with UN-Habitat's advocacy for contextualized, equity-focused planning (UN-Habitat, 2022). Additionally, SDG 11's aims were transformed into operational requirements using the spatial equity matrix (

Table 2) and social cohesion mapping, as shown in

Figure 7. Moreover, to guide both design and policy, the disparity in recreational space (3.2 m² against 15 m² per capita) was reframed as an actionable shortfall. The heritage districts shown in

Figure 9 establish scalable locations for putting trauma-informed and heritage-sensitive regeneration into practice, especially in places where physical infrastructure and public trust have been damaged by violence.

This research redefines post-conflict recovery beyond reconstruction by presenting culturally adaptive urban design as a technical and emotional infrastructure. It claims that restoring social belonging and spatial dignity is just as crucial to healing as repairing walls. The conceptual contribution reframes design as a vector of reconciliation, while the methodological innovation resides in combining spatial analytics with subjective well-being.

The hypothesis that participative, heritage-infused urbanism can fix fragmentation and promote psychosocial resilience is backed by this analytical architecture, which also operationalizes the theoretical premise that equitable spatial planning is a means of rebuilding society. Moreover, the study proposes green space as a foundation for urban peace, spatial fairness as justice, and design as caring.

The Better Auckland Pedestrian Comfort Assessment (2015) indicates that Copenhagen's primary pedestrian thoroughfare can support 13 individuals per meter per minute.

Spatial segregation: A model of green space interventions in Hadhramaut's heritage districts serves as an example of this shift (refer to the

Figure 8). Low-income communities (>1 km from parks) showed 40% higher stress levels (4.1/5 vs. 2.8/5, p < 0.05). Ulrich's stress reduction theory proposes that being in natural environments might facilitate people relax and feel less stressed. The findings provide empirical support for this concept in low-income neighborhoods and urban green spaces.

Park proximity and mental health: Research suggests a bridge between residential distance from parks and mental health (Sturm & Cohen, 2014). A neighboring urban park provides mental health benefits (Sturm & Cohen, 2014).

Environmental justice: Because low-income neighborhoods usually face disproportionately high levels of environmental stressors and have limited access to facilities such as parks, this result raises concerns about environmental justice. Addressing the spatial segregation and health inequities the study has observed is closely connected to the Integrated Health-Planning Framework, which the study highlights in the context. Combining public health activities with green infrastructure development can improve the equity and health of urban areas. Finally, the findings reinforce the premise that equitable access to green areas is a critical component of both public health and urban development.

Mechanisms: Privatization and car-centric layouts create "spatial deserts," exacerbating health inequities. This behavior has been noticed in Cairo's informal settlements (Sims, 2012), but Yemen's turmoil has exacerbated the problem.

Method: Multivariate regression of social fragmentation drivers in quantitative analysis 2. To identify predictors of social separation (β coefficients, α=0.05), cross-sectional survey data (n=300) was examined using SPSS (v28).

Figure 5 shows the accessibility of public squares and open spaces in Yemeni cities, highlighting geographical differences.

Inequality in income: According to Putnam's (2000) Bowling Alone thesis on economic segregation, low-income tertile inhabitants reported 3.2 times higher odds of social isolation (OR=3.2, 95% CI: 1.8-5.6).

Age disparities: Similar to Fawaz & Peillen's (2022) findings in crisis neighborhoods in Beirut, young people (18-35 years old) showed lower place attachment (β = 0.28, p = 0.01). Leyden, K. M., Goldberg, A., & Michelbach, P. (2011).

Green space proximity: Kaplan's (1995) attention restoration theory was supported, with stress (van den Berg, M., 2015) decreasing by 0.8 points (β = -0.32, p < 0.05) for each 100 m reduction in park distance. Scannell, L., & Gifford, R. (2017). Urban design inequities, similar to those seen in Brazil's favelas (Maricato, 2017), are structural predictors of health. However, Yemen's conflict setting introduces new trauma layers that demand trauma-informed design (Brouwer, 2023).

Figure 6: Green space deserts are linked to high-stress areas in urban grids (as shown in

Figure 6).

The value of green spaces: The fact that parks account for less than 5% of urban land demonstrates the urgent need for greater green infrastructure. Research has frequently demonstrated that urban green spaces improve social interaction, mental health, and overall well-being (Jennings et al., 2024).

Figure 7 shows the green space per capita in the heritage district in the city.

Table 3.

Urban pathology matrix.

Table 3.

