1. Introduction

Atopic dermatitis is a common chronic inflammatory condition characterized by intense itching, redness, dryness, and the formation of patches or plaques on the skin [

1,

2]. Pathologically, it initially manifests as inflammatory cell infiltration, followed by epidermal spongiosis and micro-vesicle formation [

2,

3]. As the lesion becomes chronic, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis occur [

1,

3]. The exact cause of atopic dermatitis is not fully understood but is believed to result from a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and immunological factors [

4]. Individuals with a family history of atopic diseases such as asthma or hay fever are more likely to develop atopic dermatitis, suggesting a genetic predisposition. Environmental factors, including exposure to allergens, injuries, irritants and pollutants can trigger or exacerbate the condition [

5].

At the molecular level, atopic dermatitis involves dysfunction in the skin barrier, immune dysregulation, and inflammation. Mutations in genes encoding proteins that maintain the skin barrier, such as filaggrin, have been linked to an increased risk of developing atopic dermatitis [

6,

7]. These mutations typically decrease filaggrin expression and compromise skin barrier functions, causing reduced moisture retention leading to skin dryness. Reduced barrier function also compromises protection against irritants and increases permeability, allowing allergens to readily enter the epidermal layer. Consequently, an immune reaction, especially of the Th2 type, is induced, playing a key role in the pathogenesis and symptoms of atopic dermatitis [

8]. For example, elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-4 (IL-4), interleukin-13 (IL-13), and interleukin-31 (IL-31) contribute to skin inflammation, reduction of skin barrier protein expression including filaggrin, recruitment of immune cells to affected areas, and result in itching and other symptoms of atopic dermatitis [

7].

Previous studies have shown that transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4), an ion channel protein, plays an important role in the Th2 response [

9]. Moreover, TRPV4, expressed in keratinocytes and macrophages, is implicated in itching mechanisms in atopic dermatitis. In keratinocytes, TRPV4 activation by certain stimuli can trigger the release of itch-promoting substances, contributing to the intense itchiness experienced in atopic dermatitis [

10]. Additionally, TRPV4 in macrophages seems to have opposing effects depending on the context. These results are suggesting a complex interplay of skin barrier system, ion channel regulation and Th2 inflammatory response exist in atopic dermatitis pathology [

10,

11,

12]. The Th2 response also suppresses filaggrin expression, contributing to barrier dysfunction and exacerbating the condition [

13,

14]. Additionally, cytokines released by Th2 cells, such as IL-4 and IL-13, bind directly to receptors on keratinocytes, triggering their proliferation and affects the differentiation process within the stratum spinosum [

15,

16]. The inflammatory milieu also causes the release of growth factors and activation of signalling molecules that promote cell division in the stratum spinosum [

17,

18]. Additionally, the inflammatory response disrupts the normal differentiation process of these cells, leading them to remain in the stratum spinosum instead of progressing to the outer layers for shedding. This accumulation of immature cells contributes to the overall thickening observed in atopic dermatitis [

18,

19,

20]. Interestingly, the relationship is not one-directional. Damaged keratinocytes, in response to the inflammatory environment, produce alarmins like TSLP, which activate dendritic cells and type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) [

21,

22]. These cells, in turn, further promote the Th2 response, creating a positive feedback cycle that drives both keratinocyte proliferation and inflammation [

23].

Current treatment options for atopic dermatitis focus on managing symptoms, reducing inflammation, and restoring skin barrier function [

24,

25]. Commonly prescribed treatments include topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors, which help reduce inflammation and alleviate itching [

26]. Emollients and moisturizers are used to hydrate the skin and enhance barrier function [

27,

28]. In severe or refractory cases, systemic treatments such as oral corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, or biologic therapies targeting specific immune pathways may be recommended [

29,

30]. Phototherapy with ultraviolet A (UVA) or ultraviolet B (UVB) light has also proven effective in managing symptoms and reducing inflammation [

29]. While most therapies aim to control the immune response, there is relatively little emphasis given on improving the natural barrier function of skin. It is important to note that disturbances in skin barrier function are considered a primary factor in initiating the disease.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in non-pharmacological approaches and complementary therapies for atopic dermatitis [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Among these approaches, hot springs have long been recognized for their therapeutic benefits in treating various skin conditions, including atopic dermatitis, due to their unique mineral content and thermal properties. This form of therapy has been used for centuries and remains a popular treatment for dermatologic conditions to date [

34,

35,

36]. Research indicates that hot spring therapy can improve the condition of atopic dermatitis in approximately 75% of patients [

37]. Additionally, the minerals in hot springs, such as sulfur, selenium, and magnesium, have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties that can reduce skin inflammation, itching, and redness associated with atopic dermatitis [

34,

37]. Immersion in hot spring water also enhances skin hydration and barrier function by increasing the absorption of moisture and nutrients, thereby helping to restore the natural protective barrier of the skin. The relaxing and stress-relieving effects of hot springs can further contribute to managing atopic dermatitis symptoms, as stress is known to exacerbate skin conditions [

38,

39].

