Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Effect of Gender, Age and Menopausal Changes on the Urobiome

1.2. Bladder Cancer and Influence of Microbial Factors

2. Culturing and Molecular Techniques to Study the Urobiota

2.1. Culture-Dependent: Standard Urine Culture and Expanded Quantitative Urine Culture

2.2. Culturomics

2.3. Culture-Independent: Amplicon Sequencing and Metagenomics

2.4. Animal Models and 3D Organotypic In Vitro Model

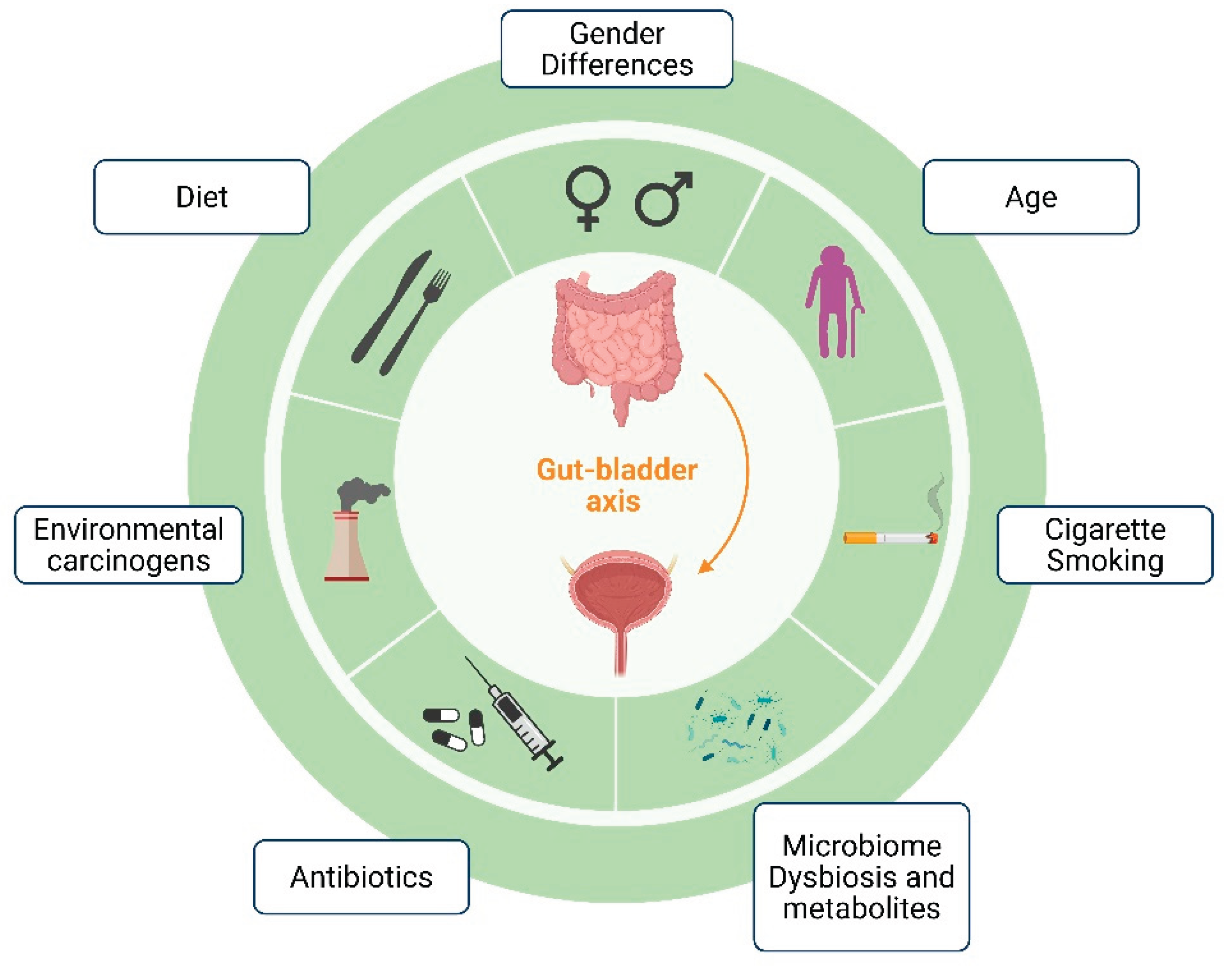

3. Gut-Bladder Axis in Bladder Cancer

4. Microbial-Derived Metabolites and Bladder Health

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| ABAP | Anaerobe 5% sheep blood agar |

| BAP | Sheep blood agar plate |

| BC | Bladder Cancer |

| BCG | Bacillus Calmette-Guérin |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EQUC | Expanded Quantitative Urine Culture |

| GM | Gut Microbiota |

| MALDI-TOF MS | Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight Mass |

| MIBC | Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| NMIBC | Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer |

| rUTIs | Recurrent urinary tract infections |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| SUC | Standard urine culture |