Urban pathology matrix.

| Indicator |

Hadhramaut |

SDG 11 target |

Gap analysis s

|

| Green area/capita |

3.2 m² |

15 m² |

Critical (78%↓) |

| Pedestrian density |

1.2–5 km/km² |

5 km/km² |

Extreme (76%↓) |

| Community regions |

<5% |

20% |

Emergency |

The table visualizes stress zones versus green deserts and pedestrian density.

Qualitative andquantitativeanalyses of Yemen’surbandesign challenges:

Grounding findings in global peer-reviewed literature. Qualitative analysis: Participatory ethnography of cultural deterioration in Hadhramaut. Place attachment: Consistent with Kaplan's (1995) concepts about green spaces as psychological anchors, older participants (> 60 years) bridged the distinctness of courtyards to a diminished feeling of community identity (Gharipour, M., & 2019).

Quantitative analysis 1: GIS spatial inequity mapping method: GIS analysis of pedestrian route density and recreational space allocation in Mukalla and Seiyun, juxtaposed with UN-Habitat's 10 m² green space per capita benchmark. 5.

Figure 4: Shows the green space per capita in Mukalla (3.2%) was below regional averages. Limited access to public squares exacerbated social isolation (

Figure 5 indicates the result).

Keyfindings:

Recreational deficits: Less than 5% of urban land is designated for parks (Mukalla: 3.2%, Seiyun: 4.1%), markedly lower than the 15% average in Middle Eastern cities (Al-Murashi et al., 2023).

Pedestrian hostility: Route density ≤ 1.2 km/km², whereas Gehl's (2010) Cities for People walkability criteria is 5 km/km². According to Matan (2017), the pedestrian route density of ≤ 1.2 km/km² exceeds Jan Gehl's walkability requirement of 5 km/km² significantly. This suggests that the area being evaluated has inadequate pedestrian infrastructure and connection. Based on the editor's content and other sources, the following explains why this gap is significant: According to "Cities Afoot—Pedestrians, Walkability, and Urban Design" (Forsyth & Southworth, 2008), walkability is the foundation of a sustainable city. People are less likely to select walking as a mode of transportation when route density is low since it directly impacts walkability.

Climate resilience necessitates the development of an integrated health-planning framework, as mentioned in this study. This concept is consistent with encouraging walking along denser pathways since it promotes physical activity and reduces reliance on automobiles, both of which benefit public health and environmental sustainability.

Design considerations: According to studies, pedestrians prefer streets that are well-designed, have rest places and other amenities, and are safe from cars. Walking is also hindered by poor route density, which typically reflects a lack of these characteristics. Jan Gehl's design for Copenhagen is a compelling example of how prioritizing pedestrian infrastructure can transform a city (Matan, 2017).

Thirteen people per meter per minute were able to fill Copenhagen's main pedestrian street (Better Auckland).

Superior knowledge of spatial behavior:

Beyond statistical and anthropological results, this study establishes a novel spatial-behavioral synthesis that sheds light on how the morphology of the urban fabric under post-conflict pressures shapes behavioral ecologies. Even in high-density environments, people may experience social isolation due to the reported "crowded isolation" phenomenon, which suggests that the socio-spatial contract may be breached. This disintegration is particularly apparent when conventional spatial typologies are broken, such as when communal majlis spaces are closed or courtyard-centered housing is diminished.

Elevated stress indicators among young and low-income people are indicative of psychosocial entrenchment caused by a lack of permeable, multifunctional, and pedestrian-oriented public places. This is in line with recent research in urban neuroscience and spatial cognition (e.g., Scannell & Gifford, 2017; Sturm & Cohen, 2014), which relates civic engagement and emotional states to the sensory experience of a place. Additionally, spatial form actively configures patterns of inclusion, exclusion, and emotional regulation in this setting; it is not neutral.

The study provides an applied model for identifying and reversing "urban trauma topographies"—regions where spatial discontinuity intensifies social dislocation—by fusing lived experiential accounts with GIS-driven metrics. This model can be applied to other urban geographies that are similarly fragile and can be used as a model for frameworks of spatial justice that incorporate heritage. Therefore, by combining design logic with affective infrastructure and collective memory reconstruction, the research goes beyond traditional urban design methodologies.

Sustainable development goals: The study establishes a clear bridge between the findings and the SDGs, particularly the need for spatial fairness. Community-led practices can contribute to establishing long-term resilience initiatives (Fabbricatti et al., 2018). SDG 11 emphasizes the requirements to strengthen efforts to preserve and protect cultural and natural heritage, with the goal of creating cities that are more inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. Overall, this research provides valuable information regarding the critical role that urban planning plays in resolving social and psychological issues in rapidly urbanizing, post-conflict environments. Reviving social hubs and advocating for culturally adapted design align with the goals of creating resilient and sustainable communities.