A few studies have been conducted to understand the mechanisms by which hot spring treatment can influence atopic dermatitis pathology. Most of the studies suggest that the temperature and combination of minerals in the hot-spring water show some anti-inflammatory effects, that are indirectly beneficial for atopic conditions. For example, a study showed that hot spring treatment decreases the Th2 response, including IL-4 production, and increases the T-reg response in an atopic dermatitis murine model [

40]. It has also been shown to decrease the skin bacterial population, which could be an important factor in atopic dermatitis pathology [

34]. However, the minerals in hot spring water could play a direct role in skin health and atopic dermatitis pathology. For instance, selenium, a mineral rich in hot spring water, is shown to protect keratinocyte stem cells against senescence by preserving their stemness phenotype and maintaining skin health [

41]. Therefore, we hypothesized that hot spring water might have a direct role in regulating atopic dermatitis pathology. Each of the hot spring water has an unique combination of mineral content. Hence, this study focuses on investigating the role of hot spring water from Arifuku hot spring in Shimane prefecture, Japan on barrier function and the underlying mechanisms using an atopic dermatitis mouse model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Adult male hairless mice of 2 months of age were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and housed in a temperature and humidity-controlled animal facility under specific pathogen free (SPF) conditions with 12 hours light-dark cycle. Two to three mice were housed in a plastic cage where wood dust was used as bedding. The mice received normal rodent chow and water ad libitum. After purchase, the mice were housed in the facility for at least 1 week for acclimatization.

2.2. Generation of Atopic Dermatitis Mouse Model:

Eight-week-old hairless mice were used to establish an injury-induced atopic dermatitis model. The mice were housed in a controlled environment with a 12-hour light-dark cycle, constant temperature (22 ± 2°C), and humidity. To induce skin barrier disruption and simulate atopic dermatitis, the tape-stripping method was employed. Briefly, the dorsal skin of each mouse was gently shaved and subjected to repeated tape-stripping using adhesive tape (approximately 10–15 times) until mild erythema was observed. The integrity of the skin barrier was assessed by measuring transepithelial water loss (TEWL) before and after tape-stripping. Mice were then divided into two groups: one group received daily topical applications of hot spring water, while the other was treated with tap water. Skin samples were collected at designated time points for histological and immunological analysis.

2.3. Preparation and Treatment with Tap Water and Hot Spring Water:

Hot spring water was collected from Arifuku hot spring in Shimane prefecture, Japan and allowed to cool to room temperature. Tap water was also collected for comparison. Both water samples were sterile filtered using a 0.22 µm filter unit before application. The filtered water was then applied to the skin of the mice once daily for the designated duration.

2.4. Measurement of Transepithelial Water Loss (TEWL)

Dermal water content and TEWL were measured using the DermaLab USB module (Cortex Technology, Hadsund, Denmark), as previously described (Sivaprasad et al., 2010). Briefly, the measurements were performed in a controlled environment to minimize external influences. The TEWL probe was placed on the dorsal skin of each mouse, and readings were recorded after stabilization. An average of two readings was used for each mouse to ensure accuracy. All measurements were conducted by the same investigator to maintain consistency.

2.5. Preparation of Skin Samples for Staining

After completing the treatment, mice were deeply anesthetized using Isoflurane (Pfizer) and transcardially perfused with normal saline, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Skin samples were collected from both the tape-stripped and healthy sides. The samples were then post-fixed in 4% PFA overnight. Following fixation, the tissues were cryoprotected in a 30% sucrose solution in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The cryoprotected tissues were embedded in an optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound, and 6 µm thick sections were prepared for histological staining or immunostaining.

2.6. Histological Examination

Skin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to evaluate histological changes. Briefly, the 6 µm frozen sections were rinsed in distilled water and stained with hematoxylin solution (Gills hematoxylin No. 2, Wako) for 5 minutes. After washing in running tap water for 20 minutes, the sections were counterstained with eosin for 2 minutes, dehydrated through graded ethanol solutions, cleared in xylene, and mounted with a coverslip using a synthetic mounting medium. Histological changes, including epidermal thickness and stratum spinosum alterations were examined under a light microscope.

2.7. Immunostaining

Immunostaining was performed to assess the expression of filaggrin, transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4), CD8, and IL-4 in skin sections. The 6 µm frozen sections were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for 5 min. For antigen retrieval, sections were incubated in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 20 minutes, then allowed to cool down for another 20 min. After cooling, sections were washed with PBS and blocked with 5% normal goat serum for 30 min at room temperature to reduce nonspecific binding. During filaggrin immunostaining, sections were incubated in 0.3% H2O2 to inhibit the endogenous peroxidase activity, the overnight at 4oC with a primary anti-filaggrin antibody (rabbit, 1:100, Abcam), followed by incubation with a biotin conjugated anti-rabbit IgG for 1 hour at room temperature. Then the tissue section was treated with an ABC complex (Vector), signal was developed using the 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma) method and examined under a light microscope. For TRPV4 and CD8 detection, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against TRPV4 (rabbit, 1:100, Abcam) and CD8 (mouse, 1:50, SantaCruz) followed by incubation with a Texas Red-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. For IL-4 detection, sections were incubated with an anti-IL-4 primary antibody (mouse, 1:100, SantaCruz) and subsequently with an FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. After staining, the tissue sections were examined under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All numerical data are presented as mean ± SD. Comparisons between groups were analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by Scheffé's post hoc test or an independent t-test, as appropriate. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software.

3. Results

Properties and mineral content of the hot-spring water used. First, the properties of hot-spring water were analyzed. The hot-spring water was colorless, astringent in taste, and the temperature was 45.3

oC. The pH is slightly acidic at 6.3, and the density was 1.0041g/cm

3. Analysis of cationic minerals revealed that Na

+ was high (1710 mg/Kg), followed by Ca2

+ (433 mg/Kg), Mg2

+ (84.4 mg/Kg), and K

+ (72.5 mg/Kg) (

Table 1). Also, a considerable amount of Sr

2+ (12.3 mg/Kg) contained in the hot-spring water (

Table 1). Among the anions, Cl

- was highest in amount (2660 mg/Kg), followed by SO4

- (965 mg/Kg), and HCO3

- (941 mg/kg) groups (

Table 2). Among the non-dissociated compounds, the amount of H

2SiO

3 was highest (118 mg/Kg), followed by HBO

2 (35.3 mg/Kg) and HAsO

2 (2.3 mg/Kg) (

Table 3). As dissolved gas, CO

2 was detected in the hot-spring water (

Table 4). The levels of other trace elements are shown in

Table 5.