| UTIs | Urinary tract infections |

| UTUC | urinary tract urothelial carcinoma |

References

- Hilt, E.E.; McKinley, K.; Pearce, M.M.; Rosenfeld, A.B.; Zilliox, M.J.; Mueller, E.R.; Brubaker, L.; Gai, X.; Wolfe, A.J.; Schreckenberger, P.C. Urine is not sterile: use of enhanced urine culture techniques to detect resident bacterial flora in the adult female bladder. Journal of clinical microbiology 2014, 52, 871-876. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, M.M.; Hilt, E.E.; Rosenfeld, A.B.; Zilliox, M.J.; Thomas-White, K.; Fok, C.; Kliethermes, S.; Schreckenberger, P.C.; Brubaker, L.; Gai, X.; et al. The female urinary microbiome: a comparison of women with and without urgency urinary incontinence. mBio 2014, 5, e01283-01214. [CrossRef]

- Roth, R.S.; Liden, M.; Huttner, A. The urobiome in men and women: a clinical review. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2023, 29, 1242-1248. [CrossRef]

- Aad, G.; Abbott, B.; Abbott, D.C.; Abed Abud, A.; Abeling, K.; Abhayasinghe, D.K.; Abidi, S.H.; AbouZeid, O.S.; Abraham, N.L.; Abramowicz, H.; et al. Measurement of the Lund Jet Plane Using Charged Particles in 13 TeV Proton-Proton Collisions with the ATLAS Detector. Physical review letters 2020, 124, 222002. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.A.; Brown, R.; Williams, J.; White, P.; Jacobson, S.K.; Marchesi, J.R.; Drake, M.J. The human urinary microbiome; bacterial DNA in voided urine of asymptomatic adults. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2013, 3, 41. [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, L.; Wolfe, A.J. The new world of the urinary microbiota in women. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2015, 213, 644-649. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, H.; Nederbragt, A.J.; Lagesen, K.; Jeansson, S.L.; Jakobsen, K.S. Assessing diversity of the female urine microbiota by high throughput sequencing of 16S rDNA amplicons. BMC microbiology 2011, 11, 244. [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, A.L.; Chai, T.C. The Bladder is Not Sterile: an Update on the Urinary Microbiome. Current bladder dysfunction reports 2019, 14, 331-341. [CrossRef]

- Jones-Freeman, B.; Chonwerawong, M.; Marcelino, V.R.; Deshpande, A.V.; Forster, S.C.; Starkey, M.R. The microbiome and host mucosal interactions in urinary tract diseases. Mucosal immunology 2021, 14, 779-792. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lei, Y.; Du, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, D.; Gao, F.; Li, J. Exploring urinary microbiome: insights into neurogenic bladder and improving management of urinary tract infections. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2025, 15, 1512891. [CrossRef]

- Storm, D.W.; Copp, H.L.; Halverson, T.M.; Du, J.; Juhr, D.; Wolfe, A.J. A Child's urine is not sterile: A pilot study evaluating the Pediatric Urinary Microbiome. Journal of pediatric urology 2022, 18, 383-392. [CrossRef]

- Hadjifrangiskou, M.; Reasoner, S.; Flores, V.; Van Horn, G.; Morales, G.; Peard, L.; Abelson, B.; Manuel, C.; Lee, J.; Baker, B.; et al. Defining the Infant Male Urobiome and Moving Towards Mechanisms in Urobiome Research. Research square 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.S.; Dahl, E.M.; Jeries, L.M.; Sysoeva, T.A.; Karstens, L. Characterization of pediatric urinary microbiome at species-level resolution indicates variation due to sex, age, and urologic history. Journal of pediatric urology 2024, 20, 884-893. [CrossRef]

- Kinneman, L.; Zhu, W.; Wong, W.S.W.; Clemency, N.; Provenzano, M.; Vilboux, T.; Jane't, K.; Seo-Mayer, P.; Levorson, R.; Kou, M.; et al. Assessment of the Urinary Microbiome in Children Younger Than 48 Months. The Pediatric infectious disease journal 2020, 39, 565-570. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, R.C.; Manges, A.R.; Finlay, B.B.; Prendergast, A.J. The Human Microbiome and Child Growth - First 1000 Days and Beyond. Trends in microbiology 2019, 27, 131-147. [CrossRef]

- Komesu, Y.M.; Dinwiddie, D.L.; Richter, H.E.; Lukacz, E.S.; Sung, V.W.; Siddiqui, N.Y.; Zyczynski, H.M.; Ridgeway, B.; Rogers, R.G.; Arya, L.A.; et al. Defining the relationship between vaginal and urinary microbiomes. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2020, 222, 154 e151-154 e110. [CrossRef]

- Dubourg, G.; Morand, A.; Mekhalif, F.; Godefroy, R.; Corthier, A.; Yacouba, A.; Diakite, A.; Cornu, F.; Cresci, M.; Brahimi, S.; et al. Deciphering the Urinary Microbiota Repertoire by Culturomics Reveals Mostly Anaerobic Bacteria From the Gut. Frontiers in microbiology 2020, 11, 513305. [CrossRef]

