1. Introduction

Thrombosis is characterized by abnormal clot formation within a blood vessel, obstructing blood flow and resulting from substantial imbalance between coagulation and fibrinolysis. The developed thrombotic complexes mostly comprise of red blood cells, fibrin, as well as platelets and leukocytes [

1,

2]. Although conditions such as an ischemic stroke (IS) or pulmonary embolism (PE) caused by thrombus development, are typically seen in adults, thrombosis is also a serious health complication of pediatric populations and can be classified as venous or arterial, depending on the affected vessels, with venous thromboembolism (VTE) scoring the highest rates [

3,

4,

5].

While pediatric thrombosis is considered rare, corresponding to up to 14/10,000 annual admissions, its incidence rates have demonstrated a significant increase by 70%, with a 7-fold increase only corresponding to strokes affecting newborns and children, with newborns significantly higher thrombotic rates, due to unstable hemostasis [

1,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Thrombotic incidents in pediatric patients most frequently present as cerebral thrombosis, followed by limb incidents and entail life-threatening complications, such as pulmonary embolism and post-thrombotic syndrome [

4,

8,

9], while early detection and thorough anticoagulant/thrombolytic treatment and subsequent chemoprophylaxis can be determinant to patients’ survival, complication occurrence and overall therapeutic outcomes, while thorough and multifactorial evaluation of a child’s risk is crucial for their clinical management as to prevention of secondary thrombosis, post-thrombotic syndrome, and overall recurrence [

4,

6,

8,

10].

Although pediatric thrombosis is multifactorial and its manifestation is affected by possible risk factors such as hypoxia, inflammation-involving conditions, malignancy and injury, it demonstrates a strong and well-established genetic background that increases a child’s vulnerability to thrombi formation [

9,

11,

12,

13]. Inherited thrombophilia is considered a solid risk factor in pediatric thrombosis and includes the presence of genetic variants causing functional or quantitative imbalances in factors involved in hemostasis and fibrinolysis, such as factor V (FV) Leiden, prothrombin (PTH), methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) [

11,

14]. Amongst the above, PAI-1 has recently been reported as the predominant inherited genetic risk-factor for pediatric thrombosis [

9].

PAI-1 (or SERPINE1) is the most robust inhibitor of fibrinolysis, a process that acts at the final hemostatic stage by dissolving developed thrombi, through the enzymatic activity of fibrin, thus restoring normal blood circulation [

13,

15,

16,

17]. PAI-1 is predominantly secreted by endothelial cells and negatively regulates of the fibrinolytic system by covalent binding to tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), obstructing the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, which ultimately catalyzes the degradation of fibrin, the main stabilizer of blood clots [

2,

13,

18,

19]. The ratio of tPA/PAI-1 is unfavorable for effective fibrinolysis during childhood, since tPA levels are significantly reduced at birth and until late adolescence, compared to the increased levels of its primary inhibitor PAI-1 [

19].

It has been demonstrated that increased PAI-1 levels ultimately lead to diminished fibrinolytic activity and a hypercoagulable state, therefore skyrocketing the risk of both venous and arterial thrombosis, while the generation of thrombin itself acts as an inducer of additional PAI-1 secretion [

13,

15,

16,

17,

20]. It is experimentally supported that upregulated PAI-1 levels not only promote thrombotic development, but may also contribute to resistance against thrombolytics [

19,

21].

SERPINE1 expression has been demonstrated to increase prior to thrombus development, while maximum PAI-1 levels are reached during the acute phase of thrombosis and finally decrease post treatment, which includes tPA in life-threatening incidents [

5,

15,

22,

23]. However, following a thrombotic incident PAI-1 has been shown to remain increased for prolonged periods of time, with a minimum of three months, contributing to proportional PAI-1/t-PA abnormalities and therefore decreased fibrinolytic capacity in up to 54% patients [

24].

PAI-1 levels are highly influenced by the 4G/5G (rs1799768) 1bp insertion/deletion functional polymorphism, in the promoter region of the

SERPINE1 coding gene [

15,

25,

26]. The presence of the 4G polymorphic allele in either homozygous or heterozygous state is strongly associated with higher levels of circulating PAI-1, resulting in hypofibrinolysis and coagulation promotion, while the normal 5G normal allele has been shown to exert a protective effect against thrombotic recurrence [

25,

26]. The

PAI-1 4G/5G polymorphism is reported to be the most frequently detected genetic variant within children that have undergone thrombosis, compared to other predisposing factors [

9]. Moreover, PAI-1 levels are also regulated by the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), which indirectly suppresses fibrinolysis via angiotensin II (angII) that triggers a significant PAI-1 increase [

27,

28,

29]. The angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), primarily responsible for direct angII formation, serves as the bridge between the two systems, thus acting as an indirect regulator of PAI-1. The insertion/deletion (I/D) functional polymorphism (rs1799752) of the

ACE gene is widely known for increasing circulating ACE levels in presence of the D (deletion) allele (II<ID<DD), with the DD genotype associated with maximum concentrations and enzymatic activity for angII formation [

30,

31]. The presence of the D allele and primarily DD homozygosity has also been demonstrated to indirectly increase PAI-1 levels, resulting in fibrinolytic impairment [

32]

In addition to key proteinic regulators of thrombosis, such as PAI-1, evidence has been mounting around the implication of microRNAs (miRNAs) in the delicate regulatory interplays of adult thrombosis[

33]. MiRNAs are a class of single-stranded, small (18-25nt), non-coding RNA molecules that act as profound negative regulators of gene expression at a post-transcriptional level, through the translational inhibition of mRNA targets. Each miRNA retains the capacity to regulate the expression of multiple gene-targets at once, through the binding of its seed sequence to recognized complimentary binding sites within the 3′ untranslated region (3′-UTR) of their mRNAs [

33,

34,

35] . Even after their extracellular release, miRNAs remain remarkably stable, due to their binding with Argonaute proteins and/or their encapsulation in extracellular vesicles (EVs), which provide protection against RNase-mediated degradation [

36]. Hence, and given that their expressional fluctuations (up- or down-regulation) can be highly reflective of a pathology, they hold great promise both as biomarkers, but also as crucial elements of disease pathogenicity by the abnormal regulation of the implicated genes [

34,

37].

