Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

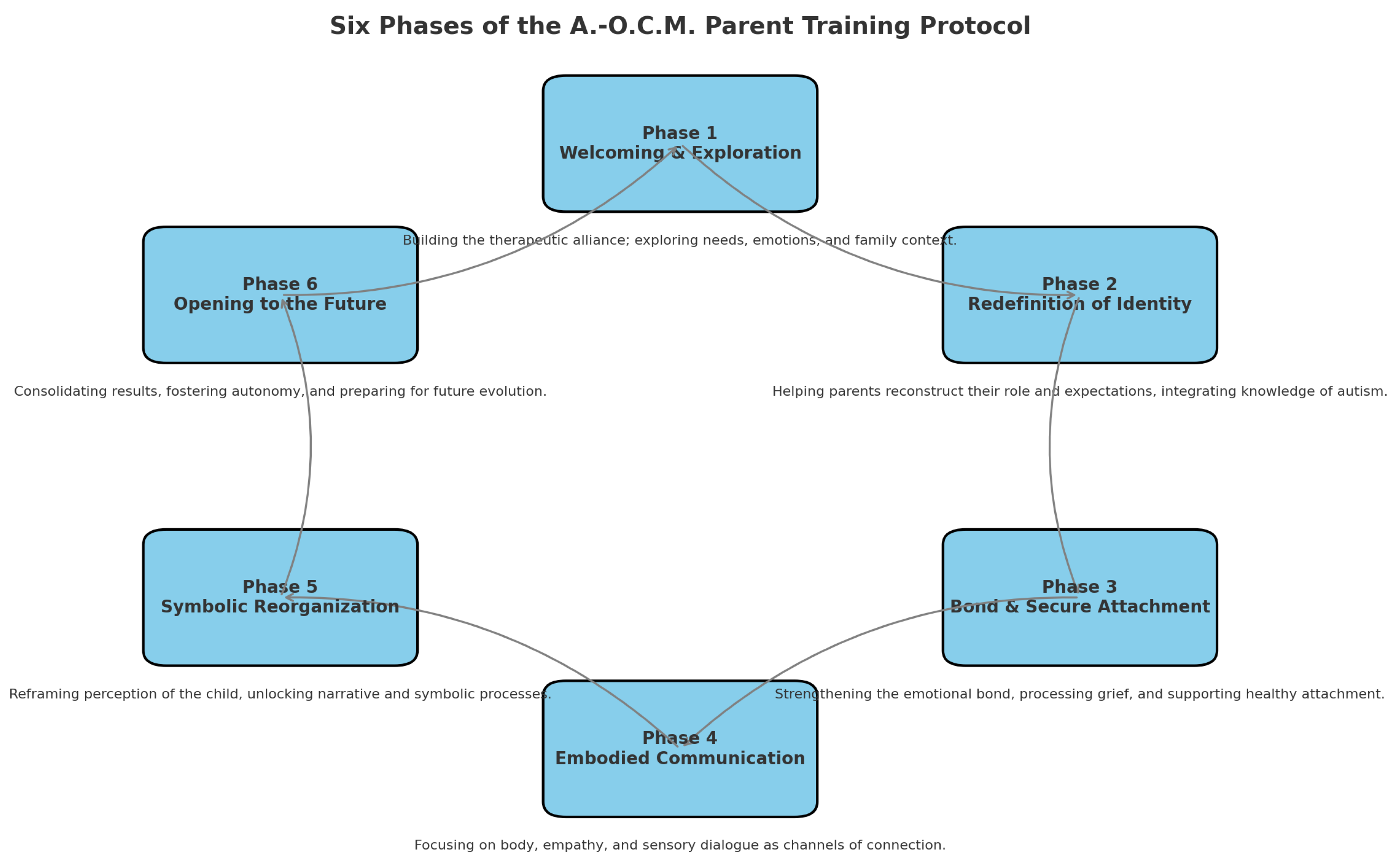

Phases of the Protocol

- 1.

- Welcoming and Context Exploration Phase

- 2.

- Redefinition of Parental Identity and Expectations Phase

- 3.

- Support for the Affective Bond and Secure Attachment Phase

- 4.