Effects of hot-spring water on the skin barrier function in an injury-induced atopic dermatitis model mouse. To understand the impact of tap water (tap water group) and hot-spring water (hot-spring water group) on skin barrier functions in atopic dermatitis model mice, we measured the skin water content and trans-epidermal water loss (TEWL) in a time-dependent manner. Initially, the results indicated that the water content remained relatively stable immediately after tape-stripping injury (day 0) both mouse groups (

Figure 1A). However, on day 1, the water content had significantly decreased in tape-stripping injury, and in control areas in all groups, except in the tape stripped areas of the mice treated with tap water, where it remained elevated. On day 2, the water content had significantly decreased in both the tape-stripped and control areas across all groups, compared to day 0 (

Figure 1A). This trend continued into day 3, where the water content was still lower than that of day 0 in all groups, both in the tape-stripped and control areas (

Figure 1A). Notably, the tape-stripped areas of the tap water-treated group exhibited a lower water content compared to their respective control areas at day 3 (

Figure 1A).

We also examined the rate of trans-epithelial water loss in these mice. The results indicated a significant increase in TEWL in the tape-stripped areas compared to the control areas of both tap water-treated and hot spring water-treated mice on days 0 and 1 (

Figure 1B). From day 2 onward, TEWL began to decrease in tape-stripped areas in both the tap water-treated and hot-spring water-treated groups, with this trend persisting into day 3 (

Figure 1B). Crucially, by day 3, the TEWL from the tape-stripped areas in the hot-spring water-treated group was significantly decreased compared to that in the tap water-treated group (

Figure 1B).

Effects of hot-spring water on the skin histology in an atopic dermatitis model mouse. Next, we analyzed the time-dependent changes in the skin histology of atopic dermatitis model mice after treatment with tap water or hot-spring water. The hematoxylin and eosin staining results showed that the normal skin of the mice displayed distinct layers in the epidermis: stratum basale, stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, and stratum corneum (

Figure 2a). After tape-stripping, there were minimum changes in the epidermis, except the detachment or removal of stratum conium (

Figure 2b). In the tape-stripped areas of skin treated with tap water and hot-spring water, there were minimal changes in the stratum basale at day 0 (

Figure 2 b). Similarly, the stratum spinosum and stratum granulosum showed little change on days 0. From day 2, the stratum spinosum layer in tape-stripped began to expand, with some vacuolation appearing in both the tap water-treated and hot-spring water-treated mice (

Figure 2c and 2d). By day 3, the stratum spinosum was significantly thicker in the tap water-treated mice compared to those treated with hot-spring water (

Figure 2e and 2f). Additionally, numerous vacuolations were observed in this layer in the tap water-treated mice, while very few were seen in the hot-spring water-treated mice. Importantly, the stratum granulosum was well-formed in the tape-stripped areas of hot-spring water-treated mice, whereas it was very thin in the tap water-treated mice (

Figure 2e and 2f). The stratum corneum was found to be detached or absent on days 0 and 2. By day 3, the stratum corneum began to form in the tape-stripped areas of the hot-spring water-treated mice, a feature that was difficult to observe in the tap water-treated mice (

Figure 2e and 2f).

Next, we examined the time-dependent changes in the skin histology of non-tape-stripped areas in mice treated with tap water and hot spring water. Although there were almost no changes observed on days 0 (

Figure 3a), the thickness of the stratum spinosum layer began to increase by day 2 in the hot spring water-treated mice only (see

Figure 3b and 3c). In contrast, the stratum spinosum layer in the tap water-treated mice increased in thickness by day 3 (

Figure 3d), whereas it returned to normal thickness in the hot-spring water-treated mice on day 3 (

Figure 3e).

Effects of hot-spring water on TRPV4 protein levels in an atopic dermatitis model mouse. Since TRPV4 is known to be involved in the pathology of atopic dermatitis, we examined the time-dependent changes in its levels in atopic dermatitis model mice. Immunostaining results indicated that TRPV4 is primarily expressed in the epidermal layer of the skin. On day 1, the levels of TRPV4 decreased in the tape-stripped areas of both tap water-treated and hot spring water-treated mice compared to day 0 (

Figure 4A, a-c). By day 3, the levels of TRPV4 almost had returned to those observed on day 0 in the tape-stripped areas of both tap water-treated and hot spring water-treated mice (

Figure 4A, d-e). Quantification of the immunostaining also showed no difference in the immunopositive areas between the tap water-treated group and the hot spring water-treated group at the same time point (

Figure 4B).

Effects of hot-spring water on filaggrin protein levels in an atopic dermatitis model mouse. Filaggrin plays a crucial role in skin barrier function. Given that both trans-epidermal water loss (TEWL) and histological examinations showed an improvement in skin barrier function following hot spring water treatment, we investigated the levels of filaggrin protein in the skin of injury-induced atopic dermatitis model mice. Immunostaining results revealed that filaggrin was primarily expressed in the stratum corneum and stratum granulosum, although some cells in deeper layers also showed its expression (

Figure 6a). Following tape stripping, the number of filaggrin-expressing cells in the stratum granulosum decreased compared to non-tape stripped areas at day 0 (

Figure 5a). The levels of filaggrin increased on day 2 compared to day 0 in the tape-stripped areas for both tap water-treated and hot spring water-treated mice (

Figure 5b and 5c). By day 3, filaggrin levels in the tape-stripped areas had increased further compared to days 0 in both groups of mice (

Figure 5d and 5e). In the hotspring water-treated mice, the protein immunoreactivity was predominantly strong in the upper layers, including the stratum granulosum (

Figure 5e). In contrast, in the tap water-treated mice, the immunoreactivity was more diffuse, with less pronounced positivity in the upper layers of the epidermis (compare 5d and 5e).