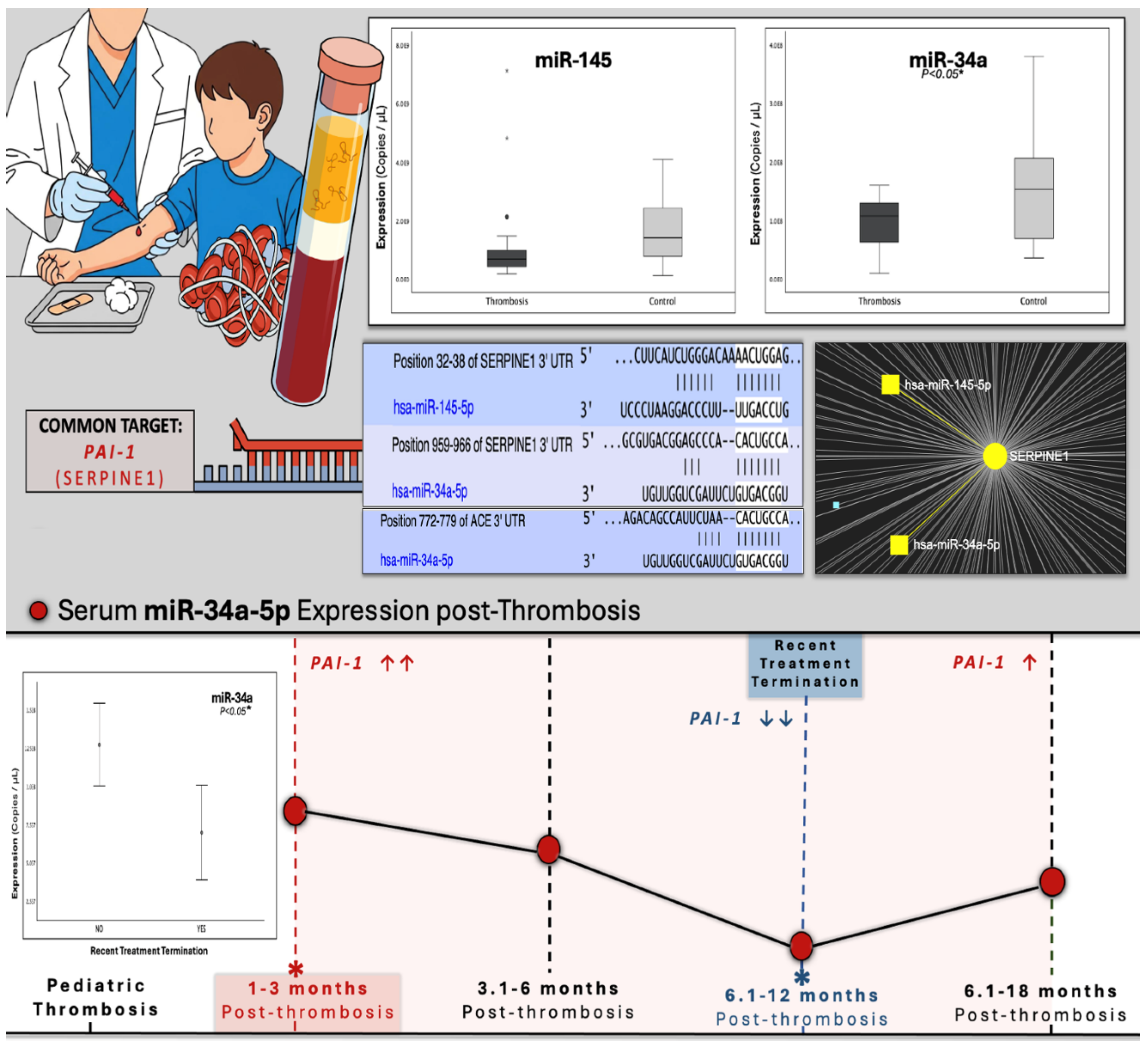

In the present study, we have examined the expression levels of two miRNAs regulators of PAI-1 (miR-145-5p and miR-34a-5p) in pediatric patients with thrombosis, 1-18 months post-incident, compared to age- and gender-matched healthy controls. Expressional patterns of the studied miRNAs were furtherly evaluated within distinct subpopulations of the patient cohort, in relation to factors such as post-thrombotic time, PAI-1 4G/5G genotypes and treatment status, which have been demonstrated to induce anticipated changes in PAI-1 levels.

This study in pediatric patients was designed under the guiding hypothesis of a possible regulatory interplay between miR-145 and miR-34a expression and

PAI-1 fluctuations, which are documented in the literature for adults [

5,

15,

22,

23], across different stages of post-thrombotic course, and treatment, as well as different genotypes of the 4G/5G functional polymorphism. The present research is, to our knowledge, the first globally to investigate miRNA expression profiles in the context of pediatric thrombosis.

4. Discussion

Childhood thrombosis, including the development of venous and arterial thrombi that obstruct circulation, is a rare condition with its etiological origins lying in the disproportionate imbalance between coagulation and fibrinolytic mechanisms [

1,

2]. Thrombotic incidents can occur at any stage during a child’s development, from the neonatal period to late adolescence, due to the interplay of environmental risk factors, including hypoxia, inflammation and injury, alongside a robust genetically-predesposing background for thrombophilia [

9,

11,

12,

13]. The above risk factors contribute to thrombosis development, in a child’s normally immature hemostatic system with a markedly low fibrinolytic capacity, compared to that of adults [

1,

4,

5,

6]. Pediatric patients that develop thrombosis come across acute life-threating or long-term complications, secondary incidents, as well as future thrombotic recurrences, typically managed through anticoagulant/fibrinolytic treatment, chemoprophylaxis, but also by a comprehensive assesment of the children’s overall risk that includes their genetic makeup [

4,

6,

8,

10].

Among the recognized genetic risk factors associated with thrombophilia,

PAI-1 (

SERPINE1) elevated gene expression has been identified as the most robust in pediatric populations affected by thrombosis [

9]. PAI-1, mainly released by endothelial cells is the predominant inhibitor of fibrinolysis, since its binding to its antagonist, tPA, thus blocking the conversion of plasminogen to active plasmin, which in turn normally degrades fibrin, a proteinic polymer that stabilizes the thrombus [

2,

13,

18,

19]. Higher levels of PAI-1 lead to hypercoagulability by diminishing fibrinolysis, thus increasing the risk for thrombus-development, while thrombin itself stimulates additional PAI-1 release in a coagulation-enhancing feedback loop [

13,

15,

16,

17,

20]. PAI-1 levels demonstrate a progressive rise a priori to the thrombotic incident, peak during the acute phase and thereafter decline after the completion of administrated treatment regimen that corresponds to successful thrombus-resolution and additional prophylaxis [

5,

15,

22,

23]. Fibrinolytic capacity of more than 50% of patients remains long-term impaired, for at least 3 months after the thrombotic event, due to PAI-1/t-PA disproportion, which can be attributable to prolonged

PAI-1 upregulation [

24].

The functional 4G/5G promoter polymorphism of the

PAI-1 (

SERPINE1) gene is strongly associated with increased circulating PAI-1 levels, leading to subsequent hypofibrinolysis and hypercoagulation, in light of the 4G allele, and has been recently demonstrated as the most common predisposing variant in childhood thrombosis, which can additionally excarbarate already impaired childhood fibrinolysis [

9,

25,

26]. Further to the functional genetic variation of

PAI-1 itself, its levels are positively mediated by the ACE, through its active proteolytic product angII, that elevates

PAI-1 expression, therefore resulting in hypercoagulability [

27,

28,

29]. The functional I/D polymorphism of the

ACE gene that elevates its expression (peaking at D homozygosity) and activity, has been strongly correlated to significant PAI increase, through upstream positive regulation [

30,

31,

32].

In addition to PAI-1, the levels of which are highly indicative of thrombotic development and progression, the implication of miRNAs in adult thrombosis is being actively explored, with highly promising results [

33]. However, their role in pediatric thrombosis remains completely uninvestigated, with no relevant studies published to far, possibly due to the rarity of the condition, which restricts sample collection and subsequent research.

In the present study we evaluated serum expression levels of miR-145-5p and miR-34a-5p miRNAs in pediatric patients aged between 0.6 and 16 years, who had undergone thrombosis during the past 1-18 months (

Table 1,

Figure 1). Within the patient cohort, we assessed the expressional profiles across distinct post-thrombotic time groups and in relation to treatment status, including recent completion of treatment or administered chemoprophylaxis. Potential associations between miRNA expression and the patients’ genotypes for the

PAI-1 4G/5G, functional polymorphism were explored. The expressional patterns of miR-34a were furtherly evaluated in relation to the family history of thrombosis, anatomical site of thrombus-development, type of onset (provoked/unprovoked), as well as in regards to

ACE I/D genotypes of the patients.

