Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

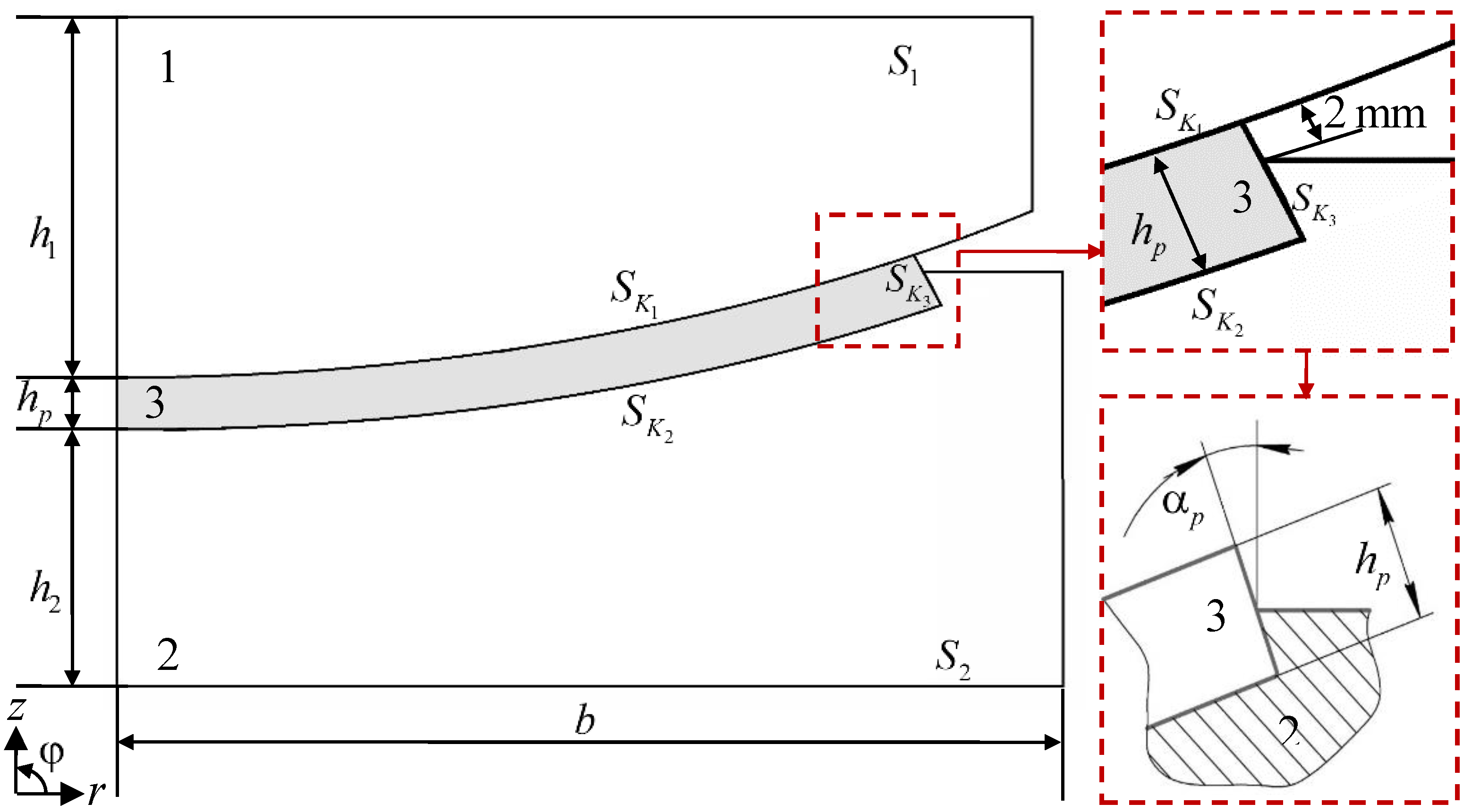

2.1. The Design of the Spherical Bearing

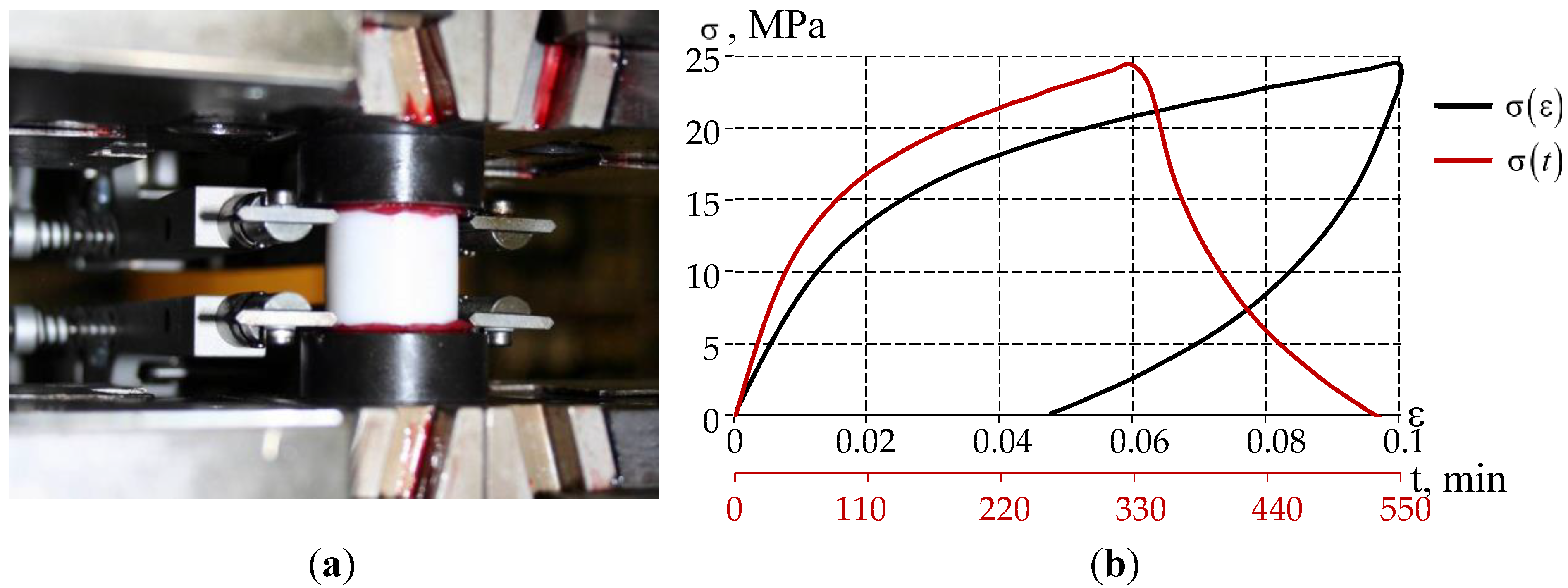

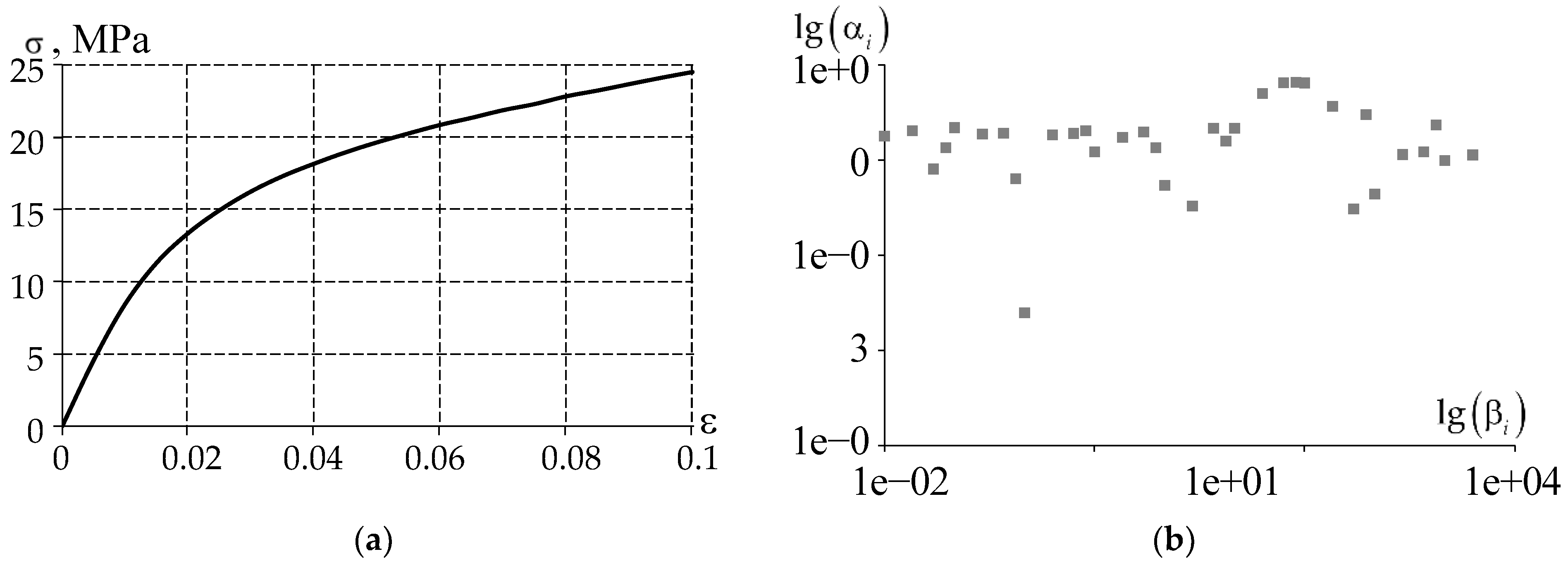

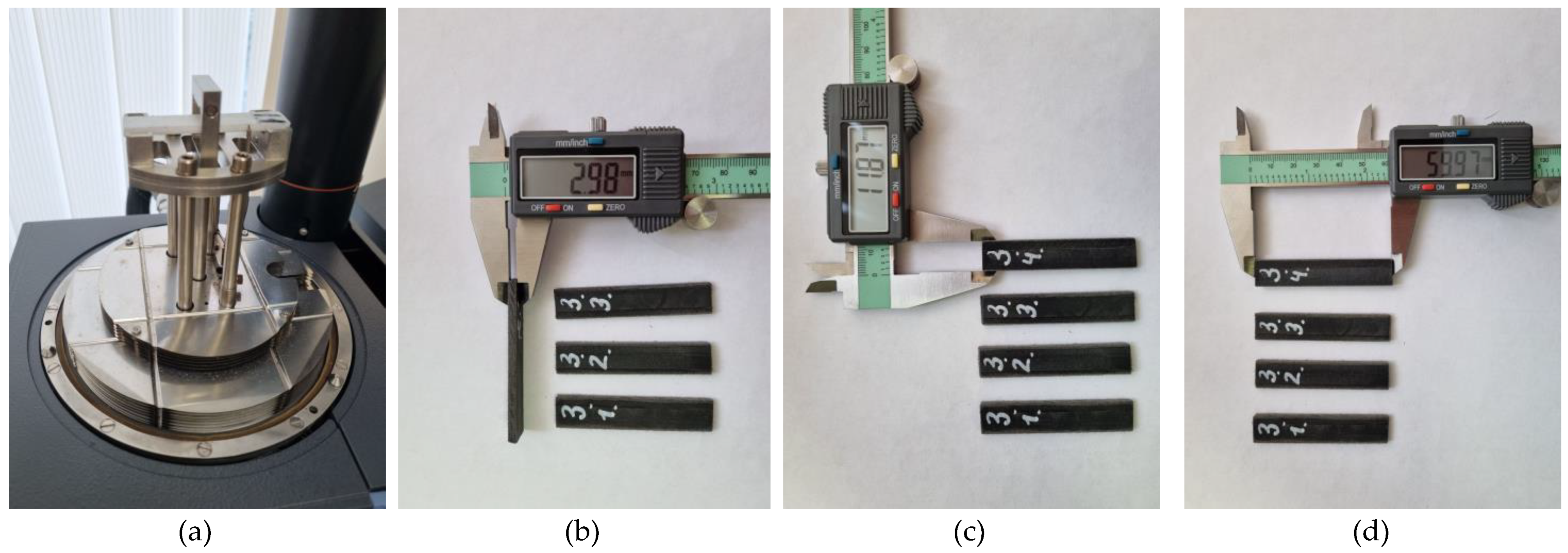

