1. Introduction

Blockchain is a distributed digital ledger technology that allows data to be stored across multiple computers. It ensures that data is secure, transparent, and difficult to alter. Each block contains a set of data and is cryptographically linked to the previous block to form a chain (Soltani et al., 2022).

1.1. Study Background

Blockchain has demonstrated significant utility across diverse areas, such as finance and banking, supply chain and logistics, healthcare, etc. This breakthrough technology is a transformative step in storing, sharing, and verifying digital information. Blockchain breaks the traditional centralised systems by having unique components, concepts, and mechanisms (Chen et al., 2025).

1.1.1. Key Components and How Blockchain Works

The core components of blockchain technology include the distributed ledger, block, cryptographic hash, consensus mechanism, and smart contract. The distributed ledger is the finalized record added to a block, shared across all nodes instead of being stored centrally (An et al., 2023). A block contains valid data such as transactions, a timestamp, its hash value, and the previous block’s hash (Ahmed, 2025; Hussain et al., 2024). Cryptographic hashing secures the block’s content by converting transaction data into a fixed-size string, with each block referencing the previous one with its hash (Feng et al., 2024; Hanif et al., 2022). The consensus mechanism allows nodes to agree on the blockchain’s state with common types including Proof of Work(PoW) and Proof of Stake(PoS) (B. Lashkari & P. Musilek, 2021). A smart contract is a self-executing blockchain program that runs automatically when predefined conditions are met.

The general transaction flow in a blockchain involves a few processes. It begins when a user initiates a transaction using their private key. The transaction will be broadcast to the network of nodes and temporarily stored in a holding area called Mempool (Tong et al., 2025). All nodes that received the transaction will perform a basic validation to ensure the transaction adheres to the platform’s conditions (Xiao et al., 2020; Jun et al., 2024).

Next, the miner selects transactions on their Mempool and packages the data into a candidate block. They usually prioritize the transactions with higher commission fees. The miner will attempt to add the block to the blockchain based on the network’s consensus mechanism(Das, S. R., 2023). When the consensus is achieved, the new block will be added to the existing chain of blocks, and the block creator will be rewarded. Finally, all nodes verify the new block and add it to their copy blockchain, hence allowing transaction data to become visible and immutable to all nodes (Tripathi et al., 2023; Humayun et al., 2022).

1.1.2. Cyber Attacks on Blockchain

Smart contract exploits and phishing attacks are two of the most prevalent attacks on the blockchain, but they operate in very different ways. Smart contract exploits can be code vulnerabilities or logic flaws. These represent technical errors while logic flaws represent logical errors in the smart contract code itself (Praitheeshan et al., 2020; Jabeen et al., 2023).

There are various ways to perform phishing, including fake websites and malicious browser extensions. The attacker creates an interface that is extremely similar to the original website and steals the user's login credentials and private keys. The phishing website can also prompt users to install extensions to modify user transaction addresses (Ogundokun et al., 2023; Kiyani et al., 2024). Both attacks can cause serious financial losses, but while smart contract exploits can lead to market volatility, phishing attacks only cause reputational damage to individuals or platforms (Carpentier-Desjardins et al., 2025).

1.2. Problem Identification

NIST defines social engineering as deceiving individuals into revealing their sensitive information, such as passwords or credentials (Grassi et al., 2017). In comparison to the other cybersecurity attacks, social engineering underscores the manipulation of human psychology to breach security protocols, rather than exploiting technical vulnerabilities. Human factors remain a critical weakpoint in computer systems as many human factors come into play, such as trust, fear and lack of awareness (Wang et al., 2021; Krishnan et al., 2021). Hence, it is important to recognize the human factors when developing comprehensive security strategies to combat social engineering. According to Verizon, it has been reported that about 23% of data breaches involving humans were due to acts of social engineering, that is, approximately 2500 cases (2025 Data Breach Investigations Report, 2025). A myriad of social engineering tactics are used, including baiting, pretexting, and scareware. A real-world example of this will be the 2022 Ronin Network hack. Attackers used social engineering to convince a Sky Mavis engineer to download a malicious job offer document. This led to access being granted to validator nodes, resulting in over $600 million in stolen assets. Such attacks highlight how manipulation of human trust can bypass security imposed (Tidy, 2022; Khan et al., 2021).

1.2.1. Limitations of Existing Systems

Despite advances in cybersecurity tools, current systems remain ineffective in preventing social engineering attacks due to their reliance on reactive mechanisms and inability to adapt to evolving psychological manipulation techniques. The section below will be discussing about the limitations of existing systems in the context of social engineering.

Reactive Approach

A primary limitation of current security tools is that their approach to malware and virus, the majority often takes a reactive approach. For instance, most solutions in the market are built upon the use of a blacklist and whitelist. In which, they block access to domains or smart contracts that are already known to be malicious. However, this model is inherently insufficient for combating modern social engineering campaigns as most of it is based on newly created or invented malicious content. This poses a issue as it is found that that phishing URLs are often short lived, with some only lasting for a few hours (Bell & Komisarczuk, 2020; Muzafar & Jhanjhi, 2019).

Biasnesses and False Positives

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into cybersecurity, particularly for detecting social engineering attacks, is often presented as a definitive solution. One of the main reasons of algorithms bias is due to the quality of data. The effectiveness of any AI model is reliant on the quality and representativeness of its training data. Other than that, the lack of diversity in training data would also cause bias to appear in AI models. For example, an AI model trained to detect phishing attacks with data from Malaysia may fail to identify culturally specific social engineering campaigns of another country. This could lead to both false negatives and false positives, which reduces the reliability of the system (Basit et al., 2021; Muzammal et al., 2020).

2. Case Study Analysis

In this chapter, an in-depth analysis will be conducted on two real-world case studies that happened recently, namely the ByBit Hack and the Poly Network Attack.

2.1. Bybit Hack

On the 21st of February 2025, Bybit experienced a security breach that caused a cryptocurrency theft. This attack, known as the 2025 Bybit Hack, is the largest heist to date, with a loss of approximately $1.40 billion. At that time, this amount was equivalent to 401,347 Ethereum. ByBit, founded by Ben Zhou in the year of 2018, has over 60 million users currently. Bybit is amongst the world’s top 5 cryptocurrency exchanges.. This attack was first suspected to be due to a compromise of a ByBit employee device, however, further investigation reported that it was due to compromising a Safe{Wallet} developer machine. (Rivas et al., 2025; Linqiang et al., 2024). Safe{Wallet} is a third-party multisignature wallet platform that provides a more secure transaction signing infrastructure. ByBit utilizes Safe{Wallet}’s services to manage and authorize transactions from its Ethereum cold wallet. (Schor, 2023; Saeed et al., 2022)

2.1.1. Chronology

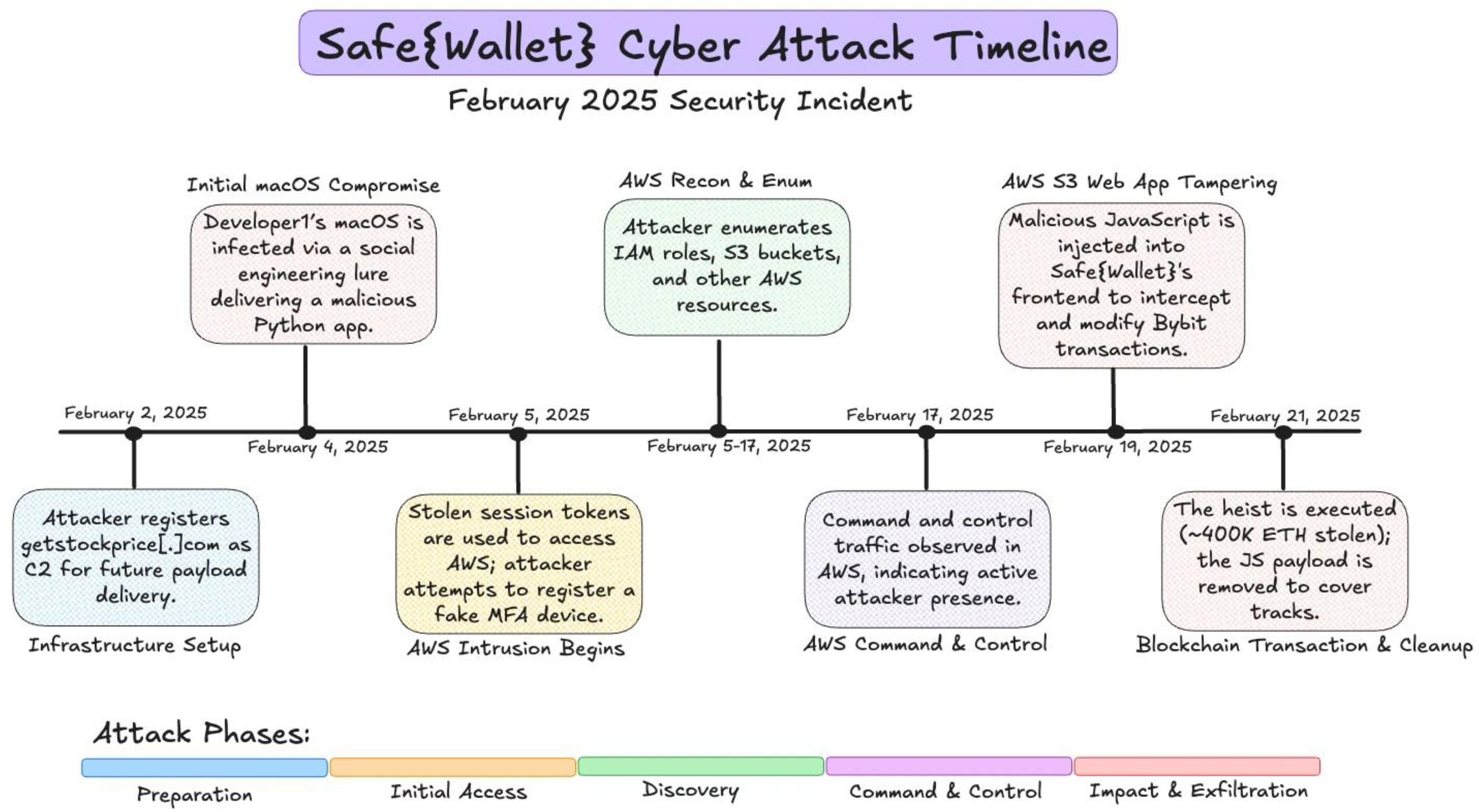

Figure 2.1.1.

Timeline of ByBit Hack (Wilhoit & Dejesus, 2025).

Figure 2.1.1.

Timeline of ByBit Hack (Wilhoit & Dejesus, 2025).

The figure above shows the chronological timeline of the major events that happened, which resulted in the ByBit Hack.

Initial Compromisation

On the 4th of February 2025, a malicious activity was detected on one of the workstations of a Safe{Wallet} developer machine, referred to as “Developer1”. He was tricked into downloading and executing a malicious Python application disguised as a Docker Project (Sygnia, 2025). The attacker utilized PyYAML, a Python library that parses YAML files, to execute remote code execution. By crafting a YAML file containing malicious payloads, the attacker achieved remote code execution on Developer1’s machine. Through this, it also allowed the application to bypass antivirus detection (Mandvi, 2025; Manchuri et al., 2024).