- Jeries, L.M.; Sysoeva, T.A.; Karstens, L.; Kelly, M.S. Synthesis of current pediatric urinary microbiome research. Frontiers in pediatrics 2024, 12, 1396408. [CrossRef]

- Colella, M.; Topi, S.; Palmirotta, R.; D'Agostino, D.; Charitos, I.A.; Lovero, R.; Santacroce, L. An Overview of the Microbiota of the Human Urinary Tract in Health and Disease: Current Issues and Perspectives. Life 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Carrasco, V.; Soriano-Lerma, A.; Soriano, M.; Gutierrez-Fernandez, J.; Garcia-Salcedo, J.A. Urinary Microbiome: Yin and Yang of the Urinary Tract. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2021, 11, 617002. [CrossRef]

- Morsli, M.; Salipante, F.; Gelis, A.; Magnan, C.; Guigon, G.; Lavigne, J.P.; Sotto, A.; Dunyach-Remy, C. Evolution of the urinary microbiota in spinal cord injury patients with decubitus ulcer: A snapshot study. International wound journal 2024, 21, e14626. [CrossRef]

- Bajic, P.; Van Kuiken, M.E.; Burge, B.K.; Kirshenbaum, E.J.; Joyce, C.J.; Wolfe, A.J.; Branch, J.D.; Bresler, L.; Farooq, A.V. Male Bladder Microbiome Relates to Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. European urology focus 2020, 6, 376-382. [CrossRef]

- Burnett, L.A.; Hochstedler, B.R.; Weldon, K.; Wolfe, A.J.; Brubaker, L. Recurrent urinary tract infection: Association of clinical profiles with urobiome composition in women. Neurourology and urodynamics 2021, 40, 1479-1489. [CrossRef]

- Stone, L. Urine microbiota differ in bladder cancer. Nature reviews. Urology 2023, 20, 7. [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhong, J.; Zeng, J. Profiling the Urinary Microbiota in Male Patients With Bladder Cancer in China. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2018, 8, 167. [CrossRef]

- Curtiss, N.; Balachandran, A.; Krska, L.; Peppiatt-Wildman, C.; Wildman, S.; Duckett, J. Age, menopausal status and the bladder microbiome. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology 2018, 228, 126-129. [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, A.E. Urine Culture in Uncomplicated UTI: Interpretation and Significance. Current infectious disease reports 2016, 18, 15. [CrossRef]

- Saginala, K.; Barsouk, A.; Aluru, J.S.; Rawla, P.; Padala, S.A.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer. Medical sciences 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Woolbright, B.L.; Umar, S.; Ingersoll, M.A.; Taylor, J.A., 3rd. Bladder cancer, inflammageing and microbiomes. Nature reviews. Urology 2022, 19, 495-509. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.S.; Boorjian, S.A.; Chou, R.; Clark, P.E.; Daneshmand, S.; Konety, B.R.; Pruthi, R.; Quale, D.Z.; Ritch, C.R.; Seigne, J.D.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline. The Journal of urology 2016, 196, 1021-1029. [CrossRef]

- Lenis, A.T.; Lec, P.M.; Chamie, K.; Mshs, M.D. Bladder Cancer: A Review. Jama 2020, 324, 1980-1991. [CrossRef]

- Grabe-Heyne, K.; Henne, C.; Mariappan, P.; Geiges, G.; Pohlmann, J.; Pollock, R.F. Intermediate and high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: an overview of epidemiology, burden, and unmet needs. Frontiers in oncology 2023, 13, 1170124. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Gomez, J.; Solsona, E.; Unda, M.; Martinez-Pineiro, L.; Gonzalez, M.; Hernandez, R.; Madero, R.; Ojea, A.; Pertusa, C.; Rodriguez-Molina, J.; et al. Prognostic factors in patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer treated with bacillus Calmette-Guerin: multivariate analysis of data from four randomized CUETO trials. European urology 2008, 53, 992-1001. [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, M.A.; Li, X.; Inman, B.A.; Greiner, J.W.; Black, P.C.; Adam, R.M. Immunology, Immunotherapy, and Translating Basic Science into the Clinic for Bladder Cancer. Bladder cancer 2018, 4, 429-440. [CrossRef]

- Koti, M.; Ingersoll, M.A.; Gupta, S.; Lam, C.M.; Li, X.; Kamat, A.M.; Black, P.C.; Siemens, D.R. Sex Differences in Bladder Cancer Immunobiology and Outcomes: A Collaborative Review with Implications for Treatment. European urology oncology 2020, 3, 622-630. [CrossRef]

- Burger, M.; Catto, J.W.; Dalbagni, G.; Grossman, H.B.; Herr, H.; Karakiewicz, P.; Kassouf, W.; Kiemeney, L.A.; La Vecchia, C.; Shariat, S.; et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of urothelial bladder cancer. European urology 2013, 63, 234-241. [CrossRef]

- Babjuk, M. Re: Oncological Benefit of Re-resection for T1 Bladder Cancer: A Comparative Effectiveness Study. European urology 2023, 83, 297. [CrossRef]