Figure 5.

Time-dependent evaluation of filaggrin protein levels in the tape-stripped skin areas of atopic dermatitis mouse model treated with tap water or hot-spring water. Atopic dermatitis models were generated by Tape-stripping, and filaggrin protein levels in the skin of tape-stripped areas were evaluated by immunostaining, as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) Representative filaggrin immunostaining photomicrographs of the mice skin of tape-stripped areas at day 0 (a), day 1 (b and c), and day 3 (d and e) are shown here, where (b and d) are from the mice that received tape water treatment, and (c and e) received hot-spring water. All pictures were taken at X400 magnification. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure 5.

Time-dependent evaluation of filaggrin protein levels in the tape-stripped skin areas of atopic dermatitis mouse model treated with tap water or hot-spring water. Atopic dermatitis models were generated by Tape-stripping, and filaggrin protein levels in the skin of tape-stripped areas were evaluated by immunostaining, as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) Representative filaggrin immunostaining photomicrographs of the mice skin of tape-stripped areas at day 0 (a), day 1 (b and c), and day 3 (d and e) are shown here, where (b and d) are from the mice that received tape water treatment, and (c and e) received hot-spring water. All pictures were taken at X400 magnification. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure 6.

Time-dependent evaluation of filaggrin protein levels in the non-tape-stripped control skin areas of atopic dermatitis mouse model treated with tap water or hot-spring water. Atopic dermatitis models were generated by Tape-stripping, and filaggrin protein levels in the skin of non-tape-stripped control areas were evaluated by immunostaining, as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) Representative filaggrin immunostaining photomicrographs of the mice skin of tape-stripped areas at day 0 (a), day 1 (b and c), and day 3 (d and e) are shown here, where (b and d) are from the mice that received tape water treatment, and (c and e) received hot-spring water. All pictures were taken at X400 magnification. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure 6.

Time-dependent evaluation of filaggrin protein levels in the non-tape-stripped control skin areas of atopic dermatitis mouse model treated with tap water or hot-spring water. Atopic dermatitis models were generated by Tape-stripping, and filaggrin protein levels in the skin of non-tape-stripped control areas were evaluated by immunostaining, as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) Representative filaggrin immunostaining photomicrographs of the mice skin of tape-stripped areas at day 0 (a), day 1 (b and c), and day 3 (d and e) are shown here, where (b and d) are from the mice that received tape water treatment, and (c and e) received hot-spring water. All pictures were taken at X400 magnification. Scale bar = 50 μm.

On the non-tape-stripped control side, filaggrin levels were highest on day 0, with strong immunopositive areas found in the stratum granulosum and stratum corneum (

Figure 6a). Interestingly, in tap water-treated mice, filaggrin levels gradually decreased on days 2 and 3 in this area (

Figure 6b and 6d). In the case of hot-spring water-treated mice, filaggrin levels also decreased over time (

Figure 6c and 6e). However, on day 3, filaggrin remained strongly positive in the stratum granulosum and stratum corneum of hot-spring water-treated mice, which was not observed in tap water-treated mice (compare

Figure 5d and 5e). Moreover, on days 3, the levels of filaggrin in the non-tape-stripped areas were higher in hot-spring water-treated mice compared to tap water-treated mice (

Figure 6d and 6e).