The next day, the attackers were able to hijack active AWS session tokens from Developer1’s machine as the access had been granted. This allowed them to access the AWS infrastructure without triggering any multi-factor authentication.

Smart Contract Manipulation

On the 18th of February 2025, the attackers pre-deployed two malicious smart contract on Ethereum. One is the spoofing contract, while the other is a malicious implementation contract. The attacker then submitted a transaction that utilized operator = 1 to delegate execution to the pre-deployed smart contract. This delegate call allowed the original contract to execute logic from an external smart contract. This malicious smart contract introduced sweepETH and sweepERC20 functions. Both of these functions were executed using the delegatecall operation, which allowed the contract to run within the context of Bybit’s wallet. Hence, this led to it bypassing the multisig approval mechanism. Through that, the attackers were able to transfer over 400,000 ETH from Bybit’s cold wallet. (Fang & Werlau, 2025; Janik, 2025)

Injection of Malicious Code

On the 19th of February 2025, the attackers injected a malicious JavaScript code into Safe{Wallet}’s AWS S3 bucket. This could be proven using a snapshot of app.safe.global that was captured by the Wayback Machine (Bybit Interim Investigation Report, 2025). This code altered ByBit’s multisig transactions, redirecting funds to the attacker’s address. Other than that, it will also be discovered that the code was designed specifically to target the Ethereum MultiSig Cold Wallet of Bybit (SlowMist, 2025; Ravichandran et al., 2024). This is because the activation condition is designed to execute only when the source matches one of two contract addresses, which are Bybit’s contract address and the attacker’s. This selective activation ensured that the malicious code remained undetected by regular users and only affected targeted high-value transactions.

Execution of the Heist

This malicious code was only triggered on the 21st of February 2025, when ByBit was executing a multisig transaction. Just two minutes after the fraudulent transaction was executed, the attackers removed the malicious JavaScript code from Safe{Wallet}'s AWS S3 bucket, replacing it with the original, clean version. This swift action was an attempt to cover their tracks and minimise the window for detection and response.

2.1.2. Lazarus Group

On the 26th of February 2025, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) released a Public Service Announcement confirming that the culprit behind this attack was the Lazarus Group (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2025). They are a group of cyber threat actors funded by the North Korean government. Their operations often involve custom-developed malware and advanced social engineering tactics to infiltrate targeted systems (Perdana et al., 2024; Riza et al., 2025).

2.1.3. Impact

After news of the 1.4 billion USD theft became public, many users rushed to withdraw their funds from the platform. Hence, Bybit saw over 5.5 billion USD in withdrawal requests in a short period. Despite the pressure, the company was able to process more than 350,000 withdrawal transactions within just 10 hours. This quick response helped calm some user concerns, and 99.9 per cent of those withdrawal requests were completed successfully (Rodrigues, 2025; Shah et al., 2022).

At the same time, Bybit's total assets dropped sharply. According to DefiLlama, Bybit’s asset holdings fell from around $16.9 billion to $10.8 billion in the days following the incident. The platform also lost a large portion of its market share. Before the attack, Bybit controlled about 11 to 12 per cent of the global spot trading volume among cryptocurrency exchanges. However, after the incident, that number dropped to as low as 4 per cent (McMillan & Ge, 2025; Peak, 2025). The hack also affected the broader cryptocurrency market. The price of Ethereum dropped by around 4 percent, and Bitcoin fell more than 5 percent (Waheed et al., 2024). The depth of trading in the ETH-USDT pair on Bybit dropped by 59 percent, which shows that many traders were leaving the platform or becoming inactive during the crisis (The ByBit Hack: What Happened and What It Means for the Crypto Market?, 2025)

To recover from the hack, Bybit took several emergency steps. The company secured loans from partners like Bitget and bought nearly $300 million worth of Ethereum over-the-counter to refill its cold wallet. Bybit also launched a $140 million bounty program to try and recover the stolen funds. These actions helped stabilize the platform, and within a few days, Bybit was able to restore about 77 percent of its assets under management (McMillan & Ge, 2025)

2.1.4. Lessons Learned

Although this attack was due to a series of events, it all boils down to the start of everything, social engineering. The attackers exploited human trust to bypass technical safeguards, which led to the initial compromise of the victim's device (CertiK - Bybit Incident Technical Analysis, 2025). Numerous social engineering campaigns attempt to convince the user to download and execute some kind of project or application. While technical defenses are essential, this incident highlights that human factors could lead to major setbacks. Companies should always ensure employees are trained and up-to-date on the latest social engineering tactics, especially when engaging with outside entities and open source communities.

2.2. Poly Network Attack

The Poly Network attack is the second-largest asset theft, with stolen digital assets reaching 611 million dollars (Browne, 2021). This event happened in August 2021 when decentralized finance (DeFi) was rapidly growing (TRM Tracks the Poly Network Hack as Attacker Communicates in Real Time, 2021). This new environment changed the traditional financial system but came with significant security challenges. The Poly Network is a set of decentralized protocols that cross multiple blockchains. It enables users to transfer or swap digital assets across different blockchains, solving the problem of blockchain isolation, which is where blockchains cannot easily transfer value across platforms (Zhang et al., 2023; Seng et al., 2024). Although Poly Network had integrated with multiple blockchains, the attacker only targeted three specific blockchains, namely Ethereum, Binance Smart Chain, and Polygon (Poly Network, 2023).

There was a security vulnerability in the administration verification system of the Poly Network protocol. The attacker found a way to use one contract as a tool to manipulate another contract (Gagliardoni, 2021; Sindiramutty, Jhanjhi, Tan, Lau, et al., 2024). There were two main targeted contracts inside the protocol, which were EthCrossChainManager and EthCrossChainData. The main function of EthCrossChainManager was as a transaction processor, which had three functions: processing transactions, validating incoming requests, and executing transfers. On the other hand, EthCrossChainData acted as the address book and rule storage; its main function was to store critical configuration data, keeper addresses (public key addresses), and maintain protocol rules (Thummavet, 2021; Weiqi et al., 2024).

2.2.1. Chronology and Vulnerability of the Poly Network Attack

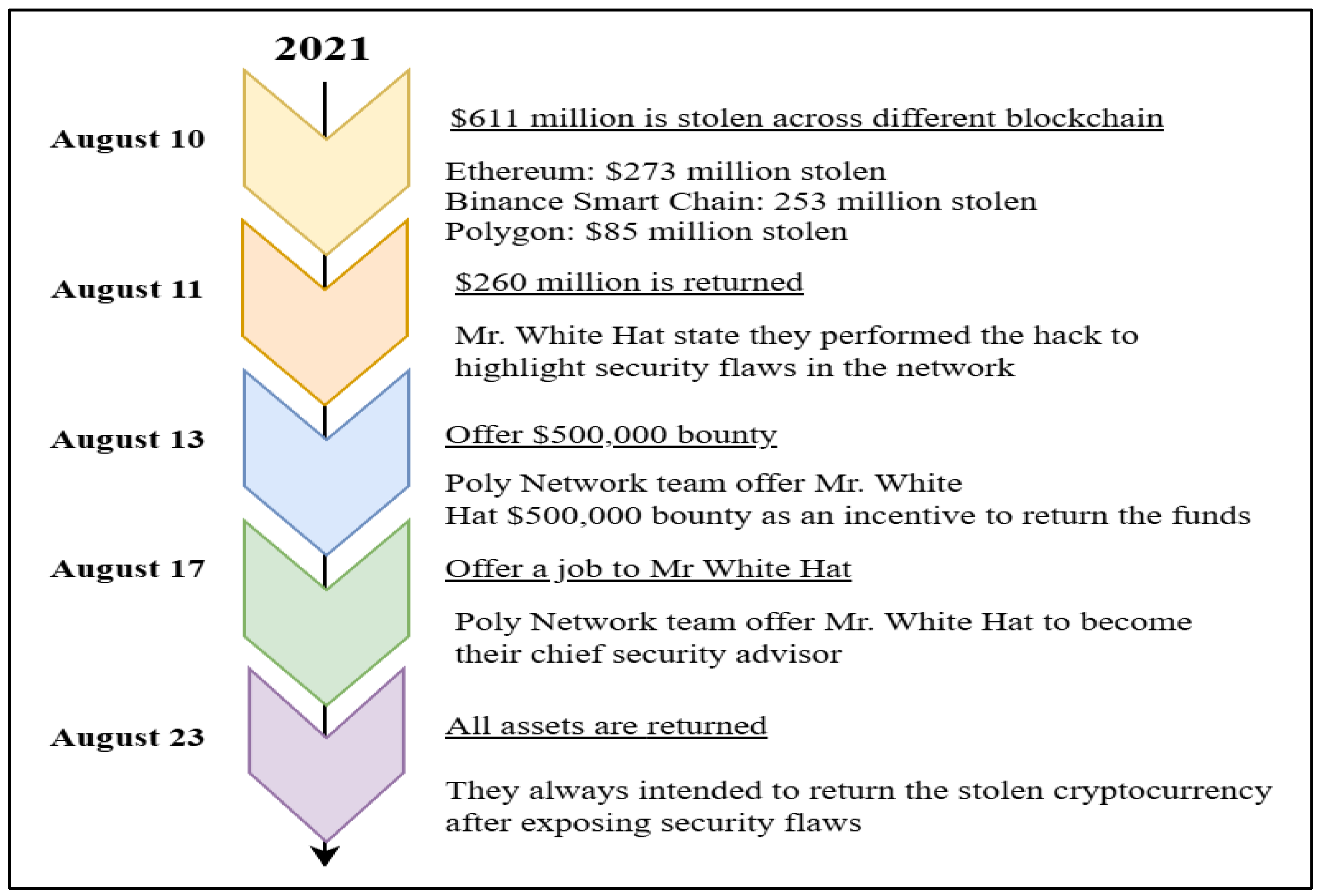

Figure 2.2.1.

Poly Network Attack Timeline.

Figure 2.2.1.

Poly Network Attack Timeline.

In

Figure 2.1.1, the diagram demonstrates the key event and their corresponding date in the Poly Network attack (England, 2021).

In the beginning, the attacker sent malicious code to EthCrossChainManager, which then checked with EthCrossChainData to ensure the command was issued by the administrator (krakenfx, 2021). Due to the flaws in verification, the system considered the attacker to be the admin, which led to them having permission to modify one of the EthCrossChainManager functions called “verifyHeaderAndExecuteTx” (Rekt - Poly Network, 2021). Under the general condition, a normal user is only able to use this function to read the keeper address from EthCrossChainData; only the admin has permission to modify the keeper address. The attacker changed all keeper addresses to three different wallet addresses, where each target blockchain had one wallet address (Benhke, 2021; Sindiramutty et al., 2024). Hence, when a normal user creates a transaction, the digital assets are automatically sent to the attacker's address (Ventures, 2023; Wen et al., 2023). Users were only able to see the destination address; they were not able to see the keeper address, which had already been changed. The transaction looked normal from the user's perspective. Users realised the digital assets were stolen when the assets never appeared at the public address.