- Lammers, R.J.; Witjes, W.P.; Hendricksen, K.; Caris, C.T.; Janzing-Pastors, M.H.; Witjes, J.A. Smoking status is a risk factor for recurrence after transurethral resection of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. European urology 2011, 60, 713-720. [CrossRef]

- Kiriluk, K.J.; Prasad, S.M.; Patel, A.R.; Steinberg, G.D.; Smith, N.D. Bladder cancer risk from occupational and environmental exposures. Urologic oncology 2012, 30, 199-211. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.H.; Sheweita, S.A.; O'Connor, P.J. Relationship between schistosomiasis and bladder cancer. Clinical microbiology reviews 1999, 12, 97-111. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xia, H.; Tan, X.; Shi, C.; Ma, Y.; Meng, D.; Zhou, M.; Lv, Z.; Wang, S.; Jin, Y. Intratumoural microbiota: a new frontier in cancer development and therapy. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2024, 9, 15. [CrossRef]

- Vogtmann, E.; Goedert, J.J. Epidemiologic studies of the human microbiome and cancer. British journal of cancer 2016, 114, 237-242. [CrossRef]

- Rajagopala, S.V.; Vashee, S.; Oldfield, L.M.; Suzuki, Y.; Venter, J.C.; Telenti, A.; Nelson, K.E. The Human Microbiome and Cancer. Cancer prevention research 2017, 10, 226-234. [CrossRef]

- Aragon-Ching, J.B.; Werntz, R.P.; Zietman, A.L.; Steinberg, G.D. Multidisciplinary Management of Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: Current Challenges and Future Directions. American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Annual Meeting 2018, 38, 307-318. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Zhang, G.; Chen, C.; Li, K.; Wen, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wu, P. Alterations in Urobiome in Patients With Bladder Cancer and Implications for Clinical Outcome: A Single-Institution Study. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2020, 10, 555508. [CrossRef]

- Yacouba, A.; Tidjani Alou, M.; Lagier, J.C.; Dubourg, G.; Raoult, D. Urinary microbiota and bladder cancer: A systematic review and a focus on uropathogens. Seminars in cancer biology 2022, 86, 875-884. [CrossRef]

- Chipollini, J.; Wright, J.R.; Nwanosike, H.; Kepler, C.Y.; Batai, K.; Lee, B.R.; Spiess, P.E.; Stewart, D.B.; Lamendella, R. Characterization of urinary microbiome in patients with bladder cancer: Results from a single-institution, feasibility study. Urologic oncology 2020, 38, 615-621. [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.; Tian, Y.; Song, C.; Li, J.; Liu, T.; Chen, Z.; Chen, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Urinary microbiota - a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for bladder cancer. Journal of medical microbiology 2019, 68, 1471-1478. [CrossRef]

- Bucevic Popovic, V.; Situm, M.; Chow, C.T.; Chan, L.S.; Roje, B.; Terzic, J. The urinary microbiome associated with bladder cancer. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 12157. [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, V.; Choi, H.W. The Urinary Microbiome: Role in Bladder Cancer and Treatment. Diagnostics 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Oresta, B.; Braga, D.; Lazzeri, M.; Frego, N.; Saita, A.; Faccani, C.; Fasulo, V.; Colombo, P.; Guazzoni, G.; Hurle, R.; et al. The Microbiome of Catheter Collected Urine in Males with Bladder Cancer According to Disease Stage. The Journal of urology 2021, 205, 86-93. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Yang, L.; Lee, P.; Huang, W.C.; Nossa, C.; Ma, Y.; Deng, F.M.; Zhou, M.; Melamed, J.; Pei, Z. Mini-review: perspective of the microbiome in the pathogenesis of urothelial carcinoma. American journal of clinical and experimental urology 2014, 2, 57-61.

- Mai, G.; Chen, L.; Li, R.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Y. Common Core Bacterial Biomarkers of Bladder Cancer Based on Multiple Datasets. BioMed research international 2019, 2019, 4824909. [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, M.; Sullivan, T.; Provenzano, K.; Rieger-Christ, K. Urinary Microbiome Evaluation in Patients Presenting with Hematuria with a Focus on Exposure to Tobacco Smoke. Research and reports in urology 2019, 11, 359-367. [CrossRef]

- Mansour, B.; Monyok, A.; Makra, N.; Gajdacs, M.; Vadnay, I.; Ligeti, B.; Juhasz, J.; Szabo, D.; Ostorhazi, E. Bladder cancer-related microbiota: examining differences in urine and tissue samples. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 11042. [CrossRef]

- Pederzoli, F.; Ferrarese, R.; Amato, V.; Locatelli, I.; Alchera, E.; Luciano, R.; Nebuloni, M.; Briganti, A.; Gallina, A.; Colombo, R.; et al. Sex-specific Alterations in the Urinary and Tissue Microbiome in Therapy-naive Urothelial Bladder Cancer Patients. European urology oncology 2020, 3, 784-788. [CrossRef]