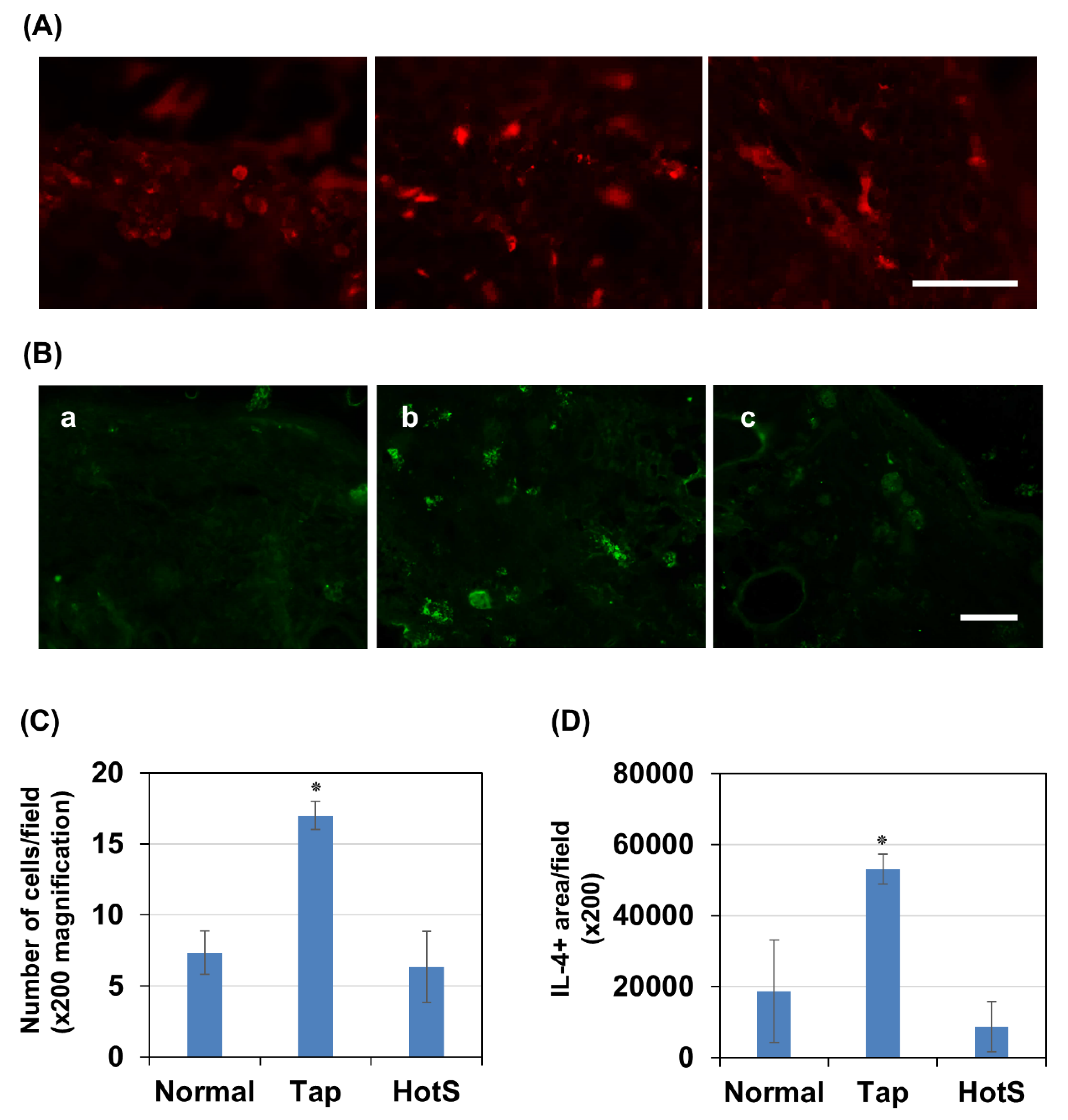

Effects of hot spring water on skin inflammation in an atopic dermatitis mouse model. Since filaggrin levels in the skin are greatly influenced by inflammation, we investigated the effects of hot spring water on CD8

+ T cells and IL-4 cytokines in the tape-stripped areas three days after model induction. Immunostaining results showed that CD8

+ T cells were rarely detected in normal skin but were significantly increased in number three days after tape stripping in mice treated with tap water (

Figure 7A and 7C). Notably, treatment with hot spring water significantly reduced the number of CD8

+ cells to a level comparable to that of normal skin

Next, we examined IL-4 levels, a cytokine known to increase in atopic dermatitis and contribute to reduced filaggrin expression. Similarly, immunostaining results demonstrated that IL-4-positive areas were rarely detected in normal skin but were significantly increased three days after tape stripping in tap water-treated mice (

Figure 7B and 7D). Importantly, treatment with hot spring water reduced IL-4-positive areas to levels comparable to those observed in normal skin.

4. Discussion

The most significant findings of this study are that filaggrin expression increased in the upper layer of the epidermis on the tape-stripped side of hot spring water-treated injury-induced atopic dermatitis model mice, accompanied by a well-formed stratum granulosum. Skin barrier function is crucial in the pathology of atopic dermatitis, serving as the first line of defense against environmental irritants, allergens, and pathogens [

42]. In individuals with atopic dermatitis, this barrier is typically compromised, leading to increased permeability and reduced protection, particularly against allergens and irritants, which induces an inflammatory condition [

43]. Furthermore, a weakened skin barrier loses moisture more readily, contributing to the dry and scaly skin characteristic of the condition [

42,

43,

44]. Given that the maturation of the stratum granulosum to stratum corneum and the role of filaggrin in aggregating keratin fibers are essential for skin barrier formation, our data suggests that Arifuku hot spring water can improve skin barrier function. Thus, maintaining and restoring the integrity of the skin barrier through hot spring treatment could be a key point in managing atopic dermatitis.

Chemical analysis revealed a high concentration of sodium, calcium, magnesium, bicarbonate, chloride, phosphate, and sulfate ions in Arifuku hot spring water, especially with a notable amount of strontium. Studies have shown that strontium can suppress sensory irritation without causing local anesthetic side effects, making it a potential treatment for irritant dermatitis [

45]. Additionally, strontium salts have been demonstrated to improve skin barrier function in skin irritation injury models in both animals and humans [

46,

47,

48]. While we did not specifically investigate whether the presence of strontium alone is responsible for these beneficial effects, other chemicals in this hot-spring water, such as silicic acid, have also been shown to benefit the skin by improving thickness and reducing wrinkles [

49]. Also, high concentration of bicarbonate could be important for the commensal skin bacterial population. Therefore, it is possible that the beneficial effects observed may stem from a combination of chemicals present in the hot spring water, rather than solely from strontium. However, it will be interesting to investigate which chemicals of the hot spring water provide beneficial effects. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the beneficial effects are not solely attributed to the temperature of the hot-spring water, as we applied the water at room temperature during our study.

The measurement of skin water content showed that on day 1, the water content of the skin in tape-stripped areas of mice treated with tap water increased significantly compared to all other conditions. However, by day 2, the water content had gradually decreased in all conditions, only to begin increasing again by day 3. The initial decrease in water content can likely be attributed to diminished barrier functions caused by the loss of stratum granulosum due to tape-stripping. However, the explanation for the increased water content on day 1 in tap water-treated mice in the tape-stripped areas is difficult to ascertain. Research on the water content of skin with dermatitis reveals some interesting yet conflicting findings. Some studies indicate an increase in water content in the upper layers of individuals with dermatitis [

50,

51,

52]. However, this water appears to be trapped within the inflamed tissue rather than being properly integrated into healthy skin cells [

51,

52,

53]. This trapped water disrupts natural barrier function of the skin, which normally helps retain moisture and keep irritants out [

54]. Therefore, it seems that hot-spring water may have an antiinflammatory effect on atopic skin conditions from the outset, reducing inflammation and resulting in reduced water content in the skin from the beginning.