Return of Funds and White Hat Recognition

On the 23rd of August 2021, the attacker returned all stolen funds to the users, explaining that the hack was to show the serious security vulnerability, thus earning the name “Mr. White Hat” from the community. The Poly Network team offered 500,000 dollars to Mr. White Hat as an incentive to return the funds and invited him to become their chief security advisor, but Mr. White Hat declined the job offer (Poly Network, 2021)

Impact on Poly Network and DeFi Market

This attack resulted in the theft of more than 20 different types of cryptocurrencies, with stolen assets distributed across three major blockchain networks: $273 million from Ethereum, $253 million from Binance Smart Chain, and $85 million from the Polygon Network (Chainanalysis, 2021). Bitcoin dropped almost 2 per cent after the attack happened, while Ethereum dropped 5 per cent, reflecting shaken investor confidence and growing fears over systemic vulnerabilities in cross-chain DeFi protocols (Wilson et al., 2021; Sindiramutty et al., 2024). This incident significantly damaged Poly Network’s reputation, and the cross-chain interoperability sector was also viewed as high risk at the time. In response, the Poly Network protocol temporarily shut down to implement security fixes, and other cross-chain protocols also paused operations to address similar vulnerabilities(Jhanjhi, 2024) and (Jhanjhi 2025)

Lessons from the Poly Network Exploit

Mr. White Hat highlighted a crucial vulnerability in cross-chain protocols by exploiting vulnerabilities in smart contracts that allowed them to override validation processes and manipulate keeper roles (BlockSec, 2021; Xun et al., 2025). This incident underscores the importance of implementing formal and comprehensive validation mechanisms to prevent access control from becoming a vulnerability. Moreover, the protocol must adopt proper role-based control by clearly separating read and write permissions within smart contracts. This attack reminds the company that it needs to establish a robust auditing system and integrate circuit breakers for unusual transaction conditions in the future (CertiK - Poly Network Exploit, 2022).

3. Proposed Secure System

Blockchain Internet security can be covered from both Web 2.0 and Web 3.0 perspectives. Web 2.0 refers to the second generation of the World Wide Web, mainly consisting of user-generated content and social networking. In contrast, Web 3.0 refers to the decentralised web, mainly focusing on user control, privacy, and decentralisation (Saini, 2025). Although blockchain technology is a core component of Web 3.0, its security can be addressed from Web 2.0. Therefore, our proposed secure system aims to enhance blockchain internet security by incorporating security measures from a Web 2.0 perspective.

Our proposed secure system for blockchain internet security is a web extension, Safu Extension, that consists of the following features:

3.1. Security Approach

The following section will explain how our security approach works, which explains in detail how our proposed solution will function.

3.1.1. Phishing Website Detection

According to the Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), more than 90% of cyberattacks start with phishing as a point of entry, and the rate of phishing will only go higher in Web 3.0 (Elatoubi, 2023; Ying et al., 2024). Therefore, a concern is raised, and we aim to solve this issue with a phishing website detection using whitelist functionality and the Levenshtein distance algorithm.

Whitelist Functionality and Levenshtein Distance Algorithm

Whitelist functionality is a list consisting of more than 50 popular and trusted Web 3.0 domains. This allows the extension to recognise trustworthy websites and allows users to access them without hesitation.

The Levenshtein Distance Algorithm is a string comparison algorithm that calculates the difference between two strings with three editing operations:

Insertion

Deletion

Permutation

The Levenshtein Distance represents the number of changes required to convert one word into another for these operations (Po, 2020; Sindiramutty, Prabagaran, Jhanjhi, Ghazanfar, et al., 2024). By leveraging the Levenshtein Distance Algorithm, it enables Safu Extension to calculate the similarity between the domain entered by users and the domain saved in the whitelist.

If the similarity score is 1, it means that both links are identical; if the similarity score is 0, it means that they are completely different. Safu Extension detects domains with similarity scores of more than 0.75 and is not identical to the whitelisted domain; it has a high possibility of being a phishing website. This threshold is supported by research, which shows that most malicious domains differ by only one character, hence resulting in similarity scores above 0.75 (Szurdi & Christin, 2017; Ahmed et al., 2022). Using this cutoff allows Safu Extension to effectively detect deceptive domain variants while minimising false positives. Therefore, user access to the website is blocked.

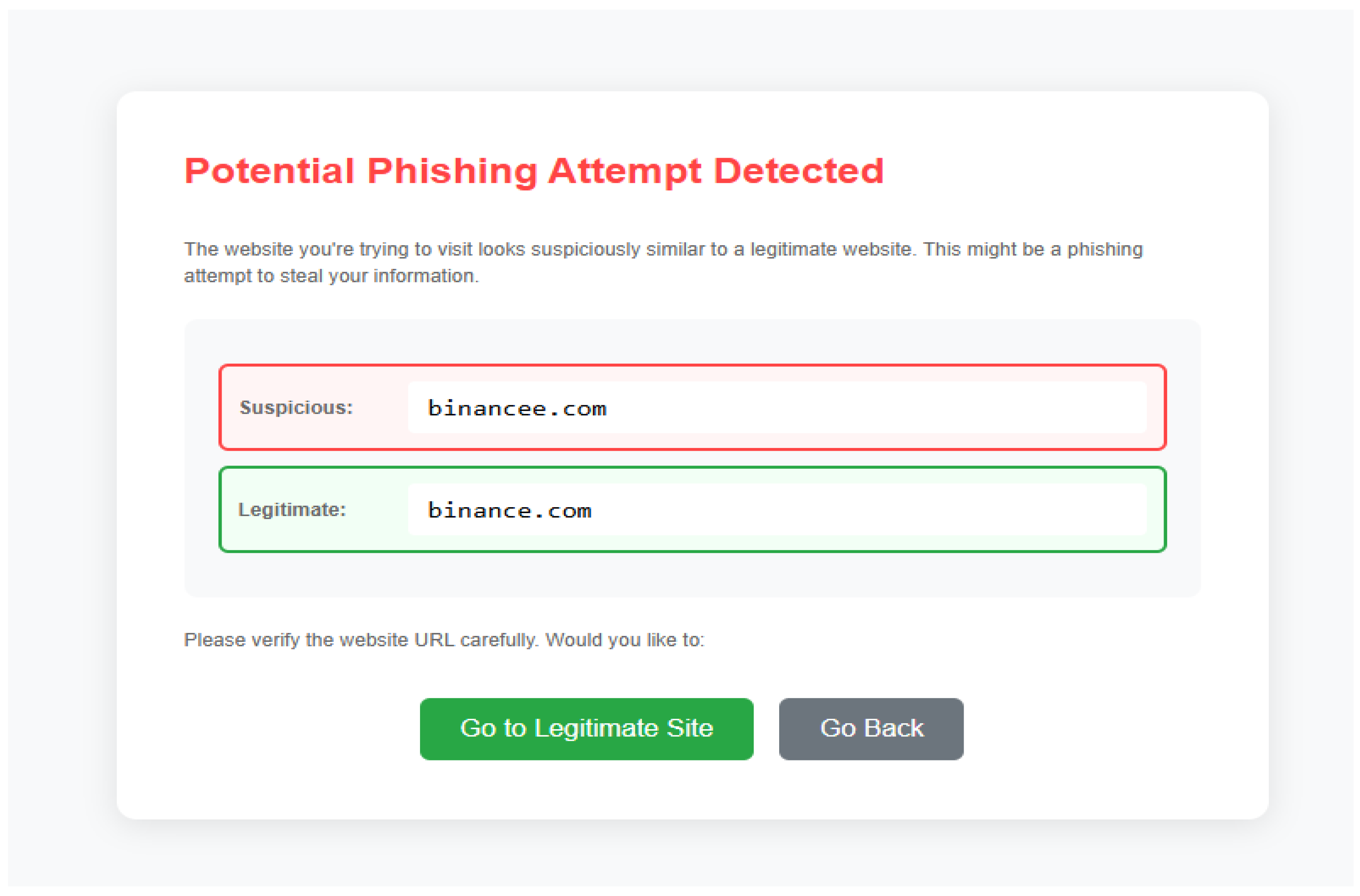

For example, if a user is attempting to access binance.com, but accidentally typed an extra letter, resulting in binancee.com, this type of website may be used by cyber criminals as a phishing website to steal credentials. In this case, Safu Extension will be triggered and prompt users back to the legitimate website.

Figure 3.1.1.1-1.

Page Displayed when Users Tried to Access a Phishing Domain.

Figure 3.1.1.1-1.

Page Displayed when Users Tried to Access a Phishing Domain.