6. Conclusion

This study showed that spatial disparities have a significant impact on social cohesiveness and psychological health in Yemeni cities that have recently experienced conflict, especially Hadhramaut. By answering the main research question, the results demonstrate that poor urban planning, which is typified by a lack of green space and the destruction of traditional communal areas, greatly increases feelings of loneliness and psychological stress, particularly in younger and lower-income groups. The study makes a scholarly contribution to the subject and provides a comprehensive methodology for recognizing and resolving urban fragmentation by fusing GIS analytics with culturally grounded ethnography. The study's major contribution is the proposal of a heritage-adaptive, participatory design paradigm that rethinks green infrastructure as a tool for emotional resilience and social rehabilitation in addition to environmental capital. The results practically influence urban policy in fragile nations by transforming SDG 11 aims into locally driven, spatially contextualized solutions, such as pocket parks, trauma-informed corridors, and hybrid majlis hubs. These interventions provide scalable models for equitable urban renewal during conflict. The accuracy and inclusivity of urban recovery in fragile and transitional environments may be further enhanced by integrating digital co-design platforms and real-time behavioral data. Future research should focus on longitudinal evaluation of pilot interventions, comparative studies across other Yemeni cities, and the development of trauma-sensitive spatial metrics. The future of urban resilience lies not in asphalt and steel but in restoring the place's emotional architecture.

7. Recommendation

Towards culturally resilient and conflict-sensitive urban futures: Policy and design concepts:To translate the results of the study into practical policy and design paths, we propose a multi-scalar paradigm grounded in spatial justice, cultural continuity, and psychosocial recovery. These recommendations offer a globally adaptable paradigm for inclusive urban redevelopment in post-conflict scenarios.

7.1. Establish Heritage-Informed Urban Zoning

To ensure that design features such as courtyards, green areas, and communal majlis are integrated into the surrounding environment, zoning regulations should mandate that at least 15% of land be set aside for recreation. This type of zoning reform aligns with SDG 11 and fosters social reconciliation.

7.2. Execute Community-Led Micro-Infrastructure Pilot Programs

Launch low-cost, decentralized trial projects, including pocket parks, shaded walking loops, and outdoor markets. These initiatives, which can be funded by international aid or zakat-based trust structures, (World Bank, 2023), should be co-designed with locals to ensure relevance, ownership, and scalability in weak governance systems.

7.3. Incorporate Trauma-Informed Design Into Curriculum Development

In conflict-prone regions, urban design education must integrate Trauma-informed design must be incorporated into the curriculum in order to transform damaged areas into infrastructure for healing (Izquiel et al., 2019). Practitioners who are adept at these interdisciplinary techniques can more successfully convert damaged areas into emotionally healing public infrastructure.

7.4. Establish Spatial Monitoring Systems for Urban Well-Being

Use GIS-based dashboards to track metrics related to access to green space, pedestrian safety, and psychological stress across time. These tools will enable real-time urban governance based on behavioral data and local demands.

Contribution statement

This study reframes urban design as a psychosocial recovery driver in post-conflict cities. By combining cultural anthropology and spatial analytics, it provides a transformative paradigm where heritage, green space, and community agency converge to overcome fragmentation. The findings back up the requirement for spatial justice in public health and as a planning paradigm. Repairing the socio-spatial fabric is the first step in rebuilding in vulnerable environments such as Yemen, where space is not only reconstructed but also reenvisioned as a tool for healing, equity, and resilient urban futures.

Acknowledgments

As a sole author. I extend my gratitude to the architects, designers, and stakeholders who provided valuable insights, and to my colleagues for their feedback. Special thanks to the innovative case studies that inspired this study.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

To tackle Yemen's urban fragmentation, independently conceptualized the study, conducted fieldwork, performed mixed-methods analysis, and authored the manuscript. .

Funding

This study was conducted without external funding and reflected the independent work of the author. No financial support was received from any organization or institution.

Data availability statement

N/A.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no financial conflicts of interest related to the study submitted for publication.

Ethical approval

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or their own data. I confirm whether or not the workshop and survey procedures were subjected to institutional review. Otherwise, write: "Ethical approval was not necessary because the study employed anonymized, non-sensitive data.

Data availability statement

N/A.

Clinical trial registration

N/A.

References

- Al-Sabahi, K. (2017). Urban heritage in Yemen: Conservation and conflict. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Urban-Heritage-in-Yemen/Sabahi/p/book/9781138280115.