2.2. Sliding Layer Material

2.3. The Numerical Model

3. Results

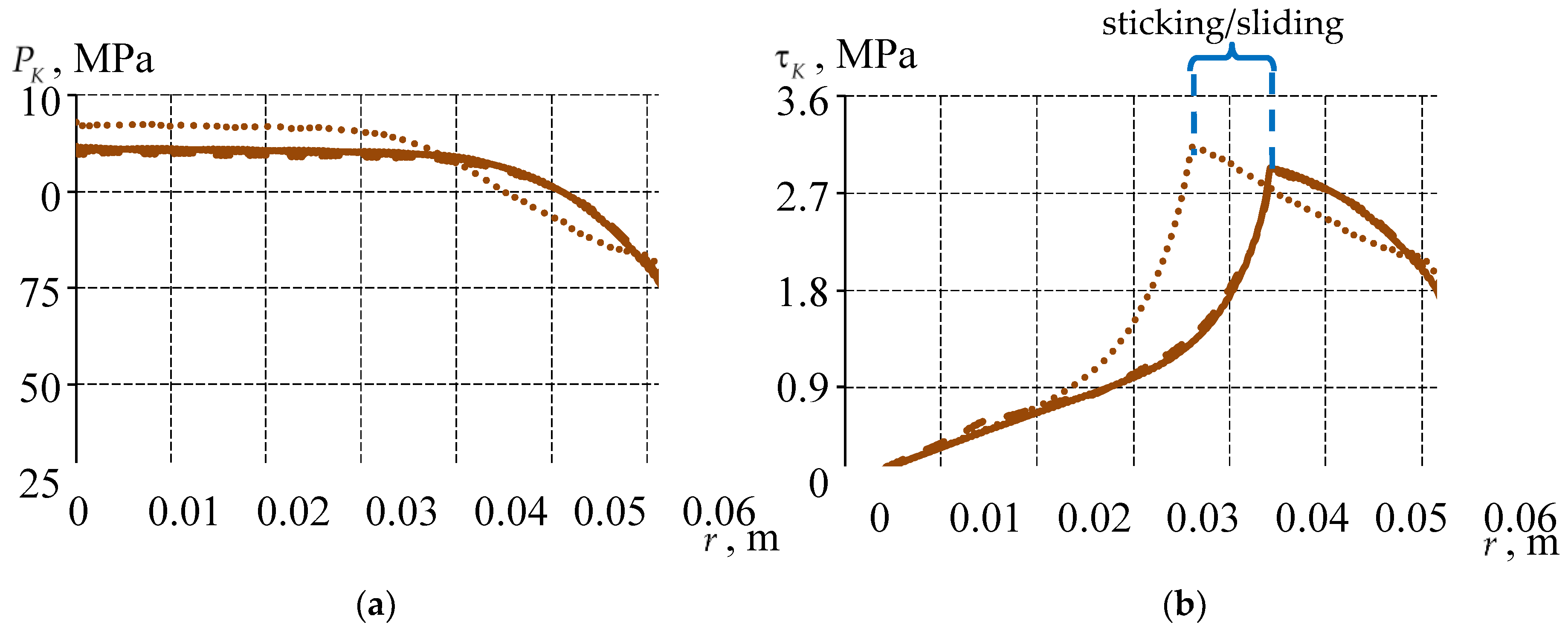

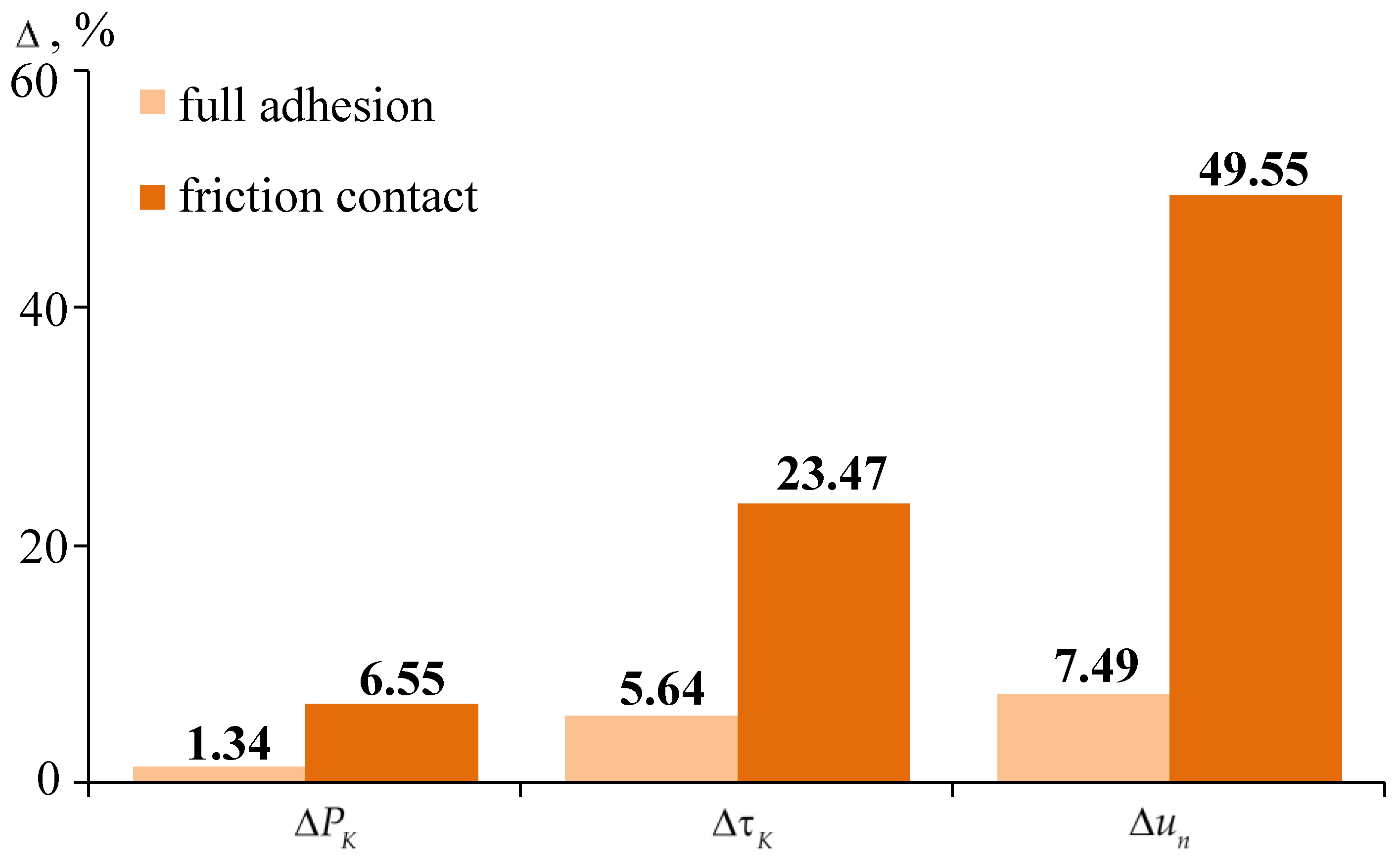

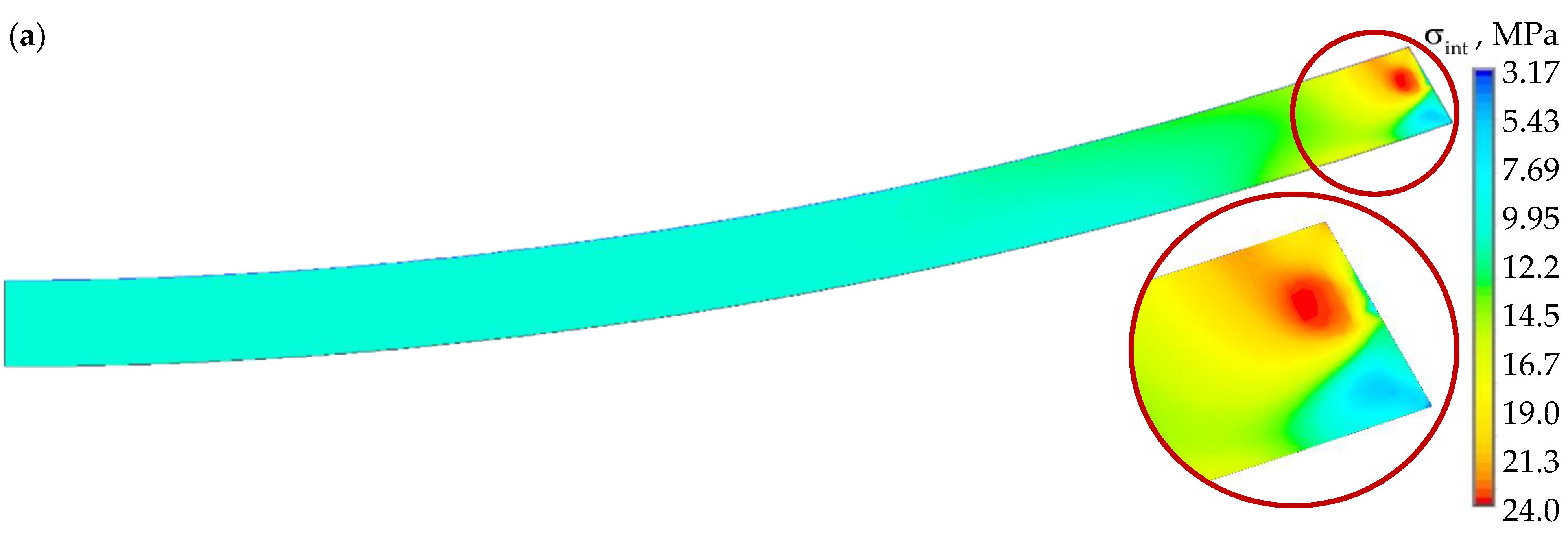

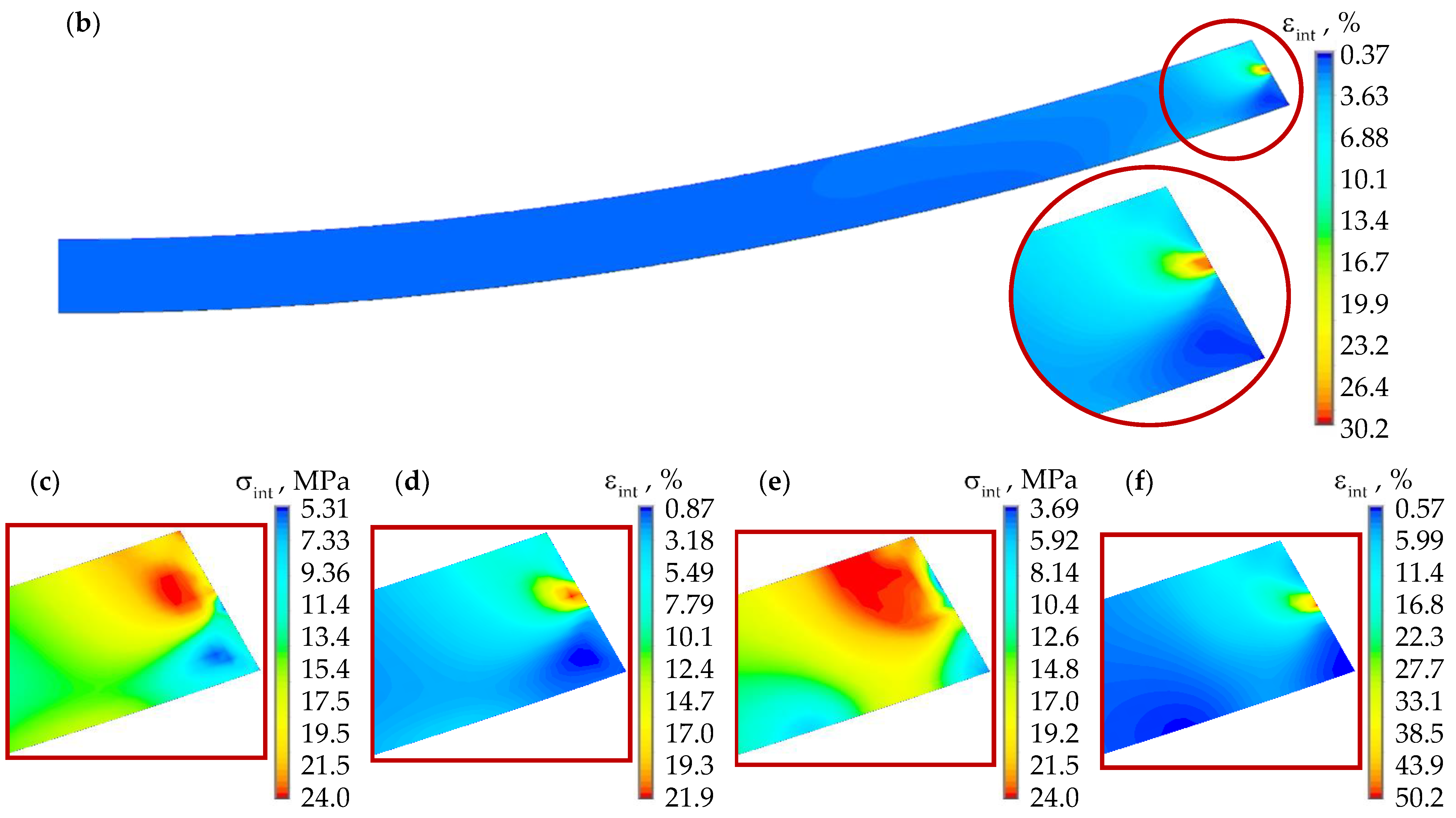