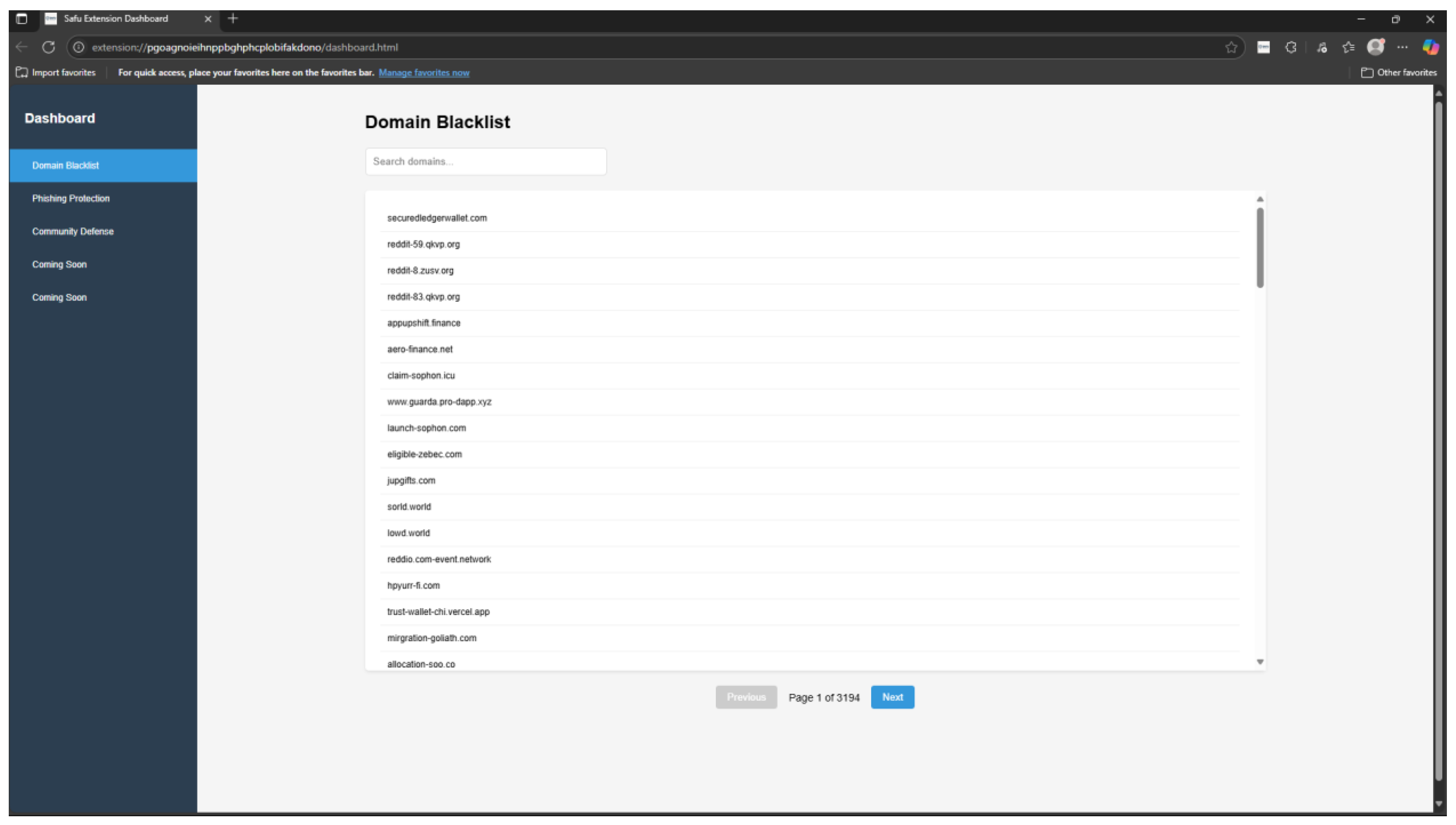

3.1.2. Domain Blacklisting

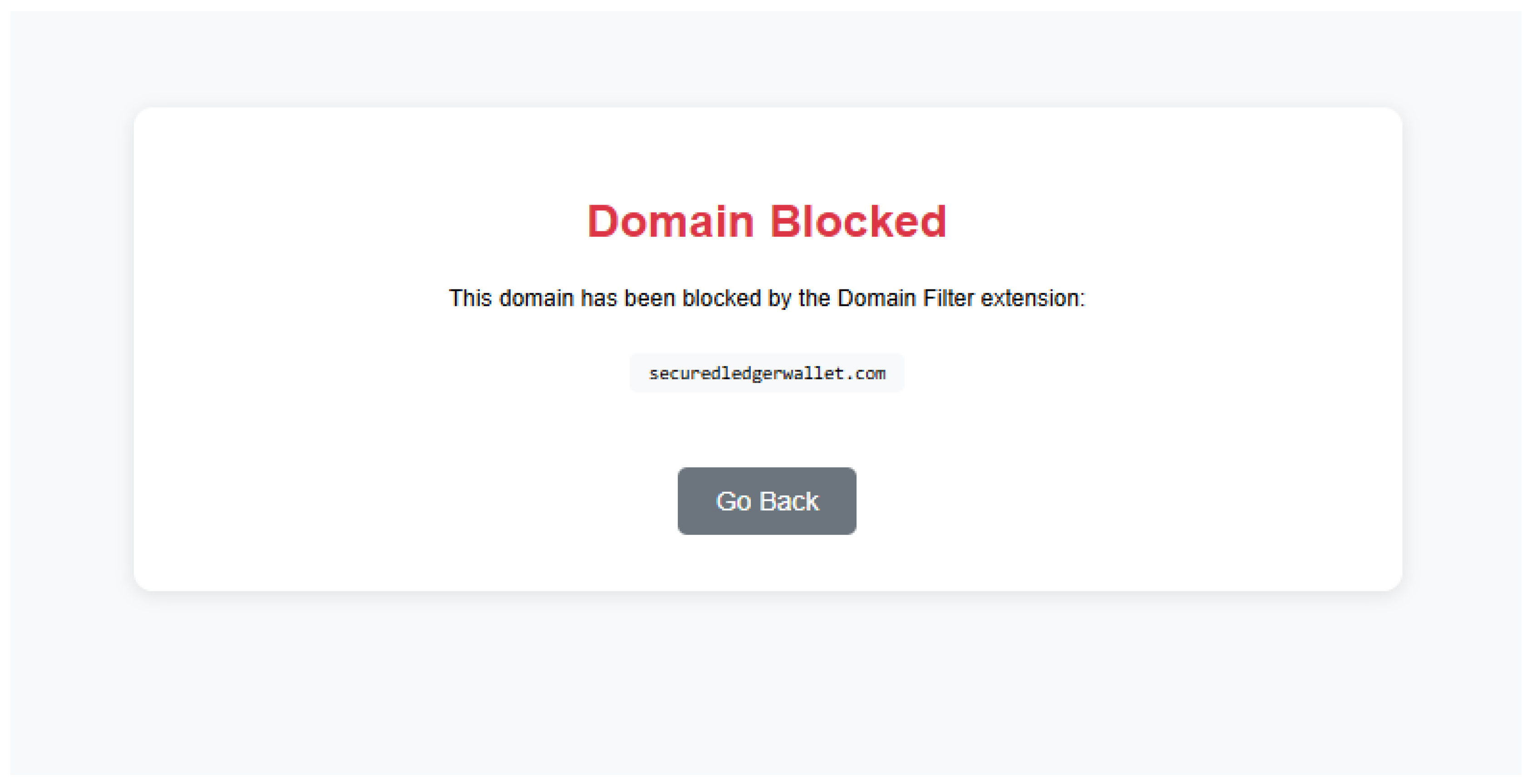

Domain blacklisting is a list consisting of more than three thousand phishing domains. This list is extracted from a GitHub repository that updates regularly (refer to Appendix A for more information). Safu Extension blocks user access to the website, preventing any potential cyber crimes from happening.

Figure 3.1.2-1.

Page Displayed when Users Tried to Access a Blacklisted Domain.

Figure 3.1.2-1.

Page Displayed when Users Tried to Access a Blacklisted Domain.

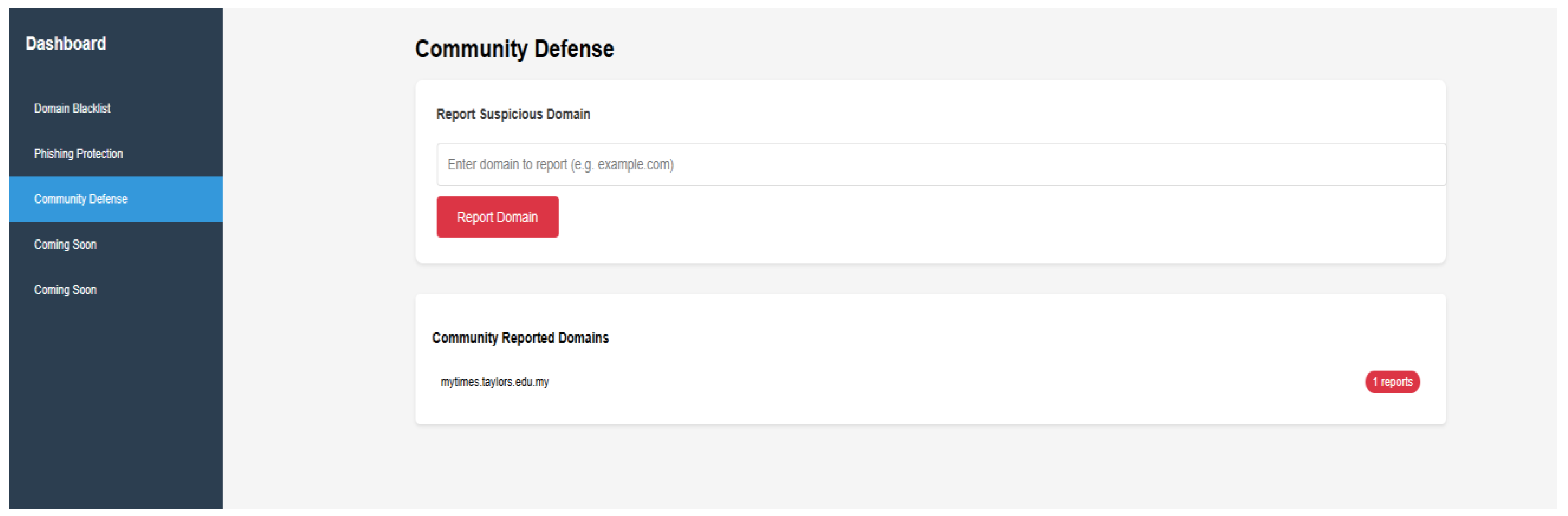

3.1.3. Community-Based Threat Reporting

Community-based threat reporting is a function that allows users to report suspicious websites to the extension.

Figure 3.1.3.1.

Community Defence Page in User Dashboard.

Figure 3.1.3.1.

Community Defence Page in User Dashboard.

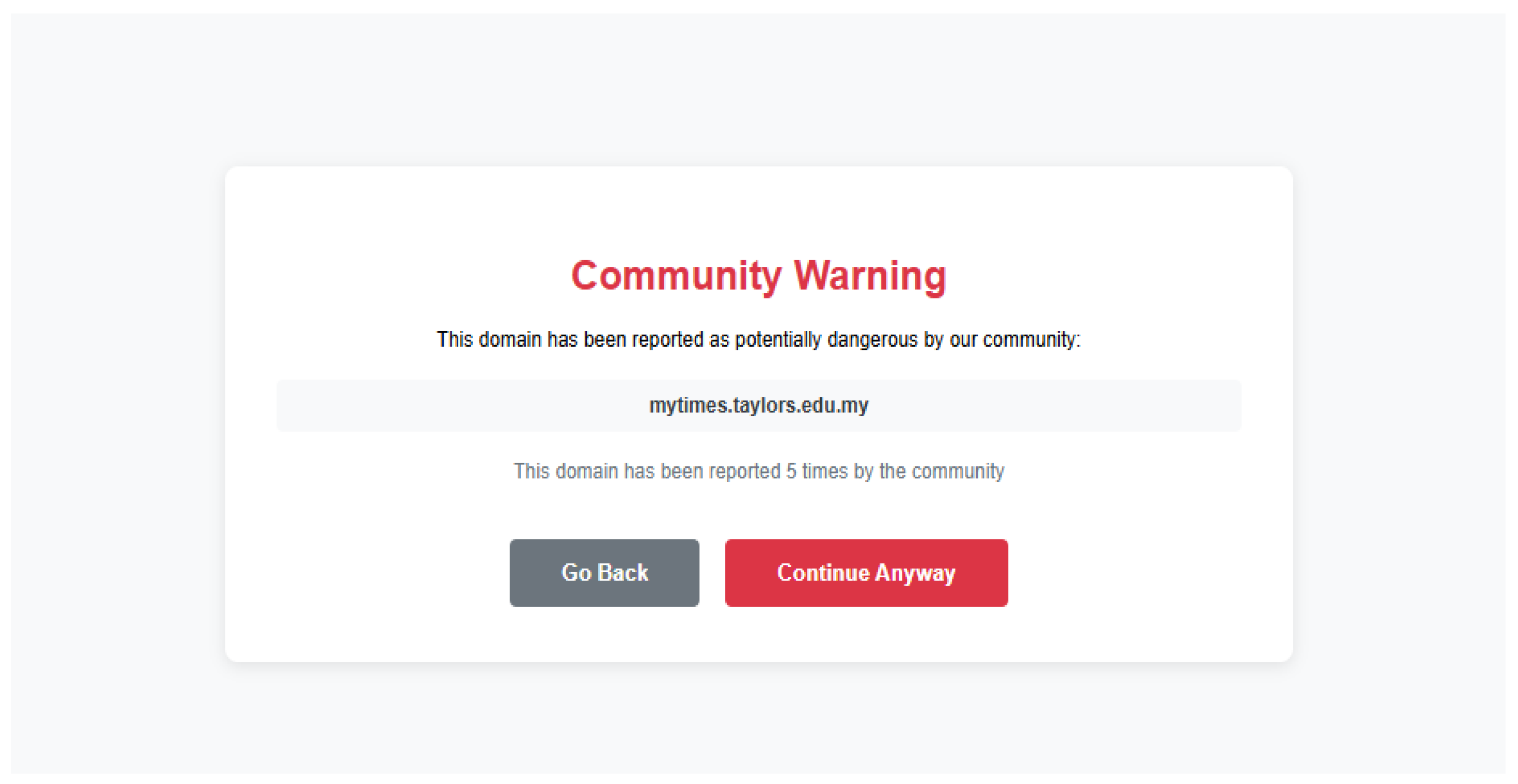

Figure 3.1.3-2.