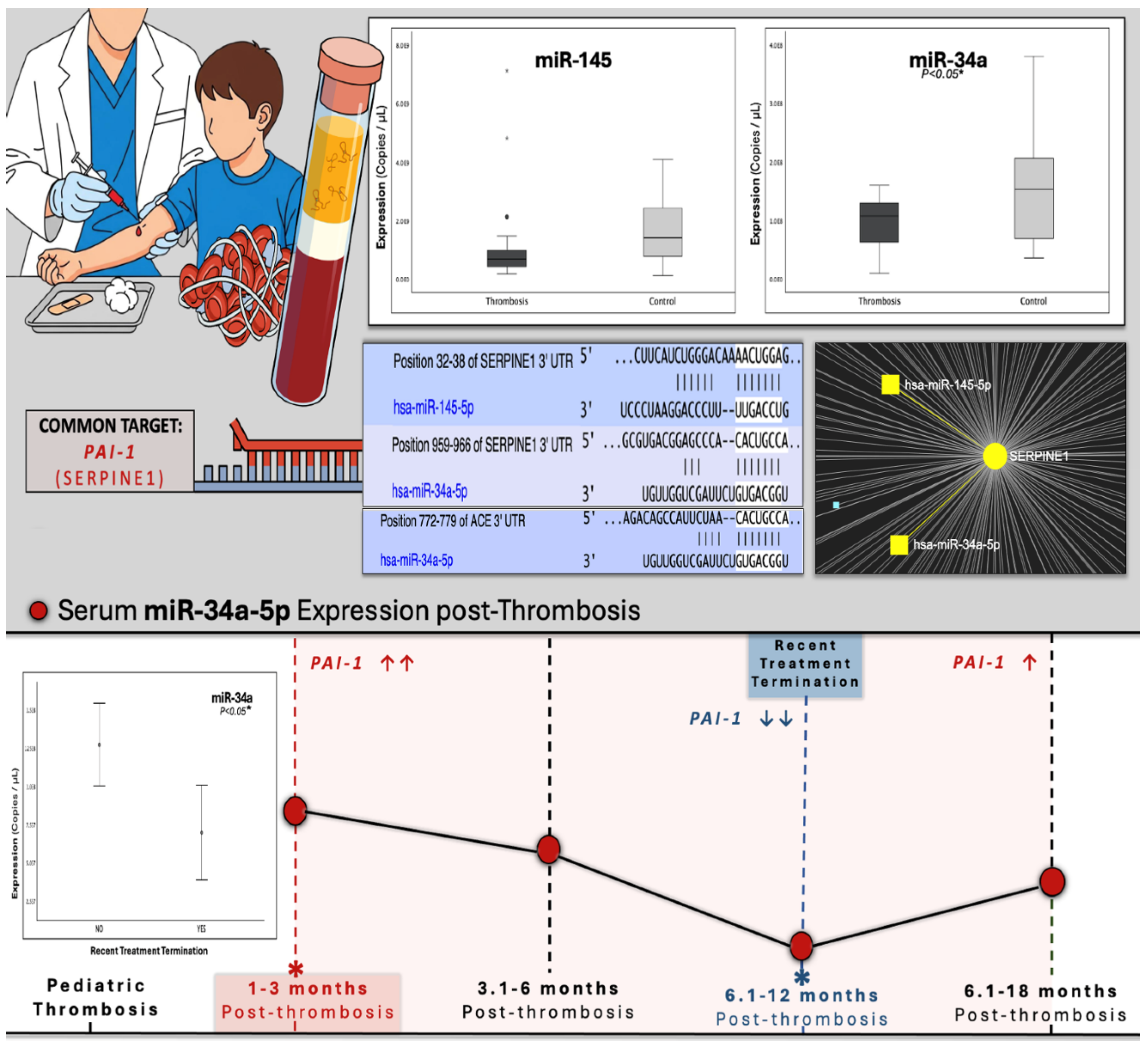

Both studied miRNAs were found to hold conserved binding sites in the 3′-UTR of the

PAI-1 gene with perfect complimentarity and have been experimentally shown to negatively regulate its expression through direct experiments. Between these two

PAI-1 regulators, miR-34a was bioinformatically shown to form an even more stable complex with

PAI-1 mRNA, and also appeared to target the mRNA of the

ACE gene as well (

Figure 1).

Following RNA extraction and reverse-transcription, the levels of miR-145 and miR-34a were quantified by real-time qPCR. Considering the characteristics of the enrolled study groups, which exhibit age heterogeneity spanning from neonatal life to adolescence and therefore encompasses different develeopmental stages, miRNA expression was evaluated through absolute quantification (copies/μL), in order to alleviate bias induced from possibly unstable reference-genes, the stability of which is required for reliable qPCR Relative-Quantification under the comparative ΔΔCt method.

The guiding hypothesis for the present research was based on an anticipated regulatory interplay between the levels of miR-145 and miR-34a expression and PAI-1 fluctuations, as documented in the literature, across different stages of thrombotic course, clinical parameters, but also different genotypes of the 4G/5G functional polymorphism of the PAI-1, which affect its levels.

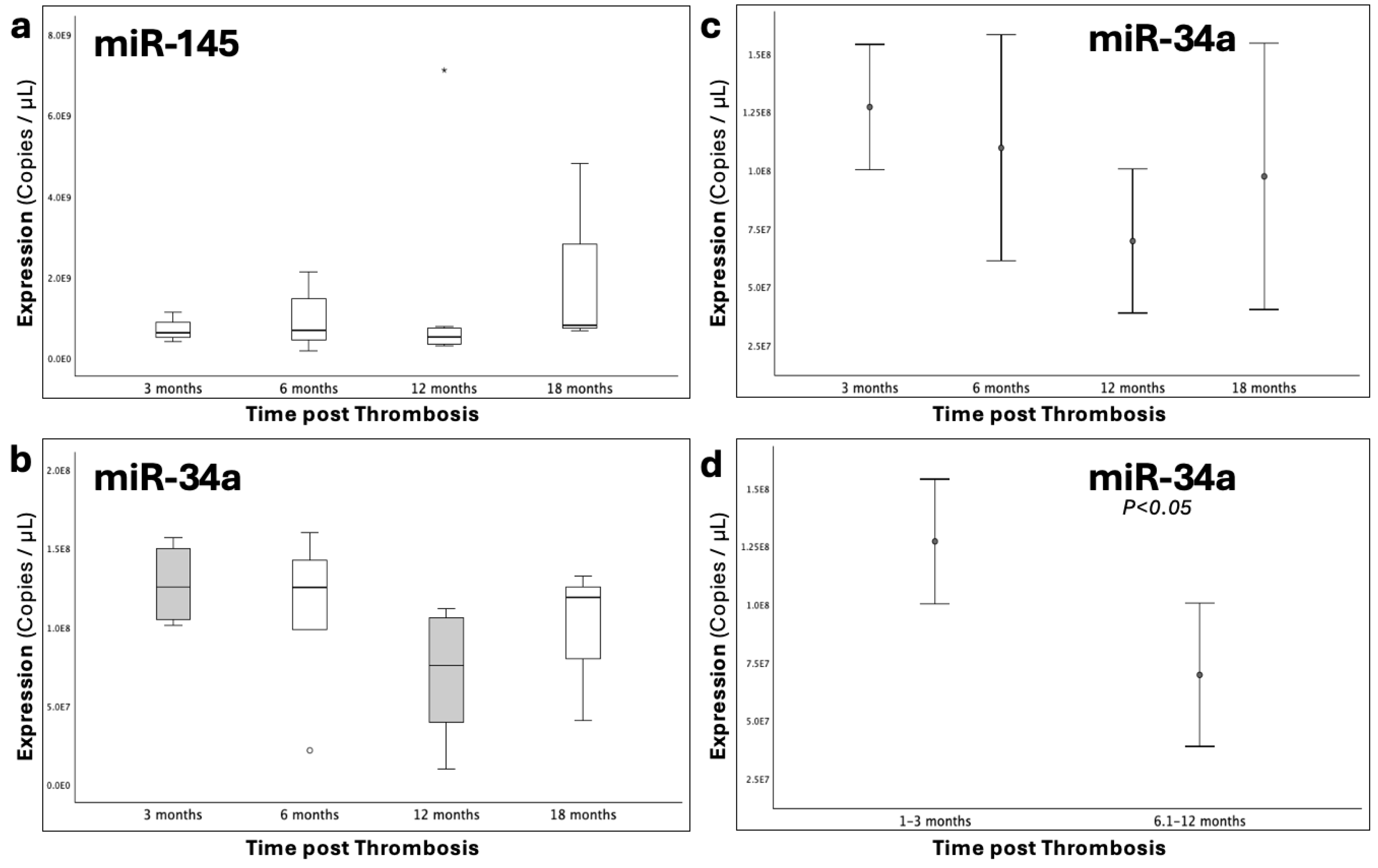

Our findings suggest that the expression of serum miR-34a was significantly reduced by approximately 40% in the patient group, compared to the studied healthy children (FC=0.61; p=0.029). On the other hand, the expression of miR-145 did not achieve statistical significance between the two groups, although exhibiting an analogous trend of downregulation (p=0.068).