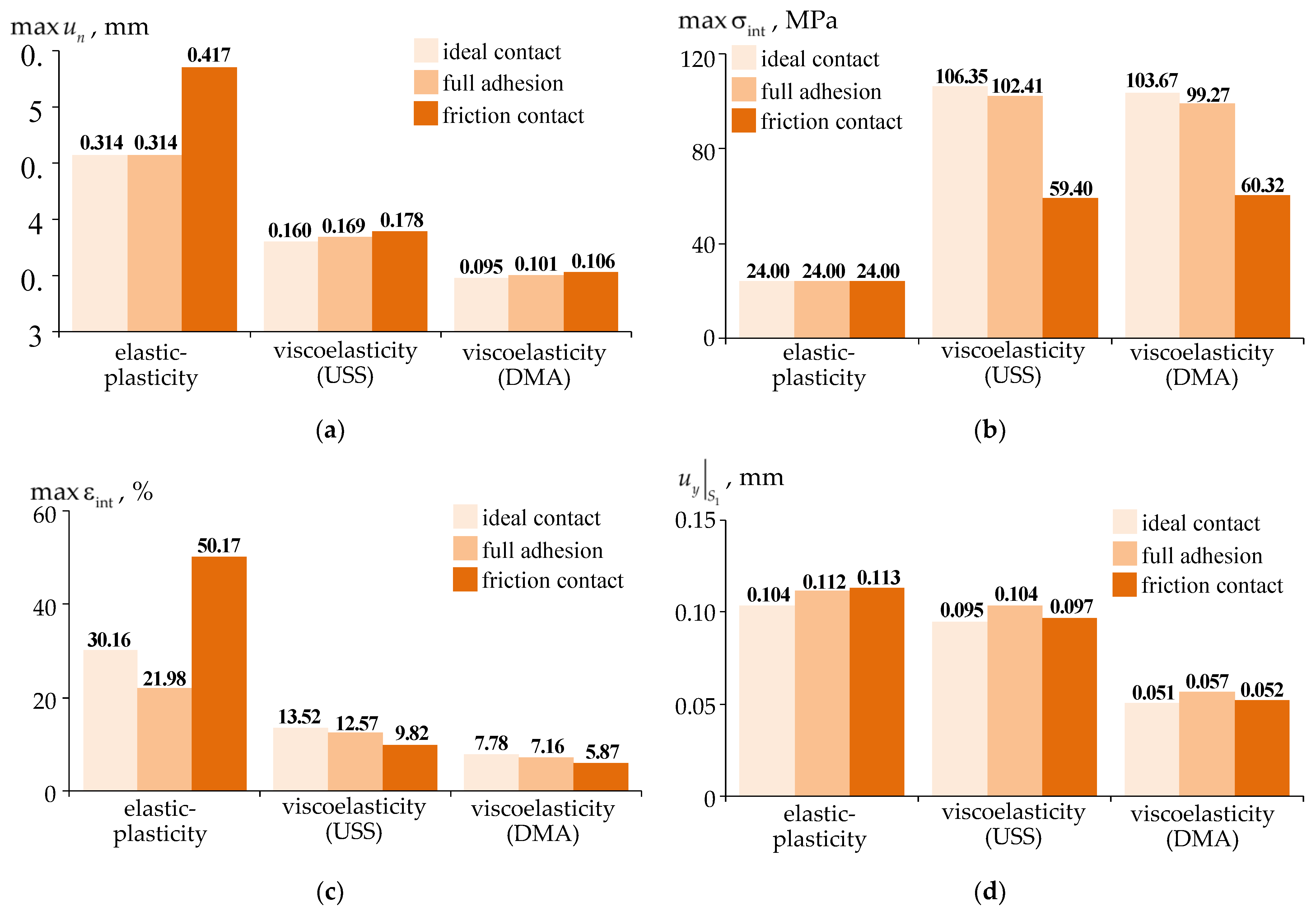

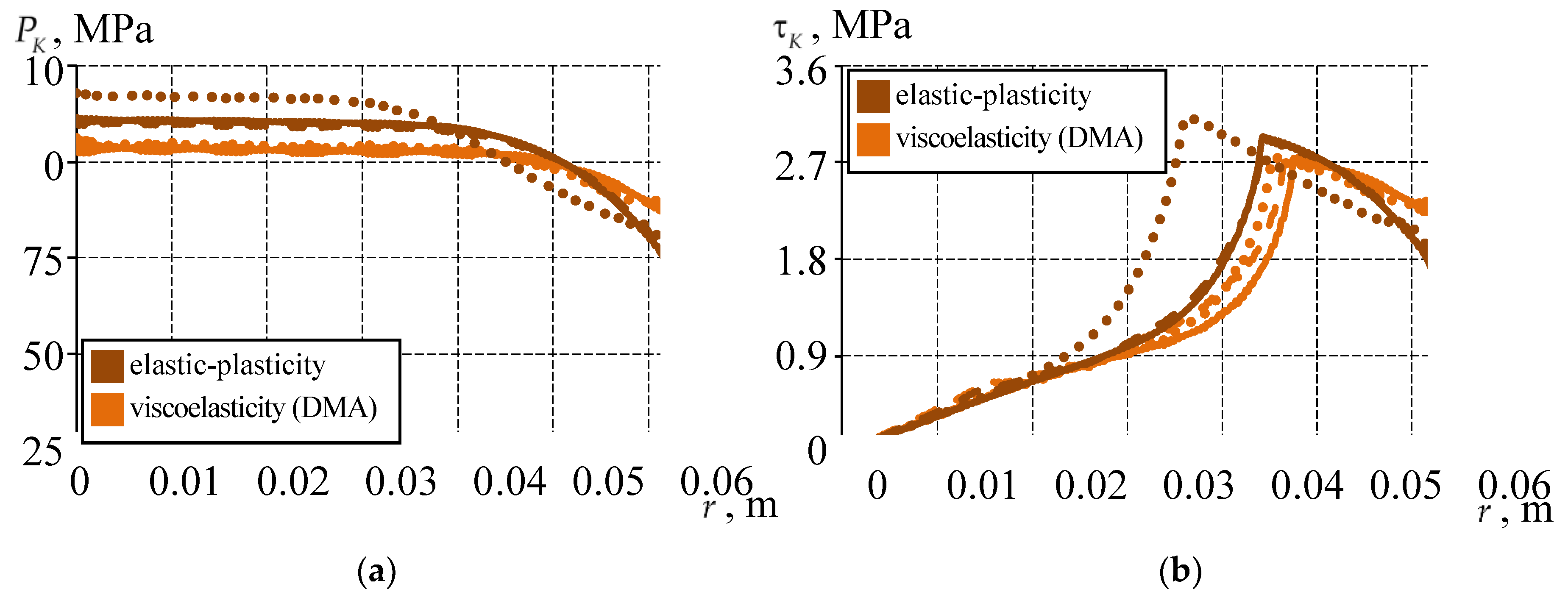

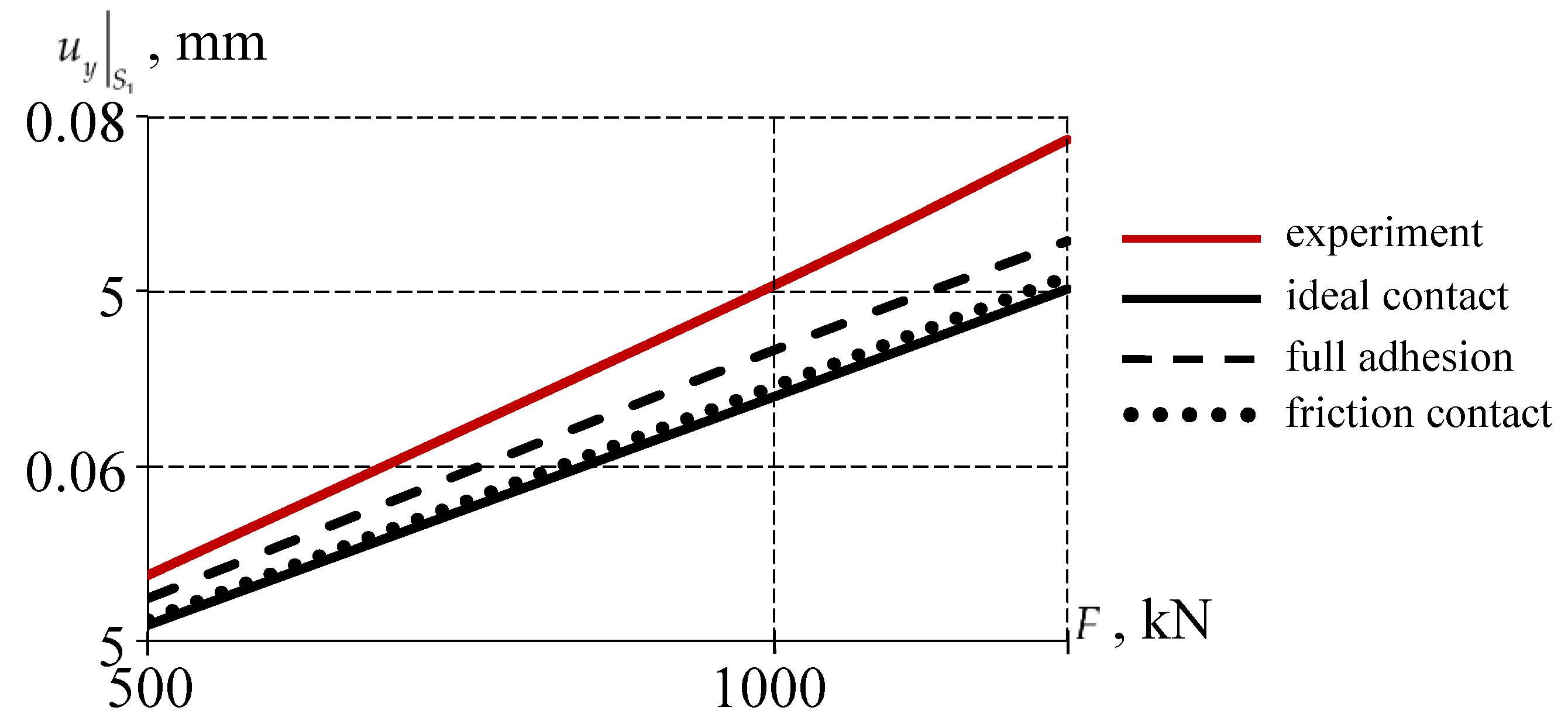

3.1. Analysis of the Effect of the Interface Pattern of the Sliding Layer with the Lower Steel Plate at a Interlayer Standard Thickness