Page Displayed when Users Tried to Access a Community-Reported Domain.

Figure 3.1.3-2.

Page Displayed when Users Tried to Access a Community-Reported Domain.

In this example, Taylor’s myTimes website has been reported by the community, resulting in Safu Extension being triggered. However, users are given the choice to access the reported website in case the website is falsely reported.

3.1.4. Malicious Code Detection in Smart Contract Using LLM

In order to ensure maximum security, Safu Extension is integrated with an AI API for malicious code detection in smart contracts. Malicious code, including reentrancy attacks, backdoors and hidden functions, could be hidden in a smart contract to exploit and manipulate users or even the blockchain itself. On the other hand, smart contracts are digital contracts that are stored on blockchain and executed when an agreement is met between all users (What Are Smart Contracts on Blockchain?, 2021).

The API leverages a Large Language Model (LLM) that was trained on various smart contract code and cyber attack patterns to identify any potential security threats. It automatically scans smart contract code before a transaction is executed. If any malicious code is detected, users will be blocked from undergoing a transaction. This real-time detection ensures that users are protected while interacting with smart contracts, regardless of their technical background.

3.1.5. Transaction Simulation

Transaction simulation refers to the ability to preview how a transaction will happen, before the users officially authorise the transactions, specifically on-chain transactions (What Are Web3 Transaction Simulations?, 2025)

After ensuring that the smart contract is safe, Safu Extension will simulate the transaction in simple terms for users to understand what exactly is going on in this transaction.

For example, while undergoing a transaction to buy an NFT, Safu Extension will display “You are paying 0.01 ETH to [address] for an NFT, and this action is irreversible. Are you sure?”

This layer acts as a double confirmation for users and prevents any confusion or misoperation.

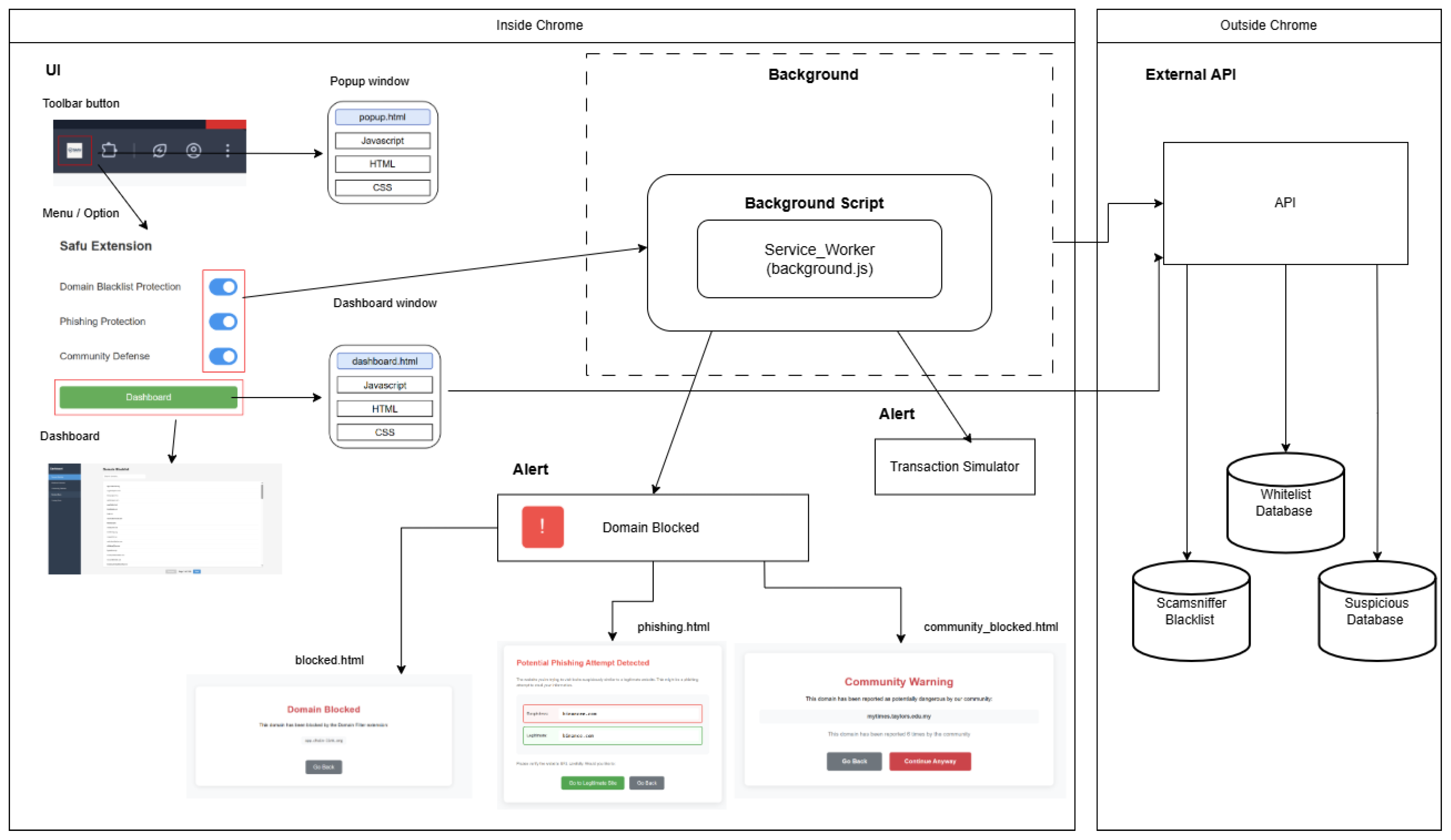

3.2. Architecture

Figure 3.2.1 above shows the architecture diagram of Safu Extension. Safu Extension is mainly built on HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. It is designed to improve users’ security while browsing the Web 3.0 websites. The core of the extension is essentially a background script, specifically background.js. It runs automatically in the background to detect and block malicious websites based on the external API connected. The API contains a whitelist and blacklist of trusted and malicious Web 3.0 websites, which allows users will be able to view the list in the Dashboard. Besides, the background script also generates a transaction preview before a transaction is executed, allowing users to fully understand the situation and prevent user confusion. With the real-time website detection being enabled, users' safety is maximised.

Figure 3.2.1.

Architecture Diagram.

Figure 3.2.1.

Architecture Diagram.

3.2.1. Manifest V3

Safu Extension is built using Manifest V3 compliant. Manifest V3 refers to the latest version of the Chrome extension API, which has the most modern privacy, security, and performance protocols. Other than that, it is widely accepted in the user base as it supports chromium-based browsers such as Chrome, Edge, Brave, and Opera.

3.2.2. Background Service Worker

Safu Extension runs in the background with event listener logic and activates only when needed. The background services are responsible for monitoring domain access and blockchain-related activities like wallet transactions and malicious code detection. Besides that, it also intercepts the page if users are trying to access phishing domains.

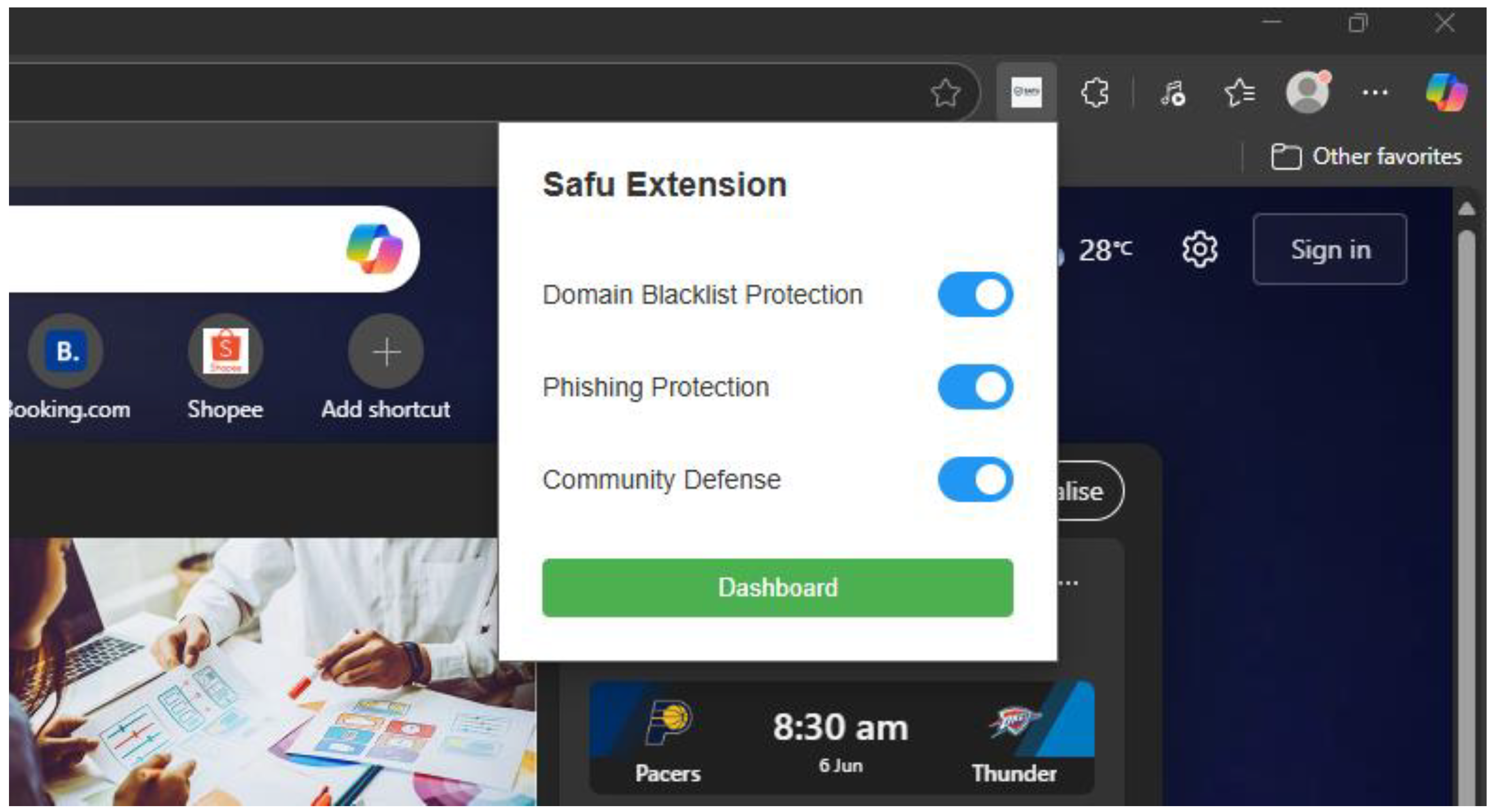

3.2.3. Popup Interface

Safu Extension is displayed as a lightweight popup interface like many other extensions. This provides convenience to the users to modify the extension to their preferences.