- Hourigan, S.K.; Zhu, W.; W, S.W.W.; Clemency, N.C.; Provenzano, M.; Vilboux, T.; Niederhuber, J.E.; Deeken, J.; Chung, S.; McDaniel-Wiley, K.; et al. Studying the urine microbiome in superficial bladder cancer: samples obtained by midstream voiding versus cystoscopy. BMC urology 2020, 20, 5. [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.A.; Elsayed, A.S.; Durrani, M.; Jing, Z.; Iqbal, U.; Gomez, E.C.; Singh, P.K.; Liu, S.; Smith, G.; Tang, L.; et al. Investigating the association between the urinary microbiome and bladder cancer: An exploratory study. Urologic oncology 2021, 39, 370 e379-370 e319. [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhang, W.; Shen, L.; Liu, J.; Yang, F.; Maskey, N.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Y.; Yao, X. Can Smoking Cause Differences in Urine Microbiome in Male Patients With Bladder Cancer? A Retrospective Study. Frontiers in oncology 2021, 11, 677605. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Liu, J.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, S. Analysis of Urinary Flora Characteristics in Urinary Tumor Based on 16S rRNA Sequence. BioMed research international 2022, 2022, 9368687. [CrossRef]

- Chorbinska, J.; Krajewski, W.; Nowak, L.; Bardowska, K.; Zebrowska-Rozanska, P.; Laczmanski, L.; Pacyga-Prus, K.; Gorska, S.; Malkiewicz, B.; Szydelko, T. Is the Urinary and Gut Microbiome Associated With Bladder Cancer? Clinical Medicine Insights. Oncology 2023, 17, 11795549231206796. [CrossRef]

- Poore, G.D.; Kopylova, E.; Zhu, Q.; Carpenter, C.; Fraraccio, S.; Wandro, S.; Kosciolek, T.; Janssen, S.; Metcalf, J.; Song, S.J.; et al. Microbiome analyses of blood and tissues suggest cancer diagnostic approach. Nature 2020, 579, 567-574. [CrossRef]

- Bersanelli, M.; Santoni, M.; Ticinesi, A.; Buti, S. The Urinary Microbiome and Anticancer Immunotherapy: The Potentially Hidden Role of Unculturable Microbes. Targeted oncology 2019, 14, 247-252. [CrossRef]

- Sepich-Poore, G.D.; Carter, H.; Knight, R. Intratumoral bacteria generate a new class of therapeutically relevant tumor antigens in melanoma. Cancer cell 2021, 39, 601-603. [CrossRef]

- Grasso, F.; Frisan, T. Bacterial Genotoxins: Merging the DNA Damage Response into Infection Biology. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 1762-1782. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, L.; Yang, Q.; Li, F.; Shi, Z.; Feng, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Jin, X.; Zhu, S.; et al. Identification and Evaluation of the Urinary Microbiota Associated With Bladder Cancer. Cancer innovation 2025, 4, e70012. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shangguan, W.; Huang, W.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xie, M.; Yu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zheng, J.; Yang, L.; et al. Gut Parabacteroides distasonis-derived Indole-3-Acetic Acid Promotes Phospholipid Remodeling and Enhances Ferroptosis Sensitivity via the AhR-FASN Axis in Bladder Cancer. Advanced science 2025, e04688. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zou, W.; Liu, Z. Causal relationships between gut microbiota and urothelial carcinoma mediated by inflammatory cytokines and blood cell traits identified through Mendelian randomization analysis. Discover oncology 2025, 16, 1440. [CrossRef]

- Alfano, M.; Canducci, F.; Nebuloni, M.; Clementi, M.; Montorsi, F.; Salonia, A. The interplay of extracellular matrix and microbiome in urothelial bladder cancer. Nature reviews. Urology 2016, 13, 77-90. [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, P.; Walev, I.; Rose-John, S.; Bhakdi, S. Novel pathogenic mechanism of microbial metalloproteinases: liberation of membrane-anchored molecules in biologically active form exemplified by studies with the human interleukin-6 receptor. Infection and immunity 1996, 64, 3646-3651. [CrossRef]

- Horvat, R.T.; Parmely, M.J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa alkaline protease degrades human gamma interferon and inhibits its bioactivity. Infection and immunity 1988, 56, 2925-2932. [CrossRef]

- Min, K.; Kim, H.T.; Lee, E.H.; Park, H.; Ha, Y.S. Bacteria for Treatment: Microbiome in Bladder Cancer. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Redelman-Sidi, G. BCG in Bladder Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, C.; Siddiqui, N.Y.; Fields, I.; Gregory, W.T.; Simon, H.M.; Mooney, M.A.; Wolfe, A.J.; Karstens, L. Species-Level Resolution of Female Bladder Microbiota from 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing. mSystems 2021, 6, e0051821. [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.E.; Chopyk, J.; Shin, J.H.; Lukacz, E.S.; Brubaker, L.; Schwanemann, L.K.; Knight, R.; Wolfe, A.J.; Pride, D.T. Benchmarking urine storage and collection conditions for evaluating the female urinary microbiome. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 13409. [CrossRef]