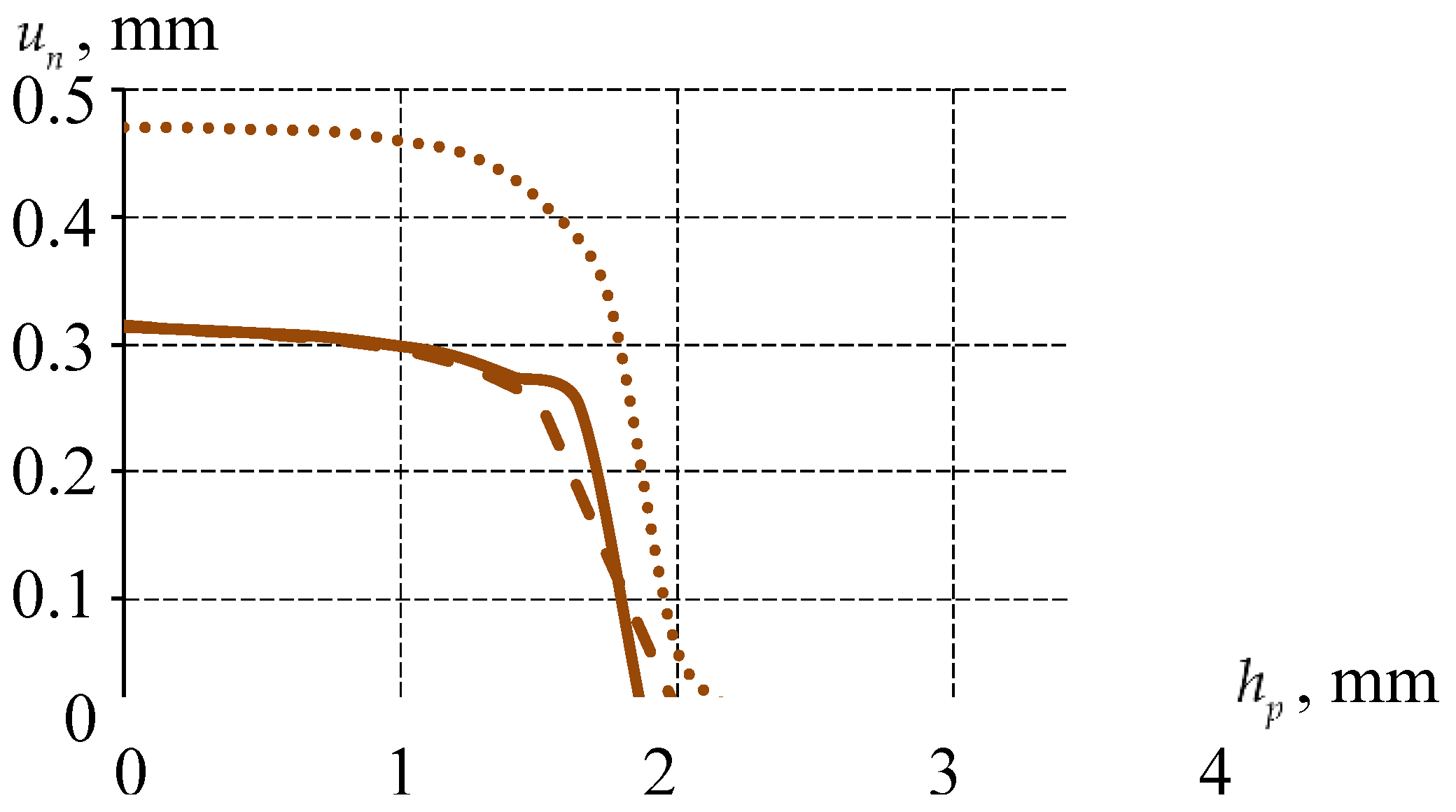

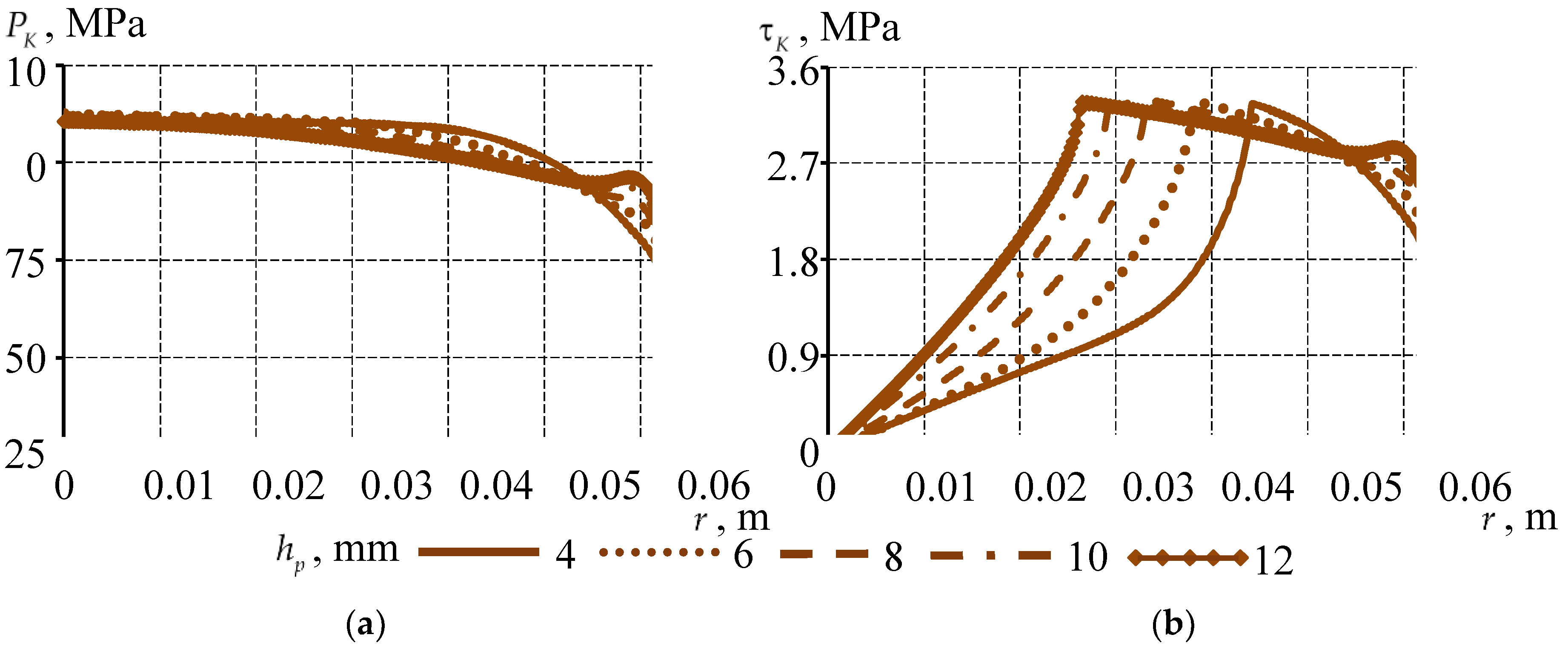

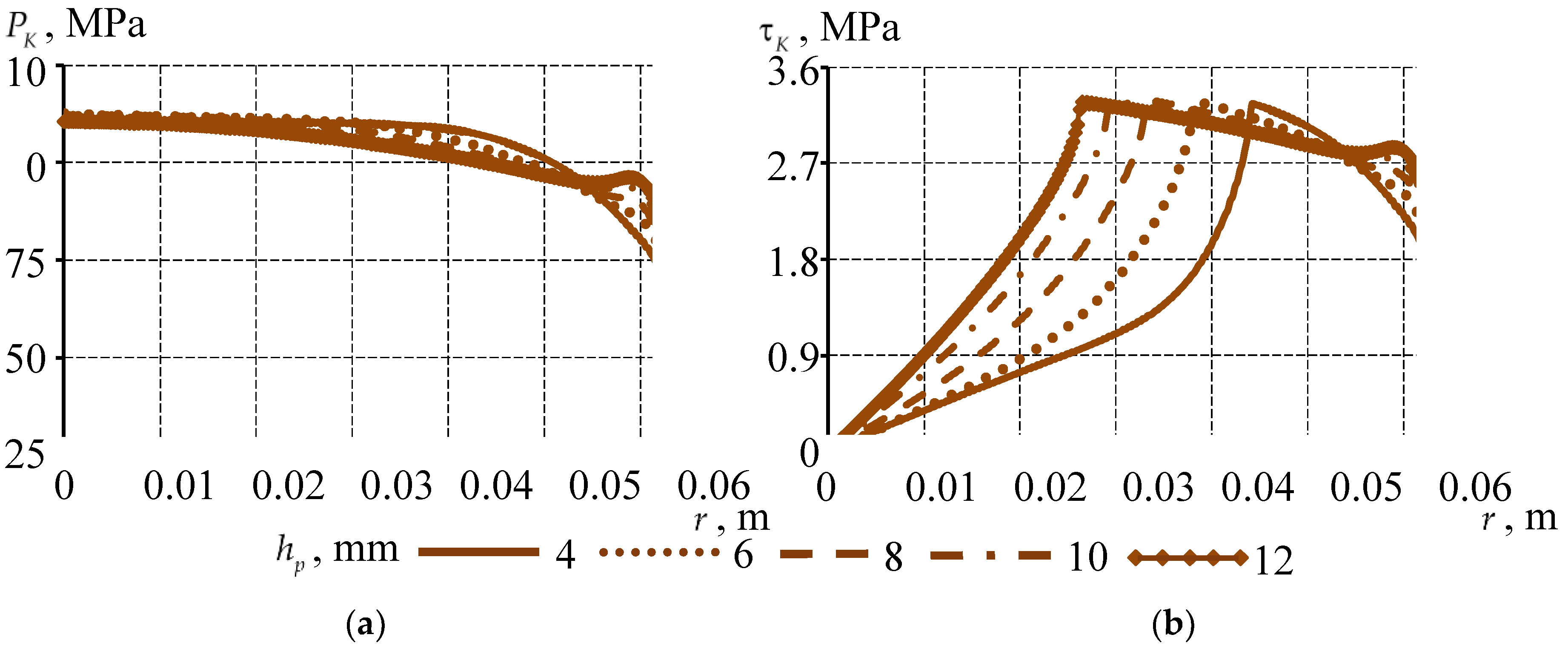

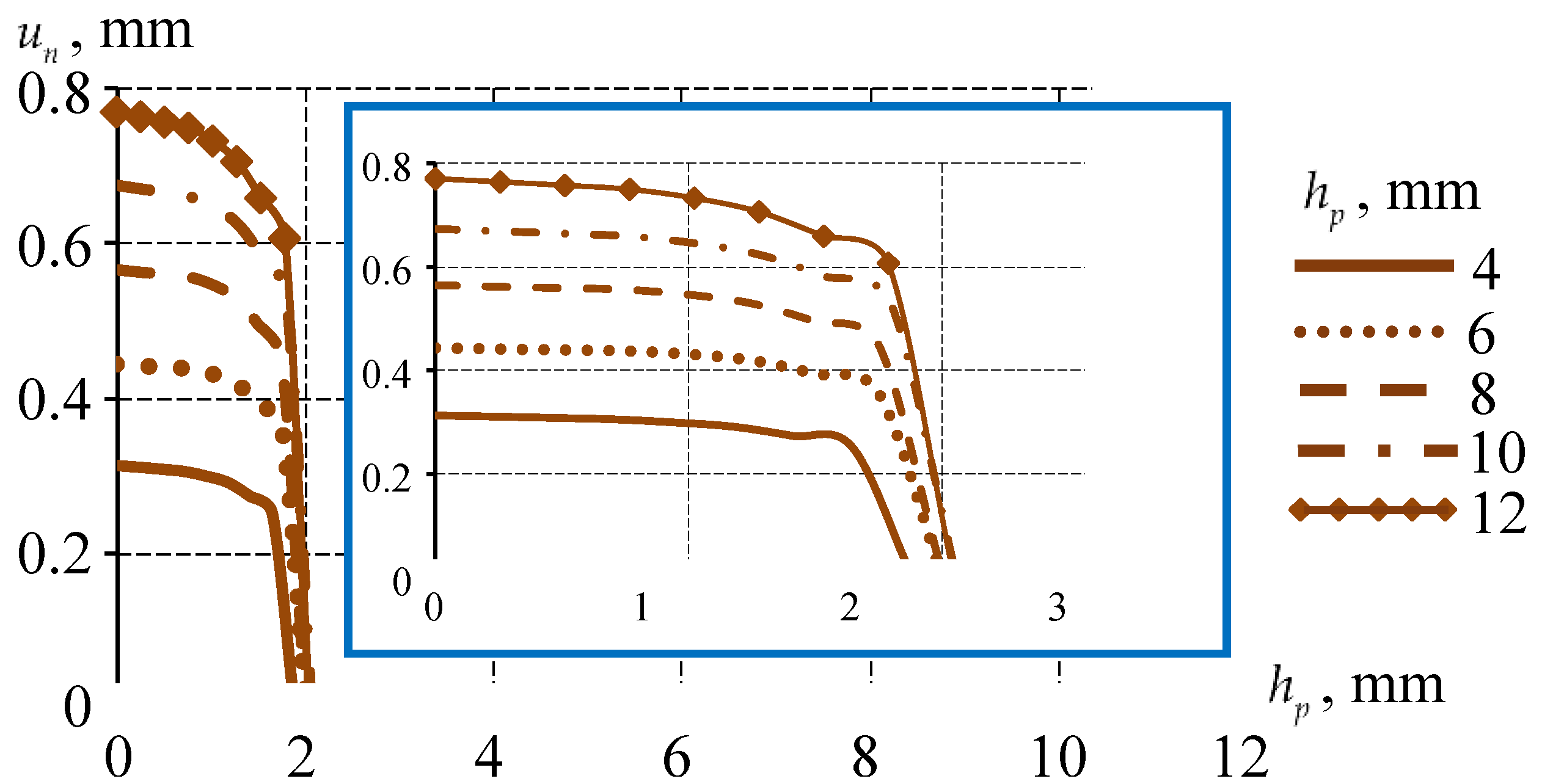

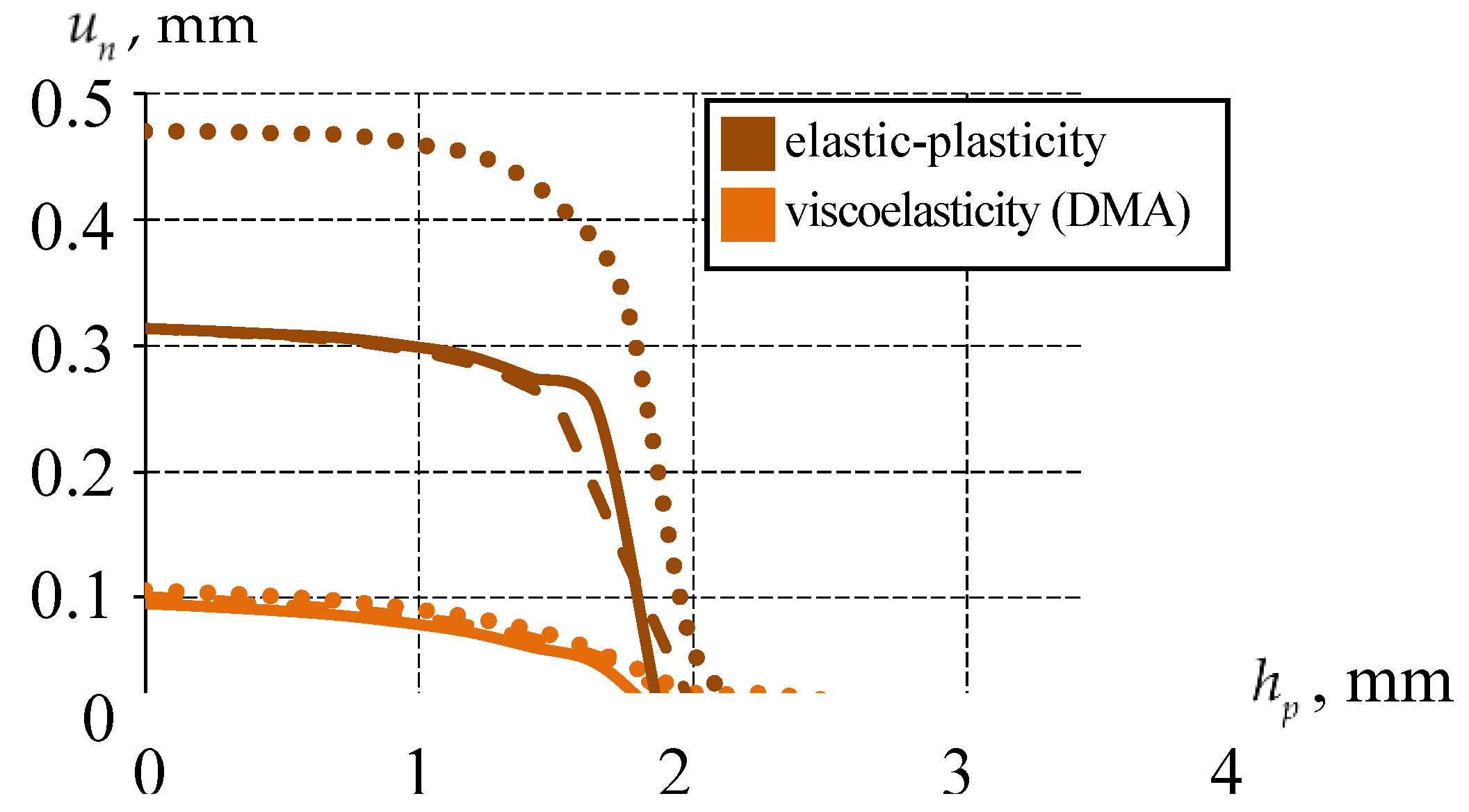

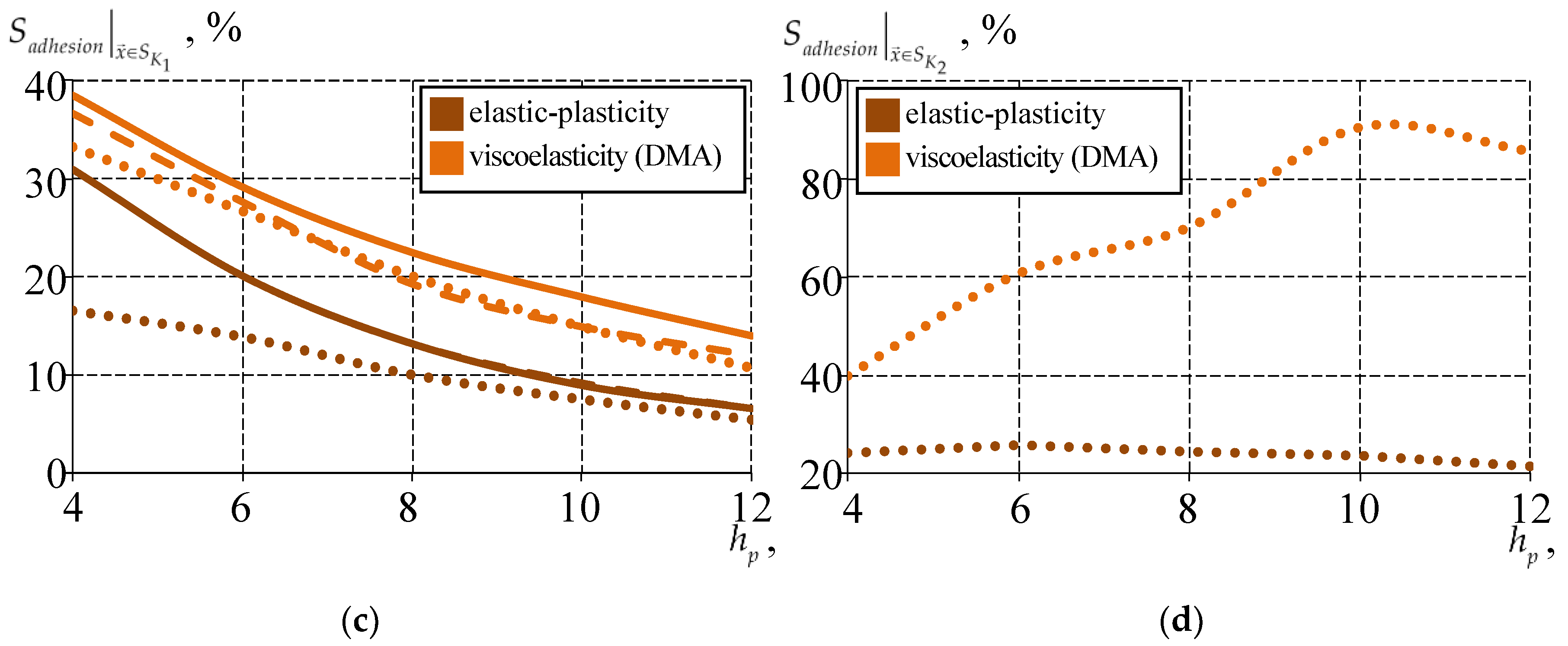

3.2. Analysis of the Effect of the Thickness of the Bearing Sliding Layer on the Structure Behavior

3.2.1. Ideal Contact Along the Interface Surfaces of the Sliding Layer with the Lower Steel Plate

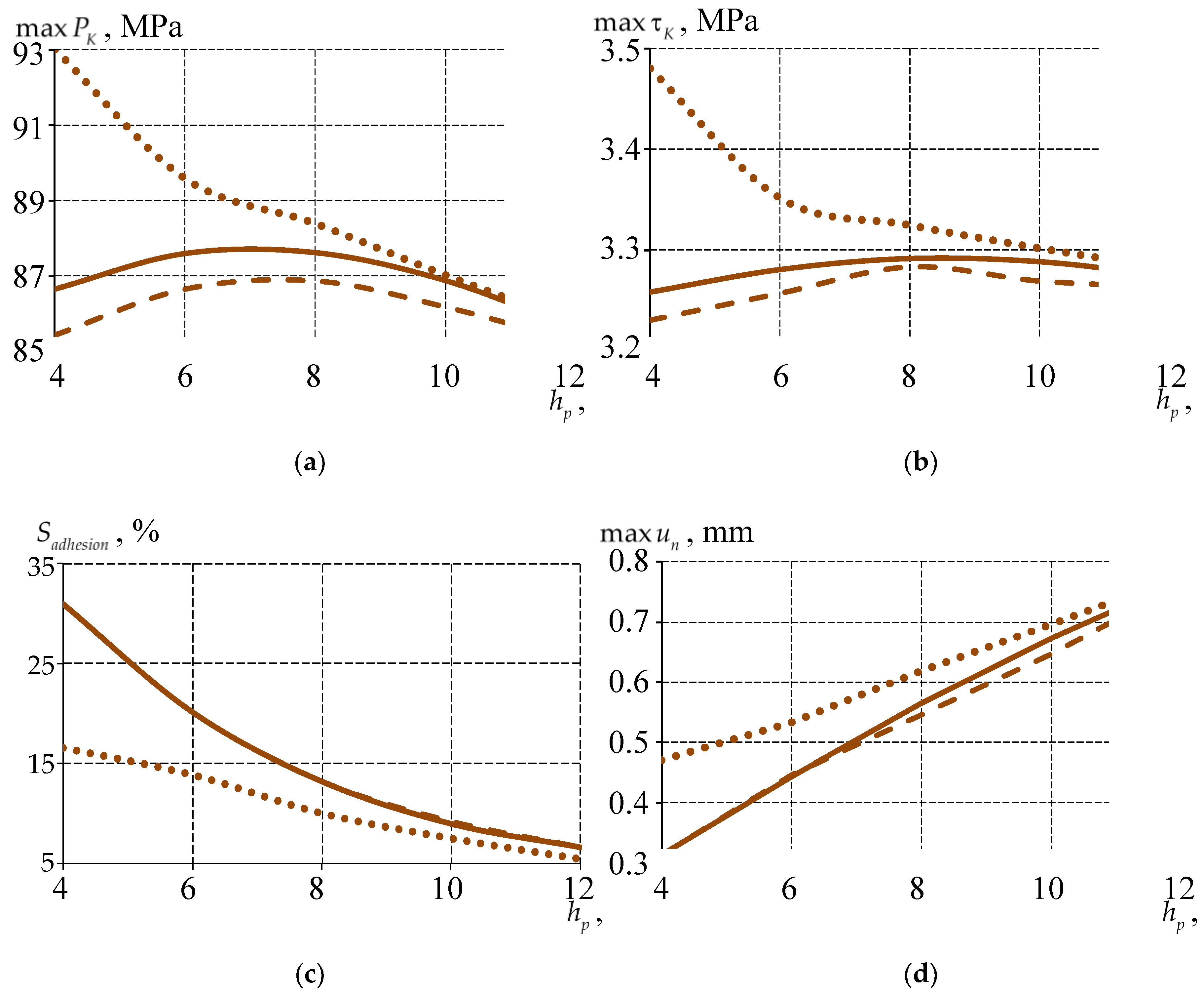

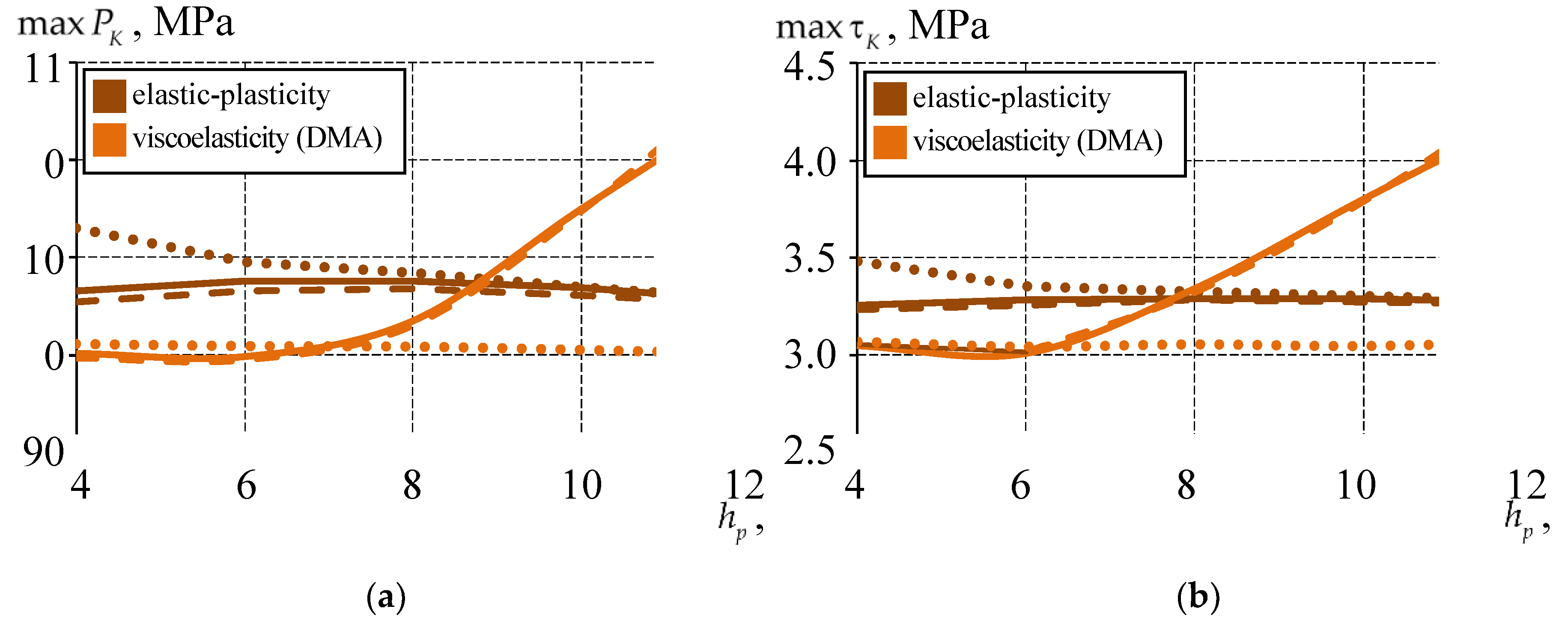

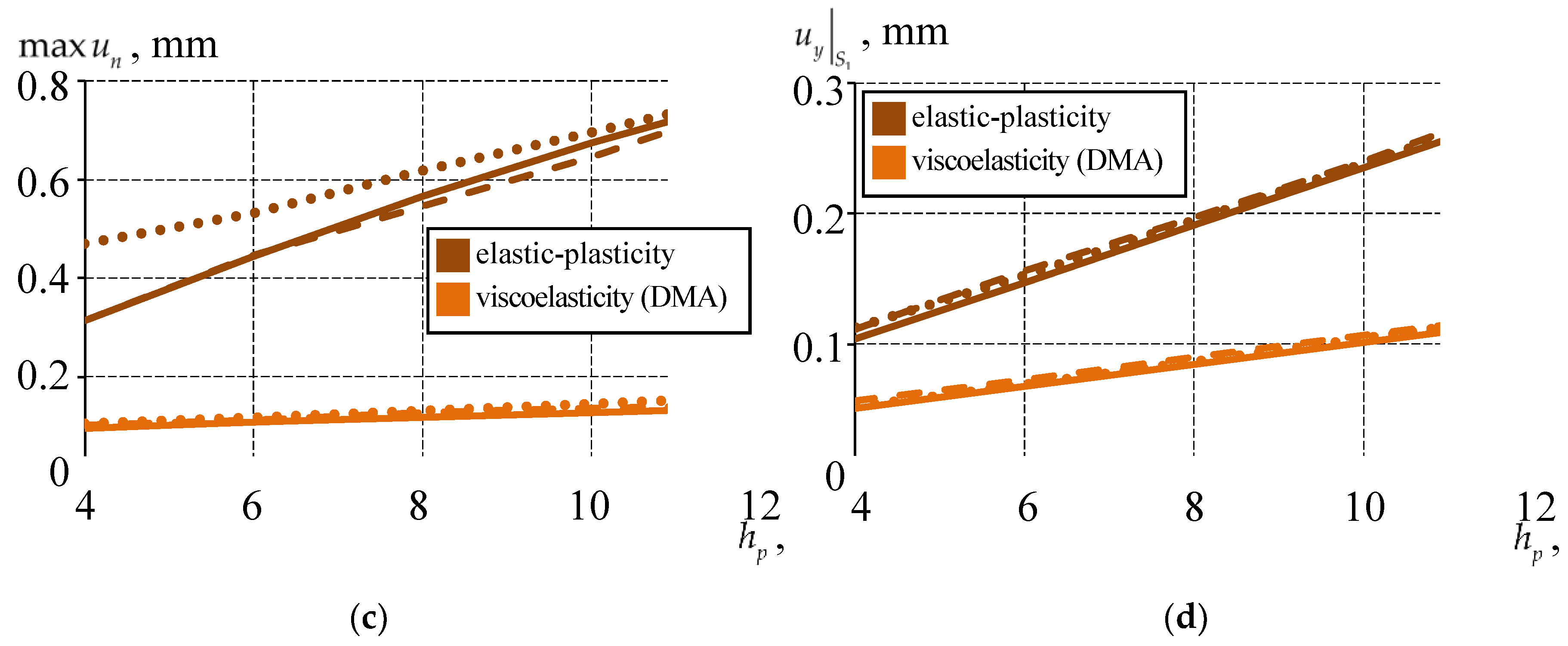

3.2.2. Comparative Analysis of the Structure Behavior at Different Thicknesses and Sliding Layer Interfaces

- The elastic-plastic model of the material behavior is based on experimental data on the free compression of cylindrical samples. The model is implemented only for the case of active loading.