Figure 3.2.3.1.

Popup Interface of Safu Extension.

Figure 3.2.3.1.

Popup Interface of Safu Extension.

3.2.4. Dashboard for Details

There is a full-page dashboard where users are able to view the blacklist and whitelist domains, as well as domains reported by the community. This enables a more in-depth understanding of the users towards Safu Extension.

Figure 3.2.4.1.

Domain Blacklisted in User Dashboard.

Figure 3.2.4.1.

Domain Blacklisted in User Dashboard.

3.2.5. Multiple Protection Layers

Safu Extension is built with multiple protection layers to ensure users’ online safety, specifically on the blockchain Internet. It consists of the following layers:

Blacklist Integration

Phishing Detection

Malicious Code Detection

Community Reports

With these 4 protection layers, users are safe from any blockchain internet threats if used correctly.

3.3. Prototype

A working prototype has been developed and successfully tested for functionality. The link to the prototype can be found in Appendix B.

4. Implementation Challenges & Feasibility

While the proposed Safu Extension represents a solution toward Blockchain Internet Security, it does have a few challenges, including both practical challenges and potential limitations.

4.1. Practical Challenges

The main practical challenges are AI implementation, maintenance of the whitelist, the safety of databases, and zero-day vulnerability.

4.1.1. AI Implementation

Integrating an AI API into Safu Extension, specifically a custom Large Language Model (LLM), is technically feasible but very challenging. The LLM has to be trained and fine-tuned on various datasets of smart contracts, which is a huge challenge to overcome to ensure the accuracy and behaviour of the AI.

Additionally, with the continuous evolution of the Web 3.0 ecosystem, the LLM requires continuous model retraining and prompt engineering to keep up-to-date with the latest smart contract formats or cyber attack patterns. This will result in a huge increase in maintenance costs. Moreover, using an AI model as a backend API can negatively impact the system’s performance. Making requests to the AI API may introduce significant delays, particularly when browsing Web 3.0 domains.

4.1.2. Maintenance of Whitelisted Domains

Maintaining an up-to-date database of legitimate domains requires continuous human monitoring and updates. Hundreds of blockchain-related domains are being launched every month in the Web 3.0 ecosystem (DappRadar 2022). Hence, the Safu Extension must keep up with the new platforms and domains released.

This process requires continuous monitoring of the market. Although an automated system can help, human moderation is still required for final validation. A certain profession is required to manage this system properly, which adds to the practical challenges of Safu Extension due to high operational costs.

4.1.3. Database Safety

The whitelist and blacklist functionality of the Safu Extension relies on a third-party API. This introduces security dependency as it is fully dependent on a third party. As the database is externally maintained, it is vulnerable to potential security threats from attackers.

If an attacker gains access to the API through vulnerabilities, insider threats, or breaches, the content could be altered, resulting in a manipulated list of domains. It may fail to block harmful domains and intentionally block legitimate domains, affecting the extension’s reputation and undermining user trust.

Mitigating this risk requires regular audits on the API, ensuring that the list is not altered by any unauthorised personnel.

4.1.4. Zero-Day Vulnerability

A zero-day vulnerability is a newly identified vulnerability unknown to the developer and has no security patch or fix for the vulnerability at that moment (Roumani, 2021; Attaullah et al., 2022). It is referred to as a zero-day because the developers have zero days to address and patch the security vulnerability once it is discovered (Zengeni & Zolkipli, 2024; Sindiramutty et al., 2024). This vulnerability poses a challenge to Safu Extension as the vulnerability can be exploited by attackers before any patches or fixes are deployed by the developers.

Since zero-day vulnerability is technically unpredictable, defending or mitigating this vulnerability requires a strong incident response plan that aims to act as a backup plan before, during, and after a suspected security incident (Incident Response Plan (IRP) Basics | CISA, 2024). However, emergency patching will be very costly and may introduce bugs that can be resource-intensive to fix.

4.2. Potential Limitations

The following section outlines the potential limitations that may affect the Safu Extension.

4.2.1. Reliability of Community-Based Reporting

A potential limitation of Safu Extension is its community-based reporting. Since the community is empowered to report any suspicious domain, false reports, including accidental reports or malicious reports, may block users from accessing legitimate websites. This not only damages the system’s credibility but also damages the reputation of falsely reported websites. In the meantime, implementing moderation to mitigate this requires continuous human monitoring and a validation system, which contributes to the overall cost of the system, making it somewhat impractical to maintain.

4.2.2. Ethical Considerations

The Safu Extension tracks website URLs and transaction details in order to ensure users' safety in a Web 3.0 environment. To build trust, the extension should adopt privacy-by-design principles, collecting only what is essential for security, minimising data retention, and ensuring transparency. While this is one of its core features, it may still raise concerns about users' privacy, as some users might consider the monitoring and tracking as an intrusive and unnecessary data collection feature. Users may be concerned about how the data is collected and stored, and whether their data is being misused. Therefore, this requires a transparent policy that explicitly states that the data collected will be used only for security purposes without commercial use to gain user trust.

4.2.3. Compatibility Across Web 3.0 Platforms

With the rapidly evolving Web 3.0 ecosystem, different websites use different technologies, smart contract standards, and blockchain networks. Ensuring the compatibility of Safu Extension, detecting threats in smart contracts of websites, across every Web 3.0 domain, can be technically challenging. Maintaining compatibility with major Web 3.0 ecosystems such as Ethereum, BNB Chain, Solana, and others requires continuous development and adaptation. If the extension fails to support specific platforms, it may result in incomplete protection and allow some potential threats. This limitation may prevent widespread adoption.

5. Evaluation & Discussion

This chapter reviews the proposed solution, "Safu Extension." It compares the system against real-world use cases and existing solutions. The solution’s strength and weaknesses is critically evaluated in this section.

5.1. Overview of Existing Solutions

In this sub-chapter, existing solutions in the market are introduced and analysed. These solutions will then also be used for comparison with our proposed solution.

5.1.1. Web3 Antivirus

This extension is focused on comprehensive threat protection. It protects against over 60 types of scams and has earned high user trust, making it a solid option for Web3 protection. However, this extension lacks specialised smart contract analysis compared to other options.

5.1.2. WalletGuard

Focuses more on proactive and user-centric risk management. Its key function is detecting new threats that are not listed in their blocklist and reminding users to cancel any high-risk token approvals. Its main weakness is its lack of comprehensive and automated analysis for smart contracts.

5.1.3. AegisWeb3

AegisWeb3 focuses on real-time detection of phishing websites and catching hidden functions and malicious logic in smart contracts. It uses deep analysis to detect and identify malicious websites. However, research shows that it has a 9.8% miss rate for Ethereum-based phishing threats, and it lacks the feature for users to report any threats (Sun et al., 2024).

5.2. Comparative Analysis

To contextualise the "Safu Extension" within the current Web3 security landscape, this section provides a direct comparison against existing solutions. The analysis will evaluate key differences in features, performance, and threat coverage to identify the unique strengths and potential gaps in our proposed solution.

5.2.1. Feature Comparison

Table 1, shown below, shows a comparison of the features that the proposed solution with the other solutions that are currently in the market.

5.2.2. Benchmarking with Existing Solutions

In

Table 2 below, benchmarks our solution with industrial and recognized solutions in the market, through metrics such as active users and financial loss prevented.

5.3. Strength and Weaknesses of Proposed Solution

This section provides an in-depth analysis of the core strengths and weaknesses of the proposed solution, "Safu Extension”.

5.3.1. Stengths

The section below highlights the key strengths of our proposed system, Safu Extension. This includes a layered security mechanism and the compatibility of our extension.

Multi-Layered Phishing Defense

The security features are designed to work together synergistically. This layered security architecture also known as defense in depth, with the main concept behind this is to defend the system using several independent methods (Abdelghani, 2019; Sindiramutty, Tan, & Wei, 2024). As they ensure that if one defense fails, others are in place to thwart an attack. For instance, a zero-day phishing site not yet on the central blacklist might be caught by the Levenshtein algorithm if its URL is deceptively similar to a legitimate one, or it could be quickly flagged by an alert user through the community reporting feature (Azeem et al., 2021). This turns an individual’s data into collective protection for the entire community, creating a network effect that strengthens the system over time.

Usability and Compatability

Furthermore, by being built on Manifest V3, the extension ensures compatibility across a wide range of popular Chromium-based browsers such as Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge. This broad compatibility removes technical barriers to adoption, hence allowing a larger and more diverse user base to protect themselves.

5.3.2. Weaknesses

Despite its strengths, the extension faces significant challenges related to the practical implementation of its advanced features, potential performance drawbacks, and the risks of over-reliance on community-sourced data.

Feasibility and Maintenance of LLM

Training a specialized LLM on vast datasets of smart contract code is a computationally intensive and expensive process. Moreover, the rapid evolution of Web3 technologies means the model would be required ot be constantly updated to the latest technologies and concepts. If new smart contract patterns and attack vectors emerge that the model was not trained on, the models accuracy will be diminished over time. This also makes it susceptible to zero day vulnerabilities. Constant retraining and fine-tuning would be necessary to maintain its effectiveness. This leads to substantial and recurring operational costs.

6. Conclusions

This report has explored the critical security challenges that blockchain environments are facing, focusing on social engineering attacks and smart contract vulnerabilities. The real-world examples of these two attacks explored in the report are the Bybit Hack and the Poly Network Attack. The Bybit Hack of 2025 led to $1.40 billion in losses, demonstrating how attackers can exploit human trust through social engineering to bypass robust security measures. Similarly, the Poly Network attack resulted in $611 million in losses due to the vulnerabilities in smart contract validation mechanisms, showing that technical flaws become exploitable when adequate security measures are lacking. The proposed Safu Extension represents a solution that addresses these identified vulnerabilities with a multi-layered security framework. The main feature including phishing detection using Levenshtein Distance Algorithm, domain blacklisting, AI-driven code analysis, community threat reporting, and transaction simulation to create a comprehensive security framework. This layered approach protects users from common attacks while remaining user-friendly through an intuitive browser extension.