Another inconsistency is observed in the non-tape-stripped areas of both hot spring water and tap water-treated mice, where the water content decreases similarly to the tape-stripped areas. We found that in these non-tape-stripped areas, there is reactive thickening of the stratum spinosum, along with decreased filaggrin expression. These results suggest that there is a reaction to the tape-stripping in other parts of the skin as well, which may be responsible for the decreased water content. However, Trans-epidermal Water Loss (TEWL) results did not indicate increased water loss from the non-tape-stripped areas, suggesting that despite decreased filaggrin expression, the barrier remains intact in those areas [

55,

56]. TEWL results also revealed that water loss gradually decreased in the tape-stripped areas from day 2 in both tap water-treated and hot spring water-treated mice. Importantly, hot spring water significantly decreased water loss compared to tap water-treated mice in the tape-stripped areas by day 3, suggesting that hot-spring water has a healing effect on skin inflammatory conditions.

Histological examination revealed that tape-stripping completely removed, at least detached the stratum corneum. Time-dependent histological analysis of the skin showed typical changes consistent with atopic dermatitis [

57]. We found that after tape stripping, the stratum spinosum increased in thickness in both tap water-treated and hot spring water-treated areas. However, on day 3, the thickness of the stratum spinosum decreased in hot-spring water-treated mice compared to tap water-treated mice. The increased thickness is usually caused by inflammatory reactions involving growth factors and cytokines, including IL-4 and IL-13 [

7,

58,

59,

60]. Also, inflammatory conditions prevent the keratinocytes to be mature and form the upper barrier layer [

46,

61]. Although we did not investigate the inflammatory component in atopic dermatitis and the effects of hot spring water on it, it is possible that hot spring water might decrease inflammation and provide beneficial effects. As evidence of decreased inflammation, we found that vacuolation, which is typically present in atopic dermatitis inflammatory conditions, was reduced. However, minerals like strontium are known to increase keratinocyte proliferation and maturation [

46]. Since the concentration of strontium is high in the hot spring water, it might help keratinocytes to mature, leading to the decreased thickness of the stratum spinosum. Indeed, we found that the stratum granulosum was well-formed in the hot spring water-treated tape-stripped area only. Such a well-formed upper layer helps to regain the barrier function of the skin, an important aspect of atopic dermatitis therapy.

Another important finding is that hot spring water increases filaggrin expression in tape-stripped areas. Filaggrin, a key protein in skin barrier function, is tightly regulated at the molecular level, particularly in keratinocytes [

6]. Several signaling pathways modulate its expression. One of the prominent regulators is calcium signaling, where elevated intracellular calcium levels trigger filaggrin expression through the activation of calcium-dependent transcription factors like CREB [

62,

63]. Additionally, cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13, prevalent in atopic dermatitis, can downregulate filaggrin expression via the JAK-STAT pathway [

64,

65]. Our investigation into inflammation status also suggests such possibility. The significant increase in CD8

+ T cells and IL-4 expression following tape stripping in tap water-treated mice aligns with previous reports indicating that immune activation and Th2 cytokines play a crucial role in atopic dermatitis pathology [

13,

14]. The reduction of CD8

+ T cells and IL-4 levels in hot spring water-treated mice suggests that this treatment may help suppress excessive immune activation and mitigate inflammatory responses in the skin. Given that IL-4 is known to downregulate filaggrin expression [

66,

67], the observed decrease in IL-4-positive areas in hot spring water-treated mice may contribute to improved skin barrier function. Hot spring water contains a high concentration of bicarbonate. Taking a bath in bicarbonate water has been shown to increase blood flow by enhancing eNOS activity and NO levels [

68]. This increased blood flow might positively affect the inflammatory condition and improve the skin condition in atopic dermatitis. Additionally, it will be interesting to see the effects of strontium on skin inflammation, as this mineral is present in high levels in hot spring water.

TRPV4, a member of the transient receptor potential (TRP) family of ion channels, plays a multifaceted role in atopic dermatitis (AD) [

10]. TRPV4 in macrophages has been shown to inhibit NF-κB, thereby reducing the expression of inflammatory cytokines. TRPV4 is also a crucial component of skin keratinocytes [

10]. It has been demonstrated that TRPV4 is important for the itching mechanism in various disease conditions, includ-ing AD [

10,

11]. Research has shown that TRPV4 expression is upregulated in the skin of individuals with AD, and this upregulation is associated with increased inflammatory responses and skin barrier dysfunction [

10]. Its heightened expression in AD-affected skin suggests its involvement in disease pathology. TRPV4 activation leads to calcium influx, triggering downstream signaling cascades implicated in inflammation, barrier dysfunction, and itch sensation, all hallmark features of AD [

69]. Additionally, TRPV4 activation can enhance the release of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8 from keratinocytes and immune cells, exacerbating the inflammatory response in AD [

10,

70]. Furthermore, TRPV4 activation has been linked to the disruption of epidermal barrier function, contributing to increased permeability and susceptibility to allergens and irritants in AD-affected skin [

9]. However, in our study, it was found that TRPV4 levels were not affected by hot spring water, indicating that TRPV4 might not be involved in the beneficial effects of hot-spring water in atopic dermatitis conditions.