- The viscoelasticity (USS) model is based on data from multi-stage tests for free compression of cylindrical samples to a maximum strain level of 10% with relaxation, unloading and recovery areas. The model is limited within the range of temperatures close to room temperatures of 22-23 ° C. It does not take into account the plasticity of the material and a number of phenomena and effects of the viscoelastic pattern of the material.

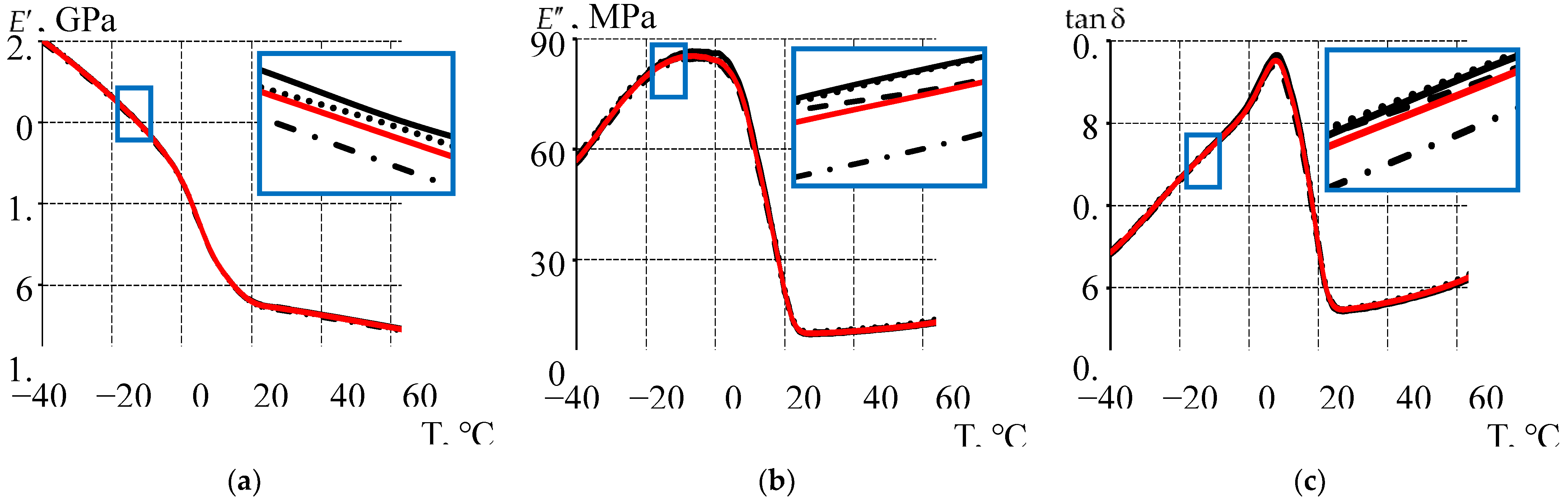

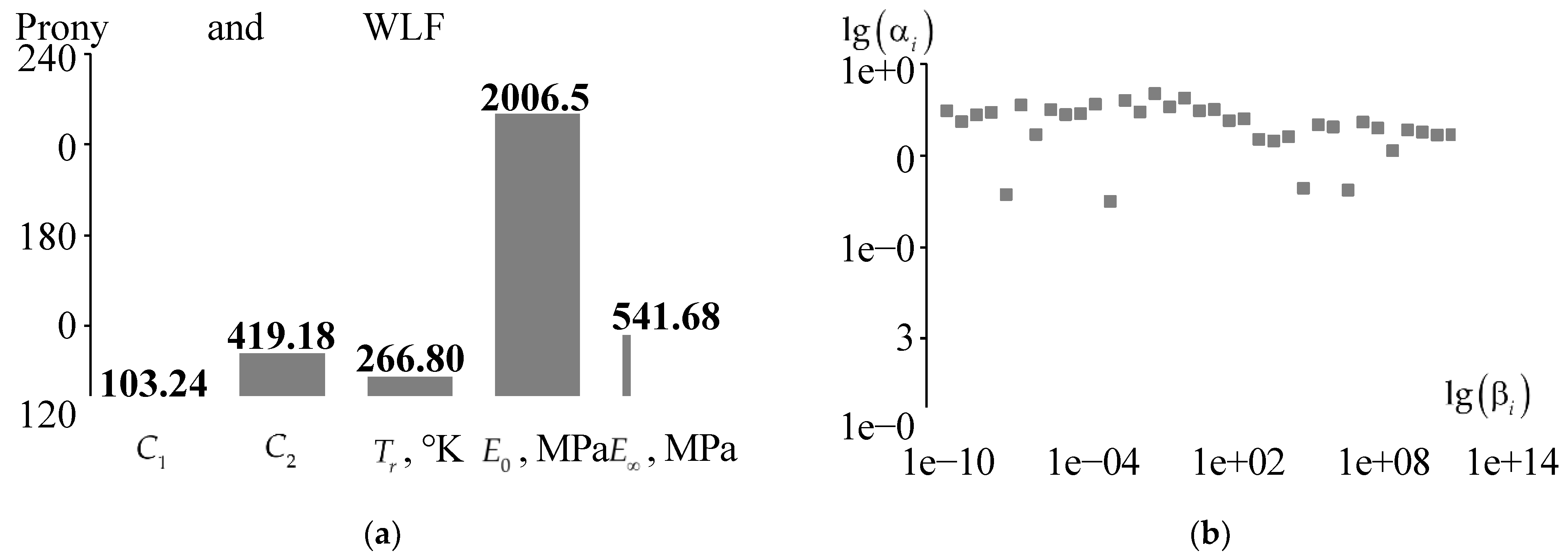

- The viscoelasticity (DMA) model is based on the entire set of experimental data, taking into account the DMA study of material behavior over a wide temperature range. The model does not take into account the plasticity of the material.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gonzalez, A.; Wiener, M.; Valdez salas, B.; & Mungaray, Alejandro. Bridges: Structures and Materials, Ancient and Modern. Infrastructure Management and Construction. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Presta, F.; Gibbens, B.; Turner, J. Sydney Gateway's Twin Network Arches: a Case Study in Complex Bridge Design and Construction. 