- Integration of the Body, Empathy, and Embodied Communication Phase

- 5.

- Symbolic Reorganization and Shared Narrative Phase

- 6.

- Closure and Opening to the Future Phase

Phases and Transformative Nodes

Clinical Fragments – Case 1. Family A

- Phase 1

- -

- Node 1 (Non-integrated parental self) – in the discontinuity of the parental role and in the alternation between involvement and detachment.

- -

- Node 5 (Denied relational need) – in the implicit refusal of emotional support and in minimizing fatigue.

- -

- Node 6 (Failure as identity) – in associating the child’s difficulties with perceiving themselves as “bad” parents.

- -

- Node 13 (Who am I now?) – in the identity disorientation and fracture of the parental role after the diagnosis.

- Phase 2

- -

- Node 2 (Control as defense against chaos) – in the difficulty tolerating uncertainty and the need to contain change.

- -

- Node 11 (Ideal image that cancels the real child) – implicit in delegating to the children the realization of the parental ideal.

- -

- Node 16 (Desire for normality) – underlying rigid expectations.

- -

- Node 18 (Punitive index) – in the tendency to place responsibility for change on the children.

- Phase 3

- -

- Node 7 (Reactive attachment) – alternation between affection and implicit threat.

- -

- Node 12 (Child as a space interposed between parents) – in the indirect triangulation related to rules.

- -

- Node 17 (Rejection of need) – in the difficulty accessing parental vulnerability.

- Phase 4

- -

- Node 4 (Disembodied empathy) – tendency to manage interactions cognitively rather than affectively.

- -

- Node 20 (Out-of-sync rhythm) – difficulties in co-regulating during interactions.

- -

- Node 21 (Blocked gesture) – in restraining bodily expressiveness.

- -

- Node 24 (Interrupted sensory dialogue) – in the limited openness to non-verbal channels.

- Phase 5

- -

- Node 3 (Fragmented perception of the child) – initially present and progressively reduced.

- -

- Node 14 (Blocked narrative of the relationship) – progressively unlocked through shared feedback.

- -

- Node 15 (Repressed impulsivity) – in the more balanced management of emotional reactions [14].

- Phase 6

Results

Prompt Stratification

- Prompt 1

- 1. The non-integrated parental self

- 5. The denied relational need

- 6. Failure as identity

- 13. Who am I now?

- Prompt 2

- Prompt 3

- Prompt 4

- Prompt 5

- Prompt 6

Operational Implications for Protocol Implementation

Clinical Fragments – Case 2 – Family B

- Phase 1

- -

- Node 11 (Ideal image that erases the real child) – reflected in the difficulty in fully accepting the real child.

- -

- Node 16 (Desire for normality) – evident in the constant comparison with an implicit model of typical development.

- Phase 2

- -

- Node 2 (Control as defense against chaos) – shown in the rigid management of behaviors and difficulty tolerating the unexpected.

- -

- Node 18 (Punitive index) – tendency to interpret the child’s behavior in terms of blame or provocation.

- Phase 3

- -

- Node 7 (Reactive attachment) – implicit in alternating behaviors of seeking contact and manipulative control.

- -

- Node 17 (Rejection of need) – observed when the child does not verbalize needs directly, instead expressing them indirectly.

- Phase 4

- -

- Node 20 (Discordant rhythm) – difficulty of both parents and child in maintaining a stable, shared tempo during interactions.

- -

- Node 21 (Blocked gesture) – observed in moments of suspended bodily expressiveness during emotional dysregulation.

- Phase 5

- -

- Node 3 (Fragmented perception of the child) – progressively overcome and replaced with a more global and affective view.

- -

- Node 15 (Repressed impulsivity) – in the modulation of emotional and behavioral reactions.

- Phase 6

Clinical Fragments – Case 3 – Family C

- Phase 1

- -

- Node 1 (Non-integrated parental self) – in the fragmentation of the parental role.

- -

- Node 5 (Denied relational need) – in the refusal of any request for support.

- -

- Node 6 (Failure as identity) – in the association between the child’s difficulties and the parents’ perception of themselves as “bad parents.”

- -

- Node 13 (Who am I now?) – in the fracture of parental identity following the diagnosis.