However, there are several challenges that the Safu extension must face. The integration of AI requires significant computational resources and continuous updates to address evolving attack patterns. Additionally, maintaining whitelists and managing community-based reporting present ongoing operational challenges that require careful consideration and resource allocation. The risk of false community reports is one limitation of the Safu Extension, where the community could block legitimate websites and harm the system’s credibility. Addressing this problem will require constant monitoring and validation, increasing system costs and reducing practicality.The findings of this study contribute to a broader understanding of blockchain security challenges and provide a foundation for developing more effective protection mechanisms that address both technical vulnerabilities and human factors in the Web 3.0 ecosystem.

References

-

2025 Data Breach Investigations Report. (2025). Verizon Business. https://www.verizon.com/business/resources/reports/dbir/.

- Abdelghani, T. (2019). Implementation of Defense in Depth Strategy to Secure Industrial Control System in Critical Infrastructures. American Journal of Artificial Intelligence, 3(2), 17. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Q. W., Garg, S., Rai, A., Ramachandran, M., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Masud, M., & Baz, M. (2022). AI-Based Resource Allocation Techniques in Wireless Sensor Internet of Things Networks in Energy Efficiency with Data Optimization. Electronics, 11(13), 2071. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. (2025). Enhancing Data Security and Transparency: The Role of Blockchain in Decentralized Systems. International Journal of Advanced Engineering, Management and Science, 11(1), 167–176. [CrossRef]

- An, M., Fan, Q., Yu, H., An, B., Wu, N., Zhao, H., Wan, X., Li, J., Wang, R., Zhen, J., Zou, Q., & Zhao, B. (2023). Blockchain Technology Research and Application: A Literature Review and Future Trends. Journal of Data Science and Intelligent Systems. [CrossRef]

- Attaullah, M., Ali, M., Almufareh, M. F., Ahmad, M., Hussain, L., Jhanjhi, N., & Humayun, M. (2022). Initial stage COVID-19 detection system based on patients’ symptoms and chest X-Ray images. Applied Artificial Intelligence, 36(1). [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M., Ullah, A., Ashraf, H., Jhanjhi, N., Humayun, M., Aljahdali, S., & Tabbakh, T. A. (2021). FOG-Oriented secure and lightweight data aggregation in IOMT. IEEE Access, 9, 111072–111082. [CrossRef]

- B. Lashkari & P. Musilek. (2021). A Comprehensive Review of Blockchain Consensus Mechanisms. IEEE Access, 9, 43620–43652. [CrossRef]

- Basit, A., Zafar, M., Liu, X., Javed, A. R., Jalil, Z., & Kifayat, K. (2021). A comprehensive survey of AI-enabled phishing attacks detection techniques. Telecommunication Systems, 76(1), 139–154. [CrossRef]

- Bell, S., & Komisarczuk, P. (2020). An Analysis of Phishing Blacklists: Google Safe Browsing, OpenPhish, and PhishTank. Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Science Week Multiconference, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Benhke, R. (2021, November 8). Explained: The Poly Network Hack (August 2021). Halborn. https://www.halborn.com/blog/post/explained-the-poly-network-hack-august-2021.

- BlockSec. (2021, August 12). The Further Analysis of the Poly Network Attack—BlockSec Blog. BlockSec. https://blocksec.com/blog/the-further-analysis-of-the-poly-network-attack.

- Brohi, S. N., Jhanjhi, N., Brohi, N. N., & Brohi, M. N. (2020). Key Applications of State-of-the-Art Technologies to Mitigate and Eliminate COVID-19.pdf. Authorea Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Browne, R. (2021, August 17). Crypto platform hit by $600 million heist asks hacker to become its chief security advisor. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/08/17/poly-network-cryptocurrency-hack-latest.html.

-

Bybit Interim Investigation Report (p. 8). (2025). Sygnia.

- Carpentier-Desjardins, C., Paquet-Clouston, M., Kitzler, S., & Haslhofer, B. (2025). Mapping the DeFi crime landscape: An evidence-based picture. Journal of Cybersecurity, 11(1), tyae029. [CrossRef]

-

CertiK - Bybit Incident Technical Analysis. (2025, February 21). Certik. https://certik.com/resources/blog/bybit-incident-technical-analysis.

-

CertiK - Poly Network Exploit. (2022, March 12). Certik. https://certik.com/resources/blog/poly-network-exploit.

- Chainanalysis. (2021, August 12). Poly Network Attacker Returning Funds After Pulling Off Biggest DeFi Theft Ever—Chainalysis. Chainanalysis. https://www.chainalysis.com/blog/poly-network-hack-august-2021/.

- Chen, Z., Hu, Y., He, B., Luo, D., Wu, L., & Zhou, Y. (2025). Dissecting Payload-based Transaction Phishing on Ethereum. Proceedings 2025 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium. Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA. [CrossRef]

-

DappRadar 2022: A Year in Review. (2022, December 22). DappRadar. https://dappradar.com/blog/dappradar-2022-a-year-in-review.

- Das, S. R., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Asirvatham, D., Ashfaq, F., & Abdulhussain, Z. N. (2023, February). Proposing a model to enhance the IoMT-based EHR storage system security. In International Conference on Mathematical Modeling and Computational Science (pp. 503-512). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Elatoubi, M. (2023). Phishing in Web 3.0: Opportunities for the Attackers, Challenges for the Defenders. ARIS2 - Advanced Research on Information Systems Security, 3(2), 11–25. [CrossRef]

- England, J. (2021, December 6). Timeline: Poly Network and the curious case of ‘Mr Whitehat.’ FinTech Magazine. https://fintechmagazine.com/crypto/timeline-poly-network-and-curious-case-mr-whitehat.

- Fang, V., & Werlau, P. (2025, February 28). ByBit Billion Dollar Hack - Part 1: Smart Contracts Forensics Timeline. AnChain.AI. https://www.anchain.ai/blog/bybit.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2025, February 26). TraderTraitor: North Korean state-sponsored cyber actors exploit cryptocurrency platforms. Internet Crime Complaint Centre. https://www.ic3.gov/PSA/2025/PSA250226.

- Feng, P., Bi, Z., Yan, L. K. Q., Wen, Y., Peng, B., Liu, J., Yin, C. H., Wang, T., Chen, K., Zhang, S., Li, M., Xu, J., Liu, M., Pan, X., Wang, J., & Niu, Q. (2024). Mastering AI: Big Data, Deep Learning, and the Evolution of Large Language Models -- Blockchain and Applications (No. arXiv:2410.10110). arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Gagliardoni, T. (2021, August 12). The Poly Network Hack Explained. Kudelski Security Research. https://research.kudelskisecurity.com/2021/08/12/the-poly-network-hack-explained/.

- Grassi, P. A., Garcia, M. E., & Fenton, J. L. (2017). Digital identity guidelines: Revision 3. National Institute of Standards and Technology. [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M., Ashraf, H., Jalil, Z., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Humayun, M., Saeed, S., & Almuhaideb, A. M. (2022). AI-Based wormhole attack detection techniques in wireless sensor networks. Electronics, 11(15), 2324. [CrossRef]

- Humayun, M., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Niazi, M., Amsaad, F., & Masood, I. (2022). Securing Drug Distribution Systems from Tampering Using Blockchain. Electronics, 11(8), 1195. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K., Rahmatyar, A. R., Riskhan, B., Sheikh, M. a. U., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). Threats and Vulnerabilities of Wireless Networks in the Internet of Things (IoT). 2024 IEEE 1st Karachi Section Humanitarian Technology Conference (KHI-HTC), 2, 1–8. [CrossRef]

-

Incident Response Plan (IRP) Basics | CISA. (2024, January 31). https://www.cisa.gov/resources-tools/resources/incident-response-plan-irp-basics.

- Jabeen, T., Jabeen, I., Ashraf, H., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Yassine, A., & Hossain, M. S. (2023). An intelligent healthcare system using IoT in wireless sensor network. Sensors, 23(11), 5055. [CrossRef]

- Janik, R. (2025, March 7). ByBit Hack: Exploiting Smart Contracts to Drain Funds - A Deep Dive on How it Happened. Lukka. https://lukka.tech/bybit-hack-deep-dive/.

- Jhanjhi, N. (2024). Comparative analysis of frequent pattern mining algorithms on healthcare data. In 2024 IEEE 9th International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Applied Sciences (ICETAS) (pp. 1-10). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Jhanjhi, N. Z. (2025). Investigating the influence of loss functions on the performance and interpretability of machine learning models. In S. Pal & Á. Rocha (Eds.), Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Mathematical Modeling and Computational Science. ICMMCS 2025. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 1399 (pp. 100-110). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Jun, A. Y. M., Jinu, B. A., Seng, L. K., Maharaiq, M. H. F. B. Z., Khongsuwan, W., Junn, B. T. K., Hao, A. a. W., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). Exploring the Impact of Crypto-Ransomware on Critical Industries: Case Studies and Solutions. Preprint.org. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N. A., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Brohi, S. N., Almazroi, A. A., & Almazroi, A. A. (2021). A secure communication protocol for unmanned aerial vehicles. Computers, Materials & Continua/Computers, Materials & Continua (Print), 70(1), 601–618. [CrossRef]

- Kiyani, F. F., Hamid, B., Humayun, M., Sindiramutty, S. R. a. L., & Chowdhury, S. (2024). Discovery of Influential Publications Using Research Article’s Usage Context. 2024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- krakenfx. (2021, September 22). Abusing Smart Contracts to Steal $600 million: How the Poly Network Hack Actually Happened. Kraken Blog. https://blog.kraken.com/product/security/abusing-smart-contracts-to-steal-600-million-how-the-poly-network-hack-actually-happened.

- Krishnan, S., Thangaveloo, R., Rahman, S. B. A., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2021). Smart Ambulance Traffic Control system. Trends in Undergraduate Research, 4(1), c28-34. [CrossRef]

- Linqiang, Y., Sindiramutty, S. R. a. L., Ashraf, H., Muzammal, S. M., Balakrishnan, S. a. P., Gupta, S., & Kavita, N. (2024). Intelligent Household Waste Classification System Based on Machine Learning. 2024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC), 760–768. [CrossRef]

- Manchuri, A., Kakera, A., Saleh, A., & Raja, S. (2024). pplication of Supervised Machine Learning Models in Biodiesel Production Research - A Short Review. Borneo Journal of Sciences and Technology. [CrossRef]

- Mandvi. (2025, May 7). Simulated Attack Reveals DPRK’s Largest Cryptocurrency Heist via Compromised macOS Developer and AWS Exploits. Cyber Security News. https://cyberpress.org/simulated-attack-reveals-dprks-largest-cryptocurrency-heist/.

- McMillan, R., & Ge, V. H. (2025, March 6). How the Biggest Crypto Hack Ever Nearly Destroyed the World’s No. 2 Exchange. WSJ. https://www.wsj.com/finance/currencies/how-the-biggest-crypto-hack-ever-nearly-destroyed-the-worlds-no-2-exchange-ee273a3a.