2025, 1630-1638. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Yang, B.; Nian, Y. Study on economic design and construction program of steel-hybrid combined girder bridge. Advances in Computer and Engineering Technology Research. 2024, 1, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalaei, F.; Zhang, J.; Mcneil-Ayuk, N.; McLeod, C. Environmental life cycle assessment (LCA) for design of climate-resilient bridges–a comprehensive review and a case study. International Journal of Construction Management. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghipour, A.; Zakeri, J.; Ghozat, A.; Mosayebi, S. Dynamic Behavior Assessment of a Railway Bridge in Isfahan under Over-Height Vehicle Collision Loads and Proposing Maintenance Strategies to Enhance Its Performance. 2025, 12, 34-39. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Xia, D.; Jiang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, H.; Lin, L. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Localized Wind Effects from Terrain Variations at a Coastal Bridge Site. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, M.; Ranaldo, A.; Rosciano, M.; Zona, A.; Morici, M.; Gioiella, L.; Micozzi, F.; Poeta, A.; Quaglini, V.; Cattaneo, S.; et al. The Development and Statistical Analysis of a Material Strength Database of Existing Italian Prestressed Concrete Bridges. Infrastructures. 2025, 10, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranaldo, A.; Lo Monaco, A.; Palmiotta, A.; D’Amato, M.; Lippolis, A.; Vacca, V.; Sarno, R. A preliminary investigation on material properties of existing prestressed concrete beams. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2024, 62, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immanuel Y., Rifai A. I., Saputra A. J. Bridge Structural Design Simulation: Case Study of Nongsa Pura Bridge. OPSearch: American Journal of Open Research. 2024, V.3, №. 10, 268-276.