- Bundgaard-Nielsen, C.; Ammitzboll, N.; Isse, Y.A.; Muqtar, A.; Jensen, A.M.; Leutscher, P.D.C.; Arenholt, L.T.S.; Hagstrom, S.; Sorensen, S. Voided Urinary Microbiota Is Stable Over Time but Impacted by Post Void Storage. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2020, 10, 435. [CrossRef]

- Aragon, I.M.; Herrera-Imbroda, B.; Queipo-Ortuno, M.I.; Castillo, E.; Del Moral, J.S.; Gomez-Millan, J.; Yucel, G.; Lara, M.F. The Urinary Tract Microbiome in Health and Disease. European urology focus 2018, 4, 128-138. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, A.J.; Toh, E.; Shibata, N.; Rong, R.; Kenton, K.; Fitzgerald, M.; Mueller, E.R.; Schreckenberger, P.; Dong, Q.; Nelson, D.E.; et al. Evidence of uncultivated bacteria in the adult female bladder. Journal of clinical microbiology 2012, 50, 1376-1383. [CrossRef]

- Ng, H.H.; Ang, H.C.; Hoe, S.Y.; Lim, M.L.; Tai, H.E.; Soh, R.C.H.; Syn, C.K. Simple DNA extraction of urine samples: Effects of storage temperature and storage time. Forensic science international 2018, 287, 36-39. [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Chung, H. The Urobiome and Its Role in Overactive Bladder. International neurourology journal 2022, 26, 190-200. [CrossRef]

- Gaitonde, S.; Malik, R.D.; Zimmern, P.E. Financial Burden of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Women: A Time-driven Activity-based Cost Analysis. Urology 2019, 128, 47-54. [CrossRef]

- Kass, E.H. Bacteriuria and the diagnosis of infections of the urinary tract; with observations on the use of methionine as a urinary antiseptic. A.M.A. archives of internal medicine 1957, 100, 709-714. [CrossRef]

- Thomas-White, K.; Forster, S.C.; Kumar, N.; Van Kuiken, M.; Putonti, C.; Stares, M.D.; Hilt, E.E.; Price, T.K.; Wolfe, A.J.; Lawley, T.D. Culturing of female bladder bacteria reveals an interconnected urogenital microbiota. Nature communications 2018, 9, 1557. [CrossRef]

- Price, T.K.; Dune, T.; Hilt, E.E.; Thomas-White, K.J.; Kliethermes, S.; Brincat, C.; Brubaker, L.; Wolfe, A.J.; Mueller, E.R.; Schreckenberger, P.C. The Clinical Urine Culture: Enhanced Techniques Improve Detection of Clinically Relevant Microorganisms. Journal of clinical microbiology 2016, 54, 1216-1222. [CrossRef]

- Price, T.K.; Wolff, B.; Halverson, T.; Limeira, R.; Brubaker, L.; Dong, Q.; Mueller, E.R.; Wolfe, A.J. Temporal Dynamics of the Adult Female Lower Urinary Tract Microbiota. mBio 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Hurst, R.; Meader, E.; Gihawi, A.; Rallapalli, G.; Clark, J.; Kay, G.L.; Webb, M.; Manley, K.; Curley, H.; Walker, H.; et al. Microbiomes of Urine and the Prostate Are Linked to Human Prostate Cancer Risk Groups. European urology oncology 2022, 5, 412-419. [CrossRef]

- Lagier, J.C.; Hugon, P.; Khelaifia, S.; Fournier, P.E.; La Scola, B.; Raoult, D. The rebirth of culture in microbiology through the example of culturomics to study human gut microbiota. Clinical microbiology reviews 2015, 28, 237-264. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Kim, J.; Hatzenpichler, R.; Karymov, M.A.; Hubert, N.; Hanan, I.M.; Chang, E.B.; Ismagilov, R.F. Gene-targeted microfluidic cultivation validated by isolation of a gut bacterium listed in Human Microbiome Project's Most Wanted taxa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014, 111, 9768-9773. [CrossRef]

- Lagier, J.C.; Dubourg, G.; Million, M.; Cadoret, F.; Bilen, M.; Fenollar, F.; Levasseur, A.; Rolain, J.M.; Fournier, P.E.; Raoult, D. Culturing the human microbiota and culturomics. Nature reviews. Microbiology 2018, 16, 540-550. [CrossRef]

- Ugarcina Perovic, S.; Ksiezarek, M.; Rocha, J.; Cappelli, E.A.; Sousa, M.; Ribeiro, T.G.; Grosso, F.; Peixe, L. Urinary Microbiome of Reproductive-Age Asymptomatic European Women. Microbiology spectrum 2022, 10, e0130822. [CrossRef]

- Baddoo, G.; Ene, A.; Merchant, Z.; Banerjee, S.; Wolfe, A.J.; Putonti, C. Cataloging variation in 16S rRNA gene sequences of female urobiome bacteria. Frontiers in urology 2023, 3, 1270509. [CrossRef]