There are several limitations to this study. First, we used a skin injury model through tape stripping without applying any allergen to the injured skin. Since no allergen was used to elicit an immune response, such model might not be considered as AD model. However, we used hairless mice, which exhibit splenomegaly and waxy skin deposits that peel off in large flakes, suggesting an altered immune system that affects the skin [

71]. Tape-stripping injuries on these mice have caused desquamation and the formation of shallow furrows on the skin, appearing as fine, regular wrinkles, which are indicative of chronic eczematous dermatitis [

72]. Also, tape stripping injury even in C57/BL mice can elevate several Th2-type cytokines [73]. Since Th2 type immune response plays an important role in atopic dermatitis, it is conceivable that tape stripping in the hairless mice model may share some characteristics with atopic dermatitis. However, further detailed studies are necessary to understand the underlying pathophysiology of tape stripping in the context of atopic dermatitis pathology in hairless mice. Second, we have shown that the levels of the skin barrier protein filaggrin were increased by our hot spring water. However, the detailed molecular mechanisms behind these beneficial effects have not been studied. We examined changes in Th2-type cytokines and CD8

+ T cells, which are known to contribute to decreased filaggrin levels in the skin, particularly in conditions like atopic dermatitis. However, the direct effects of our hot spring water on CD8

+ T cell accumulation and Th2-type cytokine production require further in vitro and in vivo studies. Third, we have only examined the initial changes in skin pathology after tape stripping. A more detailed study that monitors the time-dependent changes in skin pathology over a longer period would be valuable. Finally, there are several models of atopic dermatitis that explore different aspects of the pathology. It would be interesting to assess the effects of our hot spring water on these other atopic dermatitis models.

Figure 1.

Effects of hot-spring water on the water content and trans-epidermal water loss in an atopic dermatitis mouse model. Atopic dermatitis model was generated by tape-stripping, and treated with tap water, or hot-spring water for indicated times. Water content (A) and trans-epidermal water loss (TEWL) (B) was measured in tape-striped and non-tape-stripped control skin daily for 3 days, as described in the Materials and Methods. Data presented here as average ± SD (n=5). Tap-tape= tape-stripped area of the mice treated with tap water; Tap-control= non-tape-stripped area of the mice treated with tap water; HotS-tape= Tape-stripped area of the mice treated with hot-spring water; HotS-control= Non-tape-stripped area of the mice treated with hot-spring water. #p<0.01 vs corresponding control; *p<0.01 vs corresponding Tap-tape.

Figure 1.

Effects of hot-spring water on the water content and trans-epidermal water loss in an atopic dermatitis mouse model. Atopic dermatitis model was generated by tape-stripping, and treated with tap water, or hot-spring water for indicated times. Water content (A) and trans-epidermal water loss (TEWL) (B) was measured in tape-striped and non-tape-stripped control skin daily for 3 days, as described in the Materials and Methods. Data presented here as average ± SD (n=5). Tap-tape= tape-stripped area of the mice treated with tap water; Tap-control= non-tape-stripped area of the mice treated with tap water; HotS-tape= Tape-stripped area of the mice treated with hot-spring water; HotS-control= Non-tape-stripped area of the mice treated with hot-spring water. #p<0.01 vs corresponding control; *p<0.01 vs corresponding Tap-tape.

Figure 2.

Time-dependent histological evaluation of the skin on the tape-stripped areas of atopic dermatitis mouse model treated with tap water or hot-spring water. Atopic dermatitis mouse models were generated by Tape-stripping, and histological evaluation of the tape-stripped areas were done by Haematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining, as described in the Materials and Methods. Representative HE photomicrographs of the mice skin at day 0 (b), day 2 (c and d) and day 3 (e and f) after tape-stripping are shown here, where (c and e) are from the mice that received tape water treatment, and (d and f) received hot-spring water. All pictures were taken at X400 magnification. Figure (a) is a representative photomicrograph of the skin of a normal mouse. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure 2.

Time-dependent histological evaluation of the skin on the tape-stripped areas of atopic dermatitis mouse model treated with tap water or hot-spring water. Atopic dermatitis mouse models were generated by Tape-stripping, and histological evaluation of the tape-stripped areas were done by Haematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining, as described in the Materials and Methods. Representative HE photomicrographs of the mice skin at day 0 (b), day 2 (c and d) and day 3 (e and f) after tape-stripping are shown here, where (c and e) are from the mice that received tape water treatment, and (d and f) received hot-spring water. All pictures were taken at X400 magnification. Figure (a) is a representative photomicrograph of the skin of a normal mouse. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure 3.

Time-dependent histological evaluation of the skin on the non-tape-stripped areas of atopic dermatitis mouse model treated with tap water or hot-spring water. Atopic dermatitis models were generated by Tape-stripping, and histological evaluation of the non-tape-stripped control areas were done by Haematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining, as described in the Materials and Methods. Representative HE photomicrographs of the mice skin of non-tape-stripped control areas at day 0 (a), day 2 (b and c) and day 3 (d and e) after tape-stripping are shown here, where (b and d) are from the mice that received tape water treatment, and (c and f) received hot-spring water. All pictures were taken at X400 magnification. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure 3.

Time-dependent histological evaluation of the skin on the non-tape-stripped areas of atopic dermatitis mouse model treated with tap water or hot-spring water. Atopic dermatitis models were generated by Tape-stripping, and histological evaluation of the non-tape-stripped control areas were done by Haematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining, as described in the Materials and Methods. Representative HE photomicrographs of the mice skin of non-tape-stripped control areas at day 0 (a), day 2 (b and c) and day 3 (d and e) after tape-stripping are shown here, where (b and d) are from the mice that received tape water treatment, and (c and f) received hot-spring water. All pictures were taken at X400 magnification. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure 4.

Time-dependent evaluation of TRPV4 protein levels the skin of atopic dermatitis mouse model treated with tap water or hot-spring water. Atopic dermatitis models were generated by Tape-stripping, and TRPV4 protein levels in the skin of tape-stripped areas were evaluated by immunostaining, as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) Representative TRPV4 immunostaining photomicrographs of the mice skin of tape-stripped areas at day 0 (a), day 1 (b and c), and day 3 (d and e) are shown here, where (b and d) are from the mice that received tape water treatment, and (c and e) received hot-spring water. All pictures were taken at X400 magnification. Scale bar = 50 μm. The immuno-positive areas were measured using ImageJ, expressed as % of total area, and the average data were presented in (B).