- Phase 2

- -

- Node 2 (Control as defense against chaos) – in the need to maintain a stable set-up to avoid facing emotional complexity.

- -

- Node 18 (Punitive index) – in the tendency to place the responsibility for change on external factors or on the child.

- Phase 3

- -

- Node 7 (Reactive attachment) – in the rapid shift between involvement and affective withdrawal.

- -

- Node 17 (Refusal of need) – in the difficulty to accept and express vulnerability.

- Phase 4

- -

- Node 4 (Disembodied empathy) – in the purely cognitive management of some interactions with the child.

- -

- Node 20 (Discordant rhythm) – difficulty synchronizing with the child’s timing and modes.

- Phase 5

- -

- Node 3 (Fragmented perception of the child) – still prevalent, with few moments of unified vision.

- -

- Node 14 (Blocked narrative of the relationship) – inability to narrate the parent–child bond without reducing it to deficits or functions.

- Phase 6

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Principles of Integrity and Consistency in the Execution of Clinical Prompts

- -

- The files have been correctly uploaded, each bearing a clear and recognizable name for the user.

- -

- The transformative nodes linked to each phase must be explicitly stated using their correct designation.

- -

- It is necessary to specify the exclusion of nodes that belong to other phases, even if semantic overlaps exist.

- -

- A certain degree of redundancy in the production of prompts is considered necessary to significantly reduce the risk of generating inaccurate outputs.

Appendix B. Operational Commands to be Stored in the Device’s Permanent Memory

- Command 1

- -

- Use articles published in the last 10 years (2015–2025).

- -

- Prefer sources from internationally indexed journals (Scopus/Web of Science), including DOI and essential bibliometric data (IF/SJR where useful).

- Command 2

- -

-

Always use as key reference texts:

- Cooper, Heron, Heward – Applied Behavior Analysis (most recent edition).

- B.F. Skinner – seminal works on verbal behavior, operant conditioning, and learning principles.

- -

- Integrate with scientific articles from the last 10 years, but ensure main theoretical concepts and definitions remain anchored to Cooper.

- -

- The function of behavior aimed at gaining attention must be distinguished from the function of gaining control of the relationship. These are distinct functions in the scientific literature and should not be conflated.

- Command 3

- -

- Edmund Husserl – Ideas for a Pure Phenomenology; Cartesian Meditations.

- -

- Martin Heidegger – Being and Time.

- -

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty – Phenomenology of Perception.

- -

- Fritz Perls, Ralph Hefferline, Paul Goodman – Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality.

- -

- Gianni Francesetti – works on psychopathology and phenomenology in Gestalt Therapy (Psychopathology of the Situation; Diagnosis in Gestalt Psychotherapy), with a focus on the situational perspective and co-construction of experience.

- Command 4

- 1)

-

Content integrity

- -

- No cuts or additions not requested.

- -

- Order and organization identical to the original delivery, unless explicit instructions state otherwise.

- -

- Tables complete (no summaries), numbers/lists preserved.

- 2)

-

Compliance with prompt requirements

- -

- Literature: only 2015–2025, indexed journals, DOI (Command 1).

- -

- ABA: anchored to Cooper, Heron, Heward, and Skinner for definitions and programs (Command 2).

- -

- Gestalt/phenomenology: A-O.C.M. framework + classics (Husserl, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Sartre, Scheler) + Francesetti when relevant (Command 3).

- Command 5

Appendix C. Archive of Files and Notes for Permanent Device Memory

- -

- Morfini, F. Autism Open Clinical Model (A.O.C.M.): Structure of an Integrated Clinical Model for the Assessment and Treatment of Autism. Phenomena Journal—International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2023, 5(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.32069/PJ.2021.2.184 (foundational article of the model).

- -

- Extract from this article: Protocol Phases (subsection in the Materials and Methods section).

- -

- Extract from this article: Protocol Phases and Transformative Nodes (subsection in the Materials and Methods section).

- -

- Epistemological openness, welcoming verifiable scientific and clinical contributions;

- -

- Openness to dialogue between models, where ABA, CBT, and Gestalt tools are enriched with practices oriented to bodily and sensory experience;

- -

- Relational openness, recognizing evolutionary pairing as the construction of an affective and regulatory field;

- -

- Openness to the evolutionary uniqueness of each individual, understood not only in cognitive terms but also bodily and perceptual.