- Muzafar, S., & Jhanjhi, N. Z. (2019). Success stories of ICT implementation in Saudi Arabia. In Advances in electronic government, digital divide, and regional development book series (pp. 151–163). [CrossRef]

- Muzammal, S. M., Murugesan, R. K., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Jung, L. T. (2020). SMTrust: Proposing Trust-Based Secure Routing Protocol for RPL Attacks for IoT Applications. 2020 International Conference on Computational Intelligence (ICCI), 305–310. [CrossRef]

- Ogundokun, R. O., Arowolo, M. O., Damaševičius, R., & Misra, S. (2023). Phishing Detection in Blockchain Transaction Networks Using Ensemble Learning. Telecom, 4(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Peak, B. (2025, March 5). How the Bybit hack happened: Inside the $1.5 billion crypto heist. Cointelegraph. https://cointelegraph.com/learn/articles/how-the-bybit-hack-happened.

- Perdana, A., Aminanto, M. E., & Anggorojati, B. (2024). Hack, heist, and havoc: The Lazarus Group’s triple threat to global cybersecurity. Journal of Information Technology Teaching Cases, 20438869241303941. [CrossRef]

- Po, D. K. (2020). Similarity Based Information Retrieval Using Levenshtein Distance Algorithm. International Journal of Advances in Scientific Research and Engineering (IJASRE), ISSN:2454-8006, DOI: 10.31695/IJASRE, 6(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Poly Network. (2021, September 3). Honour, Exploit, and Code: How we lost 610M dollar and got it back. Poly Network. https://medium.com/poly-network/honour-exploit-and-code-how-we-lost-610m-dollar-and-got-it-back-c4a7d0606267.

- Poly Network. (2023, November 20). The Poly Network Exploit Analysis | by Poly Network | Medium. Medium. https://polynetwork.medium.com/the-poly-network-exploit-analysis-b0a77aff6078.

- Praitheeshan, P., Pan, L., Yu, J., Liu, J., & Doss, R. (2020). Security Analysis Methods on Ethereum Smart Contract Vulnerabilities: A Survey (No. arXiv:1908.08605). arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, N., Tewaraja, T., Rajasegaran, V., Kumar, S. S., Gunasekar, S. K. L., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). Comprehensive Review Analysis and Countermeasures for Cybersecurity Threats: DDoS, Ransomware, and Trojan Horse Attacks. preprint.org. [CrossRef]

-

Rekt—Poly Network. (2021, August 11). Rekt. https://www.rekt.news/.

- Rivas, M., Santos, R., & Sanz, J. (2025, March 10). In-Depth Technical Analysis of the Bybit Hack. Ncc Group. https://www.nccgroup.com/us/research-blog/in-depth-technical-analysis-of-the-bybit-hack.

- Riza, A. Z. B. M., Jennsen, L., Anggani, P., Rafeen, A. I., Ruth, P. N. J., Sookun, D., Sookun, V., Yusri, N. a. Z. B. M., Sern, L. J., Luximon, L., Omer, M. L., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2025). Leveraging Machine Learning and AI to Combat Modern Cyber Threats. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F. (2025, February 23). Bybit Sees Over $4 Billion ‘Bank Run’ After Crypto’s Biggest Hack. CoinDesk. https://www.coindesk.com/business/2025/02/22/bybit-sees-over-usd4-billion-bank-run-after-crypto-s-biggest-hack.

- Roumani, Y. (2021). Patching zero-day vulnerabilities: An empirical analysis. Journal of Cybersecurity, 7(1), tyab023. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S., Abdullah, A., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Naqvi, M., & Nayyar, A. (2022). New techniques for efficiently k-NN algorithm for brain tumor detection. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 81(13), 18595–18616. [CrossRef]

- Saini, K. (2025, June 9). Web 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, & 4.0: A Detailed Guide. Simplilearn. https://www.simplilearn.com/what-is-web-1-0-web-2-0-and-web-3-0-with-their-difference-article.

- Schor, L. (2023). What is Safe? [Safe{Wallet}]. https://help.safe.global/en/articles/40869-what-is-safe.

- Seng, Y. J., Cen, T. Y., Raslan, M. a. H. B. M., Subramaniam, M. R., Xin, L. Y., Kin, S. J., Long, M. S., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). In-Depth Analysis and Countermeasures for Ransomware Attacks: Case Studies and Recommendations. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Shah, I. A., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Laraib, A. (2022). Cybersecurity and blockchain usage in contemporary business. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 49–64). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Tan, C. E., Tee, W. J., Lau, S. P., Jazri, H., Ray, S. K., & Zaheer, M. A. (2024). IoT and AI-Based Smart Solutions for the Agriculture Industry. In Advances in computational intelligence and robotics book series (pp. 317–351). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Tan, C. E., Yun, K. J., Manchuri, A. R., Ashraf, H., Murugesan, R. K., Tee, W. J., & Hussain, M. (2024). Data security and privacy concerns in drone operations. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 236–290). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R., Jhanjhi, N., Tan, C. E., Lau, S. P., Muniandy, L., Gharib, A. H., Ashraf, H., & Murugesan, R. K. (2024). Industry 4.0. In Advances in logistics, operations, and management science book series (pp. 342–405). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R., Prabagaran, K. R. V., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Ghazanfar, M. A., Malik, N. A., & Soomro, T. R. (2024). Security Considerations in Generative AI for web Applications. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 281–332). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R., Prabagaran, K. R. V., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Murugesan, R. K., Brohi, S. N., & Masud, M. (2024). Generative AI in network security and intrusion detection. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 77–124). [CrossRef]

- Sindiramutty, S. R., Tan, C. E., & Wei, G. W. (2024). Eyes in the sky. In Advances in information security, privacy, and ethics book series (pp. 405–451). [CrossRef]

- SlowMist. (2025, February 27). Bybit’s $1.5 Billion Theft Unveiled: Safe{Wallet} Front-End Code Tampered. Medium. https://slowmist.medium.com/bybits-1-5-billion-theft-unveiled-safe-wallet-front-end-code-tampered-84b78f0fa9c2.

- Soltani, R., Zaman, M., Joshi, R., & Sampalli, S. (2022). Distributed Ledger Technologies and Their Applications: A Review. Applied Sciences, 12(15), Article 15. [CrossRef]

- Sun, D., Ma, W., Nie, L., & Liu, Y. (2024). SoK: Comprehensive Analysis of Rug Pull Causes, Datasets, and Detection Tools in DeFi (No. arXiv:2403.16082). arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Sygnia. (2025, March 16). Sygnia’s Investigation into the Bybit Hack: What We Know So Far. Sygnia. https://www.sygnia.co/blog/sygnia-investigation-bybit-hack/.

- Szurdi, J., & Christin, N. (2017). Email typosquatting. Proceedings of the 2017 Internet Measurement Conference, 419–431. [CrossRef]

-

The ByBit Hack: What Happened and What It Means for the Crypto Market? (2025, February 26). Virtune. https://www.virtune.com/en/insights/bybit-hack-2025.

- Thummavet, P. (2021, September 2). Poly Network—In-Depth Analysis of the Biggest Heist in DeFi History. Serial Coder. https://www.serial-coder.com/post/poly-network-in-depth-analysis-of-the-biggest-heist-in-defi-history/.

- Tidy, J. (2022, March 31). Ronin Network: What a $600m hack says about the state of crypto. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-60933174.

- Tong, W., Li, J., Yang, L., Huang, X., Gao, X., & Dong, Z. (2025). A Survey on Blockchain Scalability. In D. He, J. Wu, C. Wang, & H. Huang (Eds.), Blockchain, Metaverse and Trustworthy Systems (pp. 133–146). Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, G., Ahad, M. A., & Casalino, G. (2023). A comprehensive review of blockchain technology: Underlying principles and historical background with future challenges. Decision Analytics Journal, 9, 100344. [CrossRef]

-

TRM Tracks the Poly Network Hack as Attacker Communicates in Real Time. (2021, August 10). TRM Blog. https://www.trmlabs.com/resources/blog/trm-tracks-the-poly-network-hack-as-attacker-communicates-in-real-time-via-input-data.

- Ventures, R. M. (2023, July 6). An In-Depth Analysis of the Recent Exploit in the Poly Network that led to $10m+ being lost! D3ploy. https://medium.com/d3ploy/an-in-depth-analysis-of-the-recent-exploit-in-the-poly-network-that-led-to-10m-being-lost-7eca2922ee3d.

- Waheed, A., Seegolam, B., Jowaheer, M. F., Sze, C. L. X., Hua, E. T. F., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2024). Zero-Day Exploits in Cybersecurity: Case Studies and Countermeasure. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Zhu, H., & Sun, L. (2021). Social Engineering in Cybersecurity: Effect Mechanisms, Human Vulnerabilities and Attack Methods. IEEE Access, 9, 11895–11910. IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

- Weiqi, X., Hooi, S. T. C., Sindiramutty, S. R. a. L., Asirvatham, D. a. L., Kumar, D., & Verma, S. (2024). Surface Anomaly Detection Using Machine Learning Technique. 2024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Wen, B. O. T., Syahriza, N., Xian, N. C. W., Wei, N. G., Shen, T. Z., Hin, Y. Z., Sindiramutty, S. R., & Nicole, T. Y. F. (2023). Detecting cyber threats with a Graph-Based NIDPS. In Advances in logistics, operations, and management science book series (pp. 36–74). [CrossRef]

-

What Are Smart Contracts on Blockchain? | IBM. (2021, July 27). https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/smart-contracts.

-

What are web3 transaction simulations? (2025, January 23). Alchemy. https://www.alchemy.com/overviews/transaction-simulation.

- Wilhoit, C., & Dejesus. (2025, May 6). Bit ByBit—Emulation of the DPRK’s largest cryptocurrency heist. Elastic Security Labs. https://www.elastic.co/security-labs/bit-bybit?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Wilson, T., Westbrook, T., & John, A. (2021, August 12). Hackers return $260 mln to cryptocurrency platform after massive theft | Reuters. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/technology/defi-platform-poly-network-reports-hacking-loses-estimated-600-million-2021-08-11/.

- Xiao, Y., Zhang, N., Lou, W., & Hou, Y. T. (2020). A Survey of Distributed Consensus Protocols for Blockchain Networks. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 22(2), 1432–1465. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials. [CrossRef]

- Xun, A. T., En, L. a. Z., Shen, L. T., Xin, A. N., Soon, W. H., Jun, W. Z., Ramachandra, H., Xinghao, G., Khant, N. M., Weitao, F., & Sindiramutty, S. R. (2025). Building Trust in Cloud Computing:Strategies for Resilient Security. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Ying, X., Murugesan, R. K., Sindiramutty, S. R., Wei, G. W., Balakrishnan, S., Kumar, D., & Verma, S. (2024). Scene Text Recognition using Deep Learning Techniques. 024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Zengeni, I. P., & Zolkipli, M. fadli. (2024). Zero-Day Exploits and Vulnerability Management. Borneo International Journal eISSN 2636-9826, 7(3), Article 3.

- Zhang, M., Zhang, X., Barbee, J., Zhang, Y., & Lin, Z. (2023). SoK: Security of Cross-chain Bridges: Attack Surfaces, Defenses, and Open Problems (No. arXiv:2312.12573). arXiv. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).