In regards to different post-thrombotic time groups (

Table 1), the 1-3 and 6-12-month groups noted a significant difference, with the latter exhibiting 45%-reduced expression as to miR-34a (p=0.031). Statistical significance was not met in comparisons of the rest of post-thrombotic time intervals; nevertheless, the visual inspection of the overall miR-34a expression patterns suggested a characteristic trajectory. The highest levels within patients were observed during the 1–3-month period, which as the shortest after the thrombotic incidence and

PAI-1 expression is expected around its peak. Followingly, a gradual decline of miR-34a was observed, which ultimately reached its lowest point at 6-12 months. This expressional

nadir coincided with the recent completion of treatment or chemoprophylaxis (1-3 months) within this specific patient subpopulation, therefore aligning with the anticipated diminishing in PAI-1 levels. Thereafter, reaching the 12-18-month group, the expression of miR-34a demonstrated a subtle increase, which is 39% lower than its respective expression in the control population (

Figure 1).

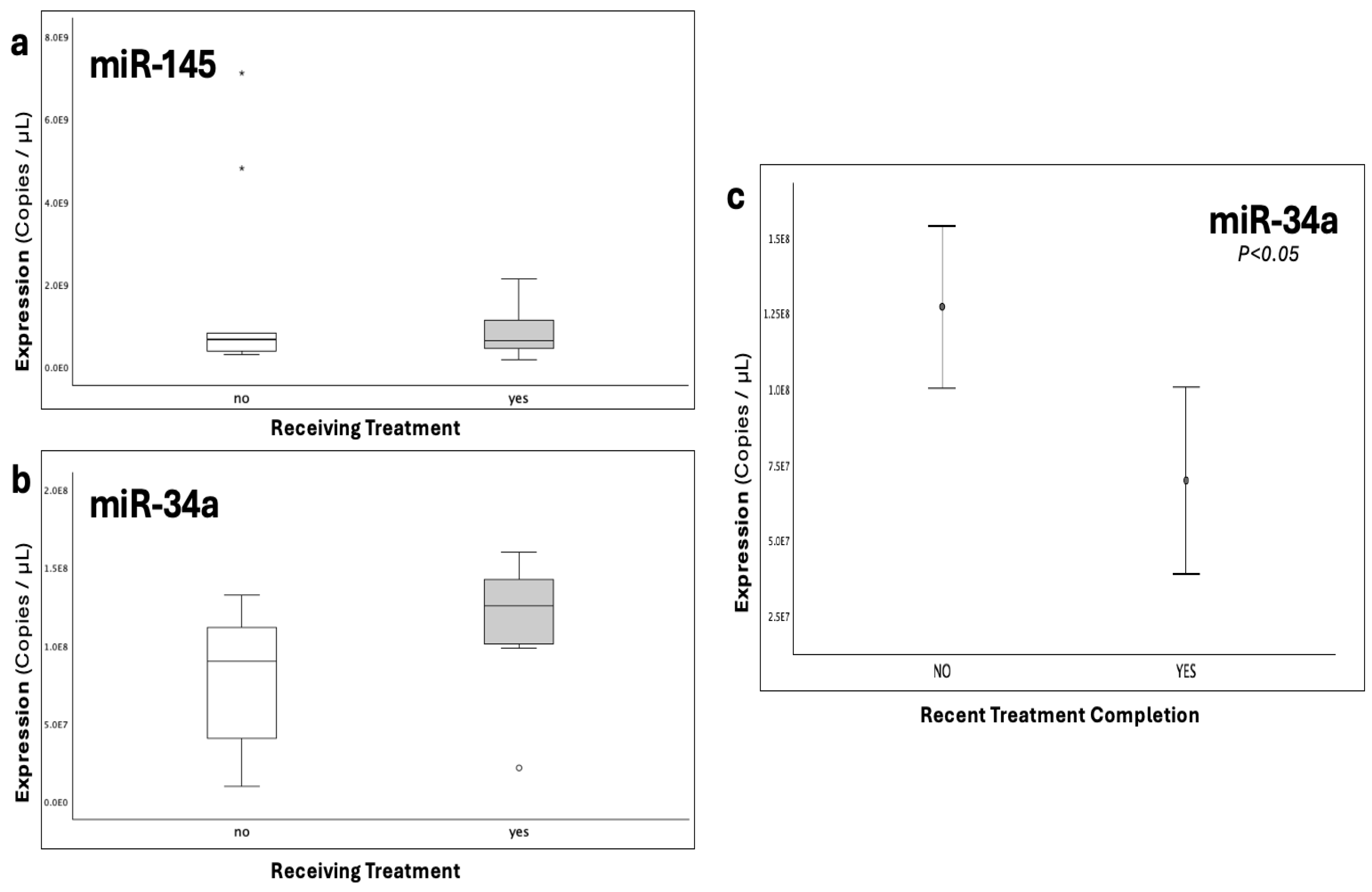

Neither ongoing treatment per se, nor the interaction of treatment and post-thrombotic time seemed to pose an influence on miRNA levels. However, the recent completion of treatment or chemoprophylaxis induced a significant 38% decrease of miR-34a levels (p=0.048), thus suggesting a temporarily dependent effect, possibly reflecting an absence of necessity for

PAI-1 regulation, owing to its typically diminished state following a successful treatment course [

5,

15,

22,

23].

Taken together, the above observations are highly consistent with a regulatory role, whereby miR-34a acts in a compensational manner, in order to reactively counterbalance the quantitative rise of its target. Its significant downregulation in the patient population compared to controls, which persists even 12-18 months post-incident and prolonged treatment discontinuation, thus suggesting a partial recovery that reflects the long-term impairment of its regulatory capacity. Further support to this conclusion comes from miRNA studies in adult thrombosis, placing miR-34a among the reactively upregulated molecules during the acute phase of thrombotic events, such as an ischemic stroke [

39,

40], where PAI-1 is known to steeply rise [

5,

15,

22,

23].