References

- Morfini, F. Autism Open Clinical Model (A.-O.C.M.): Structure of an integrated clinical model for the assessment and treatment of autism. Phenomena Journal—International Journal of Psychopathology Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2023, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.O.; Heron, T.E.; Heward, W.L. Applied Behavior Analysis, 3rd ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S. Action and Interaction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahavi, D. Phenomenology: The Basics; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T. Ecology of the Brain; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzale, G. Perceptual dysregulation in autism and therapeutic potential of artificial intelligence. Phenomena Journal—International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2021, 1, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. Artificial Intelligence in Clinical Psychology: Current Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesetti, G. The Field Perspective in Clinical Practice: Towards a Theory of Therapeutic Phronesis. British Gestalt Journal 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cappiello, M. Parent training procedures: family collaboration as a prognostic factor facilitating positive outcomes in ABA treatment. Phenomena Journal—International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2021, 1, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante, S.; Ruggiero, C. The Integrated Gestalt Model in the acquisition of autonomy and functional skills. Phenomena Journal—International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2020, 1, 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Morfini, F. The neurodevelopmental disorders: toward an integrated clinical model. Phenomena Journal—International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2021, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- De Vito, M.; Pellegrino, A. Being Together: strategies for teaching social skills in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Phenomena Journal—International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2021, 1, 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Di Donna, S.; Marino, F.; Durante, S.; Ammendola, A.; Morfini, F. Level 1 autism and schizoid personality disorder in adulthood. Phenomena Journal—International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2023, 5, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, B.F. Science and Human Behavior; Free Press: New York, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Francesetti, G. A Clinical Exploration of Atmospheres. Towards a Field-based Clinical Practice 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locandro, L. Autism and family quality of life: an integrated approach. Phenomena Journal—International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2020, 1, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bonadies, V.; Sasso, E. Theory of Mind and autism: intervention strategies to improve quality of life in adulthood. Phenomena Journal—International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2021, 1, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Board. Editorial: Mental Health 4.0 – The contribution of LLMs in mental health care processes. Phenomena Journal—International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2024, 4, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cioffi, V.; Ragozzino, O.; Mosca, L.L.; Moretto, E.; Tortora, E.; Acocella, A.; Montanari, C.; Ferrara, A.; Crispino, S.; Gigante, E.; Lommatzsch, A.; Pizzimenti, M.; Temporin, E.; Barlacchi, V.; Billi, C.; Salonia, G.; Sperandeo, R. Can AI Technologies Support Clinical Supervision? Assessing the Potential of ChatGPT. Informatics 2025, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Leva, A.; Trapanese, A.; Gallo, V. GEO-DE (Ecological Observational Grid for Developmental Dyspraxia): a tool for early detection in school settings and future AI-supported implementation. Phenomena Journal—International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2020, 1, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Luongo, M. The Psychodynamic Approach for Understanding and Treating Autism. Phenomena J. 2021, 3, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level of Implementation | Concise Description | Function in Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Principles of Integrity and Consistency (Appendix A) | The A.-O.C.M. protocol requires that each phase and transformative node be applied rigorously: exclusion of unrelated nodes, accuracy in naming, necessary redundancy in prompts, and strict adherence to the phenomenological and behavioral structure. | Defines the methodological framework and guarantees that prompts respect the original clinical structure without alterations. |

| Permanent Operational Commands (Appendix B) | Permanent commands ensure uniformity: updated literature (2015–2025, indexed sources), mandatory references (Cooper, Skinner, Husserl, Merleau-Ponty, Francesetti), and integrity checks prior to document delivery. | Establishes operational rules and epistemological constraints that make the model standardizable and replicable. |

| Archive and Structural References (Appendix C) | The permanent archive stores foundational articles (Morfini 2023), protocol extracts, and clinical notes on the 24 nodes across the 6 phases. It provides a stable basis to ensure replicability, epistemological coherence, and shared access between therapist and AI. | Builds the clinical and theoretical memory that integrates ABA, phenomenology, and embodied mind, ensuring continuity and traceability of the protocol. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).