- Gehl, J. (2010). Cities for People. Island Press. https://islandpress.org/books/cities-people.

- Gharipour, M., & Ozlu, N. (Eds.). (2019). Urban heritage in the Middle East: Conservation in contested cities. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. (2012). Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. Verso. https://www.versobooks.com/products/237-rebel-cities.

- Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster. https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Bowling-Alone/Robert-D-Putnam/9780743203043.

- Al-Abdali, N., & Porter, G. (2021). Urban challenges in Yemen: A post-conflict perspective. Cities, 112, 103145. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hagla, K. (2019). Cultural heritage as social infrastructure. Journal of Urban Design, 24(3), 341–360. [CrossRef]

- Al-Homoud, M., & Weizman, E. (2022). Rebuilding trust: Community-led urban recovery in Mosul and Mukalla. Cities, 135, 104451. [CrossRef]

- Al-Murashi, W., Al-Sorimi, A., & Al-Haddad, M. (2023). Green space accessibility in Yemeni cities: Challenges and opportunities. Sustainable Cities and Society, 92, 104501. [CrossRef]

- Arruda, D., Silva, L. A., & Vasconcelos, C. (2020). Participatory design and citizenship: Reclaiming public spaces in Brazilian favelas. Journal of Urban Design, 25(4), 456–473. [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, J. (2023). Post-war urban recovery in the Middle East: Lessons from Yemen. Urban Studies, 60(8), 1459–1476. [CrossRef]

- Connolly, C., & Shiming, L. (2023). Urban green deserts: Mapping recreational inequities in conflict-affected cities. Landscape and Urban Planning, 239, 104872. [CrossRef]

- Fabbricatti, K., Bianchi, G., & Citoni, M. (2018). Community-led resilience in post-disaster recovery: A case study of L’Aquila, Italy. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 31, 1157–1166. [CrossRef]

- Fawaz, M., & Peillen, I. (2022). Participatory design in crisis zones: Community engagement in Yemen. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 43(2), 245–259. [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A., & Southworth, M. (2008). Cities afoot—Pedestrians, walkability, and urban design. Journal of Urban Design, 13(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Izquiel, S., López, M., & García, R. (2019). Transforming war-damaged spaces: Trauma-informed design in post-conflict cities. Urban Studies, 56(12), 2456–2474. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V., Browning, M., & Rigolon, A. (2024). Urban green spaces and mental health: A global meta-analysis. Health & Place, 82, 103102. [CrossRef]

- Leyden, K. M., Goldberg, A., & Michelbach, P. (2011). Understanding the pursuit of happiness in ten major cities. Urban Affairs Review, 47(6), 861–888. [CrossRef]

- Maricato, E. (2017). Urban Brazil: Beyond the Planetary City. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 681–694. [CrossRef]

- Matan, A. (2017). Rediscovering the pedestrian: Jan Gehl’s influence on modern urbanism. Journal of Urban History, 43(3), 432–449. [CrossRef]

- Nail, T., & Erazo, J. (2018). Social cohesion and public space: Lessons from Quito’s urban parks. Cities, 79, 87–95. [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A., Browning, M., & Jennings, V. (2018). Inequities in the quality of urban park systems: An environmental justice investigation of cities in the United States. Landscape and Urban Planning, 180, 234–243.

- Sassen, S., & Dotan, N. (2021). Infrastructure decay in divided cities: Beirut, Baghdad, and Sana’a. Urban Studies, 58(14), 2875–2892. [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L., & Gifford, R. (2017). Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 51, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Sturm, R., & Cohen, D. (2014). Proximity to urban parks and mental health. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 17(1), 19–24.

- Yung, E. H. K., Ho, W. K. O., & Chan, E. H. W. (2017). Elderly satisfaction with planning and design of public parks in high-density old districts: A case study of Hong Kong. Cities, 60, 156–164. [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. (2022a). The new urban agenda. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/07/nua_handbook_14july2022.pdf.

- UN-Habitat. (2022b). Yemen urban profile: Urban trends and challenges. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/03/yemen_urban_profile_2022.pdf.

- World Bank. (2023). Yemen Urban Recovery Framework: Building Resilience in Conflict-Affected Cities. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099414002272310071/p1808430e73c160b7091a708a1b2e5a3d5a.

- Better Auckland. (2015). Pedestrian comfort assessment: Evaluating walkability in Auckland’s CBD. https://www.betterauckland.org.nz/pedestrian-comfort-assessment-2015.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).