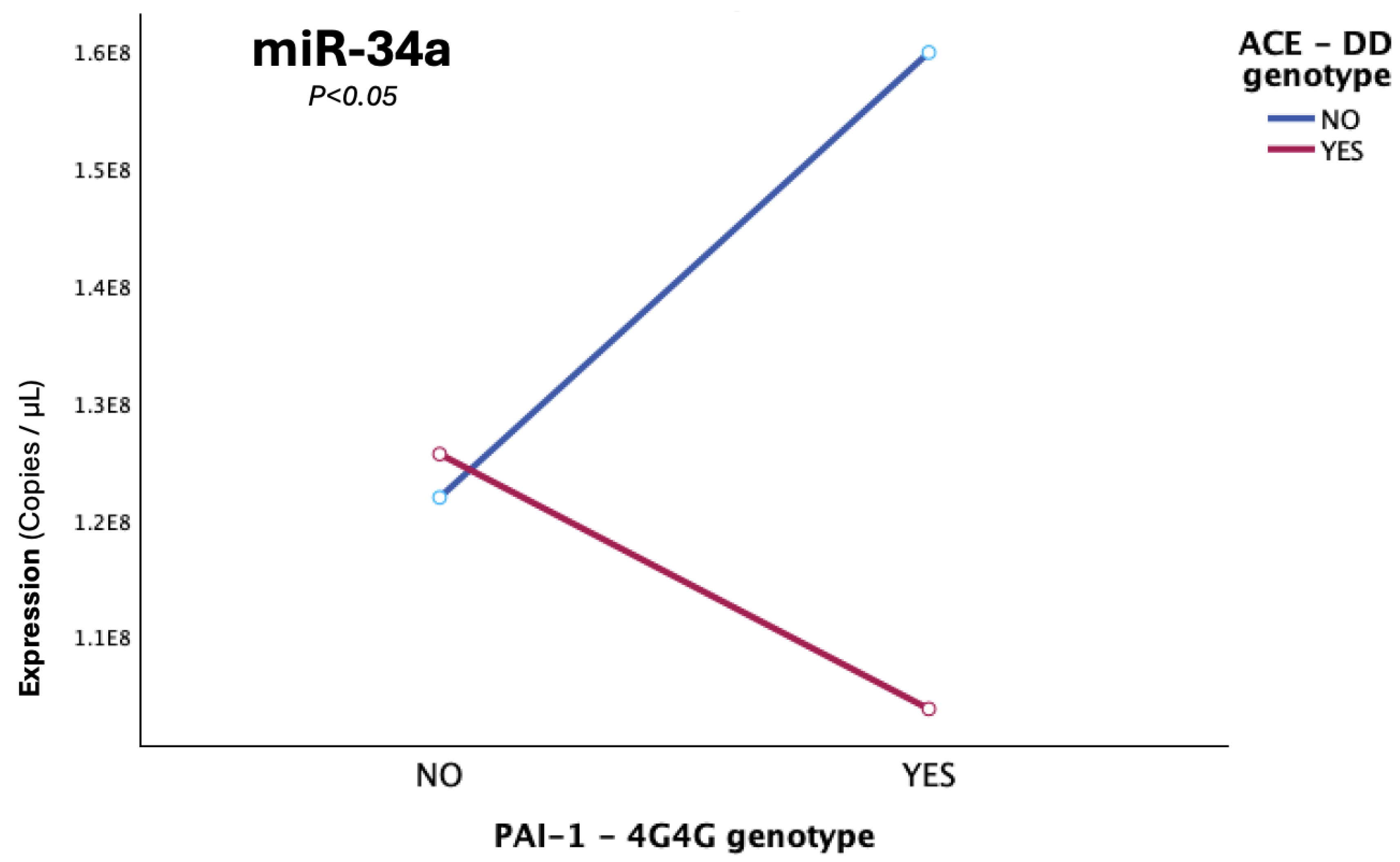

As to the possible influence of

PAI-1 genetic variability on miRNA levels, which was assessed under both general and dominant models, neither miR-145 nor miR-34a, displayed notable differences amongst the

PAI-1 genotypes for the 4G/5G polymorphism, with miR-34a however noting a mild expressional increase with rising 4G count and therefore genetically predetermined higher PAI-1 levels [

25,

26]. Although this increasing trend of miR-34a is biologically plausible, it is possible that statistical significance might have been influenced by imbalanced genotypic distributions, as 84% of patients carried at least one 4G allele, thereby not allowing for balanced group comparisons and posing an interpretational limitation.

Another limitation of the present study is the relatively small sample size, largely attributable to the rarity of cases, which may adversely affect statistical power, thereby partly elucidating the lack of significance in certain overall comparisons, despite consistent patterns and significant pairwise differences (p<0.05). Moreover, the wide dispersion in the expression values, commonly reported in miRNA studies, furtherly contributes to this matter, thus possibly reducing the power of omnibus tests (one-way ANOVA, Kruskal Wallis and Jonckheere Terpstra). Therefore, biological plausibility should be cautiously co-evaluated in light of results demonstrating contradiction between statistical significance and clearly observed trends, before definite conclusions are drawn.

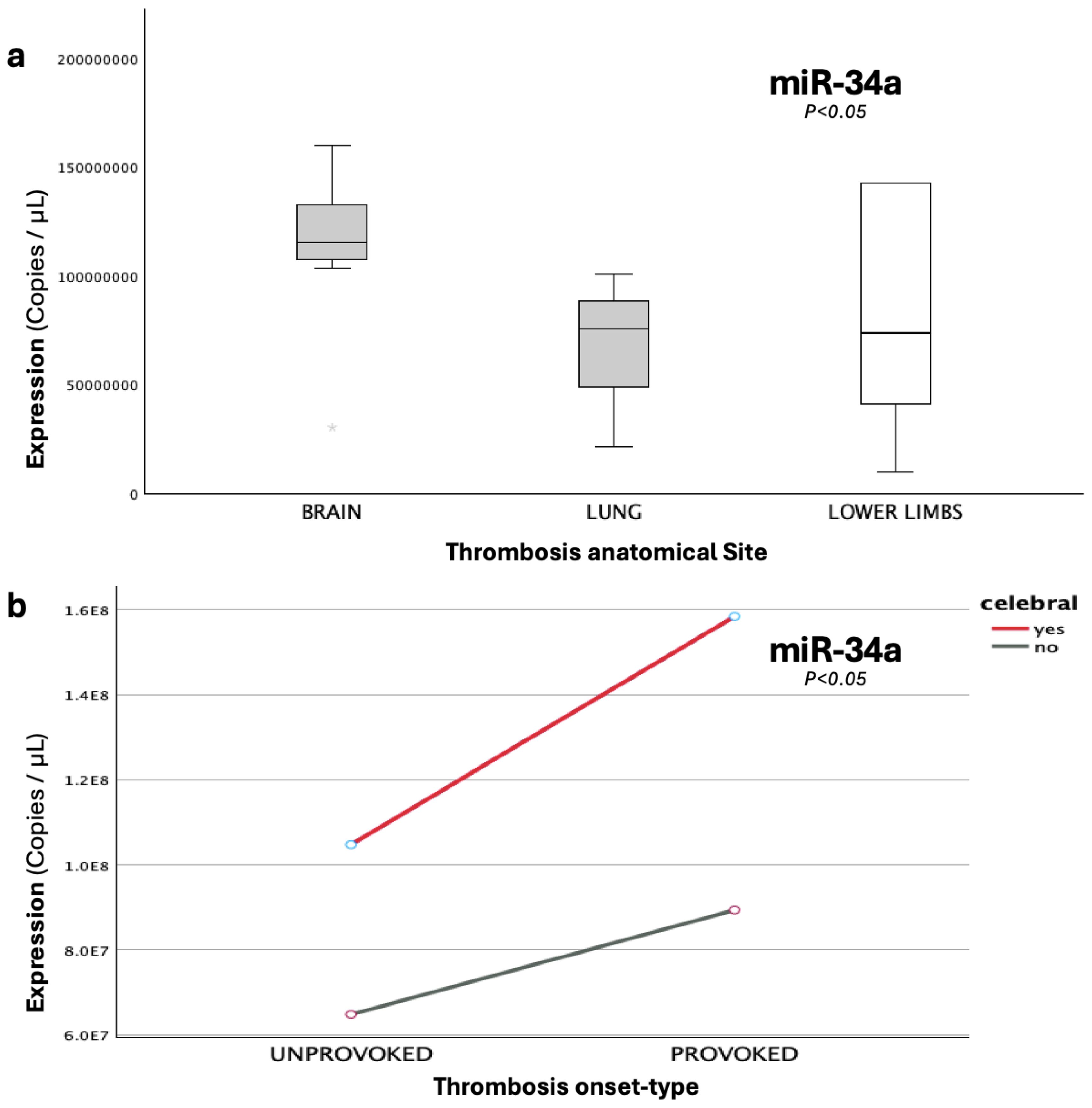

Given that miR-34a repeatedly exhibited significant and biologically plausible findings in our study, we opted to furtherly explore its observed expression within the patient population, across additional clinical and thrombosis-related genomic parameters. Its expression demonstrated a significant association with the anatomical site of the developed thrombi (p=0.019), with a peak at cerebral thrombosis, which was 76% higher compared to the expressional nadir of pulmonary embolism (p=0.007). The synergistic interaction of cerebral involvement and disease-onset type (provoked/unprovoked thrombosis) was also shown to significantly influence miR-34a levels, with post-injury cerebral strokes demonstrating a notable increase (37%) when compared to the respective cerebral unprovoked incidents, thus indicating that the onset exerts differential effects, depending on the thrombosis-affected organ.