- Heytens, S.; De Sutter, A.; Coorevits, L.; Cools, P.; Boelens, J.; Van Simaey, L.; Christiaens, T.; Vaneechoutte, M.; Claeys, G. Women with symptoms of a urinary tract infection but a negative urine culture: PCR-based quantification of Escherichia coli suggests infection in most cases. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2017, 23, 647-652. [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, J.K.; Di Rienzi, S.C.; Poole, A.C.; Koren, O.; Walters, W.A.; Caporaso, J.G.; Knight, R.; Ley, R.E. Conducting a microbiome study. Cell 2014, 158, 250-262. [CrossRef]

- Deurenberg, R.H.; Bathoorn, E.; Chlebowicz, M.A.; Couto, N.; Ferdous, M.; Garcia-Cobos, S.; Kooistra-Smid, A.M.; Raangs, E.C.; Rosema, S.; Veloo, A.C.; et al. Application of next generation sequencing in clinical microbiology and infection prevention. Journal of biotechnology 2017, 243, 16-24. [CrossRef]

- Barraud, O.; Ravry, C.; Francois, B.; Daix, T.; Ploy, M.C.; Vignon, P. Shotgun metagenomics for microbiome and resistome detection in septic patients with urinary tract infection. International journal of antimicrobial agents 2019, 54, 803-808. [CrossRef]

- Hasman, H.; Saputra, D.; Sicheritz-Ponten, T.; Lund, O.; Svendsen, C.A.; Frimodt-Moller, N.; Aarestrup, F.M. Rapid whole-genome sequencing for detection and characterization of microorganisms directly from clinical samples. Journal of clinical microbiology 2014, 52, 139-146. [CrossRef]

- Mulder, H.A.; Lee, S.H.; Clark, S.; Hayes, B.J.; van der Werf, J.H.J. The Impact of Genomic and Traditional Selection on the Contribution of Mutational Variance to Long-Term Selection Response and Genetic Variance. Genetics 2019, 213, 361-378. [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, A.; Li, W.; Singh, H.; Moncera, K.J.; Torralba, M.G.; Yu, Y.; Manuel, O.; Biggs, W.; Venter, J.C.; Nelson, K.E.; et al. Microbial metagenome of urinary tract infection. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 4333. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.L.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Liston, A.; Raes, J. How informative is the mouse for human gut microbiota research? Disease models & mechanisms 2015, 8, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Fantini, D.; Glaser, A.P.; Rimar, K.J.; Wang, Y.; Schipma, M.; Varghese, N.; Rademaker, A.; Behdad, A.; Yellapa, A.; Yu, Y.; et al. A Carcinogen-induced mouse model recapitulates the molecular alterations of human muscle invasive bladder cancer. Oncogene 2018, 37, 1911-1925. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Kawashima, A.; Uemura, T.; Nakano, K.; Matsushita, M.; Ishizuya, Y.; Jingushi, K.; Hase, H.; Katayama, K.; Yamaguchi, R.; et al. A novel mouse model of upper tract urothelial carcinoma highlights the impact of dietary intervention on gut microbiota and carcinogenesis prevention despite carcinogen exposure. International journal of cancer 2025, 156, 1439-1456. [CrossRef]

- Kim, R. Advanced Organotypic In Vitro Model Systems for Host-Microbial Coculture. Biochip journal 2023, 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Shin, K. Stem cells, organoids and their applications for human diseases: Special issue of BMB Reports in 2023. BMB reports 2023, 56, 1. [CrossRef]

- Charles, C.A.; Ricotti, C.A.; Davis, S.C.; Mertz, P.M.; Kirsner, R.S. Use of tissue-engineered skin to study in vitro biofilm development. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.] 2009, 35, 1334-1341. [CrossRef]

- Taebnia, N.; Romling, U.; Lauschke, V.M. In vitro and ex vivo modeling of enteric bacterial infections. Gut microbes 2023, 15, 2158034. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, D.; Feng, N. Harnessing organoid technology in urological cancer: advances and applications in urinary system tumors. World journal of surgical oncology 2025, 23, 295. [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.; Kim, J.; Yi, H.G.; Cho, D.W. 3D Bioprinting of an In Vitro Model of a Biomimetic Urinary Bladder with a Contract-Release System. Micromachines 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Fu, Q.; Yoo, J.; Chen, X.; Chandra, P.; Mo, X.; Song, L.; Atala, A.; Zhao, W. 3D bioprinting of urethra with PCL/PLCL blend and dual autologous cells in fibrin hydrogel: An in vitro evaluation of biomimetic mechanical property and cell growth environment. Acta biomaterialia 2017, 50, 154-164. [CrossRef]