Figure 4.

Time-dependent evaluation of TRPV4 protein levels the skin of atopic dermatitis mouse model treated with tap water or hot-spring water. Atopic dermatitis models were generated by Tape-stripping, and TRPV4 protein levels in the skin of tape-stripped areas were evaluated by immunostaining, as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) Representative TRPV4 immunostaining photomicrographs of the mice skin of tape-stripped areas at day 0 (a), day 1 (b and c), and day 3 (d and e) are shown here, where (b and d) are from the mice that received tape water treatment, and (c and e) received hot-spring water. All pictures were taken at X400 magnification. Scale bar = 50 μm. The immuno-positive areas were measured using ImageJ, expressed as % of total area, and the average data were presented in (B).

Figure 7.

Time-dependent evaluation of CD8+ T cells and IL-4 levels the skin of atopic dermatitis mouse model treated with tap water or hot-spring water. Atopic dermatitis models were generated by Tape-stripping, and CD8+ cell number and IL-4 immunopositive areas in the skin of tape-stripped areas were evaluated by immunostaining, as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) Representative CD8 immunostaining photomicrographs of the mice skin of tape-stripped areas normal (a), tape-stripped and tap water treated (b), and tape-stripped and hot-spring water treated (c) are shown here. All pictures were taken at X200 magnification. Scale bar = 100 μm. CD8+ cells were counted using ImageJ, expressed as number of cells per field, and the average data were presented in (C). (B) Representative IL-4 immunostaining photomicrographs of the mice skin of tape-stripped areas normal (a), tape-stripped and tap water treated (b), and tape-stripped and hot-spring water treated (c) are shown here. All pictures were taken at X200 magnification. Scale bar = 100 μm. IL-4 positive areas were quantified using ImageJ, expressed as positive areas per field (pixel), and the average data were presented in (D). Statistical significance is denoted as follows; p< 0.01 vs normal or Hot-spring water treated (HotS) mice.

Figure 7.

Time-dependent evaluation of CD8+ T cells and IL-4 levels the skin of atopic dermatitis mouse model treated with tap water or hot-spring water. Atopic dermatitis models were generated by Tape-stripping, and CD8+ cell number and IL-4 immunopositive areas in the skin of tape-stripped areas were evaluated by immunostaining, as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) Representative CD8 immunostaining photomicrographs of the mice skin of tape-stripped areas normal (a), tape-stripped and tap water treated (b), and tape-stripped and hot-spring water treated (c) are shown here. All pictures were taken at X200 magnification. Scale bar = 100 μm. CD8+ cells were counted using ImageJ, expressed as number of cells per field, and the average data were presented in (C). (B) Representative IL-4 immunostaining photomicrographs of the mice skin of tape-stripped areas normal (a), tape-stripped and tap water treated (b), and tape-stripped and hot-spring water treated (c) are shown here. All pictures were taken at X200 magnification. Scale bar = 100 μm. IL-4 positive areas were quantified using ImageJ, expressed as positive areas per field (pixel), and the average data were presented in (D). Statistical significance is denoted as follows; p< 0.01 vs normal or Hot-spring water treated (HotS) mice.

Table 1.

Minerals content in the hot-spring water (Cations).

Table 1.

Minerals content in the hot-spring water (Cations).

| Components |

mg |

mval |

mval% |

| Li+

|

1.8 |

0.26 |

0.25 |

| Na+

|

1710 |

74.38 |

70.51 |

| K+

|

72.5 |

1.85 |

1.75 |

| Mg2+

|

84.4 |

6.94 |

6.58 |

| Ca2+

|

433 |

21.61 |

20.49 |

| Sr2+

|

12.3 |

0.28 |

0.27 |

| Mn2+

|

0.4 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| Fe2++Fe3+

|

4.1 |

0.15 |

0.14 |

| Total Cations |

2318.5 |

105.48 |

100.00 |

Table 2.

Mineral content in the hot-spring water (Anions).

Table 2.

Mineral content in the hot-spring water (Anions).

| Components |

mg |

mval |

mval% |

| F-

|

1.0 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

| Cl-

|

2660 |

75.03 |

67.77 |

| Br-

|

8.6 |

0.11 |

0.10 |

| I-

|

0.7 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| SO42-

|

965 |

20.09 |

18.14 |

| HCO3-

|

941 |

15.42 |

13.93 |

| Total Anions |

4576.3 |

110.71 |

100.00 |

Table 3.

Non-dissociated components in the hot-spring water.

Table 3.

Non-dissociated components in the hot-spring water.

| Components |

mg |

mmol |

| HAsO2

|

2.3 |

0.02 |

| H2SiO3

|

118 |

1.51 |

| HBO2

|

35.3 |

0.81 |

| Total non-dissociated components |

155.6 |

2.34 |

Table 4.

Dissolved gas components in the hot-spring water.

Table 4.

Dissolved gas components in the hot-spring water.

| Components |

mg |

mmol |

| CO2 |

484 |

11.00 |

| H2S |

0.0 |

0.00 |

| Total dissolved gas components |

484.0 |

11.00 |

Table 5.

Other trace elements.

Table 5.

Other trace elements.

| Ba2+

|

0.05mg |

| Al3+

|

0.03mg |

| Cu2+

|

Not detected<0.005mg |

| Zn2+

|

0.088mg |

| Cd2+

|

0.002mg |

| Pb2+

|

0.073mg |

| Hg |

Not detected<0.0005mg |

| As |

1.59mg |

| S2O32-

|

Not detected<0.01mg |

| CO32-

|

Not detected<0.1mg |