The robust effect of injury-induced cerebral involvement is completely in line with both the established upregulation of miR-34a during the acute phase of adult ischemic-stroke, but also with its functionally-demonstrated role to epigenetically counterbalance injury-induced inflammation, thus acting as a protective mechanism [

41,

42]. In fact, not only it is strongly involved in the acute response to mechanical injury, consistent with the provoked pediatric-stroke cases we analyzed, but also its higher serum overtime-levels have been reportedly associated to successful remission in cases with spinal cord injury. The overall serum levels of injured patients were significantly downregulated compared to non-injured individuals, in accordance with our thrombosis-related overtime-findings, while their assessment has been suggested as a monitoring approach for spinal injury status [

43]. These observations agree with the expressional serum-level trajectory of miR-34a that was detected in our study, with its highest levels observed in the time period closest to the thrombotic event, reflecting a compensatory response, followed by its sharp, significant downregulation with treatment-completion, in the setting of pharmacologically induced remission, where its target pathways are externally suppressed. Finally, its tendency to increase in light of long-term absence of treatment confirms its normally protective pro-fibrinolytic role. However, the expressional decrease remains both in the initial reactive response but also long-term after thrombosis, when compared to healthy children with expectedly normal miR-34a function. The latter strongly points out the substantial inadequacy of the miRNA to normally function as an anti-thrombotic protective mechanism, through the effective regulation of the key pediatric thrombosis factor

PAI-1 and its upstream indirect activator,

ACE. This conclusion gains further strength as the overwhelming majority of studied patients (84%) carried at least one

PAI-1 4G allele, which directly increases the mainly implicated PAI-1 gene at all times, while nearly all patients (95%) harbored at least one

ACE D allele that has been renown for significantly increasing both levels and activity of its positive regulator and results in even greater levels of pro-thrombotic PAI-1. Therefore, this cannot be regarded as a solely epigenetic observation, rather than an indication of a strong genetic-epigenetic interaction, which may also reflect insight on disease-pathogenesis itself, in complete accordance with the multifactorial nature of thrombosis.

This tentative conclusion is ultimately sealed by the two final genetically-driven combinatorial findings that emerged from our data analyses. It was revealed that the manner in which miR-34a levels behaved within the patient sample not solely depended on either D-allele presence or the onset type across anatomically different thrombotic incidents, but was attributed to their three-way-interaction (p=0.035), with cerebral provoked cases that carried at least on D allele, demonstrating an almost 50% increase in miR-34a expression compared to cerebral unprovoked cases carrying the normal II ACE-lowering genotype, while a tremendous 5.2-fold expressional increase in miR-34a levels was observed when compared to unprovoked non-cerebral incidents (PE or lower-limb thrombosis).

The final and highly significant combinatorial finding involves the interaction of genetic epistasis with an environmental driver that contributes to an apparently already-impaired epigenetic dysregulation and accounts for nearly 50% of miR-34a expressional heterogeneity in the studied patient-sample. The abundance of miR-34a is highly dependent on the three-way interaction between PAI-1 4G homozygosity, ACE D homozygosity and cerebral thrombotic involvement (p=0.006). It was shown that double homozygotes (4G4G + DD) exhibited the lowest levels of miR-34a expression, which additionally reflects the deficiency of miR-34a to adequately increase in light of two genetically predisposed, upregulated targets, with a thrombosis-promoting synergistic effect. The epistatic interaction of the two genes on miR-34a expression was clearly elucidated in light of a complete reverse in miRNA expression in 4G4G carriers lacking the DD homozygosity, whose miR-34a levels were the maximum observed. Hence, the ability of the 4G allele of the PAI-1 gene to exert an anticipated substantial increase on miR-34a levels is not autonomous but emerges only in absence of ACE DD genotype, which acts as the genetic switch. This leads to the conclusion that probably, only in light of double 4G4G + DD homozygosity, where the maximum possible resultant levels of PAI-1 are secreted, the already impaired miR-34a, which is significantly lower to post-thrombotic patients than controls, although not quantitatively enough, is forced to regulate both increased targets that synergistically lead to PAI-1 overflooding. This inadequate response allows for ultimate fibrinolytic dysregulation in children with genetically-determined thrombophilia, which when combined with their immature hemostatic system can pave the way for thrombosis development.

This possibly defective regulation could also provide a mechanistic hint that miR-34a might normally function as a regulatory “emergency brake” in thrombosis driven by PAI-1-induced hypofibrinolysis. By failing to adequately control the expression of PAI-1 due to its insufficient expression, it allows for its target’s unchecked elevation, which is already renown to drive thrombosis development.

Moreover, our findings suggest that the genetic epistasis between

ACE and

PAI-1 (4G4G + DD) as the main determinant for lack of the normally anticipated anti-thrombotic response of miR-34a, might provide a combinatorial genetic/epigenetic predisposing profile, which is highly possible to account for thrombosis development, by acting as a multivariate, molecular switch in light of an environmental trigger, such as injury. This conclusion is furtherly supported by the fact that

PAI-1 4G/5G polymorphism has been recognized as the predominant risk factor for childhood thrombophilia among many established risk factors that are considered much more important in adult thrombosis [

9]. Since to our knowledge the present exploratory piece of research is the first so far conducted in the context of pediatric thrombosis and miRNA profiling, we anticipate that it will lay the groundwork for the future broadening of predisposition from a solely genetic term to a genetic/epigenetic dynamic concept.

Figure 1.

Graphical abstract of study design and key findings upon miR-34a expression in pediatric post-thrombotic course, as well as visualized outputs from target-prediction in-silico analyses (Targetscan, miRNet) presented alongside experimental results. Bioinformatic analyses revealed. Target-prediction analyses yielded that miR-145-5p and miR-34a-5p hold conserved binding sites on the 3′-UTR of SERPINE1 (PAI-1) mRNA, both scoring perfect complementarity of the miRNA seed region, while in the case of miR-34a, mRNA binding exhibits possibly increased stability due to the presence of an adenine (A), opposite of miRNA position 1 of the seed sequence. MiR-34a additionally holds a 7/7 binding site on the 3′ UTR of the mRNA of the ACE gene, which codes for the upstream positive regulator of PAI-1. opposite to seed-sequence position 1. The expression of miR-34a was significantly decreased in patients, compared to controls, while no difference was observed for the levels of miR-145, between the two studied cohorts. The lower panel presents a combinatory graph that illustrates the expressional trajectory of miR-34a across the post-thrombotic course with a peak at 1-3 months post-thrombosis, a time when PAI-1 is anticipated to be significantly increased. Its expression follows a gradual decline and finally a nadir, shortly after treatment-completion, when PAI-1 has been demonstrated to diminish. At the long-term post-thrombotic stage of 12-18 months, where PAI expression is expected recover, miR-34a strikes a slight, non-significant increase reaching lower levels than those of the studied controls. These findings are indicative of a dynamic, yet impaired regulatory relationship between miR-34a and PAI-1, as well as its upstream controller ACE. Hence, the downregulation of miR-34a in pediatric thrombosis might possibly lead to deficient fibrinolytic capacity through the inadequate suppression of the antifibrinolytic ACE/PAI-1 axis, the upregulation of which is critical for thrombosis development.

Figure 1.

Graphical abstract of study design and key findings upon miR-34a expression in pediatric post-thrombotic course, as well as visualized outputs from target-prediction in-silico analyses (Targetscan, miRNet) presented alongside experimental results. Bioinformatic analyses revealed. Target-prediction analyses yielded that miR-145-5p and miR-34a-5p hold conserved binding sites on the 3′-UTR of SERPINE1 (PAI-1) mRNA, both scoring perfect complementarity of the miRNA seed region, while in the case of miR-34a, mRNA binding exhibits possibly increased stability due to the presence of an adenine (A), opposite of miRNA position 1 of the seed sequence. MiR-34a additionally holds a 7/7 binding site on the 3′ UTR of the mRNA of the ACE gene, which codes for the upstream positive regulator of PAI-1. opposite to seed-sequence position 1. The expression of miR-34a was significantly decreased in patients, compared to controls, while no difference was observed for the levels of miR-145, between the two studied cohorts. The lower panel presents a combinatory graph that illustrates the expressional trajectory of miR-34a across the post-thrombotic course with a peak at 1-3 months post-thrombosis, a time when PAI-1 is anticipated to be significantly increased. Its expression follows a gradual decline and finally a nadir, shortly after treatment-completion, when PAI-1 has been demonstrated to diminish. At the long-term post-thrombotic stage of 12-18 months, where PAI expression is expected recover, miR-34a strikes a slight, non-significant increase reaching lower levels than those of the studied controls. These findings are indicative of a dynamic, yet impaired regulatory relationship between miR-34a and PAI-1, as well as its upstream controller ACE. Hence, the downregulation of miR-34a in pediatric thrombosis might possibly lead to deficient fibrinolytic capacity through the inadequate suppression of the antifibrinolytic ACE/PAI-1 axis, the upregulation of which is critical for thrombosis development.