- Xiong, C.; Shang, Z.; Wang, M.; Lian, S. Dynamic Monitoring of a Bridge from GNSS-RTK Sensor Using an Improved Hybrid Denoising Method. Sensors. 2025, 25, 3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, R.J.; He, Q.Y.; Meng, X.L. Bridge monitoring using multi-GNSS observations with high cutoff elevations: A case study. Measurement. 2021, 168, 108303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.H.; Hyun, J.H. Evaluation of the durability of spherical bridge bearing using polyamide engineering plastic middle plate. J. Korean Soc. Urban Railw. 2021, 9, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ju, J. Study on the mechanical properties of a type of spherical bearing. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics. 2021, 59, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borisov A., I.; Gnatyuk G., A. Assessment of transport accessibility of the Arctic regions of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Transportation research procedia. 2022, 61, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarca A.; Monteiro R.; O’Reilly G. J. Seismic risk prioritisation schemes for reinforced concrete bridge portfolios. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering. 2025, V. 21, №. 1, 49-69.

- Wei, B.; Chen, M.; Jiang, L.; et al. The influence of spherical bridge bearings on train running safety during earthquakes considering train-track–bridge interaction and soil specification. Arch. Civ.Mech. Eng.25. 2025, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye X. W. et al. Analysis and probabilistic modeling of wind characteristics of an arch bridge using structural health monitoring data during typhoons. Structural engineering and mechanics: An international journal. 2017, v. 63, №. 6, 809-824.

- Yan, L.; Gou, XY.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Ran, XW.; Zhang, P. Experimental and Numerical Investigations on the Spherical Steel Bearing Capacity of New Anti-Separation Design. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering. 2024, 28(2), 889–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Xu, G.B. Research and development of universal bearing, universal rotation, antiseismic, and vibration-damping spherical bearings (in Chinese), Proceedings of the Ninth Space Structure Academic Conference, Xiaoshan. 2020; 824–829. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.Z.; Xue, S.D.; Li, X.Y. Design and mechanical properties analysis for a new type of anti-pulling spherical hinge bearing (in Chinese). Steel Construction. 2019, 34, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Sun, A.; Qi, X.; Dong, Y.; Fan, B. Experimental and analytical investigations on tribological properties of PTFE/AP composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, D.; Belgamwar, S. U.; Bekinal, S. I.; Doddamani, M. Role of reinforcement on the tribological properties of polytetrafluoroethylene composites: A comprehensive review. Polymer Composites, 2024; 45, 14475–14497. [Google Scholar]

- Berladir, K.; Antosz, K.; Ivanov, V.; Mitaľová, Z. Machine Learning-Driven Prediction of Composite Materials Properties Based on Experimental Testing Data. Polymers. 2025, 17(5), 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi X., Du S., Zhang L. Composite materials engineering, volume 1: fundamentals of composite materials. – Springer: Singapore, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q.J., Chung Y.W. Antifriction materials and composites. Springer: Boston, USA, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhang, K.; Ye, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Qu, T.; Liu, Q.; Gao, B. The effects of filler type on the friction and wear performance of PEEK and PTFE composites under hybrid wear conditions. Wear. 2022. Vol. 490–491, Art. 204178. [CrossRef]

- Abdul Samad, M. Recent Advances in UHMWPE/UHMWPE Nanocomposite/UHMWPE Hybrid Nanocomposite Polymer Coatings for Tribological Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Polymers. 2021, Vol. 13, Art. 608. [CrossRef]

- Han, O.; Kwark, J.-W.; Lee, J.-W.; Han, W.-J. Analytical Study on the Frictional Behavior of Sliding Surfaces Depending on Ceramic Friction Materials. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Lee, J.-W. Friction Behavior of Ceramic Materials for the Development of Bridge-Bearing Friction Materials. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. H., Lee, J. W., Kwark, J. W., Han, W. J., & Han, O. Characteristics of Friction Behavior of Ceramic Friction Materials according to Surface Materials. 한국건설순환자원학회논문집. 2023, 11(4), 535-541.

- Lin, S.-C. Friction and Lubrication of Sliding Bearings. Lubricants 2023, 11, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewski, M.D.; Miecznikowski, M. Assessment of the Suitability of Elastomeric Bearings Modeling Using the Hyperelasticity and the Finite Element Method. Materials 2021, 14, 7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Pei, Q.; Li, P. Reducing the Friction Coefficient of Heavy-Load Spherical Bearings in Bridges Using Surface Texturing—A Numerical Study. Lubricants 2025, 13, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Qin, L.; Dong, G. Surface texture design and its tribological application. J. Mech. Eng. 2019, 55, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P.; Wood, R.J. Tribological performance of surface texturing in mechanical applications—A review. Surf. Topogr. Metrol. Prop. 2020, 8, 043001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenk R. S. Polymer rheology. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- Kraus, M.; Niederwald, M.; Siebert, G.; Keuser, M. Rheological modelling of linear viscoelastic materials for strengthening in bridge engineering. Proceedings of the 11th German Japanese Bridge Symposium, Osaka, Japan. 2016.p. 30-31.

- Thanh Q. Nguyen; Thuy T. Nguyen; Phuoc T. Nguyen Analysis of vibration characteristics of bridge spans based on the viscoelastic material model: Investigating the relationship between material properties and dynamic parameters. Structures. 2025,108788,ISSN 2352-0124. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. Modelling the contact behaviour in the presence of viscoelasticity : Diss. – University of Leeds, 2025.

- Doh J.; Hur S.H.; Lee J. Viscoplastic parameter identification of temperature-dependent mechanical behavior of modified polyphenylene oxide polymers. Polymer Engineering and Science. 2019, Vol. 59. P. E200-E211. [CrossRef]

- Liu E., Wu J., Li H., Liu H., Xiao G., Shen Q., Kong L., Lin J. Research on viscoelastic behavior of semi-crystalline polymers using instrumented indentation. Polymer Science. 2021. Vol. 59(16). Art. 1795. [CrossRef]

- Alam M.I.; Khan D.; Mittal Y.; Kumar S. Effect of crack tip shape on near-tip deformation and fields in plastically compressible solids. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering. 2019. Vol. 41. Art. 441. [CrossRef]

- Persson B. N., J. Sliding friction: physical principles and applications. Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

- Li Y. et al. Friction characteristics and lubrication properties of spherical hinge structure of swivel bridge. Lubricants. 2024, v. 12, №. 4, p. 130.

- Adamov, A.A.; Keller, I.E.; Ivanov, Y.N.; et al. Basic Tests and Identification of a Model of Viscoelastic Behavior of Elastomers under Finite Deformations. Mech. Solids. 2024, 59, 3831–3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyin, S.O. Structural Rheology in the Development and Study of Complex Polymer Materials. Polymers. 2024, 16, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamov, A.A.; Kamenskikh, A.A. The Deformation Behavior of Modern Antifriction Polymer Materials in the Elements of Transport and Logistics Systems with Frictional Contact. In: Antipova, T., Rocha, Á. (eds) Digital Science 2019. DSIC 2019. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 1114. Springer, Cham. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Chen W. W.; Wang Q. J. Thermomechanical analysis of elastoplastic bodies in a sliding spherical contact and the effects of sliding speed, heat partition, and thermal softening. Journal of Tribology. 2008, v. 130, №. 4.

- Fang, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Tan, Y. A new universal approximate model for conformal contact and non-conformal contact of spherical surfaces. Acta Mech. 2015, 226, 1657–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.F.; Liu, T.; Peng, Z.Q.; Liu, Z.; Yin, Y.X.; Sheng, Y.Q. Stress Distribution Analysis of Sphere Hinges of Swing Bridge Based on Non-Hertz Contact Theory. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. 2018, 40, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nosov, Y.O.; Kamenskikh, A.A. Experimental Study of the Rheology of Grease by the Example of CIATIM-221 and Identification of Its Behavior Model. Lubricants 2023, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenskikh, A.A.; Nosov, Y.O.; Bogdanova, A.P. The Study Influence Analysis of the Mathematical Model Choice for Describing Polymer Behavior. Polymers 2023, 15, 3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenskih, A.A.; Trufanov, N.A. Regularities interaction of elements contact spherical unit with the antifrictional polymeric interlayer. Journal of Friction and Wear 2015, 36(2), 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeder, C.W.; Stanton, J.F.; Campbell, T.I. Rotation of High Load Multirotational Bridge Bearings. Journal of Structural Engineering 1995, 121(4), 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, N.; He, M.; Gu, N.; Liang, H. Design and Performance Research of a New Type of Spherical Force-Measuring Bearing of Bridges Based on Button Type Microsensor. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering 2024, 28, 5066–5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Liu, Z.; Guo, T.; Cai, C.S.; Jiang, C. Investigation on contact stress calculation method of spherical hinge structures for swivel construction. Structures 2024, 69, 107290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamov, A.A. , Keller I.E., Petukhov D.S., Kuzminykh V.S., Patrakov I.M., Grakovich P.N., Shilko I.S. Evaluation of the Performance of PTFE-Composites as Antifriction Layers in Supporting Parts with a Spherical Segment. Journal of Friction and Wear 2023, 44, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Sun, X.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y. Nonlinear Static Analysis of Spherical Hinges in Horizontal Construction of Bridges. Buildings 2024, 14, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).