- Mingdong, W.; Xiang, G.; Yongjun, Q.; Mingshuai, W.; Hao, P. Causal associations between gut microbiota and urological tumors: a two-sample mendelian randomization study. BMC cancer 2023, 23, 854. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Jin, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, K.; Yin, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, G.; Yan, X.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Causal relationship between bladder cancer and gut microbiota contributes to the gut-bladder axis: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Urologic oncology 2025, 43, 267 e269-267 e218. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, L.; He, Y.; Luo, H.; Fang, C. Causal effect of gut microbiota on the risk of cancer and potential mediation by inflammatory proteins. World journal of surgical oncology 2025, 23, 163. [CrossRef]

- Bukavina, L.; Ginwala, R.; Eltoukhi, M.; Sindhani, M.; Prunty, M.; Geynisman, D.M.; Ghatalia, P.; Valentine, H.; Calaway, A.; Correa, A.F.; et al. Role of Gut Microbiome in Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in Urothelial Carcinoma: A Multi-institutional Prospective Cohort Evaluation. Cancer research communications 2024, 4, 1505-1516. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Qiu, Y.; Xie, M.; Huang, P.; Yu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Shangguan, W.; Li, W.; Zhu, Z.; Xue, J.; et al. Gut microbiota Parabacteroides distasonis enchances the efficacy of immunotherapy for bladder cancer by activating anti-tumor immune responses. BMC microbiology 2024, 24, 237. [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Xu, B.; Luo, P.; Chen, T.; Duan, H. Non-coding RNAs in bladder cancer, a bridge between gut microbiota and host? Frontiers in immunology 2024, 15, 1482765. [CrossRef]

- Mann, E.R.; Lam, Y.K.; Uhlig, H.H. Short-chain fatty acids: linking diet, the microbiome and immunity. Nature reviews. Immunology 2024, 24, 577-595. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.M. Microbial molecules, metabolites, and malignancy. Neoplasia 2025, 60, 101128. [CrossRef]

- Tsvetikova, S.A.; Koshel, E.I. Microbiota and cancer: host cellular mechanisms activated by gut microbial metabolites. International journal of medical microbiology : IJMM 2020, 310, 151425. [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Li, B.; Huang, L.; Teng, C.; Bao, Y.; Ren, M.; Shan, Y. Gut microbial composition changes in bladder cancer patients: A case-control study in Harbin, China. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition 2020, 29, 395-403. [CrossRef]

- Then, C.K.; Paillas, S.; Moomin, A.; Misheva, M.D.; Moir, R.A.; Hay, S.M.; Bremner, D.; Roberts Nee Nellany, K.S.; Smith, E.E.; Heidari, Z.; et al. Dietary fibre supplementation enhances radiotherapy tumour control and alleviates intestinal radiation toxicity. Microbiome 2024, 12, 89. [CrossRef]

- Then, C.K.; Paillas, S.; Wang, X.; Hampson, A.; Kiltie, A.E. Association of Bacteroides acidifaciens relative abundance with high-fibre diet-associated radiosensitisation. BMC biology 2020, 18, 102. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Kosinska, W.; Zhao, Z.L.; Wu, X.R.; Guttenplan, J.B. Tissue-specific mutagenesis by N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)nitrosamine as the basis for urothelial carcinogenesis. Mutation research 2012, 742, 92-95. [CrossRef]

- Roje, B.; Zhang, B.; Mastrorilli, E.; Kovacic, A.; Susak, L.; Ljubenkov, I.; Cosic, E.; Vilovic, K.; Mestrovic, A.; Vukovac, E.L.; et al. Gut microbiota carcinogen metabolism causes distal tissue tumours. Nature 2024, 632, 1137-1144. [CrossRef]

- Lienert, J.; Burki, T.; Escher, B.I. Reducing micropollutants with source control: substance flow analysis of 212 pharmaceuticals in faeces and urine. Water science and technology : a journal of the International Association on Water Pollution Research 2007, 56, 87-96. [CrossRef]

- Marti, T.D.; Scharer, M.R.; Robinson, S.L. Microbial Biocatalysis within Us: The Underexplored Xenobiotic Biotransformation Potential of the Urinary Tract Microbiota. Chimia 2023, 77, 424-431. [CrossRef]

| Study | Sample size (Cancer/Healthy) |

Cohorts and Diversity | Abundance and key findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xu et al. [52] | 8/6 |

|

|

| Bucevic Popovic et al. [49] | 12/11 |

|

|

| Wu et al. [25] | 31/18 |

|

|

| Bi et al. [48] | 29/26 |

|

|

| Mai et al. [53] | 24/0 |

|

|

| Moynihan et al. [54] | 35/8 |

|

|

| Mansour et al. [55] | 10/0 |

|

|

| Pederzoli et al. [56] | 49/59 |

|

|

| Zeng et al. [45] | 62/19 |

|

|

| Chipollini et al. [47] | 38/10 |

|

|

| Hourigan et al. [57] | 22/0 |

|

|

| Hussein et al. [58] | 43/10 |

|

|

| Ma et al. [59] | 15/11 |

|

|

| Oresta et al. [51] | 51/10 |

|

|

| Qiu et al. [60] | 6/4 |

|

|

| Chorbinska et al. [61] | 18/7 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).