Figure 2.

The graphs depict the expression (copies/μL) of (a), miR-145-5p and (b), miR-34a-5p that was studied in serum samples of pediatric thrombosis patients (1-18 months post-incident) and healthy controls. It was shown that miR-34a was significantly downregulated (p<0.05) in the patient population compared to controls, while the expression of miR-145-5p exhibited no statistical difference between the two groups.

Figure 2.

The graphs depict the expression (copies/μL) of (a), miR-145-5p and (b), miR-34a-5p that was studied in serum samples of pediatric thrombosis patients (1-18 months post-incident) and healthy controls. It was shown that miR-34a was significantly downregulated (p<0.05) in the patient population compared to controls, while the expression of miR-145-5p exhibited no statistical difference between the two groups.

Figure 3.

Graphs depicting the expression (copies/μL) of (a), miR-145-5p and (b), miR-34a-5p that was studied across four time-groups following thrombosis occurrence. (c), Error bars of miR-34a expression across all time-groups, highlighting its trajectory through the post-thrombotic course and (d), the comparison between the 1-3 and 6-12 time-groups. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Figure 3.

Graphs depicting the expression (copies/μL) of (a), miR-145-5p and (b), miR-34a-5p that was studied across four time-groups following thrombosis occurrence. (c), Error bars of miR-34a expression across all time-groups, highlighting its trajectory through the post-thrombotic course and (d), the comparison between the 1-3 and 6-12 time-groups. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Figure 4.

Boxplots depicting the expression (copies/μL) of (a), miR-145-5p and (b), miR-34a-5p that was studied across genotypic groups for the 4G/5G functional polymorphism of the PAI-1 gene, which increases the expression of PAI-1 in light of the 4G allele.

Figure 4.

Boxplots depicting the expression (copies/μL) of (a), miR-145-5p and (b), miR-34a-5p that was studied across genotypic groups for the 4G/5G functional polymorphism of the PAI-1 gene, which increases the expression of PAI-1 in light of the 4G allele.

Figure 5.

The graphs depict the expression (copies/μL) of (a), miR-145-5p and (b), miR-34a-5p across patient subgroups receiving and not actively receiving treatment following thrombosis. c), Error bars of miR-34a expression between patients that had recently completed treatment regimen (1-3 months), and patients either actively receiving or having long-term terminated treatment course. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Figure 5.

The graphs depict the expression (copies/μL) of (a), miR-145-5p and (b), miR-34a-5p across patient subgroups receiving and not actively receiving treatment following thrombosis. c), Error bars of miR-34a expression between patients that had recently completed treatment regimen (1-3 months), and patients either actively receiving or having long-term terminated treatment course. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Figure 6.

The graphs present the expression (copies/μL) of (a), miR-34a-5p across different anatomical sites, where the thrombi were developed, including cerebral thrombosis (brain), pulmonary embolism (lung) and lower-limb thrombosis; and (b), miR-34a-5p under the combined influence of cerebral involvement and onset-type (provoked/unprovoked).

Figure 6.

The graphs present the expression (copies/μL) of (a), miR-34a-5p across different anatomical sites, where the thrombi were developed, including cerebral thrombosis (brain), pulmonary embolism (lung) and lower-limb thrombosis; and (b), miR-34a-5p under the combined influence of cerebral involvement and onset-type (provoked/unprovoked).

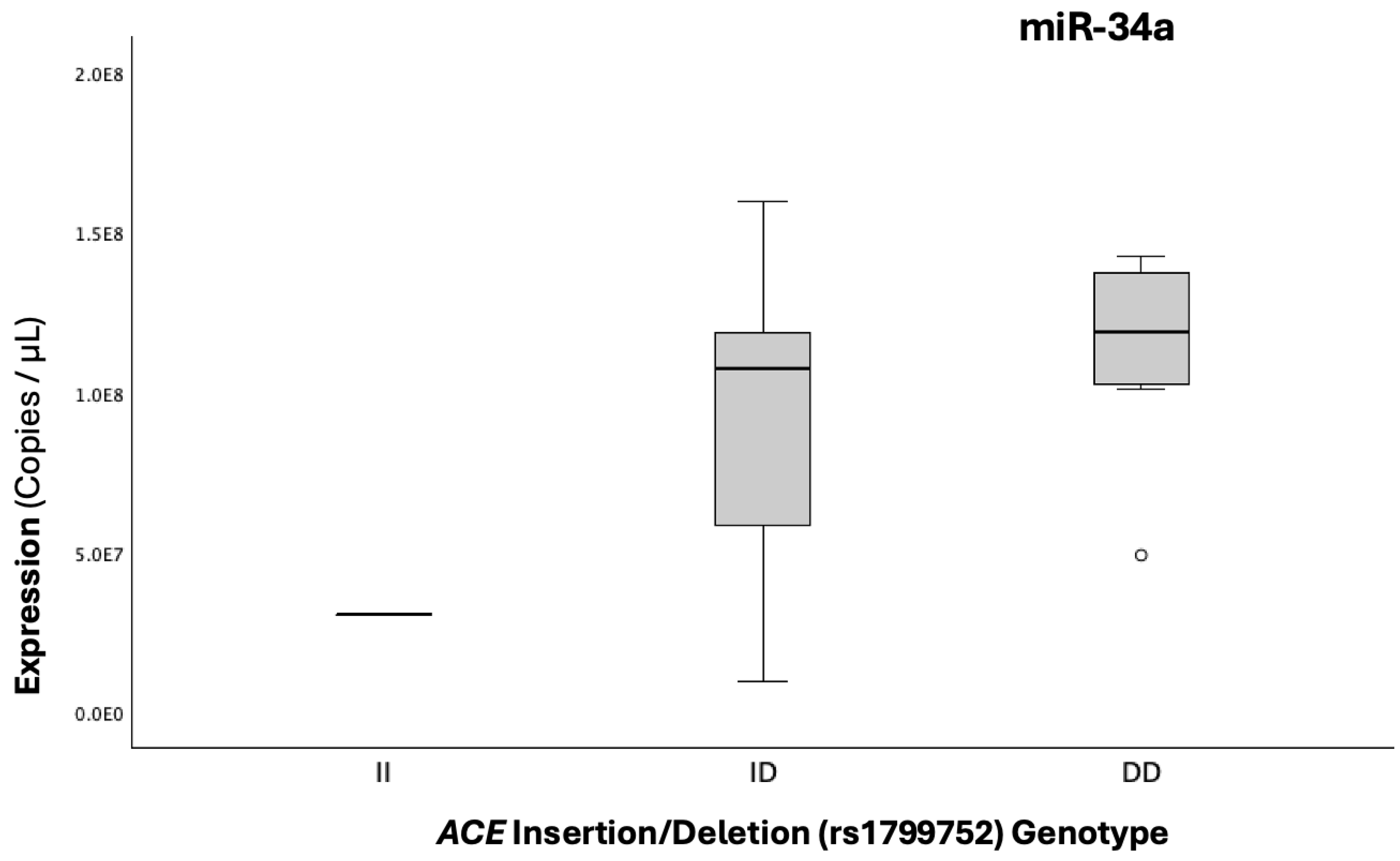

Figure 7.

Boxplots illustrating the expression (copies/μL) of miR-34a-5p across genotypic groups for the I/D functional polymorphism of the ACE gene, which increases the expression of ACE in light of the D allele, thus indirectly upstream increasing PAI-1 levels.

Figure 7.

Boxplots illustrating the expression (copies/μL) of miR-34a-5p across genotypic groups for the I/D functional polymorphism of the ACE gene, which increases the expression of ACE in light of the D allele, thus indirectly upstream increasing PAI-1 levels.

Figure 8.

The graph illustrates the epistatic modification, which was observed in cerebral cases, with double homozygosity (4G/4G+D/D), for the PAI-1-4G/5G and ACE-I/D gene functional polymorphisms, leading to miR-34a diminishing, while solely the 4G4G (in absence of DD carriership) exerts the reverse effect of significant miR-34a upregulation (p=0.006).

Figure 8.

The graph illustrates the epistatic modification, which was observed in cerebral cases, with double homozygosity (4G/4G+D/D), for the PAI-1-4G/5G and ACE-I/D gene functional polymorphisms, leading to miR-34a diminishing, while solely the 4G4G (in absence of DD carriership) exerts the reverse effect of significant miR-34a upregulation (p=0.006).

Table 1.

Characteristics and clinical data of the studied patient and control groups. Variables such as age and gender were statistically compared between the two groups by utilization of the appropriate statistical tests. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05. The studied groups did not differ significantly as to the variables of age and gender. 1 Mean (Range); a Mann-Whitney U test (2-sided), b Pearson Chi-Square (2-sided), c Independent Samples T-test.

Table 1.

Characteristics and clinical data of the studied patient and control groups. Variables such as age and gender were statistically compared between the two groups by utilization of the appropriate statistical tests. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05. The studied groups did not differ significantly as to the variables of age and gender. 1 Mean (Range); a Mann-Whitney U test (2-sided), b Pearson Chi-Square (2-sided), c Independent Samples T-test.

| Variable |

Patients (n=19) |

Controls (n=19) |

P-value |

|

Age (years) 1

|

9.51 (0.6-16) |

7.03 (0.6-15) |

0.124a

|

Gender

n (%) |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

0.163b

|

| 15 (78.9%) |

4

(21.1%) |

11 (57.9%) |

8

(42.1%) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Thrombosis Patients (n=19)

|

|

Type of Thrombosis (n,%) |

| Arterial (AT) |

Venous (VTE) |

| 1 (5.3%) |

18 (94.7%) |

|

Anatomical Site of Thrombosis (n,%) |

| Cerebral |

Lower Limbs |

Pulmonary |

| 9 (47.4%) |

6 (31.6%) |

4 (21.0%) |

|

Thrombotic Incident Classification (n,%) |

| Provoked |

Unprovoked |

| 6 (31.6%) |

13 (68.4%) |

| Months post-Thrombosis 1 |

| 7.63 (1-18) |

Time Groups

(months; n,%) |

1-3 |

3.1-6 |

6.1-12 |

12.1-18 |

| 4 (21.1%) |

5 (26.32%) |

7 (36.8%) |

3 (15.79%) |

| Treatment |

Yes (47.37%) |

No (52.63%) |

|

Family History of Thrombosis (n,%) |

P-value |

| |

Positive |

Negative |

|

| |

12 (63.2%) |

7 (36.8%) |

0.710c

|

| |

|

|

|

|

PAI-1(rs1799889) Genotype (n,%) |

| 5G5G |

4G5G |

4G4G |

| 3 (15.8%) |

12 (63.2%) |

4 (21.1%) |

|

ACE I/D (rs1799752) Genotype (n,%) |

| II |

ID |

DD |

| 1 (5.3%) |

11 (57.9%) |

7 (36.8%) |

Table 2.

Absolute expression of miR-145-5p and miR-34a-5p in the group of patients that underwent thrombotic incidents and in the group of healthy controls. The expression of the under-study miRNAs is presented in copies per mL of qRT-PCR reaction. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05*. The expression of miR-34a-5p exhibited statistically significant downregulation in the group of patients compared to controls (p=0.029, < 0.05), while the two groups did not significantly differ as to the expression of miR-145-5p (p=0.068, >0.05). 1 Mean (Range); a Mann-Whitney U test; b Independent-Samples T test.

Table 2.

Absolute expression of miR-145-5p and miR-34a-5p in the group of patients that underwent thrombotic incidents and in the group of healthy controls. The expression of the under-study miRNAs is presented in copies per mL of qRT-PCR reaction. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05*. The expression of miR-34a-5p exhibited statistically significant downregulation in the group of patients compared to controls (p=0.029, < 0.05), while the two groups did not significantly differ as to the expression of miR-145-5p (p=0.068, >0.05). 1 Mean (Range); a Mann-Whitney U test; b Independent-Samples T test.

Expression

(copies/μL) 1

|

Patients (n=19) |

Controls (n=19) |

P-value |

| miR-145-5p |

1.26 x 109

(1.72 x 108 − 7.12 x 109) |

1.63 x 109

(9.90 x 107 − 4.09 x 109) |

0.068 a

|

| miR-34a-5p |

9.66 x 107

(9.63 x 106 − 1.6 x 108) |

1.59 x 108

(3.59 x 107 − 3.80 x 108) |

0.029*b

|

Table 3.

Comparative overview of pairwise and omnibus comparisons of miRNA expression for single variables across distinctly defined groups, showing 1 mean expression (copies/μL), a fold changes (FC, log2FC), b expressional pattern (up- or down-regulation of miRNA in the first listed group), alongside p-values for significant differences. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05*.

Table 3.

Comparative overview of pairwise and omnibus comparisons of miRNA expression for single variables across distinctly defined groups, showing 1 mean expression (copies/μL), a fold changes (FC, log2FC), b expressional pattern (up- or down-regulation of miRNA in the first listed group), alongside p-values for significant differences. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05*.

| miRNA |

Expression1 (copies/μL)

|

FC a |

Log2FC |

Pattern b |

P-value |

| Groups |

Patients |

Controls |

|

|

|

|

| miR-145-5p |

1.26 x 109

|

1.63 x 109

|

0.77 |

-0.38 |

Down ↓ |

|

| miR-34a-5p |

9.66 x 107 |

1.59 x 108 |

0.61 |

-0.71 |

Down ↓

|

0.029*

|

| Within Thrombosis Patients |

Time-Groups

(post-Thrombosis) |

1-3

months |

3-6

months |

6-12

months |

|

12-18

months |

|

| miR-34a-5p |

1.27 x 108

|

1.1 x 108

|

7.0 x 107

|

|

9.7 x 107

|

|

| miRNA |

Expression 1 (copies/μL) |

FC |

Log2FC |

Pattern |

P-value |

Recent Treatment

Completion

|

yes |

no |

|

|

|

|

| miR-34a-5p |

7.0 x 107

|

1.2 x 108

|

0.62 |

-0.69 |

Down ↓ |

0.048* |

| PAI-1 4G carrier status |

4G/5G; 4G/4G |

5G/5G |

|

|

|

|

| miR-34a-5p |

1.0 x 108

|

7.8 x 107

|

1.29 |

0.37 |

Down ↓ |

|

| ACE D carrier status |

D/D |

I/D |

|

|

|

|

| miR-34a-5p |

1.1 x 108

|

9.2 x 107

|

1.22 |

0.29 |

Up ↑ |

|

| Type of incident |

Provoked |

Unprovoked |

|

|

|

|

| miR-34a-5p |

1.2 x 108

|

8.9 x 107

|

1.22 |

0.29 |

Up ↑ |

|

| Thrombosis site |

cerebral |

pulmonary |

Lower-limbs |

P-value |

| miR-34a-5p |

1.3 x 108

|

5.7 x 107

|

8.1 x 107

|

0.019* |

| |

cerebral |

non-cerebral |

|

|

| miR-34a-5p |

1.3 x 108

|

7.1 x 107 |

1.76 |

0.82 |

Up ↑ |

0.007*

|